CHAPTER 4

Driving Down Emissions

If all the cars in the United States were placed end to end,

it would probably be Labor Day Weekend.

—Doug Larson

There's no point in searching your house for the largest contribution you make to climate change: the culprits are most likely parked in your driveway. If you are like the average American, driving accounts for about one-quarter of your total carbon emissions. There is simply no getting around the fact that our cars are a sizable piece of the global warming problem.

Today in the United States, there are roughly 240 million cars and light trucks on the road, traveling a mind-boggling 2.7 trillion miles annually. That's enough miles to make more than 14,000 round-trip voyages to the sun. And almost every one of those miles is driven by burning gasoline made from oil—with all of its serious drawbacks, from price spikes that spur recessions to reliance on a world oil market that entangles our nation in the politics of some of the most volatile regions of the world. Little wonder a string of U.S. presidents, stretching back at least to Richard Nixon, have lamented the nation's “addiction” to oil.

Not surprisingly, our national dependence on automobiles that burn gasoline has also inflicted some of the most consequential and damaging impacts on our planet. Each year in the United States, our cars are responsible for emissions of about 1.6 billion tons of carbon dioxide and other heat-trapping gases into the atmosphere. All by itself, this amount represents a significant share of the entire world's global warming emissions.

And if the sheer scale of heat-trapping emissions from Americans’ cars weren't enough, the story gets worse in the larger context. Compared with the rest of the world, the gas-guzzling cars in this country represent one of the planet's most lopsided resource hogs. According to one 2006 study, the United States, with less than 5 percent of the world's population, is responsible for about 45 percent of the world's automotive carbon dioxide emissions.

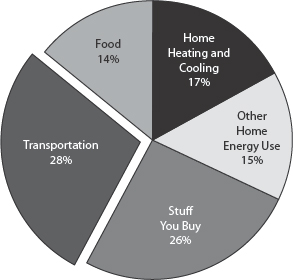

Figure 4.1. Emissions from Transportation

For the average American, car use accounts for more than one-quarter of total carbon dioxide emissions. Source: UCS modeling.

It is almost impossible not to feel dwarfed by the immense scale of the global warming emissions from our cars. But as vast as the problem is, it results from a myriad of individual decisions—including the ones you make every day. With the help of the recommendations in this chapter, each of us can take care of our personal share of this global problem and start to become part of the solution.

The first thing to consider is that when all stages of production and combustion are counted, every single gallon of gas a car burns emits nearly 25 pounds of carbon dioxide and other global warming gases into the atmosphere. About 5 pounds of that come from the extraction of petroleum and the production and delivery of the fuel. But the great bulk of automobile heat-trapping emissions—more than 19 pounds per gallon—comes right out of a car's tailpipe.

ASK THE EXPERTS

How Can a Car's Emissions Weigh More Than the Gasoline That Went into the Tank?

In considering all the emissions that vehicles cause, from the production of oil to the use of fuel, the UCS Climate Team calculates that the average vehicle emits nearly 25 pounds of carbon dioxide for each gallon of gasoline it uses. Of this amount, oil drilling and the refining and distribution of gasoline account for nearly 5 pounds of global warming pollution per gallon; burning the gas in your car's engine emits another 19.6 pounds of carbon dioxide directly from the exhaust pipe.

Since a gallon of gasoline weighs only about 6 pounds, how can it possibly produce more than three times its weight in emissions? The answer relates to the fact that gasoline is densely packed with carbon. When gasoline burns, its carbon is released into the air, where it combines with oxygen to form carbon dioxide. In CO2, each carbon atom bonds with two oxygen atoms (as you remember from high school chemistry, that's what the “2” stands for). Oxygen has a higher atomic weight than carbon, so in a molecule of carbon dioxide, most of the weight comes from the two oxygen atoms. As a result, the heat-trapping carbon dioxide weighs just over three times more than the carbon it contains.

As the box explains, it is a fact of chemistry that a gallon of gasoline weighing just over six pounds can release more than three times that amount of pollutants into the air. An average driver is responsible for about twice his or her own weight in carbon dioxide for every tankful of gas used. That's several hundred pounds of heat-trapping emissions the atmosphere would be far better off without.

A car that is driven 12,000 miles per year (about the national average) and that gets roughly 20 miles per gallon, or mpg (also about the real-world national average), is responsible for more than seven tons of carbon dioxide annually. That's approximately three and one-half times the car's weight in heat-trapping emissions into the atmosphere each year. And those seven tons per year are harming the planet.

So that's the bad news.

The good news is, you can do something about it. The cars we buy and our driving habits are so resource inefficient that they represent some of the “lowest-hanging fruit” available to those of us seeking to reduce our emissions. Many of us could go a long way toward the first-year goal of a 20 percent reduction in our carbon footprint just by making some simple changes in how we get around. If you are serious about reducing your carbon emissions, the vehicle you drive and your driving habits are great places to start.

While the gas-powered automobile is deeply embedded in Americans’ current way of life, it hasn't always played such a central role, and its present status need not be permanent. In the United States, we've had a longstanding love affair with automobiles for the convenience, mobility, and autonomy they offer (not to mention the aura of glamour they hold for many people). Today, it is hard to remember that less than a century ago railroads were the backbone of the U.S. transportation system, and not just for freight. In 1920 (the peak year of U.S. train ridership, aside from a brief surge during World War II), the average American took some 150 trips per year on local rail systems and another 12 train trips from one city to another.

Since that long-ago time, we've become more dependent on our fleet of cars than ever. And there are a lot more of them than ever before, too. As recently as 1950, there were only enough cars on the road for 28 percent of the population to drive one. Today, there are twice as many Americans, but the number of vehicles is equal to some 80 percent of the population—that's more cars than there are people licensed to drive them.

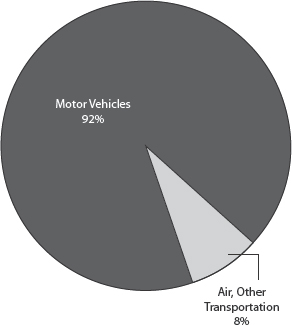

Even more than the number of cars we own, our automobile dependence is reflected in the statistics on how much we drive. Commuting offers a good example. In 1960, just 64 percent of Americans commuted to work by car, while 22 percent took public transportation or walked. By 2009, the number of public transit users and walkers had fallen to 8 percent, with 92 percent of Americans driving to work each day. Even carpooling is down: according to the latest figures, more than three-quarters of all American workers drive to work each day alone in their cars, while only 10 percent carpool—half of what it was 30 years ago.

