CHAPTER 2:

THE CLASSICAL MAZE

Labyrinths in the ancient world

“Then we got into a labyrinth, and, when we thought we were at the end, came out again at the beginning, having still to see as much as ever.”

—from Euthyphro by Plato, 395 BCE

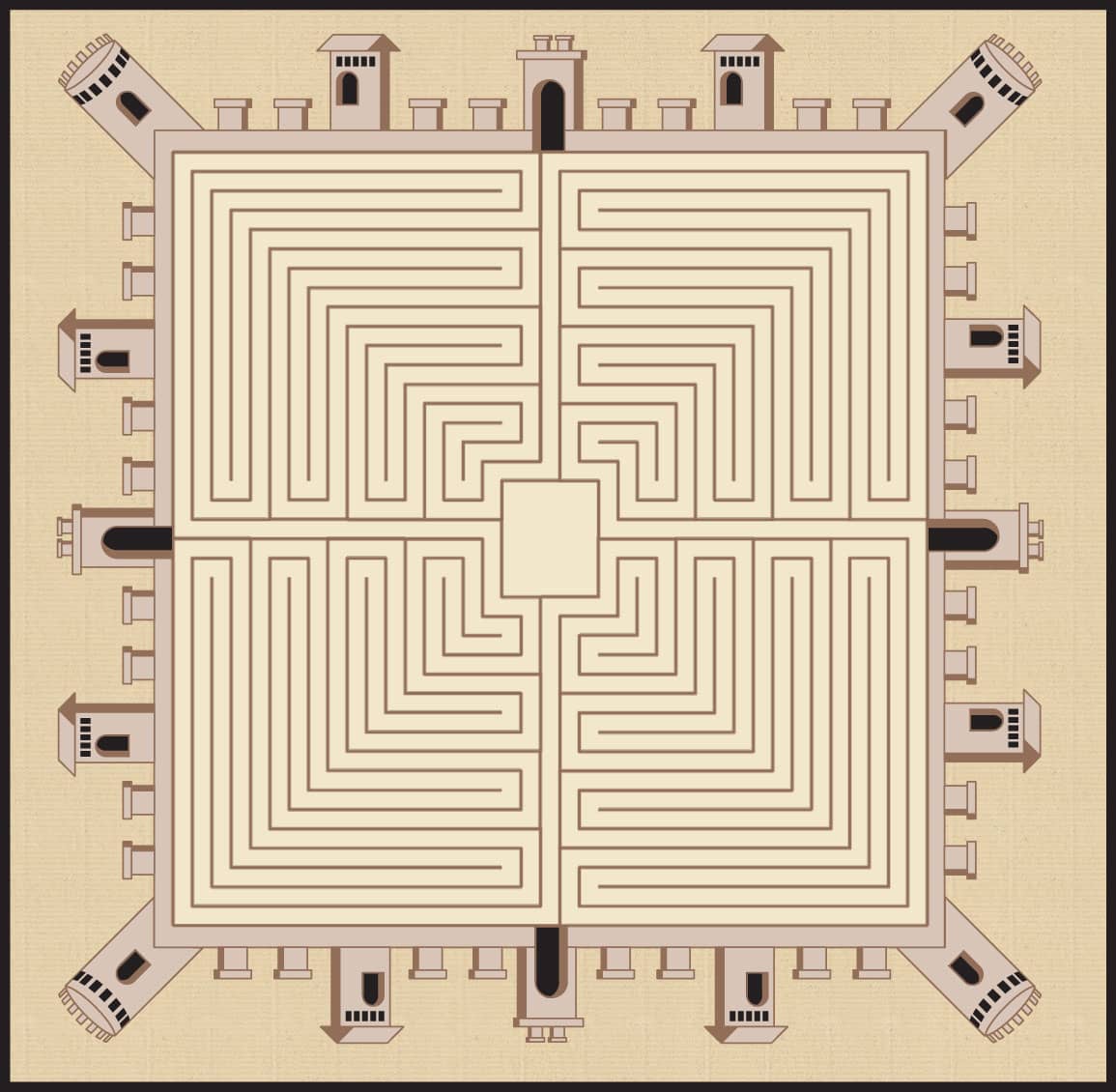

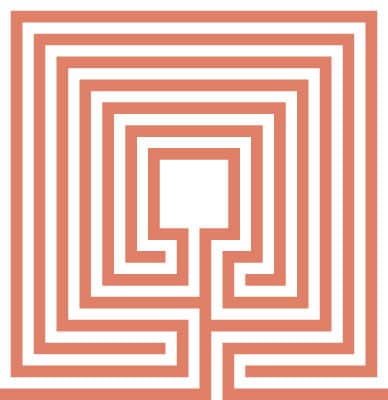

Jeff Saward set out the archetypal labyrinth classical design as consisting of a single pathway that loops back and forth to form seven circuits, bounded by eight walls, surrounding the central goal. This can take a circular or square form (Fig. 1 and Fig. 2). As we have already seen, early examples of these, with more or fewer paths, are found throughout the world. Sometimes the form is called the “Cretan” labyrinth, even though it predates the Cretan legend, a legend that persisted throughout the Roman Empire from the second century BCE to 400 CE and which influenced the creation of many complex labyrinthine decorations.

Fig. 1: Circular classical labyrinth.

Fig. 2: Square classical labyrinth.

The earliest dated example of those more complex designs is the opus signinum pavement, found at Mieza, Greece, in the early 1980s. Dating from around 165 BCE, the pattern was constructed from river gravel and small pieces of stone or terracotta fragments set in lime or clay. Soon after, Roman pavements were constructed in mosaics of shaped pieces of stone, ceramic, or glass. It is suggested that the shift toward a more complex design was partly due to the need for a regular geometric pattern more suited to mosaic.

