John Ross’s crew saved by the Isabella (illustration credit 3.1)

For most of the decade, John Ross had nursed his wounded pride at his Scottish home – North West Castle, he called it – at Stranraer. A prodigious writer with a voluminous correspondence, he addressed his roving intellect to a variety of inquiries, ranging all the way from the “science” of phrenology to the principles of steam propulsion. It was Ross’s Treatise on Navigation by Steam that showed him to be ahead of his time and also ahead of the British Navy, which was strongly committed to sail. Lord Melville, for one, was convinced that “the introduction of steam was calculated to strike a fatal blow to the naval supremacy of the Empire.”

Ross felt hard done by. In exploding the myth of the Croker Mountains, Parry had made him a laughing stock. His own boasts hadn’t helped. In some quarters those who exhibited an excess of vanity were now said to be afflicted with “Ross-ism.” The Navy had promoted him and Lord Melville had assured him that the service held him in high esteem, but Ross was not taken in by that hollow accolade. When other expeditions were mounted, he was passed over. Parry and Franklin were heroes, but Ross was ignored. That rankled.

But now, in 1827, the Passage beckoned once more. Parry was back after another failure; he and Franklin had not been able to link their separate explorations. Ross saw a chance to regain his lost honour – and at Parry’s expense. All he had to do was cruise down Prince Regent Inlet beyond Parry’s last point of discovery and continue on to Franklin’s Point Turnagain, and the laurel would be his. He went to Melville with a proposal to send a steam vessel to the Arctic in one final, victorious sweep. But the Admiralty wasn’t planning any further expeditions, especially one led by John Ross in a steam-powered ship.

Ross didn’t give up. If the government wouldn’t support an expedition, other patrons might. He went to see his old friend Felix Booth, the distiller, and sheriff of London, who was sympathetic. He felt that Ross had been slighted through anonymous rumours. There was also some suggestion that an American expedition was being formed to seek the Passage. That would never do!

Booth was prepared to advance seven thousand pounds to Ross’s three thousand to make up the total amount the explorer had calculated the expedition would cost. There was, however, a hitch: the government award of twenty thousand pounds promised to the first expedition to sail through to the Pacific. Booth didn’t want anyone to think he was after private gain.

The events that followed were twisted into an ironic, indeed a ludicrous, sequence. With Booth retiring from the plan, Ross was forced to go back to the government with a new Arctic scheme. The government, of course, turned it down, and, being unaware of Booth’s position, persuaded parliament to cancel the reward, apparently to discourage all Arctic schemes in general and John Ross’s in particular. This had the opposite effect from the one intended, for it brought the scrupulous Felix Booth back into the picture. In the end he committed more than seventeen thousand pounds to the venture.

Ross’s second-in-command would be his nephew James, now an experienced Arctic traveller. John Ross believed that Parry’s ships and crews had been far too large. His company would total no more than twenty-three. His ship would be an eighty-five-ton Liverpool steam packet, the Victory, its tonnage increased to one hundred and sixty-five by a series of improvements but still less than half the tonnage and draught of the Hecla or the Fury. A sixteen-ton tender, the Krusenstern, accompanied the expedition, which reached Disco Island off the west coast of Greenland on July 28, 1829.

Now it was John Ross who was lucky, for this was the mildest season in the memory of Greenland’s oldest inhabitants. Steaming northwest across Baffin Bay, Ross expected at any hour to encounter the ice that had trapped Parry. To his astonishment and delight, the ocean was clear. “But for one iceberg … we might have imagined ourselves in the summer seas of England.” At six on the morning of August 4, he found his men scrubbing the decks barefoot – a remarkable spectacle. Two days later, he entered Lancaster Sound. He had crossed Baffin Bay in nine days; Parry on his second voyage had taken two months.

