17

THE FALL OF CHATTANOOGA

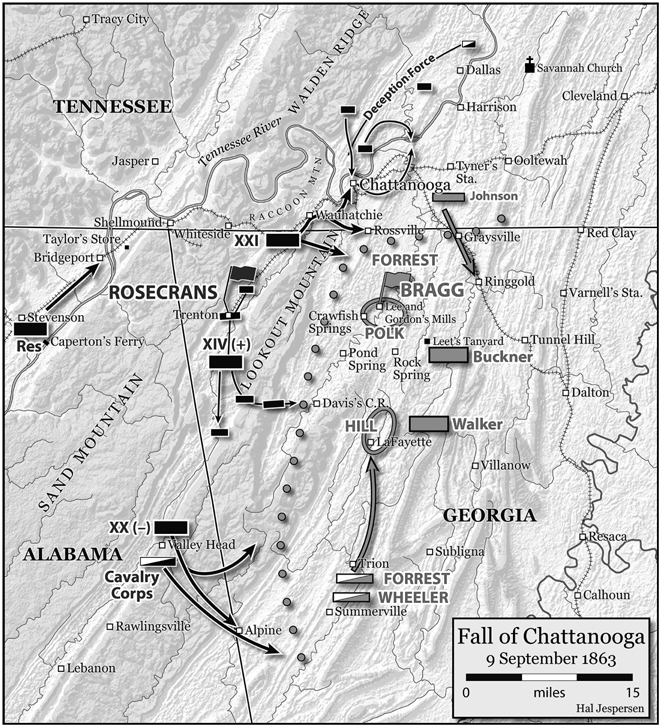

» 9 SEPTEMBER 1863 «

As watches ticked past midnight, announcing the beginning of Wednesday, 9 September, lights burned brightly in army headquarters at Trenton. Rosecrans’s normal routine kept staff officers active beyond midnight every night, though business often ended with the daily message to Washington. Thereafter, it was time for conviviality lasting several hours. As a result, little business was transacted early in the morning because everyone slept late. Easy to follow in garrison, this pattern wore less well when active campaigning required the headquarters to function both early in the morning and late at night. Gradually the sleep deficit grew, and without noticing it, men became ever more physically weary and mentally dull. On this night, however, there was something new to keep the officers’ adrenalin flowing. All new information seemed to indicate that the Army of Tennessee was leaving Chattanooga or had already gone. During the previous afternoon Crittenden had accepted Palmer’s proposal to send troops up Lookout Mountain at first light and had ordered Van Cleve to do the same. At the same time, he had rebuffed Wood’s proposal to make a reconnaissance of his own. At 1:00 A.M., not long after dispatching his daily report to Washington, Rosecrans gave final approval to Crittenden’s probe, which now included the Ninety-Second Illinois Mounted Infantry regiment from Thomas’s Fourteenth Corps as a support. At 2:30 A.M., Frank Bond confirmed disapproval of Wood’s proposal. At the same time, Bond exuberantly forecast the imminent fall of Chattanooga. Five minutes later, he instructed Capt. Jesse Merrill, the army’s chief signal officer, to be present when the probes began, in order to transmit any information they might generate. In response to these instructions, eight miles north of Trenton, William Grose began to move toward the mountain with three regiments. His goal was a steep and narrow pathway up the shoulder of the mountain called Powell’s Trace. Three miles north of Trenton, Samuel Beatty led his brigade across Lookout Valley to the foot of the mountain preparatory to ascending the faint Nickajack Trace.1

At the very time that Grose and Beatty were stumbling through the darkness on the floor of Lookout Valley, a message reached Trenton from George Wagner: “The enemy has evacuated Chattanooga. They left to-day. Will occupy the place to-morrow.” The message, which arrived around 3:00 A.M., had been more than six hours in transit, first by signal torch from Walden’s Ridge to Shell Mound, then by telegraph to Whiteside and up Murphy’s Hollow, where a courier carried it to army headquarters. Instantly, all thoughts of levity or sleep vanished, and Rosecrans quickly dictated a series of orders to Crittenden, Wagner, and Thomas. At 3:30 A.M. Garfield ordered Crittenden to “throw your whole command forward (with five days’ rations) without delay, and make a vigorous pursuit.” In a final sentence, which spoke volumes about Rosecrans’s view of Crittenden’s competence, Garfield counseled Crittenden to take only wagons enough for a five-day pursuit but to carry an ample supply of ammunition. At the same time that Garfield wrote to Crittenden, Goddard directed Wagner to push across the Tennessee River as rapidly as possible and join Crittenden’s column in pursuit. Like Crittenden, Wagner was to take with him only enough wagons to keep the troops supplied for five days with both food and ammunition. Finally, Garfield wrote to Thomas, also at 3:30 A.M. In a very brief note, he shared the contents of Wagner’s dispatch, canceled the movement of the Ninety-Second Illinois Mounted Infantry to support Crittenden’s probes, and ordered Thomas to prepare the Fourteenth Corps for instant movement. Most important, he informed Thomas that “the general commanding desires you to call on him at once to consult in regard to arrangements for the pursuit.” These 3:30 A.M. messages indicate that Rosecrans, with the possible advice of Garfield, had already decided upon the army’s new course of action before consulting Thomas. Pursuit it would be. Thus the die was cast: Chattanooga, so long the objective, now would be replaced by a chase after the elusive Army of Tennessee.2

Thomas’s original plan for the day was to move corps headquarters from Brown’s Spring to Easley’s Plantation, seven miles south of Trenton, so as to follow his divisions in their trek across Lookout Mountain. Now he rode to army headquarters, probably arriving not long after sunrise, which occurred shortly after 6:00 A.M. Neither Rosecrans, Thomas, nor any other participant recorded the ensuing discussion, and the only account of the meeting comes from Thomas’s chaplain, Thomas Van Horne, who was himself not present. After the war and at Thomas’s request, Van Horne wrote a history of the Army of the Cumberland, published in 1875 after Thomas’s death. Subsequently, he published a biography of Thomas in 1882. In it he asserted for the first time that during the meeting with Rosecrans, Thomas vigorously opposed an immediate pursuit of Bragg’s army. At the time, Rosecrans’s major elements were widely scattered along the length of Lookout/Wills Valley. The army’s supply lines were tenuous, dependent upon single-track railroads, rickety pontoon bridges, and long wagon-hauls over two mountains. Instead of a hasty pursuit on widely divergent routes, the army’s scattered corps, Thomas believed, would be better served by marching directly to Chattanooga using Lookout Mountain as a shield. There the army could consolidate its position and amass sufficient supplies to sustain any subsequent advance. If this was indeed Thomas’s view, it was certainly in keeping with his cautious and methodical nature. Rosecrans rejected all of Thomas’s proposals and entreaties. In a private letter in 1884, Van Horne wrote that Thomas “told me that on the morning of the 9th of September he had presented one military reason after another against the pursuit of Bragg’s army and for the occupation of Chattanooga and the establishment of reliable communications. He said Rosecrans assented in every instance and Thomas then said ‘Why don’t you do this then?’ The reply was ‘they expect more of me.’” Clearly, Halleck’s threats and Lincoln’s gentle chiding had had their effect on Rosecrans’s thinking.3

If Thomas was cautious, Wagner was aggressive. Chaffing under the cautious Hazen, he had questioned Hazen’s seniority and had gained command of the deception force. As soon as he gained control, he had ordered increased activity opposite Chattanooga and upstream at Friar’s Island. On the previous afternoon a call for volunteers to swim the river and secure boats for a crossing brought forth several soldiers willing to attempt the passage, but darkness prevented their effort. Now, as the sun burned away the mist on the river, the same men readied themselves to try again. Confederate pickets from Rucker’s Legion withdrew from the river around 8:00 A.M., giving the men of the Ninety-Seventh Ohio Infantry regiment their opportunity. More than twenty years later, Capt. William Naylor of the Tenth Indiana Battery claimed that he crossed alone with the help of a civilian in a canoe and was fired upon by the withdrawing Confederates, but no one else mentions his exploit. Somewhat more substantial is the claim that three men from Company C, Ninety-Seventh Ohio—Sgt. Andrew Hossum, twenty-three, Cpl. William Jackson, nineteen, and Pvt. Jacob Kraps, twenty-three—were the first Federal soldiers to cross the river. They used a small boat paddled by a black man. Having made the crossing, the three, with the possible assistance of friendly civilians, untied a mule-powered ferry and propelled it back to the Federal shore. By now it was well after daylight, and hundreds of Federals witnessed the bold crossing. Seizing the moment, Lt. Col. Milton Barnes of the Ninety-Seventh Ohio quickly loaded Companies C and I and the regimental colors on the ferry and sent it back across the stream. There Barnes deployed the companies as skirmishers and sent some of the men to the fortifications at Cameron Hill, where they raised the colors. Visible to Wagner’s brigade and part of Wilder’s command, the flag elicited universal cheers. The time could hardly have been later than 10:00 A.M. and probably was somewhat earlier.4

