With the disappearance of Kālēb from the historical record, and the brutal and rapid removal of his nominee, Sumyafa Ashwa‘ (Esimphaios) in Arabia, a power vacuum allowed the international role of the great powers of the eastern Mediterranean to become far greater than it ever had been before. Justin had encouraged and supported, with both ships and troops, the Ethiopian invasion of Ḥimyar in 525, but, at least to judge from the rich and nearly contemporary sources that we have examined, this intervention was directly connected with the persecution that the Christians in Arabia had suffered at the hands of Yūsuf. But when Kālēb returned to Axum after his triumph over the Jewish king in Arabia, the relations between the nations on either side of the Red Sea acquired a distinctly more fluid and less confrontational character that could readily accommodate intervention from outside states. This allowed the Byzantine and Persian empires to expand their diplomatic activity in the Arabian territory substantially beyond the traditional client arrangements that had enabled them to exert indirect influence in the past.

It was at this highly sensitive juncture that Byzantium, under its new emperor Justinian, who succeeded Justin in 527, began to play an active role by exploiting the re-established presence of Christians in Ḥimyar to oppose their Persian enemies. His plan was to enlist the support of the Ethiopians. The Ethiopian invasion and occupation of Arabia had certainly not begun as the first step in a proxy war. Both confessional allegiance and irredentist ambitions more than account for Ethiopian militarism at that time. But by the early 530s this militarism had taken on the additional baggage of Byzantine foreign policy, even as Ḥimyar itself was transformed into an overseas territory within the international orbit of Axum. Procopius could not be more explicit about Justinian’s aims in dealing with the new balance of power in the Red Sea countries: “The emperor Justinian,” he wrote, “had the idea of allying himself with the Ethiopians and the Ḥimyarites, in order to work against the Persians.”1

The Ethiopian–Byzantine alliance was inevitably uneasy, since the Monophysites were not naturally comfortable with the Chalcedonians. But Justinian seems to have detected an opportunity to intercept Persian commercial interests in the Red Sea by preempting the Persians in buying silk from India that arrived at Red Sea ports. This may well have been the primary motivation for Justinian’s surprising subjugation of an ancient Jewish settlement on the small island of Iotabê at the southern end of the Gulf of Aqaba,2 and it seems equally to have been part of the reason for new diplomatic initiatives launched from Constantinople. But the larger objective of building a power base in Arabia against Persia can be seen in the earliest diplomatic negotiations between Constantinople, Axum, and Ḥimyar, and as these negotiations developed this objective becomes increasingly clear. But it would be naive to ignore the economic incentive that can be observed at Iotabê.

Justinian dispatched two embassies during the brief reign of Sumyafa Ashwa‘ in order to further his program for an Ethiopian-Ḥimyarite alliance with Byzantium against Persia. A certain Julianus led the first embassy, and at about the same time, or a little later, the much better known Nonnosus led the second. This Nonnosus, who acted for Justinian, was the son of Justin’s ambassador to Ramla, Abramos, and the grandson of Anastasius’ ambassador to the Ḥujrid sheikh Ḥārith of Kinda.3 He thus represented the third generation of a family entrusted with Byzantine foreign policy in Arabia, and he presumably had good credentials not only through his education but also through the Semitic background of his family. He must have had a good knowledge of one or more Semitic languages and was thus able to communicate, to some degree, with Arab sheikhs. His Greek from Constantinople would have stood him in good stead at Axum, but his fluency in one or more Semitic tongues, if not necessarily Ge‘ez, would have helped. Nonnosus’ father, Abramos, had not only been to Ramla but had subsequently returned to the region soon afterwards, this time on behalf of Justinian, to negotiate a peace treaty with the current Ḥujrid sheikh, Qays or, as he is known in Greek sources, Kaïsos. Like Ḥārith, who had presumably died, Kaïsos ruled over the tribes of Kinda and Ma‘add in central Arabia.4 Abramos not only persuaded him to accept the treaty but even to send his son Mu‘awiyya as a hostage to Constantinople to secure it.

