CHAPTER XI

ISLAM: ORIGINS AND CONQUESTS

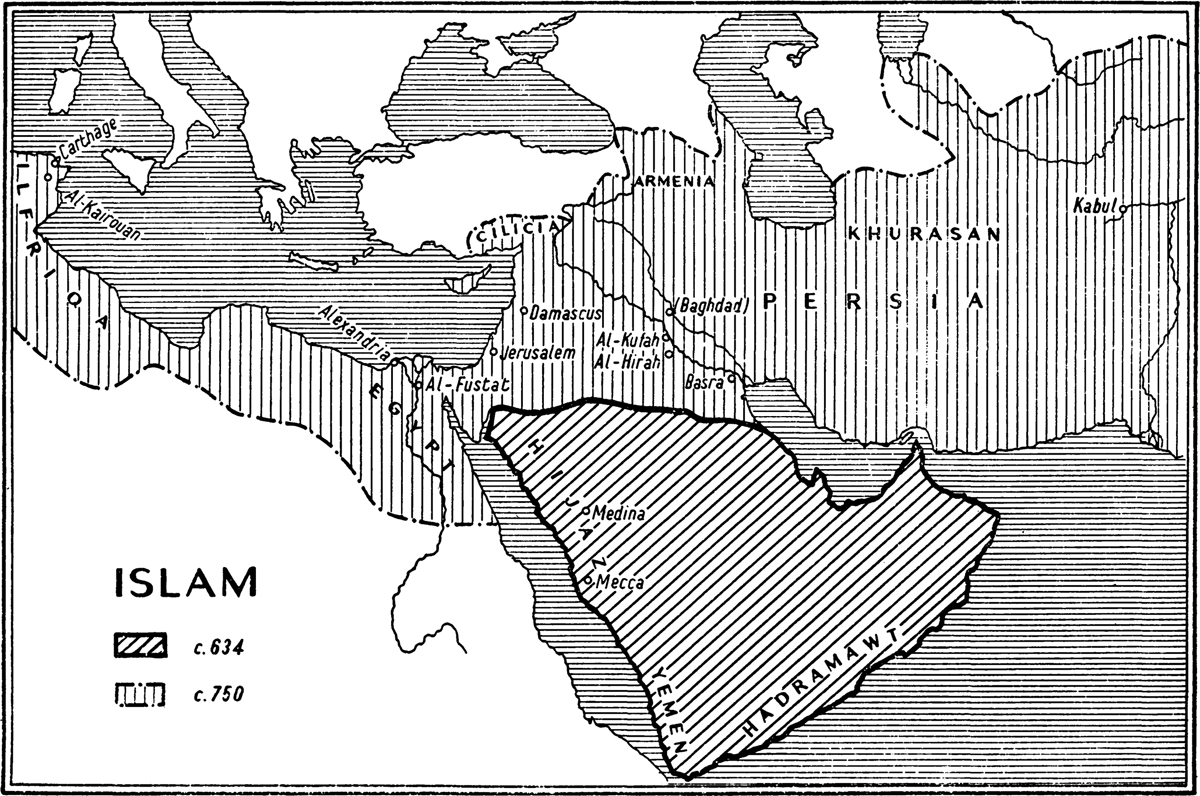

THE impact of Islam on medieval Europe cannot be ignored, though, strictly speaking, Islam was an eastern and not a European civilization, empire and religion. The medieval world scene knew three power blocs, not nation states, but civilizations held together by common religions and traditions. ‘Throughout the middle ages, a man is a Christian or a Muslim first, a native of his own home district and subject of the local lord next, and only last a Frenchman, an Egyptian or a German’ (Grünebaum). The three power blocs were: the kingdoms of the Germanic races in western Europe, with Latin as their common tongue, and a religion looking to the patriarch of the west; the Greco-Roman empire centred at Constantinople, using Greek as a common and a legal language, though the various eastern patriarchates allowed the use of vernacular liturgies; and Islam, which was in origin an Arab religion, an Arab state and, even when non-Arab races had come to outnumber the Arabs, continued to use Arabic as a common, liturgical, legal and literary tongue. Territorially, Islam a hundred years after Muhammad’s death, when her first conquests had been achieved, held only the southern fringe of Europe: Spain, Sicily, and some of the Mediterranean islands; but she held north Africa and the east Mediterranean: and remembering how largely early medieval Europe was still a Mediterranean civilization, as the Roman empire had once been, it was of the gravest consequence that Islam shared the Mediterranean with Europe, which she thus girdled and contained. Economic development in western Europe was restricted, the territories of the eastern empire diminished and her activities deflected; and slowly, gradually, the learning and the art of the Latin west and the Greek east were infiltrated and influenced by those of Islam. The history of Islam may seem to lie outside that of Europe, but the character of the great, warm, southern civilization: warlike, religious, learned, sensuous, needs appreciation for the understanding of medieval Europe. To such appreciation, the beautiful illustrations in N. A. Faris’s The Arab Heritage may be a first clue.

As to the relations of these three power blocs: it has been pointed out that, while Latin and Greek Christianity claimed legitimate succession to imperial Rome, Islam had no claim by origin to share in the Roman tradition. But she took possession of provinces once part of the Byzantine or Latin empire, and hence appropriated Greco-Roman traditions of finance, learning and architecture. With only tribal organization and an oral literature at her origin, Islam took over the Roman, Persian and biblical backgrounds as her own and, perhaps most important of all, she took over the administration and cultural heritage of Hellenism. She learned administrative and imperial practices from the Byzantines and the Sassanids; her science, philosophy, art and architecture were deeply influenced by Hellenism. ‘It was only the transfer of this heritage to the terms and conceits of the Arabic language and its harmonization with koranic requirements that gradually made the Muslims forget that process of borrowing of which in the beginning they had been perfectly aware.’ Islam was a succession state of Alexander’s Greco-Persian empire, and in one sense a succession state of the Greco-Roman empire as well, so that the thought of Islam, as well as her art and architecture, had something in common with those of the other two power blocs.

Furthermore, Islam was important to Europe as a transmitter and carrier of culture, using the word of social usage as well as learning. Arabic was her original and became her classical language. It was, before the days of Muhammad, one of the Semitic languages spoken only by the nomads and sedentarized nomads of the Arabian peninsula; but between the death of Muhammad in 632 and the halting of the Muslim advance by the Franks in 732, the Arab conquerors spread their language and religion over Egypt, north Africa and Spain in the west, and over Syria, Armenia and Persia in the east. In a century when (as Arnold Toynbee has shown) the means of communication, the links that held civilization together, were the camel, the horse, and the boat that passed over rivers and canals as well as the open sea, Islam held that region of central Asia that joined China and India to Persia, and Persia to Syria, north Africa and Spain. Islam, that is, was really a ‘junction culture’, in the days before the fifteenth century, when no ship had as yet linked Europe, Asia and Africa together by passing round the Cape of Good Hope. When that happened, horse and camel were to some extent displaced, and a different linkage of empires and cultures arose; but from the eighth century till the fifteenth the great land mass of the three continents was held in a certain unity of trade and culture by Islamic merchants, scholars and caravans. The Arabs were great carriers. The old civilizations of India and China had contact with Arab-conquered Persia: with the Arab-conquered Byzantine provinces of Armenia, Syria, Egypt and north Africa: and with Arab-conquered Spain.

If Arabic and the Indian learning (notably mathematics) did not spread faster than they did to Italy and the countries bordering the Mediterranean (and they spread notably slowly), it was not only that Arabic is a difficult language to learn, but because the three great power masses, the Muslim caliphates, the Byzantine empire and the Latin civilization of the west, were not much interested in each other. Distance, difference of language, relative economic self-sufficiency, difference of religion and everyday habits made for isolation, and a certain antagonism. Moreover, in theory each civilization was supreme, with a divine mandate to world supremacy. The three great cultures turned, as it were, their backs on each other and faced outwards. Expansion also was outwards: Latin Christianity expanded towards the Celts and the Scandinavians; Greek Christianity pressed northwards up the Balkans, to the middle Danube and to south Russia; Islam expanded towards the Berbers of the Sahara, the nomads of central Asia, and the tribes of north-west India. The Christian world before the Crusades devoted little enough attention to Islam, but it received less. The Byzantine empire, having suffered more at the hands of Islam than the Latin west, was more apprehensive and conscious of Islam than western Europe: and also more apprehensive and conscious of Islam than Islam was of her.

