14

SAND MOUNTAIN

» 2–4 SEPTEMBER 1863 «

At 6:00 A.M. on Wednesday, 2 September, Lieutenant Colonel Hunton reported to Sheridan that the Bridgeport bridge was available for infantry to cross the stream and that wagons could use the structure by noon. The first troops to use the bridge were pickets from the Thirty-Sixth Illinois Infantry regiment, who had been on duty on Long Island, and who crossed to Bridgeport to rejoin their fellows in Lytle’s First Brigade. Lytle’s troops led the division across the rickety structure at noon, followed by Bradley’s Third Brigade. Laibold’s Second Brigade brought up the rear, crossing in midafternoon. Thereafter, Sheridan’s command followed the railroad to Taylor’s Store and turned up a narrow track over Hogjaw Ridge. Surmounting the ridge, the Federals descended into Hogjaw Valley and sprawled around Moore’s Spring to await their wagons carrying rations and camp equipage. Already at Moore’s Spring was Beatty’s First Brigade, the vanguard of Negley’s Second Division. Even though Negley had already selected campsites for the brigades of Stanley and Sirwell, still toiling up the dusty road from Caperton’s, Sheridan’s men paid no heed and seized the best remaining camping grounds for themselves. Outraged by their behavior, Negley complained to Thomas, but Sheridan’s soldiers remained in place. Clearly Sheridan’s aggressive spirit had been transmitted to his troops, and the fact that the divisions belonged to two different corps only exacerbated the situation. Even though all the units of the Army of the Cumberland were laboring toward a common goal, that fact did not preclude friction between commands. Indeed, much of the friction sprang from the personalities of senior leaders who had taken the measure of their peers during the previous year’s campaigning. Small in stature but bold and pugnacious to a fault, West Pointer Sheridan, thirty-two, was contemptuous of the portly and affable Negley, thirty-seven, a citizen soldier whose date of rank preceded Sheridan’s by a month. On 2 September the dispute was minor, with only campsites being at issue, but more significant differences lay ahead.1

The Bridgeport bridge figured large in Rosecrans’s plans, as both Sheridan’s command and Baird’s division were slated to use it. Even more important, hundreds of baggage wagons, supply wagons, ammunition wagons, and ambulances waited to make their way gingerly across the river. Already in position were Sheridan’s and Brannan’s trains, and the trains of Long’s Second Brigade, Second Cavalry Division. Coming from the Sequatchie Valley were the trains of Crittenden’s Twenty-First Corps, all of which were to cross at Bridgeport in lieu of being slowly ferried across the stream at Shell Mound. Baird’s division trains and the wagons of miscellaneous organizations completed the mob of teamsters, mules, and wagons fighting for a place in the single line of wheeled vehicles forming below the Bridgeport fortifications. Somehow, the baggage wagons of Connell’s First Brigade of Brannan’s division were first in line when Sheridan’s infantry exited the bridge. In midafternoon Connell’s teamsters began negotiating the spindly trestles and bobbing pontoons to Long Island. The wagons of Connell’s infantry regiments went first, and the wagons of his artillery battery brought up the rear of the column. For a brief time, all went well, but suddenly around 3:30 P.M. the trestle section from the midchannel pontoons to Long Island suffered a catastrophic collapse. The baggage wagons of Battery D, First Michigan Light Artillery, had almost reached the safety of the island when the falling trestle bents dumped five heavily loaded wagons, their drivers, and their mule teams into the river. According to a newspaper correspondent who was present, “One moment the bridge, with its creeping monstrous burden, was quietly spanning the olive waters of the Tennessee; the next there was a corresponding line of partly submerged wagons, a maelstrom of struggling mules, a confused clambering among the pale and frantic drivers, and a tangled, loose raft of timbers, bubbling up end-wise from the wreck, and sweeping about with lessening swiftness into the tumbled current.”2

For a moment, onlookers gaped in shock as approximately 700 feet of trestlework dropped into the stream. At the site of the collapse the water was little more than four feet deep, but the mules were so tangled in harness and bridge debris that they could not escape the wreck. Rescuers manning spare pontoons eventually freed all but one of the mules, which drowned before it could be saved. Similarly, the pontoons facilitated the salvage of most of the cargo. Emptied of their loads, the now buoyant wagons were eventually poled to shore. The rescue complete, the men of the First Michigan Engineers and Mechanics began the painful task of reconstructing their handiwork. They were assisted by Pioneer Brigade engineers, who had laid the pontoon bridge on the other side of Long Island. There had long been a rivalry between the two units, with the Michiganders casting aspersions on the capabilities of the Pioneers. Now Pioneer Brigade soldiers had the satisfaction of seeing random pieces of their tormenters’ work floating lazily down the river, while their own bridge stood “solid as a rock.” Examination of the wreckage and eyewitness accounts revealed that the bridge had failed initially where it joined the free-floating pontoons in the deepest part of the channel. In their haste to construct the trestle, Hunton’s men had not braced the bents but simply stood them in the stream, relying on the balks to keep the trestle upright and rigid. The flowing water had eroded the streambed around the bents, making them unstable. As each heavily laden wagon crossed the structure, it caused the bents to oscillate, and the vibration eventually caused the connection between the pontoons and the trestle to break. With no anchor on one end and no support in the riverbed holding them vertical, the bents folded toward the island like a house of cards under the weight of the wagons. This explanation for the disaster became obvious after the bridge’s collapse, but the pressure to finish the bridge quickly had been intense. Haste had made waste.3

Pontoon bridge built by Pioneer Brigade over ship channel of Tennessee River at Bridgeport, Alabama. (Michigan Organizations at Chickamauga)

With no inkling of the looming disaster, Rosecrans and his staff spent the morning coordinating the movements of the army’s most distant units. At 10:00 A.M., Garfield instructed Crittenden to send one brigade to Shell Mound and a second to Battle Creek. Either Crittenden or Palmer was to cross the river and deploy the Twenty-First Corps troops to the left or rear of Reynolds’s division. Crittenden was also enjoined to gather his trains behind his right and improve the road net around Shell Mound. At 11:00 A.M. Garfield telegraphed Granger, Innes, and Col. Charles Thompson, forbidding the dispersal of Thompson’s regiment of United States Colored Troops in anything smaller than battalion size. For the moment, Thompson’s newly formed command would be allowed to continue training at Elk River Bridge as a unit. Finally, Garfield instructed Morgan of the Reserve Corps to use Tillson’s First Brigade to relieve the Fourteenth Corps garrisons along the Nashville & Chattanooga Railroad, in lieu of Dan McCook’s Second Brigade, which would now continue toward Stevenson. Goddard wrote to Granger about command relationships at McMinnville, now that the Reserve Corps was assuming responsibility for that post. In addition, he wired Morgan at Flint River to protect a sawmill at Larkinsville, as the army would need its lumber. He firmly admonished McCook for delaying Negley’s trains at the Caperton’s Ferry bridge on the previous night. Bond suggested to Sheridan that he follow Negley up Sand Mountain via Moore’s Spring. Bond, too, wired Granger, suggesting ways to protect the large amount of supplies at Carthage. Thoms’s task for the day was to arrange the transportation of one of Rosecrans’s horses to Cincinnati. Finally, at 2:00 P.M. Garfield invited Crittenden to join Rosecrans, Thomas, and McCook at Bridgeport at 6:00 P.M. if possible, while Drouillard warned Sheridan that he would soon have important visitors. By the time the meeting convened, the crisis at the bridge would drastically change its agenda.4

