6

ROSECRANS MAKES A PLAN

» 30 JULY–14 AUGUST 1863 «

Refreshed by his fifteen-day sojourn in Nashville and cheered that his wife and three of his children remained with him, Rosecrans quickly resumed his frenetic pace. On the morning of 30 July he inspected the handiwork of the First Michigan Engineers and Mechanics at the Elk River bridge. Braving a violent storm that wrecked camps from Estill Springs to Cowan around noon, he spent the afternoon reconnoitering fifteen miles up the Winchester & Alabama Railroad toward Fayetteville, where much of the army’s cavalry was located. During the trip he dictated a flurry of messages to subordinates about projects he deemed to be lagging. Just as they had before Rosecrans left for Nashville, most of these messages involved the Nashville & Chattanooga Railroad in some way. Having found the steam dummy useful as a command vehicle, Rosecrans was incensed when it broke down briefly and demanded that it be repaired at once or a substitute sent from Louisville. Further, he inquired if the dummy could safely transit the Cowan tunnel without modification. Nor was that all. Rosecrans also complained that the locomotive supporting Sheridan’s troops beyond the Cumberland Plateau was too weak to pull more than six cars over the mountain, and he wanted it replaced. He also demanded to know the location of the construction train. All these messages fell upon harried railroad superintendent John Anderson in Nashville and assistant superintendent John Beggs at Decherd. Rosecrans’s tendency toward micromanagement was exemplified by other messages on the same day: to George Thomas, about pack animal panniers; to Captain O’Connell of the Pioneer Brigade, about the size of woodcuts; to James Morgan at Murfreesboro, about ammunition magazines and tarpaulins. In the midst of all the activity, Rosecrans found the time to authorize a brief leave for Maj. William McMichael, who had kept the headquarters functioning while Rosecrans and his principal staff officers were in Nashville.1

On 31 July Rosecrans took the dummy to Cowan, where he met Sheridan, whose division represented the vanguard of the army. Because of the continuing absence of McCook, Sheridan continued in temporary command of the Twentieth Corps, while Lytle commanded Sheridan’s division. Sheridan quickly recounted for the army commander what had been done to facilitate the army’s advance to the Tennessee River. Laibold’s Second Brigade had occupied Stevenson and the Crow Creek valley on 20 July, and in subsequent days Sheridan had tried to push other portions of his division beyond the Cumberland Plateau. His brigade commanders were more cautious than Sheridan, however, and the results were disappointing. Laibold had made only a weak probe to Bridgeport on 29 July, Bradley’s Third Brigade had remained atop the mountain because it was short of rations, and only half of Lytle’s First Brigade had made it to Anderson Station. Unsatisfied with such slow progress, Sheridan on 30 July urged his subordinates to greater effort. On that day, Lytle sent the remainder of his brigade from Cowan beyond the Cumberland Plateau to Anderson. Lytle himself took a train to Stevenson and was temporarily marooned there when the engine broke down. Sheridan ordered Laibold to return to Bridgeport with the Seventy-Third Illinois and Second Missouri Infantry regiments, making the occupation of that site permanent. At the same time, Bradley’s command reached the valley floor at Battle Creek, a few miles north of Bridgeport, and would occupy the works overlooking the railroad bridge on the next day. Thus Sheridan reported to Rosecrans that six regiments were at or near Bridgeport, two at Stevenson, and four on the railroad around Anderson and Tantalon Stations. Sheridan’s entire division was now beyond the Cumberland Plateau, the first barrier on the way to Chattanooga.2

Pleased by Sheridan’s initiative, Rosecrans was less satisfied with the logistical support of the division. The Cumberland Plateau was mostly barren, and the corn crop in Sweeden’s Cove, along Crow Creek, and in the Tennessee River valley was not yet ripe. The Nashville & Chattanooga Railroad, therefore, was the lifeline for Sheridan’s scattered units. Worst off were Lytle’s two regiments at Anderson and Tantalon, which Sheridan complained were out of both rations and forage. Further, Sheridan wanted to take an engine to Bridgeport, but the only one under his control was broken. He knew there were engines at Decherd, but he had been told by the army’s quartermaster that John Anderson would have to authorize their use. Knowing how to influence Rosecrans, Sheridan described the situation in dire terms: “Must the men starve on account of culpable negligence?” Rosecrans quickly ordered assistant superintendent Beggs to provide an engine immediately for Sheridan’s use. Two companies of the First Michigan Engineers and Mechanics regiment accompanied the train to rebuild the Widows Creek bridge between Stevenson and Bridgeport. Still, the efficient Beggs could not save Anderson from Rosecrans’s wrath on another railroad matter. With the Fourth Division of the Fourteenth Corps already spreading across the top of the Cumberland Plateau behind Sheridan, it too would need the rations that only rail transport could provide. The Sewanee Railroad, which climbed the mountain at Cowan before turning northward to the Tracy City coal mines, would be needed to support troops in that vicinity. Steep and crooked, the railroad had not appeared to Anderson to be a viable conduit for supplies, and he had done nothing to facilitate its use, neglecting to procure engines capable of the climb. Now Rosecrans discovered that the engines were unavailable, and he expressed his frustration to Anderson. Declaring that the result would be “millions in delay,” Rosecrans pointedly reminded Anderson that he had been warned months before to prepare equipment far in advance of need.3

Back at his Winchester headquarters on 1 August, Rosecrans spent a frustrating day. He wanted to take the dummy to Shelbyville in the afternoon, but it was unavailable—another mark of Anderson’s inefficient management. When Anderson’s reply to Rosecrans’s earlier rant arrived, it caused even more dissatisfaction. Unlike the accommodating Beggs, Anderson maddeningly stated that he had been unaware of Rosecrans’s desire to use the Sewanee Railroad. Nevertheless, he would endeavor to repair a coal-burning engine to be placed on the road. Thus Anderson offered no apology, pleading simple ignorance instead. Frustrated that the day’s plans were thwarted, Rosecrans resumed the contentious dialogue with his superiors in Washington. Writing privately to Halleck, he explained that his Louisville base was 264 miles to the north; his Nashville depot was 83 miles in his rear; and he confronted a 60–70 mile swath of barren country. Thus the railroad must supply the army until it could come to grips with the enemy. That enemy lay beyond a great river and was fortified in a mountainous region offering multiple options for advance or retreat. Rosecrans believed no advance should be attempted unless success was assured. To guarantee that success, he proposed to rebuild the railroad, establish secure supply depots, develop a means to cross the Tennessee River, and prepare to maintain himself beyond it. Only then would he seek the enemy. He would execute that sequence as rapidly as possible, but if the government thought otherwise, it should replace him at once. Rosecrans made the same arguments at greater length in a separate, unofficial letter to Lincoln. After recapitulating his tenure as commander of the Army of the Cumberland, Rosecrans noted how much his army had accomplished, all without water-borne support (like Grant) or short distances and small rivers (like Meade). In his letter to the president, Rosecrans’s general tone was respectful, although his arguments occasionally verged on the condescending. Nor did he offer his resignation to Lincoln, as he had to Halleck.4

Not everyone in the Army of the Cumberland believed in Rosecrans’s methodical plan of campaign. Garfield continued to chafe at the delay, writing to his wife, Lucretia, on 1 August, “I don’t feel at all satisfied with the slow progress we are making and I expect to hear complaints and just ones, soon. There are the strongest possible reasons for using every moment now before the rebels can recover from their late disasters.” Try as he might, Garfield was unable to accelerate Rosecrans’s timetable, a frustration of long standing that may have exacerbated the severe attack of piles then afflicting him. Yet Rosecrans was not to be hurried until the railroad had delivered sufficient supplies to sustain more than a single division beyond the Cumberland Plateau. On 2 August the army commander changed his mind about going to Shelbyville, proposing to visit Bridgeport instead, but when the steam dummy could not be ready in time he reverted to his original destination. Accordingly, assistant superintendent Beggs was bombarded by a flurry of messages from anxious aides until Rosecrans and much of his staff boarded the dummy for Shelbyville. Maj. Frank Bond, Rosecrans’s senior aide-de-camp, telegraphed Brig. Gen. Walter Whitaker, temporarily commanding Absalom Baird’s Reserve Corps division, that Rosecrans and up to ten guests would be arriving for the evening. Late in the afternoon, Rosecrans’s party departed Winchester for the two-mile trip to Decherd, then followed the mail train twenty-eight miles from Decherd to Wartrace. At the latter place the dummy diverged from the main line on the six-mile branch to Shelbyville. Before leaving with his commander, Garfield queried Lieutenant Colonel Hunton of the First Michigan Engineers and Mechanics about progress on the pontoons being constructed at the Elk River camp and the work on the Widows Creek bridge. With the railroad finally delivering tons of supplies, the bridging that would be needed at the Tennessee River was assuming ever-greater importance.5

