Nefertiti herself must have been an unusually beautiful and graceful woman.1

James Baikie (1926)

The Nefertiti bust is the only substantially complete work of art to be recovered from Thutmose’s compound. Standing 48cm (19in) tall and weighing a hefty 20kg (44lb), it shows the head, neck and an area extending from the clavicle to just above the breasts of a woman whose hairless head is topped by a crown, and whose long, slender neck is encircled by a colourful floral collar incorporating petals and small fruits. The woman has a narrow face with prominent brow ridges and cheekbones, a long nose and full lips. Her eyes are almond shaped, her brows well defined and her chin firm. The bust has been created from carved limestone (calcium carbonate) – an unexceptional stone – coated with layers of gypsum plaster (calcium hydroxide) and painted, so that the core itself is invisible to the naked eye.

The bust is uninscribed, and so our identification of its subject is based purely on our recognition of its tall, flat-topped crown as a headdress that is unique to Nefertiti. We see this crown repeatedly in Amarna art and sculpture, and every time we see it we identify the wearer as Nefertiti, just as we identify any Amarna woman wearing large, round earrings as Kiya. This identification of people by their accessories is not ideal; if we were ever to discover that Nefertiti and Kiya shared their wardrobes we would seriously have to reconsider many of our interpretations of Amarna scenes. The extent to which we automatically associate this particular crown with Nefertiti was made clear to me when artist Aakheperure sent me a sketch showing me wearing the same crown, and I did not instantly recognise just who was being depicted. Even my family, who see my face far more often than I do, had a moment’s hesitation before seeing me, rather than Nefertiti.2

The Berlin version of Nefertiti’s tall crown is dark blue, with a uraeus (now missing) rearing over the forehead and a multicoloured band or ribbon circling the crown and tying at the back. Two colourful ribbons hang from the nape of the neck; these have an undulating outline that suggests they were made from a flimsy material, and this is confirmed by 2D scenes that show the loose ribbons fluttering in the breeze. The crown fits, bonnet-style, close to the head with a gold forehead band and back band, and is usually worn without a wig. Other images show the same basic crown decorated with varying arrangements of discs and ornaments. The origins of the crown are obscure, although its shape and colour suggest that it may have developed as a female version of the blue war crown worn by many of Egypt’s kings.3 Akhenaten himself favoured a rather high, narrow version of the blue crown, which he often decorated with stylised discs or multiple uraei, and this is what his own bust is wearing. In shape, Nefertiti’s tall crown is reminiscent of the headdress worn by Tefnut, and by Tiy as a cartouche-bearing sphinx. After Nefertiti’s death Mutnodjmet, consort to Horemheb and, perhaps, sister to Nefertiti, occasionally wears a crown with a similar silhouette.

Both Nefertiti and Akhenaten exhibit a variety of crowns, leading us to assume that while crowns in general separated the royals from their subjects, each crown was invested with its own specific symbolism and meaning. At Thebes, at the start of her husband’s reign, we see Nefertiti wearing the single or double uraeus over a long, heavy wig, which was often topped by the tall feathered crown ornamented with the cow horns and disc introduced by Tiy. By the time she moves to Amarna Nefertiti is also wearing the tall blue crown, which she will wear with increasing frequency. Another innovation at this time is the ‘cap crown’; a close-fitting bonnet decorated with a uraeus and a ribbon or band at the base, which is sometimes mistaken for the tall blue crown. The cap crown will also be worn by queens Meritaten and Ankhesenpaaten (as Tutankhamen’s wife Ankhesenamen) and, in post-Amarna times, will be worn by Ramesside kings.4 Nefertiti occasionally wears the khat head-cloth, a bag-like head cover usually worn by kings but also worn by Tiy, and by the goddesses Isis and Nephthys. We never, however, see Nefertiti wearing Akhenaten’s crown, and our only view of her wearing anything resembling a king’s crown comes from the Amarna tomb of Panehsy.5 Here Nefertiti wears a khat head-cloth topped by an ornate atef crown; a crown that, during the New Kingdom, incorporated ostrich feathers, ram and bull horns, a solar disc and multiple uraei. She stands behind a larger-scale Akhenaten, who wears a nemes head-cloth and an even more elaborate atef including two extra cobras and three additional falcons.6 Akhenaten’s crown is larger, has more elements, and appears far more regal than Nefertiti’s; there is nothing here to suggest that the king and queen have equal status. This whole scene is, however, curious, as the atef was primarily associated with the cult of Osiris, a god who was not welcome at Amarna.

Important though they obviously were, not one of Egypt’s crowns has survived. This could be explained by the fact that we have only one substantially intact royal burial representing the entire 3,000 years of the dynastic age. It could be that Tutankhamen’s tomb is unrepresentative, and that other royal burials were packed floor to ceiling with different types of royal crowns. Even so, it is curious that all the crowns, along with all trace of their manufacture, should entirely vanish. It may be that we are overestimating the numbers. That there was just one set of crowns, passed from king to king and consort to consort as the dynastic age progressed, or that each king and queen had a personal set of crowns which was destroyed at their death. However, rather than attempt to track the missing crowns, we should perhaps be asking whether these crowns ever existed in the first place. Egypt is, after all, a land where art is writing and writing is art. Could the crowns simply be symbols of authority and religious power? The equivalent, perhaps, of the nimbus or circle of light and flame which artists from various cultures have traditionally used to distinguish holy and sacred people, rulers and heroes. This would certainly explain the elaborate structure of a crown such as the atef, which, were it made of metal or leather, would have been difficult to manufacture and heavy to wear. A parallel can be drawn here with the ‘perfume cones’ which are often seen on the heads of banqueters in New Kingdom tomb scenes. Early Egyptologists identified these as party hats made of scented fat. The theory was that they would melt in the heat of the banquet, releasing a pleasant odour and a cooling trickle of grease. This, however, would have been very difficult to accomplish in a land without refrigeration, and Egyptologists today are more inclined to read the cones as symbols representing scent, or happiness, or maybe death.7

