Dr Marsden had been in sole practice for about twelve months when he discovered the living of the Priory Church was about to become vacant. Great Malvern’s wealthy water-cure patients filled the pews of the old church every Sunday and Marsden realized what a coup it would be if his brother-in-law John Rashdall became St Mary’s next vicar.

Achance to push this idea presented itself in the summer of 1850. On 24 June Dr Marsden stayed overnight with the Reverend John Rashdall after delivering his six children and their governess Adelaide Burnell to the minister’s home in London. Rashdall and his elderly mother had generously agreed to take the youngsters on holiday to Dunkerque, on the north coast of France. It was quite an undertaking and a measure of the Rashdall family’s affection for the children. The Victorians were indefatigable travellers but, as a contemporary guidebook warned, the small steamboats crossing the Channel were often uncomfortably overcrowded. In rough weather many passengers were soaked to the skin by rain or sea spray. Passengers, especially ladies, were warned to take ‘a small change of raiment in a hand bag’. Large swells could also make the twelve-hour journey a nightmare for those prone to seasickness. One remedy with echoes of the water-cure advocated swathing the body in bandages from thighs to neck, requiring an estimated twelve yards of linen. Fortunately for Rashdall, the young Marsdens proved to be good sailors, though apparently the same could not be said for poor Granny Rashdall.

The resort of Dunkerque was popular among English travellers for its twin benefits of fresh air and sea-bathing, but ironically all six children fell seriously ill, most likely from cholera. The bacterial infection was rife throughout Europe at the time and at its height during the summer months. Alice was the worst affected, and for a while it was feared she might not recover. It was early October before the children were well enough to return home. Such a frightening experience in unfamiliar surroundings strengthened Rashdall’s already strong bond with his nieces and nephew, but nevertheless he agonized over the suggestion of a move to Malvern, aware it would be a huge personal sacrifice.

Since leaving Exeter, Rashdall had thoroughly enjoyed his ministry at Eaton Chapel. He mixed with politicians and the fashionable clergy, and his connection with the poet Tennyson had led to other friendships within the literary world. He was regarded as a stimulating conversationalist and his sermons drew appreciative crowds. But James Marsden’s insistence that his children would benefit from avuncular affection and spiritual guidance left the minister in a moral dilemma. Was it selfish to want to stay in the capital? What would God want him to do?

John Rashdall was born on 19 December 1810. He grew up with a bad stammer, possibly an emotional reaction to the early death of his father. He was an intelligent child but the speech impediment, which he never fully overcame, persuaded his mother to have him educated at home rather than expose him to the rigours of public school. His friendship with Alfred Tennyson had begun during their shared childhood in country Lincolnshire. The boys were almost exactly the same age and their families were close neighbours. Tennyson’s father was the rector in the village of Somersby, 6 miles south of the Rashdall home at Spilsby. As young men they became contemporaries at Cambridge University, where Tennyson attended Trinity College and Rashdall Corpus Christi.

