7

The Brusilov Offensive, 1916

Russia’s Glory

Peter G. Tsouras

Kiev Opera House, 14 September 1911

The sparkling overture to Rimsky-Korsakov’s The Tale of Tsar Saltan had just concentrated every eye in the Opera House away from Tsar Nicholas II and his two eldest daughters, the Grand Duchesses Olga and Tatiana. In the stalls was Pyotr Stolypin, forty-nine, the former prime minister. Stolypin had resigned only a few months before, but the tsar wanted to show there was no bad feeling and had made the opera a command performance for his former minister.

Using his badge as a member of the Okrana, the Russian secret police, an armed Dmitri Bogrov was able to approach Stolypin, who had refused to wear his armoured vest even though the police had warned him of an assassination plot. Bogrov shot him twice in the arm and once in the chest. As the assassin was dragged away, Stolypin opened his coat to reveal a blood-soaked shirt. Looking up at the stunned Nicholas in his box, he made the sign of the cross and announced in a firm voice that he was happy to die for the tsar. He was rushed to the hospital, where the doctors were only barely able to save his life. A very long recovery was diagnosed. The tsar came to Stolypin’s hospital bed and humbled himself as he begged, ‘Forgive me.’1

Verdun, 21 February 1916

At first light 1,201 German guns erupted to hurl a continuous crushing fire on the three French divisions defending an eight-mile sector protecting the French fortress complex at Verdun. Two-thirds of the guns were heavy or mediums, the former stripped from the rest of the German armies on the Western Front. Thirty-three ammunition trains a day would be needed to feed the guns as the reinforced 5th Army attacked. It was an offensive designed by the Chief of the German General Staff, Erich von Falkenhayn, to burn out the French Army. Winston Churchill would write of it:

It was not to be an attempt to ‘break through.’ The assailants were not to be drawn into pockets from which they would be fired upon from all sides. They were to fire at the French and assault them continually in positions which French pride would make it impossible to yield. The nineteen German divisions and the massed artillery assigned to the task were to wear out and ‘bleed white’ the French Army. Verdun was to become the anvil upon which French military manhood was to be hammered to death by German cannon. The French were to be fastened to fixed positions by sentiment, and battered to pieces by artillery.2

French pride, however, did not preclude them from strenuously asking the Russians for help as more and more of their own divisions were committed to the slaughterhouse of Verdun. The French were desperate for the Russians to launch offensives that would force the Germans to reinforce their eastern front from forces fighting it out in the great battle in the west. The Russians promised to help, but they had memories of the last time they had made such vows – at the opening of the war they had charged into Prussia with two field armies, only to have one utterly destroyed and the other gutted.

Russian High Command of the Army, Mogilev, 25 February 1916

Defence Minister Stolypin shivered despite the warmth of the fireplace in his study. The import of the French demands for help was not lost on him. The war was consuming Russia. The previous year had been one of disaster. The Russian Army had been driven out of Poland and suffered two million losses – 1916 promised to be even worse.

His wound suffered five years ago in the assassination attempt ached all the more in the cold weather. It had taken him years to recover, and it was only last month that the tsar had asked him to take up the burdens of defence minister.3 It was an easy decision for Nicholas to make. After all, the tsar bore an enormous sense of guilt for the attempt on Stolypin’s life, having put him in harm’s way by requesting his presence at the opera. The tsar had every reason to feel remorse. Stolypin had been the finest of his ministers. His agricultural reforms to break up the peasant collectives into individual farmsteads had begun to establish an independent peasantry to be a bulwark of the throne. Now more than ever that throne needed support.

Nicholas’s incompetence as a war leader, after he had assumed command of the armed forces, had done much to discredit the monarchy. His only talent seemed to be the ability to make the wrong decision. It was a feast for a host of revolutionaries whom Stolypin had so effectively curbed, before his wounding, by ruthlessly employing what a Duma member had termed, ‘Stolypin’s efficient black Monday necktie’ – the gallows. Stolypin had reason to hate them: a bomb had killed his fifteen-year-old daughter and wounded his three-year-old son. One of the revolutionary leaders, Vladimir Lenin, from his exile in Switzerland, had said it was Stolypin’s agricultural policy that was the greatest threat they faced in seizing power. The imbecilic decision at the beginning of the war to abolish the military police corps had allowed the revolutionaries a priceless opportunity to sow sedition, repeatedly fertilised by endless reverses.

What had cleared the way for the tsar’s decision, besides the universal recommendation of his ministers and the Russian Orthodox Church, was the murder of his chief enemy, the depraved but hypnotic monk Gregori Rasputin. Stolypin had warned the tsar about Rasputin’s antics, but Nicholas had ignored it because of the tsarina. Alexandria believed Stolypin was evil for his opposition to Rasputin, and to her that threatened the life of her only boy, her beloved Aleksei, the heir, fatally afflicted with haemophilia. Only Rasputin had been able, through what she believed was his spiritual power, to bring him back from death’s door as his body began to bleed uncontrollably. That opposition had been swept away by Prince Prince Felix Yussupov and Duma member Vladimir Purishkevich when they lured Rasputin to the former’s palace, and with great effort, murdered him in December 1915. Luckily, the tsarevich had not had an attack since the monk’s death. Stolypin lit a new candle in church every day to pray that the tsarevich remained in good health and that his mother continued to dote on her son rather than direct her venom at him. He also kept his fingers crossed. He knew that sooner or later the boy’s affliction would kill him, and he did not need the imperial family consumed in grief or the political shock waves that would come from the death of the heir. That would leave Grand Duchess Olga next in line of succession. It occurred to him that Russia had not done too badly when a woman had sat on the throne.

As to his ability to save that throne and Russia, Stolypin thought it was probably too late. War production had not been able to properly equip and sustain the army. There had not been enough rifles for the hundreds of thousands of men being called up to replace the staggering losses, not enough ammunition of all kinds. The only serious victories had been against the Austro-Hungarians whose empire, a patchwork of fractious nationalities, had proved especially brittle. Had it been only a war between Austria and Russia, the tsar’s armies would by now have occupied Vienna. But it was the Germans who were the serious enemy – efficient, professional, well-supplied, and brilliantly led at every level. The German Army proved remarkably resilient and its combat effectiveness had actually improved as the war had continued. It was their remorseless and deadly offensives that inflicted the worst damage on the Russians. Furthermore, German reinforcements and their increasing operational control of the Austro-Hungarians had saved them from being mortally savaged by the Russian bear. The Germans had soon learned to treat their Austro-Hungarians with a well-deserved contempt. Early in the war the German representative on the Austro-Hungarian General Staff had wired Berlin presciently, ‘that we are shackled to a corpse’.

