With a mere $1,700,000 price tag, the Bugatti Veyron is the world’s most expensive production road car. It’s hard to be sure what the cheapest car is, although the Dacia Sandero probably has a good claim to this honour, at about 1 per cent of the cost of the Veyron. But both cars have a number of things in common, and one of these is that each needs to be switched on before you can go anywhere. If you don’t activate the engine systems, nothing will happen.

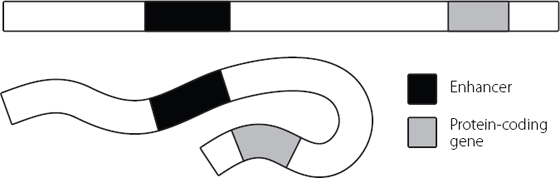

Our protein-coding genes are the same. Unless they are activated and copied into messenger RNA, they do nothing. They are simply inert stretches of DNA, just as a Veyron is a stationary hunk of metal and accessories until you hit the ignition. Switching on a gene is dependent on a region of junk DNA called the promoter. There is a promoter at the beginning of every protein-coding gene.

If we think in terms of a traditional car, the promoter is the slot for the ignition key. The key is represented by a complex of proteins that bind to a promoter. These are known as transcription factors. These transcription factors in turn bind the enzyme that creates the messenger RNA copies of the gene. This sequence of events drives the expression of the gene.

It’s relatively easy to identify promoters by analysing DNA sequences. Promoters always occur just in front of the protein-coding regions. They also tend to contain particular DNA sequence motifs. This is because transcription factors are a special type of protein that can identify and bind to specific DNA sequences. If we analyse the epigenetic modifications at promoters, we also find consistent patterns emerging. Promoters have particular sets of epigenetic modifications, depending on whether or not the gene is active in a cell. The epigenetic modifications are important regulators of transcription factor binding. Some modifications attract transcription factors and associated enzymes and this results in gene expression. Others prevent the factors from binding and make it really difficult to switch a gene on.

Researchers can copy a promoter and reinsert it elsewhere in the genome, or even into another organism. These kinds of experiments confirmed that promoters usually function immediately in front of a gene. They also showed that the promoter needs to be ‘pointing’ in the right direction. If you insert a promoter sequence in front of a gene, but the wrong way round, it doesn’t work. It would be like inserting a key the wrong way round into the ignition. Promoters are orientation-dependent in their activity.

Promoters can’t really tell which gene they are controlling. They switch on the nearest gene, if they are close enough and pointing in the correct direction. This allows researchers to use promoters to drive expression of any gene in which they are interested. That can be very handy experimentally but it can also have a sinister side. In some cancers, the basic molecular problem is that the DNA in the chromosomes becomes mixed up and a promoter starts driving expression of the wrong gene. In the case of cancer, the gene is one that pushes forward the rate at which cells proliferate. The first to be discovered, and probably still the most famous example of this, occurs in the blood cancer known as Burkitt’s lymphoma. This is a cancer type we already met briefly, in our discussion of good genes in bad neighbourhoods (see page 48). In this condition, a strong promoter on chromosome 14 gets placed upstream of a gene on chromosome 8 that codes for a protein that can really push cell proliferation forwards.*1 The consequences are potentially catastrophic. The white blood cells carrying this rearrangement grow and divide really rapidly, and start to predominate in the blood stream. If detected early in the disease’s progression, over half of the patients with this cancer can be cured, although this requires aggressive chemotherapy.2 For patients with a late diagnosis, decline and death may be appallingly rapid and measured in weeks.

In healthy tissues, different promoters may only be active in certain cell types, usually because they rely on transcription factors that are expressed in some cell types and not others. Promoters also have different strengths. By this we mean that strong promoters switch on genes very aggressively, resulting in lots of copies of messenger RNA from the protein-coding gene. This is what happens in Burkitt’s lymphoma. Weak promoters drive much less dramatic levels of gene expression. The strength of the promoter is dependent on multiple factors in mammalian cells, including the DNA sequence but also the transcription factors available, the epigenetic modifications and probably a host of other variables that we haven’t yet identified.

