SoMa From Publishing Past to High-Tech Future |

St. Patrick Church and the Marriott Marquis from Yerba Buena Gardens

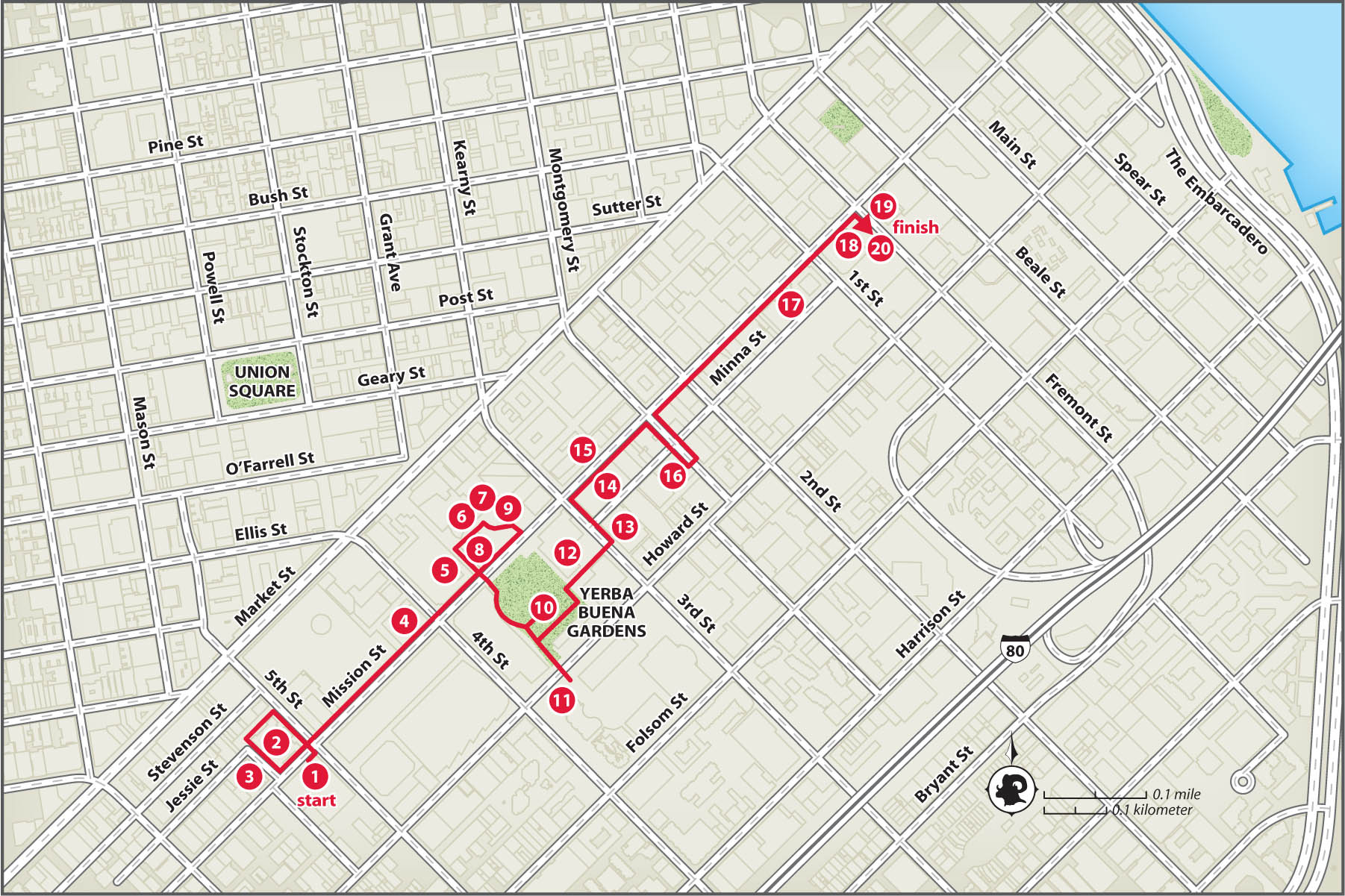

BOUNDARIES: Market St., Fourth St., Second St., Natoma St.

