CHAPTER XV

THE LATER MEROVINGIANS

THE character of the period 561 to 768 (dealt with in this chapter and that following), is one of violence. From the death of Lothar I in 561 till the accession of Charles the Great in 768 there were struggles, not only between the Frankish kingdoms, but between the Frankish kings and their households, their ‘palaces’. The two centuries were marked not only by wars and violence, but by a decline of the Latin tradition in Gaul, of the relatively civilized south of Gaul as against the barbarian, Germanic, north. The regnum Francorum in the days of Clovis and his sons had a real unity; afterwards, the kingdoms of Austrasia, Neustria and that successor-state to Burgundy that included part of Aquitaine, tended to become more and more independent, following the interests of their rulers.

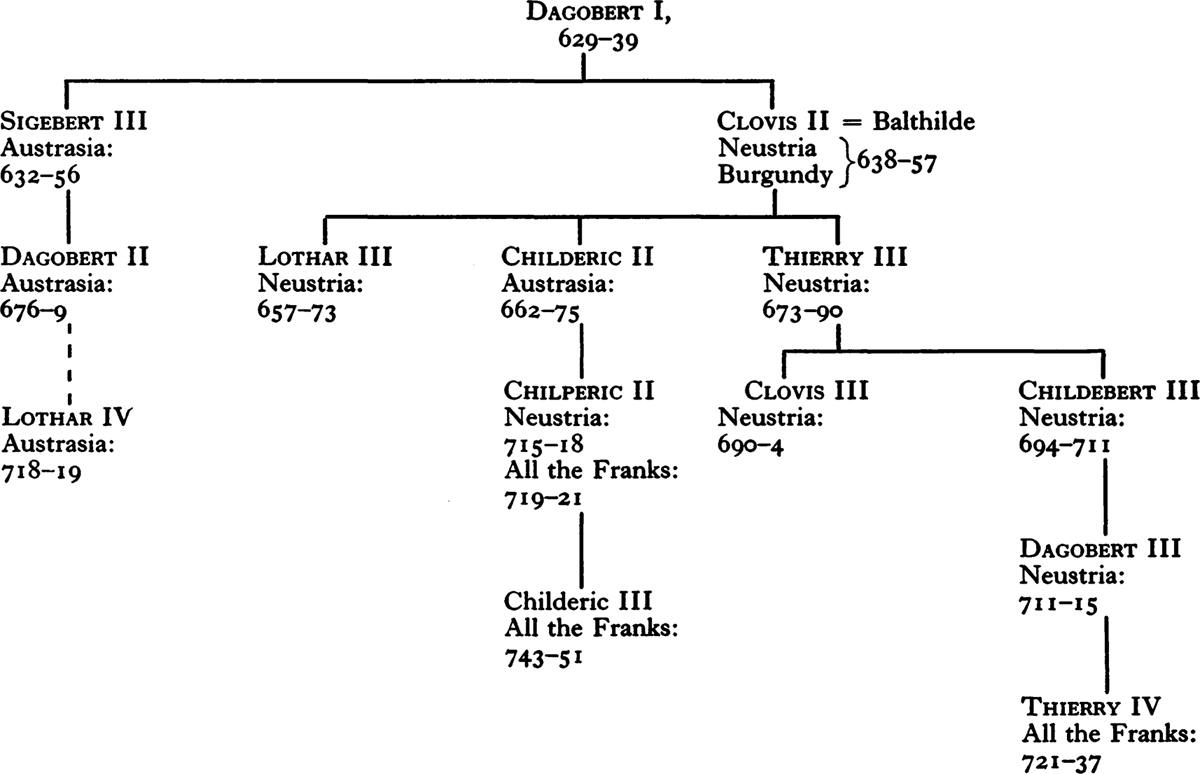

The chronological divisions of the period 561–768 run from the death of Lothar I to that of Dagobert in 639, while the Merovingians still ruled France; from 639 to 719, when the Frankish nobility, headed by the mayors of the palace, struggled for the dominance of their respective kingdoms within the regnum Francorum, under the cover of nominal Merovingian rule; and from 719 to 768, the period of the growing dominance of Austrasia and her mayors of the palace. From the family of the Arnulfings, descendants of bishop Arnulf of Metz, sprang the Austrasian mayors, Pepin II and Pepin III, and the Carolingian dynasty.

About the curious retrogression in culture and political unity that followed the period of the Frankish conquests, some points may be noted. The first unity of the regnum Francorum was due to the personal energy, ability and fighting force of Clovis. He had been no more than the tribal king, the war-leader, of the Salian Franks, and his conquest of the Gallo-Romans had been no more remarkable than his defeat and removal of the other Germanic war-leaders, some of them at first his allies. He had been strong enough to make his residence, not in Tournai or the more Germanic part of his dominions, but in Paris among the Gallo-Romans, and to retain the rule of the north-eastern Franks none the less. The outlet of further conquests had preserved the country of the Franks from over-much internal strife during the lifetime of his sons. But when the natural limits of conquest were reached: when Frankish aggression was contained by the flowing tide of the Slav races then pouring into central Europe: the Lombards then securing themselves in Italy: the Spanish Visigoths, then with the Pyrenees to guard them: then the warlike energy of the Franks expended itself in civil war. There was no fund of political experience to guide a people now territorially settled; the Franks used certain Roman institutions, but they had no understanding of the value of centralized government. They did not, like the Arab conquerors of Persia, seek to understand and assume the culture they found in the land they conquered; perhaps because, in the north Frankish regions where they were in greatest strength, there was no Seleukia-Ctesiphon. Trier had been a great Roman city: Paris under the later empire had a cross-Channel trade: but neither was an Antioch or an Alexandria, and neither became a Frankish Baghdad.

The violence of the period again, the murder of political enemies and their wives and children, was perhaps no greater than that of the early Anglo-Saxons across the Channel: but we know more about it. Gildas, who died c. 570, in the Epistola attributed to him speaks about the violence of the tyrants in Britain and of two royal youths murdered on the altar steps: ‘They treat the holy altar as if it were a pile of dirty stones’: but we do not know who the royal youths were. We know very little of the fate of Britain after Arthur’s defeat in 537 (the Annales Cambriae say he died at Camlann in 537), except that Ceawlin of Wessex assumed the bret-waldaship and after him Æthelbert of Kent, in neither case, we may be sure, without violence. The Anglo-Saxon conquerors with their oral culture could not transmit their victories and defeats, their diplomatic marriages and their murders, except by the uncertain medium of heroic poetry. But over in Gaul, where men used the instrument of writing, there were clerks making entries in their annals, and a courageous and (for his day) learned bishop of Tours, well-informed in Merovingian politics, writing down in his history all that he knew of the deaths of bishops, of miracles (particularly those of St Martin), of the battles and the murders and the scandals: and he had much to write.