Driving a graduated response

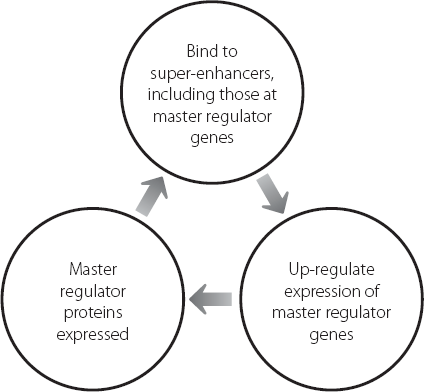

Any given promoter in any given cell type drives a relatively constant level of gene expression, at least in experimental systems. Yet gene expression under normal circumstances is not a binary phenomenon. Genes may be expressed to varying degrees. It’s analogous to being able to drive a car at any rate from one mile per hour up to its top speed of over 250mph for the Veyron, or rather less than half of that for the Sandero. In cells, this flexibility is dependent on a number of interacting processes including epigenetics. But it is also influenced by another region of junk DNA. This region is known as the enhancer.

Compared with promoters, enhancers are very fuzzy. They are usually a few hundred base pairs in length but it’s almost impossible to identify them simply by analysing the DNA sequence.3 They are just too variable. The identification of enhancer regions is also made more complex because they aren’t necessarily functional all the time. For example, a set of latent enhancers has been identified which only start to regulate gene expression once they themselves have been somehow activated by a stimulus. This showed that enhancers may not be pre-determined in the genome sequence.

An inflammatory response is the first line of defence to an assault on the body, such as a bacterial infection. The cells near the invasion site release chemicals and signalling molecules that create a really hostile environment for the invaders. It’s as if triggering a burglar alarm in a house initiated a downpouring of hot, foul-smelling liquid into the room that had been breached.

Scientists studying the inflammatory response were among the first to show that DNA sequences can be co-opted to become enhancers when necessary. In this study, the researchers found that once the inflammatory stimulus was removed, the enhancers didn’t revert to being inert. Instead they continued to be enhancers, ready to up-regulate expression of the relevant genes again, if the cells re-encountered the inflammatory stimulus.4 It’s probably not a coincidence that these enhancers are regulating genes involved in the response to foreign invaders. This memory in terms of gene expression can be very advantageous for fighting off an infection as efficiently and swiftly as possible.

Epigenetics and enhancers – cross-talk in action

One way in which genetic regions can maintain a memory even after a stimulus has gone away is via epigenetics. Epigenetic modifications can make a region easier to switch on again, by keeping the region in a fairly de-repressed state. In human terms, it’s like a doctor being on call rather than on holiday. In the example above, the researchers demonstrated that certain histone modifications remained at the ‘new’ enhancers after the inflammatory stimulus was removed, keeping them in a state of readiness.

We are generally starting to make a bit more progress at identifying enhancers by looking at epigenetic modifications, which are independent of the underlying DNA sequences. The modifications can be used as functional markers to show how a specific cell type uses a stretch of DNA. Researchers have also shown that these modifications can change in cancer, creating different patterns of gene expression that may contribute to the cellular alterations that lead to cancer.5

But even if we can find an epigenetic signature that indicates we may be looking at an enhancer, we still have another problem. We don’t know which protein-coding gene is influenced by a putative enhancer. The only way we can establish this is by disrupting an enhancer using genetic manipulations, and then assessing which genes are directly influenced by this change. This is because enhancer function is different from that of the promoter. Enhancers are not orientation-dependent – they act as enhancers no matter which way they are pointing. The other difference is even more dramatic – enhancers can be a very long way from the protein-coding gene whose expression they are influencing.

There are also far more enhancers than we might expect. A recent comprehensive study looked at the patterns of histone modifications in nearly 150 human cell lines. When they assessed these lines for patterns that looked like enhancers, they found nearly 400,000 candidate enhancer regions.6 This is far more than required if there was a one-to-one relationship between enhancers and protein-coding genes. It’s even too many if we assume that long non-coding RNAs have enhancers.

The enhancers weren’t all found in every cell type. This is consistent with a model where the same stretch of DNA can have different functions in different cells, depending on how it is epigenetically modified.