The Roman labyrinths were unicursal (one path) and often divided into four. And as mosaics, they were generally, but not exclusively, on floors. Labyrinths, mostly too small for walking, were laid in the floors of bathhouses, villas, and tombs throughout the Roman Empire, and it has been observed that many were flawed since no one actually walked them! Around sixty-five examples have been discovered, but less than two thirds of those survive, and some have been reburied for protection. Roman labyrinth designs have been grouped into three main types: (1) serpentine, (2) spiral, and (3) meander (see here for illustrations). These are the forms they took, with a few exceptions. There is also a complex meander type, from Pula, Croatia, which has separate entrance and exit paths (shown here).

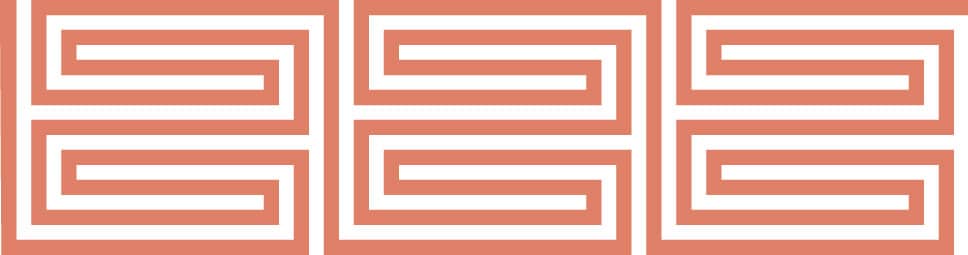

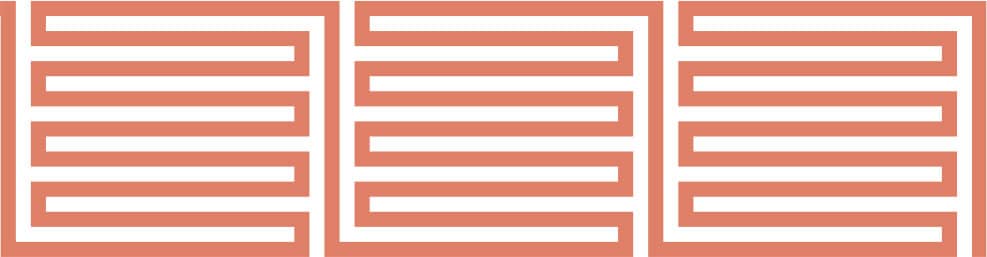

Meander takes its name from the Meander River that winds through northern Turkey. A running pattern of left turns followed by right turns (or vice versa), it is a connected pathway, often leading through four sections (Fig. 3). The Serpentine, sometimes divided into eight sections, moves to and fro (see Fig. 4). An interesting example is the serpentine “Roman Labyrinth” with eight segments, from Cormerod, Switzerland (shown here). The Spiral is simply a form of meander (Fig. 5).

