In the beginning of this book and of every other, the listeners are accustomed to ask who is the efficient cause. And it is very useful to know this, for statements of ‘authentic’ men are the more diligently and firmly inscribed in the mind of the hearer.1

The English grammarian William Wheteley (fl. 1309–16) is addressing his pupils in the introduction to his course of lectures on the De disciplina scolarium. It is very useful, he assures them, to know the name of the ‘efficient cause’ or writer of a book, because ‘authentic’ statements—statements which can be attributed to a named authority—are more worthy of diligent attention and to be committed to memory2. Wheteley explains that the De disciplina scolarium was written by Boethius, the Roman consul who died in 524. In fact, it was written between 1230 and 1240, probably at Paris3.

This mistaken attribution of a ‘modern’ work to an ‘ancient’ and distinguished writer is symptomatic of medieval veneration of the past in general. Old books were the sources of new learning, as Chaucer remarks:

. . . out of olde feldes, as men seyth,

Cometh al this newe corn from yer to yere,

And out of olde bokes, in good feyth,

Cometh al this newe science that men lere4.

To be old was to be good; the best writers were the more ancient. The converse often seems to have been true: if a work was good, its medieval readers were disposed to think that it was old. In order to understand such attitudes better, it will be necessary in the first place to examine the significance of the common technical term for a distinguished writer, namely, auctor, and then to proceed with an investigation of how the auctores were studied within the medieval educational system.

In a literary context, the term auctor denoted someone who was at once a writer and an authority, someone not merely to be read but also to be respected and believed5. According to medieval grammarians, the term derived its meaning from four main sources: auctor was supposed to be related to the Latin verbs agere ‘to act or perform’, augere ‘to grow’ and auieo ‘to tie’, and to the Greek noun autentim ‘authority’6. An auctor ‘performed’ the act of writing. He brought something into being, caused it to ‘grow’. In the more specialised sense related to auieo, poets like Virgil and Lucan were auctores in that they had ‘tied’ together their verses with feet and metres7. To the ideas of achievement and growth was easily assimilated the idea of authenticity or ‘authoritativeness’8.

The writings of an auctor contained, or possessed, auctoritas in the abstract sense of the term, with its strong connotations of veracity and sagacity. In the specific sense, an auctoritas was a quotation or an extract from the work of an auctor9. Writing around 1200, Hugutio of Pisa defined an auctoritas as a sententia digna imitatione, a profound saying worthy of imitation or implementation10. In his Catholicon (finished 1286), the Dominican Giovanni de’Balbi of Genoa amplified this with the statement that an auctoritas is also worthy of belief: as Aristotle says, an auctoritas is a judgment of the wise man in his chosen discipline11. De’Balbi used an auctoritas of Plato’s as an example. Plato says that the heavens are in motion; therefore, we should accept that this is indeed the case, because the man who is proficient and expert in his science must be believed12.

The term auctor may profitably be regarded as an accolade bestowed upon a popular writer by those later scholars and writers who used extracts from his works as sententious statements or auctoritates, gave lectures on his works in the form of textual commentaries, or employed them as literary models13. Two criteria for the award of this accolade were tacitly applied: ‘intrinsic worth’ and ‘authenticity’.

To have ‘intrinsic worth’, a literary work had to conform, in one way or another, with Christian truth; an auctor had to say the right things. The Bible was the authoritative book par excellence. At the other end of the scale came the fables of the poets, employed in the teaching of grammar14. As fictional narrative, fable could be dismissed by its critics as lying; many medieval writers expressed their distrust of such fabrication. According to Conrad of Hirsau (c. 1070–c. 1150), fables have practically no spiritual significance; they are as nothing when compared with Scripture15. Peter Comestor (Chancellor of Notre Dame, Paris, between 1168 and 1178) remarked that the figments of the poets are like the croaking of frogs16. The usual defence was that fables, rightly understood, provided philosophical and ethical doctrine: after all, Priscian had said that fable teaches and delights, and had commended the fables of Aesop17. Twelfth-century grammarians rendered acceptable the licentious stories of Ovid by extensive moralisation18. Those thinkers influenced by Neoplatonism—notably William of Conches (c. 1080–c. 1154) and Bernard Silvester (fl. 1156)—went much further, in their elaborate mythic interpretations of pagan fables19.

To be ‘authentic’, a saying or a piece of writing had to be the genuine production of a named auctor20. Works of unknown or uncertain authorship were regarded as ‘apocryphal’ and believed to possess an auctoritas far inferior to that of works which circulated under the names of auctores21. The standards of authenticity were applied most rigorously in the case of the books of the Bible22. Thus, the Dominican Hugh of St Cher (who lectured on the Bible 1230–5) was careful in explaining the terms on which certain apocryphal works are accepted by the Church:

They are called apocryphal because the author is unknown. But because there is no doubt of their truth they are accepted by the Church, for the teaching of mores rather than for the defence of the faith. However, if neither the author nor the truth were known, they could not be accepted, like the book on the infancy of the Saviour and the assumption of the Blessed Virgin.23

It was regarded as a very drastic step to dispute an attribution and deprive a work of its auctor. Much more common was the tendency to accept improbable attributions of currently popular works to older and respected writers. Interesting cases in point include the De disciplina scolarium, discussed above, and the Dissuasio Valerii ad Rufinum produced by Walter Map in the late twelfth century24. The quality and popularity of Map’s discourse caused some of his contemporaries to doubt that he could have written it. ‘My only fault is that I am alive’, complained Map; ‘I have no intention, however, of correcting this fault by my death’25. His title, he explained, contains the names of dead men because this gives pleasure and, more importantly, because if he had not done so the work would have been rejected. Map speculated concerning the fate of the Dissuasio after his death:

I know what will happen after I am gone. When I shall be decaying, then, for the first time, it shall be salted; and every defect in it will be remedied by my decease, and in the most remote future its antiquity will cause the authorship to be credited to me, because, then as now, old copper will be preferred to new gold. . . . In every century its own present has been unpopular, and each age from the beginning has preferred the past to itself . . .

In the long term, Map was right (witness the enthusiasm of recent literary critics for his works) but, in the later Middle Ages, the Dissuasio was attributed to the first-century Roman historian, Valerius Maximus. The ‘authenticity’ and auctoritas of the work in this attribution were defended in several medieval commentaries26.

The thinking we are investigating seems to be circular: the work of an auctor was a book worth reading; a book worth reading had to be the work of an auctor. No ‘modern’ writer could decently be called an auctor in a period in which men saw themselves as dwarfs standing on the shoulders of giants, i.e. the ‘ancients’27. In the treatise on the love of books which he composed in the last years of his life, Richard of Bury (Bishop of Durham 1333–45) could claim that, while the novelties of modem writers were always welcome to him, yet he always desired ‘with more undoubting avidity’ to explore the well-tested labours of the ‘ancients’28. The precise reason for the ancients’ excellence is unclear, according to de Bury: they may have had by nature greater mental powers, or they may have applied themselves more diligently to study. But in his opinion it is obvious that the ‘moderns’ are barely capable of discussing ancient discoveries, and of acquiring laboriously as pupils those things which the old masters provided29. Since the men of bygone days were of a more excellent degree of bodily development than the present age can produce, de Bury continued, it is plausible to suppose that they were distinguished by brighter mental faculties as well, seeing that in their works they are inimitable by posterity30. From all this, it would seem that the only good auctor was a dead one. Hence the ‘fault’ which Walter Map was in no hurry to correct.

