CHAPTER II

THE BARBARIAN MOVEMENTS AND SETTLEMENTS

WHEN Augustus drew the northern limes of the empire at the Rhine and the Danube, he was not trying to delimit an ethnic frontier. He had regard rather to strategical considerations and communications: to the needs of military defence and of trade. The great rivers were in themselves defences: and they were also water roads, uniting the old native trade routes and the military roads of the army surveyors, many of which led up to the limes. A region cannot be defended if its roads are, as it were, the spokes of a wheel, with no means of travelling from the end of one radius to another, except that of travelling back to some junction between the spokes: some kind of road must be made to connect the ends of the spokes. This is very clearly shown when, in Britain, between A.D. 47 and 51, it was found necessary to make a new military road, the Fosseway, between Exeter and Lincoln, to connect the ends of the three military roads pushed out from London by Aulus Plautius. The Fosseway was only temporarily a frontier, for the three roads of the spokes that had been driven out of London soon passed beyond the Fosseway; but the great limes of the Rhine and the Danube, at once a water road and a defence needing no maintenance, was the Roman frontier for 400 years and more.

Augustus saw no need for any ethnic frontier. His empire indeed was singularly successful in dealing with racial differences within its boundaries. The bulk of its inhabitants spoke one of the speech varieties of the European half of the Indo-European speech family: Latin, Greek, Celtic, Gaelic, German, Slav. The provincials of north Africa, akin to the desert tribes of the Sahara, were an exception and not of Indo-European provenance; and on the Danube and the eastern frontier some Mongol and some Arab subjects acknowledged Roman rule. But there was no colour bar, no colour question in the empire, partly because Rome ruled no great number of subjects of colour much darker than her own Mediterranean races; and partly because the Roman administrators dealt with newly conquered additions to the empire on a basis of ‘culture’, in the archaeologist’s sense, rather than that of race. When the basis of Roman citizenship was gradually extended, it was without regard to race.

