8

TO THE RIVER

» 15–20 AUGUST 1863 «

News of the destruction of the Bridgeport drawbridge reached Winchester, Tennessee, before daylight on the morning of 15 August. If Rosecrans had been waiting to gather a few more days of supplies, he now had reason to initiate the movement at once. Needing more information about what was happening on the Confederate side of the river, he instructed Sheridan and Lytle at Bridgeport to be especially vigilant. During the previous evening, before the bridge fell, Sheridan had brashly suggested that the Confederates might be evacuating Chattanooga. Now Rosecrans wanted to know if there were any other signs that Anderson’s men were leaving, such as changes in the appearance of their campfires. No matter what Lytle discovered, Rosecrans informed Sheridan that the entire army would move east of the Cumberland Plateau on the next day. Rosecrans had never liked to conduct operations on Sunday, but the situation had become too unstable to keep the army in its camps, so the advance would begin the next day, Sunday, 16 August. In order for that to happen, the army staff was galvanized into action. With Garfield still ill, Calvin Goddard and his assistants, Maj. William McMichael and Capt. Henry Thrall, initiated drafting, editing, and proofreading two General Orders regarding the treatment of guerrillas and rules for foraging, as well as the all-important movement order for the army’s major components. The final draft of the order would not be ready for publication until late in the afternoon, although news of its coming soon began to spread around the army.1

While the adjutant general department crafted the movement order, two of Rosecrans’s aides-de-camp, Frank Bond and Robert Thoms, scurried to do Rosecrans’s bidding on a variety of other subjects. First, Bond telegraphed Sheridan, ordering the manufacture of large numbers of oars for the pontoons building at Estill Springs. He also wrote in Rosecrans’s name to James Guthrie, president of the Louisville & Nashville Railroad, seeking the temporary loan of several locomotives and cars. Both Bond and Thoms then wired Innes and Capt. Jonathan Dickson in Nashville on the car issue. Innes had wanted to send two officers north to purchase additional freight cars, a request now denied because 100 had already been ordered. In contrast, Innes was permitted to detail an officer to unload cars arriving by steamboat from other commands, notably Grant’s. At Rosecrans’s behest, Thoms also dispatched several interrogatories: to the commander of the Pioneer Brigade, can you spare 100 panniers for headquarters use; to George Thomas, how is Reynolds’s work on the Doran Cove road down the Cumberland Plateau progressing; to Richard Johnson at Tullahoma, have Reserve Corps units arrived to relieve your division; to Samuel Simmons, the army’s chief commissary of subsistence, must the Twentieth Corps go on half rations of sugar; and, to Capt. Edwin Townsend, ordnance officer at Nashville, can you provide arms and equipment for two regiments of black troops. In the midst of this flurry of frenetic activity, Rosecrans himself found the time to upbraid Colonel Innes for usurping the prerogatives of the army’s chief telegrapher, John Van Duzer, and to wire Secretary of War Stanton for $10,000 with which to pay secret agents. He also wrote a note to the Democratic State Central Committee of Ohio, stating that although he was a Democrat and favored soldiers’ casting ballots, he would not permit “stump orators and canvassers” to visit the army prior to the upcoming elections. He apparently gave no thought to how the note, which found its way to the newspapers, would be received by the Lincoln administration.2

Lieutenant Colonel Goddard’s handiwork consisted of eight distinct parts. It opened with instructions to George Thomas and the Fourteenth Corps. Thomas was to move his First and Second Divisions to positions just north of Stevenson, while the Third and Fourth Divisions were to cross the Cumberland Plateau into the Sequatchie and Battle Creek valleys, north of Battle Creek itself and near the village of Jasper. The divisions were to carry with them their reserve ammunition, eight days’ rations and at least five days’ forage. One regiment was to be left at Cowan to guard the depot, the railroad tunnel, and the sick of the corps until they could be evacuated to Nashville. Another regiment was to be left at Tracy City to guard the supply depot to be established there. Thomas’s two divisions near Battle Creek were to draw their supplies from Tracy City, while the others were to get their rations from Stevenson. Thomas was to maintain communication between his wings by both courier and signal corps personnel, and his staff officers were authorized to communicate their needs directly to the army’s staff department heads. One of Thomas’s units, John Wilder’s First Brigade of Reynolds’s Fourth Division, was assigned a special mission. Wilder, who would receive instructions directly from Rosecrans, was to lead his “Lightning Brigade” of mounted infantry to the Tennessee River at Chattanooga and Harrison and make demonstrations there. The corps was to begin its advance on the next morning. As befitting instructions to the army’s senior corps commander, the order was succinct, giving general guidance only and leaving the specific details of route and troop placement entirely to Thomas’s discretion.3

In contrast to the latitude given Thomas, Section 2 of the operations order gave minute instructions to Thomas Crittenden. Each of Crittenden’s divisions was to take a different path across the Cumberland Plateau. Wood’s First Division was to cross the mountain beyond Pelham and occupy a road junction called Therman in the Sequatchie Valley, five miles south of Dunlap. The order required Wood to carry ten days’ rations and eight days’ short forage. On Wood’s left, Palmer’s Second Division was to move from Manchester beyond the Cumberland Plateau to Dunlap, using the route through Irving College. North of Palmer, Van Cleve was ordered to take two brigades and Minty’s cavalry across the plateau and enter the Sequatchie Valley at Pikeville. Minty was to move via Sparta, while the infantry and two cavalry battalions took a more southerly route via Spencer. Van Cleve was to leave an infantry brigade at McMinnville and a cavalry battalion at Sparta to protect the army’s left flank. The order required all Twenty-First Corps units to be in the Sequatchie Valley by the night of 18 August. Upon reaching Pikeville, Van Cleve was to send a strong cavalry probe beyond Walden’s Ridge into the Tennessee River valley near Blythe’s Ferry and Washington. Palmer was to send an infantry brigade into the same valley at Poe’s Tavern, where it would support Wilder’s demonstrations. Finally, Wood was to send an infantry brigade to the eastern edge of Walden’s Ridge, in plain view of Chattanooga. In each case, the advance parties were to act with “a show of modest concealment, indicating strength.” If the Confederates moved against them, the brigades should protect themselves; if the Confederates simply reinforced their units east of the river, the brigades should push scouts forward; and if the Confederates disappeared, the brigades should advance to the river and attempt to cross the stream. Finally, the army order specified that each division of the Twenty-First Corps should divide its trains into three sections to bring supplies from the McMinnville and Tracy City depots.4

Sections 3 and 4 of the operations order addressed Alexander McCook’s Twentieth Corps and David Stanley’s Cavalry Corps. With Sheridan’s Third Division already deployed at Stevenson and Bridgeport, the order to McCook only addressed his remaining divisions. Johnson’s Second Division was ordered to leave Tullahoma and cross the Cumberland Plateau into the Tennessee River valley by a route that would take it near Bellefonte, Alabama. There it would establish itself in a concealed position near the Memphis & Charleston Railroad and open communication with corps headquarters at Stevenson by the night of 19 August. At the same time, Davis’s First Division was to march from Winchester over the Cumberland Plateau and also enter the Tennessee River valley, but nearer Stevenson than Johnson’s troops. Davis was also to camp on the Memphis & Charleston Railroad, but nearer Stevenson between Mud and Raccoon Creeks. He was to be in position by 20 August. As for the army’s cavalry, Stanley’s First Division, temporarily under Edward McCook, was already dispersed along the Memphis & Charleston Railroad from Stevenson west to Maysville, guarding major bridges and picketing the Tennessee River. Crook’s Second Division, only two brigades strong, was split. Minty’s First Brigade was with Van Cleve, on the army’s far northern flank, while Long’s Second Brigade was to remain in support of army headquarters and move forward with it. Stanley himself was to move with Long and be governed by further instructions from Rosecrans himself.5

