The ENCODE consortium identified a daunting abundance of potentially functional elements in the human genome. Given the huge numbers, it’s hard to define a sensible strategy for deciding which candidate regions to experiment on first. But the task may not be quite as difficult as it seems, and that’s because, as always, nature has decided to point the way. In recent years scientists have begun to identify human diseases that are caused by tiny changes to regulatory regions of the genome. Previously, these might have been dismissed as harmless random variations in junk DNA. But we now know that in some cases just a single base-pair change in an apparently irrelevant region of the genome can have a definite effect on an individual. In rare cases, the effect is so severe that life itself is impossible.

We’ll start with a less dramatic example, but one that takes us back about 500 years, to the reign of King Henry VIII in England. Most British schoolchildren are at some point taught a useful rhyme to help them remember what happened to the six wives of this notorious monarch:

Divorced, beheaded, died,

Divorced, beheaded, survived.

(Feel free to send a thank-you email when this handy little ditty helps you in a quiz.)

The first wife to be beheaded was Anne Boleyn, the mother of the future Queen Elizabeth I. After her death, the Tudor spin doctors launched quite a smear campaign and Anne Boleyn’s physical appearance was described in such a way that she sounded like the 16th-century image of a witch. She was characterised as having a projecting tooth, a large mole under her chin and six fingers on her right hand. The story of that extra finger has passed down in folklore, although there is little if any evidence that it was true.1

Perhaps one of the reasons that the story has been accepted is because it’s not completely ludicrous. It’s not as if the chroniclers claimed that the former queen had three legs. There are people who are born with an extra finger, although usually they have an extra finger on each hand rather than just one.

There is a protein-coding gene that is very important in the correct development of the hands and feet.* The protein acts as a morphogen, meaning that it governs patterns of tissue development. The effects of the protein are very dependent on its concentration, and in the developing embryo there is a gradient effect, where high levels in one region gradually fade away to lower levels in adjacent tissues.

Mittens and kittens

One of the features controlled by this morphogen is the number of fingers. If the expression levels of the protein are wrong, babies are born with extra fingers. Over ten years ago researchers discovered that some cases of extra fingers were caused by a tiny genetic change. This wasn’t in the morphogen gene, but in a region of junk DNA about a million base pairs away. They identified the change in a huge Dutch family where the presence of extra fingers was clearly inherited as a genetic trait. All 96 affected individuals had a change of just one base in the junk. Instead of a C base, these patients had a G base. None of the relatives with the normal number of digits had a C in this position. Single base changes were also found in other families where some individuals had extra fingers. These changes were in the same general region of the genome as in the Dutch family but 200–300 base pairs away from that alteration.2

The junk region that carries these single base changes is an enhancer of the morphogen gene.* In order to create the correct body pattern, the spatial and temporal control of the morphogen is very tightly controlled by a whole slew of regulators. In the people with the mutation and the extra digit, the enhancer activity was slightly abnormal. The impact of the tiny change in this one regulator shows just how important and finely tuned this control is.

Here’s some help with another quiz. What’s the connection between Dutch people who have trouble buying gloves, and one of the great figures of 20th-century American literature? No? Give up? Well, in the 1930s Ernest Hemingway was given a cat by a ship’s captain. Instead of having five toes on its front paws, this cat had six. There are now about 40 descendants of this cat at Hemingway’s home, about half of whom have six toes on their front paws. It’s easy to find pictures of these cats on the internet3 and they are simultaneously cute and a little bit scary. The extra toe looks like a thumb, rendering the cats slightly too capable-looking for comfort.

The same group that identified the change in the enhancer region in humans with extra fingers showed that the same region was altered in Hemingway’s cats. By inserting the enhancer into another animal’s genome they confirmed that the alteration changed the expression of the morphogen. The experimental animal over-expressed the morphogen and developed an extra digit on each front paw. Rather delightfully, this effect was demonstrated by inserting feline DNA into a murine embryo. A genuine cat-and-mouse game.4

Cats with extra front paw toes have also been found in other countries, including the UK. In the British cats there is also a change in the same enhancer, but it’s not exactly the same change. It is two base pairs away from the Hemingway change, in a three-base-pair motif that is very highly conserved in evolution. The enhancer region that is involved in the extra digits on the forelimbs of humans and cats is about 800 base pairs in length and most of it is highly conserved from humans all the way down to fish. This suggests that the control of limb development is a very ancient system.

