Any technology that reproduces sound has at least two elements: a source and a destination. Often one or more additional intermediate elements are between the source and destination, such as a preamplifier that boosts volume level or an analog-to-digital or digital-to-analog converter, but you'll always have a program source and a destination device that converts the signal back to sound.

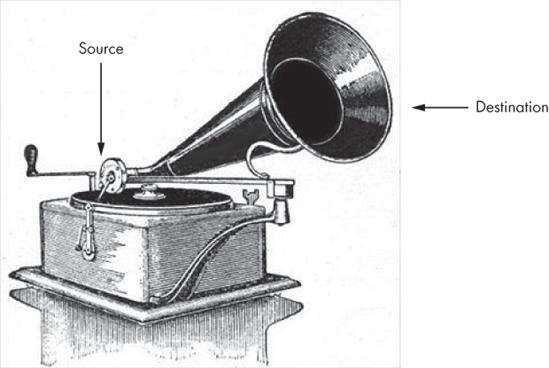

For example, consider an antique gramophone like the one shown in Figure 15-2. The source of the sound is a needle that follows the vibrations in a grooved disk, and the destination is a membrane that reproduces those vibrations through a horn.

In a modern music system, the program source can include the following:

Figure 15-2. The source of the music played on this gramophone is the needle on a grooved shellac disc; the destination is the horn.

The destination can be any of the following:

Speakers connected to a home stereo system, TV receiver, or surround sound system

Speakers connected to a computer or built into a laptop

Headphones or a docking unit's speakers connected to a portable device such as an iPod

A storage device such as a hard drive or a flash drive

A tabletop or portable boom box or Internet radio

A home network can connect any of these sources to any destination. It might be necessary to convert the source from analog to digital format before it moves through the network, and you might have to convert the digital data back to analog before you play the sound through a speaker or headphones, but these are relatively minor technical details; the important point is the same network that handles other data can also distribute digital audio files. In networking terms, you can think of the devices that handle program sources as servers and the destinations as clients.

An audio server in a home network stores music, radio programs, and other sound files that are accessible to other devices on the same network. The server can be a computer that you also use as a workstation, a server for other data files, a dedicated server for audio files, or a component in a stereo or home theater system. Regardless of their physical form, most audio servers perform these functions:

They convert (or rip) audio tracks from CDs and other sources to one or more standard file formats.

They store sound files on a hard drive.

They distribute sound files on demand to one or more players.

They distribute audio to the network directly from a CD, DVD, the Internet, or some other digital source.

Like any other server, a music server should have a relatively large hard drive with enough space to hold all the individual music files you want to store on it. General-purpose computers and stereo-component music servers can both perform similar services; each type has a different combination of cost, ease of use, and sound quality.

When you use a standard desktop or tower computer as your music server, you can use the same computer to serve other types of data. You can use free or inexpensive software such as Windows Media Player, RealPlayer, Sound Forge Audio Studio, Exact Audio Copy, or Audacity to create or convert files to your standard storage format, and you can increase the server's storage capacity by installing one or more additional hard drives.

The sound quality of the most common sound cards (and built-in sound processing on many motherboards) is adequate for casual listening. However, the quality is not as good as an "audiophile" or "studio quality" sound card or external interface unit that adds less background noise and distortion to your files. If you're creating your own files from CDs or uncompressed digital program sources, you will probably want to upgrade your sound card from the "Sound Blaster" interface supplied with your computer. On the other hand, if you get all your music by downloading MP3 files from iTunes or one of the other online services, or if you convert your music from CDs, LPs, or other sources to highly compressed MP3 files, you won't notice the difference.

The choice of operating system—Windows, Macintosh, or Linux—is a matter of personal preference; all three can work as music servers. If you're already using Windows Home Server to control your home network and share other files, the same server can stream audio (and video) to other network computers.

Microsoft's Windows Media Center, included in some versions of Windows Vista and available as a separate add-in product, is primarily a media player, but when you connect it to a device that has the Media Center Extender technology in place, you can use the Media Center computer to serve audio and video files to other computers, game consoles, and televisions.

For mixed networks, XMBC Media Center (http://xmbc.org/) is an excellent choice for managing and sharing media files.

Remember to configure the folder or drive that contains the server's music files as a shared resource that is accessible to other computers and devices on the same network.

Audiophile music servers store music and other audio files on a hard drive, and they generally perform two kinds of playback: They connect directly to a stereo or home theater system as a local program source, and they also connect to an Ethernet or Wi-Fi network to serve music files to computers and audio devices in other rooms.

Music servers sold as audiophile equipment generally contain high-quality internal parts and, often, front panel text displays that provide information about the music track currently playing. Many of them, such as the McIntosh MS750, are also very expensive. Most include their own CD drives for ripping copies to the internal hard drive and analog inputs with excellent analog-to-digital converters for making digital copies of LPs and other analog source material.

