The Strategic Implications of Female Fighters

As I discuss in chapter 1, the leaders of most rebellions are reluctant to recruit women into the armed wing of the organization, and they are especially resistant to deploying them in combat roles. Even in the face of mounting resource demands, leaders’ own gender biases as well as the fear of backlash from key constituencies dissuades many rebel groups from sending women into battle. Yet, some leaders eventually create opportunities for women to participate alongside men in the group’s fighting forces, occasionally resulting in the large-scale recruitment, training, and deployment of female combatants on the front lines. For many of these groups, this decision represents a strategic response to acute resource constraints and reflects the leadership’s ex ante beliefs about the effects of this recruitment strategy on the group’s ability to mobilize essential human resources. Despite the centrality of this expectation in explaining the prevalence of female combatants, the strategic consequences of the decision to mobilize women for war are largely unknown.1

The dearth of research on this topic leaves open a number of important questions related to the impact of female combatants on the rebellions in which they participate. Most obviously, does extending recruitment opportunities to women succeed in alleviating the resource pressures that prompted the decision in the first place? Moreover, the recognition that female fighters typically represent a striking deviation from historical norms generates additional questions about the implications of their recruitment. For instance, how do local constituencies and external observers respond to the presence of female combatants? In what ways might the presence of female combatants shape the subsequent tactics and strategies the group employs? In order to probe these questions, in this chapter I therefore shift my focus from explaining the leadership’s motivations for recruiting female combatants to understanding the strategic implications of this decision.

While the potential implications of women’s recruitment are numerous, they have received minimal attention. I therefore initiate an exploration of this broad topic by investigating the manner in which female fighters influence rebel resource mobilization. I make two main arguments in this chapter. Consistent with the argument made in the previous chapter, I contend that the decision to utilize female fighters increases a group’s overall mobilization capacity. In short, rebel groups that recruit female combatants maintain larger combat forces than those that do not. This occurs both because expanding recruitment opportunities to women increases the overall number of potentially viable recruits and because female fighters themselves often serve as important recruitment devices for rebel movements. Additionally, I argue that the presence of female combatants often assists rebel organizations in securing support from external actors. Drawing on previous studies of gender framing in the media and the strategic manipulation of gender narratives by political movements, I argue that the visible presence of female fighters draws international attention to the group’s cause and positively influences external audiences’ attitudes toward the group. These effects have downstream implications for the group’s ability to secure resources from external nonstate actors such as diaspora communities and transnational activist networks. Ultimately, I argue that recruiting female fighters and highlighting women’s participation in rebel propaganda and recruitment campaigns play important roles in rebel efforts to acquire the resources necessary to achieve their political and military goals.

Resource Mobilization, Support, and Rebel Success

Rebel groups seek to maximize their resource mobilization potential because the odds of achieving their military and political goals are heavily determined by their ability to do so. While a wide variety of observable and unobservable factors determine the ultimate outcome of a civil war, a number of previous studies link the balance of material capabilities between actors to a given group’s probability of success (e.g., Clayton 2013; Cunningham, Gleditsch, and Salehyan 2009; Mason and Fett 1996).2 Overall, a rebel group that minimizes the imbalance of capabilities between itself and the government, which generally reflects successful resource mobilization, is more likely to achieve at least a portion of its goals. The aggregate capabilities of an armed actor represent a combination of both military and nonmilitary resources. The former includes war materiel such as troops, small arms, artillery, and munitions while the latter includes financial resources, food and medical supplies, access to bases beyond the government’s control, and the support and loyalty of the population. Because the survival and ultimate success of the movement is largely a function of its ability to mobilize these resources, efforts to acquire them represent a crucial proximate objective for rebel leaders.

The resources necessary to sustain the rebellion and whose acquisition shapes its outcomes originate from both domestic and international sources. As discussed in chapter 1, recruitment is a central occupation of rebel leaders. In order to survive and succeed, rebel movements require continuous inputs of material and human resources, which are most often obtained from the local population (e.g., Gates 2002; Leites and Wolfe 1970, 32–34; Weinstein 2007). Beyond serving as a vital source of recruits, local communities provide many essential nonmilitary resources to rebel groups, including food, clothing, camouflage, and intelligence. Indeed, loyal support from a base community is often essential to an armed resistance movement’s ultimate success (e.g., Wickham-Crowley 1992; Wood 2003).

As a supplement (or a substitute) to domestically acquired resources, rebel movements often look to external actors to provide critical resources. Foreign governments represent the primary external source of military resources for rebel groups (Byman et al. 2001; Salehyan 2009; Sawyer, Cunningham, and Reed 2017). The provision of strategic assets by foreign states, which range from direct military intervention on the group’s behalf to military arms and munitions, training, and access to bases on the sponsor’s territory, often exerts a substantial influence on the trajectory and eventual outcome of a conflict. On average, groups that succeed in securing external support survive longer and are more likely to achieve their objectives (Balch-Lindsay, Enterline, and Joyce 2009; Gent 2008; Salehyan 2009). Yet, sovereign states are not the only sources of external support for armed resistance movements: transnational nonstate actors and international organizations routinely provide nonmilitary resources (and occasionally military resources) to armed resistance movements or their political wings. The effect of support from nonstate actors on conflict duration has received surprisingly limited attention. However, existing studies have often highlighted the benefits that rebel movements receive from transnational activist networks, diaspora communities, and international organizations (e.g., Adamson 2013; Bob 2005; Collier and Hoeffler 2004; Jo 2015).

I argue that, while it is largely overlooked in the existing literature, female combatants can play an important role in rebel efforts to mobilize critical resources. As such, recruiting female combatants can potentially deliver important strategic benefits to rebel movements. The argument presented in chapter 1 suggests that rebels recruit female fighters primarily because they believe doing so will help them fulfill domestic recruitment demands. The relaxation of acute resource constraints reflects the first—and most direct—strategic benefit the recruitment of female combatants provides to the rebel movements. Opening recruitment to women expands the pool of potential recruits, thereby increasing the total number of troops a rebel group can send into battle against the state. A second set of benefits derives from the manner in which the presence of female fighters in the ranks shapes observer attitudes and beliefs about the armed groups for which they fight. Specifically, the presence of female combatants—and particularly rebels’ efforts to showcase and broadcast their support and sacrifice—directs international attention to conflict, legitimizes the group’s goals, and garners support for the movement. These effects ultimately translate into strategic benefits by increasing the likelihood that the group can secure and maintain the support of nonstate external actors.

The first set of benefits is largely self-evident and directly flows from the initial strategic logic that led to women’s recruitment. That is, recruiting women ameliorates resource demands. The effect of female combatants on the mobilization of additional resources requires a more nuanced explanation. To understand why female combatants exert a positive influence on external observers’ willingness to support an armed movement, it is first necessary to discuss the importance of gendered beliefs about war and the use of gender narratives during wartime.

War and Gender Stereotypes Revisited

Hostility and violence are commonly viewed as predominantly male traits and associated with masculinity. By contrast, empathy, compassion, and vulnerability are more likely to be associated with women and femininity (see, e.g., Sjoberg 2010; Williams and Best 1990; Wood and Eagly 2002). Experimental evidence underscores the implicit association of men with threat, violence, and aggression (Rudman and Goodwin 2004).3 Overt and implicit gender stereotyping of this kind serves to maintain and reinforce gender-based divisions of labor in society (Wood and Eagly 2002),4 and the highly skewed gender distribution of direct participation in warfare is perhaps the most conspicuous and universal reflection of this pattern. In most societies, and throughout most of recorded history, combat has been viewed as an overtly masculine enterprise from which women have largely been excluded (J. Goldstein 2001). The historical record as well as implicit gender-based associations create the expectation that combatants are ubiquitously male, while women, to the extent they are present in conflict zones, are commonly assumed to be innocent victims of (male) violence (Carpenter 2005; Enloe 1999; J. Goldstein 2001, 304–305).5

An intriguing aspect of this discussion is that war can exert seemingly contrary affects on gender norms. On the one hand, war appears to reinforce traditional gender norms, pressuring men to assume combat roles and casting women as innocent victims. Yet, as Elisabeth Jean Wood (2008) observes, violent internal conflicts often fundamentally transform prewar social institutions, norms, and practices, including the roles of women in society. The social and economic disruptions caused by armed conflict can therefore create new opportunities for women to challenge traditional social norms, including through their direct and indirect participation in armed conflict (e.g., Kampwirth 2004; Mason 1992; Parkinson 2013). Moreover, as discussed in chapter 1, women’s roles within armed groups tend to evolve and change over the course of the conflict. Contingent on group ideology and the strength of the beliefs held by relevant constituencies, women become more likely to participate in organized violence as the conflict endures, the intensity of the conflict escalates, and the resource constraints imposed on the rebels intensify.