Sections 5 and 6 delineated the role of Gordon Granger’s Reserve Corps. Granger’s charter to guard the rear areas of the Army of the Cumberland remained in effect. Specifically, he was to advance to Fayetteville to protect the supply depot vacated by Stanley’s cavalry, push a two-brigade force southward to Athens, Alabama, and give the impression that 25,000 men would be advancing on Decatur. These moves, if fully implemented, would protect the far right flank of the Army of the Cumberland. Granger’s easternmost unit was a brigade of Unionist Tennessee troops stationed at Carthage, Tennessee, forty-five miles east of Nashville on the Cumberland River. The army operations order required that brigade, minus one regiment, to move seventeen miles south to Alexandria, Tennessee. From there, the command would open communication with the troops Van Cleve had left at McMinnville when his division advanced into the Sequatchie Valley. When circumstances permitted, this force would relieve the McMinnville garrison, permitting Van Cleve’s Second Brigade to join its parent unit. To facilitate communications, as the units moved farther from Nashville, a new telegraph line would be built from Gallatin, Tennessee, to Carthage. Elements of Granger’s corps therefore would protect the left flank of the Army of the Cumberland as well as its right. Beyond that, Granger was free to deploy the units of his corps as he saw fit. He remained responsible for the safety of the Nashville depot and the army’s lines of communication in Tennessee. Those lines included the Cumberland River garrisons at Fort Donelson and Clarksville, Tennessee, as well as the critical Louisville & Nashville and Nashville & Chattanooga Railroads, with garrisons at Murfreesboro and points south. Thus his command was now more widely spread than ever before, and as the main army moved forward the Reserve Corps it would be stretched even farther.6

Section 7 of the army operations order addressed logistics. There would be three depots of supplies: Stevenson, Tracy City, and McMinnville, with Stevenson the largest. All three depended upon railroad transportation to provide the requisite amount of food, short forage, equipment, and medical supplies. The easiest location to supply was Stevenson, situated on the main line of the Nashville & Chattanooga Railroad. The primary challenge on that route was the steep grade on both sides of the Cumberland Tunnel. Details from the Pioneer Brigade had been at work for some time on platforms at Stevenson to keep the massive numbers of boxes, barrels, and kegs out of the mud when it rained. The Right Wing of the Fourteenth Corps, the entire Twentieth Corps, all of the Cavalry Corps except Minty’s brigade, the Pioneer Brigade, and army headquarters would all be sustained from Stevenson. Much more problematic was the selection of Tracy City as a supply depot. That coal mining settlement lay at the end of the extremely steep and curving track of the Sewanee Railroad. By the time the operations order was issued, Tracy City was unoccupied by troops, and no supplies had been accumulated there. Rosecrans’s long-standing concerns about getting the right kind of engines to traverse the line successfully had also not yet borne fruit. The situation was somewhat better at McMinnville, where the McMinnville & Manchester Railroad ran thirty-seven miles to a junction with the main line of the Nashville & Chattanooga Railroad at Tullahoma. Despite poor track and several large trestles, the railroad had been able to support a supply depot at McMinnville for several weeks. No matter how difficult the Tracy City and McMinnville branches were to operate, depots at those villages were expected to sustain the Left Wing of the Fourteenth Corps, the entire Twenty-First Corps, and Minty’s cavalry brigade. As for army headquarters, it was scheduled to move to Stevenson on Tuesday, 18 August.7

Although it did not articulate a general concept of the army’s forthcoming campaign, the operations order of 15 August signaled that Rosecrans had finally decided how to proceed. The detailed instructions to Crittenden’s Twenty-First Corps and the more vaguely worded mention of Wilder’s expedition clearly showed that the army would implement its deception plan at Chattanooga and upstream, not below the city where troops were instructed to remain completely hidden. Of course, if the deception units discovered that the Confederates were withdrawing, as Sheridan expected them to do, the plan could be adjusted. Nevertheless, the order gave no indication that such was an active possibility. Given the vertical and unforgiving terrain opposite Chattanooga and northward, the location of the Nashville & Chattanooga Railroad, and the difficulty of moving heavy pontoons secretly over multiple mountains in order to reach the river anywhere but near Stevenson, it would appear that Rosecrans had no other rational course of action available to him. Perhaps Rosecrans had known this truth all along and had simply maintained the fiction of multiple avenues of approach with Burnside and others for security reasons when he seemingly left other options open for consideration. It is also possible that he came to his choice through a rational weighing of all of the options before him, as would be expected of a mind of logical and scientific bent. However he reached the final decision, Rosecrans had now produced a detailed operations order for the Army of the Cumberland. Whether he came to adopt the plan rationally or impetuously, his timing in its issuance bore the marks of unseemly haste. The fact that Rosecrans committed the army to a highly unusual Sunday advance, the universal surprise expressed by all echelons, and the resulting chaos at army headquarters all lead to the conclusion that Bragg’s unexpected destruction of the Bridgeport drawbridge caused Rosecrans to advance his movement schedule by at least a day, if not more.8

As the army staff frantically crafted the operations order, Rosecrans’s soldiers blissfully enjoyed a quiet Sunday in camp. Across the army the usual inspections and dress parades took place, as did normal details for picket duty. Those not so engaged received mail from home, wrote letters, washed their clothes, and relaxed. At Manchester, Thomas Prickett of the Ninth Indiana wrote to “Dear Matilda” about the disgusting predilection of Southern women to chew tobacco. At Cowan, artilleryman Eben Sturges Jr. continued his study of the German language. At Tullahoma, August Willich maintained his strict schedule of daily drill. At University Place, the last injured soldier from the 7 August gunpowder explosion finally succumbed. At Decherd, men of the 101st Indiana spent the day cleaning their camp. At Pelham, the Ninety-Seventh Ohio completed work on a road leading up the Cumberland Plateau. At Wartrace, a detail from the 113th Ohio languidly guarded a herd of draft animals. Nor was there greater activity at the front. At Bridgeport, men from the Forty-Second Illinois swam in the Tennessee River, even as smoke continued to rise from the burned drawbridge beyond Long Island. Only a few units were in motion. Having completed their road repair tasks on the plateau, two Fourteenth Corps regiments marched down the mountain to Anderson Station. In the Tennessee River valley, the Ninth Pennsylvania Cavalry moved from Larkinsville to Stevenson, escorting the division commander, Edward McCook. Virtually everyone believed that the campaign would begin soon, but they had no inkling that the operations order even then was being prepared. The day was hot and humid, and around 3:00 P.M. a large thunderstorm developed that both stopped activity and cooled the air. Again, the storm struck most heavily in the camps around Decherd. Dangerous lightning strikes drove the Seventeenth Ohio into an open field for safety, and the tents and bowers of the Tenth Indiana were scattered far and wide. The storm eventually climbed the mountain to University Place, wetting the bivouacs of Edward King’s brigade before dissipating.9

At the Mary Sharp College in Winchester, a storm of a different kind was brewing. The lengthy operations order not only had to be drafted and proofread, but it also had to be copied multiple times, at least one copy for every major element of the army plus file copies for headquarters. Thomas, McCook, Stanley, and Garfield were nearby and could receive their copies either in person or by courier. Crittenden, however, had only reached Twenty-First Corps headquarters at Manchester on the previous evening. The operations order was too sensitive to be sent by telegraph, and a courier would take too long to arrive by horseback. Rosecrans therefore called for the dummy to carry the operations order to Crittenden’s headquarters. When John Beggs was told to send the dummy to Winchester, he replied that Colonel Innes had sent it elsewhere. Wherever the dummy was, it was not available either at Decherd or Winchester. Upon hearing the news, Rosecrans flew into a rage. He dispatched a blistering telegram to Innes: “It seems that one of the 1st acts of your administration has been to take the dummy ordered here for my use away without my consent or knowledge. Now she is wanted to bear dispatches. Such a thing must be amply explained and never again occur while you serve in my command.” Beggs also received a telegram from Frank Bond, in which the aide accused Innes of a “very great impropriety,” established new rules for the use of the dummy, and demanded that a train be sent to Winchester at once to take the operations order to Crittenden. Even after all the harsh words, Beggs was slow to get the train to Winchester, causing aide Charles Thompson at 9:15 P.M. to demand an explanation for the delay. In order to prevent the Twenty-First Corps from missing the start time completely, Bond and another aide, Robert Thoms, telegraphed guarded messages to Crittenden and Van Cleve that generally outlined the roles they were to play. Having vented his spleen, Rosecrans reported to Adjutant General Thomas that the army would begin its advance in the morning.10