DISTANCE: 1.5 miles

DIFFICULTY: Easy

PARKING: Fifth and Mission garage

PUBLIC TRANSIT: Powell St. BART station; 30, 45 Muni buses; Market St. buses and streetcars

South of Market (SoMa) has been in a state of metamorphosis for decades, and it doesn’t show any signs of stopping. The area around Yerba Buena Gardens, once a grid of skid rows, is now firmly established as a zone of conventions and culture. Moscone Center and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMoMA) anchor the district. Farther to the west by just a few blocks, however, traces of the neighborhood’s down-at-the-heels past remain. Taking it all in makes for an interesting study in contrasts as the transformation of SoMa continues apace. From the residential hotels and seedy underbelly of Sixth Street to the looming Salesforce Tower and Transit Center, this walk highlights San Francisco’s old and new wealth, as well as the vibrant and growing arts district that separates the two.

Start at the corner of Fifth and Mission Streets, the home of the  San Francisco Chronicle. The “Voice of the West” has occupied this building since 1924. By the paper’s own account, it was founded in 1865 by brothers Charles and Michael de Young, who were teenagers at the time and in possession of a single $20 gold piece, which they borrowed. The paper quickly established itself as a legitimate news source when it scooped the city’s other dailies with the news of Abraham Lincoln’s assassination. It was the city’s only afternoon paper, and in the age of the telegraph the timing worked in the favor of the “Chron.” Miraculously, the paper has weathered seismic shifts in journalism, delivering a mix of breaking news and in-depth reporting via online and print outlets. Still, many locals love to complain about its coverage.

San Francisco Chronicle. The “Voice of the West” has occupied this building since 1924. By the paper’s own account, it was founded in 1865 by brothers Charles and Michael de Young, who were teenagers at the time and in possession of a single $20 gold piece, which they borrowed. The paper quickly established itself as a legitimate news source when it scooped the city’s other dailies with the news of Abraham Lincoln’s assassination. It was the city’s only afternoon paper, and in the age of the telegraph the timing worked in the favor of the “Chron.” Miraculously, the paper has weathered seismic shifts in journalism, delivering a mix of breaking news and in-depth reporting via online and print outlets. Still, many locals love to complain about its coverage.

Turn left down Mint Street, an alley behind  The San Francisco Mint. The sandstone building is in good shape, considering that it was built in 1874 and survived the 1906 quake and fire. Lovingly referred to as The Granite Lady, it supposedly once held nearly a third of the entire nation’s money at its peak. It operated as a U.S. Mint until 1937 but these days is used mainly as an event space and wedding venue. A large-scale restoration project, headed by the San Francisco Museum and Historical Society, is moving slowly at press time.

The San Francisco Mint. The sandstone building is in good shape, considering that it was built in 1874 and survived the 1906 quake and fire. Lovingly referred to as The Granite Lady, it supposedly once held nearly a third of the entire nation’s money at its peak. It operated as a U.S. Mint until 1937 but these days is used mainly as an event space and wedding venue. A large-scale restoration project, headed by the San Francisco Museum and Historical Society, is moving slowly at press time.

SFMoMA combines Mario Botta’s 1995 building (foreground) with a 2016 extension.

Mint Street leads to Jessie Street, which along the mint’s left flank has been made into a public square, with a stone patio and orange plastic chairs strewn about for conversation or people watching. A number of cafés and restaurants have opened around this plaza, and during the lunch hour outdoor tables are set up in the shadow of the old mint building, bringing life to a once-neglected alleyway.  Blue Bottle Coffee, on the ground floor of the 1912 San Francisco Provident Loan Association building (which appears in The Maltese Falcon), is an impeccably caffeinated laboratory where single-source coffees burble in siphon pots. (Needless to say, San Francisco’s obsession with coffee reaches ceaselessly for new levels of intensity.)

