CHAPTER 7:

THE MODERN MAZE

The modern revival

Puzzle: to offer or represent to (someone) a problem difficult to solve or a situation difficult to resolve: challenge mentally; also: to exert (oneself, one’s mind, etc.) over such a problem or situation.

—Merriam-Webster

Some would say that the nineteenth century was a bleak time for labyrinths and mazes, although, as we saw in the last chapter, there were some fascinating and significant developments during the romantic period in our curious history. The end of the nineteenth century also saw the first mirror mazes, built from the late 1880s in Europe, Canada, and North America (the oldest surviving mirror maze, created in 1891, is in Prague, the Czech Republic). Mirror mazes featured in world fairs and expositions, including the 1893 World Fair in Chicago, the 1901 World Fair at Buffalo, New York State, and the 1904 St. Louis World Fair, where “The Crystal Maze” featured over 150 French–plate curved mirrors, giving grotesque reflections.

Unsurprisingly, given the First and Second World Wars and the impact of great social change in the first half of the twentieth century, many mazes were neglected and some even abandoned, especially those located in parks and gardens. While maze planting did not stop entirely, and while mirror mazes were installed in some North American amusement parks (such as Venice Pier in Southern California in 1923 and Luna Park on Coney Island in 1941), there was, in many respects, an interregnum of sixty or so years before the era of the modern maze really took off from the late 1960s, in a revival, which, despite some relatively short-lived fads concentrated in specific parts of the world, has continued bringing us the astonishing wealth of labyrinths and mazes that we can access and experience today.

The modern revival was (and is) realized in the hands of extraordinary individual innovators who garnered not only their incredibly creative and inventive minds but also a vast range of tools and materials, taking the design and construction of mazes to levels of multidimensional complexity never previously imagined.

No doubt scientific and technological advances during the twentieth century contributed to the scope of materials available to the mazemakers, who still sometimes combine traditional and modern techniques, and, more often than not, move in totally new and radical directions. The materials seem to have no bounds, from rock, soil, stone, pebbles, sand, boxwood, hornbeam, bricks, wood, water, frozen lakes, tiles, and mirrors to maize, plastic mats and tiles, concrete, cellophane, broom bristles, bamboo, floor tiles, straw bales, straws, string, shells, rope, nylon thread, beads, bottle caps, stainless steel, polycarbonate, aluminum, glass, bronze, plywood, baled hay, bamboo, wire cages, marble, chain-link fencing, inflatables, iron, magnets, coal, cardboard boxes, canvas, chalk, snow, ice, sea salt, felt, Lego bricks, modeling clay, Masonite, phosphorescent paint, laser beams, projected light, color, food cans, used tires, fallen leaves, books, resin, and thermo-plastics.

We also have remarkably intricate creations on paper (lines, words, numbers, and symbols) and on canvas, in literature, film, and television (we will be looking at mazes in modern popular culture in chapter nine). And we now have access on our screens, tablets, and smart phones to numerous online algorithmic maze generators, sometimes based on a specific theme. Solve a maze online, print it on paper, or print it as a 3-D model (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1: A 3-D maze created and printed by Hank Dietz. With 3-D printing one can produce mazes at various sizes. Photo: Hank Dietz.

There are video games, many with special labyrinth effects and themes. You may be surprised to learn that the first computer maze game was invented in 1959. Categorized as a “top-down” mainframe game, Mouse in the Maze players used a light pen to set up a maze on the monitor, with spots that represented bits of cheese or glasses of martini. A virtual mouse was then released to navigate the maze and find the objects. More games followed, particularly from the 1970s and onward, and during the 1980s “maze game” was first used as a term to describe any game in which the entire playing field was a maze. In recent years, much of the experience is customized for individual players. Enter your desired dimensions and level of complexity, and download your puzzle. Navigate your way to the next level, and the next. Pit yourself against another user anywhere in the world, a robot, or the computer itself.

No longer are labyrinths and mazes for walking just found in churches, fields, palaces, and stately homes. You will find them in spas; at retreats; research centers; universities and colleges; on beaches; in medical centers, hospitals, hospices, rehabilitation centers; at conferences; in cruise ships and museums; in playgrounds, theme, and amusement parks; in funfairs and seaside resorts; at fairs and festivals; in zoos, schools, and gymnasiums, shopping malls, prisons, and correctional facilities; and in people’s back yards. People who choose to engage with labyrinths and mazes are, of course, everywhere.

The sheer diversity of mazes and maze-making is too vast for this brief curious history. Also, this book is not a technical “how to” manual. If you want to find out more about the technical aspects or learn how to design and construct labyrinths and mazes, there are plenty of resources available, some of which are listed in the Works Cited and Notes.

Every age has its pioneers, and we have already seen a few in our curious history thus far. In a moment we will consider some twentieth- and twenty-first century groundbreakers and their creations, from the late 1960s to the present day. We cannot cover them all, as they are numerous, but we will certainly consider some important ones. Maze designing and building is now a fully recognized and acknowledged profession. We will also note significant movements, events, and societies. Before we do, however, let us dwell for a moment on what is now a North American classic.

The maze found in the Governor’s Palace gardens at Williamsburg, Virginia, is what Saward calls a “squared-up” version of the “Hampton Court Maze,” a historical replica. Planted in 1935 in Native American holly, this much-loved national institution was designed by landscape architect Arthur A. Shurcliff. Not only did Shurcliff have the perfect credentials for this project (having studied history, design, and horticulture at Harvard and having worked for “father of American landscape architecture,” Frederick Law Olmsted), he had also done his homework. He knew, for example, that “mounts” in English country gardens (small hills created for ice-houses) often had mazes planted below them because they afforded an entertaining view of guests as they navigated their way around the puzzle. Reflecting on the creative process in an article written for Landscape Architecture in 1937, he declares that in such a location “a pleasure place designed for entertainment of a more boisterous kind seemed probable.” “The Williamsburg Maze” is one of a few garden maze replicas across North America created during the twentieth century and, as we shall see, new hedge mazes do feature strongly in the modern maze revival.

The World Expo of 1967, which took place in Montreal, Canada, had a theme of “Man and his World” and included a sensory multiscreened feature (walls and floors) called In the Labyrinth that was prepared by the National Film Board of Canada. Housed in a prestressed concrete five-story building called the labyrinth pavilion, this installation was a contemporary interpretation of the Cretan legend. The pavilion comprised three main chambers. In the first, the audience experienced the sensation of dropping out into space, with the world left far below. In the second, they moved along a maze, laid out with two-way mirrored glass prisms lit up by tiny “grain of wheat” bulbs, and in the third, they encountered a multiscreen visual. All designed to take the audience on a journey that gave them an understanding of the relationship between “Man and his World.” The labyrinth pavilion attracted over 1.3 million visitors.