At 5:45 A.M., about the time Sergeant Hossum’s party was negotiating for a boat to take them across the river, Crittenden received Rosecrans’s 3:30 A.M. order to advance on Chattanooga and quickly passed it to his division commanders. Nearest Chattanooga was Wood’s First Division. Buell’s First Brigade was already preparing for a possible reconnaissance, so it became the first unit to take the road. Harker’s Third Brigade followed at 8:00 A.M., much to his annoyance. A mile south of Harker’s position, Palmer’s Second Division also received Crittenden’s order to advance in haste. The order came too late to recall Grose and his three regiments clawing their way up Powell’s Trace, so Grose’s two remaining regiments were attached to Cruft’s First Brigade. Cruft and his expanded command took the road at 8:00 A.M., moving with the division’s artillery and baggage train. They quickly found themselves slowed by Wood’s wagons. Several miles south of Palmer, Van Cleve also received the order to march on Chattanooga. Beatty’s First Brigade was also beyond recall and was well on its way up Lookout Mountain on the Nickajack Trace. Thus Van Cleve marched from Cole’s Spring with only Barnes’s Third Brigade and the division’s artillery and trains. Dick’s Second Brigade had finally reached Whiteside on the previous afternoon and continued toward Lookout Valley, eventually joining Van Cleve’s column during the day. Also in motion was Smith Atkins’s Ninety-Second Illinois Mounted Infantry regiment. When their orders to sweep the top of Lookout Mountain were canceled, Atkins reported to army headquarters and was told to lead the Twenty-First Corps into Chattanooga. Pleased to operate independently without interference from Wilder or Reynolds, Atkins headed northward to overtake Crittenden’s column. Driving his men forward relentlessly, Atkins passed Palmer and Van Cleve before they got on the road and soon reached Wood’s leading brigade.5

Upon finding Wood’s troops filling the road as they approached the steep grade up the slope of Lookout Mountain, Atkins confronted Wood and demanded the right of way. Sensing that Chattanooga was about to fall to his command, Wood at first demurred but ultimately made way for the horsemen. When Atkins’s advance met Confederate skirmishers, he dismounted Company F and sent it up the mountain. The Confederates, part of the Third Alabama Cavalry regiment, stubbornly resisted and overlapped the Federal line. Wood soon appeared with the Twenty-Sixth Ohio Infantry regiment of Buell’s brigade, and Atkins reluctantly asked for assistance. In response, the infantrymen deployed on the hillside to the right of the Ninety-Second Illinois and forced the Confederates to retreat. Just as Atkins was about to resume his advance, shells began to land uncomfortably near his command. The artillery fire came from a section of Lilly’s Eighteenth Indiana Battery. Positioned on Stringer’s Ridge, Lilly’s gunners could not distinguish friend from foe and fired indiscriminately into the trees along the road. Irked by the unhelpful shelling, Atkins briefly considered having a man swim the river, but changed his mind when a soldier claimed he could stop the gunners with a makeshift signal flag. Using a handkerchief and a stick, the soldier soon attracted the attention of Lilly’s gun crews and the firing ceased. Just as Atkins prepared to resume his advance, Wood called him to a conference. Ordering two companies to chase Mauldin’s Alabamians toward Rossville while the remainder of the regiment prepared to dash into Chattanooga, Atkins sourly rode back to Wood’s position. If Wood was attempting to delay the Ninety-Second Illinois until more of his infantrymen could catch up, he failed because Atkins refused to hold his men back. Breaking free from Wood, he sent his command down the mountain with the regimental colors leading the way. By the time Wood rode to the front with Harker and Harker’s flag, Atkins and the Ninety-Second Illinois were already in Chattanooga Valley racing for the city.6

Thundering over the Chattanooga Creek bridge, Atkins and seven companies of his regiment entered Chattanooga on Chestnut Street. Just beyond the railroad depot they halted at the Crutchfield House, a large brick three-story building formerly owned by the Unionist Crutchfield brothers. On top, Atkins’s men unfurled the regimental colors and proclaimed the capture of the city. According to Atkins, the time was 10:00 A.M. An hour later, in a dispatch to both army headquarters and division commander Reynolds, he announced the capture of Chattanooga and reported the Confederate army heading south. Detailing a company to secure the city, Atkins prepared to head upriver in search of scattered Confederate defenders. His independence ended around noon with the arrival of Crittenden, who sent him to Friar’s Island to facilitate Wilder’s crossing. Atkins was satisfied that his were the first troops to enter Chattanooga, but it is probable that the handful of men from the Ninety-Seventh Ohio of Wagner’s brigade had beaten him to the prize by a few minutes. Eventually men from the two regiments met in the nearly deserted downtown and the capture of Chattanooga was complete. While the Ninety-Second Illinois paused, Wagner kept the mule-powered ferry in full operation, transferring his four regiments to the foot of Market Street. The ferry was small, holding only part of a regiment or two full wagon teams at a time, so the process continued throughout the afternoon and into the night. Meanwhile, Wood’s other brigades entered the city. Buell’s First Brigade arrived at noon, followed by Harker’s Third Brigade an hour later. Col. Emerson Opdycke of the 125th Ohio Infantry regiment led Harker’s troops because Harker had raced ahead with Wood. By 2:00 P.M. Wood had complete control of Chattanooga. The race to be first to enter the city appeared unseemly to Chaplain John Hight of the Fifty-Eighth Indiana Infantry regiment: “There is a great rush now to get to the front. There was not so much of a desire to rush that way awhile ago. Now that the dog is dead, everybody wants to get in at the burial.”7

The city that Federal troops had fantasized about for so long was a disappointment to many. There had always been something of a raw, frontier style to the town, which had not yet removed the rocks from its streets when the war came. Now, after weeks of bombardment, Chattanooga had a dilapidated and badly worn appearance. There were holes in numerous buildings, with most damage near the river and around the railroad depot. Even more obvious was the silence. Most inhabitants had left the city shortly after the shelling had commenced, leaving their property abandoned. The unfortunate few who either could not leave or chose to remain now found their city under new ownership. Not all were displeased at the result, and some readily offered information about the city’s former masters and the routes taken by the departing Army of Tennessee. Most notable was a merchant named Jesse Thompson, forty-six, who told the Federals that Bragg’s army had retreated on the previous day in two columns, one via the LaFayette Road and the other via Ringgold. In both cases, the army’s destination was Rome, Georgia: “If we pursue vigorously they will not stop short of Atlanta.” Most intriguing was Thompson’s assessment of Bragg’s army: “Troops badly demoralized; all feel that they are whipped; one-seventh of the troops mostly naked; the rations for three days would make one good meal.” Thompson established his credentials by claiming that he had a son in Rosecrans’s secret service. Indeed he did, as Michael Thompson, twenty-five, also a Chattanooga merchant, had been reporting to William Truesdail’s organization since at least July. The sympathies of the Crutchfield brothers were well known, but the Thompsons apparently operated clandestinely. Unlike the Crutchfields, the Thompsons, and a few others, Chattanooga’s remaining citizens waited quietly to see what would happen next. Rev. Thomas McCallie feared the worst, but he was happily surprised: “Here was a peaceable occupation of a city without any violence or outrage of any kind.”8