Blue Bottle Coffee, on the ground floor of the 1912 San Francisco Provident Loan Association building (which appears in The Maltese Falcon), is an impeccably caffeinated laboratory where single-source coffees burble in siphon pots. (Needless to say, San Francisco’s obsession with coffee reaches ceaselessly for new levels of intensity.)

The next block of Mission Street is defined by a block-long parking garage on one side and the sleek glass back of Bloomingdale’s department store on the other. At the end of the block, a partial view opens up on the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, the result of a 30-year project to transform 87 acres of dilapidated hotels into a shopping, convention, and cultural district.

More than a century ago, SoMa was known as South of the Slot, for the cable car slot that ran down Market Street. It was home to immigrant families and to migrant workers, a considerable proportion of whom were seasonal laborers who mined the foothills and cleared Sierra forests. Between jobs or during the winter, they meandered back to the city, where they flooded into SoMa’s bounty of residential hotels. When gold rush–era fires and the 1906 quake destroyed parts of San Francisco, SoMa itinerants came in handy for the rebuilding effort. More often, though, they were forced to stretch meager savings over fruitless winters. They ate cheap meals in diners and found their entertainment in pool halls and theaters. Free lunches could be had in saloons and at rescue missions. Many had a propensity to drink and went broke before the arrival of spring. Able-bodied men were often reduced to panhandling. The injured and aged had little hope of ever seeing a paycheck again. The Great Depression broke many a man’s back here, and the neighborhood declined and never recovered. By the mid-60s, SoMa, like the Tenderloin to the north, was a grid of skid rows, its residents largely subsisting on monthly relief checks. The city’s Redevelopment Agency fixed its eye on the area. They met with resistance from tenant groups, but in the end the agency had its way, sweetening the deal with museums and the promise of cash trickling down from conventions at Moscone Center. Demolition of block after block began in the late 1970s and, along with Ronald Reagan’s policy of slashing federal aid to urban programs, coincided with a dramatic jump in the city’s homeless population.

Note the office at 814 Mission, former home of the  Daily Evening Bulletin, which once boasted the highest circulation of any paper in the city. Founded by James King of William in 1855, King used the paper to wage against political corruption. His success was short lived, however, as a year later he was gunned down in broad daylight by city supervisor and rival newspaper editor James Casey who was angry about a critical piece the paper had run about him. The San Francisco Committee of Vigilance responded by taking matters into its own hands and hanging Mr. Casey. No easy business, this journalism.

Daily Evening Bulletin, which once boasted the highest circulation of any paper in the city. Founded by James King of William in 1855, King used the paper to wage against political corruption. His success was short lived, however, as a year later he was gunned down in broad daylight by city supervisor and rival newspaper editor James Casey who was angry about a critical piece the paper had run about him. The San Francisco Committee of Vigilance responded by taking matters into its own hands and hanging Mr. Casey. No easy business, this journalism.

Continue east on Mission Street. Cross Fourth Street and continue a few steps down Mission to Yerba Buena Lane on your left, a pedestrian route that cuts directly to Market Street. The walkway links the San Francisco Marriott Marquis hotel, the Contemporary Jewish Museum, and St. Patrick’s Church. The gleaming tower of the  Marriott Marquis is a much-reviled piece of architecture that fatefully opened on the day of the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake. Sound construction ensured that only one window was broken; it couldn’t, however, protect the building from the rapier wit of Chronicle columnist Herb Caen, who likened it to a jukebox and famously complained that the glare blinded him in his office. (Truthfully, though, San Franciscans would probably appreciate it if it looked more like a jukebox and less like a hotel.) The