Fig. 3: Meander pattern.

Fig 4: Serpentine pattern.

Fig. 5: Spiral pattern.

Example of serpentine “Roman Labyrinth.”

Example of spiral “Roman Labyrinth.”

Example of simple meander “Roman Labyrinth.”

Example of complex meander from Pula, Croatia, with separate entrance and exit paths.

Serpentine “Roman Labyrinth” with eight segments, from Cormerod, Switzerland.

In Roman times, the classic Cretan design appeared to go out of fashion. Pliny the Elder, in Natural History, writing about Daedalus and the construction of the “Cretan Labyrinth” with its “circuitous passages, windings, and inextricable galleries,” declared, “We must not compare this last to what we see delineated on our mosaic pavements.” Pliny was distinguishing between the first “Cretan Labyrinth” (the construction of which he considered to have been influenced by the “Egyptian Labyrinth”) and the many labyrinthine motifs found in Roman decorations. Pliny mentioned four ancient labyrinths, including the Egyptian and the Cretan, which we learned about in chapter one.

Pliny names the Greek sculptor Smilis (a contemporary of Daedalus), together with Rhoikos and Theodoros, as the makers of what he calls the “Lemnian” Labyrinth. There is some confusion, however, as Pliny had already referred to this labyrinth as the temple built by Theodoros at Samos, the old name for the island of Samothrace where there was a major flood in 5600 BCE. As it happens, the Homeric word for flood, or impetuous waters, is labros, and it is likely that Pliny had named it as a labyrinth in error. Pliny’s “Italian” Labyrinth is the tomb of the Etruscan General Lars Porsena, at Clusium (modern Chiusi), described via a quotation from the historian and Roman antiquarian Varro, who writes about “a square monument built of squared blocks of stone, each side being 300 feet (91 m) long and 50 feet (15 m) high. Inside this square pedestal there is a tangled labyrinth, which no one must enter without a ball of thread if he is to find his way out.” The Lemnian and Italian Labyrinths have never been found.

The Cretan legend and labyrinthine buildings (real or imagined) inspired other Roman writers. It is suggested that the Roman poet Catullus not only cited the legend but also used it as inspiration for the structure of his Poem 64, as did Plato for the Euthyphro. I have already noted that Virgil’s Aeneid is imbued with labyrinthine leitmotif. And Ovid, in Metamorphosis, compares the labyrinth to the River Meander. The Roman biographer Plutarch also wrote about Theseus, Minos, and Ariadne.

While we may never see Pliny’s Lemnian or Italian Labyrinths, Roman labyrinth mosaic floors are found in Rome and provincial Italy, Portugal, Cyprus, Africa, Iberia, France, and Britain. It is somewhat ironic that while the Roman mosaic floor had its origins in Greece, and while the Romans employed Greeks to design and build their floors, one rarely finds ancient labyrinth floors in Greece itself. Mosaic craftsmen at the time carried their own pattern books, not just to aid construction but also to show prospective clients. And they could produce labyrinth mosaics specially tailored for the available space. Labyrinths are not, of course, absent from Greek culture, as we shall see later in this chapter when we look at Greek pottery and decorations.

A well-preserved Roman mosaic, originally discovered on the floor of a villa bathhouse near Salzburg, Austria, in 1815. Now housed in Vienna’s Kunsthistoricsches Museum. Photo: Science History Images / Alamy Stock Photo.

Originally discovered on the floor of a Roman villa bathhouse near Salzburg, Austria, is a well-preserved third-century CE mosaic, measuring 18 feet (5.5 m) long and 21 feet (6.4 m) wide (opposite). Uncovered in 1815, this magnificent mosaic is now housed in Vienna’s Kunsthistorisches Museum. The labyrinth includes scenes from the Cretan legend and has one opening, situated close to Ariadne. Many, though not all, Roman labyrinths feature the Minotaur. In the Salzburg design, the labyrinth is surrounded by brick and stone walls, topped with battlements. The escape from Crete, beyond the labyrinth, is also featured.

