CHAPTER 8

The Right Stuff

You can't have everything. I mean,

where would you put it?

—Steven Wright

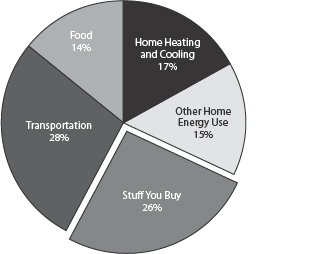

In the previous four chapters, we have examined our major contributions to global warming. The subjects we have covered so far—transportation, heating and cooling, electric appliances, and food—make up roughly three-quarters of our heat-trapping emissions. The wide variety of goods and services we buy account for the remaining quarter. It is a broad and diverse category, split fairly evenly between tangible items, such as furniture and clothing, and services, such as healthcare and legal advice.

As we will discuss, there are a number of ways to lower emissions in this category, but frankly, it's harder to make a significant dent here than in the other categories. As the chart illustrates, most of the goods and services we buy have a relatively small impact on the climate, and some specific categories lie mainly outside our individual control. See chapter 11 to learn how to have more control in those areas.

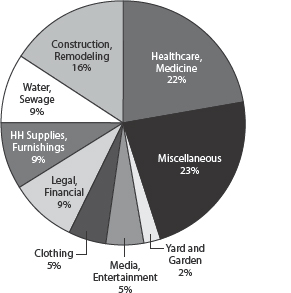

On our own, there is not much we can do to reduce the emissions from many of the services we purchase. Emissions related to healthcare, for example, from running hospitals and doctors’ offices to supporting health insurance companies and pharmaceutical companies, account for 22 percent of the emissions in this category—some 5.7 percent of the average American's total global warming emissions. Realistically, though, as a healthcare consumer you are not going to choose your doctor, your hospital, or your medications on the basis of their global warming emissions, nor would we recommend that you do. Still, you can make some measurable reductions in the emissions that result from the goods and services you buy, and in this chapter we offer some suggestions for doing so.

Figure 8.1. Emissions from Stuff You Buy

The goods and services you purchase account for more than one-quarter of your emissions, or more than five tons annually for the average American.

Source: UCS modeling.

Taken together, the tangible nonfood items we buy—such as clothing, housewares, furniture, and electronics—account for about 10 percent of Americans’ total global warming emissions. That translates to more than two tons of emissions for the average American every year. Most of us can reduce our emissions in this category fairly easily by finding smart ways to rein in excessive consumption. This recommendation boils down to two pieces of advice. First, buy less stuff. Second, when you do buy things, try to think about their impact on global warming, namely, how efficiently resources and energy have been used in their design, manufacture, and distribution. Between these two strategies, you may well find you can significantly reduce your carbon footprint with little real sacrifice. We'll talk about each approach separately.

Figure 8.2. Breakdown of Emissions from Stuff You Buy

This chart provides a breakdown of the emissions associated with some of the goods and services you purchase.

Source: UCS modeling.

Buy Less

Let's face it: most of our homes are filled with items we never really needed—toys our kids played with just a few times; poorly fitting clothes we rarely wear; gimmicky electronics that were popular for a couple of months; ill-considered gizmos bought on impulse. We could each make a real difference in reducing global warming by striving to avoid purchases that are likely to wind up in our attic or garage or in the trash. Buying less stuff has many advantages: it helps simplify and de-clutter our lives, it saves money, and it can lower our carbon emissions.

Many people who have chosen to closely monitor their consumption habits say buying less has other intangible advantages as well. Take the experience of Scott and Béa Johnson in Mill Valley, California, for instance. When she was younger, Béa worked as a nanny for a family who lost all their possessions in a fire. She says that experience led her to decide to limit her attachment to material goods. Several years ago, she and her husband, Scott, decided to pare down their stuff. They started with small things, such as borrowing books from the library instead of buying them and using cloth dishtowels instead of buying paper towels. As Béa recalls, the first changes they made showed her how much her stuff had psychologically weighed her down. “When we started getting rid of things, it was kind of addictive,” she says, adding that, odd as it may sound, “the less I have, the richer I feel.”

The Johnsons would be the first to acknowledge that they went considerably further than most families would want to go in the quest to avoid consuming. Today they keep their clothing to a minimum, with about seven changes of clothes for each of them and their two sons. They have turned off virtually all junk mail and buy almost all their food in bulk, even taking their own reusable jars to the store for such items as cheese and shampoo. As a result, when trash day comes, the Johnsons normally have absolutely no waste or recycling at all.