Marriott Marquis is a much-reviled piece of architecture that fatefully opened on the day of the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake. Sound construction ensured that only one window was broken; it couldn’t, however, protect the building from the rapier wit of Chronicle columnist Herb Caen, who likened it to a jukebox and famously complained that the glare blinded him in his office. (Truthfully, though, San Franciscans would probably appreciate it if it looked more like a jukebox and less like a hotel.) The  Contemporary Jewish Museum occupies a historic power substation, with modifications designed by architect Daniel Libeskind, who found time to draw these plans while winning the contract for the new World Trade Center towers in New York City. The building’s facade, designed by Willis Polk in 1907, survives in its entirety, with Libeskind’s off-kilter cubes, colored a somber shade of night blue, jutting above the roof and adjoining the west side of the building. The museum itself has galleries devoted to art, history, and ideas, all relating to the Jewish people. It’s also home to the excellent

Contemporary Jewish Museum occupies a historic power substation, with modifications designed by architect Daniel Libeskind, who found time to draw these plans while winning the contract for the new World Trade Center towers in New York City. The building’s facade, designed by Willis Polk in 1907, survives in its entirety, with Libeskind’s off-kilter cubes, colored a somber shade of night blue, jutting above the roof and adjoining the west side of the building. The museum itself has galleries devoted to art, history, and ideas, all relating to the Jewish people. It’s also home to the excellent  Wise Sons Jewish Delicatessen, serving up bagels, salads, and matzo ball soup; museum admission isn’t necessary to have a little nosh.

Wise Sons Jewish Delicatessen, serving up bagels, salads, and matzo ball soup; museum admission isn’t necessary to have a little nosh.  St. Patrick Church, originally the parish of Irish Catholics who lived South of the Slot, was built in 1872. Step inside for a look at the stained glass windows. Some members of the now-predominantly-Filipino congregation may be lighting votive candles or crawling, in a display of humility, up the aisles toward the altar. Across Jessie Square from the church, a four-story glass cube will be the new digs for the

St. Patrick Church, originally the parish of Irish Catholics who lived South of the Slot, was built in 1872. Step inside for a look at the stained glass windows. Some members of the now-predominantly-Filipino congregation may be lighting votive candles or crawling, in a display of humility, up the aisles toward the altar. Across Jessie Square from the church, a four-story glass cube will be the new digs for the  Mexican Museum. The Smithsonian affiliate museum is the oldest in the country focused solely on Mexican, Chicano, and Latino art. Its new multimillion-dollar building—which will have seven times the space of its current Fort Mason home—promises to provide rich artistic, cultural, and educational experiences when it opens in 2020.

Mexican Museum. The Smithsonian affiliate museum is the oldest in the country focused solely on Mexican, Chicano, and Latino art. Its new multimillion-dollar building—which will have seven times the space of its current Fort Mason home—promises to provide rich artistic, cultural, and educational experiences when it opens in 2020.

On the other side of Mission Street, the Metreon shopping center opened at the height of the dotcom frenzy, promising to be a beacon of cool technology, hence the late-1990s vibe. Many of the original shops, including showcases for Sony and PlayStation products, barely survived the ’90s, and the place no longer seems to be the wave of the future. But there’s a decent food court if you’re hungry, plus a bookstore and a busy multiplex cinema. Walk through the Metreon and exit through the doors on the east side, facing Yerba Buena Gardens; then follow the meandering path that borders the Metreon on your left. The park is essentially an undulating lawn and a few trees, but it’s a lovely urban space enhanced by an attractive skyline.

Wander over to the elegant  Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial, where a series of waterfalls pounds rocks below and drowns out your thoughts. Walk behind the falls to fully experience this reflective monument. From May to October, on weekends and some weekdays, a stage is set up on the lawn for live music and dance performances. Acts range from puppeteers to opera singers, and admission is free. If you take a detour to the upper level, continuing up the path to the right of the MLK Jr. Memorial, you’ll find a raised walkway crossing Mission Street that brings you to a vintage carousel, an ice-skating rink, a bowling alley, a playground, and the Children’s Creativity Museum, a space dedicated to innovative art and technology for the under-12 set.

Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial, where a series of waterfalls pounds rocks below and drowns out your thoughts. Walk behind the falls to fully experience this reflective monument. From May to October, on weekends and some weekdays, a stage is set up on the lawn for live music and dance performances. Acts range from puppeteers to opera singers, and admission is free. If you take a detour to the upper level, continuing up the path to the right of the MLK Jr. Memorial, you’ll find a raised walkway crossing Mission Street that brings you to a vintage carousel, an ice-skating rink, a bowling alley, a playground, and the Children’s Creativity Museum, a space dedicated to innovative art and technology for the under-12 set.

The Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial is the US’s second-largest monument dedicated to this great leader.

The  LeRoy King Carousel, designed by master carver Charles I. D. Loof (who designed Coney Island’s first carousel), was originally slated for delivery to a small Market Street park in 1906. The earthquake changed that, and it was rerouted to Seattle’s Luna Park instead. The miraculous carousel somehow survived the great Luna Park fire of 1911 and bounced around various locations until finally landing here in 1998.

LeRoy King Carousel, designed by master carver Charles I. D. Loof (who designed Coney Island’s first carousel), was originally slated for delivery to a small Market Street park in 1906. The earthquake changed that, and it was rerouted to Seattle’s Luna Park instead. The miraculous carousel somehow survived the great Luna Park fire of 1911 and bounced around various locations until finally landing here in 1998.

The  Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, with exhibit spaces and a performing-arts center, takes up the Third Street side of the park. It emphasizes the work of living artists in all media, mostly with a local angle; admission is $10. With the arts center at your back, head toward the giant fountain bordering Third Street and take the crosswalk directly to the

Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, with exhibit spaces and a performing-arts center, takes up the Third Street side of the park. It emphasizes the work of living artists in all media, mostly with a local angle; admission is $10. With the arts center at your back, head toward the giant fountain bordering Third Street and take the crosswalk directly to the  SFMoMA. Designed by Mario Botta, the museum moved to these new digs in 1995 after residing in the Civic Center for many decades. In 2013 the museum closed for a three-year, $305-million expansion of 10 additional floors, nearly tripling the gallery space. Upon its reopening in 2016, The New York Times raved that the renovation “bumps this widely respected institution into a new league, possibly one of its own.” It’s an immensely popular museum, and the lauded Fisher Collection, bequeathed by Gap founders Doris and Donald Fisher, adds real depth. Its photography collection is excellent, and fine traveling exhibits stop here regularly. Inside the museum are a variety of dining options from the casual Sightglass Coffee to the Michelin-starred In Situ. Admission to the museum (which is closed Wednesdays) is $25, but there are some free installations on the first two floors, including an immense Richard Serra piece, Sequence, that you may walk through.

SFMoMA. Designed by Mario Botta, the museum moved to these new digs in 1995 after residing in the Civic Center for many decades. In 2013 the museum closed for a three-year, $305-million expansion of 10 additional floors, nearly tripling the gallery space. Upon its reopening in 2016, The New York Times raved that the renovation “bumps this widely respected institution into a new league, possibly one of its own.” It’s an immensely popular museum, and the lauded Fisher Collection, bequeathed by Gap founders Doris and Donald Fisher, adds real depth. Its photography collection is excellent, and fine traveling exhibits stop here regularly. Inside the museum are a variety of dining options from the casual Sightglass Coffee to the Michelin-starred In Situ. Admission to the museum (which is closed Wednesdays) is $25, but there are some free installations on the first two floors, including an immense Richard Serra piece, Sequence, that you may walk through.

140 New Montgomery is replete with Art Deco glam.

Follow Third Street back to Mission Street, and turn right. On the next block, between Third and New Montgomery, are two notable museums. First is the  Museum of the African Diaspora (MoAD), which showcases the work of African and African-descended artists ($10 admission; closed Monday and Tuesday). Across the street is the

Museum of the African Diaspora (MoAD), which showcases the work of African and African-descended artists ($10 admission; closed Monday and Tuesday). Across the street is the  California Historical Society, a research facility with a huge library and a collection of historical photos, maps, and artifacts. It plucks gems from its collections for display in the back gallery ($10 admission; closed Monday). This is a fabulous place to pick up unique and interesting California and San Francisco gifts.