The disunity of the period was, again, partly due to the clash of local interests. The four kingdoms of Clovis’s sons became the three kingdoms of Neustria, Austrasia and Burgundy: Aquitaine was absorbed and divided in portions between these kingdoms. There was some real difference of culture and economic interest between the three, beside the personal rivalries of their kings; and the fact that there were thus three political centres, with the southern kingdom usually holding the balance between the two northern ones, prolonged the struggle for hegemony.

Finally, the violence and disunity of the period arose, more than from any other cause, from the failure of the Frankish rulers to regard their territories other than as patrimonies, to be divided at death among their sons, legitimate or even illegitimate. There was no sense of ‘the state’, or of the advisibility of racial cohesion or strategic frontiers or even economic needs in the subdivided patrimony: only of some balancing of assets one against another to each claimant of the inheritance. In the first division of the regnum Francorum at least the four sons were provided each with a compact territory or kingdom; but in later ones, three sons shared out Aquitaine and even the port of Marseilles; at another time Paris was divided between claimants. Boundaries fluctuated, and with them those of ecclesiastical provinces; sometimes, when a great city was divided, the king who did not obtain the portion with the bishop’s see set up a see for his own bishop in his own share. Not only was authority disastrously subdivided, but the inhabitants, e.g. of Aquitaine, adhered with enthusiasm to their Austrasian or Neustrian sovereigns, and fought amongst themselves.

Only the first part of the history of the period was written by an outstanding historian, namely Gregory of Tours (see p. 57): the last and very well-informed part of the Historia Francorum runs down to 591, three years before Gregory’s own death. From there onwards, we are dependent on the work of ‘Fredegar’ and the annalists, historical work of very little merit but composed under the handicap of the non-existence of a common scale of chronology.

Fredegar or Fredegarius Scholasticus was, in fact, an anonymous compilator, for no original manuscript mentions his name. The earliest manuscript of the works once ascribed to him, possibly to be dated as between 680 and 725, contains several treatises, all historical in character, including an epitome of the Historia Francorum, and a continuation bringing that history down to 768. The first portion of the continuation, from 593 to 642, is our sole source for the struggle connected with the rule of Brunhilde in Austrasia, and incorporates two complete chapters of Jonas’ life of Columbanus; after 642 three other writers continued the compilation. All these continuators after 642 belonged to the family or the entourage of Pepin I or his descendants, and hence their narrative is almost an official history of the rise of the Austrasian mayors of the palace.

The writing of ‘annals’ was at first a year-to-year business of entering episcopal, abbatial and other deaths, and other events of local interest, in an Easter table. In this pre-Carolingian period historical writing was not, apparently, carried much further among the Franks; but in the Carolingian age there was a great recopying and rewriting of annals by scholars of some merit and the outstanding series of annals, the Royal Annals, the annals of Lorsch, Reichenau and Corbie and the rest, were all reshaped annals of this kind. The Anglo-Saxon chronicle of 891 was a late and outstanding case of this method of writing history, drawing upon the history of Bede and, as is inferred from entries not drawn from Bede, from two or three early sets of annals. In the late Merovingian period, however, the annals were kept for a practical purpose, chiefly the information of bishops or abbots as to the keeping of the natalicia of the saints with mass and office: the relation of the annals to the calendars of the various churches must have been very close. Bede’s story of the use of a monastic annal in a Sussex monastery for ascertaining the saint’s day of St Oswald of Northumbria illustrates such primitive use of annals as must have existed in the Merovingian churches, after missionaries from England had spread the use of such annals to Gaul.

Bede, in this reference to a monastic annal, relates how, in the monastery of Selsey, during an outbreak of the plague, a boy already stricken with the disease was told by an angel to inform the priest Eappa that none except the boy himself should die. It was then only an hour after sunrise, and that day was the day on which Oswald had been slain in body by the heathen and taken in spirit to eternal joy: ‘Let them look’, said the angel, ‘in their books (in suis codicibus) in which is noted the burial of the dead, and they will find that this is the day on which he was taken from this world. Let them celebrate masses in all the oratories of the monastery, either in thanksgiving for the prayers now answered, or in memory of king Oswald.’ So the boy called for the priest Eappa to come to him and told him all the angel had said; and the priest believed the boy’s words, and he went at once and sought in his annal (in annale suo) and found that it was indeed the day on which Oswald had perished. Bede gives no date for this miracle at Selsey, but it must have been later than Wilfrid’s foundation of the monastery in 681.

The keeping of Christian annals belongs especially to the Merovingian period in Gaul, but it was part of the Roman inheritance. The origin of annals goes back much earlier, and helps to explain the efforts of these scribes of the dark ages to keep a historical record without a fixed chronology. The primitive form of Roman history was the official writing down of the Annales Maximi by the pontifex maximus, as described by Cicero. Each year a blank sheet (tabula), officially called an album, was set before the pontifex, and he wrote at the head of the entry for the year the names of the two consuls, and of the other magistrates: he then briefly entered memorable events as they occurred, during the year. Similar late Roman annals, with lists of consuls, prefects of the city, both for the east and the west, can be seen printed in the Monumenta Germaniae Historiae, in the ninth volume of the Auctorum Antiquissimorum; and there too can be seen lists of the Roman bishops, with the consuls for the year: Easter tables in Greek with the consuls of the year, Prosper of Aquitaine’s epitome of the Latin version of Eusebius’ kronikoi canones, going down to 433; Victor of Aquitaine’s Cursus Paschalis, a calendar for the dating of Easter worked out till the year 532 and resting on an Easter cycle of 84 years (see p. 175), and, finally, the Dionysian cycle. Such apparatus as this was, in whole or part, available to the Frankish annalists; but no use was at first made of Dionysius’ era of the incarnation.

The Merovingian annals thus belong to the same stage of historical writing as the history of Nennius in Celtic Britain: for general history, where the years of the abbot or bishop of the church were of no avail, only Prospers epitome and various chronological memoranda were at hand. Nennius copied (as part of the historical material which, he said, he had collected together in a heap), the genealogies of Welsh and Anglo-Saxon kings, and such aides-mémoire as a note that:

From the beginning of the world to Constantinus and Rufus are found to be five thousand six hundred and fifty-eight years, etc

Gregory of Tours, besides using the regnal years of kings and bishops, used similar epochs, writing at the end of his Historia Francorum:

From the beginning to the Flood, 2242 years: from the Flood to the crossing of the Red Sea, 1404: from the crossing of the Red Sea to the Resurrection, 1538: from the Resurrection to the transit of St Martin, 412: from the transit to the afore-mentioned year, the 21st of our ordination, the 5th of pope Gregory, the 31st of Guntram, the 19th of Childebert the younger, 197: altogether, 5792 years.

