5

ROSECRANS

» JULY 1863 «

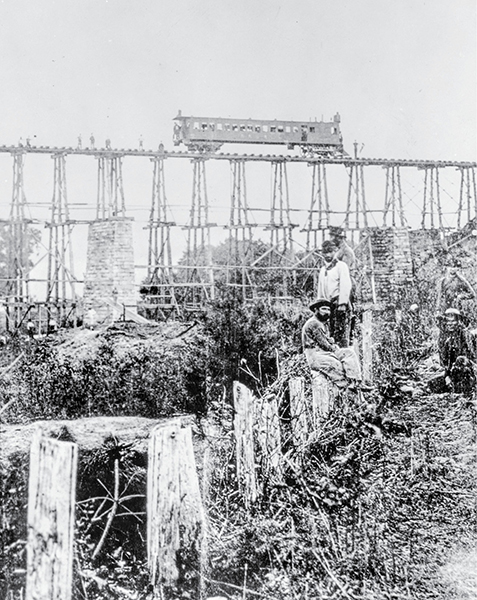

With the Army of the Cumberland momentarily halted between the flood-swollen Elk River and the massive Cumberland Plateau, Rosecrans had little time to savor his success in the Tullahoma campaign. Because the seemingly never-ending rain had turned the region’s primitive roads into deep rivers of mud, there was no hope that his army could be supplied through animal power alone. Yet the Nashville & Chattanooga Railroad was not immediately able to take up the slack because the Confederates had seriously damaged it in many places. Some of the damage, notably the several miles of missing track around Bell Buckle and Wartrace, could be easily handled by John Anderson’s track gangs. Similarly, the damaged Duck River bridge and a long trestle near Normandy could be made serviceable in a short time. The 540-foot Elk River bridge at Estill Springs, however, had been totally destroyed during the Confederate retreat. Until that structure was restored, there could be no forward movement by Rosecrans’s army and the troops would suffer serious hunger pangs as rations diminished. The problem could be alleviated by withdrawing to the north side of the Elk River, but that option was not seriously considered by Rosecrans. No ground gained in the Tullahoma campaign would be relinquished, even temporarily. Thus, there was no choice but to repair the Elk River bridge as expeditiously as possible. John Anderson had already been threatened with removal as railroad superintendent on 4 July if he did not become more energetic and he was badgered anew on the next day. Yet his civilian track workers were not bridge builders, so military assets would have to be mobilized for the larger projects. Those assets included William Innes’s First Michigan Engineers and Mechanics regiment, consisting primarily of Michigan woodsmen, and the larger Pioneer Brigade of St. Clair Morton.1

The location of the army’s engineers favored the Pioneer Brigade reconstructing the Elk River railroad bridge. Working in the army’s rear, the First Michigan regiment on 5 July moved to Tullahoma, having completed repairs to the Duck River bridge and the Normandy trestle on the previous day. Morton’s Pioneer Brigade was already at the Elk River, although its energies were dissipated among several diverse projects. Some soldiers labored to return a grist mill to operation, while others began work on several nearby road bridges. At the site of the railroad bridge, some men began to remove bridge wreckage while others completed a temporary foot bridge across the river. The Elk itself, however, continued to rise in depth and velocity because of the continuing rainfall. On 6 July the rampaging river demolished the Pioneer Brigade’s footbridge, stopping all work at the site. Back at Tullahoma, the First Michigan rested and repaired its equipment and tools. Also at Tullahoma, Rosecrans became increasingly impatient to see measurable progress on the railroad reconstruction effort. During the day he dispatched several telegrams to John Anderson, demanding detailed information and berating Anderson for the slowness of his operations. He also forwarded to Anderson a charge by the Nashville commissary of subsistence that a shortage of boxcars was hindering the army’s resupply efforts. In like vein, the army commander telegraphed Morton several times, seeking progress reports and demanding a completion date. Exasperated when no answer was forthcoming, Rosecrans telegraphed the McCallum Bridge Company in Cincinnati for an estimate of how long it would take for the company to fabricate a bridge over the Elk. He also rebuked Morton for his men’s propensity to steal from divisional wagon trains they helped ford the Elk. At the bridge site, the Pioneer Brigade exhausted its supply of army bread, causing one soldier to confide to his diary: “Began to feel very weak for the want of bread to eat.”2

The Pioneer Brigade was not alone in lacking rations. That condition prevailed throughout the army’s camps, especially those of the Fourteenth and Twentieth Corps around Decherd, Winchester, and Cowan. Not only was the railroad broken north of Tullahoma, but also the road bridges over the Elk were destroyed, and the roads everywhere were quagmires of mud. Writing on 5 July, Capt. Everett Abbott described the situation succinctly: “We have been almost out of provisions several days. … Foragers have taken everything eatable from the country. Many people left destitute—some say they are almost starving. Such are calamities of war.” Two days later, he reported an even bleaker story: “For miles everything eatable has been taken. A desolate God forsaken country. Soldiers everywhere searching for something to eat. Don’t know how citizens will avoid starvation. Soldiers must be fed.” In Stanley’s brigade, Pvt. William Christian wrote on 6 July, “The boys are almost starved. … We all know what it is to be hungry.” Christian’s sentiments were mirrored on 7 July by Cpl. William Miller: “We have no bread of any kind tonight but one of our boys got some middlings or shorts and we made cakes out of it and a man had to have a stomach like a corn sheller to dijest it.” With the daily ration reduced to one piece of hardtack in many Fourteenth and Twentieth Corps regiments, no civilian cows, sheep, hogs, turkeys, chickens, potatoes, or other vegetables were safe from famished soldiers. In Van Cleve’s division of the Twenty-First Corps at McMinnville, friendly mountaineers offered produce for sale, but elsewhere the food often was confiscated after bitter confrontation. The situation was eased somewhat by the availability of ripe wild berries of several types. Even the berries, however, were not always enough to remove the general discontent, as Lt. Chesley Mosman reported: “Got so hungry I didn’t know what to do. … Went a berrying for spite.”3

The men in the ranks reacted to the lack of rations according to each soldier’s temperament. Some, like Lt. Jesse Connelly accepted their fate with equanimity: “Our rations are short, but we can live, and while we have enough to satisfy the cravings of hunger should be content, as I think we are.” Others consoled themselves with the knowledge that their Confederate counterparts had much less to eat than did the Federals, yet maintained their fighting spirit, so the temporary dearth of army rations could be easily borne. Such reactions were atypical, with many soldiers instead expressing their frustrations and hunger pangs through cursing, grumbling, and finding fault with the chain of command. In their encounters with civilians, particularly those still loyal to the Confederacy, foragers went about their work of confiscation without much gentility. Even other units were considered fair game for expropriation, as Pvt. John Love demonstrated while accompanying a wagon train struggling through the mud to a depot in the rear. Coming upon a loaded train whose personnel had unloaded a wagon to free it, Love and his compatriots stole three boxes of hardtack and a side of meat for their own use. Cpl. Alanson Ryman proudly wrote his wife about his prowess in keeping himself fed through various subterfuges. An extremely shrewd and frugal soldier, Ryman assured his wife that “you need have no fears of my starving while I stay in the army.” With rations so short, few were inclined to share them with civilians. When First Sgt. Axel Reed heard that Confederate civilians and deserters were receiving Federal rations, he resolved to take action. Reed and others wrote a blistering letter to the Nashville Union newspaper, exposing the practice and thereby embarrassing John Brannan, his new division commander. Brannan ordered Reed placed under arrest and removed from duty indefinitely. The longer the railroad remained closed, lapses in discipline and complaints such as Reed’s would continue to spread across the army.4

In the midst of his unsuccessful efforts to restore the Nashville & Chattanooga Railroad to working condition, Rosecrans received a telegram on 7 July from Secretary of War Stanton: “We have just received official information that Vicksburg surrendered to General Grant on the 4th of July. Lee’s army overthrown; Grant victorious. You and your noble army now have the chance to give the finishing blow to the rebellion. Will you neglect the chance?” Stung by Washington’s apparent lack of understanding of what the Army of the Cumberland had just accomplished, Rosecrans testily replied: “You do not appear to observe the fact that this noble army has driven the rebels from Middle Tennessee, of which my dispatches advised you. I beg in behalf of this army that the War Department may not overlook so great an event because it is not written in letters of blood.” In pointing out that he had won a great victory without suffering the losses incurred by Grant and Meade, Rosecrans spoke no more than the truth. A disinterested observer might also concede the point that casualties were not necessarily the best means by which to judge a commander’s success. Nevertheless, prudence dictated that Stanton’s implied criticism be noted by silence. Rosecrans, however, continued the habit of plain speaking to his superiors that had already caused him trouble in the past. Passing along Stanton’s news of the Vicksburg and Gettysburg victories to Governor Andrew Johnson of Tennessee, Rosecrans made his point in slightly gentler terms: “We may thank God and congratulate ourselves that the ides of July were auspicious for freedom, and for our own army that we have accomplished a great work without bloodshed and were prevented only by the unprecedented rains from giving the coup de grace to Bragg’s army.” In a brief telegram to his wife, he boasted, “Our losses are but slight not over 600 killed & wounded. Am well. Occupy Bragg’s Head Quarters.” In honor of all of the Federal victories, Rosecrans ordered a round of artillery salutes to be fired at sunrise on the next day.5

