CHAPTER 6:

THE ROMANTIC MAZE

Hedge mazes and garden creations

“Fountains grotesque, new trees, bespangled caves,

Echoing grottos, full of tumbling waves

And moonlight; aye, to all the mazy world

Of silvery enchantment!”

—from Endymion by John Keats (1.453-64), 1818

As we enter the period of the romantic maze, we take a moment to reflect on how we have arrived at this point. That is, how the form appears to have evolved from a simple design with a single path to a complex multipathed, or multicursal, design. We may recognize the latter as the forerunner of the maze we know today. When and how did it change? Or did it? Author Geoffrey Ashe, in Labyrinths and Mazes, poses the question: can we trace an evolution from unicursal labyrinths to multicursal mazes? As he points out, the Cretan legend itself has a strange ambiguity. If the labyrinth had simply been a backtracking spiral, then surely Theseus would not have needed Ariadne’s thread to find his way out! Ashe believes the ambiguity is rooted not in any pattern on paper but in the dance, with convolutions that may have confused the labyrinth’s image. This was then compounded by later misunderstandings over many years as the form changed and moved in different directions. In chapter eight we will explore aspects of our emotional and intellectual engagement with labyrinths and mazes.

The romantic maze in the context of our curious history is centered on the labyrinth as a garden ornament, the notion of which goes back as far as the writings of Pliny the Elder, which I noted in chapter two. And the manuscripts mentioned in chapter four on the medieval maze provided inspiration not only for church and cathedral builders but also for royal architects and designers. Without going into the detailed history of gardens per se, it would be helpful just to note that the medieval enclosed, or walled garden, the hortus conclus, evolved from prayer and physic gardens in monasteries across Europe.

In The Decameron, Giovanni Boccaccio uses the garden to portray a peaceful and natural refuge from the plague. References to garden labyrinths first appeared during the late twelfth century. A famous medieval legend, embellished in ballads and plays over the centuries, is that of “Fair Rosamund’s Bower.” It is suggested that the tale of Rosamund Clifford (Fig. 1), the mistress of King Henry II of England, was first written down by John Brompton, Abbot of the Jervaulx in York, in 1151, who described the King’s residence for Rosamund as “something similar to the home of Daedalus, so that the queen could not reach the girl easily.” Much later, in 1686, English natural philosopher and archeologist John Aubrey recalls in Remaines that his nurse used to sing the following verses to him:

Fig. 1: Painting of Fair Rosamund in Her Bower by Scottish artist William Bell Scott.

Yea, Rosamond, fair Rosamond,

Her name was called so,

To whom dame Elinor our Queene

Was known a deadly foe,

The King therefore for her defence

Against the furious Queene

At Woodstocke builded such a Bower

The like was never seen.

Most curiously that Bower was built

Of stone and timber strong.

An hundered and fifty dores

Did to this Bower belong,

And they so cunningly contriv’d

With turnings round about

That none but with a clew of thread

Could enter in or out.

Sited where Blenheim Palace now stands, Woodstock was the first enclosed park in England. Rosamund died in 1176, before reaching her thirtieth birthday. Some versions of the story have Henry’s Queen, Eleanor of Aquitaine, murdering her in the maze by forcing her to choose between a dagger and poison. Henry and Rosamund’s family paid for her tomb, which is laid in the choir of the monastery church at Godstowe. It became a shrine, which displeased the Bishop of Lincoln, who had it removed to the cemetery, and in the sixteenth century it was destroyed in the dissolution of the monasteries during the reign of Henry VIII of England. It seems likely that Rosamund’s bower, if it existed at all, was a labyrinthine building rather than an evergreen maze, despite the many different interpretations. There is, however, something distinctly dreamy about a garden, and it is not surprising if tragic legends such as that of Fair Rosamund were romanticized. It is suggested that the Italian poet Petrarch first linked labyrinths to love in the fourteenth century when he wrote 366 poems about his unrequited love for Laura de Noves:

Thirteen twenty-seven, at the beginning

of the first hour, on the sixth day of April,

I entered the labyrinth, and see no escape.

—from Il Canzoniere or the Rime Sparse by Petrarch

King Charles V of France had a “Daedalus” in his palace garden at the Hotel Saint-Paul in Paris, which was destroyed by Bedford, the English regent, in 1431, though, again, we cannot be absolutely sure this was an evergreen as opposed to an architectural feature. By 1494, however, a knot in a garden called a “mase” was a commonplace feature. And, in 1499, the Italian philosopher Francesco Colonna imagines an ideal garden with geometrical labyrinthine shapes in Hypnerotomachia Poliphili (Poliphilo’s Strife of Love in a Dream). During the Renaissance the creation of private gardens became popular with European aristocracy.

