#GoRaceItYourself

WACKY WEEKENDS

THE GETAWAY CHALLENGE

At last, it’s the weekend. That glorious moment, which for many is the carrot dangling at the end of the proverbial stick. It’s our chance to get some mates together, escape the city, get outside and, most importantly, challenge ourselves while having an adventure. And with 64 hours to kill, from 5 p.m. on Friday before we’ve got to be back at work at 9 a.m. on Monday, there is no end of possibilities.

The really fun bit, the element I like most about these challenges, is the brainstorming process, often done over a bottle of wine, in which you come up with that barmy idea that will get the grey matter firing on all cylinders. In short, what I’m proposing is that you become your own race director.

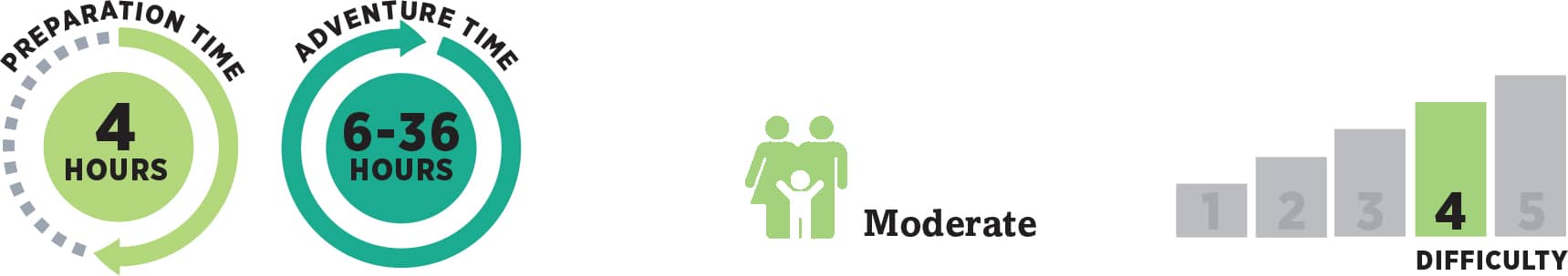

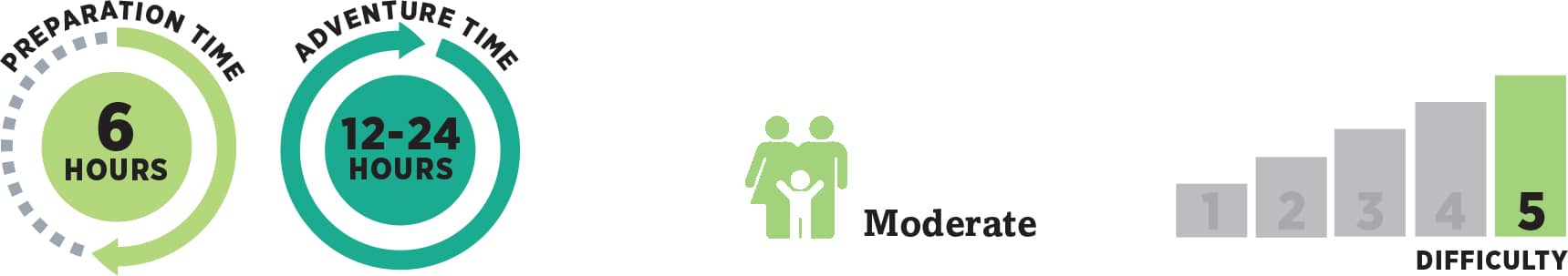

You’ll find that the challenges in this section are a step up from the Midweek Madness – a little bit more difficult and therefore requiring a little more preparation but nevertheless still allowing room for spontaneity. Some of the challenges, like Everesting or YoYo Peaks, require a high level of fitness and aren’t the sort of thing to attempt on a whim – unless you like punishing yourself. But that’s where you set a date in the diary and use some of the other challenges in the book as preparation for those events.

Can it be done? Am I fast or strong enough? Will I make it in time? Where will I stock up on food? How do I get back? Think of these ideas as an extreme microadventure, where it’s less about going slow and enjoying the moment and more about pushing yourself to the limits but under your own terms. You’re in control of when you stop, what route you take and how quickly you need to complete the challenge. And although there needs to be a sense of achievement – whether it’s simply completing the distance or, in cases like Race a Mountain Train, actually winning – you’re not meant to take them too seriously. After all, this is supposed to be fun.

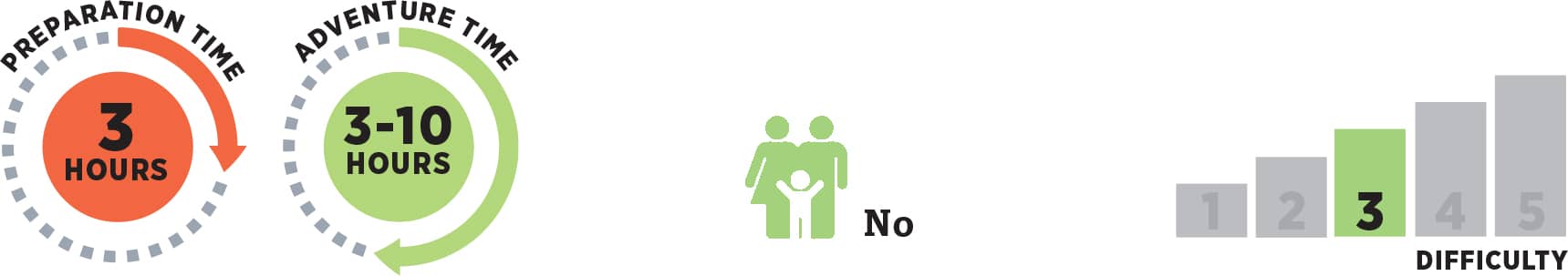

Monopoly Marathons

RACE YOUR WAY THROUGH THE MONOPOLY STREETS

RULES

RULES

1. You can start and finish the run wherever you like, but you must visit all the points on your Monopoly board.

2. Take a photo of yourself at each of the place names to prove you’ve visited them.

KIT

KIT

• Running shoes

• Map

• GPS

• Camera

METHOD

METHOD

As an adult, New Year’s Eve can be a tricky time of year. We’re often pressured to do something special, go out with friends and party the night away, only to wake up on the first day of the year feeling decidedly the worse for wear. But my childhood memories are very different. After a family dinner, we’d sit around the fire as my parents brought out the Monopoly board for our annual game. Some years, I’d be rubbing my hands together with joy if I managed to buy the posh Mayfair or Park Lane and in other years, I’d be cursing my poor fortune for being landed with the less salubrious Whitechapel or Old Kent Road.

Although Monopoly’s origins lie in the United States, it’s now licensed in 103 countries, available in thirty-seven languages and for hundreds of cities around the world, including forty-eight in France, thirty-five in Germany and eight in Spain. And if you can’t find your local edition, you could always create your own customised version with a printer and a little creative licence.