But the most striking thing about the Johnsons is that they say they don't feel deprived in any way. They have kept all the things they care most about (photographs and treasured family heirlooms, for example), and they spend the same amount on their kids as they would otherwise—but they—re more likely to give them experiences, such as a ski weekend or a certificate for a climbing gym, rather than electronic gadgets. Most of all, the Johnsons say, they just think very carefully before buying any new item.

Most of us won't want to adopt all of the Johnsons’ habits. But we could all benefit from adopting some of them. Unfortunately, the environmental literature tends to focus on choosing among items to buy rather than looking for alternatives to purchasing them in the first place. The fact is, cutting down on excess consumption is likely to do more to lower your global warming emissions than worrying about buying one thing versus another.

A good example can be seen in the flurry of recent articles comparing traditional books with electronic readers such as Amazon's Kindle or Apple's iPad to see which is the “greener” alternative. It is understandable that people would be curious about the subject. But as we will see, the analysis is less useful than it may at first appear.

When analysts crunch the numbers, they estimate that the emissions caused in manufacturing an electronic reader are about the same as those caused in manufacturing 20 to 40 books. So if you are a heavy reader who buys only new books, and if you keep your electronic reader for a number of years, the device might modestly lower your carbon footprint (especially if you replace your print subscriptions to newspapers and magazines with their electronic equivalents). What the debate obscures, however, is that a standard paperback book is responsible for around five and one-half pounds of carbon emissions in its manufacture and transport to your local bookstore. But we are each responsible for more carbon emissions than that when we drive six miles round-trip alone in a typical car to the bookstore. The point is this: don't waste time worrying about the carbon footprint of the way you read. Choose the form you enjoy and save your energy for areas where your choices will make a bigger difference—for instance, stopping at the bookstore on the way home from work instead of making an extra trip.

Buy Smarter

When it comes to items such as furniture and clothing, buying less is normally a more effective strategy than buying products that are climate friendly. With that said, when we face a choice between products, an eye to environmental considerations can often make a difference.

The best rule of thumb is to try, whenever possible, to buy products that embody higher resource or energy efficiency than whatever you are replacing. Buying a rake to replace your leaf blower will substantially reduce your emissions for that particular chore. The same goes for buying a fuel-efficient car to replace a gas-guzzler.

In general, buying well-made goods that will last a long time is a good strategy for reducing your emissions. It is also sensible to reward companies that have made progress in addressing global warming. Just make sure that the companies can point to specific efforts they are making rather than merely espousing environmental platitudes to get your business or advertising their products as more environmentally friendly than they really are. That's called “greenwashing,” and we discuss it more in chapter 10.

ASK THE EXPERTS

Is Organic Cotton Really Greener?

By most assessments, cotton is one of the most chemical-intensive crops in the world. Although it is grown on just 2 percent of the world's farmland, it accounts for some 10 percent of global pesticide use and roughly 25 percent of global use of insecticides.

At least one analysis from the United Kingdom shows that the chemical load of conventionally grown cotton results in global warming emissions more than double those from organic cotton. All other inputs being equal, even though that organic cotton T-shirt is more expensive than its conventionally grown counterpart, it does represent significantly lower carbon emissions—and is a better option for other environmental reasons as well. So buy organic cotton if you can, but don't go out of your way to do so. Focus instead on the more important steps you can take to reduce your direct transportation and household emissions. Remember: clothing purchases are responsible for only 5 percent of your emissions in this category—or 1.4 percent of your total consumer emissions, as shown in figure 8.2.

Here's one small example of how to take energy and resource use into consideration. As the box above shows, all other things being equal, organically grown cotton really does cause lower emissions than conventionally grown cotton because growing conventional cotton is an extremely chemical-intensive process, and organic methods remove this component of emissions from the manufacture of cotton fabric.

An equally important strategy to consider is buying used or refurbished items when you can. Such items (unless they are older, inefficient energy users such as used refrigerators or old gas-guzzling cars) virtually always result in fewer emissions than their brand-new counterparts. In other words, consider those garage sales or visits to the thrift shop as helping—however modestly—to combat climate change.