Morphogens and facial development

The morphogen that is responsible for finger formation is also critical for other developmental processes. One of these is the process whereby the structures of the front of the brain and the face are formed. If this process goes wrong, the effect can be very mild: simply a cleft lip. But at the other extreme, where the morphogen expression is more severely disrupted, the effects can be devastating. The brain and face may be completely abnormal, with no proper formation of brain structures. In the most severe cases the babies are born with just one malformed eye in the middle of the forehead and with severely impaired brain development. The babies never survive.

This spectrum of condition is known as holoprosencephaly.5 A number of different protein-coding genes has been shown to be mutated in different families with this condition. Many of these genes are involved in the regulation of the same morphogen that is required for correct digit formation. In some cases, the gene for the morphogen protein itself is mutated. The developing embryo only produces half of the normal amount of the morphogen, because the functional protein is only produced from one chromosome, not two. The abnormalities in the affected individuals show that it is critical that the morphogen levels hit the right thresholds at key points in development.

Not all the mutations that cause holoprosencephaly have been identified. Researchers studied the DNA from nearly 500 individuals who were affected by the condition. They found an unexpected change in a junk DNA region of one severely affected infant. This was a single base change, from C to T, in a region over 450,000 base pairs away from the morphogen gene.6

The C to T change occurred in a block of ten base pairs that has been conserved since our ancestors diverged from the ancestors of frogs, over 350 million years ago. We can therefore surmise that this stretch of apparent junk has been maintained throughout evolution and has a function. In the case of this specific enhancer, the C binds a transcription factor protein.* Transcription factors are the proteins which are unusual because they recognise specific DNA sequences, usually in promoters, and bind to them. Binding of transcription factors to a promoter is essential for switching on a gene. The key transcription factor for this enhancer can bind to the ten-base-pair motif when the DNA contains a C in the appropriate position, but not when it contains a T.

This change from a C to a T in the enhancer wasn’t present in 450 unrelated healthy control individuals. That might make it seem very likely that this change was the cause of the problems in the patient, but it’s important to remember that it was also only seen once in about the same number of patients with the condition. The baby’s mother was unaffected, and as expected she had the normal C base on both her chromosomes. But unexpectedly, the baby’s father had the same genetic sequence at the enhancer as his child. One chromosome had a C at the relevant position and the other had a T in the same place. But the father was completely unaffected by any symptoms of holoprosencephaly.

Although this might seem like strong evidence against a role for this C to T change, the situation isn’t that straightforward. In holoprosencephaly it’s quite common that there are lots of differences in a family, even where the mutation that causes the symptoms is in the morphogen gene itself. Up to 30 per cent of the family members with the mutation have no symptoms at all, and in others the symptoms may vary a lot from person to person. The first situation is known as variable penetrance, and the second is referred to as variable expressivity.

Unfortunately, these are classic cases where biologists identify a phenomenon, give it a fancy technical name and then stop thinking about it. These phrases are used to describe the phenomenon but we forget that we really don’t understand why it is happening. It’s a fascinating area that remains poorly understood. It’s possible that there are other subtle sequence variations in the genome that compensate for the effects of the DNA change in some people. This could include other enhancers working more strongly, and boosting expression of the morphogen. There may also be epigenetic compensation in some people, which nudges the expression of key genes in a certain direction. It may be a combination of both these factors, plus others that we have not yet identified.

But where we have this uncertainty – parent and child with the same genetic change but different symptoms – it’s vital to develop additional lines of evidence to support any hypothesis about the impact of the variant base. The researchers who identified the C to T change in the enhancer did exactly this, by testing the effect of this change in a mouse model. They showed that when the C was present, this stretch of junk DNA acted as an enhancer of morphogen expression. But when the C was replaced by a T the region no longer acted as an enhancer, and levels of the morphogen never reached the critical levels in the brain.

Morphogens and the pancreas

The morphogen that is implicated in the development of extra digits or in the various forms of holoprosencephaly isn’t the only example of a human condition caused by a change in a regulatory region of DNA. There is a condition known as pancreatic agenesis, in which the pancreas fails to develop properly. Babies born with this condition often have severe diabetes.7 This is because the pancreas is the organ that produces insulin, the hormone that allows us to regulate the levels of sugar in our blood.

