In the beginning, the dream was to explore space and everything that was ‘out there in the great unknown’, but the first astronauts found that the truly remarkable view was looking back at the Earth; and, with the latest satellite camera technology, our view is better than it ever was. From space we can track the drama of powerful weather systems, trace the relentless flow of ocean currents, witness the epic daily rhythms of time and tide, follow the mass migration of people and wildlife across the globe, and even chase specks of dust as they’re swept through the atmosphere. Viewed from space these movements span oceans and continents, paying no heed to boundaries, both natural and manmade. Everything on our planet is linked, in more ways than you might imagine. The Earth is a living, breathing, moving entity in the black void of space, and we are just a tiny part of it.

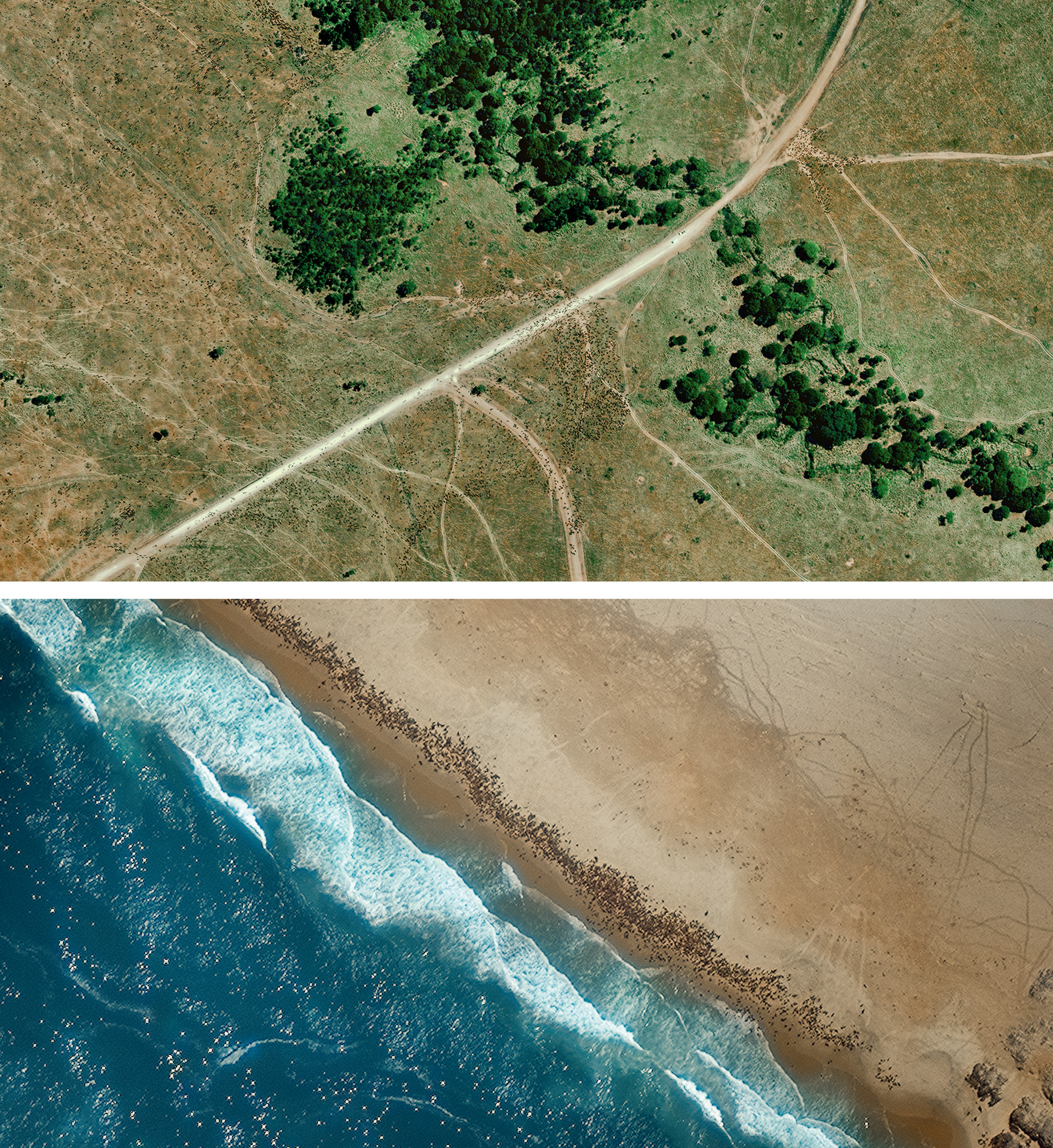

Satellite technology is so advanced that scientists monitoring the Earth and all that lives on it are not only able to pick out the shapes of continents or countries, but can also focus on particular mountains, lakes and cities, and even zoom in on streets and cars driving along them. The resolution of these space cameras is so impressive that they can be used to spot an individual animal from hundreds of kilometres above the Earth, and in Kenya’s Buffalo Springs National Reserve in East Africa, this is precisely what has been happening.

All across Africa, scientists are monitoring the fate of African savannah elephants, a species endangered because of the illegal trade in ivory. About 50 elephants have been killed every day since 2006, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), so it is vital to know where they are, what they are doing, and when they are in danger. In Buffalo Springs and neighbouring Samburu National Reserve, Save the Elephant scientists are keeping track of elephants using GPS collars. These ‘ping’ signals several times a day to satellites orbiting the Earth, enabling researchers to follow herds in almost real time. The Earth from Space team took this a stage further.

Using the ping data to position a satellite camera, the team hoped that they could see an individual elephant from space, whilst filming it on the ground. Series director Barny Revill and his film crew were with the animals at Buffalo Springs.

‘It was exciting and a touch surreal to be with the elephants, knowing that, hundreds of kilometres above us, the satellite was taking a picture. It was also a nervous time as the satellite passed over just once a day; so, if there was a single cloud overhead at the precise moment it was taking its image, there would have been nothing to see.’

Back at base, the production team received images from the GeoEye-1 satellite and, using the latest GPS locations, they were able to zoom in on Buffalo Springs. The herd was right there on the screen … next to a fluffy cloud that, thankfully, was not obscuring the view. They had found an elephant from over 600 kilometres above the Earth!

‘Receiving the image in the field was an incredible moment; knowing that we had filmed an elephant family on the ground, in the air from a drone, and actually from space, all at the same time, was simply mind-blowing.’

The animal of particular interest was Raine, an orphan that had been adopted by one of the herds in Buffalo Springs. Now she was a young female with a new baby, and, with poaching still rife, scientists from Save the Elephants were keeping a close watch. When the film crew arrived, however, her herd was troubled, not from poachers, but the weather. This part of Africa was suffering from a prolonged drought. It had not rained in four months. The wet season should have arrived, but Raine and her herd had not felt a drop. With rivers dry and vegetation dying, the elephants were forced to move out of their protected area in search of food and water. This left them vulnerable to illegal hunters, and could have brought them into conflict with farmers if the animals had tried to feed on their crops.

Fortunately for Raine, the matriarch of her herd is Cyclone; an experienced and resourceful grandmother. She led the herd to the Nakuprat Goto Conservancy on high ground where a little rain had fallen. Here, farmers are tolerant of elephants, so herds use the area more freely. Cyclone had been in that area before. She knew it would be a safe place to lead her herd, but then the weather changed.

Weather satellites showed clouds gathering, swirling and darkening. Rain fell, and everyone was expecting Cyclone to head back home, but she did not: she stayed put. It turned out this was no ordinary rainstorm, and the film crew on the ground found out just what was about to be unleashed.

Torrential rain fell continuously for many hours – not in Buffalo Springs itself but in the hills some distance away. Water raced down watercourses, causing flash floods on the dry, concrete-hard ground. Suddenly, many parts of Buffalo Springs and Samburu were flooded, including the film crew’s quarters. However, Cyclone’s herd was safe in the hills. Had she sensed what was about to happen from past experience, and knew just what to do? We’ll probably never know, of course, but we can make an educated guess.

Elephants have impressive memories enabling them to create mental maps that indicate the whereabouts of the best waterholes and worst hazards. They may not have the benefit of weather satellites like we do, but they are incredible weather forecasters. Elephants have a keen sense of smell. It is thought they can sense water several kilometres away. Without Cyclone’s memory and super senses her herd and its precious baby may not have survived the drought or flooding. Only she could keep one step ahead and her knowledge, which she passes to the adopted Raine and her new baby, should keep future generations of this herd safe in the difficult times that will inevitably come.

Buffalo Springs, while hot and dry for much of the year, is a relatively benign place to live compared to the conditions that elephants experience in the Sahel on the southern edge of the Sahara. In the landlocked state of Mali, just to the southeast of Timbuktu, they live in such harsh conditions that they must trek enormous distances and, like Cyclone in East Africa, use their incredible memory and keen senses to find sufficient food and water.