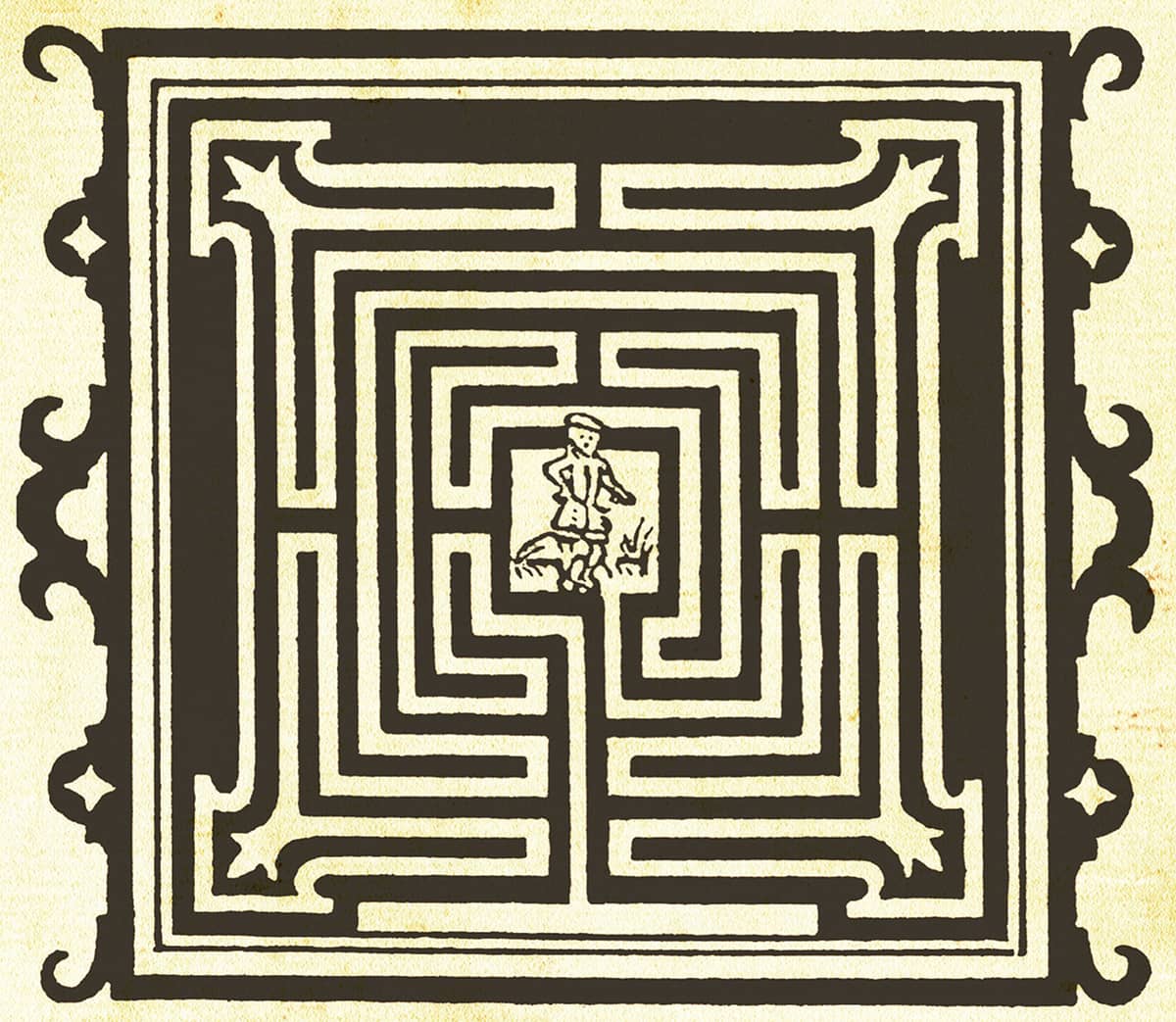

With the advent of the printing press, labyrinth designs were shared more widely. Many books were published on gardening and on architectural patterns, such as the Libri cinque d’architettura by Sebastiano Serlio (1537) and Le thesor des parterres de l’univers (1579) by Loris. A popular English Tudor gardening book is A Moste Briefe and Pleasaunt Treatyse Teachynge How to Dress, Sowe and Set a Garden (1563) by Thomas Hyll, (or Hill). Hill republished this book twice with different titles, The Profitable Art of Gardening (1568) and The Gardener’s Labyrinth (1577). The latter was published under the pseudonym Didymus (Thomas) Mountain (Hill). Hill considered mazes to be “as proper adornments upon pleasure to a Garden,” although he did acknowledge that they were not to everyone’s liking (see here).

A 1573 book by Stefano Duperac on the gardens of the Villa d’Este at Tivoli, said to be the finest in Europe, shows four rectangular labyrinths, most likely planted with dwarf shrubs, which were very fashionable at the time. In 1602, English printer Adam Islip produced an interesting square and circle maze design in The Orchard and the Garden, subsequently used by William Waldorf Astor many years later in 1905, when planting a hedge maze at Hever Castle in Kent, England (shown here). Many mazes were planted with herbs, such as thyme, marjoram, and lavender, and, of course, the endurable and robust boxwood—they were much in vogue.