The Fourteenth Corps received the operations order at midnight, 15–16 August. Fortunately, the corps was already partially in compliance with the order because the three brigades of Rousseau’s First Division had been east of the Cumberland Plateau for several days. Temporarily led by John Starkweather, the division was settled comfortably in camps in the Crow Creek valley stretching east from Anderson Station for several miles. Likewise, half of Stanley’s Second Brigade of Negley’s Second Division was also at Anderson Station. Thus, fourteen of the twenty-four regiments that constituted the corps’ Right Wing were already in the Crow Creek valley. Nevertheless, the remaining ten regiments and three batteries of Negley’s command had to abandon their camps at Decherd in great haste to comply with the army and corps directives. First to move was Sirwell’s Third Brigade. Sirwell started early, with his rearguard marching at 9:30 A.M. The route led first to Cowan, reached in early afternoon despite a heavy rain that began around noon. From Cowan the rough road led steeply up the mountain. On top of the plateau it passed over the railroad tunnel several hundred feet below. Although the road was difficult, Sirwell’s brigade reached the top of the plateau after dark and halted for the night. Behind Sirwell came Beatty’s First Brigade, led in Beatty’s absence by Col. Absalom Moore of the 104th Illinois Infantry regiment. By the time the First Brigade began its journey, the rain had begun. Traveling behind Sirwell’s command on an increasingly deteriorated road, Moore’s men periodically halted because teams stalled in front of them. By nightfall, with the brigade still short of the crest, Moore decided to camp on the mountainside until the next day. Behind Moore’s tired and wet men, the remaining regiments of Stanley’s Second Brigade did not even try to advance. In accord with instructions to leave a unit at Cowan to guard the convalescent camp there, Stanley’s Sixty-Ninth Ohio Infantry left the brigade at that point.11

Unlike his Right Wing, Thomas’s Left Wing was decidedly in trouble. Reynolds’s Fourth Division already had its Second and Third Brigades on the mountain at University Place, but Wilder’s First Brigade and division headquarters were still at Decherd. Reynolds acknowledged receipt of the order at 4:30 A.M., promising to move promptly, but two factors complicated his efforts. First, Wilder had to visit Thomas’s headquarters in Decherd to meet with Rosecrans, Thomas, and Reynolds. There he was given explicit instructions regarding the demonstration he was to make in front of Chattanooga later in the week. His mission made Wilder independent of Reynolds, an arrangement no doubt pleasing to all concerned. Second, Thomas ordered Reynolds to supervise the movements of Brannan’s Third Division in addition to his own. Brannan had just gained division command in April, and his only experience in directing its movements had been in the brief Tullahoma campaign. Although Reynolds himself did not have a strong reputation at army headquarters, he had commanded a division since late 1862. Both men had very limited combat experience. Their route was an extremely rough road from the valley floor at Brakefield Point to University Place, thence down into Sweeden’s Cove. Wilder’s leading regiment, the Seventy-Second Indiana Mounted Infantry, made it up the mountain with ease, but the remainder of the brigade was caught in a heavy downpour as it began the ascent. Lightning flashed around the toiling column, some bolts so near that they drove men to their knees, their skin tingling. The torrent soon began to wash down the hillside, making the rocky road slippery. In the recently mounted Ninety-Second Illinois regiment, soldiers and unsecured gear fell into the muck, paving the road with “frying pans, coffee pots, knives, forks, spoons, bacon, hardtack, and poor riders.” Eventually Wilder’s troopers reached the crest, where they were above the storm. Unfortunately, the brigade train failed to complete the climb by nightfall, stalling the division train as well. Behind Reynolds’s wagons waited Brannan’s division.12

Brannan apparently was late in getting the order to march. Still, the pickets were recalled and everything packed for movement within a very short time. In Van Derveer’s Third Brigade, the Second Minnesota had built an elaborate palisaded camp, with ornamental arches and towers over its gates. When all had departed the three-acre enclosure, a detail burned their handiwork to the ground. The regiment then joined the remainder of the division heading first to Decherd, then north toward Brakefield Point. As it happened, Brannan’s men were on the road less than an hour before the violent thunderstorm that would drench so many other units struck them in full fury. The epicenter of the storm seems to have been Decherd, although it was felt over a far wider area. The blinding flashes of lightning and the tremendous peals of thunder brought all movement to a halt. In Connell’s First Brigade, Col. Morton Hunter of the Eighty-Second Indiana Infantry regiment ordered his command to fix bayonets, stick their reversed guns into the ground, and move away from their weapons for safety. Several men in the division were struck by lightning and others were injured when a bolt exploded a battery’s ammunition chest. Everywhere men donned their rubber ponchos, turned their backs to the storm, and stood the pounding rain and wind as best they could. The heaviest blows lasted thirty minutes, but the rain continued for two hours until the sun reappeared. By that time, the damage had been done. Although the temperature was noticeably cooler, the roads had become muddy streams that made travel extremely disagreeable. Brannan’s division resumed its march, but four miles beyond Decherd it halted behind the trains of Reynolds’s command. If Brannan was to follow Reynolds up the Cumberland Plateau, he would have to wait until the Brakefield Point road was clear. Thus Brannan’s weary division bivouacked in the sodden fields a few miles north of Decherd. The only consolation to the men was that they halted in the midst of unplundered fields of green corn.13

Nine miles north of Thomas’s stalled Left Wing was Thomas Wood’s First Division of the Twenty-First Corps. Wagner’s Second Brigade lay at Pelham, four miles from the foot of the Cumberland Plateau. Two infantry brigades and the division headquarters were at Hillsboro, nine miles northwest of Pelham. Wood received his movement orders at dawn, but by the time regimental commanders got the word, it was midmorning. While the troops packed their gear, Wood chose an obscure track called the Park Road for the division’s ascent of the plateau. Tramping through the humid countryside, Wagner’s regiments reached the foot of the mountain by noon. At that moment the rain sweeping toward them from the northwest arrived in strength. Although the storm in Wood’s sector did not have the violence seen at Decherd, the hard rain affected Wood’s movements just as it did those of the Fourteenth Corps. The road in the valley quickly turned to mud behind Wagner, while his own brigade could get little traction on the wet rocks of the steep Park Road. In order to prevent his wagons from stalling on the grade, Wagner ordered the teams to be doubled. By sundown only half of Wagner’s train had reached the top of the plateau. Knowing that he was delaying the remainder of the division, Wagner ordered fires to be kindled along the road. By that faint and flickering light, regimental details took the doubled teams down the mountain, and dragged the remaining wagons up the slippery road. They did not complete their task until well after midnight. Back in the valley, Buell’s First Brigade struggled forward to the foot of the mountain, cursing first the heat, then the rain. Behind Buell, Harker’s Third Brigade floundered in the mud only as far as Pelham. At least twelve wagons stuck deeply in the muck could only be freed by unloading them. Col. Emerson Opdycke’s 125th Ohio Infantry regiment, the division’s rear guard, unloaded wagons, cut downed horses from the traces, and built new paths around mud-holes. At 9:00 P.M., Opdycke halted his men’s efforts and sent them into camp.14

Fortunately for Crittenden’s timetable, John Palmer’s Second Division had a much easier time tackling the Cumberland Plateau than did Wood’s First Division. Orders to move reached the division around midnight after all had retired for the evening, but Cruft’s First Brigade nevertheless got on the road by 8:00 A.M. The division’s route led northeast in the general direction of McMinnville before it turned directly east to assault the Cumberland Plateau. In several regiments the men carried their knapsacks in addition to their weapons, ammunition, rations, blankets, ponchos, and shelter halves. The heat and humidity quickly took a toll on the marching soldiers. Their pain increased as the storm sweeping across Middle Tennessee began to pound them. Marching behind Cruft’s men, Grose’s Third Brigade followed closely on the same track. At least one of Grose’s regiments, the Eighty-Fourth Illinois Infantry, left its large tents and knapsacks behind, easing somewhat its burden in the heat and rain and making the march slightly less tedious. Bringing up the rear was Hazen’s Second Brigade, escorting the division’s train of 300 heavily loaded wagons. Knowing that the march would be difficult for the men on such a hot day, officers in the Forty-First Ohio issued whiskey to those who desired it. Rather than fortify the men for the task ahead, the whiskey only served to sicken some of them as they trudged forward. As a result, a growing body of stragglers trailed the column. At least the men of the Forty-First did not have to carry their knapsacks, as reported by Pvt. George Hodges: “We had no Napsacks to lug, them ware left at Manchester. We may see them again & we may not. I think I rather loose mine than caried it on this march.” By the end of the day, the division had reached the hamlet of Viola, thirteen miles from Manchester, and there it halted for the night. The entire movement had been essentially over flat ground, leaving Palmer’s ascent of the Cumberland Plateau for another day.15

