1

4 JULY 1863

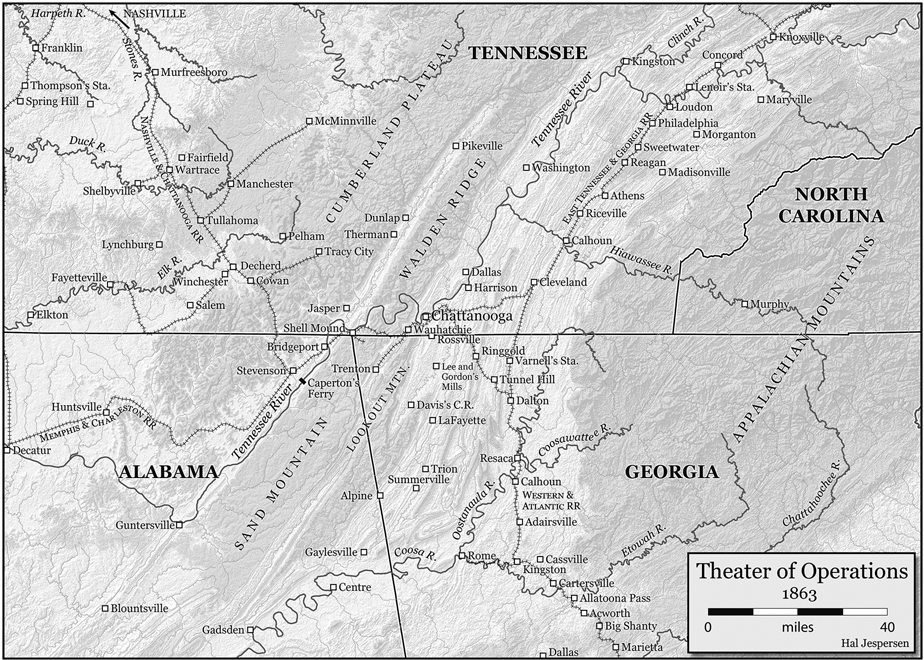

Maj. Gen. Alexander McCook looked at the sky and was greatly disappointed. Instead of glorious summer sunshine, the leaden clouds promised another day of rain. It had rained virtually every day since 24 June, when the Army of the Cumberland had begun its offensive to drive the Army of Tennessee from its foothold around the towns of Shelbyville and Tullahoma. Although the rain had turned the roads into seemingly bottomless seas of mud, the Federals had successfully driven their opponents from the fertile farmland of Middle Tennessee and beyond the frowning heights of the Cumberland Plateau. McCook’s own Twentieth Army Corps, following the line of the Nashville & Chattanooga Railroad, had forded the swollen Elk River with two of its three divisions and was pressing toward the mountain wall visible for miles. Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan’s Third Division occupied the hamlet of Cowan, which lay just short of the long railroad tunnel that took the tracks through the mountain to the Tennessee River valley at Stevenson and Bridgeport, Alabama. Behind Sheridan’s troops, Brig. Gen. Jefferson C. Davis’s First Division occupied the town of Winchester, near the railroad, where McCook established corps headquarters. West of the raging Elk River, Brig. Gen. Richard Johnson’s Second Division settled into the old Confederate fortifications encircling Tullahoma. The momentarily impassable Elk, along with the destruction of the railroad bridge near Estill Springs, ensured that the Army of the Cumberland would soon exhaust its rations, forcing a pause before another advance could begin. To McCook, 4 July seemed a perfect time to have a party. The date was iconic in the history of the nation, the Tullahoma campaign was a resounding success, and the human cost of that success had been minimal. Therefore, McCook reasoned, it was time for a victory celebration. The threatening weather could dampen spirits only so much, so McCook sent invitations to other commands and issued instructions regarding artillery salutes in honor of the day.1