Rosecrans and his party arrived safely at Shelbyville on the evening of 2 August. Shelbyville was the location not only of Whitaker’s headquarters but also that of Col. William Reid’s Second Brigade. During the morning of 3 August, Reid’s troops marched to a field west of town and passed in review before Rosecrans and Garfield. The day was hot and the march disagreeable, but the men took it all in good part. In one of the standard performances so beloved by his troops, Rosecrans addressed each unit individually. To the men of Battery M, First Illinois Light Artillery, he tipped his hat and said, “You are the healthiest, largest and best looking set of men I have yet seen in any battery, and I hope soon to meet you at the front.” Refreshed by the general’s remarks, the troops returned happily to camp, the heat and dust of the day washed away by their commander’s praise. The official party next boarded the dummy and returned to Wartrace, garrisoned by Col. Thomas Champion’s First Brigade of Whitaker’s division. There the Shelbyville ceremonies were repeated, during an even hotter afternoon. Rosecrans’s performance again worked its magical effect on morale. As a member of the 115th Illinois recalled, Rosecrans said “we needed a little more soup, thought we were not quite as fat as the boys in some of the other Regiments” but that “he believed us to be pretty long winded.” After telling the brigade it was “one of the finest he had ever seen in the service,” and that he “hoped to meet it even nearer the front,” Rosecrans and his retinue boarded the dummy and departed for Winchester. During the trip, his aide Capt. James Drouillard forwarded the location of all the army’s major elements to Halleck. In a note to John Beggs, he sought to arrange transportation for Rosecrans to Stevenson and Bridgeport on the morrow.6

The euphoria Rosecrans may have felt after visiting the troops at Shelbyville and Wartrace did not last long. Upon returning to Winchester, he learned that the dummy had to be modified before it could pass through the Cowan tunnel, delaying his visit to the front for several days. On 4 August two intemperate messages arrived from John Anderson, who railed against a series of complaints about him from several commanders. Sheridan wanted soldiers traveling without orders to be carried without charge, apparently contrary to Rosecrans’s policy of half fare. The provost marshal of the Fourteenth Corps condemned the mail and baggage handling on the passenger train, with civilians mingling freely with the mail and baggage agents. Worst of all, Thomas proposed the appointment of an “honest” railroad superintendent. Anderson strongly denied any implication of dishonesty and demanded either proof or disavowal of the charge by Rosecrans. Vexing as these petty quarrels were, they had a ready solution. Far more troubling was a two-sentence telegram from Halleck in Washington: “Your forces must move forward without further delay. You will daily report the movement of each corps till you cross the Tennessee River.” If he had thought Washington would accept his timetable after he described the obstacles to an immediate advance, Rosecrans was sorely mistaken. Most galling of all was the requirement to report daily any and all progress, as if he were a child being closely monitored. Gathering an escort from the Fifteenth Pennsylvania Cavalry, he rode to Thomas’s headquarters at Decherd, most likely to discuss Halleck’s peremptory order. At 5:00 P.M., he responded tartly. Acknowledging receipt of the order, he continued: “As I have been determined to cross the river as soon as practicable, and have been making all preparations, and getting such information as may enable me to do so without being driven back, like Hooker, I wish to know if your order is intended to take away my discretion as to the time and manner of moving my troops?”7

Rosecrans was truly miffed that the Lincoln administration seemingly could not understand his military situation. Could Lincoln, Stanton, and Halleck not see that the obstacles facing the Army of the Cumberland were quite different from those encountered by other Federal armies? How could they not be aware of the massive Cumberland Plateau, the wide Tennessee River beyond, and the 2,000-foot mountain ranges guarding Chattanooga? Were they not aware of the fragility of his single-track railroads, vulnerable to Confederate guerrillas throughout their length? Could they not appreciate the risk in relying upon those railroads for food, forage, and ammunition during the army’s advance? And what of Rosecrans’s opponent, the veteran Army of Tennessee, which had nearly been victorious at Perryville and Stones River? Whenever Rosecrans stepped outside his Winchester headquarters, the Cumberland Plateau dominated his view. Yet Lincoln, Stanton, and Halleck could not see the Cumberland Plateau from Washington, and their worldview was wider than the military geography of southeastern Tennessee. Vicksburg and Gettysburg had been great victories, but the war was by no means won. Worst of all, a precipitous decline in volunteering had forced the government to institute conscription. Less than a month earlier, New York City had exploded in a four-day riot over the draft. That unrest had been quelled at great cost, but a second draft was scheduled to be held in New York on 19 August. In the face of such unrest, the Lincoln administration desperately needed positive news before elections in key venues like Ohio. For Lincoln, Stanton, and Halleck, the Army of the Cumberland had to be part of the solution to what was essentially a political problem. The difficult situation facing Rosecrans therefore was largely irrelevant. Measurable progress simply had to be achieved before the fall elections. Thus the view from Washington did not mesh with the view from Winchester, and a test of wills was about to ensue.8

While he awaited an answer from Halleck, Rosecrans on 5 August continued his methodical preparations for an advance on his own timetable. There was some good news around the army. McCook had returned to Winchester on the previous day and resumed command of the Twentieth Corps. His first act was to organize a review of some of his troops for the benefit of his young wife, Kate, who had returned to Winchester with him. Crittenden was still absent from his Twenty-First Corps, but two of his three divisions had organized their supply trains, which were on their way from Murfreesboro to Manchester with twenty days of rations apiece. The army staff ordered railroad managers Anderson and Beggs to modify the dummy so that it could traverse the Cowan tunnel. Elements of the First Michigan Engineers and Mechanics continued to repair track and strengthen bridges. Garfield ordered six companies from the Pioneer Brigade to build platforms at Stevenson for the tons of supplies arriving there. In the rear, train service was interrupted when morning fog caused one train to crash into another, killing three soldiers and injuring many more. The line was blocked for some time, making mail delivery late throughout the army. Rosecrans himself went to the Winchester depot to witness the departure of two of his horses, which were being shipped to Cincinnati. One of the horses, no doubt, was the valuable animal given him by John Wilder the previous month. When the car was late to arrive, Rosecrans’s aides expressed the general’s displeasure in another flurry of telegrams to the hapless John Beggs. Toward evening a summer thunderstorm broke over the Winchester-Decherd area. About the same time, Halleck’s answer arrived from Washington. It was brief and pointed: “The orders for the advance of your army, and that its movements be reported daily, are peremptory.”9

Army of the Cumberland supply dump, Stevenson, Alabama. (Behringer-Crawford Museum, Covington, Kentucky)

Rosecrans spent much of the night thinking about how to respond to Halleck’s order, and composed a tentative answer in pencil. On the next morning he called Garfield, Thomas, McCook, and Stanley to a meeting to discuss his response. According to Rosecrans’s later statements, he read Halleck’s messages to the assembled generals, who were aghast at what they heard. When asked how he planned to respond, Rosecrans read his proposed reply. In the draft, he offered a tentative start date of 10 August for the army’s forward movement. He then shed light on the process by which he planned to develop a route across the Tennessee River. Current information indicated that a river crossing between Chattanooga and Bridgeport would be unwise, and he had not yet decided to make the crossing upstream from Chattanooga or downstream from Bridgeport. Most of his troops could not advance until that decision was made and sufficient supplies and bridging equipment accumulated to facilitate the crossing. Rosecrans pointedly concluded, “To obey your order literally would be to push our troops at once into the mountains on narrow and difficult roads, destitute of pasture and forage, and short of water, where they would not be able to maneuver as exigencies may demand, and would certainly cause ultimate delay and probably disaster.” Having stated that such a precipitous advance would be foolhardy, Rosecrans again offered his command to Halleck: “If, therefore, the movement which I propose cannot be regarded as obedience to your order, I respectfully request a modification of it, or to be relieved from the command.” As Rosecrans remembered it, the corps commanders, led by Thomas, offered their positive support, while Garfield remained silent. Accordingly, Rosecrans finalized his answer and shortly after noon telegraphed it to Washington. Later in the day he directed his corps commanders to maintain ten days’ rations and short forage (grain) packed for movement.10

