Although Lucy Marsden had been reluctant to leave Exeter, Great Malvern had its compensations. The 36-year-old was pregnant with her seventh child, and as the town was within a few miles of Cheltenham she was able to call on the support of her mother and sisters, as well as her mother-in-law, Harriet Marsden. Perhaps Lucy felt she could make a new start here, sheltered below the Malvern Hills with her children around her as she waited to give birth. In Radclyffe Hall’s novel The Well of Loneliness, the pregnant Lady Anna Gordon looked across to those same hills, taking comfort in their beauty: ‘From her favourite seat underneath an old cedar, she would see these Malvern Hills in their beauty…their swelling slopes seemed to hold new meaning. They were like pregnant women, full-bosomed, courageous, great green-girdled mothers of splendid sons.’1

First on the left – No. 21 Lansdowne Terrace, Cheltenham; home of the young Marsdens’ Granny Rashdall and their doting maternal aunts

The young Marsdens were able to establish close relationships with their aunts and grandmothers at Cheltenham, spending time with Harriet Marsden at Claremont Cottage and at Granny Rashdall’s impressive five-storey home at No. 21 Lansdowne Terrace. While under construction in 1838, the terraces were described as being ‘…unrivalled for elegance of exterior by any similar row of private houses in the kingdom’.2 Built of glowing Cotswold stone, their first-floor balconies were flanked by twin pairs of Ionic columns. Today, Lansdowne Terrace is cherished as part of Cheltenham’s rich architectural heritage.

Today, Cotswold House in Worcester Road, Great Malvern, is externally unchanged but it has reverted to its original name of Abberley House

At Great Malvern, Dr Marsden moved his family into one-half of a substantial four-storey Georgian property on the Worcester Road called Abberley House. It was located a few minutes’ walk from the town centre and owned by the local Candler family: William Candler, who lived at nearby Malvern Link, and his three unmarried sisters. The Misses Candler continued to live in one side of the divided property. To avoid confusion, Dr Marsden renamed his section Cotswold House. From the rear, the property enjoyed a spectacular view overlooking the Severn Valley. A terraced lawn provided a safe playing area for the children.

The timing of Dr Marsden’s move to Malvern was perfect. His partner James Gully’s best-selling book had come to be regarded as the ‘bible’ of hydropathy and was attracting a large clientele. Gully had also begun co-editing a journal on the cold water cure and Dr Marsden contributed to its first issue with an essay on his pilgrimage to Graefenberg. He promised a second instalment would appear in the following issue, but owing to a family tragedy the piece would never be written.

On 23 June 1847 Lucy Marsden haemorrhaged after giving birth to a stillborn baby. For the children, hushed and anxious voices brought a frightening awareness that something terrible was happening to their mother. Dr Marsden had witnessed the treatment of a similar case at the homeopathic hospital in Vienna: ‘A woman had been given up as lost for haemorrhage. A few drops of the millionth part of aconite, of ipecacuanha, of china, of secale carnatum, of nux vomita and pulsatilla, given each at a time in due succession, stopped completely the uterine bleeding, and these medicines given in the course of treatment completely restored her.’3 If Lucy Marsden received the same potion, then the outcome was very different. Maria Hayne, the children’s governess, sat by her mistress over the next nine hours as she slowly bled to death.

Coincidentally, one of Dr Marsden’s fellow water-cure physicians would compose a touching but bitter epitaph for Lucy and so many women like her. Mary Gove Nichols was then living in America, but would later set up a water-cure practice in Malvern with her husband. In 1854 she wrote:

Our graveyards are filled with the corpses of women who have died at from thirty to thirty-five years of age, victims of the marriage institution. The children are, from the laws of heredity descent, ill-tempered, sick, and often short-lived. The cares, the responsibilities, the monotony, the perpetual struggle between inclination and duty, make life a burthen and death a welcome relief.4

Even the happily married Queen Victoria lamented the lot of perennially pregnant young wives, as a letter to her daughter Vicky reveals: ‘…the poor woman is bodily and morally the husband’s slave. That always sticks in my throat. When I think of a merry, happy, free young girl – and look at the ailing aching state a young wife generally is doomed to – which you can’t deny is the penalty of marriage’.5

Lucy was buried in the churchyard of the Priory Church. Her heartbroken brother John Rashdall noted in his diary that Dr Gully and various other medical men attended the funeral. The emotional impact on the six young Marsdens must have been enormous. Their sense of security had been badly shaken during the long and painful separation from their mother beginning in 1844, and now they had lost her forever. The older girls, Lucy and Emily, became loving ‘little mothers’, especially to the baby of the family, Alice, who was yet to celebrate her second birthday.