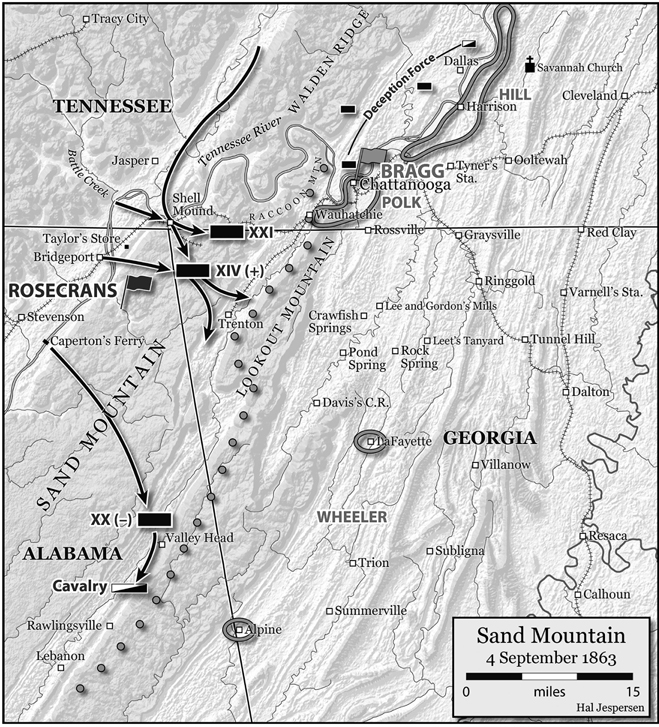

McCook’s orders for the day required him to cross Sand Mountain into Wills Valley and advance to a point known as Valley Head, where it would seize the crossing of Lookout Mountain known as Winston’s Gap. McCook himself remained at Stevenson, but Davis’s First Division had been on Sand Mountain for two days. According to the plan, Davis would advance to Winston’s Gap, Johnson would follow Davis in support, and Sheridan would rejoin the corps at Winston’s after crossing Sand Mountain behind the Fourteenth Corps. The sooner McCook’s troops topped Lookout Mountain, Rosecrans reasoned, the greater pressure there would be on the Army of Tennessee to evacuate Chattanooga. Therefore, the Twentieth Corps needed to resume its advance quickly. Preceded by two companies of the First Tennessee (Union) Cavalry regiment, Post’s First Brigade marched from the present crossroads of Flat Rock at 6:00 A.M. and headed southeasterly into the forest. Although elevated far above the valleys on its flanks, Sand Mountain was relatively flat on top. Covered with pines and hardwoods, the mountain was virtually unpopulated. Only occasionally did the men of the Twentieth Corps encounter residents, mostly women and children living in extreme poverty. They were friendly enough, with several expressing pleasure at seeing the U.S. flag again. According to Lt. Chesley Mosman, there were “some very pretty women to be seen.” Less impressed was Sgt. Lewis Day, who opined, “The few people—citizens—that we saw, did not look as though they knew enough to last them through the week, nor did their actions belie their looks.” Other than a few Confederate cavalry scouts flushed by Davis’s advance guard, the march proved to be tiring but uneventful. In late afternoon Post’s men descended the eastern slope of Sand Mountain and camped at its foot, several miles short of William Winston’s plantation. Behind them, Carlin’s and Heg’s brigades followed Post’s track. By the time Heg’s men halted for the day, night had fallen, but they too were at the foot of the mountain.5

Because of their rapid march, Davis’s three brigades found themselves alone in the narrow four-mile wide trough between Sand and Lookout Mountains. The terrain where they halted for the night, however, was more complex than anyone had anticipated. In fact, there was not one valley separating Sand and Lookout Mountains, but four, depicted on modern maps as Sand Valley, Dugout Valley, Big Wills Valley, and Railroad Valley. Behind the Federals, Sand Mountain rose more than 450 feet above them at Troxel’s Gap. In their front were three small, parallel ridges. No more than 200 feet tall, the ridges stood athwart the direct route to Winston’s plantation and the road up Lookout Mountain. They also divided the terrain into discrete compartments. Post stopped in the first compartment, Sand Valley, but Carlin and Heg continued forward into Dugout Valley, camping on the small farm of Philip Young. Lt. Chesley Mosman of the Fifty-Ninth Illinois Infantry regiment dismissed any concerns about the division’s precarious situation: “It seems queer for Rosecrans to move his men down in rear of the Rebel Army and thus invite an attack … but I’ll let old Rosey boss the job.” In both valleys, Davis’s men wreaked havoc on the chickens, hogs, and potatoes their pleasant surroundings offered. Their nearest support was Johnson’s Second Division, which spent the day heaving its wagon train up the west face of Sand Mountain. Pvt. Francis Kiene of the Forty-Ninth Ohio Infantry regiment found the road only dusty, but Pvt. Oliver Protsman of the First Ohio Infantry regiment claimed the track up the mountain was “the Worst road wee have Ever encountered.” Ill with fever, Lt. Col. William Robinson of the Seventy-Seventh Pennsylvania Infantry regiment took quinine, but his only relief came in reaching the crest: “Sick and weary of a soldier’s life, but the air feels purer, and by morning I hope to be better. More quinine.” Johnson’s division halted for the night only two miles beyond the crest, nearly twenty miles behind Davis.6

Although the Twentieth Corps momentarily was in front, Stanley’s Cavalry Corps was expected to lead the Army of the Cumberland’s flanking movement. Stanley’s command, however, was not yet in position to play its assigned role. Campbell’s First Brigade of the First Cavalry Division was scattered from the Bridgeport crossing site to the river valley below Caperton’s Ferry. During the morning, LaGrange’s Second Brigade and Watkins’s Third Brigade, received orders to march at 12:30 P.M. to the pontoon bridge. Moving the skittish horses and mule-drawn wagons over the bridge took all afternoon but was completed without incident. With the difficult track up Sand Mountain clogged by Johnson’s infantrymen, the two brigades turned south a short distance and camped at the mouth of Raccoon Creek. Meanwhile, the Second Michigan Cavalry regiment from the First Brigade left its camp across from Bridgeport and scouted twelve miles up Sand Mountain on the road eventually to be taken by Negley and Sheridan. Finding no enemy on the road to Trenton, they returned to Moore’s Spring with the news that the way was clear. Meanwhile, Crook’s Second Cavalry Division also crossed the river. With Minty’s First Brigade absent, Crook’s command momentarily consisted only of Long’s Second Brigade. Most of Long’s troopers had used the difficult ford at Hart’s Bar during the initial seizure of the east bank of the river, so the cavalry commanders considered it safe for continued use. The Chicago Board of Trade Battery and the division trains would cross via the Bridgeport bridges, but Long’s four regiments would use the ford. In a dramatic scene, Long’s troopers safely threaded their way through the twists of the ford to the east bank, although some men had to swim for their lives in the process. Long then led the Second Kentucky toward the Bridgeport bridges to meet the train, while Crook marched the remaining regiments toward Caperton’s Ferry. Meanwhile, the battery made it across the Bridgeport bridge before it fell in midafternoon, but the division train had not yet crossed when the bridge collapsed.7

Thomas’s Fourteenth Corps mostly lay still on 2 September, with only Baird’s First Division in motion toward the Bridgeport crossing site. Starkweather’s Second Brigade traveled to Stevenson from the Crow Creek valley, then took the dusty road to Bridgeport via Bolivar. As they passed Stevenson, they were joined by the First Wisconsin Infantry regiment, which had been clearing ground for a hospital. Capt. John Otto of the Twenty-First Wisconsin Infantry regiment was not impressed with Stevenson, “a conglomerate of several dozen miserable looking shanties erected in a barren sandy plain.” In an effort to avoid eating Starkweather’s dust, the First Brigade’s Benjamin Scribner received permission to use a shortcut from Anderson Station over the mountain behind Stevenson, a poor choice because the unimproved track was almost impossibly difficult. Eventually Scribner’s exhausted men reached Widow’s Creek and followed it to the Bridgeport road, where they joined Starkweather’s troops. By the time they neared Bridgeport, the bridge had fallen, so Baird’s two brigades camped a few miles short of the crossing site. Beyond the stream, Negley’s Second Division concentrated around Moore’s Spring in Hogjaw Valley, intermixed with Sheridan’s division. At Battle Creek, Brannan crossed the river, but his wagons did not. In the Tenth Indiana Infantry regiment, men searched for the previous day’s drowning victim by firing a cannon over the water. While his compatriots foraged aggressively, Musician Billings Sibley wrote his mother that, except for the ignorant inhabitants, “this is a most beautiful country and should like to live here if it was not so far out of the world.” At Shell Mound, Reynolds also moved across the river but experienced delay in getting his trains to the east bank. His men meanwhile swam, foraged, visited Nickajack Cave, and viewed the boundary stone marking the junction of Tennessee, Alabama, and Georgia. On a sadder note, soldiers in the Seventy-Fifth Indiana Infantry regiment sorrowfully recovered the body of drowning victim Robert Commons and buried him nearby.8

At Jasper, Crittenden was again without specific orders. At 8:45 A.M. he wrote to Garfield, “General Reynolds informs me that he will be through crossing at Shellmound at 2 P.M. Shall I then commence crossing?” In a tone that never would have been used with Thomas or even McCook, Garfield at 10: 00 A.M. gave Crittenden detailed instructions on how to locate his troops on the far shore. At 3:00 P.M. Crittenden ordered Wood to send a brigade to the Shell Mound crossing site. At the same time he instructed Palmer to dispatch a brigade to Battle Creek. Realizing that the lateness of the hour meant that any crossing necessarily would occur at night, both Wood and Palmer questioned the need for haste. At 4:40 P.M. Crittenden’s assistant adjutant general responded peremptorily, “The general cannot change the order as to crossing, as he is directed to effect it as rapidly as possible, and General Reynolds has informed him that the crossing would be clear this (4) p.m.” Reluctantly, Wood selected Buell’s First Brigade to march to Shell Mound during the evening to see if Reynolds would be true to his word. Palmer chose Grose’s Third Brigade for the trip to Battle Creek but almost immediately postponed Grose’s departure until the following morning. Crittenden meanwhile received the invitation from Garfield to meet with Rosecrans, Thomas, and McCook at Bridgeport at 6:00 P.M., a time Crittenden could not meet. All the while, Van Cleve pushed his Third Division southward through the heat and dust toward Jasper. Van Cleve’s arrival meant that the long sojourn of the Twenty-First Corps in the isolated Sequatchie Valley was finally finished. The soldiers in the ranks speculated endlessly about their destination, but at least one officer harbored doubts about how it all would end. In a letter to his wife from Jasper on 2 September, Palmer exclaimed, “I am well satisfied that Rosecrans though a good soldier in the face of the enemy is not the man to conduct a complicated campaign. He lacks steadiness and breadth of thought.”9