Peeved but undistracted by his telegraphic exchange with Stanton, Rosecrans continued to press both John Anderson and St. Clair Morton to accelerate their work on the railroad. On 7 July he bombarded Anderson with orders and complaints: send forward materials to repair the telegraph line, provide handcars for movement on the line, stockpile duplicates for all bridges. Most telling of all, Rosecrans again demanded that more boxcars be found to move rations from Nashville to the army when the railroad was again operating. To Morton, it was more of the same: what are the specifications for the Elk River bridge, when will it be finished, how many cars will it take to bring the pontoon train forward? Although Rosecrans expected that the railroad would be open to the Elk River bridge by 8 July, it was not. Indeed, the telegraph operator at Wartrace reported that two trains had arrived at that point but could go no farther because of weeds clogging the track. For a commander as mercurial as Rosecrans, such excuses were the last straw. Heretofore, Rosecrans had communicated with Anderson solely via aides; now he personally demanded that Anderson produce the railroad’s books and accounts for inspection. The army commander closed this chilling telegram with one word: “Push.” Anderson responded by once again claiming that he would have one passenger train and four freight trains running soon, certainly by 10 July. That response did not satisfy Rosecrans. With the army on the verge of starvation, many vigorously foraging troops were committing outrages upon the local population. The reports were so numerous that Rosecrans was forced to have Garfield on 8 July admonish his corps commanders to enforce strictly the regulations against unauthorized foraging and severely punish offenders. Clearly, the railroad had to be completed to the Elk River to facilitate wagon hauls to the units on the south side—and it had to be done soon.6

Completion of the railroad to the Elk River was only a first step toward sustaining an advance beyond the Cumberland Plateau. The more difficult task was to rebuild the Elk River railroad bridge. Morton’s Pioneer Brigade was doing little better than John Anderson’s track gangs in completing the structure. Well aware of the rivalry between the Pioneer Brigade and the First Michigan Engineers and Mechanics, Rosecrans resolved to use it to expedite the bridge-building. Coincidentally, Innes’s regiment rested at Tullahoma without assignment. Seeing his opportunity, on 8 July Innes sent Lt. Col. Kinsman Hunton to survey the bridge site and Morton’s work. The next day, Rosecrans called Innes and Hunton to headquarters to discuss the Elk River bridge. Rosecrans presented Innes with Morton’s estimate that he could complete the Elk River bridge in from six to eight weeks but would require assignment of the First Michigan to assist the Pioneer Brigade. In response, Innes and Hunton offered to build the bridge in seven days if the Pioneer Brigade was removed from the project. That sort of confidence was just what Rosecrans was seeking, and he assigned the bridge reconstruction to the First Michigan on the spot. To spur them on, he added an additional incentive. Some months earlier, Rosecrans had created new flags for each of his army corps and had included one for the engineers. Since that time, the flag had been claimed by Morton for the Pioneer Brigade. If Innes and Hunton made good on their promise to complete the bridge in seven days, Rosecrans promised, he would award the engineer flag to Innes’s regiment. Innes and Hunton accepted Rosecrans’s challenge, and the staff informed Morton that the Pioneer Brigade no longer would work on the bridge. Instead, the Pioneer Brigade was to devote its time to repairing wagon roads and cutting wood for locomotive fuel and railroad ties. Other messages instructed Morton to build platforms at Estill Springs for the imminent arrival of supplies, and formally assigned Innes to take charge of all railroad repairs.7

Just after midnight on 9 July, soldiers guarding the Duck River bridge at Normandy witnessed the passing of the first southbound train. At 2:15 A.M. Garfield noted the train’s arrival at Tullahoma. After unloading part of its cargo, the train proceeded to Estill Springs to discharge the remainder. A second train passed Normandy at 6:00 A.M. headed to the same destinations. By the end of the day a total of forty-one boxcars loaded with rations had arrived at Tullahoma. There a branch left the main line of the railroad, passed through the town of Manchester, and continued thirty-five miles northeast to McMinnville, at the foot of the Cumberland Plateau. If that line could be restored to working order, it could sustain the Twenty-First Corps with food and forage. Thus Rosecrans on 9 July instructed Anderson to put the branch into operation “at once,” with a capacity of sixty to seventy tons per day. This line, officially the McMinnville & Manchester Railroad, had been leased to the Nashville & Chattanooga before the war and had suffered major damage from Federal cavalry raids in the spring. Its numerous trestles and a 225-foot bridge over Hickory Creek had been repaired by the Confederates but its general condition was poor, especially beyond Manchester. It would take the installation of at least 15,000 new railroad ties before the line could be opened as far as McMinnville, where Rosecrans planned to base a division of the Twenty-First Corps. Rosecrans also sought one of the three inspection cars purchased earlier by the government. Having the outward appearance of a passenger coach, these cars were propelled by a small steam engine in one end, and were known as “steam dummies.” Built for the Pittsburgh, Fort Wayne, & Chicago Railroad in 1860, the cars were of iron construction and longer than normal coaches. Their carrying capacity of ninety-four passengers and three tons of baggage made them ideal for track inspection duty or general officer transportation. Now Rosecrans wanted one for his personal use.8

The completion of the railroad to Estill Springs and the reconstruction of a nearby wagon bridge meant that the units concentrated around Decherd and Winchester now could be resupplied by simply sending their teamsters to Estill Springs. Nevertheless, until a sufficient stockpile of rations was accumulated, Rosecrans’s three infantry corps would have to mark time in their camps south of the Elk River. Since they could not, however, all be in one place, they were scattered on the plain facing the forbidding Cumberland Plateau. The bulk of the Army of the Cumberland was clustered around the railroad. The four divisions of Thomas’s Fourteenth Corps lay either at the village of Decherd or along roads leading toward Manchester and Hillsboro. All of Thomas’s units were concentrated in that area except for Wilder’s mounted infantry brigade, camped at Rowesville on the Duck River near Normandy. McCook’s Twentieth Corps also lay along the railroad. Davis’s First Division occupied the town of Winchester on the Winchester & Alabama Railroad, which joined the N&C two miles to the north at Decherd; Johnson’s Second Division garrisoned Tullahoma, site of Rosecrans’s headquarters; Sheridan’s Third Division was dispersed around Cowan, just short of the railroad tunnel. To the north, Crittenden’s Twenty-First Corps held Manchester with Palmer’s Second Division; two brigades of Wood’s First Division were at Hillsboro, the third being at Pelham; and Van Cleve’s Third Division was farthest north, at McMinnville. The reopening of the railroad to McMinnville, which occurred on 11 July, meant that all of Rosecrans’s infantry was within reach of a working railroad line. Starvation no longer threatened the Army of the Cumberland. On 10 July Rosecrans felt secure enough to call forward the remainder of his headquarters staff, with their voluminous files and printing press. On that day, too, six companies of the First Michigan Engineers and Mechanics moved their camp to the Elk River Bridge site.9

An Army of the Cumberland steam dummy in 1864. (Library of Congress)

With his logistical situation improving, Rosecrans turned his attention to expanding his operational area. On 7 July he had ordered Stanley’s Cavalry Corps to prepare an expedition to sweep the territory fifty miles southwest of Winchester and beyond the army’s right flank. Rosecrans on 10 July clearly established Stanley’s objectives. First, Stanley was to examine the territory west of Winchester to Pulaski, Tennessee, then southward to Huntsville and Athens, Alabama, giving special attention to railroads. Second, Stanley was to impress upon the inhabitants that the Federal army intended to maintain control of the area, unlike previous visits. Third, Stanley was to rid the countryside of guerrillas and bushwhackers who were harassing foraging parties. Fourth, Rosecrans wanted Stanley to bring to Winchester as many able-bodied male slaves as he could. Finally, Stanley was to gather all horses and mules he encountered. Rosecrans believed that one division would be sufficient for the mission, but he entrusted the details of the expedition to Stanley. In their camps around Salem, a few miles south of Winchester, Stanley’s two divisions commenced their preparations. At the same time, Rosecrans found a role for Wilder’s mounted infantry brigade. Nominally subordinate to Reynolds’s Fourth Division, Fourteenth Corps, Wilder had already begun to establish his independence. On the same day that he defined Stanley’s mission, Rosecrans gave similar orders to Wilder, who was to sweep the territory in Stanley’s rear westward to the vicinity of Columbia. Wilder, too, was to confiscate all the able-bodied male slaves, horses, and mules he could find. Aware of the brigade’s proclivities, Rosecrans enjoined Wilder “to prevent pillage and marauding.” Perhaps coincidentally, on the same day that he received his instructions Wilder presented to the army commander a thoroughbred horse he had captured earlier. The gift prompted a fulsome response from Rosecrans, who later told his wife it was “the finest horse I ever owned.”10