With Islam, political domination was co-extensive with religion. Till 745 the three caliphates were still one, as the dar-el-Islam, the part of the world already conquered for the religion of Allah, and his prophet, Muhammad: the rest of the world was the dar-el-harb, the house of war, the part as yet to be conquered. The known world consisted of the three continents, Europe, Africa to the south of the Sahara and Madagascar, and Asia; and, in this great, triple, land mass, Islam held the areas of communication: the Mediterranean, with its southern, eastern, and some of its northern shores: Syria and Armenia: and the central Asian steppes and plateau that led to China and India. In the realm of world strategy, she acquired a dominating position, and acquired it by conquest and the sword.

The question of the origins of Islam, and the cause of her swift rise to power, have long engaged historians. That a single Arab prophet and his followers should win, before his death, an ascendency in the Hijaz and Mecca its capital was not surprising; but that these same followers should, within a generation, defeat the Byzantine and Persian emperors and spread Arab rule from Sind to Tunis, was very surprising. It has long been recognized that the mutual exhaustion of the Persian and Byzantine empires gave the followers of Muhammad their opportunity; it has more recently been realized that the untutored Arabs founded a civilization because they absorbed the culture of their newly conquered Greek and Persian provinces, that the ruler of Islam was, as it were, the ghost sitting robed and crowned on the throne of Alexander; more recently still, the origins of Islam in Arabia, and her debt to Judaism and Christianity, have been intensively studied.

The pre-Islamic background in Arabia itself has been studied from epigraphic evidence and the scanty, literary references of Hebrew, Latin and Greek writers. The Arabs themselves had only poetic literature till Muhammad composed the Qur’an. Arabia is a large, barren peninsula, perhaps once more fertile: her wadi’s were once dried river beds, but long before Muhammad’s birth. Her population was Semitic, and in his day still mainly nomad, though sedentarized round certain oases and wells. Two very old civilizations had existed, one in the south and one in the north of the peninsula, as ruins (not yet scientifically investigated) still testify. The south Arabian civilization, with its four kingdoms, the Sabaeans (‘the kings of Arabia and Saba shall bring gifts’), the Minaeans, the Hadramautians and the Qatabanians, had a language different from classical Arabic and similar to Ethiopian, of which it is the parent. Their script was related to the Phoenician; their people were traders, producing and conveying frankincense and spices up through western Arabia and along the Red Sea to Egypt, and through Gaza to the Mediterranean. While these south Arabian kingdoms flourished, northern Arabia was poor, a country of half-starved nomads, ever streaming out against the cultivated land on their borders, in Syria and Mesopotamia.

The conquest of Alexander, on the other hand, had important repercussions in the north of Arabia as against the south: a civilization arose, less old than the southern, and stemming from Mesopotamia. Sedentarized Bedouins here used an Aramaic tongue for inscriptions, and Arabic for their everyday language. The first north Arabian state of which any detailed information is available, that of the Nabataeans, built such cities as Petra (the ‘rose red city, half as old as time’), Basra (Bosra), and even an early Damascus. They captured south Arabian trade, and the southerly kingdoms declined; but not before the south Arabians had crossed into Africa and founded the kingdom of Ethiopia (Abyssinia), at the beginning of our era. But all this while the great central fund of central Arabians remained nomad.

When in 63 B.C. Pompey led an army to Syria, the Nabataeans as Rome’s allies appeared for the first time in world history. They succeeded temporarily in fusing Greek and oriental elements with their own population, and might have antedated Islam as a junction state between Europe and Asia; but they were never more than caravan states and lacked Islam’s religious fervour and her genius for fighting. Above all, they faced the Roman empire at the peak of its power, remaining only a pawn in Roman politics. Trajan in A.D. 106 turned the Nabataean kingdom into provincia Arabica. Three cities throve in the Nabataean decline: Edessa, which introduced Christianity into northern Mesopotamia and Ctesiphon: Dara on the Euphrates, which controlled the Indian trade coming up the Persian Gulf: and Palmyra, an emporium on the caravan route from the Euphrates to the Syrian coast.

A curious ‘dark age in Arabia’ succeeded these early civilizations in the north and the south: the Bedouin influence, the nomad life, spread as the standard of life fell. The desert extended itself over land once cultivated, and in both south and north Arabia a transition from urban to rural life comparable to that known by Europe in the fifth century followed. The influence of Rome and Sassanid Persia seems to have blocked the old eastern trade and Arabia was much more isolated than she had been earlier. The kingdoms had perished with the cities, though in the south a Himyarite kingdom preserved its power between the fourth and sixth centuries A.D., between two conquests from Abyssinia. In this dark age, of which there are very few literary records, Judaism found many proselytes in south Arabia, and Christianity, both Nestorian and Monophysite, penetrated from the north.

In this dark and hungry period also, waves of Arabian migration from south to north set up two new states: that of the Ghassanids, who ruled the inland territory beyond the Jordan, Damascus and Antioch, and al-Hirah on the Euphrates and the western shores of the Persian Gulf; the Ghassanids looked to Byzantium and the Lakhmids to the Sassanids for protection and tutelage. The population of both states, semi-sedentarized Bedouins, had embraced Christianity, but while the Ghassanids were Monophysite, the Lakhmids were Nestorian. The road of Islam up the ’fertile crescent’ of the east Mediterranean was prepared in local political and religious rivalry. It was prepared also by the nomadism which had become again the dominant feature of Arabian life. The gleam of civilization in north and south had almost faded, and the Arabs, using their Arabic tongue, reverting to Semitic nomadism and to their old local cults, and largely hunger-driven, were ready to react to Muhammad’s preaching. Drawing his inspiration from the north, not the south, his efforts arrested this decline to nomadism, for he assailed the tribal organization, and preached a way of life foreign to that of the Bedouin. The Islamization of Arabia changed the nomadic pattern of life.

In two respects, however, the fifth and sixth centuries laid foundations for Muhammad’s work: the fusion of the tribal dialects into a single Arabic language, and the practice of tribal government under an elected sheikh. While in the Arabian peninsula ‘the only exception to the nomadic way of life was the oasis’ (B. Lewis), the oasis of Kinda succeeded in uniting the central and northern Arabian tribes into a petty kingdom. Through Kinda fine poetry, a common poetic language and some orally transmitted learning passed generally among the Bedouin tribes. Moreover, the tribal nomadism of the Arabs was to condition the secular organization of Islam in the generations immediately succeeding Muhammad. Each tribe was headed by an elected sayyid or sheikh, who acted as arbitrator within the tribe and was advised by a council of elders called the majlis, the representatives of clans within the tribe. Tribal life was regulated by ancestral custom, the Sunna, and violence was limited by the primitive obligation of the blood feud, or obligation on the family of a murdered man to pursue and kill the murderer. The election of the sheikh and the obligation to observe the Sunna were to be of political importance to Islam.

Against such a background, but himself a member of the sedentarized tribe of the Quraish, the guardians of the Ka‛ba or building housing the Black Stone of Mecca, Muhammad was born, in 570 or 571. His father died before his birth, and he was brought up by his grandfather and his paternal uncle, abu-Talib. There are no sources for his life other than Arabic, and the earliest Arabic life of the Prophet was composed in 767, 135 years after his death. There were Christians and Jews in Arabia during Muhammad’s youth, and from them he may have learned orally about their beliefs; the evidence that he made a journey with abu-Talib into Syria at the age of twelve is now disputed, and it is unlikely that he then first came into contact with Christian teaching. When twenty-five years old, he married Khadijah, the widow of a well-to-do merchant, and fifteen years older than himself. While she lived, he would have no other wife, and he found in her a supporter of his prophetic desires to speak to his people. He now had leisure to pray and meditate, withdrawing often to a little cave outside Mecca called Hira. It was here that he received the call to prophesy, and the words of this and later revelations are recorded in the surahs of the Qur’an.