Another example featuring the Cretan legend can be found in the House of the Labyrinth at Pompeii. The house, excavated in 1834, dates back to the Samnite period (600–290 BCE). And a circular mosaic, quite unusual and dating from the third century CE, can be found in the ruins of the House of Theseus at Nea Paphos on Cyprus. The center portrays the Cretan legend (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6: An unusual circular mosaic dating from the third century CE found in the ruins of House of Theseus at Nea Paphos on Cyprus. The center portrays the Cretan legend. Photo: Steve Bridge/Dreamstime.com.

In chapter one we saw an example of labyrinth graffito from Pompeii, discovered outside the house of Marcus Lucretius. There are over six thousand messages on walls in Pompeii, and it seems that all Roman cities were covered in graffiti. One writer in Pompeii had scrawled, “I wonder, O wall, that you have not yet collapsed under the weight of all the idiocies with which these imbeciles cover you!”

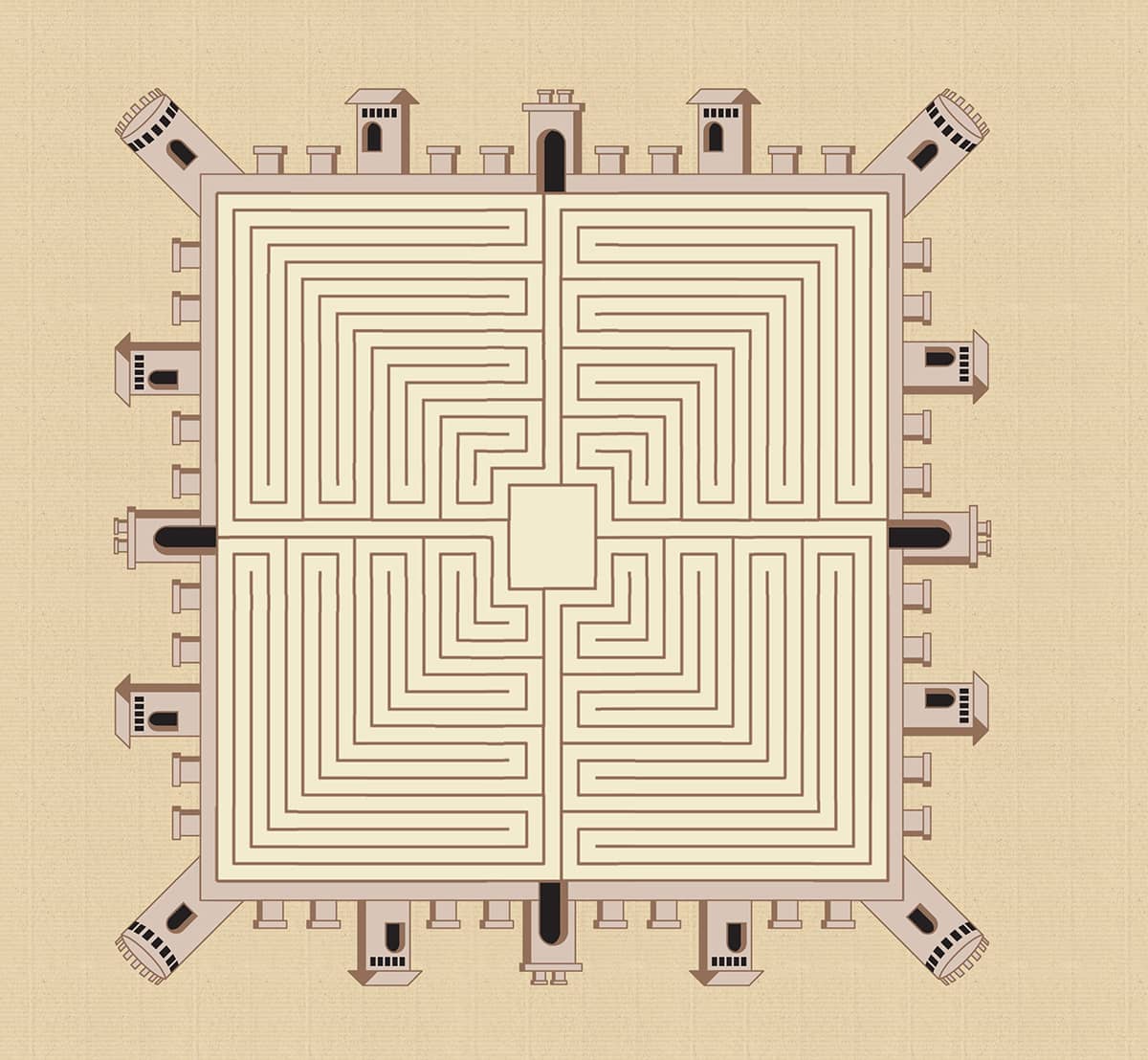

Roman mosaic labyrinths are often located near entrances, and many are surrounded with a mosaic representation of fortified walls. Again, at Pompeii, in the Villa of Diomede, there was a labyrinth pavement with walls and battlements (shown here). Such walls are not a part of the Cretan legend but give us some indication of their function as a symbol of Roman security and stability. Certainly, some Roman labyrinths have the appearance of a city layout.

The Greek philosopher and historian Strabo used the word labyrinth to describe a catacomb near Nauplia, which he calls the “Labyrinth of the Cyclops.” He writes of “vast caverns in which are constructed labyrinths that are believed to be the work of the Cyclops.” Nauplia, said to be the birthplace of Apollo’s son Asklepios (the healer), is a port city in Greece. Catacombs, also found underneath other ancient cities, were burial places. The Etruscans, from around 800 BCE, buried their dead in these underground labyrinthine chambers, and W.H. Matthews in his classic 1922 work on the history of mazes and labyrinths, is reminded of the catacombs of Rome, Paris, and Naples. A second-century CE labyrinth from within a Roman tomb, found at Sousse, Tunisia, bears the inscription, Hic inclusus vitam perdit, translated as, “He who is locked in here will lose his life.”

Representation of the labyrinth pavement with walls and battlements, in the villa of Diomede at Pompeii, Italy.

