Exactly what drove the Ethiopians out of Arabia around 270 is just as obscure as what brought them there in the first place. Imperialist expansionism, probably nourished by a desire to control both sides of the Red Sea and the commercial traffic that sailed along it, would be a reasonable explanation of their arrival. But in any case by the end of the third century the Ethiopians were out of the territories of Saba and Ḥimyar in the southwest of the peninsula, which returned to the rule of their indigenous peoples. The names for the various regions varied, presumably as the centers of power reflected the places and cults of diverse Arab tribes. One region, in the Ḥaḍramawt, became known as Dhū Raydān, to indicate that it belonged to a pagan divinity called Raydān. This was not long before what is known today as the Kingdom of Ḥimyar with its capital at Zaphār emerged out of these various territories.1 It was this kingdom that the Ethiopians had occupied, and it was this kingdom that dominated the memory of the rulers in Axum after the Ethiopian withdrawal from Arabia.

As the Ethiopian kings consolidated their power in their East African homeland, they not only instituted mints for a coinage in all three metals, as we have seen, but arrogated titles that asserted sovereignty in the Arabian peninsula even though they no longer ruled there. They never forgot where they had been. In a spirit of both nostalgia and irredentism, the negus represented himself as “king of kings,” ruler over Axum and Ḥimyar, as well as over Dhū Raydān in the Ḥaḍramawt, and Saba in Yemen. He also made claims to sovereignty within East Africa at the borders of his own kingdom, and although these may have had more validity they cannot be verified. In the fourth century he had no hesitation in registering among his subjects many of the peoples that the anonymous king on the Adulis inscription proclaimed that he had conquered, including those he actually called Ethiopians (probably an allusion to the waning Meroitic kingdom), as well as Blemmyes and other peoples adjacent to Axum.

These royal assertions of sovereignty in the fourth century, echoing those at Adulis and including the phrase “king of kings,” appear considerably after Sembrouthes’ boast, from a century or more earlier, of being a “king from kings.” Although the expression “king of kings” is well known from the Persian monarchy, there is not the slightest reason to think that its appearance in Ethiopia was due to any direct influence from Persia, but the phrase had a certain currency in the eastern Roman Empire. The Pontic kingdoms of the time also had rulers who called themselves “king of kings.”2 This was when they were operating wholly outside the Persian orbit, and, in fact, most of the attestations of this title in the Pontic realms occur before the Sassanian Persians expelled the Parthian monarchy from its Iranian homeland in 224 AD. At Palmyra in the later third century “king of kings” even turns up for two local rulers at this powerful mercantile center in the Syrian desert. It cannot be excluded that the rulers in Axum were inspired indirectly by an awareness of the Sassanian fondness for the title shah-in-shah, or king of kings, but it seems far more likely that this expression arose locally in Ethiopia as a development from the phrase that Sembrouthes used when he declared himself to be a king from kings.

The extensive epigraphy of Aezanas, or ‘Ezana, reveals the full titulature of the negus in the fourth century. His inscriptions allow us to follow his career from the time when he was a great pagan ruler, claiming to be the son of the god Ares, who was equated with the Ethiopian Maḥrem, down to his later years as a devout Christian ruler who announced that he owed his kingship to God.3 The evolving titulature of Aezanas reflects the coming of Christianity to Axum.

The appearance of Christianity at the court did nothing to alter the irredentist claims of the negus, even as he transferred his allegiance from the traditional Ares (Maḥrem) to the newly adopted Christian God. The inscriptions of Aezanas imply clearly that his various texts all drew their inspiration from earlier royal documents of which the one on the Adulis throne is our sole surviving example. Aezanas is the most prominent of all the Axumite kings who reigned between the Adulis inscription and the sixth-century negus for whom Cosmas copied the inscriptions at Adulis when he was visiting the town. We shall see that Cosmas’ sixth-century king saw an opportunity to turn Aezanas’ hollow claims to Arabian territory into geopolitical reality. The first step in making this possible had been the conversion of Aezanas himself to Christianity.