Since the religion taught by Muhammad was to be the foundation and driving force of Islam, his own religious background and borrowings are of interest. In what was later called the Jahiliyah (the time of ignorance before Muhammad’s mission), religion was to the Arabs an affair of the clan, each of which had its local cult. A diffused animism, with local gods, goddesses and fetiches, prevailed. At Mecca, veneration for the goddesses Manat, al-Lat, al-’Uzza, and the god al-Lah (‘who is greater than they’), was connected with veneration for the famous Black Stone, the Ka‛ba. Allah was, in fact, the most notable of the gods of the Arab pantheon and the god of Mecca, which, with its spring, marked an important stage for caravans on the route to Basra. There, in the simple, roofless, gateless enclosure, the Quraish guarded the Ka‛ba, an object of pilgrimage in the grape harvest and the scene of a popular fair. There was no cultivation at Mecca: Arab riches came entirely from trade, and Arab religion, itself very primitive, was now contrasted through the caravan trade with the Zoroastrianism of Persia, the sectarian Christianity of Syria, Egypt and Abyssinia, and with the teaching of a strong Jewish colony at Yathrib. Christianity and Judaism were monotheist, in contrast to the local animism, and, of the two, Judaism had apparently the stronger influence on Muhammad. Besides the influence which Judaism and Christianity had already attained in some of the tribes, an Arabic source states that the Quraish had already received some knowledge from a sect of Christianized Gnostics, the Zandaqa. Muhammad was deeply stirred at the concept of the unity of God; he did not at first identify the one God, the merciful, the compassionate, with the Meccan al-Lah. For a time he directed that the posture of praying among his followers should be towards Jerusalem, the central shrine of Judaism and Christianity: later, he ordered that it should be transferred towards Mecca, as the shrine of Allah.

As to the sources of Jewish and Christian influence: the Christians of the north have been already mentioned, and there were Christians also in Yemen (southern Arabia) and Abyssinia. In 523 the Abyssinians had taken the Christians of Yemen under their protection. But from the second century there was a stronger and more renowned Jewish community at Yemen, in contact with Jewish centres in Syria and Babylon. The Jewish community had formerly been predominant also in Yathrib, the scene of Muhammad’s first triumphs, and to become al-Madinah (Medina), the city of the Prophet. Yathrib seemed, indeed, on the way to becoming a kind of Jewish commonwealth, with the Synagogue for its state church. It had been an old colony from Palestine and had rabbis of great distinction: Muhammad s biographer, ibn-Ishaq, compiled a list of them, commending their mastery of the Torah. Later, the first two caliphs frequented the Jewish ‘house of learning’ at Medina, in order to understand the better the Prophet’s teaching.

The contact between Mecca and Medina had, even before Muhammad’s day, given rise to a certain Jewish-Christian monotheism embraced by some Arabs, and even some of the Quraish. They professed ‘the religion of Abraham’, an embracing monotheism: and regarded the setting up of the Black Stone as the work of Abraham, connecting the city cult with the universal monotheism they professed. Mecca, that is, as the capital of a great commercial empire and the site of a local Arab cult, was marked out to be the holy city of Islam. Its cult was of sufficient importance in the year of Muhammad’s birth for the Abyssinian viceroy of Yemen to send a great expedition to Mecca, expressly to destroy the Ka‛ba, as the central shrine of Arabic paganism. It failed; but there were plenty of Jewish and Christian influences abroad in Mecca, and when forty years later Muhammad sought to bring the common people of Mecca to a belief in one God, he had no great difficulty in converting them: the ground was prepared. It was from the leading families of the Quraish, with their tribal and functional interest in the shrine, that he met with opposition.

The two older religions made another contribution to Islam of the first importance: the art of writing and literacy, the all-important agent of Muhammad’s success. There was no written Arabic literature before Muhammad; some inscriptions even in the north and south were in older tongues (though a few were in Arabic) and in more recent times in Aramaic. The considerable Arab literature of pre-Islamic days (poetry, folk lore, proverbs, etc.) was all handed down orally, and was only committed to writing later by the piety of Muslim scholars. The writing down of Muhammad’s revelations in the Qur’an was of the first importance for culture as well as religion. It was the first Arabic book. The need to study the Qur’an became the foundation of Arabic scholarship.

Muhammad himself could not write: but he had, later, a secretary who could, in the Medinese scribe, Zayd-ibn-Thabit; there were very few able to write in Arabic at the time. It has been suggested that the art of writing Arabic came from the Christian scholars of al-Hirah and was introduced by them into the Hijaz. We hear of a Meccan Christian who wrote the Gospel, in Hebrew letters, and it has been suggested that Arabic translations of the Gospel were written in Hebrew characters. Hebrew characters were also used in writing Aramaic texts. Muhammad knew also of the scrolls and folios in which the Jews treasured their sacred literature. The writing of Arabic was in his time still fluid and imprecise: but the Aramaic and Hebrew, and above all, Syriac characters were chiefly used in the evolution of an Arabic script.

There was no deliberate hostility to the two older monotheisms in Muhammad’s day, and Islam was at first meant to be a synthesis of those who, professing them, were willing to accept Allah as the one God and Muhammad as his prophet. Although in Muslim theory the Qur’an is literally the word of God, Muhammad had, in fact, no scruple in borrowing from either of the older religions; but he borrowed most from Judaism. To him, both Jews and Christians, but the Jews especially, were the people of a Book, the Jews of the Torah (the Pentateuch) and the Christians of the Evangel (the Gospel). The writing down of the Qur’an was a deliberate emulation of the two older religions, and Islam became, like them, the religion of a Book. The creation of the Qur’an (written down by others) was perhaps Muhammad’s most considerable achievement: it equated the Muslims with Christians and Jews, and it brought literacy to the Arabs. Arabic was a literary vehicle sensitive to many shades of meaning and able to express, not only the thoughts of an Arab merchant and his paraphrases of biblical stories and rabbinical teaching, but also abstract ideas and mathematical concepts. The study of the Qur’an, and therefore of Arabic, was known to be acceptable to God. ‘We have made (the Qur’an) easy in thy tongue,’ said God to Muhammad, ‘that thou mayest thereby give good tidings to those who show piety.’ Arabic became to Islam the idiom of piety, science and the People of Paradise.

Many expressions in the Qur’an came ultimately from the Jewish and Christian scriptures, either as already in use in Mecca in Muhammad’s day, or as borrowed by him: expressions such as ‘Day of Judgment’, ‘Hellfire’, ‘Shaytan’ (Satan). They were widely used in Syriac and western Aramaic, and the immediate sources of Muhammad’s knowledge of them are not easy to distinguish.

Muhammad, or later Islamic theologians, regarded the corpus of his revelations as the embodiment of a book already existing in the mind of God, the earthly image of a heavenly Qur’an. With this thought of a ‘heavenly book’ in mind, Muhammad often spoke of God as ‘writing’ in the sense of establishing a decree or issuing an ordinance. All authority, in Muhammad’s mind, is connected with the heavenly book. So Moses had been given the Book and Salvation: so Jesus acted and suffered that a word of scripture ‘might be fulfilled’. The revelation to Moses was primary, to Jesus secondary as confirming that of Moses, and to himself, final. He makes God say of Moses ‘We gave Moses the Book … we gave Jesus the Evidences.’ The Rabbis taught that disregard of the Book and the Evidences was sin: and Muhammad taught it of the Qur’an.

As to his own position in the history of revelation, and his use of the terms Islam and Muslim: Muhammad felt the analogy between his own position and that of Abraham, who passed from primitive religious belief to monotheism. He speaks of such uninstructed monotheists as Hanifs:

Who is more beautiful in religion than one who surrenders himself to God in sincerity and follows the confession of Abraham as a heathen? … Abraham was not a Jew, nor was he a Christian; rather, he was a heathen [hanifan] surrendering himself to God (musliman) and not one of the idolators. (J. Obermann.)