Women’s participation in organized violence may reflect a weakening of gender norms and muting of gender biases, particularly among rebel leaders.6 However, it does not imply the wholesale rejection of such attitudes by the population of the conflict state or by external observers to the conflict. Gender norms that associate men with violence/aggression and women with peace/innocence are both widespread and deeply embedded. Thus, even where women take up arms on behalf of an armed group, these beliefs are likely to endure and continue to influence audience attitudes. The persistence of these beliefs also influences observers’ expectations regarding the factors that motivate men and women to engage in violence. Men are assumed to embrace violence as a means of fulfilling their obligations to the state, achieving prestige, advancing ideological goals, or ensuring access to resources. Women, by contrast, are typically viewed as disinclined to resort to violence except under truly exceptional circumstances, such as protecting themselves or their children from mortal threats or unprovoked abuse. Indeed, the analogy of the lioness fighting to protect her cubs is commonly used to describe and justify women’s engagement in violence (see Bayard de Volo 2001, 40–41).

This (assumed) distinction in motives for violence is critical to understanding both the ways in which women’s participation in armed conflict is justified and how observers inside and outside of the conflict state perceive of this participation. Violence perpetrated by women is often construed as natural but uncommon and borne of sacrifice rather than duty or material pursuits (Cunningham 2009, 565). Appealing to the same underlying sociocultural structures that typically preclude women’s participation in violence can therefore legitimize it during periods of large-scale conflict. Moreover, the perception that women’s participation in organized violence represents self-sacrifice, and thus reflects truly dire circumstances, signals important information about the causes and the organizations for which they fight. Where women gain entry to the overtly masculinized world of organized political violence, their presence has two notable effects. First, it becomes noteworthy for its deviation from observer expectations and thus captures their attention. Second, it potentially influences observer beliefs about the nature of the conflict and women’s motives for participation. As I discuss in more detail below, these gendered effects are apparent in media coverage of armed groups. Moreover, armed groups that utilize female combatants often exploit them for strategic gains.

Novelty and Framing in Media Coverage of Female Combatants

For many rebel movements, publicity is the key to survival and success. Often materially weak and operating in obscure or remote geographic locations, rebel groups derive substantial benefits from media coverage that draws international attention to the conflict (Bob 2005). Highlighting the presence of women in the movement represents one strategy through which rebel groups can enhance media coverage of their political struggle. Owing to the dynamics discussed above, the juxtaposition of images created by the presence of female combatants and their perceived contradiction to embedded assumptions about the nature of war promotes public interest and increases the salience of the conflict to external observers. Moreover, media coverage of female fighters differs in important ways from other reports of the conflict. Such coverage tends to humanize these women and rationalize their participation, thus framing them in a more sympathetic light. Both of these factors advantage rebel movements in their appeals to external actors and their efforts to portray themselves as legitimate political actors.

The perception of novelty surrounding female combatants is in apparent media coverage of both contemporary and historical conflicts. For instance, despite the general absence of women from GAM’s fighting force, a 2002 article in the New York Times Magazine drew international attention to the group’s “Widow’s Battalion” (Marshall 2002) and to its separatist conflict in Aceh, Indonesia, more generally (Barter 2014, 70).7 Similarly, during the Spanish Civil War national newspapers viewed the presence of female fighters in the Republican forces as a novelty, leading many outlets to publish photos of armed female fighters at rates that vastly outpaced their actual participation in the conflict (Lines 2012, 157–164).8 More recently, the attention given to women’s participation in the PKK and its allied Kurdish militias in Turkey, Syria, and Iraq (BBC 2014c; Robson 2014; Tavakolian 2015) and FARC forces in Colombia (Casey 2016; Miroff 2016; Tovar 2015) exceeds their actual prevalence within the ranks.9

The disproportionate attention journalists devote to female fighters may reflect their own attraction to the novelty of female fighters. Indeed, some scholars and non-Western journalists have recently criticized the Western press for its apparent fascination with “badass” women fighting in armed resistance movements in traditional societies (Dirik 2014; K. Williams 2015). However, as profit-motivated corporations, media outlets tend to feature stories that they believe will be of interest to their readers or viewers (see, e.g., Gentzkow and Shapiro 2010). The density of news coverage that female fighters receive (especially in Syria) therefore implies that Western viewers—not just journalists—express some interest in these stories.

Observer curiosity and interest in female combatants is also evident in the tens of millions of viewers who have watched any of the hundreds of videos available on YouTube and similar video-hosting websites that are devoted explicitly to women’s participation in armed groups. For instance, a three-minute BBC (2014b) video report highlighting women’s roles in the PKK has been viewed more than 1.7 million times. Documentaries produced by RT (formerly Russia Today) (2015) and VICE News (2012) focusing on Kurdish female fighters in Syria and northern Iraq have been viewed more than 2.5 million and 1.3 million times, respectively.10 Dozens of other videos and news segments similarly documenting Kurdish women’s participation in combat have each been viewed hundreds of thousands of times.11 The conflict in Colombia has generally received less international media attention than the conflict between ISIS and the various Kurdish factions.12 However, a Guardian (2015) video report largely focused on women’s involvement in the FARC has received approximately a quarter of a million views on YouTube. Moreover, VICE recently produced a documentary entitled “Colombia: The Women of FARC,” which highlights the long-running roles that female combatants have played in conflict and the potential roles they might adopt in the ongoing peace process (VICELAND 2016). Such coverage in both traditional and new media outlets suggests that female fighters—especially images of “girls with guns”—are capable of garnering substantial attention from outside observers.

In addition to generating audience interest, female fighters also shape the ways in which the media characterizes the groups on whose behalf they fight. Coverage of female terrorists and rebel fighters often employs gender frames and relies on entrenched gender stereotypes to explain the unexpected participation of women in armed political movements (see, e.g., Nacos 2005; Stack-O’Connor 2007a). As Patricia Melzer (2009) observes, gendered assumptions about terrorism typically preclude women’s participation in it. While men are assumed to participate in political violence because of their ideological convictions or aspirations for power, the image of the female terrorist “warrants an explanation outside of political motives and/or personal power aspiration” (52). Thus, news coverage of women in political rebellions often intentionally highlights the exceptional and unexpected nature of their participation and looks to personal, emotional, or psychological factors to explain it. By focusing on female fighters, such coverage transmits important information about a group to relevant audiences.