McCook’s nearest neighbor was Maj. Gen. David Stanley’s Cavalry Corps. Although several units were absent, Stanley and his remaining horsemen were camped around the village of Decherd, on the railroad two miles from Winchester. Stanley would have to be invited to McCook’s party. Slightly farther away was Maj. Gen. George Thomas’s Fourteenth Army Corps. Most of Thomas’s command was spread across the fields stretching from the Elk River to the foot of the Cumberland Plateau at the prominent outcropping called Brakefield Point. Maj. Gen. James Negley’s Second Division was nearest to the mountain, with Maj. Gen. Lovell Rousseau’s First Division camped nearby in support. Several miles northwest of Rousseau and much nearer the Elk River, Brig. Gen. John Brannan’s Third Division and Maj. Gen. Joseph Reynolds’s Fourth Division established themselves in the sodden fields and woods. Thomas placed his own headquarters near Brannan and Reynolds, six miles north of Decherd. He was probably too far away to respond favorably to McCook’s invitation, if indeed one was sent. Certainly not invited was Maj. Gen. Thomas Crittenden, commanding the Twenty-First Army Corps. Crittenden’s command was scattered widely west of the Elk River. Brig. Gen. Thomas Wood’s First Division rested at Pelham, fifteen miles northeast of Winchester, while Maj. Gen. John Palmer’s Second Division guarded the flooded Elk Valley north of Morris’s Ford, also fifteen miles distant. Finally, Brig. Gen. Horatio Van Cleve’s Third Division garrisoned Murfreesboro, Woodbury, and Manchester. Crittenden himself occupied Hillsboro, seventeen miles from Winchester. Maj. Gen. Gordon Granger’s Reserve Corps patrolled the army’s rear areas, with its nearest units at Shelbyville and Wartrace. That left only the army commander, Maj. Gen. William Rosecrans, to be invited. Although Rosecrans would soon make Tullahoma his headquarters, he and his staff momentarily rested at Estill Springs, just west of the Elk River. He would definitely receive an invitation to McCook’s party.2

While McCook planned the day’s festivities, the war continued for some soldiers just a few miles from Winchester on the Cumberland Plateau. Although the Federal infantry halted on the plain fronting the mountain wall, Federal cavalrymen probed toward the top of the plateau on two roads. The first, a rough military road, ascended the mountain in the vicinity of Brakefield Point, while the second wound upward from the village of Cowan. Both roads merged at University Place, construction site of an educational institution founded by the Episcopal Church in 1857. Following the laying of the cornerstone on 10 October 1860, little more had been accomplished because of the national crisis. Nevertheless, great plans remained for the University of the South, as it would come to be called. Now Federal horsemen probed toward University Place. On the Brakefield Point road, Col. Edward McCook’s Second Brigade of Brig. Gen. Robert Mitchell’s First Cavalry Division cautiously led the way. Finding the track seriously obstructed by felled trees and rocks placed by the retreating Confederates, McCook’s men abandoned the advance about two miles short of University Place and returned to the plain. On the Cowan Road, one of the primary routes over the Cumberland Plateau, elements of Col. Louis Watkins’s Third Brigade of Mitchell’s division initially found the going easier. Watkins began his ascent at 5:30 A.M. with approximately 1,000 men of the Fifth and Sixth Kentucky Cavalry regiments. Three miles from University Place, he paused to deploy three companies of the Fifth Kentucky under Maj. John Owsley as an advance guard, and then resumed the climb. A mile from the junction with the Brakefield Point road, Owsley’s men suddenly encountered Confederate pickets. When most of their weapons misfired, the pickets fell back on their reserve company and made a brief stand. Following a confused melee, the Confederates hastily withdrew, Owsley’s men gave chase, and the race was on. The time was approximately 8:00 A.M.3

