There are few crimes lower than deliberately hurting a child. In many countries, staff in emergency departments are trained to look for patterns of unexplained injuries including fractures in babies and toddlers. Often such a medical history will result in children being taken into care, little or no parental access, and ultimately prosecution and possibly imprisonment of one or both parents.

Protection of a child is of course paramount. But imagine the nightmare for parents if this happens to them and they are entirely innocent, because the fractures are due to an undetected medical condition.1 Although the number of such miscarriages of justice is small compared with genuine cases of child abuse, the effects for the family are devastating. Loss of liberty, marital breakdown, social exclusion and, most heartbreakingly, the loss of parent–child contact.

A genetic condition can and has led to this misdiagnosis of child battery on more than one occasion. The disorder is called osteogenesis imperfecta, but it’s more commonly known as brittle bone disease.2 Patients with brittle bone disease suffer fractures very easily, sometimes from mild traumas that might not even cause much of a bruise in a healthy child. The same bones may break repeatedly, and they may heal imperfectly, so that the affected person becomes increasingly disabled over time.

We might think that this condition should be very recognisable, making it rather strange that parents are sometimes wrongly accused of hurting their children. But there are a number of factors that complicate the picture. The first is that brittle bone disease affects about six or seven children in 100,000. A doctor may simply have never encountered the condition, especially if they are relatively new to emergency medicine. But sadly, they probably will encounter child battery and so are more likely to have this as a default diagnosis.

The diagnosis is also complicated because there are at least eight different types of brittle bone disease, varying in their severity and the fine details of the presentation. At the most extreme, babies may suffer fractures even before they are born. The different forms of brittle bone disease are caused by mutations in different genes. The most common ones are defects in collagens, proteins that are important for making sure bones are flexible. Although we often think of bones as very rigid, it’s important that they have some flexibility, so that they bend rather than break in response to movement. It’s the same principle behind why we teach children not to climb on dead trees, because the inflexible, dried-out branches are more likely to break than the green, bendy limbs of living trees.

In most cases of brittle bone disease, only one copy of a gene is mutated. The other copy (because we inherit a copy from each parent) is fine. But having one normal copy isn’t enough to compensate for the effects of the ‘bad’ gene. Usually when this happens we expect to see a disorder in not just the child, but also in one parent. This is the parent who passes on the condition to their baby. But if the mutation is a new one, created during the production of eggs or sperm, a child can be affected without their parent having any symptoms. This tends to be particularly the case in the very severe forms of brittle bone disease. This makes it harder for doctors in an emergency room to recognise that they are looking at a condition caused by a mutation.

But if doctors do suspect that a baby may be suffering from brittle bone disease, they can order genetic tests to try to confirm their diagnosis. The genetic diagnosis will involve analysing the sequences of the genes that are known to be mutated in brittle bone disease. Scientists will prioritise the order in which they sequence the genes by looking at the details of the patient’s symptoms, and deciding which form of brittle bone disease they think they have. Then they’ll sequence the most likely genes first, looking for mutations that alter the proteins required for strong healthy bones.

This usually works well. But inevitably we find that there are some patients with all the symptoms of brittle bone disease but who don’t have any mutations that alter the amino acid sequence in the proteins known to be involved in this condition. This is exactly the situation that faced scientists trying to understand the cause of a specific class of brittle bone disease* in a small number of Korean families. In this class of cases, there are characteristic patterns of fractures, but also a very strange after-effect. When the bones are damaged, either by a fracture itself or by medical intervention to repair a break, the patient’s body responds in an unusual way. It lays down too much calcium around the injury site, creating an obvious cloudy effect visible on an X-ray.

At the same time, other researchers were analysing a child from a German family, who had the same highly unusual type of brittle bone disease. Remarkably, the cases in both Korea and Germany were caused by exactly the same mutation. Just one base pair among the 3 billion the affected children inherited from each parent was altered. And the alteration that caused this disease was not in the amino acid-causing region of a gene. It was in junk DNA.