Horatio Van Cleve’s Third Division of the Twenty-First Corps received its movement orders from corps headquarters at 11:00 A.M., and Van Cleve had his command on the road ninety minutes later. The orders required Van Cleve to march to Pikeville, a village in the Sequatchie Valley beyond the Cumberland Plateau, with two of his three brigades and Robert Minty’s cavalry brigade. Leaving George Dick’s Second Brigade to garrison the McMinnville depot, Van Cleve led with Sidney Barnes’s Third Brigade, followed by Samuel Beatty’s First Brigade and the division train of 150 wagons. The army operations order specified that the infantry column was to travel via the village of Spencer, while Minty was to take most of his horsemen by way of Sparta, brushing aside the Confederate force there. According to Van Cleve’s information, however, the Spencer road was impassable, so he followed a lesser road known as the Harrison Trace. This road took a more southerly course than the Spencer road, ultimately climbing to the crest of the Cumberland Plateau and then crossing a virtually uninhabited wilderness until it reached the Sequatchie Valley. Just beyond McMinnville, the infantry column waded the Barren Fork, marched four miles, waded the Collins River, and went into camp at the foot of the mountains. With two river crossings and the rain, which began shortly after the division moved, it was a wet day for everyone concerned, except for Dick’s infantrymen and Minty’s cavalrymen, who remained snug in their camps at McMinnville. Minty could not move until he received a shipment of forage by rail, due that night, so he planned to go to Sparta on the following day. Van Cleve believed that only a lone Confederate cavalry regiment was at Sparta, so he expected no difficulty for Minty. Similarly, he expected the Cumberland Plateau itself to be his only opposition for the next several days.16

The operations order envisioned that the right side of the Army of the Cumberland’s advance would consist of the two remaining divisions of the Twentieth Corps. Sheridan’s Third Division was already manning the front lines at Bridgeport, so it was not involved. That left Jefferson C. Davis’s First Division at Winchester and Richard Johnson’s Second Division at Tullahoma to join the remainder of the army beyond the Cumberland Plateau. Kate McCook was still in camp, and her husband seemed to be in no hurry to leave Winchester. Writing from corps headquarters, McCook’s aide, Capt. Frank Jones, told his father, “Mrs. McCook, Horace Phillips and young George McCook still remain with us and will go north perhaps tomorrow—certainly if we move; which is very probable.” Meanwhile, George McCook, eleven, continued to visit and play with Harry Van Derveer, thirteen, son of a brigade commander in the Fourteenth Corps, who was also in camp with the army. George’s uncle Alex McCook finally ordered Davis’s First Division to begin its advance at 2:00 P.M. on the following day, 17 August, taking a road that would carry the division beyond the Cumberland Plateau into the valley of Raccoon Creek south of Stevenson. Lt. Col. Gates Thruston, the corps chief of staff, enjoined Davis to reduce the division’s baggage to a minimum and load his wagons to only half their capacity in order to make the crossing. With another day of grace, soldiers in the division paid no heed to the rain that pelted Winchester in the afternoon and continued their daily routines. For Lt. Chesley Mosman of the Fifty-Ninth Illinois Infantry regiment of Sidney Post’s First Brigade, it was an enjoyable day. He recorded in his diary, “Went to church, Anderson and I. Meanwhile inspector came around to inspect the Company and no officer there. He said we had ‘the best guns of any company in the Brigade he had seen.’ Citizen choir in church. Pretty girls.”17

Affairs were a bit more hectic in Richard Johnson’s Second Division at Tullahoma. Johnson had received a telegram early in the morning from corps headquarters telling him to move on the next day, but a subsequent message advanced his departure time to that very afternoon. Accordingly, Johnson marched at 3:30 P.M., with Philemon Baldwin’s Third Brigade leading the column. The brigade had only one hour’s notice to break camp, and by the time it departed, rain was widespread in the Tullahoma area. Pvt. David Shideler of the Ninety-Third Ohio Infantry regiment spoke for many when he wrote, “We received marching orders this afternoon. I was lying in my tent at the time and must confess that I was disappointed.” Still, Private Shideler was lucky to be among the first to take the road to Elk River, before it was ruined by rain and marching feet. The brigade halted for the night at Estill Springs. Joseph Dodge’s Second Brigade followed Baldwin’s command, but in Dodge’s absence Col. Thomas Rose of the Seventy-Seventh Pennsylvania Infantry regiment led the movement. According to Sgt. Maj. Lyman Widney of the Thirty-Fourth Illinois Infantry regiment, the men were ready to go, after being in camp so long: “The men were never in better spirits since we left camp Butler or Green River; they acted like so many schoolboys just let loose from school.” Dodge’s brigade also halted at Elk River, but well after dark. In the rear, August Willich’s First Brigade escorted the division train. Before departing, Willich formally cashiered an officer of the Forty-Ninth Ohio Infantry regiment for rape, assault and battery, and straggling. By the time they got on the road at 5:30 P.M., following the heavy supply and ammunition wagons, the route had become nearly impassable. Floundering mules and broken wagons blocked the road every few minutes, preventing the brigade from making more than a few miles before halting in the sodden fields at 2:00 A.M. on 17 August.18

For those units already beyond the Cumberland Plateau, 16 August was a quiet day. At Bridgeport, William Lytle orchestrated a delicate flag of truce negotiation with Patton Anderson’s Confederates. By one account, a Confederate mother desired to pass through the lines to visit her wounded and captured son; by another, a wife sought to cross the river to be with her badly wounded husband. Either way, telegraphic inquiries ascertained that the individual in question was long dead, negating the need for the lady’s passage. Elsewhere at Bridgeport the day consisted of routine picket and fatigue duty. In the Thirty-Sixth Illinois Infantry regiment, Pvt. Ebenezer Lamb borrowed a book on the life of Andrew Jackson from the regimental library, while a captain in the Twenty-First Michigan received the news of the death of his son. Lytle informed Sheridan that a deserter had confirmed that the recent Confederate activity was simply Anderson’s men cooking rations. At Stevenson, Lytle’s aide, Lt. Alfred Pirtle, joined Sheridan and Edward McCook on a visit to Larkinsville on the Memphis & Charleston Railroad. The officers found the M&C feasible as a supply route, although the track was so choked with weeds that the engine slipped badly. Pirtle commented on the locals, “The people were rebels and ugly looking like they used to be last summer—they are behind the times and don’t know the S. C. is ‘played out.’” Back at Stevenson, two more of McCook’s cavalry regiments arrived from downstream. So did the rain, which appeared with diminished force in late afternoon. In the Crow Creek valley, John Starkweather’s three brigades performed road work, suffered through inspection, wrote letters home, and rested in camp. In the Seventy-Ninth Pennsylvania Infantry regiment, which finally received its baggage, Commissary Sgt. William Clark learned that his blanket and shelter half had been stolen. He consoled himself with rumors that Fort Sumter had fallen. At Anderson, the Eighteenth Ohio Infantry regiment of Stanley’s brigade spent the day washing clothes, writing letters, and foraging.19

While most of the army struggled on 16 August to leave its camps, army headquarters planned its own move. Rosecrans himself continued to pressure President Guthrie of the Louisville & Nashville Railroad to loan the army fifty freight cars. Calvin Goddard instructed the Decherd quartermaster to divert all Winchester-bound supplies to Stevenson. Frank Bond instructed George Thomas to guard the supplies remaining at Decherd with the regiment left at Cowan. Robert Thoms instructed Thomas to clear a site in Stevenson for a large field hospital. Both Goddard and Bond telegraphed Sheridan to select a place in Stevenson for army headquarters to occupy on Tuesday, 18 August. Goddard ordered William Innes to furnish a locomotive, five cars, and the dummy on the same day to move the headquarters. Bond and Charles Thompson reminded John Beggs to be sure to have the dummy available when Rosecrans required it. Thoms ordered Gordon Granger to increase the force guarding the army’s reserve ammunition train parked at Tullahoma. Members of the Fifteenth Pennsylvania Cavalry regiment were told to prepare for a move on the next day. Four companies of the Pioneer Brigade reported to the Fourteenth Corps for duty, six companies were assigned to build platforms at Stevenson, 200 men went to Nashville to bring forward the pontoon train, and the remainder of the brigade marched toward Salem for road repair duty. That night, Rosecrans happily informed Lorenzo Thomas, “All three corps are crossing the mountains. It will take till Wednesday night to reach their respective positions. I think we shall deceive the enemy as to our point of crossing. It is a stupendous undertaking.” In fact, out of 22 1/2 infantry brigades under orders to cross the Cumberland Plateau, only three brigades had reached the crest, and five had not moved at all. The primary cause of the delay was the severe storm, but late distribution of the operations order also contributed to the army’s poor performance on 16 August.20