Reminiscing about my childhood, I asked my long-suffering wife if she’d like to have a game of Monopoly with me on New Year’s Eve. She gave me a slightly perplexed look. ‘No, no,’ I explained. ‘This is much better – we’re going to run a marathon around the Monopoly board.’

Now, of course, if you were to play by the rules and make this a true test of endurance, you’d be casting dice, going to jail, spending money and running a lot further than a marathon. Or you could run between the streets in whichever order they appear on the board – equally taxing.

But I’ve saved those ideas for another day. On this occasion, and keen to avoid divorce on New Year’s Eve, we printed out a map and plotted the twenty-two streets, four railway stations and two utility companies from the Monopoly board. All we then had to do was connect the dots – starting and finishing at our home.

A sensible person would argue that for practicality’s sake, it’s probably best not to do this at peak rush hour, let alone on the busiest night of the year when many of the roads are closed except to ticket holders. But in some way, our hare-brained scheme added to the challenge. And what better way to see in the New Year than running a marathon around a Monopoly board and hopefully catching the fireworks at the same time? Plus, we’d not wake up with a hangover!

By the time New Year’s Eve arrives, we are almost tempted to ditch the trainers and grab our bikes (which is another valid option), but we decide to stick to the original plan on the basis that it will be a lot easier to move around the city on foot than by bike. And we are right.

With twenty-eight places to visit, we find ourselves taking sneaky back streets in an effort to avoid the hordes of revellers, tourists or the occasional roadblock. And to mark our progress, we pose for a photograph beside each of the place names, grinning at the camera with childish delight at our exciting game of endurance meets chance.

There’s something exhilarating about following an invisible route – one that only you can see – whether that’s from your map or GPS. And when you consider that the place names on a Monopoly board are often what are considered to be ‘must visit’ locations, this is the ultimate tourist run.

However, our initial exuberance occasionally wanes as tired legs and a lack of carbs gets the better of us. But luckily, this is easily remedied by nipping into the local fish and chip shop for some guilt-free sustenance.

It’s understandable that we receive a few funny looks from passers-by, but upon questioning, any surprise quickly turns into comments of ‘What a brilliant idea’ or ‘I’d love to do that’ as they realise the attraction of running a marathon around the most famous streets of their city.

Arriving home at 1 a.m., having run just shy of 50 kilometres in a smidgeon over 6 hours, we collapse on the sofa and open a bottle of champagne to celebrate. As we toast each other’s good fortune, we both agree it was the toughest game of Monopoly we’ve ever played, but by far the most enjoyable.

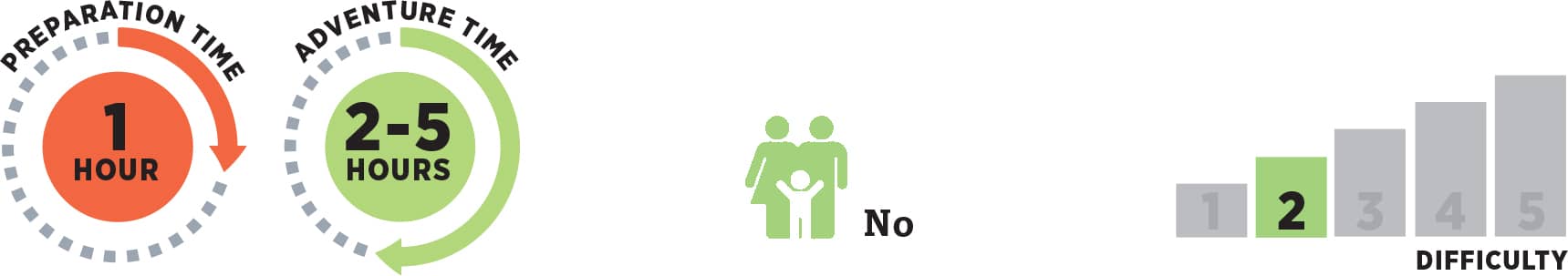

Wild at Heart

CREATE A SWIMRUN ADVENTURE

RULES

RULES

1. This is a self-supported challenge.

2. All lakes/pools/sea should be publicly accessible.

3. Any form of swim aid is acceptable, but you must carry what you use from start to finish.

KIT

KIT

• Wetsuit

• Goggles

• Trail running shoes (lightweight)

• Swim cap

• Hand paddles (if preferred)

• Waterproof map case

METHOD

METHOD

It’s bizarre to think an idea that started off as a drunken bet – to swim and run across the Stockholm Archipelago – has now become a sport that’s one of the most talked about in the world. It’s also one of the fastest-growing. All thanks to two friends, Michael Lemmel and Mats Skott from Sweden, who co-founded the ÖTILLÖ – a 75-kilometre adventure race between twenty-six islands.

When the ÖTILLÖ launched in 2006 (ötillö is Swedish for Island to Island), it was the first event of its kind in the world. Sitting very much on the fringe of endurance sports, it attracted those adventure athletes looking for something new, something fresh and, most importantly, something that sounded bloody difficult. More than ten years later, the ÖTILLÖ has grown in ways its founders could never have predicted, boasting a roster of events all over Europe.

But no one enters a SwimRun event with the idea of setting Personal Bests or chasing an arbitrary time. Rather it’s about ‘moving through nature’, as co-founder Mats Skott once said. And if there was ever a sport where I felt most connected to nature, it’s doing a SwimRun.

The hardest part in planning your own SwimRun is simply getting your head around the concept. Although there are a few similarities, SwimRun is very different from a triathlon in that you’re totally self-sufficient and carry the same equipment throughout the entire race. Which means you’ve got to swim in your trainers and run in your wetsuit.

Most people can’t imagine running more than a hundred yards in a wetsuit, let alone running an ultra marathon. And then there’s the fear of the cold open water. And just to make life increasingly difficult, you’ve got the strange sensation of swimming with your shoes on. On paper, it sounds bonkers. But in reality, it’s one of the most exhilarating experiences you’ll ever have.

Remember, you don’t need any specialist kit to do a SwimRun. If you’ve got an old wetsuit lying around, cut off the legs and arms at the joints – giving you better mobility when you run and lessening the chance of overheating. An old pair of trail shoes will also do – and if you think they’re on the heavy side, drill some holes in the soles to help with drainage. The only other bits of kit that come in handy are goggles and a swim cap.

Don’t worry if you don’t have an archipelago nearby. Instead, why not run between lakes and swim across them? With more than half a million natural lakes with a surface area greater than 10,000m2 in Europe, there is plenty of choice. Finland has the lion’s share with a mind-boggling 188,000 lakes, more than any other country in the world. However, you need only a couple of lakes to create a route – just make sure you have permission.

And if you live in a city, outdoor swimming pools work almost as well. You could create an urban route linking them up, although you might get the odd glance from passing strangers.