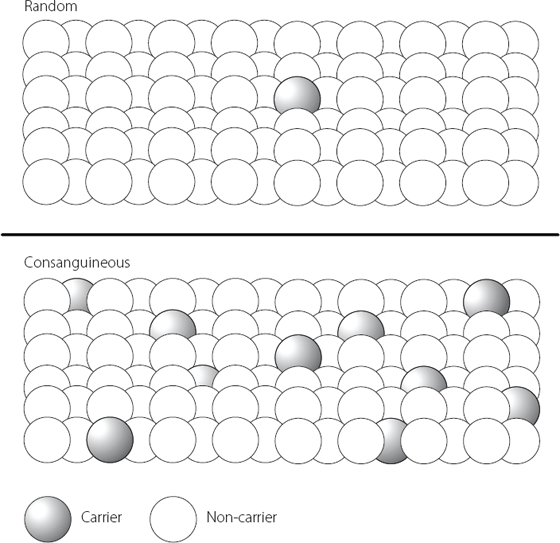

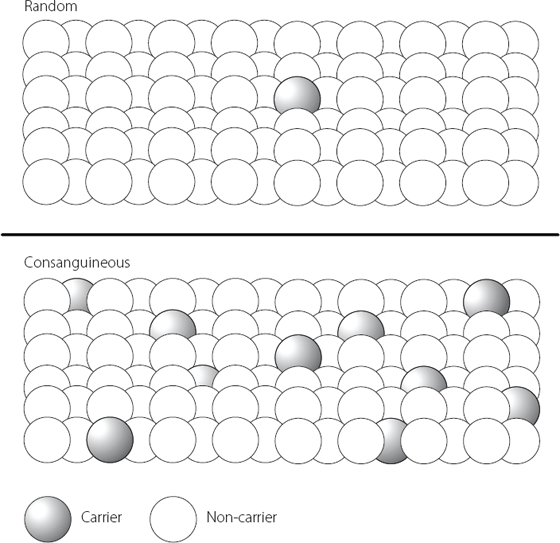

The majority of families with pancreatic agenesis have a mutation in one particular transcription factor*,8 but in a small number of affected families a different transcription factor is involved.**,9 However, there are many cases where a child is born with unexplained pancreatic agenesis, when no one else in the family has ever been affected. Normally we might think that these cases have appeared randomly, perhaps as the consequence of something going wrong in development in response to an unidentified stimulus in the environment. But it became clear that most of these apparently sporadic cases occurred in families where the parents of the affected child were related to each other, typically cousins. This is known as consanguinity. When consanguinity is associated with higher rates of a disorder, we normally look for a genetic change. The change will be one where both copies of a chromosome carry the same variation. The reason why these conditions are more common in consanguineous couples is shown in Figure 15.1.

Figure 15.1 The upper part of the figure shows how a person who carries a rare genetic mutation is statistically relatively unlikely to meet another person with the same mutation in the general population. In their own family, however, it is much more likely that someone else will also have inherited the same mutation – a situation illustrated in the lower part of the figure. This is why rare recessive disorders (where the parents are asymptomatic carriers with one mutant gene each) present more commonly when the parents are related, for example first cousins.

Researchers isolated DNA from patients with the sporadic form of pancreatic agenesis and analysed all the protein-coding regions. They were unable to find any variations in sequence that could explain the disease. So they turned their attention to predicted regulatory regions. There are, as we have seen, an awful lot of predicted regulatory regions in the human genome. In order to narrow down their search, the investigators studied what happens when stem cells differentiate into pancreas cells in culture. They looked for regulatory regions which carried epigenetic modifications normally associated with enhancer function, and which bound transcription factor proteins known to be important in the development of pancreas cells.

This narrowed the list of candidate regions to just over 6,000, a much more manageable number to analyse in depth. Four patients each had a change from an A to a G in a putative enhancer region of about 400 base pairs on chromosome 10. This region lay 25,000 base pairs away from one of the transcription factors that is known to be mutated in a small number of families with pancreatic agenesis. Seven out of ten unrelated patients all had the same change: the enhancer on both copies of chromosome 10 had a G where there is normally an A base. Two patients had other nearby mutations, and the tenth patient had lost the enhancer altogether. Nearly 400 unaffected people were analysed. None of them carried this A to G change.