Ecclesiastical legend, as preserved in the church historian Rufinus, attributed the Christianization of Axum to a certain Frumentius from Alexandria.4 A romantic story of his capture as a boy by Ethiopian pirates off the coast of East Africa, at a place presumed to be near Adulis, need not be believed, but the presence in Axum of someone by the name of Frumentius is securely documented in the Apology that Athanasius addressed to the Byzantine emperor Constantius II in 356. This was sent after one of Athanasius’ numerous expulsions from his seat as orthodox archbishop at Alexandria in direct consequence of hostility from the Arians. It is obvious from Athanasius’ carefully crafted Apology that Frumentius had been in Axum for a considerable period and was by that time bishop of a Christian community there that now included the king himself. The Apology quotes verbatim a letter that Constantius had sent to both Aezanas and his brother demanding that Frumentius, whom Athanasius had instructed for his bishopric, be returned to Alexandria for fresh instruction at the hands of the new Arian patriarch George.5 Apart from demonstrating Constantius’ hostility to Athanasius and to the orthodox creed he espoused, the emperor’s letter to Axum, as quoted in the Apology, leaves no doubt that he and perhaps Constantine before him had approved, or at least accepted, the Christianizing mission of Frumentius to the Ethiopians.

The date of the conversion of Aezanas is irrecoverable, but the suggestion of Stuart Munro-Hay that it had already happened by 340 is not unreasonable.6 It had certainly happened when Constantius II acquired sole power over the Mediterranean empire from 343 onwards, and it was only the exile of Athanasius in 356 that precipitated the demand for Frumentius’ return to Alexandria for new instruction in Arian theology. These doctrinal issues cannot be discerned in the language of Aezanas’ inscriptions that span the great divide from paganism to Christianity. But the conceptualization of the Axumite kingship as the gift of Ares (Maḥrem) and subsequently the Christian God is unambiguous.

It is by no means clear why Aezanas, even as a pagan ruler, appears to have been so much more loquacious on stone than most of his forebears. But the aggressive tone of his documents unmistakably reveals an ambitious ruler with an ambitious agenda. The inscribed stones he left behind are large rectangular blocks. The excavators who worked at Axum during the German archaeological expedition to the site in the early years of the twentieth century believed that many of these large, inscribed slabs were, as appears likely for some stones conveying Aezanas’ achievements in different scripts, the side-pieces on commemorative thrones. Some thirty bases for thrones of this kind survive.7 In other words, they would be closely parallel in design to the inscribed stones that comprised the throne that Cosmas saw at Adulis. It is even possible that many of Aezanas’ inscriptions served this purpose, and the evident duplication of one of the most remarkable inscriptions from his pagan years would best be explained by the existence of two separate thrones for them.

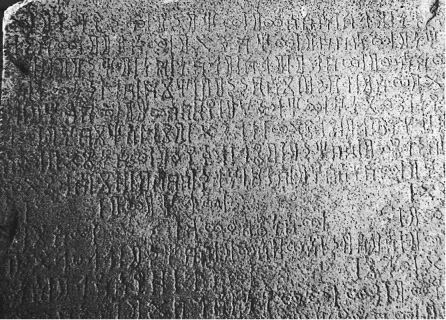

This pagan inscription is found on two unconnected stones at Axum with the same inscribed texts cut on both faces. The first and best known of these two stones was seen and copied in part by H. Salt in 1805. Subsequently, Theodore Bent saw it and made squeezes, and in 1906 the Germans copied and photographed all the texts on this stone, and also made impressions on paper (“squeezes”) for future reference.8 The writing on one face is Greek, but on the other Ge‘ez, written twice but in different scripts. The upper text is in Sabaic musnad script, going from right to left, and the lower text is in unvocalized Ethiopic, going from left to right. There are thus three versions of the text on a single slab, one in Greek and two in Ge‘ez (though in different scripts). Amazingly, in 1981 another stone turned up at Axum with the very same texts inscribed in the same two languages, and again with two different scripts for the Ge‘ez (Fig. 3).9 The newly discovered stone clarified points that had previously been unclear on the earlier stone because of substantial erosion.