Believing that he had answered Washington’s challenge successfully, Rosecrans rode to the Elk River bridge to inspect the black regiment forming there. While many in the Army of the Cumberland had reservations about arming blacks, Rosecrans harbored no such doubts. The mounted sweeps during the previous month had brought in hundreds of able-bodied men, most of them now gathered around Estill Springs. There they initially provided a labor pool to support the work of the army’s engineers. Under William Innes’s supervision, the former slaves were organized into companies temporarily commanded by Innes’s officers until a more formal officer selection process could be adopted. Similar activity occurred at Nashville, where other units were being organized under the auspices of Gordon Granger. On the previous day Rosecrans had reported to Adj. Gen. Lorenzo Thomas that 600 men had been enrolled at Estill Springs and 650 at Nashville, with 1,200 more potentially available. “When we get into Georgia, we can raise an army,” he enthused. While clerks struggled to complete the voluminous enlistment paperwork, army headquarters issued a call for prospective officers. This call generated much discussion among the army’s rank and file. While some vehemently opposed the idea of black soldiers, others saw a chance to escape the enlisted ranks and enthusiastically applied for the positions. Examining boards began to meet at Winchester and Nashville to select candidates from a growing list. John Beatty chaired the Winchester board. Nominally a fair and open procedure, the selection process soon became corrupted by favoritism and command influence. Especially egregious were the promises made, and broken, in regard to the regiment forming at Estill Springs, the Twelfth United States Colored Troops. Certain nearby units, such as the First Michigan Engineers and Mechanics and the Fifteenth Pennsylvania Cavalry, participated actively in the deal-making. Rosecrans himself was not above meddling, leading Kinsman Hunton of the First Michigan Engineers to remark that the army commander’s pronouncements on the subject were not to be trusted.11

The day of Rosecrans’s visit to Estill Springs was also the day established by presidential proclamation as a day of Thanksgiving. Although the occasion was meant to be observed throughout the army, the ceremonies varied according to the whims of division commanders. In the Fourteenth Corps, neither Rousseau’s First Division nor Negley’s Second Division seem to have taken notice of the proclamation. In contrast, the Third Brigade of Brannan’s Third Division held a full schedule of commemorative events. In the Second Minnesota Infantry regiment, the program included sermons delivered by members of the Christian Commission and music from the regimental band. The Eighty-Seventh Indiana Infantry regiment spent the entire day in speeches, sermons, and musical tributes, dampened only by a heavy rain shower just after noon. Similarly, Reynolds’s Fourth Division marked the occasion with prayers, sermons, and speeches in at least two of its scattered brigades. Perhaps because it was under Rosecrans’s own eye or perhaps because McCook’s wife remained in camp, Davis’s First Division of the Twentieth Corps threw itself into the spirit of the day in an extravagant fashion at Winchester. The usual round of prayers, sermons, and patriotic songs was supplemented by stirring speeches from McCook and Davis, and musical interludes furnished by three regimental bands. As in Brannan’s camp, brief but heavy rain sent people scurrying for cover early in the afternoon. In Tullahoma, miles from corps headquarters, Johnson’s Second Division marked the day in much more subdued fashion. The First Brigade’s August Willich declared a holiday from work, a practice also followed in Joseph Dodge’s Second Brigade. In the Twenty-First Corps, all three brigades of Wood’s First Division held services, but all the Second and Third Divisions could muster was a lighter duty day for most soldiers. Reserve Corps units at Wartrace and Shelbyville also followed this pattern. Confronting the enemy beyond the Cumberland Plateau, Sheridan’s Third Division of the Twentieth Corps took no part in the day’s festivities.12

Rosecrans was anxious to visit Sheridan’s regiments deployed at Stevenson and Bridgeport. By the morning of 7 August the dummy had been modified to pass through the Cowan tunnel, and Rosecrans and Garfield boarded it for the trip to the front. At least one newspaper reporter accompanied them, “A.L.F.” [Alfred Burnett], accredited to the Cincinnati Commercial. At Stevenson, the party added Sheridan and continued to Bridgeport. Many soldiers noted Rosecrans’s arrival, but Cpl. Edward Crippin was unimpressed: “The old gentleman looks odd in his citizen dress and chip hat.” At Bridgeport, Rosecrans found everything much as it had been since Laibold’s Second Brigade had occupied the site permanently on 30 July. Now nothing stood but a log shanty and the open shed formerly housing the dismantled sawmill. Everything else, both railroad station and dwellings, lay in ruins. Initially nervous in the face of so many Federal soldiers, the Confederate pickets had gradually become accustomed to their presence and an unofficial truce generally prevailed around the wrecked railroad bridge. Anderson’s Brigade guarded the far shore and picketed Long Island. The long bridge from the west bank of the river to Long Island was broken at both ends, but the draw span east of Long Island remained intact. Although they were peaceable, both sides carefully noted the daily arrival of trains on each bank. While their officers worried about security, many men on both sides of the river freely conversed across the wide but shallow western channel. Beginning as good-natured jesting, the conversations occasionally assumed a hard edge. Both Federals and Confederates used the river to swim, bathe, and fish, as did some local females, whose behavior was noted wryly in soldiers’ letters and diaries. On the day of Rosecrans’s visit, several men from Sheridan’s staff enticed Pvt. Daniel Crow of the Third Confederate Cavalry regiment to visit the west bank with the promise of his safe return. Crow paddled across the stream and chatted affably with the Federals before returning to his own lines.13

Rosecrans probably never met Private Crow, nor did the Confederate’s visit make its way into the army’s daily intelligence summary. Nevertheless, the army commander saw much of interest during his first visit to Bridgeport. Clearly, a major construction effort would have to occur before the Nashville & Chattanooga Railroad could be extended beyond the Tennessee River, even without further bridge destruction. Still, the railroad, fragile as it was, could bring supplies all the way to the west bank of the river if need be. As he pondered whether to cross the Tennessee above or below Chattanooga, Rosecrans could see that the Bridgeport crossing site held prominent advantages, especially if the sustainability of the army was a primary driver. Equally significant, Confederate forces in the area were no larger than an infantry brigade in strength, supported by a tiny handful of artillerymen and cavalrymen. Even with a working railroad, Bragg could not quickly reinforce the Bridgeport area and contest a crossing if Rosecrans could keep his preparations secret. The town of Stevenson, eleven miles from Bridgeport and three from the river, was an ideal place for a supply depot and headquarters site. If the Memphis & Charleston Railroad could be returned to operation from Stevenson to Decatur, Alabama (eighty-three miles), where it connected to the Nashville & Decatur Railroad, a second supply line could be opened via that route, easing the pressure on the Nashville & Chattanooga Railroad. Stevenson’s primary flaw was that it was visible from the top of Confederate-held Sand Mountain, beyond the Tennessee River and only five miles distant, although heavy vegetation obscured much of that visibility. Even if the Memphis & Charleston could not be reopened, the Stevenson-Bridgeport locality offered much to an army commander seeking a way through the maze of geographical obstacles between him and Chattanooga.14

With impressions of Bridgeport fresh in his mind, Rosecrans departed for Winchester. Before leaving Stevenson, he telegraphed Ambrose Burnside, commanding the adjacent Department of the Ohio. Halleck for some time had desired a collaborative advance on East Tennessee by Burnside’s and Rosecrans’s armies, and the two generals had been exchanging information for several weeks. Now both commanders were under the same peremptory orders to advance, and it was time to coordinate the movements of the two armies. Rosecrans explained to Burnside that he had made the town of McMinnville a supply depot in case Burnside’s advance approached Rosecrans’s left. He asked Burnside to provide him with concrete information on his plan of campaign so that the Twenty-First Corps could cooperate with Burnside’s movements, thereby assuring a united front against Bragg’s and Buckner’s forces. Burnside was notoriously slow in acting, so Rosecrans urged him to accelerate the process. Resuming his journey to Winchester, the army commander found upon his arrival that Halleck had responded to his churlish note of the previous day. Halleck wrote, “I have communicated to you the wishes of the Government in plain and unequivocal terms. The object has been stated, and you have been directed to lose no time in reaching it. The means you are to employ, and the roads you are to follow, are left to your own discretion.” Having successfully forced Halleck to back down, Rosecrans soothingly responded that he was doing everything possible to expedite his advance. He closed, “Will advise you daily.” By threatening to resign, Rosecrans had maintained his freedom not only to set the time of his advance but the route as well. Still, he perceived that the hour for commencing his campaign was fast approaching. Thus he informed his mother-in-law, Eliza Hegeman, in Yellow Springs, Ohio, that Anna Rosecrans would be leaving the army on 10 August, one of the potential dates for the campaign to begin.15