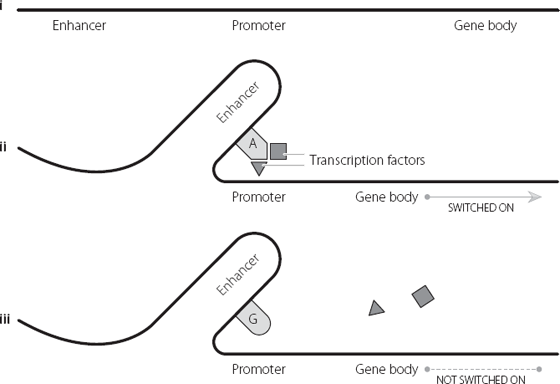

The researchers showed experimentally that the region they had identified acted as an enhancer in developing pancreatic cells, and also showed that the region loses its enhancer activity when the A is changed to a G. In further experiments, they explored how this enhancer regulates its target gene. This is shown in Figure 15.2. Briefly, the enhancer loops out so that it lies close to its target gene. The enhancer normally binds transcription factors which help to switch on the target gene. But transcription factors only bind to certain DNA sequences. When the A is changed to a G the transcription factors can’t bind, and so they can’t switch on their target gene.10

It’s a bit like going fishing. Drop a hook baited with a juicy worm into the lake, and a carnivorous fish will bite. Drop in a hook baited with carrot and there won’t be so much as a nibble. Everything else is the same – the hook, the line, the sinker, the fish. But changing just one critical component (the bait) dramatically alters the chances of a successful catch.

Figure 15.2 i shows the sequential positioning of an enhancer, promoter and gene body. In ii the DNA folds, bringing the enhancer close to the promoter. When the enhancer contains an A base in a specific position, the enhancer can bind specific proteins called transcription factors. These can activate the promoter and switch on the gene. In iii the A base in the enhancer is replaced by a G base, and the transcription factors can’t bind. This in turn means that they can’t activate the promoter, and the gene isn’t switched on.

Variations on a theme

It would be tempting to think that alterations in regions of junk DNA, which actually turn out to be regulatory regions, all have horrible consequences for the cell and the person. But that’s because it’s sometimes easier to look at abnormal situations than normal ones. This is especially the case if we are assessing the difference between having a disease and being healthy. In the cases described above, the single base changes in the regulatory regions have had dramatic effects. But these types of variations are also responsible for situations which are much less binary, and are just a normal part of human diversity.

Consider pigmentation. Pigmentation is a complex trait, by which we mean it is influenced by lots of genes acting together. The end results in this case are eye, hair and skin colour. We all know by experience that humans vary enormously with respect to these features of our appearance. In addition to several genes contributing to pigmentation levels, there are also different variants of those genes, creating additional potential for variation.11

One of the major variants is a single base difference, which occurs as either a C or a T. The T version is associated with higher levels of dark pigment, the C version with lower levels.* But this variation doesn’t lie in a protein-coding gene. It has been shown that the reason it affects pigmentation is because it is in an enhancer region, 21,000 base pairs away from the target gene. This target gene codes for a protein that is important for pigment production. We know this because mutations in this gene lead to a form of albinism where the affected individual can’t make pigment.12,**

It has been shown experimentally that the enhancer loops to the target. Transcription factors that control the target bind with greater or lesser efficiency depending on the C or T base.13 This is very similar to the situation outlined above for pancreatic agenesis, and uses pretty much the same mechanism as shown in Figure 15.2.

It’s quite likely that there are a lot of similar relationships between single base changes in junk DNA and the expression of protein-coding genes. This has implications for understanding human diversity and human health and disease. There are a large number of conditions where we know genetics plays a role in whether or not a person develops a disorder. In these conditions, a person’s genetic background influences their likelihood of suffering from an illness, but doesn’t explain it entirely. The environment also plays a role; as, sometimes, does plain bad luck.

We can identify disorders with a genetic contribution by looking at how often a disease occurs in a family. Twins are particularly useful in this analysis. Let’s look at Huntington’s disease, a devastating neurological disorder caused by a mutation in one gene. If one twin has the condition, their identical twin will also always have the disease (unless they die early from an unrelated cause, such as a traffic accident). Huntington’s disease is 100 per cent due to genetics.

But if we look instead at schizophrenia, we find that if one twin suffers from this condition, there is only a 50 per cent chance that their identical twin is also affected. This has been calculated by analysing lots of twin pairs and working out the frequency with which both twins develop the condition. This tells us that genetics contributes about half the risk for developing schizophrenia and the other risk factors aren’t due to the genome.