Regardless, it’s best not to bite off more than you can chew, so your first SwimRun should be simply getting used to transitioning from water to land and back again using just one lake/pool/reservoir. Working out what kit works and doesn’t, how to carry water and food – it all takes a bit of practice. And that’s part of the adventure. Because after you’ve done your first SwimRun, everything else will feel boring.

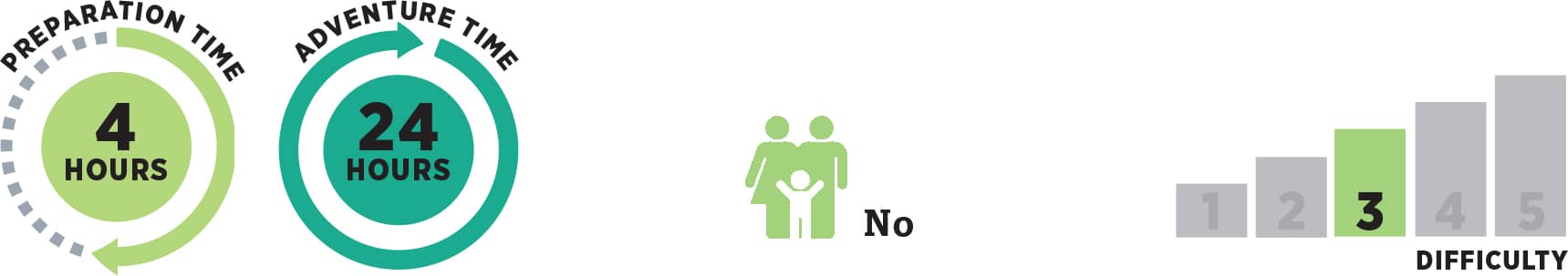

nohtaraM ehT

RUN THE ROUTE OF AN OFFICIAL RACE IN REVERSE

RULES

RULES

1. Make sure you understand the route – on non-race days, it may be busier and need your full attention.

2. Try to start as close to the official finish as possible.

KIT

KIT

• Trail running shoes

• Running pack/vest

• Spare warm clothes

• Water

• Food

• GPS watch

METHOD

METHOD

As Big Ben prepares to strike 4 a.m. on an early Sunday morning in late April, a small group of runners stand beneath it, chatting amiably with each other as they limber up. In just a few short hours and with almost 26 miles behind them, the fastest runners in the world will speed past this very stretch of road on their way to Pall Mall in the hope of calling themselves the winner of the London Marathon.

But this group of runners, some of whom are in fancy dress, are not there to race. They’re waiting for any last-minute arrivals to join them on the ghostly quiet streets that wind their way through 26.2 miles of London. They’re running in the nohtaraM nodnoL. No, this is not a spelling mistake, but London Marathon in reverse. And with Big Ben being the closest they could get to the finish line of the event itself, they’re about to run the route in reverse, finishing in Greenwich where tens of thousands had been nervously waiting to start their own race.

It’s not exactly a new concept. In fact, among the ultra running community there are a growing number of gritty individuals, who every year will attempt what’s known as a ‘double’ – essentially running the reverse route of a race and then turning around to take part in the actual event.

So, if you missed out on a place for your chosen race, especially a big city marathon or one of the world Marathon Majors, why not try them in a different way and on any day, and do nohtaraM ehT? The only thing you’ll not get is a bib number and a medal. Other than that, you’re still running a marathon – worth bragging rights on its own!

Depending upon where you live, almost every city and town will at some point in the year host a race. It doesn’t have to necessarily be a marathon – the same rules apply for a 10k, half marathon or, at the other end of the spectrum, an ultra marathon. Although it’s normally the mainstream marathons that have closed traffic-free roads, even small races have the route signposted the day before. After all, just because you don’t have a race entry, it doesn’t mean that you can’t follow the route. Remember, it’s closed to cars, not pedestrians.

If you choose to race the night before a race, you’ll have to prepare yourself for an early wake-up call, especially if you’re running a marathon distance (or more). You need to make sure you are not in anyone’s way, and leave plenty of time to finish ahead of the race.

Unlike most marathons, for nohtaraM ehT you’ll need to be relatively self-sufficient. The energy stations spaced every mile won’t be open for business at 4 a.m. Nor will there be a ready stream of volunteers handing you bottles of water. Nope, you’ll have to fend for yourself, bringing with you sufficient water to last anything from three to five hours or more. But this is what makes the nohtaraM ehT so attractive.

If you’re looking for a Personal Best, this is probably not the time to try for one. This is a time to spend with friends, enjoy the moment and not think too much. In fact, you should try to do the opposite. In a race like the London Marathon, where the support from the crowds lining the road can actually be an assault on your senses, here you’ll find such peace and quiet that it will be eerie.

As the runners approach Greenwich, they almost blend in with the thousands of other runners making their way to the official start. Most of those with bib numbers on will never in a million years think you’ve just run the route in reverse. But as they nervously wait for their race, unless you’re planning on turning around and running the main event, this is your chance to put your feet up and have a cup of tea – as you watch everyone else prepare to run 26.2 miles.

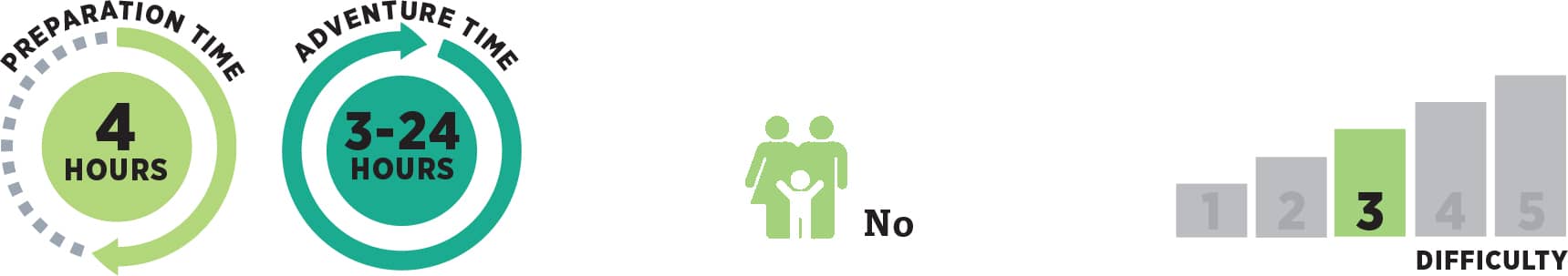

Sea to Summit

RUN OR CYCLE FROM THE SEA TO A PROMINENT HIGHPOINT IN THE REGION

RULES

RULES

1. You must be self-supported during the challenge – which means, no outside assistance that isn’t readily available to anyone else.