On 17 August the struggles of the Fourteenth Corps continued. In Negley’s Second Division, Sirwell’s Third Brigade descended the mountain six miles to Tantalon Station and camped for the night near some large fields of green corn. The corn provided the only sustenance for the troops as the regiments had exhausted their rations and their wagons remained far behind. Not everyone agreed that the corn was freely available: in the Seventy-Eighth Pennsylvania Infantry regiment, “Col and Lieut Col had a fuss about corn.” Three regiments of Beatty’s First Brigade also reached Tantalon, while the Forty-Second Indiana Infantry regiment was stuck on the side of the mountain behind the division train. Following the Forty-Second Indiana was the remainder of Stanley’s Second Brigade. Several miles to the northeast, Reynolds’s and Brannan’s commands were still behind schedule. Turchin’s Third Brigade left University Place and started down the mountain into the depths of Sweeden’s Cove. Little air stirred in the forest as the men made their way down the rough path into the valley. At last they reached level ground and camped at a large pool of water known as Blue Springs. Three regiments of King’s Second Brigade joined them there. Searching for wood, men of the Seventy-Fifth Indiana Infantry regiment ran afoul of the brigade commander when they followed their colonel’s orders to take nearby fence rails. Confronted by Col. Milton Robinson, King surrendered ungraciously, causing Cpl. William Miller to opine, “Some officers think the private soldier is nothing but a dog and treat them accordingly and if there was no privates we would have no use for officers. About all some officers are real good for is to draw their pay.” Left behind was King’s 101st Indiana Infantry regiment, which Reynolds retained to assist the division train up the west side of the plateau. After taking all day to boost the wagons up the grade, Reynolds and the 101st Indiana bivouacked just beyond University Place. Because Reynolds took so long to move his train, Brannan advanced his division little more than a mile to the western foot of the Cumberland Plateau.21

While Reynolds struggled with his train, other units of the Fourth Division were moving on independent missions. Before taking his brigade into Sweeden’s Cove, Turchin detached Col. Caleb Carlton’s Eighty-Ninth Ohio Infantry regiment to occupy Tracy City, eleven miles away. The Seventy-Second Indiana Mounted Infantry regiment of Wilder’s command was already there. The name of Tracy City was grander than its reality. Founded in the late 1850s as a support center for extensive coal mines owned by the Sewanee Mining Company, the “city” was named for Samuel Tracy, head of the New York consortium that established the mining operation. The company had built the Sewanee Railroad to serve the mines, with its prewar terminus at Tracy City. By the time the Seventy-Second Indiana arrived, Tracy City consisted of only three houses and a depot, although numerous miners’ shacks were scattered in the woods. The remainder of Wilder’s command left camp near University Place in midmorning after finally getting the brigade train up the mountain. Satisfactory for marching troops, the road was more difficult for wagons, forcing a leisurely pace through the forest. Although the distance was not excessive, it was dark before the brigade reached a ravine holding the headwaters of Big Fiery Gizzard Creek. The bridge over that chasm had been damaged, so the First Brigade halted on the west side of the ravine for the night. Nearby was a large trestle that carried the Sewanee Railroad to Tracy City and the mines. Undeterred by the state of the road, Carlton’s Eighty-Ninth Ohio made it all the way to Tracy City. Carlton found neither rations nor a functioning railroad and telegraph station, a poor beginning for a supply depot expected to sustain large numbers of troops. Carlton was not impressed with the hamlet: “It is not a very pretty place a mere hole in the mountains.” The surrounding woods were choked with undergrowth, while the clearings were overgrown with brush. Nevertheless, Tracy City finally had been occupied by Federal forces.22

Farther north, there was also movement in the Twenty-First Corps sector. Wood’s First Division encountered the most difficulty, continuing to struggle on the Park Road. In the lead, Wagner’s Second Brigade finally got its regiments and the brigade train on top of the plateau. After marching only a few miles, Wagner’s men encountered the damaged bridge on Big Fiery Gizzard Creek, which Wood had instructed Wagner to repair with Wilder’s assistance. After pausing for dinner and a brief rest, Wagner’s troops passed two miles beyond Tracy City on the road that would eventually lead to Therman in the Sequatchie Valley. There they camped for the night. Behind them, Wood’s remaining brigades spent all day battling the mountain grade. In the lead, Buell’s First Brigade made every effort to hurry. The wagons were partially unloaded, the teams were doubled, and long ropes were attached to the wagons for men to assist the mules. By using such measures all day and far into the night, Buell’s command reached the top of the plateau. There they went into camp, so weary that they were little hindered by the many rattlesnakes infesting their campsite. A brief panic ensued in the 100th Illinois Infantry regiment when a team trod upon a soldier sleeping in the road, but no lasting damage was done, and quiet soon returned. Behind Buell, Harker’s Third Brigade also reached the top of the plateau, but so late that once again fires had to be kindled on the roadside for light. Last of all, Emerson Opdycke’s 125th Ohio Infantry regiment assisted the 250 half-loaded wagons of the division train until 11:00 P.M. Opdycke joined his men on the ropes used to pull wagons uphill until he became faint and relinquished his place to others. When the teams reached the crest, they unloaded, then returned downhill for their remaining cargo, while the exhausted infantrymen sprawled by the roadside.23

Approximately twenty airline miles north of Tracy City, Palmer’s Second Division had far less difficulty than Wood because it was not yet at the foot of the plateau. Palmer’s men began the day in the hamlet of Viola, located at the foot of an outlying hill mass. Cruft’s First Brigade moved at 9:00 A.M., leading the way first north, then east over a 200-foot rise into a narrow valley called Rodger’s Hollow. The track eventually entered the wider valley of Scott’s Creek, and that valley in turn gave way to the still wider valley forming the watershed of the Collins River. After marching only a few miles in a northerly direction, Cruft halted just beyond a small group of brick buildings known as Irving College. Founded in 1835, the college had suspended operations in 1861. The day was hot, with only a brief shower of rain, straggling was a problem, and several wagons became stuck in the creek bottoms. Nevertheless, by nightfall, Hazen’s and Grose’s Second and Third Brigades had also reached the vicinity of Irving College. There they found a virtual cornucopia of ripe peaches, apples, and green corn, which greatly supplemented the standard army ration. During the evening, Thomas Crittenden joined them there. All could see the steep escarpment of the Cumberland Plateau looming a mile to the east.

If Palmer only reached the foot of the Cumberland Plateau on 17 August, Van Cleve’s Third Division began the day there. Van Cleve had reached Collins River four miles north of Irving College on the previous day. Barnes’s Third Brigade easily made it to the top, then marched eight miles into the wilderness before halting on the headwaters of Rocky River. Van Cleve established division headquarters with Barnes. Behind them, Beatty’s First Brigade spent the day assisting the 150-wagon train to the crest, then advanced several additional miles before also halting for the night. Both brigades had to contend with rattlesnakes in their bivouacs, and one regiment found the energy to raid a sutler’s wagon for bottles of champagne.24

Although Rosecrans’s order gave the Twentieth Corps no more time to cross the Cumberland Plateau than other units, Alex McCook seemed to be in no hurry to leave the comforts of Winchester. McCook may have been distracted by the departure of his young wife, brother-in-law, and nephew. When Davis’s First Division tried to depart Winchester at 2:00 P.M. on 17 August, it found the road blocked by the army headquarters train and its escort. Rosecrans himself cleared the road for Davis. The division’s route led initially toward Cowan but turned south well short of that village. Before he left Winchester, Hans Heg, Third Brigade commander, penned a note to his wife: “I am glad to get off for several reasons. We have laid here till it began to be tedious and times go faster when we are stirring around, but the main reason is that as soon as we have made this move, and get through this campaign, I shall get leave of Absence to go home.” Some of the men left Winchester with regret, believing that the inhabitants had treated them with respect. Soft from their long stay in camp, many overheated soldiers left the ranks as the afternoon progressed. The goal for the afternoon’s march was only the foot of the mountain, five miles from the division’s starting point. North of Winchester, the three brigades of Johnson’s Second Division left their Elk River bivouacs much earlier than Davis’s men. Johnson’s leading brigades crossed Boiling Fork Creek and in late morning entered Winchester. In the lead, Baldwin’s Third Brigade continued five miles beyond the town, camping on the Salem road. There they were joined by Dodge’s Second Brigade, still led by Col. Thomas Rose. In the rear, Willich’s First Brigade continued to assist the division train’s many mired and broken wagons. By the time Willich rejoined the division, the day was spent. In the Forty-Ninth Ohio Infantry regiment, the men received a whiskey ration, but for Pvt. Francis Kiene it was not helpful: “I stood the day’s march very well but this evening while receiving my ration of Whiskey I fainted.” For both Davis and Johnson, the Cumberland Plateau still lay ahead.25