UCS Climate Team FAST FACT

On average, your car emits seven tons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere each year—about three and one-half times the vehicle's weight.

The good news is that some things are starting to change. For one thing, requirements are now in place to deliver a boost of roughly 25 percent in new car fuel economy by 2016, and automakers are on record supporting a proposal to nearly double fuel economy by 2025. At the same time, we stand on the verge of an exciting transition in the auto industry. The battery-electric Nissan Leaf and the gas-electric, plug-in hybrid Chevrolet Volt are now on the showroom floor, and most major car companies have announced plans to offer models driven partially or completely by batteries or fuel cells within the next few years. We will discuss these choices in more detail shortly, but the important thing to remember is that while electric-drive vehicles—battery, fuel cell, and plug-in hybrid electric cars—won't take over the car market overnight, they could combine with fuel economy improvements and better fuels as part of a revolution that helps to dramatically cut urban smog-forming pollution, reduce U.S. global warming emissions by 80 percent or more, and effectively end our addiction to oil.

Such a change will very likely take decades, but revolutionary changes in transportation have happened surprisingly quickly before. It is worth remembering that American consumers were still skeptical about gas-powered cars back in 1908, when Henry Ford unveiled his company's Model T. Within just six years, however, Ford had produced more cars than all other automakers combined, and the era of gas-powered vehicles had swept the nation.

What You Can Do

Starting now, you can make many changes, large and small, to lower your transportation emissions. None is especially hard. Most will save money; some will even improve your health. This chapter will review four overlapping strategies to reduce your personal contribution to global warming. But let's start with the big-ticket item that could probably make the most dramatic difference.

BUY A FUEL-EFFICIENT CAR

It doesn't happen often, but once every several years you make a decision that has an enormous, lasting impact on your energy use and carbon emissions: you buy a car. Whether you are buying a car for the first time or replacing one you currently own, think long and hard. The choice you make in the showroom or on the used car lot will determine your emissions for as long as you own and drive that vehicle. Of course, we all know that some cars get better gas mileage than others. But if you're like most Americans, this fact has not played a big enough role in your car-buying decisions in the past. This time around, it should. This section shows what a big difference a fuel-efficient car can make to the environment—and to your pocketbook.

Let's walk through the data.

The 240 million cars and light trucks on the road in the United States today consume about 130 billion gallons of gasoline annually. That puts a big burden on our climate when it comes to global warming emissions. But in a good year for the auto industry, about 16 million of those cars and light trucks are replaced with new ones, and about two and a half times as many exchange hands in the used car market. So every year there are about 55 million opportunities for Americans purchasing a car to influence the automobile market and emissions for decades to come.

What does this mean for you? Well, when it's time to buy a car, choose the most fuel-efficient model that meets your ordinary transportation needs. Sure, you'd like to be able to haul a heavy trailer if you move to a new apartment, and you'd like to have room for your entire extended family when you take a vacation. But on those occasions, you can rent a pickup truck or an extra-large SUV. Buying a vehicle for those infrequent needs is expensive and will waste a lot of fuel along the way.

When we think about it, we probably don't all need to drive a three-ton behemoth to complete our routine tasks, such as getting to work and picking up groceries. Unless we have a big family or a home-based business, most of our routine tasks can be accomplished with a modest-sized, fuel-efficient car. Not only will it dramatically reduce emissions, it will save money every time we drive over the life of the car.

Remember, too, that while the size of the car is important, it is not the only factor affecting fuel efficiency. The diminutive Smart Car, distributed by Mercedes-Benz, may be the best choice for squeezing into tight urban parking spaces, for example. But it may not be the smartest choice for saving gas: in 2011 the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) rated the tiny two-seater at 36 mpg, while the Honda Civic Hybrid, with seating for five and more than twice the passenger volume, was rated at 42 mpg.

The key point to remember is that all other things being equal, a more fuel-efficient car pollutes less. When you start looking at the data, you may be surprised by the difference fuel efficiency makes to the environment. The U.S. Department of Energy and the EPA publish official estimates of city, highway, and average gas mileage for each model of car sold in the United States. The accuracy of these mileage estimates has been debated, but they provide a useful standard of comparison. For the latest information on fuel efficiency, be sure to visit the agencies’ joint website at www.fueleconomy.gov before purchasing your next vehicle.

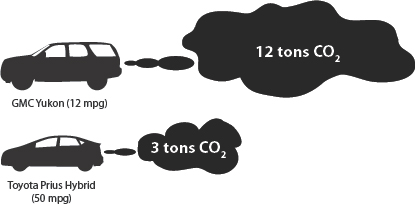

A review of the site's data about commonly purchased cars in the 2011 model year reveals that you could buy anything from a Toyota Prius, rated at 50 mpg—the highest fuel economy gasoline car—to a GMC Yukon four-wheel-drive SUV, rated as the year's worst SUV on fuel economy, at 12 mpg.* The difference in emissions between these vehicles is much larger than you might imagine.

Assume the car is driven the average American's 12,000 miles a year. If the car is a Prius, rated at 50 mpg, it will emit less than 3 tons of carbon dioxide per year; if a GMC Yukon (or a similar large SUV) drives the same distance, it will emit 12 tons per year—four times more. The difference is 9 extra tons of carbon dioxide emitted every year for the lifetime of the car.

ASK THE EXPERTS

But Aren't SUVs Safer?

Large, heavy sport-utility vehicles, looming over smaller cars on the road, aren't inherently safe, even if they look like they should be. It seems like common sense: from the point of view of protecting the passengers, isn't it better to be inside a big, heavy hunk of metal rather than a smaller, lighter one?

The data suggest that bigger and heavier does not mean safer. One large-scale study of children injured in motor vehicle accidents found that the most important variables for kids’ safety are proper use of seat belts and keeping the children out of the front seat. The study found that the increased tendency of SUVs to roll over offset any benefit of their greater weight, such that children's injury rates were about the same in SUVs and in cars.

In fact, a detailed statistical analysis of traffic fatalities and serious injuries from 2000 to 2007 found that vehicle design and other factors (e.g., driver age, rural driving) had much larger roles in vehicle safety than did size and weight. For example, the drivers of compact crossover vehicles (car-based vehicles that ride lower to the ground and have the functionality of SUVs) had a lower risk of a fatality or serious injury than the drivers of bigger and heavier SUVs. Making matters worse for SUVs, the same study found that they also put other drivers at a greater risk of fatality.