The beginning and the end

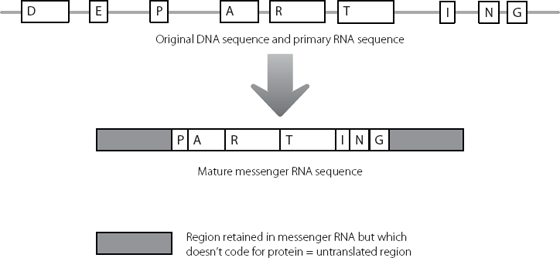

The mutation lay in a region of junk we have already encountered. In Chapter 2, we saw how protein-coding genes are composed of modules. The modules are initially all copied into messenger RNA and various modules are joined together. Regions that don’t code for protein are removed during this ‘splicing’ process (see page 16).

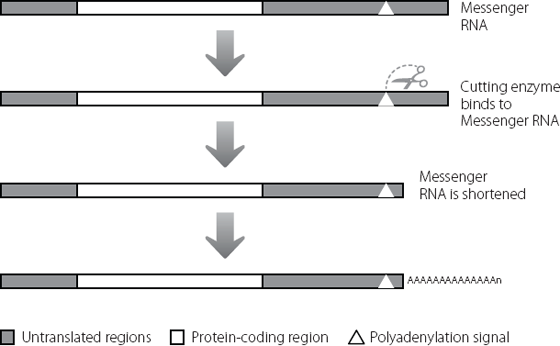

But two regions of junk DNA always remain in the mature messenger RNA. These were shown in Figure 2.5 and Figure 16.1 depicts them again. Because these regions at the beginning and end of the messenger RNA are retained but never translated into protein, they are known as untranslated regions.* Although they don’t contribute to the amino acid sequence of the normal protein, researchers are identifying new ways in which these untranslated regions contribute to protein expression and to human health and disease.

The researchers in Korea analysed the DNA sequences of nineteen patients. Thirteen of these came from three affected families, and the other six were single cases. Each of the nineteen patients had a change from a C base to a T base in the untranslated region at the start of the protein-coding region of a specific gene.* This change was just fourteen bases away from the start of the protein-coding region of the messenger RNA. They didn’t detect this C to T change in any of the unaffected family members or in 200 unrelated people from the same ethnic background.3

Figure 16.1 Even after the amino acid-coding regions of a messenger RNA have been spliced together, there is still some junk RNA which is retained in the molecule, at the beginning and end.

At about the same time, the researchers 5,000 miles away in Germany found exactly the same mutation in a young girl with the same type of brittle bone disease, and in another unrelated patient. In both cases, it was a fresh mutation. It wasn’t present in the parents and must have arisen during the production of eggs or sperm.4 The scientists analysed the same region of the genome from over 5,000 unaffected people and found no one with this change.

There is a bit of a puzzle when we look at our image of messenger RNA in Figure 16.1. In the diagram the protein-coding regions and the untranslated regions have been drawn so that they look different from each other. But this isn’t what they are like in the cell. In reality, they look the same at the sequence level, because they are just formed from RNA bases.

For anyone fluent in written English, the following is pretty easy to decipher:

Iwanderedlonelyasacloud

Even though all the letters have been run together, we can recognise where individual words start and stop. The same is true for the cell, which is able to tell the difference between the sequences in the untranslated regions and in the amino acid-coding regions of a messenger RNA.

Translation of messenger RNA to create protein is carried out at the ribosomes, in a process that we met in Chapter 11. The messenger RNA is fed through the ribosome, starting at the beginning of the messenger RNA molecule. Nothing much happens until the ribosome reads a particular three-base sequence, AUG (as mentioned in Chapter 2, the T base in DNA is always replaced by a slightly different base called U in RNA). This signals to the ribosome that it’s time to start joining up amino acids to create a protein.

Using our example from above, it would be as if we looked at a piece of text that read as:

dbfuwjrueahuwstqhwIwanderedlonelyasacloud

The capital I acts as the signal to us to start reading proper words, fulfilling a similar purpose to the AUG that signals the start of translation.

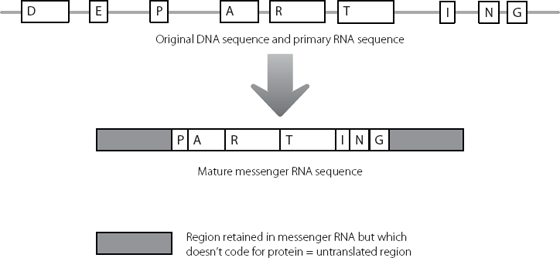

In the genes of the Korean and German patients with brittle bone disease, there is a point at which the normal DNA sequence in the untranslated region changes from ACG to ATG (which will be AUG in RNA). The consequence is that the ribosomes start the protein chain too early. This is shown in Figure 16.2.