The Confederate pickets proved to be three companies of the Eighth Texas Cavalry regiment, part of Col. Thomas Harrison’s Brigade of Brig. Gen. John Wharton’s Cavalry Division. When the pickets joined their parent unit, Lt. Col. Gustave Cook ordered the Eighth Texas to drive the Federals back. Now it was Major Owsley’s turn to retreat, and the Federal advance guard hastened to rejoin Watkins, suffering six wounded in the process. When Owsley reached safety, Watkins decided to escalate the fight. Holding the Fifth Kentucky in reserve, he sent the Sixth Kentucky forward to charge the Eighth Texas. Overmatched, the Texans grudgingly withdrew toward the University Place road junction. Behind them Maj. Gen. Joseph Wheeler assembled more resources to halt the Federal advance. While Harrison reinforced Cook’s Eighth Texas with Lt. Col. Paul Anderson’s Fourth [Eighth] Tennessee Cavalry regiment, Wheeler called for Col. George Dibrell’s Brigade from Brig. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest’s Cavalry Division to return to University Place. Simultaneously he directed Wharton to form Col. Charles Crews’s Brigade a mile in rear of the units fighting at the road junction. Wheeler’s moves came just in time, because Watkins’s Federals aggressively pushed Harrison’s Confederates beyond the junction. Believing that he had gone far enough, Watkins in midmorning decided to end the action and return to Cowan. At a total cost of three killed and fourteen wounded, Watkins had gained more than twenty prisoners and had learned that the Army of Tennessee’s rear guard was still atop the Cumberland Plateau. Wheeler’s cavalrymen had held their ground at a cost of one killed, six wounded, two missing, and the loss of twenty-five horses. The small fight ended at 9:00 A.M., but Wheeler kept a brigade on the plateau through the afternoon in case the Federals returned. His remaining horsemen descended the mountain, covering the rear of the retreating Confederate infantry.4

At Bridgeport, Gen. Braxton Bragg spent the rainy day orchestrating the withdrawal of his army across the Tennessee River. The army consisted of two infantry corps, Wheeler’s cavalry, and several thousand troops borrowed from Maj. Gen. Simon Buckner’s Department of East Tennessee. The two infantry corps of the army followed separate roads down the mountain, but both roads reached the vicinity of the Tennessee in the valley of Battle Creek. Lt. Gen. Leonidas Polk’s Corps arrived first at a pontoon bridge established with some difficulty on the previous day just north of the mouth of the creek. Although Bragg preferred that Buckner cross first, Polk held the bridge for himself, forcing Buckner’s men to march downstream to Bridgeport. There they would utilize the massive bridge of the Nashville & Chattanooga Railroad to gain the eastern shore. Behind Polk’s command, Lt. Gen. William Hardee’s Corps either had to wait for Polk to complete his crossing or march upstream to another pontoon bridge at Kelly’s Ferry. Following the infantry, Wheeler’s cavalrymen would descend the Cumberland Plateau and cross the river at whatever site was available. Confederate engineers had worked diligently to build the two pontoon bridges and to prepare them for demolition when necessary. In addition, at least one small steamboat plied the river ferrying messages and bringing rations from Bridgeport to the toiling infantry. The railroad from Bridgeport to Chattanooga was also available to facilitate the movement of troops and supplies, and its telegraph line served as a useful communication link to Chattanooga and points beyond. The entire operation was complex, and any delay could be fatal if the Federal Army pushed across the Cumberland Plateau in strength. No commander desired to be caught by a pursuing force with his back to a wide river and his troops in disarray. Braxton Bragg foresaw 4 July 1863 as a day of high anxiety.5

Polk began the day at a bivouac six miles east of University Place and moved early toward the river. At 9:30 A.M. he ordered Maj. Gen. Jones Withers, commanding the leading division, to guard the pontoon bridge at Battle Creek. Half an hour later, Polk learned of Wheeler’s fight at University Place but was assured that the Confederate cavalrymen were holding their own. He then continued his march to and across the bridge with his remaining division, that of Maj. Gen. Benjamin Cheatham. By midafternoon Polk was satisfied that he would not need the bridge much longer. Although rations had arrived by steamboat, he elected to keep his divisions moving. At 2:30 P.M. Polk told Hardee that the bridge would be free for his use at 4:00 P.M. and that Wheeler would cover his rear. To Wheeler, Polk indicated that he should continue to serve as Hardee’s rear guard, that the bridge now belonged to the cavalry, and that Wheeler should dispose of it as he chose. Shortly thereafter, Polk told Capt. Patrick Thomson, one of Bragg’s staff officers, that he was leaving the bridge unguarded and undestroyed. A similar message went to Hardee at 4:30 P.M. Thirty minutes later, the last of Polk’s command marched from the bridge and headed for Shell Mound Station on the railroad to Chattanooga. Withers’s Division camped for the evening at Shell Mound while Cheatham’s men bivouacked along the road between Shell Mound and the now unprotected pontoon bridge. Polk himself camped with Withers. At Shell Mound, he found both stocks of provisions and a working railroad. Seizing the former without authority, he ordered them to be distributed to his hungry men. He also told his artillerymen to dismount their guns and ammunition chests for rail transport to Chattanooga while the carriages and teams continued by road. In neither case did Polk concern himself with any other commands or his superior’s desires.6