A music server is an expensive alternative to a computer with a very good internal or external audio interface card or adapter, but in a serious audiophile sound system, such a server has its place; a $3,500 music server might make sense as part of a system that includes a $3,000 amplifier and a pair of $7,500 speakers. But the rest of us can accomplish the same thing for considerably less money if we're willing to use a computer instead.

Digital music players convert sound and music files in common formats to analog sounds that you can play through headphones or speakers. Some of these formats use compressed audio that squeezes the data into smaller files. Others use larger uncompressed files that maintain all the original details. The most common format for compressed audio files is MP3. The most widely used formats for uncompressed files include WAV and AIFF. Table 15-1 lists the formats that you're most likely to see.

The choice of format is a trade-off between the size of the file and the quality of the sound. As a rule of thumb, sound quality increases with file size, as measured in bits per second. A WAV file of a music track might require eight to ten times as much storage space as an MP3 file of the same recording, but the WAV file is almost always a more accurate copy of the original. The compressed MP3 file occupies less space on a hard drive and can travel across the network more quickly, but the added bits in the WAV file will mean that the music has less distortion and better frequency response (the range between the lowest bass notes and the highest treble tones). In other words, an MP3 file might sound like the recording played through an AM radio, whereas the same music played from a WAV file could sound at least as good as a very good CD player.

Table 15-1. Common Audio File Formats

MP3 files are entirely adequate for casual listening, especially for speech, but uncompressed files can sound a lot better. The compromise between file size and sound quality is particularly important when you are loading files on an iPod or other portable device with a limited amount of storage space. For a home system, where you have little or no practical limit to the amount of storage space (you can almost always add another hard drive to the server), storing your music files in an uncompressed format, especially if you plan to listen through a good quality stereo or surround sound system, is best.

Note

It's important to store archival copies of original recordings as uncompressed files, so future users will have the best possible recordings to work with. Many libraries and archives keep a high-quality WAV file as a master copy and a separate MP3 listening copy for distribution. Archiving uncompressed files is less important when you're dealing with commercially available CDs because hundreds or thousands (if not millions) of other copies are probably in circulation, but when you have the only copy, archiving an uncompressed version can make a difference.

Many audio player programs can automatically recognize and load most common file formats. However, you might want to install more than one program, just in case your default player can't handle a file. For example, Windows Media Player won't accept very high bit rate (24-bit/96 kHz per second) WAV files, so you'll have to play them in another program, such as Audacity or Sound Forge.

If you want to distribute music and other recordings from LPs and other analog media (such as cassettes, old 78 rpm discs, and reel-to-reel tape) through your network, you must convert them to digital audio files first. This conversion is more time-consuming than ripping CDs, but it can be rewarding if you have some great old records that are not available in any other format.

If you plan to transfer a lot of analog media to digital files, it's worth the extra cost to use a better analog-to-digital converter than the one built into your computer. Professional studio-quality converters can cost hundreds or thousands of dollars, but less expensive devices such as the ones made by E-Mu, M-Audio, and Edirol, among others, will give you considerably better performance than consumer-grade sound interfaces.

Remember that the sound of your digital copy won't be any better than the sound coming from the analog original. Before you make a copy, be sure to clean the dust and grit from your LP, and make sure the needle on your record player is in good condition. Use alcohol or some other head cleaner to remove the gunk from the face of the heads before you try to play cassettes or reel-to-reel tapes.

In a home network, the other half of a music distribution system is a music client or audio client. The client can be a program running on one or more of the household computers, a stereo component, a surround sound or home theater system, or a tabletop "boom box" or Internet radio. The client receives music files from a server or streaming audio program through the Internet and plays them through a set of headphones or speakers.

The quality of sound played through a network depends on several factors: the quality of the original recording, the amount of network traffic, and the quality of the client's digital-to-analog converter and speakers. For example, if you're playing a music track that originated on a noisy cassette tape through the tiny and tinny speakers in your laptop computer, the music will sound much worse than a track ripped from a CD and played through a good stereo amplifier and high-fidelity speakers. And if the network that connects the server to the client is already running close to its capacity, or if it's using a noisy Wi-Fi link, you might hear repeated drop-outs in the music when the client can't convert data packets to a continuous audio stream.

A computer used as a music client must have an internal or external audio interface, such as a sound card, an interface on the computer's motherboard, or an interface connected to the computer through a USB or FireWire port. To play a music file, open the file in an audio player program that supports the file's format, just as you would open any other kind of file. The audio output for the computer's audio interface should connect through an audio cable to a set of powered computer speakers or a full-scale stereo or home theater system.

If you're using the computer exclusively as a music client, you don't need the latest and most powerful processor or a large-screen monitor. Anything that can connect to the network and support a decent audio interface unit should be entirely adequate. If you have an older laptop that you're no longer using for other purposes, try using it as a music client; the laptop is probably more compact than a desktop unit and it might work just as well if you plug a decent audio interface into the USB port.