Having occupied Chattanooga, Crittenden turned his attention to the remainder of the Twenty-First Corps. Originally following in Wood’s wake, Palmer’s and Van Cleve’s divisions were redirected by Crittenden in early afternoon toward Rossville. Three of Palmer’s regiments and four of Van Cleve’s were still engaged in sweeping the crest of Lookout Mountain to disperse any lingering Confederates. Crittenden was aware that Grose had gained Summertown by noon, but he had not yet learned of Beatty’s progress farther south. He had now reached the limit of the instructions received eight hours earlier and did not know how to proceed without further guidance. At 2:00 P.M. he wrote to Garfield, plaintively seeking that guidance: “Shall I order the train of my corps to follow my command? I have received no further orders from you, as you stated I would in your dispatch reporting the evacuation.” Crittenden added, “There are various rumors of Bragg having stated that he just wanted to get us in here, that he is not far off, &c., but I am not a bit scared.” If Crittenden did not fear the Confederates, he also had no idea of what to do next. With Hazen still west of the river, Grose and Beatty on Lookout Mountain, and Wagner dependent on a tiny ferry, Crittenden’s command was scattered. Just as he was about to send his message to Trenton, he received a dispatch from Rosecrans. Six hours in transit, the dispatch nevertheless furnished the guidance that Crittenden sought. Rosecrans wanted Crittenden to leave one brigade to garrison Chattanooga and lead the balance of the corps in a pursuit conducted with the “utmost vigor.” He anticipated that the pursuit would lead Crittenden toward Ringgold and Dalton, while at the same time Thomas was moving on LaFayette and McCook was marching on Alpine. Crittenden was to retain Wilder’s brigade until he was near the Fourteenth Corps, when it would revert to Thomas’s control. If Crittenden encountered a Confederate force too large for him to handle, he was to assume a defensive posture and notify army headquarters promptly.9

Market Street in Chattanooga, Tennessee, with Stringer’s Ridge in background. (Chattanooga Public Library)

Far above Crittenden, two of his brigades were sweeping the heights of Lookout Mountain for random Confederates. At first light Grose had led three of his regiments up the horse trail known as Powell’s Trace. Near the top, pickets from Mauldin’s Third Alabama Cavalry regiment briefly barred the way, but Grose’s men quickly dispersed the Confederates, gained the crest, and turned north toward Summertown, three miles away. Also scaling the mountain was topographical engineer William Margedant, accompanied only by a corporal. Margedant’s goal was the tip of Lookout Mountain, with its magnificent view and a flagpole hosting a Confederate flag. Arriving at the point of the mountain, Margedant suddenly found himself in the presence of Confederate cavalrymen. Equally surprised, the two groups acknowledged each other and peacefully went their separate ways. Finding the flag gone, Margedant unsuccessfully attempted to remove its rock foundation as a souvenir. The Confederates meanwhile left the crest via a good road that descended the mountain’s eastern side. Soon Grose’s men arrived from Summertown. They spent some time marveling at the stupendous view and ransacking nearby houses. Some found a large cache of sweet potatoes, while others discovered a barrel of whiskey in an abandoned building. Gathering their booty, Grose’s command then began descending into Chattanooga Valley, where their parent division could be seen toiling toward Rossville. Several hours behind Grose was Beatty. At the top of the narrow Nickajack Trace, Beatty’s men found themselves eight miles from Summertown and nine from the tip of the mountain. After resting several hours they marched northward, meeting no resistance except an angry young woman at Summertown who denounced them roundly. Reaching Lookout House, they found everything valuable already in the pockets of Grose’s troops and could only gape at the view for a few moments in late afternoon before they also descended the mountain.10

Except for Wagner, the Federal deception force found itself unable to exploit the Confederate departure. Although he had built some boats and believed the Confederates facing him were weak, Hazen also could not disregard Minty’s reports about a Confederate crossing in force. At 6:00 A.M. he wrote to Rosecrans expressing Minty’s concern and promising to survey the area in person. An hour later he told Wilder that he would be visiting Minty and that Wilder should use extreme caution until the situation was clarified. The normally aggressive Wilder took Hazen’s cautionary note to heart. He had pushed the Seventeenth Indiana Mounted Infantry regiment across a shallow channel to Friar’s Island during the previous night but now doubted the wisdom of that action. With the far shore still guarded by artillery, Wilder withdrew the Seventeenth Indiana and opened a bombardment with a section of his Eighteenth Indiana Battery. By the time the men of the Seventeenth Indiana returned to camp, news of the fall of Chattanooga reached them. Also, the Confederate pickets at Friar’s Island had disappeared. In response, Wilder in late afternoon managed to get portions of the Seventy-Second Indiana and Ninety-Eighth Illinois Mounted Infantry regiments across the river at Friar’s Island, where they found the Ninety-Second Illinois awaiting them. With his baggage still atop Walden’s Ridge, Wilder at 10:00 P.M. informed the Twenty-First Corps that he would not finish crossing the river until the following afternoon. Delayed by his jaunt to Sale Creek to see Minty, Hazen was even less ready to push his brigade over the Tennessee. With one regiment on Walden’s Ridge guarding baggage and the others scattered around the valley, Hazen did not concentrate his command on the bank of the river until well past midnight. North of Hazen’s position, Minty spent the entire day looking for the imaginary Confederates that continued to occupy his mind. With two battalions absent, Minty’s command was quite small, but his inordinate fear of a thrust by Forrest’s cavalry kept him from either providing useful information or preparing for a forward movement on 9 September.11

If Crittenden was unsure what to do, there was absolutely no doubt at Rosecrans’s headquarters. Given the timing of messages emanating from Trenton since before midnight, Rosecrans and his principal staff officers had not slept when dawn came. An hour after providing guidance to Crittenden, Rosecrans had Garfield write to McCook. Explaining that Wagner had declared Chattanooga evacuated, that Crittenden was in the process of occupying the city, and that Thomas was driving on LaFayette, Garfield gave McCook explicit instructions: “The general commanding directs you to move as rapidly as possible on Alpine and Summerville, for the purpose of intercepting the enemy in his retreat; move on so as to strike him in flank, if possible.” He explained that the Twentieth Corps could inflict great damage on Bragg if all went as Rosecrans planned. Garfield admonished McCook not to wait for his trains but to leave both his and Stanley’s wagons to follow under a strong guard. At 9:30 A.M., Garfield wrote to Stanley, sharing Wagner’s news and announcing that “a vigorous pursuit has been ordered by the whole army.” Further, Garfield described Rosecrans’s plans for his three infantry corps. Because uncertainty remained about Bragg’s route and because Stanley had been a disappointment so far, Rosecrans and Garfield were unsure about the role to be played by the army’s cavalry. Garfield therefore wrote, “The general commanding leaves your operations to your own discretion, with the general direction to cover our extreme right flank and move upon Rome or such other point as shall do the enemy most serious harm.” The vague set of instructions contrasted strongly with the explicit directions provided to Stanley earlier, an indication that Rosecrans no longer considered his Cavalry Corps a major factor in the rapidly changing situation. Finally, Garfield told Stanley that McCook would protect his trains and that Minty’s brigade would remain under Crittenden’s control for several more days.12

McCook’s headquarters on 9 September was at Long’s Spring, twenty-one miles south of Trenton and two miles north of Winston’s plantation at Valley Head. At 6:45 A.M. he received Garfield’s instructions written at 11:00 P.M. on the previous night. The drive toward Rome and the Western & Atlantic Railroad was canceled; Stanley simply was to make two brigade-sized probes east of Lookout Mountain. McCook was to support those probes with two infantry brigades as far as the eastern foot of the mountain. The remainder of the Twentieth Corps was to prepare for rapid movement because Rosecrans anticipated the Confederate evacuation of Chattanooga. Finally, the message enjoined McCook to hold Winston’s Gap and be alert to any Confederate activity south of his position. In addition to the message to McCook, the courier also brought dispatches for Stanley. The dispatches included Rosecrans’s excoriation of Stanley for his failure to move against Bragg’s supply line, and Garfield’s instructions for the two-brigade probe. It is possible but unlikely that McCook read the embarrassing message to Stanley, given the personal nature of the communication. At any rate, McCook told Garfield at 8:30 A.M. that he had forwarded the dispatches to Stanley, although they would probably not reach him before the cavalry descended the mountain. Perhaps reflecting Stanley’s views, McCook ventured the opinion that all of Wheeler’s cavalry was in their front, making Stanley’s task all the more difficult. He doubted that the small probes could accomplish much, but he was hopeful that some information might be gained. Even if Stanley was unsuccessful, McCook expected to gather intelligence on his own and would send it to army headquarters that night. He attached statements from several recent deserters describing the Confederate cavalry concentration opposite Stanley’s route. However Stanley fared, McCook promised that the Twentieth Corps would act promptly, writing, “I will now mount my horse and go to the gap in person, so as to be better able to superintend things there.”13