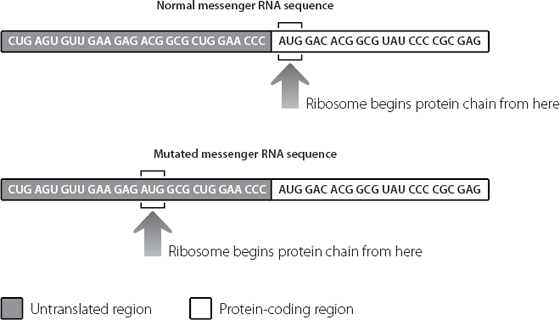

This results in a strange phenomenon where junk RNA is changed to protein-coding RNA. This adds an extra five amino acids to the start of the normal protein, as shown in Figure 16.3. The protein involved in this type of brittle bone disease is one that has parts inside and outside the cell. The alteration in the junk DNA adds an extra five amino acids to a part of the protein that is outside the cell.

It’s not quite clear why these five amino acids cause the symptoms of the disease. Previous experiments in rodents had shown that too much or too little of this protein leads to defects in the skeleton, so it’s clear that having exactly the right amount of the protein is important.5 The extra five amino acids are on a part of the protein that we would expect might bind to other proteins or molecules that signal to the bone cells. It may be that having these extra five amino acids stops the mutant protein from responding properly, like putting chewing gum on the sensor of a smoke detector.

Figure 16.2 A mutation in the untranslated junk region at the beginning of the messenger RNA mis-directs the ribosome. The ribosome begins sticking amino acids together too early, creating a protein with an extraneous sequence at the beginning.

Figure 16.3 The U-shaped protein on the right has an extra five amino acids at the beginning, represented by stars. These extra amino acids probably influence which other molecules can interact with this protein.

Brittle bone disease isn’t the only human disorder caused by mutations in the untranslated regions at the start of a gene. There is a strong genetic component in about 10 per cent of cases of melanoma, the aggressive skin cancer. A mutation has been identified in some of these genetically driven cases that works in a very similar way to the problem in brittle bone disease. Essentially, a single base change in the untranslated region at the start of a gene creates an abnormal AUG signal in the messenger RNA. This again results in the ribosome starting the amino acid chain too early in the gene sequence. This creates a protein with extra amino acids at the start, which behaves in an abnormal way, increasing the chances of cancer.6

As always, we need to beware of seeing patterns from too little data. Not all mutations in the untranslated region at the start of a gene create new amino acid sequences. There is another type of skin cancer which is usually much less aggressive than melanoma. This is called basal cell carcinoma, and it too has a strong genetic component. A rare mutation was found in a father and his daughter, both of whom developed this kind of tumour.

The untranslated region at the start of a particular gene usually contains the sequence CGG, repeated seven times, one after the other. The affected father and child had an extra copy of the CGG. Having eight repeats rather than seven predisposed them to basal cell carcinomas. This mutation didn’t change the amino acid sequence of the protein encoded by the gene. Instead, the extra three bases seemed to change the way the messenger RNA was handled by the ribosome, in ways that aren’t very clear. The end result was that the cells of the patients expressed much less of the specific protein than normal.7

Cancer is a multi-step disease, and although these mutations in the untranslated region at the start of certain genes predisposed the patients to tumours, other events probably also took place in the cells before full-blown cancer developed.

In the beginning was the mutation

But we have already encountered a disorder where an inherited mutation in the untranslated region at the start of a gene leads directly to pathology. This is the Fragile X syndrome of mental retardation (see page 19). As a reminder, the mutation is an unusual one. A three-base-pair sequence of CCG is repeated far more times than it should be. Anything up to 50 copies of this repeat is considered to be in the normal range. Fifty to 200 copies is not normally associated with disease, but once the number of repeats gets into this range it becomes very unstable. The machinery that copies DNA for cell division seems to have trouble keeping count of the number of repeats, and even more repeats get added. If this happens in the gametes, the resulting child may have many hundreds or even thousands of the repeats in their gene, and they present with the Fragile X syndrome.8

The longer the repeat, the lower the expression of the Fragile X gene. As we saw in an earlier chapter, this is because of cross-talk with the epigenetic system (see page 123). Where C is followed by G in our genome, the C can have a small modification added to it. This is most likely to happen in regions where this CG motif is present at high concentrations. The large number of CCG repeats in the Fragile X expansion provide exactly this environment. The untranslated region in front of the Fragile X region becomes very highly modified in the patients, and this switches the gene off. Fragile X patients don’t produce any messenger RNA from this gene, and consequently don’t produce any protein from it either.