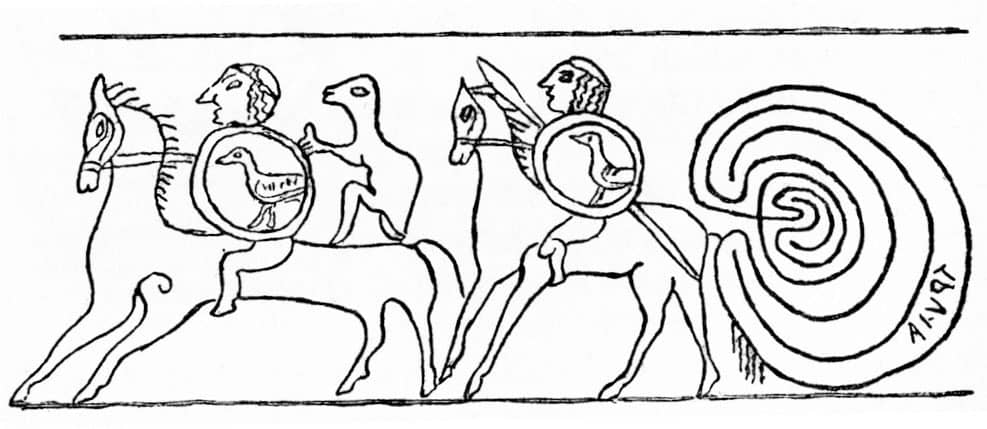

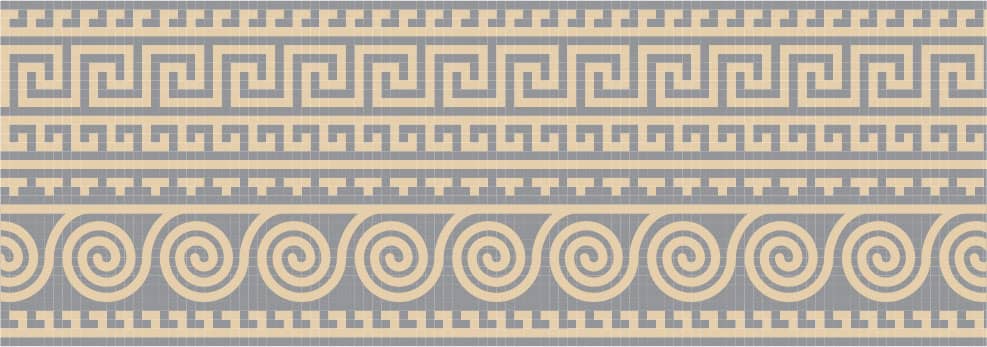

In chapter one I introduced the Etruscan vase from Tragliatella in Italy, with a small labyrinth labeled “TRVIA” or “Truia.” Discovered in 1877, this jar’s incised decorations have been the subject of much debate and wide interpretation (Fig. 7). What is being depicted here? Note the similarity between the labyrinth on the vase and the “Luzzanas Labyrinth” (shown here). A common subject for Greek pottery decoration, which leaves us in no doubt, is, of course, the Cretan legend, and especially Theseus slaying the Minotaur. A type of drinking vessel called a kylix, used at a symposium (not the academic forum we might think of today but a male drinking party) would feature the deed and would be decorated with a meandering pattern on the frame as well as with Ariadne’s thread (Fig. 8). The Greeks made much use of the meander to decorate their pottery and their buildings (Fig. 9).

Fig. 7: Detail from Etruscan vase, discovered in 1877 in Tragliatella, Italy, showing a small labyrinth labelled “TRVIA” or “Truia” (interpreted as the city of Troy).

Fig. 8: Illustration of Greek kylix decoration.

Fig. 9: Examples of Greek meander patterns.

So far, I have tended to use the word “labyrinth” rather than “maze,” and while the terms are interchangeable, the early history shows us that all designs featured one path to the center, often through many twists, turns, and repeats, and through more than one segment. This did not mean there is no room for confusion as we seek to understand the various historical meanings and purposes of labyrinths. Pliny himself may again confound when he distinguishes between the different types of design and refers to those “formed in the fields for the entertainment of children,” and “an edifice with many doors and galleries which mislead the visitor.” It has also been suggested the labyrinth pattern, marked on the ground, was used as a test of skill for boys or soldiers on horseback. The Roman labyrinth is not a “maze” in the way we would know it today. That emerged much later, during medieval times.

