16

BRAGG LEAVES TOWN

» 7–8 SEPTEMBER 1863 «

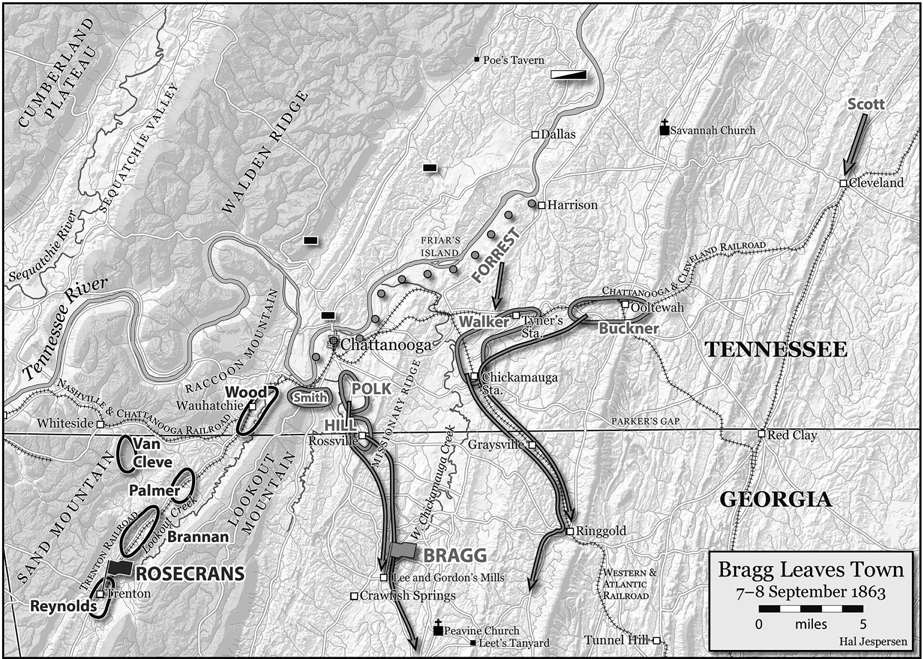

Monday, 7 September, found most of the Army of the Cumberland scattered for more than thirty miles along the narrow trench of Lookout/Wills Valley. Behind the Federals frowned the massive bulk of Sand Mountain, separating the army from its base at Stevenson. In front, stretching north and south as far as the eye could see, Lookout Mountain completely cloaked Bragg’s army from prying eyes. At Trenton, Rosecrans needed to assess the situation quickly and energize his widely separated corps. On the left, Crittenden’s Twenty-First Corps was to threaten Chattanooga directly from the north end of Lookout Valley. On the right, Stanley’s Cavalry Corps, backed by McCook’s Twentieth Corps, was to drive eastward beyond Lookout Mountain toward Rome and ultimately the Western & Atlantic Railroad. In the center, Thomas’s Fourteenth Corps was to seize a passage over Lookout Mountain while maintaining contact with Crittenden’s and McCook’s units. If the plan succeeded, Bragg would evacuate Chattanooga without a fight and withdraw toward Atlanta. In some respects, Rosecrans’s scheme resembled his successful Tullahoma campaign. At Tullahoma, Rosecrans had turned Bragg’s right; now, with any luck, he would turn Bragg’s left and pry the Confederates out of their mountain stronghold. The key to success would be synchronized action. First, Crittenden would have to maintain his threatening posture toward Chattanooga to fix Confederate attention in the north and provide intelligence on the Army of Tennessee’s location. Second, Thomas would have to surmount Lookout Mountain in at least one place where a road led downward into the valley beyond. Finally, Stanley would have to cross Lookout Mountain quickly in order to mount a credible thrust toward Bragg’s supply line. Backed by the power of McCook’s infantry, Stanley’s cavalrymen would thus play the key role in forcing a Confederate retreat from Chattanooga. Even though not all of his army had yet completed its painful journey over Sand Mountain, it was time for the next phase of Rosecrans’s campaign to begin.1

Following his normal routine, Rosecrans kept his staff working into the early morning hours of 7 September, even though their trip over Sand Mountain had been exhausting. Around 3:00 A.M., a message arrived at Trenton from the Twenty-First Corps. Dispatched by Capt. John McCook of Crittenden’s staff at 12:15 A.M., the message included copies of Wood’s messages of 2:00 and 4:00 P.M. the previous day. In both messages Wood had considered his position at Wauhatchie “hazardous.” McCook stated in Crittenden’s name that he would “await further advice from you before ordering him [Wood] to advance.” Perhaps it was simply the lateness of the hour or the rigors of a long day, but McCook’s seemingly innocent message caused Rosecrans to fly into a rage. Displeased that the Twenty-First Corps was apparently not going to move without more prodding, Rosecrans instructed senior aide Frank Bond to write Crittenden at 3:15 A.M.: “The general commanding directs that you order General Wood to make a reconnaissance in force, as was intended by the order sent through General Garfield.” Also irked that McCook, not Crittenden, had signed the note, even though McCook indicated he was acting under Crittenden’s instructions, Rosecrans specifically rebuked Crittenden for not placing his own name on the messages. Again speaking for Rosecrans, Bond wrote, “He also directs me to say that all communications for him from your headquarters must be signed by the general commanding the corps.” Probably aware that Captain McCook was the younger brother of Alexander McCook, Rosecrans chose to have Bond sign the rebuke. Clearly, Crittenden must follow army protocol to the letter, but Rosecrans believed himself unfettered by the same rules. Taken by itself, this seemingly insignificant episode would have mattered little in a long campaign, but it was indicative of larger issues that would resonate in the future: Rosecrans’s increasing irascibility and his growing mistrust of Crittenden’s competence.2

Rosecrans’s rebuke reached Crittenden on Sand Mountain a little before 5:00 A.M. and triggered immediate action. Mortified that he had displeased the army commander, Crittenden attempted to get Wood moving. His staff dutifully forwarded to Wood Garfield’s original message of 11:30 P.M., 6 September, calling for Wood “to feel the enemy at the point of Lookout Mountain, and find out certainly what he is doing.” Further, Wood was to waste no time in making the reconnaissance. At 9:15 A.M., Crittenden told Garfield that he had ordered Wood forward upon receipt of Bond’s message. He also abjectly apologized for the lapse in staff protocol: “I acknowledge the correctness of the reproof, and it shall not occur again, be I well or ill, sleepy or wide awake, in or out of bed.” Believing that he had satisfied Rosecrans, Crittenden now waited to hear from Wood. At approximately 8:00 A.M., Wood received Crittenden’s order, as well as the copy of Garfield’s original instructions. The packet did not include Rosecrans’s explicit order of 3:15 A.M., probably because that order was incorporated within Rosecrans’s embarrassing rebuke to Crittenden. Thus Wood did not know of Rosecrans’s displeasure or his peremptory directive to “make a reconnaissance in force,” far stronger language than Garfield’s more benign phrase “to feel the enemy.” Crittenden’s instructions placed Wood in a quandary. In his opinion, he already had felt the enemy on the previous day, risking his two brigades in a dangerous position at Wauhatchie for many hours without the possibility of support. Now Crittenden had ordered him to return to that “hazardous” position and beyond it in order to learn what he already knew and had already reported. Without knowledge of the language in Rosecrans’s 3:15 A.M. message, which gave Crittenden no option, Wood saw Crittenden’s order as an extreme interpretation of Rosecrans’s wishes. The more he thought about it, the more Wood believed his superiors did not understand what he faced. Otherwise they would not have sent him such an order.3

Before advancing, Wood spent several hours selecting defensive positions for his two brigades. While doing so, he decided to remonstrate with Crittenden once more about the reconnaissance. For Wood, the key point was the lack of support for any advance he might make. Crittenden had earlier suggested that Van Cleve’s division could assist Wood, but Van Cleve’s men were scattered along the Murphy’s Hollow Road on their way up Sand Mountain from Whiteside. If the Confederates attacked him, Wood believed the fight would be resolved long before Van Cleve could intervene. Thus, Wood argued that Palmer’s division should move north in Lookout Valley to within two miles of Wood’s rear and support his advance. Crittenden had already rejected Wood’s request because it did not conform to the original orders from army headquarters. Having served with Crittenden for more than a year, Wood was well acquainted with his indecisiveness, inflexibility of mind, and literal interpretation of orders. He saw no need for Crittenden to be bound by specific locations identified in the operations order that was by now four days old. As a professional soldier, Wood was confident that a small deviation from the original order fell within Crittenden’s discretion. Thus he vigorously pressed for his proposal in a long and strongly worded message to Crittenden at 11:30 A.M. One sentence leaped out: “I cannot believe General Rosecrans desires such a blind adherence to the mere letter of his order for the general disposition of his forces as naturally jeopardizes the safety of the most salient portions of it, and certainly cripples the force and vigor and accuracy of its reconnaissances.” Wood gratuitously suggested that if Crittenden did not feel comfortable making the decision on Palmer alone, he should appeal to Rosecrans personally for permission to act. Finally, Wood stated that although he had already made a reconnaissance on the previous day, he would send a brigade northward in accord with Crittenden’s instructions.4