Islam is surrender to God, and the Muslim he who surrenders. All is written in the heavenly book, and he who so surrenders follows willingly his predestined path; but whether he follows it willingly or not, his fate is predestined. Next to Muhammad’s incommunicable experience in the cave on Hira, the theory of revelation as it had come to him through Judaism was the chief factor in shaping his career; each chapter, surah, in the Book was the record of a revelation, a sign, a command, greatly though the surahs differ in character and moral worth.

Four other points may be mentioned in connexion with the Qur’an.

First, Muhammad claimed to be the Messenger of God to all men; scholars differ as to whether Muhammad conceived of his own commission as extending beyond Arabia, or indeed to the whole human race. He failed, however, to win over the people of the Torah and the Evangel. He did win over his own people, and in time an ever-increasing number of other races and communities accepted Islam: predominantly those at the same stage of civilization as his own Arabs.

Secondly: there is a great contrast between the long history of revelation among the Jews, and even the Christians, and the single writing down of the whole canon of Muhammad’s revelations: even though this was supplemented by hadith, the traditions of the Prophet, written down later.

Thirdly: scholars agree that, though a considerable amount of biblical matter is embedded in the Qur’an, Muhammad can have had no first-hand acquaintance with the scriptures. He can have used no text or translations. He had acquired his whole store of scriptural knowledge orally, and probably from the exposition of non-canonical literature, especially the rabbinical Agada. He had clearly visited the synagogues. He had heard expounded the ‘non-canonical periphery of scripture’, the Targum and the Midrash; and heard also expositions of apocryphal and homiletic Christian writings.

Fourthly: Muhammad taught about man’s future destiny a doctrine of reward and punishment at the last day, the final reckoning. The heavenly book should be opened, and each man placed on the Right Hand or Left Hand of God. In the early surah’s (those concerned with moral precepts rather than the administrative orders given as revelations in Muhammad’s later career), a Muslim is qualified to sit on the Right Hand mainly by the practice of prayer and almsgiving. He shall, we are told, set the bondman free, feed the hungry in the day of famine, endure and have compassion, pray and be mindful of the Name of God, and give to the beggar and the outcast.

To return to Muhammad’s career and the political history of Islam.

Muhammad’s first preaching as the messenger of Allah met with small response, though Khadijah his wife, his cousin Ali and their kinsman abu-Bakr were early converted. The Quraish found his teaching heretical and opposed to their economic interests, and as the number of converts increased, resorted to persecution. In 615 certain Meccan families among his followers emigrated to Abyssinia where the Christian negus protected them. Persecution became hotter, but ‛Umar, the later caliph, became a believer; Khadijah and abu-Talib died; in later tradition (not in the Qur’an) Muhammad now announced his own mysterious nocturnal journey to Jerusalem, a parallel to Christ’s temptation before his ministry; Muhammad, however, was said to have travelled on a winged horse with a woman’s face and a peacock’s tail, and was borne up to the seventh heaven. In 620 the men of Yathrib invited him to settle with them; and believing his cause hopeless in Mecca, Muhammad and his followers in 622 made the hijra (hegira: the flight) and slipped quietly into Medina. Here he found himself an honoured chief, the chief magistrate of a community, and in 624 he and 300 Muslims raided a caravan of 1,000 Meccans at Badr, and won the first military victory of Islam. Further minor engagements of Medinese and Meccans followed. Within Medina, agreement between the Meccan immigrants, the Medinese and the Jews was confirmed by Muhammad by proclamation. Over this new community, the Umma, he alone had jurisdiction. Though each tribe retained its old customs and privileges, only the Umma could make peace and war.

During his residence at Medina, 622–632, the Prophet broke with Judaism and Christianity, appointed Friday instead of Saturday as a sabbath for his followers, ordered the call to be made from the minaret, instituted the fast of Ramadan, and authorized the pilgrimage to Mecca and the kissing of the Black Stone. Islam was nationalized as an Arab religion. In January 630, he was strong enough to enter Mecca and smash the many idols of the sanctuary, none protesting. The territory round the Ka‛ba was declared sacred and forbidden to non-Muslims. Three months after his own pilgrimage to Mecca in 632, Muhammad died.

The problem of succession to the Prophet was not easy. He had had, apparently, nine wives, but his son Ibrahim had died. The community of Muhammad’s followers (for ‘every Muslim’, the Prophet said, ‘is brother unto every other Muslim’) found themselves a theocracy, with no priesthood except the leader in prayer at the mosque, the imam, acting as commander of the faithful. Abu-Bakr, the Prophet’s father-in-law, by a kind of coup d’état, became his caliph or successor, though not without the opposition of certain tribes. Islam had, in any case, no precedent for hereditary succession, but only of the tribal election of a new sheikh. Abu-Bakr was of the tribe of the Quraish, and acceptable to the Medinese, but the more distant tribes who had accepted Muhammad’s rule by treaty or contract, regarded themselves as freed from their contract by his death, and entitled to elect themselves new sheikhs. They did not formally reject Islam, though Islamic tradition termed their movement for independence the Ridda, or apostasy. Within the short rule of abu-Bakr (632–634), these more distant tribes were forced to acknowledge the new caliph, at the point of the sword. The wars of the Ridda, traditionally represented as a war of reconversion, led to wars of conquest far outside the boundaries of Arabia. The real beginning of the Arab conquests was the victory of Khalid, abu-Bakr’s chief general, at ’Agraba in 633, in the eastern Najd (central Arabia). This was a battle in the Ridda war.

The strategy of the Islamic wars of conquest was the strategy of the desert, with which the Arabs were familiar and their opponents not. ‘They could use it as a means of communication for supplies and reinforcements, as a safe retreat in times of emergency’ (Bernard Lewis). When they conquered a new province, they established a base on the edge of the desert, like al-Kufa and Basra in Iraq, or Qairawan in Tunisia. The conquests had an inconspicuous beginning when Khalid sent small raiding forces into Palestine and Syria, withdrawing to the desert with their plunder. In response to these raids on Byzantine provinces, the emperor Heraclius mobilized an army: but Khalid moved swiftly from Iraq (the region of the lower Euphrates), and looted Damascus without Byzantine opposition in the spring of 634. His followers dispersed in Palestine and threatened the safety of Jerusalem, the scene of Heraclius’ earlier triumph. Heraclius therefore prepared a larger army, which was defeated by a far smaller force of Arabs at the battle of the Yarmuk river, in July 636. Khalid followed up his victory by conquering the whole province of Syria, which gave him access both to Persia and Egypt: to Iraq he already had access. He held a position of great strategic importance.

The conquest of Iraq was actually initiated by the adjacent Arab tribes, who realized they were bound to be involved in wars between Persia and Islam. The sheikh al-Muthanna, the ally of Khalid, in 635 won a victory on the Euphrates: ‛Umar had now succeeded abu-Bakr as caliph, but Islam was still governed by Medina: and of Medina, and even of Islam, al-Muthanna knew little. ‛Umar sent one of the companies of the Prophet to bring reinforcements against the Persians and to take over the command. The Persian leader Rustam was out-generalled at Qadisiya, near al-Hirah, in 637, and Persia was won by the Arabs, both the highly civilized Iraq, at the head of the Persian Gulf, and, later, the wilder, hill-country of Iran, which stretched from the lower Euphrates across to the Indus.

The Arab victory at Qadisiya was followed the same summer by their triumphal entry into Ctesiphon. The greatest royal city in Asia, the luxuries, comfort and art of a high civilization, lay at their disposal, though, according to Arabic chroniclers, they scarcely knew camphor from salt or gold from silver. The Arab general, Sa’d, built a fine mosque in Ctesiphon; but the caliph ordered the capital to be moved to al-Kufa, as nearer to al-Hirah and less dangerously distant from Mecca. Al-Kufa and Basra became the garrison cities of Iraq and the east.

Byzantine Armenia was raided in 640 by ‛Iyad: but the country was difficult, and not subdued till 652. This new province too was to be placed under al-Kufa, and although ’‛Umar urged a Meccan simplicity of life on the Arab rulers, the sophistication of Persia was too attractive, and a royal palace was built there like the old palace at Ctesiphon. Al-Kufa and Basra remained the great desert cities of eastern Islam, till the Abbasid Mansur built his famous capital at Baghdad. From Basra in the reign of the caliph Mu‛awiya the conquest of eastern Khurasan was completed (663–671); the Islamic forces crossed the Oxus and raided Bukhara in distant Turkestan.