The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration tests vehicles to make sure their designs are safe, and it provides a simple five-star rating system available at www.safercar.gov. So, when you are in the market for a vehicle, keep your eyes on the safety stars, not the size and weight of the vehicle. And when you are on the road, make sure everyone is buckled up and in the right seat, and drive defensively.

The foregoing example is an extreme one: the Prius is, of course, quite a bit smaller than the Yukon. But even switching from a more modest-sized SUV to a Prius or another fuel-efficient hybrid car could easily cut your emissions in half. Either way, the reductions in emissions—and savings in gasoline costs over the life of the car—are dramatic.

How dramatic?

To keep the numbers simple, let's compare one car that gets 40 mpg with another that gets 20 mpg. In 2011, some seven models reached or exceeded 40 mpg, and the number of such new fuel-efficient models will almost surely grow in the future. The alternative, 20 mpg, is around the national average for old and new cars combined; in 2011, you could buy that level of relative fuel inefficiency in many new models of pickup trucks and SUVs and even in cars such as the Ford Fusion all-wheel drive, rated at 19 mpg, or the Subaru Outback, rated at 20 mpg, not to mention virtually any car with a V8 engine, such as the Ford Mustang, which even in 2011 weighed in at 17 mpg.

Figure 4.2. Vehicle Emission Comparison

By trading in that SUV for a Toyota Prius or another fuel-efficient hybrid, you'll emit just one-quarter to one-half as much carbon dioxide when you drive—keeping some six to nine tons of carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere every year for the lifetime of the car.

Source: UCS Modeling.

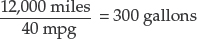

First, let's compare how much gas the two cars will use. At 12,000 miles per year of driving, the 40-mpg car will need

For the same amount of driving, the 20-mpg car will need

If you buy the 40-mpg car instead of the 20-mpg one, you will save 300 gallons of gasoline every year. That's enough to avoid almost 3.8 tons of emissions per year, nearly reaching your 20 percent goal with just one major purchase. Of course, the car will keep consuming gasoline until it is scrapped, perhaps 15 years or so after it is purchased. If you plan to own and drive the same car for 15 years, you're looking at a lifetime savings of 4,500 gallons of gasoline.

ASK THE EXPERTS

Can the Auto Industry Make More Fuel-Efficient Cars?

The short answer is yes.

Increasing the fuel efficiency of new cars and trucks is a critical step toward cutting America's oil dependence and reducing carbon emissions. Expert assessments from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT); the University of Michig n; the University of California, Davis; and the EPA show that we have the know-how to put the needed technology to work. The studies by researchers at MIT and UC Davis show that if manufacturers applied basic clean car technologies to all cars (such as improved engine efficiency and aerodynamics), they could reduce today's average vehicle fuel use and emissions by 45 percent over the next 20 years; making use of hybrid vehicle technology could achieve reductions of 60 percent over the same period. In both cases, the vehicles would deliver the same size, safety, and performance consumers enjoy today.

While automakers have the technology to increase fuel efficiency and reduce global warming pollution, they've often needed to be pushed, not just by consumers but also by government standards, to get this technology off the shelf and into the showroom. That's why the Union of Concerned Scientists has long been in the forefront of the movement for stronger federal fuel efficiency and global warming pollution standards, with current analysis urging standards that would cut new vehicle fuel use and emissions at least in half by 2025.

Even if you figure that the price of gas will stay around $3.50 per gallon over that time (an unlikely prospect because gasoline prices will probably rise in coming years), that's worth more than $15,000 during the life of the car. If gasoline prices rise to $4.50 per gallon, that would equal more than $20,000—either way, it represents a fair portion of the price of the vehicle. And at nearly 25 pounds of carbon dioxide emissions per gallon, the difference between these two vehicles amounts to a whopping 55 tons of emissions over the lifetime of the vehicle.

Many people make decisions based on shorter time horizons. But even if you count only the fuel used in the next five years, the difference of 300 gallons per year means a total savings of 1,500 gallons. That will keep some 18 tons of emissions out of the atmosphere and save more than $5,000—and that's not counting the higher resale value of more efficient vehicles, according to the latest figures.

Whichever way you do the arithmetic, the 40-mpg car will save thousands of dollars at the gas pump and keep many tons of global warming emissions from the atmosphere. It's well worth remembering those numbers when you are ready to purchase your next car.

THINK BEFORE YOU DRIVE

As we have seen, fuel efficiency makes a huge difference in your share of carbon emissions from transportation. Still, no matter what kind of car you own, one of the smartest ways you can drive down your emissions is by driving less.

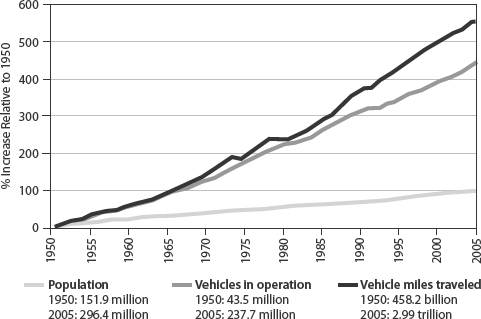

At least until the economic downturn in 2008, the statistics on our driving habits suggest that people have been doing precisely the opposite. Figure 4.3 tells the story. Since 1950, the U.S. population has doubled, and the number of cars on the road has more than quadrupled. But the biggest increase by far can be seen in our collective annual vehicle miles traveled, or VMT in transportation lingo. Since 1950, our VMT has increased more than six-fold. In other words, we don't just have a lot more cars; we're also driving them more than ever.

Americans’ ballooning VMT is especially worrisome because unless we reverse the increase in miles driven, we will threaten the gains we might achieve from improved fuel efficiency.

When you look at the data, one fact jumps out: Americans are more dependent on cars than just about any other people on the planet. In the United States, more than 80 percent of all trips are taken by car and light truck, compared with 60 percent of all trips in Germany and 45 percent in the Netherlands. Sure, our country is big and spread out, with sparse public transit options in many areas. But a closer look at our habits reveals a good deal about how we rack up all that VMT. According to the latest data from the U.S. Department of Transportation, more than 60 percent of all trips by car cover no more than six miles—and many are far shorter.

Figure 4.3 U.S. Increase in Vehicle Miles Traveled (VMT)

In the United States, the number of vehicle miles traveled has risen more than six-fold since 1950, faster than the growth in population or the increase in cars on the road.

Source: UCS, adapted from Davis and Diegel, U.S. Department of Energy, Transportation Energy Data Book, 2007.