Because the bust has a smooth base that allows it to stand firm, we can be confident that it is a complete artefact and not simply a head that has snapped off a larger statue. Instinctively, this seems wrong. Everything that we know about Egyptian art tells us that the sculptor would always show his subject complete. The creation of a bust – a bodiless, limbless head – would have been dangerous because it left its subject open to the possibility of an uncomfortable eternity spent as a disconnected head. Yet Thutmose’s workshop yielded two completed part-royals – the Nefertiti bust and its companion Akhenaten bust – plus what appears to be the lower part of a third bust, while the Louvre houses a second Akhenaten bust.8

Borchardt recorded the finding of the Akhenaten bust in his official excavation diary:

In the corner room of the house, at the NE corner … there is a life sized coloured royal bust, broken into 5 pieces, not quite complete. Face unfortunately quite battered. The following preserved: chest, piece of arm, neck, face and wog [crown].9

Later that same day, when Nefertiti emerged virtually intact, he regarded the two busts as a pair.

The damage to the Akhenaten bust appears to have been deliberate rather than accidental. Although it has been suggested that the bust was smashed before it was placed in the pantry, this raises the question why anyone would have bothered to save the pieces.10 It is possible that they were collected and stored by someone loyal to Akhenaten, or by someone with a personal devotion to this particular statue, but these seem unlikely explanations, as whoever filled the pantry was preparing to abandon Amarna at a time when Akhenaten himself no longer served as a conduit to the divine. Friederike Seyfried, current director of the Egyptian Museum and Papyrus Collection in Berlin, has pointed out that the bust shows small, neat chisel marks; evidence, perhaps, that Thutmose’s workmen systematically and carefully removed the valuable gold that had been applied as part of the finish, before placing it in the pantry. This indicates that the bust was attacked some time after Thutmose’s departure, by those who scoured Amarna looking for images of the king. Nefertiti’s bust, further back in the room and less obvious, simply went unnoticed.11

If we look outside Amarna we can see that, while the creation of a bodiless head was not without precedent, it was rare. To find Egypt’s earliest examples we have to go back over 1,000 years to the Old Kingdom when, for a short period of time, the burial shafts of some elite mastaba tombs included what Egyptologists have termed ‘reserve heads’: unpainted and uninscribed sculpted heads and necks whose flat bases allow them to stand upright.12 These heads, a mixture of male and female, are all bald, presumably because they have removed their wigs to reveal their shaven heads. They appear so lifelike that it has been suggested that they are individual portraits, rather than off-the-peg purchases. While most of the heads are carved from fine limestone there are also crude examples incorporating moulded plaster, and even two made from mud. Of the thirty-one known reserve heads, twenty-seven have been recovered from the Giza cemetery; they mostly date to the Fourth Dynasty reigns of the Great Pyramid builder Khufu (c.2589–2566 BCE) and his son Khaefre (c.2558–2532 BCE). Many show damaged ears and several have an unexplained cut down the back of the head.

Their provenance and restricted time-span offer a clue to their purpose. All the reserve heads were recovered from tombs that, although they had a small offering chapel attached to the solid superstructure, did not have a room large enough or secure enough to house a complete statue. As mummification was at a very early stage during the Fourth Dynasty, the survival of the corpse could never be guaranteed. Yet the survival of the corpse in a recognisable state was already regarded as essential for the continued existence of the soul after death. We can therefore speculate that the reserve heads, although not ideal, were provided to serve as an emergency home for the bodiless soul. When the mastaba tombs developed secure interior chapels the reserve heads were replaced by full statues. Although Nefertiti’s bust is also hairless, and has damaged ears, it seems highly unlikely that it is the Amarna equivalent of a Fourth Dynasty reserve head. Nefertiti was well represented at Amarna, at Thebes, and presumably elsewhere in Egypt. If her soul ever needed to find a substitute body, it would be spoiled for choice. More specifically, the bust is one of a pair that presumably had an identical purpose. We cannot be certain that Nefertiti died before Amarna was abandoned but we can be certain that Akhenaten did; we know that he was buried in the royal tomb. We would have expected his reserve head – if that is what his bust was – to have been included in his tomb.

The reserve heads were not the only limbless, bodiless sculptures to be buried with the dead. Tutankhamen’s tomb has provided two examples. From the debris blocking the passageway leading to the anteroom came a near life-sized wooden, plastered and painted head representing Tutankhamen as the sun god Re emerging from a lotus blossom at the beginning of the world.13 This piece tells a well-known story and, although it bears Tutankhamen’s features, it is not technically a representation of the king but of the god who bears the king’s face. Of more relevance to our search for a parallel to the Nefertiti bust is a wooden, plastered and painted life-sized model of an armless upper body found in the antechamber. The model is dressed in a simple white robe and wears a flat-topped crown decorated with a single uraeus. Egyptologist turned journalist Arthur Weigall caught a glimpse of the model as it was carried from the tomb, and identified it as Tutankhamen’s wife Ankhesenamen (formerly Ankhesenpaaten) wearing a crown similar to that worn by her mother Nefertiti.14 His identification was picked up by his fellow journalists, and the model entered the public imagination as a mystery woman:

wreathed in a glowing Mona Lisa smile – a smile which captivated the few spectators who remained at the tomb … The lips are full, the eyes dark and large, but the whites of the eyes are very pronounced. Finally the cheeks are almost certainly those of a young girl.15