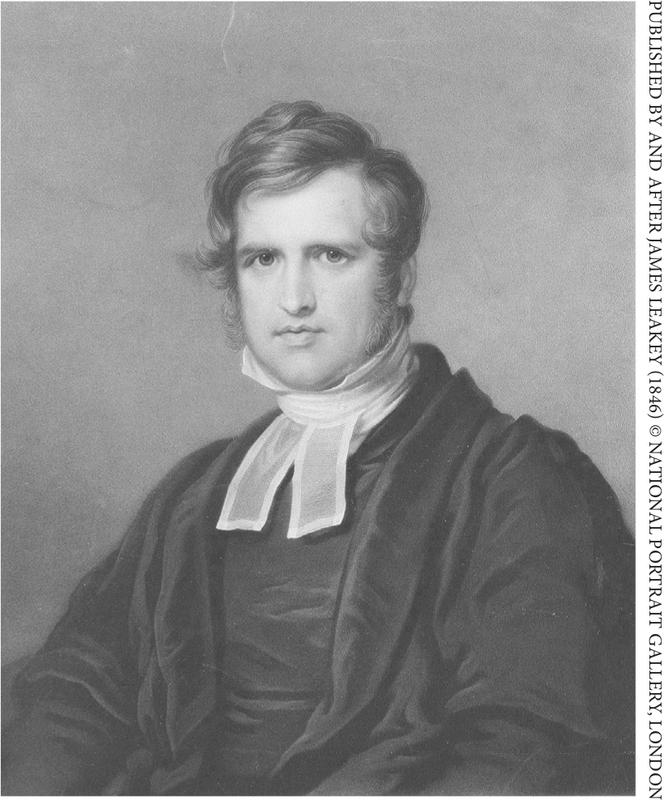

After obtaining his BA in 1833, Rashdall was ordained an Anglican minister by the Bishop of Lincoln. He served as curate at Orby in Lincolnshire and then at Cheltenham before being appointed incumbent of Exeter’s Bedford Chapel in 1840. As a passionate, evangelical preacher he preferred to address the chapel’s congregation without a written sermon. Like Dr Gully at Malvern, he was besieged by female admirers and reputedly accumulated a cupboardful of lovingly embroidered slippers. He developed a close friendship with the deeply religious Leakey family of Exeter. James Leakey (1775–1865) was an artist, and he painted Rashdall in clerical robes in 1846. A mezzotint of the portrait engraved by Samuel Cousins bears the inscription ‘To the Congregation of Bedford Chapel, Exeter. This Plate is respectfully dedicated by their obedient servant, James Leakey’.

The Reverend John Rashdall, circa 1846, depicted here by Samuel Cousins. Following his sister Lucy’s death in 1847 Rashdall maintained close bonds with his Marsden nieces and nephew

From the year of his ordination until his death, John Rashdall kept a journal, which he described as ‘a diary of the soul’. Its entries reveal a man whose inner life was so tortured by guilt and self-reproach that it is easy to imagine him donning a hair shirt, or flailing himself with a medieval scourge. He was forever striving to achieve a state of godliness but, at least in his own eyes, failing miserably: ‘I am now in the state of the most desperate sinner, only that my lot is the worse from a knowledge of the excellence of the state from which I have driven myself. Satan is fearfully successful against me.’1 Rashdall constantly wrestled with the twin sins of pride and ambition, triumphing over them only to accuse himself of taking pride in his humility. His constant self-analysis and spiritual angst were in direct contrast to the assured and forceful personality of Dr James Marsden.

The minister may have interpreted the children’s recovery at Dunkerque as a sign from above, although his ultimate decision to apply for the vacancy at Malvern no doubt had more to do with pleasing his brother-in-law than the Almighty.

When Rashdall returned from France an approach was made to Lady Emily Foley, Malvern’s Lady of the Manor and patroness of the Priory Church. By mid-August he had received her seal of approval. On 23 October 1850, he travelled to Worcester to see the Bishop and was officially granted the living of Great Malvern. The next day he preached at St Mary’s Priory Church for the first time, referring to the occasion as ‘a great day at Malvern’.