In the sound, some disagreeable memories returned to haunt him. He couldn’t resist a crack at Parry in his journal. Sir Edward had not uttered so much as a whisper at the time to support his later belief that Lancaster Sound was a strait. Even if he had done so, Ross felt he had been justified in turning back. Now, it was his turn to solve the problem that had stumped Parry. If he ever returned to England, Ross told himself, he would be received in a very different manner.

His luck continued to hold. He breezed down the sound and into Prince Regent Inlet in thirty-six hours, again outdoing Parry. The only difficulty was the steam engine, which hadn’t worked properly since the start of the voyage. Ross seemed to be spending half his time in the engine room helping the men fix boiler leaks and faulty pumps. The engine was soon abandoned in favour of sail, a circumstance that was to provoke a lively, choleric, but ultimately ineffective pamphlet war between Ross and the builder, Braithwaite, each of whom blamed the other for the problem.

On August 12, the expedition passed Fury Beach. There was no sign of Parry’s vessel, but the tent poles of the previous expedition were clearly visible in the shadow of the glowering limestone cliffs. It had always been Ross’s plan to replenish his own stores from those left by Parry, but to his mortification, he found that the current and the tide made it impossible to land.

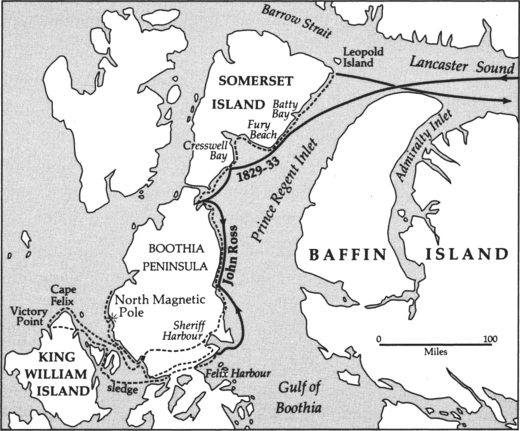

John Ross and James Clark Ross, 1829-33

On he went. Cresswell Bay, named by Parry, seemed on first inspection to be a passage to the west – an apparent victory over his rival and hailed as such by some of Ross’s supporters on board. Ross, however, took no joy in this revelation, or later claimed he didn’t. “I would rather find a passage anywhere else,” he told his nephew, because, as he said later, “I am quite sure that those who have suffered as I have from a cruelly misled Public Opinion will never wish to transfer such misery to a fellow creature if their hearts are in the right place.” As it eventually turned out, Cresswell Bay was an inlet that led nowhere.

The Victory returned north and this time found an anchorage off Fury Beach, strewn with Parry’s supplies, all in good condition. The crew stowed as much as they could on board. “God bless Fury Beach,” they cried as they rowed back to the ship. At least they weren’t going to starve.

Ross again pushed south down into the inlet. On August 16 he passed Parry’s farthest point and entered unknown waters, breaking out some bottles of his sponsor’s gin in celebration. By the end of September he had gone three hundred miles farther than Parry and was only two hundred and eighty miles from the point where Franklin had turned back in 1821. But, of course, there was a land mass blocking the way.

Now his luck ran out. The Arctic turned fickle. Buffeted by gales and raging seas, almost crushed by jostling icebergs, he gave up. Like the others, he had failed, and, like the others, he was tormented by that failure. Could he have got through the Passage if the engine hadn’t given out? Could he have achieved his ambitions in a bigger ship? The answer, though he didn’t know it, was no, for Prince Regent Inlet was virtually a dead end. There was one narrow channel leading through the great mass of land to the west (later to be named Bellot Strait), but it was so constricted that Ross had missed it on his voyage south.

Now, in October, he struggled through the encroaching ice of the great gulf that lay at the bottom of Prince Regent Inlet. Ross, whose powers of description were considerable, pictured it later for his readers.