All three texts are presented as the words of Aezanas himself, called “king of the Axumites, Homerites (Ḥimyarites), Raydān, Ethiopians, Sabaeans, Silene, Siyamo, Beja (Blemmyes), and Kasou.” After next declaring himself a “king of kings” and, in the Greek a son of Ares, or in the Ge‘ez a son of Maḥrem, he says that he sent his brothers Saiazanas and Adiphas to make war against the Blemmyes to the north of his kingdom. Aezanas furnishes a detailed account of the terms of submission of these peoples and expresses his gratitude by means of offerings “to him who brought me forth, the invincible Ares (or Maḥrem).” A royal text in Greek is hardly surprising in view of the consistent use of Greek on the Ethiopian coinage, nor is it surprising to find a text in Ethiopic letters inasmuch as this was the local script for the Ge‘ez language. But it is far less obvious what Aezanas had in mind when he had the same text inscribed in Ge‘ez in the Sabaic musnad of South Arabia. It is true that the Ethiopic letters were derived from Sabaic letters, but they were by now substantially different and were normally written from left to right, as Sabaic writing was not. The Ge‘ez in Sabaic script does include a few minor variations from the vocabulary in Ethiopic, most conspicuously in the first two lines where the word king appears in Sabaic as mlk, but in Ethiopic as ngś. Furthermore, the Sabaic text of the Ge‘ez preserves the Sabaic mimation (the addition of the letter mim at the end of nouns), which is conspicuously absent in Ethiopic.

Figure 3. Inscription at Axum, commemorating the achievements of Aezanas in classical Ethiopic (Ge‘ez), written in South Arabian Sabaic script. The text appears in RIE Vol. 1, no. 185 bis, text II, face B, p. 247. Photo courtesy of Finbarr Barry Flood.

We can watch the process of Aezanas’ ultimate conversion to Christianity played out in the texts of two other public inscriptions, one in Ge‘ez that has been known since 1840, and another in Greek, first published in 1970 but closely related in time and substance to the Ge‘ez text. The Ethiopic script (fīdal) of the Ge‘ez inscription appears with full vocalization and begins with the highly innovative prefix, “In the power of the Lord of Heaven, who is victorious in heaven and on earth for me, I Aezanas …”10 The speaker’s name, filiation, and titles follow, including claims to the kingship of both Axum and Ḥimyar in Arabia and Salhēn and Beja (the Blemmyes) in East Africa. He goes on a few lines later to declare, “In the power of the Lord of all, I went to war against the Noba when the peoples had rebelled and boasted of it …, In the power of the Lord I made war by the river Atbara at the ford Kemalke, and they fled.” The Ge‘ez word for river here (takazi) functioned as a proper name for the Atbara that linked with the Nile above the fifth cataract. Some thirty lines on Aezanas declares, “I set up a throne at the confluence of the rivers Nile and Atbara” as a tangible commemoration of the victories he describes. Towards the end of the same inscription Aezanas again invokes the Lord of Heaven in gratitude for having given the king his rule by destroying his enemies, and he beseeches Him to strengthen it. By setting up the throne at Axum, as well as on the Nile where it joined the Atbara, the negus is following a custom that had, as the Adulis throne exemplifies, deep roots in the pagan past. Aezanas attributes his successes to the Lord of Heaven (or sometimes simply Lord), but no longer to any pagan deity.

At the end of the inscription Aezanas declares that his Lord is the one “who made me king and the earth that bears it [the throne].” This last phrase has been thought to be a faint echo of pre-Christian consecrations of a votive throne to Maḥrem. But in fact the various formulations of the divine power—Lord of Heaven, Lord of all, and simply Lord—refer unmistakably to the Christian God. The single word, meaning literally Lord of the Land (Egziabeḥēr), is in fact the standard name for God in the Ethiopic Bible and should be rendered as such. But the most striking feature of Aezanas’ inscription is that it nowhere mentions Jesus Christ or the Trinity.