During the past few years, scientists have been following this migration, using all the methods available to them, including satellite surveillance. They track the elephants and plot the locations of permanent and temporary water sources that the herds visit regularly. These elephants, however, are skittish, and for good reason. In recent years, they have not only lived in a war zone, but, like their East African relatives, they are being killed for their ivory, with more than 163 slaughtered since 2012, so they are not easy to follow. They hide from people in acacia scrub by day, resuming their migration at night, but, despite the difficulties, the details of their journeys are slowly being unravelled.

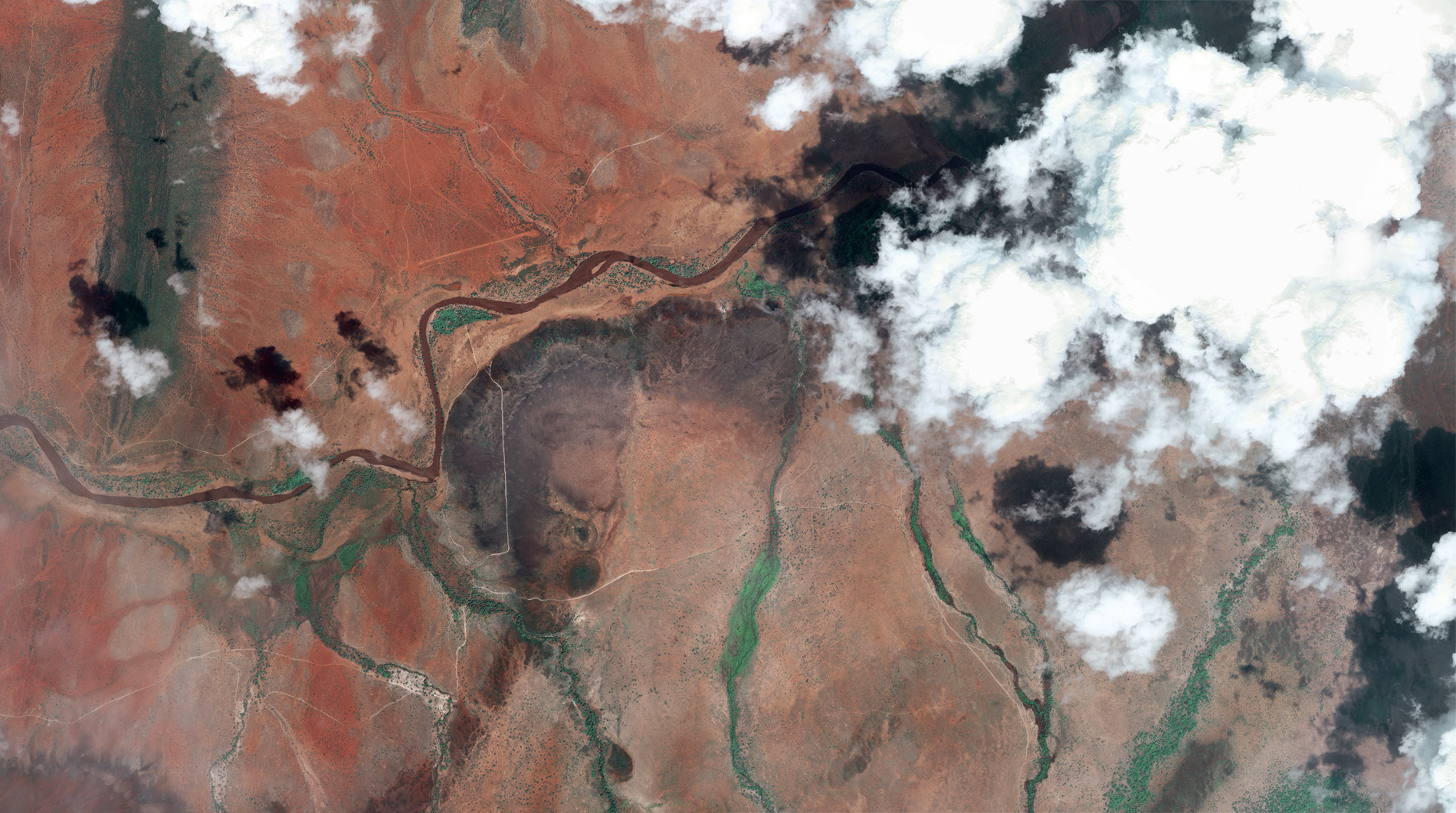

North Africa’s elephants, the sub-species that gave rise to the war elephants of Carthage, are extinct, so the Mali elephants are now the most northerly population in Africa, and they travel a vast counterclockwise path covering 32,000 square kilometres of Mali’s Gourma. It is the largest known elephant migration circuit, one-and-a-half times greater than the area trekked by Namibia’s desert elephants. At the height of the dry season they can travel as many as 56 kilometres in a day.

Bulls follow different routes from cows and calves – probably because males are more tolerant of people and take more risks – and they all travel so far and so often because conditions are so hostile. The midday air temperature often rises to 50°C, and there is no guarantee that their next waterhole will actually have water. They linger regularly at Lake Banzena in the northeastern part of their range to take advantage of the rains in June, but in 2009 there were no rains and the lake dried out completely. It is a wonder that any survived, but survive they have, about 350 of them; the remnants of a population of many hundreds of elephants that once roamed right across the Sahel. Their land is like a dustbowl, where the dust is whipped up by gusts of wind that transport it high into the atmosphere and out of Africa.