Wood selected Harker’s Third Brigade to make the reconnaissance. Harker led the brigade forward around 1:00 P.M. and soon reached the Wauhatchie railroad junction. Wood had ordered Harker to advance to Lookout Creek, directly under the tip of Lookout Mountain, if possible, but to go no farther. Not far beyond Wauhatchie, he encountered cavalry pickets, who retired precipitately. Covered by a heavy skirmish line, Harker continued forward until he met infantry pickets, which also fell back. A few hundred yards farther, the brigade reached the substantial home of Elisha Parker, seventy-three. There the road forked, the right-hand fork following the Nashville & Chattanooga Railroad northeast to a crossing of Lookout Creek, while the left-hand road continued northward before turning east to another crossing. Choosing the right fork, Harker pushed his skirmish line to the bank of the creek but held the remaining troops just in front of Parker’s house. Suddenly, several Confederate cannon opened with a crash on Harker’s troops. For at least fifteen minutes the Confederate gunners rained uncomfortably accurate fire on Harker’s men from the lower slope of Lookout Mountain. Hindered by many shells that did not explode, the Confederates drew little blood. Still, Cpl. Herman Beitel of Company F, Sixty-Fifth Ohio Infantry regiment, was killed instantly when a shell fragment took off the top of his head. Shortly thereafter, Harker decided to rejoin Buell’s First Brigade in the rear at the mouth of Running Water Canyon. Before leaving, he interviewed Elisha Parker, who claimed to hold Unionist sympathies. Parker indicated that only Strahl’s Brigade was in Harker’s immediate front but that many more Confederates were nearby. A prisoner also indicated that Bragg had received heavy reinforcements from Mississippi and South Carolina. Having added only marginally to their store of knowledge, Harker’s soldiers slowly withdrew from Lookout Creek and Wauhatchie, carrying Corporal Beitel’s body with them.5

During the day, Crittenden remained at his headquarters atop Sand Mountain. There he overheard someone mention in exaggerated terms Wood’s slight withdrawal from Wauhatchie during the previous night. Crittenden claimed that the news came from one of Wood’s staff officers who had arrived at corps headquarters early that morning, but Wood would later deny that any of his staff had been there that day. The incorrect information probably came from a member of the Thirty-Ninth Indiana Mounted Infantry regiment who had accompanied Wood’s division. Already embarrassed by Rosecrans’s rebuke, Crittenden became angry at the fact that Wood had not told him of the slight withdrawal, again placing him in Rosecrans’s bad graces. In late morning Crittenden sent Lt. Col. Lyne Starling, chief of staff, and Maj. John Mendenhall, chief of artillery, to survey the Trenton Road all the way to Wood’s position. During their absence, Wood’s 11:30 A.M. message arrived. Not only did it confirm Wood’s withdrawal from Wauhatchie and his delay in initiating the second reconnaissance, it also contained the inflammatory wording about “blind adherence to the mere letter” of orders. His earlier anger instantly rekindled, Crittenden heatedly composed an emotional message to Garfield. In it he charged that Wood had “neglected his duty” by delaying Harker’s reconnaissance, had endangered his command by withdrawing on the Trenton Road instead of the Whiteside Road, and had been slow to report the skirmishing on the previous day. He told Garfield that he could send Palmer to Wood’s support but would not do so unless Rosecrans ordered it. No doubt pleased that he had exposed Wood’s malfeasance in high places, Crittenden directed that a copy of his message be sent to Wood. He seemed utterly unaware of how his whining message might be perceived at Rosecrans’s headquarters.6

During the afternoon the controversy continued to boil. At some point Starling and Mendenhall returned from their excursion to Wood’s position. What they reported is unknown, but before the day was over, Crittenden ordered Palmer to move to Wood’s support at 3:00 A.M. on the next day. About the same time that Crittenden’s order seemingly vindicated Wood’s analysis of the situation, Wood received his copy of Crittenden’s heated 2:00 P.M. message to Rosecrans accusing Wood of serial errors of judgment and dereliction of duty. Outraged, at 6:00 P.M. Wood began drafting a scathing response to Crittenden’s charges. When Harker returned, Wood paused long enough to report the results of the reconnaissance but soon returned to his writing. Completing the 3,500-word missive shortly before midnight, Wood addressed it to Garfield and forwarded it, as protocol required, through corps headquarters. In the message Wood first explained that his “blind obedience” reference applied only to the army operations order, not the order for a reconnaissance. Second, he denied that he had delayed Harker’s reconnaissance unnecessarily, explaining that he had been forced to protect his remaining troops before sending Harker forward. Third, he expended many words in explaining why he had withdrawn from Wauhatchie during the previous night. He took full responsibility, arguing passionately that the security of his command was enhanced by the move. Last, Wood admitted that Crittenden’s charge of imprecise messages on 6 September was correct but was simply an “unintentional oversight.” He then attacked Crittenden’s apparent reliance upon staff officers of limited experience instead of a professional soldier like Wood. Believing that his honor and professionalism had been called into question, Wood closed by apologizing for the length of his missive and appealed to army headquarters for justice. Given the cascade of words he sent at 11:50 P.M. to Twenty-First Corps headquarters, he must have known the episode would not end there.7

While Wood and Crittenden traded charges and countercharges, the remainder of the Twenty-First Corps idled in its camps. In Palmer’s Second Division, Cruft’s and Grose’s men continued to occupy the pleasant camping grounds around Cole’s Academy. Similarly, Van Cleve’s Third Division sprawled beside the Murphy’s Hollow Road on both sides of Murphy’s Spring. While some men foraged for corn, others took the opportunity to write letters home. In late morning Cruft sent the thirty-five men of Company K, Thirty-First Indiana Infantry regiment, to scale Lookout Mountain and establish a signal station. The Hoosiers found a track that led up the mountain to what the locals called Nickajack Gap. As they ascended, they found Confederate pickets in large numbers and a sharp skirmish erupted. After losing one man wounded, signal officer Julian Fitch called for assistance while Company K withdrew. In response Cruft sent two regiments to the base of the mountain but soon recalled them to their original camps. Little had been gained except the knowledge that a rough track existed over Lookout Mountain at Nickajack Gap. Even less occurred to break the monotony in Van Cleve’s command, tucked away in Murphy’s Hollow. Foraging opportunities were fewer there, so the men amused themselves by writing letters and rolling rocks down the mountain. A few thought they could hear artillery fire, but they were uncertain of its location. With Wood no longer covering the Running Water Canyon road, Van Cleve assigned the Twenty-First Kentucky Infantry regiment of Barnes’s brigade to garrison Whiteside. Far behind them, Dick’s Second Brigade finally reached Bridgeport, crossed the river, and camped just beyond the stream. Late in the day, Palmer’s division had a distinguished visitor—the army commander. Riding up from Trenton with part of his staff, Rosecrans visited with the men around Cole’s Academy. Although he made it as far as Cole’s Spring, where he talked with Brannan around 7:00 P.M., Rosecrans apparently did not ascend Sand Mountain to speak with Crittenden before returning to Trenton.8

South of Trenton, on 7 September Thomas’s Fourteenth Corps consolidated its position in Lookout Valley and began its assault on Lookout Mountain. Leading the way was Negley’s Second Division, whose probe of the previous day had met resistance. Now Negley advanced in strength, with Beatty’s First Brigade leading the division up the mountain. At 9:00 A.M. Beatty began the ascent with two regiments. The two units met no Confederates, their only opposition being the steepness of the grade. At noon Beatty started his remaining regiments up the mountain, along with two guns. Negley followed Beatty with part of Stanley’s Second Brigade. Any Confederate pickets who might have been watching the Federals sweating their way up the mountain chose not to reveal themselves. Around 11:00 A.M. Beatty’s Fifteenth Kentucky Infantry regiment reached the crest unopposed and found Lookout to be, like Sand Mountain, mostly flat on top. Negley himself arrived around noon and remained for several hours. He sent patrols several miles to the east and expedited the arrival of the remainder of Beatty’s and Stanley’s men. At a crossroads two miles beyond the crest a few Confederate cavalrymen appeared, but they made no effort to interfere with the Federal occupation of the road junction. Far below, in Johnson’s Crook, Stanley’s Eighteenth Ohio Infantry regiment began the arduous task of assisting the division’s wagons up the mountain. The day was warm, broken only by the briefest of afternoon showers that did virtually nothing to tamp down the dust. Behind the Eighteenth Ohio, Sirwell’s Third Brigade advanced only to the foot of the mountain. Returning to the valley at 5:00 P.M., Negley reported his success to corps headquarters at Brown’s Spring. He also requested a cavalry detachment to serve as couriers and funds to purchase information from the locals. Lacking those resources, he had been forced to use infantrymen to carry messages and had used his own money to reward informants. During the day, Thomas received the Ninety-Second Illinois Mounted Infantry regiment of Wilder’s command, but he assigned it to Reynolds, not Negley.9