“Here by the way (Gentle Reader) I do place … Mazes … as proper adornments upon pleasure to a Garden,” Thomas Hill.

“Mazes and Knots aptly made do much set forth a garden which neverthelesse, I referre to your discretion for that not all person be of like abilitie,” Thomas Hill.

Illustration of Adam Islip’s design from 1602.

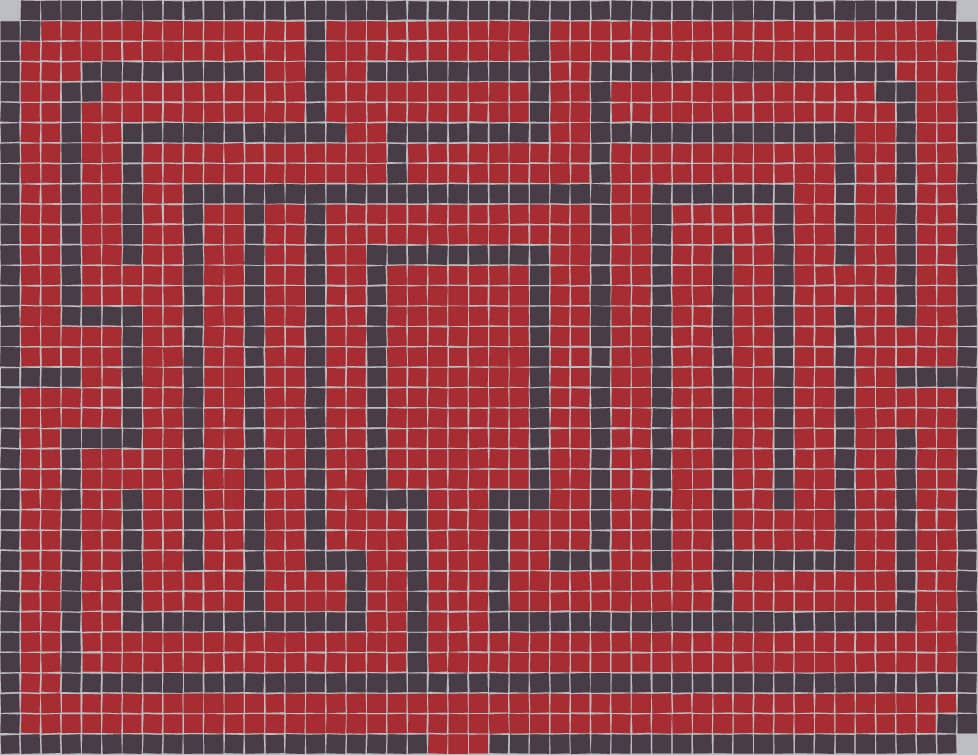

Illustration of a simply-connected maze planted at Krenkerup, Denmark, in 1877.

William Lawson promoted mazes in his popular gardening book, A New Orchard and Garden (1618 and subsequent editions), and declared that “The number of Formes, Mazes and Knots is so great, and Men are so diversly delighted” and “Mazes well framed a man’s height may perhaps make your friend wander in gathering of berries, till he cannot recover himself without your help.” Pope Clement X ordered the construction of a maze in the hidden garden at the Villa Altiéri, and is reported to have amused himself with watching his servants as they grappled with its paths formed of thick and high boxtrees. Maze barriers had certainly begun to rise toward the end of the sixteenth century.

How did the design of these garden mazes shape up? Where maze patterns were included, a simple, unicursal form was sometimes followed though in many instances very elaborate mazes were laid out. The “puzzle” maze that is familiar to us today had already emerged by the fifteenth century. Saward tells us that the earliest, “simply-connected” mazes in medieval times were made by rearranging the walls of a labyrinth to create a pathway with choices. The maze was formed with one continuous wall that has many junctions and branches, and as long as the perimeter at the entrance was connected to the wall surrounding the goal, the maze could easily be solved. All you needed to do was keep one hand in contact with the wall (test this out shown here).

Many such mazes were created between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries, and it was not until the early nineteenth century when what Saward terms “multiply-connected” mazes became fashionable, with the goal set within an island of barriers physically unconnected to the rest of the maze. see here for examples of maze designs by German architect G. A. Boeckler from his 1664 publication, Architectura curiosa nova.