2. It must be done in one continuous push. If you’re creating a multiday option, then it should be in consecutive days.

KIT

KIT

• Map

• GPS

• Compass

• Running shoes

• Small running pack

• Water

• Food

METHOD

METHOD

It’s strange how it is so easy to take for granted what is on your doorstep. And how easy it is to forget the simple pleasure of poring over a map: tracking contour lines to their highest points, seeing rivers disappear, or working out just how many miles you are from wild settings like national parks. As I trace my finger around the perimeter of my nearest park, the Exmoor National Park, and note that it has a high point of 1,702 feet at Dunkery Beacon, I realise that it is pretty close to the sea. And it is the same for a number of national parks such as Sierra Nevada National Park in southern Spain and Vesuvius National Park in Italy.

Like magic, routes begin to materialise before my eyes: a mixture of footpaths, waymarked trails, off-beat tracks or quiet country lanes, all leading up to a high point and stretching back to the sea. An adventure is created: from Sea to Summit. What an epic way to spend a day!

Although I could have cycled, for this one I pick the old faithful runners – the high point is quite off-piste for the bike, and the potential of hidden trails and sneaking paths beckon the feet to explore them.

The best thing about Sea to Summit is how the planning is relatively quick and easy. Simply decide how far you would like your run to be (it could easily be a good day’s trek too), find a suitable high point and then measure back to the sea. Preferring to take the opportunity of finding secret avenues, I pick my two points and allow a compass bearing to do the rest – rather than marking out a specific route.

With map and compass in hand, I set off at a pace and follow any street, path or trail that allows me to keep as close to the crow’s line as possible. Of course, if you want to make sure you pick the fastest or most accessible route this can be planned on your map beforehand – it’s certainly the best way to ensure you take in places of interest, perhaps historic monuments or just a good spot for refreshment. For me, this particular challenge is in the spontaneity and the speed: but on another day …

As I’ve guessed from reading the contours on the map, the first half of the route is a relatively gentle excursion. It isn’t until about 5 miles into the route that I am reminded I have picked myself an uphill challenge – the gradient starting to steepen serving as a reminder that this is, after all, a Sea to Summit challenge and I still have to climb about 1,700 feet of elevation in the space of 3.5 miles.

The climb is definitely worth it for the big open skies that are my reward for running through a rather thick period of foliage, making sure to check my map along the way to stay on bearing: it would be all too easy to take the wrong path.

Some 15 minutes later I pop out of the woods and am rewarded with a panoramic view of the town and parkland I have already covered. It’s a booster to push me up the hardest bit to come – the rounded tip of my summit, and my challenge end.

I use the opportunity to relate where I am to the map, trying to identify recognisable features. Always keeping an eye on my energy levels, of course, in terms of how much further and higher I’m going to climb.

Just when I think the climb is going on forever, I suddenly spot my destination – the trig point that marks the highest point in southern England outside Dartmoor. I use up my last bit of energy in a sprint to the highest point marker and turn around to be rewarded with a beautiful panoramic view of the sea. From here I can etch out the route I’ve taken to get here and already start planning the next Sea to Summit challenge – a great way to test the legs and earn a ‘something new’ badge of personal honour.

Race a Mountain Train

TAKE A MOUNTAIN TRAIN UP AND RACE IT DOWN

RULES

RULES

1. The race starts the moment the doors to the train close.

2. You can choose to race the train up or downhill, or even both – whichever one provides the ideal challenge.

KIT

KIT

• Trail running shoes

• GPS watch

• Running vest pack (with room for water if necessary)

METHOD

METHOD

I try to imagine what they must have been thinking in 1908, when they first came up with the idea of building a railway here, on the French/Spanish border in the heart of the Basque Pyrenees.

If I look east, I can see the vast expanse of the Atlantic Ocean, with a sandy line marking the coastline, stretching away to the north of France. To the south of me, the Spanish Pyrenees fall away towards San Sebastian. And to the west, the snowy peaks of the High Pyrenees beckon, reaching out to me with temptation. But right now, I have other plans.

The guidebook suggests that it takes 2 hours to descend the 4.9-kilometre path to the train station below. And with a drop in elevation of 736 metres, it’s not for the faint of heart. If I’m to beat the train, I have just 35 minutes.

‘We’ll see you at the bottom!’ my wife shouts as the train gently starts to move, adding, ‘And be careful.’ Arms waving, and with their faces pressed against the window, I watch as my family and friends slowly disappear, then I snap out of my dream world. I’ve almost forgotten that I have a train to race, and my lack of concentration has given them a tiny head start.

You’ve probably noticed this, but railway tracks tend to be rather flat. And that’s for good reason: trains don’t go uphill very well. To overcome this problem, engineers have come up with all sorts of solutions over the ages, from horseshoe curves to zigzags, but the most popular is the rack and pinion railway, first used in 1868 on the still-functioning Mount Washington Cog Railway in the United States.

It’s different from a funicular (see here), in that rather than using cables and counterweights, the rack and pinion rail tracks have a toothed rail in the centre of the track. This, combined with a cog on the train, allows the train to operate on steep inclines.

Now, it’s worth pointing out that unless you have the limbs and speed of the Swiss mountaineer Ueli Steck, it’s highly unlikely you’ll beat a mountain train going uphill. Having looked at the profile out of the window on my way up La Rhune, I quickly gave up on this idea. However, the descent is a different matter altogether. It’s akin to fell running – where you let gravity do all the work.

So Step 1 is fairly obvious, but the crucial ingredient of this challenge is to find a mountain train. Without one, it’s simply not going to work. Once again, Wikipedia has a list of rack railways around the world, grouped by country – so you shouldn’t have a problem finding one.

The next step is to look at an online map and try to identify your start and finish point, symbolised by the respective train stations. By far the easiest way to do this is to use Strava, and the help of the Global Heatmap to identify if there are any tracks that will take you down the mountain.

Since many of the mountain trains cater for hikers who choose to hike up and take the train down, there’s a good chance you’ll find a track nearby. It’s then simply a case of connecting the dots.

As I follow the yellow arrow-markers down the mountain, I’m having a hard time choosing whether to look at my feet, the spectacular view or the train to my right, where my family are cheering me on from the carriage window. But with the trail being rockier than I anticipated, I decide I like my teeth where they are, and focus my attention on my footing.

Luckily, the path smooths out and I manage to up my pace, keeping an eye on the time and the train, which is disconcertingly far away. But either it is slowing down, or I am speeding up, and I found myself running alongside the tracks – with the train behind me.

With the train station at the Col de St Ignace growing closer, I feel confident, for the first time in 25 minutes, that I will beat it. And sure enough, 32 minutes after setting off, I arrive – one step ahead of Le Petit Train de la Rhune. I’ve done it!

Day Flight Run

TAKE A DAY FLIGHT AND COMPLETE AN ADVENTURE CHALLENGE BETWEEN THE FIRST AND LAST FLIGHT OF THE DAY

RULES

RULES

1. The challenge must be completed within a day.

2. There’s no limit on how long the flight takes, but ideally it should be as short as possible to maximise on the activity you set yourself.