Such laborious synchronizing of years could not be avoided till a common scale was introduced. The Romans had dated by the indiction, a year’s place in a cycle of fifteen years: but knowledge of the consuls or some other historical landmark was needed to distinguish the cycle itself. The reckoning ab urbe condita was pagan and, in fact, a literary invention; the reckoning from the Creation (here used by Gregory) had no wide use. Eusebius and Jerome dated from the birth of Abraham; Prosper of Aquitaine dated his epitome in decades from the year of the Passion, and this reckoning was used in 457 by Victor of Aquitaine, who included it in his Easter table. In 525 Dionysius Exiguus (see p. 177) reckoned from the year of grace, the year of the Lord’s incarnation, inserting the annus Domini in his Easter tabula. The headings of his ruled columns, canones, ran thus:

Annus Domini. Indiction. Epact. Concurrents. Moon’s cycle: the 14th day of the Easter moon: date of Easter Sunday.

These Dionysian Easter tabulae were taken to England and circulated after the synod of Whitby, 664, and an occasional charter has been found dated by the era of the incarnation before the writing of Bede’s Ecclesiastica Historia in 731: but the popularization of this era was due to the circulation of Bede’s history, and, even more, of his De temporum ratione by Boniface and the Anglo-Saxon missionaries. The work included too a short world chronicle from the Creation to A.D. 729: it was to be the foundation of the Caroline writing of history, at Saint-Denis, Fulda, Corvey, Reichenau and the other great abbeys.

To run briefly through the political history of the period. When Lothar I died in 561, the more alien among his subjects were no longer dangerous. There were small, unimportant Saxon settlements round Boulogne and at the mouth of the Loire: the Saxons who accompanied the Lombards to Italy made one or two efforts to make fresh settlements in Gaul from Italy, but unsuccessfully. The Bretons were nominally subject to Clovis and his heirs: ecclesiastically, the see of Tours claimed rights over them. The Alemans and Thuringians had been subdued. The Boii of Bohemia had marched south to the eastern Alps and settled there as the Baiovari (people of Bohemia): Garibald, duke of Bavaria, had married a Frankish princess, and the Bavarians were subject to the Franks. The remnants of the Angli who had gone to Britain had been absorbed by the Thuringians, their name remaining in the place-name Engelheim. The Franks were by now the strongest Germanic people in Europe.

At Lothar’s death in 561, France was redivided. Charibert got Paris and west Gaul, the ‘newest’ conquests, the region to be Neustria; Sigebert, Thierry’s kingdom, the valleys of the Meuse and Rhine, to be Austrasia; Guntram, the old kingdom of Burgundy, with Aries as its episcopal city and Marseilles its valuable port; and Chilperic, Lothar’s son by another mother and not regarded by his brothers as legitimate, the least valuable share, the Salian lands round Soissons and Tournai. Gregory of Tours relates of this division that Chilperic tried to seize the whole, inheritance, laying hands upon Lothar’s treasure at Paris, but was not allowed to hold it long. His brothers forced it from him, and they made a ‘lawful division’ of the patrimony. Worse subdivision followed: for when Charibert died in 567, the three remaining brothers shared out his inheritance, dividing out Paris in three portions, giving to Chilperic, Normandy, Toulouse and Bordeaux, to Sigebert and Guntram shares of Aquitaine. Sigebert got Poitou and Touraine, Guntram Angoulême, Saintes and Perigueux. So unreasonable a territorial arrangement brought forty years fighting to Gaul.

To the territorial complication was added a deadly blood feud (faida) between Sigebert and Chilperic, and their descendants, involving as well nearly all the Frankish nobles and bishops on one side or other. Aquitaine had once belonged to Visigothic Spain, and two Frankish kings thought to safeguard their share of the southern lands by a Visigothic alliance. Sigebert married the young Visigothic princess Brunhilde, daughter of Athanagild: the poet Fortunatus sang the epithalamium at their wedding. Chilperic, jealous of his brother’s honourable marriage, for the Visigothic court was stately and Byzantine, and he himself aspired to the old Greco-Roman culture, married Galswintha, sister of Brunhilde, very splendidly at Reims, temporarily deserting his mistress Fredegund; he gave Galswintha a dowry of Aquitanian cities, including Bordeaux. He then returned to Fredegund; and when Galswintha asked to go back to Spain, she was found strangled on her bed. The court at Paris mourned her a few days only, and then Chilperic married Fredegund. Sigebert demanded compensation, and obtained the Aquitanian dowry of Galswintha: but Brunhilde saw her sister’s murder as unemendable, a botless crime, and she pursued the blood feud as a holy duty. Civil war between Neustria and Austrasia started in 573, and was almost uninterrupted for forty years, claiming many royal victims as the blood price. It created bitter hostility between the Franks of east and west, and it weakened the monarchy, which had to draw the leudes into the quarrel for their support, and to do it at the price of concessions and grants.

Chilperic started the war by attempting to seize his brother’s cities in Poitou and Touraine: but Sigebert called to his aid the barbarians from beyond the Rhine and a fresh ’barbarian invasion’ harried France; Chilperic had to give up his conquests. Again in 575, when Chilperic advanced on Reims, Sigebert called in his trans-Rhenane allies: he drove Chilperic back to Paris, seized the country between Seine and Loire, and was about to be raised on the shield as king by the inhabitants of Tournai, Chilperic’s capital, when two of the sons of Fredegund drove their long knives into his side (December 575). Chilperic regained the advantage; he got back Paris, where Brunhilde had been guarding Sigebert’s treasure, and sent her to Rouen. Duke Gundo-bald saved her five-year-old son from death at Chilperic’s hands, and the child was recognized as Austrasian king, Childebert II, at Metz, on Christmas Day, 575.

Brunhilde, still under thirty and held to be beautiful, was seized by Merovech, Chilperic’s son and her own nephew, and married to him by a complaisant bishop: but the church declared the marriage incestuous. Chilperic sent Brunhilde to Metz, and sent off another son, called Clovis, to take the Aquitanian cities; the Gallo-Roman Mummolus defeated him, and Fredegund, enraged at his attempted marriage to Brunhilde, had him assassinated. Fredegund’s own two children now died as infants and she persuaded Chilperic they had been bewitched through Clovis. This prince was also killed.

Guntram, anxious to appease the feud and to ally, as he usually did, with the weaker party, went to negotiate with the Austrasian nobles and Childebert II, and made a solemn alliance with them against Chilperic: he adopted the child as his son. Chilperic at Paris remained unimpressed: he even gave his attention to building circuses at Paris and Soissons and giving spectacles to his people in the Greco-Roman manner. When trouble arose between Guntram and the Austrasians because Guntram would not give up the Austrasian portions of the cities of Marseilles and Angers, Chilperic arranged to seize and adopt Childebert himself. Aegidius, bishop of Reims, arranged the matter in 581: and the Austrasians got their portion of Marseilles and installed their own court and bishop there. Two years later Chilperic ravaged Guntram’s lands and forced him to give up to Childebert the Burgundian portion of Marseilles (584): Guntram remade his alliance with the Austrasians, who preferred such an alliance to one with Chilperic: but the young Childebert, when he might have settled with Chilperic, went off to lead a fruitless expedition to Italy.