A good early example of an English hedge maze was in the garden at Theobalds in England (shown here), constructed around 1560 for Lord Burghley, who was the chief advisor to Queen Elizabeth I of England—it is interesting to note that Thomas Hill dedicated his book, The Gardener’s Labyrinth, to Burghley. Described as being “large and square, having all its walls covered with Sillery and a beautiful jet d’eau in the center,” this maze was identical to a plan in Serlio’s popular 1537 publication. It was reportedly destroyed in the early 1640s by “rebels” (English Parliamentarians, or “Roundheads,” who rebelled against Charles I, King of England, Ireland, and Scotland). Many sixteenth-century hedge mazes were destroyed, and all that remains are place names to indicate their vicinity, such as “The Maze” in Southwark, London. In 2011 the site of Theobalds (now known as Cedars Park) was restored as a public park with a replica maze.

The prevailing political climate was not the only factor that affected the popularity, or otherwise, of mazes and labyrinths in Europe. The sixteenth and seventeenth centuries saw a change in gardening fashion with the onset of Mannerism, which emerged out of a reaction to Classicism and the High Renaissance. Mannerism (a style the English rebels would not have approved of) lasted around a century in Italy before the introduction of Baroque. It lasted slightly longer in other parts of Europe.

Turning against the traditional artistic canon, the Mannerist garden was larger, grander, and filled with statues, grottos, fountains, and other virtuoso water features. In this context the employment of labyrinths and mazes became increasingly secular. The order of the day was not devotion but novelty and allusion, created to impress friends and associates. A Mannerist garden was alive with movement and drama, a real jardin de plaisance. Sophisticated examples of mazes comprising hedges, flowerbeds, bushes, and paths sprang up in the gardens of villas, castles, and palaces across Europe. People did not just walk these exotic verdant creations, but played games, made music, made love, and even dueled. Within these boundaries it seemed there were few boundaries!

The “Labyrinthine of Versailles,” built between 1669 and 1677 for King Louis XIV of France and designed by French landscape architect André Le Nôtre, was laid out as a series of interconnecting paths (shown here). The unconventional design featured blocks comprising allegorical fountains, over three hundred painted metal animal sculptures, and thirty-nine hydraulic statues inspired by Aesop’s fables such as “The Hare and the Tortoise.” The purpose of these blocks, placed at various intersections, was to provide an entertaining walk rather than a puzzle to be solved, although visitors were supposed to pass all the sculptures in the right order.