Rosecrans accelerated the pace of activity on 8 August. For some time Rosecrans’s family had been sharing quarters at Yellow Springs with the family of Brig. Gen. Eliakim Scammon, an associate of Rosecrans’s from their days in western Virginia. While Anna Rosecrans and three of her children visited the Army of the Cumberland, the youngest children, Carl and Charlotte, remained in Ohio with their grandmother Hegeman. Rosecrans’s telegram to Mrs. Hegeman triggered an instant response from Ohio that Charlotte was seriously ill. Rosecrans immediately arranged for his wife and daughters to leave for Yellow Springs that very afternoon. Ominously, he wired Mrs. Hegeman, “Telegraph if Charlotte is worse.” Rosecrans’s son, Adrian, fourteen, would remain with him a while longer. While an aide arranged his family’s travel, Rosecrans turned to army business with his accustomed habit of micromanagement. A flurry of telegrams ensued: to John Anderson, use every available freight car to move supplies forward, and come to headquarters as fast as possible; to Capt. Simon Perkins Jr., assistant quartermaster in Nashville, expedite movement of rail cars, with priority given to forage; to Sheridan, describe the nature of the ground at Caperton’s Ferry on the Tennessee River, and move lumber to Stevenson for shed roofs; to Capt. Ferdinand Winslow, acting chief quartermaster in Nashville, provide 100 horses for the Fifteenth Pennsylvania Cavalry regiment; to John Palmer, move the army’s reserve ammunition train from Manchester to Tullahoma at once, and send all extra supplies to McMinnville; to John Van Duzer, run a second telegraph line along the railroad; to Gordon Granger, order the First Battalion Ohio Sharpshooters from Normandy bridge to Winchester; to Calvin Goddard, return at once from leave as several staff members are ill; to Governor Andrew Johnson, please come for a visit tomorrow; and finally, to John Beggs and William Lytle, expedite the transportation of Mrs. Margaret Bybee, Confederate Brig. Gen. Patton Anderson’s mother, to Bridgeport.16

That same day, Chief Quartermaster John Taylor submitted his estimate of the railroad cars needed daily to supply the army during its campaign. Taylor used planning figures of 45,000 animals and 70,000 men in computing the army’s needs, with the capacity of each railroad car placed at eight tons. He expected that fodder or long forage would be procured locally, leaving only the grain or short forage to be transported by rail. Therefore the army’s animals would need 450,000 pounds of grain per day, accounting for twenty-eight railroad cars. Standard bacon-based rations for the men equaled 210,000 pounds per day, carried in thirteen cars. Quartermaster stores amounted to 160,000 pounds per day, or ten cars. Medical stores accounted for 32,000 pounds per day, filling only two cars. Finally, “Contingencies” added 112,000 pounds per day, the equivalent of seven freight cars. In total, Taylor estimated that Rosecrans’s four corps would require the Nashville & Chattanooga Railroad to deliver at the railhead an average of 964,000 pounds of supplies per day, the equivalent of sixty loaded freight cars. This quantity of supplies had to be delivered every day for the duration of the campaign. Otherwise, the army would have to operate on reduced rations for an extended period while marching over a series of mountain ranges rising at least 1,000 feet above the plain. Taylor’s estimate did not account for the army’s ammunition needs, which was the province of Capt. Horace Porter’s ordnance department, because ammunition moved in regimental wagons or the army’s 800-wagon reserve ammunition train. Even without the ammunition, the task facing the 4,000 railroad workers of the Nashville & Chattanooga was enormous. With only thirty locomotives, 350 cars, rapidly deteriorating track, and inadequate sidings, the railroad would be taxed to the utmost. It is likely that Taylor’s sixty-car per day estimate on 8 August was the reason that Rosecrans peremptorily summoned John Anderson to Winchester.17

On the same day, larger operational and political issues came into clearer focus. Responding to Rosecrans’s query, Ambrose Burnside announced that he would probably advance from Stanford, Kentucky, toward Knoxville and Loudon, Tennessee. Burnside had hoped to await the arrival of the Ninth Corps, which had not yet returned from service on the Mississippi River, but Halleck’s order to advance was peremptory. Thus Burnside could send no more than 5,000 cavalry and 7,000 infantry toward Knoxville, beginning on 11 or 12 August. Still, if Rosecrans advanced at the same time, Bragg’s and Buckner’s forces might be overwhelmed. Cheered by Burnside’s message, Rosecrans dispatched his first daily report to Washington in accord with Halleck’s directive. In a small act of defiance, he addressed the report to Adj. Gen. Lorenzo Thomas, not Halleck. Thomas, as Rosecrans was probably aware, was fully occupied with the enrollment of black troops, and had not participated in the rancorous discussions between Rosecrans and the War Department. Nevertheless, Rosecrans was following the letter of army protocol, if not the spirit, and informed Thomas, “For the information of the General-in-Chief, I report that our cavalry on the left have moved to Sparta, to attack the rebel advance there. Our forage trains are coming up, but we have not transportation enough to get our supplies up to five days ahead, until the cars lately bought arrive. No other movement of troops to-day.” The message offered no indication that an advance was imminent, but it met the requirement for a daily report. Thus, in this passive-aggressive way, Rosecrans continued to operate on a timetable of his own choosing. Coincidentally, in Washington, Lovell Rousseau and John Sanderson finally gained an audience with President Lincoln and presented the proposal to create a new mounted division for service in the theater. Lincoln directed the two officers to Secretary of War Stanton, who simply deferred the matter to Halleck. There the proposal rested, for the time being.18

On Sunday, 9 August, Rosecrans maintained his frenetic pace. Responding to Anna’s telegram announcing her safe arrival in Nashville, Rosecrans told his wife that he had heard nothing further regarding Charlotte’s condition. He then turned to army business. Unexpectedly but pleasantly received was John Anderson’s resignation. In response, Rosecrans appointed Col. William Innes as his replacement. Innes, as aggressive as he was efficient, had been lobbying hard for the position for months. He now assumed operational control of railroad activities between Nashville and the front, while at the same time retaining regimental command. Rosecrans lost no time in making new demands on him. With the need for rolling stock so acute, he instructed Innes to purchase twenty cars from the Adams Express Company to augment the barely adequate freight car pool. John Beggs remained as assistant railroad superintendent, and Rosecrans again raised the issue with him of using the Sewanee Railroad to haul supplies to Tracy City. In order to supplement the railroads, Rosecrans looked to the Tennessee River itself. Federal forces controlled the river from its mouth all the way to Muscle Shoals, Alabama, where natural obstructions prevented the passage upstream of all but the most shallow-draft vessels. Therefore Rosecrans directed Capt. Ferdinand Winslow at Nashville to seek two vessels that could pass the shoals and ascend the river to Bridgeport. Such vessels would need naval protection, so Rosecrans telegraphed Capt. Alexander Pennock, commanding the Cairo, Illinois, Naval Station, seeking the location of the Mississippi Marine Brigade. Such last-minute requests bespoke Rosecrans’s self-absorption with his problems alone, with no thought to what might be transpiring in other theaters. In like vein, he telegraphed Maj. Gen. Stephen Hurlbut, commanding the District of West Tennessee at Memphis, “Cannot you occupy Florence and so protect our flanks?” This request, sent directly to one of Grant’s subordinates, was not only cavalier and tardy but violated army protocol as well.19