We've all done it: hopping in the car for a quick trip to the nearest mailbox and then, shortly after returning home, driving to the grocery store for that missing dinner ingredient. A simple strategy for driving less is “trip chaining”—the fancy term for taking that trip to the store or post office on your way home from work rather making a separate trip after you get home. Remember, every car trip not taken reduces your overall emissions and saves money on gasoline.

Suza Francina, a former mayor of Ojai, California, adopted a more dramatic strategy years ago to cut down on short trips. “When I learned that half of all car trips were less than three miles in length,” Francina says, “I made a vow that, except for emergencies, I would make all trips within a three-mile radius on foot or bicycle.” To follow through on her pledge, Francina purchased a bicycle trailer big enough for her weekly groceries. She says the benefits to her health alone have been well worth the extra effort.

Another strategy for driving less is for a family to try to share one car instead of owning two. Gina Diamond, a Seattle resident, made this choice in 2007. She and her husband junked one of their two cars—the older, gas-guzzling one they had inherited—and Gina, who works mostly at home, made the commitment to walk the mile and a half to take her daughter to and from preschool. She says she has sometimes had second thoughts about her decision on cold or rainy days. But the weather has never dampened her enthusiasm for the extra exercise and the relaxed time to chat with her daughter along the way.

Of course, a growing number of people, especially city dwellers and those near colleges, are finding that they can get along fine—and save a lot of money—by not owning a car at all. Their decision has been greatly aided in recent years by the growth of car-sharing companies such as Zipcar, which in 2011 boasted some 560,000 members and 8,000 vehicles in 60 U.S. cities and about 230 college campuses. A car sharer can easily locate the nearest Zipcar online or with a mobile phone app and rent it on the spot by the hour. This is a great option for those who make only occasional trips by car. Unlike car owners, users of such car-sharing services pay only when they use a vehicle. Not surprisingly, perhaps, one recent study found that regular users of car-sharing services traveled one-third fewer miles than their car-owning counterparts, who pay for their vehicles (in car payments, insurance premiums, and excise tax) whether they drive them or not.

Even if you don't want to switch to walking or biking for short distances and would rather not get rid of your car, you might consider simply leaving it at home one day a week and finding another way to get to work, such as carpooling or biking. The city of Boulder, Colorado, in conjunction with local businesses, is a proponent of that idea. Since the summer of 2010, Boulder's Driven to Drive Less program has enlisted residents to pledge to give up driving at least one day per week. In exchange, participants receive special perks and discounts from local stores and restaurants.

UCS Climate Team FAST FACT

In a program begun in Boulder, Colorado, in 2010, some 500 residents have pledged to leave their cars home one day per week. In return, they receive perks and discounts from local merchants. At average driving rates, this effort alone could keep some 500 tons of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere annually.

Aaron Kennedy, a Boulder restaurant owner, is both a participant in and a sponsor of the program. “It's liberating to leave my car at home,” he says. “I don't have to find and pay for parking, watch my speed to avoid tickets, sit in stop-and-go traffic, or fill up my gas tank as often.” Kennedy says he loves the exercise he gets by riding his bike and notes that it takes him only 20 to 30 minutes more to make his commute than it did in a car. He is so taken with the program that he has begun to leave his car home several days per week. And he is not alone. Within its first three months, this local program in a relatively small city had enlisted nearly 500 residents.

If you're thinking of leaving the car home one or more days per week, you might also talk to your employer about telecommuting. Recent figures show that the number of Americans who work from home is rising significantly. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, some 24 percent of the nation's workforce work from home at least one day per month, and as many as 9 percent work from home full-time.

Of course, telecommuting provides an environmental benefit by eliminating a round-trip vehicle trip and the emissions it would have caused. One analysis found that if over the next 12 years, the number of U.S. workers telecommuting full-time increased to 14 percent of the workforce, it could eliminate 136 billion vehicle travel miles annually, resulting in a 5 percent reduction in the nation's total car emissions.* So consider telecommuting at least part of the time as one possible strategy for driving less. Given that the average daily round-trip commute by car takes 48 minutes, working from home won't just save gasoline and reduce your emissions; it will save you precious time as well.

FILL ’ER UP WITH PASSENGERS

As noted earlier, another long-term trend in American vehicle use is how often we drive alone. As the number of cars has increased, average vehicle occupancy has declined. According to the U.S. Census Bureau's Journey to Work Survey, the proportion of single-occupant commuter trips increased from 64 percent in 1980 to 73 percent in 1990 and almost 76 percent in 2000. The number of people carpooling, meanwhile, has dropped. In 1980, nearly 20 percent of Americans carpooled to work. By 2009, the proportion using carpools had fallen to 10 percent.

The fact is, shared use of vehicles has declined in all categories of personal car travel. Across all automobile trips for all purposes, the average number of occupants per vehicle in 2009 was 1.7 persons, down from 1.9 in 1977.

If you're looking for one of the quickest and easiest ways to cut your transportation emissions in half, here it is: buddy up with friends and family and share rides.

Each additional car passenger adds only a small percentage to the vehicle's total weight, fuel use, and emissions. So with two people in a car, emissions per passenger-mile are only slightly more than half the amount with one person in the same car.

Of course, the same principle applies many times over on a bus or train, with an added bonus. When you decide to drive, you are putting an additional vehicle on the road. If you take a train or bus, in most cases you are occupying a seat on a vehicle that would have made the same trip without you. In that sense, you are contributing very few, if any, additional emissions to the environment.

Despite its decline in popularity, carpooling remains a smart and easy option, saving money and dramatically cutting carbon emissions. Interestingly, while the overall numbers of carpoolers are down, some new twists on the idea are gaining popularity. One is Internet-based ride sharing. Companies such as eRide Share.com and ride-sharing listings on www.craigslist.org make it more convenient than ever to find rides and riders, especially for longer trips.

Some pilot projects are even taking web-based ride sharing to new technological heights. One such nascent effort, called Avego, offers a smartphone app that allows “real-time ridesharing.” In a pilot project begun in January 2011 in Seattle, the Washington State Department of Transportation is working with Avego to allow 250 drivers with GPS-enabled smartphones to offer the empty seats in their vehicles to some 750 similarly equipped riders along State Route 520. If a member of the program is driving on the highway, the software identifies anyone in the network who is looking for a ride at that moment and links the two. Once a match is made, the software facilitates the pickup and drop-off and even allows for electronic micropayments to allow riders to share the cost of the journey.