The effects on the patient of this lack of protein are dramatic. Patients are intellectually disabled but also have symptoms reminiscent of some aspects of autism, including problems with social interactions. Some patients are hyperactive, and some suffer from seizures.

This of course makes us wonder what the protein normally does. The clinical presentation is quite complex, which suggests that the protein is probably involved in complicated pathways, and this indeed seems to be the case.

As we saw in Chapter 2, the Fragile X protein is usually complexed with RNA molecules in the brain. The protein targets about 4 per cent of the messenger RNA molecules expressed by the neurons.9 When it binds these messenger RNA molecules, the Fragile X protein acts as a brake on their translation into proteins. It prevents the ribosomes from producing too many protein molecules from the messenger RNA information.10

This extra level of control on gene expression seems to be particularly important in the brain. The brain is an extraordinarily complex organ, and the cell type that is of most interest to us is the neuron. This is what people usually mean when they talk about brain cells. There are an awful lot of neurons in the human brain, the most recent estimate being just over 85 billion.11 Each brain contains twelve times as many neurons as there are people on earth. And in the same way that people have complex networks of friends, acquaintances, lovers, families and enemies, neurons are also linked in. What’s startling is the degree of connection between the billions of neurons. Neurons send out projections that connect with other neurons in vast networks, constantly influencing each other’s responses and activities. The precise number of connections is really difficult to estimate, but each cell probably makes at least 1,000 connections with other neurons, meaning our brains contain at least 85 trillion different contact points.12 It makes Facebook look positively parochial.

Establishing these contacts appropriately is a huge task in the brain. Think of it as arranging to see good friends frequently while trying to avoid the weird guy you met in your first week at college. Contacts are set up and then either strengthened or pruned back, in complex responses to environment and to activities of other neurons in the network. Many of the target messenger RNAs that bind to the Fragile X protein under normal conditions are involved in maintaining the plasticity of the neurons, allowing them to strengthen and prune connections as appropriate.13 If the Fragile X protein isn’t expressed, the target messenger RNAs are translated into protein too efficiently. This messes up the normal plasticity of the neurons, leading to the neurological problems seen in the patients.

Researchers have recently shown that they can use this information to treat Fragile X syndrome, at least in genetically engineered animals. Mice which lack the Fragile X protein have problems with their spatial memory, and with their social interactions. A mouse that can’t find its way around and doesn’t know how to react to its fellow mice is a rodent that won’t last long. Researchers used these mice and applied genetic techniques to dial down the expression of one of the key messenger RNAs that would normally be controlled by the Fragile X protein. When they did this, the scientists detected marked improvements in the animals. Spatial memory was better and the mice behaved appropriately around other mice. They were also less susceptible to seizures than the standard Fragile X mouse models.

These symptomatic improvements were consistent with underlying changes that the scientists detected in the brains of the animals.14 Neurons in normal brains have little mushroom-shaped spines that are characteristic of strong, mature connections. The neurons of humans and mice with Fragile X syndrome have fewer of these, and a larger number of long, spindly, immature connections. After the genetic treatment, there were more mushrooms and fewer noodles.

The most exciting aspect of this was that it suggested it could be possible to improve neuronal function even after symptoms had developed. We can’t use the genetic approach in humans but these data imply that it is worth trying to find drugs that will have a similar effect, as a potential means of treating Fragile X patients. This syndrome is the commonest inherited form of mental retardation so the benefits of developing a treatment could be dramatic both for individuals and for society.

Now for the other end

As we saw at the start of this book, expansions in a three-base sequence at the other end of a gene can also cause a human genetic disease. The best-known example is myotonic dystrophy, which is caused by expansion of a CTG repeat in the untranslated region at the end of a gene. Repeats of 35 units or above are associated with disease, and the larger the repeat, the more severe the symptoms.15

Myotonic dystrophy is an example of a gain-of-function mutation. The main effect of the expansion in the Fragile X gene is to stop production of its messenger RNA. But this isn’t the case in myotonic dystrophy. The mutant version of the myotonic dystrophy gene is switched on, resulting in messenger RNA molecules with large expansions at the end of the molecule. It’s these multiple copies of CUG in the messenger RNA (remember that T is replaced by U in RNA) that cause the symptoms. If we turn back to Figure 2.6 (see page 23), we can see in outline how this happens. The expanded repeats act like a molecular sponge, soaking up particular proteins that are able to bind to them.