We'll address recycling more directly in a moment. But it also makes sense in general to choose items with reused or recycled content, such as refilled toner cartridges for your printer or copy machine and recycled paper products. Some companies offer furniture made from sustainably harvested or reclaimed wood, and homeowners who are remodeling can purchase sustainably harvested lumber. These products in particular can make a substantial difference compared with those made from virgin timber.

ASK THE EXPERTS

Does Wood Harvested Sustainably Really Make a Difference?

Most of us use wood products every day and purchase more than we realize. Of course, furniture and many of the building materials used to construct our homes and offices are made of wood, as are the paper products we use daily. Unlike fossil fuels and metals, the world's supply of wood is renewable. And, compared with steel, concrete, plastic, and brick, wood is a low-energy and low-emissions material for packaging and building—but only when it is not the cause of deforestation.

Worldwide, deforestation is occurring at an alarming rate, with an acre of tropical forest lost every second. As a result, emissions from tropical deforestation account for some 15 percent of the world's total carbon emissions—an enormous and largely preventable share. We cannot address global warming effectively if we ignore 15 percent of the problem.

The good news is that more wood products are being reused and recycled today than ever before. Improvements in recycling technology, availability, and financial support continue to help the spread of recycling efforts, which can further reduce pressures on primary forests. Buying recycled wood and paper products is a great way to lessen the demand for virgin timber.

Meanwhile, voluntary certification programs allow timber companies to meet globally approved standards of sustainable management. One of the largest certification programs, by the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC), has a specific set of forest management criteria that are currently being used on 41 million acres of tropical forest. Voluntary certification programs alone are unlikely to solve the problem of deforestation, but they do give consumers the opportunity to influence forestry practices and help prevent deforestation. The next time you are buying wood or wood products, look to see that they are certified as sustainably grown. Buying FSC-certified wood helps fight illegal deforestation by rewarding landowners who are managing their forests sustainably.

What about Recycling?

The strategies we've been discussing can be useful in purchasing new things. But what we do with our stuff when we are through with it also makes a difference. Even though only about 2 percent of total U.S. carbon emissions comes directly from solid waste disposal, that figure doesn't nearly capture the power of recycling in combating global warming, especially considering that the average American creates some 4.3 pounds of trash each day.

Recycling reduces global warming emissions in two principal ways: it reduces the need for virgin materials (and the emissions that result from making or extracting them), and it reduces emissions from waste disposal, particularly methane from landfills. Plus, recycling can save money, especially for those who live in a city or town with high trash disposal costs.

By recovering valuable materials and allowing them to be reused in place of new raw materials, recycling can reduce carbon emissions significantly. This is particularly important because the industries that produce raw materials are often the most carbon intensive in the manufacturing sphere; by comparison, the equivalent recycled materials are produced with low-energy, low-emissions processes.

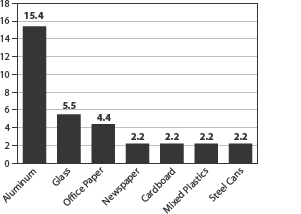

The impact of recycling depends to some extent on the material. Pound for pound, the biggest emissions reductions come from recycling aluminum. Emissions from aluminum recycling, which is a well-established industry, are a small fraction of those from virgin material production. Making a can from recycled aluminum, for instance, results in just 5 percent of the emissions of producing the same can from virgin materials. Glass and plastics recycling account for smaller overall savings, but they still significantly reduce manufacturing emissions. Aluminum, glass, and plastics, however, represent only a small part of the household waste stream, amounting to less than one-quarter of the volume of material recovered from municipal waste for recycling. (We discussed food waste in chapter 7.) The highest-volume recovered materials are paper and cardboard, which make up half of all the material recycled and composted in the United States.

Figure 8.3. Pounds of CO2e Emissions Saved Per Pound of Recycling

Each pound of waste you recycle keeps more than twice its weight in CO2e emissions out of the atmosphere. This graph shows the emissions saved by recycling one pound of material, as considered from a life cycle perspective, including reductions in the need for virgin materials and avoidance of potential methane emissions from disposal in a landfill.

Source: www.epa.gov/warm.

Americans currently recycle more than half of all the paper and cardboard they use, providing an important source of fiber to the paper industry. Today some recycled paper is even exported—usually to the paper industries of countries with limited forest resources. The mechanisms for recycling paper in the United States have become so strong that in some years they have come close to producing a glut in the paper market. The solution to that problem is simply to make sure to buy recycled paper products whenever possible.