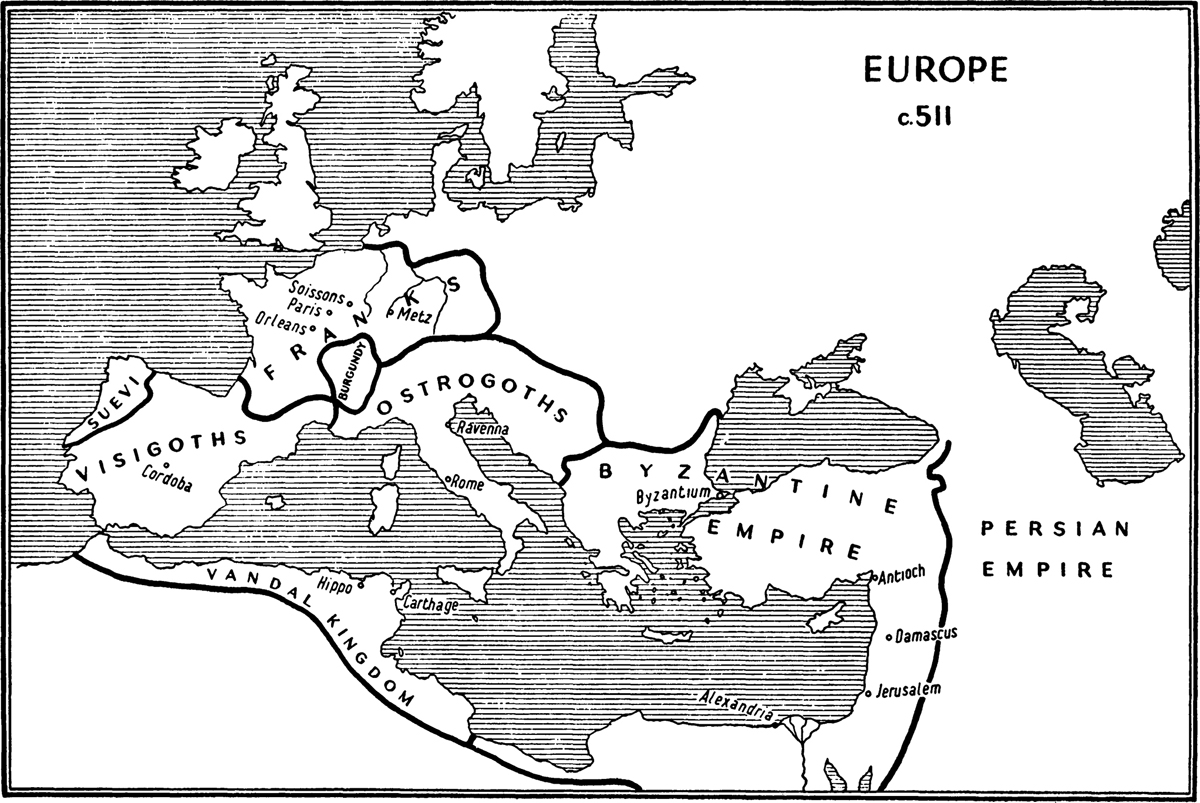

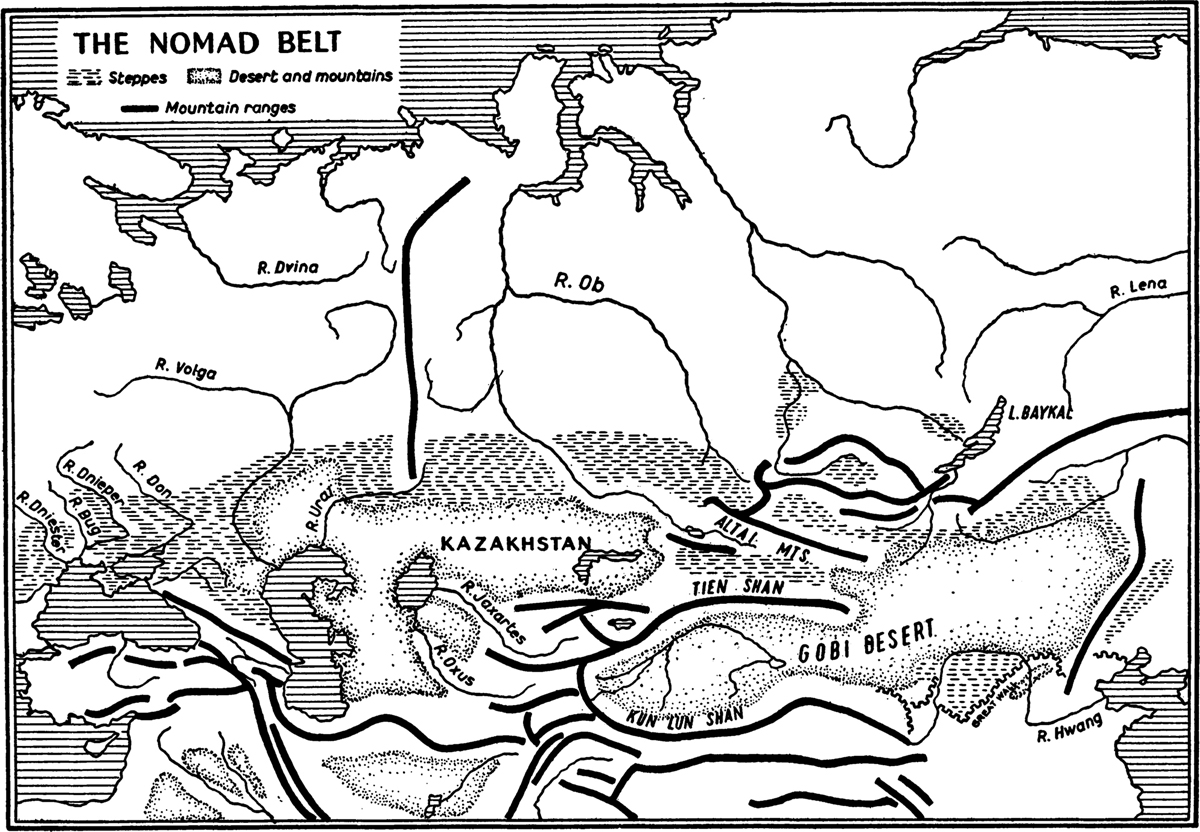

About the barbarians outside the Rhine–Danube frontier (for no great tribal immigration came from any other): they fall into two groups and two cultures, those of the Germanic peoples and the Tartars or Mongols,1 the nomads who came originally from the high grass pastures, the steppes, of Asia. While the Germanic migrations led to the setting up of new national kingdoms in western Europe, those of the Mongol tribes led to no important permanent settlement within the empire at this date. The nomads were, however, of great importance, as producing continuous pressure on the Goths and other Germanic tribes, as introducing them to the warlike possibilities of the horse, as producing the great Hunnish raid of 451, and, at a rather later stage, after 476, as leading to the settlement of certain nomad tribes of non-Indo-European speech, in the Balkans.