With Rosecrans’s army precariously straddling the Tennessee River, the role of the deception force had never been more important. At the same time, with the Twenty-First Corps leaving the Sequatchie Valley, the deception force had never been more alone. Still, the four brigades assigned to mislead the Confederates stuck to their task. In Wilder’s command, the day passed peacefully, broken only by the capture of two Confederate scouts. Interrogation of the scouts yielded only that Forrest’s command was nearby. Wilder’s artillerymen spent the day unpacking 400 rounds of ammunition that had arrived on the previous evening. Wilder himself studied dust plumes rising from the direction of Tyner’s Station and Ringgold and concluded that a large body of troops had moved to that vicinity. He also received a report from John Funkhouser, who reported a great deal of “chopping or pounding” within the Confederate lines and concluded that they were either repairing wagons or building boats. Wilder sent the information to Rosecrans and, in a separate note, told Reynolds that he could cross the river at Williams Island whenever he wished. From Poe’s Tavern, Hazen also reported increased Confederate activity. In response he moved units ostentatiously toward the river and played band music at several widely separated locations. On Walden’s Ridge, Wagner’s brigade welcomed the arrival of regimental baggage from the Sequatchie Valley. In the Ninety-Seventh Ohio Infantry regiment, a detail of carpenters and boatmen worked on boats to ferry the command across the river. North of Hazen, Minty continued to worry about his exposed position. A flurry of deserters from the Twenty-Sixth Tennessee Infantry regiment brought news of Buckner’s withdrawal and the concentration of Forrest’s cavalry. Minty feared an attack by Forrest and urgently voiced his concerns to Hazen, Crittenden, and Rosecrans. Still, he continued to display his command at the river, especially at Blythe’s Ferry. Minty also reported making contact with Burnside’s forces near Kingston.10

Behind the front the Reserve Corps was stirring to life. At McMinnville, Col. James Shelley arrived with three loyal Tennessee regiments to relieve Dick’s Second Brigade. Shelley’s own regiment had remained at Carthage, where the unpopular James Spears had just taken command. Both Shelley and Spears complained to Rosecrans about the confused command situation. Meanwhile, Dick prepared his brigade to move to the front. At the other end of the department, Second Division commander Morgan arrived at Flint River with Tillson’s First Brigade. There he received orders to bring Tillson’s troops to Stevenson and relieve King’s Third Brigade of Baird’s division along the railroad. Not knowing the location of McCook’s Second Brigade, which was somewhere behind him, Morgan held Tillson’s command at rest for another day. As for McCook, the three regiments with him spent a long day marching through what Pvt. Thomas Burns called the “largest woods I ever saw.” Their throats parched from the suffocating dust and lack of water, McCook’s men staggered into Athens by the end of the day. McCook’s last unit, the Eighty-Sixth Illinois Infantry regiment, remained far behind at Columbia, waiting to be relieved by troops from Clarksville and Fort Donelson. In Morgan’s Third Brigade, Col. Heber Le Favour’s Twenty-Second Michigan Infantry regiment prepared to leave Nashville for Stevenson. In the midst of their preparations, friends of deceased Pvt. Lewis Yerkes, twenty-one, borrowed enough money to have their comrade’s body embalmed and shipped to his Michigan home. Along the line of the railroad, Champion’s First Brigade of Steedman’s Second Division remained in its camps at Estill Springs, Fosterville, and Tullahoma. Reid’s Second Brigade quietly garrisoned Shelbyville and Wartrace, while the 121st Ohio Infantry regiment marched to Cowan to relieve another Fourteenth Corps unit, the Sixty-Ninth Ohio Infantry regiment. Coburn’s Third Brigade held Murfreesboro, while elements of Robert Granger’s Third Division patrolled Nashville, Clarksville, and Carthage.11

At Bridgeport the fall of the trestle threatened to derail all of Rosecrans’s plans. Not only was Baird’s division prevented from crossing the river, but the failure to move the trains of several units created supply problems. Sheridan’s division had made it across the stream but, without the division’s wagons, the troops lacked blankets and rations. Sheridan’s men shamelessly begged such items from Negley’s division, even after rudely appropriating the best camping places around Moore’s Spring. Some of Brannan’s troops were in similar circumstances. Thus Lieutenant Colonel Hunton quickly sent hundreds of men into the waist-deep water to wrestle the heavy timbers back into an upright position. This time, Hunton ordered the bents to be braced, in the manner of carpenter’s sawhorses. In the midst of the rebuilding effort, Rosecrans arrived on the dummy with Thomas and McCook. Originally scheduled as a review of the campaign plan, the meeting now became an effort to craft a new and very tentative movement schedule. Worse, the Twenty-First Corps was unrepresented because Crittenden did not appear. Rosecrans asked Hunton to explain the problem and his proposed solution, chiding him about the original lack of bracing. Still, there was no point in blaming Hunton and his engineers; whatever their guilt in the original failure, they were now the only people who could rectify the problem. Thus Hunton remained in charge of the reconstruction effort. With nothing further to be seen or done by the generals, Rosecrans and his party returned to Stevenson. After thinking about the problem on the brief train trip, Rosecrans asked Hunton if troops could use the bridge while the engineers were working. Hunton replied affirmatively, but before any significant movement occurred, the bridge crashed into the stream again shortly after 9:00 P.M. Apprised of the collapse, Rosecrans at 10:30 P.M. ordered Hunton to remove his men from the water until daylight.12

The collapse of the trestle bridge was not the only bad news Rosecrans received on 2 September. Grant’s quartermaster at St. Louis informed him of bureaucratic delays in shipping forty spare freight cars to Louisville. Another message, from Halleck, provided minimal information on Burnside’s progress toward Knoxville. Undaunted, Rosecrans continued to conduct business far into the night. He asked the president of the Louisville & Nashville Railroad to expedite the movement of material to rebuild the Bridgeport railroad bridges. He importuned Secretary of War Stanton to replenish his contingency fund, saying, “I am going now where it will be much needed.” News also arrived from Crittenden, who had finally reached Bridgeport. In response, the staff quickly arranged for the dummy to bring Crittenden to Stevenson. At 10:30 P.M., Crittenden and his staff reached army headquarters. Thirty minutes later, Rosecrans sent Halleck his daily summary of significant events. His chief focus was the bridge disaster, although Rosecrans minimized its severity and its effect on the timing of the army’s advance. Instead, Rosecrans heralded the fact that Sheridan’s division had gotten across the stream, Crittenden’s corps was beginning to cross in boats, and one of McCook’s divisions was probably at Valley Head. He also projected that Stanley’s cavalry would push southward to Rawlingsville in Wills Valley on the next day. Rosecrans noted that Confederate rumors placed Burnside in Knoxville already. Indeed, Rosecrans could have been even more positive about developments than he actually was in his report to Halleck. Sheridan’s and Stanley’s crossings meant that by the end of the day he had placed seventeen of his thirty infantry brigades and four of his five cavalry brigades on the east bank of the river. At Shell Mound, Buell was even then ferrying a Twenty-First Corps brigade across the stream. Slowly but surely, the Army of the Cumberland was surmounting its first major obstacle, a process that the Bridgeport disaster would only delay, not halt.13