Howard Carter took a more practical approach, identifying the model as a male mannequin – a replica Tutankhamen – used to display the king’s clothes and jewellery:

The most novel, perhaps, among all the antiquities seen today was a wooden dummy upon which it is believed Tutankhamen tries his tunic and other vestments, after the fashion of a modern dressmaker. Mr Henry Burton, of the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art, who is an enthusiastic member of Mr Carter’s staff, advanced the opinion that Tutankhamen was a man of fashion, scrupulously exact in the fit and hang of his garments.16

While Carter’s identification seems unlikely – surely it would have been more useful, for a kilt-wearing king, to create a full body mannequin with legs but without an integral crown, if this was its purpose? – no one has been able to suggest a better one. All that we can conclude is that the ‘mannequin’, whatever its purpose, was not considered threatening to the king’s well-being after death.

Although most stone sculpture is inscribed with the name and titles of the subject, Nefertiti’s bust is silent. It may simply be that Nefertiti needed no inscription – that her unique crown made her identity obvious to all – but it could be argued that her bust was not inscribed because it was intended to be just one element in a much larger, composite sculpture. Egypt’s artists did not traditionally create stone statues with multiple parts, but Thutmose’s Amarna compound has yielded enough complete or near-complete stone body parts, mainly heads, but also arms, hands, feet and part of a stone wig, to show that his sculptors were experimenting with this style.17 They were not the only ones. A neighbouring sculptor’s workshop (O47,16a and 20) yielded an unfinished quartzite head of Nefertiti which would have formed part of a composite statue, while a third workshop to the south of the Thutmose workshop (P 49.6) yielded an arm and a pair of hands.18 In a city with an insatiable demand for royal statuary, this made good commercial sense. A composite statue could be manufactured quickly by different experts using relatively small blocks of stone, then transported with relative ease and assembled in situ. As an added bonus, the sculptor would be able to match individual body part to their ideal stone. So, yellow, brown or red could be used for hands, feet and heads. Black could be used for hair, eyebrows and occasionally skin, while white could be used for bodies draped in white linen. A statue made in this fashion would retain its original colours in a way that a plastered and painted statue would not. At the same time, a limestone statue with hard stone extremities would be both easier and cheaper to make than an entirely hard stone statue. However, in spite of these obvious advantages, it seems that the experiment failed, as the manufacture of composite statues largely died out at the end of the Amarna Period.

One piece recovered from the Thutmose workshop is of particular interest here. A brown quartzite head, unfinished, unpolished and still decorated with the black ink lines that would have guided the sculptor, bears a strong facial resemblance to the Nefertiti bust.19 This head was clearly not created as a stand-alone piece; it would have been part of a composite statue with, perhaps, a blue faience crown attached to the peg which survives on the top of the head. Although there are signs of faience working within the Thutmose workshop, there is no sign of the crown. The bodies and legs which would have made the Thutmose limb collection whole are also missing – perhaps they were made elsewhere – and, as not one composite stone statue has survived the vandalism that occurred at the end of the Amarna Period, our understanding of this innovative technique is based on theory rather than observation. We can see that heads created as part of a composite statue usually have a rounded tenon or projection at the base of the neck; this would have slotted into a mortise or hole on the torso. The joint would then be glued firm using a mixture of resin and powdered stone coloured to disguise the seam. As the wig or crown would have been a separate piece there is often a second tenon on the head. However, the Amarna princesses, whose exaggeratedly egg-shaped heads were not hidden under wigs or crowns, lack this second tenon.

The mortise-and-tenon would not have been the strongest joint to use when creating a large, heavy, stone statue. It was, however, the joint already being used in the creation of wooden statues, suggesting that Thutmose’s workforce copied their technique unvaryingly from the carpenter’s workshop. We can draw a useful parallel here with one of the Amarna Period’s best-recognised ‘portraits’: a small wooden head of Tiy recovered from Gurob, the site of an extensive Eighteenth Dynasty harem palace.20 This head measures just 22.5cm (9in) including its tall headdress, and is carved from three different types of wood. Unusually, it allows us to see Tiy not as a stereotypical ageless queen, but as a real, elderly woman with downturned lips, heavy eyelids, almond-shaped eyes and deep lines running from her nose to her mouth. She currently wears a bobbed, round wig made of linen and covered in blue glass beads, but it is clear that her head was remodelled in antiquity, as beneath this wig we can see remains of an earlier bag-like khat headdress, a pair of gold earrings and four golden uraei. Confirming that the head is part of a composite statue, it has a neck tenon which would have allowed it to be inserted into a torso, while a second tenon, on the head, allowed the attachment of a modius headdress and tall double plumes which, once separated, have recently been reattached by museum conservators. The headdress links Tiy with the goddesses Hathor and Isis and suggests, perhaps, that either the statue or the queen has been deified.

The care lavished on Tiy’s small head dispels any suggestion that a wooden statue was considered a cheap or inferior option. Beyond confirming the importance attached to the statue, the significance of the queen’s change in regalia is hard for us to assess, but it is possible that it coincides with Tiy’s developing role in Akhenaten’s religion. He would not be the first king to use his mother to stress a very personal link with the gods; indeed, his own father, Amenhotep III, had used the walls of the Luxor Temple to tell the story of his divine birth as the son of Amen-Re and the secondary queen Mutemwia. If Akhenaten felt himself to be the son of a divine being his mother, as a woman who has communicated with that divine being, must surely have been allowed her own share of divinity.