A lower-tech version of real-time carpooling, called “slugging,” is also gaining popularity in some parts of California and around Washington, DC, which is notorious for its rush-hour traffic congestion. Commuters seeking a ride line up at designated spots known as slug lines. Cars pull up to the slug line if they need additional passengers to qualify for the three-person high-occupancy vehicle (HOV) lanes. The sluggers display signs or simply call out their destinations, which are always a generally understood drop-off point near a subway stop. No money is exchanged. The “sluggers” get a quicker ride for free, while the drivers get access to the less congested HOV lanes—and cut their carbon emissions by two-thirds.

With any ride-sharing program, personal safety is an important consideration, and participants should exercise caution. However you go about it, though, safely putting extra passengers in your car makes sense as a strategy to combat global warming.

DRIVE SMARTER

“Use your gas wisely.” This slogan, which appeared on World War II ration cards, is still relevant today. Out on the not-so-open road, though, it is not always easy to carry out. We've all been there: bumper-to-bumper stop-and-go traffic; unexpected delays for road construction or accidents; way too many red lights; a car in front of us going inexplicably slowly on a day when we're running late and hoping to make up some time.

An all-too-common response to traffic congestion is to drive frenetically, a strategy that rarely gets us to our destination any faster. And it is surprising to learn how much gasoline it can waste. On the highway especially, stressed-out driving, such as repeated braking followed by sudden acceleration, can lower a car's gas mileage by as much as 30 percent, according to the EPA. Driving too fast will also cause your car to guzzle gas. Data from Oak Ridge National Laboratory's Transportation Energy Data Book indicate that driving at 75 miles per hour reduces your car's fuel economy by more than 20 percent compared with driving at 60 miles per hour. Smarter driving techniques can certainly help save gas and reduce emissions for most drivers. In case you have doubts, the city of Denver has the quantitative data to prove it.

In Denver's 2009 Driving Change program, the city outfitted some 400 local cars, including 160 city vehicles, with an Internet-based system that kept close track of how much gasoline each car was consuming as it operated. Participating drivers received detailed, individualized online information at their home computers about how they could improve their driving to reduce their carbon emissions. During the year the program was in operation, Denver found that on the basis of the feedback the system provided, participants cut their cars’ overall carbon emissions by 10 percent.

One of the most notable findings of Denver's Driving Change program was that the feedback on emissions helped participants decrease their cars’ idling time by more than one-third. According to one estimate, voluntary idling adds up to more than 100 million tons of carbon dioxide emissions annually in the United States alone, so it's easy to see the cumulative power of driving smarter.

UCS Climate Team FAST FACT

A high-tech Internet-based system tested in 2009 by the city of Denver offered real-time feedback to some 400 drivers about the emissions they were causing. Armed with the information, the drivers were quickly able to improve their driving-especially their idling-habits enough to reduce their emissions by 10 percent.

Denver's tracking system gave participants a lot of valuable information. But you really don't need a fancy online readout to help you pay more attention to your driving habits. Here are six steps to smarter driving that can make a real difference to the climate:

- Keep your vehicle well tuned. Simple maintenance—such as regular oil changes, air filter changes, and spark plug replacements—will lengthen the life of a vehicle as well as improve fuel economy and minimize emissions.

- Check your tires regularly. Low tire pressure reduces a car's fuel efficiency by increasing the resistance its engine must overcome. Keeping your tires properly inflated will save fuel and lower your emissions. Also, when it's time to replace your tires, consider getting a set of low-rolling-resistance (LRR) tires. These tires may cost slightly more than traditional replacement tires, but by reducing rolling resistance by 10 percent, they can improve the gas mileage of most passenger vehicles by 1 to 2 percent.

- Speed up and slow down gradually. Avoid jackrabbit starts. When coming to a stop, take your foot off the gas early so that you're slowing down even before you hit the brakes. On the highway especially, this technique can increase your car's fuel efficiency significantly.

- Remove the empty roof rack. Don't leave luggage carriers or bike racks on the car when they are not in use. Cars are designed for aerodynamic efficiency; anything that changes the overall shape and creates air resistance will decrease gas mileage. According to the EPA, a roof rack can decrease a car's fuel economy by as much as 5 percent.

- Be weight conscious. Items inside the car accelerate along with the car, and that means more fuel consumption. It's a good idea to remove unnecessary items from the trunk or backseat. For every 100 pounds of extra weight in a vehicle, fuel economy decreases by 1 to 2 percent.

- Don't idle. During start-up, a car's engine burns some extra gasoline. But letting an engine idle for more than a minute burns more fuel than turning off the engine and restarting it. Today's fuel injection vehicles (which have been the norm since the mid-1980s) can be restarted frequently without engine damage and need no more than 30 seconds to warm up even on the coldest winter days.

ASK THE EXPERTS

Open the Windows or Turn On the A/C?

Maybe you have had this debate: the environmentalist in your car wants to turn off the air conditioner in hot weather and open the windows instead, arguing that the air conditioner draws extra power from the engine, using more gas and thus increasing your emissions. Is it true? Will the car use less gas without the air conditioner, or will opening the windows create enough aerodynamic drag to offset any savings?

Technically, the environmentalist may be right. A road test in a Honda Accord by Consumer Reports in 2008 found that the air conditioner reduced gas mileage by about 3 percent at 65 miles per hour, while open windows had no measurable effect on gas mileage. As a practical matter, though, neither choice will make as much of a difference as most of the other recommendations in this chapter, especially in a newer car. Automotive air-conditioning has become more efficient in recent years, and new models use considerably less power than older ones did. So in this case, don't sweat it either way. Save gas in other ways and cool your car by whichever method helps you drive most comfortably and carefully.

Fueling Our Future

Although the overwhelming majority of cars on America's roads run on conventional unleaded gasoline, there are other fuel options currently available, with a wider array of choices on the horizon. Let's take a moment to see how some of these fuels stack up in terms of carbon emissions, starting with conventional fuels and working up to exciting emerging options such as cars powered by electricity from batteries or hydrogen fuel cells.

Conventional gasoline usually comes in three octane grades’ 87, 89, and 91—more commonly known as regular, midgrade, and premium. From a climate perspective, the only misconception to clear up is that premium gas will not help your car achieve better fuel economy. Gone, too, are the days when premium gasoline was the only grade to contain detergents that were supposed to help maintain an engine. The fact is, premium-grade gas costs more, and producing it typically uses more energy, so it may actually raise overall emissions slightly. The bottom line: use the grade of gasoline that the manufacturer recommends for your vehicle.