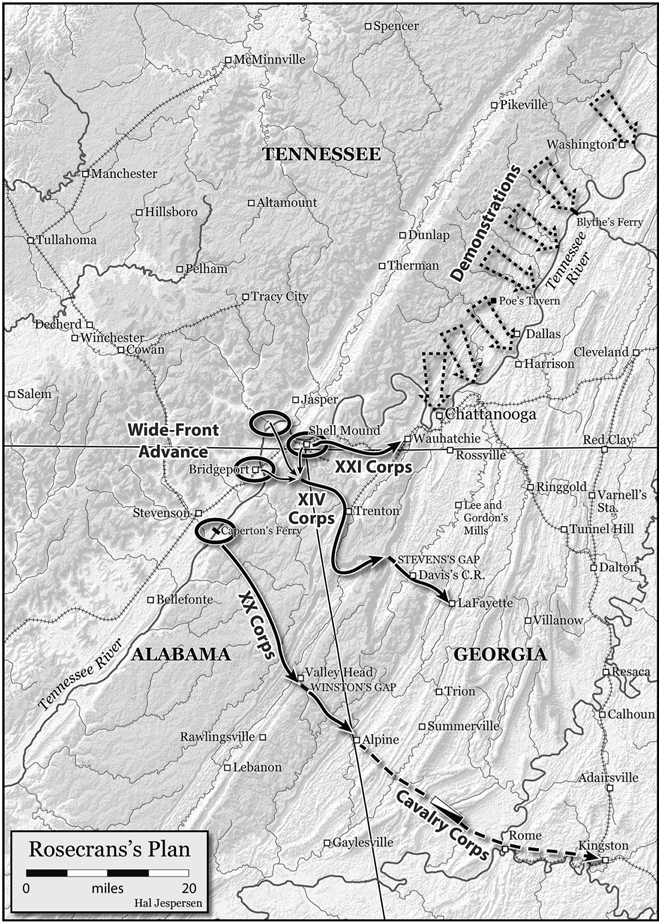

Writing to Burnside late on 9 August, Rosecrans revealed his thinking. He planned to advance one corps beyond the Cumberland Plateau into the Sequatchie Valley to confront Chattanooga directly. The remainder of his army would close on the Tennessee River around Bridgeport. Still undecided on the army’s main crossing point, Rosecrans admitted that Bridgeport looked very promising. If he chose to cross downstream, he promised Burnside that he would demonstrate in front of Chattanooga to distract the Confederates. The advance would begin on the next day but would develop slowly. Rosecrans’s remarks show that his campaign plan remained incomplete, with major decisions still pending. First, he calculated that he needed sufficient supplies to subsist his army for twenty days beyond the railhead and enough ammunition to fight two major battles. With a maximum effort, the railroad could sustain the soldiers for twenty days, but the long forage needed by the army’s animals had to be procured locally. It was imperative that the local corn crop be ripe enough to provide fodder, and that would not occur until the middle of August. The second consideration was the crossing of the Tennessee River. Rosecrans could not rely upon random small boats or makeshift rafts to make the crossing. Instead, large numbers of pontoons would have to be constructed and brought to the river by rail. The third consideration was how to deceive the Confederates as to the point of crossing. That deception could be provided through a combination of targeted misinformation and ostentatious displays. Fourth, the actual crossing point had to be selected. Finally, a scheme of maneuver would have to be implemented to gain possession of Chattanooga. By 9 August supply accumulation and pontoon construction were nearing completion, and the deception plan was ready for implementation. Rosecrans’s note to Burnside indicated that he had not yet reached a final decision on the river crossing sites, and that decision would shape the scheme of maneuver.20

As for crossing sites, Rosecrans’s most direct course of action was to force a crossing in the vicinity of Chattanooga. A few rough and steep roads led over the Cumberland Plateau and Walden’s Ridge to the Tennessee River valley directly opposite Chattanooga, with the nearest railhead at Tracy City. The Sewanee Railroad clearly could not handle the volume of traffic that the Nashville & Chattanooga Railroad provided to Stevenson and Bridgeport. Further, all intelligence sources indicated that Bragg’s army was concentrated around Chattanooga, which it was fortifying. The river crossing itself would be difficult enough without opposition and virtually impossible if attempted under the muzzles of Bragg’s guns. Burnside’s debacle at Fredericksburg graphically illustrated the problem. Logistically tenuous and tactically suicidal, the direct option received only cursory consideration before being rejected. Rosecrans’s second option was to cross the river upstream from Chattanooga. While it permitted an unopposed crossing if the deception plan worked, this option was even more difficult to sustain logistically than the direct approach. Again, both the Cumberland Plateau and Walden’s Ridge would have to be surmounted, with the nearest railhead being McMinnville, west of the mountain wall. In this option the railroad’s task was easier, but the wagon haul was more difficult, and the local forage could not sustain the army’s animals. If Rosecrans adopted this option and advanced to the vicinity of Cleveland, he might interpose between Bragg and Buckner, but he would not threaten Bragg’s supply line to Atlanta. Without that threat, Bragg could simply maneuver against Rosecrans with Chattanooga secure in his rear. If Burnside moved promptly, there might a chance for a potential merger of his and Rosecrans’s armies, with Burnside being the senior officer. If Burnside dallied, Rosecrans might find himself trapped between Bragg and Buckner, with each Confederate force being supported by rail while Rosecrans depended upon an extremely difficult wagon haul from McMinnville.21

Rosecrans’s third option was to cross at Bridgeport, downstream from Chattanooga. This option placed his railhead directly on the Tennessee River. The Sewanee Railroad could support the army’s left, as well as forces involved in the deception plan. Rosecrans’s sources indicated that a lone Confederate infantry brigade and some cavalry guarded the river around Bridgeport. A crossing there probably would face little opposition, allowing the engineers to work unimpeded. If Rosecrans could then push large forces beyond Sand and Lookout Mountains, he would seriously threaten Bragg’s lifeline to Atlanta. Such a threat would be much more likely to force Bragg to evacuate Chattanooga than an approach from the north. Any battle resulting from adoption of this option would be more likely to develop as a fight for Bragg’s supply line than one for Rosecrans’s. The initiative would belong to Rosecrans, and Bragg would have to dance to the Federal tune. Logistically, it made the best use of railroad assets and protected the Federal supply line most easily. Operationally, it offered a better chance to force the evacuation of Chattanooga without a fight than either of the other options. It did not tie Rosecrans’s movements in any way to Burnside’s, a good thing in view of Burnside’s record. It also could facilitate Burnside’s advance on Knoxville if Buckner moved to join Bragg, as Rosecrans expected him to do. The cooperation between Rosecrans’s and Burnside’s forces, so earnestly desired by the Lincoln administration, could thus be achieved without literal amalgamation. The more Rosecrans looked at the downstream option, the more promising it appeared. Still, he announced no decision. Instead, he directed all surplus supplies to McMinnville, ordered the occupation of Tracy City, and queried Sheridan about the Tennessee River at Caperton’s Ferry, near Stevenson. Even so, the steady stream of trains daily unloading supplies at Stevenson and Bridgeport created the impression that Rosecrans’s decision had been made.22

An hour before midnight, Rosecrans telegraphed his daily report of activities to Lorenzo Thomas. His only news was that Reynolds’s Fourth Division, Fourteenth Corps, had advanced to Tracy City. Rosecrans explained that he was only one day ahead of daily supply requirements, and he needed to be at least five ahead in order to cross the Cumberland Plateau. In fact, the statement that Reynolds had occupied Tracy City was literally untrue. On 9 August, none of Reynolds’s three brigades was at Tracy City. Two brigades were atop the Cumberland Plateau around University Place, and one was still in camp at Decherd. All three of the division’s units were momentarily in turmoil. Wilder’s First Brigade, at Decherd, had long been censured by Reynolds for its lax discipline, aggressive foraging, and disregard of military protocol. While Wilder had been on leave in Indiana, the straitlaced Reynolds made several ineffectual efforts to curb the brigade’s excesses. Wilder returned to duty on 9 August and resumed defending his men by cultivating Reynolds’s superiors, but the brigade remained at Decherd. The Second Brigade was commanded by Col. Edward King, who had just arrived from convalescent leave. The unit had been at University Place since 29 July. Reynolds’s Third Brigade was also experiencing command turmoil. Dissatisfied with Turchin’s performance as a cavalryman, Rosecrans had traded him for the brigade’s George Crook on 30 July. The switch was strongly favored by many soldiers, who had chafed under Crook’s strict policies against foraging, but officers like Col. Caleb Carlton of the Eighty-Ninth Ohio Infantry regiment were dismayed. Nor did they like Nadine Turchin, “not a woman of much delicacy.” Turchin and his disgruntled wife moved their new command to University Place on 1 August and encamped a mile beyond King’s troops, where they remained. Reynolds himself remained in Decherd. Thus, Rosecrans’s report to Thomas notwithstanding, the Fourth Division did not occupy Tracy City on 9 August.23

Although Rosecrans’s infantry remained quiet on 9 August, some of his horsemen were active on the army’s far left flank. At McMinnville, Van Cleve long had wanted a mounted force to patrol the mountains in his front. On 1 August Rosecrans had sent him Minty’s First Brigade of Crook’s Second Cavalry Division. Coincidentally, Forrest had sent Col. George Dibrell with his own Eighth (Thirteenth) Tennessee Cavalry regiment across the Cumberland Plateau to watch the Federals. Dibrell was from Sparta, twenty-five miles northeast of McMinnville. He occupied his own plantation in late July and began to recruit his depleted regiment while watching the Federals at McMinnville. Aware of Dibrell’s presence, the aggressive Minty had tried to surprise the Confederates on the night of 4 August by quickly overwhelming their pickets on the Caney Fork River. Although the Federals captured several pickets, others escaped to alert Dibrell. Having lost the element of surprise, Minty returned to McMinnville. Unhappy with Minty’s results, Van Cleve ordered him to try again, using a larger force of 774 troopers. Early on 9 August Minty again crossed the Caney Fork, driving the Confederate pickets through Sparta at a gallop. Warned by the noise, Dibrell delayed the charging Federals with one company and formed his regiment behind Wild Cat Creek. With his right protected by the Calfkiller River and his left covered by a millpond, Dibrell halted Minty’s charges. When Minty threatened to outflank the Confederates by sending a regiment across the Calfkiller, Dibrell withdrew his 300 troopers behind Blue Spring Creek and made another stand. Rather than press his luck, Minty elected to return to McMinnville. He admitted losing three killed and two wounded, although Dibrell claimed he killed twelve Federals. Dibrell placed his own loss at four wounded and eight captured, while Minty claimed killing fourteen and capturing ten Confederates. At the end of the day, Dibrell reoccupied Sparta, and Forrest soon reinforced him with 200 men from the Fourth Tennessee Cavalry. The Confederate observation post at Sparta remained viable.24