That appraisal was cold comfort to the Russians now. Stolypin, in his recuperation, had stayed abreast of events and personalities that the war had raised up. His first requirement was for capable men. That was why his cousin’s husband, General Aleksei Brusilov, was sitting beside him in front of the fireplace. He had not seen him for years, but the man did not seem to have changed. Despite his sixty-three years, he remained slim and energetic at an age when Russian generals so often turned to fat. There was a sharp intelligence in his blue eyes which made you realise why he was considered the finest of Russia’s generals, the man who had repeatedly beaten the Austro-Hungarians. It was not by brute force but by his high leadership skills, his thoroughness, and above all by his ability to innovate and adapt. The men of his 8th Army had been better trained and cared for than in any other command, and they had given him victories.

‘Aleksei Alekseyevich, Forgive me for not rising to greet you,’ Stolypin said. He had never fully recovered from that bullet wound, ‘but …’

‘No need, Pyotr Arkadyevich. Soldiers understand. Your injuries were suffered in service to Russia as much as any soldier’s on the battlefield.’ They had both used the familiar first name and patronymic that bespoke a deep friendship. They exchanged pleasantries as a servant brought in steaming glasses of tea, which only Russians seem to be able to hold without burning themselves.

When the doors shut, Stolypin turned to the matter at hand. ‘I must speak candidly. Tell me, have we lost the war?’

‘Yes, we have.’ He paused, then added, ‘If things are allowed to go on without any serious changes in the command of the armies.’

Russia needed a giant like Peter the Great or even Nicholas’s father, Alexander III, a real autocrat with the ability to carry it off. Instead, they had ‘Nicky’, as his German and English cousins called him, a man who had been born on the name day of ‘Job the Sufferer’, which had not been lost on a pious Russia. Peter and Alexander must be rolling in their graves. Before he had been shot, an incredulous Stolypin had written in his diary of the tsar’s words to him. ‘I have a premonition. I have the certainty that I am destined for terrible trials, but I will not receive a reward for them in this world … Perhaps there must be a victim in expiation in order to save Russia. I will be this victim. May God’s will be done!’4

Stolypin’s immediate problem was guiding the tsar, who seemed to be even more the resigned and passive martyr; since he had declared himself commander-in-chief of the armed forces, he had not thought to actually take command. With Rasputin out of the way, Stolypin was able more and more to influence Nicholas, who seemed be almost relieved to leave decisions on the war to such a strong, capable personality.

Brusilov was too tactful to criticise the tsar to his defence minister, family or not, but he took aim right below him, at the Chief of Staff of the Russian Army, General Mikhail V. Alekseyev. He said, ‘Alekseyev is not up to the job. He is conscientious but gets lost in the details and has no strategic vision. Nor can he enforce his will on the front commanders who run to the tsar and bring up their social connections every time he tries to force them to exercise common sense and good judgement.’ Stolypin agreed with Brusilov’s description of the Stavka (army high command) and Alekseyev.

‘And the front commanders?’ Stolypin asked.

‘Evert is stubborn, cautious, and does not cooperate, even on Alekseyev’s orders. Kuropatkin is indecisive and incapable of organising his forces. His performance is no different than in the war with the Japanese twelve years ago. What did Voltaire say? Learned nothing and forgotten nothing.’ Stolypin nodded at the assessments of the commanders of the North-West and Northern Fronts, Generals Aleksei Evert and Aleksei N. Kuropatkin.

‘And your own front commander?’ he asked..

Brusilov did not hesitate. ‘[Nikoalis L.] Ivanov is just worn out and used up. He has no more to give. The demands of modern war are beyond him. He has become an old ninny.’

‘Whom would you recommend to replace them?’

Headquarters, Ober-Ost, 10 March 1916

Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg was not happy with Falkenhayn’s obsession with Verdun. Already, the plan to wear the French down was a double-edged sword. German soldiers in that maelstrom were starting to call him the ‘blood miller of Verdun’. Hindenburg, the Ober-Ost, commander of the four German armies fighting the Russians, thought German resources would be better used in a major offensive in the east to knock the Russians out of the war. Already he had them on the ropes. He chafed that he did not control the German troops sent to reinforce the relentlessly incompetent Austro-Hungarian armies south of the Pripet Marshes. This vast natural barrier formed the boundary between the German and Austro-Hungarian armies.

Falkenhayn and Hindenburg did agree that the Austro-Hungarian obsession with their new offensive against the Italians was draining strength from their armies facing the Russians. The Austro-Hungarian Chief of Staff, Franz Conrad von Hötzendorf was, to say the least, not well thought of by his German allies. Conrad’s missteps would have earned him a brutal dismissal in any other army, yet the fecklessness of Austro-Hungarian politics kept him in place. Now his determination to punish the Italians for joining the Allies against their former dual-monarchy allies was making him oblivious to the Russians. By February Conrad planned to transfer three of his divisions from the Russian front and asked for German troops to backstop them. Falkenhayn and Hindenburg turned him down flat. Falkenhayn had already transferred eight German divisions from the east to Verdun. Not only would there be no German support, but if there was a Russian build-up opposite Hindenburg’s armies in the north, German troops supporting the Austro-Hungarians would be recalled.

Conrad was unfazed. He withdrew four division in March for the offensive planned to begin in May. He further weakened these armies by withdrawing numerous individual battalions, often the most experienced, as well as fifteen batteries, almost all the heavy artillery in the four armies facing the Russians. For example, on 14 February, the 3rd Infantry Division, made up of ethnic Austro-Hungarian Germans with a good combat record, transferred to the Tirol. It was replaced by the 70th Honved (Hungarian Reserve) Division, which had absolutely no combat experience. Conrad reasoned that the preponderance of Russian forces faced the Germans while only 600,000 Russians faced 570,000 Austro-Hungarians along their 450-kilometre front. Against the Germans they had a definite numerical superiority. That is where the Russians were expected to attack. He wrote in late March that under conditions of parity on his own front, ‘a Russian attack would have to be considered pointless.’5

The incapacity of the Russians had just been proved by their disastrous performance at the Battle of Lake Naroch on 18 March. In response to the French pleas for offensive action to take some pressure off their forces at Verdun, the Russians had attacked the Germans in the southern approaches to the Baltic with 350,000 men of the Russian 2nd Army against the 75,000 men of the German 10th Army – twenty divisions against four and half. For once there were enough artillery shells to feed the almost one thousand guns. It was a disaster. The Russians staggered off after having lost a hundred thousand men to the fewer than twenty thousand German casualties. No account had been taken of the spring thaws that made the ground a morass that sucked up artillery shells. There was no artillery reconnaissance, and most of the huge shell expenditure was wasted. Senior leadership had been wretched. Alekseyev wrote of one general commanding a group of corps, ‘It seems unlikely that he will be able to manage the bold and connected offensive action or the systemic execution of a plan that are needed. Still, he could not relieve him because of his social connections as it was alleged, “some old granny still has fluttering about the heart when his name comes up.”’6 Lake Naroch was the death knell of the old Russian Army. It remained to be seen if a phoenix would rise out of the ashes.