Although we know that Thutmose’s workers were experimenting with the composite style, it is unlikely that the Nefertiti bust was ever intended for insertion into a torso. The presence of the finished shoulders, the absence of a tenon for attachment and the fact that the crown is integral to the piece all suggest that it is a work of art in its own right. Nevertheless, a highly controversial modern art installation has shown that it would, theoretically, have been possible to unite the bust with a body. In 2002 the artists known as Little Warsaw (András Gálik and Bálint Havas) developed The Body of Nefertiti for display in the Hungarian Pavilion at the 50th Venice Biennale (2003). Their inspiration was the redisplay of popular and historical symbols in contemporary contexts, establishing a connection between the present and the temporality of art and so demonstrating the continuity of culture. Nefertiti, as perhaps the best known symbol from the ancient world, was an obvious subject for their work. They did not see her primarily as a symbol of Africa, but of Europe:

This statue is one of the important sources of European cultural history and sculpture, even though it was created outside the continent. Its outsider position adds further meaning to the project of completing: this 3000 years old model has been contributing, ever since it was found and put on display, to the European ideal of beauty.21

Their original intention was to create a metal body, unite it with the bust and display the composite statue in Venice. However, the museum authorities refused permission for the bust to travel. Undaunted, Little Warsaw created a life-sized, and rather modern looking, bronze body for Nefertiti. At first sight their body seems to be naked, though it is actually wrapped in a diaphanous linen robe. The body was taken to Berlin, where it was placed near the case displaying Nefertiti’s head. Then, for a few hours on 26 May 2003, the ancient head became one with its modern body:

The idea was to create a headless statue that alludes to Nefertiti but is a distinct and separate work of art … the headless sculpture in Venice holds the memory of the earlier encounter with the Egyptian head in Berlin.22

This brief union was filmed, and the film subsequently displayed alongside the headless torso in the Hungarian Pavilion in Venice.

It can have come as no surprise to anyone that the decision to allow the bust to be used in this way, although fiercely defended by the museum as a legitimate artistic experiment, sparked angry demands that it be returned to Cairo, where Nefertiti would be treated with appropriate respect. Any surprise came from the fact that the outrage centred less on the fact that the experiment may have put a priceless antiquity in physical jeopardy, and more on the fact that the display of Nefertiti’s ‘naked’ body was considered disrespectful. Mohammed al-Orabi, Egyptian ambassador to Germany, summed up the feelings of many of his outraged countrymen when he stated that the installation ‘contradicts Egyptian manners and traditions. The body is almost naked, and Egyptian civilisation never displays a woman naked.’23

Can we learn anything practical from the Little Warsaw installation? We know that the Egyptians were making copper statues as early as the Second Dynasty reign of Khasekhemwy (c.2686 BCE), with the first surviving metal statues dating to the Sixth Dynasty reign of Pepi I (c.2321 BCE).24 Little Warsaw’s work leaves open the possibility that Nefertiti’s bust may have been intended as part of a composite, mixed-material sculpture. But with no parallels, and absolutely no evidence to support this possibility, it seems highly unlikely.

If not part of a composite statue, could the bust have been a teaching aid? Nefertiti’s missing left eye could then be explained as a demonstration which was halted before it was complete. The idea of a dedicated teaching aid leaves us with the curious and in many ways unsatisfactory image of Thutmose’s students watching, passive, as he teaches his skills in a classroom situation. In reality, it seems highly unlikely that anyone would waste precious time and resources in this way; in Egypt, apprentices learned on the job. More credible is the suggestion that the bust was an artist’s model or template, used to guide Thutmose’s workers. This fits well with what we know of established working practices; the artists who decorated Egypt’s tomb and temple walls, for example, routinely worked from patterns and guides which ensured the consistency of their work. By providing his workers with an approved image to copy, Thutmose could be confident that all his Nefertitis would look alike, and that all would be acceptable to the king.25

We can push this speculation further. We know that the Amarna elite were expected to perform their personal devotions before carved statues or stelae depicting the king and queen. We also know that Thutmose, by virtue of his role as the creator of the royal image, was in constant contact with the palace administration. His ownership of a chariot suggests that he may even have been one of the favoured few who accompanied the royal family as they processed along the royal road, presenting themselves to their admiring subjects. He must surely have had his own, conspicuous, royal icons. Could the Akhenaten and Nefertiti busts – which may indeed have served as models for the workforce – have been Thutmose’s personal devotional aids? This would have been unusual, but Thutmose was an atypical man living in extraordinary times, and he had access to resources that others lacked.