His allusions in this text to his war with the Noba show how much the geopolitical situation had changed in the Sudanese area since the end of the previous century. It was in 298 that the emperor Diocletian had gone to Egypt and addressed the problems his government faced from the tribes in upper Egypt and, to the south of it, in lower Nubia. The imperial frontier in the region had been at Hiera Sykaminos south of Syene (Aswan), and it enclosed the territory known as Dodekaschoinos (“Twelve Mile Land”) along the Nile. But the emperor observed that the expense of policing the area with Roman troops was not balanced by the revenues that were coming into the treasury, and so he astutely decided to solve the problem by pulling the frontier back to Syene (Aswan) and putting the African tribe of Nobatai into the Dodekaschoinos district. This tribe had been causing havoc by plundering the oasis area of the Thebaid, and so Diocletian found he could eliminate both this vexation and the unprofitability of the southern frontier by transplanting the Nobatai into good land along the Nile that they were glad to have.11 This migration of the Nobatai served also, as Diocletian had expected, to curtail the depredations of the Blemmyes, who had been another troublesome tribe for the new emperor. They were forced southeast into territory where they could be held in check by the Nobatai who were now on both sides of the Nile (Map 1).

To solidify the resettlement agreement the emperor decreed that a fixed amount of gold should be paid annually to the Nobatai and the Blemmyes alike to keep them from plundering the adjacent Roman territory to the north of the new frontier at Syene. This was an exceptionally clever reorganization on Diocletian’s part, and it meant that lower Nubia now lay outside the Roman Empire. Because the kingdom at Meroë had already collapsed by this time, the land to the north and west of the capital, particularly in the great arc of the Nile between the fourth and fifth cataracts, was now available for the tribe of the Noba to move into. These were the people against whom the Christian Aezanas found it necessary to make war in the middle of the fourth century. They were obviously attempting to fill the power vacuum left by the fall of Meroë.

In contrast with the absence of references to Christ or the Trinity in the Ethiopic text that dates from the time of Aezanas’ conversion, the inscription that he set up in Greek displays overtly Christian protocols as well as a partial record of the same conquests. It is much less oblique. This is either because it came a little later or, more probably, because Aezanas felt he could be more open in the official language of eastern Christianity than in his own native Ge‘ez. The two texts are manifestly related, as scholars have recognized ever since the publication of the Greek, and they cannot be very far apart in time even though they differ in the manner in which Aezanas chose to make his conversion public. The Greek text begins, “In trust in God and in the power of the Father, Son, and Holy Ghost, for His salvation of my kingdom through faith in His Son, Jesus Christ.” The negus calls himself a doulos Christi (slave/servant of Christ), and continues to speak of his indebtedness to God and to Christ. He says that because of the complaints of various tribes “I went forth to fight against the Noba, and I rose up in the power of God–Christ (tou theou Christou), in Whom I trusted, and He guided me.” The account of the Noba is much more succinct here than in the Ethiopic inscription, but the acknowledgment of divine guidance is much more emphatic. The radiance of Aezanas’ conversion shines through this Greek text, whereas it glimmers rather more faintly, if nonetheless unmistakably, in the Ethiopic already quoted.

The problem of Aezanas’ representation of himself as a Christian in his capital city is complicated still further by the remarkable fact that the recently discovered stone with the Greek text bore on its other side an inscription in Ge‘ez that is terminated along a side edge of the block.12 There are many puzzles about this new Ethiopic inscription, not least because it does not reproduce the content of the Greek text and is written in the fancy Sabaic musnad script with South Arabian mimation, but exceptionally from left to right. It looks as if this stone had been fitted into the side of the throne that was being dedicated, and this has led the editors of the Ethiopic text to assume that the Greek, with its fulsome acknowledgment of Christ and the Trinity, must represent a missing opening section of the Ethiopic text, but if so we have to ask where those opening lines could have been inscribed. All that we have starts at the top of the stone, and so conceivably any missing lines stood on another block that formed the other side of the throne.