For many years, we had no clear models of how enhancers really work. We now suspect that in many cases they may be critically dependent on another type of junk: the long non-coding RNAs. In fact, specific classes of long non-coding RNAs may be expressed from the enhancers themselves.7 Many of the long non-coding RNAs we met in Chapter 8 are involved in repressing expression of other genes. But it is now believed that there is also a large class of long non-coding RNAs that enhance gene expression. This was first suggested to be the case for long non-coding RNAs that regulate neighbouring genes. If expression of the long non-coding RNA was increased experimentally, the expression of the neighbouring protein-coding gene also increased. Conversely, if the expression of the long non-coding RNA was knocked down experimentally, the protein-coding gene also showed lower expression.8

Further evidence came from analysing the timing patterns for specific long non-coding RNAs and the messenger RNAs they were believed to regulate. Researchers treated cells with a stimulus that they knew caused expression of a specific gene. They found that the enhancing long non-coding RNA was switched on before the messenger RNA from the neighbouring protein-coding gene.9,10 This is consistent with a model where the long non-coding RNA located in the enhancer is switched on in response to a stimulus, and then in turn helps to switch on expression of the protein-coding gene.

The long non-coding RNA doesn’t drive this increase on its own. The process is reliant on the presence of a large complex of proteins. The complex is known as Mediator. The long non-coding RNA binds to the Mediator complex, directing its activity to the neighbouring gene. One of the proteins in the Mediator complex is able to deposit epigenetic modifications on the adjacent protein-coding gene.* This helps to recruit the enzyme that creates the messenger RNA copies which are used as the templates for protein production. There is a consistent relationship between the Mediator complex and the long non-coding RNA. Experimentally generated decreases in expression of either the long non-coding RNA or a member of the complex each lead to decreased expression of the neighbouring gene.11

The importance of a physical interaction between long non-coding RNAs and the Mediator complex has been shown by a human genetic condition. This disorder is called Opitz-Kaveggia syndrome. Children born with this condition have learning disabilities, poor muscle tone and disproportionally large heads.12 The affected children have inherited a mutation in a single gene. This codes for the protein in the Mediator complex that interacts with long non-coding RNA molecules.**

The more that scientists analysed the activity of the Mediator complex, the more interested they became. One of the reasons was that the Mediator complex is responsible for the actions of a group of enhancers with special powers. These are the super-enhancers, and they are particularly important in embryonic stem (ES) cells, the pluripotent cells that have the potential to become any cell type in the human body (see page 105).13

The super-enhancers are clusters of enhancers all acting together. They are about ten times the size of normal enhancers. Because of this, proteins can bind to the super-enhancers at very high levels, much higher than are found on normal enhancers. This allows the super-enhancers to really ramp up expression of the gene they are regulating. But it’s not just the numbers of proteins that bind that interested the researchers. It’s the identities of these proteins.

As we saw in Chapter 8, ES cells don’t stay pluripotent by chance or passively. In order for ES cells to maintain their potential, they regulate their genes very carefully. Even relatively mild perturbations in gene expression can start to push an ES cell down a pathway that converts it into a specialised cell type. One way of visualising this is to think of a Slinky at the top of a tall flight of stairs. Just the slightest nudge to push it over the edge of the top step is enough to send that Slinky on a very long journey. Perhaps an even better analogy might be a Slinky that is held back from falling down the stairs by a small weight on its trailing end. Remove the weight, and off the Slinky will go.

There are a set of proteins that are absolutely vital for maintaining the pluripotency of ES cells. These are known as master regulators, and they are like the small weight on the trailing end of the Slinky. The master regulators are expressed very highly in ES cells, but at much, much lower levels in specialised cells.

The importance of these proteins was unequivocally demonstrated in 2006. Researchers in Japan expressed a combination of four of these master regulators at very high levels in differentiated cells. Astonishingly, this set in motion a chain of molecular events which culminated in the creation of cells that were almost identical in action to ES cells.14 This is analogous to a Slinky at the bottom of a flight of stairs moving all the way back up to the top step. The cells created by this route have the potential to be converted into any cell type in the body.* This remarkable work, and the research that followed on from it, has generated enormous excitement because potentially we can create replacement cells to treat a large number of disorders. These range from blindness to type 1 diabetes, and from Parkinson’s disease to cardiac failure.

