![]()

In the previous chapter we described the exploitation of insects by flowers that imitate the normal breeding sites of the insects but offer no food-base for the larvae. In the present chapter we turn to examples of symbiosis. In the more highly evolved cases, the plant provides a breeding site and the insect shows special pollinatory behaviour tending to ensure the survival of the host. But there are also simpler examples in which such behaviour is not apparent.

Here the pollinating activities of the insects are comparable to those of insect pollinators in general. In the aroid, Alocasia pubera, flies that may be pollinators complete their development in the inflorescence and pupate in the spathe (van der Pijl, 1953). Similarly, the biting midges that are pollinators of the cocoa tree (Theobroma cacao, family Sterculiaceae), breed in the decaying pods (Dessart, 1961). A parallel situation is said to be common in palms (Silberbauer-Gottsberger, 1991), but here the food-base for the insects is in the male inflorescences. Examples are the New World tropical palm Orbignya phalerata, the Old World oil palm, Elaeis guineensis, and probably Nypa fruticans in Papua New Guinea. The pollinator of the first is a beetle (Mystrops, family Nitidulidae) which lays eggs in the male flowers. These drop 48 hours after opening and the new generation of beetles emerges after 12–14 days. The beetles are only found in association with the palm (which is also partly wind-pollinated) (Anderson & Overal, 1988; Henderson, 1986). The pollinators of the oil palm are also beetles (see Chapter 13), whereas those of the Nypa are drosophilid flies (Essig, 1973). The breeding of pollinating flies also takes place in the male inflorescences of Artocarpus heterophylla, a tropical tree of the family Moraceae (van der Pijl, 1953) with edible fruits and nuts (jak or jack-fruit). The flowers are minute and are produced in large numbers on massive receptacles. The inflorescences have a smell of overripe fruit and are pollinated by small bees and by Diptera of two genera. After flowering the male flower-heads drop, and it is at this stage that the pollinating flies breed in them. In this way, the plants secure a population of pollinators constantly near to them. A similar pollination system is known in one of the cycads (see here).

The same end is achieved in a slightly different manner in some trees of Malaysia: Shorea section Mutica (family Dipterocarpaceae). The pollinators are thrips (Thysanoptera) and they begin to breed in the young flower-buds well before the flowers are ready to open. Within the time taken by the buds to develop into flowers they proceed through a number of generations, each lasting only eight days, destroying a proportion of the buds in the process. When mature, the undamaged buds open at dusk and the thrips then enter the flowers and feed from the petals and the pollen grains. They move readily from flower to flower, but as the trees are self-incompatible this is unlikely to lead to seed-set. By noon the following day, the propeller-shaped corollas have been shed and have whirled down to the forest floor. In the evening, when the new flowers are opening and producing their heavy scent, adult thrips that have remained in the fallen corollas fly up to the canopy and enter the new flowers. The descent from and return to the canopy may displace the insects, so that they reach a different tree. They can alight directionally and may also be carried about by wind movements. As the Shorea trees emerge from the canopy, the thrips have a chance of being carried further when they get above canopy level. The trees can produce millions of flowers at one brief flowering but occurrences of mass-flowering are occasional and separated by one or more much sparser flowerings. The thrips are generally available but their numbers are appropriately augmented by breeding in the buds that participate in a mass-flowering (Chan & Appanah, 1980; Appanah & Chan, 1981; see here).

A temperate example of the same phenomenon is provided by the globe-flower (Trollius europaeus) (Pellmyr, 1989), which is also self-incompatible. The pollinators of these spherical flowers that never open are three species of Chiastochaeta, flies of the family Muscidae, the larvae of which live only in Trollius flowers. Adult flies of both sexes enter the flowers to mate and feed on pollen and nectar. The females then lay eggs (usually one per flower). The fly species differ in the stage of flowering at which they lay eggs, in the positioning of the eggs, and in the paths along which the larvae bore inside the carpels during development. Thus they largely avoid competition. The species that oviposits earliest in the 5–6-day life of the flower is the most effective pollinator. There is a fourth species that oviposits too late to cause any pollination (Pellmyr, 1992). Placement of pollen on the stigmas is incidental to the movements of the flies in the flowers. A flower produces nearly 400 ovules, but only a few of the young seeds are eaten by the fly larvae. Several other Trollius species are facultatively pollinated by Chiastochaeta species that breed in the flowers in Asia; here the flowers are flat and some pollination takes place in the absence of these flies (Pellmyr, 1992).