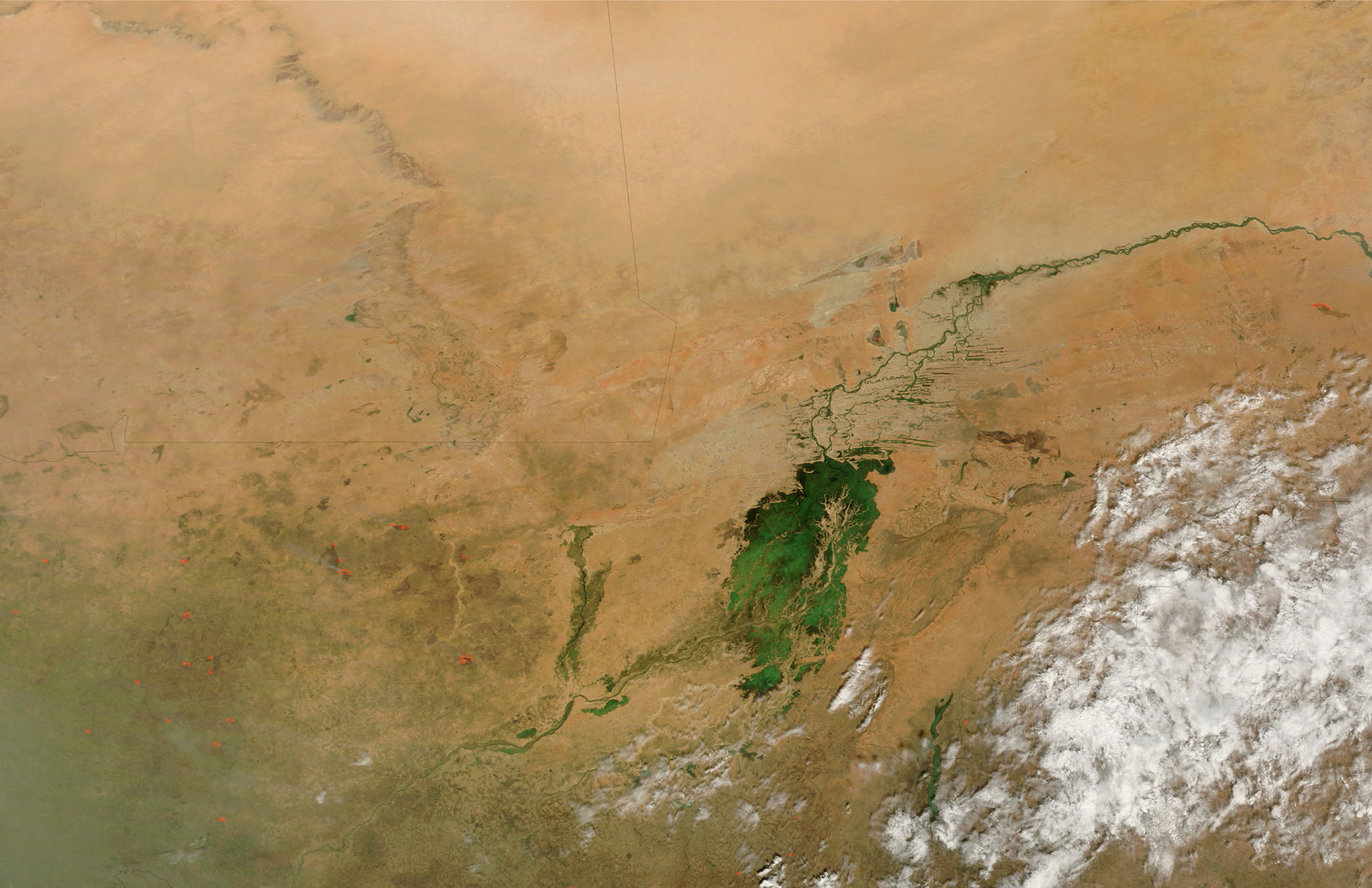

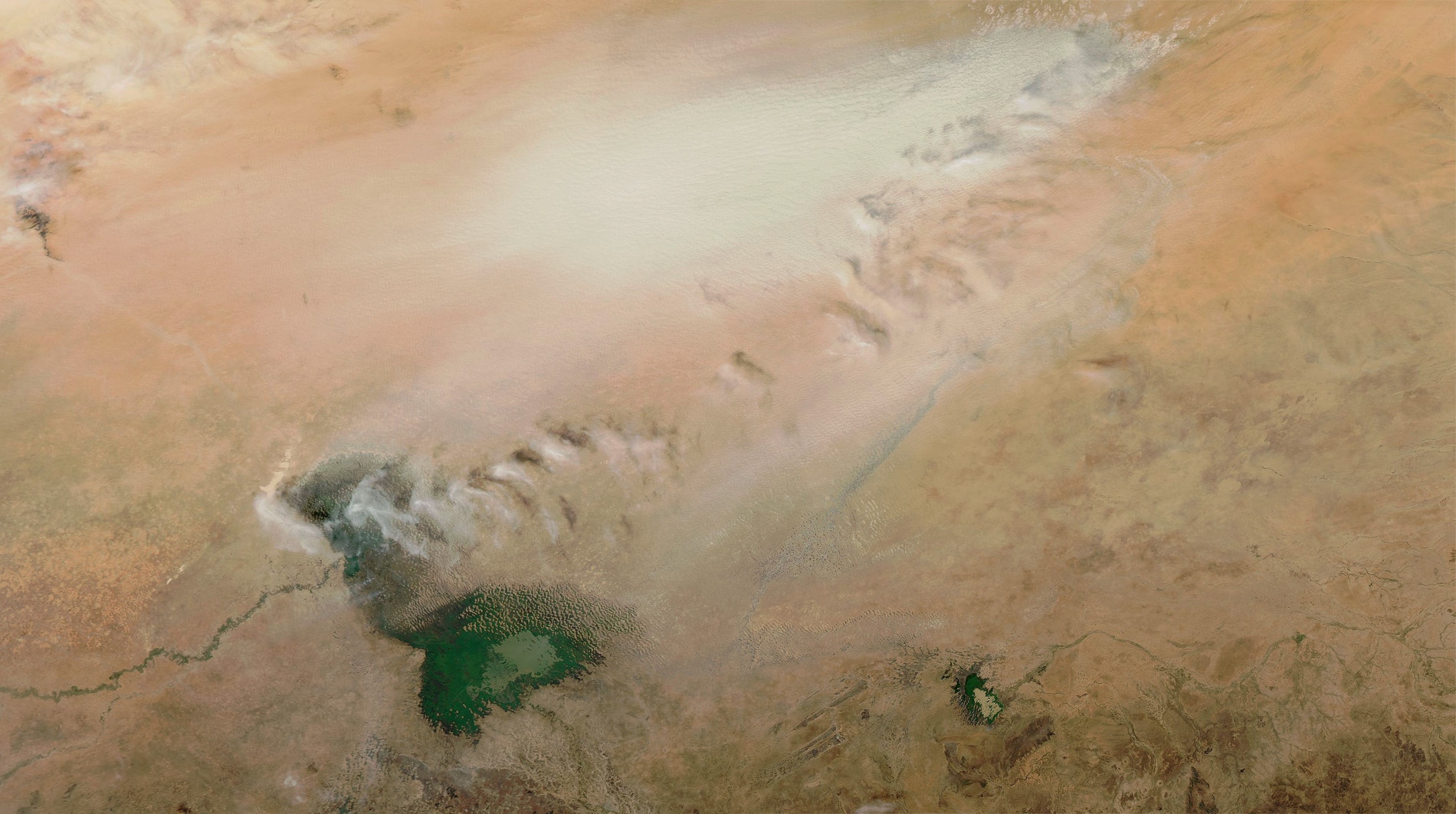

NASA’s Terra and Aqua satellites have tracked dust from the Sahel and Sahara and found that one of the main sources is in Chad’s Bodélé Depression. It was once part of a greatly enlarged Lake Chad – the paleolake Megachad, the largest lake on the planet 7,000 years ago – but natural climate change, lack of rain and an increased demand for irrigation water shrank shorelines to the point that the lake is little more than 1 percent of its former size. The dried bottom sediments, where the tiny skeletons of long-dead freshwater organisms, such as diatoms, have accumulated in huge quantities, are rich in phosphorus and iron. It is a deep layer of ancient dust covering an area of 10,800 square kilometres, about half the size of Wales, but it is not staying.

Surface winds, which are squeezed and accelerated through the narrow gap between the Tibesti Mountains and the Ennedi Massif, can be so powerful that they scoop up the dust into gigantic dust storms. During the winter months, they can shift up to 700,000 tonnes per day on average, leaving a huge scar on the ground that can be seen from space. From satellites we can watch this huge mass as it is lifted and carried thousands of kilometres across the Atlantic Ocean, an extraordinary journey with an even more surprising destination. Over South America the dust particles latch onto water droplets in the clouds, so every year 40 million tonnes of desert dust falls with the rain over the Amazon rainforest.

Amazon rainforest soils are poor in nutrients. Most are locked up in the plants themselves or washed into rivers by heavy rains, so the desert dust supplies essential minerals needed to maintain the forest, which, despite extensive logging, is still the largest and richest tropical rainforest in the world. It is a biodiversity hotspot, home to 10 percent of known plant and animal species and probably a whole lot more that have still to be discovered. On average, a new species is recorded here every couple of days. It is said that there are more species of ant in a single tree in the Amazon than there are in an entire country elsewhere. Without this long-standing, long-distance movement of mineral-rich dust from the southern Sahara, one of the greatest natural habitats on our planet might not exist.

It has been estimated that the top four metres of dust has been removed from the lakebed during the past 1,000 years; much of it blown to South America, the rest dumped on the Caribbean and southeast United States. It is likely to last for another 1,000 years, part of an essential cycle of dust that is whizzing around the world … and not only rainforests benefit.

About 75 percent of global dust is deposited on land, while the other 25 percent drops into the ocean, where organisms that make up the phytoplankton utilise the minerals. So, just as we have the large-scale movement of air and water around our planet, we also have the wholesale movement of dust, and, like the Sahara dust, landfall can be a considerable distance from the source. Dust originating in Central Asia, for example, is carried over the Pacific Ocean as far as the west coast of North America, and, from North Africa, red Sahara dust sometimes reaches the British Isles. The winds blowing these dust clouds across the world, however, can be so powerful that, instead of seeding new life, they bring devastation and death.

Highly destructive North Atlantic hurricanes begin their life as far to the east as the Cape Verde Islands, off the northwest coast of Africa. Between 1st June and 30th November, on average, a dozen hurricanes push in towards the islands of the Caribbean and the southern coasts of North America. Watching their every move are not only weather satellites, but also the storm chasers: United States Air Force 53rd Weather Reconnaissance Squadron, nicknamed the ‘Hurricane Hunters’. Major Kendall Dunn is one of its intrepid pilots.

‘It is psychologically a bit of a strange feeling, flying deliberately toward one of the most destructive forces seen on our planet, but without us, those on the ground would have no idea what’s about to hit them.’

At first, the strength and composition of an approaching storm has still to be determined. It is up to Major Dunn and his crews to fly in and check out what they are dealing with.

‘If you’re the first plane in, you’re basically the pioneer. The satellites got a good picture, but until you get into that storm, no one really knows. Once you fly through it, and you get back, and you look at that radar picture again, you give Mother Nature much respect.’

And, although the storm itself is chaotic, the survey is not. The aircraft follows a well-rehearsed track; but even so, the hunters are going into the unknown.

‘When we fly these storms, we fly a huge X-pattern, each leg about 105 nautical miles long, collecting data the entire time. Different parts of the storm are going to be stronger, and we don’t necessarily know that until we get in. You don’t really know somebody until you give then a big hug – and we’re basically out there hugging storms; and, once we get out there and do that, we know them pretty intimately.’

Viewed from a satellite the hurricane is a gigantic, grey spiral of cloud, but from an aircraft actually in the eye of the storm, it can be a place of breathtaking beauty: a circle of blue sky above, surrounded by a vertical wall of menacing blackness. Passing through the eyewall, updrafts and downdrafts can cause the aircraft to gain or lose height dramatically, seeing even the most seasoned storm chaser reaching for the sick bag.

‘The airplane itself is just bouncing back and forth,’ Major Dunn explains. ‘The rain is sheeting off. It basically looks like you’re underwater!’

Within the storm itself, winds can reach 200 mph and, on the surface of the ocean below, waves can be more than 10 metres high. Everything in the hurricane’s path must either flee or batten down the hatches.

On Florida’s Gulf coast, the extensive bright white sand dunes on Santa Rosa Island sometimes feel the full fury of an incoming storm, not only from the devastating winds, but also from the storm surge – a wall of water that builds up ahead of the hurricane. It pushes in from the Gulf of Mexico, and can be several metres above the normal sea level. The storm surge that accompanied Hurricane Katrina in 2005 put 80 percent of New Orleans underwater. With very little between the ocean and the Florida dunes to buffer the combined impact of wind and waves, wildlife and humans alike can be in mortal danger.