Meanwhile another son, the future Lothar II, was born to Chilperic, and brought up almost as a prisoner on the Neustrian demesne of Vitry, for Fredegund feared he might be bewitched like his two little brothers; and Chilperic arranged an honourable marriage for his daughter Rigontha. She was sent off from Paris to marry the Visigothic prince Recared, son of Leovigild, and then Chilperic went hunting in the woods surrounding his demesne at Chelles, near Paris. There he was murdered, at dusk, as he was getting off his horse, resting his hand on the shoulder of an attendant: an unknown assassin stabbed him and escaped.

The death of Chilperic in 584 removed a remarkable figure from the Frankish scene. Whereas among the Anglo-Saxons, Lombards and Vandals, a king who admired Romanitas usually regarded Christianity as one of its aspects and went down to history as a ‘good’ king, Chilperic seems to have been inspired by the pagan and despotic possibilities of Roman rule. He was formally Christian: he made offerings to churches and completed the basilica of St Medard at Soissons; he knew enough Latin to perceive that certain Germanic sounds were not expressible in the Latin alphabet and he ordered that four letters should be added. He examined with similar zeal the doctrine of the Holy Trinity, declared it absurd and ordered that three gods should be worshipped. Gregory of Tours could scarcely find words strong enough to condemn him: he called him ‘the Nero and Herod of our times’, and added:

For he used to devastate and burn many regions and feel no grief thereat but rather pleasure, even as Nero of old used to sing the tragedies while his palace burned.… Yet he was not even a good Latin scholar (Gregory continued), for he composed two books in the manner of Sedulius (the fifth-century poet who wrote a long, somewhat rhetorical Carmen paschale and also the hymns still sung in the divine office, A solis ortus cardine and Hostis Herodes impie) and the verses in these books would not even stand on their own feet, for he did not understand metre and put short syllables for long ones and long for short: and other small works or hymns or prose lessons [missas] he enjoined to be used, for no reason whatever. He despised the suits of the poor. He was wont to blaspheme bishops and when he was in privacy he used to arrange ridiculous charades and jokes, about the bishops of churches above all.… He hated nothing worse than churches. He often used to say: See how poor our fisc is, and how our riches have been transferred to the churches: nobody reigns in this country but bishops: our honour is diminished and transferred to the bishops of the cities.

He used, Gregory added, to hold invalid wills made in favour of churches, and there was no kind of evil luxury he did not practise. He used to have the eyes of those who offended him torn out. He added to the protocol of his writs: If any man despise this our precept, let his eyes be put out.

Both the royal husbands of Brunhilde and Fredegund, the chief agents of the blood feud, were now dead, and the political balance of the kingdoms much disturbed. Guntram now stepped in for the second time to protect the weaker side, now that of Fredegund and the Neustrians. Fredegund fled, with her four-month-old son, for sanctuary to the bishop’s cathedral, the church of Notre Dame, at Paris, and Guntram came to Paris and tried to allay the resentment of those of Chilperic’s subjects whom he had wronged. He recognized bequests to churches which Chilperic had declared invalid and gave alms to the poor, and, addressing the Parisians in the cathedral, asked to be allowed to safeguard and bring up his nephews, Chilperic’s sons, himself: at least for three years. The juncture was the more dangerous as an adventurer, Gundobald, claiming to be a son of Lothar I, had gained some success in Aquitaine: he had Toulouse and Bordeaux, and was raised on the shield in the Limousin, with the adherence of Mummolus.

Childebert II, who had just attained the Frankish majority, fifteen years, now came to Guntram and was solemnly re-adopted and declared his heir. He led an expedition to Aquitaine and besieged Gundobald in Comminges, where the latter was taken and killed (585). In the north Brunhilde, enraged at the dukes Ursio, Rauching and Bertefrid who had bluntly opposed her attempt to prolong her regency, had them murdered, together with Aegidius, archbishop of Reims. The queen was, to the Austrasian nobles of the ‘palace’, a foreigner: the ‘palace’, the royal officers among whom the mayor of the palace was not as yet the greatest, meant to rule themselves (587).

The treaty of Andelot (28 November 587) set down the terms of alliance made between Brunhilde, Guntram and his nephew, and made a notable re-division of the patrimony of Charibert; the first division had already caused trouble for nearly twenty years. Territorially, Guntram took Sigebert’s portion, including a third of the city of Paris, and Childebert II took the remainder: each king left his portion to the survivor. It was also agreed that the émigrés leudes, trusted royal servants who had fled to the court of another king in times of danger and there formed a faction hostile to the rulers of their own land, should be expelled from the courts where they had taken refuge; and that grants made to churches and lay lords and hastily resumed on the mere suspicion of disloyalty should be made irrevocable, both for the past and the future. Much resentment had been aroused by the Merovingian resumption of beneficia: bishops might grant the life tenure of a piece of land or a vineyard as stipend to a deacon or presbyter of merit, and hope to get it back at death; but the hasty resumption of lay benifices by the kings aroused much opposition by the holder himself, if made before his death, and from his family, if after death. Uncertainty of tenure was one of the chief causes of resentment against the Merovingian kings.

The treaty of Andelot gave Gaul peace for some years, after the recent disturbances of the civil war. Fredegund tried vainly to procure the assassination of Guntram, but ‘the good prince’ died peaceably in March 592. Childebert II, now holding more than two-thirds of Gaul, tried to make himself master of all: he attacked his cousin, Lothar II, but his forces were defeated near Soissons: Neustria survived. Childebert II died aged twenty-five in 595, and Fredegund in 597.

Brunhilde was now the greatest figure in France; she ruled, at Metz or in Alsace, for her eldest grandson, the child Thibert, while the younger grandson, Thierry, had Burgundy and Orleans as his portion. In 599 Lothar II was again defeated by his cousin, and his realm of Neustria restricted to a few pagi round Beauvais, Amiens and Rouen, but this brought no advantage to Brunhilde. Her palace was now strong enough to drive her from Austrasia (599), the mayors of the palace assuming the leadership of the ‘government’ at this point. Brunhilde took refuge with Thierry in Burgundy: but she still guided the struggle between Austrasia-Burgundy and Neustria.

In 604 a Burgundian mayor of the palace, Bertoald, was surprised with a small army by the Neustrian mayor of Lothar II, Landri. Bertoald fled to Orleans and was besieged till Thierry and a Burgundian army relieved him. Neustrians and Burgundians fought on Christmas Day, 604: Bertoald was killed, but Landri was put to flight, and an infant son of Lothar, Merovech, taken. Thierry was able to enter Paris (605), and was only prevented by his nobles from despatching Lothar; he took this amiss, fought his own Burgundian mayor at the royal villa of Quierzy-sur-Oise, and had the mayor assassinated in Thierry’s own tent. He had been hated for his fiscal exactions, and a more prudent mayor was appointed.

Though allies as against Neustria, Thierry in Burgundy and young Thibert in Austrasia (the ruler backed by the Austrasian palace) were now jealous of each other. In 610 Thibert invaded Alsace with a semi-barbarian army, was met by Thierry with a smaller force, and imposed on him cessions of land in Alsace and Champagne. In revenge, Thierry procured the neutrality of Lothar II, led an army to Toul, a city he had had to cede, and defeated Thibert in May 612. Thibert was taken, delivered to his grandmother Brunhilde, forcibly given the tonsure, and soon after assassinated. His infant son Merovech had his skull beaten in.