It seems that the insects pollinating Alocasia pubera (a fly-trap flower, see here) and Trollius europaeus were pollinators before they evolved the habit of breeding in the plants, and the same is perhaps true of the insects breeding in palms. In the cases of the pollinators of Artocarpus heterophylla and Theobroma cacao, there seems to be no strong evidence either way

In some of the relationships described above the insects live in tissue which the plant has discarded, though it is possible that it produces more of this than it otherwise would so as to feed the potential pollinators. However, in Shorea and Trollius what the insects eat is not waste tissue, and it clearly represents a trade-off on the part of the plant against pollinator service. All these relationships involve small or very small insects, so it looks as though the plants are minimising their costs in the deal.

The rest of this chapter is devoted to two relationships: that between figs and fig-wasps and that between yuccas and yucca-moths. As in some of the preceding examples, the insects depend entirely on the plant and use the ovaries as the larval food-base but they display physical and behavioural adaptations for the pollination of their hosts.

The figs (Ficus) belong to the same family, Moraceae, as Artocarpus and, like it, bear numerous tiny flowers on a massive receptacle. Here, however, the receptacle has become moulded into a hollow vessel with the unisexual flowers clothing its inner surface. This receptacle (‘syconium’) has a narrow opening (‘ostiole’) to the outside which is blocked by flexible scales; it becomes the fig ‘fruit’. Female flowers contain only one ovule.

The best-known member of this very large genus is the edible fig (Ficus carica), which is probably native to south-west Asia. In the wild form of this species, three types of receptacle are produced at different times of the year. The type formed in winter contains many neuter (sterile female) flowers, and a smaller number of male flowers which are confined to the region of the entrance. This type of receptacle is invaded by tiny females of the gall-wasp species Blastophaga psenes, which lay eggs in the neuter flowers and then die. The offspring of the wasps complete their development in the ovaries of the flowers (one wasp to each flower). The male wasps hatch first and emerge from the ovary into the interior of the receptacle. They are highly modified, having reduced legs and eyes and no wings (Fig. 11.1A). They bore into the ovaries occupied by females, fertilise the females and then die. The females now emerge and leave the receptacle, receiving pollen at the entrance from the male flowers which have only just opened. It is now June, and the wasps find their way to the second type of receptacle. This type contains either a mixture of neuter and female flowers, or female flowers only. The wasps lay their eggs in the flowers, but only those laid in neuter flowers develop. The ovary of the neuter flower (a modified form of the female flower) is incapable of producing a seed, and the style is short with an open canal leading to the ovary. In the female flower, on the other hand, the solid style is too long to permit a wasp to reach the ovary with its ovipositor, and eggs not placed in the ovary fail to develop. The pollen which the wasps bring with them fertilises the female flowers, and so seed is set in these. The development of the wasps takes place as before, fertilised females emerging in autumn and going to the third type of receptacle which is smaller than the others. Here there are only neuter flowers, in which the insects develop that will emerge in winter and restart the cycle in the first type of receptacle (McLean & Cook, 1956; Grandi, 1961).

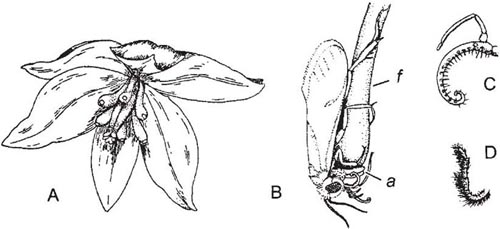

Fig. 11.1 Fig-wasps and fig flowers. A, a female and male of Blastophaga quadraticeps; B, female of Ceratosolen arabicus in the act of oviposition, with forelegs raised to extract pollen from the thoracic pockets. From Galil & Eisikovitch (1968b & 1969).