Thirty minutes before McCook replied to Garfield, his chief of staff, Gates Thruston, sent messages to all three division commanders. The messages to Sheridan and Johnson simply ordered them to be prepared to move in any direction. A much longer message to Davis closely paraphrased Garfield’s 11:00 P.M. dispatch calling for two infantry brigades to support the cavalry probes into Broomtown Valley. Drafted in haste, Thruston’s dispatch was virtually incoherent. Somewhat later, he crafted a much clearer set of instructions for Davis, ordering him to move with two brigades up Lookout Mountain in support of Stanley’s probes. Thruston was emphatic that Davis’s infantry must not go beyond the eastern foot of the mountain or explore Broomtown Valley. Davis’s remaining brigade was to advance to the top of Lookout Mountain, leaving one regiment at Winston’s plantation to guard the division’s remaining artillery, its trains, and its sick soldiers. Stanley’s trains and convalescents would be protected by Willich’s First Brigade of Johnson’s command, which could support Davis’s guard if needed. Davis was permitted to accompany whichever brigade he preferred. The specific details of cooperation Thruston left to Davis and Stanley. The mission was expected to last only four days, so the troops would carry only three days’ rations. Already prepared to ascend Lookout Mountain, Carlin’s and Heg’s men started early but were forced to wait for the rear of Stanley’s cavalry to clear the road. Through some mistake, both brigades took their trains up the mountain and had to pause while the wagons were sent back to the vast wagon park around Winston’s. They then continued across the top of Lookout Mountain but on divergent paths. Heg and his men headed for a descent of the mountain called Neal’s Gap, while Carlin and his command took the road toward Alpine that descended through Henderson’s Gap. Heg eventually found his road blocked by fallen trees and rocks, ensuring that only Carlin’s troops would make it down the eastern slope before night halted the infantry’s progress.14

Stanley began the day on top of Lookout Mountain near its western edge. Unable to delay any longer, he planned to move with the advance guard, Long’s Second Brigade of Crook’s Second Cavalry Division. At daylight Long’s troopers took the road that eventually led down the mountain at Henderson’s Gap to Alpine. Far behind them, Edward McCook’s First Cavalry Division left Wills Valley around 6:00 A.M. and commenced to ascend the mountain. Long led the way with his Second Kentucky Cavalry regiment, closely followed by his remaining regiments and a section of the Chicago Board of Trade Battery. By standard practice, whenever a road junction or house was passed, scouts left the column to investigate them. During one such investigation, Pvt. John Smith encountered a Confederate soldier at a residence near the road. Commanding the Confederate to surrender, Smith somehow lost his advantage and was killed, his riderless horse returning to the column while the Confederate escaped. Reaching Henderson’s Gap, the Federals suddenly found more Confederate pickets and an obstructed passage. Quickly driving the Confederates back, the column halted while a detail of men spent an hour opening the road. During this pause, a courier arrived with the dispatches from army headquarters that Alex McCook had forwarded from Long’s Spring. Stanley, Crook, Long, and other officers were together waiting for the road to be cleared when the messages, including Rosecrans’s blistering rebuke of Stanley, were read. According to Crook, Stanley was visibly shaken: “Gen. Stanley was taken sick. In fact, he was sick then.” In addition to Rosecrans’s personal attack on Stanley, the messages reduced Stanley’s mission to a simple two-brigade reconnaissance in Broomtown Valley. Already ill, whether from stress, alcohol, or some other malady, Stanley had no choice but to continue the advance down the mountain. As he did so, rumors of Rosecrans’s harsh words began to spread in Crook’s division. With the road now clear, Long’s brigade resumed its march down the mountain.15

Around noon, while a hundred dismounted men completed improvements to the road, 1st Lt. George Hosmer led Company A, Second Kentucky Cavalry regiment, toward the three or four houses comprising the village of Alpine. Behind them the regiment watered its horses at a spring. Hosmer’s company soon passed beyond a slight rise known as Shinbone Ridge. Soon it encountered several Confederate cavalry units, which charged and forced Hosmer to give ground. Hosmer’s call for assistance brought Col. Thomas Nicholas and the dismounted men to his aid. The First, Third, and Fourth Ohio Cavalry regiments also rode to the front, along with staff officers, servants, and orderlies from brigade headquarters. Passing beyond Shinbone Ridge, the noncombatants found themselves in the midst of a sharp firefight and hastily fled to the rear. The panic almost broke the remainder of the Second Kentucky, but Lt. Col. Elijah Watts steadied his command and took it forward. East of Shinbone Ridge, Watts found broad open fields gradually rising toward a wooded area where the Confederates were standing firm. In the midst of the field, Hosmer’s company held a slight knoll forward of the Federal line. Crook now took charge of the action, and sent the Ohio regiments to the right while the Second Kentucky formed on the left of the road. The Confederates contested the ground briefly before the threat to their flank became too difficult to ignore. With a section of the Chicago Board of Trade Battery and Watkins’s Third Brigade arriving, the Confederates withdrew on two different roads. As darkness neared, Crook scouted on one road with some of Long’s men, while Watkins investigated the other. Finding significant numbers of Confederates blocking their way, the Federals withdrew to Alpine, where Carlin’s brigade joined them. At a cost of four killed and eleven wounded, Stanley had gained the Alpine crossroads, twelve prisoners, and several captured dispatches, but little else.16

During the time that the Cavalry Corps was working its way down Henderson’s Gap and securing Alpine, Alex McCook endeavored to support Stanley’s efforts. As he had promised, in midmorning he ascended Lookout Mountain and found Davis’s two brigades at a road junction just beyond the crest. Garfield had told Stanley to send a cavalry brigade on each road, but Stanley was well beyond the junction when the orders arrived, so all of the cavalry had gone toward Henderson’s. Thus Heg’s command continued toward Neal’s Gap alone, although Stanley promised to send a brigade toward Neal’s Gap from Alpine via the floor of Broomtown Valley. Believing he had done all he could to support the cavalry, McCook started back down the mountain, intending to return to his headquarters at Long’s Spring. On his way, he stopped at Winston’s plantation and visited Sidney Post, commanding Davis’s First Brigade. After conferring with McCook, Post sent the Twenty-Second Indiana, Fifty-Ninth Illinois, and Seventy-Fifth Illinois Infantry regiments up the now well-worn road up to Winston’s Gap. The Seventy-Fourth Illinois Infantry regiment remained at the foot of the mountain to guard the division’s artillery and trains. Having thus arranged for Stanley to be supported, for Davis’s southern flank to be guarded, and for the trains to be protected, McCook returned to his headquarters at Long’s Spring. From there he wrote to Garfield at 4:00 P.M. According to McCook, Stanley believed that his modification regarding Neal’s Gap would still meet Rosecrans’s instructions. Further, McCook thought that Stanley’s force of 5,800 troopers was sufficient to “whip all before him.” Although McCook admitted that he did not know Stanley’s specific orders, he ventured the opinion that Stanley’s objective was Summerville or possibly LaFayette. McCook had no knowledge of the fight at Alpine or of Stanley’s rapidly deteriorating physical condition. Nor did he know that Heg’s command had been stopped by major obstructions in the Neal’s Gap road. To McCook, it appeared that all was going well, and he so reported to Garfield.17

Around 6:00 P.M. McCook received Garfield’s 9:30 A.M. dispatch reporting the fall of Chattanooga and Rosecrans’s orders for a vigorous pursuit. The Twentieth Corps was to move as rapidly as possible over Lookout Mountain toward Alpine and Summerville without waiting for its trains. Responding at 6:35 P.M., McCook promised to march at 3:00 A.M. the next morning: “I will do my best, and will have Johnson’s division and two brigades of Davis’ at Alpine to-morrow night, and Sheridan will be on top of the mountain.” McCook complained about having to protect Stanley’s trains but promised to get them moving as well. In passing, he noted that Garfield’s dispatch had been nine hours in transit, which accounted for his late start. McCook also offered the testimony of a civilian named Taylor, who had been informed by a man named Robertson that Bragg’s army was moving by both road and rail to a concentration point at Rome. In closing, he promised to communicate with Thomas as soon as he was east of Lookout Mountain and report to Rosecrans via Winston’s as often as possible. At 7:40 P.M. McCook ordered Johnson, whose camps lay near Long’s Spring, to move at daybreak with his entire command to Winston’s. There he was to leave his baggage and supply wagons with Post and ascend the mountain with only his ammunition train. McCook expected Johnson to reach the eastern side of the mountain by the end of the following day. He wrote in similar vein to Sheridan at 8:15 P.M. Sheridan was to move at daybreak to Winston’s and ascend Lookout Mountain, halting two miles beyond the crest. Finally, Post received instructions to get Davis’s guns and wagons on the road at 3:00 A.M. so as not to delay Johnson and Sheridan. Post then was to begin moving all the Twentieth Corps transportation and that of the Cavalry Corps up the mountain. Contrary to what Rosecrans would later claim, McCook’s orders clearly required him to take his entire corps to the eastern side of Lookout Mountain, and he intended to do so promptly.18