Every discipline, every area of study, had its auctores. In grammar, there were Priscian and Donatus together with the ancient poets; in rhetoric, Cicero; in dialectic, Aristotle, Porphyry and Boethius; in arithmetic, Boethius and Martianus Capella; in astronomy, Hyginus and Ptolemy; in medicine, Galen and Constantine the African; in Canon Law, Gratian; in theology, the Bible and, subsequently, Peter Lombard’s Sentences as well31. The study of authoritative texts in the classroom formed the basis of the medieval educational system.

This system had its origins in late antiquity. From the Roman grammarian (grammaticus) of the fifth century, the pupil learned the science of speaking with style (scientia recte loquendi) and heard the classical poets being explicated (enarratio poetarum)32. The first of these activities comprised explanation of the elements of language, letters, syllables and words; the second comprised explanation of the intellectual content of a text. In his prelectio (i.e. lecture or explanatory reading), the grammarian would describe in minute detail the verse-rhythms, difficult or rare words, grammatical and syntactical features, and figures of speech, included in a given passage. He would also elaborate on its historical, legal, geographical, mythological and scientific allusions and details. Pupils were thereby enabled to understand fully each passage of the work.

These teaching methods continued, with occasional modification, into the Middle Ages33. John of Salisbury’s Metalogicon (completed 1159) provides a useful point of reference, since it refers to both past and present educational practice. After paraphrasing the account of prelectio which Quintilian had written in the first century, John proceeds to relate how Bernard of Chartres (†c. 1130), ‘the greatest font of literary learning in Gaul in recent times’, used to teach grammar34. In reading (i.e. lecturing on) the auctores, Bernard would point out what was straightforward and in accordance with the rules of composition, and also explain ‘grammatical figures, rhetorical embellishment, and sophistical quibbling’. It would seem that Bernard shared some of Quintilian’s principles and concerns.

Further insight into the priorities of prelectio is provided by a remark of one of Bernard’s pupils, William of Conches, once the teacher of John of Salisbury and of the future King Henry II of England35. In the prologue to his commentary on the Timaeus, William criticised those commentaries and glosses on Plato which attempt to explain the sententiae of a work (i.e. its profound and inner meanings) without having first carefully followed and explained ‘the letter’ of the text36. This point of view was shared by Hugh of St Victor (writing c. 1127), who advocated the following ‘order of exposition’ in studying the Bible: one begins with ‘the letter’, working out the grammatical construction and continuity of a passage; then, one proceeds to expound its sensus or most obvious meaning; and, finally, the sententia or deeper meaning is sought37.

Analysis of both ‘the letter’ of authoritative texts and of the sententiae found therein were, in whatever proportion, essential features of all the teaching conducted within the medieval trivium and quadrivium. (The trivium comprised grammar, rhetoric and dialectic, the inferior group of the seven liberal arts; the quadrivium comprised music, arithmetic, geometry and astronomy, the superior group). In the case of the more specialised disciplines of law, medicine and theology, these procedures were heavily modified to suit the special requirements of the individual subject. But no matter what the subject, the scholar did not compete (he did not even pretend to do so) either with his auctores or with the great works which they had left. One’s whole ambition was directed to understanding the authoritative texts, ‘penetrating their depths, assimilating them and, in the fields of grammar and rhetoric, imitating them’38.

The explication of an auctor in any discipline invariably began with an introductory lecture in which the master would say something about the discipline in general and the purpose and contents of the chosen text in particular. In subsequent lectures, the text would be discussed in minute detail39: so thorough was this analysis that John of Salisbury described it as a ‘shaking out’ of the auctores; they were thereby despoiled of the plumes which they had borrowed from the several branches of learning40. It was in the introductory lecture, and usually only there, that the lecturer would consider the text as a whole, and outline the doctrinal and literary principles and criteria supposed to be appropriate to it. When the series of lectures was written down by pupils, or prepared for publication by the master himself, the opening lecture would serve as the prologue to the commentary on the text.

The academic prologue had different names in different disciplines. Artistae, or students of arts subjects, called it an accessus (though this is essentially a feature of German manuscripts), glossators of the Roman Law called it a materia, while Scriptural exegetes called it an introitus or ingressus41. In the twelfth century, three main types of prologue were employed in introducing an auctor. These three types were identified and described in an article published by R. W. Hunt in 1948, a study to which the following discussion is considerably indebted42. Special reference will be made to the type of prologue which enjoyed the widest application and the greatest frequency of use.

Our first type of prologue (Dr Hunt’s ‘type B’) may have originated in ancient commentaries on Virgil. Its characteristic series of headings, or paradigm, is employed in an introduction to the Eclogues attributed to the fourth-century grammarian, Aelius Donatus. Here the headings are divided into two groups. ‘Before the work’ (ante opus) the title, cause and intention must be investigated while, ‘in the work itself’ (in ipso opere), three things may reasonably be regarded, the number (of the constituent books or parts), order and explanation43. A fuller version of this type of prologue is found at the beginning of the commentary on the Aeneid attributed to Servius, another fourth-century grammarian. However, this elaboration probably represents the accretions of later scholarship:

In expounding authors these things are to be considered: the intention of the writer, the life of the poet, the title of the work, the quality of the poem, the number of the books, the order of the books, the explanation. This is the life of Virgil . . . The title is Aeneis . . . The quality of the poem is obvious, for it is heroic verse mixed with action, where the poet both speaks and introduces others speaking. Moreover, it is heroic because it is made up of divine and human characters, containing truth with fictions . . . The style is grandiloquent, which consists in high speech and in great sententious statements. For we know that there are three kinds of speaking (genera dicendi), the humble, the middle and the grandiloquent. The intention of Virgil is this, to imitate Homer and to praise Augustus through his ancestors . . . Concerning the number of books there is no question . . . There is no question concerning the order of the books—as is found in the case of other authors, for some say that Plautus wrote twenty-one fables, some forty, and others a hundred. The order also is manifest . . . Only the explanation remains, which will be rendered in the following exposition.44

Medieval scholars certainly associated this paradigm with Servius. Writing between 1076 and 1099, Bernard of Utrecht described it as an ancient schema which had fallen out of favour with the moderns, then organised his discussion of Theodulus around its seven headings, citing Servius45. The paradigm was applied to the Paschale Carmen of Sedulius because Sedulius was regarded as a Christian Virgil46. Even as late as the fifteenth century, when a commentator applied it to Ovid’s Metamorphoses, he identified as his model Servius’s commentary on the Aeneid47.

At the head of a life of Virgil found in a ninth-century Wolfenbüttel manuscript, the usual ‘type B’ headings are given,

In the beginnings of books seven summaries, that is circumstances, are required: the life of the poet, the title of the work, the quality of the poem, the intention of the writer, the number of the books, the order of the books, the explanation.48

and then an alternative apparatus is offered, consisting of a quite different series of headings:

But John the Scot briefly wrote these summaries, saying whom, what, why, in what manner, when, where, by what means.49

This seems to point to a major theory of circumstantiae formulated by John Scotus Erigena (c. 810–c. 877), who was made head of the palace school at Laon by Charles the Bald50. Erigena’s role in the development of prologue technique is far from clear51. We are on safer ground when considering the contribution made by Remigius of Auxerre (c. 841–c.908), to whom the Wolfenbüttel life of Virgil has been attributed52.