The European peoples, the parents of those who in early European history appear as the Goths, Vandals, Norsemen, Swedes, Danes, Russians, Germans, Franks, Anglo-Saxons, Lombards, etc., spoke a language deriving from the Indo-European speech family. The European branch of this primitive language, that is, had the same parent forms for the most commonly used words in Sanskrit, Persian and various ‘Indian’ tongues: so that in Persian and Sanskrit, Greek and Latin, Old Irish, English and Russian, and their various derivatives, words like father, mother, brother, sister, bread, etc., go back to a common root; the Greek word for house and the Latin word for village had a common root: Burnham Beeches in Buckinghamshire recalls the Bukovina in Roumania. To this speech family the tongues of the Germanic races belonged, and they were akin to the languages of the empire, Latin and Greek: but quite alien from that of the northern nomads, which would seem to have been akin to Chinese.

The European peoples, again, were at a different stage of civilization from the nomads; they practised a primitive agriculture, using a plough, and possessing sheep and oxen. The nomads, and the Huns among them, belonged essentially to the belt of grass pasture in central Asia and the Ukraine, and lived upon and by means of their horses and flocks; the word nomad comes from the verb for ‘to feed’, and the need to feed his cattle (or, indeed, his reindeer or his horses) determined the whole character of nomad life. There was no geographical barrier between the nomads and the Slav and Gothic tribes of central Europe, for between the Caspian and the Volga the gently swelling hills of the Arals constituted no natural obstacle: famine among the nomads of the Eurasian steppes led to pressure on their Germanic neighbours. There was also, back into prehistoric times, a trade route up the Russian rivers from the Black Sea, across the narrow stretch that unites them with the upper waters of rivers flowing into the Baltic, and down those same rivers: and where merchants pass, migratory bands and tribes can, on occasion, pass too. Tatar influence thus passed northward from the Black Sea, and the Finno-Ugrian tribes of the eastern end of the Baltic were akin in origin to the Mongols of the steppes rather than the Indo-European Germans. The high cheek-bone and Mongol droop to the outer fold of the eyelid derive from Tatar ancestry.

While the Germanic tribes had been pressing against the Roman frontier long before the fourth century, without occasioning the breaking of that frontier, the scale and the success of their attacks in the fourth and fifth centuries seem to have been due to pressure from the nomads. The term ‘nomad’, though excluding settled peoples, itself includes those of a range of development, between tribes for whom survival depended on movement too quick for flocks of sheep or goats, and those who could lead such flocks from pasture to pasture. There must, that is, have been development between the cultures of the nomads of the Asian steppes and those of the Ukraine.

In prehistoric, geological times, the Mediterranean sea had joined the Black Sea, the Caspian and the Aral, prolonging itself into a great Mediterranean sea of central Asia. In historic times, however, the most eastern part of this sea had long dried into a dry, salt sea bed, the zone of the deserts stretching from the Caspian sea to the Khin-gan mountains, the land of the steppes. Here the soil is too salt for cultivation: such moisture as falls evaporates, and no rivers reach the sea. Only with much irrigation are the most favourable parts of this old sea bed cultivable: the rest is a parched land, marked in spring by a bright, brief crop of luxuriant grass and the steppe flowers. In such land, from prehistoric times almost to our own day, only a primitive nomad people could have, and has lived, for life has depended on moving the tribe from the well-watered northern summer pastures to the Aral-Caspian basin where there is grass in winter. The country was too poor for a primitive agriculture. The nomads had acquired a special technique of living, taming animals and using them for food and transport: and the swiftest means of transport, making possible the greatest range of pasture, was found to be the horse. The Eurasian steppes were the land of the horse, and the only human life that could survive was life in the saddle. Only such crafts could develop as were consistent with such a life; only such kindly practices as regard for the young, the weak and the old, as were compatible with it, and these were necessarily few. On the other hand, the urgent need for mobility, for passing ever from the dried up to the fresher pasture as the sun drew to midsummer and back again, made the nomad races terrible as raiders to any settled or semi-pastoral people.

The need for swift movement, again, conditioned the whole apparatus of nomad life. Their dwellings were normally tents, and only for a great chieftain winter quarters even wooden structures. Their clothes were close-fitting and meant to preserve them from the extremes of heat and cold; all their possessions had need to be portable: weapons, clothes, horse gear.

The language of this great reservoir of Aral-Altaic or Tatar people of the steppes was certainly not Indo-European, though they bordered on Indo-European peoples both in Europe and Asia. In Asia they contended with the Persians and the tribes of the Himalayas and northern India, looting their metal work and textiles and borrowing their art-forms, as they did to a lesser extent those of the Mongols of China; in Europe they lived on the steppe belt that extended from the Volga to the Carpathians and the Danube, and struggled and contended with the autochthonous Cimmerians of south Russia, the Greeks and the Goths. Pressure from these nomads affected the migrations of the Germanic peoples in the early middle ages, and were to disturb eastern Europe throughout the middle ages. In two respects, however, the nomads were to have particular importance for the history of medieval Europe: their establishment of the brief Hunnish empire in the fifth century, and their contacts with the Slav peoples of medieval Russia. For their own settlements in Russia, their raids, and the Asian influences which they brought to bear on the Slav peoples throughout the middle ages, see chapter XXV.