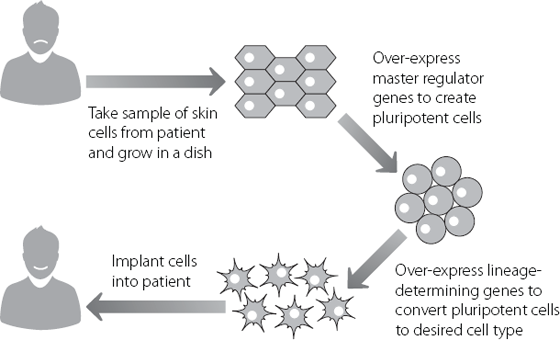

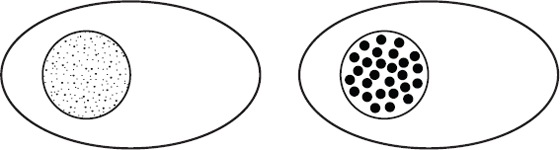

Until this new technology was developed, it was extremely difficult to create appropriate cells to treat human conditions. This is because cells from a different individual usually can’t be implanted into another person. The immune system will recognise the donated cells as foreign and kill them, as if they were an invading organism. But, as shown in Figure 12.1, we now have the potential to make cells that are a perfect match for the patient.

The 2006 work has spawned an industry potentially worth billions of dollars, and also resulted in one of the fastest awards of a Nobel Prize in Medicine or Physiology ever, just six years after the original publication.15

In normal ES cells, some of these master regulator proteins bind at very high densities to the super-enhancers. The super-enhancers themselves are regulating some key genes that maintain the pluripotent state of the cells. The Mediator complex is also present at very high levels in the same locations. Knocking down the expression of a master regulator, or of Mediator, has very similar effects on the expression of these key genes. The expression levels drop, making the ES cells more likely to start differentiating into specialised cell types.

Figure 12.1 The theory behind using patient-derived cells to create therapies tailored for a specific individual.

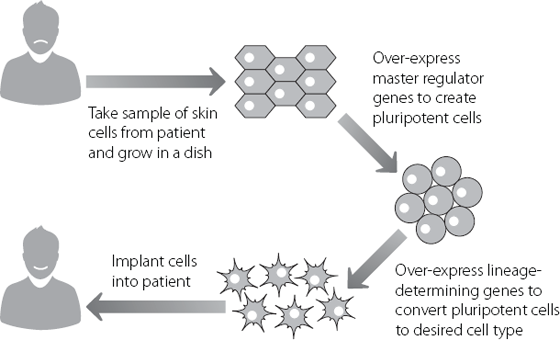

Because the pluripotent state of ES cells is critically dependent on the expression of high levels of the master regulators, it’s perhaps unsurprising that the master regulators themselves are controlled by super-enhancers. This creates a positive feedback loop, which is shown in Figure 12.2.

Positive feedback loops are relatively rare in biology, mainly because they can be difficult to get back under control if they start to go wrong. Luckily, the protein-coding genes regulated at super-enhancers are extremely sensitive to small perturbations in binding of master regulators and a number of other factors. This may mean that even a small change in the balance of some of these factors may be enough to interrupt this positive feedback loop, and allow the cells to differentiate rather than remain pluripotent. After all, it doesn’t usually take much of a nudge to make a Slinky fall down the stairs.

Figure 12.2 The positive feedback loop driving high-level sustained expression of master regulator genes.

Super-enhancers have also been reported in tumour cells, where they are associated with critical genes that drive cell proliferation and cancer progression.16 One of the genes that is regulated by such a super-enhancer is the same one that we encountered earlier in this chapter, which drives Burkitt’s lymphoma. There are also super-enhancers in some normal specialised cells. These bind cell-specific proteins that define cell identity.

Overcoming the distance

Most of the events described so far involve enhancers that are relatively close to the genes that they target, usually within 50,000 base pairs. It’s relatively easy to visualise how this happens, through the long non-coding RNA and the Mediator complex acting to anchor the enzyme that copies DNA into messenger RNA. But there are a lot of situations where the enhancer and the protein-coding gene that it regulates are a really long distance apart on the chromosome, up to several million base pairs away. This is the difference between trying to pass the salt to someone who is on the other side of the table from you at breakfast, and trying to pass it to someone who is at the other end of a soccer field. It’s quite difficult to visualise how this long-range interaction of gene and enhancer can happen. Neither the long non-coding RNA nor the Mediator complex is large enough to span such a huge distance.