3. Costs should be kept to a minimum.

KIT

KIT

• Running shoes

• Running pack

• GPS watch

• Glasses

METHOD

METHOD

‘Is this your first time to Jersey?’ my seat companion asks, unable to contain his curiosity as he watches me inspect the large map of Jersey that I have unfolded on my tray table.

‘Yes,’ I answer with a certain degree of embarrassment. Despite having flown over the Channel Islands more times that I can count, I’ve never before looked at them as a destination in their own right. And if it weren’t for a casual conversation with a friend from Jersey, I would never have thought about flying to and from the largest of the Channel Islands in day.

If the man next to me is surprised by my first response, he almost spills his coffee when I tell him I am going to meet some friends and then try to run around the island in time for the last flight home.

When I lived in the city, I spent half my time loving it and the rest longing to escape. However, if there’s one advantage to living in a concrete jungle, as opposed to the lush but sometimes remote countryside, it’s being close to a major airport. And thanks to the plethora of budget airlines popping up all over the place, creating healthy competition for the mainstream carriers, it’s becoming increasingly cheap, especially if you fly without luggage.

The first step in a creating a Day Flight Run is to open up your atlas or Google Maps and have a look at where you could fly to within 90 minutes. You’ll often find this information in the back of airline magazines or on the Internet. It was by chance that I noted BA offered a day flight return to Jersey, for a meagre £70. And what’s more, it was only a fifty-minute flight.

As the plane begins its descent, I get my first proper glance of my playground for the day, noting with interest how the majestic coastline to the north is in stark contrast to the urban sprawl around its capital to the south. I hope to run the full 48 miles, but after a moment of reflection and speaking with my friends upon arriving at the airport, we decide to jump in a taxi and head to the other side of the island. Consulting our map, we work out the coastline trail is exactly 26 miles long. So depending upon how quickly we get to our notional finish, we could just keep going if time permits.

There is something magical about an island – whether it’s their feeling of remoteness which encourages a degree of self-sufficiency or simply because it makes you feel like you’re on holiday. Whatever it is, as I run along the stunning cliffs, passing ancient forts, Second World War bunkers and otherworldly sheep, I feel like I’ve properly escaped.

In an ordinary marathon, I’d be eating energy gels and bars. But on this occasion, I decide to leave it to chance, instead pausing at any one of the numerous local cafés and pubs for refreshments – so much more nutritious and satisfying to the palate than a sticky energy gel.

However, my propensity to stop and take photos, indulge in the local culinary delights and chat to the locals we pass, means that despite giving myself a generous amount of time, I need to get a move on, or I’ll miss my flight.

All of a sudden, having spotted our flight making its approach above us, we find ourselves running like the clappers to the taxi I’d pre-booked at the beach finish point. If ever there is a time to be grateful for having hand luggage only, this is it.

An hour later, as the plane takes off, I look down at the island I’ve just attempted to run around. And although I didn’t complete the entire perimeter, I’ve had one of the best days of my life.

So the next time you’re sitting on a plane, take a casual look at the rear of your airline magazine and see where you can fly to in less than 90 minutes. You’ll be surprised by what’s on your doorstep, if only you take the time to look.

Castle to Keep

RUN OR CYCLE BETWEEN CASTLES

RULES

RULES

1. You should be as self-supported as possible. No outside assistance, but stopping at local shops is fine.

KIT

KIT

Running

• GPS

• Running shoes

• Shorts

• Top

• Socks

Cycling

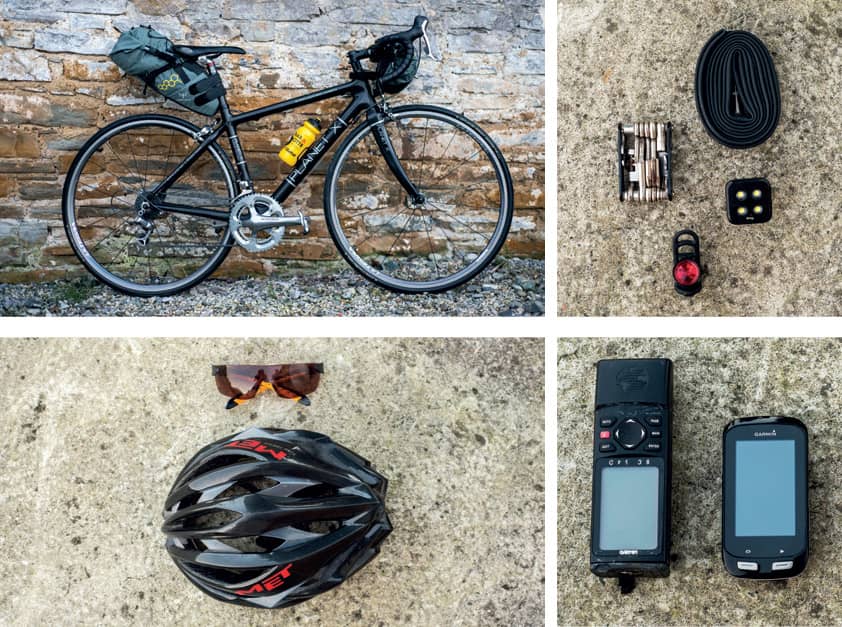

• Bike

• Helmet

• Bike shoes

• Glasses

• GPS

METHOD

METHOD

When I was a child, I desperately wanted to live in a castle. Of course, back then I had no idea of the upkeep involved, the stress of a leaking roof that requires scaffolding 50 feet high or the fact that in winter you’ll long for a decent central heating system and double glazing. No, none of that went through my mind. I was more interested in the history contained within the walls of these fortresses.

In days gone by, the barons, dukes and kings who owned these magnificent strongholds would visit each other’s castles, taking journeys lasting from days to months. When I think of the hundreds of miles many would travel, sometimes in the depths of winter, I can’t but help be impressed. So this challenge is in part inspired by our aristocratic forebears but also by the modern-day steeplechase, whose origins lie in nineteenth-century Britain, where runners would race each other from church steeple to steeple, jumping over a series of obstacles as they went.

When planning a route of this nature, you want to try and make it as interesting as possible. With only a weekend to squeeze your journey in to, there’s no point looking for castles too far apart. In my experience, the best Castle to Keep routes are the ones that recreate an ancient journey or which have an historical connection. It could be two neighbouring castles built to defend against a common enemy (the British or the French, in many cases), and if they’re reasonably close together, they might be perfect for fastpacking (see Hut to Hut) or running between. Or if you fancy becoming the Lord of the Manor for a night, you could make a bicycle journey between any of the 38 castles that have been turned into youth hostels in Germany. All of the perks without the upkeep!

As I was keen to explore my local area and learn new routes, I decided to make a micro bikepacking time trial between some of the principal châteaux scattered around my home in the Pyrénées-Atlantiques. After a short amount of research, I selected five that appealed to me, ranging from the birthplace of Henri IV to a nineteenth-century abandoned fortress built to defend against the Spanish. I plotted the castles on the map and created a circular loop with a few detours, all following the most scenic roads and, where possible, the odd col. By the time I’d made my plan, I was practically shaking with excitement. It felt as though I was off on an historical adventure through time.