But again the focus of power shifted, for Thierry died in 613 on the eve of attacking Lothar and making himself master of the regnum Francorum. Though quite a young man, he left four sons, of whom Brunhilde wished to recognize the eldest, aged twelve, as king. But this would have made her the regent of a young king for the third time, and the Austrasian palace was willing even to ally with Neustria rather than see this. Bishop Arnulf of Metz and Pepin I (called, though not by contemporaries, of Landen) made alliance for Austrasia with Lothar II: and Brunhilde, after trying in vain to raise the traditional allies of Austrasia, the wild hordes of ‘beyond the Rhine’, fled to Burgundy. Even Burgundy could no longer be trusted: there, the mayor, secretly allied with Lothar II, was intriguing for support with the ‘farons’ of Burgundy (farons connected with the tribal farae and the later old French baro) with the bishops and Burgundian leudes. The army of Austrasia-Burgundy advanced to meet that of Lothar, and the opposing armies refused to fight: Lothar advanced unopposed down the valley of the Saône, and seized Thierry’s four sons. The two eldest he killed; the third, Merovech, he spared, as his own godson, sending him into retreat: the youngest, a Childebert, disappeared.

In the autumn of 613 the climax came. Brunhilde was seized at the foot of the Jura, accused of causing the death of ten kings (including the death of her own husband actually assassinated by Fredegund), and those of Thierry’s grandchildren whom Lothar II had himself killed. The Franks in the now dim past had lived under the Huns, and, with their notable use of the horse in war, had learned from them the terrible and ancient horse-death for criminals. Brunhilde was tortured for three days, and tied alive to the tail of a vicious horse till her body was torn to shreds. Chroniclers, like Fredegar and the adherents of the Austrasian mayors, compared her violent end to that of Jezebel, eaten by dogs. The old queen belonged to her age: she contended for her family and for personal power, with Neustria and with the Austrasian palace. They were too strong for her in the end, mainly through the premature death of her son Childebert II and her grandson, Thierry II.

Against all probability, Lothar II attained in 613 to the sole rule of France, but not to a centralized rule, for that the Merovingians never obtained. He recognized the premier rank in the palace of the mayors, and that by irrevocable act. He confirmed the mayors of Austrasia and Burgundy; in his own Neustria, Landri was succeeded by Gundoland.

The great resettlement of political relations of the three kingdoms was marked by the holding of a reform council in Paris in October 614: 79 prelates were present, and it is notable that they felt themselves strong enough to insert at the head of the canons passed one clearly directed against the royal nomination of bishops.

When a bishop dies, that man ought to be ordained in his place whom the metropolitan (by whom he is to be consecrated) with his fellow bishops of the province, and the clergy and people (populus) of his city shall choose, without any loan or grant of money. And if otherwise he shall get the position by force, or if, by any negligence without the election of the metropolitan and the consent of the clergy and citizens, he shall be introduced into the church, his ordination shall be held null and void according to the ancient statutes of the fathers.

It is notable that Lothar II should have allowed such a canon to be passed: neither he nor his successors observed it. Other canons dealing in particular with the trial of ecclesiastical disputes by the bishop, and the non-trial of clerks by the secular judge, followed.

The canons of this council of Paris were, however, of less constitutional importance than the edict issued by Lothar II in October 614, promising a general reform: it was the price of the general acceptance of his sovereignty. It was the first time any Merovingian king had accepted responsibility to the law: the edict enumerated abuses of the royal power in the past and promised that they should not recur in the future. There was no Magna Carta, no scheme of constitutional government or even a list of detailed reform measures: but the nobles were in a stronger position thereafter. The three palaces of the kingdom, with their officers in present attendance on the king and their past officers domiciled as counts, dukes, domestics, etc. out in the countryside, formed some sort of a ‘central government’ for each kingdom.

Lothar IPs general supremacy from 613 was only exercised at the price of delegation of power. In 616 a diploma granted local concessions to the mayor and the forons of Burgundy; and when Lothar’s son Dagobert was about ten or twelve, Lothar sent him to live as sub-king in Austrasia, under the tutelage of Arnulf, bishop of Metz and the mayor, Pepin I. Lothar was strong enough, however, to keep the Austrasian share of Aquitaine and the border region of the Vosges; and when Dagobert was fifteen, Lothar made him come to his villa of Clichy, near Paris, for his marriage: a slight to Austrasia. At the marriage, father and son quarrelled, Dagobert claiming all the territories of the old Austrasia; Lothar agreed to accept the arbitration of twelve Frankish doomsmen, who gave to Dagobert the larger Austrasia while leaving Lothar the Austrasian cities in Aquitaine.

In Burgundy, however, Lothar fared better, achieving the suppression of the mayoralty in his own interest. The mayor died in 626 or 627, and Lothar was able to avoid the succession of his son. He assembled the Burgundian nobles and leudes at Troyes, and asked them if they wished for a successor to the mayor: they answered that they desired no mayor, and the Burgundian palace henceforth ruled Burgundy under Lothar’s distant supervision.

In Neustria, however, Lothar’s personal weakness showed itself in failure to punish a murder done at the time of assembly, in the palace itself, a notable breach of the king’s peace, Ægyna, one of the Saxons who had settled in the Bessin, murdered Erminarius, the ‘governor of the palace of Charibert’, the king’s younger son. To avoid a fight in his royal villa of Clichy, where the annual assembly was being held, Lothar ordered Ægyna to withdraw to the south bank of the Seine, and many of the nobles who favoured his cause went with him, to the hill of Montmartre. There Charibert’s uncle, Produlf, besieged him; but Lothar forbade the farons of Burgundy to cross the river, either to defend or attack, and he ordered them to crush those who did. Peace was kept by Lothar’s action: but the murder went unavenged, the breach of the king’s peace, so far as we know, unemended. Lothar II died in 629, and Fredegar, the Austrasian annalist-compiler, allowed that he had been generous to churches and the poor: but too much given, he said, to the counsels of women. He was buried in the abbey church of St Vincent, later to be Saint-Germain des Prés, then just outside Paris.

The reign of Dagobert I, Lothar’s son (629–639), was that of the last Merovingian who really ruled. As Charibert, the eldest son of Lothar, was apparently mentally deficient, Dagobert was recognized as king of Lothar’s kingdom, the regnum francorum, and Charibert was left with the kingship of a few cities round Toul.