At 10:00 A.M., in a dispatch to Thomas, Garfield confirmed that “a general pursuit of the enemy by the whole army” was what Rosecrans desired. Summarizing the orders to Crittenden, Wagner, and McCook, Garfield instructed Thomas “to move your command as rapidly as possible to La Fayette and make every exertion to strike the enemy in flank, and, if possible, to cut off his escape.” He promised that Wilder would return to Fourteenth Corps control when the Federals reached LaFayette. With Crittenden entering Chattanooga Valley and McCook struggling across Lookout Mountain into Broomtown Valley more than forty miles apart, Thomas would have to cross Lookout Mountain quickly to connect the army’s widely separated flanks. Thomas, however, was not a man to hurry. With a steep pull facing any unit ascending Lookout Mountain at Johnson’s Crook, he saw no reason to rush the entire corps to the foot of the mountain, only to have the divisions wait interminably for their turn to ascend the rough road. Negley’s Second Division was ready to descend the eastern slope of Lookout, but his trains would take all day to reach the valley floor. Baird’s First Division was just starting to ascend the western slope, while King’s brigade had not yet crossed the river far in the rear. Reynolds’s Fourth Division remained camped at Trenton and the Empire Iron Works. Brannan’s Third Division was camped around Cole’s Spring, five miles north of Trenton. With two divisions already struggling on the mountain, Thomas saw no need to hurry Reynolds and Brannan southward to Johnson’s Crook. Thus the Third and Fourth Divisions of the Fourteenth Corps did not leave their camps on 9 September, Rosecrans’s “vigorous pursuit” order notwithstanding. They did receive warning orders to move on the next day, and Reynolds moved his headquarters a short distance southward to Cureton’s Mill, but nothing more was done. Thomas himself left Trenton and rode southward toward Easley’s plantation, to which his headquarters train was already moving.19

From the top of Stephens’s Gap, Negley surveyed McLemore’s Cove, a checkerboard of small fields, pastures, and woodland. Formed by Lookout Mountain on the west and a spur of Lookout named Pigeon Mountain on the east, the V-shaped valley was essentially an eighteen-mile cul-de-sac with its open end to the north. Entry into the valley was by Dougherty’s Gap in the south, Stephens’s and Cooper’s Gaps in the west, a series of four gaps in Pigeon Mountain (Blue Bird, Dug, Catlett’s, and Worthen’s) to the east, and the open northern end only a few miles south of Lee and Gordon’s Mill. Both West Chickamauga Creek and Missionary Ridge had their origins in McLemore’s Cove. From Negley’s position, the road from Stephens’s Gap to LaFayette led straight across the floor of the cove to Dug Gap. At that point McLemore’s Cove was six miles wide, and LaFayette was approximately five miles east of Dug Gap. On the morning of 9 September, Negley knew nothing of events at Chattanooga, or of Rosecrans’s decision to begin a headlong pursuit of Bragg’s army. Instead, that morning he was governed by his orders of the previous night, which specified that he was to secure the top of the mountain while moving his division to its eastern foot. Told to move at 8:00 A.M., Negley did so promptly, sending Stanley’s Second Brigade down the rough track that had been reconnoitered on the previous day. Stanley moved cautiously and took several hours to reach the valley floor, near homesteads owned by Jesse Stephens, Amanuel Rogers, and Wiley Bailey. At the same time, Beatty’s First Brigade completed its descent of Cooper’s Gap, three and a half miles north of Stanley’s route. Beatty then marched southward along the foot of Lookout Mountain until he joined Stanley on the Stephens and Rogers farms. By 4:00 P.M., when most of Sirwell’s Third Brigade arrived, Negley’s division was essentially complete. Only one regiment was absent, assisting the division’s trains on the mountain. An hour later, even the trains arrived in the valley.20

The view from Negley’s new position was both breathtaking and frightening. To his rear was the frowning wall of Lookout Mountain, looming 1,200 feet above him. The mountain was a serious obstacle to the arrival of reinforcements and a possible trap for his division if he had to retreat in haste. To the east, bands of forest clothed several small ridges approximately 150 feet in height blocking his path, the most prominent being Missionary Ridge. Although they held a few slaves, the cove’s inhabitants were Unionist in sympathy, offering essentially correct information about Confederate strength and movements in the immediate area. At 1:30 P.M., before his concentration was complete, Negley informed Thomas that the citizens reported a large Confederate force of all arms gathered just beyond Pigeon Mountain around Dug Gap. Negley’s own scouts had traded shots with Confederate cavalrymen as the Federals slowly pushed eastward beyond the first small ridge. There, at a crossroads named for Wiley Bailey, another slaveholding Unionist, a large body of Confederate cavalry stood in formation. Clearly, Negley’s presence was known to the Confederates. In order to learn more, Negley decided to push his defensive perimeter forward. Lacking cavalry of his own, he gathered twelve mounted men from his headquarters under Lt. Charles Cooke, an aide, and sent them forward. He ordered Stanley to take the three regiments of his brigade forward as well. The Confederate cavalrymen, a portion of the Fifty-First Alabama Cavalry regiment, gave ground easily in the face of Stanley’s advance. Stanley’s infantrymen and Cooke’s detachment chased the Confederates a mile beyond Missionary Ridge until they rallied at West Chickamauga Creek. With night approaching and Stanley’s position seriously exposed, Negley elected to return Stanley to the division’s defensive perimeter near the foot of Lookout Mountain. He left some pickets to occupy the crest of Missionary Ridge east of Bailey’s Cross Roads.21

Upon returning to his headquarters at Jesse Stephens’s spring, Negley pondered his situation. Earlier he had been told of a large concentration of Confederates just east of Pigeon Mountain. Now, Wiley Bailey offered a different assessment. Bailey claimed that he had just returned from Ringgold and along the way had seen large numbers of soldiers and wagons, all allegedly heading for Dalton. According to Bailey, “The general impression among the citizens was that Bragg was falling back to Rome and Atlanta, and that Breckinridge’s command was left to bring up the rear.” Bailey saw only a handful of regiments at LaFayette and only the Fifty-First Alabama Cavalry regiment west of the town. If true, such an assessment represented good news, because Negley received new instructions shortly after 8:00 P.M. His new orders required him to march on LaFayette on the next morning with or without his trains. He was told that all of the other divisions of the corps were under movement orders as well. Negley acknowledged receipt of the order at 8:30 P.M. and promised to move promptly toward LaFayette at 8:00 A.M. He concluded, “All the information I have received this evening from my scouts and others induces the belief that there is no considerable rebel force this side of Dalton.” That being the case, Negley was unconcerned that Baird’s two brigades remained on the opposite side of Lookout Mountain, at least twelve hours of difficult marching behind him. Nor was he concerned that Reynolds’s two brigades around Trenton, fourteen miles and a mountain from him, and Brannan’s three brigades, nineteen miles away and also beyond Lookout Mountain, had not yet begun to move. Even though Negley was not told about Bragg’s departure from Chattanooga, both Reynolds’s and Brannan’s men received the joyous news during the night. Some soldiers wondered why their commands were not already in motion toward the fleeing enemy.22

In contrast to the Fourteenth Corps, on 9 September Granger’s Reserve Corps was far more active. Daniel McCook’s Second Brigade of Morgan’s Second Division marched from Stevenson to Bridgeport during the afternoon, although one regiment remained far behind near Huntsville. Their place at Stevenson was taken by Whitaker’s and Mitchell’s brigades of Steedman’s First Division. Although scenic, their march from Anderson Station was tiresome because of the extreme heat and ubiquitous dust. Some soldiers were entranced by the high mountains surrounding them, but most were disappointed when they reached Stevenson. The small village consisted of twenty nondescript buildings clustered along a single street dominated by the two railroad stations and the hotel. Far more imposing were the massive piles of supplies being deposited in dumps along the railroad for the army’s future use. Even though the main army had departed, the town was still full of soldiers. Tillson’s First Brigade of Morgan’s command served as garrison, a company of Charles Thompson’s African American regiment worked around the depot, empty wagon trains and their escorts were constantly arriving from across the river, and King’s brigade of the Fourteenth Corps was nearby at Bolivar. Gordon Granger himself was on his way from Nashville, in company with Assistant Secretary of War Charles Dana. When Granger arrived that evening, he found a new message from Rosecrans. It announced Chattanooga’s fall and gave Granger detailed instructions for his subsequent operations. Rosecrans told Granger to send King’s brigade forward, build fortifications to protect the Bridgeport bridges, provide forage for the trains shuttling between the army and the river, and organize the army’s rear so that Granger himself could join the main army with part of his corps. Perhaps aware of Granger’s occasionally dilatory tendencies, Rosecrans admonished him, “Bend every energy to the prompt execution of these things.”23