Russian High Command of the Army (Stavka), Mogilev, 14 April 1916

Stolypin’s increasing control of the tsar and the war effort was like a fresh wind blowing through the army. The war itself had already done its own winnowing. Men who knew how to get things done were increasingly filling critical positions. One of them was General Anton Ivanovich Denikin. Brusilov had praised him to the heavens as just the sort of outstanding combat leader the army needed. Under Brusilov, he had commanded first the famed Iron Brigade and then the 48th Division with an intelligent aggressiveness that made it famous and lethal. He was quickly advanced to command the VIII Corps in Brusilov’s 8th Army.

Another officer was twenty-three-year-old Captain Mikhail Nikolayevich Tukhachevsky, an officer of the Semyenovsky Guards Regiment,7 who had said as the war began, ‘I am convinced that all that is needed in order to achieve what I want is bravery and self-confidence. I certainly have enough self-confidence … I told myself that I shall either be a general at thirty, or that I shall not be alive by then.’ In the space of the first six months of the war he was decorated five times for valour. Unfortunately, he had been captured early in 1915 and sent to the German POW camp at Ingolstadt for being an incorrigible escapee. He succeeded on his second attempt to cross the German–Swiss border and returned via the United States and the Trans-Siberian Railway, just in time to be assigned to Brusilov’s staff. He quickly showed that he was brilliant. Brusilov paired him with Denikin as his deputy operations officer. The two hit it off famously and made a great team, with the young man fully taking over the job as operations officer. It quickly became clear that the young Tukhachevsky had a ruthless streak. He did not suffer fools. Neither did Denikin. They would have their hands full.8

Stolypin astounded the Russian Army by sacking Evert and replacing him with General Vasily Iosifovich Gurko, fifty-four, to command the West Front’s three armies. The former commander of the 2nd Army and the man who had reorganised the Guards Corps after its heavy losses, Gurko had been a major advocate of military reform before the war. In a private interview Stolypin told the astounded Gurko that it was Brusilov who had enthusiastically recommended him. Stolypin explained, ‘I have promoted you because we need to sweep away the habit of defeat. You know, of course, that you have made an enemy of every general you have jumped over. Most of them need to be jumped over. I give you the authority in the tsar’s name to remove any officer you think not up to the job and to promote any you think have talent.’ Stolypin was accelerating the already growing rise of capable men in the Russian Army. The anvil of war had hammered away many a phony reputation, but there were unfortunately many left.

Kuropatkin was dismissed at the same time. His replacement to command the North-West Front was the fifty-four-year-old General Nikolai Nikolayevich Yudenich who had repeatedly beaten the Turks on the Caucasus Front. His latest success was to capture the city and fortress of Ezerum in eastern Anatolia in January just in time to take the bloom off the Turkish victory at Gallipoli. Stolypin decided to keep Alekseyev who now received rational and firm direction through the tsar from Stolypin, who was closely advised by Brusilov. With Brusilov, Denikin, and Yudenich now commanding the three Russian fronts, Alekseyev would find his team easy in the traces. He also reasoned that it was one change too many for Nicholas to lose someone who was such a committed defender of the monarchy, something Stolypin was in full accord with.

The power arrangement was clear when Stolypin sat in on the first meeting of Alekseyev and his three new front commanders, an unprecedented intrusion into military affairs by a civilian minister. No one complained. He simply listened. The British and French were asking for a strong Russian offensive to take the pressure off them in France, and the meeting was ostensibly about how to address that. Alekseyev began by recommending that another attack by the West and North-West Fronts against the Germans would be the most effective. ‘We are capable of a decisive attack only on the front north of the Pripet.’ He went on to explain that when the new conscript classes arrived, they would have a superiority of 745,000 men north of the Pripet and only 132,000 south of it in Brusilov’s South-West Front.9 Enough rifles, artillery, and ammunition of all sorts was now starting to be received from Russian industry as well as Allied shipments to the Arctic ports and along the Trans-Siberian Railway from Vladivostock. For the first time, there would be adequate ammunition and enough rifles. Men would not have to be told to pick up the weapons of the fallen.

Brusilov spoke: ‘Gentlemen, the unfortunate strategic truth is that we are simply not going to beat the Germans in the field, this year at least, by directly attacking them.’

Gurko stood up, visibly angry, ‘Are you saying the war is hopeless? I refuse to accept that we cannot defeat them.’

‘I did not say we could not defeat them, general. I said we could not beat them in the field. There is a difference. The Germans have an Achilles heel, gentlemen, but it is not anywhere along their front. The vulnerability is their alliance with Austria. If it had been a war just between Russia and Austria, the tsar would have been dictating terms in Vienna last year. The only thing that holds the Austro-Hungarian front together is the stiffening of a few German divisions and the ability of the Germans to reinforce them. The Austro-Hungarian Army is a shell. If it collapses, Vienna must sue for peace and drop out of the war. The Germans simply do not have the forces to cover the entire war in the east. To defeat the Germans, we must attack them indirectly.’