In order to understand this process, we have to be a little more sophisticated than usual in the way we think of the genome. Much of the time it’s very helpful to describe DNA in terms of a ladder, or railway lines, because it helps us to visualise the two strands and the way they are held together by base pairs. But the problem with this is it makes us think in very linear terms. We probably also think of DNA as being quite a stiff molecule because subconsciously we are comparing it with solid artefacts from our more familiar physical surroundings.

But we already recognise that DNA isn’t a stiff molecule, because we know that it can be squashed up and compacted really dramatically to fit into the nucleus. So let’s explore that a bit more. If we take the double-stranded nature of DNA as a given (so as not to complicate the picture) we can imagine a section of our genome as being like a very long piece of pasta, maybe the longest piece of tagliatelle ever created. This is marked in a couple of places by food dye, representing the enhancer and the protein-coding gene. Looking at Figure 12.3 we can see two scenarios. When the pasta is uncooked, it’s very inflexible and the enhancer and gene are far apart. But if the pasta is cooked, the tagliatelle becomes flexible. It can fold and bend in all sorts of directions and these can bring the dyed regions representing the enhancer and gene together.

Some parts of our chromosomes are repressed and shut down almost permanently in different cells, to switch off genes that never need to be expressed in that tissue type. Our skin cells, for example, don’t need to express the proteins that are used to carry oxygen around in the blood. These genomic regions are completely inaccessible in the skin cells, curled up tight like an over-wound spring. But there are huge regions that aren’t in this hyper-condensed state and where genes are accessible and can potentially be switched on. In these sections the DNA is like the cooked pasta, like having the longest piece of tagliatelle in the world, filling an entire pot on its own. It bends and swirls in the cooking water, throwing out loops and arcs.

Figure 12.3 Simple schematic to show how folding of a flexible DNA molecule can bring two distant regions, such as an enhancer and a protein-coding gene, into close proximity to each other.

In this way, a protein-coding gene and its distant enhancer may come very close to each other. The long non-coding RNA and the Mediator complex then hold the two loops together and ensure that expression of the gene is driven up. Another complex also has to work with the Mediator complex to carry this out.* The additional complex is one that’s also required for separating duplicated chromosomes during cell division, so it’s well equipped for dealing with large-scale movements of DNA. Mutations in some of the genes that encode members of this additional complex cause two developmental disorders, called Roberts Syndrome and Cornelia de Lange syndrome.17 The precise features of the affected children can be quite variable, probably depending on the exact gene that is mutated, and the precise mutation in that gene. Typically, the children are born small and remain relatively undersized; they have a learning disability and frequently present with limb abnormalities.18

The extent of this looping mechanism is quite remarkable, and may not just be restricted to enhancers. It may also be used to bring other regulatory elements close to genes. In a study of three human cell types, analysing just 1 per cent of the human genome, researchers identified over 1,000 of these long-range interactions in each cell line. The interactions were complex, most frequently involving regions that were separated by about 120,000 base pairs. Often the regulatory region looped up to a gene that wasn’t the nearest one to it. In fact, in over 90 per cent of the loops, the nearest gene had been ignored. Think of this as needing to borrow a cup of sugar and visiting someone half a mile away instead of popping in to your next door neighbour.

And if we continue the neighbour theme, the relationships were outrageously promiscuous. Imagine a 1970s partner-swapping party on steroids. Some genes interacted with up to twenty different regulatory regions. Some regulatory regions interacted with up to ten different genes. These probably don’t all occur in the same cell at the same time. But what they show is that there is not a simple A to B relationship between genes and regulatory regions. Instead, there is a complex net of interactions, giving a cell or an organism an extraordinary amount of flexibility in how it regulates its overall tapestry of gene expression.19 Although there is still plenty to be unravelled about the networks and how they operate, it would appear that while the junk DNA that forms promoters switches on our genomic engines, it’s the junk DNA that forms long non-coding RNAs and enhancers that converts that engine from one powering a Sandero to one that can accelerate the Veyron down the freeway of life.