Researchers can extend these studies into other family members, because we know how much genetic information family members share. For example, non-identical siblings share 50 per cent of their genetic information, as do parents and children. First cousins share only 12.5 per cent of their genomes. It’s possible to use this information to calculate the contribution of genetics to a large range of conditions from rheumatoid arthritis to diabetes, and from multiple sclerosis to Alzheimer’s disease. In these conditions, and many more, genetics and environment act together.

If we can find enough families, we can analyse their genomes to identify regions that are associated with disease. But we have to remember that the data we generate will be very different from the simple situation we see with a purely genetic condition such as Huntington’s disease. In Huntington’s 100 per cent of the genetic contribution lies in one mutation in one protein-coding gene. But for a condition such as schizophrenia, the 50 per cent genetic contribution to the disease isn’t due to just one gene, and the same is true of most other conditions where both genetics and the environment play a role. There could be five genes each contributing 10 per cent of the risk for schizophrenia, or twenty genes each contributing 2.5 per cent of the risk. Or any other combination of which you can think. This makes it harder to identify the relevant genetic factors, and to prove that sequence changes really do influence the condition being studied.

Notwithstanding these difficulties, more than 80 diseases and traits have been mapped using these methods, generating thousands of candidate regions and variations.*,14 Remarkably, nearly 90 per cent of the regions identified across these studies are in junk DNA. About half are in the regions between genes, and the other half are in the junk regions within genes.15

Guilt by association

We have to be very careful about assuming that because we can detect a variation in DNA that is associated with disease, that this means the variation has a role in causing the disease. Sometimes we may just be looking at guilt by association. The genetic change that really contributes to the condition may be a different variation that is close by, and our candidate may just have been carried along for the ride.

An example of guilt by association would be cirrhosis of the liver. One way to assess exposure to cigarette smoke is to measure the levels of carbon monoxide in a person’s breath. Ten years ago, if we measured the levels of this gas in the breath of non-smokers with liver disease we might find that there were higher concentrations of this gas in the airways of people with the condition than without, on average. One interpretation (although not the only one) would be that passive smoking increases the risk of liver cirrhosis. But in reality, the carbon monoxide levels are a case of guilt by association. They probably just reflect that the patient may spend a lot of time in pubs and bars, because excessive alcohol consumption is a major risk factor for developing this illness. Until the introduction of smoking bans in many cities, pubs and bars were traditionally pretty smoke-filled environments.

Even if we exclude guilt by association when analysing the contribution of a genetic variation to a human disorder, we still need to be really careful to test hypotheses about the functional consequences of our findings. Otherwise, we can be badly misled.

The variation that contributes to human pigmentation that we met earlier in this chapter actually lies in the introns, the bits of junk DNA that lie in between the protein-coding parts of a gene, which we first met in Chapter 2. The gene is very big, and the variant base pair is in the 86th stretch of junk DNA between amino acid-coding regions. But this gene itself plays no role in control of pigment levels. So we have clear precedent for accepting that variations in the junk regions in one gene may be important for effects on other genes.

Obesity is one area in which there has been a great deal of interest in identifying genetic variants linked to physical variation. Nearly 80 different regions in the human genome have been associated with obesity or with other relevant parameters such as body mass index.16

In multiple studies, the variation showing the greatest association with obesity was a single base pair change in a candidate protein-coding gene on chromosome 16.*,17,18 Individuals who inherited an A on both copies of this gene tended to be about 3kg (6.6lb) heavier than individuals who inherited a T on both copies. This change was in the junk region between the first two amino acid-coding stretches of the candidate gene. The fact that this association was detected in more than one study was important as this increases our confidence that we are looking at a meaningful event.

It seemed that a consistent story was developing, because experiments in mice seemed to confirm a role for this gene in control of body weight. Mice that were genetically manipulated so that they over-expressed this gene were overweight, and developed type 2 diabetes symptoms when they ate a high-fat diet.19 When this gene was knocked out in mice, the animals had less fat tissue and a leaner body type than control mice. Even when the knockout mice ate a lot, they burnt loads of calories, even though they weren’t particularly active.20

This created a lot of excitement. It implied that if scientists could find a way to inhibit the activity of this gene in humans, they might be able to develop an anti-obesity drug. There was still a problem because we aren’t altogether sure what the candidate gene does in cells, and that makes it difficult to create good drugs. But at least we had a starting point. Both the human and mouse data implied that the gene coded for an important protein in obesity and metabolism. This was coupled with the reasonable assumption that the variant base pair associated with obesity affected the expression of the gene itself.