Also, in 1967, the English artist and writer Michael Ayrton published a mythical autobiography of Daedalus entitled The Maze Maker. A painter, sculptor, and filmmaker, Ayrton was fascinated by the Cretan legend, and, following the publication of his novel, he was invited by the American financier Armand G. Erpf to design a maze on his Catskill estate in Arkville, New York. Ayrton constructed what Fisher describes as one of the most ambitious mazes of modern time, a huge installation with two centerpieces; a bonze sculpture of the Minotaur; and a sculpture of winged Icarus leaping from his father’s shoulders to fly upward. Completed in 1969, it has 1,680 feet (512 m) of passageways and brick and stone walls running from 6 to 10 feet (1.8 to 3 m) in height, intensifying the sense of confusion. “The Arkville Maze” is depicted on Ayrton’s gravestone in Essex, England (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2: Michael Ayrton’s grave stone at St. Botolphs, Hadstock, England. Photo: T Bounford.

The 1967 World Expo, and Ayrton’s writing and subsequent commission, no doubt, contributed to the later twentieth century popular maze revival. As we move through the 1970s, we see the emergence of several significant contributors to this new wave. In 1970, the seminal 1922 text of W.H. Mathews on Mazes & Labyrinths is republished. In 1976 Janet Bord publishes Mazes and Labyrinths of the World, an excellent and informative compilation of artifacts. From the early 1970s, author Nigel Pennick began publishing books on related topics, such as geomancy—the art of analyzing the Earth’s energies flowing through the landscape (in 1990 Pennick published Mazes and Labyrinths).

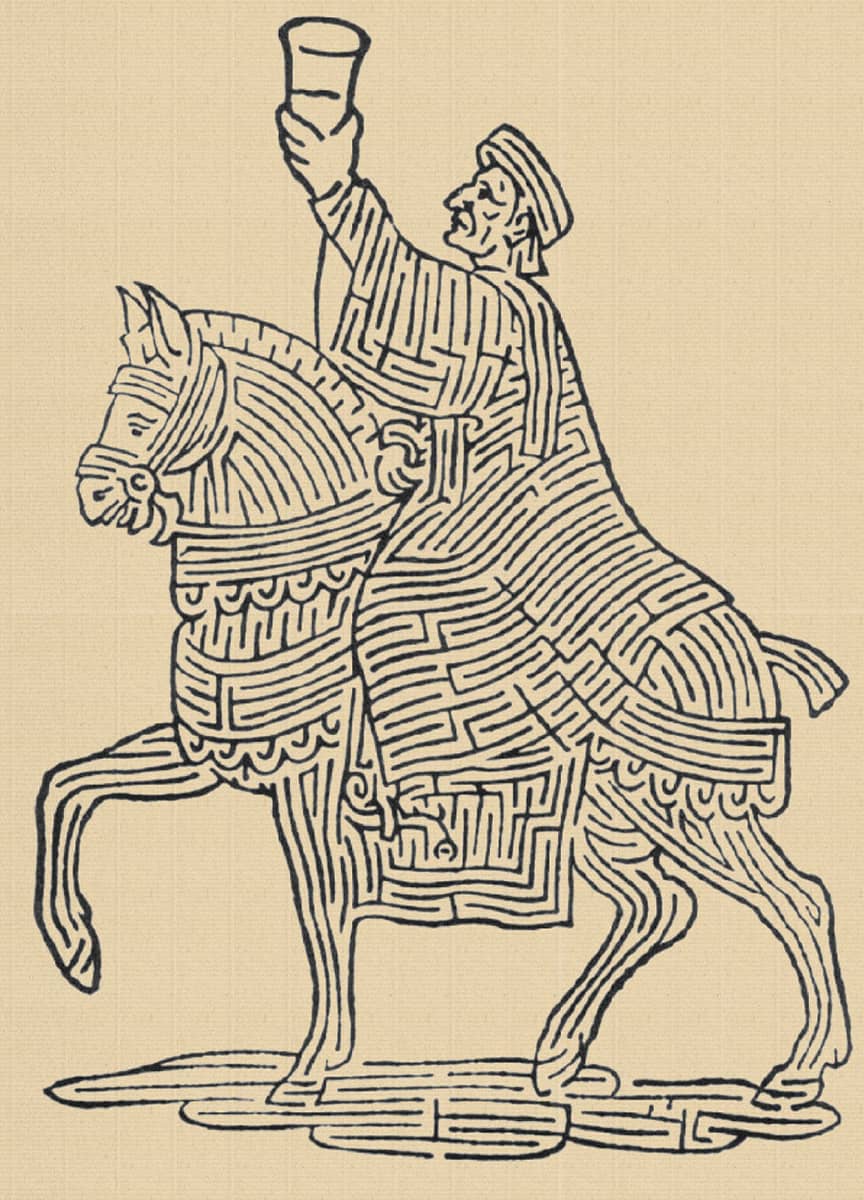

And, from the beginning of this decade, incredible works on paper were made available in books aimed at all ages. In 1971 Russian author Vladimir Koziakin published his first book, Mazes, containing forty puzzles. His designs appeared to emulate the woodcuts created by Italian architect Francesco Segala. Mainly figurative and possibly the first ever picture mazes, Segala’s work included a dog, crab, snail, and a man on a horse (Fig. 3). Koziakin’s output was prolific, with additional titles such as Greatest Car Mazes; Hardy Boys Mystery Mazes; Movie Monster Mazes; Mazewarps; Holy Zeus, Its Mythology Mazes; Amazing Amazeman in a Super Maze; Sports Mazes; and Chiller Mazes. In 1973, the American husband-and-wife team Rick and Glory Brightfield published sixty psychedelic mazes in Amazing Mazes, and in that same year, Greg Bright published his Maze Book (Fig. 4). The maze craze had well and truly begun.

Fig. 3: Illustration of on of Francesco Segala’s figurative mazes.

Fig. 4: Greg Bright’s Maze Book, 1973.