At the other end of the front, the friendly truce at Bridgeport remained in effect on 9 August. Except for unauthorized visits by a few bold soldiers, nothing had been exchanged except occasional newspapers and tobacco carried to midriver. Now there was to be a more formal transfer, as Margaret Bybee, mother of Patton Anderson, was to be repatriated to the Confederacy at Bridgeport in style. Rosecrans instructed assistant superintendent Beggs to place a lounge in her car before her train left Decherd on the afternoon of 8 August. She was escorted from Winchester by Lt. Col. William Ward. The train arrived at Bridgeport too late for her to be sent across the river that day, so Mrs. Bybee was the overnight guest of Ellen Sherman, wife of Col. Francis Sherman of the Eighty-Eighth Illinois Infantry regiment. After the sun banished the morning mist on 9 August, the Federals initiated a formal flag of truce procedure. Lytle assigned two staff officers to accompany the party with a bottle of champagne to commemorate the occasion. At 10:00 A.M., a boat flying a white flag ferried Mrs. Bybee, Mrs. Sherman, Lt. Col. Ward, Lytle’s two aides, and several orderlies across the river to Long Island. Awaiting them were several Confederate officers dressed in their most formal attire. While the orderlies unloaded Mrs. Bybee’s baggage, the officers of both armies toasted each other’s health with the champagne. After the ceremony, the Confederates crossed the drawbridge to the eastern bank of the river while the Federals and Ellen Sherman rowed back to the western shore. That evening at twilight Ward and a delegation from the Tenth Ohio Infantry regiment presented Lytle, their former commander, a token of their esteem. In a touching speech, Lytle accepted the gift, a solid gold Maltese cross encrusted with diamonds and an emerald, suspended from a silver shield. Then, as the shadows lengthened on the river and the music from regimental bands wafted over the valley, for a few moments at least, the war seemed far away.25

West of the Cumberland Plateau, the war was also distant, although prescient observers could see signs that the long pause was nearing its end. While Rosecrans fretted about supplies and pontoons and meddling deskbound generals in Washington, his soldiers continued the routine established six weeks earlier. Gone were the starving times of early July; for most, the railroad brought full rations daily, and local apples and peaches were ripening for the harvest. By now, all but the laziest privates had shaded their tents with cedar boughs and crafted rude furniture to make their daily existence more civilized. Capt. James Edmonds expressed the views of many: “Scenery fine, water good and everything calculated to make a soldier’s life pleasant.” Still, both the scenery and the routine were becoming monotonous, making some commanders nervous. At Tullahoma, August Willich spent early August schooling his four regiments mercilessly in the intricacies of skirmishing and maneuvering solely by the bugle. While not training as hard as Willich’s men, all regiments suffered through hours of drill at echelons from company to brigade. Most days also involved standing for long periods in formation for dress parade and inspection. The usual camp diversion of reading newspapers, magazines, books, and religious tracts was supplemented by increased letter writing, now that regular mail service was available. William Carroll advised his sister on 8 August that she did not need his permission to write to a soldier in another regiment: “I suppose you ar [sic] of age and ought to have your own way.” A letter to William Miller from his wife, Nett, informed him on 7 August that their son Rollie was dangerously ill. That night Miller wrote in his journal, “I hope the next letter will say Rollie is out of danger, if not entirely well.” Sadly, the next letter brought the worst of all possible news. Still, Miller resolved to continue doing his duty, even as he consoled his wife by mail.26

Many individuals employed more creative diversions than writing letters. Some played marbles and chess, at least one studied the German language, and still more fashioned trinkets from local granite and the cornerstone of the University of the South. One soldier sent home $50 gained from turning buttons into rings. At Winchester and Decherd, soldiers patronized photographic studios. The upwardly mobile stood for examination as prospective officers in the United States Colored Troops. Every Sunday regimental chaplains preached to large congregations, and United States Christian Commission ministers held midweek prayer meetings. Less wholesomely, more and more soldiers found themselves ensnared by the growing availability of illicit alcohol. On 5 August a court-martial convicted a captain in the Ninety-Eighth Illinois Mounted Infantry regiment of drunkenness but recommended mercy. Two days earlier, five noncommissioned officers in the Seventy-Eighth Pennsylvania Infantry regiment were reduced to the ranks for gross intoxication. In the First Kentucky Infantry regiment, not only were officers arrested but the local “picture galleries” in Manchester were shuttered. A few days later, the sutler of the Thirty-First Indiana was forced to close for selling bottles of “death and destruction.” The closure came too late, according to Lt. Jesse Connelly: “Night—the boys are on a general tight. Our company, almost to a man, is tight—some beyond going, others dancing, fiddling, and halloing. Have dispersed them twice and got all quieted down but one or two, and they will quarrel themselves to sleep.” Some regiments countered by organizing temperance meetings, but with limited success. The general indiscipline also manifested itself in petty theft and insubordinate behavior, causing some officers to respond with harsh measures. The colonel of the Eighth Kentucky Infantry regiment briefly suspended a man by his thumbs for painting his bare feet black. Believing the punishment barbaric, the man’s company commander cut him down, successfully defying the colonel.27

Throughout the area, soldiers continued to interact with civilians in their midst. The longer units remained in one place, the more civilians visited their camps, either selling produce or seeking handouts. This familiarity often bred contempt. At Bridgeport, Musician Day Elmore wrote to his parents on 9 August, “The people what few thare is left are very Ignorant.” Capt. John McGraw was contemptuous of the women he encountered at Pelham, as he told his wife: “Did I ever tell you about the ladies of this section. Well they are not very intelligent some of them passably good looking but they all of them chew tobacco.” In like vein, Cpl. Alanson Ryman wrote his wife from University Place, “Jane you should see some of the women and girls that come to our camp to trade. … They ask for the cash and then go to the sutler for tobacco cigars and all kinds of fancy things. I saw a good looking young woman to day smoking a cigar. It is very amusing to the soldiers.” Some interactions went beyond wry commentary, as Pvt. Alva Griest recounted. A civilian selling fruit made remarks the soldiers deemed unpatriotic: “As soon as we heard this our course slightly changed, his oxen were soon loose going over the hill with stones flying after them, his linchpins got out by some means and the wheels rolled down the hill, while his apples were scattered about promiscuously.” In contrast, Pvt. James Riley left camp without authorization in order to aid a dying elderly man whose family he had befriended earlier. Assisted by two Confederate soldiers, Riley prepared the body for burial. He then returned to camp to face extra duty, satisfied that his actions were justified.28

Although some soldiers tried to assure themselves that the war was winding down, the signs of an impending move grew in intensity as the August days passed. The most obvious indication was the issuing of new clothing by regimental quartermasters to replace missing or ragged items. In the 104th Illinois Infantry regiment, the men were surprised to receive slouch hats instead of the regulation kepis. The knapsacks of several regiments arrived from storage, although some were moldy and others had been robbed. Other signs that the campaign was about to open were the growing stockpiles of rations, the evacuation of sick men to Nashville hospitals, and the arrival of comrades from convalescent camps. Anyone near the tracks could see the increased tempo of railroad operations, especially the heavily loaded trains disappearing southward through the Cowan tunnel. The diary of Lt. Col. William Robinson succinctly expressed the view of many on 6 August: “No news on the front, but soon will be. Army is stirring.” The departure of several units of the First Division of the Fourteenth Corps from their Cowan camps also indicated an impending move by the remainder of the army. Scribner’s First Brigade marched over the Cumberland Plateau to Anderson Station on 6 August. There Scribner’s men relieved the remaining units of Lytle’s brigade. When the two regiments joined Lytle at Bridgeport, Sheridan’s entire division was concentrated in the Tennessee River valley for the first time. Two days later, the Second Battalion of the Eighteenth United States Infantry regiment from King’s Third Brigade departed Cowan for a new camp halfway up the mountain. From that base it initiated heavy repairs to the rough road leading over the Cumberland Plateau. In Rousseau’s absence, King normally commanded the division, but he had become ill, and division command devolved temporarily to John Starkweather of the Second Brigade. A volunteer officer, Starkweather was much preferred by some soldiers to King, who strictly enforced the Regular Army’s standards of discipline.29