Negley’s thrust up Lookout Mountain was only the tip of the spear represented by the Fourteenth Corps. Behind Negley’s infantry were hundreds of wagons ready to begin the backbreaking pull up the grade. While awaiting his turn, teamster William Christian found time for a little sightseeing: “I went down to the iron works just off the main road. I went into a deserted house there and found a black man who said he had the small pox. I left mighty sudden.” By the end of the day, the road behind Negley’s trains was clogged with more troops. Baird’s First Division had been ordered to follow Negley’s command, but he was delayed all day by wagons in front. Baird began the day still on Sand Mountain, but he hastened Scribner’s First Brigade down to the valley floor at Brown’s Spring, then after only a brief rest, hurried it on in Negley’s wake. Scribner closed on Negley’s rear well after dark. Behind him, Starkweather’s Second Brigade was only able to negotiate the descent of Sand Mountain to Brown’s Spring. Its progress was hindered by many broken wagons and the requirement to guard a large herd of beef cattle moving with Baird’s division. Behind Baird, Reynolds’s Fourth Division continued to occupy Trenton, a settlement of “two churches, three stores, court-house, mill, and blacksmith shop.” Ordered to relieve one of Negley’s units left to grind corn at Payne’s (Sitton’s) Mill, Reynolds dispatched King’s Second Brigade to do that and guard the Empire Iron Works several miles south of Trenton as well. In addition, Reynolds was told to send a brigade up Lookout Mountain to secure Frick’s Gap. With only Turchin’s Third Brigade remaining in Trenton, Reynolds promised to send Van Derveer’s Third Brigade of Brannan’s Third Division to seize the gap early the next day. Van Derveer’s troops were just then descending Sand Mountain to join the remainder of Brannan’s division at Cole’s Spring several miles north of Trenton. Van Derveer began to prepare for what he considered a most dangerous mission, but when Rosecrans arrived around dark, he canceled the brigade’s participation on the spot.10

South of the Fourteenth Corps, in what was arguably the most critical sector of Rosecrans’s campaign plan, there was little activity on 7 September. David Stanley had been told repeatedly that his thrust over Lookout Mountain toward Rome and Bragg’s supply line was critical to the success of the campaign. He had procrastinated, never refusing to move but offering a series of excuses that amounted to the same thing. On the previous night, Garfield had sent Stanley the clearest order yet to begin the operation, yet Stanley continued to sit. At 10:30 A.M. he responded with a curious message that reflected his inner turmoil. In it, Stanley announced that he would begin the raid on the following day but stated baldly that he had little hope for success. He had asked for Minty’s brigade to join him, but that had been denied, leaving him with only thirteen regiments. Stanley thought his corps was utterly inadequate for the task: “My force is so small that I cannot make proper detachments for striking the road and at the same time fight the force of the enemy.” In Stanley’s opinion, he faced two full Confederate cavalry divisions, who would probably deny him the half day he needed on the railroad to wreck it effectively. Success could only be assured if Minty joined him and Wilder mounted a diversion toward Chattanooga at the same time. Knowing that those two conditions were not likely to be met, Stanley feared the outcome. Still, he offered, “I will do the best I can.” Dispatching the message to Trenton by courier, he ordered McCook and Crook to put their regiments in fighting trim for an early start on the next day. In Long’s brigade, the Second Kentucky Cavalry regiment arrived with the brigade train, giving Stanley a fourteenth regiment. A detachment of the Fourth Ohio Cavalry regiment, sent up Lookout Mountain to chase bushwhackers, was recalled from its fruitless errand. Suddenly, another order came from Stanley’s headquarters: the movement ordered for the next day was canceled!11

Until Stanley departed on his raid, Alex McCook’s Twentieth Corps could do nothing but wait. As he had for several days, McCook continued to enjoy the grudging hospitality of William Winston, even as Winston’s plantation was stripped of all food and fence rails. McCook’s headquarters was surrounded by the camps of Davis’s First Division. On top of the mountain, elements of Carlin’s Second Brigade protected the rough, winding route back to the valley. Carlin’s perimeter extended a short distance to the east, where a branch of the Little River passed over the spectacular DeSoto Falls into a rock-lined basin. Beyond the falls, foragers seeking ripe fruit trees found not only an orchard but also a larger force of Confederates. Before they could disengage, Pvt. Elisha Stroud was killed and several of his compatriots captured. Clearly, danger lurked in the thickets atop Lookout Mountain. For the bulk of the Twentieth Corps, however, 7 September was spent pleasantly in Wills Valley. Bored men amused themselves by continuing the despoliation of Winston’s property. One soldier sent home an arrowhead he had acquired at his campsite, to be kept “among the curiosities.” Several miles north of Winston’s, Johnson’s Second Division was equally bored. As forage for their animals disappeared, and the stench from poorly constructed latrines grew, Johnson’s men moved their camps a short distance to escape the filth. The day was hot and dusty until a small but fierce thunderstorm cooled the air in midafternoon. The storm was barely felt by Sheridan’s Third Division as it toiled southward past the mouth of Johnson’s Crook. Sheridan began the march early, before the sun rose above Lookout Mountain. In the Eighty-Eighth Illinois Infantry regiment, Pvt. John Ely was transfixed as the light fell on Fox Mountain to the west, writing, “Oh I would like to stay here a day and drink in this beauty.” Sheridan halted early, with his division stretched from Stevens’s Mill northward to the plantation of Confederate officer James Nisbet.12

While his strike force at Valley Head dallied, Rosecrans’s deception force opposite Chattanooga grew increasingly nervous. Until the command of “U.S. Forces, Left Flank” was settled, Hazen dutifully relinquished that role to Wagner. Still, at 6:00 A.M., he addressed a note directly to army headquarters reporting large dust clouds on the far side of the river on the previous day and an unusual quiet along the river. Unlike Hazen, Wagner was unwilling to remain passive. Apprised of Wood’s operations in Lookout Valley on the previous day, Wagner had already sent two of his regiments down to the river. Now he sought to do more in support of Wood’s dangerous position. At 6:00 A.M. he informed Wood that he was increasing his force opposite Chattanooga to three regiments and a section of guns. Together, Wagner and Wilder controlled the area across from the large Williams Island, just downstream from Chattanooga. Wagner offered to join Wood at Williams Island, but Wood’s troops were unable to take advantage of the offer. At 10:00 A.M., Wagner informed army headquarters that Confederate cavalry had replaced the infantry pickets above Chattanooga and that the pontoon bridge on the Chattanooga waterfront had been broken up. In late morning he decided to distract Confederate attention by bombarding Chattanooga. Heavier than many of the previous bombardments, the shelling elicited no response. Upstream, Wilder sent the Seventeenth Indiana Mounted Infantry regiment to observe the ford at Friar’s Island, where he hoped to cross the next morning. Still farther upstream, as signs multiplied that the Confederates were leaving the line of the river, Hazen told Minty to attempt a crossing at Sale Creek on the next day. If successful, Minty should ride southward to meet Hazen’s troops in the vicinity of Harrison’s Ferry. Minty resisted, pleading his brigade’s weakness, and Hazen acquiesced. Although none of the Federals could yet be sure of what was happening, a consensus began to develop slowly that Bragg’s army might be leaving town.13

The quickening sense of urgency that gripped Rosecrans’s deception force also affected Granger’s Reserve Corps. During the day, Tillson’s First Brigade of Morgan’s Second Division finally entered Stevenson. Most of Daniel McCook’s Second Brigade passed through Larkinsville on the way to Bellefonte. Reaching the latter place, the band of the Fifty-Second Ohio Infantry regiment broke into patriotic airs to discomfit the citizens but was chagrinned to learn there was no audience in the abandoned settlement. A day’s march behind McCook, the Eighty-Sixth Illinois Infantry regiment finally crossed into Alabama and continued for another twelve miles. Beyond the Cumberland Plateau, Steedman put two of his three brigades into motion. Three regiments of Whitaker’s First Brigade left Estill Springs early for Decherd, where the fourth regiment joined. The united brigade then continued to Winchester, “a dreadfully stinken place,” and finally halted at Cowan for the night. Like Whitaker’s men, several regiments of Reid’s Second Brigade also headed for Cowan from Tullahoma and Shelbyville. Three of Reid’s regiments made it to Decherd for the night, while the fourth awaited them at Cowan. While his troops marched, Steedman himself took the train, where he encountered a detail from the Eighteenth United States Infantry regiment, returning from Nashville. The regulars had been drinking heavily and were very boisterous, but the general simply cautioned the detail’s commander to see that his soldiers did not injure themselves and returned to his own car without another word. Such empathy for those in the ranks endeared Steedman to his men. Elsewhere, several unattached regiments were also moving to the front. At Cowan, the Sixty-Ninth Ohio Infantry regiment received orders to head for Stevenson and report to the Reserve Corps. At Bridgeport, the Twenty-Second Michigan Infantry regiment, already under Reserve Corps control, awaited its new brigade assignment. Finally, on the Cumberland Plateau, the Eighty-Ninth Ohio Infantry regiment prepared to leave Tracy City and march to Bridgeport.14