California Historical Society, a research facility with a huge library and a collection of historical photos, maps, and artifacts. It plucks gems from its collections for display in the back gallery ($10 admission; closed Monday). This is a fabulous place to pick up unique and interesting California and San Francisco gifts.

At New Montgomery turn right. The striking Art Deco high-rise at 140 New Montgomery (at the corner of Minna Street) is the former  Pacific Telephone & Telegraph Building, designed by Timothy Pflueger and James Miller and built in 1925. A striking symbol of the telecommunications age, it was San Francisco’s first and tallest skyscraper for three years. Today the building’s main occupier is the online review business Yelp, and a step inside the lobby reveals a beautiful $60-million restoration, including unicorns and phoenixes gracing the ceiling, said to be adapted from a Chinese brocade. You will also see Art Deco nods to the original tenants.

Pacific Telephone & Telegraph Building, designed by Timothy Pflueger and James Miller and built in 1925. A striking symbol of the telecommunications age, it was San Francisco’s first and tallest skyscraper for three years. Today the building’s main occupier is the online review business Yelp, and a step inside the lobby reveals a beautiful $60-million restoration, including unicorns and phoenixes gracing the ceiling, said to be adapted from a Chinese brocade. You will also see Art Deco nods to the original tenants.

Return to Mission Street and continue heading south toward the waterfront crossing Second Street. Community activists are actively trying to rebrand this area as the East Cut. Longtime San Franciscans know this area as Rincon Hill, one of the original storied seven hills of San Francisco. Following the gold rush, this was an upscale and sought-after neighborhood, where sea captains and upper-crust merchants settled to escape the bawdy Barbary Coast. But an ill-fated urban planning decision of 1869 was the beginning of the end, when the hill was leveled along Second Street to improve access to the southern waterfront. The 1906 earthquake and subsequent fires were the nail in the coffin, as families fled to higher addresses with better views. Adding insult to injury, the 1950 construction of the Embarcadero freeway essentially surrounded the area with concrete and cut it off from the Financial District. But when the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake hit, leading to the removal of the damaged freeway, development eyes turned once again to the forgotten area. With glass towers sprouting up seemingly overnight, the area is definitely changing; whether the name sticks remains to be seen.

About two-thirds of the way down Mission from Second Street, look for the stairway past the 100 First Garage. This leads you up to the  100 First Street Rooftop Garden, an open sun terrace with plenty of benches, water features (including art meant to evoke ocean waves), and greenery. This is one of many privately owned public open spaces, or POPOS, that are hidden gems of the downtown area. In 1985, zoning regulations changed to control growth and also assure that new development provided for public open space; as a result, more than 60 POPOS dot downtown and the Financial District. While there are plaques designating each area, they are often small and rather hidden.

100 First Street Rooftop Garden, an open sun terrace with plenty of benches, water features (including art meant to evoke ocean waves), and greenery. This is one of many privately owned public open spaces, or POPOS, that are hidden gems of the downtown area. In 1985, zoning regulations changed to control growth and also assure that new development provided for public open space; as a result, more than 60 POPOS dot downtown and the Financial District. While there are plaques designating each area, they are often small and rather hidden.

Back on Mission Street, you’ll soon find yourself among the city’s newest and tallest designer skyscrapers. As of 2018, the looming  Salesforce Tower has wrested the “tallest building” designation from the Transamerica Pyramid by reaching 1,070 feet into the fog. Designed by Pelli Clarke Pelli, the tower is built on landfill (tall ships and old anchors are likely underfoot), and developers needed to drive the foundation piles nearly 300 feet below ground to hit bedrock. The top nine stories of the building are devoted to an electronic LED art piece, the brainchild of local artist Jim Campbell. As with all things new in San Francisco, the reaction has been mixed. John King, urban design critic for the Chronicle, has decried its “lack of visual swagger,” while other locals have been less restrained about what they perceive as the demise of the classic San Francisco skyline. It’s worth noting, though, that more than 40 years ago the venerable architecture critic Wolf von Eckardt lambasted the unveiling of the Transamerica Pyramid as “hideous nonsense” that would desecrate one of the most breathtaking skylines of the world.