Soon afterwards, during an epidemic of typhoid fever, James Jr and Marian fell ill and almost followed their mother to the grave. It was the prospect of losing his son and heir that had the greatest impact on Dr Marsden and he would later use his son’s recovery to enhance his professional reputation:

I have passed through the favourite ordeal – the greatest test by which faith can be tried…I have but one son. Eighteen months ago typhus fever broke out in the house. He was one of those who suffered from it…he recovered completely under homeopathy. No case could be more severe. It was one to test the utmost my confidence in our therapies. For a long and weary time I hoped against hope, and when his convalescence was assured, I could only, with a humbled yet thankful heart, acknowledge the goodness of the Healer, who had blessed the means for his recovery.6

Next door, the three middle-aged Candler sisters took a kindly interest in the motherless young Marsdens, as did the women’s yardman, Thomas Trehearn. Trehearn could be relied upon when the children needed someone to fix a toy or to supply materials for their playhouses. Meanwhile, Dr Marsden found distraction from grief and worry in his work. The water-cure was beginning to attract the most eminent and well-to-do members of Victorian society.

In September 1848 the poet Alfred Lord Tennyson placed himself under the care of James Gully. As Gully’s partner, Dr Marsden also had the opportunity of attending Tennyson. Writing from his mother’s house in St James Square in Cheltenham a few weeks earlier, the poet told Gully he had called to ask advice about a ‘hydropathical crisis’ on his arm, but on finding Gully out, ‘I showed it to Dr Marsden who likewise was ready to give me his advice gratis, so that really Malvern seemed to be the headquarters of all that is liberal & openhanded in your profession; & your heathen veneration for the poetical attribute comes out as a most practical Christian virtue.’7 As it happened, James Marsden was already acquainted with Alfred Tennyson, who was a close friend of the Reverend John Rashdall.

Other visitors to Malvern that autumn were Florence Nightingale and her mother Fanny, who both underwent treatment at Dr Gully’s establishment. In a letter to the poet Richard Monckton Milnes, Miss Nightingale wrote: ‘Your friend Tennyson was there, with a skin so tender he walked backwards whenever the wind was north or east and that was generally. He was sadly contumacious, smoking vile tobacco in [a] long pipe till Dr Gully told him it coarsened his imagination and made him write bad poetry.’ Florence Nightingale was an early witness to Gully’s magnetic appeal to women, despite the fact that he was short, plump and balding: ‘Mama was so taken in by him that I was obliged to tell him I had a father living.’8

In March 1849 the chronically unwell Charles Darwin arrived for treatment: ‘Having heard accidently of two persons who had received much benefit from the water-cure, I got Dr Gully’s book and made further enquiries, and at last started here, with wife, children, and all our servants…I feel certain that the water-cure is no quackery.’9 The family moved into a large house called The Lodge, located not far from Cotswold House in Worcester Road. It was owned by the elderly Miss Mary Hind, a good friend of Dr Marsden, who may well have recommended the property. Charles Darwin got along famously with Dr Gully and considered the water-cure so beneficial that the family’s intended stay of six weeks extended to four months. Darwin’s older children, William, George, Annie and Etty, were around the same age as the young Marsdens and they were soon in and out of each other’s houses and gardens, having great fun and no doubt trying the patience of their elders. Charles Darwin would return to Malvern in 1851 with two of his children, but unfortunately the outcome would not be so positive.