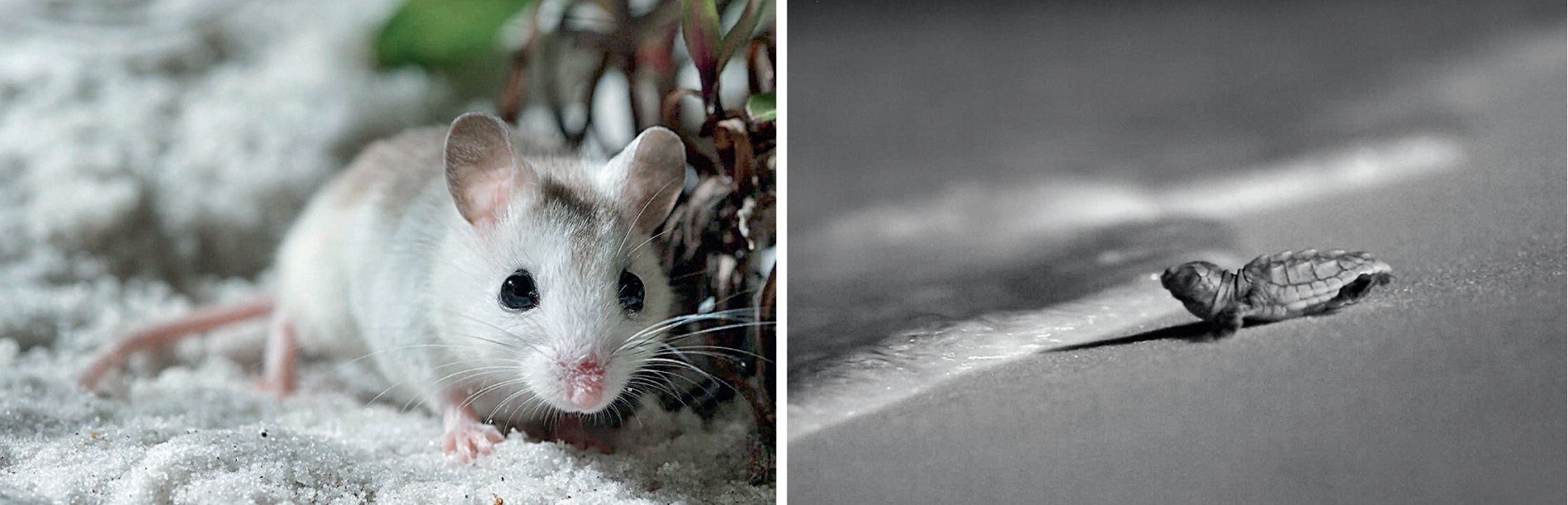

Living here are not only wealthy American retirees with holiday homes beside the sea, but also the mainly nocturnal beach mouse. There are several sub-species and Santa Rosa Island’s population is relatively healthy, but others, also confined to the dunes on Florida’s low-lying barrier islands, are vulnerable, mainly due to habitat loss and the pressure from tourism. One unfortunately placed hurricane could wipe out a sub-species overnight.

When the Earth from Space film crew were in Florida filming the mice, news came in that a storm was brewing in the Gulf. It was the timing that series producer Chloë Sarosh and her teams had hoped for.

‘It was our ambition to show the movement of a hurricane through the eyes of a tiny character, but there were so many variables. Would there be a storm at all? Would it travel towards the coast or head off in the wrong direction? With a film crew on the ground, and another in the air, we just had to wait and see what the storm would do.’

And they didn’t have to wait long. A camera team scrambled with the Hurricane Hunters, and, as they flew towards the eye, it became apparent that this wasn’t just any storm. It was increasing in intensity. The dunes with their dune mice appeared to be right in its path. It was time for life on the ground to hunker down.

While the winds on the coast were strengthening and the surf was up, Barny Revill’s film crew in the air was flying right through the heart of the storm.

‘We were filming on the flight that upgraded the hurricane from Category 1 to Category 2. It was becoming a serious storm. In the next 24 hours, it went from Category 3 to Category 4, and, of course, by then it had a name.’

The team watched Hurricane Harvey’s progress via satellite, and it became clear that it would not make landfall on the Florida coast. The film crew in the dunes breathed a sigh of relief. Harvey made landfall further along the Gulf coast in Texas, the first major storm to hit the US mainland in 12 years.

‘It was shocking to see the news roll in,’ recalls Chloë. ‘This storm, which we had assumed to be small, just grew and became more powerful as we watched it. We gathered satellite images that showed us the extent of the damage in Texas. We had hoped to be able to tell the story of an animal’s life in a precarious habitat, but we never expected to be in the eye of the biggest storm in a decade. It was a sobering reminder of the awesome power of nature.’

On their Florida islands, however, the little beach mice were safe, and, to top it all, they had some new neighbours, but they were not sticking around to enjoy the view.

Emerging from nests below the sand were loggerhead turtle hatchlings. Most appeared during the night, when predators were fewer, and they headed instinctively towards the sea, guided by the intensity of light over the ocean. They were embarking on an epic journey, during which they swim frantically to the open ocean. Here, they hide amongst floating seaweeds and ride the ocean currents for, in the big blue, predators are probably less concentrated than on the coast. The currents then carry these youngsters around the globe. By hitchhiking on the North Atlantic Sub-Tropical Gyre, some loggerhead sea turtles make at least one circuit of the North Atlantic, before returning to the same stretch of coastline where they hatched out ten years before.