Koziakin’s puzzles were predominantly two-dimensional. The Brightfields introduced a variety of path-obscuring devices, and Greg Bright went even further, introducing “weave” mazes, very complex patterns and optical illusions. Bright writes, “I have found an increasing interest in the visual effects … All the graphic variations in this book have equal right in the composition of mazes.” His “braid” mazes featured a proliferation of paths that flowed in a spiral pattern from the center. Rather than relying upon dead-ends, he provided multiple pathway options, all of which appear equally valid.

American designer, artist, and author, Larry C. Evans began publishing maze books in the 1970s and focused on 3-D structures, often with specific architectural themes. Evans had first approached the publisher Troubador Press in 1974, and finally, in 1976, they published 3-Dimensional Mazes, quickly followed by 3-Dimensional Monster Mazes. Evans created many puzzles and published numerous posters and books including 3-D Mazes; 3-D Maze Art; Maze Cubes; Lateral Logic Mazes for the Serious Puzzler; A Super-Sneaky, Double-Crossing, Up, Down, Round & Round Maze Book; and the Great American Puzzle Factory. In 1978, American Bernard Meyers devised Supermazes No. 1, with forty-six “Imaginative and Wickedly Ingenious Mazes and Mazy Puzzles to Test the Fortitude of the Most Dedicated Mazophile.”

Naturalized American, illustrator, and graphic designer Dave Phillips (born in Macclesfield, England), is described as the world’s most ingenious maze and puzzle designer. A maze guru, he produces maze and puzzle content for books, periodicals, advertising, promotions, and computer games. In 1979 he published Mind Boggling Mazes and then went on to produce many more fantastic books, including Americana Mazes (featuring thirty-six puzzles based on American icons) and The Zen of the Labyrinth: Mazes for the Connoisseur. As declared on his website, for the first twenty years of his career he rendered his maze art with ink and paint using technical pens and airbrushes. Then, over the next twenty years, virtual tools took over, providing speed and a greater range of production techniques. Before we go on to the 1980s and 90s, then on to the turn of the century, there are two key milestones for us to note in the modern maze period of our curious history.

First, it is claimed that the earliest commercial maze was the brainchild of a Stuart Landsborough, who, having grown up in the shadow of Hampton Court, moved to Wanaka, New Zealand, at the age of twenty-five. In 1972 Landsborough had the idea of creating a “pay-by-the-head” maze (it is interesting to note that King William IV of the United Kingdom and Hanover—reigning from 1830 to 1837—had permitted his Hampton Court head gardener to charge one penny per visitor). Instead of planting hedges that would take a long time to grow and require much maintenance, Landsborough built a maze with wooden boards, all within sight of his own lounge. Over several years, he watched visitors navigating the maze and gradually refined the design, eventually adding a second story, creating what he claims to be the world’s first three-dimensional maze.

For around ten years, the maze did not make a profit but Landsborough refused to give up. He introduced a tearoom, then a puzzle center, and later a hologram gallery. He also added outdoor lighting, so he could keep the maze open at night. The story goes that one day a Japanese tourist, who was a businessman, visited the maze and subsequently commissioned Landsborough to design twenty mazes in Japan, among them the largest three-dimensional maze in the world. We will consider the Japanese trend in a moment.

The second milestone occurs in Britain, where Greg Bright tackles his two major projects during this decade. On Good Friday in 1971, Bright started digging a maze at Pilton in Somerset, England. He had no plan, but by midsummer the whole design was marked out in a one-spade depth trench. When completed, the trench was 6 feet (1.8 m) deep and extended 1 mile (1.6 km). The maze took a year to dig with the assistance of around twenty-five people. It soon became overgrown, but the project did then provide inspiration for Bright’s most famous creation. In 1973 Bright writes, “More than one person has intimated that I am obsessed with mazes. I am not, nor ever have been, nor ever will be obsessed with mazes. At one time, perhaps I felt a certain commitment towards them, but not now. Now, and for some time, I have ceased even to like mazes. I dislike them.”

This declaration does not, however, prevent Bright from taking on a major commission from the Marquis of Bath, to design and build a hedge maze at the Marquis’ stately home in Longleat, Warminster, England. Opened in 1978, Bright’s superb creation, Britain’s first three-dimensional maze (planted entirely of English yew), features complex and, at times, identical, spiraling pathways, and junctions, plus six wooden bridges and underpasses linking self-enclosed sections (note that Rouse Ball had suggested in his 1892 publication that the difficulty of a maze might be increased considerably by using bridges and tunnels). The lack of a rectangular grid simply adds to the visitor’s disorientation as they spend up to ninety minutes finding the goal. The maze covers an area of around 1.48 acres (5,989 sq m) with a total pathway length of 1.69 miles (2.72 km).