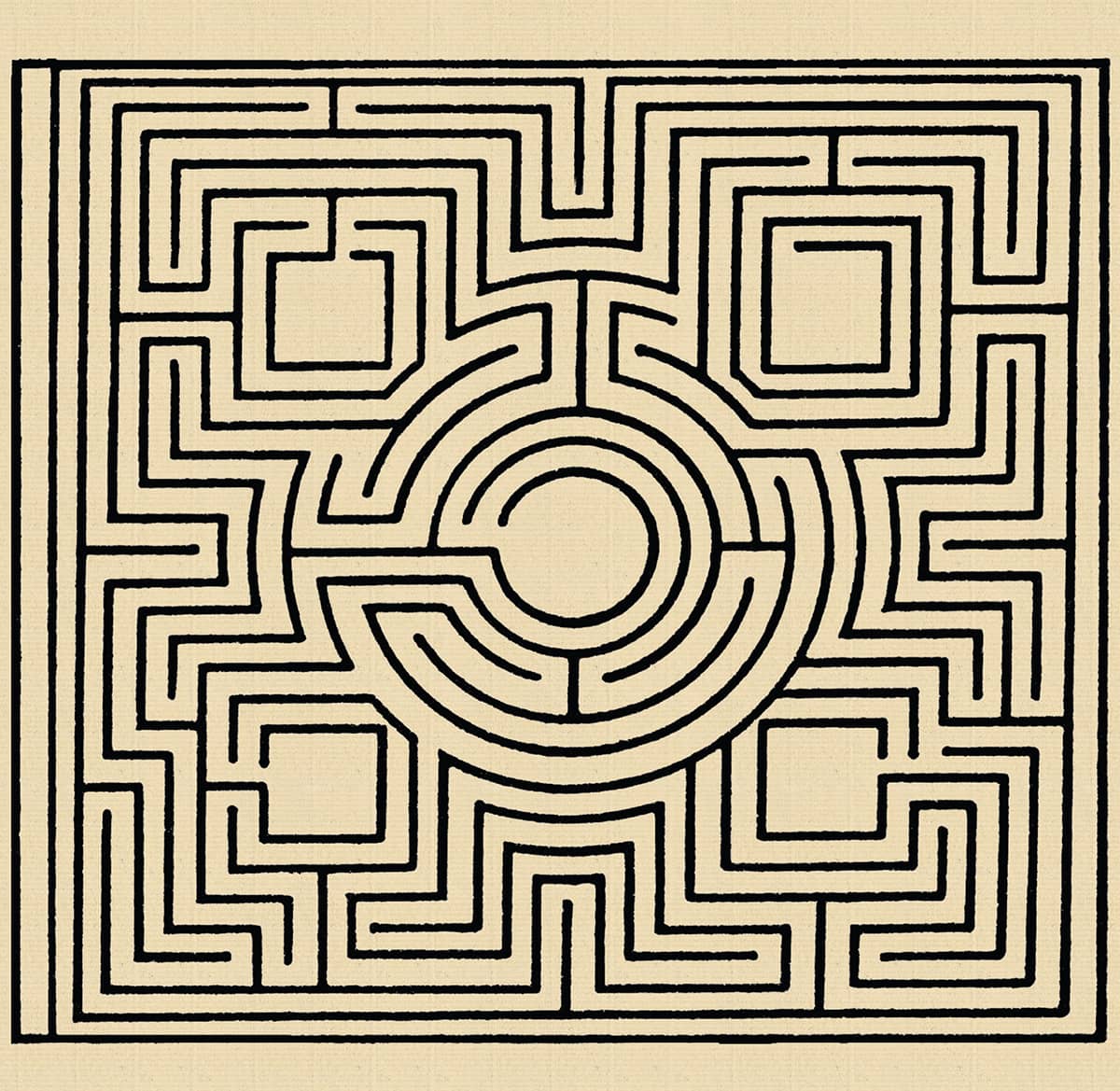

Maze designs by G. A. Boeckler, 1664.

Maze designs by G. A. Boeckler, 1664.

Maze design by G. A. Boeckler, 1664.

Maze design by G. A. Boeckler, 1664.

Illustration of the maze at Theobalds, England, created around 1560, and in 2011 restored as a replica maze on the same site, now known as Cedars Park.

Illustration of the block maze at Versailles in France, destroyed in 1775.

The water for the fountains was conveyed from the river Seine by a contraption called the “Machine de Marli.” The two statues at the entrance were of Aesop and Cupid, and the French author Charles Perrault wrote, “Aesop has a roll of paper which he shows to Love who has a ball of thread, as if to say that if God has committed men to troublesome labyrinths, there is no secret to getting out as long as Love is accompanied by wisdom, of which Aesop in his fables teaches the path.”

While the “Versailles’ Labyrinthine” was destroyed in 1775, its design inspired several block mazes in other parts of Europe, as well as mazes that were created by simply cutting pathways through areas of woodland. A replica was planted at Friar Park near London, with thirty-nine sundials placed at the path intersections. A water maze was created at Greenwich in London, probably designed by the French Huguenot engineer Salomon de Caus, who had a fascination with hydraulic automata, but, unfortunately, no plan of this survives. Henrietta Maria, Queen Consort of King Charles I, brought the well-known French gardener André Mollet to England to design her gardens. He created a labyrinth at Wimbledon using “young trees and sprays of good growth and height, cut out into several meanders, circles, semicircles, windings and intricate turnings.” see here for examples of maze designs by Mollet.

Simple meanders, with no matter how many windings, were going out of fashion. Interlinked paths, junctions, and blind allies were becoming more popular. At the same time in the Netherlands, puzzle hedge mazes, known as “Doolhof,” were becoming a public attraction. Derived from the medieval labyrinth design, these mazes were complex. At the Palace of Het Oude Loo, William of Orange and Mary—the future King William III and Queen Mary II of England, Ireland, and Scotland—had their own mazes constructed. His had clipped hedges with sandy walks between, and hers was decorated with fountains and statues. Once in England, William and Mary created in 1690 what is probably the most famous hedge maze of all, at Hampton Court Palace.

Illustration of Mollet’s maze design from 1651.

Illustration of Mollet’s maze design from 1651.