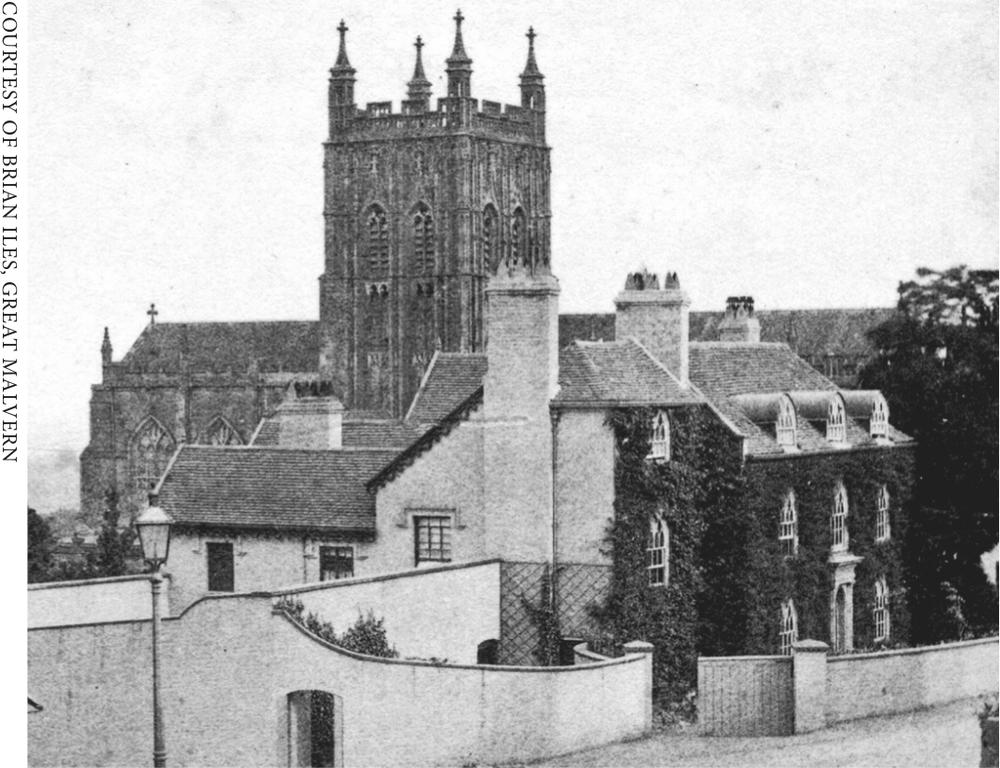

John Rashdall soon settled into St Mary’s vicarage, located close to the junction of Church Street and Abbey Road. It was an impressive, multi-chimneyed Georgian building, with dozens of lancet windows proclaiming its ecclesiastical connection. The young Marsdens would have been delighted to see more of their Uncle John. Despite constantly reminding them to pray and to be good children for God, he was a kindly figure, who had much more time for them than their busy father. On Guy Fawkes’s night in 1850, Rashdall’s diary records that his nephew and nieces took tea at the vicarage, staying overnight after watching the local firework display on Worcester Beacon, the highest point of the Malvern Hills.

With John Rashdall installed as vicar, the Priory Church became a more personal and familiar place to the children. One suspects they did not always behave as reverently as their uncle might have hoped. It is easy to imagine them running up and down the aisles, giggling over the strange carvings on the misericords and frightening little Alice with stories of mythical beasts. How they must have enjoyed the occasions when their uncle’s eccentrically grand patron attended Sunday service. The bells in the church’s battlemented tower rang out as Lady Foley arrived like royalty in a canary-yellow landau driven by four white horses. If her servants turned heads in their scarlet livery trimmed with gold lace, their mistress’s costume was just as spectacular. In a book on Malvern titled A Little City Set on a Hill (1948), author C.F. Severn Burrow mentioned that his father had been a church warden whose duty it was to escort Lady Foley to her reserved seat in the monks’ stalls. One outfit in particular made a deep impression on the warden: ‘A rich silk be-bustled gown with short train, and a bugled purple mantle surmounted by the most amazing bonnet covered with flowers and high ostrich tips with broad mauve strings tied to one side.’2

St Mary’s Vicarage, nestled under the tower of the Priory Church

Revealing an inflated sense of his own importance, the children’s father adopted a scaled-down version of Lady Foley’s equipage, riding around the township escorted by a uniformed manservant on a white horse. Presumably the servant carried Dr Marsden’s medical bag, allowing his master to cut a more elegant figure. The doctor habitually rode at full gallop, ‘as if intent upon overtaking the course of time that had gone too fast for his numerous engagements’.3 It is impossible to imagine him having the time or inclination to rein in his steed, scoop up one of his offspring, and deliver the child to Mr Need the confectioner for a treat of hydropathic gingerbread.

In April 1851 Charles Darwin made a return visit to Malvern, though not on account of his own chronic ill-health. His eldest daughter and special favourite Annie had been unwell for some time. Darwin’s suggestion that she may have shared his ‘wretched digestion’ was merely an attempt to quell his true fears about the seriousness of her condition. Annie was to be treated by Dr Gully, in whom Darwin had great faith. The patient was settled into Montreal House in Worcester Road, with her nurse Jessie Brodie, and later her governess, in attendance. Etty Darwin was taken along as company for her older sister. After the little girls had been on a shopping trip together, Etty wrote to her mother wistfully, ‘We saw the Marsdens’ playing in a garden.’4

Sadly, before the Darwin and Marsden children could properly renew their friendship, Annie’s condition deteriorated and Dr Gully wrote to Darwin, asking him to come. By the middle of the month she was beyond hope. Her father kept vigil at her bedside, sending heartbreaking reports to his wife Emma, who was in the final stages of pregnancy and unable to travel.