Although there is no precedent for royal busts being used as cult objects in private contexts during the Eighteenth Dynasty, private busts were not unknown at this time. Approximately 150 so-called ‘ancestor busts’ have been discovered at sites throughout Egypt, with the majority coming from the Theban workmen’s village of Deir el-Medina, and just one coming from Amarna. They range in date from the earlier Eighteenth Dynasty to the Nineteenth. These, our final example of deliberately manufactured disembodied heads, are images of (we assume) deceased family members. The majority take the form of a head approximately 25cm (10in) in height, with or without a wig, set on a base. Several double busts are known; these invariably show one head wearing a wig and one without. It is difficult to be specific about gender, but it is probable that the majority of the busts are female. Most of the busts are made from limestone, but there are also examples made from sandstone, granite, wood and clay. While many still bear traces of their original paint, only four are inscribed. The ancestor busts do not resemble living people in the way that the Nefertiti and Akhenaten busts do; instead, they resemble the upper part of an anthropoid coffin. It is generally accepted that they were designed to be set into niches in the village houses and tombs, where they served as the focal point for ancestor worship.26

The addition of the fine layer of gypsum plaster to the limestone core allowed the artist to create the fine definition of muscles and tendons obvious in Nefertiti’s neck, to add subtle creases around her mouth and under the eyes, and to emphasise her cheekbones. This turned Nefertiti from an unrealistically smooth being into a mature woman with considerable allure. These humanising creases and wrinkles were not, however, obvious to early visitors who, forced to view the queen under the strong, direct light provided by the museum, saw the brash and flattened appearance identifiable in many early photographs. To some, this idealised face with its heavy eyeliner, groomed black brows and defined red lips looked excessively made-up rather than elegant. Ironically, the replica busts which could be purchased from the museum and displayed at home under less harsh conditions, in many ways appeared more ‘real’ than the original.

Then, in 2001, when the bust was being moved within the Egyptian Museum in Berlin-Charlottenburg, it accidentally stood for a time in semi-darkness after a spotlight failed. This prompted the museum staff to start experimenting, and they quickly discovered that lighting the bust obliquely from behind increased Nefertiti’s apparent age by approximately ten years. The muscles and tendons in her neck, the lines running from her nose to the mouth, the indentations at the side of her mouth, the wrinkles under her eyes and her slightly hollowed cheeks were all emphasised. In the words of Dietrich Wildung, who as Director of the Egyptian Museum and Papyrus Collection in Berlin had more opportunity than most to gaze at Nefertiti’s face: ‘the pretty model became a beautiful woman, aged by some years and more attractive than ever before’.27 This more mature Nefertiti is the version of the bust that the museum now strives to present to its visitors.

In 1992 the bust was scanned using computed tomography (CT). This revealed that, while most of the bust was made from stone covered by a layer of plaster only a millimetre or two thick, the shoulders and the back part of the crown had essentially been created from plaster. In 2006, with more advanced technologies available, the bust was rescanned.28 It was now possible to see how the plaster layer had been moulded to correct or personalise the well-made but somewhat generic stone head beneath, so that, for example, a slight bump on the stone nose was smoothed out to give a straight profile. The restoration work done to the crown and shoulders by the ancient craftsmen was apparent, as was more modern restoration performed between 1980 and 1984 on the thorax. These results are of great importance as they allow the museum’s conservators to understand which areas of the bust are the most delicate, and the most susceptible to damage.

The Nefertiti scans were released to the general public, and received good coverage in the world’s press, who seized on the ‘fact’ that Nefertiti apparently had a hidden face covered in irregularities. As Bernhard Illerhaus and his colleagues noted after analysing and discussing the data generated by the two Nefertiti CT scans, a calculated CT image cannot be regarded as a portrait. Nevertheless, headlines such as ‘Beauty of the Nile Unmasked: Wrinkles and All’ and ‘Nefertiti’s Real, Wrinkled Face Found in Famous Bust?’ proliferated, and soon after came the acceptance that the addition of the smooth outer layer was the ‘ancient-day version of photo-shopping’.29 The face beneath the plaster must have been hidden on the queen’s orders because it was too realistic, too wrinkled and, basically, too old to be seen. This is, of course, a huge assumption. The twenty-first-century press may believe that older women should be ashamed of their appearance, but we have no evidence to suggest that the ancient Egyptians felt the same way. In a land where few grew old, old age was not automatically linked to decay and death, and the wisdom of age is more likely to have been admired than denied.30 If we take a close look at the stone and plaster heads recovered from the Thutmose workshop we see a lifelike combination of eye bags, nasolabial folds (the crease running along the edge of the cheek, connecting the corner of the nose to the mouth) and lines at the corners of the mouth. Even the princesses, who by no one’s definition can be considered old, have lines at the corners of the mouth.

We don’t know how old Nefertiti was when her bust was created. The face shows none of the unnatural angularity of earlier Amarna sculpture, and on this basis alone we can tentatively date it to Akhenaten’s regnal year 12, or later. We know that by this point in Akhenaten’s reign Nefertiti had already given birth to the six full-term children who are depicted in a dated scene in the Amarna tomb of Meryre II; she could, of course, have had other children (boys?) and failed pregnancies. While she could in theory have been less than twenty years old, it seems reasonable to assume that she was several years older, though not many decades older as her youngest daughter, Setepenre, was still a baby. Whatever her age, it is unlikely that she had the smooth albeit slightly wrinkled complexion of the Berlin bust. Nefertiti’s life was more pampered than many, but she could not have avoided illnesses and minor accidents that would have marked her skin and, given the lack of dental hygiene combined with the elite liking for breads flavoured with honey, we may speculate that her teeth were not in good condition either.