Salesforce Tower has wrested the “tallest building” designation from the Transamerica Pyramid by reaching 1,070 feet into the fog. Designed by Pelli Clarke Pelli, the tower is built on landfill (tall ships and old anchors are likely underfoot), and developers needed to drive the foundation piles nearly 300 feet below ground to hit bedrock. The top nine stories of the building are devoted to an electronic LED art piece, the brainchild of local artist Jim Campbell. As with all things new in San Francisco, the reaction has been mixed. John King, urban design critic for the Chronicle, has decried its “lack of visual swagger,” while other locals have been less restrained about what they perceive as the demise of the classic San Francisco skyline. It’s worth noting, though, that more than 40 years ago the venerable architecture critic Wolf von Eckardt lambasted the unveiling of the Transamerica Pyramid as “hideous nonsense” that would desecrate one of the most breathtaking skylines of the world.

Across Fremont Street, the  Millennium Tower has gained notoriety for an altogether different reason: it’s sinking. When it first opened in 2009, the tower was hailed as one of the top 10 residential buildings in the world by Worth Magazine. Accolades were flying, and high-profile residents like NFL Hall of Famer Joe Montana and Giants outfielder Hunter Pence brought prestige to the multimillion-dollar luxury condos. But then things shifted—literally. While it’s common for buildings of this size to settle to some degree, the pace and degree to which the Millenium Tower is moving are rather unprecedented: within less than a decade, it has sunk 17 inches and tilted more than 14 inches toward Fremont Street. The problem seems to arise from its heavy concrete (versus steel) frame and the fact that the building’s engineers chose not to drill into bedrock. Not surprisingly, a huge legal battle is ensuing with fingers being pointed everywhere, and the structural solutions being bandied about are more expensive than the building of the tower itself. An art-filled atrium is located on the ground floor, should you want to take a gander inside.

Millennium Tower has gained notoriety for an altogether different reason: it’s sinking. When it first opened in 2009, the tower was hailed as one of the top 10 residential buildings in the world by Worth Magazine. Accolades were flying, and high-profile residents like NFL Hall of Famer Joe Montana and Giants outfielder Hunter Pence brought prestige to the multimillion-dollar luxury condos. But then things shifted—literally. While it’s common for buildings of this size to settle to some degree, the pace and degree to which the Millenium Tower is moving are rather unprecedented: within less than a decade, it has sunk 17 inches and tilted more than 14 inches toward Fremont Street. The problem seems to arise from its heavy concrete (versus steel) frame and the fact that the building’s engineers chose not to drill into bedrock. Not surprisingly, a huge legal battle is ensuing with fingers being pointed everywhere, and the structural solutions being bandied about are more expensive than the building of the tower itself. An art-filled atrium is located on the ground floor, should you want to take a gander inside.

Lofty Salesforce Tower is reflected in the gleaming windows of Millennium Tower.

The crown jewel of all this tech-industry growth is the  Salesforce Transit Center and Park, a $2-billion-plus endeavor that accommodates buses, MUNI, and, we hope, the eternally delayed high-speed rail between San Francisco and Los Angeles. Excavation for the project was vast and unearthed a variety of archaeological treasures, including an 11,000-year-old woolly mammoth tooth that was donated to the California Academy of Sciences, and a glittering nugget from the gold rush. The rooftop park is a beauty to behold, with 5.4 acres of greenery that include an amphitheater, playground, cafés, and restaurants. While there are more pragmatic ways to access the garden, we encourage you to board the 20-person gondola from the corner of Fremont and Mission Streets to enjoy the end of this walk.

Salesforce Transit Center and Park, a $2-billion-plus endeavor that accommodates buses, MUNI, and, we hope, the eternally delayed high-speed rail between San Francisco and Los Angeles. Excavation for the project was vast and unearthed a variety of archaeological treasures, including an 11,000-year-old woolly mammoth tooth that was donated to the California Academy of Sciences, and a glittering nugget from the gold rush. The rooftop park is a beauty to behold, with 5.4 acres of greenery that include an amphitheater, playground, cafés, and restaurants. While there are more pragmatic ways to access the garden, we encourage you to board the 20-person gondola from the corner of Fremont and Mission Streets to enjoy the end of this walk.