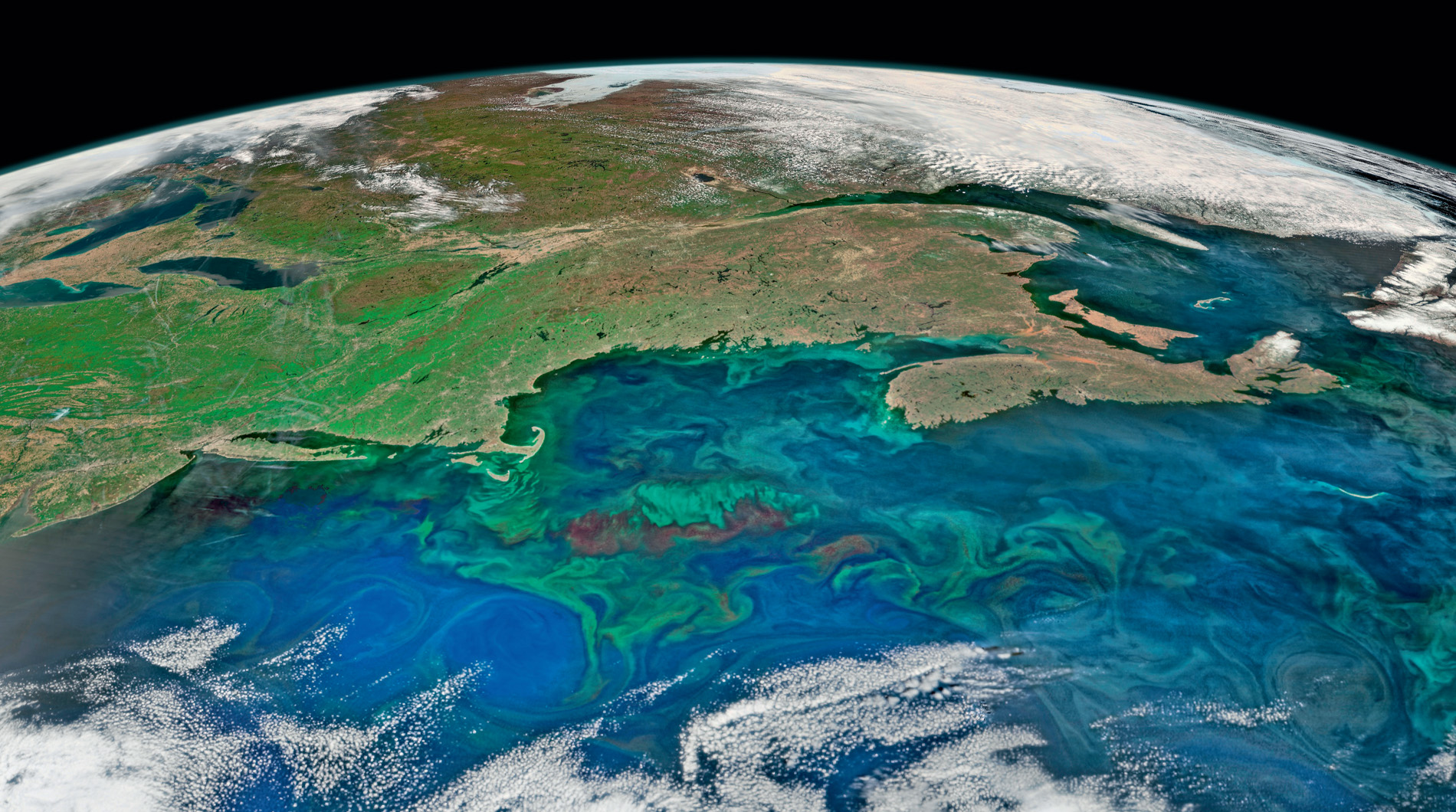

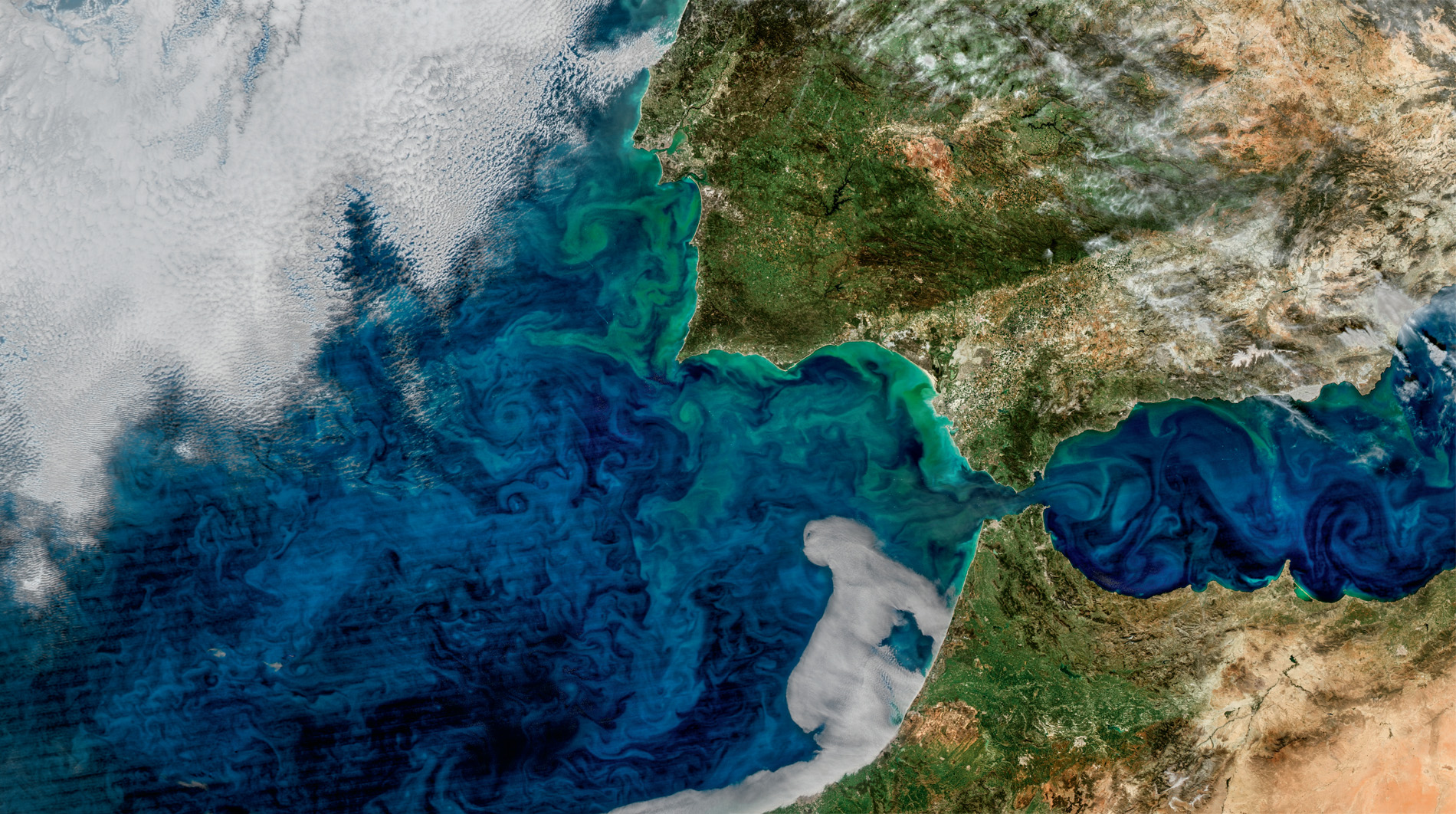

Driven by the prevailing winds, the ocean currents on which the baby sea turtles ride are effectively invisible, but they can be tracked from space, using data from drifting buoys and satellites in Earth’s orbit. They reveal both the order and the chaos of the world’s oceans and seas. At the surface, there are fast-flowing ‘rivers’, such as the Kuroshio in the Pacific and the Gulf Stream in the Atlantic. They move vast quantities of water, heat, nutrients – and baby sea turtles – for thousands of kilometres across the globe, while hundreds of localised slow-moving pools or eddies, resembling giant whirlpools in the ocean, swirl along the edges of continents and into gulfs and bays. It is all part of the ‘global conveyor belt’ that connects all the world’s oceans and seas, and those currents are not only highways for baby sea turtles and other marine animals on migration: people take advantage of them too.

Ships can increase their speed and save fuel by riding with the current, and, when travelling in the opposite direction, instead of fighting the current, they find a route that circumvents it. As early as 1769, Benjamin Franklin published a chart showing the whereabouts of the Gulf Stream, which helped navigators find the best routes between Europe and the USA. More recently, scientists have been able to put some numbers on Franklin’s assertions. Travelling at 16 knots, a ship can save 7.5 percent of its fuel when riding with the Gulf Stream, while saving about 4.5 percent when avoiding it in the opposite direction. With 90 percent of world trade carried by about 70,000 ships worldwide, this can make a significant dent in fossil fuel consumption. Oceanographers and shipping companies are now looking at the other ocean currents for energy-saving routes, as well as avoiding adverse winds, high waves, ice and fog, and that’s not all. Another fuel-saving initiative is ‘super-slow steaming’; with ships pootling along at speeds as slow as 12 knots, which means modern cargo ships take roughly the same time as 19th-century clipper ships to complete long-distance journeys.

From space, these ships appear as tiny spots of colour, the most kaleidoscopic being the giant container ships with their brightly painted shipping containers. The Earth from Space team had an interest in one in particular. It was travelling from Shanghai to Southampton, one of its containers carrying a special cargo. After leaving Shanghai and crossing first the East China Sea and then the South China Sea, the ship squeezed through the congested Straits of Malacca, before riding the North Equatorial Current across the Indian Ocean. It joined the queue for the Suez Canal, travelled the length of the Mediterranean, and finally tried to avoid the southward-flowing section of the North Atlantic Gyre to the English Channel – a journey of about 36 days.

At Southampton, the container was loaded onto a truck and taken by road to Nottingham’s Wollaton Hall, home to the city’s natural history collection. Carefully packed away in the shipping container were the skeletons of dinosaurs. One was Gigantoraptor, discovered in what is now Inner Mongolia. At eight metres long, it was one of the world’s largest feathered theropod dinosaurs. Another skeleton was even bigger, a monstrous sauropod dinosaur with the tongue-twisting name Mamenchisaurus. It is instantly recognisable by its exceptionally long neck, even for sauropods – nearly half of its total body length. The largest specimens are 35 metres long, and, when alive about 150 million years ago, they probably weighed about 45 tonnes. They were part of the ‘Dinosaurs of China’ exhibition, and they were brought to Nottingham with the help of one of the largest movements on the planet – the ocean currents.

The ebb and flow of the tide is another water movement that that can be monitored, and, in one way, has its origin in space. Contrary to popular belief, the Moon is not the sole influence on the tides. If it were, there would only be one high tide a day as the Earth rotated and the Moon’s gravitational pull caused a bulge of the ocean to travel around the world; but many places experience two tides a day. This is due to the Earth also moving in a circle, producing a centrifugal force that causes another bulge to form on the opposite side of the Earth to the Moon. The result generally is two high and two low tides every 24 hours and 50 minutes, the 50 minutes representing the distance the Moon progresses each day whilst orbiting the Earth.

The Sun is also part of the picture, but because it is so far away its influence is considerably less than that of the Moon. Even so, its presence can be noticed at the spring and autumn equinoxes, when the two space bodies line up, causing unusually high or low tides, known as ‘spring tides’. To complicate matters even more, some places, such as the Gulf of Mexico, experience only one high and low tide a day, whilst others, such as parts of the Baltic and Mediterranean, have little tidal movement at all. These variations are due to the unique shape of the land bordering or surrounding the sea, but, whatever the pattern, when satellite pictures of the tidal rise and fall are sped up, it looks as if the Earth is actually breathing.