Polk’s actions left a trail of mischief in their wake. Bragg had expected Polk to leave a brigade west of the Tennessee River to protect the pontoon bridge and only learned otherwise when Captain Thomson returned to army headquarters at Bridgeport. Bragg’s chief of staff, Brig. Gen. William Mackall, was miffed that his efforts to provide rations to Polk’s men had been disregarded, and he had other uses for the limited railroad equipment than to transport guns seemingly abandoned by Polk at Shell Mound. Hardee decided to find a route across the Tennessee River that would not require him to follow in Polk’s wake. At 7:00 P.M. he notified Polk that he was marching upriver toward Kelly’s Ferry and would not need the Battle Creek span. The detachment from Buckner’s command, having been diverted by Polk to Bridgeport, waited there in hopes of securing space on trains shuttling between that point and Chattanooga. Wheeler’s Cavalry Corps remained scattered, with its leading elements at Bridgeport and a brigade just leaving the top of the mountain by nightfall. At the Battle Creek pontoon bridge, engineers waited for someone to decide the fate of the structure left solely in their charge. Hundreds of weary, hungry, and footsore stragglers lined the roads down the mountain, making their way singly or in small groups toward safety beyond the river. At least one of Hardee’s men thought of the day in historic terms. As Sgt. Robert Bliss later recounted in a letter to his mother, “We celebrated the ‘Glorious Old Fourth’ by marching down Cedar Ridge, through Gizzards Cove to the Tennessee. It was a very hot day and hope it may never be my lot again to attend such another celebration.” The Army of Tennessee had not been defeated in battle, but it had simply been outmaneuvered by the Federals. Nevertheless, the fact that it had been forced to relinquish Middle Tennessee, the selfish behavior of Polk, and the lack of simple coordination among its senior leaders bode ill for the future.7

Entirely unaware of their opponent’s disarray, the officers and men of the Army of the Cumberland welcomed the pause in operations. In George Thomas’s Fourteenth Corps, 4 July was a day of celebration for two reasons, first, the nation’s Independence Day and, second, favorable news from the east, where the Army of the Potomac seemed to be victorious at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. Thus artillery salutes rolled across the plain until they echoed from the Cumberland Plateau throughout the day. The occasion also called forth extravagant oratory from officers and men alike, and regimental bands played patriotic airs, punctuated by lusty cheers from the men in the ranks. Still, the intermittent rain dampened the festivities somewhat and empty stomachs grumbled at the short rations allocated to the Fourteenth Corps by commissary sergeants. In an effort to rectify the situation, many men left the celebrations early to forage on the local economy. A lucky few found civilian items for sale or confiscation, but most had to content themselves with large quantities of ripe blackberries. In Thomas Crittenden’s Twenty-First Corps, which had not yet crossed the Elk, the ration situation was not so dire but the foraging was equally vigorous. Distant from the railroad and telegraph, Crittenden’s men did not hear of the Federal success at Gettysburg, so they celebrated only Independence Day with national salutes. In at least one brigade, the men received an unexpected whiskey ration in honor of the day. In other units, the arrival of a supply train brought not only food but also mail and packages from home. In the army’s rear, Gordon Granger’s Reserve Corps fired the obligatory salutes and searched for ration supplements like their compatriots at the front, but they also spent much of the day holding political gatherings in the occupied areas. In both Shelbyville and Nashville, the troops orchestrated large Unionist meetings among those citizens ready to accept the new political order.8