Having put virtually his entire army into motion by 10:00 A.M. on 9 September, Rosecrans and his senior staff rested for much of the day. They had been up all night, first because of Rosecrans’s nocturnal habits, then because of Wagner’s glorious news, and finally because of the need to send orders directing a “vigorous pursuit” to the army’s far-flung parts. Rosecrans, Garfield, and several others then must have caught a few hours of fitful sleep after seeing Thomas off toward Johnson’s Crook in midmorning. Calvin Goddard found time to telegraph his wife about the evacuation of Chattanooga but did not sign another message until after nightfall. Young 1st Lt. Henry Cist shared the good news in a letter to his mother: “You can well imagine our feelings at this gratifying result and our General feels the best of all.” During much of the day, the limited business conducted at headquarters fell to aides Frank Bond, Henry Thrall, and James Drouillard. The latter attempted to have John Purcell, archbishop of Cincinnati, travel to Chattanooga via Shell Mound, but the archbishop’s party was already on the way to Trenton in three ambulances with the army’s returning chief engineer, St. Clair Morton. That evening, the headquarters was once again fully staffed. At 7:40 P.M., Goddard arranged transportation for Charles Dana to Chattanooga on the next day. Less than an hour later, Rosecrans sent his daily report to Halleck. After all the harsh words exchanged between the two men over the pace of the campaign, it must have been gratifying for Rosecrans to write, “Chattanooga is ours, without a struggle and East Tennessee is free. Our movements on the enemy’s flank and rear progress while the tail of his retreating column will not escape unmolested.” This simple statement belied what a glorious day it had been for Rosecrans. Chattanooga was his, the enemy appeared to be in disorderly flight, the army’s supply line was secure, and the cost was minuscule. The army’s staff had already begun to plan Rosecrans’s triumphal entry into Chattanooga on the morrow.24

Like Rosecrans, Bragg spent a restless night as 9 September opened for the Army of Tennessee. Just before midnight he had issued orders for his infantry to continue marching toward a concentration near LaFayette in the morning. Throughout the night Col. Edmund Rucker forwarded a series of reports that showed the Federals slow to capitalize on the Confederate departure from the river. That slowness gave Bragg time to consider his next move. Martin’s frantic report, which forecast a Federal tide washing across McLemore’s Cove and lapping at the crest of Pigeon Mountain, told Bragg that such a Federal threat presented both a risk and an opportunity. If the Federals were in McLemore’s Cove in strength, they could seize LaFayette or exit the cove at its northern mouth and approach Bragg’s position at Lee and Gordon’s Mill. Either way, the Federals potentially threatened Bragg’s hope to wrest the initiative from the Army of the Cumberland. If the Federals in McLemore’s Cove were relatively few and remained quiescent, however, they offered an opportunity to defeat Rosecrans’s army in detail. Bragg urgently needed more information on the widely scattered parts of Rosecrans’s army. At 5:30 A.M., he decided to modify the movement orders he had issued before midnight. Kinloch Falconer, one of Brent’s assistants, at that hour canceled the movement of Polk’s Corps. Scheduled to move within the hour, Hindman’s Division was halted just in time. Cheatham’s Division, ordered to march at 8:00 A.M., had more time to react to the new directive. Cryptically, Falconer told Polk that further instructions would soon arrive. The orders for the remainder of the army remained unchanged. Hill was to continue his march to LaFayette from Rock Spring, Walker was to secure the army’s trains behind Taylor’s Ridge and continue to LaFayette as well, while Buckner took Hill’s old position at Rock Spring. With Polk’s Corps remaining at Lee and Gordon’s Mill, by the end of the day the Army of Tennessee would be arrayed on a north-south line thirteen miles in length.25

While he awaited new information, Bragg assigned Brent and Falconer to build a cordon around the northern and eastern sides of McLemore’s Cove while at the same time completing the army’s concentration. The first order, at 7:00 A.M., went to Harris Mauldin, whose Third Alabama Cavalry regiment was to head southward east of Lookout Mountain and throw a screen across the mouth of McLemore’s Cove. Mauldin would no longer be subordinate to Rucker but would report directly to army headquarters. Thirty minutes later, Falconer ordered Polk to establish a line of infantry pickets from Snow Hill westward to James Gordon’s property at Crawfish Spring. From there Polk’s men would eventually connect with Mauldin’s troopers. Also at 7:30 A.M., Brent wrote to Hill. Still reliant on Martin’s overwrought message of the previous day, Bragg feared that the Federals in McLemore’s Cove had already seized Pigeon Mountain. Thus he wanted Hill to picket the road leading from LaFayette to Dug Gap and another road diverging from the main Gordon’s Mill–LaFayette road at the house of Dr. Peter Anderson. The latter road entered McLemore’s Cove through a low pass in Pigeon Mountain known as Worthen’s Gap. At 8:00 A.M. Brent instructed Wheeler to use Martin’s Division to establish a picket line in McLemore’s Cove from Lookout Mountain to Anderson’s house as soon as Wheeler or Forrest arrived at LaFayette. In peremptory language, he forbade Wheeler from beginning a raid, as Wheeler had proposed earlier. At 8:30 A.M., Brent told Walker to bring the army’s trains with him to LaFayette instead of sending them east of Taylor’s Ridge. Similarly, Brent several times modified the role of the brigade guarding the army’s reserve supply and ammunition trains moving toward Dalton. Eventually, as Bragg’s plans evolved, Brent ordered Buckner to move his corps to Anderson’s house as rapidly as possible, bringing the detached brigade with him.26

As Bragg pondered a possible counteroffensive, the army’s rear guard was pressed severely by the advance of the Twenty-First Corps. With Forrest and Armstrong’s Division absent, the cavalry units following the army out of Chattanooga mostly belonged to Pegram’s Cavalry Division. Along the river north of Chattanooga, Pegram’s Brigade still guarded the crossing at Friar’s Island. It was this command that delayed Wilder’s thrust across the river for much of the day. In Chattanooga itself, Rucker held off Wagner’s Federals with his First Tennessee Legion. The bulk of Mauldin’s Third Alabama Cavalry regiment meanwhile guarded the northern end of Lookout Mountain, both on top and on the Wauhatchie-Chattanooga road. Rucker withdrew his pickets around 8:00 A.M., slowly moving back through the town as Federals converged on it from two directions. Some, in fact, waited near the partially completed Fort Cheatham, coolly watching the Ninety-Second Illinois race past them into town. They then withdrew toward Rossville. Simultaneously, Mauldin’s Alabamians were pushed off Lookout Mountain’s lower slope by Buell’s infantry and forced from the top of the mountain by Grose’s brigade. They also headed for Rossville. Pegram’s men remained a little longer at Friar’s Island but departed around noon when threatened by the Ninety-Second Illinois approaching their flank. Around the same time, Rucker informed Bragg that he had been forced from Chattanooga. Rucker reported in person at 2:00 P.M. At that time his command held a position a mile beyond McFarland’s Spring west of the Rossville Gap, and his headquarters was a similar distance east of the gap. An hour later, Mauldin appeared. He reported being driven from Lookout Mountain, losing three men killed and ten wounded. Mauldin complained bitterly that Rucker had given him no assistance. With the army’s rear guard clearly in disarray, Bragg at 3:00 P.M. summoned Forrest to his headquarters for new instructions.27