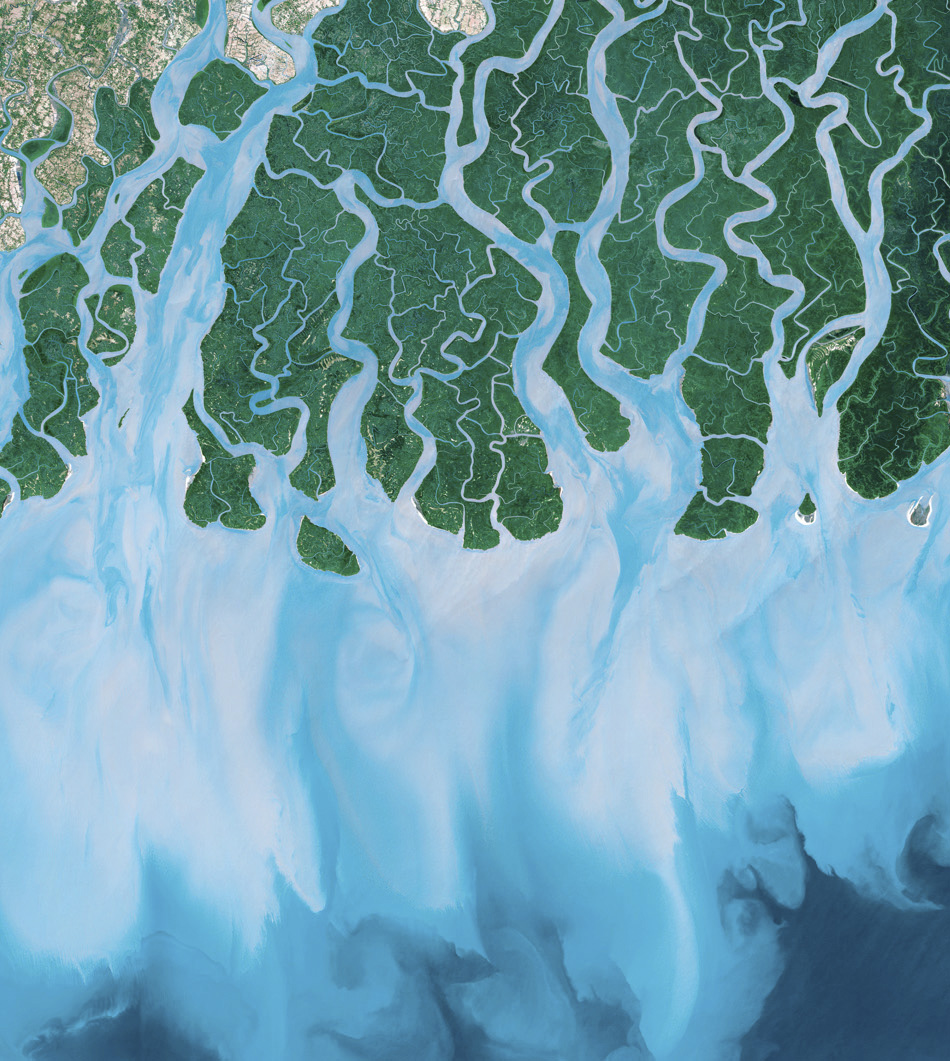

One of the places on Earth where the daily lives of people and wildlife are greatly influenced by the movement of the tides is the Sundarbans of Bangladesh and India’s West Bengal. The name means ‘beautiful forest’ and it is aptly named. Bordering the Bay of Bengal, where the land meets the sea and freshwater meets salt, it is one of the largest tracts of mangrove forest in the world. Most of the land consists of low-lying islands, each little more than a few metres above sea level, with a complex network of waterways bordered by muddy shores in between. It is home to the smooth-coated otter.

Learning to fish is an important life skill for a wild baby otter, but here, in the tidal channels of the Sundarbans, Bangladeshi fisherman Bhoben Biswash and his son Rhidoy carefully supervise these lessons. They and the rest of their family train an eager team of boisterous otters to help them catch fish. Their village is in the northern Sundarbans, where the coming and going of the sea determines the pace of life and supports this unusual method of fishing. It is a way to catch fish that has been handed down from father to son for centuries.

‘I’m a fisherman, my father was a fisherman, and his father before him,’ Bhoben points out. ‘It’s how we’ve always made a living here. And now I try to teach my son, but he’s a teenager … a bit lazy.’

The trained otters are secured to the boat or attached to long bamboo poles by a simple harness and string. Youngsters swim freely with the older animals while learning the ropes. Bhoben uses the otter’s natural hunting instincts to find the fish in the muddy river and chase them towards the boat where the fishermen are ready with their net.

The tides are crucial to their success. At high tide, the fish are thinly spread throughout the waterway system, but as the water level falls, they’re forced into the main channels where the fishermen are waiting. In go the otters, driving the fish into the net. With the otters’ help, far more fish are landed than if the fishermen were fishing alone. And they all receive a reward.

‘We have to give them half our catch – that’s the deal,’ says Bhoben. ‘They’re like family, but they eat better than I do!’

The question is: for how much longer? Men and otters have been fishing together for hundreds of years – the earliest reference is from the Tang Dynasty of China in the seventh century CE. It was also once common in India and Europe, including the British Isles, but nowadays only Bangladeshis fish with otters, although even here there are only a handful of otter fishing boats remaining across the entire Sundarbans. Bhoben’s family and the other fishermen are slowly being pushed out. Large-scale fisheries are mopping up the fish and driving down prices at market and widespread pollution in the delta means that fish are harder to come by. Nevertheless, Bhoben continues to look after his otters, and, by doing so, he has become an inadvertent conservationist, nurturing a mammal species threatened by the loss of its wetland habitat.

Although life in the Sundarbans revolves around the tides, the land and waterways were created with the help of a powerful seasonal force – the monsoon. The wet part of the monsoon cycle occurs because the land and sea absorb heat in different ways. In the warmer months, land temperature rises more quickly than that of the sea. Hot air rises, so low pressure exists over the land, while high pressure sits over the sea. The result is that rain-laden winds blow from the sea to the land, similar to sea breezes on British coasts except they are much greater in intensity, and they dump enormous quantities of water. Indeed, the wettest place on Earth is to the northeast of the Sundarbans, a cluster of hamlets in India called Mawsynram. They sit on a plateau overlooking the plains of Bangladesh. Moisture is swept in from the Bay of Bengal, producing an average annual rainfall of 11,871 millimetres (compared to an average of 3,784 millimetres in Snowdonia, the wettest region in the British Isles).

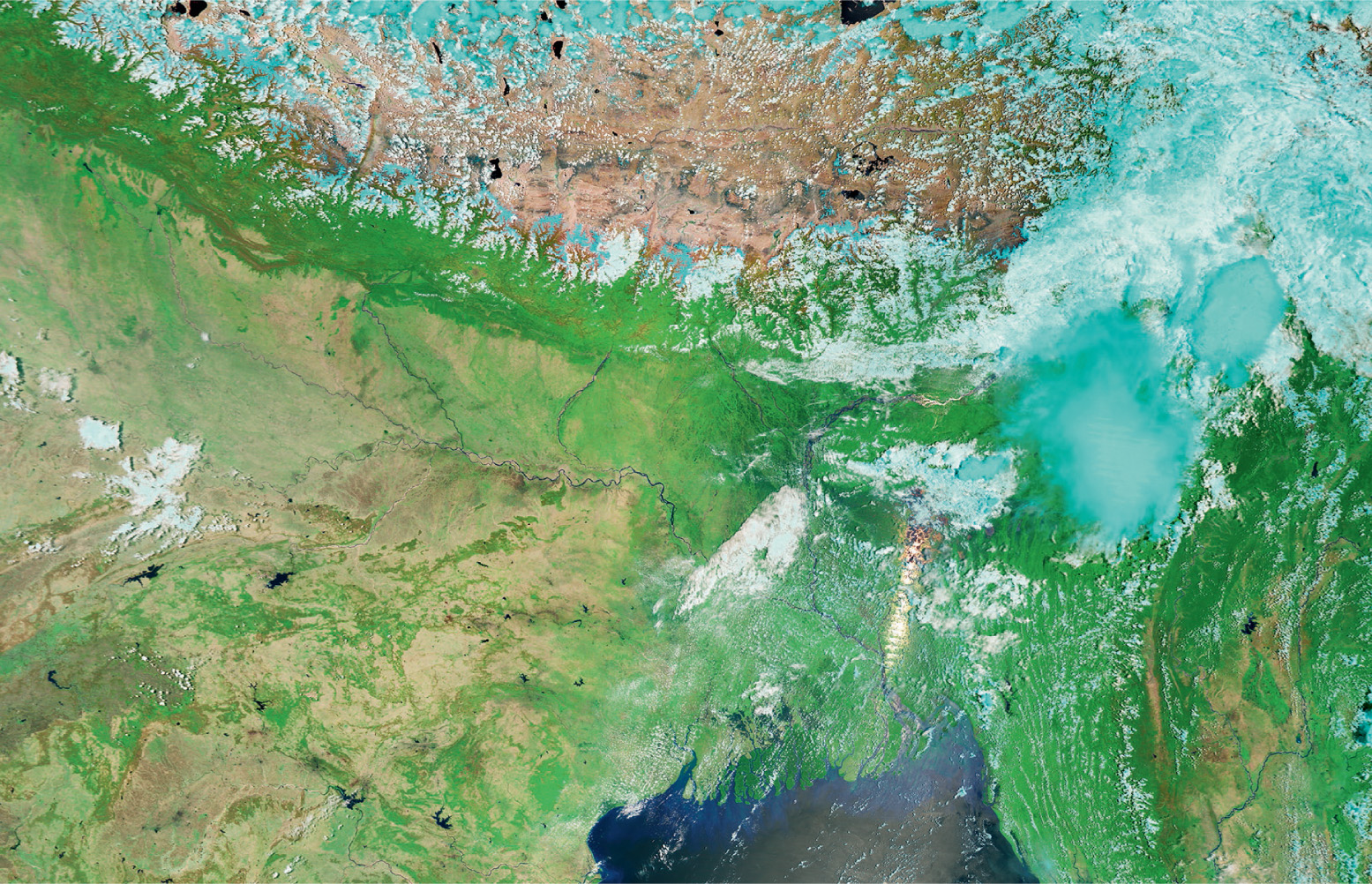

From space we can see rivers change from silver to brown, as ‘bursts’ of the monsoon unload the rain, and the floodwaters carry silts and sediments from the Himalayas in the north down towards the sea in Bangladesh. Much of it settles in a huge delta that fans out into the bay, part of which constitutes the Sundarbans. Much of the silt is trapped by the tangle of mangrove roots. They also prevent it from being washed away again. This ‘bio-shield’ protects the Sundarbans, its people and its wildlife from the powerful tropical storms that frequent the region many times each year.