Rosecrans’s troubles on 2 September were entirely invisible to Bragg, who still had no accurate picture of what the Federals were doing. Dispatches from both Mauldin and Wharton, no longer extant, apparently indicated that a very large force of Federals had crossed the river below Bridgeport and was somewhere on Sand Mountain. Trenton seemed to be threatened by a slightly smaller party. Still, the ubiquitous Captain Rice reported at 10:00 A.M. from a signal station on Lookout Mountain that no enemy was visible on the valley floor. For the moment, major elements of Rosecrans’s army had disappeared. At noon, Bragg convened a conference at his headquarters in the Chattanooga suburbs. Present were Polk, Hill, Cheatham, Hindman, Cleburne, Walker, Wheeler, Liddell, and Mackall. According to Liddell, Bragg opened the session by stating that Rosecrans had crossed the river below Chattanooga with two corps while threatening the city directly with two more. He then called for comment, beginning with Liddell, the junior man present. Taken aback, Liddell suggested that the Federals were apparently seeking to cross Lookout Mountain and threaten the railroad to Atlanta, forcing the army to evacuate Chattanooga in order to protect its supply line. In Liddell’s opinion, such a move offered a splendid opportunity for Bragg to counterattack the Federal flanking column after it had advanced beyond the support of the remaining Federal units. When Polk mildly objected that surely Rosecrans would not be so incautious, Liddell responded that his easy victory in the Tullahoma campaign had made Rosecrans overconfident. The reference to Tullahoma brought a smile to Polk’s face but not to Bragg’s, and Liddell realized that inadvertently he had raised a controversial issue. Hill quickly defused the situation by proposing a rapid crossing of the Tennessee River and the Cumberland Plateau, followed by an invasion of Middle Tennessee. Liddell countered that neither the army’s transportation nor the food available in “the barrens” could sustain such a course of action.14

Bragg suddenly stood and dismissed Hill’s proposal out of hand. Satisfied with what he had heard about Rosecrans’s probable course of action, he posed a new question: Should the army make an immediate attack on that portion of Rosecrans’s army that was across the river below Bridgeport? Again, Bragg looked directly at Liddell. Making the most of his opportunity, Liddell launched into his opinion. To Liddell, the question was simply one of timing. If the Federals operating below Bridgeport were struck too soon, they would simply recoil quickly across the river. Chattanooga having been evacuated, the Federals opposite the city would capture it before the Army of Tennessee could return. The difficulty in crossing Lookout Mountain also caused Liddell to counsel delay. He argued that it would be wiser to let the Federals struggle across the mountains, far from their base, before striking them a mortal blow. Liddell therefore expected that the decisive battle would be fought somewhere south of Chattanooga near the town of LaFayette. Upon hearing Liddell, Bragg queried the others for their opinions. According to Liddell, all except Wheeler reluctantly agreed with him. Noting Wheeler’s silence and harboring animosity toward him dating to Stones River, Liddell pointedly asked Bragg to seek Wheeler’s opinion. Bragg refused to do so, in Liddell’s opinion a transparent attempt to disguise Wheeler’s inadequacies. The council then adjourned, leaving Liddell smugly confident of victory if his proposal was adopted. Following the council, Bragg telegraphed Secretary of War Seddon: “Rosecrans’ main force has crossed the Tennessee below Bridgeport opposite Stevenson. He is sixty miles from us with two ranges of barren mountains interposed. Unable to hold so long a line without sacrificing my force in detail. Buckner has been drawn this way so as to secure a junction at any time. Burnsides was sixty miles from Knoxville at last accounts. We shall assail either party or both whenever practicable.” For the moment, St. John Liddell had carried the day.15

As the generals dispersed, the army staff went into action. First, George Brent issued a series of instructions to the frontline cavalry commanders. Mauldin at Trenton was told to scout the enemy’s positions on Sand Mountain and determine their intentions. In order to report what he learned quickly, Mauldin was to establish a courier line directly to Chattanooga. A similar order was sent to Wharton at LaFayette. Wheeler’s other division commander, Martin, was simply told to “report promptly and frequently” to army headquarters. Brent next turned to the question of arms for those men without them, especially the new arrivals from Mississippi. First, he polled both Polk and Hill for the number of unarmed men. Next, he telegraphed Josiah Gorgas at Richmond to see if any arms were in transit. At the same time, chief of ordnance Oladowski specified to Moses Wright, Atlanta Arsenal commander, the number of rounds he required for each of the army’s 104 artillery pieces. He pointedly told Wright, “Send only few canister for each gun.” In personnel matters, Brent notified Buckner that Col. John Kelly would be sent to replace Col. James McMahon as a brigade commander in Preston’s Division. A native of Alabama and a West Point attendee before resigning in 1860, Kelly, twenty-three, was the colonel of the Eighth Arkansas Infantry regiment in Liddell’s command. Distinguished in action at Shiloh and Perryville, and wounded at Stones River, Kelly had long been recognized as a rising star. Brent duly notified Liddell of his loss and Buckner’s gain, while Kelly headed to join his new command at Charleston. With a major battle looming in the near future, Chief Quartermaster McMicken dispatched Capt. Robert Gribble to Dalton and Marietta to accelerate the establishment of hospitals for the expected influx of casualties. Gribble was assigned to work with the efficient if abrasive Samuel Stout, medical director of hospitals. In order to resolve the continuing impasse over the use of the Georgia Military Institute for hospital purposes, Bragg himself appealed to Governor Brown for their use.16

Two critical issues remained unresolved at the end of the day. First, Chief Commissary of Subsistence Giles Hillyer calculated the army’s supply of meat and bread would be exhausted in three weeks. Either food had to be released from Atlanta stocks earmarked for the Army of Northern Virginia, or the shrinking territory controlled by the Army of Tennessee had to be scoured anew, or Federal stocks had to be captured. If nothing was done, the army would have to retreat or begin to starve. The second issue was linked with the first. In order to act decisively, Bragg needed more timely information on Federal movements. To date, that kind of information had not been furnished by Wheeler’s Cavalry Corps. Since July only two small regiments had picketed the army’s left flank and there apparently had been no system to notify Bragg in a timely fashion if that line was penetrated. Any reports generated went up the chain eventually to Wheeler’s headquarters at Gadsden. Wheeler apparently had made nothing of any reports he received and seems to have been out of communication with Bragg until he reached Chattanooga on 2 September. When Bragg learned that the picket line had been penetrated and Sand Mountain overrun by large Federal forces, he had to communicate directly with individual units, bypassing Wheeler entirely. Significant Federal forces spilling over Sand Mountain into Wills/Lookout Valley was bad enough; if they crossed Lookout Mountain the army’s lifeline to Atlanta would be in peril. With food running low, loss of the railroad would be disastrous and Chattanooga would most certainly be lost. Liddell’s proposed counterstrike could only succeed if Bragg received timely information on Federal activity beyond his flank, and Wheeler had not provided it. Wheeler finally appeared at army headquarters on 2 September, but according to Liddell he contributed nothing to the discussion. If Bragg was indeed shielding Wheeler from overt criticism, as Liddell believed, continuing to do so would place at grave risk his army’s chances for success.17

On 2 September Chief of Staff Mackall wrote privately to Wheeler chastising him for his failures: “I am uneasy about the state of affairs. It is so vitally important that the general should have full and correct information. One misstep in the movement of this army would possibly be fatal.” He explained what should have been obvious to Wheeler, that the loss of Sand Mountain left Lookout Mountain as the army’s final picket line on its left flank. Mackall was blunt: “The passage at Caperton’s Ferry broke the line, and a week has passed and we don’t know whether or not an army has passed. If this happens on Lookout, say to-night, and the enemy obtain that as a screen to their movements, I must confess I do not see myself what move we can make to answer it.” When Wheeler received Mackall’s rebuke is unknown, but he generated a flurry of orders before the day was over. Special Orders, No. 68, issued while Wheeler was still at Chattanooga, ordered Wharton to picket the routes over Lookout Mountain from Wills Valley and patrol the crest of the mountain from Chattanooga to Gadsden. Information gained should be reported to Bragg, Wheeler, and to the bridge guards at Resaca and Etowah. Another message ordered Wharton to place one brigade at Alpine, Georgia, on the road from Valley Head, and the other at LaFayette. Wheeler also directed Martin to concentrate most of his command between LaFayette and Dalton. The only portion of Martin’s Division not to move toward LaFayette was Mauldin’s detachment holding Trenton. Wheeler now wanted Mauldin to form a line from Kelly’s Ford on the Tennessee to Lookout Mountain in the vicinity of Wauhatchie. Wheeler’s orders thus relinquished control of approximately ten miles of Lookout Valley to any Federals who might appear. From Wauhatchie south, Wharton’s La Fayette brigade was responsible for blocking any Federal incursions. Until Martin’s command could get itself together, Wharton’s division was all that stood between the Army of the Cumberland and the rear of the Army of Tennessee.18