Coverage of Kurdish female combatants in Syria illustrates how news reports intentionally or unintentionally cast the PKK and YPG in a more positive, sympathetic light. News stories and documentaries frequently characterize the female fighters in these groups as heroic and admirable individuals, risking their lives in a battle against a brutal adversary.13 Moreover, these stories often use the presence of female volunteers in the Kurdish forces as a way to implicitly or explicitly frame the Kurdish forces and their cause as just and legitimate and use reports of ISIL’s abuse and degradation of women to delegitimize that group. Mari Toivanen and Bahar Baser (2016) report that French media sources tended to highlight the emancipation and equality women achieved by fighting for the PKK and the YPG, while British sources tended to focus on the personal and emotional motives of the combatants, often framing them as victims who utilize the opportunities afforded by the Kurdish militias to redress their grievances and defend themselves from ISIL brutality.14 In a similar manner, Laura Sjoberg (2018) contends that by highlighting the exceptional nature of female fighters and the extraordinary circumstances that drove Kurdish women to take up arms, news reports have tended to legitimize the Kurdish forces.15

Similar framing effects appear in media coverage of other civil conflicts as well. Moran Yarchi’s (2014) analysis of the content of news articles published in American, British, and Indian newspapers about terrorist attacks in Palestine-Israel suggests that when the perpetrator was a woman, journalists were more likely to frame the events in ways that were more compatible with the Palestinian’s preferred narrative about the conflict. Specifically, news coverage of these events focused comparatively more attention on the conditions in Palestinian society and on the group’s motives for rebellion. Compared to stories about attacks committed by male terrorists, those involving female terrorists were more likely to provide detailed information about the perpetrator and to attempt to “contextualize and rationalize” her actions, thus humanizing her (681). Relatedly, a recent study of the depiction of (Arab and Jewish) female political criminals in the Israeli media found that journalists often employed stereotypical gender frames to explain women’s unexpected participation in political violence. However, in so doing, these stories frequently highlighted events in the women’s personal lives rather than their ideological convictions as motives for their participation in political violence (Lavie-Dinur, Karniel, and Azran 2015). Media reports of Chechen female suicide bombers have also tended to humanize the perpetrators and attempted to discern the motivations for their (unexpected) participation in the conflict (Card 2011). Journalists also appear to have adopted a more positive, sympathetic lens in their coverage of female LTTE combatants and suicide bombers (Stack-O’Connor 2007b, 48–49). The female guerrilla fighters of the Spanish Civil War likewise (initially) received positive coverage from the domestic and international press and were praised for their bravery, resolve, and generosity (Nash 1993, 275–276).16 Consequently, news stories often appear to draw attention to female combatants and to humanize their actions and frame them as sympathetic actors. Such coverage can therefore benefit rebel groups attempting to establish the legitimacy of their cause to domestic and foreign audiences.

At first glance, framing female combatants as victims appears counterintuitive because they are, by their actions and the nature of their role as combatants, perpetrators of violence. However, this frame is effective specifically because of the power of embedded gender norms and assumptions that women do not normally participate in political violence. Because women’s participation in combat is typically viewed as exceptional, their presence is often interpreted as a signal (or framed to suggest) that the conflict has become so dire that women are willing to transgress social norms or abandon traditional roles in order to defend themselves and their communities (Jacques and Taylor 2009; Sjoberg 2018; Viterna 2014, 199). Moreover, by providing women a forum in which to exercise political agency and defend themselves, the rebel groups for which they fight become the beneficiaries of this narrative of victimization, empowerment, and emancipation.

As this discussion suggests, there is evidence that media stories tend to frame women’s participation in political violence in different ways than men’s participation. Journalists often adopt highly gendered frames in covering or explaining women’s participation. Yet, by emphasizing the exceptional nature of female combatants, contextualizing the motives for their participation, and highlighting the agentic and emancipatory opportunities afforded to them by participating in armed groups, media reports can produce a more positive, sympathetic depiction of the armed group than might otherwise emerge in the absence of female fighters. In the next section I consider how rebel groups may benefit strategically from similar effects and how some rebel groups utilize the presence of female combatants to advance a specific strategic narrative.

Constructing a Strategic Narrative

Many rebel movements are acutely aware of the potential impact that the presence of female combatants can exert on audience attention and perceptions of the movement. As with the framing devices employed by journalists and media outlets, armed resistance movements have often highlighted the presence of female fighters within their ranks in order to draw attention to the group and the grievances of the population it claims to represent and to garner sympathy and support (see, e.g., Nacos 2005). The decision to stress women’s roles and participation often reflects one aspect of a broader effort by rebel leaders to construct a more positive, sympathetic narrative for their group and their cause. Particularly, rebel groups strive to cultivate a narrative in which they are sympathetic political actors with legitimate grievances and to counter the government’s claims that they are simply a band of thugs, terrorists, or bandits.17 This contest over legitimacy is central to rebel efforts to win support from both domestic and international audiences.

Striving for Legitimacy

Following recent literature in various social science disciplines, I understand legitimacy as “worthiness of support” (Lamb 2014, vi). When a population perceives that an actor and its goals or policies are legitimate, that population feels a moral obligation to support or emulate that actor. Establishing legitimacy is strategically (and practically) important to governments, political parties, activist networks, and social movements because it serves as the primary alternative to coercion as a means to ensure compliance (Horne et al., 2016; Zelditch 2001). In short, legitimacy induces support and participation, while illegitimacy fosters opposition and resistance (Lamb 2014).

These factors also help explain why rebel groups often strive to establish legitimacy in the eyes of key domestic and international constituencies. Compared to groups that suffer a legitimacy deficit, rebel groups that successfully convince these audiences of their legitimacy are in a superior position to secure resources and allies that can enhance their ability to achieve their primary political objectives. A key dilemma for rebels is that they often lack the historical or legal basis for legitimacy that governments and other established political actors enjoy. Rather, they must construct legitimacy from other sources, a process that often requires appealing to the beliefs and values of specific populations and undertaking efforts to “market” the movement to these audiences (see Bob 2005). Rebels adopt a variety of strategies and engage a range of actors in an attempt to foster a perception of legitimacy. These include appeals to ethnic traditions, participation in elections, securing representation in established political institutions, and gaining recognition by foreign states and international organizations (Jo 2015, 28–29; see also Huang 2016a). I expand the list of possible sources of rebel legitimacy by examining the manner in which gendered narratives and images can influence observers’ beliefs about the legitimacy of a rebellion.

As the discussion in the previous section demonstrates, male and female combatants appear to provoke different responses from the audiences that observe and interact with them. Observers often view female combatants in a more sympathetic light and tend to believe that they are motivated more by rational fears or legitimate grievances than by ideological fervor, material gains, or inherent preferences for violence. While rebel leaders are often initially unaware of this tendency, which would preclude it as a motive for their initial recruitment, the leaders of organizations that have already opted to include women in the ranks are likely to become increasingly aware of this perception over time. For example, rebel leaders are likely to observe the responses of local civilians and international audiences to the presence of female combatants and update their beliefs about the potential strategic benefits associated with their use.18 By explicitly highlighting women’s participation in the organization, rebel groups hope to exploit these sentiments. Furthermore, to the extent that female combatants assist the group in establishing legitimacy, they may also assist the group’s efforts to mobilize support from domestic and international constituencies.