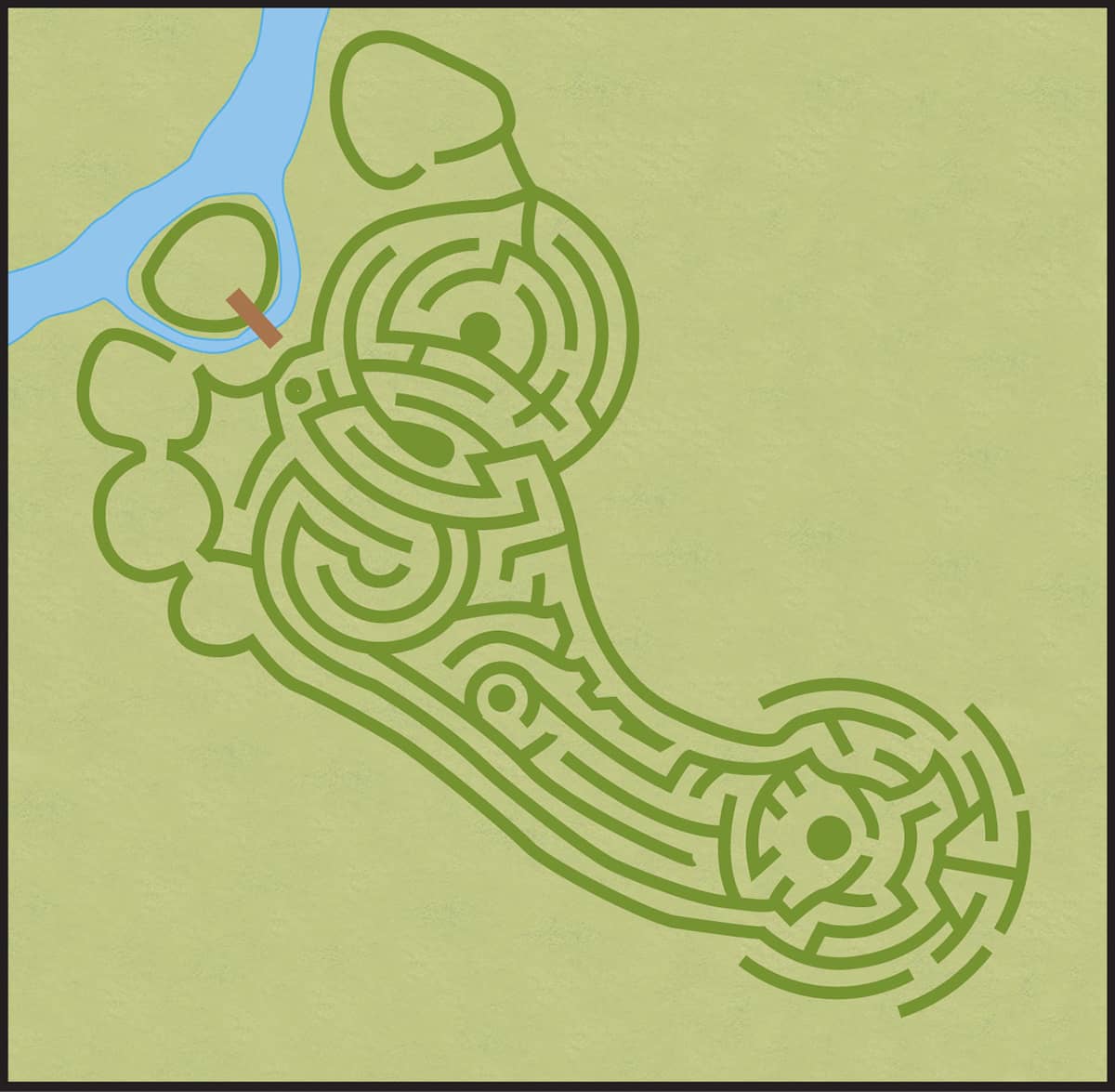

Illustration of the Imprint of Man, designed by Randoll Coate, 1975.

Bright’s “Longleat Maze” was the largest in the world for just a few years. And then, in the 1980s, the Japanese wooden panel mazes took the accolade, followed by the maize or corn mazes in America, Europe, and the Far East from the 1990s. In 1992 the Marquis added a “Maze of Love” (planted with roses) at Longleat, designed by Graham Burgess, and, in 1996, he had war veteran and English designer Randoll Coate create a maze and labyrinth based on the Cretan legend. In 1998 Adrian Fisher designed and installed “King Arthur’s Mirror Maze.” Fisher also created the Amazing Chicago’s Funhouse Maze on Navy Pier, Chicago, and much more recently, in 2017, the mirror maze entitled “Professor Crackitt’s Light Fantastic!”—a permanent installation at the Singapore Science Center featuring 105 mirror cells, interactive exhibits, experiments on light, holograms, and fake exits.

In 1975 Fisher began collaborating with Randoll Coate, the same year that Coate had his first private maze commission, entitled “The Imprint of Man,” planted in his brother-in-law’s garden in Gloucestershire, England. The design is of a giant footprint measuring 187 feet (57 m) long by 95 feet (29 m) wide, calculated to match the size of a person matching the full height of the France’s Eiffel Tower. The idea came about during a family visit to Circeo, near Rome, where Ulysses was said to have been seduced by Circe. The maze took the form of Circe’s footprint and the design (shown here) can be read from the upstairs windows of the family home.

Fisher writes that mazes on a grand scale provide superb opportunities for conveying imagery and symbolism, and that creating a new maze from conception, design, and construction to the formal opening can be a compelling experience. It is, in some ways, like painting a portrait with the age-old relationship between patron and artist. The maze designer starts with the owner’s ideas; the history of the location; and stories, traditions, and aspects of contemporary life. Practical matters such as the final dimensions, materials, and the puzzle follow later.

By 1980 the modern maze appreciation movement was growing exponentially and that year Jeff Saward founded Caerdroia, the Journal of Mazes and Labyrinths (Caerdroia translates as “Troy Town”). Still published annually, this nonprofit journal provides a forum for research and enables enthusiasts and experts alike to exchange information and keep up to date with current developments in this field. At the same time the journal was launched, the first gathering of enthusiasts took place in Britain.

We have already considered Landsborough’s innovation of a wooden three-dimensional maze in New Zealand, which triggered a 1980s maze craze in Japan. That craze peaked in 1987, with over two hundred installations. Saward, however, points to a much earlier pioneer, Louis of Bourbourg, who is 1195 built a wooden labyrinthine structure at Ardres in Flanders “containing recess within recess, room within room, turning within turning.” And another example in fourteenth-century France, a “maison dedalus,” may well have existed but we have no impression available. Along with the early mirror mazes at the turn of the twentieth century, there were also timber constructions built at exhibition grounds, funfairs, and resorts across North America and Europe. In 1902 the “House of Trouble” at the Old Orchard Beach, in Maine, was probably constructed from a prefabricated kit. These kits must have been relatively easy to put together, but would have required much maintenance, and sadly none have survived.

In 1980s Japan, the wooden mazes were on a much larger scale. Landsborough’s creations could easily accommodate 1,500 people an hour without becoming congested and had mechanisms for increasing the flow without compromising complexity. As Fisher acknowledges, in Japan people expect a maze to take as long as a feature film or football match, perhaps sixty or ninety minutes. The wooden walls of Japanese mazes can be adjusted from day to day, providing a different puzzle each week for visitors. Such “time-dimensional” mazes, with their barriers opening and closing at different times, rotating gates, and movable panels, make for an exciting and engaging maze experience where visitors would test themselves against the clock, or against each other. A version in America was the “Wooz Maze” in California, opened in 1988 and since destroyed. Fisher makes an interesting observation about the popularity of different types of mazes in different nations, comparing the single-minded Japanese approach with the more contemplative use of mazes by indigenous tribes in Arizona.

In more recent times we find Kazuo Nomura in Japan, (known as “Papa”), creator of what some have called the world’s most difficult maze, an intricate design on paper that he completed in 1983. It was subsequently “discovered” and shared by his daughter on social media in 2014, who says it took him seven years to complete. More recently he has created another, taking him just two months (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5: Detail from Kazuo Nomura’s maze.