At the end of the day, Rosecrans returned to Trenton after visiting Palmer’s and Brannan’s divisions. Uppermost in his mind was the necessity to get Stanley’s raid started. Having received Stanley’s tepid promise to move on the next day, Rosecrans instructed Garfield at 8:30 P.M. to encourage his reluctant cavalry commander with strong words of support. Claiming that most of the Confederate cavalry was not yet in Stanley’s front, Garfield expressed Rosecrans’s confidence that Stanley could succeed in his mission. He assured Stanley that McCook’s Twentieth Corps would advance several brigades beyond Lookout Mountain to hold the way open for his return. As he had done before, Garfield reiterated the importance of Stanley’s raid to the success of the overall campaign plan: “Even should you fail in thoroughly breaking the railroad, you would at least make a strong diversion in that direction.” At 8:45 P.M., Garfield wrote to McCook about his role in Stanley’s thrust. As was customary in communications with McCook, the instructions were detailed and specific. McCook was told to guard the route over Lookout Mountain with one brigade, while at the same time he was to push forward two additional brigades to occupy the hamlet of Alpine at the eastern foot of the mountain. Expecting Stanley’s raid to be of brief duration, Garfield instructed McCook to carry rations for only three days, with the mission probably lasting no longer than four. To prevent McCook from becoming nervous about his own isolated situation, Garfield shared the belief prevailing at army headquarters that Bragg’s army, estimated at 50,000 men, remained at Chattanooga. Although Garfield ascribed the information about the Confederates to Wood, the numbers actually came from deserters and scouts. The inference in both of Garfield’s messages was that there was still time to implement the bold dash toward Bragg’s supply line with little risk of failure.15

Although Stanley’s raid was on Rosecrans’s mind on the night of 7 September, he had other concerns as well. Part of the problem was the general lack of information reaching headquarters. When Crittenden forwarded Wood’s account of Harker’s reconnaissance, he drew a sharply worded retort that the report lacked specific details. A more friendly inquiry went to Thomas, asking if he had any “news,” particularly of Negley’s operations at Stephens’s Gap. The unsuccessful efforts during the day to extend the telegraph line from Whiteside to Trenton via Wood’s position were also troubling. A report from Granger that the Louisville & Nashville Railroad was not moving sufficient commissary supplies drew a strongly worded plea to President James Guthrie for better service. Increasingly agitated, Rosecrans flogged his staff, addressing minute items such as the state of repairs to a magazine in Nashville and the purchase of supplies for a Nashville hospital for “public women.” John King at Stevenson was told to accommodate Archbishop John Purcell of Cincinnati, who would soon arrive to visit the army. Finally, at midnight, Rosecrans crafted his daily report to Halleck. Perhaps it was the accumulated aggravations of the day, but he was in a foul mood by that time. Halleck’s most recent telegram had declared, “You give me no information of the position of Bragg and Buckner. If they have united, it is important that you and Burnside unite as quickly as possible, so that the enemy may not attack you separately.” For a weary army commander at a critical juncture in his campaign, Halleck’s gratuitous advice was unwelcome, and Rosecrans responded heatedly: “Your dispatch of yesterday received with surprise. You have been often and fully advised that the nature of the country makes it impossible for this army to prevent Johnston from combining with Bragg.” Because Burnside’s campaign had been mounted independently, by Halleck’s design, any problems that might have developed were Halleck’s fault: “Your apprehensions are just, and the legitimate consequences of your orders.”16

Just as Burnside’s activities in East Tennessee were a source of friction between Rosecrans and Halleck, so too were they problematic for Bragg and the Confederate government. On the previous day, Bragg had instructed Buckner to order the evacuation of Cumberland Gap, the order to be passed through Samuel Jones. Very reluctantly, Buckner had obeyed, but Jones had stayed the order until he received guidance from Richmond. Fundamentally misunderstanding what had happened during Burnside’s advance to Knoxville, Davis and Secretary of War Seddon ordered Jones on 7 September to use his own discretion in the matter. Seddon postulated that “Generals Bragg and Buckner probably acted on misinformation as to force threatening. You have better information and must exercise fully your own judgment.” Seddon also notified Bragg of Davis’s decision but softened the assessment from “misinformation” to “erroneous impression.” Indeed, Davis and Seddon believed that aggressive action by Jones could save both Cumberland Gap and the railroad to Chattanooga. Jones himself was equally ignorant about the status of Burnside’s invasion of East Tennessee. Before he heard from Richmond, Jones telegraphed Buckner that he was expecting to receive reinforcements. Thus augmented, he believed he could restore the status quo: “May be able to open communication to Knoxville. Perhaps you did not know condition of things when you telegraphed order in regard to Cumberland Gap.” That very morning, at his headquarters in Knoxville, Burnside wrote to Rosecrans’s aide Robert Thoms: “We have full possession of East Tennessee except Cumberland gap, which is still held by the enemy. I have a force moving against it from the Kentucky side, and I move from here at once in person with a force to attack it from this side. Will telegraph you from the gap, I hope.” Far more realistic in their appreciation of the actual situation, Confederate Railroad Bureau personnel completed their plans to send 18,000 troops from Virginia to Tennessee by way of the Carolinas.17

Upon the entreaties of Polk and Hill on the previous day, Bragg had suspended the evacuation of Chattanooga Valley. Now it was time to decide what to do next, and for that he needed more information. At 7:00 A.M. Brent instructed Inspector General Beard to send two officers into Lookout Valley to learn the position and strength of the Federal force lately at Wauhatchie. Bragg had already sent senior aide Joseph Jones to a signal station atop Lookout Mountain on the same mission but without result. Thirty minutes later, Brent notified Forrest that although the infantry movement was held in abeyance, Forrest should continue to assist Wheeler in developing information on the Federals in Wills Valley. At 9:00 A.M., Brent telegraphed Buckner at Ooltewah to have Hodge’s makeshift cavalry brigade probe the Federal column reportedly advancing on Charleston. Bragg continued to hope that Wheeler would soon report the results of the reconnaissance he had ordered two days earlier. Those hopes were dashed when a long message from Wheeler arrived from Alpine. In it, Wheeler complained that his force was too small to probe beyond Lookout Mountain to discover the strength and intentions of the Federals concentrated at Winston’s plantation. Although Wheeler claimed that the Federals were too strong for him to act, a contrary view was offered in a note from Pollok Lee, one of Bragg’s inspector generals. Earlier, Lee had been sent to provide an independent appraisal of Wheeler’s situation, and now he and Wheeler were at odds in their assessment. Thus Bragg learned nothing about what was happening in the southern reaches of the Lookout/Wills Valley corridor. Shortly after 11:00 A.M. shells began falling on Chattanooga. The noisy bombardment could do little damage because virtually everything of military value had long been moved out of range, but it was disconcerting nonetheless. In early afternoon, as the Federal shelling continued, Bragg resolved once more to evacuate Chattanooga, and he instructed Brent to prepare a new movement order.18

As before, the army would depart in two massive columns, with one significant change in the order of march. Originally, Polk’s Corps headed the westernmost column; now Hill’s Corps would lead the way. With Federals still active in northern Lookout Valley, Polk would have to block the road over the toe of Lookout Mountain while Hill departed Chattanooga Valley. Everything else was the same, with Walker leading the eastern column, followed by Buckner. The movement was slated to begin after nightfall. Because some units had arrived at Chattanooga without wagons and ambulances, Brent’s circular authorized Chief Quartermaster McMicken to seize wagons from any corps in order to ensure that all divisions shared the limited assets equally. After publishing the circular, Bragg and Brent turned their attention to the smaller units that would be at risk and to the cavalry screen that would cover the army’s retreat. Brent reminded Polk to withdraw the signalmen from Lookout Mountain, as well as the cavalry detachment protecting it. Col. Edmund Rucker, twenty-eight, commander of Rucker’s First Tennessee Legion from Pegram’s Division, was assigned to be Polk’s and Hill’s rear guard. As such, Rucker was given Mauldin’s detachment, as well as Allison’s Cavalry Squadron, and Company D of McDonald’s Battalion. Polk was to use this odd collection of mounted units to replace the infantry pickets from Smith’s Brigade when they withdrew after dark from their positions guarding Lookout Creek. With Forrest heading to assist Wheeler around Alpine, only Pegram’s command remained to serve as Buckner’s and Walker’s rear guard. Unfortunately, two of Pegram’s brigades were still fending off Burnside’s probes along the Hiwassee River, leaving only Pegram’s old brigade available. Except for Rucker’s command, most of Pegram’s men were still scattered along the Tennessee River upstream from Chattanooga around Harrison. Now they were to relieve Allison’s Squadron below Friar’s Island and hold their positions as long as possible before following Buckner’s infantry.19