The main type of prologue associated with Remigius had its origin in the rhetorical circumstances (circumstantiae) or summaries (periochas)53. Ancient rhetoricians had taught that everything which could form the subject of a dispute or discussion was covered by a series of questions which, during successive generations of scholarship, was expanded into seven, namely, ‘whom’, ‘what’, ‘why’, ‘in what manner’, ‘where’, ‘when’ and ‘whence’ (or ‘by what means’). When applied to the grammatical discussion of a text, these circumstantiae provided the basis for a comprehensive and informative prologue (cf. Dr Hunt’s ‘type A’)54. A good example is furnished by Remigius’s accessus to Martianus Capella55. This begins with the claim that, at the beginning of all authentic books, one must go through the seven circumstantiae, which are then listed in Greek together with their equivalents in Latin. The question ‘who?’ requires to be answered by a statement concerning the person (persona) responsible for the work, its auctor, who, in this case, is Martianus. The question ‘what?’ refers to the thing, the text itself, and is answered with a statement of the book-title. ‘Why’ did Martianus write? Because he wished to dispute concerning the seven liberal arts. The question ‘in what manner?’ inquires the particular mode (modus) or fashion in which he wrote, Remigius’s answer being that, in De nuptiis Philologiae et Mercurii both verse and prose are used. ‘Where’ did Martianus write? The place (locus) where the book was written was Carthage. ‘When’ did he write? The time (tempus) of composition is uncertain. Finally, the question ‘whence?’ inquires the materials from which the book was written, namely, the marriage of Philology and Mercury, and the seven liberal arts in general.

A shortened version of this scheme, comprising the three headings persona, locus and tempus, is employed elsewhere by Remigius, for example, in his Commentarius in artem primam Donati and in a commentary of dubious attribution on Bede’s De arte metrica56. In the accessus to the Disticha Catonis and Priscian’s Institutio de nomine, pronomine et verbo, a fourth heading, causa scribendi (‘why’ the work was written), is added to the other three57.

The threefold scheme had already been used by theologians. In the commentary on Ezechiel by St Gregory the Great (c. 540–604) and the commentary on the Apocalypse by the venerable Bede (c. 673–735), reference is made to the persona, locus and tempus of each Scriptural auctor58. By the time of Christian of Stavelot, the use of these headings in Scriptural exegesis seems to have been well-established: the prologue to his commentary on St Matthew’s Gospel (composed shortly after 864) contains the statement that ‘in the beginning of all books three things must be inquired, the time, the place, and the person’59. In the twelfth century, Hugh of St Victor habitually used the threefold scheme in his Bible commentaries60. In the thirteenth century, Hugh of St Cher made occasional use of the headings locus and tempus in prologues which derive their structure from a different series of headings61.

But the two types of prologue described above were relatively rare in the twelfth century. The ‘type B’ prologue-paradigm seems to have been regarded as over-elaborate; it may have been too specialised for general use. The Servian model is not followed in the prologue to the Aeneid commentary attributed to Bernard Silvester62. Hugh of St Victor’s systematic use of the ‘type A’ prologue-paradigm is most unusual in the Scriptural exegesis of that period. However, certain items of vocabulary from both these prologue-paradigms seem to have influenced the most popular of all twelfth-century academic prologues.

The origins of this prologue (Dr Hunt’s ‘type C’) are obscure, but it would seem that Boethius was the main channel through which it was disseminated in the Latin West63. In the first version of his commentary on Porphyry’s Isagoge, Boethius listed six headings and provided their Greek equivalents: the intention of the work (operis intentio), its usefulness (utilitas), its order (ordo), if it is indeed a genuine work of the putative author (si eius cuius esse opus dicitur germanus propriusque liber est), the title of the work (operis inscriptio) and the part of philosophy to which it pertains (ad quam partem philosophiae cuiuscumque libri ducatur intentio)64. All these topics, Boethius claimed, must be investigated and brought forth at the beginning of every book of philosophy.

This reference to philosophical books provides a clue to Boethius’s models. E. A. Quain has argued that the Greek schema cited in the Isagoge commentary was developed in late-antique Greek commentaries on certain works of philosophy65. He compares the glosses on Aristotle’s Categories written by Ammonius of Alexandria and his disciples, Philoponus, Elias and Simplicius, which began with systematic introductions in the form of ten major questions66. The all-important tenth question provided a series of headings which was the basis for literary analysis of each separate work. For example, Simplicius’s list is as follows: intention, usefulness, cause of the title, the order (in which the Categories is to be read within the Aristotelian corpus), its authenticity, and its disposition or arrangement67. The late-antique introductions to Porphyry, as G. L. Westerink has pointed out, were more varied; ‘as time goes on, they tend to become more prolix and more schematic’68. In such introductions, to the six headings employed in introducing Aristotle (as noted above) was added a seventh, the branch of philosophy to which the text belongs, here said to be logic69. This version of the schema obviously lies behind the version used in Boethius’s commentary on Porphyry. In passing, it should be noted that the Alexandrian school produced elaborate introductions to Plato also, which were organised in accordance with different principles70. However, this schema does not seem to have survived into the Middle Ages71.

Whatever the origins of the ‘type C’ prologue may be, when it began to be popular in medieval exposition of auctores, its distinctive vocabulary was regarded as a ‘modern’ apparatus which had replaced the ‘ancient’ schema based on the circumstantiae. There are several eleventh-century statements to this effect. For example, in a reworking of Remigius of Auxerre’s commentary on the Disticha Catonis, it is claimed that

In the exordium of every book seven things were examined beforehand by our predecessors: whom, what, where, with what aids, why, in what manner, when. . . . But in the manner used among the moderns only three things are required: the life of the poet, the title of the work and to what part of philosophy it pertains.72

In the late eleventh-century Commentum in Theodulum by Bernard of Utrecht, we are told that the ‘ancients’ used to apply the seven circumstantiae at the beginning of every book, whereas the ‘moderns’ investigate instead the material of the work, the intention of the writer, the part of philosophy to which the book pertains, and its utility73. A similar comment is found in Conrad of Hirsau’s Dialogus super auctores, a work which seems to have been influenced by Bernard of Utrecht’s commentary74. All these accounts seem to point to the emergence of the ‘type C’ prologue-paradigm as the dominant form.

In the systematisation of knowledge which is characteristic of the twelfth century, the ‘type C’ prologue appeared at the beginning of commentaries on textbooks of all disciplines: the arts, medicine, Roman law, canon law and theology. Its standard headings, refined by generations of scholars and to some extent modified through the influence of the other types of prologue, may be outlined as follows:

According to Remigius of Auxerre, the title was the key to the work which followed it75. It could refer to the author or to some other person, or to a place, literary genre or subject76. The term titulus was supposed to be derived from titan, the sun: just as the sun illuminates the world, the book-title illuminates the book!77

Discussion under this heading could involve complicated and often specious etymologies of the words that comprised the title. For example, in introducing the Pharsalia, Arnulf of Orléans (fl. 1175) gave its title as Marci Annei Lucani Liber. Lucanus is interpreted as ‘lucidly singing’ (lucide canens); Anneaus is supposed to be derived from the Greek word for bees78. Commentators on Boethius laboriously expounded in this manner each element of the title Anicii Mallii Severini Boetii ex magno officio viri clarissimi et illustris exconsulum ordine atque patricio liber philosophicae consolationis primus incipit79. Severinis refers to the severity of Boethius’s judgments; Boethius is from a Greek word which may be interpreted as ‘the helper and consoler of many’, and so on.

In discussion under this heading, the issue of authenticity was usually raised, the commentator either naming his author or recounting the theories concerning the author’s identity. Sometimes, a short life of the author (vita auctoris) was provided.

Here the commentator explained the didactic and edifying purpose of the author in producing the text in question. Sometimes, the term finis (i.e. ‘end’, ‘objective’) was used as an equivalent of this heading, and sometimes as an extension of it80. The reader of a work should regard authorial intention as the kernel, claimed Dominicus Gundissalinus (writing shortly after 1150): whoever is ignorant of the intentio, as it were, leaves the kernel intact and eats the poor shell81.