Making paper from recycled material results in slightly fewer emissions than making it from virgin wood. But the most important benefit of paper recycling for global warming, according to estimates by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, is that it greatly reduces the need to cut down more trees. This in turn leads to more carbon sequestration in forests. Paper recycling, in other words, can mean more living trees absorbing and retaining carbon, keeping it out of the atmosphere.

UCS Climate Team FAST FACT

Only about 2 percent of total U.S. carbon emissions come from the disposal of solid waste, but recycling still makes good sense from a climate standpoint. Recycling a pound of aluminum cans instead of throwing them into a landfill can keep more than 15 pounds of CO2e emissions from the atmosphere; producing a can from recycled aluminum, meanwhile, causes just 5 percent of the emissions of producing the same can from virgin materials.

In addition to its value in lessening the need for new materials, recycling lowers global warming emissions by reducing the amount of trash, which, no matter how it is handled, creates global warming emissions. This clearly holds true with incineration because burning organic waste gives rise to carbon dioxide and other air pollution. Incinerators are common only in the Northeast and in a few other states; Connecticut and Hawaii are the only states that burn roughly half of their trash. Some facilities capture energy from the incinerated trash, which offsets their emissions, but the number of such facilities is still quite small. Across the country, roughly 80 percent of our solid waste is currently deposited in landfills. And the problem for global warming is that landfills emit methane.

Waste is packed so densely in landfills that no air circulates in them except very near the surface. Just as with the farm emissions we discussed in chapter 7, this means that landfilled organic waste decomposes without oxygen, giving rise to methane gas, which, as we've discussed, is some 25 times more potent than carbon dioxide as a contributor to global warming. Landfill methane emissions are now a little lower than they were in the 1990s because of the expansion of paper recycling and the growing use of methane capture, which is now required in many locations. Burning the methane in such efforts does yield carbon dioxide emissions, but the methane captured and burned is often used to generate electricity, reducing the need for electricity from other sources, such as coal.

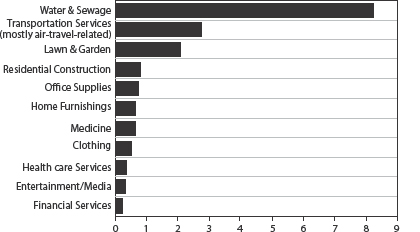

Figure 8.4. Emissions per Dollar Spent—selected Categories(Tons of CO2e per Million Dollars Spent)

This graph shows global warming emissions created per dollar spent in various categories. Ranked in this way, water and sewage together make up our most carbon-intensive expenditure.

Source: UCS modeling.

Carbon Intensity

As we have seen, one of recycling's main benefits is reducing the need for some carbon-intensive extraction of new source material. Different activities vary significantly in their carbon intensity, which can be determined by measuring the amount of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e) emitted in the activity per dollar spent on it. The most carbon-intensive activities are not necessarily the largest overall contributors to global warming emissions, but looking at the most intensive activities can help us find ways to reduce emissions.

In keeping with this book's aim to systematically approach the emissions we are each responsible for, let's take a moment to look at the most emissions-intensive categories of our expenditures. The chart ranks emissions per dollar spent, excluding transportation, home energy use, and food consumption. It shows which of our expenditures contribute most, dollar for dollar, to global warming. In the rest of this chapter, we will focus on what you can do about some of these particularly carbon-intensive purchases and activities.

Water and Sewage

As the chart shows, a basic service we all take for granted—our water supply and sewage disposal—turns out to be by far the most carbon-intensive item among those listed. When we turn on the faucet, many of us imagine the water moving naturally from a reservoir to our home, much the way the current flows in a river. But the truth is, getting municipal water to our house or apartment normally involves huge pumps that require a surprisingly large amount of electricity. If you've ever carried several gallons of water, you know how heavy it is. When you think about it that way, it is easier to understand why pumping it up to that faucet in your high-rise apartment takes so much energy. All told, the electricity consumed to move and treat the water we use represents slightly more than 2 percent of total household emissions.

That may not sound like a lot, but the electrical costs associated with your water supply make it a surprisingly energy-intensive service, undoubtedly one of the most carbon-intensive purchases you make. As the chart shows, moving and treating water produces some 8.2 pounds of carbon dioxide for every dollar spent—more than three times the carbon intensity of most other sectors.