Of one band of these northern nomads, the Huns, we know nothing for certain earlier than the description of Ammianus Marcellinus (+ 390), who wrote of them:

The nation of the Huns, scarcely known to ancient documents, dwelt beyond the Maeotic marshes beside the frozen ocean, and surpassed every extreme of ferocity.

Jordanes, who summarized and preserved the gist of Cassiodorus’ lost History of the Goths, and who admired both the Goths and east Romans, speaks of the Huns with a loathing which suggests not merely national animosity, for the Huns had defeated his Gothic ancestors, but racial antipathy: the Huns were

a stunted, foul and puny tribe, scarcely human and having no language save one which bore but slight resemblance to human speech: … they were fond of hunting and had no skill in any other art. They made their foes flee in horror because their swarthy aspect was fearful, and they had, if I may call it so, a sort of shapeless lump, not a head, with pin-holes rather than eyes. Their hardihood is evident in their wild appearance, and they are beings who are cruel to their children on the very day they are born. For they cut the cheeks of the males with a sword, so that before they receive the nourishment of milk they must learn to endure wounds. Hence they grow old beardless. They are short in stature, quick in bodily movement, alert horsemen, broad shouldered, ready in the use of bow and arrow …. Though they live in the form of men, they have the cruelty of wild beasts.

But long before the year 370, when the Huns, with their subject nomads, the Alans, overthrew the great Ostrogothic kingdom to the north of the Black Sea, and set the east Germanic tribes awandering, they had made the crucial discoveries: the shoeing of the horse, and the use of saddle and stirrups. Whereas the earlier nomads, like the barbarian auxilia used by the Romans, had ridden bareback, carrying only a light spear,1 the nomad horsemen, drawing upon the metal supplies of Asia as loot, had learned to travel great distances on their metal shod horses, to wear body armour, to carry a heavy sword, and to shoot on horseback with a metal bow. Their horsemanship was so expert that they normally held council and ate on horseback, and their enemies doubted if they could walk upon the ground. Their numbers were much smaller than early Roman writers, eastern or western, have suggested: but their effectiveness as shock troops suggests that of tank troops in the recent war. Though the Roman army had been remodelled to cope with them, the Goths could do nothing against them: nor could any other of the Germanic barbarians, till subjection or proximity had taught them a similar skill in making war. The Gothic kingdom of Ermanaric went down before them: in 376 fugitive Goths were permitted to settle south of the Danube, and in 378 they defeated and killed the emperor Valens at Adrianople, not, apparently, unhelped by the Huns: for not all the tribes of the nomads as yet acknowledged a single ruler. Nor did all the Huns appear exclusively later as the enemies of Romans, Goths or Persians: the new barbarians were divided among themselves and willing to ally themselves as mercenaries, and even to fight as mercenaries against each other. Those whom they served, and those whom they subjected, began to learn from them to fight as heavy cavalry; as, for instance, the Franks of central Germany. Even the Anglo-Saxon invaders of Britain, arriving as they did by sea, had as their leaders two Jutish warriors, named or nicknamed, Hengest and Horsa. Hengest is a ‘horse’ word with varying meanings: Horsa explains itself: and the names could scarcely have been given except in a tribe using and venerating the horse as an engine of war.

The Huns received very large tributes in gold and silver at times from the eastern emperor, at times from Aëtius or the ministers of the western emperor, who thus hoped to avoid or postpone attack. Some recent students of Hun society believe the Huns did not work the precious metals themselves, the difficulty of carrying about raw material and tools being too great: but what they lacked in their own crafts, they provided for themselves by loot, carpets from Persia, and the metal work of the Sarmatians, the Goths of the Crimea, and the Greeks. Both men and women wore much jewellery, brooches, torques and armlets, and they used the Greek (or Chinese) mirrors of polished metal. They helped to spread the nomad animal ornament among the Germanic races: the most frequently used reindeer with its horned hind as well as stag, and the frequently used bird of prey: from this creature came the beak-head ornaments, and such widely used forms as the bird of prey and the Daniel-in-the-lions’-den ornaments on the Sutton Hoo purse. One of the envoys of the Byzantine court to Attila, Priscus, describes the riches he found there: he came through ‘tented houses’ to the inner courts wherein were ‘wooden houses put together elegantly of carved wood, some having beams of gilded wood’. Here were pavements covered with woollen tapestries and here lived Attila’s wife.