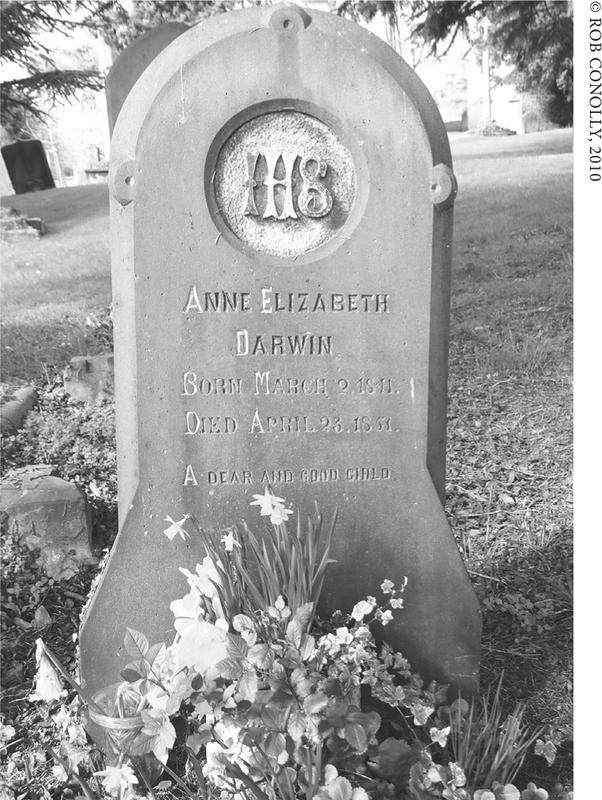

Annie died on 23 April. She was farewelled with great dignity. In keeping with the conventions of the time, there were paid mourners or ‘mutes’. Ostrich-plumed black horses drew the hearse to the Priory Church, where John Rashdall conducted the funeral service. The child’s aunt and uncle represented the family, her father being too grief-stricken to attend. Rashdall was a gifted preacher, but no words could have matched those Darwin himself would compose in memory of his daughter a few days later:

From whatever point I look back at her, the main feature in her disposition, which at once rises before me is her buoyant joyousness… Her whole mind was pure and transparent… We have lost the joy of the household and the solace of our old age: she must have known how we loved her; oh that she could know how deeply, how tenderly we do still and shall ever love her dear joyous face.5

Rashdall’s college friend Alfred Tennyson was also grieving. Three days earlier, on Easter Sunday, his wife Emily had given birth to their first child, a stillborn son: ‘My poor little boy got strangled in being born: I would not send the notice of my misfortune to the Times and I have had to write some 60 letters.’6

The death of Annie Darwin is a reminder that Malvern did not only attract bored, over-indulging hypochondriacs. Gravely ill people were brought to the town as a last resort, their families hoping against hope for a miraculous cure. In the midst of his humorous account of the ‘cure’, Joseph Leech commented on the many sad cases at watering-places. He noted that the most distressing sight of all was young people upon whom tuberculosis had left its ‘hectic and hopeless mark’. It is now believed Annie was consumptive, although Dr Gully described her illness as a typhoid-like fever. For Dr Marsden’s children the passing of someone their own age, especially a child they had played with so happily, would have been very difficult to cope with. Annie was buried close to their own mother’s grave in the Priory churchyard.

Annie Darwin’s much-visited grave in the Priory Churchyard, Great Malvern.

Notes

1 JRD, 10 March 1834.

2 Simpson, Helen J., The Day the Trains Came (Gracewing Fowler Wright Books, 1997), p. 101.

3 McMenemy, William H., Life and Times of Sir Charles Hastings (Livingstone, 1959), p. 286.

4 Keynes, Randal, Annie’s Box: Charles Darwin, his Daughter and Human Evolution (Fourth Estate, 2001), p. 166.

5 Ibid., p. 198.

6 Tennyson, Alfred, The Letters of Alfred Tennyson, vol. II, ed. by Cecil Y. Lang and Edgar F. Shannon (Oxford University Press, 1987), p. 15.