As Stanley and Wilder would be exploring the territory on the army’s right, Rosecrans also desired to know what was happening beyond the Cumberland Plateau. On 7 July Sheridan reported the destruction of the Bridgeport bridge and recommended action to preserve the railroad for Federal use. In response, Rosecrans on 8 July authorized McCook to reconnoiter beyond the plateau as far as Bridgeport. In turn, McCook ordered Sheridan to lead the reconnaissance from Cowan. On 9 July Rosecrans repeated his directive more explicitly. That day Sheridan sent Bradley’s Third Brigade to the top of the Cumberland Plateau at University Place and accompanied them himself. On 10 July Sheridan and Bradley probed gingerly forward to a place known locally as Dorn’s Burnt Stand, where a rough road led down into Sweeden’s Cove and the valley of the Tennessee River. During the afternoon, Sheridan led Col. Daniel Ray’s Second Tennessee Cavalry regiment into the cove and nearly to Battle Creek before returning to the top of the mountain. On the next day Sheridan sent Ray’s horsemen back into the valley with orders to probe as far as Bridgeport and Stevenson before returning along the railroad to rejoin Bradley’s infantry. At the same time, he instructed Col. Bernhard Laibold, commanding his Second Brigade at Cowan, to send two regiments through the tunnel to Tantalon Station and eight miles beyond to Anderson Station. In response, the Second and Fifteenth Missouri Infantry regiments stumbled through the dark tunnel to Tantalon. On 12 July they continued to Anderson Station and discovered that while three small bridges between Tantalon and the tunnel were destroyed, four more between Tantalon and Stevenson remained intact. Sheridan also reported that a Confederate brigade guarded the river across from Bridgeport and that a steamboat was operating on the river. Sheridan returned to Cowan by handcar on 12 July. Laibold’s regiments followed two days later, while Bradley’s brigade withdrew to University Place and camped there on the same day.11

At Tullahoma, the pause in operations allowed Rosecrans to enjoy a brief respite. On 12 July he telegraphed his wife, Anna, in Yellow Springs, Ohio, to join him in Nashville two days later. He then took a train to Estill Springs to inspect the work of the First Michigan Engineers and Mechanics. Innes’s regiment had reached the bridge on the previous day, and Rosecrans’s arrival found them hard at work shaping the heavy timbers needed to raise the bridge. Using horses provided by Innes, the general and some staff officers toured the site. To the delight of the Michiganders, Rosecrans expressed great pleasure at the speed with which the men worked. On the following day, 13 July, he took the steam dummy up the McMinnville branch line. Stopping first at Manchester, where he was joined by Crittenden and Palmer, the party continued to McMinnville to meet Van Cleve. Writing to his wife after his return to Tullahoma, Rosecrans described McMinnville as a pleasant place: “It has many substantial brick houses and contains quite a large number of union people. As we rode up one of the streets two young ladies stood opposite us and one of them presented me a magnificent boquet.” Expecting to hear from Anna upon his return, he was disappointed to find no response. When he finally received Anna’s reply the next morning, he discovered that his original message had been delayed a full day. At 11:25 A.M. Rosecrans promptly renewed his invitation: “Come, advise me.” Using the full power of his position, he imperiously instructed telegraphers as far north as Louisville to prevent another such delay in service. Before leaving for Nashville on the afternoon of 14 July, Rosecrans immersed himself in administrative trivia and welcoming two new officers to his staff, First Lieutenants Neil Dennison and Henry Cist. At last, Rosecrans boarded the train for Nashville, with Garfield, Goddard, Bond, Drouillard, Thompson, and perhaps others. The junior staff remained at Tullahoma to maintain the headquarters in their commander’s absence.12

For the next several days, Rosecrans made a series of inspection tours in the Nashville area. Leaving his quarters at the St. Cloud Hotel, on 15 July he traveled south to Franklin to view its fortifications. On the next day, Thursday, he visited the Nashville waterfront and toured the navy gunboats St. Clair and Brilliant. Both vessels and forts fired salutes in Rosecrans’s honor. He inspected hospitals in the city on Friday, 17 July, and took part in a large review of Reserve Corps troops with Granger. In the evenings, Rosecrans followed developments at the front, such as progress on the Elk River bridge, Sheridan’s activities around University Place, Stanley’s cavalry expedition, and a myriad of administrative matters. Gradually, however, the flow of messages between Nashville and Tullahoma diminished. Although Rosecrans was in no hurry to return to Tullahoma, others in his entourage were more eager to get on with the war. On 17 July, Garfield wrote to his wife, Lucretia: “We have a great work on hands to visit all the hospitals, forts, troops, and quartermaster and commissary departments in this place. We shall also make out the official report of our late campaign before we leave this place which will be probably three days hence.” When he was not away from the St. Cloud, Rosecrans spent many hours entertaining visitors. One such visitor on 17 July, Col. John Sanderson, attempted to speak with Rosecrans but was unable to do so: “After Gen Rosecrans’ return from the review I called to pay my respects to him at his rooms. I found him surrounded by his staff, & a crowd of visitors, each one of whom had I suppose business of some kind with him. I consequently avoided occupying his time.” Sanderson spoke instead to Garfield, who told him to call again later in the evening. Sanderson did so, but just as he was about to be ushered into Rosecrans’s suite, Anna Rosecrans and two of the general’s children arrived from Louisville. Flustered, Sanderson withdrew, promising to seek an audience with the army commander in the future.13

Oy 18 July, upon returning from another round of hospital visits, Rosecrans learned that the Elk River bridge had been completed by the First Michigan Engineers and Mechanics. True to their word, Innes and Hunton had built the 540-foot structure in one week. There had been a brief delay three days earlier when Innes informed the staff at Tullahoma that a request to Morton for two-inch planking had gone unanswered. The staff forwarded the request to Garfield, who responded that the planking would be sent from Nashville. This inquiry elicited the information that Morton was ill and had departed, still smarting from his defeat at the hands of the Michiganders. The bridge itself was completed in midafternoon, 18 July, when the locomotive Huntsville pulled the construction train across the structure while a regimental band played “Hail Columbia.” Innes then took the train to Decherd and Cowan, through the tunnel, and all the way to Tantalon Station. There, he found that a detachment had repaired the last broken trestle on the railroad, which was now open all the way to Bridgeport. Notifying Rosecrans of the glorious news before he headed for Tantalon, Innes upon his return to Elk River received the army commander’s heartfelt thanks through telegrams from Garfield in Nashville and the staff at Tullahoma. Also gratifying to Rosecrans was a report on Wilder’s expedition to Columbia. On 12 July Wilder had sent the Seventeenth Indiana and 123rd Illinois Mounted Infantry regiments on the sweep, led by Col. James Monroe. Although unwell and facing business problems at home, Monroe aggressively led his two regiments on a 160-mile rampage through the towns of Lewisburg, Columbia, Centerville, Mount Pleasant, Mooresville, and Petersburg. Finding only a handful of convalescent and furloughed Confederates, Monroe added them to his haul of slaves and draft animals. The expedition returned to its base at Rowesville near Normandy on 18 July with fifty prisoners, 250 slaves, and 700 horses and mules, having lost only Pvt. Andrew Stewart killed.14