In war, the nomads used powerful bows, shooting from the saddle: their equipment included also bow cases, sheath-knives, swords (and whetstones for sharpening them), javelins, shields and armour; on all these, and on their jewellery, the stylized animal ornament ranged from the sharply modelled reindeer to animals with Persian or Celtic hip and shoulder curls, and Persian and Chinese griffins and dragons. They used ‘dragons’ indeed for signalling between the bands of horsemen that rode the steppes: that is, they used dragon kites as standards. While in Europe the flying of kites (called after the forked-tail bird of that name) has been no more than a pastime, in Asia (China, Japan, Korea, Malaya, etc.) kite-flying was used in signalling and even in religious ceremonial. The Chinese concept of the dragon, as representing the animal world (part bird, part beast, part fish), was seen in concrete form in the flying kite, a creature with a mouth of metal through which the wind could stream, and a kite-tail, or body of cloth or paper. Europe got its concept of the dragon from the kite-flying Mongols, and even the Roman army, in the fourth century, adopted the light draco as the standard of the cohort.

The existence of this horde of steppe nomads threatened Asiatic civilizations at various times as well as European: and if the nomads detached Avars, Magyars, Bulgars and finally Turks in warfare with Europe, they attacked Asia as well. The Chinese, under the Han dynasty, drove certain nomads, the Hsiung Nu, out from China in the first century B.C., building walls and fortresses to keep them out; but the Han dynasty ended in 320, and rule in China was divided in the period of ‘the Three Kingdoms’ (320–589). The Hsiung Nu again pushed north-west into China and seized land north of the Yangtze, while the Chinese sought to push them back from the south. Though the Mongol dynasty did not prevail in China till 1280, there was ceaseless border warfare.

The west Germanic peoples first appear in written history as settled round the western extremity of the Baltic, in Sweden, Jutland, Sleswig-Holstein and the southern shores of the Baltic: this was, indeed, the home alike of the Goths, Scandinavians and the west Germanic peoples according to their own sagas and folk tales. Some of the west Germans moved south of the Baltic to the Rhine mouth in very early times. Caesar speaks of the Germans of the lower Rhine and Tacitus, writing his Germania in the year A.D. 98, describes them in the same region and along the south of the Baltic as a people just ceasing to be migratory hunters and reaching the agricultural stage. They had flocks and herds, ploughed a field for grain for a year or two and then left it fallow for a time to recover. The simplicity and loyalty of their tribal customs Tacitus compared very favourably with the political and social life of Rome: but here he is suspected of political bias. The pressure of these fair-haired, grey-eyed people on the Rhine frontier had, indeed, begun before his time and was continually more persistent. The legions of the Rhine could, however, in Tacitus’ day, as yet resist them: their camps had become the rich trading towns or Cologne and Trier, and the capitalist Roman traders planted the vineyards on the Rhine to supply them with wine, rather than transport it from Italy. A flourishing trade was done across the Rhine frontier. In 258, however, a band of Alemans crossed the Rhine and succeeded in occupying Rhaetia; and another branch of the same race, the Franks, attempting to conquer Gaul, were repulsed, but left settled bands there. The great home land of the Franks, on the right bank of the Rhine, was by this time the area later to be known as Franconia, the central duchy of medieval Germany, centring in the basin of the Main and the city of Frankfurt.

Meanwhile, while the west Germanic peoples were first moving southwards to the Rhine, the east Germanic peoples, including pre-eminently the Goths, had also moved southwards. They had come from Gothland, south Sweden, carrying from the cradle of their race the name Goths or Grentungi, as long ago as c. 500 to 300 B.C. They had now moved from the south shore of the Baltic and passed south-east of the Pripet marshes. By about A.D. 250 they had contact with the nomads of the steppes, and had founded a great, loosely compacted empire on the northern shore of the Black Sea, the river Dniester running through it. They had the Finns as their neighbours to the north-west, and to the east the Alans, a nomad tribe from Persia. They had also heard of the rich and civilized empire of the Romans south of them in the Balkans, and by A.D. 250 they moved south against them.