On the Tennessee River there was little activity on 17 August. At Bridgeport, William Lytle forwarded the news from a Confederate picket who had visited the Federal lines briefly: Bragg intended to hold Chattanooga, reinforcements had arrived from Johnston’s army, and 500 men had joined Anderson’s brigade along the river. Some soldiers from the Thirty-Sixth Illinois Infantry regiment enjoyed a refreshing swim in the river, while others took advantage of their new regimental library to form a literary society. In Bradley’s brigade, regimental bands played in the cool of the evening. Pvt. John McBride of the Fifty-First Illinois Infantry regiment thanked his mother for a box of delicacies: “If you have another chance to dont send any tea or sugar for I have enough to last me a great while now. The cheese, cakes, crackers and candy were very nice. … The envelopes and paper could not have come in a better time for our sutler has none worth any thing.” Brigade commander Bradley wrote to his wife on the same day: “We are in good heart and temper for work, and if the rebels want to cross bayonets with us again, we shall not deny them. From all indications, they are not in the most confident humor.” In Stevenson, Bernhard Laibold’s commissary of subsistence noted the arrival of more of McCook’s cavalry division. McCook’s three brigades were scattered. Watkins’s Third Brigade was stationed at Brownsboro to secure the Flint River and Hurricane Creek railroad bridges, McCook’s own Second Brigade had one regiment at Paint Rock Bridge and two at Larkinsville, while Campbell’s First Brigade took position at Bolivar, near Bridgeport. The Memphis & Charleston Railroad was open to Larkinsville, but McCook wanted service to be extended to Boonsboro. He also desired the return of his Second Tennessee (Union) Cavalry regiment, but it continued to work for Sheridan upstream from Bridgeport.26

On the army’s far northern flank, Minty’s cavalry brigade departed McMinnville for Sparta at 2:00 A.M. with 1,400 troopers. Waiting at Sparta was Dibrell’s Eighth (Thirteenth) Tennessee Cavalry regiment, reinforced by 200 men of the Fourth Tennessee Cavalry regiment. On that day half of Dibrell’s command was absent gathering supplies from the countryside. By moving so early, Minty hoped to gain the benefit of surprise, but he encountered Dibrell’s scouts south of Sparta around 2:00 P.M. Alerted, Dibrell deployed on both sides of the Calfkiller River. Upon reaching Sparta, Minty also divided his command. Around 4:00 P.M. he sent the Fourth Michigan and Seventh Pennsylvania Cavalry regiments east of the Calfkiller, and personally led the Fourth United States Cavalry and the six-company Third Indiana Cavalry west of the stream. As they had on 9 August, Dibrell’s men slowly withdrew to a ford across the Calfkiller at Meredith’s Mill. Mistakenly believing that he was outnumbered, Minty did not press Dibrell’s command and at dark ordered a retreat to Sparta. The Fourth Michigan and Seventh Pennsylvania east of the Calfkiller obeyed quickly, but Minty was slow to follow on his side of the stream. Seeing an opportunity, some of the Fourth Tennessee waited for Minty’s column to offer its flank. Carelessly leading the column, Minty was ambushed suddenly by Confederates hidden beyond the Calfkiller. The unexpected blast wounded Lt. Joseph Vale of Minty’s staff and an orderly, along with Minty’s roan mare and several other horses. In a chaotic counterattack, a trooper of the Fourth United States Cavalry regiment drowned. The handful of Confederates quickly escaped, joining Dibrell’s main body on high ground several miles to the north. Minty had gained Sparta again, at a cost of one drowned and fifteen wounded. He claimed to have taken twenty-three prisoners, while Confederate losses were placed at eight killed and thirty-nine wounded. Neither combatant had hurt the other seriously.27

On its last day in Winchester, the army staff bombarded railroad superintendent Innes with queries and instructions. With much of the Reserve Corps ordered south, railroad capacity was strained to the utmost. For the moment, the Nashville & Chattanooga Railroad was handling the load, using cars borrowed from the Louisville & Nashville Railroad. Trains carrying supplies for Granger could operate to Stevenson, then head west on the Memphis & Charleston Railroad. A better solution was to open the line through Columbia to Decatur, where it would connect with the reconstructed Memphis & Charleston. A bridge over the Duck River at Columbia needed to be rebuilt, and Innes twice had been informed that materials were available, but he had not expedited the work. Staff officers Frank Bond, William Porter, and James Drouillard relentlessly chided him about the matter. Worse, a serious accident blocked the N&C main line near Wartrace. In the morning, guerrillas derailed a freight train at Lavergne, delaying it for three hours. When the shaken engineer again took fire, he wildly increased speed, wrecking eleven of nineteen cars at Wartrace. At least six guards were injured and the track remained blocked until 2:00 P.M. Another train added the undamaged cars, but it was so underpowered that it nearly stalled in the Cowan tunnel. Behind the wreck, trains waited in sidings for hours, one until 10:00 P.M. Northbound traffic was also affected, causing army headquarters to query Innes three times about the daily passenger train to Nashville. As for good news, Lt. Col. Henry Hodges arrived from leave, replacing John Taylor as the army’s chief quartermaster. Also, aide Charles Thompson was announced as the new commander of the Twelfth United States Colored Troops, with the rank of colonel. In his terse daily message to Adjutant General Thomas, Rosecrans candidly admitted that only half of his troops had crested the Cumberland Plateau, blaming the failure on heavy rains and bad roads.28

On 18 August, the third day of the Army of the Cumberland’s ponderous lurch beyond the Cumberland Plateau, the Right Wing of the Fourteenth Corps finally began to show real progress. Starkweather’s First Division remained in place on the railroad just east of Anderson Station. When not repairing the road to Stevenson, Starkweather’s men amused themselves fixing up their camps and foraging liberally in the neighborhood. Peaches were both ripe and abundant, and so many soldiers sought them that officers had to curb the absences by instituting roll calls every two hours. Negley’s Second Division passed through Starkweather’s camps during the day. When Negley himself reached Stanley’s Second Brigade, he ordered it to leave Anderson and march down the Crow Creek valley toward Stevenson. Stanley’s men were joined on the road by Sirwell’s Third Brigade. Before leaving camp, Sirwell’s men had to retrace their steps up the mountain to their wagons for rations, then return downhill. The day was hot, with high humidity, causing large numbers of stragglers to dribble from the rear of the marching regiments. Becoming irate, Negley accosted Lt. Col. William Ward, commanding the Thirty-Seventh Indiana Infantry regiment, and capriciously placed him under arrest. Thus encouraged, Stanley’s and Sirwell’s brigades continued their march far into the evening, finally halting at a large spring three miles short of Stevenson. Far behind them, men of Beatty’s First Brigade returned to the crest of the plateau to retrieve the knapsacks dumped from overburdened wagons, then headed south in Negley’s wake. They halted just beyond Anderson because Col. Oscar Moore, temporary brigade commander, saw plainly that the exhausted men could go no farther. They had not yet reached their final bivouac sites, but at least the Right Wing’s divisions had successfully crossed the Cumberland Plateau. Thomas himself and his headquarters party left Decherd and stopped for the night at the eastern portal of the Cowan tunnel.29

Thomas’s Left Wing also made progress on 18 August, but not nearly as much as the remainder of the corps. Joseph Reynolds began 18 August with King’s and Turchin’s brigades camped at the large Blue Spring near the head of Sweeden’s Cove. Because Turchin had led the column on the previous day, Reynolds left him at Blue Spring and marched five miles down Sweeden’s Cove with King’s men to a new bivouac on the lower reaches of Battle Creek, just two miles from the Tennessee River. A signal detachment with Reynolds ascended the mountain above the camp and reported that it could see trains running on the stub of the Nashville & Chattanooga Railroad between Shell Mound and Anderson’s camps near Bridgeport. King’s troops, however, were the only elements of Reynolds’s command to reach the Tennessee River valley. Turchin’s brigade remained at Blue Spring, while Brannan’s Third Division spent all day struggling up the western slope of the Cumberland Plateau. Croxton’s Second Brigade led the division on the well-worn Brakefield Point pathway to the crest at University Place. Van Derveer followed Croxton with his Third Brigade. Van Derveer was accompanied by his son Harry, thirteen, who delighted in the stirring scenes of the ascent and wrote his chagrinned mother accordingly. Connell’s First Brigade was next, followed by the division train. With the road dry, the infantrymen ascended without much difficulty, but the mule teams struggled with the heavy wagons. As teamster Daniel Bruce explained, the day consisted of nothing but “stopping, stalling, and breaking wagons.” Still the division was at last atop the plateau. Two brigades settled into camp at University Place, near the desecrated cornerstone of Bishop Polk’s college, while the remaining brigade continued to Turchin’s old camp two miles nearer the plateau’s eastern edge.30