Female Combatants and Rebel Propaganda

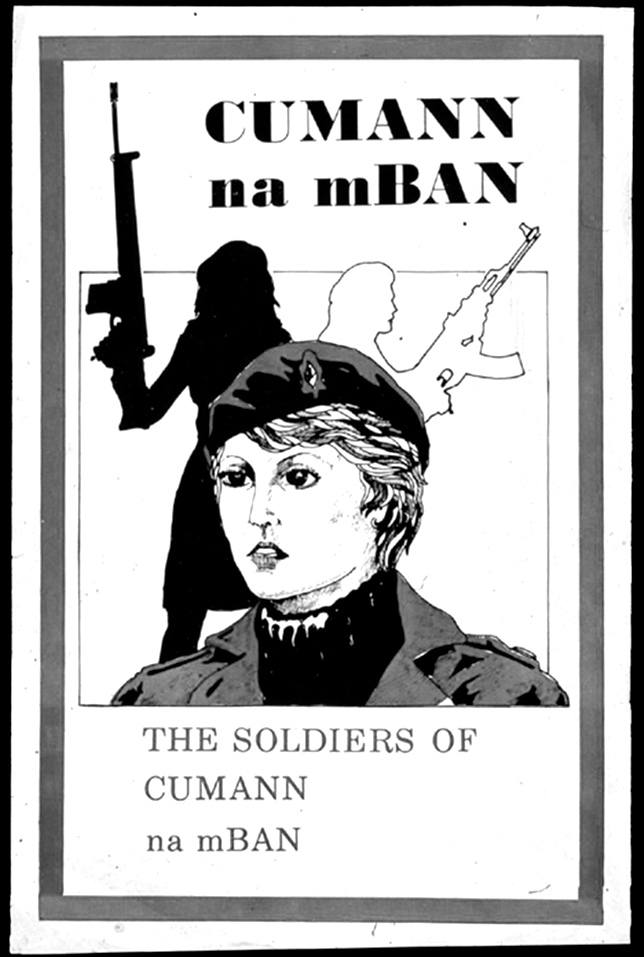

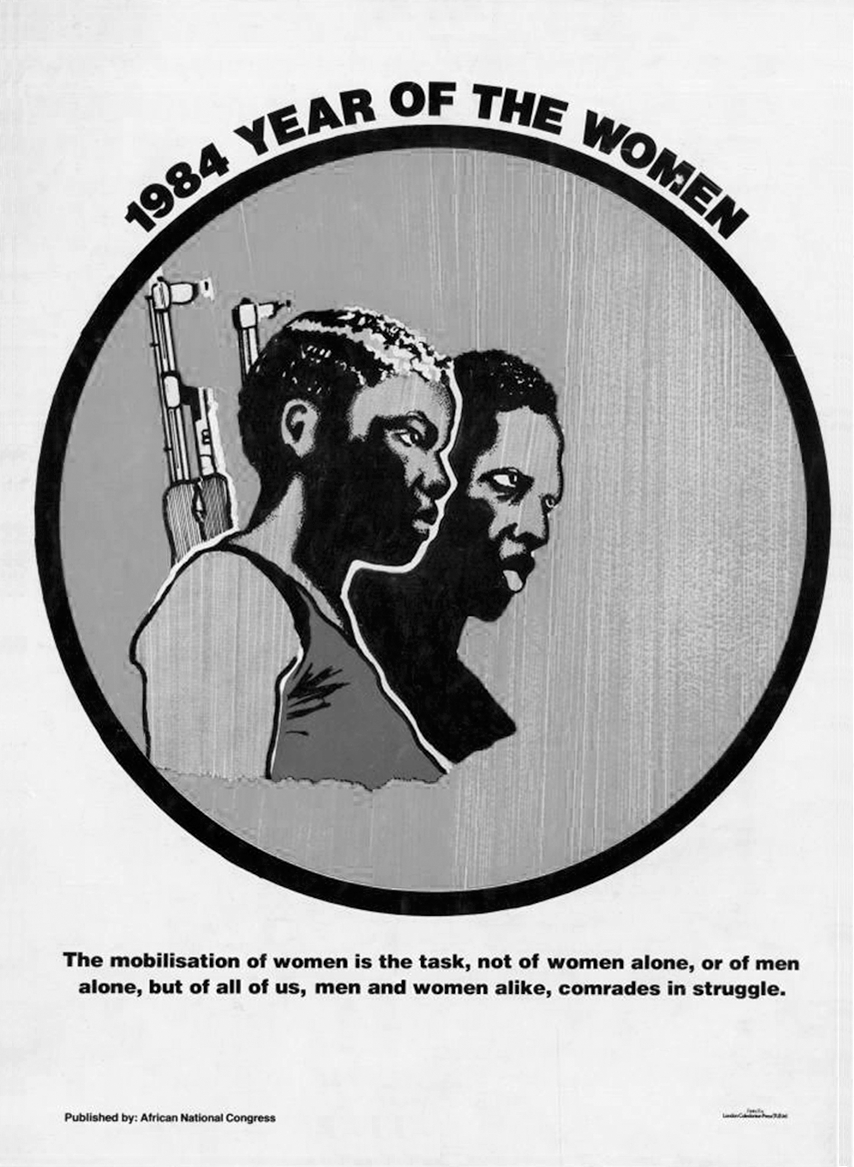

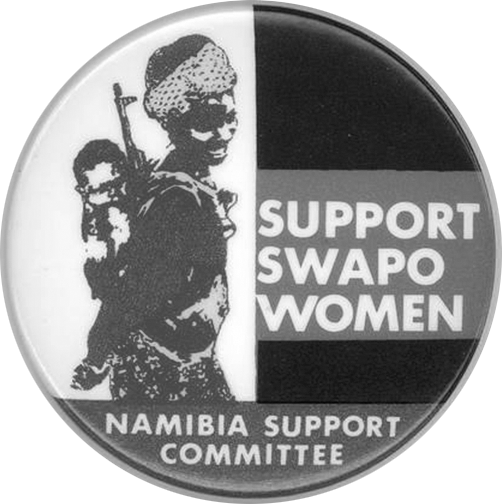

In an effort to construct a more appealing and sympathetic narrative, some rebel leaders choose to intentionally highlight women’s contributions and utilize images and descriptions of female combatants in their propaganda materials. Armed resistance movements in diverse regions of the globe have long recognized the powerful symbolism of women combatants and have intentionally incorporated these into their propaganda and outreach efforts (Loken 2018; O’Gorman 2011, 57; Stott 1990, 33; Weiss 1986, 147–148).19 Particularly during the 1960s and 1970s, the image of the young female guerrilla fighter holding a machine gun—often carrying a baby on her back or in her arms—became an prominent image in the propaganda materials distributed by armed resistance movements and the solidarity movements and other allies that organized on their behalf (Bayard de Volo 2001, 42–43; Enloe 1983, 166; Jones and Stein 2008). For instance, the image of the female MK guerrilla became a popular mass image of the strong liberated woman in sub-Saharan Africa (Cock 1991, 167; Geisler 2004, 51). During the Vietnam War, the NLF used photos of “determined young women bearing arms and dressed for battle” in the propaganda materials it distributed internationally (Taylor 1999, 72). They also frequently used images of female guerrillas and descriptions of their heroic activities in their domestic propaganda materials and internal publications (76). SWAPO’s propaganda publications likewise routinely included praise for its female combatants and photographs of female SWAPO fighters (Akawa 2014, 63).20 These publications, most of which were printed in English, were intended to disseminate the ideals and objectives of the movement and to solicit international support (Akawa 2014, 66–67).

The image of the armed militia woman likewise became an important symbol for the anti-Fascist forces during the Spanish Civil War and was frequently used on propaganda posters printed by leftist parties and anarchist trade unions (Nash 1995, 50–51). Particularly, Lina Odena, a young female volunteer killed early in the conflict, became a Republican war legend. Her death—by suicide in order to avoid capture (and likely torture)—was widely reported in the left-wing Spanish press, and her image appeared on posters and in other propaganda materials (Lines 2009, 171–172). During the civil war in El Salvador, the FMLN and its sympathizers copied and distributed autobiographical poems written by Jacinta Escudos, a young Salvadoran woman who had returned from Europe to fight for the FMLN. The El Salvador Solidarity Campaign in London later published these poems under the pseudonym “Rocio America” (Carter et al. 1989, 133). FARC has similarly utilized its female combatants in its public relations campaigns, including photo ops with international news media and direct interactions with the civilian population in the areas it controls (Herrera and Porch 2008, 614; see also Casey 2016; Miroff 2016; Tovar 2015). It also maintains a website that highlights the activities and contributions of its female members (BBC 2013).

Interestingly, these efforts often occur even where cultural norms strongly discourage women’s participation in armed conflict. As the previously discussed case of GAM’s political theater involving armed female supporters demonstrated, the international community rather than domestic constituencies represents the intended audience for many groups. For example, the Mujahadeen-e-Khalq (MEK) of Iran has emphasized the large numbers of female fighters within its ranks as part of a “charm offensive” aimed at legitimizing the group in the eyes of Western powers (Salopek 2003). While difficult to confirm, it seems this effort paid off, as the United States removed the MEK from its list of foreign terrorist groups in 2012. In addition, the websites of the various Kurdish factions active in Syria and Turkey, as well external organizations sympathetic to their causes, also explicitly highlight the prevalence of female fighters within the movements, draw attention to women’s commitment to the cause, and emphasize the groups’ support for women’s rights (see PKK 2019; YJA-Star 2019; YPG 2017). As these examples suggest, many rebel movements intentionally highlight—and sometimes exaggerate—women’s participation within the movement as an important aspect of their propaganda and marketing efforts.