To assert his authority, Dagobert in 630 travelled through Burgundy, doing justice, and in 631 he toured Austrasia. Here Arnulf came from the monastery to which he had retired to give him counsel, and Pepin the mayor and bishop Humbert of Cologne were ready to direct Austrasian affairs: it was expected that Dagobert, like his ancestors, would rule from Austrasia. Dagobert found, however, that Austrasia was too peripheral for the rule of the regnum francorum; he preferred to rule, like his father Lothar and like Clovis, from Paris. The Austrasians resented the consequent pre-eminence of Neustria, and the Burgundian Fredegar disapproved: he wrote c. 660 and said that Dagobert had forsaken his earlier love of justice and become too greedy in amassing the lands of churches and his leudes; he had three queens, and really more concubines than it was fitting to mention. He was generous of his alms, and might have attained the heavenly kingdom but for his avarice: even Pepin the mayor dared not remonstrate with him: his favourite counsellor was Aega, mayor of the Neustrian palace: the head and front of Dagobert’s offending, to an Austrasian sympathizer.

The unfortunate Charibert died in 632: and Dagobert rearranged the rule of his kingdom. To appease the Austrasians, he sent them his three-year-old son Sigebert, to be installed king at Metz, confiding him to the tutelage of the bishop of Metz and duke Adalgisel. After this another son was born to him, called Clovis: Dagobert made the bishops and nobles swear to accept him as king of Neustria and Burgundy. To outsiders, Dagobert seemed respected and strong within his great kingdom: and he was able to pay some attention to his neighbours.

In 637, the Gascons under their duke Ægyna revolted against Burgundy and Lothar subdued them. He sent a Burgundian army, under dukes who were not Burgundian, and under the curious supreme command of Chadoind the referendary, down into Gas-cony, and they drove the rebels into the Pyrenees and reduced their duke to submission.

Dagobert further intervened in Visigothic Spain in favour of Sisinand: a large tribute in gold was promised him in return. In Italy even he had sufficient influence to make Rothari give back a Frankish princess he had imprisoned.

On his eastern frontier Dagobert, however, was less fortunate. Danger threatened it, and particularly the Franks of Austrasia, from the Slavs now settled between the Oder and Elbe, in Bohemia and in the eastern Alps: the swaying tide of Slavs was now half-united by the leadership of Samo, the centre of whose power was in Bohemia. Frankish merchants were attacked, and c. 632 Samo’s subjects, called Wends, robbed and killed such a band of Franks, and Dagobert sent Samo an envoy to demand justice. When he was merely chased away, Dagobert declared war, and sought allies among the Lombards and Bavarians. They were old enemies of the Slavs and had some success against them: but a Frankish army was cut to pieces by Wends who invaded Thuringia, and the border tribes who had hitherto obeyed the Franks now, from 632, obeyed Samo.

Dagobert therefore assembled an Austrasian army and retook Mainz, and summoned armies from the other kingdoms to complete the eviction of the Slavs: but at this juncture the Saxons offered to defend the east Frankish frontier, provided the old tribute of 500 cows a year, paid since the time of Lothar I, were remitted. Dagobert accepted: but the result was unfortunate for the Frankish kingdom. Austrasia became increasingly independent under its sub-king, Sigebert; the Saxons grew stronger, and to the Thuringians, in their region south of the Saxons and the Harz mountains, Dagobert had to allow a duke, Radulf. The dukes were always military leaders at the time, and the Thuringians could scarcely defend themselves from the Slavs without one: but he made himself increasingly independent. The needs of frontier defence, as later under the Carolingians, made for local independence. Against Samo himself in Bohemia, Dagobert had led no expedition: but further danger from Slav Bohemia was averted by the collapse of Samo’s power on his death.

Dagobert died in 639. He was carried to the basilica of Saint-Denis in his sickness, but found no cure from his holy patron. He confided queen Nantechilde and his son Clovis to Aega the mayor, and on 19 January he died, aged thirty-six, and was buried in the basilica of Saint-Denis. Merovingian monarchy, in its true sense, was buried with him.

From 639 to 721, the death of Dagobert I to that of Chilperic II, some Merovingian shadow ruler, often a child, remained the symbol of the old Frankish unity, and the mayors of the palace of Neustria and Austrasia in effect governed their kingdoms and strove for a general pre-eminence.

At the beginning of this period of shadow Merovingian rule, Clovis II, Dagoberts younger son, ruled Neustria and Burgundy through Aega, and after his death in 641, through Erchinoald, both conciliators of the nobles. Austrasia, under Dagoberts other son, Sigebert III, desired separate government: her palace, headed by Pepin and bishop Humbert, asked for and obtained a share of Dagobert’s treasure. Pepin, old and retired, died in 640: but his position had been so strong that his son Grimoald claimed the mayoralty, and obtained it by means of having Otto, mayor of the palace for the child Sigebert III, assassinated (643). Meanwhile in Burgundy, which had had no mayor recently, the regent Nantechilde summoned a council to meet at Orleans, and persuaded it to accept Flaochad, a Frank who had married her niece, as mayor. But the Burgundians feared a strong mayor: they made Flaochad swear to respect the honour and dignities of lay nobles and bishops (642). The mayoralty was thus weak in Burgundy and Neustria, though strong in Austrasia; the strength and turbulence of the Neustrian nobles was shown when Ermanfried, son-in-law and, as he hoped, heir to Aega, a few days before Aega’s death assassinated his rival, count Hainulf in full assembly. He then fled to Reims, to take sanctuary in the basilica of Saint-Rémy. Another instance of noble turbulence was the open quarrel in Burgundy of the rich and proud patrician, Willebad, with the mayor, Flaochad: a great plea was held at Chalons-sur-Saône, and the proceedings ended in a kind of ordeal of battle, fought between Willebad and Flaochad and their adherents. Willebad was killed, but when Flaochad died of fever eleven days later, men said it was the judgment of God upon them both for their avarice and ill deeds.

Clovis II died, aged twenty-three, in 657, and Sigebert III, his brother, in 656, aged twenty-seven; he had fought Radulf, duke of the Thuringians, with some success, but government had rested with his mayor, Grimoald.

Grimoald almost overthrew the strong family position of the Arnulfings by an attempt at this point to seize the royal title as well as the substance of power. He desired the throne for his son, and had him adopted by Sigebert III shortly before a son was actually born to Sigebert himself and called Dagobert. Sigebert apparently trusted Grimoald to secure the child Dagobert’s succession, but on Sigebert’s death Grimoald had his own son enthroned as Childebert III, and had young Dagobert shorn and delivered him to the bishop of Poitiers, with instructions to send him off to some distant monastery. The bishop thought fit to send him to Ireland, where he lived for some twenty years. Meanwhile Grimoald ruled Austrasia for seven years under cover of his son, proclaimed as Childebert III; he was then tricked into going to Paris by the Neustrians, seized, imprisoned, and died (662). His wife was sent off to the cloister under the charge of bishop Robert of Tours, the young Childebert III disappeared, and for some years the Arnulfings disappeared from the political scene in Austrasia.