Although sunset would not occur until 7:00 P.M., most of Hill’s Corps spent the afternoon pushing forward to the base of Missionary Ridge. First, Hill sternly admonished his officers: “The success of arms depends more upon celerity than any one thing else. To insure this quality in the corps, commanders of every grade will remain habitually with their commands and will give their personal attention to every movement.” The order mentioned no names, but certainly Breckinridge had been among those guilty of slack behavior the previous evening. Hill decreed that his corps would travel with six days’ rations, while sick soldiers and all baggage should be sent to the rear at once. Later, Hill issued another circular establishing the order of march. Cleburne’s Division would lead the column, followed by the corps trains, with Breckinridge’s Division bringing up the rear. An artillery battery was to follow Cleburne’s lead brigade and another to precede Breckinridge’s last brigade. Breckinridge was to notify Polk when his last unit was in motion. The requirement for officers to accompany their troops was reiterated: “The utmost efforts must be made to prevent the disgraceful practice of straggling. This can only be done by the greatest vigilance on the part of all officers and their habitual presence with the troops.” Thus chastised, Cleburne’s Division left Chattanooga and marched across the floor of Chattanooga Valley to the Rossville Gap in Missionary Ridge. In Breckinridge’s Division, Stovall’s Brigade was already in its assembly area, but Adams’s and Helm’s Brigades had some marching to do despite the day’s heat and dust. A detail from Helm’s Brigade was ordered to move the division’s baggage to Chickamauga Station. Lacking even a single wagon, the men went into the countryside to “press” civilian vehicles. Finding only one oxcart, the Kentuckians spent the remaining daylight hours shuttling back and forth over the two-mile route from their camp. Night found the detail at the depot with “mountains of baggage” but no train to move it farther.20

While Hill’s troops readied for an evening departure, Polk’s Corps waited patiently with folded tents and loaded wagons. In order to assist Breckinridge, Polk ordered his divisions to relinquish five six-horse wagons apiece. In addition, he detailed 150 men to load ammunition on railroad cars that evening. Polk’s staff drafted the corps movement order and distributed it to division commanders at 3:00 P.M. Cheatham’s Division would be the first to leave its camps in Chattanooga Valley, followed by Hindman’s Division, which was already near the Rossville Gap. The artillery and trains of the brigades would be distributed throughout the long column with their respective units. Brigade ambulances were to be gathered into division ambulance trains following each division. Provost guards were to police the column, arresting stragglers and keeping unit intervals tightly closed. Surgeons were to examine all stragglers “and see that none loiter or fall out except those with proper certificates or permits.” With Chattanooga and the upstream fords now picketed by Pegram’s cavalry, the only infantry units in contact with the Federals during the afternoon were Polk’s. At the toe of Lookout Mountain, Smith’s Brigade completed its relief of Strahl’s command. Around 3:00 P.M. some Federal officers appeared across the river and proposed to trade newspapers. Some men from the Thirteenth Tennessee Infantry regiment made a brief visit, but Confederate officers prohibited reciprocity. Shortly thereafter, Harker’s skirmishers appeared at Wauhatchie and pushed toward the mouth of Lookout Creek. Two guns from Carnes’s Tennessee Battery, stationed a few hundred feet up the mountain, opened with solid shot and shell on the Federals clustered near the Elisha Parker House. According to a Confederate diarist, “A general stampede occurred among the enemy. They are now out of sight. All quiet at dark.” At corps headquarters, Polk’s aide William Richmond visited some young ladies to say goodbye and found them in tears. By nightfall, he too was ready to leave Chattanooga.21

Throughout the day, army headquarters continued to function at the Ely Bruce home. Bragg wrote to Samuel Cooper, explaining that Burnside was in Knoxville with 25,000 men, far too many for him to confront while simultaneously contending with Rosecrans’s army. “Rosecrans is yet beyond the mountains on this side of Tennessee, moving with great caution, and threatening our communications.” Unsure of how far he would have to retreat, Bragg instructed Brent to telegraph Henry Wayne of the Georgia State Guard to plank the railroad bridge at Resaca. Wayne was already on his way to Resaca to inspect its defenses. Brent also informed Col. Robert Garland, commanding at Kingston, that the army had no weapons to arm any militia activated by Governor Brown. As the hours passed, the staff’s focus shifted to the tons of ammunition and rations remaining at Chickamauga Station. Falconer, Brent’s assistant, telegraphed Capt. James Horbach, quartermaster at Chickamauga Station: “Are there any troops at Chickamauga? If so, put as many as necessary to work loading the cars with stores.” Later, Brent telegraphed, “Put every man to work to load stores on the cars.” Fearing that still more laborers would be needed, Brent telegraphed Buckner at Ooltewah to send a brigade to Chickamauga Station until everything was removed to safety. Brent also telegraphed Maj. J. W. Davis, commanding at Cleveland, to gather all government property there and take it to Dalton. At Chickamauga Station, Captain Horbach wired Medical Director Flewellen that seventy-four sick soldiers were at the depot awaiting transportation. The problem did not just exist at Chattanooga. During the day the hospital personnel at Cherokee Springs also headed south, first in two overloaded wagons to Ringgold, then in a filthy boxcar to Dalton. Traveling with nurse Kate Cumming and others were the wife and children of brigade commander Patton Anderson.22

As the sun dipped behind the massive bulk of Lookout Mountain, the western column of the Army of Tennessee began to move. Hill’s Corps led the way with Cleburne’s Division in front. As the shadows lengthened and the smell of cooked meat hung in the air, the troops left McFarland’s Spring and entered the Rossville Gap. The moon would not rise until after midnight, so only the stars guided the soldiers as they passed through the defile. Thereafter the road to LaFayette was relatively flat, and the march marred only by billowing clouds of dust raised by thousands of tramping feet. Although the men saw little in the darkness, they headed southward through heavy woods broken only by small fields cleared by subsistence farmers with names like McDonald, Kelly, Brotherton, and Viniard. Around midnight, after a march of eight miles, Cleburne’s van halted on Chickamauga Creek near a grist mill owned by the Lee and Gordon families. At the rear of the column, Sgt. William Heartsill wrote, “This may not be a retreat but it looks very much like one.” Heartsill consoled himself with the hope that Johnston, not Bragg, led the army. Not all of Cleburne’s Division was present. Two regiments of Polk’s Brigade inadvertently had been left behind on the river when the division concentrated in Chattanooga Valley. Rushing to join the column, the men of the Forty-Eighth Tennessee made it only as far as Tyner’s Station after a march of more than twenty miles. Finding the army gone, the Tennesseans spent the remainder of the night cooking rations in the abandoned camp. Breckinridge’s Division followed Cleburne. Except for the detail securing the division’s baggage at Chickamauga Station, Breckinridge’s men encountered few difficulties except for the choking dust. In the Third Florida Infantry regiment of Stovall’s command, the men sang as they marched, even though many were barefoot. It was well beyond midnight when the division halted in the dust short of Lee and Gordon’s Mill.23

According to the movement order, Polk’s Corps was to follow Hill out of the Chattanooga Valley on 7 September, but with Hill’s units not beginning to move until dark and clogging the narrow road through the Rossville Gap, Polk’s troops could not begin their own journey southward. Thus Hindman’s and Cheatham’s Divisions did not march that night. Hindman’s command remained in its camps near McFarland’s Spring, watching Hill’s troops pass for much of the night. Their rations were cooked, their tents were struck, and their wagons were loaded, but they received no orders to march. Hindman himself visited Deas’s Brigade, where he “made a beautiful little speech to the Brigade on the duties of the soldier, ‘On the march and in the battle.’” One of Deas’s units, the Thirty-Ninth Alabama Infantry regiment, remained in Chattanooga, serving as the police force of Col. Alexander McKinstry, the provost marshall. Cpl. John James, thirty-three, a member of the Thirty-Ninth, wrote to his wife from the nearly abandoned town: “My dear, I want you to write as often as you can. I hope that you will soon get well and I want you to pray for me. O that I could be with you and talk with each other. My dear, if we never meet any more on earth, I hope that we will meet in Heaven.” Like Hindman’s troops, most of Cheatham’s Division remained stationary as well. In Strahl’s Brigade, one soldier slept without his blanket, expecting any moment to be called into line, but neither he nor his companions were disturbed all evening. Stanford’s Mississippi Battery did move forward to McFarland’s Spring, but it remained there all night with horses harnessed as the road continued to be filled with Hill’s men. On the far side of Lookout Mountain, Smith’s Brigade checked Harker’s reconnaissance not long before dark. Apparently forgotten in the rush to close Polk’s headquarters, Smith’s command was unaware that the army was beginning its retreat. At 9:00 P.M. Polk finally remembered Smith, instructing signal officer Mercer Otey to send a message to Smith through the signal station atop Lookout Mountain, a task which occupied the entire night.24