Of relevance here is a small unfinished limestone statuette of Nefertiti, just 40cm (16in) tall, discovered in fragments in Thutmose’s pantry.31 This version of the queen has facial grooves and a downturned mouth which make her look tired or old, although it is entirely possible that the sculptor would have added a layer of painted plaster which would have given her a smoother and more youthful face. Nefertiti wears the cap crown and rounded earrings, leaving us with the faint possibility that this may be Kiya, although the cap crown and square-jawed face strongly suggest Nefertiti. She stands straight with her hands by her side, and her unpleated linen dress clings tightly to her body, giving the impression that she is naked. There are signs that her shoulders would have been covered by a linen shawl; she wears thonged sandals on her feet. Through the dress we see that her hips are wide, her stomach rounded, her breasts small and ‘slack’.32 She has the body of a woman who has borne children. There is no reason to assume that Nefertiti was ashamed of this body and, indeed, it would appear that neither Nefertiti nor Tiy was afraid of being presented as an older, experienced woman; the equivalent to the plump elder statesmen who occasionally appear in Egyptian art.

It is therefore unfortunate that the image of the smooth and slightly artificial Nefertiti is the one that persists in the public imagination. It is this image which has led to the modern association of Nefertiti with plastic surgery; there are Nefertiti clinics throughout the Western world, while the ‘Nefertiti face lift’ is promoted as a lower face, non-surgical option for those who might wish to ‘tighten up sagging and wrinkled skin while erasing a few years’.33 Even more unfortunate, perhaps, are the more than fifty surgical procedures (including eight nose jobs, three chin implants and three facelifts) which have transformed a British woman, Nileen Namita, into a living version of the Berlin bust, at a conservative cost of £200,000. Nileen believes that she is a reincarnation of Nefertiti: ‘being Nefertiti is my destiny … Suffering is part of being Nefertiti. She suffered too, under the pressure of being queen.’34

Nileen is an extreme example of women who choose to associate with Nefertiti through their skin. Others, less extreme, create a connection with the bust, and through the bust with Nefertiti herself, via jewellery or skin art. Egyptology student Robin Snell explained to me the very personal relationship that can exist between a modern American woman and a long-dead Egyptian queen:

My Nefertiti tattoo is large, six inches long and five and a half inches wide. Its placement is at a place where it cannot be easily hidden. I want it to be seen. My tattoo artist knows I take them very serious so she actually studied Nefertiti before starting the piece.

When I lived in the San Francisco Bay Area I ran a very large domestic violence agency for battered women and children. As a director of intervention services, I worked with staff and clients in the role of a powerful woman who walked the walk and talked the talk. I worked with my partners and my husband, and raised and loved my son. That’s my mirroring with Nefertiti. She ruled with her husband, sometimes ruled alone and loved her children. Many around the world think she’s the perfect beauty but looking at her closely, the eye is gone, pieces of the ear broken off, very important to me. We must look at each other deeper to see the strength. Behind her, we put a sunset/sunrise to acknowledge Nefertiti will always be in front, supported forever by Ra with the outline of a falcon on top of an ankh … Nefertiti and I should wear a T-shirt that states, ‘Well-behaved women rarely make history.’35

Occasionally, museums will display replica sculptures painted with authentic pigments so that they appear to a modern audience as they would have appeared to their ancient creators. This always comes as a shock: the colourful sculptures look totally different from what we have come to regard as the original, clean stone versions; garish, unsubtle and, in many ways, less authentic.36 The Nefertiti bust can provoke a similar response, although in this case the paintwork is genuinely old. We have become so accustomed to seeing Egyptian sculpture unpainted, its hidden stone exposed, that the colourful queen can appear unacceptably modern and un-Egyptian to our preconditioned eyes. We forget that most Egyptian sculpture in the round, relief sculpture and painting was completed in full colour. The mineral-based paint was applied in solid blocks or, occasionally, in patterns, shading was rare, and the overall effect was far from subtle.37 Where traces of ancient paint do survive on a statue they may not adequately convey the vivid nature of the original, because Egyptian pigments are not entirely stable, and may deteriorate and lose intensity over time.

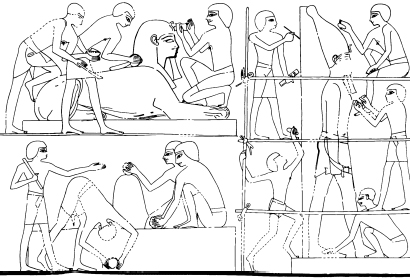

We have already watched Iuty paint Princess Baketaten. We can see another painter at work in the near-contemporary Theban tomb of Rekhmire. Rekhmire, vizier to the earlier Eighteenth Dynasty king Tuthmosis III (c.1479–1425 BCE), decorated his tomb with images of his daily responsibilities, which included control of the royal sculpture workshops. In one scene we can see artisans rubbing rounded stones over the surfaces of stone statues to smooth and polish them, while other workers add the finishing touches and identifying inscriptions to the royal images using paintbrushes and pens.38 This fits well with what we understand of the finishing process, which might include the addition of eyes inlaid with white and black stone bound by a copper line. A soft stone statue might be smoothed, plastered and painted in bright, mineral-based colours, while a hard stone statue might be polished and, perhaps, partially painted or gilded to pick out elements such as clothing and regalia, while the king’s flesh was left as polished stone. It was unusual for a hard stone statue to be entirely covered in plaster and paint (the plaster being necessary for the paint to stick), as the colour of the stone itself had symbolic importance. Quartzite and red granite, for example, had strong solar connections; this may explain why Akhenaten favoured yellow-red and purple quartzite for his Amarna statues. At Amarna, quartzite was almost entirely used for female statues, although Akhenaten did have quartzite shabti figures. Today Amarna is a place of mud-brick and sand; it is difficult to reconcile it with Akhenaten’s glittering, colourful city decorated with stone, faience and glass-paste inlays, painted and gilded.