The question of the succession in Austrasia in 662 remained open: young Dagobert, away in Ireland was forgotten or his place of refuge unknown. The strongest political personages were Neustrian. Since Clovis II had died there in 657, Balthilde had secured the recognition of her son, Lothar III, as king; she had been a beautiful Anglo-Saxon war captive, a slave girl brought by Erchinoald, mayor of the Neustrian palace. They had had four sons, the eldest now in 657 accepted as Lothar III. Balthilde was known as the patroness of churches and monks: she had given great estates to Saint-Denis, the family abbey of the Neustrian Merovingians, and she had tried to get that early and anomalous foundation, partaking rather of the nature of a house of canons than monks, to accept the strict observance, the subdivision into three choirs for the rendering of perpetual praise to God: the observance of Saint-Riquier. Here she had failed: Saint-Denis was grateful for the endowment but would have nothing to do with perpetual praise. Balthilde now proposed as king to the Austrasian nobles her second son, who became Childeric II (662–675); he was the more acceptable in Austrasia as he reigned under the protection of Himnechilde his aunt (the mother of the absent Dagobert II), and duke Vulfoald, Austrasian mayor of the palace after the fall of the Arnulfings. When Lothar III attained the age of fifteen, in 664–5, Balthilde withdrew to the monastery she had founded on the royal demesne at Chelles, where she died a holy death in 680. Bede speaks of the Anglo-Saxon princesses who in this century were sent to Chelles and other French nunneries for training in the religious life. It appears that many of these royal nunneries in France were ‘double’, i.e. had a staff of chaplains or monks residing in a separate dwelling within the hedge or fence of the monastic enclosure: and that the so-called Anglo-Saxon ‘double monasteries’ were copies of the French ones. Such an organization was indeed the only one suited to a house of nuns founded by a princess-abbess; the strange career of the beautiful Balthilde had its results both sides of the Channel in the spread of these ‘double’ minsters.

Balthilde’s son, Lothar III (657–673) ruled as a phantom monarch over Neustria and Burgundy, not as representing her influence but under the tutelage of her enemy, Ebroin, now a powerful mayor of the Neustrian palace. When Lothar III died in 673, Ebroin had his young brother accepted as Thierry III, without even summoning a council to recognize him. This, however, was going too far: the nobles of Neustria and Burgundy, fearing Ebroin’s power, appealed to king Childeric II of Austasia for help. He hastened to Paris with his own mayor, Vulfoald, and they seized Thierry III, sheared him and made him a monk at Saint-Denis. Ebroin they captured and nearly killed: but at the prayer of the bishops merely sheared him also and sent him off to be a monk in the distant house of Luxeuil, at the foot of the Jura. It was already clear in 673 that the mayors of the palace were as strong as kings: it was not yet clear whether the mayors of the east or west Franks would achieve predominance.

At the moment, the nobles were in a position to bargain with Childeric II, now sole king in the regnum Francorum, about the powers of the mayor: they asked what need there was of a mayor, or at any rate one like Ebroin, who posed as a tyrant and set himself up above the other nobles? Childeric II indeed desired the reality of rule, but could only achieve it by a skilful balancing of personal interests, and in the end his attempt failed; he promised concessions to the nobles, then revoked them and tried to rule by the counsel of Leodegarius, bishop of Autun and Hector, patrician of Marseilles. Both, however, fell into disgrace and had to flee, Leodegarius being sent off to Luxeuil. Childeric II, holding the reins of power, even planned to intervene in Lombardy between rival claimants: but in 675, as he was hunting in the woods of Chelles, he was assassinated. The murderer killed his queen too, and it took some courage for a bishop to come forward to bury them. Audoenus (St Ouen), however, who had been a referendary and was now the revered bishop of Rouen, came forward and buried the royal victims at the abbey of Saint-Vincent. Childeric’s mayor, Vulfoald, fled to Austrasia. The vacancy of power in Neustria permitted Ebroin to stage a come-back.

Immediately after Childeric II’s murder, the Neustrian and Burgundian nobles took Thierry III out of Saint-Denis and chose for mayor Leudesius, son of the mayor Erchinoald, a move unacceptable to either Leodegarius or Ebroin. The latter succeeded in escaping from Luxeuil. He allied with the nobles of Austrasia, and through their influence, a real (or pretended) son of Thierry III was placed on the throne as Clovis III, and Leudesius was executed. But when Ebroin was firmly in power in Neustria, he thrust away Clovis III and took back Thierry III: and under cover of nominal Merovingian rule tried to deal with over-great nobles, particularly those in non-Neustrian regions. Two bishops of noble origin were trying to make themselves independent in Burgundy: Didier, bishop of Chalons-sur-Saône and Bobbo, bishop of Valence, who had already been degraded. They were the enemies of Leo-degarius in Autun, who was no less Ebroin’s own political rival: they joined forces with the dukes of Champagne and Alsace, and besieged Leodegarius in Autun. To save his city, he gave himself up and was brought to Ebroin, who had now survived the threatened rebellion of the nobles and was supreme in Neustria. Ebroin confiscated the lands and goods of his enemies, tortured and blinded Leodegarius, and had him degraded by a complaisant synod (677 or 679). Leodegarius’ brother he had stoned to death, and all without arousing protest from the mayors of Burgundy and Austrasia.

Austrasia, however, was not long content with the effective rule of Ebroin under the shadow king Thierry III: her nobles remembered the existence in Ireland of Dagobert II. A message was sent to Wilfrid, bishop of York, inquiring his whereabouts: Wilfrid took action, sent for him from Ireland, welcomed him in York and passed him on to the continent. In the early summer of 676 the exile of twenty years was accepted as Dagobert II by the Austrasian palace, and even by the Austrasian parts of Aquitaine. A minor war of pillage and raids followed between Thierry III and Dagobert II, but only till 679. In December that year, by the initiative of the dukes and the consent of the bishops, Dagobert was killed out hunting by his own godson: Vulfoald the mayor disappeared suddenly at the same time. To cover the murder, the nobles reproached Wilfrid, returning through Gaul at the time, for helping to bring back to them so bad a king, ‘another Rehoboam’; but the populace resorted to his burying place as to that of a saint.

The murder of Dagobert II was the signal for the recovery of power by the Arnulfings, and this time permanently. They had been quiescent for fifteen years. Pepin II, who had married Begga, the sister of Grimoald, now seized power in Austrasia, and war between the mayors of Austrasia and Neustria was now inevitable. Ebroin and his puppet king, Thierry III, at first defeated Pepin and the Austrasians near Laon: but he ruled Neustria so brutally that he was soon murdered. An oppressed domesticus (see p. 297) killed him, c. 680, and fled for refuge to Pepin in Austrasia. The aim of Ebroin had been double, and it had doubly failed. It had stood for Neustrian supremacy as against Austrasian; and for the denial of the aristocratic claim to hold all high office in the palace. Ebroin himself had not been of the old nobility, and he had dislodged many lay nobles and many aristocratic bishops from power: he cannot claim any great statesmanship.