Let them remember, he wrote, that “ice is stone – a floating rock in a stream.” Then “imagine, if they can, these mountains of crystal hurled through a narrow strait by a rapid tide; meeting, as mountains might meet, with a noise of thunder, breaking from each other’s precipices huge fragments, or rending each other asunder, till, losing their former equilibrium, they fall over headlong, lifting the sea around in breakers, and whirling it into eddies while the flatter fields of ice, formed against these masses … by the wind and the stream, rise out of the sea until they fall back on themselves, adding to the indescribable commotion and noise.…”

At last Ross found a suitable harbour, which he named Felix Harbour after his patron. The land off which they anchored the Victory would be called Boothia Felix (it is now Boothia Peninsula) and the gulf, the Gulf of Boothia. No bottled stimulant ever received greater recognition.

It was as well for Ross’s sanity that he had no idea in that late autumn of 1829 that he would be forced to spend four winters in the Arctic. No other explorer had spent more than two. The remarkable aspect of Ross’s long imprisonment is that he was able to bring his crew home virtually free of the scurvy that weakened other expeditions. This was no accident. Ross had divined what others had ignored and would continue to ignore for the next half century. He had learned from studying the Eskimos that “the large use of oil and fats is the true secret of life in these frozen countries, and that the natives cannot subsist without it, becoming diseased and dying under a more meagre diet.” Ross was convinced that if others had followed “the usage and experience of the natives,” fewer would have perished.

He was on the right track: seal blubber is rich in Vitamin C. Of course, he was in an area where game and fish abounded, yet he had to depend on the Eskimos not only to hunt for fresh meat and fish but also to provide furs to replace the Navy issue of wool. Without the natives, the story of Ross’s four-year ordeal would have ended tragically.

The Victory and its little tender were frozen in for eleven months. On July 24, 1830, the bay was free of ice, but to Ross’s dismay there was no way out of the harbour; it was too shallow, the tides were too low. He had chosen the worst possible wintering place. The crews struggled for two months but succeeded in moving the ships no more than three miles. Ross named his new anchorage Sheriff Harbour (after Sheriff Felix Booth, of course) and resigned himself to another winter in the ice.

The following summer – 1831 – he waited again for the ice to set him free. Again he waited in vain. “To us,” Ross said, “the sight of ice was a plague, a vexation, a torment, an evil, a matter of despair.” Once more the Victory managed to make about three miles, to be stopped by an impenetrable ridge of ice. The new harbour was named for the ship but changed later to Victoria Harbour to honour the young princess who would shortly be queen.

Again, the worst aspect of these three winters was boredom. The usual schools, lectures, and small entertainments soon palled. There was nothing to do, nothing to gaze out on, for the landscape and sky never changed. To Ross, even the storms lacked variety “amid this eternal sameness of snow and ice.” Some men were able to sleep through most of the winter. Others “dozed away their time in the waking stupefaction, which such a state of things produced.”

It was not a happy ship; perhaps no ship could have been under the circumstances, although Parry had gone a long way to lighten the dark season for his crews. But Ross was not Parry, as William Light, a steward on the expedition, made clear in his published reminiscences of the voyage. Parry, Light recalled, knew how to bend, “but with Capt. Ross the case was different, he was trebly steeped in the starch of official dignity, the maintenance of which he considered to consist in abstracting himself as much as possible from familiar intercourse with those beneath and suffering no opportunity to escape him, by which he could shew to them that he was their superior and commander. The men were conscious that they owed him obedience; they were not equally convinced that they owed him their respect and esteem.”

Light’s memoir, published with the aid of a ghost writer, draws aside the curtain of naval imperturbability that conceals so much. In no other instance was the English public allowed a peek at the lower deck, given an insight into the real feelings of the ordinary seamen or a hint at the tensions that often marred relations aboard crowded vessels trapped in the ice.

Light was very hard on John Ross – sometimes, out of ignorance or prejudice, too hard. At one point, for instance, he complained of being fed on a diet of salmon instead of salt meat. “In this unpardonable manner did Capt. Ross persevere in forcing upon his men a kind of food which … was injurious to their health and totally unfit to support the physical strength.…” But Ross knew better. He recognized the signs of incipient scurvy that first spring of 1830 and moved when he could to stamp it out. As he wrote in his diary: “… the first salmon of the summer were a medicine which all the drugs in the ship could not replace.”