They were astonishingly successful, for they had apparently already learned from the nomads to fight as heavy cavalry. They killed the emperor Decius in a battle in the Dobrudja in 251, and pressed in 260 into the Balkans, unchecked by the emperor Valerian. They were not yet eager, apparently, to migrate in large bodies to the Balkans; in their extensive empire the Ostrogoths (or shining Goths) were settled round about Kerch, in the Crimea, and to the west of them, divided from them by the river Dniester, the Visigoths had an ample territory. By about 350 the whole of this loosely compacted empire was ruled by Ermanaric: a villain in saga, but strong and energetic; the Huns destroyed his kingdom in 376 and drove him in his old age to suicide. Athanaric, the judex of the Visigoths, also resisted the Huns in vain: his people in alarm poured south to the Danube and in 376 were allowed to settle: then, dissatisfied with the east Roman terms, or their keeping, and perhaps aided by a section of the Huns themselves, they defeated and killed the emperor Valens in 378, at Adrianople.

The Goths had won the battle of Adrianople by a charge of heavy cavalry, riding down the Roman infantry and the newly formed cavalry regiments. But against the Huns, their masters and teachers in the art of cavalry fighting, they could do nothing. The Ostrogoths north of the Black Sea pass out of history for a century, part remaining east of the Dniester in captivity to the Huns, part escaping and passing west of the Dniester. The work of the Christian missionary Wulfila, their ‘priest and primate’ as Jordanes called him, was mainly done before the separation of Ostrogoths and Visigoths: he died in 388.

The first great chapter in the history of the Visigoths was finished by the time Odovacar was made patrician in 476. Disturbed in their settlements south of the Danube by the raids of the Huns, whom the emperor Theodosius (378–395) could not stop from making settlements of their own in the northern Balkans, they pressed farther to the south. At the death of Theodosius, the Visigoths ‘deprived of the customary gifts (of the eastern emperor), appointed Alaric to be king over them … for he was of famous stock, second only to that of the Amals, for he came from the family of the Balthi, who, because of their daring valour had long ago received among their race the name of Balthi, that is, “the Bold”’. Jordanes then relates how in the year 400 Alaric raised an army and entered Italy: he crossed the bridge over the river Candidianus at the third milestone from Ravenna.

The Visigothic conquest of north Italy occupied the years 400 to 410; for many summers, before 410, they came over the head of the Adriatic; and, when they had established themselves in north Italy, it took Alaric three summer sieges to take Rome, and his success was at least partly due to the death of Stilicho, executed by the order of Honorius in 408. There was no one to replace him: and when Alaric besieged Rome for the third summer in 410, he took it. The houses of the Roman nobles were plundered and burned, but no general massacre followed; Alaric, though an Arian, spared the churches and ancient monuments; for the Visigoths, regarding themselves as federates, if rebels, came against Rome as desiring a place in the Roman sun rather than as wishing to destroy her. But none the less the shock of the city’s fall and the loss of prestige were very great: no such disaster had befallen Rome since the Gauls had sacked the city early in her history.

But though Alaric had Rome at his feet as a splendid prize, his people were peasants and desired grain-yielding lands rather than the olive groves, vineyards and restricted cornfields of Italy. Jordanes speaks of them before their entrance to Italy as ‘not even knowing that vineyards existed anywhere: most of them drank milk’. Alaric noted how the grain ships that fed Rome came from Sicily and north Africa, of which the Vandals had not yet possessed themselves. He planned to cross to Africa and set about collecting transport: but his ships were wrecked in a storm and he himself died towards the end of 410. No lordly tomb in the Roman manner, no barrow in whose heart he might sit in his chair surrounded by his treasures, was possible for this conqueror whose people were leaving him in a hostile land: so they buried him in a river bed, his sepulchre unknown. Athaulf, his brother-in-law, succeeded him as king and as leader in the migration from Italy.

Athaulf’s attitude to the Romans was one of intelligent admiration. He desired pre-eminence for the Goths, but he had no wish to replace Honorius as emperor of the west himself: he seems to have doubted whether his Goths could run so complex a concern as the Roman empire. He desired, however, that his people, as federates, should restore the vigour of the empire: he looked upon himself as a restitutor orbis Romani, though his brother-in-law’s decision to vacate Italy held. Transport to Africa having failed, he desired to settle in the Roman province of the Rhone valley, or indeed to possess himself of all Gaul, the most Romanized part of the empire outside Italy. He led his Goths therefore from the toe of Italy, where he himself had been awaiting transport at Alaric’s death, up through the narrow plains that lie between the Apennines and the western coast of the peninsula, through Turin, along the Mediterranean coast road to the Rhone mouth and Arles on the Rhone; then along the coast road to Barcelona, and, apparently misliking the aridity of the hills and valleys of Spain, he turned north again and recrossed the Pyrenees, this time at their northern end. By 412 he was in Toulouse, the future Visigothic capital.