Diesel is no longer the “dirty fuel” it was several decades ago. An increasing number of car models running on today's diesel boast better efficiency and higher fuel economy than equivalent gasoline-powered cars. If you are in the market for a new car, these vehicles could be a good choice, especially if you do a lot of highway driving, where their fuel efficiency tends to excel. From a climate perspective, however, there is an important catch: diesel is more carbon intensive than conventional gas, so a car running on diesel will cause carbon emissions 10 to 15 percent higher than a car running on conventional gas that has the same gas mileage. To compare diesel models with those that run on regular gas, in other words, discount the fuel economy of the diesel vehicle by 10 to 15 percent to estimate the amount of carbon emissions it will produce, or just get the actual data from www.fueleconomy.gov. When you do that, you will see that many diesel cars are still a good choice as far as global warming is concerned, although there may be efficient gasoline, or gas-electric hybrid, options that will do just as well or better.

With either gasoline or diesel, however, you should be aware that when it comes to carbon emissions, both of these fuels are getting dirtier. We've tapped most of the easy-to-reach oil, so to keep up with rising demand we are pumping oil from deeper wells and separating oil from tar sands. Turning the latter into gasoline and burning it in a car results in roughly 15 percent higher carbon emissions than using conventional oil does. Even worse, some companies are now pushing to essentially squeeze oil from rocks—oil shale and coal—which would lead to twice the carbon footprint per gallon of today's gasoline.

Natural gas is an option for some car models on the market in 2011. The Honda Civic, for instance, comes in a natural gas model that delivers about a 15 percent reduction in global warming emissions (based on data from www.fueleconomy.gov)—about half the benefit of the Civic hybrid. Natural gas is cheaper than gasoline, but the vehicles that run on it are more expensive than their gasoline and hybrid counterparts. Also, there's not much infrastructure for fueling these vehicles, making them a better option for fleets of cars or trucks with a dedicated refueling station. An added consideration is that natural gas is increasingly produced by hydraulic fracturing techniques, popularly known as “fracking,” that pose real potential risks for increased leakage—natural gas, with its high methane content, is significantly more potent than carbon dioxide when it is released directly into the atmosphere—as well as potential impacts on groundwater. If you are an average consumer and want to focus on benefits to the climate, natural gas will deliver real benefits but is probably not your best vehicle choice.

Biofuels could play an important role if the technology for sustainable “low-carbon” biofuel works out. The driving idea behind biofuels is that they can—theoretically, at least—offer a carbon-neutral fuel source because the emissions caused by burning them are offset by the carbon dioxide taken up by the crops grown to make the fuel in the first place.

At many gas stations across the country, biofuels—in the form of ethanol made from corn—are already mixed into conventional gasoline at levels of up to 10 percent (and soon 15 percent for more modern cars). Some cars can also run on E85, a blend of 85 percent ethanol and 15 percent gasoline. But because there are very few fueling stations now offering this product, few of the consumers who buy those cars currently fill up with it. Ethanol has for some time been touted as an answer to the nation's growing demand for automotive fuel. The United States is, after all, spectacularly good at growing corn. Before the ethanol boom of recent years, U.S. farmers produced more corn than anyone wanted to buy, depressing prices and leading to expensive government subsidies for growers.

Unfortunately, despite the appeal of using excess corn to create a renewable fuel, corn-based ethanol hasn't lived up to its hype. For one thing, American agriculture itself runs on fossil fuel. Fertilizers and pesticides are produced in energy-intensive facilities, using petrochemicals. Farm machinery burns diesel fuel, as do the trucks that transport materials to farms and harvested crops to markets. (For more about emissions from agriculture, see chapter 7.) As a result, corn-based ethanol today leads to the same global warming emissions as, or even more than, gasoline.

Yet another challenge is that we don't produce nearly enough corn to power our vehicles. We already turn about one-third of our corn into ethanol, and even if we used the entire U.S. corn crop, it could replace only about 20 percent of the gasoline we use for transportation today. Long before that point, increased production of corn-based ethanol threatens to eat into food supplies and force up food prices, especially in a global market. As it is, there are serious concerns about the extent to which the ethanol boom is helping drive up global food prices, which are already stressed by floods, droughts, and increased demand for carbon-intensive products such as meat.

A better long-run vision for biofuels involves a new technology known as cellulosic biofuel. This offers the promise of creating fuel from garbage, wood wastes, and fast-growing plants such as switchgrass, which can be grown on land unsuitable for food production. Unfortunately, the cellulosic biofuel manufacturing process is still in its infancy, so it will take time for this fuel to have an impact on transportation emissions. Still, cellulosic biofuel does offer significant potential to lower our transportation-related carbon emissions, and it could well become a more viable fuel option in the years to come.

Electricity is, without doubt, the most exciting fuel option coming to the American car market. With the Nissan Leaf and Chevrolet Volt leading the way, electric-drive vehicles could be the start of a revolution, helping to dramatically reduce U.S. global warming emissions and effectively end our oil addiction. But to make such a revolution a reality, we will need patience, consumer interest, and smart government policies. Electric-drive vehicles won't solve global warming overnight. But their long-term potential is so great that they are worth careful consideration when you think about purchasing your next vehicle.

Electric vehicles are, at present, expensive to buy, but they can save a lot of money on fuel—around $15,000 over the life of the car, compared with a 20-mpg gas car at $3.50 per gallon. State and federal tax breaks can make electric vehicles even more affordable. In the longer term, as the technology takes hold, research and economies of scale are likely to lower their sticker prices substantially. If you are considering one of the electric vehicles that need to plug in, bear in mind, however, that most American homes will need to upgrade at least some of their electric wiring to effectively support it.

Battery-electric vehicles, such as the Nissan Leaf, have a limited range on a single charge of their battery packs, but they could be a great option for commuting and city driving, especially as a second car for families that need two vehicles. The potential for fast charging could extend the range of battery-electric vehicles but would require significant infrastructure investments and may compromise some of the advantages. Their global warming benefits are superior to those of a good hybrid if the electricity is generated from natural gas, and they are emission free when recharged with electricity produced from renewable resources such as wind and solar power. If you live in a region that gets its electricity primarily from coal, however, a good hybrid will do more to cut emissions.

Plug-in electric hybrids, such as the Chevrolet Volt, still have a gasoline engine, but they also have an electric motor and a large battery pack so they can run on electricity from the power grid. This means that they have a great range because when their batteries get low, they can run on gas and operate just like a more conventional hybrid, with similar emissions. On the other hand, their gasoline usage will vary considerably, depending on which fuel they use. Like their all-electric counterparts, their potential for reducing emissions will depend on how the electricity used to recharge is produced. As long as you live in a region where electricity is not produced predominantly by coal, however, you can maximize your fuel efficiency impact by running these vehicles on electricity as often as possible, using them primarily for short and medium distances.