What I love about cycling, something that you don’t get so much by running, is how you can cover such huge distances in such a short amount of time. I mapped out a journey of 150 kilometres and completed it in a weekend. Here I was, discovering one charming village after another, giving me plenty of excuses to stop and stock up on croissant and pastries in the local boulangeries. In between, I’d pedal along the quiet country lanes, breathing in the fresh air like a sommelier would sniff a glass of red wine, but my focus was always on the next castle.

Just as steeples were easy for runners to see from long distances, castles are too. The medieval ones are commonly built on hills, not only a perfect place to defend from but a good vantage point. Whereas some of the nineteenth-century châteaux have fabulous towers shooting up into the sky, you only need to head into neighbouring Germany or Austria for true height – the castles here even make Harry Potter’s Hogwarts look small.

Having done my research beforehand, I’d stored some of the castles’ history on my phone, allowing for an electronic self-guided tour before taking an obligatory photo or two and then moving on to the next. Countless villages, five castles and 150 kilometres later, I was almost sad to be coming to the end of my journey. Not only had I learned an enormous amount about the history of the region, but I’d created a wonderful cycle route in the process, perfect to share with my friends.

Peak to Peak

CREATE A RUNNING ROUTE THAT CONNECTS PROMINENT HIGH POINTS

RULES

RULES

1. The start and finish must ideally be at the same place. Try to find a prominent point – a church, town hall, library, or even a café.

KIT

KIT

• Trail running shoes

• Map

• GPS device

• Running backpack

• Food and water

• Waterproof jacket

• Spare warm top

• Emergency blanket

• Whistle

METHOD

METHOD

When I first heard about the Bob Graham Round, a legendary challenge that involves running between the forty-two highest peaks in the Lake District, all within 24 hours, I simply knew I had to do it. For me, and hundreds of other runners, the 66 or so miles of fell running with a backbreaking 27,000 feet of climbing was the ultimate ‘hard as nails’ way to prove to myself that I was a real runner.

However, as I sat upon a rocky outcrop recovering from running through boggy, un-runnable terrain, I realised that I’d bitten off a little more than I could chew. I was some 16 hours and 48 long miles into my first attempt, but I’d clearly not spent enough time chasing chickens, à la Rocky Balboa. Inadequate preparation meant I would have to temporarily retire my gauntlet. ‘Perhaps I should try a smaller version first,’ I thought. A sort of Micro Bob Graham, if you will. And ideally, something not too far away.

In the United Kingdom, where this type of challenge flourishes, there are Peak to Peak challenges galore, from the Paddy Buckley Round in Wales to the national Three Peaks challenge. Indeed, there’s no reason why you have to go between forty-two peaks, when three do just as good a job.

For this type of challenge, it works best on foot, but there’s nothing stopping you from creating a national challenge that involves cycling in between the peaks, before climbing them. Regardless of what you do, you’ll need a map of the local area and a compass. It’s only by looking at a map that you can appreciate the terrain and, more to the point, identify the high points.

A good starting point, and a way to stop you going bonkers looking at the endless possibilities, is to contain your challenge within the lists that peak baggers so helpfully create for us. You might make a route between ten of the 212 peaks that stand 3,000 metres high in the Pyrenees. Or if you want to get pedantic, you could limit your search to those peaks with a prominence of 600 metres in the Alps.

As with so many of the challenges in this book, when trying to make your own Peak to Peak round, one of the key ingredients is a competitive streak. For some, it’s enough of a challenge to make it from one peak to the next. But if what if we set a time limit?

Just as a mountain race would have a cut-off, you can create an arbitrary time in which to complete it: 6 hours, 12 hours, 24 hours or longer. It’s simply a way of controlling how much time you spend doing something before it becomes unreasonable. But then again, until you try something, you don’t actually know.

Another option, and perhaps my favourite kind, is a mini Peak to Peak. This essentially involves an out and back hill climb that starts and finishes in a town/village. Your start point is a church, town hall or other prominent building. You then find the two closest high points, plot a route that takes you there and challenge people to get to the two summits and back within a set amount of time. Better yet, try and encourage a local café/restaurant or even the tourist office to reward individuals with a token gift – a free coffee, for instance – for those who complete the challenge within the cut-off.

I may not have succeeded in completing the Bob Graham Round on my first attempt, but I still managed to have a fantastic adventure and ticked off almost thirty of the peaks in the process. And it’s important to remember that the whole point of an adventure is that the outcome is unknown. Until we try, we never know what’s possible.

Race the Sun

WHAT CAN YOU FIT IN BEFORE THE SUN SETS?

RULES

RULES

1. The race starts and finishes at the official time the sun rises and sets according to the sunrise equation.

2. The challenge should be a journey, whether that be climbing a mountain or running around a large lake.

3. There should be an element of risk, making use of as much of the daylight hours as possible.

KIT

KIT

Cycling

• Road bike

• GPS device

• Windcheater/gilet

• Helmet

• Bike shoes

• Food and water

Running

• Running shoes

• Running pack/vest

• Food and water

• GPS watch

METHOD

METHOD

‘Do you think we’ll make it?’ my friend asks, as we nervously wait for the start of our pop-up ‘ultra’ race against the sun. Although it’s beginning to get light due to the magical properties of morning twilight (sometimes referred to as ‘astronomical dawn’), the sun hasn’t officially poked its head above the horizon yet. That will happen at precisely 6:35, at which point we’ll have 11 hours, 43 minutes and 30 seconds to run the 60-mile off-road route I’ve mapped out from London to Brighton.

I am under no pretence that averaging 5.1 miles an hour for an entire day is going to be easy. Considering it’s the end of September and the daylight is rapidly fading, I haven’t exactly given us plenty of time. But I’ve done the maths, and if we stay on track, it should be just about doable.

Indeed, thanks to the sunrise equation – which takes into account longitude and latitude, altitude, and the time zone – it’s possible to calculate the exact moment the uppermost ray of the sun will poke its head above and below the astronomical horizon. Even if the weather is lousy and the sun is nowhere to be seen, you can be certain it’s there – meaning you can do this challenge any day of the year.

For instance, in Paris on 21 June, the longest day of the year, you’ll have 16 hours, 10 minutes and 52 seconds to complete your race against the sun. However, at the other end of the scale, the winter solstice will give you a mere 8 hours, 14 minutes and 48 seconds. On the plus side, you don’t have to get up quite so early.

There are three steps to racing the sun. First, choose a challenge. Second, determine how long you think you can do it in. Lastly, pick a date that gives you exactly the right amount of daylight hours to beat the sun.