Accounts of the intentio auctoris range from the very obvious to the very elaborate. The former may be illustrated from one of the earliest extant commentaries on Cicero’s De inventione. Writing in the early twelfth century, Thierry of Chartres briefly stated that, in this work, Cicero had intended to treat of a single part of the art of rhetoric, namely, invention82. Good examples of the latter are furnished by statements concerning the purpose of the Justinian Code made by glossators of the Roman law: the different contributors to this work were supposed to have had different intentions. In the Summa Trecensis, which he wrote around 1150, Rogerius explained that the intention of the Roman princes was to establish laws concerning basic equity and to formulate them as precepts, while the intention of Justinian was to cull the best of this ancient material and render it in one volume83.

In the case of the study of grammar, accounts of authorial intention were prescriptive rather than descriptive: there was rarely any attempt (at least, not until very late in the Middle Ages) to relate a person’s purpose in writing to his historical context, to describe ah author’s personal prejudices, eccentricities and limitations. The commentators were more interested in relating the work to an abstract truth than in discovering the subjective goals and wishes of the individual author. The intentio auctoris—the intended meaning ‘piously expounded’ and rendered unimpeachable—was considered more important than the medium through which the message was expressed84. Texts of profane auctores were interpreted, and sometimes elaborately allegorised, so that they could be seen to contain nothing contrary to Christian truth. The poets had used a fictional garment or integumentum to clothe either truths about natural science or profound moral doctrine85. According to the commentators, Homer had intended to dissuade people from unlawful union which, as in the example of Paris and Helen, incurs the wrath of the gods; Ovid had intended to reprehend inchastity and to commend legal and just love; Lucan had intended to discourage his readers from engaging in civil wars86. On the other hand, the obviously moral statements of satirists like Horace and Persius could be taken literally87.

In the case of sacred Scripture, no special pleading was believed to be required, because the intentions of the divinely-inspired auctores had been determined by the Holy Spirit.

As one might expect, some of the most sophisticated discussions of this kind are found in the Roman lawyers’ materiae or introductions to the Justinian Code. The ‘common material’ of the Code consisted of those legal issues common to Justinian and the Roman princes; its ‘singular and proper material’ was supplied by the three ancient legal codices which Justinian had reconciled and edited88. A similar technique of analysis is found in the prologues to glosses on Gratian by canon lawyers89.

Under this heading, commentators described the stylistic and rhetorical qualities of the authoritative text, always being concerned to bring out the instructional and pedagogic value of the literary medium. For example, in an accessus to a ‘Cornutan’ commentary on Persius, the didactic efficacy of the author’s ‘low style’ is defended with reference to an etymology of the term satira, whereby the literary form is supposed to be named after the goat-like satyrs90. The satyrs are depicted naked; similarly, satire employs a plain and unembellished style. In its use of vulgar words, it differs from tragedy, which always uses elevated language. Moreover, a satire jumps about, in the fashion of a goat, because it has neither a circumscribed theme nor a flowing rhythm. The goat is a stinking animal, and satire employs pungent and unpleasant words. By such drastic methods, the satirist made manifest his moral outrage and censured the vices of men.

The various modes of procedure used by different authors might be compared and contrasted. In William of Conches’s prologue to his commentary on De consolatione philosophiae; it is explained that Boethius imitated the modus scribendi of Martianus Capella by writing in prose and verse91. Consolation entails both reason and delight, claimed William, and so, Boethius used two modes: in prose, he consoles by rationalisation; in metre, he interposes delight so that grief is forgotten.

Certain theologians applied secular literary theory to the stylistic analysis of sacred Scripture. In expounding the Psalter’s modus tractandi (c. 1144–69) Gerhoh of Reichersberg employed the distinction between the three ‘styles of writing’ (characteres scripturae) which goes back to Servius’s commentary on Virgil’s Eclogues92. Gerhoh tells us that the style of a work can be called ‘exegematic’ when the auctor speaks in his own person; ‘dramatic’, when the auctor speaks ‘in the persons of others’; and ‘mixed’, when both these styles are used. In the Pentateuch, Moses speaks in his own person; in the Song of Songs, the introduced persons speak; while, in the Apocalypse and in the Consolatio philosophiae of Boethius, the auctor speaks both in his own person and through others. The Psalter has, according to Gerhoh, a complex modus tractandi. Considered as a whole, it could be said to use the mixed mode, but one or other of the three characteres may be used in a given psalm.

Here the author’s deployment or arrangement of his materials was discussed. Sometimes literary arrangement was discussed as a facet of the modus tractandi; sometimes it was allotted a separate heading. In narrative, there were believed to be two sorts of order, the natural and the artificial. According to ‘Bernard Silvester’, natural order follows the historical sequence of events, as in the narrative of Lucan, while artificial order begins in the middle of a narration and returns to the beginning, as in Terence’s works and Virgil’s Aeneid93.

Sometimes this interest in order extended to declaring the number of chapters in a work. A book is divided in parts or chapters, said Gundissalinus, so that, when something is sought among all the things contained therein, it is the more easily found94. It is easier, in such a case, to have recourse to a definite chapter than to read over the whole volume. With the help of distinct chapters, he concluded, the memory is much strengthened.

Of course, some works, by their very nature, were not susceptible of chapter-division. In describing the modus tractandi of the Consolatio philosophiae, William of Conches explained that Boethius proceeds from one kind of proof to another, this being the basis for his organisation of doctrine95. First, Boethius employs rhetorical arguments, then dialectical arguments and, finally, demonstrations.

This heading introduced a consideration of the ultimate usefulness of the work, i.e. the reason why it was part of a Christian curriculum. The utility of the Bible was self-evident; works of lesser authority required some justification. Hence, Arnulf of Orléans claimed that the utility of Lucan’s Pharsalia is very great because, through his narration of the dreadful deaths of Pompey and Caesar, Lucan warns us not to engage in civil wars96. The beast-fables of Avianus were said to be useful, in so far as they gave delight and taught the correction of mores97. The more sombre writings of the Roman satirists were useful because they harshly reprehended vice and recommended virtue: the censures by Juvenal and Persius of ‘poets writing to no purpose’ (poetas inutiliter scribentes) won much approval98. ‘Bernard Silvester’ stated that some poets write because of utility, like the satirists, and some write because of delight, like the writers of comedies, while others both instruct and please, as do the historians99.

In the widest sense of the term, ‘philosophy’ included all human knowledge and investigation. Hence, Bernard of Utrecht defined philosophy as the knowledge of things human and divine, joined to the study of living well; it comprises science, in the case of certainties, and opinion in those areas where certainty is not possible, and may be either contemplative or active100. Similarly, Hugh of St Victor stated that philosophy is the discipline which investigates demonstratively the causes of all things, human and divine; the theory of all pursuits, therefore, belongs to philosophy, which can be said to embrace all scientific knowledge101. Hugh then classified the parts of philosophy as follows:

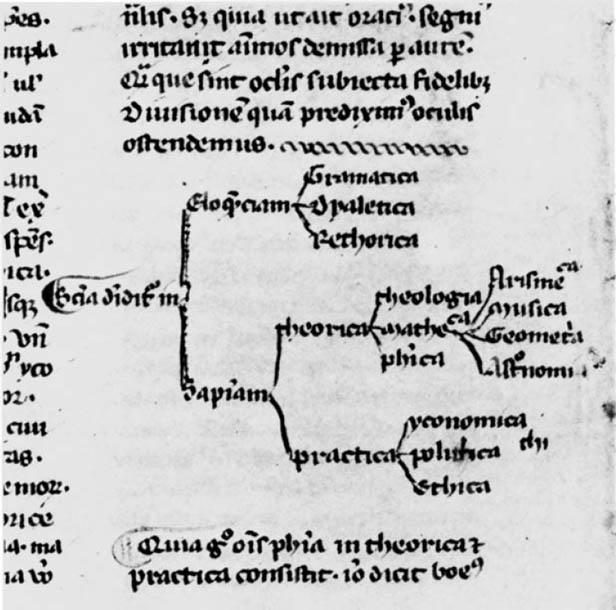

1 THE BRANCHES OF LEARNING (see pp. 23–7). London, British Library, MS Royal 15.B. III, fol. 7v. William of Conches, commentary on Boethius’s De consolatione philosophiae.