Fuel cell electric vehicles, such as the Honda Clarity, are expected to come to the broader car market by 2015. Instead of recharging batteries from the grid, they use fuel cells to combine hydrogen with air to generate electricity and water with no tailpipe emissions. The infrastructure to support them is starting to be built in southern California, where pilot programs are underway. There are a number of ways to create hydrogen, although many use fossil fuels and thereby create some amount of carbon emissions. Much as with battery-electric vehicles, using natural gas would lead to larger reductions in global warming emissions than would a good hybrid, while using renewable electricity, such as wind power, would nearly eliminate global warming emissions from cars. At this point, however, fuel cell vehicles are not an option for most car buyers.

One other thing to note as you consider an electric vehicle is that the otherwise very helpful www.fueleconomy.gov website does not yet give global warming information about these vehicles. Unfortunately, the government offers only a “miles-per-gallon equivalent,” which tells little or nothing about the cars’ global warming emissions. Although cars running on electricity don't emit carbon from the tailpipe (the Nissan Leaf famously doesn't even have a tailpipe), they are only as clean as the grid or the hydrogen from which they get their electricity.

We've tried to offer some rules of thumb to help you think about the potential global warming emissions benefits of electric-drive vehicles, but as we discuss further in chapter 5, the emissions generated from the production of electricity vary significantly, depending on where you live. Still, there is little question that when it comes to global warming, electric vehicles are likely to pave the way to a cleaner future.

Reduce Your Long-Distance Travel

American society is famous for its mobility and dynamism. Many families are spread out over long distances, and people frequently move to take jobs in different regions. Of course, this leads to a lot of long-distance travel. According to the U.S. Department of Transportation's Bureau of Transportation Statistics, Americans annually make some 2.6 billion trips of 50 miles or longer, which add up to a whopping 1.3 trillion person-miles of long-distance travel.

All of this long-distance travel causes a lot of carbon emissions. After all, a single round-trip flight from Los Angeles to New York emits around a ton of carbon dioxide per passenger—equal to the amount an average American SUV driver would be responsible for emitting in a month of average driving. What should you do if you want to cut your long-distance emissions?

First of all, consider any long-distance travel plans carefully. If you are flying for pleasure, perhaps you might take a vacation closer to home. If your destination is set and the distance is not too great, perhaps you can find a more environmentally benign alternative to air travel. Going by bus is among the least carbon intensive ways of traveling, and trains are comparatively carbon friendly. On a per-passenger basis, a train trip can emit as little as one-quarter the emissions of an equivalent journey alone in a large car. You might consider reducing your emissions by making fewer long trips to visit family and staying longer when you go.

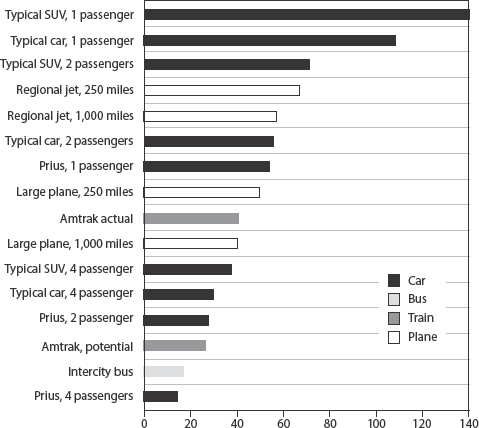

Figure 4.4 compares carbon emissions for many modes of transportation used for longer trips, clearly highlighting the benefits to the climate from having more passengers regardless of the mode of transport.

As the graph shows, the only option for longer trips that beats taking an intercity bus is driving a Prius with a total of four people in the car. The next best choices are taking an Amtrak train if it runs as full as the airlines (shown as “Amtrak potential” in the graph) or driving a Prius with two people on board. Of course, if you are just commuting to work or around town and you have access to an urban bus or transit system, that may well be the best choice.

At the other extreme, the worst ways to travel, in terms of emissions per passenger-mile, are driving alone in a typical car and driving alone or with one other person in a typical SUV. These choices cause more emissions than flying the same distance, even in a less efficient regional jet.

When you do fly, consider that all types of air travel are not equal. A report by the Union of Concerned Scientists, “Getting There Greener,” shows this clearly with an analysis of the emissions from various vacation travel options. Flying a family of four in first class from Chicago to Orlando for a vacation at Disney World, for instance, probably results in more carbon dioxide emissions than both parents would normally emit in a year's worth of commuting to and from work by car.

Figure 4.4 CO2 Emissions per 100 passenger miles

On a mile-for-mile basis, nothing reduces your emissions like adding passengers. This chart compares per-person carbon emissions for different modes of transportation on a 100-mile trip.

Source: UCS modeling.

First-class and business-class seats, of course, take up a larger share of the plane's passenger space and are therefore responsible for a somewhat larger share of the plane's emissions. Flying coach or economy class is better for the environment. And, as the “Getting There Greener” report found, flying in economy class often results in lower emissions per mile than driving with one person in the car. And these days, the airlines tend to pack most flights as close as possible to capacity, which lowers the relative per-person emission rates even more. At least that's something to console yourself with the next time you are feeling squeezed on an overcrowded flight.

An option of growing popularity when traveling by air is to purchase so-called carbon offsets—essentially paying someone to engage in an activity, such as maintaining forested areas, that absorbs as much carbon dioxide as your flight will emit. We address the topic of carbon offsets in more detail in chapter 8. Suffice it to say here that offsets are a good idea; in general, however, the best strategy is to try to find ways to reduce your own emissions as much as you can.

Of course, realistically speaking, for long trips there is often no viable alternative to flying. And travel is an important component of both work and play; it is one of the ways we learn about the world and make connections. Staying close to home is not always a reasonable option or a helpful recommendation.

Notably, even Colin Beavan, who in 2009 went to great lengths to live carbon neutral for a year, documenting his efforts in his blog, book, and documentary, No Impact Man, finally broke down when it came to visiting family for the holidays. For the entire year, Beavan, a Manhattan resident, had ridden his bike everywhere and even given up elevators in a city of skyscrapers. But he made an exception for a flight to Minneapolis with his wife and daughter.

For all the understandable fretting in the environmental literature over the carbon emissions from air travel, and despite the enormous amount of emissions a single airplane causes, it is worth remembering that passenger air travel accounts for less than 3 percent of total U.S. global warming emissions and less than 8 percent of household travel emissions. Even for long-distance travel, Americans still drive far more than they fly. Still, given the emissions involved in the average airplane trip, it pays to consider your options carefully.