If Bragg’s western column was slow off the mark on the evening of 7 September, his eastern column fared only slightly better. Leading that column was Walker’s Reserve Corps. At sunset Liddell’s Division took the road that led southeast toward Graysville, just south of the Georgia state line. Continuing past Graysville without a pause, Govan’s Brigade pushed on toward Ringgold, reaching it at dawn on the next day. Following Govan was Walthall’s Brigade, which stopped well short of Ringgold around midnight. Behind Liddell came Walker’s Division. From Tyner’s Station, Walker’s troops marched to Chickamauga Station and plodded through the billowing dust after Liddell. With Gist’s Brigade absent at Rome, only Ector’s and Wilson’s brigades made the trip. Even then, one of Wilson’s regiments was held at Chickamauga Station to load supplies on railroad cars. Buckner’s Corps was slated to follow Walker southward. By the evening, most of Buckner’s command had reached Ooltewah, six miles east of Tyner’s. There Buckner issued orders organizing divisional ambulance trains and forcing a draconian reduction in the amount of officers’ baggage: “Where transportation for ammunition & subsistence for the men is so limited, it scarcely becomes an officer to include trunks, bedsteads, tables (except for desks) chairs and other luxuries as part of his campaigning equipage.” During the evening Stewart’s and Preston’s Divisions left Ooltewah behind. Rather than take the direct road to Ringgold, they first marched westward to Tyner’s Station, then to Chickamauga Station, and finally southward toward Graysville, which they would not reach until the next day. Momentarily left at Ooltewah was Johnson’s Brigade, slated to assist in the evacuation of the army’s Chickamauga Station base. Also left behind was the Seventh Florida Infantry regiment, guarding several steamboats trapped on the Hiwassee River near Charleston. On receiving positive orders to burn the boats, the Floridians complied at midnight and headed southward toward Cleveland.25

Even as the Army of Tennessee was withdrawing from Chattanooga and the line of the Tennessee River, reinforcements were coming from other parts of the Confederacy. At Enterprise, Mississippi, Gregg’s Brigade boarded trains that would take it to Atlanta via a roundabout route through Mobile. McNair’s Brigade, which had departed Enterprise a day earlier, was already well on its way to Montgomery. Johnston had loaned the two brigades in response to Bragg’s statement that Atlanta was in grave danger. Every request from Johnston for more information on the nature of the threat, however, had gone unanswered by Bragg. On 7 September, Johnston tried again: “I have put the brigades in motion, but they are also necessary in Mississippi; so let me know why they are wanted that I may judge between Atlanta and Mississippi.” This message, too, would be ignored. Neither brigade brought its wagons, further complicating the already desperate shortage of wagons in the Army of Tennessee. In Virginia, Quartermaster General Lawton assured Lee that all preparations had been made for moving Longstreet’s Corps to Tennessee, and that the troops nearest Fredericksburg would be the first to go. Major Sims of the Railroad Bureau announced that the maximum flow rate would be 3,000 men per day and that he had ordered trains carrying that number to arrive at stations just south of Fredericksburg on the following day. Sims also telegraphed Maj. John Whitford at Goldsboro, North Carolina, that the troop movement would entail 18,000 men in five days, with the first units arriving at Weldon, North Carolina, on 9 September. While the railroad men hammered out the details of their trip, Longstreet’s troops began to gather outlying detachments and cook travel rations. Elements of Hood’s Division at dark headed for several railroad stations below Fredericksburg, while McLaws’s Division prepared to leave Waller’s Tavern near the North Anna River for Hanover Junction on the next day.26

Although Rosecrans’s headquarters apparently did not begin functioning early on 8 September, major elements of the Twenty-First Corps were active well before dawn. At 3:00 A.M., Palmer drafted a quick note to his wife in Illinois. Explaining that his division would soon move nearer Chattanooga, Palmer wrote, “I am not quite well but think I will be just as soon as I can sleep one night soundly. Hard marching gives every one inordinate appetites for food and that produces its usual consequences.” Around 4:00 A.M. Grose’s Third Brigade and Cruft’s First Brigade departed from their pleasant camps around Cole’s Spring and headed for the Trenton-Wauhatchie Road, a mile distant. Reaching that thoroughfare, they turned north. After a march of another three miles they halted on the floor of Lookout Valley at 7:00 A.M., approximately a mile and a half behind the defensive position occupied since the previous day by Wood. Given their location in the shadow of imposing Lookout Mountain, Palmer kept the two brigades under arms all day. Still, he was not intimidated by his situation, and planned to reconnoiter all the way to the top of Lookout Mountain near the seasonal settlement of Summertown. At 10:00 A.M. he announced his intentions to corps headquarters, but after sending the message reconsidered and decided to launch only small probes on the valley floor to the foot of the mountain. In the meantime, Van Cleve marched Beatty’s First Brigade and Barnes’s Third Brigade out of Murphy’s Hollow, down Sand Mountain, and halted them in Palmer’s old camps on the Cole plantation. Like Palmer, Van Cleve lacked a brigade, because Dick’s Second Brigade had not yet joined from McMinnville. Dick’s men, however, were closer than Van Cleve knew. Having marched from Bridgeport early that morning, they would reach Whiteside in late afternoon. Coincidentally, Van Cleve also wrote to his wife on 8 September: “I have been troubled with dysentery for a few days, and consequently cannot boast of feeling very well.”27

In front of both Palmer and Van Cleve, Wood rested his command all day while watching for signs of Confederate intentions. Meanwhile, he continued his war of words with Crittenden. During the morning, Crittenden’s pejorative endorsement on Wood’s long missive to Garfield came to hand. Dismissing Wood’s arguments, Crittenden denied that he had charged Wood with anything but unconscionably delaying the reconnaissance on the previous day and he repeated the charge. Crittenden’s strictures prompted Wood to write again to Garfield. This time Wood expended more than 1,500 words, reprising the charges that Crittenden had dropped and arguing that his actions were prudent: “With imperfect knowledge of the facts by which my action was necessarily controlled; with imperfect knowledge of the dangers which environed my command, and which I had to guard against, and without first affording me an opportunity to make an explanation in regard to the matter, General Crittenden sits in judgment on my conduct and makes a grave and hurtful charge against me to the commanding general of the army.” Wood need not have bothered, because Garfield, acting under Rosecrans’s instructions, at 2:00 P.M. dispatched a rebuke to Wood that validated Crittenden’s position. As the charges and rebuttals bounced back and forth from division to corps to army, Crittenden refused to end the controversy, although he changed his mode of attack. During the afternoon, Rosecrans had received a report that Wagner’s brigade was short of ammunition, causing Garfield to question Crittenden on the subject at 2:00 P.M. Seizing an opportunity to berate Wood and simultaneously raise his standing at army headquarters, Crittenden wrote to Wood at 5:40 P.M. peremptorily asking what Wood knew about the situation. Sensing the potential danger in such a seemingly innocuous question, Wood placidly replied that Wagner could hardly be low on ammunition because he had done little firing and in three messages that day had not raised such an issue.28

Even as they continued to bicker, the senior officers of the Twenty-First Corps worried about their precarious situation. Potentially Bragg’s entire army could debouch from behind Lookout Mountain and overwhelm Wood’s and Palmer’s divisions before anyone else could intervene. Palmer was initially the most anxious to discover what mischief lay concealed on the mountain’s precipitous slopes. Deciding that his initial plan to send troops to the top of the mountain was too aggressive without Crittenden’s prior approval, he contented himself with dispatching a regiment from each of his brigades to the base of Lookout. Cruft’s Second Kentucky Infantry regiment discovered a rough track leading upward on what was known locally as Powell’s Trace. Meanwhile, Grose detailed the Thirty-Sixth Indiana Infantry regiment to a similar task. While awaiting the results, Palmer visited Wood. For some time cannonading had been heard in the direction of Chattanooga, but its meaning was unclear. Upon returning to his command, Palmer found a note from Crittenden approving his plans for an aggressive reconnaissance but proposing a delay until the following day, when Van Cleve could participate. As night fell, Wood received indications that Chattanooga was being evacuated, and he rode to Palmer’s headquarters to propose a reconnaissance of his own, if Palmer could support him. With Crittenden’s instructions in hand, Palmer declined. Wood at 10:00 P.M. sent his own proposal for a reconnaissance to corps headquarters, now located near Van Cleve’s position. Crittenden had just returned from a visit to army headquarters at Trenton when Wood’s message arrived. Having learned that the entire army probably would be in motion on the next day, he rejected Wood’s proposal but agreed to submit it to Rosecrans for final decision. Clearly, Crittenden was turning to his other two division commanders for action, thereby denying Wood any of the glory that might be achieved on the next day.29