Not all the news reaching Rosecrans in Nashville was positive. Most troubling was a report from “scouts” at Tantalon that 3,000 Confederate cavalry had crossed the river on their way to burn the Crow Creek railroad bridges. That news generated a flurry of queries to both McCook and Sheridan. Although the report would prove to be incorrect, it illustrated the difficulty both armies encountered in learning about the other when separated by several mountains and a wide river. Apparently the source of the report was Col. Daniel Ray, who on 17 July informed Sheridan: “It is reported that 300 Rebel cav. crossed the river and went into Sweden’s Cove two days ago. … P.S. I learn from apparently reliable source that Gunter a guerrilla Capt. is on this side of the river with a squad of men and says he intends to burn all the bridges between Anderson Station and Bridgeport.” On the next day Ray reported that a woman named Schwartz claimed that 500 Confederates were near the headwaters of Little Crow Creek, on a mission to burn railroad bridges. As the distance from Tantalon increased, so did the number and aggressiveness of the Confederate raiders. By the time the story reached Nashville the raiders had grown tenfold, precipitating Rosecrans’s hasty calls for a response. The problem was compounded by the participation of Mrs. Schwartz. According to Ray, she carried passes permitting both entry and exit through Federal lines, using two names different from her own. Having encountered her before, McCook told Sheridan to “make her go and show where the rebels are and if she is lying hang her.” That outcome was forestalled by another telegram from Rosecrans: “Colonel Truesdale says Schwartz is well known to many persons in the Army. She has been in the Secret Service of the Army I am informed two years. I have no doubt about her loyalty and think her safe to trust.” In the end, no Confederates were found and Mrs. Schwartz remained at large, although Sheridan threatened to “baptize” her in Crow Creek.15

In the absence of any formal system of analyzing the scraps of information that came to hand, people like the elusive Mrs. Schwartz were able to wreak havoc on operations, no matter how benign their intentions. Before crossing the mountains, the Army of the Cumberland received information on Confederate activities from a variety of sources. First were observations by Federal units. Second, current Confederate newspapers occasionally reached the Federals. Third, Confederate deserters often provided information, although their testimony had to be weighed carefully. Fourth, local civilians offered similar bits of news, but again much of it was suspect. The population of East Tennessee was seriously divided over the war, with many citizens opposed to the Confederacy and willing to risk all they had to support the Union cause. Finally, secret agents like Mrs. Schwartz prowled throughout the operational area. Like all the others, they reported what they saw and heard, for what it was worth. All of the various pieces of information were duly recorded by Capt. David Swaim in a ledger titled “Summaries of the News Reaching Headquarters of General W. S. Rosecrans, 1863–64,” but without any overt attempt to rank them in order of importance, truthfulness, or precise chronology. William Truesdail ran his personal spy network, while Captains Swaim and Farrar of Rosecrans’s staff also dispatched agents. Provost Marshal William Wiles attempted to generate a current order of battle for Bragg’s command from prisoner interrogations. Occasionally Rosecrans would receive information from Halleck in Washington, more rarely from Burnside on his left, and almost never from Grant on his right. All of this information was analyzed solely by Rosecrans, and he was supremely confident that he was capable of doing so. Unless he chose to involve Garfield, his estimates of Bragg’s location, strength, and intentions were his own. Thus the deficiencies in the system exposed by the phantom Crow Creek bridge burners remained unchanged.16

“Summaries of the News” shows a wide variety of sources providing information to Rosecrans in mid-July. At least sixteen Confederate deserters provided statements. While a few provided useful order-of-battle data, most spoke only of the general situation around Chattanooga. Almost universally, they claimed rations were low, Bragg was unpopular, Chattanooga was unfortified, and the city would soon be abandoned. Next in quantity was the information provided by fourteen civilians, many of whom were disaffected East Tennesseans. These civilians moved freely in and out of Chattanooga, crossing the pontoon bridges without challenge. Observing troop movements on the railroads, they ascribed them to a decision to divide Bragg’s army between East Tennessee and Mississippi. What they were actually seeing was simply the return of Buckner’s command to Knoxville, the movement of Johnson’s Brigade to Loudon, and the transfer of Hardee’s Corps to Tyner’s Station. The most detailed civilian reports came from an Irish foundry worker and two Nashville & Chattanooga brakemen, who provided specific and mostly correct information on affairs in Chattanooga, troop locations, and railroad conditions. Five reports from “scouts” added nothing to the civilian accounts, most describing nonexistent Confederate cavalry movements in the Sequatchie Valley. Three informants characterized as “agents” were associated with William Truesdail. One was the notorious Mrs. Schwartz, who reported on Confederate stragglers around Columbia but earned no entry for her bogus Crow Creek report. Another agent made it all the way to Atlanta and back via Huntsville with general information on the Atlanta munitions industry and road conditions. The third, who came from Chattanooga, provided good information on Confederate troop dispositions and Bragg’s intention to make a stand there. Telegrams from Washington and Louisville and a captured edition of the Chattanooga Daily Rebel added nothing useful, nor did most statements forwarded by field commanders.17

The one field commander closest to the Confederates, Sheridan, was also the most active. Although Mrs. Schwartz’s reports proved to be in error, there was no denying the fact that the Nashville & Chattanooga Railroad remained vulnerable beyond Cowan. It was also equally clear that the railroad was absolutely vital to sustain an advance by the Army of the Cumberland. Maintaining the security of the railroad thus became an instant priority when it was discovered that it was relatively undamaged. Sheridan had pushed Bradley’s Third Brigade to the top of the Cumberland Plateau at University Place on 9 July but it had only operated on the plateau, not in the Crow Creek valley where the railroad exited the tunnel. To cover that area, Sheridan sent two-regiment contingents through the tunnel to Tantalon and Anderson Stations on three-day rotations, beginning on 11 July, while the Second Tennessee Cavalry (Union) regiment patrolled to the river. The infantry had to return to Cowan so quickly because the men could only carry rations for three days at a time and the unfinished Elk River bridge prevented the accumulation of supplies at Cowan. Thus Lytle’s First and Laibold’s Second Brigades shared the onerous duty of protecting the tracks. Because the road over the plateau was virtually impassable, the regiments had to make the disagreeable trip through the long, dark railroad tunnel and return the same way. The Second Brigade’s Seventy-Third Illinois Infantry regiment enlivened its passage by having its band play “Yankee Doodle” as the regiment stumbled through the tunnel. The usual practice was for one regiment to be stationed at Tantalon and the other at Anderson. While keeping both the railroad and the working parties of the First Michigan Engineers and Mechanics secure, the forward position at Anderson Station still was eleven miles from Stevenson and twenty-two miles from the Tennessee River bridge at Bridgeport.18

Although the threat to the Crow Creek trestles proved to be groundless on 18 July, Sheridan decided, with McCook’s approval, to move beyond the Cumberland Plateau in strength. Accordingly, on 19 July he ordered Laibold’s entire brigade to march to Stevenson. At the same time, he directed Bradley to make another reconnaissance into the upper end of Sweeden’s Cove. Fortuitously, completion of the Elk River bridge on the previous day brought Innes’s construction train within Sheridan’s orbit. Commandeering the locomotive and flatcar for the day, Sheridan took twenty soldiers down the line, far ahead of Laibold’s toiling infantry. The party boldly passed through Stevenson and continued to the Widow’s Creek trestle three miles from Bridgeport. Although the trestle was intact, Sheridan prudently directed the party to return to Anderson Station. Unseen by Sheridan, Confederate scouts reported his presence to Patton Anderson at Taylor’s Store, a mile east of the river. Having relieved Jackson’s Brigade on the evening of 13 July, Anderson had stationed one regiment at Shell Mound and posted the bulk of his command between Taylor’s Store and the Bridgeport bridge, with his pickets on Long Island. Keenly interested in the Federal activity in the Crow Creek valley, Anderson regularly sent scouts beyond the river. He also gained control of Capt. Patrick Rice’s Company G, Third Confederate Cavalry regiment. Rice had been raised just across the river in Tennessee and knew both the land and its inhabitants well. On the night of 18 July, when the Federals were chasing phantoms along Crow Creek, Rice was across the Tennessee with a small party, burning the highway bridge over the Sequatchie River near Jasper. Anderson’s aggressive posture meant that Sheridan’s noisy railroad reconnaissance was reported to Chattanooga within forty-eight hours. Learning that the Widow’s Creek trestle was still intact, Anderson sent a party across the river on 20 July to destroy it. The next time the Federals appeared, they would find the railroad broken at Widow’s Creek.19