The entry of the female fig-wasps into a syconium is made difficult by the scales in the ostiole and they may lose wings and parts of their antennae in their struggles to get in (Grandi, 1961). The resistance offered is apparently an adaptation to prevent the entry of insects lacking the instinctive persistence of the female fig-wasp. When it lays an egg, the wasp injects a drop of a special secretion into the ovary of the neuter flower, and this stimulates the development of the the unfertilised ovule into a gall, which later provides the nourishment for the wasp larva. Thus the plant provides special flowers in which the pollinators breed, the winter syconia being devoted solely to this use.

Some cultivated forms of the edible fig are entirely female, but in these no pollination is necessary for the fruits to develop (McLean & Cook, 1956). All other sexually reproducing species of the mainly tropical genus Ficus provide neuter flowers for the pollinating wasps to breed in, but the life-cycle is normally less complicated than that of the edible fig. There are two main types (Wiebes, 1963). In one, exemplified by F. fistulosa, pollinated by Ceratosolen hewittii (Galil, 1973), there are two kinds of receptacle, one containing female flowers only and the other containing both neuter and male flowers. Fertilised female wasps emerging from the latter enter the next generation of either the same kind of receptacle or else the female kind. In the first case, the wasps lay their eggs, and in the second they pollinate the flowers. The two kinds of receptacle are normally on different plants (dioecy) (see here). In the other type of life-cycle, all three kinds of flower occur in the same receptacle (monoecy). Fertilised female wasps pollinate the female flowers and breed in the neuter flowers, while their departing female offspring later acquire pollen from the male flowers. Usually the neuter flowers have short styles and the female ones longer styles, which makes oviposition in the latter difficult or impossible. In Ficus sycomorus (Fig. 11.1B) and F. religiosa, however, it has been found that long-styled and short-styled flowers are not physiologically different, for small percentages of the short-styled produce seeds, and of the long-styled produce galls (Galil & Eisikovitch, 1968a, b).

Another significant observation on F. religiosa is that female wasps newly emerged from the galls are attracted to the anthers, push their heads amongst them and even eat some of the pollen. The dependence of the wasp Blastophaga quadraticeps on this plant is emphasised by experiments on this species in which female wasps which had not been in contact with pollen were allowed to enter the receptacles. These dropped off without forming galls or seeds (Galil & Eisikovitch, 1968b).

During a study of the pollination of Ficus sycomorus in East Africa, Galil & Eisikovitch (1969) were puzzled at its effectiveness in view of the small amount of pollen carried on the body of the wasp, Ceratosolen arabicus – it always cleans itself carefully on emerging from the syconium. The accidental squashing of an insect led to the discovery of a pair of pouches on the underside of the thorax, each of which can probably carry 2,000–3,000 pollen grains. Because ovipositing females continued their activities despite the opening of the fig for observation, it was possible to see that after each egg had been laid, the forelegs were used to scratch some pollen out of the pouches and brush it on to the stigmas (Fig. 11.1B). In this way, a mixture of gall-flowers and seed-flowers develops in the area where the female has been working. When the receptacle has reached the male stage, male wasps emerge from their galls and after copulating with the females they cut off the anthers of the male flowers. The females emerge and with their fore-claws and a special comb on the fore-coxae load their pouches from the loose anthers. The males then collaborate in boring a hole to the outside and the females depart (Galil & Eisikovitch, 1968a, 1974). After the discovery of the pouches in C. arabicus, it was found that Blastophaga quadraticeps and some other fig-wasps had pollen pouches (Galil & Snitzer-Pasternak, 1970). Some of these are New World species, and the females of two of them, B. tonduzi and B. esterae, also search for and manipulate the anthers of the fig; they carry pollen in pouches sunk between the first and second thoracic segments on either side, and also in a recessed pollen basket (corbicula) on each of the fore-coxae (Ramirez, 1969; Galil, Ramirez & Eisikovitch, 1973). Thus the pouches are different in form and position from those of Ceratosolen arabicus. The claws of the forelegs can reach the pouches and the corbiculae; they appear to hook pollen out and are then knocked against each other as if to shake the pollen off on to the stigma. The ostiolar scales of the figs do not loosen but the male wasps bite a hole to the outside through which the fertilised female wasps carrying pollen depart. Ramirez found pouches in many other New World species of Blastophaga and in fig-wasps of other genera from various parts of the world.