The conquest of Egypt was made by planned campaigning rather than, as in the case of Syria, Persia and Armenia, by casual raids. But even here, the caliph ‛Umar gave only a limited authorization, and the victory was due to the Arab leader ‛Amr, who had traded with Egypt in the days of the Jahiliyah, knew the country, and was eager to eclipse the exploits of Khalid. He had already conquered Palestine west of the Jordan: he took the old coast road through Pelusium at the mouth of the Nile, and he defeated Heraclius’ general Theodorus, with a much larger force, in the strong castle of Babylon (just south of Cairo); a seven months’ siege ended victoriously in 641. Alexandria, that great city, still rested untaken on the westward extremity of the Delta: it was defended by a strong garrison and the Byzantine navy: the Arabs were unused to the catapults hurling stones from the walls, and they looked on Alexandria and retreated. But there was division in Constantinople on Heraclius’ death in 641, and Cyrus, patriarch of Alexandria and imperial vicegerent of Egypt, concluded a treaty with ‛Amr at Babylon, by which Egypt became tributary to the Arabs as the price of the evacuation of the country by ‛Amr’s army. ‛Umar received the news, and thanksgivings were said in the Prophet’s mosque at Medina. The site of ‛Amr’s camp outside Babylon became the new Arab capital of Egypt, called al-Fustat (Old Cairo), and it remained the capital till the Fatimid caliphs built their new capital, Cairo, in 969. From al-Fustat the ancient canal leading through Heliopolis to al-Qulzum on the Red Sea was cleared by ‛Amr, and a direct waterway was opened to the Arab cities on the Red Sea. On the whole, the old Byzantine system of administration was retained. The easiness of the conquest of the Delta is explained by the willingness of the Coptic peasants, as Monophysites, to receive the enemies of Heraclius, under whom they had suffered religious persecution and financial oppression. As in Syria and other conquered regions, new converts began to throng to Islam. So clearly had their conquerors identified Islam with the Arabs, that at first they could only enter the faith by becoming mawali or clients of one or other of the Arab tribes. They thus became entitled to exemption from most of the taxes imposed upon the conquered, and to most of the material benefits of Islam. They did not, in fact, always obtain the exemptions to which they were entitled.

The Byzantines had not, however, relinquished hope of regaining Egypt, especially as Arab tax collectors roused some resentment. The emperor Constans II sent an expedition which retook Alexandria in 645, and ‛Amr, who had been recalled by the caliph, was sent back to defend Egypt. In 646 he retook Alexandria, demolished her walls and secured her for Islam. ‛Uthman (Othman) the caliph seems to have had no desire to press the conquest along the coast to Tripoli: but to the early, devout Muslims the principle of the jihad, the holy war, was ever pressing, and ‛Amr was a good soldier. With Mu‛awiya, the governor of Muslim Syria, he began the establishment of a Muslim fleet, using the captured Greek ships and the great dockyards of Alexandria; with a fleet, advance along the north coast, largely waterless, was more possible.

The first Arab naval operations were carried out in the same years as the conquest of Tripoli. Mu‛awiya’s fleet seized Cyprus in 649, and in 652 the Egyptian Arabs defeated a larger Greek fleet off Alexandria. In 654 the Syrian fleet pillaged Rhodes, and in 655 the Syro-Egyptian fleet destroyed some 500 Byzantine ships near Phoenix, off the Lycian coast: Constans II had led the fight in person, and he lost, with his ships, the naval supremacy of the east Mediterranean. The two Arab generals, Mu’awiya of Syria and Abdullah of Egypt, had proved themselves outstanding sea-captains, and the Arab word amir acquired in the west its sense of admiral. Nevertheless, the early caliphs distrusted this alien method of warfare, and both ‛Umar and ‛Uthman sent messages to their admirals, emphasizing the need of camping where the caliph’s messenger, or the caliph himself, could reach them riding the preferred horse or camel. But the fall of Egypt and the existence of an Arab fleet had rendered the Byzantine province of Tripoli and the great headland of Cyrenaica defenceless; ‛Amr indeed had pushed his raids right along the coast to Barca in Cyrenaica in 643. The Berber tribes of Tripoli submitted; for the time being.

The caliph ‛Umar died in 644, murdered by a Persian slave. He had appointed on his deathbed an electoral college or shura, which had elected ‛Uthman caliph, deferring to the wishes of the old leading families of Mecca. The choice was unfortunate, for ‛Uthman was weak, incompetent and a nepotist. The impetus of Arab conquest was stayed, partly through weak leadership, partly through the old nomad objection to central government, and largely also because the pressure of population from Arabia had found sufficient outlet.

The limits of conquest in Africa were, however, not yet fixed. ‛Umar had refused permission for advance beyond Tripoli, as adventure further to the west seemed more dangerous than profitable. But the double incentive of loot and the holy war seemed to demand a fresh field among the Berbers to the west, and ‛Uthman took counsel of the Companions of Muhammad and gave his permission. To the Arabs, Africa, shadowed by trees, as their chroniclers wrote, from Tripoli to Tangier, seemed a rich land: and the olive trees were indeed a source of wealth as much as of shade. They raided Carthage, beyond the great gulf, and called the land round it Ifriqiya (Africa). They plundered the province of its treasure, sending sacks of it along the road to Medina and Damascus: they wondered at the great number of horses, more than they had themselves in Arabia; at the camels, at the stores of silver and plate: and above all at the beautiful slave girls, whom they sent to be sold in eastern markets for as much as 1,000 pieces of gold apiece. Some were bought for the harems of Muslim chieftains, and half Byzantine, half native as they were, became the mothers of Arab nobles.

Nevertheless, the Berbers proved more easy to defeat than to conquer. They had a perpetual reservoir of undefeated tribesmen to the south in the Sahara, and whereas the conquests of Spain took three years, Egypt three, and that of Palestine and Syria only seven, it took fifty-three years to make a precarious conquest of these north-west African tribes. Distances were great: other provinces mattered more than Africa: the Berbers fighting a guerrilla war could withdraw into the desert, and since they had never been conquered by Rome or Byzantium submitted the less readily to the Arabs. It took 150 years before the conquest was complete.

To consolidate the military conquest and facilitate its further development, the Arab leader Sidi ‛Uqba founded Qairawan, south of Tunis and Carthage, to be not only a military post, but a teaching centre to conciliate the Berbers and convert them to Islam. After pressing his conquest to the Atlantic, he was finally killed by a Berber chief, who took Qairawan and remained its master from 683 to 686. In these three years, the old Vandal and Byzantine province saw its last good days, ruled by an African Jugurtha; Constantine IV meanwhile kept the Muslim armies in check, and his garrisons held the coast from Sousse to Bona. But after a seven-year halt by the Arabs, they advanced under Hassan and regained Carthage in 695, only to be swept from it by a flood of Berbers led by an African Boadicea, a Jewish priestess called Kahina. In 698, they took Carthage for the third time, and this time permanently. Their rule continued uneasy, but two factors helped them: the Islamization of the Berbers, not too difficult a task, and the enlisting of Berbers to fight in the armies that conquered Spain.

What accounted for the complete dechristianization of north Africa, the old province of Cyprian and Augustine? For one thing, Romanization had never been complete and between the old Roman towns and villas the Berbers had remained pagan and animist. Judaism indeed had penetrated farther than Christianity. Africa, it is true, had had a large number of bishops’ sees, but this fragmentation of authority had favoured local heresy and disunity. Under the Byzantines religious division had risen again: the struggle over Monothelitism disturbed the province at the very moment of the Arab invasions. Moreover, Arab generals, when engaging an enemy, offered as alternatives to fighting conversion to Islam, or a not intolerable tributary status without conversion. Those who thus surrendered might not only keep their religion, but practise their trade or their art (especially medicine), and even hold public office. Severity was only shown to those who treated Islamic rites with disrespect, or lapsed after accepting Islam: the conquered Berbers and provincials might live under a régime of tutelage and tariffs. In all but the fringes of the desert, where the Berber dialects finally prevailed, Arabic superseded Latin and Greek as the language of government and everyday life.