But in the immortal words of Mitch Henessey, the character played by Samuel L. Jackson in The Long Kiss Goodnight, ‘Assumption makes an ass out of “u” and … “umption”.’ Of course, hindsight is always 20/20 and there’s no reason to feel condescending to the scientists who were exploring the role of the protein. It’s just that nature seems to have a way of tripping us up.

Here’s the real reason why that single base pair variation makes a difference to human physiology. There’s another protein-coding gene half a million base pairs away from the key single base pair change described above.* The junk region of the original gene interacts with the promoter of the second gene, altering its expression patterns. Essentially, the junk region acts as an enhancer. The effect is seen in humans, mice and fish, suggesting it is an ancient and important interaction.

The investigators looked at the expression levels of this second gene in over 150 human brain samples. There was a clear correlation between the base pair variant in the junk/enhancer region and the expression levels of the second gene. But there was no correlation between the base pair variant and the expression levels of the original candidate, the gene that actually contains the variation.

When the researchers knocked out expression of the second gene in mice they found that, compared with control animals, the mice were lean, had low adipose tissues and increased baseline metabolic rate. This was in fact the first time anyone realised that the second gene was involved in metabolism at all.21

What we have here is a model very similar to the one we have already encountered for human pigmentation and for pancreatic agenesis. There are in fact a number of different variant base pairs in the junk region of the original obesity-associated gene. Many of these have been associated with obesity. This suggests that all of these variants probably have the same effect, i.e. they change the activity of the enhancer, and thereby alter the expression levels of the target gene, half a million base pairs away.

Of course, the mouse data suggest that the original gene, the one that contains the variations in its junk DNA, may also play a role in obesity and metabolism. So we could ask if, in practical terms, it really matters how the single base pair changes bring about their effects. But there is a way in which this matters a lot, and that’s in the field of drug discovery.

One of the many problems in developing new drugs is that frequently some patients will respond to a drug and others won’t. This adds a lot of additional expense. It means that pharmaceutical companies have to run very large clinical trials to see if their drug works, because they have to test it in all-comers. It also means that it’s expensive to use the drug in clinical practice, because the doctor will give it to all patients with the relevant condition, but it will only work in some of them.

These days, pharmaceutical companies are all trying to create something called ‘personalised medicine’. This means that they try to develop drugs for situations where they know very early on which patients they want to treat, usually based on their genetic background. This can be very effective. It means drugs cost less money to develop, are usually licensed faster, and are only given to patients who are likely to benefit. This is an advantage for the health care providers because they aren’t wasting money treating people who won’t respond. It’s also potentially better for the patients, as all drugs have possible side effects, and there’s no point having the risk of side effects if there is very little likelihood of receiving benefit.22 There have been real successes in this approach, most notably in drugs for breast cancer,23 a blood cancer24 and most recently lung cancer.25

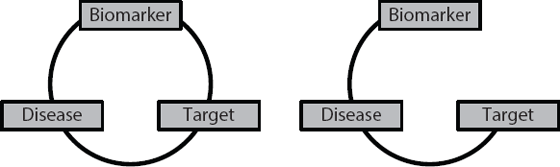

The critical step in developing personalised medicines is to identify a reliable biomarker. The biomarker tells you which of your potential patients should respond to your drug. Ideally, you want a situation where 100 per cent of people with the relevant biomarker will respond to the drug. The problems start if you have the right biomarker for the disease, but you link it with the wrong target. You will create a drug and then be stuck wondering why patients who ‘should’ respond, don’t. It will be because there is a break in the circle of relationships, as shown in Figure 15.3.

Figure 15.3 On the left-hand side there is a perfect relationship between the biomarker, target and disease. On the right-hand side there is no relationship between the target and the presence or absence of the particular biomarker. Under these conditions the biomarker is useless for predicting which patients with the disease will respond to a drug developed against the target.

The potential market for obesity drugs is, with no pun intended, huge. It’s likely some companies had already started drug discovery programmes against the original target, which they will now be either terminating, or trying to find a way to salvage. In the meantime, portion control and a bit of exercise remain our best bet.