Light was undoubtedly closer to reality in his assessment of Ross as a haughty, unsociable, and almost hermit-like officer who treated his men with iron authority but little compassion and kept to his cabin, sustaining himself on his sponsor’s gin. He was the oldest man on the voyage – he passed his fifty-fifth year on this Arctic trip – and he hadn’t been to sea for a decade. He belonged to another, tougher era. As Light put it, “the quarterdeck of a British man of war is not the one best adapted to teach a man urbanity and civility toward his inferior!”

Ross also possessed a towering ego. He took nobody’s advice and grew angry or stubborn when any was offered. The men blamed him for getting them into such a pickle by choosing the wrong harbour. There were times, according to Light, when they came close to mutiny. Ross himself alluded to one such incident during his evidence to the select committee that examined him after his return.

To the crew, it seemed he lacked both energy and enthusiasm – qualities that distinguished James Clark Ross, his nephew. In fact, many of the expedition’s most notable discoveries were made by the younger man, though his uncle tried to grab as much of the credit as he could. This was John Ross’s great failing as an explorer; he lacked magnanimity, as Sabine had discovered over a decade before.

James Clark Ross was more popular than his uncle and far more energetic, “the life and soul of all the schemes and plans,” to quote Light. In times of stress, the men came to him for advice. He was by far the most experienced Arctic hand on board, a veteran of five previous expeditions. Only four others had had any Arctic experience, and these were limited to two years or less.

During the first two winters the ship was frozen into the ice, James Ross roved along the Boothia coastline by dogsled and small boat. Of the six hundred miles of new territory charted by the expedition, two thirds were his. It was he who discovered that Prince Regent Inlet came to a dead end in the Gulf of Boothia, he who collected most of the specimens, and he who paid daily visits in good weather and bad to the observatory that had been set up on the shore.

In the spring of 1830 he crossed a body of water (later named for him) to a bald and forbidding land later named for King William IV of England. It was actually an island, but Ross didn’t realize that – a mistake that would help to doom the lost Franklin expedition seventeen years later. He and his sledging crew followed the coast northwest to its northern point, which he named Cape Felix – a fourth nod toward his uncle’s sponsor. Here he was astonished at the spectacle of vast masses of ice blocks hurled up on the shore, as far as half a mile above the high-tide mark. What had caused this amazing pressure? Ross could not know that this was the work of the great ice stream pouring down from the Beaufort Sea – the same ice that would eventually trap Franklin’s ships.

The coastline turned toward the southwest, and Ross proceeded twenty-five miles in that direction to a promontory he named Victory Point. To the southwest open sea stretched off in the distance toward Point Turnagain. The unexplored gap was only about two hundred miles, as the crow flies, but Ross didn’t have the supplies to go farther.

His crowning achievement – the one for which he is remembered – came in the spring of 1831, when he located the North Magnetic Pole, then on the western coast of Boothia Felix. This was the great object of his ambition. “It almost seemed as if we had accomplished every thing that we had come so far to see and to do,” he declared, “as if our voyage and all its labours were at an end and that nothing now remained for us but to return home and be happy for the rest of our days.” His uncle tried to seize part of the glory for that, too, a claim that deepened the rift between them.

For the Victory, in Light’s phrase, was “a house divided.” Uncle and nephew were often at loggerheads, and the crew tended to take sides. There were times when the two Rosses, who shared the same small cabin, scarcely spoke to one another. At one point in the early spring of the second winter, when nerves were frayed and tempers undoubtedly ran high, “the fire which had been concentrating for some time in their breasts, like the lava in the craters of Vesuvius and Etna, burst forth with an explosion, which terrified the other inmates of the cabin” – in the overheated prose of Light’s collaborator, Robert Huish. The argument, whatever it was about, was settled when John Ross sent for a magnum of Booth’s gin. But two months later, the two were at such odds that James Ross refused to attend divine service and went for a walk on the shore. If Light is to be believed, he didn’t miss much. The elder Ross didn’t have Parry’s evangelism; he babbled through the prayer book so fast that Light, for one, scarcely understood a word he said.