On 14 June 1849, while the Marsden children were still acting as unofficial hosts to the young Darwins, their father officially but amicably dissolved his partnership with Dr Gully.10 The growing popularity of the cold-water-cure had convinced Marsden to establish his own practice, combining hydropathy with homeopathy. Perhaps to humour his fervent young colleague, Dr Gully had also embraced homeopathy, although he would never be totally convinced of its efficacy. Nevertheless, both he and Dr Marsden would serve on the council of London’s first homeopathic hospital, which opened its doors at Golden Square, Soho, in April 1850. It was an indication of the pair’s continued close association.

Soon after Dr Marsden had gone his own way, the water-cure treatment at Malvern received some unwelcome publicity involving the son of Andrew Henderson, one of the bath attendants that Dr Marsden had worked with at Dr Gully’s establishment. In April 1850, 2-year-old James Henderson fell against a fireplace and, although it seemed he was only slightly injured, he developed a fever several days later. His family packed him with wet towels, a treatment continued by Dr Gully when he was belatedly called in. At the inquest, local surgeon William West commented pointedly that the water-cure treatment was unlikely to have provided the child with any relief.

With a large family and a full complement of household staff, space was at a premium for Dr Marsden at Cotswold House, particularly as he provided accommodation for favoured patients. It was a lucrative arrangement, with board and lodging charged separately to medical fees. In-house treatment also allowed doctors tighter control over their patients. Describing the purpose-built clinic of Dr James Wilson after a stay of three weeks, Bristol journalist Joseph Leech commented:

There was something in fact about the establishment, the order, its regularity, and the control exercised over the inmates, which might be said to partake equally of the boarding-house and the boarding-school, and under the mastering glance and preceptorial authority of Wilson and his assistants, grown-up and even grey-headed people, imperceptibly succumbed to the influence of the man and the place with a juvenile deference, which was almost puerile.11

One incidence of Dr Wilson exerting his authority entered the realms of Malvern folklore. The doctor spotted one of his patients, the eminent politician and author Sir Edward Bulwer-Lytton, walking along Church Street with a suspicious bulge under his coat. When challenged, an abashed Bulwer-Lytton admitted to having purchased a bag of tarts from the local baker. Hoping to escape a tongue lashing, he said he had been asked to buy them for a lady friend. Dr Wilson did not care who they were for, roaring, ‘Poison! Throw them down in the gutter at once, and have more respect for her inside!’12

Dr Marsden ran an equally tight ship at Cotswold House, and for his children the atmosphere was far more oppressive than for temporary, fee-paying clients. They were now sharing their home with invalids, and the old adage that children should be seen and not heard was magnified a thousand-fold. Disturbingly, Dr Marsden’s medical theories were beginning to affect all aspects of the youngsters’ lives. The restricted diet prescribed for patients was also enforced in the nursery. No doubt the doctor was influenced by the views of men like the American hydropathist Russell Thacher Trall, who called pastry an abomination, and plum cake indigestible trash. He described the Victorians’ beloved suet pudding as one of the most pernicious compounds ever invented. Trall would later publish The Water-cure Cook Book. It included a cheerless recipe for Snow-ball Puddings, in which peeled apples were packed in cooked rice then wrapped in cloths and boiled for another hour. Unhappily for the little Marsdens, ships biscuits and water crackers were among the few foods to receive Mr Trall’s blessing.

The children were also being subjected to strict intellectual control. On the subject of infant development, their father would write:

… the mind grows by what it feeds on – that impressions and images (and these include every kind of learning) are the food of the mind, is the reason of the importance that good thoughts and impressions should be received, whilst the mind is ductible, as in infancy and youth: channels of feeling and thought are then formed.13

It is interesting to note that while Charles Darwin agreed young minds were impressionable, he also recognized an attendant danger. In his book The Descent of Man, Darwin observed:

How so many absurd rules of conduct, as well as so many absurd religious beliefs, have originated, we do not know; nor how it is that they have become, in all quarters of the world, so deeply impressed on the minds of men; but it is worthy of remark that a belief deeply inculcated during the early years of life, while the brain is impressible, appears to acquire almost the nature of an instinct, and the very essence of an instinct is that it is followed independently of reason.14

Although Dr Marsden may have been well-intentioned, to impair a child’s independence of thought can prove fatal if he or she should fall under a malevolent outside influence.