Philosophy is divided into theoretical, practical, mechanical, and logical. These four contain all knowledge. The theoretical may also be called speculative; the practical may be called active, likewise ethical, that is, moral, from the fact that morals consist in good action; the mechanical may be called adulterate because it is concerned with the works of human labour; the logical may be called linguistic from its concern with words.102

The texts used in the teaching of the various disciplines had to be related to a system such as this, and given their proper status within it.

The pars philosophiae of the Roman law was classified as ethics, a practice which, as Kantorowicz says, ‘had the advantage of reminding the budding medieval lawyer that the civil law was more than a jungle of technicalities’103. Much more surprising on first acquaintance is the frequent claim by artistae that all their auctores belonged to the study of ethics or practical philosophy104. In twelfth-century schools, the study of ‘natural’ or non-Christian ethics was an adjunct of the traditional studies of the trivium; its usual contexts were rhetoricians’ explanations of the virtues necessary to deliberative and demonstrative oratory and grammarians’ expositions of pagan literature105. Hence, Lucan was believed to offer us worthy models of behaviour to imitate, models exemplifying the four political virtues, which pertain to ethics106. Even Ovid’s erotic love-poetry was supposed to have an ethical function because it exemplified the legal and chaste love which one ought to practise and the reprehensible kinds of love which one ought to avoid107.

Of course, not everyone was in favour of such classification, as may be illustrated by the difference of opinion between Bernard of Chartres and his pupil, William of Conches, which is recorded in a twelfth-century commentary on Juvenal108. Having raised the issue of the part of philosophy to which Juvenal’s satires belong, the anonymous commentator claims that Bernard thought this question irrelevant because poetry does not treat of philosophy. But William of Conches, he continues, made a distinction between mere writers (actores) and writers who are authorities (auctores). The works of actores do not pertain to philosophy, but the works of auctores, although they do not teach philosophy directly, nevertheless relate to philosophy in that they provide moral instruction and, thereby, pertain to ethics. It would seem then, that to assign the pars philosophiae of a given text was to make a judgment concerning its auctoritas.

Scriptural texts presented considerable problems of classification, because of their variety and scope; moreover, one had to do justice to the general complexity and superiority of the God-given doctrine contained therein. Origen (c. 185–c. 254), as translated by Rufinus, argued that all the Greek sages had borrowed their ideas of the branches of learning from Solomon (who had acquired this information through the Holy Spirit long before their time), and that they had put them forward as their own inventions109. Similar theories concerning the origin of the liberal arts were held by such scholars as Jerome, Augustine and Cassiodorus110. According to Origen, three works traditionally attributed to King Solomon, namely, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes and the Song of Songs, taught the subjects of ethics, physics and the theoretical or contemplative science, respectively111. In Isidore’s Etymologiae, it is claimed that Genesis and Ecclesiastes teach natural philosophy, which the Greeks call physics; Proverbs and other books teach moral philosophy or ethics; while the Song of Songs and the Gospels teach rational philosophy or logic, in this case to be identified with theoretical science112. The same basic classification is advanced in the Glossa ordinaria on the Song of Songs and in glosses to that same text ascribed to Anselm of Laon († 1117) and Richard of St Victor († 1173), as well as in commentaries on the Psalter attributed to Remigius, St Bruno the Carthusian (c. 1032–1101) and Honorius ‘of Autun’ (†c. 1156)113.

In the prologue to the Psalter-commentary attributed to Remigius, we find this significant remark: ‘Just as in mundane books so also in divine books one can inquire which part of philosophy is in view’114. An investigation, apparently commonplace in discussion of secular writing, is being conducted in the case of inspired Scripture, the implication being that this is something of an innovation. In reiterating the Isidorian classification, the commentator points out that one cannot speak of logic when dealing with the Bible: in its place stands theoretical science, the pars philosophiae of the Song of Songs and the Evangelists. Bruno the Carthusian introduced a similar threefold division with the statement that ‘three things are to be considered in divine books just as in secular books’115.

These remarks seem to indicate a conscious transition from secular to sacred which is being made with a degree of reticence. The same impression may be gained from this twelfth-century gloss on the Apocalypse:

Just as in secular books it is asked what is the material, what is the authority, what is the intention of the author, and which part of philosophy is supposed, so also it must be asked in this prophetic writing.116

In order that the ‘type C’ prologue could be applied in Scriptural exegesis, some modification of its paradigm was necessary. Medieval theologians were very conscious of the supreme eminence of their discipline, and of the unique status of their essential textbook, the Bible. Theology was, in the words of Hugh of St Victor, the ‘peak of philosophy and the perfection of truth’117. Hence, the heading cui parti philosophiae supponitur was either a challenge or an irrelevance, depending on the exegete’s point of view118. This range of possible response may be illustrated by contrasting the notes taken by two students at Stephen Langton’s lecture course on the Song of Songs (perhaps held in the third quarter of the twelfth century). One student mentions ‘the aspect of philosophy or of humanity’ (pars philosophiae vel humanitatis) to which the Scriptural text pertains; the other avoids this cumbersome heading and concentrates on Langton’s discussion of the relevant ‘aspect of life’ (pars vitae), namely, the contemplative life119. Most twelfth-century commentators on the Psalter ignored the heading pars philosophiae altogether and discussed instead the ‘species of prophecy’ (pars prophetiae) to which David’s prophecies belonged120.

This completes our illustration of the usual kinds of discussion conducted under the various headings of the most popular of all the prologue-paradigms used in the twelfth century. The felicities and limitations of prologues of this type as sources of literary theory will be discussed in our next chapter. For the moment, it must suffice to state that change came in the thirteenth century. The stock schema was supplemented; its technical idiom acquired greater precision and, in the case of prologues to Bible-commentaries, a more literary dimension. The new methods of thinking and techniques of study which thirteenth-century scholars derived from their reading of Aristotle encouraged commentators to adopt and develop a new type of prologue, based on the Aristotelian concept of ‘the four causes’.

Aristotle had defined the ‘formal cause’ of something as its substance, i.e. the essence or the pattern which ‘enformed’ the thing, while the ‘material cause’ meant its matter or substratum121. The ‘efficient cause’ consisted of motivation, the moving force which brought something from potentiality into actual being. Diametrically opposite to the efficient cause was the ‘final cause’, the end or objective which was aimed at and intended: Aristotle saw the function of all generation and change in terms of a hierarchy of ultimate goals and goods. To expand an illustration from the commentary on Aristotle’s Physica by St Thomas Aquinas (written 1269–70 at Paris), the formal cause of a statue is its shape, i.e. the proportions and disposition of the constituent parts, while its material cause is the bronze from which it is made122. The efficient cause is the artificer or craftsman who made the statue, while the final cause is his reason for making it.