He also pointed out that, unlike the German Army which was ethnically homogeneous, the Austro-Hungarian armies were patchworks of nationalities, most of whom could not speak German, the command language of the army. In ‘1906, out of every 1,000 enlisted men, there were 267 Germans, 223 Hungarians, 135 Czechs, 85 Poles, 81 Ruthenians (or Ukrainians), 67 Croats and Serbs, 64 Romanians, 38 Slovaks, 26 Slovenes, and 14 Italians.’ Almost half of that thousand (422) were ethnic Slavs of one kind or another, many of whom would be inclined to identify with their fellow Slavs, the Russians. The ruling Germans and Hungarians numbered 490, not even half of the force. The remainder were the Italian and Romanian Latins whose homelands were outside the empire, and in the case of Italy, were at war with the Hapsburgs.10

‘This is what I propose. You – Gurko and Yudenich – will pitch into the Germans and hold them tight so that they dare not send any reinforcements to the Austro-Hungarians. I will attack the Austro-Hungarians with my front. The Austro-Hungarians will shatter, we will pursue them through the passes in the Carpathian Mountains and into the plains of Hungary. We have fifty cavalry divisions we can unleash into that perfect country for horsemen. No matter what the Germans do they will not be able to establish a line.’

Everyone was silent as they drank in the ramifications of what Brusilov had just outlined. Alekseyev spoke first. ‘Unfortunately, we learned from Lake Naroch that even plentiful artillery ammunition was not enough to break the German lines.’

‘General, there is nothing like incompetent execution to ruin a good idea. We will deal with the incompetence and waste no more Russian lives because of it. The Germans are due for a surprise.’

South-West Front, April–May 1916

Brusilov’s innovations at the South-West Front became a school for the rest of the army. Staffs and commanders from the other two fronts rotated frequently through to observe and take note and to implement those models on their return to their own commands. Brusilov was keenly aware that the Germans had good intelligence of what was going on behind the Russian lines. The movement of large forces spotted by German reconnaissance aircraft was always a key indicator of Russian intentions. For that reason, Brusilov asked only for a few reinforcements but those were in specialised units such as engineers, signals, some heavy artillery, and aeroplanes. The latter’s chief role was in reconnaissance of the Austro-Hungarian Army positions opposing the South-West Front.

It became clear that the Austro-Hungarians ‘were concentrating on construction rather than on any active defence against the Russians. Recruits sent to the Russian Front as replacements for the veteran troops diverted to the Tirol were put to work extending and strengthening the positions established … in September 1915.’ The emphasis was on strength of the forward positions with very little depth. This was done at the expense of combat training and active defence. What training they did receive consisted of rifle drill, parades, and snow shovelling. There was no live fire or close-combat training. ‘This had the dual effect of tiring the troops and establishing non-military activity as the “norm” of the front lines.’ Those forward defences were intended to consist of three groups of three lines each, but as late as the beginning of June the Austro-Hungarians had only completed the first element along most of their front. Aerial reconnaissance kept Brusilov fully informed of the extent and layout of these defences.11

The Austro-Hungarian forces had been reinforced with about thirteen thousand German troops, interspersed among several of the Hapsburg armies. The northernmost was Army Group Linsingen commanded by the highly capable German colonel, General Alexander von Linsingen. The German element was Group Gronau (German XLI Reserve Corps) of Guards Cavalry, 5th Cavalry and 65th and 81st infantry divisions. This force blocked the southern part of the Pripet Marshes, and were not directly opposed to the Russian South-West Front. They faced the West Front’s 3rd Army. The Austro-Hungarian 4th Army was nominally under the command of Linsingen, but the fact that its commander, Archduke Josef Ferdinand, was the godson of Emperor Franz Joseph allowed him to escape the usual German domineering attitude when commanding Austro-Hungarian forces.

The following table shows the Hapsburg forces, with attached German divisions, from north to south. They numbered eight cavalry and 37 infantry divisions of which two were German. All units are Austro-Hungarian unless identified as German.12

Austro-Hungarian Order of Battle Opposing the Russian South-West Front

4 June 1916

4th Army, HQ Lutsk, Commander: Archduke Josef Ferdinand

Cavalry Corps

Polish Legion (9th KD, 11th HID)

Corps Fath (26th and 53rd ID)

Corps Szurmay (7th and 70th ID)

X Corps (2nd ID, 37th HID)

II Corps (4th ID, 41st HID)

The following 1st and 2nd Armies formed Army Group Böhm-Ermoli.

1st Army, HQ Ziechov, Commander General Paul Puhallo von Brlog

XVIII Corps (7th KD, 25th and 46th ID)

Group Marwitz (7th and 48th German ID, 22nd and 107th ID)

2nd Army, HQ Brody, Commander General Eduard Freiherr Böhm-Ermoli

Group Kosak (4th, 17th, 29th ID)

V Corps (31st ID)

IV Corps (14th and 33rd ID)

Südarmee, HQ Brzesany, Commander General Count Felix von Bothmer

IX Corps (19th and 32nd ID)

Corps Hofman (54th and 55th ID)

48th German Reserve ID

7th Army, HQ Kolmea, Commander General Karl von Pflanzer-Baltin

VI Corps (12th and 39th ID)

XIII Corps (2nd KD, 15th and 36th ID)

Group Hadfy (6th KD and 21st ID)

Group Benigni (3rd, 5th and 8th KD, 30th, 42nd and 51st ID)

XI Corps (5th, 24th and 40th ID)

Brusilov was keen to bring any useful innovation to the attack and drew creatively from the experiences of the Russo-Japanese War and the lessons learned by the French on the Western Front. He was eager to accept the French instructors who taught the concept of the ‘Joffre Attack’ developed in Champagne the previous year. ‘There the French had forsaken the doctrine of concentration of forces in favour of preparation, creating holding areas for the reserves close to the German lines to reduce the time between the artillery bombardment and the infantry assault.’ The bombardment was short but intense, what the Germans called ‘drumming fire’. Brusilov had already adopted these tactics in his 8th Army a month before he was promoted to command the front.

Brusilov’s emphasis was on thorough preparation since he knew that few reserves were available. To some degree large numbers of reinforcements would be a liability since their movement to the front would reveal to the Germans that a large offensive was coming. Therefore, Brusilov ordered that the reserves of each army be brought into the forward lines and put to work digging the place d’armée, trenches 300 by 90 metres, from which the Russians would mount their assault. Since this was happening all along the front, the Austro-Hungarians had no indication where the main blow would fall. The next step was to dig forward trenches towards the enemy lines from which the attack would be made. Brusilov wanted them no more than a hundred metres from the enemy lines and preferably only sixty, or even less.

At the same time the Russians were conducting a thorough reconnaissance of the Austro-Hungarian positions. Of particular importance was aerial photography which put special emphasis on the location of Austro-Hungarian artillery. The resulting diagrams were more accurate than the enemy’s maps of their own positions. Brusilov ensured this information was shared with his own gunners. Based on this intelligence each army commander in consultation with Brusilov selected the main breakthrough point on his front. Once this was done, models of the Austro-Hungarian positions were built, and the hand-picked assault troops, called Shturmavye Otriady, practised taking them over and over again.