The doctor had visions of producing six young models of physical and mental health, a glowing tribute to homeopathy and the perfect advertisement for his burgeoning water-cure practice. He was bitterly disappointed when the children failed to meet his expectations. Both his eldest child Lucy and young James Jr were struggling in the schoolroom. Lucy was barely literate and Marsden feared she might actually be slow-witted. Emily was bright and spirited, but her father considered her headstrong and wilful, setting a bad example for her siblings.

When he was not tending to his patients or upbraiding his offspring, Dr Marsden was busy completing a book on homeopathy that he had begun writing while in Exeter. It was published to coincide with the establishment of his new medical practice. In the preface he stated that it would soon be followed by a second volume, covering Malvern and the water-cure. The book was dedicated to the Reverend John Rashdall:

My dear Rashdall

I beg leave to dedicate these ‘Notes on Homeopathy’ to you, because we were living together when the circumstances and cases related took place, and because they tended to make you, as well as myself, a convert to the new practise. Dedications are made for patronage, for compliment, for esteem-sake. While I value friendship and kindness, you know I think every man is his own best patron. Compliments are out of the question; but I hope you will accept this, as a token of affectionate regard from your brother-in-law,

The Author

June 10 1849

Although Dr Marsden claimed the dedication had nothing to do with patronage, he was well aware that his brother-in-law’s long friendship with Alfred Tennyson could prove advantageous. A few well-chosen words from Rashdall might persuade the famous poet that his next experience of the water-cure should be at Cotswold House rather than at Dr Gully’s establishment.

Malvern’s water-doctors were now vying for prestigious clients and, as Joseph Leech noted with amusement, their efforts at self-promotion knew no bounds:

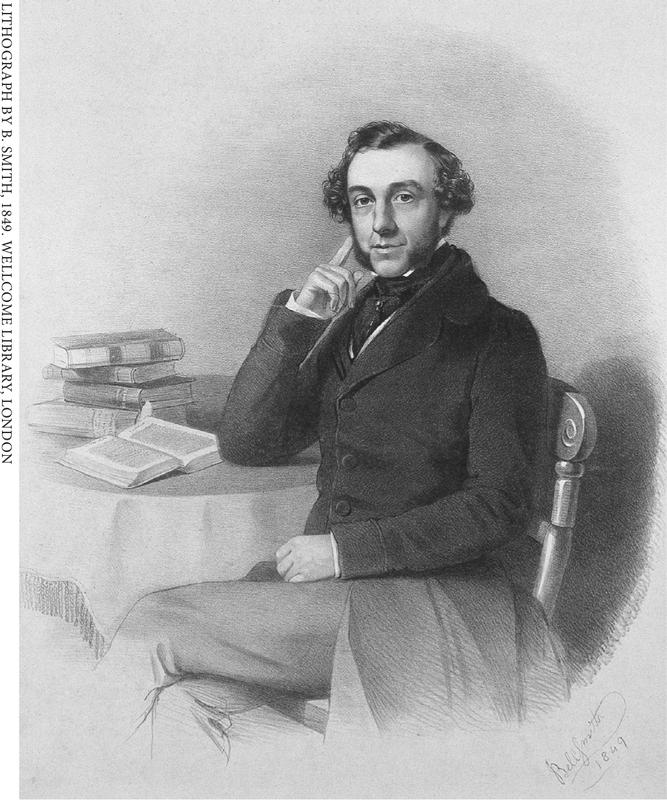

The three hydropathic doctors, who are more to Malvern than the three kings were to Brentford, have each had their portraits lithographed, and from the windows of the bookshop and the bazaar, and even from the walls of the inns, they seem to bid for the possession and management of the visitor’s body on his arrival. With whiskers silkily curled, sitting by a table, and severely musing, the ‘Great Original’, Wilson, seems intrepidly to assure the invalid and hypochondriac of a cure. Standing up with arms a-kimbo, pert and pragmatic Dr Gully appears to push himself forward and say, ‘I’m your man – try me’: while Marsden, who unites homoeopathy with hydrotherapy, may be said to have a mezzotint manner between both, and looks from his frame upon you as if he were listening to your case.15

The description of James Marsden’s portrait matches a lithograph by B. Smith (1849), now held in the library of London’s Wellcome Trust. Seated at his desk surrounded by textbooks, he appears entirely self-assured. He is immaculately turned out in cravat and wide-cuffed, cutaway-coat. His long side-whiskers may have been grown to compensate for a receding hairline.