Ten miles north of Reynolds’s and Brannan’s route, John Wilder’s Lightning Brigade began the morning of 18 August just short of Tracy City. There a broken bridge over the headwaters of Big Fiery Gizzard Creek delayed the column. Wilder assigned bridge reconstruction to the Ninety-Second Illinois Mounted Infantry regiment, his newest and least-favored unit. While waiting for the road to be opened, he wrote a brief note to his wife explaining his role in the army deception plan. Proudly he told Martha Jane Wilder, “As usual, they have assigned me the most difficult part of the movement.” By midmorning the bridge had been improved enough for wagons to cross and the troopers began their march. Passing through the collection of log huts that was Tracy City, they rode in a northerly direction toward the village of Altamont. Several miles short of that settlement the horsemen turned eastward, leaving Altamont to their left. They moved easily, on a generally level road through a sea of trees. Many of those trees were pines, which were unfamiliar to several soldiers from Indiana and Illinois. The men also encountered numerous large rattlesnakes, which seemed to infest the entire Cumberland Plateau. A slight shower of rain cooled the journey briefly, but the march was generally hot and dry. Not long after noon, Wilder’s troops encountered the infantrymen of Wagner’s Second Brigade of Wood’s First Division, Twenty-First Corps. Wagner had preceded Wilder on the road from Tracy City and was halted for lunch when the horsemen arrived. With Wilder having priority of movement, Wagner’s men waited several hours for Wilder’s brigade and its train to gain the lead. The Lightning Brigade soon passed out of sight, although its wagons delayed Wagner for the remainder of the afternoon. Eventually Wilder’s brigade halted for the night at a wilderness road junction known as Bryant’s, and Wagner’s men bivouacked several miles behind them.31

Rosecrans’s deception plan called for Wilder to be supported by Crittenden’s Twenty-First Corps, which was also struggling to surmount the Cumberland Plateau. Wood’s First Division on 18 August remained scattered. Wagner’s Second Brigade had already ascended the mountain and made good progress until forced to relinquish the lead to Wilder. Wood’s remaining two brigades, however, had yet to complete their climb to the Cumberland Plateau. Both Buell’s First Brigade and Harker’s Third Brigade spent the morning lifting their last wagons up the grade to the top of the plateau. Along the way, much baggage had to be discarded before the teams could drag the residue forward. Nevertheless, by late morning everything essential was on top of the mountain, and Wood decreed a rest until 1:00 P.M. Harker was so pleased with the performance of Col. Emerson Opdycke’s 125th Ohio Infantry regiment that he summoned Opdycke to share a convivial glass of wine. Then, to the accompaniment of regimental bands, Buell’s and Harker’s men resumed their march toward Tracy City, covering the five miles by dark. There they found Col. Caleb Carlton and his Eighty-Ninth Ohio Infantry regiment. Carlton had been detached from John Turchin’s command to protect the supply depot at Tracy City. The wretched settlement loomed large in Rosecrans’s mind as a critical supply point not only for Wilder but for most of the Twenty-First Corps as well. Unfortunately, Carlton had nothing to issue because the railroad from Cowan had not yet begun operating. Nor was the telegraph line to Cowan working. Still, Carlton was delighted to see Wood’s brigades arrive. Wood and Harker, the latter a West Point classmate of Carlton’s, visited the garrison commander and shared recent experiences. Carlton no doubt voiced his pleasure at being detached from Turchin, the Russian’s unconventional habits and loose discipline being especially irksome to Regular Army officers. In a letter to his wife describing the reunion, Carlton expressed the hope that his detachment from Turchin would be permanent.32

Operating north of Wood’s track, Crittenden’s other divisions also made progress on 18 August. Twenty-two miles north of Tracy City, Palmer’s Second Division left Irving College, forded the Collins River, and followed the narrow valley of Hills Creek until it confronted the steep headwall of the Cumberland Plateau. Leading the ascent, Hazen’s Second Brigade fought its way to the summit with three regiments, leaving the Forty-First Ohio Infantry behind to guard the division’s train of 300 wagons. Hazen halted eight miles beyond the crest on a relatively level road through the forest. Behind him, most of Cruft’s First Brigade reached the summit in midafternoon, then moved two miles farther on Hazen’s route. Left behind were Cruft’s train and its guards. Finally, Grose’s Third Brigade also reached the crest, but only by leaving its wagons at the foot of the mountain as well. By this time the men had exhausted their rations, but occasional peach orchards provided ripe fruit as a substitute. Last of all was the Forty-First Ohio and the division train. Everywhere on the mountain, the soldiers encountered rattlesnakes but were so weary that they lay down in the forest anyway. Five miles north of Palmer, Van Cleve’s two brigades similarly were scattered along the rough track known as Harrison’s Trace. During the morning Van Cleve and Barnes’s Third Brigade waited briefly at the headwaters of Rocky River in order for Beatty’s First Brigade to join and then continued through the wilderness for ten more miles. Beatty finally succeeded in raising the division train to the top of the plateau and plodded forward in Barnes’s wake. For much of their journey, Van Cleve’s troops encountered no sign of human habitation. Exhausted by their labors, both brigades bivouacked in the forest. During the night, a herd of cattle accompanying the column escaped its enclosure and wandered among the sleeping soldiers, knocking over stands of weapons and trampling men. The resulting shouts led to a brief stampede, ruining the night’s rest.33

Like their compatriots to the north, the men of McCook’s Twentieth Corps made progress in their battle with the rugged Cumberland Plateau on 18 August. Davis’s First Division began the day at the foot of the mountain a short distance south of Cowan. The route uphill had already been traversed by Rosecrans’s headquarters guard units, but the headquarters train was still at the foot of the mountain. Thus the regiments of Post’s First Brigade lined the rocky road to assist the heavily loaded wagons. Post’s train and the division ordnance train of fifty wagons also required assistance. With great effort, Post’s men gradually pushed and pulled the wagons uphill. In midafternoon Carlin’s Second Brigade relieved Post’s weary soldiers and the process of lifting wagons continued. The regimental historian of the Eighty-First Indiana Infantry regiment wrote, “Just imagine a train of wagons stretched out for miles and a whole brigade of men in their shirt sleeves strung along on each side, tugging at the wheels, pulling at ropes, the drivers using the most emphatic language you ever heard to the mules, then you may form some idea of the scene.” All along the road the plateau’s ubiquitous rattlesnakes made their appearance but were hardly more than a curiosity to the toiling troops. Eventually, Heg’s Third Brigade joined Post and Carlin on top and all moved forward several miles. Fifteen miles southwest of Davis, Johnson’s Second Division ascended the foothills of the plateau through White’s Gap. East of the gap the three brigades followed a faint road along and through a stream named Larkin’s Fork. Willich’s First Brigade led the column, followed by Baldwin’s Third Brigade, while Dodge’s Second Brigade trailed the division train. After a march of fifteen miles, Johnson halted his drenched command. Some traded their wet clothes for army blankets, but others did not, a decision they regretted when the night turned cool. Although surrounded by mountains, Johnson had yet to confront the western escarpment of the Cumberland Plateau.34

While his soldiers battled with the mountain on 18 August, Rosecrans’s thoughts turned to the next obstacle, the Tennessee River. Thus, Calvin Goddard asked William Innes about the dimensions of the Bridgeport railroad bridge, and Frank Bond queried Capt. Arthur Edwards, a quartermaster officer with Great Lakes maritime experience, about building small steamboats at Bridgeport. Bond charged Innes and Ferdinand Winslow, acting chief quartermaster at Nashville, with preparing lumber to Edwards’s specifications at sawmills at Stevenson and Wartrace. Lt. George Burroughs, one of the army’s staff engineers, reported that thirty pontoons were at Elk River, ten were at Murfreesboro, and sixty-four were at Nashville. Thirty pontoon wagons were moving forward with part of the Pioneer Brigade. Innes had only seven flatcars at Nashville, and he wanted to use them for other cargo unless Rosecrans decreed otherwise. He also reported that he only had twelve reliable locomotives and many wrecked cars. Nevertheless, Bond ordered him to prepare three hospital cars and ship half a carload of Sanitary Commission supplies each day to Stevenson on the passenger train. Both Innes and John Starkweather at Anderson were told to have idle men cut wood for locomotive fuel. Gordon Granger was ordered to guard the Nashville & Chattanooga Railroad all the way to Tantalon. Informed that no supplies had been stockpiled at Tracy City, and that the Twenty-First Corps would soon exhaust its forage, Rosecrans warned the quartermaster at McMinnville to be prepared to sustain Crittenden’s animals. Finally, Rosecrans invited Governor Andrew Johnson to join the army at the front on Thursday. At last, Rosecrans and his staff boarded the dummy and headed for Stevenson. Still seriously ill, Chief of Staff Garfield traveled on a bed carried aboard the car. As their husbands departed for the front, the wives of Alex McCook, David Stanley, Calvin Goddard, Arthur Ducat, and John Taylor left Winchester on the northbound passenger train.35