During the day, with the exception of Polk’s Corps, Bragg’s army gradually concentrated. Hill began the day at LaFayette under the assumption that Polk was following him southward. When Bragg ordered him to guard the road from Anderson’s house into McLemore’s Cove, Hill understood neither its purpose nor its location. Hill’s lack of geographical knowledge was surpassed only by his unwillingness to consult Bragg directly. Instead, he ordered Breckinridge at Rock Spring to contact Bragg personally if the message was equally unclear to him. Also unwilling to seek guidance from a man he despised, Breckinridge apparently understood the requirement and deployed Helm’s Brigade at Anderson’s for much of the day. With Hill’s approval, Breckinridge also permitted his command to cook several days’ rations before continuing the march to LaFayette. In the midst of the process, he ordered the march resumed, and most of the division reached LaFayette in midafternoon. From there, Sgt. Washington Ives, nineteen, of the Fourth Florida Infantry wrote to his father: “We are a dirty tired and naked set for 3/4 of the men have not a single pair of shoes and no drawers, only one shirt, hat and pair of pants a piece. … The whole army is in good spirits but it is bad to see barefoot men marching on such roads. … I tell you it is enough to make you shed tears to see what some of the boys are enduring.” Cleburne’s Division spent most of the day at LaFayette cooking rations. In the afternoon, some regiments moved toward the Pigeon Mountain gaps west of town, where they found no Federals. Behind them, Walker’s Reserve Corps continued its dusty march toward LaFayette, arriving in late afternoon. Similarly, Buckner’s command marched westward from the vicinity of Ringgold. Stewart’s Division took the lead, followed by Preston’s Division. Stewart halted in the evening at Rock Spring Church, not far from Dr. Anderson’s, with Preston nearby at Pea Vine Church. Thus by the end of the day, Bragg’s major elements were within supporting distance of each other.28

Although the army was reasonably well concentrated, scattered units remained separated from their commands. Johnson’s Brigade of Stewart’s Division departed the nearly deserted Chickamauga Station at 8:00 A.M. They ended the day four miles beyond Graysville, not far from Ringgold. Also leaving Chickamauga Station was John Jackman’s detail from Helm’s Brigade, charged with removing the brigade’s baggage by train before the Federals arrived. After waiting all night for a train, the men finally departed Chickamauga Station early on 9 September. At Graysville, five miles down the line, the cars carrying the Kentuckians’ baggage were placed on a siding, leaving the detail to fend for itself. Somehow, Jackman prevailed upon the last train passing through to attach his cars. The train made it to Ringgold safely but was forced to wait there to follow a passenger train filled with refugees. Eventually, Jackman and Helm’s baggage made it safely to Dalton that night. At Dalton, they found everything in confusion. Dalton was a chokepoint where everything evacuated from Knoxville, Loudon, and Cleveland met everything evacuated from Chattanooga. The Seventh Florida Infantry regiment happened to be at Dalton during the day on its way to rejoin its command, Trigg’s Brigade. Forced to commandeer rations without permission on their way from the Hiwassee River, the regiment continued its irregular habits at Dalton, where the men got rations of flour and salt, but no meat. When several men were drafted to load rail cars, they took the opportunity to appropriate a large side of bacon and a box of tobacco for their own use. Seeing their commander’s wife in a standing passenger train, the men serenaded her with “Let Me Kiss Him for His Mother” and “The Homespun Dress.” Much satisfied with their day’s work, the Floridians “went back to camp, took a smoke and turned in.” Not as lucky as the Floridians, the Forty-Eighth Tennessee and Third/Fifth Confederate Infantry regiments, late to be relieved from the river, spent the day following the dusty road through Ringgold toward LaFayette.29

On 9 September Bragg’s cavalry forces remained in disarray. At Summerville, nine miles east of Alpine, Wheeler intended to support Forrest in a reconnaissance up Lookout Mountain. That plan was canceled when orders arrived for Wheeler to concentrate his command at LaFayette, sixteen miles north of Summerville. Wheeler was also instructed to tell Forrest that he should move to LaFayette as well. In response, both Forrest and Wheeler in midmorning headed north, leaving the Lookout Mountain passes picketed by only a handful of men. Thus when Stanley’s advance finally pushed down Henderson’s Gap to Alpine it encountered only detachments from Crews’s and Harrison’s Brigades. Easily routed by Stanley’s overwhelming numbers, the pickets lost few men, mostly to capture. At some point in the afternoon Stanley’s men intercepted three messages from Wheeler, one of them indicating that Wheeler’s headquarters had moved to LaFayette. Upon his arrival at that place, Wheeler received Bragg’s orders to have Martin’s Division picket the northern reaches of McLemore’s Cove. Martin already had detachments in the Cove, especially Col. John Morgan’s Fifty-First Alabama Cavalry regiment. Portions of that unit faced James Negley’s tentative advance beyond Bailey’s Cross Roads late in the day. Although Negley claimed the capture of two soldiers, Pvt. William Dodson later stated that he was the only man taken. As for Forrest, when he received Bragg’s summons in late afternoon to come to army headquarters, he did so immediately. According to one of Buckner’s staff officers who happened to share the road with him, Forrest was angry at Bragg initially but soon claimed he was “all right with the old man.” Bragg instructed Forrest to go to Dalton and resume control of the cavalry on the army’s right flank and rear. With Armstrong’s Division by his side, Forrest would need to bring some order to Pegram’s Division, elements of which were scattered from Rossville to Ringgold to the East Tennessee & Georgia Railroad north of Dalton.30

Throughout the day, Bragg remained at his headquarters adjacent to Lee and Gordon’s Mill, in the midst of Polk’s Corps. The staff issued General Orders, Number 178, which required the baggage of officers below the rank of division commander to be discarded, in favor of carrying more rations for the troops. Bragg wrote to Secretary of War Seddon, agreeing with the government’s decision to hold Cumberland Gap and explaining why he left Chattanooga: “Rosecrans’ main force had obtained my left and rear. I followed and endeavored to bring him to action and secure my connections. This may compel the loss of Chattanooga, but is unavoidable.” (Neither Bragg nor the authorities in Richmond were aware that, at that very moment, John Frazer was surrendering the Cumberland Gap garrison unconditionally to Burnside’s forces.) At some point during the afternoon, Bragg and Polk had lunch together. Polk’s two divisions, meanwhile, idled in camp. Cheatham’s Division was treated to a patriotic speech of considerable duration by Governor Isham Harris of Tennessee, who was traveling with the army. With time on their hands, Polk’s soldiers cooked rations for the next two days but also became rowdy, causing Polk to forbid the unauthorized firing of guns in camp. When Rucker appeared and acknowledged being driven from Chattanooga, Polk assigned an infantry regiment to assist in picketing the army’s rear. Around 5:00 P.M. a fusillade of shots from the direction of Crawfish Spring caused momentary alarm at corps headquarters. An order placing Smith’s Brigade under arms was soon canceled when the cause was found to be soldiers shooting hogs. In the process, Smith himself was found to be in a drunken rage, requiring the intervention of Lt. William Richmond of Polk’s staff, Capt. John Harris of Smith’s staff, and Col. Alfred Vaughan Jr., the senior regimental commander. Clearly, Polk’s command was not well in hand on the evening of 9 September. Polk himself was debilitated that day by a bout of rheumatism.31

Had he known that large reinforcements were finally moving toward him, Bragg might have felt more sanguine about the coming battle he expected near LaFayette. Nearest at hand were the two brigades sent by Johnston from Mississippi. During the day major elements of both Gregg’s and McNair’s Brigades reached Montgomery. There the all-rail route from Mobile and the water/rail route through Selma converged, creating a significant traffic bottleneck. The shortage of locomotives and cars caused most of the units to remain in Montgomery for the night, giving many men an opportunity to attend the theater. In Virginia a much larger group of soldiers also was beginning to ride the rails. Because Hood’s Division had reached the railheads first, Quartermaster General Lawton notified McLaws that his division would have to wait at Hanover Junction until at least three of Hood’s brigades were dispatched southward. Thus, while Hood’s troops rolled south, McLaws’s four brigades did no more on 9 September than establish camps near the junction and relinquish their wagons and teams. Although the Army of Tennessee was already grossly deficient in field transportation, Longstreet’s First Corps would be bringing none to northern Georgia. Meanwhile, the Railroad Bureau scrambled to gather additional locomotives and rolling stock. The limited capacity of the railroads involved had caused Sims to divide the route southward at Weldon, North Carolina, where Capt. Hiram Troutman was in charge. Initially, Troutman was not told of either the magnitude of the movement or the destination of the troops. After frantically querying his counterparts at Richmond and Petersburg, he received the necessary information and began to assign the arriving troops to different routes. Some were to travel on the Raleigh & Gaston Railroad to Raleigh, thence onward to Charlotte, and finally into South Carolina. Others were to take the Wilmington & Weldon Railroad to Wilmington before also entering South Carolina.32