The tensions and monotony of this two-year confinement were alleviated from time to time in the winter by the presence of the Eskimos. The seamen taught them to play football and leapfrog, to the natives’ obvious enjoyment, and, with the permission of the husbands, borrowed the women for their sexual pleasure. John Ross liked them, too, in a fatherly, stand-offish kind of way. They were, he declared, “among the most worthy of all the rude tribes yet known to our voyagers, in whatever part of the world.” But, although they kept his people warm, well fed, and free of the sexual tensions that often threaten the sanity of active men in an isolated environment, they remained barbarians to Ross.

“We were weary for want of occupation, for want of variety, for want of the means of mental exertion, for want of thought, and (why should I not say it?) for want of society.… Is it wonderful that even the visits of barbarians were welcome, or can any thing more strongly show the nature of our pleasures than the confession that these visits were as delightful; even as the society of London might be …?”

Nonetheless, their gluttony repelled him. “Disgusting brutes!” he wrote in his journal. They were uncivilized, in his definition of the word, and therefore lesser beings. “Is it not the fate of the savage and the uncivilized on this earth to give way to the more cunning and the better informed, to knowledge and civilization? It is the order of the world; and the right one.…”

The crew felt closer to the Eskimos than Ross did; but then, they were closer, in more ways than one. The steward felt that Ross was interested only in what he could get from the natives. As long as they had geographical information that he needed, he received them well, but once he got from them everything they knew, his attitude changed and they were no longer permitted aboard ship. “There was scarcely a sailor who did not draw a comparison between the treatment which they received from the savage and untutored Esquimaux in their snow built huts, and that which the Esquimaux received from the tutored and civilized Europeans in the comparatively splendid cabin of the Victory.…”

Ross made a vain attempt to move one Eskimo family who had built their snow hut close to the ship – too close to suit the captain. A hilarious confrontation followed. Ross had claimed the land in the name of the King, but neither he nor his nephew could make the Eskimos understand that the land they had lived on for centuries was no longer theirs. The white men explained the purpose of their visit, or tried to. The Eskimos in reply offered them a slice of seal blubber. The white men asked how long the family intended to stay. The Eskimos asked if they had any fish-hooks with them. The white men explained they’d taken possession of the land in the King’s name. The Eskimos remarked, chattily, that the seals were becoming very scarce. It had not occurred to them that anybody owned the land any more than anybody owned the sea or the air. They were planning an immediate trip inland in search of caribou. The naval officers, seeing their snow huts, had come to the wrong conclusion: to a white man, a house meant permanence, but the Eskimos could build one in a couple of hours. They could pack a light sled in half an hour with all their worldly possessions. No landlord or tax collector ever came to their door. The concept of permanence, of real estate, of tithe, title, and deed, was foreign to them.

All over the globe at this time, the British were attempting to foist their own concept of morality on totally different cultures. John Ross was no exception. He needed an Eskimo interpreter such as John Sacheuse, who had been on his first expedition and died shortly afterward. On Boothia Felix he found a likely candidate, a young man named Poowutyuk, whom he took aboard the Victory and endeavoured to train. But neither one had the slightest understanding of the other’s culture.

Poowutyuk thought of the ship’s crew as one big Eskimo-style family, where each individual foraged for himself. The best foraging, he quickly discovered, was in the steward’s cabin, where the food was kept. One night he appropriated a variety of foodstuffs, including a jugged hare and a roast grouse, both intended for the captain’s table. These he stuffed into his baggy sealskin trousers while he searched about for a comfortable place in which to consume them.