With endless possibilities, deciding what to do is the hardest part of Race the Sun, but there’s a good chance you’ll either do a circular loop, an out and back route or a point to point. If you have the confidence and experience, you could decide to run up and down a mountain. Or around it, for that matter. Every year, the shoe giant ASICS hosts an event in Chamonix where two teams race each other in a relay around Mont Blanc in the hope of not only being the winners but indeed beating the sun.

The circular option – whether that be running/cycling around a lake, city or even around a mountain like Mont Blanc (though this is best done as a relay) – offers the greatest challenge. You might equally choose to complete a Peak to Peak (see here) or take on an epic Tri-it-Yourself triathlon (see here). Either way, a circular route gives a huge sense of achievement. Plus, there’s little room for shortcuts should the going get tough.

An out and back route – whether that be to a prominent high point, a town, or along a river – is, in my experience, the easiest to plan. There’s no need to worry about return transport and you’ve got lots of flexibility in terms of your start/finish point. Plus, if you have friends and family in support, it makes their life and yours much easier.

The third option, of a point to point, best lends itself to running a national trail, or cycling from one town to another (see Extreme Twinning) or indeed, as we were doing, running to the coast.

Deciding how long it will take you is a bit of trial and error. A top tip is to use an online mapping tool, like Strava or MapMyRun, which predicts how long it will take you. Or if you know the mileage, you could use a pace calculator based on what you think you can sustain for x number of hours.

The final stage is to simply pick a date that gives you sufficient amount of time to complete the challenge. Which, as it turns out, I manage to do. Eleven hours and forty minutes later, my friend and I stumble onto Brighton Pier feeling like intrepid warriors returning from battle. With three minutes to spare, we’ve done it. We’ve beaten the sun. All we have to do now, is have a well-earned drink and get home. ‘Anyone know where the train station is?’

YoYo Peaks

RUN/CYCLE UP/DOWN ALL OF THE POSSIBLE ROUTES OF A PEAK/COL IN ONE PUSH

RULES

RULES

1. There must be at least three or more ways to ascend the mountain, col or hill.

2. To make it accessible to everyone, it should be on public land.

3. It should be made in one attempt.

KIT (if cycling)

KIT (if cycling)

• Road bike

• GPS computer

• Windcheater/gilet

• Helmet

• Bike shoes

• Food and water

METHOD

METHOD

Nestled in the heart of the Provence region of southern France is an ominous-looking mountain that goes by various names. Some call it the Beast of Provence, others the Bald Mountain. Regardless of its nickname, Mont Ventoux, sitting at an elevation of 1,912 metres, is a thing of twisted beauty. It might be of little interest to a mountaineer, but to a cyclist it is Everest. And it’s on this legendary and topographical marvel of a mountain, featured in many a Tour de France, that hundreds of cyclists every year will attempt to qualify for membership of one of cycling’s most prestigious clubs: the Cinglés du Mont-Ventoux.

In order to become a member of this club (cinglés in French loosely translates as ‘crazies’), you need to ascend Ventoux from each of the three main roads to the summit, stamping your brevet-styled card as you go. Ironically, of the sixty nationalities who’ve successfully completed the challenge, the largest contingent come from one of the flattest countries in Europe – the Netherlands.

And it’s not just on Mont Ventoux that you can find this type of athletic endeavour. You could head to the Alps and attempt to become a Grand Master of the Fêlés du Grand Columbier or tackle Les Barons du Soulor in the French Pyrenees. But with thousands of cols and mountains to choose from, there’s nothing stopping you from creating your own version of this challenge.

Since the crucial element that binds YoYo Peaks together is the possibility of reaching the top by three or more means, your first step is to grab a 1:25,000 map and scour your local area for a suitable candidate. It doesn’t necessarily have to be a mountain – simply a prominent high point. It’s likely that some options will be better suited to running and others to cycling. It may even be that you do a combination of both, with a mountain biking option chucked in for good measure.

However, more often than not the best types of climbs are the iconic ones. Some, like La Pierre du Saint Martin in the Pays Basque, have seven routes up to the col, which lends itself to seeing how many you can complete in 24 hours. Or you simply select a minimum of three and see how it goes. Whichever option you go for, the idea is that it’s done in one push rather than spread out over a number of days. (For that type of challenge, see 7 in 7).

There also needs to be a definable start point for each route – a village, trailhead or prominent marker – something that indicates the beginning of the climb. But it could equally be a café, restaurant or even a supermarket, all good places to stock up on morale-boosting refreshments.

Like every Race-it-Yourself adventure in this book, a challenge of this nature is best completed with mates. Although there’s nothing wrong with doing it alone, and hats off if you do, a shared goal is so much more fun. All you need to do is pick a hill or col, set a date, gather some friends together to train with and then do it. Rest assured, it will bring a whole new dimension to what you consider ‘difficult’.

Tri-It-Yourself

CREATE YOUR OWN TRIATHLON

RULES

RULES

1. There should be at least three stages, although it can follow a duathlon format if the terrain suits it and there’s a lack of somewhere to swim.

2. The course should be publicly available and not be on private terrain.

3. If seasonal, information should be shared on when it’s possible to take on the event for others to follow.

KIT

KIT

• Bike

• Bike shoes

• Helmet

• Gilet

• Bottle

• Wetsuit

• Goggles

• Running shoes

• Food

• GPS

METHOD

METHOD

How often have you come across a genius, madcap race that involves traversing mountain ranges, jumping out of a car ferry and swimming across a freezing cold fjord or mountain biking across a desert and thought: How in the hell did they come up with that idea? Well, more often than not, it involved a few drinks and some idle chitchat around a bar.

Today, Ironman World Championships involve a rough 2.4-mile sea-swim, followed by a 112-mile windy bike leg (reduced from 115 miles) and then a marathon in the baking heat. When the concept was first discussed over some drinks at an awards ceremony in Hawaii back in 1977, it began as a dare. Unable to decide which was the toughest, they decided that the only way to see if it was possible to tackle the three iconic challenges on the island in one day was simply to give it a go. And so a date was set for 7 a.m., 18 February 1978. Only fifteen people took part in the inaugural self-supported test event. Almost forty years later, it’s one of the biggest events in the world and consequently sells out like hot cakes. But if you missed out on a slot or couldn’t afford the entry fee, there’s nothing stopping you creating your own triathlon.

Indeed, for you to do justice to this Tri-It-Yourself challenge, you’ve got to think outside of the box. With a map in hand, you need to look at the lay of the land and, with military cunning, see how you can combine geographical features with multi-sport challenges. Because if the Urban Tri (see here) is designed to be something you can fit into your working week, this challenge is definitely reserved for the weekend. And ideally, is one that requires training. Otherwise, any Tom, Dick and Harry could do it.

The first rule to this challenge is that anything goes. Think big. If necessary, apply a liberal sprinkling of alcohol to aid clarity of thought. By definition, a triathlon involves a swim, cycle and run, but there’s nothing to stop you from changing those activities to what suits either your skill set, or the environment. Or even adding a fourth leg and making it a quadrathlon.