An uneasy peace was maintained for a time between Neustria and Austrasia, largely by the mediation of St Ouen. Two candidates struggled for the mayoralty in Neustria, to the advantage of Pepin II, who was asked to intervene by the archbishop of Reims. In 687 Pepin defeated the Neustrians at Tertry, near Saint-Quentin. The Neustrian mayor, Berchar, was killed, and Thierry III and the royal treasure fell into Pepin’s hand. It was the first military victory of the Austrasians over the Neustrians for a hundred years, and it ushered in the dominance of the Austrasian mayors. Pepin II accepted the suzerainty of Thierry III, but he put in a mayor of his own choosing at Paris and distributed the confiscated estates of the nobles at will. When the mayor of his choice, Norbert, died in 700, he put in one of his own sons, significantly named Grimoald, as mayor of Neustria.

The real significance of the battle of Tertry is the fall of the Neustrian palace, as an independent organ of government. Clovis had been strong enough to rule from Paris, and there the Merovingian tradition had its strongest roots. Lothar I, Lothar II, Dagobert I, Childeric II had all sought to rule the regnum Francorum from Paris, and when Austrasia, the region of Germanic settlement, of Germanic recruitment, of Germanic frontier defence and the strongest Frankish armies, became too strong to support the rule of Neustria, the Merovingian dynasty fell, and the Neustrian palace with it. Though the public acts and private charters of Austrasian mayors continued for a time to be dated by the names of Merovingian kings, these were now indeed phantoms.

Their nominal reigns can be mentioned briefly, as stages in the increasing power of their mayors. Thierry III died in 690, and Pepin II imposed as king Clovis, a child who soon died, and in 694 Childebert III (who died in 711) and Dagobert III; all lived in Neustria at the will of the Austrasian mayors. The Arnulfings had learned a lesson from the career of Grimoald: they allowed the last Merovingians, mainly children, to live in an atmosphere of superstitious reverence: they no longer wished to dispense with a king whom they regarded as a symbol of Frankish unity. It is doubtful whether Neustria would in the early part of the sixty odd years which intervened between Tertry and the coronation of Pepin III have tolerated the naked rule of an Austrasian noble as king: Merovingian shadow royalty was a sop to Neustrian pride.

Dangers which menaced the Franks from external enemies were meanwhile dealt with by the Austrasian mayors.

The Frisians from the coast of the North Sea to the river Weser, pagan and hostile, had for some years been pressing south: they had taken from the Franks Utrecht and Durstedt. Their leader Aldgild, who had allowed Wilfrid to begin the conversion of his people, was now replaced by duke Radbod who was hostile both to Christianity and the Franks. Pepin II fought him for some months: pressed the Frisian army back beyond the Rhine and regained Utrecht and Durstedt. In Utrecht he installed the Anglo-Saxon missionary Willibald as bishop. He sealed an alliance with Radbod by a family alliance, marrying his son Grimoald to Radbod’s daughter, newly baptized.

Against the Alemans Pepin also led expeditions: their duke Godefrid had disclaimed the suzerainty of a Frankish mayor of the palace and made himself largely independent. Between 709 and 712 Pepin fought the Alemans under Godefrid’s successor and re-established Frankish authority, which was the less difficult in that the Alemans were already Christian.

Against the Bavarians he did the same. Both Irish and Gallo-Roman missionaries had worked here, and for the ultra-Rhenane Franks Pepin founded the see of Salzburg; Christianity was a security for Frankish influence.

In Aquitaine, Pepin was less successful in asserting a general Frankish overlordship: the land had been too much partitioned, and the various groups of cities still adhered to a divided lordship. The Auvergne, Poitou and Touraine were loyal to Austrasia: the Limousin and Toulousain to Neustria, while Le Berry, Perigord and Quercy were Burgundian. Even church councils could not normally be held for the whole of Aquitaine, and counts, dukes and patricians struggled for power with very little reference to Austrasia.

Pepin II (whom modern historians call Pepin of Heristhal) was the first to exercise a general Carolingian power: he prepared the way for Charles Martel, Pepin III and Charles the Great. But the perpetuation of the dynasty at this point hung by a thread: in 708 Pepin II’s son Drogo died: in 714 Grimoald was assassinated by a pagan while praying at the tomb of St Lambert at Liége, and when Pepin II himself died in 715, he had no surviving son. He was eighty years old when he died, and his wife Plectrude wished to govern in the name of her grandsons: but the nobles could not tolerate this. The Neustrians rose, beat the Austrasians in a battle in the forest of Compiègne, struck through the woods to the Meuse, made overtures to the still pagan Radbod and to the Saxons across the Rhine. The latter crossed the Rhine and ravaged down to Cologne. In this unheard-of crumbling of the power built up by Pepin, his son by the Lady Alpaïs, Charles, escaped from prison and sought for power.

At the end of 715, Dagobert III also died, and in the absence of an effective mayor, all was confusion and, for Austrasia, danger. The Neustrians took from the cloister a reputed son of Childeric II, a forty-year-old clerk, and when his hair had grown accepted him as Chilperic II. Salvation for Austrasia was to come from Pepin IPs grandson Charles, the warlike son of Alpaïs. He gradually retrieved the military position, though he was defeated when he first attacked the Frisians and though the Neustrians and Chilperic II besieged Cologne and required Plectrude to hand over the royal treasure and recognize Chilperic’s authority. In 716, however, Charles (Martel), who had been hiding in the Ardennes, surprised the Neustrians and defeated them with great losses. In 717 he again defeated the Neustrians at Vinchy: and he was now strong enough to force Plectrude to give up to him his father’s treasure. In 718 he found a descendant of Thierry III, and set him up as the Merovingian king, Lothar IV (718–719). Dealing first with the Frisians and Saxons, he led an expedition which defeated and killed Radbod and established Frankish power over the Frisians. The much weakened mayor of Neustria appealed for help to duke Eudes of Aquitaine, who marched to the Loire, crossed it and joined the Neustrians. He was defeated, however, by Charles, and had to withdraw, first to Paris and then to Aquitaine, taking with him Chilperic II and the Neustrian treasure. By 719 the Neustrian mayor had fled in impotence to the west.

At this juncture, Lothar IV died, and Charles needed another Merovingian shadow king. He negotiated with duke Eudes, who was just then embarrassed by Muslim attack in Aquitaine, for a general peace: it was arranged that Charles should accept Chilperic II and guarantee Eudes’ position in Aquitaine. But in 721 Chilperic II also died.

Charles then took from the monastery of Chelles a Merovingian child, the son of Dagobert III and gave him the name of Thierry IV (721–737): though the Neustrian mayor held out at Angers for some time against accepting him, he had in the end to submit. From 719, in spite of the nominal sovereignty of Thierry IV, Charles Martel ruled France, including Burgundy. The death of bishop Savary of Auxerre there in 715 had removed the strongest rival to his rule.

The descendant of bishop Arnulf of Metz and Pepin of Landen had seized power from the Merovingians: the mayor of the Austrasian palace had triumphed over the other mayors. For a short time yet the Arnulfings, though they ruled Francia, were to retain a Merovingian king as a symbol of Frankish unity.

BIBLIOGRAPHICAL NOTE