Most computers look like, well . . . like computers. If your stereo system is located on a bookshelf or behind glass cabinet doors in your living room, you might prefer to use a music server that matches your other stereo components. If you don't mind assembling a computer out of parts, look for computer cases (such as the Antec case shown in Figure 15-3) that look like stereo equipment. But remember that you'll still need some kind of keyboard, mouse, and monitor. On the other hand, it's often easy enough to place the computer case out of sight on the floor or in some other out-of-the-way location or to run the server through the network from another room.

Photo courtesy of Antec

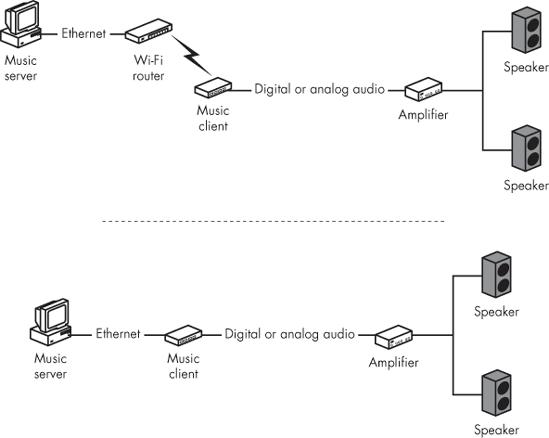

If you don't have a spare computer, you can also run audio cables between your stereo and a nearby computer that you're using for other purposes. For example, if you have both a desktop computer and a stereo system in your home office or study, you can use that computer to feed the existing speakers through the stereo's amplifier. Even if the stereo is in another room, running audio cables through the wall or under the floor might be more practical. Figure 15-4 shows a typical system connection.

To play music from your music server, set the input selector on the stereo to the Auxiliary input (or whichever input you have connected to the computer), and use the computer's mouse and monitor to select the song or other music file you want to hear. If your computer or sound card has digital outputs (either optical or copper) and the stereo has digital inputs, use a digital cable to transfer the audio. The computer should automatically open the music file in a compatible player and feed it to the stereo.

Figure 15-4. A music server can connect to a client through either a Wi-Fi link or an Ethernet cable. The client sends audio to an amplifier's analog or digital auxiliary input.

As an alternative to using a computer, consider using a separate device specifically designed as a music client or network music player. The client device sends an instruction to find and play a specific music file (or other audio track) to the music server, which streams the requested file back to the player. The player can either send the digital stream to a converter in the audio system or convert the file to an analog signal and send the music signal to the audio system.

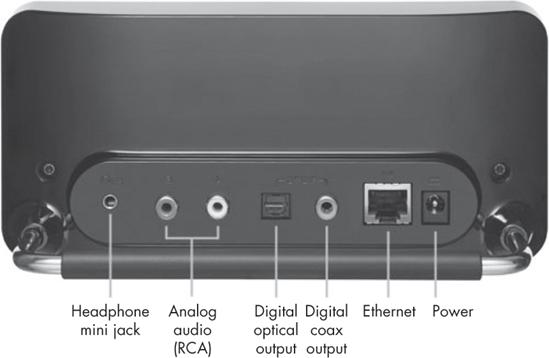

For example, Slim Devices makes a family of Squeezebox music clients, including the Squeezebox Classic, Squeezebox Receiver, and Squeezebox Transporter. Figure 15-5 shows the connections on a Squeezebox for a network and a stereo system. Similar products are available from Roku, Netgear, Philips, and other companies. Most of these devices are marketed as audio components, so the best place to look for a demonstration is probably a home audio retailer rather than a computer store.

Each music client manufacturer supports a different set of audio file formats; they all work with the most widely used formats, but if your library includes more obscure formats, you should confirm that a client can recognize them.

Network music players offer several benefits: They occupy less space than a computer; they're often easier to use; and they can provide sound quality as good as or better than a computer for less money. If you're buying new equipment to play music through your network, a dedicated music player can be an excellent choice; but if you already have a spare computer, you can probably accomplish the same thing without buying any new equipment (although replacing the computer's audio interface might improve the system's performance).

Figure 15-5. Slim Devices' Squeezebox connects a music server to a home audio system through an Ethernet or Wi-Fi network.

It's not necessary to use a computer or a full-scale stereo or surround sound system just to listen to music from a music server or streaming radio stations and music channels through the Internet. You can find a whole category of tabletop "Internet radios" that combine the music client and speaker in a single box (sometimes with satellite speakers for stereo). In spite of the name, most Internet radios can also play music files stored on your own music server. Some also include AM and FM radios, so you can use the same device to listen to local broadcast stations.

An Internet radio works like any other network music client: It connects to your home network through an Internet port or a built-in Wi-Fi port and allows you to select files from your own server or streaming programs through the Internet. Ultimately, these devices will be as easy to use as the tabletop radio in your bedroom or kitchen; simply turn the device on, select the station, and listen. The important difference is that you're not limited to the programs on local radio stations; you can choose from thousands of radio stations and streaming music services that offer a huge variety of music, news, and other programming—many of them without commercials.

Today, Internet radios are still expensive novelties—most cost $200 or more—but if and when the price comes down, they will probably become a hugely popular alternative to radios that only receive local stations.