The headquarters party arrived at Stevenson at 1:30 P.M., where they were welcomed by Sheridan and Laibold. David Swaim supervised Garfield’s removal from the dummy and transfer to a quiet lodging away from the frenetic activity at the depot. While his staff established headquarters at a small brick house also distant from the depot, Rosecrans took the dummy a short distance down the weed-choked Memphis & Charleston Railroad. He returned to Stevenson at dark on what even then was coming to be called “Rose’s buggy.” In Rosecrans’s absence five freight trains arrived at Stevenson, clogging the junction until their cargo was unloaded. If Stevenson was a hive of activity, Bridgeport exhibited what one diarist called “the dull monotony of camp life.” Men in Lytle’s brigade spent the day cleaning their camps and listening to preaching by a Christian Commission representative. In Bradley’s command some amused themselves by swimming in the river while others watched the continuing trickle of deserters crossing into the Federal lines. One man noted that the river level was dropping, thereby opening more crossing sites. In overall command at Bridgeport, Lytle asked Sheridan about improving the Bridgeport fortifications. If the army was going to advance soon, additional work would be wasted; if not, more effort should be made to secure the Federal position. Lytle also inquired about the status of the Second Tennessee (Union) Cavalry regiment, which momentarily seemed to be working for no one. Confronting the enemy at Bridgeport, Lytle was only vaguely aware of the massive logistical effort in his rear, and the struggles of the divisions crawling over the Cumberland Plateau. Rosecrans saw it all, and he was pleased, as reflected in his nightly message to Lorenzo Thomas: “My Head Qrs. Moved today to Stevenson Alabama. The commands all moving well, better today than yesterday.” Nearly 200 miles to the north, in Crab Orchard, Kentucky, Ambrose Burnside telegraphed Rosecrans that he, too, had begun his advance.36

Rosecrans’s operations order required that Thomas’s Fourteenth Corps reach its final positions by the end of Wednesday, 19 August. In the Right Wing, Starkweather’s First Division remained in its designated camps in the Crow Creek valley between Anderson Station and Stevenson. Negley finally consolidated his three brigades around Cave Spring, three and a half miles north of Stevenson. Thomas’s Left Wing continued to lag behind. Reynolds’s Fourth Division consolidated in camps on Battle Creek, three miles from the Tennessee River. Far behind Reynolds, Brannan’s Third Division spent all day descending into the upper reaches of Sweeden’s Cove. The day was excessively hot, a temperature of 108 degrees being recorded at Estill Springs. The men had to carry their knapsacks as well as rations, water, guns, and ammunition, causing the usual straggling. Still the brigades of Connell, Croxton, and Van Derveer all successfully negotiated the steep descent and camped near the Blue Spring. Now that the two divisions of the Left Wing were in the valley of Battle Creek, the logistical plan called for them to be sustained from Tracy City. Unaware that there was still no depot at Tracy City, Reynolds opposed sending his wagon trains back up the plateau simply because of the difficulty of the route. He penned a note to Thomas seeking permission to draw rations and forage from Stevenson. The message to Thomas passed through army headquarters, which denied Reynolds’s request. When Reynolds’s request reached Thomas in the Crow Creek valley, the corps commander supported Reynolds. That evening, Rosecrans relented, permitting Reynolds to draw upon Stevenson for subsistence. At the same time, Rosecrans ordered Reynolds to occupy the village of Jasper, six miles to the east at the mouth of the Sequatchie Valley, on the following day.37

The army operations order required Crittenden’s Twenty-First Corps to be in position in the Sequatchie Valley by Wednesday night as well. The march of Wood’s First Division had been complicated from the beginning by the need to follow Wilder’s command. Wilder had an especially long train composed of both wagons and a string of pack mules. On 19 August Wilder’s brigade left the top of the plateau and soon began the descent into the Sequatchie Valley. When the leading Ninety-Second Illinois Mounted Infantry regiment encountered Confederate pickets near the foot of the mountain, it halted and deployed. Irked by the regiment’s caution, which was incompatible with his style of operations, Wilder replaced the Ninety-Second with the Seventy-Second Indiana Mounted Infantry regiment and rushed the handful of defenders. Vastly outnumbered, the small Confederate force hastily retreated through the road junction known as Therman and scattered. The pickets likely belonged to McDonald’s Cavalry Battalion, temporarily led by Capt. Philip Allin, which Bragg had sent to picket the Sequatchie Valley. Part of the Seventy-Second drove across the narrow valley to the Sequatchie River, killing and capturing several Confederates, while another company surprised some citizens holding several Union sympathizers in a school. In a report to Reynolds, Wilder claimed that his brigade captured eleven Confederates, although the haul ultimately approached twenty. The brigade then moved six miles north of Therman to the village of Dunlap, which consisted of two log houses, a store, and the one-story Sequatchie County courthouse. Although the village was unimpressive, the surrounding fields of green corn and peach orchards were a different matter. Especially delighted to reach Dunlap were the men of the Eighteenth Indiana Battery, who had slept atop their ammunition chests the previous night because of the rattlesnakes infesting the plateau. Henry Campbell, one of the gunners, found the Sequatchie Valley such a pleasant place that he recorded in his diary, “Wouldn’t mind staying here for some time.”38

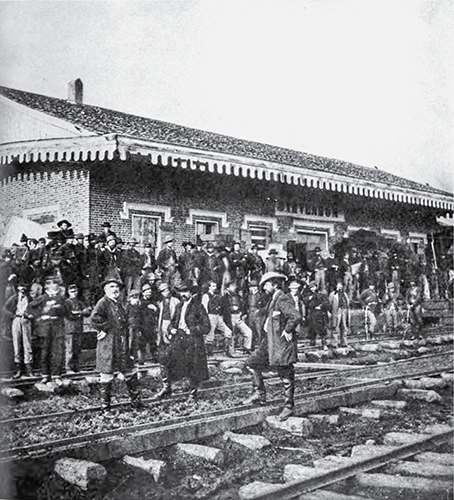

Rosecrans at the N&C Depot, Stevenson, Alabama. (Miller, Photographic History)

Following Wilder to Therman was Wood’s First Division. Wagner’s Second Brigade reached the valley floor in late afternoon. Wood’s remaining brigades were far behind Wagner, but Wood was determined to meet the schedule at all costs. He therefore instructed Buell and Harker to expedite their progress across the relatively flat plateau. Three of Buell’s regiments reached the foot of the mountain at Therman soon after dark, but the brigade train and the 100th Illinois Infantry regiment remained on top. Similarly, Harker’s brigade raced twenty-eight miles, arriving at Therman around 9:00 P.M. As on the climb uphill, Emerson Opdycke led his 125th Ohio Infantry regiment by personal example. Opdycke walked much of the way, sharing his horse with exhausted soldiers. On reaching the descent, he raised a shout and led his men in a charge down the slope. Like Buell’s train, Harker’s wagons bivouacked on top of the mountain. Palmer’s Second Division also got units into the Sequatchie Valley on 19 August. Cruft’s First Brigade arrived first, marching into Dunlap in midafternoon. With Cruft were Crittenden and his young son. Behind Cruft came several regiments from both Hazen’s Second Brigade and Grose’s Third Brigade, all of which camped around Dunlap. Four regiments remained on the plateau with brigade and division trains. The story was much the same twenty miles northward, where Van Cleve and most of his command descended the mountain to Pikeville. Like Dunlap, Pikeville was unimpressive, Pvt. Marcus Woodcock of the Ninth Kentucky Infantry regiment considering it “neither large, nor populous, nor thriving nor beautiful.” In his report to Crittenden Van Cleve noted that most of Minty’s cavalry had arrived that evening from Sparta. Minty was scheduled to probe beyond Walden’s Ridge on the next day, but his train was far behind him. Van Cleve was also nervous about his tenuous supply route to either McMinnville or Tracy City. Still, Crittenden’s Twenty-First Corps had, for the most part, met Rosecrans’s schedule.39