New Kingdom artists creating royal sculpture, as shown in the tomb of Rekhmire (TT 100). After Davies 1943, Plate LX

Tradition dictated that Egyptian men would be painted with a red-brown skin while their female relations would be given a yellow-white skin. This was neither a value judgement nor a reflection of daily life; it was simply a means of allowing the viewer to make an easy distinction between males and females of all ages. It was, however, a convention rather than a rule, and an Amarna woman might have a red-brown skin. The Berlin bust, which has a pinkish-brown skin tone, therefore tells us nothing about Nefertiti’s actual skin colour. Ancient Egypt, a north-east African country with a Mediterranean border and a physical connection to the Near East, was filled, as Egypt is today, with African people of varying hue with, as a very general rule, skin being lighter in the north and darker in the south. Yet, swayed by the bust, many Western observers have unthinkingly assumed that Nefertiti was ‘white’, while many Afrocentrists have assumed that she was ‘black’, as they believe everyone in ancient Egypt to have been black. Some have assumed that the bust is a crude modern fake because it has the ‘wrong’ skin colour.39 The ancient Egyptians themselves would not have understood this modern obsession with classifying people by skin colour and racial heritage: they divided their world into Egyptians (those who followed Egyptian customs and accepted Egyptian beliefs) and non-Egyptians (those who did not). Skin colour was utterly irrelevant to them; behaviour was what mattered.

This identification of Nefertiti as ‘white’ allowed Western women to identify with her. She was a popular subject at fancy-dress parties and in fashion-oriented journals which, throughout the 1920s and 30s, posted regular features comparing conventional Western beauties (none of whom were dark-skinned, bald or lacking an eye) to the bust. Some of these women aspired to look like Nefertiti by employing Egyptian-style makeup and costumes; others were simply photographed in profile with their hair swept back. Unusually, the Sketch of 21 January 1928 was happy to acknowledge a black Nefertiti. An article entitled ‘The Black Journey’, an exploration of the characters encountered on a trip across Africa, included ‘A Negroid Nefertiti’, a woman whose ‘cast of feature and style of coiffure – Negroid as both undoubtedly are – are nevertheless reminiscent of the Egyptian queen who is now ranked as one of the world’s immortal beauties’. The suggestion here is that the African beauty is like Nefertiti despite her black skin rather than because of it.

It is skin colour, rather than hairstyle, that allows us to differentiate between Egyptian images of boys and girls, both of whom have shaven heads. As these bald children grow up they assume gender specific hairstyles, with men cutting their hair short (though they might then cover their head with a wig) and women either cutting their hair to cover it with a wig, or growing it long. Nefertiti’s bust lacks hair; it seems that the queen has either shaved her head or she has tucked her long hair up, inside her crown.40 Her apparently bald head matches those of her daughters, whose elongated shaven heads usually feature the ‘sidelock of youth’; a plait or series of plaits worn by elite children on the right side of the head, but whose quartzite heads recovered from the Thutmose villa are hairless. Where her hair is shown, Nefertiti favours the ‘Nubian wig’, a bushy, layered bob cut at an angle leaving the nape of the neck exposed. This style, which is believed to have been inspired by the naturally curly hair of the Nubian soldiers who fought in the Egyptian army, had previously been reserved for men connected with the military or the police force.41 At Amarna it was adopted by both Nefertiti and Kiya.

Her lack of hair gives the Berlin Nefertiti a sleek, modern androgyny which is emphasised by the hint of an Adam’s apple caused by the forward thrust of the neck and chin. Many find this attractive, but some find it unsettling. Camille Paglia, for example, suggests that

the bust of Nefertiti is artistically and ritualistically complete, exalted, harsh and alien … This is the least consoling of great art works. Its popularity is based on misunderstanding and suppression of its unique features. The proper response to the Nefertiti bust is fear.42

Kevin McGuiness attributes the bust’s fascination to its mixture of male and female traits:

The enduring fame of the bust can be directly traced to the liminal sexuality of the Queen. The long nose, square jaw line and strong chin contribute to a striking portrait of a woman who processes directly masculine characteristics. The Queen’s likeness operates between the dichotomous realms of the masculine and feminine, merging features associated with both sexes and creating a hybrid face which is at once captivating and unsettling.43

It is difficult to equate this austere, androgynous queen with the Nefertiti admired by James Baikie:

The portraits of other queens of romance, such as Cleopatra and Mary of Scotland, are apt to leave one wondering where the charm came in about which all men raved; but no one could question for a moment the beauty of Nefertiti. Features of exquisite modelling and delicacy, the long graceful neck of an Italian princess of the Renaissance, and an expression of gentleness not untouched with melancholy, make up the presentation of a royal lady about whom we should like to know a great deal, and actually know almost nothing.44

Clearly, beauty is a subjective issue; a personal feeling. And yet the Nefertiti bust is almost universally acknowledged to be the portrait of a beautiful woman. Despite the evidence of the awkward, angular Nefertiti carved on the Theban temple walls, and the older, tired Nefertiti created in Thutmose’s workshop, we are happy to accept the bust as the one true likeness of the queen, and to draw the inevitable unscientific conclusion: ‘Pharaoh’s principal wife, Nefertiti, was one of the most beautiful women of her generation.’45