The images featured here provide several examples of the ways in which rebel movements in various regions of the world have featured images of female combatants in their propaganda materials. Figures 2.1 through 2.4 were produced by or explicitly for a specific rebel movement.21 Others, however, were produced by the groups’ overseas activist networks or in cooperation with international activist organizations that supported the movements’ goals. Figures 2.5 though 2.9 provide examples of images produced by such allied organizations. For example, figure 2.5 represents an example of the materials produced by the UK-based Namibia Support Committee (NSC), which raised awareness of the Namibian liberation struggle, lobbied Western governments on its behalf, solicited donations for SWAPO’s political and humanitarian efforts, and transported supplies to the group’s refugee camps. Like many rebel organizations, SWAPO had offices around the world and often worked with local advocacy networks and political organizations in those countries to disseminate information and solicit support. Figure 2.6 represents an image that was replicated widely, both in Rhodesia by ZANU and in Europe and the United States by pro-ZANU activist movements. Figures 2.7 and 2.8 represent similar depictions of female combatants in the materials produced by solidarity organizations working on behalf of FRELIMO and the MPLA, respectively. For instance, the North American–based Liberation Support Movement (LSM) helped coordinate support for and lobbied on behalf of a number of national liberation movements (predominantly in sub-Saharan Africa) between 1968 and 1982. Figure 2.9 shows a poster produced by the Organization of Solidarity of the Peoples of Africa, Asia and Latin America (OSPAAAL) in support of FMLN guerrillas in El Salvador. This Cuban organization was founded in 1966 and was devoted to supporting (largely communist/socialist) liberation movements in the developing world. Finally, figure 2.10 shows a poster published in the early 1980s by the Berkeley-based publisher Inkworks Press for an FMLN office in San Francisco.22 These images not only highlight the presence of female combatants in the armed political movements on whose behalf they were produced but also illustrate the ways in which networks of these organizations’ overseas allies reproduced and transmitted these symbols to foreign audiences.

Figure 2.1 PFLP poster (Israel/Palestine) by Marc Rudin, 1980.

Source: Image courtesy of the Palestine Poster Project Archives

Figure 2.2 NLF poster (Vietnam) by unknown artist, c. 1960s.

Source: Image courtesy of Dogma Collection Online

Figure 2.3 PIRA poster (Northern Ireland) published by Cumann na mBan, 1978.

Source: Image courtesy of Linen Hall Library Archive & Republican Publications, Belfast, Northern Ireland, UK

Figure 2.4 ANC poster (South Africa) published by the African National Congress, 1984.

Source: Image courtesy of African Activist Archive

Figure 2.5 Pro-SWAPO button (Namibia/Southwest Africa) produced by the Namibia Support Committee, United Kingdom, 1980s.

Source: Image courtesy of African Activist Archive

Figure 2.6 Pro-ZANU poster (Zimbabwe/Rhodesia) published by the Print Shop, NY, 1970.

Source: Image courtesy of Lincoln Cushing/Docs Populi

Figure 2.7 Pro-FRELIMO button (Mozambique) produced by the Liberation Support Movement, United States, 1972.

Source: Image courtesy of the African Activist Archive

Figure 2.8 Pro-MPLA poster (Angola) published by the Liberation Support Movement, Canada, 1972.

Source: Image courtesy of Lincoln Cushing/Docs Populi

Figure 2.9 Pro-FMLN poster (El Salvador) by Rafael Enriquez and published by OSPAAAL, 1984.

Source: Image courtesy of Lincoln Cushing/Docs Populi

Figure 2.10 FMLN poster (El Salvador) published by Inkworks Press, CA, 1982.

Source: Image courtesy of Lincoln Cushing/Docs Populi

Gendered Imagery and Audience Attitudes

As the above discussion demonstrates, rebel movements have often incorporated images of women into their propaganda materials and highlighted the presence and participation of female fighters as part of their efforts to construct a more positive narrative. In order to accomplish this goal, rebels rely on the same entrenched gender norms and stereotypes as do the media (and other actors). They likewise apply similar combinations of gender frames in their efforts to strategically construct a narrative about women’s motives for participating. Women’s participation in warfare challenges assumptions about the nature of the conflict and leads observers to search for explanations rooted in the personal experiences that “drove” normally pacifistic women to take up arms. These explanations frequently focus on women’s experiences of victimization and/or their desire to defend their children or their families from violence. In both cases, the implication is that women only take up arms in exceptional circumstances and in support of righteous causes.

The image of the female guerrilla—often depicted as simultaneously occupying the role of mother and combatant—conveys conviction, sacrifice, and a desire to protect the weak and the vulnerable (see Bayard de Volo 2001, 41–43; Macdonald 1987). This portrayal is an explicit attempt to legitimize their participation and, by extension, to legitimize the groups for which they fight. As Lorraine Bayard de Volo (2001, 41) asserts, the maternal image is directly tied to legitimate acts of protection: “the desire to protect one’s children, even through the use of violence, was posed as a natural or divinely ordained maternal reaction [to threat].” MacDonald (1987, 14) similarly claims that the image of motherhood represents the “original protector/protected relationship.” Such depictions, which are prominent in the images provided above, reflect a strategic effort on the part of the armed resistance movement to frame itself as a just defender rather than an aggressor (i.e., terrorist). By manipulating deeply embedded gender norms about warfare and conflict, the visible presence of female fighters helps the group to mobilize support and sympathy and legitimate the organization and its goals in the eyes of foreign and domestic audiences.

Rebels also utilize the victimization frame to promote a narrative in which they both defend innocent and vulnerable members of the population (including women) and provide them with opportunities to defend themselves against a brutal and repressive state. For example, the LTTE successfully used the presence of female fighters to highlight abuses committed by both the government and Indian peacekeeping forces, which they argued drove women into their arms in the first place, and to showcase the group’s role in providing them protection and empowerment (Stack-O’Connor 2007b, 48). Jocelyn Viterna (2014) similarly argues that the FMLN intentionally drew attention to the high prevalence of female fighters within its ranks in order to construct a highly gendered narrative that portrayed the group as “righteous protectors” and defenders of the most vulnerable segments of society and to cast government forces as ruthless and unjust aggressors. Particularly, she asserts that the presence of female fighters helped the FMLN signal that the previous social order had been so thoroughly destroyed by state violence that women had no choice but to take up arms. During the Zimbabwean War of Liberation, women, including those who joined the movement, were portrayed as victims of the government’s brutal counterinsurgency campaign, which guerrillas argued was a primary motive for their participation (Lyons 2004, 124). For example, ZIPRA was able to point to a 1978 government attack on a (predominantly) female training camp to vilify Rhodesian forces for attacking “innocent women” and gain international sympathy for their cause (125–126), despite the fact that these women were combatants rather than civilians.

Highlighting the motives for women’s participation and employing the gender frames discussed above is intended to portray these fighters—and by extension the rebellions for which they fight—in a more sympathetic light. Ultimately, rebel groups and organizations allied with them utilize these images in an attempt to influence observer attitudes about the group and garner support for the movement and its goals from domestic and international audiences (see Bloom 2011; Nacos 2005; Sjoberg 2010). Viterna (2014, 199), for instance, asserts that the (perceived) innocence, vulnerability, warmth, and other traditional feminine characteristics displayed by young female FMLN fighters “tugged at the heartstrings of civilians” and increased their sympathy for the group’s cause. Anne Speckhard (2008, 1000) similarly argues that the “Black Widows” generated public interest and even sympathy for the Chechen rebel cause.23 FARC has likewise highlighted the presence of female fighters in the group during its public relations campaigns in an attempt to soften and humanize the image of the group (Herrera and Porch 2008, 614).