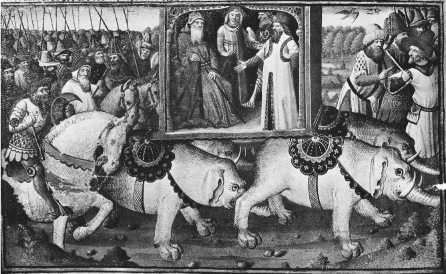

These events provide the immediate background to the mission of Abramos’ son Nonnosus in about 530. Justinian gave him a twofold charge—to bring Qays back to the capital city and to go himself to Ethiopia to meet the negus, who was still Kālēb near the end of his public career. The ever observant Nonnosus entered Ethiopia through Adulis and journeyed from there overland to Axum, taking notes all along the way about what he saw, including the herds of elephants in the vicinity of Aua that he encountered halfway between Adulis and Axum. He left behind a vivid description of his meeting with the negus, whose ring he had to kiss after prostrating himself before him.5 When the great man stood to receive Nonnosus, he was largely nude, wearing only a loincloth together with a pearl-encrusted shawl over his shoulders and belly, bracelets on his arms, a golden turban with four tassels on each side, and a golden torque on his neck. In the company of his courtiers he stood astride a spectacular gold-leafed palanquin mounted on the circular saddles of four elephants that had been yoked together.

An astonishing miniature image of an identical royal pavillion on four elephants has survived in a medieval manuscript to illustrate Kubalai Khan’s reception of Marco Polo (Fig. 6).6 This single image furnishes the only extant parallel to the scene that Nonnosus described. It is astonishing for its similarity to the palanquin at Axum. It is even more astonishing because the two royal receptions, held in an artificial chamber mounted on the backs of four elephants, occurred so far apart in time and space, in thirteenth-century Mongolia and in sixth-century Ethiopia.

Figure 6. Marco Polo’s reception by Kublai Khan in a pavillion on top of four elephants. This image from a manuscript in Paris exactly replicates the scene described by Nonnosus when the negus at Axum received him there ca. 530. These are the only known reports of a royal pavillion of this kind, and the great distance in space and time between the two events in which they appear preclude any direct connection, but ancient traditions in both places may have had some common link. Image reproduced from L. Oeconomos, Byzantion 20 (1950), 177–178, with plate 1.

Unfortunately, despite his intrepid travels and sharp observations, Nonnosus failed to bring back Qays in person to Justinian. Accordingly, the emperor then dispatched Abramos to Arabia for a second time to do just that. Qays finally agreed to go to Constantinople as well as to relinquish his power in central Arabia to his brothers ‘Amr and Yazīd, who would guarantee the Byzantine alliance with Kinda and Ma‘add. In Constantinople Justinian showed his gratitude for this accommodation by conferring upon Qays a phylarchate over the three provinces of Palestine. That was a momentous step. It constituted the beginning of Byzantine-sponsored Arab control in the region, which continued under Abū Karib, whom Justinian appointed as a provincial governor called a phylarch (tribal chieftain) from the Jafnid (Ghassānid) tribe in Syria. Abū Karib was the son of the great sheikh Ḥārith of Jabala. He received his Palestinian phylarchate, probably within the larger jurisdiction assigned to Qays, as a reward for giving Justinian a tract of extensive palm groves somewhere in northwestern Arabia, in a region known as Phoinikon—worthless, according to Procopius,7 but useful nonetheless for securing the Byzantine–Jafnid alliance.

It was not long after the exotic spectacle that Nonnosus had so carefully watched at the court of Axum that the victorious Kālēb supposedly retreated to a saintly life in a monastery and sent his crown to Jerusalem to be displayed in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. Among the Ethiopians who had remained in Ḥimyar after the departure of Kālēb in the expectation of a prosperous life in a new land was the son of a Christian slave from Adulis. His name was Abraha, and his father had been a Byzantine merchant working in the Ethiopian port city. When it soon became clear that the Ethiopians in Arabia were dissatisfied with Esimphaios, they found a sympathetic champion in Abraha, and so they overthrew Esimphaios, locked him up, and installed Abraha in his place as king. Having grown up in Adulis, Abraha would have had ample opportunity to mark the aspirations of Ethiopian kings through observing their many inscribed votive thrones and boastful inscriptions. It is perhaps not surprising that he and his supporters wanted to distance themselves from the court at Axum while remaining in their new Arabian environment. It looks as if Abraha and those who raised him up intended to create a state that was independent of the one that had taken them to Arabia. Such independence sent shock waves through the Byzantine empire, and these dislocations were not lost upon the Persian king. Nor were they lost upon those Jews who remained in the peninsula, above all in Yathrib—the future Medina—where, according to the later Arabic tradition, they had been for many centuries.