Fisher and Coate founded Minotaur Designs, and together, as well as individually and in association with landscape architect Graham Burgess, they created many fabulous symbolic mazes on a diverse range of themes during the 1980s installed in many different locations. Two distinctive examples by Fisher are the “Archbishop’s Maze” and the “Beatles Maze.” The former, inspired by Robert Runcie’s dream on becoming the Archbishop of Canterbury in 1980, has a brick path and is imbued with Christian symbolism including an image of the Crown of Thorns. Like many modern turf mazes, grass is still a dominant feature. The route of the maze represents the path of life. In 1984 Liverpool’s International Garden Festival featured the “Beatles Maze,” one of the most popular attractions of the event with one million visitors. Opened by Her Majesty, Queen Elizabeth ll, this award-winning aquatic maze comprised a brick pathway in the shape of an apple, laid over water with a yellow submarine at the goal.

In 1990, Adrian Fisher published The Art of the Maze (with photographs by Georg Gerster), a comprehensive guide to mazes, their history, and meaning. And 1991 is designated the “Year of the Maze” by the English Tourist Board. An international conference, “Labyrinth ’91,” takes place at Saffron Walden, England, attended by enthusiasts from Britain, Europe, and America. In 1991, Sig Lonegren published his popular book, Labyrinths: Ancient Myths and Modern Uses. Having already met Saward and other enthusiasts, Lonegren started collaborating with the American Society of Dowsers, installing labyrinths at their conventions.

After several gatherings of the labyrinth “network” in the early 1990s and publication of the newsletter, “The Labyrinth Letter” by Jean Lutz, the nonprofit Labyrinth Society was founded in America in 1998, following a conference at St. Louis, Missouri. With international membership, the Society continues to thrive today, supporting those who create, maintain, and use labyrinths, and serving the global community by providing education and networking. The Society also jointly supports the Worldwide Labyrinth Locator (founded in 2004) with Veriditas—an organization founded by the Reverend Dr. Lauren Artress, who we will meet shortly in this chapter.

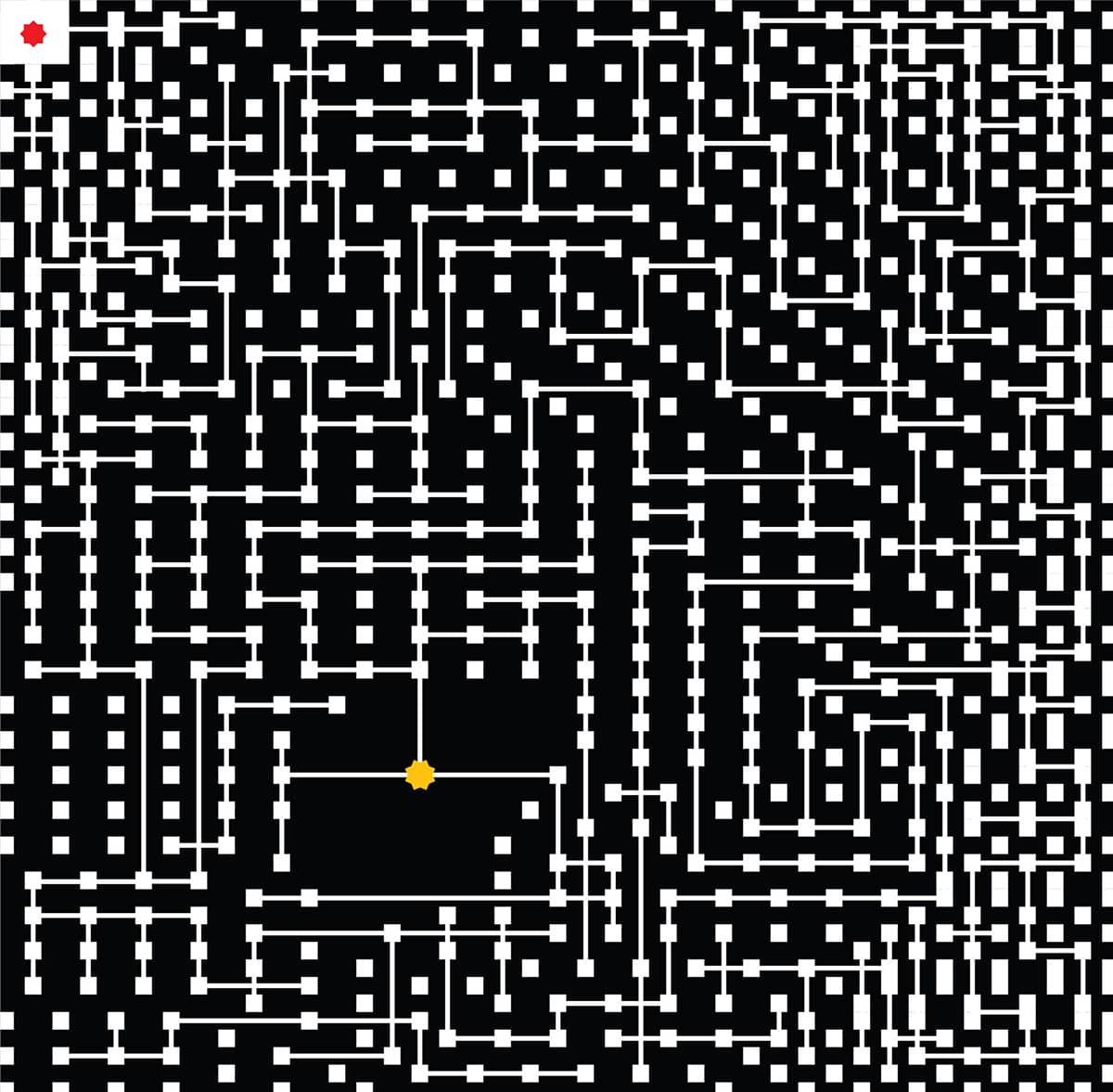

Meanwhile, let us return to puzzles. In 1985 American author and illustrator Christopher Manson published Maze: Solve the World’s Most Challenging Puzzle, with a $10,000 prize for whoever solved the book’s many puzzles. The money was eventually divided between ten people deemed to be the closest to the overall solution. American game designer Robert Abbott, inventor of what are now known as “logic mazes” (said to be named in 1999 as such by former theatrical producer Don Frantz, who created the first maize maze in 1993), published Mad Mazes in 1990 (Fig. 6). As described by Michael Keller, Abbott’s mazes are not the usual collection of simple paths and dead ends, but sequential movement puzzles in which rules govern where you can move next, and where the rules can change during the maze. Abbott’s 1997 book, Supermazes, contains mazes rated for difficulty and instructions on how to create your own rolling-cube maze.