Where pollination is ‘deliberate’ rather than random, it is of interest to know how the female wasps treat the sterile and fertile female flowers. In the dioecious Ficus fistulosa, wasps in the male syconia pollinate the gall-flowers, although these are not destined to produce seed, and in the female syconia they carry out oviposition movements (but probably do not lay eggs) before each pollination of a stigma, although no wasps will develop in the ovaries (Galil, 1973). Apparently the pollination of the neuter flowers stimulates growth of the endosperm of the ovule which is necessary for the nourishment of the wasp larva. This serves the same purpose as the injection of a growth-stimulating compound reported in F. carica.

A case of physiological control of the wasps’ behaviour in F. religiosa was uncovered by Galil, Zeroni & Bar Shalom (1973). It was found that as the male wasps matured, their activity in emerging from their galls and mating with the females was stimulated by and dependent on a very high concentration of carbon dioxide in the receptacle. The males eventually bore holes through the fig wall and the atmosphere inside then equilibrates with that outside. In the lowered concentration of carbon dioxide the female wasps, previously inhibited, become active, emerge from their galls, load their pouches and exit through the borings. No such responses could be found in the wasps in F. sycomorus.

In non-seasonal tropical climates, where most figs grow, the plants can reproduce at any time of the year and there is usually a year-round availability of receptive syconia. This is achieved by occasional flowering of plants at irregular intervals, which is accompanied by synchronisation of flower and fruit development within the plant. Outbreeding will thus be enforced, and the pool of neighbours that are receptive will be changed at successive flowerings. However, when the wasps emerge from a particular tree, only a small proportion of the fig population is available to receive pollen, so that for pollination purposes the effective density of the population is greatly lowered and fig-wasps may have to travel relatively long distances to propagate themselves. It is inferred that receptive trees are located and identified by scent (Janzen, 1979; Addicott, Bronstein & Kjellberg, 1990).

Each species of fig-wasp (Hymenoptera-Parasitica, family Agaonidae) normally confines itself to one species of fig-tree (Wiebes, 1963; Hill, 1967). Exceptions are where one species of wasp pollinates two very closely related species of Ficus or two closely related wasps pollinate the same Ficus in different areas. This species-to-species relationship means that the rates of speciation of the fig-wasps and the fig-trees have been about equal, even though their generation times are enormously different. Some Ficus species are known to be interfertile, but no natural hybrids have been found, presumably because the wasps identify their particular host accurately.

Although there may be only one species of pollinating wasp in a species of fig, it is normal for parasites to be present. Thus in F. sycomorus, five species of wasp have been found in the syconia apart from Ceratosolen arabicus and none is known to cause pollination even though one belongs to this genus. The wasp Sycophaga sycomori enters the syconia and lays eggs in any female flower, since its ovipositor is longer than that of C. arabicus. However, when the latter is engaged in egg-laying, it ‘stings’ the styles of neighbouring long-styled flowers and bites their stigmas. This does not prevent the seed from developing but it does render them unsuitable for Sycophaga; thus different areas of the syconium come to be occupied separately by these two wasps. The other three wasps belong to family Torymidae; they have very long ovipositors with which they pierce the syconium from outside and lay eggs in galled flowers only, that is, those already occupied by Ceratosolen or Sycophaga. The larva of the corresponding torymid in Ficus carica kills the occupying larva. In the absence of Ceratosolen, oviposition by Sycophaga is effective in causing the syconium to complete its development, although it is seedless. This is the case in the East Mediterranean region where F. sycomorus is grown; the male wasps, like those of Ceratosolen, bore the hole to the exterior through which the females escape (Galil & Eisikovitch, 1968a, 1969; Galil, Dulberger & Rosen, 1970). Some torymids that live in figs appear to develop in unoccupied ovaries (Bronstein, 1991). This applies in F. pertusa where Bronstein found that Torymidae and Agaonidae did not seem to compete for food, and there were frequently more torymids in the syconia than agaonids (but the numbers were independent). The torymids depended on the agaonids to induce retention of the syconium on the tree and for the boring of the exit holes from the syconia.