Or maybe you can make a mashup of an XTerra triathlon (swim, mountain bike, trail run) with the ÖTILLÖ (a SwimRun between lakes or islands, see here). It’s subversive races like these and others – including the Norseman Xtreme Triathlon in Norway, an iron distance triathlon considered to be the toughest in the world, and the Inferno Triathlon in Switzerland, a punishing swim, road bike, mountain bike and trail run – that have inspired me to send off my application form. Most importantly, they’re less of a race and more of an adventure, where simply finishing is more important than how fast you do it.

You’ll have two choices – a linear A to B route, or a circular one that brings you back to your start point. In a linear route, clearly you’ll need to think about transition areas and therefore where you’re going to drop off your bike and pick up running kit. Both have their advantages, except that the former will certainly require some form of support crew and also allows for greater creativity. Could you cross a mountain range? Or perhaps, you could create a route that connects several islands? Almost anything is possible depending upon whether you’re supported or self-supported.

Having decided on a geographical area – whether that be near your home or further afield – the first step is to find somewhere to swim. For instance, do you have a lake, reservoir or perhaps the sea nearby? Perhaps there’s a body of water well known to open-water swimmers and one with bragging rights attached to it. Bingo – that’s the first stage sorted! Ideally, you want to transition from the swim to the bike, so that your cycle route starts where your swim ends.

It doesn’t need to be an Ironman distance. Instead, see if there is an epic, downhill mountain-bike route near you. Is it possible to ride up the hill via a double track and then, similar to an Enduro event, speed down the single track? Or maybe there are some super-tough cols that on their own would be enough of a challenge but, when sandwiched in between a swim and run, would be epic? It needs to sound bonkers for you to get excited and equally rope your friends in too.

All you now need to do then is find somewhere to run – certainly my favourite element of a triathlon and, equally, where you can have the most amount of fun. Rather than do the usual three to four laps on a road, why not instead go for a trail run around a peak or, for those with grit, up the peak and back?

If you’re going ‘self-supported’, you need to think about whether you can carry enough food and water for your needs. You could use a small running pack to carry supplies. Of course, this totally depends upon how far you plan to go and whether you managed to persuade your friends and family to get involved.

The final stage is to set a date. There’s no point in coming up with this epic plan and then letting it go by the wayside. If you tell people what you’re doing, you’ll feel more committed to it. And don’t forget, it’s so much more fun doing these events with others. There’s no better way to bond than training for and doing an adventure together.

Everesting

CLIMB THE SAME HILL REPEATEDLY UNTIL YOU REACH THE HEIGHT OF EVEREST

RULES

RULES

1. Rides can be of any length, on any hill, on any mountain, but it must be ridden in one attempt, on the same hill and on the same route.

2. You need to reach at least 8,848 metres.

3. Only full ascents count – i.e. you must ride the full length of the climb, not half of it.

KIT

KIT

• Bike

• Helmet

• Lights

• GPS

• Food and water

METHOD

METHOD

‘This is absolutely nuts!’ I say to myself, feeling almost giddy with fatigue as I unclip from my pedals. For the past hour and a half, I’ve been clinging to my handlebars as I’ve repeatedly cycled up and down the hill beside my home. Some of my neighbours, who’ve passed me several times, clearly think I’ve lost the plot. And despite the fact I’ve done twenty repetitions up and down this short but wretched hill, which averages a 13 per cent gradient, I’ve clocked up only 1,000 metres of elevation – not even halfway through what’s regarded as a warm-up! This Everesting malarky is clearly as tough as it claims to be.

The idea of climbing Mount Everest, the highest point on the planet, is a notion that has gripped the imagination of many an athlete, adventurer and armchair explorer. However, it’s widely accepted that unless you have deep pockets or wealthy sponsors, summiting the 8,848-metre peak will simply remain a pipe dream.

So one day in 2014, a group of hill riders in Australia, who go by the name of Hells 500, flipped the concept on its head. They decided to virtually cycle up Everest, repeatedly climbing the same hill until they’d reached the accumulated height of the highest peak in the world – all in one ride.

They weren’t the first to do this crazy challenge, either. That accolade goes to George Mallory, the grandson of the British explorer by the same name who tragically lost his life on Everest in 1924, several hundred metres short of the summit. Seventy years on and while looking for a way to prepare for his own upcoming expedition on Everest, he was told that Australia’s Mount Donna Buang was ‘a good place to train’. And so began the seeds of what is now one of cycling’s most talked-about challenges.

So where do you start? The beauty of this challenge is that you can Everest just about any hill you want. If you’re a sucker for punishment, you could choose the biggest, baddest, hors catégorie climb you can find. Or if you want something a little more gentle and you’re happy to grind it out, find a long but gradual ascent – and be prepared for a long day in the saddle. At the other end of the scale, if you’re time poor and like pushing the pain barrier, you could choose a short but very steep hill, like the one I slogged my way up outside my home. Regardless of the climb, if you want to be an Everest pioneer, the most important thing is you are the first.

‘Riders are limited only by their imagination,’ writes Andy Van Bergen, the founder of Hells 500 and everesting.cc, in his blog, ‘but it will always be a race to be first. Pick a climb. Try to be first. Everest that. Digitally chisel your name into that sucker forever.’

The first step is to visit everesting.cc and find out if your chosen climb has been Everested. If it hasn’t, then you’re in luck. If you’ve managed to find a particularly iconic local climb that hasn’t been claimed, then you might want to keep your cards close to your chest, lest someone else beats you to it.

As you can appreciate, logistics have a fairly huge hand in your decision process. If you live near a prominent hill, you’re perfectly positioned to rope in your family and friends to be your support crew. Or you can simply bundle everything you need into the back of your car and drive to the bottom of your chosen nemesis, and start from there. But don’t forget to familiarise yourself with the rules – of which there are plenty.

Now, if you’re thinking, ‘This sounds nails, I want to do it,’ then you should be aware of the three stages of fun. The first 4,000 metres are a bit of a warm-up. The middle 5,000–7,000 metres are where you start to question your sanity and wonder what on earth you’ve let yourself in for. And then you hit what’s affectionately called in mountaineering terms the ‘death zone’. This is the point at which your legs will be screaming at you to stop, to quit this madness. You’re probably also falling asleep. And, in between, your brain will be doing backflips as you try to calculate how much further you have to go. Be warned, Everesting is not easy.

And although there’s no way to make Everesting easier, you can always make it more difficult. For instance, you could Everest on a single or fixed speed, or take it up a notch and do it off-road on a mountain bike. You could try to set a record for the highest number of repetitions (at the time of writing, 836 by Jeff Morris) or the shortest accumulated distance in a single ride (currently 87 kilometres). The world is your oyster.

This is one challenge you can’t simply turn up for – you do need to train. But once you’re ready, set a date and get out there and ‘digitally chisel’ your name into the Hall of Fame. Then no one will be able to take that away from you.