Fig. 6: Robert Abbott’s Mad Mazes, 1990.

Abbott himself describes a logic maze as mostly a puzzle, “except it’s a maze.” It has a closed system of rules in the same way that a logic system is a closed set of rules. Abbott created many different maze formats and rightly declares, “Some mazes work best as walk-throughs, some work best in a computer program, and some even work best on the printed page.” His walk-through logic mazes, with their apparently simple rules such as only turn right or follow a specific sequence of colors, are described as surprisingly tricky but great fun. In 2005 Galen Wadzinski’s The Ultimate Maze Book also has puzzles categorized by difficulty, ranging from “No Brainers” to “Full Brain Overload.” His 3-D creations, with directional arrows, over-and-under structures, and his “key” and “ordered stop” mazes, took the printed puzzle maze to a new level of complexity.

Inspired by the 1980s teachings of Jean Houston in her Mystery Schools, Dr. Artress had decided in 1991 to re-create the “Chartres Labyrinth” in the nave of Grace Cathedral in San Francisco, where she is the Canon for Special Ministries. In 1995, Robert Ferré and Dr. Artress first meet. This is a significant moment in our curious history, as Ferré went on to create a canvas labyrinth for Dr. Artress, as well as organizing tours to Chartres. In 1996 Dr. Artress founded the nonprofit organization, Veriditas, with the aim of “peppering” the planet with labyrinths, and for several years Ferré supplied fifty canvas labyrinths a year, sold to churches and individuals all over America. In chapter eight we will explore the labyrinth experience as informed by the work of Dr. Artress, among others. Before we do so, however, we will finish this chapter by focusing on another incredible American phenomenon—maize, or corn mazes.

We tend to think of American corn mazes as having a long tradition. As early as 1972, environmental artist Richard Fleischner created a type of cornfield maze by planting sudangrass, normally used for animal feed. His first creation, “Bluff,” was followed by the “Zig Zag Maze,” both temporary installations in Rehoboth, Massachusetts. Fleischner was experimenting and created the pattern by putting down canvases where he did not want the grass to grow. “The Zig Zag Maze,” viewed from above, looked like a Greek meander.

Much later, the first American cornfield maze (of the type that is familiar to us today) was created in 1993, by Don Frantz in association with Adrian Fisher. In the shape of a Stegosaurus (with perhaps more than a nod to the movie, Jurassic Park, which premiered that year), this vast maze named “Cornelius the Cobasaurus,” became for a short while the largest in the world, according to the Guinness Book of World Records. Covering 3.3 acres (13,355 sq m), it had 1.92 miles (3.09 km) of pathway (Fig. 7). In a 2016 interview with Cherry Crest Adventure Farm, Don declares, “With more than a little patriotic pride, I decided this was an American maze, made with an American crop on an American scale.”

Fig. 7: “Cornelius the Cobasaurus,” designed by Adrian Fisher in collaboration with Don Frantz. Photo © 1993 Adrian Fisher. All rights reserved.

The key difference between “Cornelius the Cobasaurus” and Bright’s 1975 “Longleat Maze” is permanence. The corn, or maize maze, whatever size, is a temporary installation. The 1993 stegosaurus, planted at Lebanon Valley College in Annville, Pennsylvania, led to a global maize maze phenomenon that is still with us today. Frantz went on to establish the American Maze Company, which still, every year, creates extraordinary themed mazes, covering topics such as the solar system, the largest living sundial, Ford’s first car, Noah’s Ark, the Liberty Bell, the Tree of Life, and even a re-creation of George Washington crossing the Delaware River. Adrian Fisher continues to design maize mazes across the world, including America, Britain, Europe, and Australia.

By the late 1990s, maize mazes were becoming popular in North America, and today, each year, a thousand can easily be found, created by several maize maze companies and individual farmers, all unique and ambitious installations. The corn maze is indeed an integral part of American culture. We will consider what it is like to experience a giant maze in chapter eight. Planting a corn maze today takes a lot of math calculations and technology, using GPS and blueprints as well as stake flags. The process has been described as linking the dot-to-dots on the back of a cereal box but on a much larger scale. Many of these mazes have additional features that not only ease the experience (a bathroom can be essential) but also entertain.

We have already touched upon the work of maze maker Dave Phillips. At the turn of the century, Phillips returned to creating mazes and labyrinths in the real world, and he creates corn mazes as land art, laid out in America, Canada, and Britain. In 2000 he established a relationship with Maize Quest, the Corn Maze Adventure. He now provides annual corn maze designs and games for over one hundred farm attractions. His designs are used to build walk-through mazes made of hedge, live bamboo, used tires, fencing, rope, and other materials such as painted concrete. There are several companies and associations out there, in America, and in other parts of the world that provide a wide range of design, support, and marketing services for the construction and management of mazes of all kinds, not just maize mazes. It is big business.

Proclaiming the largest permanent or temporary maze these days can be tricky, and I dare not attempt it. Every year there are, of course, several contenders, and in 2017 the Guinness Book of World Records named the “Butterfly Maze” in Ningbo, Zhejiang China, as the largest permanent hedge maze, with a total area of 8.294 acres (33,564.6 sq m) and path length of 5.2 miles (8.4 km).

Before I end this brief tour of the modern maze and go on to chapter eight, where we will consider what it is like to encounter these engaging artifacts, I would just like to mention the permanent “Pineapple Garden Maze” at the Dole Plantation in Hawaii, named in 2008 by the Guinness Book of World Records as the largest maze (as we know, that accolade never lasts long). It is formed of fourteen thousand local plants (including pineapple, panax, hibiscus, and helicon) with a path stretching 21/2 miles (4 km). I must confess that what appeals to me is not the navigational clues at hidden stations, or that if you complete it in record time you can have your name inscribed at the entrance. No, like the “Maze of Love” planted with roses at Longleat, I relish the thought of a long and intoxicating stroll though rows and rows of sweet-scented flowers.

Adrian Fisher is reported as saying that a maze grabs you. When you’re in it, you can’t turn it off. You have to get to the end. I hope this curious history has also grabbed you as we move on to explore what it is like to encounter labyrinths and mazes. We will not altogether abandon the history, however, as we consider some artifacts that help to illustrate the experience. Then, finally, before revealing the gazetteer, we look at examples of mazes in modern popular culture in chapter nine, from the late nineteenth century onward.