The relationship between the yucca plant and the moth that pollinates it is similar to that between fig trees and fig-wasps, and is equally famous. Pioneer studies on this relationship were carried out by Riley (1892) and Trelease (1893); later work by Busck was included in a taxonomic monograph on Yucca by McKelvey (1947). New information, summarised by Powell (1992), has greatly amplified the knowledge gained by these early investigators. Yucca (family Agavaceae) is a genus of North America and the West Indies. Typically, the plants produce showy inflorescences of numerous large creamy-white flowers (Fig. 11.2A). These are partially closed by the convergence of the tips of the perianth segments; they are scented and smell most strongly at night. Nectar is sometimes secreted at the base of the ovary but it is not drunk by the yucca-moths, which do not feed; it may, however, keep other insects, which are attracted to the flowers, away from the stigmas, though in some circumstances honeybees and bumblebees may cause pollination in yuccas (Powell, 1992).

The moths belong to the small suborder Monotrysia (see here), family Incurvariidae, subfamily Prodoxinae (Davis, 1967); they are not unlike Eriocrania, a genus with primitive mouth-parts described in Chapter 4. Each of the maxillae of a yucca-moth comprises a galea similar to that of Eriocrania (Box 4.2) and a palp, the latter with a special tentacle, prehensile and spinous, formed by the modification of the basal joint of the palp (Fig. 11.2C).

When ovipositing, yucca-moths have a stereotyped pattern of behaviour. The female moth, Tegeticula yuccasella, enters the flower, climbs along a stamen from the base and bends its head closely over the top of the anther. The tongue uncoils and reaches over the tip of the anther, apparently steadying the moth’s head. All the pollen is then scraped into a lump under the head by the maxillary palps, and held fast by the maxillary tentacles and the trochanters of the forelegs (Fig. 11.2B). As many as four stamens may be climbed and the pollen collected in this way. As a rule, the moth then flies to a flower in another inflorescence, where it closely investigates the condition of the ovary, being able to tell if the flower is of the right age and whether eggs have already been laid in it. If the flower is suitable, the moth again climbs the stamens from the base but this time goes between them on to the ovary. It then reverses a little way back between the stamens and the ovary and lays an egg, boring into the ovary with its ovipositor. After this it at once climbs to the stigmas, which are united to form a tube, and thrusts some of its pollen down into the tube, working energetically with the galeae and tentacles. The most usual behaviour of the moth is to lay one egg in each of the three cells of the ovary, and to carry out pollination after laying each egg.

Since an unpollinated yucca flower soon dies, this behaviour of the moth ensures that there will be food for its larvae, which is provided by the abnormal growth of one or more of the ovules in the neighbourhood of each moth’s egg. The remaining ovules, which are numerous, develop into seeds and, just as they are ripening, the moth larvae emerge and pupate underground. The adult moths always emerge in the flowering season of the yuccas in their area. The emergence of any one season’s brood is spread over a period of some years after pupation, thus ensuring the continuance ance of the moth species even if, as occasionally happens, the yuccas fail to flower in a particular year. In this relationship the moth, like the fig-wasp, ensures the seed-production of its food-plants, while the plant provides food and shelter for the young of its pollinator. As the flowers are protogyrious, the moth needs to move to another flower after gathering pollen in order to find an ovary in the receptive stage for pollination; but it does more – it goes to another inflorescence, thereby promoting outbreeding, which should enhance the genetic quality of the of the next generation of host-plants. (In the fig, the wasps that have gathered pollen are forced to find another syconium because at this time there are no receptive female flowers in the syconium from which the pollen was gathered.)

Fig. 11.2 Yucca and yucca-moth. A, flower of Yucca aloifolia, with the perianth segments parted to show six swollen stamens and the ovary with stigmatic lobes; B, female moth, Tegeticula yuccasella, gathering pollen from a stamen (f, filament of stamen; a, anther): C, maxillary palp and tentacle (coiled) of the moth; D, labial palp of same. After Riley (1892).