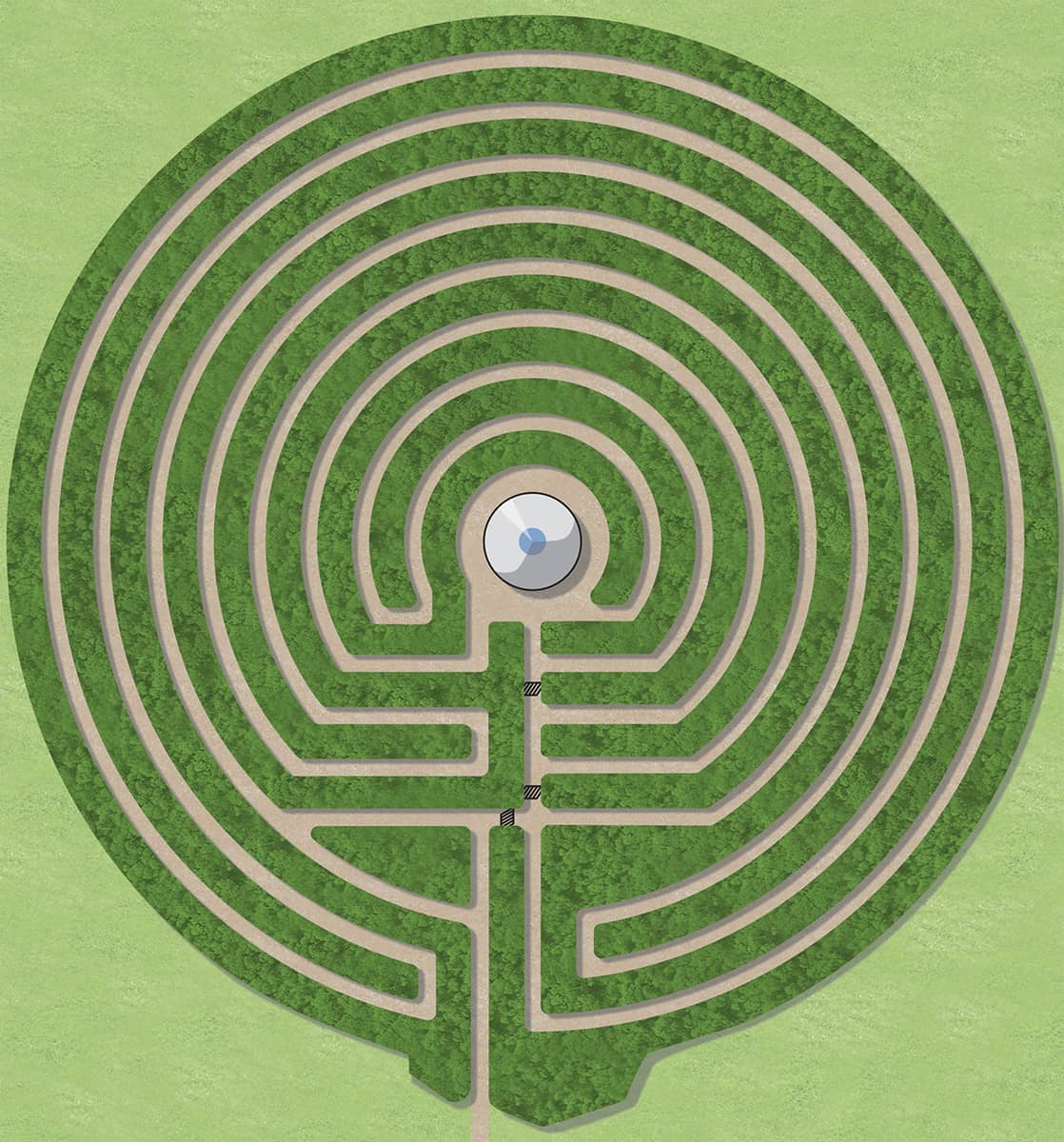

The “Hampton Court Maze” (shown here), planted between 1689 and 1695 by George London and Henry Wise in the palace “wilderness” gardens, may well have displaced an older maze. Originally constructed of hornbeam, it has been replanted several times over the years. The current maze, built with yew hedges, has over a 1/2 mile (.8 km) of paths. W.H. Matthews describes the maze as having a neat and symmetrical pattern “with quite sufficient of the puzzle about it to sustain interest and to cause amusement.” Its path is “without a needless and tedious excess of intricacy.” In 1718 English garden designer Stephen Switzer, and former pupil to London and Wise, writes about the maze in Iconographia Rustica saying “there are but three or four false stops, or methods to loose or perplex the rambler in his going in.” Another clearly unimpressed onlooker, Professor Rouse Ball, English historian of mathematics in his 1892 publication Mathematical Recreations and Essays, describes the “Hampton Court Maze” as being of “indifferent construction” and declares, “No labyrinth is worthy of the name of a puzzle which can be threaded in this way.”

There is a charming tale in English author Jerome K. Jerome’s 1889 humorous novel, Three Men in a Boat (To Say Nothing of the Dog), of Harris attempting to escort his “country cousin” around this maze. He says with confidence, “We’ll just go in here, so that you can say you’ve been, but it’s very simple. It’s absurd to call it a maze. You keep on taking the first turning to the right. We’ll just walk round for ten minutes, and then go and get some lunch.” Then, some time later, a hapless Harris has to call for help. Ironically, if he had followed his own instructions to the letter, he would have been fine. A similar thing happens to the character Larry Weller in Carol Shield’s 1997 novel Larry’s Party, when he takes every wrong turning at Hampton Court. Larry goes on to develop a “maze craze” and becomes a maze designer.

The fact that Hampton Court Palace is often considered to be one of the most haunted buildings in England may well add more excitement to this maze experience. Over the centuries people have told stories of unexplained sounds, strange smells, and ghostly sightings throughout this intriguing Tudor palace. Another surviving hedge maze, planted at around the same time and very similar in design, is in the grounds of Egeskov Castle in Denmark. Hedge mazes were popular in Denmark also, and the fact that some examples have survived over the years is thanks to their wealthy and influential patrons.