Junk DNA plays a remarkable role in myotonic dystrophy, as shown in Figure 16.4. The CTG expansion in the junk untranslated region binds abnormally large quantities of a key protein.* This protein is normally involved in removing the junk DNA that is found between amino acid-coding regions when DNA is first copied into RNA. Because so much of the protein is sequestered onto the expanded myotonic dystrophy untranslated repeat, it can’t carry out its normal function very well. Consequently, lots of RNA molecules from different genes aren’t properly regulated.

Figure 16.4 The excess binding of proteins to the expanded myotonic dystrophy repeat in the messenger RNA sequesters the proteins away from other RNA molecules that they should also be controlling. The other messenger RNAs are no longer properly processed, and this disrupts production of the proteins that they should be used to produce.

This titration of the binding protein, which occurs in any tissues where both it and the myotonic dystrophy gene are expressed, plays a large role in explaining why the disease can present so differently in different patients. Instead of being all-or-nothing, varying proportions of the binding protein may be ‘left over’ to regulate its target genes. The proportion will depend on the size of the expansion and the relative amounts of myotonic dystrophy messenger RNA and binding protein in a cell.16

It is worth looking in a bit more detail at the proteins that are ultimately affected by these deficits (proteins A, B and C in Figure 16.4). The best-validated ones are the insulin receptor,17 a heart protein18 and a protein in skeletal muscle that transports chloride ions across membranes.19 Insulin is required to maintain muscle mass. If the muscle cells don’t express enough of the receptor that binds insulin, they will start to waste away. The heart protein is one that we know is important for the correct electrical properties of the heart.20 Transport of chloride ions across skeletal muscle membranes is an important stage in the cycles of muscle contraction and relaxation. So, the defects in the processing of the messenger RNAs coding for these proteins are consistent with some of the major symptoms in myotonic dystrophy, i.e. muscle wasting, sudden cardiac death because of fatal abnormalities in heart rhythm, and the difficulty in relaxing a muscle after it has contracted.

Myotonic dystrophy is a great example of the importance of junk DNA in human health and disease. Although the mutation lies in the messenger RNA produced from a protein-coding gene, the mutation has little if any effect on the protein itself. Instead, the mutated RNA region is itself the pathological agent, and it causes disease by altering how the junk regions of other messenger RNAs are processed.

Say ‘AAAAAAAAA’

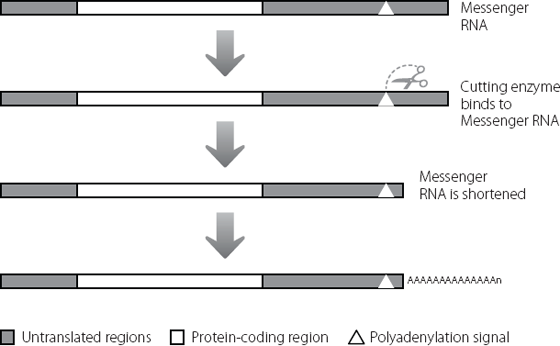

The untranslated regions at the end of protein-coding messenger RNAs have a number of functions in normal circumstances. One of the most important involves a process that affects all messenger RNA molecules. ‘Naked’ messenger RNA molecules can be broken down in a cell very quickly, via a process that probably evolved to help us get rid of certain types of viruses rapidly. In order to stop this happening, and to make sure the messenger RNA molecules linger long enough to be translated into protein, the messenger molecules are modified very soon after production. Essentially, lots of A bases are added to the end of the messenger RNA, by a process that is outlined in Figure 16.5. There are usually about 250 A bases on the end of a mammalian messenger RNA. They are important for stability and also for making sure that the messenger RNA is exported out of the nucleus where it is made and into the ribosomes where it is translated into protein.

Figure 16.5 A sequence in the untranslated region at the end of a messenger RNA attracts an enzyme (shown by the scissors) that binds at a specific site and then cuts the molecule a little further along. Lots of A bases are added to the cut end of the messenger RNA molecule, even though these were not coded for in the original DNA sequence.