But while the conquest of the Maghreb proceeded, the unity of Islam under a single caliph was lost. The tribal leaders who conquered first Arabia and then Syria and Persia were led by the Companions of Muhammad and had been long trained by him in the stern, simple tenets of early Islam. The close followers of Muhammad at Mecca accepted with passionate fervour the exclusive character of the message of God to Muhammad, and its complete sufficiency. All revelation, all moral teaching, all learning, was completely covered by the Qur’an. But when, by the will of Allah, Syria and Persia had been conquered, with their unheard-of fertility, wealth, buildings, art treasures and learning, the question whether all this richness and knowledge ought to be rejected by the good Muslim was bound to arise. The interests of Syria, of Iraq, even of lesser Arab-ruled dependencies, were bound to conflict, not only with the political dominance of the Meccan party, but with the stricter Muslim attitude towards external luxury, learning and craftsmanship. The personal rivalries of Arab generals after the murder of ‛Uthman appeared to divide the caliphate: but provincial interests and religious differences accompanied them.

The question whether succession to the caliphate should be limited to the descendants of the Prophet, or go by election to any pious and suitable Muslim, had been raised even in the time of the first four (elective) caliphs. ‛Ali had been Muhammad’s first cousin, the husband of his daughter Fatima, and the father of Muhammad’s only two surviving descendants; there were those who claimed he should have succeeded Muhammad in 632, instead of giving way to men of greater seniority. ‛Ali disposed of rival claimants, except Mu‛awiya the Umayyad, the governor of Syria, who led an army against him; but, disliking the mutual shedding of blood by Muslims, he agreed to arbitration of his own and Mu‛awiya’s claims. The verdict deposed both men from their offices, a verdict pressing the more heavily on ‛Ali. When he was later murdered, the party of the Shi’a, who stood for the rule of Muhammad’s descendants, became his partisans, regarded him as a martyr, and refused to accept as binding any teaching except that given by him whom they regarded as the true imam, necessarily a descendant of ‛Ali, and of greater importance than the caliph himself. The Shi’ites were always a suppressed minority in Islam, and the raisers of numerous rebellions: but the Fatimid dynasty in Egypt was Shi’ite later. Both Umayyad and Abbasid caliphates were Sunnite.

Mu‛awiya, the founder of the Umayyad dynasty, relied chiefly on the Arab army in Syria, and the Syrian Christians in the bureaucracy, with whom he was not unpopular; his extension of the Islamite dominions made him regarded as second founder of the caliphate, as well as of a dynasty. Under the Umayyads, however, some of the old Meccan exclusiveness still lingered, and it was left to the Abbasid dynasty (750–850) to abandon the original austerity of Islamic life, and become the patrons of alien learning. Abbasid administration deliberately copied Sassanid practice, and was no longer based on racial exclusiveness. The mawali, long full of economic and social discontent, were employed in the ministries and could enjoy high social standing: the change from the Umayyads to the Abbasids meant social revolution. Though the Umayyad caliphate itself had been ‘not so much an Arab state as a Persian and Byzantine succession state’, with the Abbasids the reliance on Greco-Persian practice and imitation of Greco-Persian absolute sovereignty increased.

The first Abbasid century, beginning with the caliphate of Abu’l-‛Abbas (750–754) is reckoned the most splendid in Arab history. The seat of power was now in Iraq, and the ruling circle no longer Arab, but much more international. To preserve Islamic unity, however, the religious aspect of the caliphate was emphasized, in contrast to its secular character under the Umayyads. Government was theocratic and propaganda taught that authority should remain for ever in Abbasid hands. Their government proved as shrewd and worldly as that of the Umayyads. ‘The Abbasid was an empire of Neo-Moslems in which the Arabs formed only one of the many component races’ (Hitti).

Mansur (‘the Victorious’), who ruled from 754 to 775, proved one of the greatest of the Abbasids; all the thirty-five caliphs who succeeded him were his lineal descendants. He contended successfully with insurrection in Syria, in Khurasan, and by the ‛Alid Shi’ites, but he could not subdue or displace the Umayyad amir, ‛Abd ar-Rahman, in Spain. The latter was one of the very few Umayyads who had escaped in the general massacre ordered in 750 at the accession of the Abbasids; he had wandered as a fugitive for five years through Syria and Africa, joined by Umayyad partisans, and captured Cordoba in 756. From this year, Islam was divided politically between the Abbasid at Baghdad and the Umayyad at Cordoba, though the Umayyads used at first only the title of amir: Islam was divided also in religion between Sunnites and Shi’ites. The Umayyad amirate (later caliphate) at Cordoba was to last from 756 to 1071: it was Charlemagne’s alliance with the Abbasids (though this is disputed), and some invitation to intervene against the Umayyad ruler at Cordoba by certain Arab rebels in north Spain, that prompted his march in 778 through the northern route to Saragossa. (See p. 351.)

But though in Mansur’s day it was scarcely possible to hold in one state Spain and the middle east, at least under a single political rule, yet in Syria, Iraq, Persia, Armenia and Khurasan, Islamic rule was glorious. Mansur laid the foundations of his new capital at Baghdad, which he called Dar-al-Salam (abode of peace), in 762. He chose as the site a small Sassanid town just north of Ctesiphon, where the Tigris and Euphrates swing in together nearly to meet, before diverging again in the great oval above their junction at Basra and the river mouth. ‘Here’, said Mansur, ‘is the Tigris, to put us in touch with China and with Mesopotamia, Armenia and their environs.’ Here too was the Euphrates, to carry for Mansur all that Iraq, Syria and the adjacent lands could offer; and here, nearby, were the ruins of Ctesiphon, from which he drew his building material. He took four years to build his new city, using vast sums of money, and some 100,000 architects, craftsmen and labourers drawn from Syria, Mesopotamia and the more distant provinces. He built a great Greco-Roman-Persian city, second only to Constantinople in its day, circular in plan, the walls pierced by four equidistant gates. Within, the roads radiated from the caliphal palace and the great, domed mosque in the centre, through the four gates, to the four corners of the empire. From this capital, famous as the city of the Thousand and One Nights, the Abbasid caliphs built up the government on the Sassanid model in the time of Chosroes. Persian titles and offices (such as the vizirate), Persian songs, Persian astronomy and Persian learning were adopted; Mansur himself adopted Persian headgear. In all the arts and amenities of life, Persian custom was adopted: but the Arab stamp was given to the new state by the religion of Islam and the retention of Arabic as the official language.

In Baghdad, Damascus, Quairawan, Cordoba and a hundred Islamic cities and villages, the wealth of caliphs and amirs spent itself in the building of palaces, baths, schools, hospitals, caravanserais and the characteristic mosques and minarets. The ground plan of the Roman villa, with its colonnades and fountain, and the Christian basilica with its roof supported on pillars and its external court, were taken over, and the domed roofing of Mesopotamia. Greco-Roman mosaics supplied a technique, though their mythological figure subjects could not be used by Muslim art, which not only discountenanced a representation of what purported to be other gods than Allah, but even all representations of the human figure and a naturalistic treatment of visible objects. The old Persian use of rhythmical pattern as distinguished from naturalistic ornament supplied to the Arabs a decoration accordant with their disallowance of ‘images’, and became in Arab usage the scrolls and undulant patterns known to us as ‘arabesques’. Put very briefly, the points which, arising from her origins, distinguished Islamic art and architecture include:

The mosque, which might be a simple rectangular cella, or polygonal building dome-centred like the so-called mosque of ‛Umar at Jerusalem, with the mihrab or niche, generally arched and decorated, showing the faithful the direction of Mecca.

The minaret, from which the faithful were called to prayer. This was in essence a slender tower, varying in form in the different provinces of Islam, from the ziggurat of ancient Babylon, with its ascending spiral external stairway, to the tower of stages of decreasing size from north Africa, the round pillar, decorated and domed, from Persia, the galleried Indian turret and the tall, pointed flèche with its single gallery, from Constantinople.