In the ranks, word of the Federal crossing had spread widely, and discussions turned to the great battle that all expected to occur soon. Capt. James Hall was confident, writing to his father, “There is no doubt in my mind that a general engagement is imminent and there is just as little doubt about our success.” Artificer D. L. Kelly was not so sanguine of victory, opining, “Cousin Jane you would like to hear some glorious ware news from this part of the Confederacy I no but I have no good newes to tell you but of a sertainty we are on the eave of a grate Battle and perhaps the greatest one that has bin faught during the war. All seem to be in good spirits … but the thing looks very dark to me.” With the return of Hindman’s Division to McFarland’s Spring, Polk’s Corps was reunited in Chattanooga Valley. Most of Hindman’s men spent the day resting after their grueling night march, although several hundred were detailed to work on fortifications. In Cheatham’s Division, Brig. Gen. Otho Strahl’s Brigade guarding Lookout Valley was on high alert, but even there not everyone was actively watching for the enemy’s approach. In the Fifth Tennessee Infantry regiment, those soldiers not on picket duty found that they could make marbles from the malleable stone surrounding them and whiled away the dull hours shaping the playthings. In Hill’s Corps, Cleburne’s Division spent the day gradually withdrawing from the upper Tennessee River crossings and concentrating near Harrison. Elements of Breckinridge’s Division were still arriving at Chickamauga Station, but Stovall and Breckinridge remained absent. As the last units arrived, they marched to Tyner’s Station, where the division was concentrating. Walker’s Division was already at Tyner’s, organizing its trains and preparing for either movement or action. In Liddell’s Division, guarding the army’s dwindling supplies at Chickamauga Station, many soldiers attended religious gatherings, a phenomenon widely observed in Bragg’s army on 2 September.19

Cleburne’s gradual withdrawal from the river fords to Harrison meant that the bulk of Bragg’s infantry would soon be concentrated for rapid movement in any direction. This concentration would uncover at least seven crossings between Harrison and Blythe’s Ferry unless other troops occupied the now thinly held defenses. Cleburne’s departing men were to be replaced by Forrest’s cavalry, which was to connect with Buckner’s command holding the line of the Hiwassee River. During the day James Wheeler’s and Dibrell’s Brigades from Forrest’s Division continued their march toward the Tennessee River from Charleston. Also moving in that direction was part of Pegram’s command. Behind the horsemen, Preston’s Division occupied positions five miles west of Charleston, where it guarded the Hiwassee line from Candies Creek to Charleston itself. Stewart’s Division momentarily remained at Charleston, around Buckner’s headquarters. Forty-two miles north of the Hiwassee, a portion of Scott’s Brigade still held a bridgehead beyond the Tennessee River at Loudon, where a 1,700-foot rail and road bridge spanned the stream. Somewhere between Loudon and Charleston, Scott’s remaining troopers covered Buckner’s train, toiling toward safety south of the Hiwassee. At 4:00 P.M., Buckner exercised his right to contact Secretary of War Seddon directly, informing him that Cumberland Gap was still guarded by Frazer’s Brigade, Jackson’s railroad guards and a few cavalry units had withdrawn to Virginia, and that he held the line of the Hiwassee River as Bragg’s Right Wing. Buckner admitted that he knew nothing of Rosecrans’s movements, but that Burnside appeared to be moving toward a junction with the Army of the Cumberland under cover of the mountains beyond the Tennessee. Still, Buckner was upbeat: “The present concentration gives up temporarily the country between this place and Bristol. The best hopes are entertained of this concentration. Troops in fine spirits.”20

What seemed so hopeful at Charleston did not look quite so positive to Pvt. William Sloan of the Fifth Tennessee Cavalry regiment of Scott’s Brigade. The most advanced vidette north of the Loudon bridge, Sloan suddenly saw a Federal cavalry column round a bend in front of him. The Federals proved to be part of Burnside’s Twenty-Third Army Corps. Firing a shot that downed one horse and rider, Sloan dashed a half-mile south to the picket reserve, chased all the while by shots from the pursuing Federals. After briefly checking the Federal horsemen, Sloan’s comrades raced across the bridge on decking that had been laid between the rails to facilitate the passage of troops. While other members of the regiment manned the entrenchments on the north side of the river, Sloan and his companions fired piles of turpentine-soaked wood on the bridge’s lower deck. A masterpiece of prewar bridge design, the massive two-story, tin roofed structure soon became fully involved in flames. As the fire consumed the span, the Tennesseans continued to keep the Federals from the bridge. When the fire had mostly done its work, they left their trenches and crossed the river on a large flatboat. Their retreat was covered by fire from two three-inch rifles of Robinson’s Louisiana Battery. Unable to fire on the flatboat, Federal gunners shelled Loudon itself, setting a house ablaze and causing some casualties. Confederate efforts to destroy the flatboat were unsuccessful, but the destruction of the bridge was complete. With no reason to remain at Loudon longer, the Fifth Tennessee headed south, halting late at night at Athens, twenty-five miles to the south. Behind them, the Federals quickly occupied the south bank of the river, but their hopes of using the railroad were dashed. Learning of the fight at Loudon, Buckner at 8:30 P.M. informed Bragg that the bridge was probably gone. More significant, Buckner stated that Federal cavalry had entered Knoxville, severing the direct connection to Virginia. Plaintively, he asked Brent, “Shall I move my infantry in vicinity of Georgetown to sustain cavalry?”21

If not quickly reversed, the loss of the railroad between Knoxville and Loudon would have far-reaching effects on Confederate planning. The East Tennessee & Georgia Railroad represented part of a direct 540-mile route from central Virginia to Chattanooga. Any reinforcements sent from Virginia to Bragg’s army would most readily be dispatched along that route. Now, that direct link had been severed. Meanwhile, Davis’s discussions with Lee about Confederate strategy continued in Richmond. Lee argued vigorously to keep the Army of Northern Virginia intact and on the offensive in its home territory. Yet Davis for some time had been aware of Bragg’s precarious situation. A recent note from Senator Landon Haynes of Tennessee had prematurely announced the fall of Knoxville, while a telegram from Governor Isham Harris had bluntly called for reinforcements to be sent to the Army of Tennessee. Davis had already tapped Johnston’s command for aid and was cajoling Governor Brown of Georgia for militia assistance. Lee’s arguments notwithstanding, his army was another potential source of aid for Bragg’s beleaguered command. While Lee was in Richmond, James Longstreet commanded the Army of Northern Virginia. For six months Longstreet had advocated shifting troops from Lee to Bragg, usually with himself as the detachment’s leader. In August, he again had approached Secretary of War Seddon and Senator Louis Wigfall of Texas with the scheme, but those efforts had seemingly failed on 31 August. Longstreet now saw the Tennessee crisis as another opportunity to advance his proposal. On 2 September he acknowledged Lee’s orders to prepare the army for offensive action but again pressed for the adoption of his own plan: “I know but little of the condition of our affairs in the west, but am inclined to the opinion that our best opportunity for great results is in Tennessee. If we could hold the defensive here with two corps and send the other to operate in Tenn. with that army I think that we could accomplish more than by an advance from here.”22

Expecting the collapsed trestle to be repaired quickly, Rosecrans early on 3 September issued the instructions that would drive his campaign for several days. The document reflected his plan to threaten both Bragg’s supply line and Chattanooga in order to force him to withdraw southward without a fight. Crafted by Garfield, the order established the objectives for each corps and often specified how to attain them. First, the Cavalry Corps was to advance via Rawlingsville across Lookout Mountain to the vicinity of Rome. Stanley was to “push forward with audacity, feel the enemy strongly, and make a strong diversion in that direction.” The order specified that Stanley’s First Division was to take the direct road over Sand Mountain from Caperton’s Ferry to Valley Head, while the Second Division was to cross Sand Mountain to Trenton, then follow Wills Valley to Valley Head. Next, McCook was to gather the Twentieth Corps at Valley Head and seize Winston’s Gap on Lookout Mountain. Thomas was to consolidate the Fourteenth Corps at Trenton and send a division to seize two gaps on Lookout Mountain. Specifically, Thomas was to occupy Frick’s Gap northeast of Trenton with one brigade, while sending the remainder of the division via a cul-de-sac valley named Johnson’s Crook to capture Stephens’s Gap southeast of Trenton. The Twenty-First Corps was to advance from Shell Mound up the canyon of Running Water Creek as far as the village of Whiteside. From there Crittenden was to probe toward Chattanooga via Lookout Valley with one division and ascend Sand Mountain via Murphy’s Hollow with his remaining units. The order formally gave Hazen command of the deception forces, but detached a regiment each from Minty’s and Wilder’s commands to join Thomas and Crittenden. Hazen was to continue the deception indefinitely and, if the opportunity arose, cross the river and seize Chattanooga. Finally, King’s brigade of Baird’s division was to remain in place on the railroad until relieved by Morgan’s Reserve Corps division. All movements were to be completed by the close of the next day, 4 September.23

