Video—in the form of movies, television shows, home videos, or files downloaded through the Internet—is yet another type of program material that you can distribute through your network. You can view videos on your computer's monitor or through an adapter on a television screen.

Video distribution through a network follows a similar structure to audio: Video files are stored on a server and transmitted to a client on demand. However, video files contain many more bits per minute of content than audio files, so the network must have a high enough capacity to handle that additional demand. In practice, this means that many Wi-Fi links (except the newest 802.11n equipment) may not be able to keep up with a video stream, and even a wired 100-BaseT network might overload if you try to push through more than one video stream at the same time.

When you want to download a movie or some other large video file through the Internet, it's often better to save the file to your computer's hard drive, rather than trying to view it as the computer receives it because the download speed is often too slow for the video player program to assemble the digital packets and display them as a continuous stream. On the other hand, when all the bits are already on a DVD or hard drive, the video player can play the stream without the need to wait for more bits to arrive.

You can think of the stream of incoming bits as a garden hose that fills a watering pail with a slow trickle of water; if you pour out water more quickly than the hose fills the pail, you must refill the pail before you can pour more water. The same thing applies to video files through a network: If the data packets that contain the video stream enter your network more slowly than the video player assembles and displays them, the player's buffer will run out of bits and stop displaying anything until it receives more.

A video server is a network server that stores movies and other video files and sends them through the network to video player programs on client computers or video players. Most video servers can also store and distribute music files. Some computer operating systems, such as Windows Home Server and its associated client programs, include software that has been optimized for video distribution, but you can also use a general-purpose Linux, Unix, Macintosh, or Windows server, as long as the server computer contains one or more relatively large hard drives with enough available space to hold very large video files.

Other media servers combine the function of a network server and a local media player into a single package. You can play music and videos through a screen and speakers connected directly to the media server or send requests to the server from other players through your network.

The primary function of a digital video recorder (DVR) is to record incoming broadcast or cable television programs for delayed viewing. However, some DVRs, including TiVo, the most popular DVR in North America and Australia, can also distribute programs to another DVR through a network. By connecting a TiVo to a network, you can also download program schedules through the Internet rather than a slower dial-up telephone connection.

Most recent TiVo models, including the Series2 Dual Tuner and Series3 HD DVRs, have an Ethernet port as standard equipment. The older Series2 Single Tuner DVR requires an optional Ethernet network adapter that connects to the DVR's USB port. For a wireless connection, you must use a TiVo Wireless adapter, which is an optional accessory that connects to the DVR's USB port, or a compatible adapter made by Belkin, D-Link, Linksys, or Netgear.

To connect a TiVo to your existing wired network, follow these steps:

Run an Ethernet cable from the DVR to a network hub or router.

Press the TiVo button on the DVR and select Messages and Settings ▸ Settings ▸ Phone & Network.

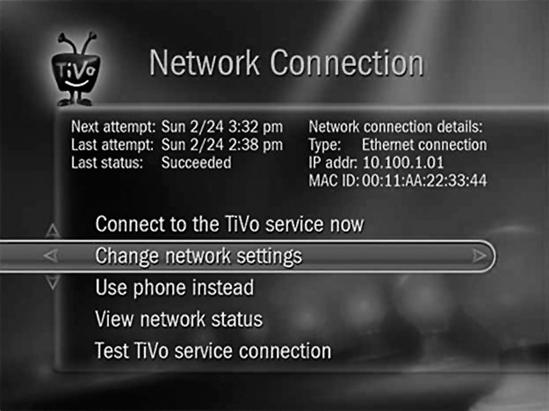

From the Network Connection screen shown in Figure 15-6, select the Change network settings option.

Figure 15-6. Use TiVo's Network Connection screen to configure a wired connection to your home network.

Follow the instructions that appear on your screen. If your network has an active DHCP server, the TiVo client will detect it automatically and display a Network Setup Complete screen. If your network doesn't have a DHCP server, select No, let me specify a static IP address, and type an IP address for this network node, the subnet mask, and numeric addresses for the node's gateway router and DNS server.

The DVR will test the connection. If the settings are correct, it will display a Network Setup Complete screen.

To connect a TiVo DVR to your network through a Wi-Fi link, follow these steps:

Press the TiVo button on your DVR. The TiVo Central screen will appear.

Select Messages and Settings ▸ Settings ▸ Phone & Network.

If your TiVo is already connected to a telephone line, select Use network instead. If it's connected to a wired network, select Change network settings. Press Select.

If the wireless adapter is not already connected, connect it now. When the TiVo identifies the wireless adapter, it will display the Network Adapter Detected screen.

Press Select. The Wireless Network Name screen will appear.

Either select the name of your Wi-Fi network and press Select or, if the network does not broadcast the network's name, select Enter network name and follow the instructions on your screen.

TiVo will ask for your network password. Use the keypad on your screen to type your WEP or WPA password and then click Done Entering Network Password.

If the password is correct and your network uses a DHCP server, the Network Setup Complete screen will appear. If the network doesn't use DHCP, you will see a series of configuration screens. Type the IP address, subnet mask, and the addresses for your network's gateway router and DNS server.