Some soldiers would not be making the trip to the Tennessee River, as death continued to claim random individuals in the army’s camps. At least six men died from disease in early August, and another was dismembered when he fell under the wheels of a train. A private in the 100th Illinois Infantry regiment almost joined them when he was wounded by the negligent discharge of a weapon in camp. Collectively a small number amid a large host, the soldiers’ deaths nevertheless touched their comrades. Cpl. Alanson Ryman wrote poignantly about the death of Pvt. James Meyneke on 3 August: “I made his coffin out of rough pine boards and lined the head end of it and put in a pillow for his head to rest on. Jim was well liked by his comrades and was a good faithful soldier. I was sorry to see him die away from his friends and home but his body will rest as well on these lonely mountains as it would by the side of his father on that knoll by the hillside.” Such tragedies were compounded when a single event generated multiple fatalities. A horrendous accident occurred on 8 August in Turchin’s brigade at its camp near University Place. On that day, the Twenty-First Indiana Battery spread many of its damp powder bags on canvas tarpaulins to dry them in the sun. Through someone’s carelessness, a spark ignited ninety-six cartridges, which exploded in a massive fireball that set nearby trees ablaze. Seven soldiers suffered severe burns, with four of them eventually dying from their injuries. Several of the casualties were infantrymen detailed to the battery earlier from the Eleventh Ohio and Eighteenth Kentucky Infantry regiments. One, Pvt. Samuel Mitchell of the Eighteenth Kentucky, had both ears burned off, suffered facial scarring, and sustained major damage to his right arm and hand. Although he would live for forty-six more years, Private Mitchell’s war for the Union ended at University Place on 8 August 1863.30

Such tragic accidents did not impede the preparations for an advance. Although Garfield was sick in bed, and ordnance officer Horace Porter was absent on sick leave, the flow of orders from headquarters continued unabated. Corps commanders were admonished to maintain a five-day supply of rations and forage. Capt. Henry Thrall published Special Field Orders, No. 219, which officially appointed William Innes as military superintendent of railroads in place of the ineffectual John Anderson. The order specified Innes’s duties to be “repairing, managing, and running the railroads under his charge.” He was also empowered to set train schedules, regulate rates, and keep weekly and monthly records to be submitted to the army’s chief quartermaster. Innes retained command of the First Michigan Engineers and Mechanics regiment, as well as temporary control of the black regiment forming at Estill Springs. Having thus empowered an aggressive subordinate to improve the efficiency of his railroad operations, Rosecrans spent the remainder of the day attending a grand review of Davis’s First Division, Twentieth Corps. As the official party of Rosecrans, McCook, Davis, and Stanley watched, the brigades of Post, Carlin, and Heg passed in review. Seated in a carriage near the parade field was Kate McCook, who some soldiers took to be Mrs. Rosecrans. Afterward, Rosecrans walked among the troops, jocularly admonishing them: “You young men who wish to be corporals and sergeants must stand erect, and then you will be good looking when you get home.” According to Lt. Chesley Mosman, “I never saw a more pleasant looking man than the General.” Following the review, the official party adjourned to Davis’s headquarters for refreshment, although Post appeared to some to have gotten a head start. Upon returning to his own headquarters, Rosecrans entertained Governor Andrew Johnson and Gordon Granger, who had just arrived from Nashville.31

Even though the day was extremely hot, several brigades were in motion. With King ill, the “insane” Maj. Samuel Dawson took the remainder of King’s brigade of the First Division, Fourteenth Corps, over the mountain to Tantalon Station. There they joined the Second Battalion, Eighteenth United States Infantry, which had preceded them. The heat took its toll. Large numbers staggered behind the long column until they fell by the roadside, where they were left to follow when they could. Nor was the passage of the artillery and baggage trains any easier, as Lt. Augustus Carpenter reported: “Our artillery and transportation had a hard time in getting along. Some places the road wound along the tops of hills, right on the brink of precipices several hundred feet down, and occasionally a wagon would upset, sending its contents helter scelter [sic] down the hill.” Also marching over the mountain was the division’s Second Brigade, temporarily led by Col. Henry Hambright of the Seventy-Ninth Pennsylvania Infantry regiment while Starkweather held divisional command. Hambright’s men also suffered under the extreme heat, but their volunteer officers sensibly mitigated their discomfort, unlike the regular officers. The First Division’s departure from Cowan freed numerous campsites for other units, notably Stanley’s Second Brigade of Negley’s Second Division. Stanley’s men marched six miles from Decherd to Cowan during the heat of the day, generating even more stragglers. Rosecrans reported all of these movements to Lorenzo Thomas in his nightly summary. He embellished the report by claiming that Negley’s entire division had moved to Cowan, and touted the inconclusive fight at Sparta as a significant victory. He also announced that he would be sending a cavalry division to the Tennessee River valley in the near future to protect the Memphis & Charleston Railroad. Beyond that, Rosecrans was still waiting to accumulate sufficient forage to move the remainder of the army over the Cumberland Plateau.32

On 11 August, Rosecrans continued to push his staff at a frenetic pace. He bombarded William Innes with peremptory orders: repair the locomotive that assisted trains up the Cowan grade; borrow cars from the Louisville & Nashville Railroad; acquire the Adams Express Company cars. Capt. James Drouillard worked with assistant superintendent Beggs to transport Governor Johnson to Fayetteville. Maj. Frank Bond instructed John Palmer, still commanding the Twenty-First Corps, to evacuate all sick soldiers from his First and Second Divisions to Nashville. Van Cleve’s Third Division was to retain its sick at McMinnville until further notice. Capt. Henry Thrall issued Special Field Orders, No. 220, which relieved James Steedman from his brigade in the Third Division, Fourteenth Corps, and assigned him to command the Reserve Corps division formerly led by Absalom Baird. Baird himself was sent to Thomas’s Fourteenth Corps for assignment. Both Thrall and Drouillard wired absent staff officers Calvin Goddard and Henry Hodges, recalling them from leave. Capt. Robert Thoms expedited the movement of tools to Stevenson. Finally, Capt. Charles Thompson asked a Louisville Associated Press agent for Burnside’s address. Rosecrans himself spent the afternoon reviewing Brannan’s Third Division, Fourteenth Corps, at Decherd. He had not reviewed the command before, so his familiar banter played well with most of the men. Pvt. James Thomas later enthused in a letter home, “I think he sertonley is the best man on erth now. … Washington might have bin as good but he was no better than old rosey. … I tell you the boys will fight for him to the last.” Officers tended to see Rosecrans’s performance differently. Lt. Jeremiah Donahower grumbled about the amount of marching on a hot day, while Capt. Everett Abbott was unimpressed: “Rosecrans very pleasant. Not a great man. He seems governed by sense of religious duty more than any officer I know of.” Afterward, the official party, which again included McCook, Stanley, and Davis, visited Brannan’s headquarters for liquid refreshments.33

While Brannan’s men sweated on the review field at Decherd, the two brigades of the First Division, Fourteenth Corps, resumed their march along the railroad from Tantalon Station. They crossed the state line into Alabama during the heat of the day, and camped several miles beyond Anderson in the Crow Creek valley. The march was even more difficult than the previous day’s had been. At Estill Springs a member of the First Michigan Engineers and Mechanics recorded the temperature as 108 degrees in the shade, and it could hardly have been less around Anderson Station. Again, many of the toiling soldiers fell out of line, some with dangerous cases of sunstroke. Both Hambright’s Second Brigade and Dawson’s Third Brigade temporarily lost hundreds of men to straggling. Rumors spread that several men in the First Battalion, Sixteenth United States Infantry regiment had died from sunstroke, although regimental returns list no such deaths. The men of Scribner’s First Brigade, camped at Anderson Station since 6 August, watched with pity as their fellow soldiers staggered past them. By the end of the day, the First Division was finally united east of the Cumberland Plateau but, to one regular officer, the march was “harder than there was any necessity for.” Still, the scenery was beautiful, and hundreds of acres of ripening corn carpeted the valley floor. Also moving on 11 August was Mitchell’s First Cavalry Division. Commanded by Col. Edward McCook because Mitchell was absent sick, the division marched from Fayetteville toward Huntsville to secure the line of the Memphis & Charleston Railroad. At McMinnville, several of Van Cleve’s regiments began the construction of a protective earthwork. At Bridgeport and Stevenson, Sheridan’s brigades issued extra pairs of shoes and rations for ten days. At Decherd, one of Alex McCook’s orderlies was killed by the daily passenger train when his horse threw him into the engine’s path. In his nightly report to Lorenzo Thomas, Rosecrans noted only the departure of McCook’s cavalrymen.34