As you consider the climate impact of your long-distance travel, one sector potentially ripe for reductions in carbon emissions is business travel, which represents over 40 percent of all long-distance trips. Americans take more than 405 million long-distance business trips per year. If you are flying a lot for work, you might find it relatively easy to reduce your emissions. Think about it. Are all your business trips really necessary? Maybe you could cut back on some trips or combine them to minimize your air travel. If a conference is not too far away, perhaps you could carpool with a coworker, greatly reducing your emissions.

Figure 4.5. Breakdown of Transportation Emissions

This chart shows the breakdown of total U.S. emissions in the transportation sector. Even for longdistance travel, Americans still drive far more than they fly. Source: UCS modeling.

Here again, technology is beginning to change the picture significantly. Advances in videoconferencing can dramatically reduce the need for business travel. As most firms know, sending a worker on a two-day trip to attend a meeting 500 miles away can easily cost $2,000 or more, taking into account the costs of accommodation, travel, and meals. Not only can high-quality videoconferencing save time and reduce those per-person costs by 90 percent or more; it can also greatly reduce the emissions caused by today's business travelers.

The Future of Transportation: It Needs to Look Different

The choices described in this chapter can help you lower transportation emissions, whether by buying a more fuel-efficient—or even electric—car, driving less and smarter, or flying less often and seeking lower-impact modes of long-distance travel.

But even if everyone followed all this advice, the choices currently in front of us are not enough. To prevent the worst outcomes of climate change and create a sustainable future, we need to build a transportation system for our grandchildren that looks very different from the one we have today but still allows people to go about their day-to-day business.

Transportation choices are closely linked to patterns of housing and urban development. Unlike many high-income countries, the United States is projected to have a growing population for the next several decades, so we will need to build new housing and new communities. The way these homes and communities are designed will make all the difference in our future transportation emissions. We'll discuss some of these bigger-picture considerations in later chapters. But there is no question that we must focus on creating cities that are centered on public transit and are bicycle and pedestrian friendly. We must develop highly efficient surface transportation between metropolitan areas that can minimize the need for air travel. Better planning is needed every step of the way, from local municipalities to the federal level.

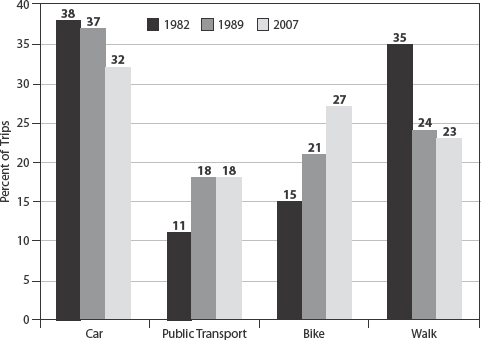

A study in 2011 by the urban planning experts Ralph Buehler at Virginia Tech and John Pucher at Rutgers University shows that we already know how to make many of the changes needed to reduce our transportation emissions, and we know these changes can work to build thriving, sustainable communities. Buehler and Pucher closely studied the transportation choices made over the past 40 years by Freiburg, Germany. A city of 220,000 in the southwest of the country, Freiburg is known throughout Germany as the nation's most sustainable city. It offers a model that American cities could emulate. Over the past three decades, Freiburg has created a transportation system in which the number of bicycle trips has nearly tripled, public transport ridership has almost doubled, and the share of trips by automobile has declined to 32 percent. The city has experienced strong economic growth and a dramatic drop in per capita carbon dioxide emissions from transport. To accomplish this, Freiburg officials created car-free pedestrian zones and restricted cars in the center of the city, upgraded suburban rail and regional bus services, and created more than 70 miles of bike paths.

Figure 4.6 Transportation Modes in Freiburg, Germany

Shown here are trends in the percentages of trips made by car, public transportation, bicycle, and walking in Freiburg, Germany, between 1982 and 2007.

Source: Adapted from Beuhler and Pucher, 2011.

Some U.S. cities, perhaps most notably Portland, Oregon, have already adopted a number of sustainable transportation and land use policies similar to the ones in Freiburg and many other cities.

Other trends from abroad are catching on in the United States as well. Amsterdam has long been famous for its high percentage of bicycle riders, and recently Paris has begun a high-profile bike-sharing program, which is catching on rapidly. Even the Parisian program, however, is dwarfed by the gargantuan bike-sharing program in Hangzhou, China, a city with a population nearing 7 million. Hangzhou's program boasts some 50,000 bikes at over 2,000 bike-share stations. With these bicycles, according to the program, Chinese riders now make an average of 240,000 trips each day.

Meanwhile, in 2008 Washington, DC, began Capital Bikeshare, the largest bicycle-sharing program to date in the United States, already boasting some 5,000 members. And New York City recently announced plans for a bike-share program with some 10,000 bikes and 600 kiosks.

Of course, we aren't suggesting that bicycles alone can solve the planet's global warming problem. One way or another, however, we need to create not only sustainable downtowns but also livable, walkable, bikeable suburban neighborhoods with transit connections to the rest of the metropolitan area and energy-efficient, high-speed intercity ground transit.

Getting to 20

In transportation, as in all areas where we need to reduce emissions, the long-term key is farsighted planning and decision making. As we work toward these goals, however, each of us needs to consider what we can do right now to move toward a sustainable future. We've already explained why reducing our emissions by 20 percent this year is an important goal. Since transportation accounts for such a large share of the average American's emissions, almost all of us will need to seek sizable reductions in the personal choices we make about how we get around.

Most of us can literally save tons of emissions (for years to come) with a single action: replacing an existing car with a far more fuel-efficient one. If that step is not practical this year (or your car already is fuel efficient), you can still get a long way toward the 20 percent goal by combining several strategies from this chapter that reduce the miles you travel, such as trip chaining, carpooling, leaving your car at home one or more days per week, changing your driving habits, and reducing your long-distance travel. By examining your own transportation choices and seeking out the best ways to reduce your emissions, you've already embarked on that journey.

*Most pickup trucks (and some oversized vans, as well as a few high-end luxury sports cars) are not included in these figures, and many get in the range of 9 to 11 mpg. From the standpoint of carbon emissions, your best bet is to avoid driving a pickup truck unless your livelihood depends on it.

*Of course, working at home leads to emissions as well if you normally adjust the heat and keep lights off when nobody is home, but if you follow the tips in chapters 5 and 6, you can keep that to a minimum, guaranteeing real emissions savings.