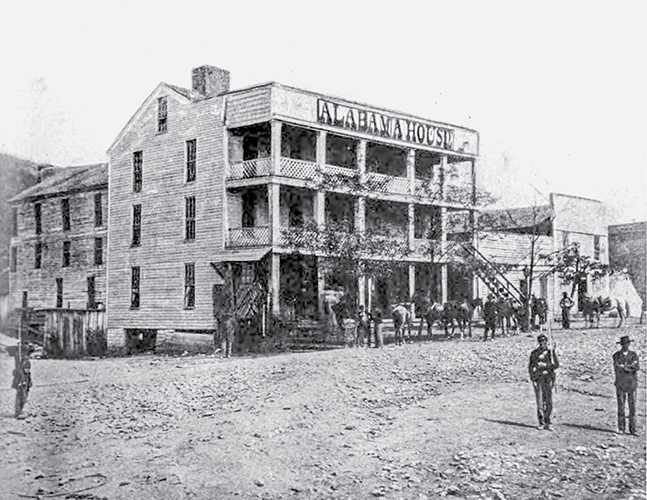

Sheridan’s advance developed slowly in the summer heat. Laibold’s four regiments halted only a few miles south of Anderson Station on 19 July. At the same time, Bradley cautiously sent half of his brigade across the plateau once more to Dorn’s Burnt Stand, where they could look into the upper reaches of Sweeden’s Cove. On the next day, Bradley’s regiments returned to University Place, having seen and heard nothing of interest. Wherever they might be, regular Confederate units did not inhabit Sweeden’s Cove. Meanwhile, Laibold stationed a regiment at Anderson, posted another at a railroad bridge over Crow Creek, and led his remaining two regiments into Stevenson itself. Named for Vernon Stevenson, president of the Nashville & Chattanooga Railroad and now a Confederate quartermaster major in Atlanta, Stevenson had once been an important railroad junction. In peacetime, it was the place where the Memphis & Charleston Railroad met the Nashville & Chattanooga Railroad, its trains continuing to Chattanooga on trackage rights negotiated in 1858. Originally part of the Confederacy’s best east-west route, but severed in multiple places during the campaigns of 1862, the M&C was now little more than two streaks of rust coloring the jungle of weeds obscuring the track. Stevenson itself was only a few dwellings and a one-street business district anchored by two railroad stations and a large frame hotel, grandly titled the Alabama House. Federal troops had occupied Stevenson for several months in 1862 during Buell’s dilatory advance on Chattanooga. To protect the junction, Federal soldiers had constructed a small enclosed earthwork named Fort Harker overlooking the stations and a wooden stockade nearer the village. By the time Laibold entered Stevenson, it contained only six families, all Unionist. According to Sgt. William Newlin, the village was “very shabby and unattractive in appearance.” The defensive works, however, were in fine shape, and were quickly occupied.20

The Alabama House, Stevenson, Alabama. (Miller, Photographic History)

With the railroad now secure as far as Stevenson and supplies only beginning to accumulate, Rosecrans saw no need to hasten back to the front. Thus he remained in Nashville with his family. Two of his corps commanders also took the opportunity to have their wives join them, although in each case that opportunity was marred by family tragedy. Thomas Crittenden was notified by Rosecrans’s staff on 16 July that his wife, Catherine, had reached Nashville and would join him at Manchester on the next day. Unfortunately, Crittenden’s father, Senator John Crittenden, was near death in Kentucky and on 21 July Crittenden received permission to join the vigil at the patriarch’s home. He and his wife departed immediately, leaving Palmer in temporary command of his corps. Fearing he would be too late, Crittenden arrived in Frankfort on 24 July. Senator Crittenden died two days later, with his son at his bedside. Crittenden would remain in Kentucky for several weeks. On 19 July Rosecrans invited Kate McCook, wife of Alexander McCook, to join her husband at Winchester. Married for only six months, McCook was trying to change his image, according to regimental commander Caleb Carlton, who wrote, “It is amusing to see McCook try to be good, he used to be one of the roughest and hardest cases in the army, his wife has made him pious and he has service in his quarters and has stopped drinking, and is doing his best to stop swearing.” On the day of Rosecrans’s invitation, McCook’s father, Maj. Daniel McCook Sr., was participating as an impetuous volunteer during the chase of Morgan’s Confederate raiders in Ohio. The elder McCook, sixty-five, was mortally wounded that day at Buffington Island and died two days later. Alex McCook’s original plans were to meet Kate at Nashville on 22 July and escort her to Winchester, but news of his father’s death caused him to continue northward to Cincinnati for his father’s burial on 25 July. In McCook’s absence, Sheridan assumed command of the Twentieth Corps and at McCook’s suggestion transferred his headquarters from Cowan to Winchester.21

In the midst of the Crittenden and McCook tragedies, the headquarters of the Army of the Cumberland moved from Tullahoma to Winchester on 21 July. With the primary staff in Nashville, Maj. William McMichael of the adjutant general’s section and Capt. Robert Thoms, a junior aide-de-camp, coordinated the details of the movement. McMichael selected the Mary Sharp College, a female school closed since 1861, as the army’s headquarters, and located officers’ quarters nearby. Anticipating that Rosecrans would soon arrive with his family, the staff selected a suitable private residence for him as well. McMichael also procured horses for Rosecrans and Garfield. In Rosecrans’s absence, much official business that needed his attention had accumulated, but the general made no effort to leave Nashville. As an enticement, Thoms on 22 July wrote to Maj. Frank Bond, Rosecrans’s senior aide: “Tell General he will be much more comfortable here than is possible at Nashville.” Thoms was most likely correct, as the newest member of the staff, 1st Lt. Henry Cist, informed his mother in a letter on the same day. Describing Winchester as a “truly lovely place,” Cist continued, “We found only thirteen pianos in the house. They are fast getting out of tune with the banging that is going on them. But pianos in the South are rarely in tune. We have some two or three members of the staff who are very fine performers and we have been enjoying the music as much as possible. This place is one of the most bitter of all Secessia. There are a number of citizens here and a very large proportion of them are pretty girls at least to us who have not seen any for so long.” Cist’s opinion of Winchester was echoed by Pvt. Allen Frankenberry, a member of Rosecrans’s escort. Frankenberry recorded in his diary that Winchester was “a most beautiful town, full of pretty houses, gardens, trees, flowers, and girls, but all south.”22

On the day that army headquarters opened for business at Winchester, David Stanley arrived with news of his expedition to Alabama. Before his departure for Nashville, Rosecrans had sent Stanley’s Cavalry Corps on a raid that would carry all the way to Huntsville and Athens. On 12 July, Turchin’s Second Cavalry Division left its camps around the village of Salem, six miles from Winchester. Clumsy and obese, Turchin cut a poor figure on a horse, an image hardly improved by the presence of his sharp-tongued wife, Nadine. Mitchell’s First Cavalry Division followed Turchin’s troopers a day later. Stanley left behind Watkins’s brigade and the Second Tennessee Cavalry (Union) regiment, scouting for Sheridan. On 15 July, Stanley’s divisions united at Huntsville and probed to the Tennessee River. Bragg interpreted Stanley’s aggressive actions as the precursor to a raid toward Atlanta, and he reinforced the city. Stanley, however, focused solely on gathering Confederate resources from the Huntsville area. The town was almost devoid of men, as many planters had departed with their male slaves. Those that remained lost their workers to Stanley’s cavalrymen, who scoured the surrounding country for male slaves, horses, mules, forage and food of all kinds. Also visited was the town of Athens, the place whose sack the previous year had led to Turchin’s court martial. This time the Federals were more circumspect but no less thorough in seizing usable assets. After a few days the Federal cavalrymen left Alabama and returned to the army’s right flank. On 22 July Stanley wired Rosecrans that he had subdued the region’s inhabitants, had found few Confederates picketing the Tennessee River, and learned most of Wheeler’s cavalry was around Kingston, Georgia. He reported capturing 300 slaves, 500 horses, and an equal number of mules. Disgusted with Turchin’s dilatory movements and inadequate horsemanship, Stanley renewed his call for Turchin’s removal from cavalry command.23

The slaves brought within Federal lines by Stanley, like those gathered by Wilder earlier, were not fated to spend the remainder of the campaign as laborers. Federal policy by the summer of 1863 had evolved to the point of raising, equipping, and employing African American combat units, and Rosecrans’s Department of the Cumberland was slated to be a major participant. Adjutant General Thomas had been instructed by Secretary of War Stanton in the spring of 1863 to expedite the formation of African American regiments. While he concentrated upon the Mississippi River valley for the bulk of his work, Thomas eventually turned his attention to the Army of the Cumberland. On 12 July, just before he departed Tullahoma for Nashville, Rosecrans wrote Thomas seeking specific instructions on how to implement the process in his department. He also put his staff to work on the administrative details. The point of rendezvous for the slaves was to be the Elk River bridge camp of the First Michigan Engineers, and Innes was placed in overall charge of the process until other officers could be selected for the duty. Commanders of garrisons in the army’s rear areas were directed to furnish able-bodied African American men for the project, with another rendezvous site established at Nashville. There was no thought of having any other than white officers for the new commands, and Rosecrans on 18 July directed that lists of applicants for command positions in the new black regiments should be gathered for selection. As Rosecrans relaxed in Nashville, mustering officers and thousands of blank forms began to arrive at Elk River. When Stanley returned from his expedition on 22 July, he received orders to organize the African Americans he had brought within Federal lines into companies of infantry. Four days later Rosecrans queried Adjutant General Thomas about tables of organization and pay. The creation of African American combat units in Rosecrans’s department would be slow and difficult, but he had at least put the process in motion enthusiastically.24