While Confederate leaders pondered their next moves, Pioneer Brigade soldiers worked all night in the murky Tennessee River to restore the trestle bridge. Rosecrans had ordered work halted until daylight, but that order did not reach the Pioneers. At dawn the men from the First Michigan Engineers and Mechanics resumed work, and together the two units struggled in the shallow water to erect the fallen bents and connect the trestle to the pontoons. The work was exceedingly difficult, slow, and tedious, but this time Hunton assured Garfield that the bridge would be much stronger than before. Meanwhile, more than 1,000 wagons and ambulances awaited a chance to cross the stream. Baird moved his two available brigades to Bridgeport and assumed command of the reconstruction effort. Upon reaching the river, some of Baird’s men seized the opportunity to wash away the choking dust that covered everything. Unwilling to remain in Stevenson all day while the work continued at Bridgeport, Rosecrans joined Baird during the afternoon and established the priority of movement across the span. First to cross would be Sheridan’s trains, followed by the trains of Crook’s Second Cavalry Division. After Crook’s wagons would come Brannan’s division trains, followed by Baird’s division and its trains. Bringing up the rear would be the large trains of the Twenty-First Corps. The entire process would take several days, the pace being driven first by the engineers and then by the skill of teamsters coaxing their mule teams across the shaky trestles and swaying pontoons. Drouillard, one of Rosecrans’s aides, recorded completion of the bridge at 1:00 P.M., but diaries of Pioneer Brigade members indicate that the bridge was not reopened for several more hours. Even then, Pvt. Isaac Roseberry wrote, “After much hard work and waiding in water waist deep we got it ready so teams could cross by diner but the general opinion is that it will go down again.” Should it do so, the already worrisome delay in executing Rosecrans’s campaign plan would be extended.24

For the two divisions camped around Moore’s Spring, only Sheridan’s command had to wait for its wagons. Negley’s division was under no such restraint, having crossed its trains at Caperton’s Ferry two days earlier. Therefore Negley ordered his three brigades to begin their ascent of Sand Mountain. Sirwell’s Third Brigade led the way, distributing men along the track to assist the wagons and battery. Soon the temperature began to climb, making the hard pull up the mountain even more disagreeable. Unwilling to remain spectators, both Negley and Sirwell stripped off their uniform coats and put their shoulders to the wheels of several wagons. To encourage the men even more, the Twenty-First Ohio Infantry regiment’s band played a spritely version of “Dixie” as the heavily laden wagons crawled up the grade. Traveling with the column was a regimental sutler whose wagon overturned, spilling its contents to the delight of the nearby soldiers. Sirwell’s command finally reached the top of the mountain and marched three miles across the plateau to a deep ravine. Providentially, Negley’s men found an abandoned sawmill in the ravine whose lower story could serve as a bridge foundation. Two companies soon began to transform mill into bridge. As Sirwell’s brigade camped around what they called Warren’s Mill, Stanley’s Second Brigade was toiling up the mountain. Stanley’s battery had difficulty making the climb. Only by hitching twelve horses on each gun was it able to reach the crest, and three horses died in the process. On top at last, Stanley’s men moved only a slight distance before halting for the night. Beatty’s First Brigade brought up the rear. Escorting the division ammunition train, part of Beatty’s command reached the top, but the remainder remained at the foot of the mountain with the division supply train. Weary as he was, Cpl. George Harris of the Forty-Second Indiana Infantry regiment was impressed: “We have a fair view of the river, Bridgeport, the rail road, battle creek and the mountains all around, as nice a view as I ever saw.”25

At Shell Mound, Reynolds’s Fourth Division began its ascent of Sand Mountain during the afternoon. Reynolds’s route lay southward in Nickajack Cove to the headwaters of Cole City Creek. The cove’s walls abounded with exposed coal seams that had been exploited by small mining operations like the Castle Rock Coal Company. The tracks of the Nicojack Railroad & Mining Company extended eight miles up the cove on a gradually ascending grade. Thus Reynolds’s leading unit, Turchin’s Third Brigade, had an easy pathway up Sand Mountain. On top, the road crossed relatively flat terrain until it reached the eastern edge of the mountain. After an easy descent, Turchin’s men entered Slygo Valley, drained by Squirrel Town Creek, where they found the extensive plantation of William Cole. Concerned about his surroundings, Turchin sent scouts to the nearby Trenton-Chattanooga road. Ominously, lights could be seen atop Lookout Mountain in the distance. Behind Turchin, King’s Second Brigade halted on the mountain. Brannan’s train had been caught by the collapse of the Bridgeport trestle, so his Third Division only moved to Turchin’s old camps at Shell Mound. While waiting, many of his men visited Nickajack Cave, as hundreds had done earlier. Unfortunately, the cave remained a dangerous place, literally full of pitfalls. As forecast by another soldier earlier, the cave claimed a life when Cpl. Samuel McIlvaine of the Tenth Indiana Infantry regiment slipped and was mortally injured in a fall. Slightly less unlucky was a man in McIlvaine’s brigade who was shot in the leg by a soldier aiming at a pig. During the day corps commander Thomas moved his headquarters from Bolivar to Moore’s Spring via Stevenson and Caperton’s Ferry. While a regimental band played “The Star-Spangled Banner” at Moore’s Spring, Thomas issued orders for the next day: Baird was to follow Negley as soon as he could cross the river; Reynolds was to seize Frick’s Gap on Lookout Mountain; and Negley was to move toward Stephens’s Gap via Brown’s Spring, where Thomas planned to join him.26

Shell Mound was a popular place on 3 September. Not only was Reynolds’s division leaving and Brannan’s division arriving, but units of the Twenty-First Corps were beginning to appear as well. Reynolds did not complete the transfer of his train across the river until 2:00 P.M., thereby delaying the passage of Wood’s First Division across the stream. By seizing boats and rafts idled by Reynolds during the previous night, Buell had been able to transport his First Brigade over the river by 6:00 A.M. His baggage train, however, remained snarled in the traffic jam at Bridgeport. While they waited, Buell’s men visited Shell Mound’s tourist sites, Nickajack Cave, and the surveyor’s marker delineating where three states met. By midafternoon, Reynolds’s train was finally over the river, and Wood hurried Harker’s Third Brigade to the crossing site. For the next seven hours, Harker pushed his regiments across the river, using Reynolds’s motley collection of rafts and boats. Next in line was a herd of cattle. After efforts to force the animals to swim across the stream failed, they were finally transported by raft in small groups, a tedious and time-consuming process. Behind the cattle came Cruft’s First Brigade of Palmer’s Second Division. Ordered initially to Battle Creek, Cruft received new orders diverting his brigade to Shell Mound and his wagons to Bridgeport. Before leaving Jasper, the band of the Ninetieth Ohio Infantry regiment serenaded the locals with “Yankee Doodle,” while other men looted the few civilian stores. It was nearly midnight when Cruft’s men began to cross the river with the aid of the rising moon. Earlier, Palmer and Grose’s Third Brigade reached Battle Creek around noon. Finding insufficient rafts and boats, Grose had to construct more before beginning his crossing. It would take all night for Grose to place three regiments on the far bank, sending one regiment with his trains to Bridgeport. Behind Palmer’s command, two brigades of Van Cleve’s Third Division reached Jasper and went into camp. At the same time, Dick’s Second Brigade departed McMinnville on its long journey over the Cumberland Plateau.27

The collapse of the Bridgeport bridge significantly affected the movements of McCook’s Twentieth Corps. Dawn of 3 September found Davis’s First Division camped in the tangled terrain several miles short of Winston’s Gap. Instead of continuing his advance, Davis had been told during the night to go no farther than absolutely necessary to get water. With Sheridan delayed on the far side of Sand Mountain and his request for cavalry denied, Davis had no choice but to remain where he was. During the morning Carlin sent scouting detachments all the way to Winston’s, but in the afternoon he withdrew nearer Sand Mountain and formed line of battle with the remainder of the division. Meanwhile, Johnson’s Second Division marched slowly across the top of Sand Mountain but halted before descending into Wills Valley. During the hot and dusty march some men of the Fifteenth Ohio Infantry regiment discovered an abandoned distillery. Their attempt to make peach brandy failed, but soldiers of the Thirty-Ninth Indiana Mounted Infantry succeeded well enough to become gloriously drunk. Speeding past both foot soldiers and wagons, McCook and his staff joined Johnson in early afternoon. The headquarters train was far in the rear, so McCook decided not to descend the mountain that day. Also on the mountain road was Stanley’s Cavalry Corps. Although Rosecrans had expected the cavalry to reach Rawlinsville, several miles south of Winston’s, to protect Davis’s southern flank, Stanley decided that Rawlinsville was beyond reach on 3 September. He halted Edward McCook’s First Division at Davis’s position and sent Long’s Second Brigade of Crook’s Second Division to occupy Winston’s. Stanley did not descend into the valley, camping instead with Alex McCook and Johnson a mile short of the brow of Sand Mountain. His trains were scattered from there all the way back to Caperton’s Ferry. Until the news from Bridgeport was better, both McCook and Stanley would pause for at least a day before tackling Lookout Mountain.28