When applied to the exposition of auctores, this theory of causality produced a sophisticated prologue-paradigm which, hereafter, I shall refer to as the ‘Aristotelian prologue’. The characteristic headings of the ‘Aristotelian prologue’ may be outlined as follows:

The efficient cause was the auctor, the person who brought the literary work into being. This heading replaced, or was used in conjunction with, nomen auctoris. Here the issue of authenticity was discussed which, in the case of prologues to Scriptural texts, entailed description of the causation whereby the divine auctor had directed the human auctores to write.

The material cause was the substratum of the work, i.e. the literary materials which were the writer’s sources. The heading replaced, or was used in conjunction with, materia libri.

The formal cause of the work was the pattern imposed by the auctor on his materials. Commentators spoke of the twofold form (duplex forma), the forma tractandi, which was the writer’s method of treatment or procedure (modus agendi or modus procedendi), and the forma tractatus, which was the arrangement or organisation of the work, the way in which the auctor had structured it.

The final cause was the ultimate justification for the existence of a work, the end or objective (finis) aimed at by the writer; more specifically, the particular good which (in the opinion of the commentator) he had intended to bring about. In the context of commentary on secular auctores, this meant the philosophical import or moral significance of a given work123; in the context of Scriptural exegesis, it meant the efficacy of a work in leading the reader to salvation.

Of course, certain aspects of Aristotle’s theory of causality had been known before the thirteenth century. An important locus classicus was provided by the brief statement in Cicero’s Topica concerning the efficient cause and the material cause; in his commentary on this passage, Boethius had supplied a cogent summary of the four causes according to Aristotle124. However, while some twelfth-century commentators spoke of the causa finalis of a work (instead of, or in conjunction with, its utilitas), the complete system of the four causes was not applied125.

The impetus for change seems to have been provided by the extensive accounts of causality contained in Aristotle’s Physica and Metaphysica, works which were being admitted to the curriculum of studies in the early thirteenth century126. At any rate, it was during that period that the ‘Aristotelian prologue’ became very popular among lecturers in the arts faculty of the University of Paris127. Its sophisticated analytical framework soon appeared at the beginning of commentaries on the textbooks of other disciplines, including astronomy, canon law and medicine128. Theologians used it in introducing their commentaries on the Bible and on Peter Lombard’s Libri sententiarum, then an established teaching-text in the faculty of theology129. The ‘Aristotelian prologue’ and, indeed, the ‘type C’ prologue which it never wholly superseded, continued to be employed in the study of auctores long into the Renaissance130.

All the types of academic prologue considered so far were designed to lead the listeners or readers into authoritative texts. This function was sometimes emphasised by the designation ‘intrinsic’: the ‘intrinsic’ prologue, or the ‘intrinsic’ component of a prologue, introduced a text. It might be preceded by an ‘extrinsic’ prologue or component, in which the discipline to which the text belonged was identified and described in a systematic way. Therefore, the medieval distinction between extrinsic and intrinsic analysis hinged on a difference in the object of analysis rather than differences of vocabulary or ideology: the former concerned an art or science, while the latter concerned a text. The origins and development of this distinction must now be examined.

Cicero’s rhetorical theory seems to be the ultimate source of the common twelfth-century differentiation between the ars extrinsecus and ars intrinsecus. In his Topica, Cicero divided the topics under which arguments are included into two large groups131. Some are inherent in the very nature of the subject which is under discussion (in eo ipso); others are brought in from without (extrinsecus). In the first category are arguments derived from the whole, from its parts, from its meaning, and from the things which are in some way closely connected with the subject under investigation. In the second category are arguments from external circumstances, i.e. those which are removed and widely separated from the subject. In the commentary on Cicero’s De inventione by the fourth-century rhetorician Victorinus, this approach was applied to the arts, the phrase in eo ipso being replaced with the term intrinsecus132. Victorinus, citing ‘the precept and sententia of Cicero’, claimed that ‘every art is twofold, that is, it has a double aspect’. The extrinsic art gives us knowledge alone; the intrinsic art shows us the reasons whereby we put into practice that which knowledge gives us133.

Thierry of Chartres (who became chancellor of Chartres in 1141) took over this distinction from Victorinus. Introducing his commentary on the De inventione, Thierry stated that the ancient rhetoricians, in defining and dividing an art, called the extrinsic art that which it is necessary to know in advance before commencing to practise an art, while the intrinsic art comprised the rules and precepts which we must know in order to practise the art itself134.

Thierry also distinguished between those things it is necessary to know concerning the art (circa artem) and concerning the book under discussion (circa librum) respectively135. Concerning Cicero’s work, two things must be considered, the intention of the author (intentio auctoris) and the utility of the book (libri utilitas): these headings are familiar to us as part of the ‘type C’ prologue-paradigm. Concerning the art of rhetoric, ten things must be considered: its genus (genus), what the art is in itself (quid ipsa ars sit), its material (materia), its office (officium), its end (finis), its parts (partes), its species (species), its instrument (instrumentum), its master or practitioner (artifex), and wherefore it is called rhetoric (quare rhetorica vocetur)136. This series of prologue-headings (Dr Hunt’s ‘type D’) seems to have its origin in the De inventione; in his De differentiis topicis Boethius had amplified Cicero’s version137.

In the prologues to commentaries on grammatical texts, the headings extrinsecus and intrinsecus took over the functions performed by the headings circa artem and circa librum in Thierry’s schema138. The heading extrinsecus introduced a discussion of the place in the scheme of human knowledge occupied by grammar, together with a summary of the defining characteristics of this art, while the heading intrinsecus introduced a schematic discussion of the text itself. Thus, the anonymous late twelfth century gloss on Priscian which begins Tria sunt proceeds as follows:

The extrinsic aspect is taught when by inquiring the nature of this same art we learn what this art is, what is its genus, material, parts, species, instrument, master, office, end, wherefore it is named, in what order it is to be taught and learned . . .

The intrinsic aspect is to be explored by considering first what is the author’s intention in this work, what is its utility, what are the causes of the undertaken labour or work, what is the order, and finally what is its title.139

Combinations of the conventional extrinsic discussion with the ‘type C’ prologue-paradigm occurred from the mid twelfth century onwards, the general analysis of the relevant art or science preceding application of such characteristic intrinsic headings as auctoris intentio, utilitas and modus agendi140. Scholars wished to have parallel discussions of the art in general and the text in particular. As a result, the extrinsic series was sometimes modified in accordance with the usual intrinsic headings.

The most elaborate application of both series of headings occurs in the De divisione philosophiae of Dominicus Gundissalinus, one of the group of translators gathered together by Raymond, Archbishop of Toledo (1126–51), and still alive in 1181. In this work, a detailed analysis of the individual branches of knowledge, extrinsic headings provide the structure for discussions of the following parts of speculative philosophy: natural science, mathematics, divine science, grammar, poetics, rhetoric, logic, medicine, arithmetic, music, geometry, astrology and astronomy141. At the very end of the De divisione, Gundissalinus says that, concerning a book (circa librum) of any art whatsoever, seven things are to be investigated. There follows a discussion of the literary concepts of intentio auctoris, utilitas operis, nomen auctoris, titulus operis, ordo legendi, ad quam partem philosophiae spectet and distinctio libri142.