To watch a program that has been stored on a TiVo from a second DVR in another room, follow these steps:

Turn on both TVs and go to the destination player's Now Playing List. The other DVR will appear at the bottom of the list of available programs.

Highlight the name of the distant DVR and press Select. That DVR's Now Playing List will appear.

Choose the name of the show you want to transfer to this DVR and press Select. The Getting Program screen will appear.

To watch the show while you're transferring it, select Start playing on the Getting Program screen. When the transfer is complete, the name of the show will appear in this DVR's Now Playing List.

Several of the same programs that play music on a computer can also handle video files. Windows Media Player, RealPlayer, and QuickTime include both audio and video decoders. Others such as VideoLAN (http://www.videolan.org/) and MPlayer are optimized for video. Like other networked files, you can use a player program on a client computer to view a video file from a server. In most cases, one or more video player programs automatically take control of specific file types, so almost all video files will automatically load into an appropriate player when you select a file from an onscreen directory or file folder.

In rooms where you have a television set but no computer, it's often possible to use a game console or other adapter to view movies and other digital video files on the TV screen. In rooms with both a computer and a large-screen TV, it's often worth the trouble to connect the TV directly to the computer as a complement to the smaller computer monitor. The quality of pictures and text on a TV screen is not always as sharp as the same images on a computer monitor, an image from a broadcast or cable TV signal, or a DVD player, but with a bit of tweaking, it can be good enough to watch.

To connect a TV directly to a computer, you need two things:

An output signal from the computer that's compatible with an input to the television

Driver software for the computer's video controller

Your television has one or more of these input types:

Two or more screw terminals that connect to a flat antenna cable

A threaded socket that mates with a coaxial cable from an antenna, cable TV service, or other program source—the socket and mating plug at the end of the cable are called F connectors

A circular connector with either four or seven sockets that mates with a matching multipin plug called an S Video (for Super Video or Separated Video) plug

Three color-coded sockets (yellow for video, white for stereo audio left or mono, and red for stereo audio right) for analog audio-video cables—these are similar to the RCA phono plugs and sockets used in most home stereo systems

A 15-pin analog VGA connector like the one used by older computer display monitors

A rectangular multipin digital input known as a digital visual interface (DVI) connector

A 19-pin or 29-pin digital socket known as a High Definition Multimedia Interface (HDMI) connector

The easiest way to feed a signal to your TV from the computer is to find a video controller for your computer that has outputs that match your TV's inputs, but that's not always possible. For example, you won't find a video controller that can directly feed an old analog TV with nothing but an F connector as signal input (or an even older set with screw terminals). The alternative is to use some kind of adapter—a special cable with different cables on each end—or a converter that changes the output signal from the computer to a signal compatible with the TV's input. For best quality with an HDTV screen, use either a DVI-to-DVI cable or a DVI-to-HDMI cable or adapter, depending on the TV's inputs. Look for an adapter or converter at an electronics retailer.

Driver software for video controllers can come from several possible sources: bundled with your computer's operating system or supplied by the maker of the video controller or the controller's chipset or with a video converter. The control program for each driver package is different, so you'll have to follow the printed or onscreen instructions when you install the software.

Putting aside the issues related to converting between analog and digital video, it would seem that there isn't a lot of difference between a TV screen and a computer monitor. But they use different methods to accomplish the same objective, and these methods create problems when you try to move from one to the other. The difficulty arises because of the way computer monitors and TV screens break an image into scan lines and pixels. For the purpose of this explanation, we can think about a still picture, but the same problems can also occur in a moving image.

In North America, an analog TV shows images as a sequence of 535 scan lines from left to right across the face of the screen; when the TV reaches the end of one scan line, it moves down to the next one. In digital TV, the screen is divided into a large number of dots called picture elements, or pixels. The method used by the TV to light up segments of scan lines or pixels is different on picture tubes and flat panels, but the number of scan lines or pixels is specified by industry standards. The size of the screen doesn't matter; the number of scan lines or pixels on a screen is always the same (there are several different standards for flat panels, depending on size and cost, but the number of pixels is constant for each standard).

Computer monitors also use pixels, but the number of pixels in an image is different, depending on screen resolution. When you change your monitor's resolution from, say, 800 × 600 pixels to 1280 × 1024 pixels, the computer adjusts the number of pixels within a 1-inch (2.5 cm) square space on the screen or any other image area.

To show a computer image on a TV screen, the controller must adjust the number of scan lines or pixels to fit the area available on the monitor. If the TV screen expects more scan lines or pixels than the incoming signal, the controller will duplicate occasional lines or pixels or it will create a new line that is a blend of the one above and the one below. If the computer sends too many scan lines or pixels, the screen will skip some of them. This process is called video scaling.

Video scaling has two effects: It forces the video controller to work hard to change the size (and sometimes the shape) of the image, which can slow down performance, and it sends an image to the TV screen that can suffer from smeared colors, looser focus, jagged edges, and distorted pictures. A good controller can make adjustments that minimize these problems, but don't be surprised if the image your computer displays on a TV screen (even a very good high-definition TV screen) is not as sharp as the same image on a computer monitor; a good DVI-to-HDMI image on an HDTV can be sharper than a VGA display when everything works together correctly, but a mismatched system can be considerably less impressive.