Unaware that their mission was increasingly irrelevant, the deception force remained highly visible on 3 September. For Wilder’s regiments facing Chattanooga, most of the day was consumed in foraging for vegetables, meat, and fodder. Men in the Seventy-Second Indiana Mounted Infantry regiment were overjoyed to receive the first mail in two weeks, as well as their regimental baggage. Atop Walden’s Ridge, soldiers in Wagner’s brigade also engaged in routine tasks, except for those men building small boats to cross the river flowing placidly below them. Upstream at Poe’s Tavern, Hazen received orders to assume command of the entire deception force. Necessitated by Crittenden’s departure from the Sequatchie Valley, the order placed almost 7,000 troops under Hazen’s control. He wasted no time in making his wishes known, especially to Col. John Funkhouser of the Ninety-Eighth Illinois Mounted Infantry regiment of Wilder’s brigade. Funkhouser had cooperated with Hazen but had not been under his command. Now Hazen made clear who was in charge, ordering Funkhouser to provide him an escort company and changing the position of his units. Styling himself Commander, U.S. Forces, Left Flank of the Army, Hazen elevated Col. Oliver Payne of the 124th Ohio Infantry regiment to temporary command of his old brigade. He then began an inspection tour of his new domain, which he believed stretched seventy-five miles from Williams Island to Kingston and included at least twenty crossing points. He also ordered boats to be gathered in North Chickamauga Creek for crossing the river. Fearing that Minty’s brigade was at risk if the Confederates pushed across the river, Hazen sought Minty’s assessment of the situation. Meanwhile, Minty sent the band of the Fourth Michigan Cavalry regiment to the riverbank to serenade his opponents with the “Bonnie Blue Flag,” “Yankee Doodle,” and other familiar tunes. The concert prompted a brief but cordial visit to the Federal side of the stream by several men under cover of a flag of truce.29

In Nashville, Granger encountered difficulty in accomplishing his two most critical tasks. First, he had to maintain control of the growing territory in the army’s rear. The departure of Dick’s brigade added McMinnville to the list of places needing protection. Rosecrans had wanted the Fifth Iowa Cavalry regiment to move from Murfreesboro to McMinnville, but Granger protested that such a move would leave the railroad without mounted protection. In response, Rosecrans lectured his Reserve Corps commander as if he were a green lieutenant, specifying exactly how the Fifth Iowa could be divided to handle both tasks. As for McMinnville, Rosecrans was clear: “You must take care of McMinnville. It is too important for us to lose; see to that.” Such a message from Rosecrans spoke volumes about both men and their relationship. If Granger was passive and unimaginative in managing the army’s sprawling rear area, Rosecrans was overly immersed in micromanaging that same area. Compounding the problem was James Spears, the controversial officer Rosecrans had foisted upon Granger for command of the McMinnville garrison. Spears was so hated by the loyal Tennessee units at McMinnville that twenty-seven officers petitioned Rosecrans for his transfer. To their chagrin, Rosecrans adamantly retained Spears in command. As for Granger’s other principal task, the protection of the Stevenson base, Granger had momentarily left that to Morgan’s Second Division. Morgan and Tillson’s First Brigade were at the broken Flint River bridge, between Huntsville and Stevenson, while Daniel McCook’s Second Brigade was mostly gathered at Athens, Alabama. Rosecrans wanted Tillson’s command to relieve King’s brigade at Stevenson, but Morgan demurred until McCook’s troops could reach Huntsville. On 3 September neither Tillson nor McCook moved at all, and one of McCook’s regiments was still at Columbia. The urgency much in evidence at Bridgeport and Shell Mound was nowhere to be seen in Granger’s Reserve Corps.30

Around midnight Rosecrans reported to Halleck that the Bridgeport trestle had been repaired, most of the army was across the river, and that Valley Head, Winston’s Gap, and Rawlingsville had probably been seized. In fact, only cavalry had reached Valley Head because of the pause ordered when the Bridgeport trestle fell. Nor had Rawlingsville or Winston’s Gap been gained by that time. As for the bulk of the army being across the river, at the time Rosecrans wrote only nineteen of the army’s thirty infantry brigades were on the east bank with two more in the midst of crossing. In contrast, four of the army’s five cavalry brigades were finally beyond the river. There was a small note of concern in the message: “Have you any news from Burnside, any reason to think forces will be sent from Virginia to East Tenn, any that Johnston has sent any force up this way?” Still, according to Rosecrans, the plan was being executed essentially on schedule. Garfield was equally sanguine, writing a friend, “If I live through this campaign I now think I shall go to Congress. I am inclined to believe there will be work of great importance before that body, and if our campaign and that of the other armies are successful, the work of fighting will be substantially ended.” Less sure of success was Pvt. Baldwin Colton of the Fifteenth Pennsylvania Cavalry regiment, who told his father, “A man was telling me yesterday that Rosecrans told his regiment he hoped they would all be home Christmas. I am sure it will not be before spring and likely not then.” Rosecrans was indeed optimistic about the campaign just beginning. In preparation for leaving Stevenson, he arranged to have one of his horses, an accompanying servant, and a favorite saddle transported to Cincinnati. At the same time, Goddard ordered the Alabama House Hotel to be emptied so that a contractor could fill it with railroad workers. Even after the Army of the Cumberland moved on, the railroad lifeline would have to continue to function without fail.31

Much of Rosecrans’s optimism can be ascribed to intelligence reports collected by Capt. David Swaim. On 3 September Swaim recorded the testimony of one John Sherlock. Sherlock had been dispatched from Winchester on 7 August with orders to penetrate Confederate lines. Establishing himself at his grandmother’s house fifteen miles south of Chattanooga, he dispatched a disabled former Confederate soldier into town to gather information. All went well until 21 August, when a patrol led by Sherlock’s brother-in-law surrounded the house where Sherlock and a deserter were eating dinner. The deserter was shot and killed, but Sherlock escaped to Lookout Mountain. Sustained by another Union family, he continued to receive information from his informant until 30 August, when he began his return to Federal lines. Crossing the river at Shell Mound, Sherlock reported directly to army headquarters. First, he described a conversation with Confederate artillerymen grazing horses in McLemore’s Cove. “They all said the South was whipped and that the soldiers wouldn’t fight to do any good any more.” Next, his informant “learned that it is Braggs intention to fight if the Federals crossover at Chattanooga but if they cross at Shellmount & advance by way of Chattanooga Valley over Lookout Mountain through Stevens Gap aiming to cut him off from Dalton & Rome that he will fall back to Dalton & fight there.” Sherlock correctly located the positions of Bragg’s two corps but placed Confederate effective infantry strength at only 16,000 men. He mistakenly reported that Bragg had received no aid from either Johnston or anyone else but correctly identified the movement of Stewart’s Division to Loudon. Another statement was equally intriguing: “The secesh soldiers I heard talk said there would not be a fight at Chattanooga because the d——d Yankees would not come out and fight them fair, but try to surround & cut them off as they always did.” Sherlock’s report dovetailed with those of recent deserters, reinforcing Rosecrans’s natural optimism.32

Just as Rosecrans relied upon agents like John Sherlock, Bragg also used “scouts and spies” to determine Federal movements and intentions. By the morning of 3 September Bragg’s headquarters in Chattanooga had received new reports from the cavalrymen he had dispatched in haste on the previous day. Both Wharton and McDonald sent reports to Chattanooga. The messages, no longer extant, apparently contained no information useful enough to be recorded in Brent’s headquarters diary. More informative was a report from Maj. Pollok Lee, sent by Bragg to provide an independent source of news from Wheeler’s cavalry. According to Lee, three Federal cavalry regiments and an infantry brigade were at Cash’s Store on Sand Mountain, equidistant from Caperton’s Ferry and Winston’s. Another report, from an unknown source, placed three Federal infantry brigades moving toward Trenton from Caperton’s. No word came from Trenton itself, because Mauldin’s detachment had been ordered by Wheeler to withdraw northward toward Wauhatchie. The lack of definite information on Rosecrans’s movements troubled Brent: “Altho’ a week has elapsed, we have little or no information concerning him. The passes of Sand Mountain are not guarded, & the enemy may get into Will’s Valley & occupy Lookout before we are informed of his movement.” Unaware that the Federal advance had been delayed at least twenty-four hours because of the failure of the Bridgeport trestle, Brent feared that a rapid Federal advance would soon wash over Lookout Mountain into the Confederate rear. He continued, “It is easy to see that if Rosecrans crossed the River on Friday, Saturday & Sunday last in force, that he may by a rapid move place himself on our rear before we know it. Is the movement on our left a feint or not? No one as yet has been able to answer.” Bragg’s thoughts on this day are unrecorded. He might have been just as concerned as Brent, but without a clearer view of the situation, he did not dare order the Army of Tennessee into motion.33