A very different kind of delta is found in Botswana, in southern Africa. Here, rainfall occurs in two distinct seasons – wet and dry – and both seasons have a profound effect on the country’s wildlife.

Like the elephants of Mali and Buffalo Springs, both floods and droughts pose a serious challenge to life in Botswana. An exceptional dry season, for example, can see hippopotamuses crammed together in rapidly disappearing lakes and pools, causing epic fights to break out between neighbours. Salvation arrives from some distance away.

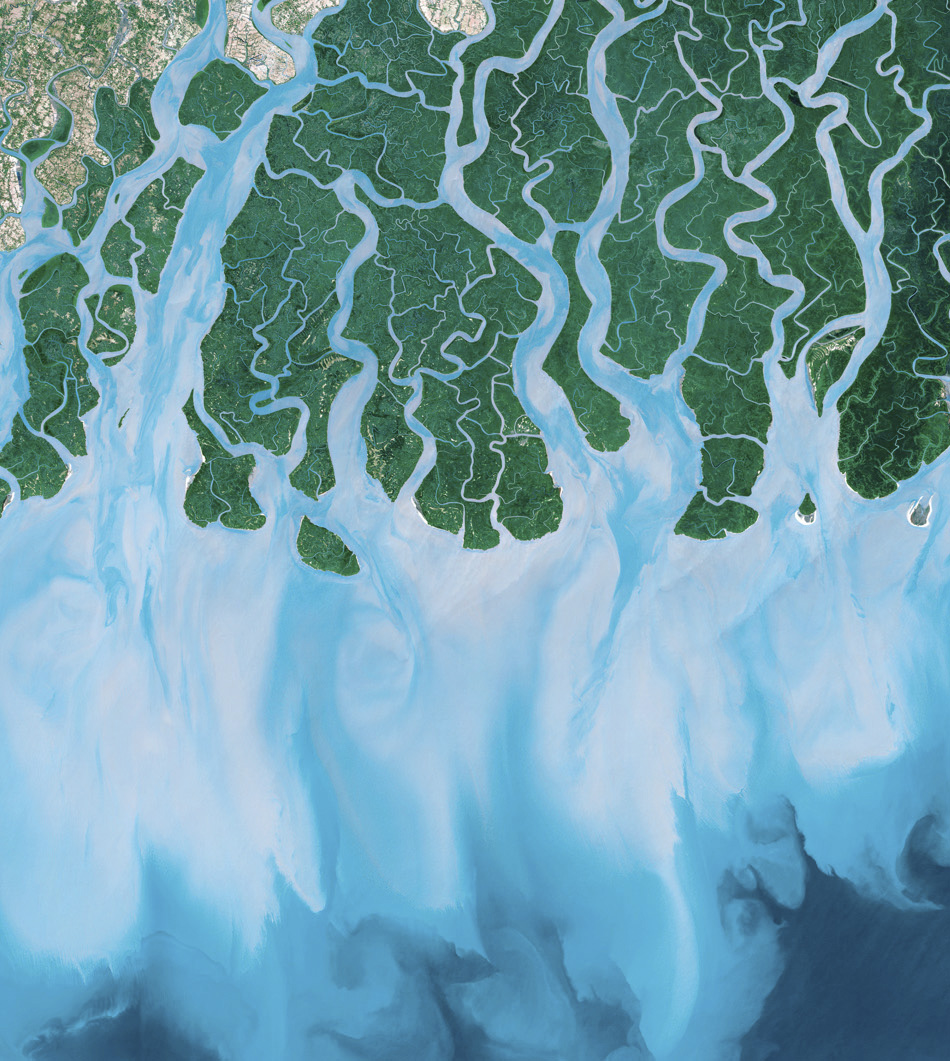

When rain falls in the Angolan highlands 16,000 kilometres to the north, the water eventually tumbles down rivers that do not flow into the sea, but onto the vast plain in Botswana known as the Okavango Delta. From space the progression of the water can be followed as the delta is transformed from a scorching desert into an inland wetland area and wildlife paradise. The hippos take full advantage of the water, following familiar routes through the swamp and creating distinct pathways.

Other large mammals, including buffalo and savannah elephants, also plough through the swamp, but their routes are different from those of hippos. Viewed from space, the direction of the route tells us which animal has made it. Elephants walk directly between islands, so their paths tend to be perpendicular to the gradient, while hippos follow the flow of water and so walk parallel to the slope. This makes them useful bio-engineers. Their pathways are thought to alter patterns of water flow, so water reaches parts of the delta that may not have been penetrated before, which is important to the huge numbers of animals that pour in from all points of the compass when the whole area floods.

Animals are on the move across our planet for a variety of reasons – to find a mate, rear young or leave a crowded living space – although, often as not, the whereabouts of seasonally abundant food is the main stimulus that triggers everything else. Some travel enormous distance, like the Arctic tern that embarks on an annual round trip of 70,900 kilometres between Greenland in the northern hemisphere and the Weddell Sea in the Antarctic, the longest of any animal. But if there was ever an ideal animal to track across the globe using satellite imagery, it is one as big as a great baleen whale … at least, when it is at or near the surface.

Southern right whales enter shallow bays to mate and give birth at Península Valdés in Argentina. Here they have been counted using the WorldView2 satellite. It was the first successful study of its kind, and since then there have been several others. Gray whales, which give birth in the San Ignacio Lagoon in Mexico’s Baja California, have been counted from satellites that are 480 kilometres up, and humpback whales have been scrutinised in a similar way as they gather off Maui in Hawaii. Now satellite imagery is revealing more about the life of the fin whale.

It may come as bit of a surprise to learn that, not far from where they spend their summer holidays on the Italian Riviera, many people share the water with the world’s second largest animal. A little way offshore from the holiday beaches is the Pelagos Sanctuary for Mediterranean Marine Mammals. It is where fin whales spend their summers too. Here, a current flowing northwards past Tuscany and Corsica and along the coast of Liguria and mainland France creates a permanent frontal system between coastal and offshore waters where there is considerable biological activity. Northwesterly winds, known as the ‘mistral’, drive upwellings that, together with the vertical mixing of waters, bring up nutrients from the deep. Satellite data has revealed that this is where the phytoplankton blooms. These organisms support the zooplankton, such as northern krill, which, in turn, is food for whales, so this sector of the Mediterranean has become one of their primary summer feeding sites.

In winter, food is less concentrated in the sanctuary so the whales move elsewhere. Some of them head for the island of Lampedusa in the Strait of Sicily, where they feed actively both to the north and the south of the island. The problem is that wherever they are, whether it be feeding or migrating, they are crossing busy shipping lanes, such as the high volumes of traffic between the Suez Canal and Straits of Gibraltar that passes to the south of Lampedusa. There is the constant danger of ship strikes, and this population of whales has a higher than average rate of injuries or deaths from collisions. However, knowing where the whales are and where they travel could lead to changes in maritime law, and maybe even the introduction of restrictions on the movements of ships. Fin whales are classified as ‘endangered’ by IUCN, but this kind of study could be their salvation. Observing the great whales and their food sources from space is a new and exciting development, and it could help to ensure they actually have a future.

Observing individual people from space is not as easy as watching a whale, although military reconnaissance satellites, better known as ‘spies in the sky’, are thought to be able to resolve something as small as 12–15 centimetres across, and that’s from a satellite orbiting more than 300 kilometres above the Earth’s surface. It might not be able to read the number on your house, but it can identify the make of car standing outside. Commercial satellites are getting close to this kind of resolution, and the shapes and patterns they can see are attention-grabbing, especially when large numbers of people are all moving together. For this, the Earth from Space team went to China.

‘Every day, we wake at 5am,’ says a bleary-eyed Ching-Yiu, an alarm ringing loudly somewhere nearby. ‘When I first arrived, it was really difficult to get up, but now it’s not so bad. When the coach calls us, we do as he says.’