These major verdurous installations required a lot of time and money for their upkeep. This, and the ever-changing fashions in gardening, left them rather exposed to potential destruction. During the eighteenth century, the great English landscape gardener Lancelot “Capability” Brown popularized a trend for informal and “natural” landscapes at private houses. It was out with geometric features and in with sinuous or irregular lines. As a consequence, some two hundred formal gardens, and many hedge mazes, were destroyed. Ironically, as master gardener at Hampton Court Palace, Capability Brown lived for twenty years in the house alongside the maze. It is understood that the King expressly ordered him not to interfere with it. Of a more flowing and naturalistic design, which may or may not have met with Capability Brown’s approval, was a hillside maze created in 1833 by Alfred Fox in his garden at Glendurgan in England as a “living puzzle” for the entertainment of his twelve children (shown here). Now fully restored, the gardens and the maze are owned by Britain’s National Trust and are enjoyed by the general public.

The fact that the public can do this today is down to yet another milestone in our curious history. From the early nineteenth century, again across Europe, not only were gardening tastes reverting back to formality, but public parks and recreation grounds were being created. Many publicly accessible mazes were planted right up to the start of the First World War, and then the mood understandably changed. We will look at the period of the modern maze, from around 1900 to the present day, in the next chapter. Meanwhile, in the 1820s, the fourth Earl Stanhope planted a new type of maze at his stately home in Chevening, England, providing visitors with a fresh challenge (shown here).

Illustration of the “Hampton Court Maze”

“We’ll just go in here, so that you can say you’ve been, but it’s very simple. It’s absurd to call it a maze. You keep on taking the first turning to the right. We’ll just walk round for ten minutes, and then go and get some lunch,” said Harris.

I noted multiply-connected mazes earlier, where what is often called the “right-hand” or “hand-on-wall” rule does not apply. Stanhope was the first to apply map theory to maze design. With the “Chevening Maze” and with others (he designed several), the visitor was repeatedly returned to the maze entrance if they tried to use the rule. Stanhope’s mazes contained discrete sections, or islands, of hedge within the perimeter that were not connected to the center, and no dead-ends. The key to solving the maze was to walk—to walk and walk until you reached your goal. In addition, these mazes offered quiet nooks and corners, which furnished a modicum of privacy for a secret meeting. Raised platforms were erected overlooking especially complex mazes, with maze “lifeguards,” who could be called upon to provide directions if needed. I wonder how many visitors had to be rescued, or, then again, how many were happy to be left to their romantic tryst!

In Victorian England, “tea-garden” mazes were planted where ladies of leisure gathered to take afternoon tea and a stroll. Hedge mazes were certainly a popular form of entertainment. Neat mazes with Italianate-type designs sited in formal gardens were fashionable during this period. A nice example designed by W.H. Nesfield was planted in the garden of the Royal Horticultural Society at South Kensington in London, opened in 1861 (shown here). Sadly, this was destroyed in 1913 with the construction of the Science Museum. However, around twenty-five hedge mazes remain in the Netherlands, some of which are old and some replicas of the “Hampton Court Maze.” There were also replicas in Australia (planted in 1862 and destroyed in 1954) and New Zealand (planted in 1911 and also now gone). There are other examples in Germany, France, Belgium, and Denmark, and in 1863, a maze was planted in Iveagh, Dublin, with its own grotto and fountains.

Saffron Walden in England, home to the turf maze that we looked at in the last chapter, has a delightful Italianate hedge maze, accompanied by a pavilion, statues, seating, and a viewing platform (shown here). Work to create this maze in the Bridge End Gardens began in 1838 to 1839 and was completed in the mid-nineteenth century. The gardens were started by Atkinson Francis Gibson of Saffron Walden and continued by his son Francis. We know that Gibson was a member of the Royal Botanic Society, alongside W.H. Nesfield, who had also designed the Italianate maze featured at the Great Exhibition of 1851.

By 1949 the “Saffron Walden Maze” had fallen into neglect, and it was not until 1984 that a restoration was instigated by Tony Collins and John Bosworth, which entailed a full archaeological survey followed by a total replanting of yew trees. The survey uncovered the remains of Victorian wine bottles and many oyster shells, perhaps revealing the extent to which this charming puzzle was enjoyed! In 1991 the newly restored maze was officially reopened by the great-great grandson of Francis Gibson, Mr. Anthony Fry.

There was also a nineteenth-century revival in church labyrinths, and many examples we find in Europe were constructed during this period. The English architect Sir George Gilbert Scott included a labyrinth in the restoration of Ely Cathedral in 1870 (shown here). Located beneath the west tower, it has a design inspired by the former labyrinth at Rheims Cathedral in France and measures over 20 feet (6 m) across. In 1981 this design was copied in the porch of the cathedral in Pietermaritzburg, South Africa. A smaller but nevertheless “curious little pavement maze,” according to Saward, was laid at Bourn Church, England, in 1875 (Fig. 2). As Saward observes, the construction of the railways allowed cheap, efficient transportation of building materials and enabled architects to travel widely. New artistic movements, such as the Arts and Crafts, also helped to generate public interest in medieval art forms.