Possibly Athaulf’s vacation of Italy was purchased by the honourable marriage allowed him by the emperors. The fifth-century emperors, as those of Byzantium later, saw no objection to intermarriage of the royal house with barbarian leaders or nobles, provided they were of sufficient status and had some claims to civilized manners. The two sons of Theodosius, Arcadius and Honorius, had a step-sister, Galla Placidia, a very beautiful and able woman, who was to have an extraordinary influence on her generation: Athaulf captured her in Rome and carried her off into Gaul. At Narbonne he married her, without imperial permission or any imperial recognition of his own status. Difficulties over this action and the cutting of his communications by a Roman fleet seem to have occasioned his move into Spain; at Barcelona Galla Placidia bore him a son, who soon died. When Athaulf died in 415, he ruled part of Spain and two-thirds of Gaul; he had stood for the Gothic admiration for things Roman, but there was a conservative minority among the Goths who did not share his admiration. His death gave the anti-Roman minority their chance: their leader, the Visigothic prince Sigeric, seized power, killed all Athaulf’s children by an earlier marriage and ill-treated Galla Placidia, but he was murdered after a week’s power by another noble, Wallia.

Galla Placidia was the subject of an agreement between Wallia and Rome in 415. She was to be sent back to Italy and corn supplies were to be sent to the Visigoths; in return, Wallia was recognized as federate ruler of Aquitaine (all modern France south of the Loire), and the Visigoths were to clear the Alans and Sueves from Gaul and Spain. The Roman provincials, in return for this benefit, had to suffer the Visigoths to be hospitati upon them: installed as patrons of their estates, receiving a third of their produce.

Galla Placidia’s career was, however, only begun. She married the patrician Constantius, who became co-emperor with Honorius in 421, and when Honorius died in 423, she became for twenty-five years the real ruler of the west, during the reign of her negligible son, Valentinian III. The court lived in Ravenna, fairly safe from barbarian surprise or capture and their communications with Byzantium by sea safeguarded by the Byzantine fleet. Already the builders of Constantinople had adopted the domed roof from Mesopotamia for Christian buildings (see chap. XIII), and Galla Placidia’s mausoleum in Ravenna, cruciform in plan and barrel vaulted, has a domed roof over the intersection of the arms and nave. This small church, its domed roof of blue and green studded with gold stars, and its mosaic of the Good Shepherd, adds to the charm of its proportions a splendour of colour which has survived the centuries. Galla Placidia lived less than a century after Constantine, but her mausoleum is eastern in form and colouring, as no doubt were the dress and manners of the court at Ravenna. Her career is an instance of the awkward mingling of the ruling classes of Roman and barbarian, and an example of Byzantine willingness to let a woman share in imperial rule. She died at Rome in 450.

Meanwhile, the Visigoths were founding a kingdom that included most of Gaul and Spain. Wallia ruled from the autumn of 415, his chief work for the preservation of Roman life being the clearing of the Alans from Spain, and the shutting of their friends, the Germanic Sueves, into the province of Galicia, the north-west corner of Spain. His successors prevented the Vandals from settling in any numbers in Gaul or Spain: Gaiseric, their leader, sailed for Africa in 429. The Visigoths also took the main share in repelling Attila at the battle of the Catalaunian fields in 451. By 476 they had possessed themselves of all Spain except Galicia, and when Romulus Augustulus was deposed, their king Euric was stronger than any other ruler in western Europe. His realm included the Pyrenees, and his power was focussed in southern Gaul: Toulouse was then, and usually, the Visigothic capital.

Another Germanic kingdom had also been formed in Gaul by the Burgundians, a people who had moved southwards from the Baltic towards the Rhine frontier before the Augustan period. Tall and blond, they were reputed by the provincials to have stentorian voices and enormous appetites; Jordanes says they were ‘mild in character, harsh in voice: and greased their hair with rancid butter’. By 286 they were pressing against Mainz, where the emperor Maximian organized a campaign against them. In the great westward expansion of the Huns in 405–6, they were driven across the Rhine. In 413 some were allowed to settle as federates, south of the Franks round Worms, Mainz and Speyer. But in 437 Aëtius, desiring to save Gaul, induced the Huns to attack and put an end to this first Burgundian kingdom of Worms: the story survived as the historical basis of the epic of the Nibelungs. The survivors of the catastrophe were, however, allowed to migrate south and settle in 443 in the basin of the upper Rhone; the district of Savoy became the medieval Burgundy. In the disturbed period before Odovacar’s seizure of power, their king Gundobad held the commanding position in Roman politics left vacant by the death of his uncle, Ricimer the patrician, in 472. They were, as a people, Arians: but their Catholic princess Clotilde was later to influence the fate of the Franks by her marriage to Clovis, conqueror of Gaul.