South of the fractious Twenty-First Corps, Thomas’s Fourteenth Corps was also active early on 8 September. At 4:00 A.M., Negley began to consolidate his position atop Lookout Mountain at Johnson’s Crook. First to move was Beatty, who was told to secure the track down the mountain at Cooper’s Gap with two regiments from his First Brigade. Beatty marched before dawn with the Fifteenth Kentucky and 104th Illinois Infantry regiments. Encountering cavalry pickets, Beatty’s men pressed forward, driving the handful of Confederates down the mountain. While the Fifteenth Kentucky continued to the base of the slope, the 104th Illinois halted halfway down and assumed a defensive posture. There it remained all day, with nothing to do but watch a large dust cloud rise in the valley east of Lookout far to the north. Four hours after Beatty moved, Stanley’s Second Brigade sent the Eleventh Michigan Infantry regiment to clear Stephens’s Gap of any obstructions. It also encountered cavalry videttes and easily pushed them to the base of the mountain. Clearing the road into the valley proved more difficult, because the Confederates had clogged the passage with fallen trees and rocks. Stanley’s weary men would not return to the top of Lookout Mountain until after midnight. Back in Lookout Valley, Sirwell’s Third Brigade helped the division’s supply train climb the west side of the mountain. Sirwell distributed his regiments along the grade to assist the struggling teams painfully pulling the heavily laden wagons up the steep incline. After a hard day’s effort, much of the train had reached the crest by nightfall, so Sirwell took three of his regiments up as well. The Seventy-Eighth Pennsylvania Infantry regiment remained at the western base of the mountain in Johnson’s Crook. In a 7:20 P.M. report to corps headquarters, Negley described the day’s efforts and, in passing, mentioned the ominous dust cloud rising in the valley an estimated nine miles to the north toward Chattanooga. He surmised that the rising dust signified the possibility that reinforcements were arriving to join Bragg’s army.30

Negley’s route via Johnson’s Crook and Stephens’s Gap was the designated pathway for the entire Fourteenth Corps, but until he completed the journey no other divisions could follow. Rosecrans’s campaign plan did not anticipate that Thomas would be the first to push east of Lookout Mountain, a task assigned to Stanley and McCook. If the Army of Tennessee was to be pried out of Chattanooga without a fight, Rosecrans needed to put pressure on Bragg’s supply line far enough south of the city to ensure that the Confederate retreat would not halt until well toward Atlanta. Thus Negley’s cautious probing beyond the mountain was fully in accord with the original plan. His difficulty in getting his trains up Lookout, however, meant that the remaining Fourteenth Corps divisions would not move at all on 8 September. Baird’s First Division spent the entire day idling in camp at the mouth of Johnson’s Crook. Baird chafed at the delay, knowing that it would permit the men of his two brigades to commit depredations during their liberal foraging in the neighborhood. John King’s Third Brigade meanwhile began to concentrate around Stevenson in preparation for joining the division. At Trenton, Reynolds’s Fourth Division also remained stationary. Turchin’s Third Brigade garrisoned Trenton itself, while Edward King’s Second Brigade guarded both Payne’s (Sitton’s) Mill and the Empire State Iron Works. Like Baird’s men, Reynolds’s troops had little to do, giving them opportunity for mischief. After dark some of King’s soldiers set fire to a large number of worker’s huts and stacks of wood ready for the iron furnaces, creating a conflagration difficult to extinguish. North of Trenton, the soldiers of Brannan’s Third Division remained in their pleasant camps at the Cole plantation, where they welcomed the arrival of Van Cleve’s division. Corps headquarters remained at Brown’s Spring, but Thomas planned to move to Easley’s plantation on the next day. That evening Thomas ordered Negley to advance his entire division to the eastern foot of Lookout Mountain in the morning.31

Crittenden and Thomas moved slowly because Rosecrans expected greater effort from Stanley and McCook. In the camps of the Cavalry Corps, however, the only movement on the morning of 8 September was thousands of disgruntled men unsaddling their horses and unpacking their gear. Although he had promised to cross Lookout Mountain that morning, Stanley decided not to do so. His specific reasons remain unclear, but some things are known. First, Stanley was a cautious commander who in the past had been philosophically opposed to deep strikes. Abel Streight’s disastrous raid in the spring no doubt remained much on his mind. Second, although he had soundly defeated Wheeler at Shelbyville in June, Stanley truly may have believed that without Minty’s brigade he would be seriously overmatched in a fight. Third, innate character flaws may have been at play. According to a modern author, Stanley “suffered bouts of depression and uncontrollable drinking, the latter after periods of intense pressure.” Certainly the pressure on Stanley was great, with Rosecrans and Garfield demanding that he leap into the unknown world beyond Lookout Mountain. In October, Assistant Secretary of War Charles Dana would claim that “a few months ago General Stanley defeated an important operation by being drunk at the critical moment.” Finally, Stanley may simply have been a victim of poor health, so poor that he would relinquish command a week later. The diagnosis, severe dysentery, required evacuation from the front and an extended convalescence. In his memoirs Stanley gave no explanation for his unusual behavior on 8 September, although in a later letter to Rosecrans he promised to explain himself fully when the two met. He simply wrote to Garfield at 7:00 P.M. that he had not moved as promised because of a lack of horseshoes. Given the time he had been at Valley Head, this excuse was risible. Clearly, more was at play than horseshoes, but whether it was stress, alcoholism, dysentery, or a combination of these factors is impossible to discern.32

Stanley’s decision meant that McCook’s Twentieth Corps would not be crossing Lookout Mountain on 8 September. Davis’s First Division, slated to support Stanley, remained mostly inactive around the Winston plantation. While Post’s First Brigade spent the day improving the tortuous road up Lookout, Lt. Chesley Mosman of the Fifty-Ninth Illinois Infantry regiment strolled to the top to survey the scene. There he found the men of Carlin’s Second Brigade amusing themselves by rolling large rocks down the steep slopes. In the evening Post held a brigade dress parade attended by Davis and his wife. Several miles to the north, the three brigades of Johnson’s Second Division moved to new camps at Long’s Spring, a march of approximately three miles. There they had an excellent source of freshwater, and were on the direct road between Trenton and Valley Head. So good was the location that McCook relocated corps headquarters to Long’s Spring as well. With Sheridan’s Third Division seven miles north of Long’s Spring at Stevens’s Mill, McCook’s headquarters was now centrally located for the first time since crossing the river. Sheridan’s soldiers themselves remained in camp all day. Some men improved the time by washing their dusty uniforms in Lookout Creek, while others spent the day reading or writing letters. Still others, bent on improving their army rations, foraged in the neighborhood, which had not yet been stripped of edibles. Some inhabitants tried to secure their provisions by burying them, but to no avail. Sheridan’s men were in a relaxed mood, lying in a pleasant valley surrounded by forest-clad mountains untouched by war. That night Lytle was serenaded by the band of the Twenty-Fourth Wisconsin Infantry regiment, and Bradley wrote his wife, “I think the rebels will collect their forces at or near Atlanta, and try to defend that point, and very likely a severe battle will come off there, but I do not believe it will be fought very soon.” Pvt. Henry Williams was even more optimistic, writing to his mother that “faith in General Rosecrans is unbounded.”33

Stanley’s four brigades took advantage of the extra day of preparation. Several detachments arrived with new horses to replace those too debilitated to make the climb. Even so, a number of men remained dismounted. They were sent back to Stevenson and eventually to the remount depot at Nashville, missing the campaign entirely. Having expended their first day’s travel rations in camp, Stanley’s men received an additional issue to reconstitute their three days of supply. Still others took the opportunity to winnow their baggage to the absolute minimum needed for the trip. During the morning, each division sent a battalion up the mountain to scout the route and drive away any prying Confederate eyes. In Edward McCook’s First Division a battalion of the Second Michigan Cavalry regiment climbed the mountain and scouted southward, finding nothing. Crook’s Second Division had better luck, with a battalion of the Fourth Ohio Cavalry regiment seizing a lone Confederate. With Minty’s First Brigade still absent, Crook had only the services of Long’s Second Brigade and a portion of the Chicago Board of Trade Battery at his disposal. Nevertheless, Stanley decided that Crook and Long would lead the expedition, and he ordered Crook to send Long’s ambulances and a section of guns to the crest before dark. Notified at 3:00 P.M., the guns moved an hour later and, accompanied by Long’s ambulances, slowly ascended the mountain. Although Stanley had specified that only a battalion of cavalry accompany the wheeled vehicles, Crook decided to have Long’s entire brigade follow them up the mountain. At 5:00 P.M. Long’s troopers began the climb, which continued until they camped on the plateau five hours later. Both Stanley and Crook accompanied Long. Meanwhile, Edward McCook ordered his First Division to begin its own journey up the mountain at 4:00 A.M. the next day. Most of Stanley’s trains would remain parked in Winston’s dusty fields. The hour was late, far too late in William Rosecrans’s estimation, but at last the Cavalry Corps was lurching into motion.34