These frames can serve to justify both women’s participation in the conflict as well as help legitimize the group and its goals. Previous studies suggest that some rebel groups recruit female fighters as an explicit strategy of bolstering the legitimacy of the movement (Bouta, Ferks, and Bannon 2005, xx, 13; Dahal 2015, 188; Shekhawat 2015, 9). However, as noted earlier in the chapter, many groups only realize the benefits of female fighters after making the decision to include them. Regardless of the motives underlying their recruitment, the presence of female fighters may serve as a signal to outside observers of the depth of the community’s support for the movement and the group’s resolve to achieve its goals (Alison 2009, 125; Dahal 2015). Demonstrating the breadth of community support and signaling that the movement is composed of “average” peasants pushed into these actions by extraordinary (and often extraordinarily unjust) circumstances represents one way that rebel groups attempt to challenge regimes’ efforts to characterize them as being composed of radicals, extremists, and criminals.

While few studies have attempted to explicitly investigate the effects of female combatants on observer attitudes, some existing studies suggest that the gender composition of an organization can influence audience beliefs about its character and expected behaviors. Sabrina Karim (2017), for example, finds that increasing women’s participation in the domestic security forces improved citizens’ attitudes toward those forces. Specifically, citizens exposed to female officers expressed greater trust and confidence in the security forces and viewed them as more restrained and less likely to engage in abuse against citizens. One recent study similarly finds that among states emerging from protracted civil conflicts, national legislatures comprising greater numbers of female representatives are perceived to be less corrupt and more effective at delivering public services to their constituents (Shair-Rosenfield and Wood 2017). Analogous effects seem to exist in the corporate world as well. Specifically, gender diversity within firms’ boards of directors increases observer perceptions of corporate responsibility (Bear, Rahman, and Post 2010; Rao and Tilt 2016). These studies, across a variety of contexts, suggest that gender diversity within an organization can positively influence observers’ beliefs about its performance.

Gender also shapes observer perceptions of an individual’s trustworthiness and propensity for criminal behavior. For instance, prospective voters tend to believe that female political candidates are less corrupt than their male counterparts (Barnes and Beaulieu 2014). Numerous studies have also found that judges and juries view female defendants and perpetrators as less blameworthy of their (alleged) crimes, less threatening, and less disposed to recidivism than their male counterparts, resulting in comparatively lower odds of incarceration and more lenient sentences for women (Daly and Bordt 1995; Rodriquez, Curry, and Lee 2006; Spohn and Beichner 2000). Importantly, this effect appears to hold in the case of politically motivated violent crimes as well (Bradley-Engen, Damphousse, and Smith 2009). Consistent with these findings, Carrie Hamilton (2007, 108–109) asserts that in Spain female ETA members were more likely to receive lighter sentences and endure less harsh treatment after arrest than were male members—a factor that incentivized the group to recruit female operatives. As these studies suggest, while women often participate in criminal activities and political violence (though at lower rates than men in both cases), they are often judged less harshly and viewed more sympathetically than their male counterparts. Given that audiences appear to be more sympathetic to female perpetrators, female combatants may serve to improve the overall attitudes of audiences toward the group.

The discussion above suggests that the presence of female combatants and the use of their images in rebel propaganda materials is intended to generate support and sympathy for the movement and to encourage mobilization. Rebels use female combatants to convey information about the group to both domestic and international observers. This is accomplished by highlighting the exceptional conditions that led to their participation (and corresponding transgressions of gender norms), framing women as victims-cum-empowered agents, and using them as a signal of the depth of the group’s support in the community. Ultimately, these strategies are intended to help expand the movement and improve its ability to mobilize resources. In the next section I explain how these factors assist the group in achieving its political and military objectives.

Implications of Female Combatants

In chapter 1, I argued that attempts to address rising resource demands represent one of the principal motivations for rebel leaders to employ female combatants. By expanding the pool of potential recruits to include women, rebel leaders hope to increase the number of troops in their ranks, thereby increasing the odds that the movement survives and achieves its political goals. Above I discussed how female fighters sometimes become important symbols through which the movement attempts to shape the attitudes and actions of both domestic and foreign audiences. Specifically, the visible presence of female combatants serves to garner sympathy and support for the movement and its goals. This argument implies that rebel groups utilize female fighters in these ways because they expect that doing so will benefit them strategically. In this section I outline the specific channels through which these benefits accrue to rebels who utilize female fighters. I explicitly focus on the expected effect of female combatants on groups’ ability to recruit and retain troops and their ability to secure support from external actors, principally transnational advocacy networks and diaspora communities.

Recruitment and Resource Mobilization

The most direct manner in which the decision to utilize female combatants benefits rebel movements is by increasing the number of troops an armed group can commit to combat. Provided that a substantial number of willing female recruits exist, the decision to allow (previously excluded) women to perform combat duties should expand the group’s fighting force. Assuming that equal numbers of men and women are motivated to join the group and are capable of participating in combat, removing all restrictions on women’s access to combat roles could double the size of a rebel movement’s fighting forces. However, these assumptions are largely unrealistic, and both social and biological factors are likely to constrain the supply of female potential combatants.24 Nonetheless, in some conflicts, large numbers of women take advantage of the opportunity to fight when it presents itself. Women eventually constituted between 20 and 40 percent of the combat forces of groups such as the EPLF, FARC, LTTE, and RUF, representing thousands of combatants. For these groups and others that counted a high proportion of female combatants in their ranks, failing to include women would have resulted in a substantial loss of viable combatants, thus potentially jeopardizing the movement’s viability and diminishing the odds of it achieving its goals.25

In addition to their direct effect on the size of a group’s combat force, female combatants may also indirectly benefit the mobilization capacity of the rebel movements in which they fight. They accomplish this in two ways, first through their ability to encourage or shame reluctant men to take up arms, and second by demonstrating to other women that participating in the rebellion is possible. Previous studies have thoroughly documented women’s roles as successful recruiters for armed groups (e.g., Bloom 2011; Cragin and Daly 2009). Much of this literature focuses on the way in which women’s participation as combatants increases pressure on men to participate by implicitly suggesting that men who fail to join the movement are less courageous or less physically capable than the women who risk their lives for the cause (De Pauw 1998; J. Goldstein 2001, 65; Stack 2009). According to Viterna (2013, 78), the FMLN viewed female guerrillas as the most effective recruiters because young men “felt shamed when young women in uniform and carrying guns entered their communities.” The NLF also relied heavily on such recruitment strategies during the Vietnam War. As one young male recruit reported after encountering a group of female NLF guerrillas, “I am a man, and I could not be less than a woman. The pride of every man in our group was hurt. Consequently, all of us agreed to remain at the front” (Donnell 1967, 111). Gebru Tareke (2009, 91) recounts a very similar scenario in which female guerrillas of the Ethiopian TPLF encounter a group of young men and chide them into joining the rebellion by asking why the young men “are still at home with [their] mothers while the girls are fighting out in the fields.”

Female combatants were reportedly one of the most effective methods of mobilizing ZANLA recruits during the Zimbabwean War of Liberation because they challenged men’s feelings of masculinity and prodded them to participate (Weiss 1986, 80; Geisler 2004, 53). During the Guinea-Bissau Independence War, the Partido Africano da Independência da Guiné e Cabo Verde (PAIGC) similarly used female combatants as a recruitment tool: when female combatants visited a village, “all the men would join up so as not be shown up by the women” (Urdang 1984, 164). Likewise, Serbian media and Serbian nationalist groups highlighted the patriotism and sacrifices of female combatants as a way to motivate reluctant men to fight in the Yugoslav wars of the 1990s (Kesic 1999, 188–189). The presence of female fighters can also push men to fight harder or endure greater hardships (J. Goldstein 2001, 201). For example, female FARC guerrillas apparently set a standard for ferocity and courage that male fighters felt compelled to meet (Herrera and Porch 2008, 614).