Benning’s Brigade was the first of Longstreet’s units to arrive at Weldon. The command had departed Richmond before dawn on 9 September and reached Weldon in late morning. Finding no trains immediately available for the Wilmington line, Troutman decided to send the bulk of Benning’s men via Raleigh. The two available trains of the Raleigh & Gaston Railroad could only accommodate three of Benning’s four regiments, some 1,200 men, so the 350 men of the Fifteenth Georgia Infantry regiment remained at Weldon. That unit was shifted to the Wilmington corridor at 4:00 P.M. when the Wilmington & Weldon Railroad’s trains began to appear. Troutman also informed his counterparts at Raleigh and Wilmington that 1,500 troops would leave Weldon daily, half in the morning and half in the evening. That estimate halved the number of 3,000 per day shipped from Richmond that Major Sims had been using. Troutman had hardly accommodated the last of Benning’s command when Robertson’s Brigade began to arrive at Weldon. With Wilmington & Weldon equipment now available, Troutman informed the Wilmington quartermaster that Robertson’s 1,800 soldiers would leave Weldon at 11:00 P.M. Robertson’s men had not spent much time in Richmond but were there long enough for some to become intoxicated and disorderly before their departure. More mischief occurred in Raleigh, where soldiers of Benning’s command destroyed the office and equipment of the Raleigh Standard, an anti–Davis administration newspaper. While editor W. W. Holden cowered in the executive mansion, Governor Zebulon Vance and Lt. Col. William Shepherd, commander of the Second Georgia Infantry regiment, quickly restored order. The chastened rioters returned to the railroad station, some carrying printer’s type in their pockets. Benning’s men departed Raleigh for Charlotte shortly after midnight, but repercussions from their actions continued to spread in Raleigh for several days.33

Around the same time that the false alarm occurred in Polk’s Corps, George Brent wrote in his diary, “Up to 5 PM no intelligible information from the other side of Lookout Mt.” Polk’s aide William Richmond wrote in similar vein: “We are in utter darkness so far as the enemy’s whereabouts in force and his movements are concerned.” Rucker had kept Bragg apprised of the large Federal force that had occupied Chattanooga and pushed his cavalrymen east of Missionary Ridge. Wheeler, however, had done little to provide clarity on the Federal threat at Alpine. Indeed, the most recent information from Wheeler’s scouts was contradictory and outdated. Bragg had long been concerned about Wheeler’s inability or unwillingness to probe the Federal positions aggressively, even sending Forrest to gain what Wheeler apparently could not. Now, with a clear threat developing in McLemore’s Cove, Bragg had called Wheeler to LaFayette, removing him from the developing situation at Alpine. Still, the tentative Federal probe east of Lookout Mountain, and the slowness with which it developed, gave Bragg time to look elsewhere for an opportunity to strike part of Rosecrans’s army. At some point after nightfall, Bragg finally received actionable information from Martin’s cavalrymen in McLemore’s Cove. A courier, apparently Maj. Augustus Johnson of the First Alabama Cavalry regiment, brought word from Martin that a force of approximately 5,000 Federals had reached the foot of Lookout Mountain via Stephens’s and Cooper’s Gaps and had halted there. Unlike his message of the previous day, which had forecast the loss of both McLemore’s Cove and Pigeon Mountain, Martin’s new report brimmed with optimism. A sizable Federal force had incautiously entered the cul-de-sac of McLemore’s Cove and now stood with its back to Lookout Mountain, which would delay any possibility of rapid reinforcement if it were to be assailed. Martin thus saw an opportunity for a Confederate counterstroke and suggested it to Bragg in what he later described as “a somewhat lengthy communication.”34

The fortuitous arrival of accurate information from McLemore’s Cove galvanized Bragg into action. He saw at once that his army was positioned to strike a possibly decisive blow against an isolated segment of Rosecrans’s army, while simultaneously protecting his own flanks. The primary instrument for such a blow was Polk’s Corps, although Polk himself was not the man for the task. Cheatham’s Division, supported by Forrest’s cavalrymen, seemed ample to hold the army’s right and rear, leaving Hindman’s Division free to enter the cove. If Hindman passed through Worthen’s Gap and moved southward, he could assail the left flank of the unsuspecting Federal force. Hill’s Corps already had Cleburne’s Division guarding Blue Bird, Dug, and Catlett’s Gaps in Pigeon Mountain. Cleburne could fix the Federals in front while Hindman struck them in flank. Faced with overwhelming numbers and trapped against the forbidding wall of Lookout Mountain, the Federals could be destroyed or dispersed into the southern reaches of the Cove. Either way, a significant portion of Rosecrans’s army would be removed from the campaign. Although his son many years later claimed that Polk had suggested the plan, there is no other evidence of that. Indeed, a subsequent message indicates that Polk was only informed of the movement as it was being executed. At any rate, at 10:00 P.M. Mackall instructed Hindman to place his command under arms and called him to army headquarters. Hurriedly alerting his brigade commanders to be ready to march in an hour’s time, Hindman hastened to Lee and Gordon’s Mill from the vicinity of Snow Hill. There he learned that some 4,000 or 5,000 Federals were camped at the foot of Stephens’s Gap, while another unknown number was at Cooper’s Gap. Bragg ordered Hindman to enter McLemore’s Cove and engage the Federal forces there in cooperation with part of Hill’s Corps. The junction of the two Confederate forces was expected to occur in the vicinity of Davis’s Cross Roads, midway between Missionary Ridge and Pigeon Mountain.35

At 11:45 P.M. Kinloch Falconer issued Hindman’s and Hill’s written instructions. Hindman’s orders required him to meet Hill’s contingent at Davis’s Cross Roads and, if he proved to be the senior officer present, to lead the united force toward Stephens’s Gap. Hill’s orders varied slightly. If Hill chose to lead his contingent personally, he would command the expedition as ranking officer; if Hill did not lead Cleburne’s Division forward from Pigeon Mountain, Cleburne would be subordinate to Hindman. Because the decision to attack was conceived so hastily, Bragg had no time to consult Hill. Therefore, he deferred to Hill’s rank, and Falconer drafted the instructions accordingly. In case Hill was unable to provide troops for the expedition, he was to notify Hindman. Hill was also to provide a cavalry force to screen his advance because Hindman had no cavalry of his own. Finally, Hill’s orders made no mention of a Federal force at the foot of Cooper’s Gap. Both messages were dispatched just before midnight. Hindman received his orders directly, but a courier had to carry Hill’s orders through the night thirteen miles to LaFayette. Prior to the arrival of his orders, Hill would have no inkling that Bragg was planning an attack and that his troops were to participate. As his men prepared to move, Patton Anderson rode in search of Hindman. He finally found the division commander studying maps with Mackall. Told of the Federal dispositions, Anderson openly expressed concern about the force of unknown size at Cooper’s Gap, which would be on Hindman’s right when he advanced into the Cove. Mackall responded, “That was an important question,” but said nothing more. Clearly Mackall had doubts, but Bragg had made his decision, and Hindman’s orders stood. Not long thereafter, Falconer wrote to Buckner explaining the movement, and to Polk, simply detaching Hindman from Polk’s command. At Snow Hill, more than 7,500 soldiers of Hindman’s Division prepared to go on the offensive. The Army of Tennessee was about to retaliate for the loss of Chattanooga.36

The hot dusty day of 9 September 1863 ultimately would prove to be a turning point in the campaign. Beginning in late June Rosecrans’s Army of the Cumberland had inexorably pushed Bragg’s Army of Tennessee southward. First in the Tullahoma campaign, then in a series of leaps over challenging geographical barriers, and finally through its entry into Chattanooga, Rosecrans had reconquered southeastern Tennessee for the Union. At minimal cost, he had achieved the objectives established by the War Department when he took command in the fall of 1862. Throughout it all, he had maintained the initiative, forcing Bragg to react at a disadvantage. Now, rather than pausing to gather his scattered units, Rosecrans cast aside cautionary advice and elected to throw his army into headlong pursuit of the seemingly demoralized Confederates. That decision, made essentially alone and with little rest early on 9 September, would prove to be a fateful one, because Bragg was not yet ready to concede defeat. Outmaneuvered at Tullahoma, Bragg had safely extricated his army from potential destruction. Withdrawing behind the Tennessee River, he knew that his army could not defend the long river line. His only hope was to wait for Rosecrans to commit himself, then maneuver aggressively in the tangled terrain south of Chattanooga and strike a blow when opportunity offered. Now, on the evening of 9 September, the opportunity to regain the initiative had appeared in McLemore’s Cove. A young staff officer who saw Bragg that day was impressed enough to temper his unfavorable opinion of the army commander. To Lt. Henry Foote Jr., Bragg was “a tall, muscular man, with iron-gray beard, clipped close, a stern mouth, and an iron-looking jaw.” Such a man was not likely to acquiesce in his army’s destruction without at least one more throw of the dice. Chattanooga might have been lost momentarily, but Bragg resolved on the evening of 9 September that it would not be lost without a fight.37