Dr James Loftus Marsden established himself as one of Great Malvern’s successful water-cure doctors but his motherless children were repressed and unhappy

Dr Marsden knew that if he hoped to compete with the more prominent Gully and Wilson, he would require a much larger and grander establishment than Cotswold House. Although some clients were content to reside in Malvern’s boarding houses as out-patients, Dr Wilson had built a seventy-room spa hotel, complete with ballroom. Following their bland dinners of mutton, vegetables and copious amounts of water, his clients could enjoy music and even a little dancing before being ushered to their early beds.

Dr Gully was able to offer his clients luxurious accommodation at Tudor House in Wells Street, although he preferred to separate the sexes, explaining:

… it appears an arrangement of very doubtful propriety to place male and female patients in the same establishments. By means of the bath attendants (and the uneducated will babble) the infirmities of females are liable to become known to everybody with whom they sit at table…What would a parent or husband say to the presence of women of doubtful character in the same house with his wife or daughter?16

The male and female sections of Tudor House were connected by a elaborate, covered walkway. It was jokingly referred to as the ‘Bridge of Sighs’ and not only because of its resemblance to the famous seventeenth-century Ponte dei Sospire in Venice.

For some time, Dr Marsden had been purchasing parcels of land in Malvern from different vendors, finally consolidating them into a 5-acre site stretching from Abbey Road through to what is now College Road. But before he could begin drawing up plans for his state-of-the-art treatment centre, another quite different opportunity to enhance his social and professional standing arose.

Notes

1 Hall, Radclyffe, The Well of Loneliness (Jonathan Cape, 1928), p. 6.

2 Davies, H., Visitor’s Handbook for Cheltenham (Longman, 1840), p. 9.

3 Lee, Edwin, Homeopathy and Hydropathy Impartially Appreciated (Churchill, 1859), p. 68.

4 Nichols, Thomas Low, and Nichols, Mary Sargeant Gove, Marriage: Its History, Character, and Results (Nichols, New York, 1854).

5 Benson, A.C. and Esther, R.B.B. Viscount (eds), The Letters of Queen Victoria, vol. III (Murray, 1908)

6 Monthly Homeopathic Review, vol. 1, 1857, p. 291.

7 Lot 130A 3pp., 8vo, St James Square, Cheltenham, 2 August [c. 1845]. www.liveauctioners.com/item/2061540, date viewed 1 July 2010.

8 Bostridge, Mark, Florence Nightingale: The Woman and Her Legend (Viking, 2008), pp. 124, 125.

9 Darwin, Charles (ed. by Francis Darwin), The Life and Letters of Charles Darwin, vol. 1 (Murray, 1887), p. 373.

10 JRD, 14 June 1849.

11 Leech, Joseph, Three Weeks in Wet Sheets: Being the Diary and Doings of a Moist Visit to Malvern (Hamilton, Adam & Co., 1851), pp. 94–5.

12 Severn Burrow, C. F., A Little City Set on a Hill: the Story of Malvern (Priory Press, 1948), p. 73.

13 Marsden, James Loftus, The Action of the Mind on the Body (H.W. Lamb, 1859), p. 36.

14 Darwin, Charles, The Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex (Murray, 1871), pp. 99–100.

15 Leech, Joseph, Three Weeks in Wet Sheets: Being the Diary and Doings of a Moist Visit to Malvern (Hamilton, Adam & Co., 1851), p. 16.

16 Gully, James, The Water Cure in Chronic Disease (Churchill, 1846), p. 379.