The presence of female combatants may also positively influence the recruitment of other women. Particularly in societies in which traditional gender norms prevail, a group’s decision to deploy female combatants represents a tangible signal of women’s empowerment and the ability to participate alongside men as nominal co-equals rather than being strictly relegated to less prestigious noncombat roles. This signal, in turn, increases women’s willingness to actively seek out and take advantage of opportunities to participate in the rebellion when they are made available. Indeed, Cengiz Gunes (2012, 120) notes that for many young Kurdish women, encountering female PKK fighters “created a feeling of empowerment, which in turn created … a strong desire to join the PKK’s ranks.” Similarly, female guerrilla fighters played an important role in mobilizing the population in southern Africa rebellions because it was easier for female fighters to gain the support of other women (Geisler 2004, 53). During the Vietnam War, the NLF often used stories of heroic female guerrillas to inspire other Vietnamese women to participate in the conflict (Taylor 1999, 60–61, 78; Turner 1998, 37). The presence of female combatants (and leaders) in the FMLN early in the conflict in El Salvador challenged the stereotype that women were unfit for the rigors of guerrilla conflict and encouraged other women to join (Carter et al. 1989, 126), thus expanding the total number of recruits.

Finally, the visible presence of female fighters can encourage and strengthen support and loyalty toward the groups among local constituencies. The presence of female fighters helps accomplish this by enhancing the perceived legitimacy of the group’s goals, garnering sympathy from observers and demonstrating the group’s commitment to achieving its goals. Rebels that succeed in this endeavor are better able to secure the support of the domestic audiences that provide them with many of the resources essential to the rebellion’s survival (Heger and Jung 2015; Mampilly 2011, 53–58; Viterna 2013, 2014). Thus, in addition to providing critical human resources, the presence of female fighters may bolster a resistance movement’s ability to mobilize other forms of support from local constituencies, including the provision of food, shelter, and intelligence. Such support is often difficult to directly observe and quantify, but it should nonetheless serve to empower the rebellion and positively contribute to its resilience.

External Allies and Support Networks

As discussed at the beginning of this chapter, rebel groups often rely heavily on support from international organizations, foreign sponsors, and diaspora communities in addition to local constituencies. The ability to secure international support can have substantial implications for the group’s survival and the ultimate outcome of the conflict. Rebel groups therefore often devote substantial efforts toward developing and maintaining external support networks that may include diaspora communities, transnational NGOs, and foreign governments (e.g., Coggins 2015; Huang 2016a; Jo 2015).26 While strategic interests figure prominently in external actors’ (particularly states’) decisions about extending support to dissident movements abroad, movements that are better able to frame their goals as legitimate and their cause as just are more likely to successfully secure support (Coggins 2011). Propaganda serves a crucial role in rebel efforts to shape the beliefs and attitudes of external actors (Bob 2005; Jones and Mattiacci 2017).

As I have already discussed, images of female combatants figure prominently in the propaganda material of many rebel organizations, in large part because rebel groups that employ female combatants use such imagery as a way to signal important information about the movement. Principally, highlighting women’s presence in the ranks serves as a strategy through which rebel groups seek to convince external actors of the legitimacy of their goals, counter the government’s efforts to frame them as groups of violent extremists or thugs, and demonstrate the community’s deep commitment to their cause. To the extent that these efforts succeed, directing attention to female fighters’ presence in the movement and their contributions to the rebellion should enhance the group’s ability to garner support from foreign and transnational actors. As I elaborate below, rebels target this gendered political messaging to a range of external groups and organizations. However, diaspora communities and transnational activist networks are most likely to respond to such efforts.

DIASPORA COMMUNITIES

Diaspora communities represent a critical source of material and nonmaterial support for many rebel and terrorist groups (Adamson 2013; Byman et al. 2001; Huang 2016b, 66–67; 2016b, 97). Paul Collier and Anke Hoeffler (2004), for instance, have asserted that diaspora communities’ financial contributions to rebel groups at home represent one of the strongest predictors of civil war recurrence. The LTTE represents the most striking example of rebel group reliance on diaspora support, as the majority of its budget apparently came from remittances from the Tamil diaspora or from international investments (Byman et al. 2001). Other movements, including various Palestinian factions, the PKK in Turkey, PIRA in Ireland, and the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) in Rwanda also depended on funding from diaspora communities (see, e.g., Byman et al. 2001, 41–42; Huang 2016b, 59). While the funding streams provided by diaspora communities are arguably meager compared to the value of resources provided by external states, they nonetheless amount to millions of dollars provided annually to many rebel movements and are often essential to the movements’ survival.

Surprisingly little research systematically evaluates the factors explaining diaspora groups’ support for insurgencies. However, much of the existing research points to the ability of the rebel movement at home to construct a salient connection with co-nationals abroad, establish the group as the legitimate representative of the population for which they fight, and engender sympathy for the movement and its goals (see, e.g., Adamson 2013; Matsuoka and Sorenson 2001). Many of the previously discussed mechanisms through which female fighters are expected to shape the attitudes and behaviors of domestic audiences should also influence overseas constituencies. For instance, members of diaspora communities often feel a profound sense of guilt for not participating in the armed struggles in the their homelands and thus look for other ways to assist (Matsuoka and Sorenson 2001, 95–96). Most often these efforts take the form of financial support, but they also frequently include political mobilization, networking with international NGOs and those located in the country of residence, and activism to raise public awareness among the population of the adopted country. Political entrepreneurs within the diaspora community working on behalf of the rebel movement are acutely aware of these feelings and often adopt strategic frames intended to enhance feelings of guilt, responsibility, or obligation in order to promote support among the members of the diaspora (Adamson 2013; Wayland 2004). Thus, just as female combatants “tug at the heartstrings” of the peasants in conflict zones and shame reluctant men into joining the rebellion, images of armed young women risking their lives for a cause are likely to spur support among constituents residing overseas.

Anecdotal evidence suggests that some rebel groups have successfully exploited the presence of female fighters in the ranks to mobilize support among the diaspora. For instance, the EPLF and its allied mass organizations staged events in diaspora communities in Europe and North America to celebrate the contributions and sacrifices of the tegadelti (EPLF guerrillas) fighting in Ethiopia, including its female combatants. Moreover, the EPLF-allied National Union for Eritrean Women (NUEW), which helped promote the group’s women’s rights agenda, was one of the primary mass-based organizations mobilizing resources among the diaspora community.27 According to Atsuko Matsuoka and John Sorenson (2001, 122–123), many members of the Eritrean diaspora strived to emulate the sacrifices and self-reliance of the EPLF fighters. Most surprisingly, public awareness of the high proportion of female fighters in the EPLF reportedly exerted a positive influence on gender egalitarianism within the Eritrean diaspora, suggesting that this audience was not only aware of women’s participation but were also influenced by it. By some estimates, the EPLF’s highly organized network of support organizations was able to raise as much as $20 million per month from the global Eritrean diaspora (Clapham 1995, 88).

TRANSNATIONAL ACTIVIST NETWORKS

NGOs and solidarity movements represent another source of external support for rebel movements. These actors advocate on behalf of resistance movements—or their political wings—in foreign countries in order to raise public awareness for the group’s cause, solicit donations, and pressure the governments of those states to intervene in the conflict diplomatically or to withhold support from the incumbent regime (Bob 2005; Clapham 1995; Sapire 2009; Sellström 2002). While these organizations rarely provide military support, they nonetheless represent an important resource for many rebel movements and have the potential to influence the trajectory of the conflict.