In the thirteenth century, Aristotelian science fostered a new kind of extrinsic prologue in which the discipline was delimited and subdivided by a conceptual method of ‘means’ and ‘ends’. The subject, mode of procedure and end of an individual art or science were discovered by defining the place it occupied within an Aristotelian hierarchy of knowledge143. A commentary could begin with an extrinsic investigation conducted along these lines; then the intrinsic features of the text itself would be investigated. For example, in the commentary on the recently-recovered Nicomachean Ethics of Aristotle which he produced around the middle of the thirteenth century, St Albert the Great first discussed the materia, finis and utilitas of moral science, then proceeded to identify the work’s titulus, materia, auctor and causa144. Sometimes the intrinsic discussion was organised around the four causes. This practice is found in many commentaries on books of the Bible, a good example being provided by the prologue to the commentary on the Pauline Epistles written by St Thomas Aquinas between 1270 and 1272145. Alternatively, the four causes could provide the basic framework for a discussion of the extrinsic and intrinsic aspects of a text considered together. This is the case in two commentaries on Peter Lombard’s Libri sententiarum, one composed by St Bonaventure between 1250 and 1252 and the other by Robert Kilwardby between 1248 and 1261146. By the fourteenth century, there were several possible permutations.

This completes our review of the types of academic prologue which prefaced commentaries on auctores. We have described the most important kind of prologue established in the twelfth century (Dr Hunt’s ‘type C’) and its thirteenth-century successor (the ‘Aristotelian prologue’). A distinction has been made between the ‘extrinsic’ prologue, which introduced an art or science, and the ‘intrinsic’ prologue, which introduced the book that taught the art or science in question. We are now in a position to begin an investigation of the theory of authorship found in prologues to commentaries on the most ‘authentic’ of all books, the Bible. The supreme authority of sacred Scripture must be emphasised at the outset, so that we may understand better the literary problems which it presented to its medieval readers.

Medieval theologians were eminently aware of both the comparisons and the contrasts which could be made between the Bible and secular texts. On the one hand, they stressed the unique status of the Bible; on the other, they believed that the budding exegete had to be trained in the liberal arts before he could begin to understand the infinitely more complex ‘sacred page’.

These attitudes and priorities can be traced back to the Church Fathers. H.-I. Marrou has demonstrated the influence of late-antique school practice, including the methods of grammatical training, on the Biblical exegesis of St Augustine (354–430)147. Yet Augustine professed a preference for substance rather than expression, for content rather than form148. Similarly, St Jerome insisted on the primacy of sense (sensus) over words (verba)149. Even Cassiodorus (c. 485–c. 580), characterised by P. Riché as ‘an untitled teacher of grammar and rhetoric’ in his monastery, admitted that the rules of Latin discourse are not to be followed everywhere: ‘sometimes it is better to overlook the formulas of human discourse and preserve rather the measure of God’s word’150. In the dedicatory letter to his moral commentary on Job (580–95), St Gregory the Great warned the reader not to look for ‘literary nosegays’, because, in interpreters of Holy Writ, ‘the lightness of fruitless verbiage is carefully repressed, since the planting of a grove in God’s temple is forbidden’151. Gregory rejected as ‘unbecoming’ the notion that he should ‘tie down the words of the heavenly oracle to the rules of Donatus’.

The unique status of the heavenly oracle is brought out in the model of Biblical exegesis provided in Gregory’s Moralia in Job. Traditional techniques of textual commentary have been altered to meet the special demands of divinely-inspired Scripture. Whereas the Roman grammaticus had been interested in analysis of historical or literal sense (regarded by Gregory as explanation of all the meanings of the narrative), the exegete was obliged to concentrate on the spiritual senses. Gregory therefore offered a threefold method of exposition—

we run over some topics in historical exposition, and in some we search for allegorical meaning in our examination of types; in still others we discuss morality but through the allegorical method; and in several instances we carefully make an attempt to apply all three methods

—which was influential throughout the Middle Ages152. Equally popular was the fourfold method ultimately derived from John Cassian (c. 360–435), which was conveniently summarised in a well-known distich:

Littera gesta docet, quid credas allegoria,

Moralis quid agas, quo tendas anagogia.153

The literal sense provides the historical data; the allegorical, that which one should believe by faith; the tropological or moral, how one should behave; the anagogical, where one is going in terms of spiritual progress. Cassian’s test-case of the word ‘Jerusalem’ is cogently paraphrased in the short ‘treatise on the way a sermon ought to be composed’ which Guibert of Nogent wrote (shortly before 1084) as a preface to his commentary on Genesis:

There are four ways of interpreting Scripture . . . The first is history, which speaks of actual events as they occurred; the second is allegory, in which one thing stands for something else; the third is tropology, or moral instruction, which treats of the ordering and arranging of one’s life; and the last is ascetics, or spiritual enlightenment, through which we who are about to treat of lofty and heavenly topics are led to a higher way of life. For example, the word Jerusalem: historically, it represents a specific city; in allegory it represents holy Church; tropologically or morally, it is the soul of every faithful man who longs for the vision of eternal peace; and anagogically it refers to the life of the heavenly citizens, who already see the God of Gods, revealed in all His glory in Sion.154

This special type of prelectio had as its overriding concern the unique message of Holy Scripture155. Yet systematic analysis of ‘the letter’ was indubitably an essential part of exegesis, and, in this context, the Bible could be compared with secular works156. In De doctrina Christiana, St Augustine admitted that he took great delight in the stylistic figures found in the Bible. In some cases, he explains, it is pleasanter to have knowledge communicated through figures. The Holy Spirit, ‘with admirable wisdom and care for our welfare, so arranged the Holy Scriptures as by the plainer passages to satisfy our hunger, and by the more obscure to stimulate our appetite’157. Men of learning, Augustine continues, should know that the sacred auctores used all the modes of expression which grammarians call tropes, in great abundance and with great eloquence158. Similarly, St Jerome had believed that all kinds of figures could be found in the Bible: after all, the liberal arts had existed before the profane masters of secular letters had studied them159. Hence, in the prologue to his commentary on Isaiah, Jerome could claim that this work comprised the whole of physics, ethics and logic160. Following the lead of Jerome and Augustine, Cassiodorus managed to find some 120 rhetorical figures in the Psalter161.

In the twelfth century, such comparing and contrasting of the Bible with other books was a regular feature of the debate concerning the true hierarchy of the branches of knowledge and the correct order in which the different arts and sciences should be studied. Hugh of St Victor believed that ‘all natural arts are related to divine science in such a way that the inferior science, correctly organised in the hierarchy, leads to the superior’162. The declared purpose of Hugh’s Didascalicon is to recommend proficiency in the liberal arts within a programme of study which culminated in the exposition of sacred Scripture163. In Conrad of Hirsau’s Dialogus super auctores, which incorporates earlier accessus material on a wide range of auctores, the master warns his pupil that secular writings are not to be studied for their own sake, but as a necessary preparation for analysis of the more difficult texts of Holy Writ164. This was the intellectual milieu in which Rupert of Deutz (c. 1075–1129) was prepared to accept that all the artifices found in secular books were present in Scripture also: schemata, tropes, modes of verse and prose, and even fables165. Augustine, Jerome and Cassiodorus are echoed in Rupert’s statement that Scriptural auctores had used these devices before their supposed inventors had even been born166. Here, then, is the rationale for the theologians’ use of accessus terms of reference in their prologues.

As the ‘Book of Life’ and the book of books, the Bible was the most difficult book to describe with accuracy and appropriateness. To the study of the ‘sacred page’ a scholar would bring the procedures and techniques which he had acquired during his studies in the trivium (although it must be said that some scholars brought more of this learning to bear than others)167. Theologians regularly drew on the resources of secular literary theory, refining and modifying it in accordance with their special needs. When it proved inadequate, they went beyond it, thereby bringing out the uniqueness of Scripture168. Consequently, the study of the Bible occasioned much of the most sophisticated literary theory of the later Middle Ages.