Procopius reports that before his retirement Kālēb made two desperate attempts to have Abraha removed from Ḥimyar, but they evidently failed. In his first effort to remove Abraha, he sent over to Ḥimyar a force of three thousand men, but these troops were so beguiled by the landscape and climate of southwest Arabia that they made terms with Abraha and refused to go back home. In his second attempt Kālēb sent troops that Abraha was able easily to defeat. Once he had consolidated his position in Ḥimyar, Abraha understandably fostered a conspicuous independence from the Ethiopian monarchy by making plain that he was unwilling to be, or to be seen to be, a puppet of Axum. The great inscription (Fig. 7) that Abraha set up in 547 to immortalize the achievements of his first decades betrays a noticeable coolness towards the negus in Axum, who is scarcely mentioned.8

Figure 7. The great inscription of Abraha from Mārib, recording the repair of the dam and the international conference convoked there in 547–8: CIH 541. Mārib, Yemen. Photo courtesy of Christian Julien Robin.

It is from that inscription we learn that while Abraha was occupied at that moment in major repairs to a ruptured dam in Mārib he had taken advantage of his prominence in Arabia to convoke an international conference. This was undoubtedly the most significant gathering of this kind in the region since al Mundhir had convoked the pivotal meeting at Ramla during the catastrophic reign of Yūsuf. Abraha, as the established Christian monarch of Ḥimyar, had imitated the building policy of Kālēb and constructed or restored churches at both Mārib and at San‘a. In convoking his conference of 547 in the context of conspicuous munificence in repairing the dam, Abraha not only asserted his authority as the region’s most powerful ruler and as a Christian, but at the same time he implicitly recognized the competing interests of external great powers in the affairs of the peninsula. At Mārib he received ambassadors from the emperor in Constantinople, from the king of the Persians, from the Naṣrid sheikh al Mundhir in al Ḥīra, from the Jafnid sheikh Ḥārith ibn Jabala, from Abū Karib, whom Justinian had by now personally appointed as the phylarch of Palestine, and from the negus in Ethiopia, now demoted to only one among many great powers. Abraha clearly recognized, as we can see from the inscription of 547, that his kingdom could simultaneously exploit and influence the ambitions of the main players in the Near East. These were Byzantium (reinforced by Ḥārith), Persia (reinforced by al Mundhir), and inevitably Ethiopia.9

But the pagan, or polytheist, Arabs of the peninsula were conspicuous by their absence from the conference at Mārib, although they probably had no single community that could have possibly represented them. With their many divinities they had nothing to hold them together. Even the well established Jewish tribes at Yathrib had no political influence to match that of the delegates to Mārib in 547, and they were counterbalanced at Yathrib itself by strong pagan tribes. The contending religions at Yathrib ultimately joined together in famously receiving Muḥammad when he made his emigration (hijra) from Mecca to Medina—which became the new name, meaning simply “city,” for the oasis of Yathrib.

In view of what happened later, the pagans and Jews, of whom so little is actually known in the middle of the sixth century, should not be forgotten in reflecting on the last decades of Abraha’s kingship. They may possibly explain a dramatic, even desperate move that the king made only a few years after the Mārib conference.

In 552 he launched a great expedition into central Arabia, north of Najrān and south of Mecca. An important but difficult inscription, which was discovered at Bir Murayghān and first published in 1951, gives the details of this expedition.10 It shows that one of Abraha’s armies went northeastward into the territory of the Ma‘add tribal confederacy, while another went northwestward towards the coast (Map 2). This two-pronged assault into the central peninsula is, in fact, the last campaign of Abraha known from epigraphy. It may well have represented an abortive attempt to move into areas of Persian influence, south of the Naṣrid capital at al Ḥīra. If Procopius published his history as late as 555, the campaign could possibly be the one to which the Greek historian refers when he says of Abraha, whom he calls Abramos in Greek, that once his rule was secure he promised Justinian many times to invade the land of Persia (es gēn tēn Persida), but “only once did he begin the journey and then immediately withdrew.”11 The land that Abraha invaded was hardly the land of Persia, but it was a land of Persian influence and of potentially threatening religious groups—Jewish and pagan.