The currently recognised species of yucca-moth belong to two genera and are listed in Table 11.1, together with their host-plants. Tegeticula yuccasella is enormously widely distributed in the United States, mainly east of the Rockies but reaching the west coast in California. These small moths are active at night and spend the day at rest in the flowers, which they resemble in colour. Parategeticula also pollinates flowers at night; it occurs in two isolated areas and in each it pollinates a single species of Yucca. T. maculata pollinates only Yucca whipplei, which occurs in southern California, and has glutinous pollen massed into two pollinia in each anther; the moths carry out pollination in the daytime. T. synthetica, pollinator of Y. brevifolia in the Mohave Desert of California, has a hard body and scaleless wings and appears to mimic sawflies of the genus Dolerus. Its host-plant has flowers with very firm perianth segments, scarcely parted at the tips, so that the moth has to force its way in as the fig-wasps do (Powell & Mackie, 1966; Powell, 1992).

Evidence has now been obtained that ‘T. yuccasella’ is a complex of closely related species, each more or less specific to one Yucca species (Tyre & Addicott, 1993). The taxonomy and biology of these is not yet worked out.

Various statistics have been gathered in order to estimate the trade-off of seeds against pollination in yuccas. A study of eight species of Yucca, pollinated by T. yuccasella, was carried out by Addicott (1986). Yucca ovaries contain many ovules, in these eight species ranging from 150 to 350 (lower numbers are found in berry-fruited yuccas) (Table 11.1). Seed production ranged from 90 to 200. Both these measures varied between species and between populations of the same species. The ratio of viable uneaten seeds to ovules in different species ranged from 0.36 to 0.60, but the variation was not statistically significant; however, differences between populations within species were significant. Fruit set also varied greatly between populations within species.

One yucca-moth larva may eat from 6 to 25 seeds. Oviposition and the development of moth larvae cause constrictions that distort the fruit, and some ovules additional to those used as food may be damaged by these processes. Other failures could be due to inadequate pollination or limitation of resources available to the plant for seed-maturation. Individual yucca-moth larvae ate 18–43.6% of the ovules in a locule; however, since not all ovules were potentially viable, the effective loss was only up to 13.6%. Adding damage by oviposition, the moths reduced seed production by 0.6–19.5%. The number of larvae per fruit was usually below ten but occasionally up to 24 (earlier, Addicott had found populations with 30–50 larvae per fruit). The highest numbers of larvae probably occur as a result of yucca-moth visits to the young fruit stage, when additional eggs are laid. A high proportion of fruits contained no larvae, especially in berry-fruited species. Such fruits show signs of oviposition and it is thought that a high egg mortality accounts for the frequent lack of larvae.

Fruit-abortion rates are significant in maintaining a balance between seed-production and moth-production, as described below. Individual plants of Yucca whipplei aborted 29–72% of their fruits (Aker & Udovic, 1981), while in a further set of eight species fruit abortion rates ranged between 0–100% (Addicott, 1985) (but most of these species had lower abortion rates than Y. whipplei). Abortion of fertilised ovaries is attributable to resource-limitation. Fruit initiation was high in some species, but in others 23–33% of plants initiated no fruit at all. Low levels of fruit-set are presumed to be the result of pollinator-limitation.

Just as the symbiotic system of Ficus carries its load of parasites, so does that of the yucca. Closely allied to the yucca-moth is the bogus yucca-moth (Prodoxus). Superficially it resembles T. yuccasella, but its maxillae have no tentacles. It breeds in the ovaries or peduncles of yucca flowers and, since it does not pollinate the flowers, it depends for its existence on the true yucca-moth. In addition, there are four species of non-pollinating ‘advantage-takers’ in the T. yuccasella complex: as species, these fly later than the mutualistic species and they too lack maxillary tentacles. Species of this kind have arisen at least twice (Addicott, Bronstein & Kjellberg, 1990).