BRIGHT CIRCLE MAZE

Find an uniterrupted path from the arrowed entry to the central circle.

METRO MAZE

Each lettered terminl links to one other–but which?

SOLID STATE MAZE

Find a continuous track from the red to the yellow component.

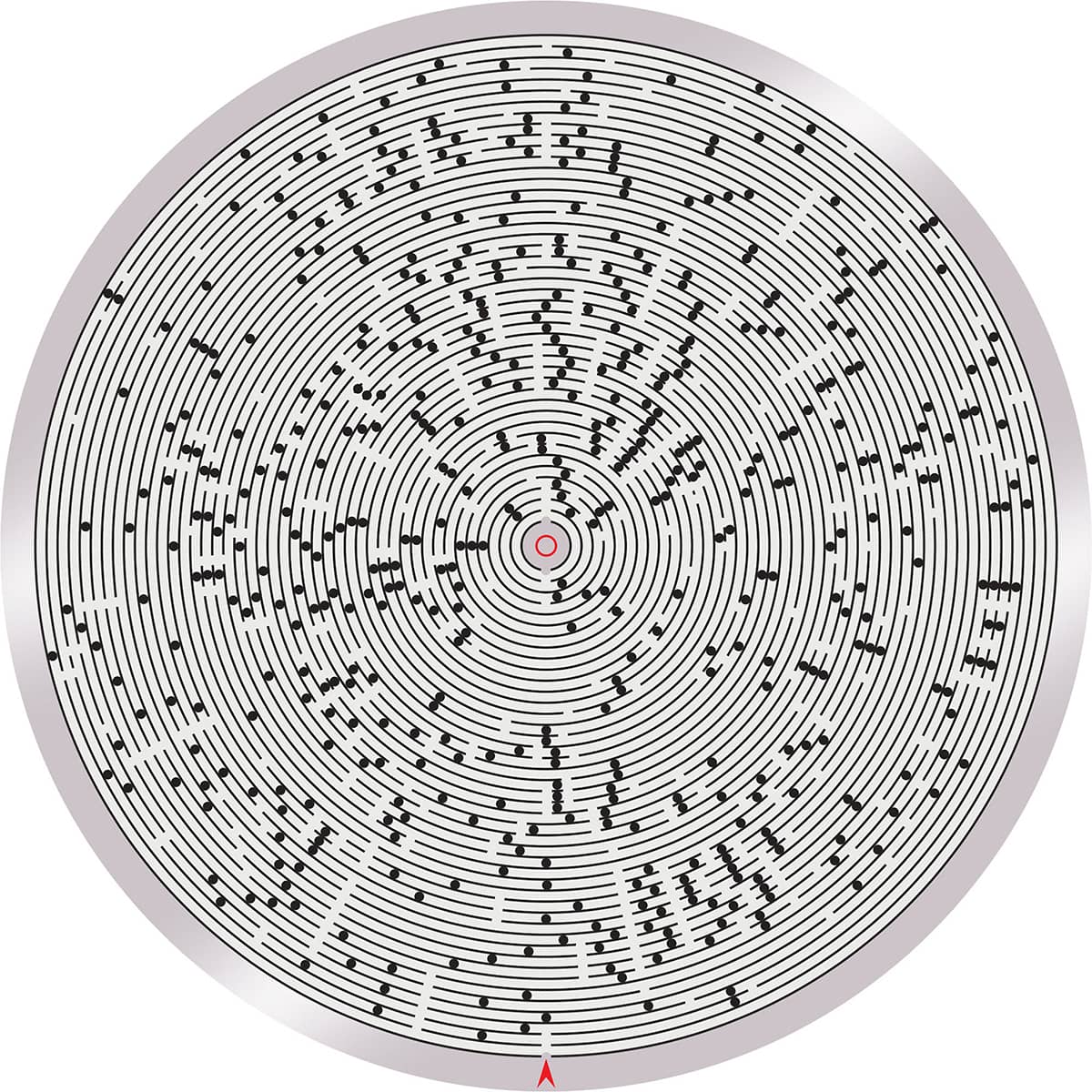

PHONOGRAPH DISK MAZE

From the entry at the base, find a clear track to the center circle.

HEXAGON MAZE

Only one of the arrowed entry points links to the center.

BEAD MAZE

Choose an entry point at the base and find the string of beads to connect to the circle at the top.

SWITCH MAZE

From top left to bottom right, you can only move from black circle to black circle or white circle to white circle following the lines, but at a switch point you must change from black to white or white to black and continue with that color until the next change, or until you reach the finish.