We shall be concerned with two major aspects of the theologians’ literary theory, namely, their discussions of the specific roles (both literary and moral) performed by the different auctores of Scripture, and of the literary forms, genres, styles and structures employed in the different books of the Bible. The changing attitudes to these issues from the twelfth through the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries can only be understood in the light of one fundamental fact about the medieval study of auctores: the prescribed writers, in whatever discipline, were authorities to whom the reader had to defer.

A study of the teaching of grammar in the Middle Ages led C. Thurot to the conclusion that, in explicating their texts, the glossators did not seek to understand the individual thought of each writer but rather to teach the veritable knowledge that was supposed to be contained therein. An auctor in grammar

could neither make a mistake, nor contradict himself, nor follow a defective plan, nor be in disagreement with another authoritative writer. They [the glossators] had recourse to extremely forced artifices of exposition to accommodate the letter of the text to what was considered to be the truth.169

In the teaching of theology, the obligation to defer to one’s auctores was, of course, considerably greater, and most of all in studying the Bible. God, who had guaranteed the superlative auctoritas of Scripture, was the auctor of all created things as well as an auctor of words170. He could deploy words by inspiring human authors to write, and deploy things through his creative and providential powers. Faced with these awesome truths, theologians experienced great difficulty in assessing the relative functions of God and man in producing sacred Scripture.

The literary poles between which the medieval theologians moved may be defined by reference to St Gregory’s excursus on the authorship of the Book of Job, a most striking analysis which influenced later approaches to other Scriptural auctores171. Gregory asked, who was the writer of the work in question? Was it Moses, writing about a gentile named Job? Or was it one of the prophets? Certainly, one might say that only a prophet could possibly have possessed such knowledge of the mysterious words of God as is manifest in this work. Then Gregory seems to dismiss the problem altogether, along with the human writer:

It is very superfluous to inquire who wrote the work, since by faith its author is believed to have been the Holy Spirit. He then himself wrote them, who dictated the things that should be written. He did himself write them who both was present as the inspirer in that Saint’s work and by the mouth of the writer handed down to us his [i.e. Job’s] acts as patterns for our imitation.172

The human writer of the Book of Job is then, rather disparagingly, compared to the pen with which a great man has written a letter:

If we were reading the words of some great man with his epistle in our hand, yet were to inquire by what pen they were written, doubtless it would be an absurdity, to know the author of the epistle and understand his meaning, and notwithstanding to be curious to know with what sort of pen the words were marked upon the page. When then we understand the matter, and are persuaded that the Holy Spirit was its author, in raising a question about the writer what else are we doing but making inquiry about the pen as we read the epistle?

But Gregory did not leave the matter there. He proceeded to say that, among the options concerning the human author, we may with the greater probability suppose that it was written by Job173. It seems reasonable to assume that the same blessed Job who bore the strife of the spiritual conflict also recorded the circumstances of his eventual victory. The author’s status as a gentile is then assessed, Job being identified as a ‘virtuous heathen’ or ‘good pagan’174. ‘Be thou ashamed, O Zidon, for the sea has spoken’ (Isaiah xxiii.4) is interpreted to mean that Christians should be shamed by the spiritual feats of those gentiles who, knowing less about God than we do, yet managed to achieve more than we have.

The impressive balance of this analysis by Gregory, in which both the divine auctor and the human auctor of Scripture are given their due, may be directly related to the principles of exegesis outlined in the dedicatory letter to the Moralia in Job. There Gregory explained that, while sometimes Job’s words cannot be understood literally, there are times when anyone who fails to understand the text in its literal sense hides the light of truth that has been offered to him175. For example, Job xxxi. 16–20 records Job’s acts of generosity to the poor: if we forcibly twist such a passage into an allegorical sense, we make all these deeds of mercy to be as nothing.

It is precisely this balance which was lost in much twelfth-century exegesis, where the commentators were preoccupied with allegorical interpretation. According to Geoffrey of Auxerre (fl. late twelfth century), it is not important to know who wrote the Song of Songs176. Perhaps the human auctor knew what he was prophesying but, if he did not, the inspirer (inspirator) most certainly knew. What matters is the prophecy itself, of the mystical marriage of Christ and holy Church177. This point of view was persistent and pervasive; we find it being reiterated by Giles of Rome (Bachelor of Theology 1276; † 1316) in the prologue to his commentary on the Song of Songs178. However, by the time of Giles, the climate of opinion had changed somewhat: he was able to share both Gregory’s metaphor (of the pen) and the balance of the saint’s analysis of authorship. It may seem superstitious, Giles says, to inquire about the ‘instrumental causes’ or human writers of Scripture. On the other hand, if the writer of the Song of Songs is sought, we may say that it was Solomon.

The Bridegroom who is the true God, that is the subject or material of sacred doctrine, is also principally the efficient cause of this science. The instrumental cause is not of concern to us, since causes of this type function as instruments with respect to doctrine . . . Just as it would be superstitious, when inquiry is made concerning the author of a certain work, to ask with what type of pen the work was written, so after a fashion it seems superstitious that someone should be very solicitous to seek the instrumental causes of sacred Scripture: for if it takes its origin from truth, in that the work is from the Holy Spirit, great care is not to be exercised in finding another author. But if, on the other hand, it seems that care should be exercised in this, we can say that Solomon was such a cause of this work . . .179

This discussion occurs within an elaborate ‘Aristotelian prologue’ in which both the role of the human auctor and the literary form of his work are described with care and precision.

In subsequent chapters, it will be demonstrated how different types of academic prologue were associated with different attitudes to authorial role and literary form. As used by twelfth-century exegetes, the ‘type C’ prologue was mainly concerned with the auctor as a source of auctoritas. The auctoritas of the various books of the Bible was established through elaborate allegorical interpretation which tended to undervalue the literal sense of Scripture and the literary forms, genres, styles and structures believed to constitute part of it. But in the early thirteenth century, when emphasis came to be placed on the literal sense of the Scripture, the exegetes’ interest in their texts became more literary180. In the ‘Aristotelian prologue’, the emphasis had shifted from the divine auctor to the human auctor of Scripture. As Miss Smalley puts it,

The scheme [of the four causes] had the advantage of focusing attention on the author of the book and on the reasons which impelled him to write. The book ceased to be a mosaic of mysteries and was seen as the product of a human, although divinely inspired, intelligence instead. The four causes were still an external pattern, which might be imposed on wholly unsuitable material . . . but they brought the commentator considerably closer to his authors.181

Because of this change of attitude, the unquestionable fact of the divine inspiration of the Bible no longer interfered with thorough examination of the literary qualities of a text. Scholars paid more attention to the instrumental causes whom God had honoured. The theory of efficient causality enabled the human auctores of Scripture to acquire a new dignity; the theory of formal causality provided the rationale for meticulous analysis of form both as style and as structure. Chapter 3 treats of the former theory, and Chapter 4 of the latter.

Thus far we have defined the crucial concepts of auctor and auctoritas and outlined the categories and attitudes which formed the basis of medieval theory of authorship. Summary description of the main types of academic prologue which introduced commentaries on auctores has been the essential preliminary to the detailed examination, carried out in the following chapters, of the literary theory conveyed by these prologues. The auctores, it would seem, were expected to perform certain ‘offices’ and to employ certain styles and structures in their writing. The most authoritative of all the authors, the inspired writers of Scripture, were credited with the most elaborate authorial roles and literary forms, and medieval expositions of these provide us with some of the most elaborate literary theory produced in the period. We shall, therefore, give the Scriptural exegetes our full attention henceforth, beginning with an assessment of the felicities and limitations of twelfth-century prologues to Bible-commentaries as vehicles for the advancement of literary theory.