Fig. 2: Illustration of the tile maze in Bourn Church, England.

Before we go on to explore the modern maze in chapter seven, let us look beyond Europe to examples created in China, Africa, and North America. We should note that during the era of the romantic maze, up to the First World War, a number of European nations had ongoing colonial interests in other parts of the world. Hedge mazes, very often based on the Hampton Court design, were created in Sierra Leone in Africa, on the island of Bermuda, as well as Australia and New Zealand. These were mainly located in public botanical gardens and governmental gardens and, sadly, none survive. In eighteenth-century China, the Italian Jesuit priest, architect, and painter Giuseppe Castiglione was commissioned to create a garden maze for the Emperor Qianlong at the Imperial Court in Peking (Beijing). His creation, made with high brick walls and not hedges, survived until 1860, when it was destroyed by Anglo-French troops. It was rebuilt from 1977–92.

In Harmony, Pennsylvania, we find the first recorded hedge maze in North America (shown here). “Harmony” (or “Harmonie”) was an early-nineteenth-century settlement of German Protestants led by George Rapp from 1803–4. In 1814 they founded a second settlement, New Harmony, in Indiana (the Scottish socialist Robert Owen then founded a Utopian colony there in 1824). And, in 1825, a third settlement was founded at Economy (now Ambridge) in Pennsylvania. All three had mazes, although these were essentially labyrinths based on the classical form and originally designed with a single pathway to the center. Each symbolized the settlements’ spiritual quest, and each had a stone grotto at its goal. It was written in 1822 that “the Labyrinth symbolized their belief in the early coming of the millennium. It typified their conception of the winding ways of life by which a state of true social harmony was to be attained ultimately.” It was also perceived as a “pleasure ground,” although perhaps not by the “Owenites,” who destroyed the “New Harmony Maze” in the mid-nineteenth century.

Illustration of a maze created in 1833 by Alfred Fox in his garden at Glendurgan, England, as a “living puzzle” for the entertainment of his twelve children.

A memorial commission replanted this maze in 1941, and, fortunately for us, in 2008 Robert Ferré was engaged by Historic New Harmony to help restore it. Still open to visitors, the maze is thriving. Note the twentieth-century design with three gates within the maze (introduced to allow quick access to the center without damaging the hedges). The overall design is unique.

Other nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century American examples of public mazes were found at Piedmont Park near Oakland, California (planted around 1900 and destroyed in 1920); Centennial Park in Nashville, Tennessee (planted around 1902 and destroyed around 1930); the Hotel Del Monte in Monterey, California (planted around 1880 and destroyed in the 1940s); and at the San Rafael Hotel near San Francisco (planted in 1887 and destroyed in 1928, after the hotel had burned down).

It is suggested that from the 1880s to around 1930, Americans preferred not to visit a publicly accessed maze and mix with the hoi polloi and had their own created in their private gardens. Boxwood mazes were fashionable in the southern states, while hedge mazes were popular along the East Coast and in the Midwest. A replica of the “Hampton Court Maze” was created at Cedar Hill, near Waltham in Massachusetts (planted 1896 and eventually fell into disrepair in the early 1960s). Others were at Holly Croft in Dayton, Ohio (planted in 1927 and destroyed in the mid-1940s), and Vizcaya, near Miami, Florida. This latter example, planted between 1916 and 1922, is said to be the oldest surviving hedge maze in America. We will look at the Colonial Williamsburg hedge maze and other historical recreations from the twentieth century onward in the next chapter.

I noted earlier in this chapter that this period of the romantic maze represents a milestone in our curious history. Considering the various developments during this time, perhaps we have actually witnessed two milestones. The first being the development of publicly accessed mazes, and the second, the creation and rapid growth of puzzle mazes. This neatly moves us on to the era of the modern maze, from the early twentieth century to the present day.

Illustration of the maze at Chevening, England, planted by the fourth Earl Stanhope.

Illustration of a maze designed by W.H. Nesfield planted in the garden of the Royal Horticultural Society at South Kensington in London, opened in 1861.

Illustration of the Italianate hedge maze at Bridge End Gardens, Saffron Walden in England.

Illustration of the labyrinth in Ely Cathedral, England, designed by Sir George Gilbert Scott in 1870.

Illustration of the most recent layout of the labyrinth in New Harmony, Indiana. Gates have been introduced and the hedge close to the center has been altered to allow easier access to the inner temple.

Plan of the 1941 restoration of the “New Harmony Labyrinth.”

ORNAMENTAL MAZE

On this floral design, find a path from one of the lettered entry points (A–H) to the central “O.”