The yucca-moth and the fig-wasp both belong to groups in which feeding by the larvae on the internal parts of plants is frequent, so we may conclude that this process probably evolved first, the insects originally being at most incidental pollinators of the host-plant (Pellmyr & Thompson, 1992). It is thought that the yucca and moth interaction is probably quite recently evolved, since the form of most yucca flowers (large showy white bells) and the secretion of nectar by many of them, seem inappropriate to the pollination method. The fig and wasp relationship looks as if it is much older.

It is remarkable how the symbiotic pollinators have undergone structural modification and have developed very complex behaviour in relation to the flower in the course of the evolution of these partnerships. The plant-pollinator relationship is at the opposite extreme from that in deceit flowers, since mutual dependence is complete. Co-evolution has proceeded a long way, whereas in deceit flowers it is (by the definition of the term ‘co-evolution’) absent. However, it can be inferred that there is tension even in these relationships.

For climatic reasons, flowering in yuccas has to be strongly seasonal. Various factors promote synchrony of yucca-moth flight with flowering, but this is sometimes imperfect and in any case some yuccas have a long season (about 10 weeks in Y. whipplei [Aker & Udovic, 1981]). Those moths flying relatively late in the flowering season will consequently encounter young fruits as well as fresh flowers. If yucca pollination has been good, plants may abort some fruits because of shortage of resources. The fruits most likely to be aborted are the late ones in which less has been invested. The late moths’ prospects are therefore best if they oviposit, not into the late fresh flowers, but into already fertilised and developing ovaries which have no need of pollination. The floral environment of relatively late moths thus favours ‘cheating’, and there is extensive evidence that this occurs (Addicott, Bronstein & Kjellberg, 1990). ‘Cheating’ has been observed in Tegeticula maculata on Yucca whipplei (Aker & Udovic, 1981) and on Y. kanabensis, where it has been shown that, although some moths oviposit when not carrying pollen, pollen-carrying moths may also ‘cheat’. Here, however, non-pollination is strongly associated with oviposition in flowers already pollinated. ‘Cheating’ behaviour is not a characteristic of individual moths – it is facultative. Since ‘cheating’ is not here related to season but is observable on single oviposition bouts, it was concluded that it was related to an abundance of the moths, which could lay extra eggs in already-pollinated flowers and so leave more progeny (Tyre & Addicott, 1993).

In the case of fig-wasps, it can be surmised that if they grew longer ovipositors they could breed in more of the flowers in the syconium. The plants’ best evolutionary response would at first sight seem to lie in growing longer styles. But because of the short generation time of the wasp compared with that of the fig-tree, the wasps might win the evolutionary race and in so doing prevent the plant from reproducing, so that both plant and wasp would become extinct. However, there is no evidence for disproportionate length in either ovipositors or styles. Murray (1985) has suggested how a balance might be achieved. It is supposed that the fig-plant has the power to abort young syconia and that abortion can be triggered by the level of infestation of the syconium by fig-wasps. Natural selection would then set the threshold level of infestation at which abortion began, so as to provide the best balance between seed-production and pollinator-production. If fig-wasp oviposition became too successful, fig-abortion would destroy the larvae, together with the genes for a long ovipositor that they carried.

When this system is in balance, the style-length variation places an upper limit on the number of ovaries in the syconium that contain fig-wasps. This means that abortions of fertilised syconia are rare and so one factor that at times makes ‘cheating’ advantageous to yucca-moths is absent in the fig. A very low availability of syconia, which might occur seasonally or locally, could make it advantageous for wasps to oviposit in developing pollinated syconia. However, there seems to be no facultative ‘cheating’ by fig-wasps, and the exploiting species Sycophaga sycomori, described by Galil & Eisokovitch (see here), is apparently the only known case of such a species being closely related to the pollinator (Addicott, Bronstein & Kjellberg, 1990).

The relationship between dioecious figs and their pollinators presents an interesting problem: female wasps that enter female figs leave no progeny, so are the plants able to make the male and female syconia indistinguishable or are the wasps displaying ‘altruism’? Various aspects of the fig/fig-wasp mutualism are discussed in detail by Addicott, Bronstein & Kjellberg (1990) and by Janzen (1979), who cite many other studies on these problems.