On the next day, 12 August, Rosecrans continued to make demands upon his railroad operators. With the army’s forage stocks still insufficient to permit it to cross the Cumberland Plateau, the need for additional freight cars was acute. The immediate requirement was for boxcars, which had prompted the purchase of fifty such cars and an effort to buy twenty cars belonging to the Adams Express Company. In a series of telegrams to the increasingly harassed Innes, staff officers pressed for the acquisition of the Adams equipment. Only when the Adams Company pushed back did army headquarters look elsewhere for cars. Not only boxcars were needed; the pontoons constructed by army engineers would need transportation to Stevenson by flatcar. Rosecrans estimated that thirty-five flatcars would be required, and his staff pressed Innes to provide them. When Innes disregarded multiple queries about the number of cars in inventory, he was pointedly reminded that Rosecrans expected a “full and prompt answer.” This was the kind of behavior that had gotten John Anderson in trouble and was an early sign that Innes’s relationship with Rosecrans would not be smooth. At Nashville, Capt. Simon Perkins Jr. somehow managed to find enough cars to fill the largest requisition of the summer on 12 August. Sent the previous evening, the order required fifteen carloads to be dispatched to McMinnville, twenty to Tullahoma, ten to Winchester, six to Murfreesboro and Wartrace, and an unspecified number to Decherd. Perkins was admonished, “The Supply for tomorrow must not fail.” The efficient Perkins met the requirement, only to be assigned to other duties a few days later. Unfortunately, there was no relief for the equally efficient John Beggs at Decherd. He was directed to make the dummy available at 8:00 A.M. on the following day to take Governor Johnson and Gordon Granger to Fayetteville. He was further called to account for the nonarrival of the daily passenger train from Nashville, delayed because of a problem with the bridge over Stones River at Murfreesboro.35

While his staff harassed the railroad managers, Rosecrans himself initiated a telegraphic conversation with Ambrose Burnside. Having discovered that Burnside had reached Camp Nelson in central Kentucky, Rosecrans sought to learn how his plans to attack Knoxville were progressing. Burnside responded that he had been waiting to hear from Rosecrans again before committing his troops to the advance. He offered to accelerate his own timetable, should Rosecrans desire it. Unwilling to commit to a definite time for his own advance and perhaps still unsure of its exact direction, Rosecrans responded vaguely. He did promise that his army would reach (but not cross) the Tennessee River by the time Burnside arrived at Kingston, Tennessee, and closed, “Will keep you advised, and hope to hear from you often.” Clearly, Rosecrans expected little from the Department of the Ohio and did not intend to link his own campaign to Burnside’s. Halleck and Lincoln had expected Burnside and Rosecrans to collaborate in the liberation of the long-suffering Unionists of East Tennessee. By occasionally offering Burnside vague promises of general support, Rosecrans fulfilled the letter of his orders but hardly the spirit. Rosecrans did not believe he needed Burnside to capture Chattanooga. If Burnside could aid that endeavor, Rosecrans would welcome it, but if not, the Army of the Cumberland would act alone. Rosecrans’s most current intelligence reports indicated correctly that Bragg’s two infantry corps lay at Chattanooga and just upstream. To Rosecrans that meant that Bragg expected an attack above the city rather than below. If Burnside’s pending advance contributed to that Confederate perception, so much the better for Rosecrans’s operations. For his part, Burnside was so overwhelmed by the absence of his Ninth Corps and his own logistical problems that he gave little thought to Rosecrans’s movements or how they might affect his own operations.36

On Wednesday, 12 August, the thermometer registered only ninety-four degrees at Decherd, and an afternoon thundershower drenched the camps west of the Cumberland Plateau. In the Second Division of the Fourteenth Corps, a portion of the Second Brigade climbed the mountain from its camp at Cowan, driving a herd of 600 cattle to Tantalon Station. At Winchester, Sgt. Peter Keegan encountered Governor Andrew Johnson: “The Gov. invited me to drink with him which I declined, the Gov. ‘indulges’ himself somewhat freely if his countenance is any indication. For a man of his age, he looks quite fresh & vigorous.” Gordon Granger also remained in Winchester and met at length with Alex McCook. Kate McCook was present too, hoping to remain until her husband’s corps crossed the mountain. In the First Brigade of Davis’s First Division, Lt. Cyrenius Woods died of disease. At Pelham the Ninety-Seventh Ohio Infantry regiment received a new regimental flag from the ladies of Coshocton, Ohio. On the army’s far left flank at McMinnville, three regiments from Van Cleve’s Third Division grumbled as they continued building a defensive earthwork. At Tullahoma, August Willich scolded the Forty-Ninth Ohio Infantry regiment on its rowdy behavior. In the rear, most of the First Brigade of the First Division, Reserve Corps, left Wartrace and headed for Estill Springs. Two regiments of the Second Brigade moved from Shelbyville to Wartrace to take their place. At Nashville, virtually all of the Second Brigade of the Second Division, Reserve Corps, attended the funeral of Col. David Irons of the Eighty-Sixth Illinois Infantry regiment, another victim of disease. At University Place, soldiers continued crafting souvenirs from local granite, and Nadine Turchin ranted in her diary against West Pointers. At Bridgeport, Sheridan’s men reduced their baggage and packed their knapsacks for a movement. Edward McCook’s First Cavalry Division reached Huntsville. Hearing nothing from McCook, Rosecrans reported to Lorenzo Thomas that night only the consolidation of Starkweather’s division near Stevenson and the familiar complaint about lack of forage.37

The next day brought some respite to staff officers and railroad managers alike. William Innes received only one message from headquarters, an order to activate sawmills at Anderson Station to stockpile bridge timbers. Several messages indicated that Rosecrans was seeking alternate pathways over the Cumberland Plateau other than the one leading from Cowan to Anderson. Capt. Robert Thoms queried Thomas about progress in improving the road down the mountain into the valley of Battle Creek. He also instructed Palmer, still commanding the Twenty-First Corps, to open another pathway over the Cumberland Plateau from Pelham. The small amount of headquarters business indicates that Rosecrans was otherwise engaged. Indeed, a special run of the dummy was made on 13 August to carry Governor Johnson, Gordon Granger, and probably Rosecrans to Fayetteville and back to Winchester. Johnson desired to survey Unionist sentiment in the area, but Rosecrans was so unsure of their welcome that he ordered a cavalry regiment to deploy along the railroad. As the cavalrymen patrolled the tracks, they were almost fired upon by the train guard, which had not been informed of their presence. Fortunately, no damage was done, Governor Johnson’s party visited Fayetteville as planned, and all returned to Winchester safely. Back at his headquarters, Rosecrans found a message from Burnside and another from Stephen Hurlbut at Memphis. Responding to Rosecrans’s request for a demonstration, the Memphis District commander claimed that the addition of Arkansas to his area of responsibility prevented him from assisting the Army of the Cumberland. Instead, Hurlbut brazenly asked Rosecrans to support him with 3,000 cavalry. Nor was there much comfort in Burnside’s telegram. He offered 15 August as a tentative date for beginning his own advance, but his units remained widely scattered over central Kentucky. Burnside again promised hearty cooperation with the Army of the Cumberland, but the lack of conviction in his pronouncements was obvious.38

The heat that had baked the army’s camps continued unabated on 13 August until a strong and widespread afternoon thunderstorm broke the spell. While some units reported only minor showers, the two brigades of Wood’s First Division, Twenty-First Corps, at Hillsboro took the full brunt of the storm. Not only did the pouring rain drench everything, but strong winds also tore through the regimental camps, blowing down tents and uprooting trees. Men in the Sixty-Fourth Ohio Infantry regiment had sheltered their tents under large trees, which crashed down upon them, injuring several men severely. Still, the work of preparing the army for its advance had to continue. East of the Cumberland Plateau, near Tantalon, the Eighteenth Ohio Infantry regiment struggled to improve the still rough road over the mountain to Cowan. In the army’s rear, Thomas Champion’s brigade completed its march from Wartrace to Estill Springs. Farther in the rear, two regiments of William Reid’s Second Brigade of what was now James Steedman’s First Division, Reserve Corps, settled into the abandoned camps at Wartrace. These small movements represented a further coiling of the spring represented by the army as it readied itself for the grand push across the mountains to the Tennessee River valley. Edward McCook’s First Cavalry Division was already in that valley, and on 13 August it advanced eastward beyond Huntsville. Following the line of the Memphis & Charleston Railroad to Brownsboro through delightful mountain scenery, the division scoured the hills for guerrillas, capturing one and killing him when he tried to escape. In his nightly message to Washington, Rosecrans highlighted McCook’s advance, the roadwork being done on the Cumberland Plateau, and his plan to send the Twenty-First Corps to Tracy City on the following day. Again, Rosecrans oversold the day’s events. In fact, fewer men were engaged in roadwork than Rosecrans indicated, and Palmer’s Twenty-First Corps would not advance to Tracy City on the next day. Nevertheless, a sense of forward movement was communicated, and that was all that seemed to matter in Washington.39