Attack groups were to be no larger than five divisions, with the attack broken into four waves. The first wave equipped with hand grenades, was to push into the enemy’s front trench and take out any flanking guns the artillery had missed. The second wave would follow 200 paces behind and then attack the second line of trenches directly. Once the breach was secured, the third wave would bring the Russian machine guns forward and set about expanding the gap along the line. The fourth wave was to secure the flanks of the gap, allowing the Russian cavalry to pour through and into the enemy rear.

Brusilov fully integrated his artillery into these techniques. Commanders carefully selected their own targets, and Brusilov brought in experienced French and Japanese officers to train them properly for these new missions. The drumming fire would last only ten to twelve minutes. First the light artillery would blow open 4–5-metre gaps in the wire and then shift to knock out enemy machine guns. Then they would shift again to concentrate on the Austro-Hungarian infantry in the forward trenches and the heavy artillery within range. At the same time the Russian heavy guns would be destroying the enemy’s communication trenches before shifting to join the light artillery in hitting the Austro-Hungarian infantry.

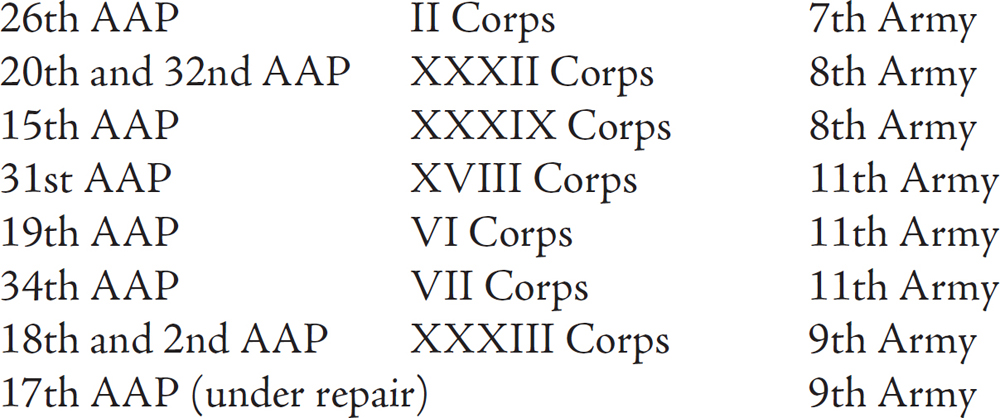

Brusilov had another resource that the Austro-Hungarians did not have – autopolemetaye (armoured-car) platoons (AAP), that he specifically ordered held back for the exploitation phase of the offensive. Each platoon was equipped with three armoured cars.

Armoured-Car Platoons, South-West Front

4 June 191613

Reinforcing these Russian armoured-car platoon were Belgian and British armoured-car units. The Belgian Expeditionary Force in Russia (Corps Expéditionnaire des Autos-Canons-Mitrailleuses Belges en Russie) had been very effective in the Flanders battles of 1914, but the static front that followed gave them nothing to do until Nicholas asked King Albert of the Belgians for their loan. The corps, 333 men and thirteen armoured cars strong, arrived in Russia in October 1915, fought well in Galicia on the South-West Front in February 1916, and were mentioned five times in dispatches. The British Armoured Car Expeditionary Force (ACEF) of twenty-eight armoured cars and 566 men arrived in Russia in January 1916 and was specifically requested by Brusilov for use in his offensive. They arrived just in time for the offensive. In all Brusilov would be able to deploy seventy-one armoured cars and their highly trained crews.14

Despite the Belgian and British contingents, the South-West Front was a true reflection of the Russian Empire. Four of its cavalry divisions and two of the brigades were made of Cossacks from the Orenburg, Don, and Terek Cossacks. There were four Finnish infantry divisions, a division from Turkestan, and four of Siberians from the Transamur region. In all, the front numbered ten cavalry and forty infantry divisions, only five more than the Austro-Hungarians facing them, despite a Russian advantage of 132,000 men.15 This was due mostly to the wave of new conscripts that he had integrated and intensively trained into his existing divisions.

Brusilov chose his old command, the 8th Army, to carry the main thrust of the attack. If there was to be a weak link, it was the leadership of the 8th Army’s commander, General Aleksei M. Kaledin. Brusilov had to make frequent visits to his headquarters to keep him from having a nervous breakdown. With Stolypin’s backing he relieved Kaledin and put Denikin in his place. The 8th Army was the elite formation of the South-West Front. Brusilov had trained it hard and led it well. Many of its officers were men of talent whose promotion and placement had been due to their success in battle rather than the cronyism that dogged other Russian units. Brusilov knew his old army would be up to the task now that it was in the hands of a first-class soldier. Since 8th Army would carry the primary assault of the front, this was not a minor consideration.

Berdichev, South-West Front Headquarters, 1 June 1916

In his mind’s eye Brusilov could picture what was happening to the north. The half light of dusk had barely fallen when two thousand Russian guns on the West Front opened up on the German trenches. At exactly the same time, another fifteen hundred guns on the North-West Front lit up the gathering darkness. Gurko and Yudenich’s troops had been well trained in the Brusilov method. By the next morning they had made serious penetrations into the enemy trench networks. The Germans were indeed surprised. The accuracy and volume of Russian artillery was unprecedented. Right behind came the Shturmavye Otriady. These were not the conscript masses, so often fodder for the German machine guns. They were well-trained deadly small groups advancing behind a hail of grenades and the spurting glare of flamethrowers. Ober-Ost was shocked when a German division simply disintegrated, losing four thousand of its men as prisoners. By the second night, Hindenburg was authorising the commitment of theatre reserves. His famous equanimity was not disturbed, but his volatile Chief of Staff, Erich Ludendorff, was calling this attack the crisis of the war in the east. With Hindenburg’s permission he notified Falkenhayn that reinforcements might be necessary. Brusilov counted on just that reaction. The attention of the Germans was now firmly fixed on their own front as their reserves were sucked into the fighting.