If Stanley was reluctant to move, Rosecrans’s deception force was not. Looking down on Chattanooga, Wagner became increasingly convinced that the Confederates were leaving the town. At 8:00 A.M. he informed Hazen that he would soon open with artillery in support of Wood. Two hours later he reported to army headquarters that only cavalry garrisoned the town. At noon he forwarded the report of a deserter that Bragg’s army had gone “toward Rome.” When shots fired toward the lower slopes of Lookout Mountain elicited no response, Wagner informed Rosecrans that only Cheatham’s Division was present and the Confederate pontoon bridge had been broken up. During the afternoon, he used Wilder’s battery and his own to shell the town from progressively shorter distances. By the end of the day the guns were firing at the Confederate fortifications from little more than 500 yards away, receiving only scattered shots from a handful of sharpshooters. While Wagner satisfied himself that Chattanooga was virtually empty, Wilder concentrated two regiments and parts of two batteries opposite Friar’s Island. Planted in corn, the fifty-acre island shielded Federal movements somewhat, and when Federal artillery fire elicited no significant response, Wilder decided to ford the shallow channel separating the island from the west bank. During the afternoon the Seventeenth Indiana waded to the island, losing only one man, Joseph Wilson, drowned. The Confederate response now strengthened and for the first time included artillery fire. Wilder therefore postponed further action until the next day, although he still favored Friar’s Island as a crossing point. The only sour note was provided by Minty, who reported that a crossing by Pegram’s Division was imminent. In light of that, he preferred to wait for the arrival of his last battalion from McMinnville before moving in any direction. Thus Minty remained inert at Sale Creek, anxiously awaiting an imaginary Confederate onslaught.35

The army’s lack of movement on 8 September permitted the units of the Reserve Corps to close the gap that separated them from the front. Granger himself remained ill in Nashville, so he instructed Morgan to expedite the movement. Morgan was to send Daniel McCook’s brigade and Steedman’s command to Bridgeport, while holding Stevenson with Tillson’s brigade. Granger promised Morgan that he would arrive at Stevenson on the next day. As Tillson’s soldiers assumed responsibility for guarding the massive Stevenson supply dump and nearby railroad bridges, the other brigades made slow but steady progress toward the river. Three of Daniel McCook’s regiments entered Stevenson during the day, and the Eighty-Sixth Illinois Infantry reached Huntsville. Steedman’s two brigades encountered more difficulty than McCook as they crossed the Cumberland Plateau from Cowan to the Crow Creek valley. Whitaker’s First Brigade left Cowan early and marched over the mountain to Anderson Station. While the exhausted infantrymen bathed in Crow Creek, the brigade’s teamsters struggled with many broken wagons and remained far behind. Left at Cowan were two doctors and 200 convalescent soldiers who had hoped to take the train to Stevenson but whose paperwork was not in order. Following Whitaker was the Second Brigade, now led by newly arrived Col. John Mitchell, who by seniority replaced Col. William Reid. Mitchell’s men also encountered difficulty on the mountain road. Numerous wagons broke down and the 113th Ohio Infantry regiment was forced to abandon its portable bakery. Mitchell’s artillerymen broke two caissons and, perhaps in frustration, amused themselves by mindlessly throwing rocks down the railroad tunnel’s air shafts. Nevertheless, Mitchell’s brigade also entered the upper reaches of Crow Creek valley by the end of the day. Some miles to the north, the Eighty-Ninth Ohio Infantry regiment prepared to leave Tracy City for Bridgeport. Ominously, the few citizens remaining at the Tracy City coal mines elected to leave with them.36

With most of his army motionless, Rosecrans was well aware that the momentum he had gained was in danger of dissipating if he did not initiate further action. The Tennessee River and Sand Mountain had been overcome; now only the great wall of Lookout Mountain prevented him from completing the movement that would pry the Army of Tennessee out of its Chattanooga stronghold. For his plan to succeed, Rosecrans needed two things: first, Stanley and McCook must mount a credible threat to Bragg’s supply line, and, second, accurate information about Bragg’s response to that threat must be obtained. Given those two conditions, Rosecrans could retain the initiative. He had Stanley’s promise that he would begin his advance that morning, late but perhaps not too late. As for information on Confederate movements, Lookout Mountain prevented Rosecrans from seeing what Bragg’s army was doing, and the long-range observations of the deception force were a poor substitute for direct knowledge. Wood’s two visits to the Wauhatchie area had provided little information, and Rosecrans’s frustration was evident in the rebuke he had Garfield send Wood. Virtually all of Rosecrans’s mounted units were absent on the army’s flanks, but he deployed what little remained to penetrate the Lookout Mountain wall near Trenton. He dispatched Col. William Palmer’s Fifteenth Pennsylvania Cavalry regiment to find routes up the mountain, no matter how tortuous. In addition, Col. Smith Atkins’s Ninety-Second Illinois Mounted Infantry regiment had just reported for duty at Trenton. Originally slated to join Crittenden’s command, it was now assigned by Reynolds also to seek routes up Lookout’s forbidding flanks. The searches generated two alternative routes up the mountain, the Nickajack Trace approximately two miles north of Trenton and a similar path slightly farther south known as the McKaig Trace. Neither of these two discoveries, however, yielded any information on Confederate activities or intentions.37

As the day ended, critical information arrived at Rosecrans’s Trenton headquarters. First, McCook forwarded a report from a deserter from Company D, Fourth [Eighth] Tennessee Cavalry regiment. Pvt. Richard Owen correctly placed Wharton’s Division around Alpine and Summerville, and Martin’s Division around LaFayette. Owen also correctly identified eight of the nine regiments in Wharton’s Division. If he credited Owen’s story, Rosecrans thus knew the size and dispositions of the Confederate units facing Stanley. Next, a scout known as “D. M. W.” reported in great detail on what he had learned during a month’s stay in Chattanooga Valley. Quoting a Union sympathizer whose railroad travel had been disrupted by troop movements, “D. M. W.” stated that Breckinridge’s Division had joined Bragg with from 12,000 to 20,000 soldiers. The scout explained that Johnston was not with the new arrivals, he having been confused with Brig. Gen. Bushrod Johnson. “D. M. W.” also reported that Buckner’s troops had been at Loudon and were expected to continue moving southward. Most important of all, he stated that the Confederate pickets on Lookout Mountain had been withdrawn that morning and that most of Bragg’s army was concentrated at the foot of Missionary Ridge. According to a talkative cavalryman, the scout said, Bragg had been flanked out of Chattanooga and was withdrawing to a better position in order to defeat the Federals in detail. This statement correctly reflected Bragg’s intentions, but it seems to have been overlooked in the general euphoria that swept through the headquarters. On the strength of the scout’s report, corroborated by Wagner’s observations, Rosecrans approved Crittenden’s reconnaissance to the top of Lookout Mountain on the next day. He ordered Thomas to support Crittenden with the Ninety-Second Illinois and also with Brannan’s division if necessary. Anticipating that Crittenden’s move would show the Confederates gone from Chattanooga, Rosecrans at 10:00 P.M. ordered Wagner to cross the Tennessee and join what was expected to be a pursuit.38

Suddenly the festive mood at army headquarters was broken. A courier arriving from Crook mentioned in passing that the Cavalry Corps had not begun its advance that day. Rosecrans instantly flew into a rage and dictated a scathing response to Stanley: “I learn from him that your command lies at the foot of the mountain on this side, intending to move in the morning. I am sorry to say you will be too late.” In biting language, Rosecrans castigated Stanley for not following his instructions: “So far your command has been a mere picket guard for our advance. Orders accompany this, which I hope to see effectually executed.” At 11:00 P.M., Garfield revoked Stanley’s orders to strike for Bragg’s railroad, replacing them with a much more modest task. Stanley now was to send one brigade from Alpine northward toward the southern end of Missionary Ridge while at the same time advancing another brigade eastward toward Summerville. “The enemy is believed to be in full retreat, and it is most important to know where he is going and by what routes. You have not a moment to lose in starting these expeditions.” Garfield promised Stanley that McCook would support each of the cavalry’s thrusts with an infantry brigade. To ensure that McCook understood his role, Garfield addressed a detailed message to him: “From all the evidence before us it appears that the enemy is evacuating Chattanooga and moving south; a part of his force has already reached the northern spur of Missionary Ridge. We must know as speedily as possible what route he is taking.” McCook’s brigades were not to go beyond the eastern foot of Lookout Mountain. In both messages, Garfield’s grasp of the complex geography between Alpine and Chattanooga was weak, especially in regard to the brigade slated to advance northward toward Missionary Ridge. Nevertheless, the new orders were dispatched to Valley Head. Shortly thereafter, Rosecrans drafted his nightly report to Washington: “Information to-night leads to the belief that the enemy have decided not to fight us at Chattanooga.”39