Why is the Berlin Nefertiti so beautiful to so many us, irrespective of age, gender, race or culture? It may be that we find her beautiful simply because we expect to find her beautiful; she has, after all, been promoted as one of the world’s most beautiful women for almost a century, and she now has a very familiar face. Her romantic back-story, too, makes her very attractive: many of us are fascinated by the cloud of wealth, power and religious mystery that obscures the Amarna court. David Perrett’s studies of facial perception suggest another reason.46 Many of us find very symmetrical faces attractive, and the Berlin Nefertiti has a strikingly symmetrical face. Only her ears appear asymmetrical, with the left being more rounded at the lobe than the pointed right. This is likely to be either the result of damage sustained in antiquity or, as the recent CT scans suggest, the result of flint inclusions within the limestone core causing the sculptors to vary their work slightly.47

Using a grid superimposed on a photogrammetric image of the frontal view of the Nefertiti bust, Rolf Krauss has demonstrated that the sculptor used a grid to calculate the proportions of the bust, employing the ‘fingerbreadth’, the smallest measurement of length used by the Egyptians (1.875cm; 0.74in), as the base unit.48 Everything can be measured in fingerbreadths so that, for example, the crown is nine fingerbreadths tall above the queen’s forehead, and measures thirteen fingerbreadths at its widest point. The mouth is one fingerbreadth tall, the ear three fingerbreadths, and the distance between the eyebrows one fingerbreadth. Some find this symmetry off-putting; Nefertiti may be technically beautiful, but she is remote and artificial. To Borchardt, who scrupulously avoids using the word ‘beautiful’, this symmetry endows Nefertiti with an aura of peace, making her

the epitome of tranquillity and harmony. Viewed straight on it is perfectly symmetrical, but nevertheless, the viewer is never in doubt that he has before him not just any imaginary ideal image but rather the likeness, at once stylised but simultaneously true, of a specific person with a highly distinctive appearance.49

If Borchardt is correct, and the bust is true to life, Nefertiti’s symmetry is unusual. Most of us have one more expressive (and therefore more wrinkled) side, and our faces often exhibit variations in nostril size, ear shape and mouth curvature. We might expect to find the same symmetry, and the same measurements between features, apparent in the other heads identified as Nefertiti; however, this is not the case. While all the carved heads identified as Nefertiti share similarities – particularly with regard to the chin, mouth and cheekbones – they are not identical.

The fact that Nefertiti’s ‘flawless’ beauty includes one very obvious flaw – a missing left eye – seems not to matter. This is less a sign of our modern tolerance of disability or differentness, and more a question of our ability to ignore what is before our own two eyes. Photographs are taken in profile with the empty socket hidden, replicas are created with the missing eye replaced, and many commentators simply ignore the problem, so that some visitors are taken aback when they come face to face with the real bust. My own ever-increasing collection of miniature Nefertiti busts, all acquired from gift shops within museums that have little or no obvious connection to Nefertiti, includes just one example where the left eye is still missing. All the others have been ‘restored’ to present a more conventional appearance.

Nefertiti’s head extends forward from her neck, her chin slightly raised so that she looks visitors firmly in the eye. Wildung suggests that her gaze is ‘directed energetically toward the front, fixed so directly on an invisible person opposite that is [sic] seems impossible to escape’. Of course, the impression that we have of Nefertiti as she sits on her museum plinth depends very much on our own height; we all get a slightly different view and we cannot all look her in the eye.50 Her two eye sockets are roughly symmetrical, with an average depth of 3mm. The right eye is created from a ball of black-coloured wax placed in the white-painted eye-socket and covered with a thin (2mm) lens of rock-crystal engraved with the outline of the iris. The left eye contained no lens and no pupil. Both eyes are rimmed with black kohl, or eyeliner. When we notice the missing left eye, we tend to assume that the inlay has simply dropped out and been lost. Borchardt, for one, thought that this is what had happened. He tells us that, when it was recovered, the bust:

was almost complete. Parts of the ears were missing, and there was no inlay in the left eye. The dirt was searched and in part sieved. Some pieces of the ears were found, but not the eye inlay. Much later I realised that there had never been an inlay.51

A substantial reward was offered for the recovery of the missing eye, but it had vanished without a trace. The partial sieving of the debris yielded a few ear fragments, and nothing else. It is perhaps unlikely that a thin crystal lens and a small ball of black wax would ever have been found by workmen who failed to find the far larger and more substantial uraeus, but its absence has led to suggestions that it was never present. An examination of the socket has proved inconclusive here; while there is no obvious trace of glue, scratch marks on the lower lid could have been caused when the inlay was inserted.52

We have already met, and discarded, the theory that the bust was a teaching aid. More fanciful explanations for the missing eye – for example, the suggestion that Thutmose deliberately wrenched the eye from the finished bust as a means of gaining revenge on the beautiful queen who had spurned him as a lover – lack both credibility and supporting evidence.53 The explanation favoured by Arthur Weigall, that the bust is true to life, does not explain why her other images all show two apparently healthy eyes. In a newspaper article bluntly entitled ‘The Beautiful, One-Eyed Nefertiti’, Weigall told his readers that she had ‘suffered the very common Egyptian misfortune of losing the sight of one of her eyes, over which a cataract had formed’.54 The revelation of her ‘defect’, although contrary to established artistic tradition which would avoid any hint of deformity in a queen, was therefore yet another expression of the maat, or truth, favoured by the king. It could even be stated that, ‘the triumph of Nefertiti’s loveliness is enhanced by her deformity’.55 This was certainly the belief of the Nefertiti Club, which was founded in the 1930s by ‘the young wife of a prominent businessman in Omaha, Nebraska, who has a defect in her right eye’:

Though most of the members are good looking, they all possess a defect in one of their eyes. But all like Nefertiti refuse to believe that their disability makes them less attractive, and as they go about their daily tasks none of them shows any signs of self-consciousness or embarrassment.56