Order of Battle of the Russian South-West Front

4 June 1916

Front Reserve (Placed under 8th Army for the offensive)

12th KD

4th Finnish ID

Heavy Artillery Division

8th Army, HQ: Rovno, Commander: General Anton I. Denikin

V Cavalry Corps (Orenberg Cossack KD and 11th KD

XX Corps (71st, 80th and 100th ID)

XXXIX Corps (102nd and 125th ID)

XL Corps (2nd and 4th Rifle Divs)

VIII Corps (14 and 15th ID)

XXXII Corps (101st and 105th ID)

7th KD

11th Army, HQ: Volochisk, Commander: General Vladimir V. Sakharov

XVII Corps (3rd and 35th ID)

VII Corps (10th and 34th ID)

VI Corps (4th and 16th ID)

XVIII Corps (23rd and 37th ID)

Transamur KD

7th Army, HQ Guzyatin, Commander: General Dmitrii G. Scherbatschev

XXII Corps (1st and 3rd Finland ID)

XVI Corps (41st and 47th ID)

II Corps (26th and 43rd ID

3rd Turkestan ID

II Cavalry Corps (Composite Cossack KD, 2nd Don Cossack Cavalry

Brigade, Composite Cossack Cavalry Brigade, 9th KD)

V Caucasian Corps

1st Ind Cavalry Brigade

2nd Finland ID

9th Army, HQ: Kaments-Podolsk, Commander: General Platon A. Letschitski

XXIII Corps (1st and 2nd Transamur ID)

XLI Corps (3rd and 74th Transamur ID)

XI Corps (11th and 32nd ID)

II Corps (12th and 19th ID)

Composite Corps (82nd and 103rd ID)

III Cavalry Corps (1st Don Cossack KD, Terek Cossack KD, 10th KD)

Meanwhile, the relative lull that had settled on the Austro-Hungarian front was about to be shattered. There the senior officers of the dual monarchy were relishing – with no little Schadenfreude – the distress of the Germans. It had not been lost on them for some time that an offensive was building up against them. Brusilov was glad that they had not missed the obvious. He simply overwhelmed them with his efforts at deception, what the Russians called maskirovka. Since all the Russian armies were making identical preparations along the entire front, the Austro-Hungarians could not pinpoint where the main attacks would be. To add to their confusion, Brusilov cluttered their analysis with false signals, documents, and deserters primed with misleading information. They could gain no coherent picture of the Russian plans, but they comforted themselves by believing the Russians would fight in the same old way and could be easily repulsed in the same old way. They had fallen into the trap laid by all great strategic surprises. Their complacency caused them to ‘make the wish father to the thought’.

The next day Brusilov’s air reconnaissance began to report the movement to the rear of the two German divisions attached to the Austro-Hungarian 1st Army and Südarmee. In addition several of the German divisions in Group Gronau covering the Pripet Marshes at the boundary of West and South-West fronts were observed to be moving to the rear. The offensive to the north had done its job, and the Austro-Hungarians were now left without the shield of German protection.

HQ, South-West Front, Berdichev, 4 June 1916

At one in the morning Brusilov gave the order for the offensive to begin in three hours. He announced, ‘It is time to drive out this dishonourable enemy.’ At four the Russian artillery commenced firing along the front and for three hours hammered the enemy. At seven the Russian guns paused to check the damage done. In that time, the Austro-Hungarians rushed their reserves to the forward trenches and unleashed their own artillery into an empty no man’s land where they thought the attacking Russian masses would be swarming. They were relieved that their own losses had been minimal, reinforcing their belief that the coming Russian attack could be easily fended off. By now, they had correctly concluded that the Russian 8th Army would lead the primary attack. Brusilov had stacked 8th Army with half of his front’s guns, the foreign armoured-car units, and enough forces to give Denikin at least a fifty-thousand-man advantage over the Austro-Hungarian 4th Army commanded by Archduke Ferdinand. Brusilov, like Alexander the Great, was lucky in his enemies. If the Macedonian had Darius, Brusilov had Ferdinand. The archduke, although a career soldier, was so manifestly incompetent that he remained preoccupied with the sixtieth birthday party he was hosting for Conrad even as the artillery duel of a major battle was underway. The fact that 8th Army’s infantry did not follow up its barrage drew the eyes of the Austro-Hungarian commanders further south.

There the Russian Army’s artillery preparation had made a shambles of the trenches of the Austro-Hungarian 2nd Army. An Austro-Hungarian observed that ‘there was drum-fire of hitherto unequalled intensity and length which in a few hours shattered and levelled our carefully-constructed trenches … Apart from the bombardment’s destruction of wire obstacles, the entire zone of battle was covered by a huge, thick cloud of explosive-gases, which prevented men from seeing, made breathing difficult, and allowed the Russians to come over in thick waves into our trenches.’ The Austro-Hungarian artillery was either silenced or expended its ammunition in initially firing into the empty no man’s land.16 The pauses in the Russian fire unnerved the troops, who kept to their bunkers. The sudden appearance of thirteen Russian armoured cars of 11th Army deep in their position along the Tarnopol–Lemberg railway sowed confusion and panic. Behind them, the Russian assault troops had breached the enemy’s second line. To the north Russian attacks wiped out the Austro-Hungarian 1st Army’s bridgehead over the Ikvanie River. But it was in the south, on the fronts of the Südarmee and 7th Army, where the Austro-Hungarians felt most secure, that disaster fell upon them.

The disaster was least expected because 7th Army was made up largely of Hungarians and loyal Croats. The army commander, however, had put the untested 79th Honved Infantry Brigade in the front line, not realising that he was cramming the Hungarians into positions meant for only half their numbers. One of those pauses in the Russian fire caused them to boil out of the confining shelters, only to be caught rushing out into their trenches by a resumption of the enemy guns. The slaughter was so great that the survivors were stunned. The next morning the Russian assault troops of 9th Army hit them. The Hungarian brigade disintegrated, losing 4,600 of 5,200 men. The rest of the day was spent driving the Austro-Hungarians back from one position until by nightfall the Russians were through to open country, having taken thousands of prisoners.

Forward Trenches, Russian 8th Army, Dusk, 5 June 1916

Senior Lieutenant Vladimir Golitsyn looked back in the gloom and could barely make out the faces of the first few men in his assault group. Despite the aristocratic name, he had been a clerk in Tula when he had enlisted in 1914. The old Russian Army had made him a sergeant. The new Russian Army had recognised his leadership abilities and made him an officer. He knew his job, and he took care of his men. Now they were all waiting for the moment they had repeatedly rehearsed.17

There it was – the thunder of the guns! The earth shook because the shells were falling only sixty yards ahead of them into the Austro-Hungarian trenches. The Russian guns were tearing gaps in the wire directly in front of them. In all the guns cleared fifty-one gaps in 8th Army’s front. In twelve minutes the guns fell silent, and Golitsyn bolted forward out of the trench, not even looking back to see if the men followed. They were right behind and dashed through the gap in the wire and into the first enemy trench and its smashed machine guns. They had been so close to the enemy trenches, just as Brusilov wanted, that they were into them before the Austro-Hungarian troops began to emerge from their bunkers to man their positions.