In the buildings, the use of the horse-shoe arch, especially in Spain; and, especially in eastern Islam, the slightly bulging domed roof. It was used both in the mosque and the madrasa (lecture hall of the theological seminaries). In both the large domes of centrally-focussed buildings, and the small domes of turrets and minarets, these double curved roofs, with the widest part of the dome pro jecting beyond the supporting walls, needed mathematical knowledge for the supporting scaffolding, and in some cases a roofing by sheets of metal. Whereas in Europe roofing with lead was costly, in this style, born in Asia and on the caravan route to India, roofing with sheets of shining copper even was made possible by the relative plenty of the metals and the riches of Arab princes.

The use of colour in architecture, not only in mosaics and tiles, but in the contrasting colour blocks for arches (as in the mosque at Cordoba) is another feature; as is the use of rich and intricate allover patterns for the covering of large surfaces, like the tomb of the amir Suleiman at Cairo. The use of the allover pattern is itself characteristic of Islamic art: it has neither axial symmetry, like the palmette ornament of the Greeks, nor a central focus, like the spirals of the Celts; it achieved unit and beauty by the balanced repetition of geometrical motifs. Possibly the Persian, Indian and Arab fondness for the allover pattern goes back to its uses in the splendid textiles of the east.

A very characteristic feature of Islamic art is the use of Arabic writing as a form of decoration, whether in buildings, or for textiles, metal work or pottery. The beautiful Arabic script, with its aligned letters of varying height and thickness, formed an admirable banded ornament: while even a few letters could be combined in a pleasant decoration and applied again and again. In the later Islamic mosques and madrasa’s, bands of Kufic writing ran in a continuous ornament just where the walls passed into the spring of the dome chamber, binding together walls and dome. In the Fati-mid period similar bands of writing were used on the external façade of the great mosque in Cairo. Within the mosques, Arabic writing of the word of Allah adorned the mihrab, which was sometimes faced with lustre tiles: the unalterable word of Allah stood out in flat, dark blue against the shining tile (see Farris, Heritage). A heavy band of lettering often formed the sole and sufficient ornament to the glazed pottery plates and was inlaid on the bronze vessels.

Another feature of Islamic art springs from its association with the desert. The object ornamented must be such as could be carried on horse or camel back; jewellery and fine metal plate found no place in early Meccan life, and were forbidden to the good Muslim. The craftsman therefore expended his skill on pottery and textiles. The use of very fine design for the adornment of a coarse material is characteristic of Islamic art. In spite of the early Islamic disapproval of luxury and rich materials, however, fine craftsmanship and beautiful design were soon shown in Islamic metal-work and carvings in wood, ivory, rock-crystal, etc.

Eventually the most important contribution of Islam to European civilization was her transmission of Greek and Indian learning, particularly that of the ‘Arabic’ (early Indian) numerals, which are the basis of all modern calculation. Islam at Baghdad under the Abbasids was a clearing house for Greek, Persian, Syrian, Chaldean and Indian learning, and Arabic the medium of translation of the works of scholars of all these earlier civilizations. In the realm of thought Islam was a carrier, a transmitter, as much as in the realm of trade or art. She used the logic and the science of Aristotle, she gave Europe the numerals of India; and she gave her the Chaldean notions of magic and astrology. If Shakespeare wrote: ‘It is the stars, the stars above us, govern our conditions’ the Arabs taught him so.

As to the Arab transmission of Greek learning: it was there awaiting them in the kingdom of the Sassanids. In Justinian’s reign, an interest in natural science had flowered again in medicine and mathematics; Aetios of Amida, Paulus of Aegina and Alexander of Tralles investigated too the principles of conies and built ingenious machinery. Alexandria was a centre of Greek culture, and Byzantium now and later had commentators on Aristotle who, in their own line, surpassed the learning of Isidore, Bede or Scotus Erigena in western Europe. Greek learning in Persia met the alien cultures of Persia, Syria and India; the Ptolemaic concept of the universe met the tradition of Babylonian star-worship at Harran, and with it, probably, Babylonian mathematics and astronomy. Harran was the stronghold of the heathen Syrians, and so continued till the thirteenth century: it was also a stronghold of Hellenism and mathematics.

Greek knowledge spread to Mesopotamia and Persia in the fifth century in the wake of religious controversy. The Nestorians were expelled from Constantinople in 431 and fled to Edessa. The now famous schools of Edessa were closed by Zeno in 489, and the Nestorians then migrated to Nisibis in Mesopotamia, and, in the early sixth century, to the Persian medical schools of Jundi-Shapur. Syriac, a Semitic tongue, had long been a literary language, and from the sixth century translations made from Greek treatises passed from Jundi-Shapur into Persia.

When the Umayyad caliphs ruled Persia (661–750), Islam was still intolerant and suspicious of foreign thought: but the Abbasids at Baghdad, especially Mansur and Harun ar-Rashid, and above all Ma’mun, encouraged a revival of learning and its absorption by Arab scholars. During the years 750–850 the works of Greek authors were found and translated through the agency of Nestorian and Monophysite Christians in Iraq. The works of Galen, Aristotle and Porphyry were already translated into Syriac, and at the schools of Jundi-Shapur three cultures had already met: Jewish-Persian, Syriac-Greek, and Indian. The Monophysite bishop, Georgios, had already translated Aristotle’s logical works before 724; Severos Sebokht of Nisibis translated the Analytics and wrote on geometry, arithmetic and astronomy; he had already encountered Indian numerals, and helped transfer to the Arabs some knowledge of both Indian and Greek mathematics.

It was the Abbasids, however, who ordered and paid for the methodical collection of Greek and Syrian manuscripts and their translation into Arabic. Mansur invited Nestorian physicians to Baghdad, encouraged them to live there, and to teach and train students; he was the patron of those who translated philosophical and scientific works from Greek, Syriac and Persian into Arabic. But the work of translation was even further encouraged by the caliph Ma’mun (d. 833). Amongst the scholars he collected was the Nestorian Syrian druggist, Hunain bin Isha (809–877), Latinized as Johannitius, who had studied medicine at Jundi-Shapur, learned Greek, learned Arabic at the schools of Basra, learned Persian, entered the service of the physician to the caliph, and finally become superintendent to the great library, collection of manuscripts and school, known as the ‘House of Wisdom’. With a staff of translators, he translated great numbers of Syriac, Greek and other manuscripts into Arabic.

The whole work of translation and the dissemination of learning under the Abbasids, as indeed their centralized administration dependent on written orders, was made possible by the new use of paper. This was a much cheaper writing material than parchment, and tougher and more lasting than the old papyrus. Paper was apparently first made in China in the first century B.C. In A.D. 751 the Arabs won a victory over some Chinese forces east of the Sir Darya, on the slopes of the Tien Shan mountains, and captured some Chinese paper makers; under Harun ar-Rashid the craft of paper making was introduced into Iraq and spread rapidly through the Islamic world (Bernard Lewis). By the tenth century, paper was made in Iraq, Syria, Egypt, Arabia, Morocco and, rather later, even at Valencia in Spain: the raw material (rag) was not limited, as with papyrus, to the Nile valley.

Perhaps most notable in the content of Abbasid learning were the mathematical disciplines, absorbed through translations from India and the Far East. Greco-Roman learning had dealt with ‘number’ (see p. 87), but without the zero: and with space by means of Euclidean geometry. Indian and Chinese mathematics had meanwhile evolved a system of numerals using the zero, and a science of measurement alternative to geometry in ‘algebra’. The first Arabic knowledge of these disciplines seems to have come when an unknown Hindu astronomer came to Baghdad in 772, and brought with him two treatises on mathematics and astronomy. That on astronomy was the early Hindu treatise, the Siddhanta, and it was translated by the Persian scholar al-Fazari (d. c. 777) under the Arabic title Sindhind. The treatise was of twofold importance, for it became fundamental to Arab astronomy, and it introduced the Hindu numerals into Arabic: later, they became known in the west as ‘Arabic numerals’. To a Europe using only the Roman numerals, with which simple addition, subtraction, multiplication and division were impossible by written reckoning, the Arabic-Indian use of nine numerals and the zero made possible a revolution in mathematics. Al-Fazari moreover was the first Muslim to construct an astrolabe on the Greek model: both sciences were known to him. The actual transmission of the Arabic-Indian numerals to the west was made through the works of al-Khwarizmi (d. c. 850), whose name became in the west the word ‘algorism’; the Arabic title of his treatise (meaning Restoration and Equation and beginning al-jabr) gave us the word algebra. This treatise, more than any other Arabic book on mathematics, influenced western thought, though tardily; it was translated by the Englishman, Robert of Chester c. 1140, and it was used by Leonardo of Pisa (d. c. 1240) and Master Jacob of Florence; the latter’s Italian treatise, of 1307, comprises the six types of quadratic equations used by Muslim scholars.