Of course, the situation is considerably more extreme in some drier parts of the country, where communities must pump their water from distant rivers, lakes, or reservoirs. In California, for example, 19 percent of the state's electricity is used to provide water-related services, including water pumping and wastewater treatment. Water from northern California is pumped hundreds of miles, over 2,000-foot mountains, to reach consumers in southern California. The energy used to deliver water to a household in southern California is actually equal to one-third of the total electricity consumed by an average household.

The state of Arizona faces an equally extreme situation, pumping some 500 billion gallons of water per year through an aqueduct that stretches 336 miles and climbs 2,800 feet to get from the Colorado River to Phoenix and Tucson. This endeavor, called the Central Arizona Project, is the largest user of electricity in the state, consuming one-fourth of the output of a major coal plant just to move water over mountain ranges and across the desert.

UCS Climate Team FAST FACT

Water and sewage services are among the most carbon-intensive purchases you make. Water-related services account for a full 19 percent of California's electricity usage annually, for instance. That state uses one-third as much energy to deliver water to an average home in southern California as the average home there spends on electricity.

Worse yet, the costs of transporting water over great distances in places such as California and Arizona are likely to rise even higher in the coming years as some water sources are depleted and local water becomes scarcer. One anticipated effect of global warming, in fact, is that the Southwest will become even drier. Population pressures and current climate realities make it likely that municipalities will increasingly turn to even more energy-intensive technologies, such as desalination, to provide clean water to consumers. And as explained in the box on the next page, increased use of desalination will further raise the already high level of global warming emissions caused by the delivery and treatment of water.

What does the carbon-intensive nature of water-related services mean for you as a consumer? Quite simply, it means that using less water can help reduce your global warming emissions. Aside from the energy you use to heat your household water, you can save energy and reduce emissions by simply conserving water. Yes, you can take shorter showers and water your garden sparingly, but also consider onetime fixes that will make a difference for years to come: installing low-flow showerheads and toilets; investing in front-loading, low-water (and low-energy) washing machines; repairing leaking faucets and pipes; and using rain barrels to catch and store water. Taking these and other measures to lower your water use will also reduce the energy needed to purify the water, pump it to you, and treat what goes down the drain. You'll see the savings on your water bill for years to come—and you'll be reducing the sizable unseen emissions caused by generating the electricity that keeps your water flowing.

ASK THE EXPERTS

Can't Desalination Solve the Problem of Water Shortages?

What happens when the well, lake, or reservoir runs dry? When freshwater supplies are oversubscribed or exhausted, the only alternative in many areas is to use either ocean water or the brackish (moderately salty) groundwater that often results from saltwater infiltrating underground aquifers. In either case, salt must be removed before the water can be used for drinking or cooking. Desalination uses large amounts of electricity, creating correspondingly large emissions if fossil fuel is the energy source. One study estimated that if a typical southern California city switched to desalination of brackish groundwater, it would create 50 percent more carbon emissions than result from the current long-distance transport of water. Relying on desalination of ocean water, the study found, would more than double today's already sizable water-related emissions.

Around the world, more than 13,000 desalination plants currently remove the salt from some 12 billion gallons of water each day. While most of these plants are in oil-rich Middle East nations, they are becoming more common in many locales, despite their high economic and energy costs. One major ocean desalination plant is operating in the Tampa Bay region of Florida, which has experienced water shortages due to rapid residential and commercial development and agricultural demands for water. An even bigger ocean desalination plant is planned in Carlsbad, near San Diego in southern California.

Even using the most energy-efficient means currently available, these desalination plants emit about a ton of global warming emissions for every 132,000 gallons of usable water they produce. This means that current desalination efforts worldwide already account for at least 33 million tons of carbon dioxide per year—a number that makes water conservation an even more important priority in these areas to forestall global warming.

Yard and Garden

Even though lawn and garden activities account for less than 1 percent of an average American's global warming emissions, yard work ranks among the most carbon-intensive activities we engage in. If you have a big yard and, especially, a large lawn, your emissions may well be above average in this category. If so, this could be an area ripe for making adjustments.