Numerous examples highlight the connection between external activist networks and rebel movements. During the Salvadoran Civil War, the Committee in Solidarity with the People of El Salvador (CISPES) carried out protests against U.S. funding for the Salvadoran government, called attention to mass human rights abuses committed by the regime, and sought to build support and solidarity for the FMLN’s struggle.28 In a similar fashion, organizations such the Chicago Committee for the Liberation of Angola, Mozambique and Guinea-Bissau and the Southern African Liberation Committee organized campaigns to raise awareness of and provide political and material support for liberation movements in sub-Saharan Africa. They also encouraged boycotts of companies conducting businesses in apartheid states and lobbied the U.S. government to withhold support from the governments of South Africa, Rhodesia, and other colonial states. In Mozambique, FRELIMO likewise received substantial support from numerous international charities and NGOs, including the Joseph Rowntree Fund of London, the Lutheran World Federation, and the World Council of Churches (Schneidman 1978). Left-wing student groups and parties in Europe and North America also routinely organized on behalf of armed resistance movements in the Global South—particularly those fighting colonial regimes—to gather humanitarian goods (e.g., food, clothes, blankets, etc.), raise funds, and increase public awareness for the movements’ causes (e.g., Kaiser 2017; Kössler and Melber 2002, 109–111; Mazarire 2017; Sellström 2002). While the funding generated by these groups is often small in comparison to those provided to rebel movements by allied states, they nonetheless represent important inflows of much needed resources. Moreover, the lobbying and publicity efforts of such groups, which in some cases leads to diplomatic intervention by external states, is often at least as important as the tangible resources the solidarity networks can deliver.

While these groups were independent from the movements they supported, in many cases, the connections between transnational activist networks and the rebel movements they support are less clear-cut. The symbiotic relationships between anticolonial and anti-apartheid liberation movements and international solidarity efforts are well documented. NGOs in North America and Europe often desire to directly support liberation movements abroad and sometimes include political exiles from these organizations in their leadership (Sapire 2009; Saunders 2009). Numerous solidarity movements and NGOs have worked closely with rebel movements overseas, providing both direct assistance to the armed movement (or more commonly its political wing) and raising public awareness about the conflict. For instance, the NSC was an important source of overseas support for SWAPO and worked closely with members of the organization, even sharing a London office with the rebel organization until 1978 (Saunders 2009, 449). In addition, the Committee for Freedom in Mozambique, Angola and Guine (CFMAG), which was formed in the UK at the request of FRELIMO, worked with political parties, student groups, and churches to mobilize opposition to Portugal’s colonial governments and to provide aid to the resistance movements challenging them (Bishopsgate Institute 2018). In the 1970s, various black solidarity movements organized to support anticolonial movements (particularly against settler regimes) in Africa and to attempt to shape U.S. policy toward the region. In 1973 alone the African Liberation Support Committee raised tens of thousands of dollars to support armed resistance movements in Africa, including ZANU, UNITA, PAICG, and FRELIMO (Cedric Johnson 2003, 490–491).

Connections with international governmental and nongovernmental organizations through their political wings also helped many armed resistance movements secure substantial amounts of humanitarian assistance from both NGOs and international organizations. For instance, numerous NGOs cooperated directly with the TPLF and EPLF’s own relief agencies during Ethiopian Civil War. These agencies, which were connected to the rebel groups’ governance structure, played a critical role in providing not only resources to the rebels but also publicizing the rebel groups’ cause, legitimizing their struggle against the Derg regime, and assisting them in securing diplomatic contacts (Clapham 1995; Matsuoka and Sorenson 2001, 37). Similarly, SWAPO garnered substantial amounts of humanitarian aid from international solidarity organizations and multilateral agencies, much of which was intended for the refugee centers it managed in Namibia, Zimbabwe, and Angola (Akawa 2014, 77–78; Dobell 2000, 61–63).

The use of gender imagery in NGO campaigns is well documented (e.g., Carpenter 2005), and as the propaganda images above indicate, solidarity movements and NGOs allied with rebel movements frequently employ images of female combatants. For instance, SWAPO representatives and members of their overseas activist networks often highlighted women’s roles and participation in the movement, including their roles as combatants, as a way to generate international attention and support (Akawa 2014, 77–78). Audiences located thousands of miles away and with little interest in the politics of the conflict state are more likely to pay attention to images that appear novel or unexpected and more likely to respond to evocative images such as those that depict young mothers taking up arms to advance their cause. As discussed above, such images rely heavily on the gendered expectations of observers that women’s participation in combat is exceptional and must therefore signal the righteousness of the cause. Consequently, rebel groups that recruit female combatants and utilize their images in their propaganda materials are more likely to enjoy the support of substantial transnational solidarity efforts or foreign activism.

Summary and Testable Hypotheses

In this chapter, I have argued that female combatants strategically benefit the rebel groups that elect to recruit them by enhancing the group’s recruitment and mobilization capacity, ultimately allowing it to field a larger combat force than it otherwise could have mustered in their absence. I identified two avenues through which this occurs. First, and most directly, the decision to open combat roles to women expands the group’s potential supply of recruits. Even after accounting for the possibility that many women are not interested in fighting on the group’s behalf and that some will not have the requisite physical capabilities to do so, allowing women to serve in combat should allow the group to recruit, train, equip, and field a larger number of combatants. Second, I argued that the visible presence of female fighters serves as an important recruitment instrument. Specifically, the presence of armed females in a group is likely to shame reluctant men into joining the armed struggle. I also argued that the presence of female combatants serves to expand the number of women willing to participate in the organization by demonstrating to other women that fighting with the rebels is a realistic option. Regardless of the specific mechanisms at work, the arguments broadly suggest that the presence of female combatants should increase the number of troops a rebel group has under its command. This provides the first testable hypothesis of this chapter:

H5: Rebel groups with a higher prevalence of female fighters have larger combat forces than those with a lower prevalence of female combatants.

A second set of arguments put forth in this chapter focuses on the potential role female combatants play in assisting the group’s ability to mobilize international support. I highlighted the frequency with which rebel groups that include female combatants in their ranks utilize these women (or at least their images) in their propaganda materials and recruitment efforts. Rebels utilize female fighters and their symbolic value as part of their effort to construct a more positive image for the movement and counter the alternative, highly negative narrative (e.g., thug/terrorist) asserted by the government. In particular, the presence of female fighters in their ranks represents one strategy through which rebels attempt to signal the depth of community support for a movement, convey the legitimacy of its goals, and gain sympathy from external audiences. Establishing that observers in fact perceive female and male combatants differently and that the presence of female combatants enhances the perceived legitimacy of the groups that utilize them is central to demonstrating the validity of the arguments in this chapter. I therefore propose the following hypothesis:

H6: The presence of female fighters increases observer support for the group and its goals.

To the extent that female fighters successfully influence external audience perceptions of the movements that employ them, they may also increase the group’s ability to garner resources from these audiences. While strategic interests typically dominate state decisions regarding support for foreign rebel groups and armed resistance movements, transnational actors are more likely to be swayed by impressions of a group’s legitimacy or feelings of sympathy for its cause. By positively influencing external actors’ beliefs about the legitimacy of the group and increasing their sympathy for its cause, female fighters improve the odds that the group receives financial or material support from diaspora communities, transnational advocacy networks, or other transnational constituencies. I therefore hypothesize:

H7: Rebel groups that include female combatants are more likely to receive support from external nonstate actors compared to groups that exclude female combatants.

In this chapter, I have presented a set of arguments regarding the potential strategic benefits associated with the decision to recruit female combatants. These arguments encompass both the direct benefits that come with relaxing constraints on the supply of recruits (which I argued in chapter 1 was a primary motivation for the decision to accept women into the ranks); the more indirect recruitment benefits that stem from the presence of female combatants, such as shaming reluctant men into participation; and the benefits associated with the manner in which the presence of female combatants assist the group in establishing legitimacy and garnering sympathy from relevant domestic and international constituencies. Ultimately, I argue, these dynamics benefit the group by allowing it to field a greater number of troops and helping it to secure the support of transnational actors. I empirically evaluate the veracity these arguments and the hypotheses drawn from them in the following chapters.