But that would be a desperate solution. The Ethiopic as we can read it actually refers to the Lord God (’gzbḥrm) and the Lord of Heaven (’gz’m śmym), and the extension of the text on the side ends terminates at the bottom with a highly visible Christian cross.13 Even so this block remains problematic, with its different texts in different languages, including the alien Sabaic script, for the Ge‘ez, written oddly, as if in Ethiopic script, from left to right. The Christianity of the negus is plain, but it would seem as if he had not fully moved beyond the ambivalence he felt in publicizing it when he confined himself in his other inscription to expressing gratitude only to the Lord of Heaven, who made his kingdom and the earth beneath it.

Whether the new faith of Aezanas should be ascribed to the missionary work of Frumentius remains an open and insoluble question. The story of the conversion of Ethiopia at the hands of a bishop of that name remains a familiar one to historians of the early Church. But his arrival in Axum after a pirate raid off the coast and his reported connections with Athanasius in Alexandria are much too imprecise and ill documented to verify. It is at least clear that the Byzantine emperor himself, the Arian Constantius, was unhappy to have a disciple of the orthodox Athanasius, who had been driven repeatedly into exile, as his Christian missionary to the Ethiopians. We have seen that this emerges clearly from Constantius’ complaint in the letter that Athanasius himself cited in 356. Frumentius’ mission could easily be located in the years before that, when Aezanas made his first professions of Christianity on both inscriptions and coins.

A considerably later throne inscription, clearly modeled on the throne texts of Aezanas, comes from his successor Ella Asbeha, known as Kālēb. This text shows a fully developed Christian preamble in Ge‘ez, once again in Sabaic script: “To the glory of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost.”14 By the early sixth century Christianity had undoubtedly put down strong roots in Axum. Ares and Maḥrem were gone forever, even though Ella Asbeha (Kālēb) chose to maintain both local and foreign scripts in which to proclaim his faith at Axum, exactly as his great predecessor had done.

Among the rulers between Aezanas and Kālēb, however, there had been another Christian negus, whose coin legends serve to explain the transition across the long period from Aezanas in the late fourth century to Kālēb in the sixth. He is a mysterious ruler known only from coins, including one magnificent gold specimen.15 His name appears as MḤDYS, but since the vocalization is unknown there is no way of telling how this name would have looked with vowels. The coin has no Greek equivalent. It is clear that he ruled in the early 450s. The legends on the coins leave no doubt that he took the lead, immediately after the Council of Chalcedon of 451, in placing his nation squarely among the Monophysites in the Christian East. After the Chalcedonian affirmation of the inseparability of Christ’s two natures, human and divine, in one person, those who adhered to belief in his single divine nature—Monophysites—had broken away to form a substantial population of Christians in the Near East. To emphasize his role, MḤDYS presented himself as a kind of Ethiopian Constantine. Just as Constantine reported seeing the cross in heaven with the promise in hoc signo vinces “In this sign (the cross) you will conquer,” he announced explicitly through the Ethiopic text on his coinage that he too would conquer by the cross (masqal). Ethiopic temawe’ (“he will conquer”) corresponds exactly with vinces, and MḤDYS attached the epithet mawā’ī, (victor) to his name, just as Constantine was maximus victor or victoriosissimus.16 In this way he advertised a new era of felicity at the very time he established the Monophysite credentials of his Axumite court.

In laying claim in the sixth century to overseas territories that he did not actually rule, Kālēb not only followed in the tradition of Aezanas whose throne inscriptions he imitated but equally in the Constantinian imperialism that MḤDYS had proclaimed. As these claims became increasingly strident, they were matched by social and political upheavals in Ḥimyar. The irredentism of the Ethiopian monarchy was just as strong as ever, but events across the Red Sea served to provide an incentive for the Axumite regime to realize its ambitions in southwest Arabia by coming to the rescue of persecuted Christians. Fatefully, just as a religious conversion had emboldened a new leadership in Ethiopia to take on a more aggressive and more public posture, a comparable religious conversion had achieved something similar among the Arabs in Ḥimyar. What happened concomitantly on both sides of the Red Sea reflected the old and the new territorial claims of the two kingdoms. But the religions to which the Ethiopians and the Ḥimyarites converted were not the same. Their conversions ultimately struck the spark that ignited an international conflagration.