These Franks flowed over the Rhine frontier when it had been successively broken by the Vandals in 406, the Sueves in 409, and the Burgundians. They had not, like the east Germanic or Gothic tribes, long been subject to the influence of the east Romans before they broke the frontier; they had in the past traded with the legions of the Rhine, and even crossed the Rhine as early as c. 350: but they were still heathen, had kings (or representatives of the cyn, the royal cyn), and warrior nobles who formed their comitatus, and who were grey-eyed, clean shaven, yellow haired, and wore close-fitting tunics.

But if the Franks had had no commerce with the Greeks, they had been influenced by another culture than that of their Roman neighbours of the Rhine; they were in contact with the Huns, and were expert horsemen. The Franks who pressed against the Rhine, according to Gregory of Tours, when the British pretender to empire, Maximus, was holding out in Aquileia, were only the western fringes of a confederation of Germanic tribes whose homeland was the later duchy of Franconia. The basin of the Main, flowing westward into the Rhine, was the focus of the land of the Franks when for twenty years Attila ruled an empire stretching from the Caspian to the Rhine; and before his time Franks and Huns were neighbours in central Europe.

After the penetration of the Rhine, the Franks settled within it in two bands, the Salian Franks (temporarily) in modern Belgium and Holland, and particularly between the rivers Moselle (Sala) and Scheldt. They became federates, and supplied Roman soldiery: the Notitia Dignitatum in its lists of legions, cohorts and numeri, speaks of the Salii seniores and the Salii juniores. The other band of Franks, the Ripuarians, strove to settle on the banks of the Rhine, around Cologne and Trier, and with such success that the administrative capital of Roman Gaul, long Trier, after the breaking of the frontier in 406 had to be moved to Aries. In 410 Honorius, hard pressed elsewhere, made a treaty with the Franks, both Salian and Ripuarian, and recognized their settlements.

They were still thus settled when Odovacar became patrician in 476: their next great forward movement, their great advance across north Gaul under Clovis, began ten years later in 486. As to their fate between 410 and 486: they were gathering strength, especially the Salian Franks, but they were to some extent controlled by the imperial ministers, Aëtius and Ricimer and king Gundobad, and advance westward was blocked by a representative of the Roman ‘king’ of Soissons. Tides of barbarians swirled across Gaul and across Britain, with intervals of Roman recovery, temporary only; what Ambrose Aurelianus and Arthur did obscurely in Britain, Aegidius and Syagrius did at Soissons and in its surrounding territory. Conditions among the Roman provincials in Gaul were disturbed, but not so disturbed, either in Gaul or Britain, but that bishop Germanus of Auxerre (in Aegidius’ ‘Roman kingdom’ of Soissons) could visit Britain in 429 and (?) 447, to secure the province from the Pelagian heresy. Germanus had been a fine soldier before his consecration as bishop: finding the Britons harried by the Picts, he was well qualified to lead them in the campaign where they gained the Alleluia victory, in 429: when the moneyers wished to put a suitable image of him on the coins of his mint, they selected for the verso the die of an emperor on horseback, merely drawing a symbolic halo round his head. Gaul seemed in a turmoil, with the passage of barbarians through her, and their settlements and negotiations within: but not in such a turmoil but that Germanus could visit Galla Placidia and the emperor Valentinian at Ravenna in 448, to negotiate about the terms of settlement of the barbarians in Gaul. He died at Ravenna that year, and his followers brought his body back to Auxerre for burial; everywhere his body rested on the journey they set up signa crucis. It is an example of Byzantine influence working through Ravenna: Helena had discovered the Lord’s cross in the Holy Land, and churches were already built cruciform in the east and in Ravenna: but it was a hundred years before Justin I should send a relic of the holy cross to Poitiers, and the Irish begin to mark the place of burial with the Lord’s cross, set up on a tall, slender pyramid of stone.

Meanwhile, and before Odovacar took Ravenna in 476, other branches of the Germanic tribes, close in custom, language and race to the Franks, began the invasion of Britain. These were the Angles, Saxons and Jutes, from the region round the bay of Heligoland, and the Rhine mouth, and from the hinterlands of these coasts. Hengest and Horsa were invited by the Vortigerna, a Welsh overking of Britain, to come as his foederati to defend Britain from the Picts, and possibly himself from other rivals for leadership. They came in three ships in 449, received land in Kent, were dissatisfied with their reward, and fought against the Vortigerna and the Romano-British provincials, establishing their headquarters in Canterbury. Other bands followed, and though the Celtic war-leader Arthur held up the Saxon advance for a generation between 516 and 537, they were in possession of most of ‘England’ by the end of the sixth century.

BIBLIOGRAPHICAL NOTE