Golitsyn and his men were running down an empty trench when a man in Austro-Hungarian field grey appeared out of the entrance to a bunker. Golitsyn shot him with his revolver, and the men behind him threw in half a dozen grenades. Screams. Then smoke, and the choking words in Italian and German, ‘We surrender, comrades.’ Over fifty men stumbled out with their hands up, but Golitsyn and most of his men were already gone, blasting out more bunkers and taking more prisoners. Behind the Shturmavye Otriady came the next waves, tasked with gathering up the prisoners and following up the success by overrunning the next trench line. By the time the Russian follow-on infantry arrived, the trenches were full of dead and wounded; the survivors simply surrendered. Such was the fate of the 70th Honved Infantry Division, the poorly trained Hungarian reservists. Almost 7,000 out of a strength of 12,200 surrendered without a shot.

With the collapse of the Hungarians, the Shturmavye Otriady were able to penetrate quickly into the third enemy line and turn against the flanks of adjoining divisions of the Austro-Hungarian X Corps. By nightfall that corps had lost 80 per cent of its men, and the third and last position had fallen. Austro-Hungarian troops, especially the non-Germans, had begun surrendering everywhere. In the first two positions 85 per cent of Austro-Hungarian casualties had been caused by the artillery and rifles. In the third line the garrison surrendered en masse.18

By the next morning Denikin was driving the enemy back across open ground. He was right behind the advance elements, a place rarely seen by general officers in this war. At this point, he unleashed his Belgian, British, and Russian armoured-car units and his cavalry divisions. The armoured cars raced ahead, machine-gunning the masses of fleeing Austro-Hungarians, further disintegrating what little cohesion they had left. As the survivors scattered, the Cossacks rode in amongst them, sabring and lancing. That same day the Russians closed on the railway hub of Lutsk and captured it with another five thousand prisoners to add to the fifty thousand men and seventy-seven guns they had already taken. One Austro-Hungarian corps commander wailed, ‘the whole of IV Army has really been taken prisoner … It’s a complete debacle, we can do nothing with the troops.’ By the end of the day, 4th Army, reduced to fewer than 27,000 men from its original strength of 100,000, no longer existed as a serious military force. Truly, as Homer wrote, panic was brother to blood-stained rout. One captured Austro-Hungarian staff officer said, ‘They moved so fast that every attempt to reform was shattered by the armored cars. The Russians had brought lightning to the battlefield, they were so swift.’19

The Russian cavalry divisions of 8th Army rode deep into the Austro-Hungarian rear, reaping the fruits of victory in the pursuit – prisoners, ammo and food dumps, wagon trains and truck convoys. By the evening of the 7th they were forty-five kilometres west of Lutsk, snapping up what was left of the Austro-Hungarian line of communications. The armoured cars that had not broken down kept pace by refuelling from captured petrol stocks. Of even greater importance was all the captured railway stock. It was immediately put to use by Russian railway troops, easing the problem of supplying their advancing infantry. That in turn was made even easier by the vast amounts of food stocks and artillery ammunition captured by the Russians. So much Austro-Hungarian artillery ammunition was captured that the Russian factories that had been devoted to producing shells for captured guns received emergency orders to shift back to making Russian shells.20

Ober-Ost, 9 June 1916

All the news stank of disaster. Ludendorff was so anxious that it took all of Hindenburg’s granite calm to keep him from becoming hysterical. Their armies were locked in a death struggle with the Russian West and North-West Fronts. They had never seen the Russians fight so effectively. German intelligence had reported the appointment of two new generals to command the two fronts, but both Hindenburg and Ludendorff underestimated them. Gurko was new to front command, and Yudenich had only fought against the Turks. There was no doubt that the Germans could eventually contain the Russian attacks, but there was not a man in reserve to spare. That was why their real concern was for the collapsing Austro-Hungarian armies. Each new message only added to the scale of the disaster. Instead of being able to send reserves and senior commanders to brace up the Austro-Hungarians, Ober-Ost had to request, in the strongest terms, reinforcements from the Western Front. So serious was the unfolding situation that Falkenhayn actually broke off the Verdun offensive to send troops east.

Until then there was only one German division available anywhere to help stem the Russian advance: the 48th Reserve Division that had been withdrawn from Südarmee before the Russian offensive. It was now turned around at Kovel in order to help defend that vital communications centre. Linsingen’s Group Gronau had been fixed in place by attacks of West Front’s 3rd Army and could not support the 48th. The last message Ober-Ost received stated that the division had been surrounded with scattered remnants of 4th Army there. That meant the Russians had advanced a hundred kilometres since the offensive began. The major communications centre and fortress of Brest-Litovsk was only another 160 kilometres from Koval. Group Gronau was now threatened by the Russians from the south as well as the east and began to disengage to prevent encirclement. That day the Germans and the Austro-Hungarians received the shocking news that Romania had entered the war. The dramatic Russian victories convinced the Romanians that this was the golden opportunity to be on the winning side. Though their combat effectiveness was low, their attack against the right flank of the retreating Austro-Hungarian 7th Army pinned them long enough for the pursuing Russian 9th Army to hammer them to pieces. By then the Russian 11th Army was within twenty kilometres of Lvov, 120 kilometres from its start point. Russian cavalry and armoured cars were ranging far ahead of their infantry, running down or bypassing what remained of Südarmee.

Stavka, Mogliev, 23 June 1916

Jubilation ran through the headquarters at the news that Brusilov’s forces had entered the Lupkov, Volovets, Veretsky, and Delatyn passes over the eastern Carpathian Mountains with little or no opposition. Brest-Litovsk had fallen the day before. The Hapsburg armies seemed to have simply collapsed. Troops were surrendering everywhere. Divisions frantically transferred from the Italian front arrived piecemeal, only to be swept up in the panic. Only some of their ethnic German and Hungarian regiments kept together and fought, but they fought to escape.