There is a critical motif in the untranslated region at the end of the messenger RNA. This is shown by the triangle in Figure 16.5 and is called the polyadenylation signal (the A base is adenosine, so adding lots of A bases is called polyadenylation). This is a sequence of six bases (AAUAAA) within the junk of the untranslated region. It acts as a signal for a messenger RNA-processing enzyme. The enzyme recognises the six-base motif, and cuts the messenger RNA a little distance away, usually ten to 30 bases further downstream. Once the messenger RNA has been cut in this way, another enzyme can add the multiple A bases.*

This six-base motif often occurs many times in the same untranslated region. It’s not particularly clear how a cell ‘chooses’ which motif to use at any one time. It is probably influenced by other factors in the cell. But because there are multiple motifs that can be used, there may be multiple messenger RNAs that code for exactly the same protein, but which contain different lengths of the untranslated region before the multiple As. These different-length messenger RNAs will have different stabilities and so produce different amounts of protein from each other. This creates additional opportunity for fine-tuning the amount of protein that is produced.21

There’s a very unusual genetic condition in humans called IPEX syndrome.* It’s a fatal autoimmune disease in which the body attacks and destroys its own tissues. Cells lining the intestine are attacked, resulting in severe diarrhoea in young infants and a failure to thrive. The glands that produce hormones can also be attacked, leading to conditions that include type 1 diabetes, where patients can’t produce insulin. The thyroid gland may also be targeted, resulting in underactivity.22

Rare cases of IPEX syndrome are caused by a mutation in the polyadenylation signal. Instead of the normal AAUAAA sequence, there is a single base change. As a consequence, the six-base sequence becomes AAUGAA and no longer acts as a target for the cutting enzyme.23

The gene where this change occurs codes for a protein that switches on other genes.** This protein is required to control a particular type of immune cell.*** In some genes the change in a single six-base motif might not be that serious a problem, because the cell would use other, nearby, normal six-base sequences in the same untranslated region. This might disrupt fine-tuning a little, but we wouldn’t expect to see anything as severe as IPEX syndrome. The problem arises in IPEX because the untranslated region of this gene contains hardly any other suitable six-base motifs to act as signals for polyadenylation. The mutation in the untranslated region means that the messenger RNA isn’t cut properly, A bases aren’t added and the messenger RNA is very unstable. Because of this, the cells produce hardly any of this protein. Essentially, the effects of the mutation in this junk motif are as bad as if the protein-coding region itself had been disrupted.

It’s only fairly recently, as sequencing technologies have become cheaper, that researchers have really started analysing the untranslated regions of messenger RNA molecules to identify mutations that cause rare instances of serious diseases. We can be pretty confident that over the next few years we will see many more examples of this. One of the reasons we can be bullish about this prediction is that researchers may have already identified another such example.

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), also known as motor neuron disease or Lou Gehrig’s disease, is a devastating disorder. Neurons in the brain and spinal cord which control muscle movement die off progressively. Sufferers become increasingly wasted and paralysed, unable to talk, swallow or breathe properly.24 The cosmologist Stephen Hawking suffers from ALS, although his case is rather atypical. He was first diagnosed at the age of 21, whereas most people with ALS develop their first symptoms in middle age. Professor Hawking has survived for over 50 years with the condition, but sadly most patients die within five years of diagnosis, although this period may be increasing with better medical intervention.

There is much that we still don’t understand about ALS. Less than 10 per cent of cases run in families. In the other 90 per cent there may be variations in DNA that predispose someone to the condition if they encounter environmental triggers (which we can’t yet identify). Some patients may also have a mutation that is sufficient on its own to cause the condition, even without a family history of the disorder. This mutation may have arisen in the eggs or sperm of their parents, for example.25

One of the genes involved in ALS is believed to be responsible for 4 per cent of cases that run in families, and 1 per cent of cases that occur without a family history.*,26,27,28 In all the original cases involving this gene, the mutations were in the protein-coding regions. Researchers have now identified four different variants in the untranslated region at the end of this gene. These were found in patients with ALS who didn’t have any other known mutations. Although these could just be harmless variations, the distribution of the protein and its expression levels were abnormal in the cells from these patients. These findings are at least suggestive that the changes in the untranslated region led to abnormalities in the processing and translation of the protein itself, leading to disease.29