Ching-Yiu is just 13 years old and attends a martial arts academy in Dengfeng, in China’s central Henan Province. He is one of 35,000 boys who are trying to master Shaolin Wushu, which combines martial arts with Buddhism. Its records can be traced back to 495 CE, and the course today is extremely tough, just as it was over 1,500 years ago.

‘In winter, it’s so dark. It’s doesn’t feel like the right time to wake up, but we have to train. It’s freezing cold at the beginning, but when we start warming up, it’s alright.’

Outside, it was a misty morning, and you could see the breath of each of the young students as they wandered across the yard for breakfast.

‘We train for one hour in the early morning and then there are two classes.’

The group came to order and, army style, Ching-Yiu shouted out his number, and the group marched off, chanting as they went.

Kung fu means literally a discipline or skill achieved through hard work and practice, and is not specifically applied to martial arts, but for Ching-Yiu it will take years of dedication, discipline and relentless training to achieve his goals.

‘When we’re training together, there are sad times and happy times. When someone can’t do it, we teach each other, and offer each other encouragement.’

But what does Ching-Yiu want to achieve from all this? What does he want to be when he graduates?

‘Some kids say they want to be soldiers when they reach 18 or 19, but most of us want to be kung fu stars. I saw all of these heroes and villains on TV running up walls and doing somersaults, and I wanted to learn that too!’

But it’s not all discipline. The students play-fight and mess around like all kids.

‘My classmates and I are like brothers,’ says Ching-Liu. ‘We go out and play together. When I feel sad, I can share it with them, and when I’m happy, I share it with them.’

The children are taught at the school all year round, during which time they perform at special events and competitions right across China, but there is one epic performance for which the school is now famous.

‘We only have the performance for special days. Whenever there’s a special occasion, or if a leader or VIP comes to visit, we’ll put on a big performance so they can see Chinese kung fu. If just one person makes a mistake, the entire team has to do it again.’

And, while the members of the Earth from Space film crew were at Dengfeng, they were fortunate enough to be invited to watch and film events as they unfolded. For Ching-Yiu, the pressure was enormous. He had to remember all the moves he had learned, right down to the perfect angle of his arms, the placement of his feet, and the timing of his jumps … every detail mattered.

‘This huge performance is so that we can all train as though we are one spirit. The whole school comes together as one, and we can show our greatness to the school and to our families.’

And, when the big day came, the students performed together at the main event. Their mass movements, in perfect synchrony, created ever-changing shapes and patterns, and, when seen from above, they really did move as one. The display was a huge success, a triumph of coordination and rhythm, a demonstration of how the body can work in harmony with the brain to produce some of the most exquisite patterns and movements on Earth.

With the performance finished, Ching-Yiu was ready to go home for the holidays. ‘Spring Festival is when we go home and visit our parents and family to spend the New Year with them. People from all over the country come back home to have a feast with their parents.’

Faced with a daunting 1,300-kilometre journey, Ching-Yiu said goodbye to his friends and he joined the largest movement of people on the planet.

Every January or February, almost a billion people all across the country, representing about one sixth of the world’s population, together with expatriates from around the world, return home to be with family and friends at this special time. During the holiday period, they make more than 2.5 billion excursions by road, 58 million by air, 43 million by sea, and they buy 356 million rail tickets. The travel phenomenon is known as the ‘Chunyun’ period, and it lasts for as long as 40 days. Many travel by road, the lines of cars and buses on motorways clearly visible from space. It is gridlock. At railway stations and airports people are packed in like sardines, all eager to return home.

The Spring Festival is an important date in the calendar. For many, this is the only chance they get to see their relatives all year, and home for Ching-Yiu is Hong Kong. He has to take a flight, board a ferry and ride a tram, and, when he arrives, the streets of his city were bustling with people buying food, flowers and decorations, everybody in a mad rush to get things done.

‘There are so many people around on the streets, and on the buses,’ says Ching-Yiu. ‘They all like to go shopping to buy new clothes, but I’m not used to so many people. I don’t want to go.’

At home, there are traditions to be followed. The family cleans the house thoroughly to sweep away bad luck and make space for good luck, while Ching-Yiu and his sister make a visit to the ‘wishing tree’.

This centuries-old tradition began with two special banyan trees near the Tin Hau Temple in Fong Ma Po village, Lam Tsuen. The custom arose when villagers would throw paper josses into the trees to bring good luck. Today, people write their wishes on a piece of colourful paper, tie it to an orange or kumquat, and then throw it up into the wish tree. If the wish hangs on one of the branches, it is believed that the wish would come true and, the higher the branch, the more likely the wish would be fulfilled.

For Ching-Yiu, it is an opportunity for him to teach his sister about ancient traditions, although the original wishing trees themselves have been forced into the 21st century. In February 2005, one of the branches gave way and injured two people standing underneath, so now the practice is discouraged, and wooden racks have been set up nearby so that people can still make their wishes, or, if they really want to throw, they can attach a wish to a plastic orange and throw it into the branches of a plastic tree. Ching-Yiu went for the plastic tree.

The next day, there is another important ritual to perform. At the Wong Tai Sin temple, Ching-Yiu and his mother join thousands of people who have been waiting in line for hours.

‘We burn incense to wish for good luck and good health for our family. Our family wishes for good health in particular, because we’ve just had a new baby girl. We hope she’ll grow up to be healthy and strong.’

With the tradition performed and prayers offered, it was time in the evening for all the family to gather for a grand dinner. There was a lot to catch up with before Ching-Yiu returned to school, and, like all the other people across China, he and his family were taking full advantage of their time together. It is, after all, the greatest party on Earth.

While people and wildlife are on the move, we sometimes forget that the world itself is moving too, and there’s no better time to experience it than during a solar eclipse. It is a time when looking back at the Earth from space is a whole new experience, and a very special event for two young scientists in Seattle, USA.

At 12 and 10 years old, Rebecca and Kimberley Yeung were probably the youngest people to have taken part in a space programme, but after successfully launching homemade weather balloons – the first reaching an altitude of 23,774 metres, and the second 30,785 metres – they were ready for the big one: to participate in NASA’s Eclipse Ballooning Project in conjunction with the University of Montana.

They had already caught the attention of President Obama, who invited them to his annual science fair at the White House in Washington, DC, and, now, the two young scientists were teaming up with other scientists and enthusiasts from all across the USA to record the solar eclipse. Travelling by road more than 1,760 kilometres east from their hometown, they headed for Casper and the extensive high plains of Wyoming, and they were not alone. There were people pitching tents, parking motor homes and renting every available motel room in the area. Elsewhere in the country, millions of people travelled to areas that would experience totality. They climbed mountains and gathered at stadiums, all ready for the once-in-a-lifetime event.

Rebecca and Kimberley’s project was to release another balloon, and this time it was to carry a camera to the edge of space and photograph the shadow of the Moon upon the Earth. As Rebecca pointed out, the balloon would have a passenger, a small Lego® figure. Its identity was the subject of an online poll.

‘There were three choices: Hermione Granger, Amelia Earhart – the first female pilot to fly solo across the Atlantic Ocean – and Merida, from the movie Brave, and Amelia Earhart won by a landslide. She was a very strong female. She was very brave, and we think she’s a great role model.’

As the girls readied themselves and their balloon, Barny Revill was coordinating film crews along the line of totality.

‘We had six separate teams, spread across three states, including one with a super-long lens for close-ups of the Sun. We also had a 360° camera on a balloon of our own, all for just two-and-a-half minutes of totality. We just needed the skies to stay clear.’

So, on 21st August 2017, Amelia was ready for takeoff, and Barny need not have worried: visibility was near perfect. The sisters’ balloon climbed to 29,374 metres, more than triple the height of Mount Everest, where the onboard thermometer recorded a temperature of minus 63°C. It was one of 50 balloons rising across the country that would record the first total eclipse across America in 99 years. The live streaming from some of the video cameras first revealed the curvature of the Earth, then, at 10.24 precisely in Wyoming, the show began.

Only truly visible from space, a vast shadow swept across the country. All along the route, people felt the temperature drop as they were pitched into darkness. In just one hour and 33 minutes, the shadow passed all the way from the west coast to the east, and out over the Atlantic Ocean. During that time, NASA scientists were not only monitoring the eclipse, but also watching for something that had so far been quite elusive.

Their theory proposes that, as the shadow and the sudden drop in temperature of a total eclipse moves across the planet at supersonic speed, ripples should be produced in the Earth’s atmosphere. The ripples are gravity waves (not to be confused with gravitational waves), and they are similar to the bow waves of a ship, which spread out in its wake. They are important because they are responsible for large-scale energy transport in the Earth’s atmosphere.

During the 2017 eclipse, they recorded 40 separate gravity wave events, of which a few can be directly associated with the eclipse, and the Earth from Space team may have captured one event on video. During the flight, the pictures from the camera can be seen to judder, physical evidence maybe of gravity waves.

Down on the ground, the two sisters were faced with how to get their balloon back. They had to travel some distance over rough terrain to recover it, but when they downloaded the pictures from its onboard camera, they discovered it had all been worth it. Their images showed the Moon’s shadow moving across the Earth. They had achieved their main goals, and with their camera at the edge of space, they (and Amelia, of course) had the best seats in the house.