While they awaited more information, Bragg prepared the army for either movement or action. First, he requested a report from all corps commanders on the strength and location of their outposts. As for the Western & Atlantic Railroad, Bragg ordered Inspector General Beard to closely inspect the railroad guards stationed along the line. McDonald’s Eighteenth Tennessee Cavalry battalion was released from its temporary duty in Lookout Valley and ordered to rejoin Forrest’s command. Similarly, Rice’s company of the Third Confederate Cavalry received orders to rejoin its parent command. As for Forrest himself, his stock was momentarily ascendant at army headquarters, especially when compared to Wheeler’s lackluster performance. Bragg now officially placed Buckner’s cavalry directly under Forrest’s command. Forrest thus became a corps commander, leading his old division, now under Frank Armstrong, and John Pegram’s Division from Buckner’s command. Along with the new command came an order to picket the Tennessee River in front of both Hill’s and Buckner’s Corps. Knowing that his army was too small to meet Rosecrans’s force on equal terms, Bragg also cast about for men to bolster his ranks. He called upon Gideon Pillow, the regional conscription officer, to “send us all the men you can, we need them.” At the same time, he recalled the Ninth Tennessee Cavalry regiment, which had been assisting Pillow in scouring the backcountry for deserters. In anticipation of using the thousands of Confederates paroled at Vicksburg in July, he sent Col. Joseph Jones, his senior aide, to select a camp outside Atlanta where they could be assembled. Those men could not be returned to action until formally exchanged, but Bragg anticipated that they would be available soon. For those troops already on hand but without arms, Ordnance Chief Oladowski directed the issuance of 760 guns to Polk’s Corps and 500 to Hill’s.34

Neither Polk nor Hill assisted Bragg in divining Federal intentions on 3 September. While formally cordial, Polk despised the army commander and ventured no advice unless required to provide it. He did, however, respond to Bragg’s query about the location of his outposts. Hindman’s Division near Rossville guarded the main road through Missionary Ridge to points south, Smith’s Brigade covered Chattanooga Valley, and Strahl’s Brigade on the northern toe of Lookout Mountain blocked the roads to both Trenton and Shell Mound. Late in the day Strahl forwarded to Polk news from scouts that a Federal column estimated at 40,000 men was crossing Sand Mountain and heading southwest in Wills Valley. Strahl reported, “None coming in this direction.” This information eventually reached army headquarters but apparently was forwarded by Polk without comment. The army’s senior corps commander thus remained a passive observer only. In contrast, Hill at least shared his thoughts with Bragg. In Hill’s opinion, the Federal goal was to secure East Tennessee by gaining control of the region’s railroads. He anticipated that Rosecrans would advance northward in Wills/Lookout Valley until he controlled the railroad into Chattanooga from the west, while Burnside held the line from Knoxville. Hill thought that Chattanooga was being spared destruction because the Federals wanted to seize it intact. He expected a concerted movement by Rosecrans, Burnside, and Grant in order to achieve their objective. He concluded, “I know the country too imperfectly & have too little confidence in my own judgment to counsel any particular course of action but I have felt so uneasy about the delay that I cannot refrain from expressing my anxiety.” At least Hill favored seizing the initiative to disrupt the Federal timetable. Bragg, of course, had already reached the same conclusion. The only question remaining was the all-important one of correctly timing the Confederate riposte.35

For the men in the ranks, 3 September was a day of increasing tension. In Polk’s Corps soldiers spread rumors that only one of Rosecrans’s divisions had crossed the Tennessee River. Prayer meetings continued in the Eighteenth Tennessee Infantry regiment of Smith’s Brigade, as they did in other units across the army. In Hindman’s Division, heavy details went to Chattanooga to work on a magazine. Hindman himself toured the camps to gauge the division’s morale. Apparently there was considerable work for Hindman to do, as Pvt. Marion Brindley explained to his sister: “There is much despondency in the army, many deserters and many others feeling whipped and ready to desert.” Yet Brindley was not one of them: “I do not despair of final success. When I do I shall be willing to die the death of a martyr upon any battle field on Southern soil, subjugated, I have little desire to live, at best, and when I die I have nothing to leave Mary and Luta better than the ashes of a fallen patriot on some blood-stained battle field.” In Hill’s Corps, resolve seems to have been equally strong among the troops, although a few took refuge in whiskey. Ordnance Sgt. Robert Bliss defended Bragg, who “has been the Atlas whose shoulders had to bear mountain loads of ridicule, contempt and criticism from the press, stay at home generals and dispirited soldiers … and when Mr. Rosecranz crosses the Tennessee let him learn that he does not ‘catch a tartar.’ These are the general opinions current.” Equally confident of victory was Capt. Bryan Marsh, though his reasoning was somewhat different. To his wife, “Mit,” he wrote, “We are confident that we will teach Rosey a lesson should he cross the river. Gen Brag will be compelled to fight this time no chance to run.” Like Private Brindley, Captain Marsh was willing to sacrifice his life for the cause: “When I think of the treatment of the wimen and children in Middle Tenn by the cowardly curs I am willing to undergo any deprivation on my part and rather than to submit let me dy and near see the only ones on earth that I love again.”36

Confederate activity on 3 September centered on consolidation of units. Cleburne’s Division continued to withdraw from positions along the river and trudge through the choking dust toward Harrison. Quartermaster Sergeant John Sparkman wondered what it meant: “I do not understand the movements but things look to me like we will retreat soon. I yet have hopes that we will come out of this thing well.” At Tyner’s Station, Breckinridge’s stragglers continued to reach camp, as did Marcellus Stovall. The new arrivals were in poor shape according to a Florida officer: “Our men are in a sad condition so many ragged & barefoot and it is very hard to walk over these rocky roads without good shoes.” In Walker’s Division, also at Tyner’s, Claudius Wilson warned his wife: “Should the fight commence before I get time to write you again I will telegraph you & if I am wounded, will try to get to Atlanta where you must meet me.” At Charleston, thirty-three miles from Tyner’s Station, Buckner also consolidated his command. That day he formally merged Stewart’s and Preston’s Divisions into a corps and exhorted the soldiers to “discharge the duties of patriots and of men.” During the afternoon Buckner sent Gracie’s and Kelly’s Brigades westward several miles to Georgetown and planned to follow them with Trigg’s Brigade as soon as Stewart organized his transportation. He also notified Pegram that his cavalry division had been assigned to Forrest’s command. Having recently passed through territory untouched by foraging soldiers, Buckner’s men were eating well and in high spirits. According to Lt. Quintus Adams, “The Army of Tennessee so far as I have seen is in excellent condition and capable of rendering the most efficient service, and if we should have a passage at arms during the fall I can not but anticipate the most splendid results to our arms.” Ominously, both Buckner’s and Forrest’s recent movements were reported openly in the Memphis Daily Appeal on the same day, under the byline “Ashantee,” a pseudonym for reporter John Linebaugh.37

Bragg’s cavalry remained in disarray on 3 September. On the army’s right, Forrest’s newly minted corps was beginning to establish a screen for Hill’s and Buckner’s infantry. Armstrong’s Division slowly replaced Cleburne’s pickets from the village of Harrison northward toward Blythe’s Ferry. James Wheeler’s Brigade (formerly Armstrong’s) occupied the river frontage around Harrison, with Dibrell’s Brigade extending the line to Wheeler’s right. Meanwhile, Pegram’s Division remained scattered. In addition to the division, Pegram retained command of his old brigade pending the arrival of a new brigadier. He stretched his brigade along the Hiwassee River toward Blythe’s Ferry, shielding Preston’s infantry at Georgetown. Col. George Hodge’s command, four small Kentucky and Virginia battalions now added to the division, protected Charleston. A Confederate congressman from Kentucky and a prominent supporter of President Davis, Hodge had recently arrived from Richmond. Scott’s Brigade was still making its way to Charleston after burning the Loudon Bridge. With Hodge a novice and Scott unalterably opposed to Pegram, the division lacked cohesion. In Wheeler’s corps, the main problem was not cohesion but lack of urgency in executing Bragg’s orders. Wheeler had instructed Wharton on 2 September to send only one brigade by “easy marches” to Alpine, Georgia, a tiny settlement in Broomtown Valley at the eastern foot of Lookout Mountain. Alpine lay on the road from Winston’s to Summerville and, ultimately, to Rome. Wharton apparently chose Crews’s Brigade, because Harrison’s Brigade remained at LaFayette all day on 3 September. Meanwhile, most of Martin’s Division was still straggling forward in small groups to a concentration point northeast of LaFayette. At the same time, under Wheeler’s orders, Mauldin’s detachment evacuated Trenton and formed a new picket line in the northern end of Lookout Valley. Satisfied with his deployments, which left Lookout Mountain mostly uncovered, Wheeler apparently remained in Chattanooga, for unknown reasons.38