Some historians have been sorely tempted to bring the expedition of 552, known from the inscription at Bir Murayghān, into conjunction with a celebrated and sensational legend in the Arabic tradition that is reflected in Sura 105 of the Qur’an (al fīl, the elephant). The Arabic tradition reports that Abraha undertook an attack on Mecca itself with the aim of taking possession of the Ka‘ba, the holy place of the pagan god Hubal. It was believed that Abraha’s forces were led by an elephant, and that, although vastly superior in number, they were miraculously repelled by a flock of birds that pelted them with stones. The tradition also maintained that Abraha’s assault on the ancient holy place occurred in the very year of Muḥammad’s birth (traditionally fixed about 570). Even today the path over which Abraha’s elephant and men are believed to have marched is known in local legend as the Road of the Elephant (ḍarb al fīl). Obviously, the expedition of 552 cannot be the same expedition as the legendary one, if we are to credit the coincidence of the year of the elephant (‘Ām al fīl) with the year of the Prophet’s birth.12 But increasingly scholars and historians have begun to suppose that the Quranic date for the elephant is unreliable, since a famous event such as the Prophet’s birth would tend naturally, by a familiar historical evolution, to attract other great events into its proximity. Hence the attack on Mecca should perhaps be seen as spun out of a fabulous retelling of Abraha’s final and markedly less sensational mission. This is not to say that it might not also have been intended as a vexation for the Persians in response to pressure from Byzantium. But it certainly brought Abraha into close contact with major centers of paganism and Judaism in central and northwest Arabia.

Whatever the purpose of the expedition of 552, Abraha’s retreat marked the beginning of the end of his power. That in turn provided precisely the opportunity for which the Persians had long been waiting. A feckless and brutal son of Abraha, whose name seems to have been, of all things, Axum, presided over the dissolution of the Ethiopian kingdom of Ḥimyar, and his administration was continued by his half-brother Masrūq.13 It was a Jew by the name of Sayf ibn dhī Yazan who then undertook to drive the Ethiopians out of Arabia, and although various Arab traditions leave the details of his efforts uncertain it seems clear that he first tried unsuccessfully to solicit the support of Justin II at Constantinople. But this was not forthcoming, first because of the Christian alliance between Byzantium and Ethiopia, and, second, because of Byzantium’s recognition that the Persians had thrown their support in the past to the Jews, Yūsuf above all.

So Sayf as a Jew ultimately turned to the Persians in the person of Chosroes I, king of the Sassanian Persians, whom he approached through the mediation of Persia’s Naṣrid clients at al Ḥīra. Chosroes responded favorably and sent his general Wahrīz with an army that promptly expelled the Ethiopians once and for all.14 By 575 or so the Axumite presence was gone, and the Persians recognized that Christians of whatever confession remaining in Arabia both inside and outside Ḥimyar were no more trustworthy than the pagans. The expulsion of the Ethiopians created a religious instability that was only held in check by the occupying Persians. The mixture of pagans and Jews in Yathrib as well as the pagan contemporaries (mushrikūn) of the young Muḥammad in Mecca constituted a fertile, not to say explosive, middle ground in Arabia between the Byzantine Christian empire, which was allied with Ethiopia, and the Zoroastrian Sassanians.15

The Persian ascendancy, which the Arabian Jews understandably welcomed in view of the former Persian backing of their co-religionists in Ḥimyar, had come to the peninsula not long after Muḥammad allegedly first saw the light of day in Mecca—in 570 by the canonical dating. This year was, at least in tradition, nothing less than the Year of the Elephant, even if the real Elephant may have come and gone decades before. One thing is certain. The final phase of the collision of late antiquity’s two great empires started in this fateful and unstable period. As Muḥammad grew up to rally his Believers and to make his emigration (hijra) to Medina, which was the date-palm oasis at Yathrib with its strong Jewish tribes, the Persians built up their own resources to the point of invading Palestine. In 614 they captured the holy city of Jerusalem, where they killed or expelled Christians even as the Jewish population welcomed them as liberators.16 No one at that moment could possibly have believed that the Persian empire would be in its death throes only a few decades later and that the Sassanian monarchy itself would be finished by the middle of the seventh century. Meanwhile, the court at Constantinople would be helpless to stop the Believers from moving into Syria and Palestine.

Adulis, where a single abandoned throne had documented the beginnings of this tumultuous history, lapsed back into the obscurity from which it had first emerged nearly a millennium before in the Hellenistic Age. Only the manuscripts of Cosmas Indicopleustes, together with several dozen broken thrones and inscriptions on the ground in Ethiopia today, survive to enlighten us.