By 23 July Rosecrans’s delay in leaving Nashville was raising concern both at Winchester and in Washington. Acknowledging the pleas of the staff, Garfield that day expressed his hope that Rosecrans would soon return to the army, but he admitted that he did not know when that would occur. Much more ominous was a curt message from Halleck at 3:00 P.M.: “Telegraph the position of your army, and what is known of Bragg’s present position.” Before responding, Rosecrans queried Thomas at Decherd for the latest information. Thomas simply repeated the account of an agent that had been forwarded to Nashville two days earlier. In his response to Halleck, Rosecrans summarized the agent’s report, which was reasonably accurate, and added a terse summary of his own troop locations. On the following day, Halleck pushed harder, telling Rosecrans that if he waited much longer to resume his advance, Bragg and Johnston might unite against him. Halleck then proceeded to lecture Rosecrans on how to move rapidly by reducing his trains and living off the land. He closed with a clear statement of how Rosecrans’s efforts were viewed in Washington: “There is great disappointment felt here at the slowness of your advance. Unless you can move more rapidly, your whole campaign will prove a failure, and you will have both Bragg and Johnston against you.” In case Rosecrans did not understand the message conveyed in his official telegram, Halleck sent a second note, marked “private and confidential.” Taking umbrage at Rosecrans’s tone, Halleck was blunt: “The patience of the authorities here has been completely exhausted, and if I had not repeatedly promised to urge you forward, and begged for delay, you would have been removed from the command. It has been said that you are as inactive as was General Buell, and the pressure for your removal has been almost as strong as it has been in his case.” Conceding that Rosecrans’s logistical challenges were real, Halleck closed, “The dissatisfaction really exists, and I deem it my duty, as a friend, to represent it to you truly and fairly.”25

On 25 July, Rosecrans responded directly to Halleck’s official message, alluding to his private admonitions as well. He calmly stated that he need not be told to reduce baggage and scavenge the enemy’s country because he was already doing those things. He asserted that a dispassionate observer would understand his reasons for not resuming the advance at once. He then suddenly addressed Halleck’s private warning about Washington’s displeasure: “I confess I should like to avoid such remarks and letters as I am receiving lately from Washington, if I could do so without injury to the public service. You will, I think, find the officers of this army as anxious for success, and as willing to exert themselves to secure it, as any member of the Government can be.” Having made his point about Washington interference, Rosecrans returned to the difficulty of sustaining an army in the barren territory between him and Chattanooga. Halleck again responded with two messages. Officially, he patiently reiterated Lincoln’s desire to see the citizens of East Tennessee liberated from Confederate control. Privately, he conceded the argument for the moment: “Whatever I have written or telegraphed to you on this subject has been from motives of kindness and friendship. It was my only desire to impress upon you the wishes and expectations of the Government, in order that you might be fully acquainted with those wishes. Having now explained to you frankly that you can have no possible grounds for your tone of displeasure toward me, I shall not again refer to this matter.” Halleck had placed Rosecrans on notice that Lincoln’s and Stanton’s patience was limited. In truth, Rosecrans recognized this, and he responded: “Assure the President that whatever prudence & energy we have shall be put to work to save and hold that region, but these must go together or the last state of those loyal men will be worse than their present condition.” He thus acknowledged Lincoln’s desire for an immediate advance but failed to understand that Halleck was warning him about Secretary Stanton as well.26

In the midst of his discussions with Halleck, another contentious issue between Rosecrans and the War Department remained outstanding. Rosecrans had long contended that he needed a more robust mounted arm to counter the Confederate cavalry facing him. Wilder’s mounted infantry brigade had been an expedient response to that need. Now Rosecrans was offered an opportunity to solve the problem more comprehensively through a proposal generated by Lovell Rousseau, commander of the First Division, Fourteenth Corps. Rousseau proposed to raise an independent corps of more than 10,000 recently discharged veterans, mounted and armed with repeating rifles, which would augment Stanley’s cavalry. In sum, Rousseau wanted to replicate Wilder’s brigade on a much larger scale. The number of horses and weapons required to create such a force was so large that prior War Department approval and support would be required. Needing an assistant to help him advance his scheme, Rousseau selected Col. John Sanderson, commander of the Fifteenth United States Infantry regiment. Only one battalion of Sanderson’s unit was presently with the army, leaving Sanderson essentially without a command. Newly arrived, and with little to do, Sanderson readily agreed to join Rousseau. While waiting for Rosecrans to return to the army, Rousseau sent Sanderson and brigade commander John King to explain the scheme to Thomas. Receiving Thomas’s assent, Sanderson and Rousseau next journeyed to Nashville to present their plan to Rosecrans. Gaining an audience with the army commander on the evening of 25 July, they obtained his enthusiastic approval. Rosecrans authorized Rousseau to visit the War Department and present the plan to Stanton and Halleck. Sanderson would accompany Rousseau as his prospective chief of staff. Armed with supporting letters misleadingly headed Winchester, Rousseau and Sanderson departed early on 27 July. Rosecrans meanwhile authorized Thomas to appoint a new commander for the First Division.27

James Garfield was undoubtedly privy to the tart messages passing between Rosecrans and Halleck, as well as the potential ramifications of Rousseau’s mission to Washington. A politician to the core, Garfield could see that Rosecrans was incautiously alienating powerful factions capable of crushing him and all who served him. Already elected to Congress, Garfield could resign at any time, but he preferred to leave after a successful campaign. Too, he was a citizen soldier who did not have the professional’s concern for logistics and terrain. Finally, he burned with abolitionist zeal and desperately wanted to advance the cause for which he believed the war was being fought. It is impossible to determine which motives primarily drove Garfield’s thinking, but clearly one or more caused him to write privately to his mentor, Salmon Chase, on 27 July. In that letter he bemoaned the fact that Rosecrans whiled away the hours in Nashville. Even as he spoke positively about Rosecrans and his army, Garfield made it plain that he had favored a more aggressive stance well before the Tullahoma campaign. To emphasize the point, he reviewed the controversy in which every general except Garfield had counseled delay in beginning the campaign. To Garfield’s mind, the resulting victory offered a great opportunity to continue the campaign as soon as the Elk River bridge was reconstructed. The bridge had been finished for more than a week, yet there was no sign of another advance. Baldly stating that he had urged a different course, Garfield damned Rosecrans’s inactivity: “Thus far the General has been singularly disinclined to grasp the situation with a strong hand and make the advantage his own. I write this with more sorrow than I can tell you, for I love every bone in his body. … But even the breadth of my love is not sufficient to cover this almost fatal delay. … I beg you to know that this delay is against my judgment and my every wish.” Garfield thus placed himself on the record as an advocate for a different policy in case events unfolded badly for the Army of the Cumberland.28

While Garfield and the War Department fretted over Rosecrans’s delays, the infrastructure to support an advance beyond the Cumberland Plateau slowly fell into place. The key to logistical success was the Nashville & Chattanooga Railroad, which would have to carry a much greater volume of traffic than it had before the war. Thus the First Michigan Engineers and Mechanics implemented a detailed program of improving such mundane structures as water tanks. Even with improvements, the line would be overwhelmed if forced to carry all the army’s supplies to Stevenson. Because Rosecrans envisioned approaching the Tennessee River on a wide front, he needed other locations to serve as supplementary supply dumps. Just beyond Cowan another railroad left the N&C and climbed the Cumberland Plateau before ending at a small village named Tracy City. Named the Sewanee Railroad when built in the late 1850s to tap rich coal seams on the plateau, the twenty-mile railroad rose 900 feet in eight miles by using grades of nearly 3 percent and curves approaching seventeen degrees. Nevertheless, if the Sewanee Railroad could haul supplies to Tracy City, it could sustain one of Rosecrans’s corps in the coming advance. On 22 July, Lieutenant Colonel Hunton led a survey party up the steep track and found it usable. From Decherd, the Winchester & Alabama Railroad ran thirty-two miles to Fayetteville, Tennessee. A company of the First Michigan Engineers labored to put that road in running order to support the Cavalry Corps. Yet most of the activity remained concentrated on the Nashville & Chattanooga main line, which by the end of the month saw up to eight trains per day hauling supplies and passengers to the army. Woe to the commander who interfered with the work of railroad personnel, as Sheridan discovered when he arrested a conductor. A sharp reprimand from Rosecrans restored the conductor to duty, representing an object lesson in the primacy of railroads in the army commander’s thinking.29