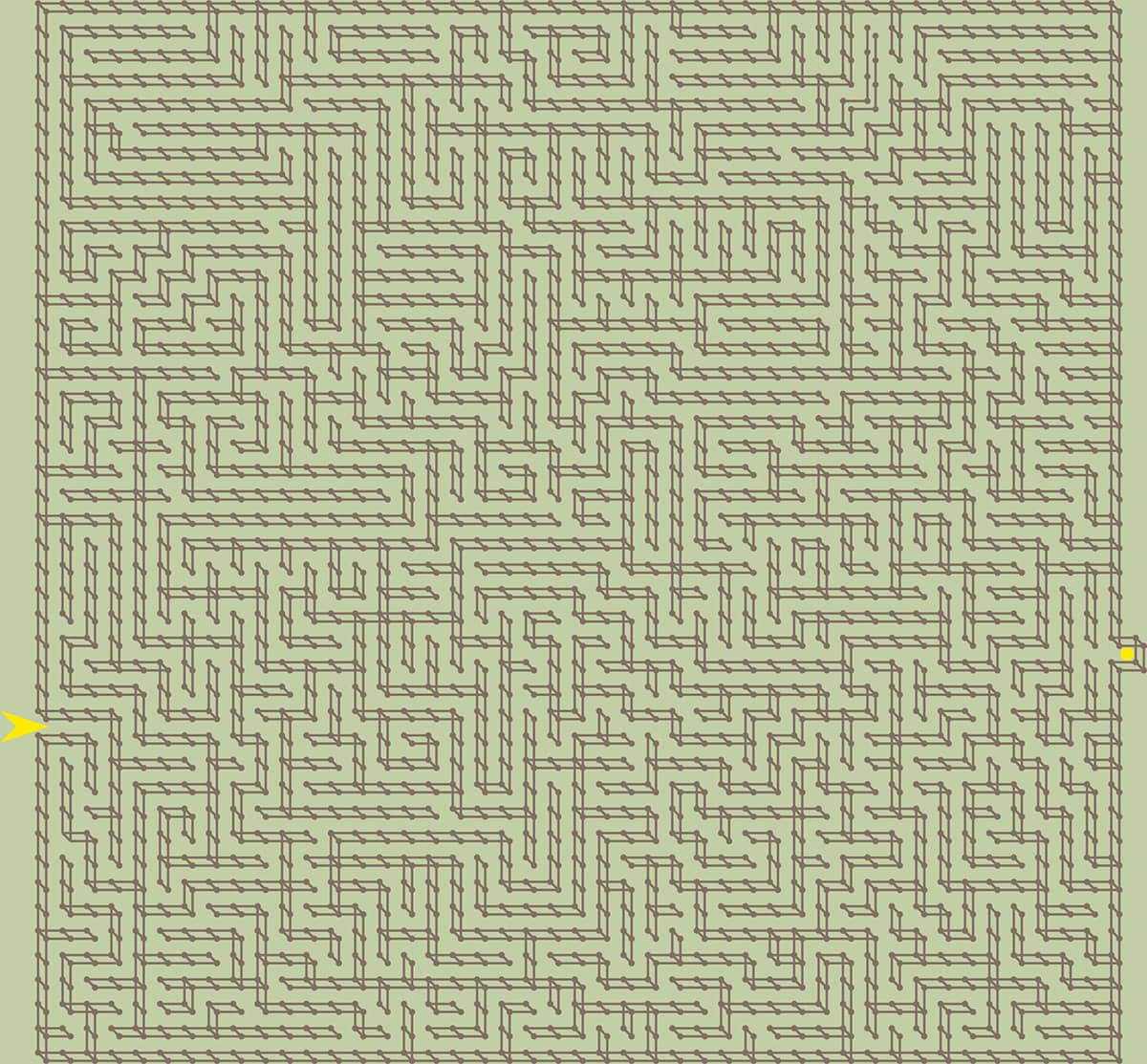

FENCE MAZE

Enter from the left side and find a pathway through to the pen on the right-hand side.

NODE MAZE

Follow a linear path from the red disk on the left side to the red diamond on the opposite side.

MANDALA MAZE

Starting at the entry point at the top, find an uninterrupted route to the adjacent exit point. You can pass under and over the shadowed “bridges.”

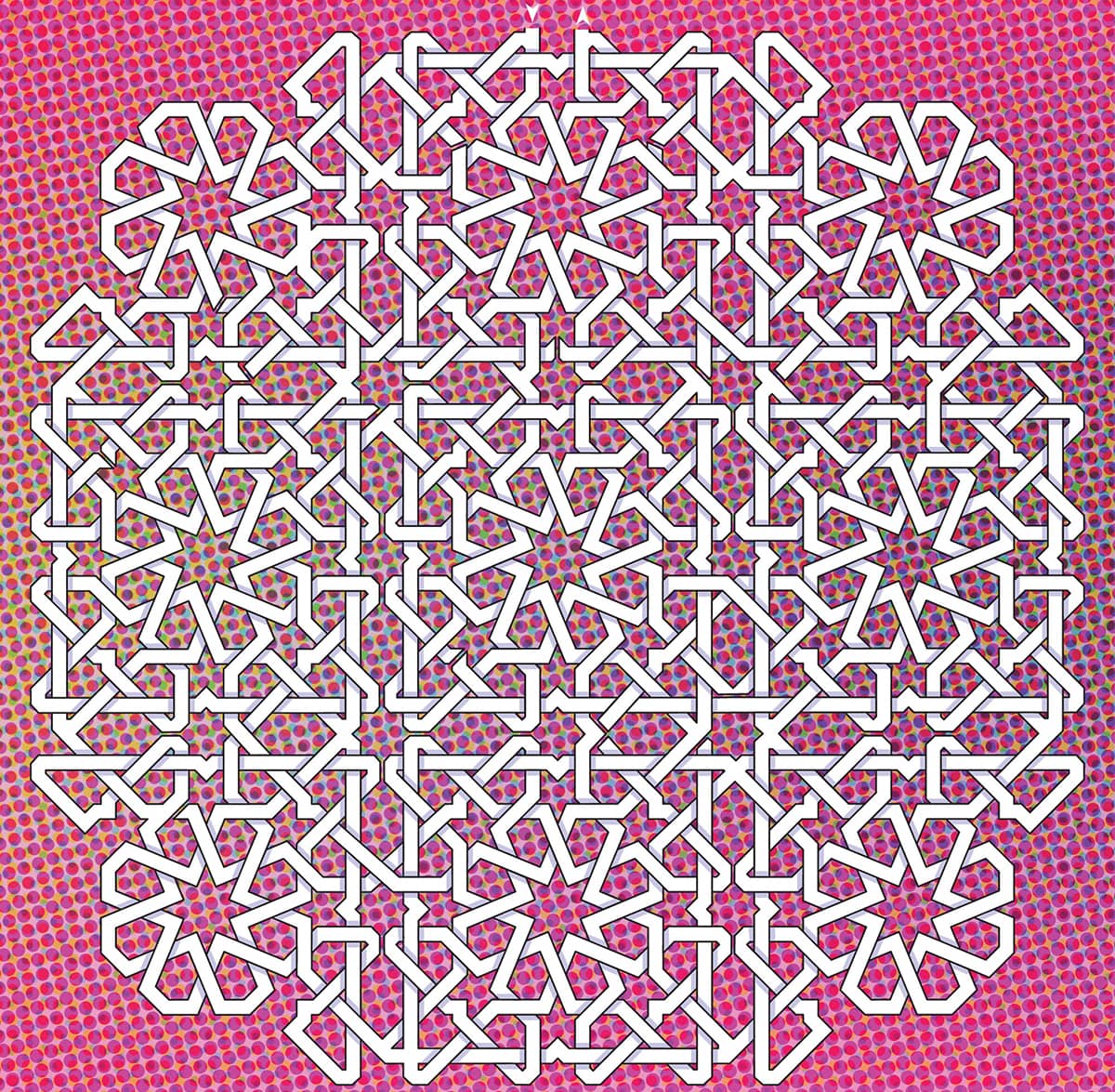

OP-ART MAZE

Find the path from the entry point at the base to the red spot in the middle.