A life cycle analysis of lawn and garden care in Seattle found that the leading source of global warming impacts in this sector is the use of fertilizers and pesticides. As discussed in chapter 7, these chemicals are one cause of high emissions in agriculture. Many Americans use the same products on their lawns at rates (per acre) similar to those of farms. The biggest global warming impacts from lawn and garden care are the upstream industrial emissions in the production of these chemicals. However, as in agriculture, the potent heat-trapping gas nitrous oxide (N2O) is released in small amounts directly from lawns after nitrogen fertilizer is applied. Reducing or eliminating fertilizers and pesticides can cut lawn-related emissions in half. Of course, carbon emissions are just one problem with lawn chemicals; some of them are quite damaging to the environment and well worth avoiding for that reason as well.

The second most important source of lawn and garden emissions, the Seattle study found, is weekly lawn mowing with a gasoline-powered mower. Switching to an electric mower or, even better, a classic push mower, the study found, could significantly reduce or eliminate these emissions. Using less water can also result in further indirect savings.

Composting yard waste may provide a climate benefit, depending on how the compost is used. It is most beneficial when it replaces or reduces the need for chemical fertilizer, thus eliminating the emissions from producing and using a carbon-intensive product. Compost can also help by increasing the retention of water and carbon in the soil. For more ambitious composters, food waste composting, as discussed in chapter 7, also offers a way to reduce landfill methane emissions.

In addition to adopting more climate-friendly lawn-care practices, those who are interested can convert their yards from a net global warming problem to a net gain in the fight against a warming planet. This strategy, however, means at least cutting back on the lawn, if not replacing it altogether.

UCS Climate Team FAST FACT

The biggest global warming impacts from lawn and garden care are the upstream impacts from the production of chemical fertilizers and pesticides. Reducing or eliminating your use of them can cut your lawn-related emissions in half.

The fact is, a uniform expanse of green grass is a monoculture, an unnatural phenomenon maintained only by waging constant war against nature, with water, fertilizer, and herbicides. The ideal American lawn began as an imitation of lawns and meadows found on estates in England and France. But the grasses native to those countries—including Kentucky bluegrass, which was originally imported from England—are easy to grow only in certain parts of the United States, mainly in the Northeast and Midwest. In other parts of the country, you can save water and lower your use of lawn chemicals, as well as your carbon emissions, by cultivating plants native to your area. Planting a natural lawn of indigenous local plants, which will look more like a wild meadow than a golf course, can complement your house in a climate-friendly way.

Even better for global warming, you can plant trees or shrubs to lower your overall carbon profile. Trees and shrubs sequester more carbon than a lawn does and are a significant improvement for your carbon footprint over a chemically treated lawn. Plus, strategically placed trees can shade your home from hot summer sun and shield it from winter winds, further lowering your carbon emissions from heating and cooling.

Construction and Remodeling

Just as you can turn carbon liabilities into assets by changing what you grow in your yard, you can achieve similar results with many of your expenditures. Let's look briefly at one last sector that is both sizable in terms of overall emissions and relatively carbon intensive: construction and remodeling. Construction of new homes and remodeling of old ones account for about 4.4 percent of the average American's total global warming emissions. If you are that average American, you and your spouse or partner will buy a newly built house—or build one yourselves—once in your lifetime. If you already own a home, you may find yourself working almost continuously on renovation or remodeling projects, large and small.

Most residential construction emissions result from that once-in-a-lifetime purchase of a new house. But homeowners’ ongoing renovations also add up. For the purpose of discussion, we've lumped new construction and remodeling together because they involve such similar activities. If you are building a house or putting on a major addition, your choices about building materials will obviously affect your emissions. For houses with the same heating and cooling requirements, those built with more wood and less steel or concrete will have lower emissions related to construction (taking into account the industries that supply the materials). And, as we have discussed, wood harvested sustainably can lower your emissions further.

When considering the global warming impacts of construction and remodeling, the first rule is the simplest one: buy or build no more house than you need; a larger house means more carbon emissions. One study found that even a poorly insulated house of 1,500 square feet uses less heating and cooling energy than a well-insulated house of 3,000 square feet—although the best of all for reducing your carbon footprint, of course, is a well-insulated small house.

Beyond that, however, as we discussed in chapter 5, keep in mind that construction choices determine our future needs for heating, cooling, and other uses of energy in our homes for decades to come. That's why construction and remodeling offer great examples of how we can turn a global warming problem (the emissions caused by home construction) into part of its solution (the energy savings we can lock in for the lifetime of the house).