SoMa

Points of Interest

San Francisco Chronicle Building 901 Mission St.; 415-777-1111, sfchronicle.com

San Francisco Chronicle Building 901 Mission St.; 415-777-1111, sfchronicle.com

The San Francisco Mint 88 Fifth St.; 415-608-2220, thesanfranciscomint.com

The San Francisco Mint 88 Fifth St.; 415-608-2220, thesanfranciscomint.com

Blue Bottle Coffee 66 Mint St.; 415-495-3394, bluebottlecoffee.com

Blue Bottle Coffee 66 Mint St.; 415-495-3394, bluebottlecoffee.com

Bulletin Building (former) 814 Mission St. (no published phone number or website)

Bulletin Building (former) 814 Mission St. (no published phone number or website)

San Francisco Marriott Marquis 780 Mission St.; 415-896-1600, tinyurl.com/sfmarquis

San Francisco Marriott Marquis 780 Mission St.; 415-896-1600, tinyurl.com/sfmarquis

Contemporary Jewish Museum 736 Mission St.; 415-655-7800, thecjm.org

Contemporary Jewish Museum 736 Mission St.; 415-655-7800, thecjm.org

Wise Sons Jewish Delicatessen 736 Mission St.; 415-655-7887, wisesonsdeli.com

Wise Sons Jewish Delicatessen 736 Mission St.; 415-655-7887, wisesonsdeli.com

St. Patrick Church 756 Mission St.; 415-421-3730, stpatricksf.org

St. Patrick Church 756 Mission St.; 415-421-3730, stpatricksf.org

Mexican Museum 706 Mission St.; 415-202-9700, mexicanmuseum.org

Mexican Museum 706 Mission St.; 415-202-9700, mexicanmuseum.org

Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Yerba Buena Gardens, 750 Howard St.; 415-820-3550, yerbabuenagardens.com

Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Yerba Buena Gardens, 750 Howard St.; 415-820-3550, yerbabuenagardens.com

LeRoy King Carousel 221 Fourth St.; 415-820-3320, creativity.org/visit/childrens-creativity-carousel

LeRoy King Carousel 221 Fourth St.; 415-820-3320, creativity.org/visit/childrens-creativity-carousel

Yerba Buena Center for the Arts 701 Mission St.; 415-978-2787, ybca.org

Yerba Buena Center for the Arts 701 Mission St.; 415-978-2787, ybca.org

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMoMA) 151 Third St.; 415-357-4000, sfmoma.org

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMoMA) 151 Third St.; 415-357-4000, sfmoma.org

Museum of the African Diaspora 685 Mission St.; 415-358-7200, moadsf.org

Museum of the African Diaspora 685 Mission St.; 415-358-7200, moadsf.org

California Historical Society 678 Mission St.; 415-357-1848, californiahistoricalsociety.org

California Historical Society 678 Mission St.; 415-357-1848, californiahistoricalsociety.org

Pacific Telephone & Telegraph Building (former) 140 New Montgomery St.; 140nm.com

Pacific Telephone & Telegraph Building (former) 140 New Montgomery St.; 140nm.com

100 First Street Rooftop Garden 100 First St.; sfpopos.com

100 First Street Rooftop Garden 100 First St.; sfpopos.com

Salesforce Tower 415 Mission St.; salesforcetower.com

Salesforce Tower 415 Mission St.; salesforcetower.com

Millennium Tower 301 Mission St. (no published phone number or website)

Millennium Tower 301 Mission St. (no published phone number or website)

Salesforce Transit Center and Park 425 Mission St.; sfmta.com/projects/salesforce-transit-center

Salesforce Transit Center and Park 425 Mission St.; sfmta.com/projects/salesforce-transit-center