On the 26th, Cossack patrols of 7th and 9th armies descended from the passes through the Carpathian Mountains into the Kingdom of Hungary. There was no resistance. Ahead of them, though, were a few Lanchester armoured cars that entered the town of Munkacs. The British crewmen thought it strange to see so many Hasidic Jews, not realising it was the only city in the Austro-Hungarian Empire with a Jewish majority. Lieutenant Clyde Sutherland walked into an empty police station, paused, and said, ‘I say there, anyone at home?’ With not a single member of the police or administration remaining, he ended up accepting the surrender of the city from the chief rabbi. The telegraph office was open, and he sent a telegram to the Austro-Hungarian emperor that the city of Munkacs had surrendered to the forces of His Majesties, George V and Nicholas II. The latter he included out of courtesy to their Russian Army translator. Of course, the Cossacks were announcing their arrival elsewhere with plumes of smoke from burning towns and villages.21

Budapest panicked at the news, and Vienna was stunned. That night Emperor Franz Joseph died in his sleep. The next morning his heir, Archduke Karl, summoned the cabinet and ordered them to sue for peace without informing Berlin. The Germans found out in two days; their outrage had nowhere to go. They calculated the odds, and began a strategic withdrawal from their most advanced positions in France to concentrate forces desperately needed in the east. Those reinforcements only succeeded in occupying Bohemia and Moravia to prevent any threat to south-eastern Germany. The British and French, noting the sudden withdrawal of the Germans, launched an immediate pursuit. For the first time in two years, the fighting was in open country as the Germans fought a stubborn retreat.

The Russians demanded that Vienna immediately order the cessation of hostilities and then sever its alliance with Germany. Vienna conceded with shameless haste. With the Hapsburg Empire not only out of the war but on the point of collapse, the Ottomans also realised the war was hopeless. Austria-Hungary’s capitulation severed German munitions and military support, without which the Turks simply could no longer fight on. They also sued for peace; the Bulgarians quickly followed. That immediately opened the Dardanelles sea route to Russia’s Black Sea ports for Allied aid. This truly was the handwriting on the wall for Berlin. Germany could fight on, but to what end? A rational observer could see only inevitable defeat in Germany’s future. It would only be a matter of time.

Berlin asked the Argentine government to offer its good services to broker a peace. In the end Germany did not come badly out of the Peace of Buenos Aires. Almost everyone did well because the prostrate Hapsburg state provided plenty of pickings. The Russians took all of Galicia and recovered most of their Polish lands. The Germans swallowed that by swallowing Bohemia and Moravia. The Romanians were awarded Transylvania, not so much for their feeble military contribution but for their timing. Serbia got a slice of southern Hungary and Bosnia-Herzogovina. Italy got the Italian populated parts of the Tyrol and Trieste. By the end, the Austro-Hungarian Empire was reduced to its German provinces of Austria, the remnants of Hungary, and faithful Croatia and Slovenia. France and Great Britain had to be satisfied with the evacuation of Belgium, Luxembourg, and France as well as a handful of German colonies in Africa. The status of Alsace-Lorraine was to be subject to a plebiscite. Britain was able to force a reduction in the German Navy since its recent drubbing at Jutland. Of course, there were pickings in the Ottoman Empire as well. Britain took Palestine, and France, pressing its ancestral claims, was ceded Syria. Russia took all of traditional Armenia in eastern Anatolia.22

The liturgy of thanksgiving for Russia’s victory was held fittingly in Christ the Saviour Cathedral across the Moscow River from the Kremlin. The cathedral glittered with thousands of candles reflecting off its brilliant frescoes, marbles, and mosaics; it was scented with clouds of fragrant incense and echoed with chants that seemed the voices of angels. It was only fitting that the celebration be held here. The cathedral had been built with the pennies of the Russian people in thanks for their deliverance from Napoleon. Now it celebrated a new saviour of Russia, in the place of honour next to the imperial family – Marshal of Russia Aleksesi Brusilov. Three rows back, behind the last of the imperial relatives and the senior generals sat Pyotr Stolypin. He had a new portfolio now. His mind was not distracted by the sensory feast around him. It ran into the future, and the reforms that would secure the Romanov dynasty for another hundred years.

The Reality

To this day a staple of Russian intellectual speculation has been what would have happened to Russia had Pyotr Stolypin not been assassinated in 1911. This chapter follows one path in that tradition. The presence of a figure with the ability and reputation of Stolypin to advise and influence Nicholas II would have been crucial in the events leading up to the Brusilov Offensive.

That offensive was planned as a supporting attack for the main effort to be made by Evert’s West Front and Kuropatkin’s North-West Front. In fact, both Evert and Kuropatkin were loath to make the effort. They were supposed to have attacked first, but to Brusilov’s rage they did not. Brusilov had correctly seen that knocking the Austro-Hungarians out of the war was the most feasible plan for the Russians, yet the overwhelming strength of the Russian armies continued to face the Germans. Nevertheless, with the resources he had, he broke the back of the Austro-Hungarian armies facing him, taking 350,000 prisoners. However, Evert and Kuropatkin’s continued failure seriously to attack the Germans meant that Hindenburg could send reinforcements from his front and Falkenhayn could send more from the Western Front in France to brace up the Austro-Hungarians. The Germans sent not only divisions but senior commanders who essentially took over the Hapsburg armies. Eventually, Brusilov’s offensive was ground down in the face of German control of the now-braced Austro-Hungarian armies, suffering half a million casualties by the time it was called off. That was the last serious Russian opportunity to achieve victory on the Eastern Front. What was overlooked in this spoiled victory was that Brusilov had originated an early form of the stormtrooper tactics the Germans would develop later in the war for their 1918 offensives. Also overlooked was the use of armoured cars for exploitation of Russian penetrations of the Austro-Hungarian front, a year before the British first used tanks at Cambrai.

With the coming of the Bolshevik Revolution and the Civil War, Brusilov threw in his lot with the Reds, reasoning that governments come and go but that Russia endured and must be served. He was not forgiven by the émigré Russian community which has clouded his reputation in the minds of many. Yet he was by far Russia’s finest commander in the First World War and a great captain by any standards.

The mad monk Rasputin was a mortal enemy of Stolypin, and it is not inconceivable that the minister’s streak of ruthlessness in dealing with the enemies of Russia might – if mentioned in the right ears – have resulted in the Russian equivalent of: ‘Will no one rid me of this meddlesome priest?’ Thus Rasputin’s murder was advanced in time to remove his opposition to the Brusilov Offensive. Lieutenants Golitsyn and Sutherland are the only fictional characters in the story.