During the final week of July the Federal understanding of Confederate activities became somewhat clearer. First, Van Cleve at McMinnville decided to probe beyond the mountain wall facing him. After infantry expeditions yielded only a few guerrillas, Van Cleve mounted sixty-five artillerymen, placed them under artillery chief Capt. Lucius Drury, and sent them beyond the Cumberland Plateau into the Sequatchie Valley on 22 July. They rode north almost to the head of the long, narrow valley, passing through the villages of Dunlap and Pikeville, before returning to McMinnville via Sparta. Drury’s party encountered only a few Confederate commissary personnel buying cattle and a handful of home guards and deserters. After destroying a few weapons and killing a Union sympathizer by mistake, the scouting party reported the Sequatchie Valley essentially free of Confederate forces. While Van Cleve was sweeping the Sequatchie Valley, a Truesdail agent named M. D. Thompson on 25 July reported the result of a daring trip to Atlanta. Under the pretense of visiting his uncle, Thompson gained a pass from the Chattanooga provost marshal’s office and boldly took the train southward. At Atlanta he observed an abundance of quartermaster stores but few commissary items. He also noted Moses Wright’s efforts to create a local defense force. Returning to Chattanooga by train, Thompson accurately described the Confederate order of battle, Hardee’s departure, and the general location of Wheeler’s Cavalry Corps. He also noted the brigade at Bridgeport, the small number of railroad bridge guards, and the removal of the Kelly’s Ferry pontoon bridge to Chattanooga, then being fortified. Some of his information was corroborated by a deserter from the Fourth Georgia Cavalry regiment. Further confirmation came from Sheridan, who reported on 25 July that a Confederate engineer lieutenant had deserted to the Federals at Stevenson with current information and maps. The “lieutenant” was Conrad Meister, a German-born civilian draftsman who had been working in Stephen Presstman’s engineer office.30

Unwilling to remain passive in the Crow Creek valley, Sheridan on 25 July informed Garfield that he would reinforce Bernhard Laibold at Stevenson with his remaining regiment, the Forty-Fourth Illinois, and a section of Battery G, First Missouri Artillery. Simultaneously, he sent William Lytle’s Twenty-Fourth Wisconsin and Twenty-First Michigan Infantry regiments and a section of the Eleventh Indiana Battery to Anderson Station. While Sheridan was reinforcing Laibold, Confederate commander Patton Anderson was mounting an operation of his own. When the Confederates had evacuated Bridgeport early in the month, they had destroyed everything of value except a steam-powered sawmill. In an effort to recover the machinery, Bragg sent Anderson the small steamboat Paint Rock from Chattanooga. When the Paint Rock arrived on the morning of 27 July, Anderson loaded a working party and Company A, Ninth Mississippi Sharpshooter battalion, onboard and sent them across the river to Bridgeport. While the laborers were rigging the machinery for movement, they were fired upon by part of the Second Tennessee Cavalry (Union). Capt. William Tucker’s sharpshooters repulsed the Federal horsemen at the cost of one man wounded. Nevertheless, Anderson elected to leave the machinery to the Federals and sent the Paint Rock back to Chattanooga. When Laibold reported the incident to Sheridan, he noted that the Confederates appeared to be removing more of the railroad bridge as well. Anxious to avoid that outcome, Sheridan told Rosecrans on 28 July that he would visit Bridgeport in force on the next day. This slow but steady growth of the Federal presence at Stevenson and Bridgeport would inevitably become more visible to the Confederates across the river, whether Rosecrans desired it or not.31

In his report, Sheridan proposed to occupy Bridgeport in strength by bringing Bradley’s Third Brigade forward from University Place. He further suggested that Bradley’s position on the mountain be taken by a brigade from another division. Energized by the threat of additional damage to the bridge, Rosecrans agreed to Sheridan’s proposal and directed that a brigade from the Fourteenth Corps replace Bradley’s troops. The new orders transformed a tentative probe from Stevenson into a much larger operation involving elements from separate corps and requiring supervision by army headquarters. Until that supervision was in place, Sheridan bore full responsibility for the advance. Recognizing that fact, he issued specific instructions to Laibold: “I want you to be exceedingly careful in your advance on Bridgeport to-morrow morning. Send the cavalry well in your advance and on your right flank. Let your topographical engineer make an accurate sketch of the country and report the result of your reconnaissance. Do not let the enemy draw you into any trap.” Laibold began his advance early on 29 July with the Forty-Fourth and Seventy-Third Illinois Infantry regiments, a section of Battery G, First Missouri Light Artillery, and Daniel Ray’s Second Tennessee Cavalry (Union) regiment. While he was gone, Sheridan instructed Lytle to repair the road leading from University Place down into the Crow Creek drainage. With the railroad now working to Stevenson, the Cowan tunnel was unsafe for infantry and unsuitable for wagon traffic. The Crow Creek road, merely a rough path, had to be improved for use by wheeled vehicles if Sheridan’s movements were to be sustained in the future. With the bulk of the Third Division advancing beyond the Cumberland Plateau, Sheridan planned to bring the division headquarters to Stevenson as soon as the condition of the road would permit. To support Sheridan, the Second Brigade of Reynolds’s Fourth Division, Fourteenth Corps, abandoned its camps around Decherd, passed through Cowan, and began its ascent to University Place.32

The advance of several brigades beyond the Cumberland Plateau signified to perceptive observers that the Army of the Cumberland’s long rest period would soon be ending. Ever since the completion of the railroad to Estill Springs, and especially after the Elk River bridge was restored, life for Rosecrans’s soldiers had markedly improved. To keep the men too busy for mischief, commanders instituted a regular schedule of drills, beginning at the company level and proceeding through regimental formations to brigade tactical evolutions. Conducted whenever the weather permitted, the drills were leavened with periodic inspections and culminated in weekly dress parades. Officers with inadequate knowledge of the tactical manual were encouraged to study their drill books diligently. In at least one unit, the Thirty-Sixth Ohio Infantry regiment, they were called upon to recite what they had learned publicly. Beyond the daily drills, long hours were devoted to improving the regimental camps by sweeping the ground, removing trash, and building bowers of foliage to shade the men’s shelter tents. In addition, there were large levies for fatigue parties to supplement the work of the Pioneer Brigade. Thus the Eighteenth Ohio Infantry regiment built platforms to keep supplies out of the mud, and the Nineteenth Illinois Infantry regiment unloaded railroad cars and guarded the stacks of boxes and barrels arriving daily. The Seventy-Fifth Indiana Infantry regiment diligently labored to improve the road ascending the Cumberland Plateau to University Place, killing large numbers of rattlesnakes in the process. Regiments throughout the occupied zone scoured the countryside for forage for their animals, stripping the fields bare. While necessary, such foraging caused a few pangs of conscience, as Capt. Thomas Honnell acknowledged to his brother Eli: “We have cleaned out almost everything. We can not get a bit of old corn or hay so we cut grass & oats take wheat & rye out of the shock drive in all the cattle for beef and just sweep everything before us. I don’t know how the citizens are going to live.”33

In several regiments much of the camp improvement work was expended on building houses of worship. At Tullahoma, the Forty-Ninth Ohio Infantry regiment cut and arranged tree branches into a large bower for religious services. Not to be outdone, the Thirty-Sixth Ohio Infantry regiment at Cowan constructed a 500-seat semipermanent structure. The men were so pleased with their handiwork that they engaged the defecting Confederate draftsman, Conrad Meister, to draw pencil sketches of the chapel that would be lithographed in Chicago for souvenirs. Most regiments employed chaplains, who labored diligently but not always successfully in maintaining the spiritual health of their commands. In the Army of the Cumberland, most commands followed the lead of the commanding general, who preferred to rest on Sunday, leaving it for divine services and reflection. Thus many diaries speak of religious services held weekly. Such services often included baptisms, as Pvt. Jackson Webster of the Tenth Wisconsin Infantry regiment recorded on 26 July: “Seen 1 poured and 7 emersed by the Chaplain of the 38th.” Before conducting a baptismal service in the afternoon of 19 July at Hillsboro, Chaplain John Hight of the Fifty-Eighth Indiana Infantry regiment attended a fellow chaplain’s services. Sadly Hight recalled, “Chaplain Crews preached an able sermon, but the attendance was very poor. … I do not think it is on account of any personal dislike on the part of the men, but they simply do not want to hear preaching.” Some soldiers attended services for other reasons, as Capt. Daniel Howe of the Seventy-Ninth Indiana Infantry regiment at McMinnville explained, “A good many soldiers went to church in town to-day more I suspect to see the pretty girls than from religious motives.” Equally honest was Cpl. William Miller of the Seventy-Fifth Indiana Infantry regiment, who wrote from Decherd on 26 July, “There was preaching in camp but it is very hard to get the majority of the men to meeting.”34