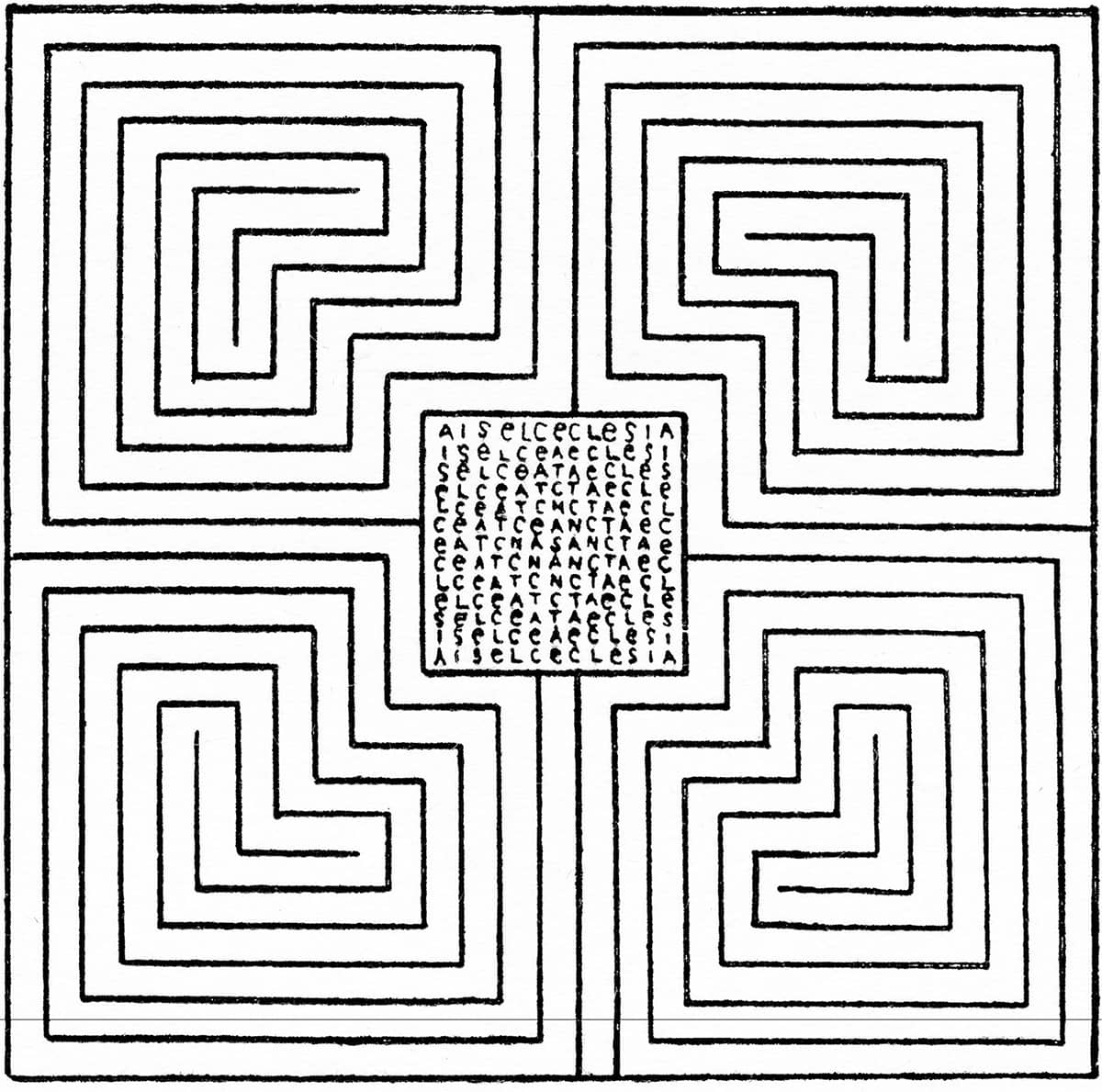

In 313 CE, the Western Roman Emperor Constantine I and Licinius, who controlled the Balkans, passed the Edict of Milan, under which Christianity was given a legal status (it did not become the official religion of Rome until 380 CE). From around that time, the labyrinth as a symbol became Christianized. The earliest example of this is the labyrinth of St. Reparatus of El Asnam, Algeria (formerly Orleansville and, before that, the ancient Roman city of Castellum Tingitanum). Laid in 324 CE, the center does not contain an image of the Cretan legend but instead contains a palindrome of “Sancta Eclesia,” meaning “Holy Church.” With the appearance of a crossword puzzle, whether you read it forward, backward, vertically, or horizontally, it always says the same thing (shown here).

The Labyrinth of St. Reparatus of El Asnam, Algeria (formerly Orleansville and, before that, the ancient Roman city of Castellum Tingitanum). Laid in 324 CE, the center contains a palindrome of “Sancta Eclesia,” meaning “Holy Church.”

In chapter four about the medieval maze, we will further explore the rapid growth of Christian labyrinths and the emergence of mazes as we know them today. Before doing so, we will turn in chapter three to the curious history of the spiritual maze in ancient cultures around the world.

COMBINATION LABYRINTH

Trace the path through this labyrinth which combines the meander, spiral, and serpentine patterns.

GREEK KYLIX MAZE

Based on the Greek kylix, this puzzle requires you to find an uninterrupted path through the checkered pattern, from the arrow at the top to the red dot at the base.

SPIRAL LABYRINTH

Follow the path through all the spirals of this labyrinthine pattern from the entrance bottom left.

SPIRAL MAZE

Choose an entrance at the top to find a clear pathway to the exit at the base.