The length of time which elapsed before Arabic numerals reached the west, and the length of time after that before they came into common use, is remarkable. Leonardo Fibonacci in 1202 published in Italy the first book to use the symbols; he had had an Arab master and travelled in north Africa. Italy had Arab colonies in the south in Frederick II’s time, and it is not surprising that the numerals should have first obtained a limited use there; they were never in general use in western Europe throughout the middle ages. It should be remembered, however, that Arabic is a difficult language, and Arabs more difficult for Latin scholars to procure as teachers than Jews or Syrians, from whom they could learn Hebrew or Greek; and further, that accounting in western Europe was not merely a matter of book-keeping among the instructed, but of demonstration to the illiterate. The English exchequer table was an abacus to demonstrate to illiterate sheriffs what they owed the king; the notched tally demonstrated at Michaelmas how much they still owed from the earlier session. Even today, the baker in southern France splits a wooden tally with his customer, and putting the two together, his customer watching, makes a cut for every loaf he delivers: there can be no dispute. Similarly, in the middle ages where there was so great a gap between the scholar and the illiterate mass of the population, the adoption of Arabic numerals was incredibly slow, because it lacked the spur of wide, general usefulness. Every accounting was a process of demonstration; the manorial steward, when owed wagon-loads of hay or grain for his lord’s court yard, cut notches in a gate post as they were delivered; and royal officials used the abacus, the casting counter and the tally. Meanwhile, in medieval libraries, as evidenced by surviving catalogues, books on algorisms were relatively infrequent and rested beside treatises on hermeneutics, or magic; the position of both pointed to their Arab provenance, for algorism, algebra, astronomy and the science of horoscopes were subjects one and all transmitted in Arabic from Jundi-Shapur, Baghdad and Harran.

As to the Arabs’ concept of the physical universe: they absorbed Greek philosophy, embracing as it did a Ptolemaic universe, and an Aristotelianism coloured by the Neoplatonic ideas current in Syria and Persia. One school of Muslim thought accepted, between the one God and the human soul, a ladder of cosmic intelligences inhabiting each of the heavenly spheres down to the lowest, the sphere of the moon. In this lowest sphere there dwelt the one active intellect common to all individual souls, which share in it: with this intellect it is possible to attain a mystical union. It is remarkable that, when the Arab-translated treatises of Aristotle came back to Europe, scholars such as Albertus Magnus and Aquinas should have discarded these Arabic additions and come near to the thought of Aristotle himself.

Arab alchemy similarly was founded on the Aristotelian theory of the elementary composition of matter, and other Greek chemical ideas, but was much coloured by Neoplatonic notions of ‘emanation’. There seems to have been a secret sect of natural philosophers or alchemists, who took the title of ‘Brethren of Purity’; the first considerable writer on the subject was a somewhat legendary figure, reputed to be a pupil of the Shi’ite imam, Jabir ibn-Hayyan (d. 760). Arab alchemy too penetrated to the west.

It may be convenient to recapitulate here the chief landmarks in the astonishing rise and conquests of Islam.

622 July 16 |

The Hijra, or flight of Muhammad from Mecca to Yathrib or Medina. |

632 |

The death of Muhammad, and the succession of ABU-BAKR as his caliph, or deputy: he ruled at first only the Hijaz, or coastal strip of Arabia by the Red Sea, including Mecca and Medina. But he conquered Arabia, al-Hirah and Palestine. |

634 |

The caliphate of ‛UMAR who conquered Persia, |

635 |

conquered Damascus, |

636 |

defeated the Byzantines at Yarmuk |

637—8 |

gained Jerusalem, Aleppo, Antioch, Caesarea and all Syria by 640. |

639—42 |

The Arabs conquered Egypt and Alexandria. |

644 |

‛UTHMAN succeeded ‛Umar: By 650, the Arabs had gained Tripoli: north Africa to the great, waterless gulf of the Syrtes (a notable barrier even in the last war: this was only passed when the Arabs acquired a great fleet). |

650 |

The Arabs occupied Cyprus and reached Crete. |

656 |

‛ALI became fourth caliph: first ruled from Medina, then Kufa: was murdered in 661; was the last of the four ‘orthodox’ or elective caliphs. |

661 |

MU‛AWIYA founded the UMAYYAD, the second, and hereditary caliphate: the importance of the northern conquests had made Medina no longer suitable as a capital: Kufa in Iraq and Damascus in Syria were rivals as sites of the capital; Mu‛awiya was proclaimed caliph at Jerusalem, but adopted Damascus as his capital, where the Umayyads ruled till 750. |

670 |

The Arabs appeared before Constantinople: threatened it intermittently: departed in 677. In Africa, Sidi ‛Uqba conquered the Berbers beyond the Syrtes, founded Qairawan (south of Tunis and Carthage), traversed north Africa and rode his horse into the waters of the Atlantic; the Berbers proved hard to subdue. |

695 |

The Arabs took Carthage. |

711 |

The battle of Jerez de la Frontera and Arab conquest of Spain. (Spain and north-west Africa, the Maghreb, were now ruled nominally from Qairawan and were ultimately under the caliph: but Spanish sub-rulers at Cordoba were almost independent.) |

717 |

The last Arab attempt on Constantinople failed. |

732 |

The battle of Tours: the Franks ended the advance of Islam in Europe. |

750 |

The Umayyad caliphate at Damascus was succeeded by the Abbasid (750–1258), which transferred the capital to Baghdad in 762. Meanwhile, in Qairawan, a usurper, ‛Abd ar-Rahman, made himself practically independent of the last Umayyad caliph, and another ‛Abd ar-Rahman, fighting in Spain, became the founder of the western caliphate. |

909 |

The Fatimid caliphate founded in Tunisia. |

In assessing the importance of the Arab conquests of the seventh century for modern life, it should not be forgotten that the Arab contribution to mathematical science and the Arab transmissions of the culture of old Persia to Europe were balanced by certain losses. In the Hellenistic east, Greco-Roman culture was permanently eclipsed; in Palestine and Syria ‘churches were replaced by mosques, and Greek gave way to Arabic as the lingua franca of the caliph’s dominions’ (W. H. C. Frend). More important still, north Africa in the eighth century was gradually converted from ‘a mainly agricultural and Latin-speaking territory to a desert corridor binding Cairo with Cordoba, dominated by Muslim nomads’. Islam sprang from the desert, and in Africa showed herself as ready to control and perpetuate desert life as to change it.

BIBLIOGRAPHICAL NOTE

For an excellent short account of Islam, see B. Lewis’s The Arabs in History, 1950; for the standard, fuller, account (with descriptions of Arab science and institutions, as well as the political history), P. K. Hitti, History of the Arabs, 1949, and the shorter Mohammedanism by H. A. R. Gibb, in the H.U.L. A set of illuminating essays by different Arabic scholars, edited by N. A. Faris, called The Arab Heritage, was published in 1946 by the Princeton Univ. Press. See also G. E. von Grünebaum, Medieval Islam, Chicago Univ. Press, 1945; G. Marçais’ La Berberie Musulmane et l’orient au moyen âge, 1946; De L. O’Leary’s How Greek Science passed to the Arabs, 1949; A. Mieli’s La science Arabe, 1939; F. Sherwood Taylor’s ‘The Moslem Carriers’, in The Root of Europe, ed. M. Huxley, p. 44; H. I. Bell, Egypt from Alexander the Great to the Arab Conquest, 1948.