Spare time in the camps was spent in a variety of ways. The more cerebral soldiers read books and newspapers. Indeed, the railroad brought current Nashville papers, and day-old Louisville and Cincinnati papers. As a supplement, some soldiers in Winchester began publishing their own paper on 12 July. For the nonreaders, swimming was a favorite diversion, while others used smaller streams for bathing and washing their uniforms. Berrying continued to be a favored pastime throughout the area. Some soldiers chose to visit civilian dwellings. When the sound of a piano enticed two men into a Winchester home, they found three pro-Confederate women who cordially conversed with the two young soldiers as if it were peacetime. At Pelham, Musician Hiram Hines and a friend spent all day visiting two families who lived near their camp. At University Place, Pvt. James Riley regularly visited pro-Union families in the valley beyond the mountain, especially if young women were present. Yet not everyone saw the mountain folk in such a positive light. Referring to the residents of Anderson, Pvt. George Cummins was vitriolic: “The most of the inhabitants are ignorant and immoral, abject poverty stricken, God forsaken, hell deserving set of animals in human shape.” Conversely, Sgt. John Marshall participated in gathering army rations to feed destitute civilians at Pelham. For those soldiers who preferred to avoid the civilian population, there were many natural wonders to visit. Capt. David Claggett and other officers explored the mountains from their McMinnville camp. Sergeant Marshall marveled at a large cave and spring near his camp at Pelham. Lt. Jesse Connelly and chaplain James Johnston pondered the age of the Old Fort, an ancient fortification near Manchester. Still others remained in camp, whiling away the hours in games like chess and checkers. Soldiers in the First Michigan Engineers and Mechanics organized a circus. At the same time, the junior officers of the command instituted a series of horse races.35

For all of the troops, writing and receiving letters was the most common activity beyond the dull routine of the duty day. With the railroad at last operating efficiently, men could correspond with family and friends, hindered only by the occasional lack of paper and stamps. In that way, Lt. Col. William Ward learned on 22 July of the birth of his son. Col. John Parkhurst, a widower, used a letter to justify to his sisters a new child-care arrangement for his minor children. Pvt. Joshua Dewees learned from a letter on 17 July that his brother had been killed at Gettysburg two weeks earlier. Pvt. James Phillips shared some stern advice with his wife on 18 July: “You must learn that baby to get along without so much tending[,] put him in the Cradle and let him lay there and squall if he wants to and not kill your self lugging him around if you have got a cradle[,] if you have not buy one.” Often, raw emotions were on display. Surgeon Josiah Cotton told his wife, “I promised you that I would do nothing that would make you or the children blush to meet me, and I have not. I believe that absence has rather increased my love for you. I always loved you more than you would give me credit for.” Crushed by his fiancée’s seeming rejection of their engagement, Capt. James Love replied, “What have I done? What have I put in those letters that should change you so in one short week?” Other writers simply described their circumstances and asked for items difficult to procure locally. Col. Hiram Strong asked his wife to send him some commercial maps of Virginia, Maryland, and Pennsylvania so that he could follow events in that theater. In a letter to his wife, Cpl. Alanson Ryman was specific in his wants: “You may send me some dried beef and a small cheese and some honey if you can get it. These are about all the articles that I care about except it may be some good whiskey.”36

Extant soldier letters from the Army of the Cumberland during the month of July 1863 indicate that morale was high, almost without exception. Not only were the men pleased that their own Tullahoma campaign had been so successful, but the Union victories in other areas added to the general feeling that the war would end soon. Through newspapers and letters, Rosecrans’s soldiers followed Grant’s Vicksburg and Jackson successes, Banks’s victory at Port Hudson, and even Meade’s incomplete triumph at Gettysburg. They also believed the garbled success stories emanating from the Department of the South, where hard fighting was occurring in Charleston harbor. Only Confederate raider John Morgan’s foray north of the Ohio River raised concerns, and then solely in terms of the safety of family and friends. In fact, many soldiers welcomed Morgan’s trek through southern Indiana and Ohio, if only to show Northern citizens what war was like. Illustrative is the letter of Pvt. William Forder to his wife, Sarah, on 19 July: “I have no dout but what it is the best thing that ever happened for it will show the Butternuts what the rebs would do if they had a chance.” Capt. Henry Richards wrote on 21 July: “The boys out here don’t feel much sorry that Morgan has paid some of their friends in Ohio and Indiana this visit.” A similar view prevailed regarding the New York City Draft Riots. Lt. Daniel Howe, for example, wrote on 16 July, “I am amazed at the riots in New York. The whole power of the Government should be used to push the draft to the last extremity if it deluges the North with blood.” While some expressed strong abolitionist sentiments, others begged to differ. One such was Pvt. Joshua Foster, who told his parents of his anger after reading a Cincinnati newspaper: “Now all that do not belong to the Union Party are Copperheads, and that makes me so mad I don’t know how to keep down. I am for The Union and The Constitution as they used to be, yet my party name is Democrat.”37

During the latter half of the month, army paymasters made their rounds, distributing four months of pay. For a private soldier, the sum amounted to $52 before any deductions were made. An officer’s pay was considerably higher. For example, Col. Sidney Post, commanding a brigade in the Twentieth Corps, received $780.80 on 21 July, from which taxes of $17.42 were deducted. The paymaster paid Post $263.38 in cash, and gave him a $500 draft on a government account in Louisville to be mailed to his wife in Galesburg, Illinois. For those men who desired to send money home, several methods were available. In some regiments the regimental chaplain took the money north and distributed it from there. Others utilized officers going home on furlough or recruiting duty. Indiana soldiers could avail themselves of a state-sponsored service whereby stipulated sums could be withheld from their pay, credited to the state, and disbursed by state agents to designated recipients in Indiana. Otherwise, the sole alternative for the soldier attempting to send money home was to place it in a letter and trust to luck. Of course, many men kept their pay and disposed of it in their camps. Pvt. William Christian wrote in his diary on 22 July, “We are living high while the money lasts. Condensed milk, cakes.” At least Christian got something for his money. A great many other soldiers immediately engaged in games of chance. In the words of Pvt. John King, “I found that there was a perfect chuck-luck mania passing through the army. Nearly every regiment and company had men, sometimes more or sometimes less, who were daily playing chuck-luck and the only reason I could give for it was that the men all had their pay and there was nowhere the money could be spent.” Lt. Jesse Connelly at Manchester noted on 23 July how payday attracted unsavory types: “Gamblers are lurking under the creek bluffs fleecing the unsophisticated of their hard earned pay.”38

Payday compounded the normal problems of discipline in an army of boisterous young men. Many soldiers used their momentary windfall to purchase liquor, with predictable results. Two days after payday, Pvt. Francis Kiene reported that many men in his unit were drunk. Lt. Chesley Mosman wrote in his diary on 23 July, “Get paid. Universal 4th of July drunk. One man stabbed two of the Company. Fighting drunk.” In Granger’s Reserve Corps, the situation prompted a response from Rosecrans himself: “A staff officer having reported that there are constantly a great number of intoxicated soldiers at Wartrace, the General Comdg. directs that you make such laws in regard to selling liquors that will insure good order there, and at all places under your command.” At University Place, sixteen soldiers partied so openly that they were arrested by the brigade provost guard. At Tullahoma, Chaplain George Phillips recorded, “At night news came of the capture of Morgan and his men, which with the absence of the Col. led some of the officers of the Regt to take a spree and some of them acted like crazy men.” In Manchester, Pvt. George Botkin wrote, “Gobbled up a little of Old Bourbon whiskey & get as happy as a coon.” Also in Manchester, Col. Charles Rippey “gave an order to some of the boys to get whiskey at the Commissary, and some of them got full and had quite a time.” Tolerance for occasional intoxication often extended to other misdeeds. Theft and vandalism were often punished lightly or not at all. When soldiers broke the cornerstone of the University of the South and scattered its contents, Sheridan offered a reward for the “unmitigated raskel” who perpetrated the deed, but nothing came of it. More serious crimes elicited more severe punishment. In one regiment a deserter was drummed out of camp and remanded to prison. A cavalryman was dismissed from the service for burning a cotton mill. And two men from the Pioneer Brigade were sentenced to thirty days’ hard labor with ball and chain for attempted rape.39