Like his boisterous troops, Rosecrans celebrated the Army of the Cumberland’s victory on 4 July. He began the day with the Pioneer Brigade, an engineer unit camped near the destroyed Elk River railroad bridge at Estill Springs. There he received a telegram from Secretary of War Edwin Stanton that forecast success over the Army of Northern Virginia in Pennsylvania. Before leaving to join McCook at Winchester, Rosecrans responded to Stanton with good news of his own. In a brief summary of the campaign just concluded, he described the territory gained, compared his own minimal losses to the much greater damage inflicted on the Army of Tennessee, and promised to resume his advance when the weather and his supply situation improved. Had the incessant rain not intervened, Rosecrans argued, he would have brought Bragg to battle and prevented the Confederate army’s escape. Still, the campaign had been a glorious success for Union arms and the army commander could be justly proud of the Army of the Cumberland’s efforts. Having put his victory on the record, Rosecrans ordered the telegraph line to be extended from Estill Springs to McCook’s advanced units at Cowan, then departed with his staff for Winchester at 10:00 A.M. Unable to use the destroyed rail and road bridges at Estill Springs, Rosecrans’s party turned downstream and negotiated a crossing of the turbulent Elk River at Island Ford. From there it was an easy canter to Winchester and McCook’s headquarters, which was reached at noon.9

When Rosecrans reached Winchester, he found McCook’s festivities already under way. Jefferson C. Davis’s First Division of the Twentieth Corps occupied the town with the brigades of Col. Sidney Post, Brig. Gen. William Carlin, and Col. Hans Heg. At noon an artillery battery fired a national salute and several regimental bands played patriotic airs. Undeterred by the persistent rain, celebrating soldiers clogged the streets. In the Eighth Kansas Infantry regiment of Heg’s Brigade, officers toasted the occasion with whiskey, although the men in the ranks were denied that privilege. At 4:00 P.M. McCook hosted a dinner party for sixty officers. Rosecrans and David Stanley of the Cavalry Corps led the guest list, followed by Brig. Gen. James Garfield, the army’s chief of staff, and Brig. Gen. William Carlin. Brigade commanders Post and Heg also attended, as did at least one regimental commander, Col. John Martin of the Eighth Kansas. McCook had hoped to have the dinner in a temporary bower constructed of tree branches, but the rain forced the party indoors. There the dignitaries and their staffs supped, while two regimental bands serenaded the group. A particularly heavy downpour, accompanied by lightning and peals of thunder, washed out the program McCook had planned outside for 6:00 P.M., and the grand party broke up shortly thereafter. While the lesser attendees withdrew to their regimental tents for more whiskey and cigars, Rosecrans, Garfield, and their aides bade farewell to McCook and departed for the rising Elk River on their return to army headquarters at Tullahoma. As they left Winchester, distant echoes of a national salute fired by Philip Sheridan’s division five miles away at Cowan reached their ears.10

Safely crossing the Elk, Rosecrans and his party reached Tullahoma at 11:30 P.M. Despite the incessant rain, the day had been festive. Still, the trip to Winchester had shown Rosecrans what needed to be done before his army could resume its advance. The divisions beyond the Elk were already beginning to suffer because the delivery of rations had been halted by muddy roads and the broken tracks of the Nashville & Chattanooga Railroad. South of Murfreesboro, the Confederates had removed more than two miles of track near Bell Buckle, had damaged the 350-foot Duck River bridge and a trestle near Normandy, and had destroyed the 540-foot Elk River bridge near Estill Springs. All of this damage would have to be repaired before trains could feed the army beyond the Elk and stockpile supplies for the advance to the Tennessee River valley. The man responsible for maintaining the N&C in working order was John Anderson, military superintendent of railroads. Formerly an official of the Louisville & Nashville Railroad, Anderson had been managing the army’s railroad transportation in Kentucky and Tennessee since 1861, serious allegations of inefficiency notwithstanding. Now, with troops reduced to half rations, Anderson needed to rebuild the N&C as quickly as possible. While Rosecrans was at Winchester, Asst. Adj. Gen. Calvin Goddard bombarded Anderson with messages about the necessity for haste. When Rosecrans and Garfield reached army headquarters late that night, they reiterated Goddard’s demands. Rosecrans peremptorily ordered Anderson to superintend the repair work in person. Reinforcing the army commander’s displeasure, Garfield threatened Anderson with removal if the work was not expedited. McCook’s party had been a pleasant interlude, but the problems visible along the railroad quickly brought Rosecrans back to reality. The Tullahoma campaign had been a great success, but the Army of Tennessee waited beyond the Cumberland Plateau. It was time to begin a new campaign.11