When designing a new house or remodeling an existing one, consider all the alternatives discussed in chapters 5 and 6 for lowering your heating, cooling, and lighting emissions. It is more effective, and cheaper in the long run, to design a house with high-efficiency heating and cooling systems, ample insulation, maximum use of natural light, and other energy-saving features than to make these changes later. One big obstacle to progress in energy-efficient construction is that real estate developers tend to leave out such features in order to keep house prices low—even though the additional costs of constructing a high-efficiency house will pay for themselves many times over in lower energy bills.

As we will discuss further in chapter 10, interest in green building is spreading rapidly. More and more contractors are learning about and adopting green techniques, for commercial and government buildings as well as for residences. This area presents great opportunities for the nation to reduce its overall carbon emissions. Build or remodel with greatly increased energy efficiency and you will make up many times over for whatever emissions you create in the construction process with reductions in future emissions from energy usage.

A Word about Voluntary Carbon Offsets

No discussion of the emissions associated with the goods and services we buy would be complete without mentioning voluntary carbon offsets. The idea is to pay an organization to engage in some carbon-reducing activity, such as building renewable energy capacity or planting trees, to compensate for—or offset—the emissions created in a given activity. As we discussed in chapter 4, if you are flying a long distance, you can purchase carbon offsets equal to the emissions caused by the flight. Carbon offsetting is increasingly used by corporations and nonprofit organizations to compensate for the fact that many staff members need to fly to meetings and hearings as part of their jobs or cause global warming emissions in other unavoidable ways.

While the idea of—and the market for—carbon offsets is now well established, and it's easy to find a reputable organization that sells offsets, it is worth remembering that offsets cannot replace the good you do by reducing your own emissions. It's fine to support renewable energy and tree planting, but, however worthwhile such efforts are, they don't alter the fact that a megawatt of energy not used is the surest carbon reduction strategy of all.

Still, it can be argued that carbon offsetting will help us make the transition to a more sustainable future. For those interested in purchasing carbon offsets, the best bet is to start with a reputable nonprofit agency that offers, rates, or certifies offsetting options. Among the possibilities are the Verified Carbon Standard (www.v-c-s.org), based in Washington, DC; the Climate Action Reserve (www.climateactionreserve.org), based in Los Angeles; Green-e (www.green-e.org), based in San Francisco; and the Gold Standard (www.cdmgoldstandard.org), based in Switzerland.

Getting to 20

As noted at the beginning of this chapter, the goods and services we buy do add up to a sizable proportion of our emissions profile. Unfortunately, however, about half of these emissions are outside our immediate control, and the other half are spread across so many categories that it is hard to make many deep reductions in this area. Still, all of us can shave a few percentage points off our total emissions profile by cutting back on overall purchases of new products and recycling what we use. We can also pay particular attention to our purchases and behavior in some of the most emissions-intensive activities, such as water use, construction and remodeling, and yard care. A good rule of thumb in this category is to try, whenever possible, to think about long-term returns and environmental benefits from your purchases. When there are highly efficient options for appliances, equipment, and vehicles, for instance, it almost always makes sense to junk energy hogs in favor of the most efficient models you can afford.

The Bigger Picture

We—re at the end of the story of how our individual choices and purchases affect global warming. In this and the preceding chapters, we have covered the largest slices of our consumer spending, described the most carbon-intensive things we do and buy, and suggested alternatives wherever possible. With this information, you should be able to relatively easily reduce your global warming emissions by at least 20 percent in your first year and probably by a lot more in the years to come.

By cutting your emissions by 20 percent or more, you've done several positive things. you've demonstrated that significant reductions are well within everyone's grasp, that each of us can make better personal choices without disrupting our daily lives. Because you're sensible, you've shown that this change can be made cost-effectively and can even save you money. But perhaps most important, you have taken a personal step that the entire nation must take within the next several years if we are to preserve a healthy climate for our children.

Bravo.

You're not off the hook yet, though. Our personal choices and purchases matter a great deal, but the truth is, we can't shop our way to a stable climate. And, as important as our individual choices are, none of us can stop global warming alone. So at this point, rather than exploring the impacts of ever-smaller consumption choices, let's turn to the bigger questions about how our society as a whole responds to the issue of global warming and where you fit into that picture.