From cottage industry to the factory floor

Remarkable though the looping between individual regulatory regions and genes undoubtedly is, there is an even more dramatic set of long-range interactions that occur in cells. To understand the significance of this, a short social history lesson may be in order. In the early part of the 19th century in Britain, the bulk of all textile work was carried out as a cottage industry. Essentially, individuals worked in their homes on small-scale production. If you had mapped out the locations of textile production in a given region, you’d have a map with lots of individual dots on it, where each working cottage was located. Fast-forward about 50 years and into the Industrial Revolution and the same study would create a very different picture. Instead of a fairly homogenous dotted distribution, like a pointillist painting, you’d find a map with just a few large spots showing the location of big factories.

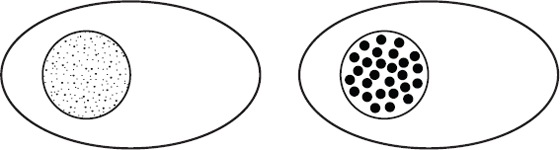

Even if we just think about the protein-coding genes, we know that thousands are typically switched on in a given human cell type. These genes are spread out across our 46 chromosomes, so we might expect that if we analysed a cell to visualise the geographical locations of the genes that are switched on we would see thousands of tiny dots spread throughout the nucleus. Instead, as shown schematically in Figure 12.4, there are about 300 to 500 larger spots.20 Gene expression in our cells isn’t a cottage industry. Instead it takes place in discrete locations in the nucleus known as factories.21

Each factory contains between four and 30 copies of the enzyme that makes a messenger RNA molecule from the DNA template, plus a large number of other molecules required to do the work.22,23 The enzymes stay in one place and the relevant gene is reeled through to be copied.24 In order for the gene to reach the factory, the DNA has to loop out to reach the right part of the cell nucleus. But the really ingenious bit is that more than one gene can be copied into messenger RNA at a time in the same factory. The combination of genes found in a single factory isn’t random. The genes tend to be ones that code for proteins that are used for related functions in the cell. This is equivalent to having multiple parallel assembly lines in one physical factory. Once all the lines have completed their individual tasks, the factory can assemble the final product from the components. One factory produces boats, another builds food mixers. In our cells, the factories ensure that genes are expressed in a coordinated fashion. This means lots of loops unfurling from chromosomes and localising to the same regions of the nucleus simultaneously.

Figure 12.4 The dots represent the positions of protein-coding genes in the nucleus. If genes were positioned in the nucleus solely as a function of their position on chromosomes, we would see a diffuse pattern such as the one on the left. Instead, genes cluster together in three-dimensional space, creating a punctate pattern of gene localisation represented by the situation on the right.

One example of this is a factory for the genes that code for the proteins required to create the complex haemoglobin molecule, which carries oxygen around in the blood.25 Another factory is used to generate the proteins required in order to mount a strong immune response.26 One important component of an effective immune response is the production of proteins called antibodies. Antibodies circulate in the blood and other body fluids, binding to any foreign matter that they detect. Scientists activated the cells that produce antibodies and then studied how certain key genes looped out. The genes they analysed were the ones required to create antibody molecules. They found that these key genes moved to the same factory as each other. Remarkably, some of these genes were completely physically separate from each other normally, as they are located on different chromosomes.

Although this is a remarkable way of coordinating gene expression, it may also carry risks. Burkitt’s lymphoma is the aggressive cancer we met earlier in this chapter. The cell type that becomes abnormal in this disease is the cell type that produces antibodies. In this condition, a strong promoter from one chromosome gets abnormally positioned next to a gene from another chromosome. Until recently we didn’t understand why these regions were susceptible to joining up, because we thought of them as being physically distant from each other, as they are on different chromosomes. But now we know that the regions that ‘swap’ to create the dangerous abnormal hybrid chromosome are both regions that move to the factory described in the previous paragraph. This might be how the two different chromosomes get close enough together to swap their material, perhaps if both break simultaneously and are wrongly repaired when in the factory.

While it might seem that evolution would have selected against this dangerous situation, we need to remember yet again that natural selection is about compromise, not perfection. The advantages of producing antibodies to fight off infections and thereby keep us alive long enough to reproduce clearly outweigh the potential disadvantages of an increased cancer risk.