His eye settled on a tub, half full of flour – to him a warm sort of snow. He climbed inside in his wet furs and proceeded to demolish his trove of delicacies. Ross, deprived of his dinner, set up a hue and cry to uncover the thief, who to the astonishment of the search party eventually rose from the tub “like a ghost from the tomb,” covered from head to foot in flour.

Poowutyuk was proud that he had been able to look after himself. The idea of theft was unknown to him. As the steward said, he believed that “as the hare was every man’s property before it was killed, it was equally so afterward.” Ross didn’t see it that way. He ordered the Eskimo youth to suffer a dozen blows on the back with a stick. Poowutyuk was more puzzled than pained by this treatment. It didn’t occur to him that he was being punished. But what was going on? Was it some sort of ritual or custom? A ceremony, perhaps? At last he had it figured out. Since it was too cold for him to disrobe, and since his garments were thick with flour, and since he couldn’t reach his own back, the accommodating kabloonas were beating the flour out of him, as he had seen them beating rugs. He submitted quite cheerfully while Ross, uncomprehending, drew up a code of punishment for any more immoral acts that might occur in the future, oblivious to the fact that no one had yet been able to teach the Eskimos what, in the white man’s view, an immoral act was.

Thus passed three winters. Ross had come to the melancholy conclusion that the Victory would never escape from the ice and that they would have to sink her in the spring, hike overland to Fury Beach, subsist on Parry’s stores, and then make their way out of the inlet and into Lancaster Sound in small boats. There, he hoped, the whaling fleet would succour them.

He realized that this would be a race against time, for he had calculated his rations would run out in June. In April 1832, the crews began the exhausting drudgery of sledging supplies forward to set up a series of depots for the march north. It was a tedious business. That month they were able to move forward eighteen miles, no more, yet they had covered a total of one hundred and ten. The distance to Fury Beach – a twisting, switchback route that curled around bays, capes, and inlets – was three hundred.

On May 29, they beached the tender and moored the Victory so that she would sink in ten fathoms of water. It was a dismal moment for Ross, who had sailed on thirty-six different vessels and until this moment had never abandoned one.

Now the struggle began to get to Fury Beach before the supplies ran out. Ross put his men on two thirds of the normal rations. They slept each night in trenches dug in the snow, huddled together in their blanket bags. Ross, in Light’s phrase, was a “featherbed traveller” who rode for most of the journey on a sledge with a blind man, a cripple, and three invalids. The small size of the party was an asset; a larger one might easily have perished.

By the time they reached Fury Beach on July 1, they were weak from hunger. Boxes of Parry’s foodstuffs lay scattered along the beach, and the ravenous men rushed at them. To their anger, Ross stopped them. Up stepped Thomas, the carpenter – Ross’s one indispensable man and therefore bolder than the others – crying out that this action was “shameful and scandalous.” Light, too, was angered and disgusted by the action and said so in his memoirs, but again he was far too harsh on his captain. Ross knew that half-starved men can make themselves ill by sudden gluttony. He distributed small portions, but after he retired, his crew pilfered the rest, hiding it under their blankets. In Ross’s words, they “suffered severely from eating too much.”

Three of the Fury’s boats lay on the beach, but it was a month before the channel was clear enough to allow them to get away. They proceeded up the coast in fits and starts until, at last, relief seemed at hand. It was all illusion. On September 1, standing on a high promontory above Cape Clarence at the northern tip of Somerset Island, Ross looked out on Barrow Strait and Lancaster Sound and saw a solid mass of ice. The inlet, too, was closed. There was no help for it; they must leave the boats behind and return by sledge to Fury Beach.

They now faced a fourth Arctic winter – a dreadful prospect, for they had lost the warmth of the ship and would be forced to exist on reduced rations in a makeshift shelter – no more than a hovel of spars and canvas, banked high with a nine-foot wall of snow.

That winter, Thomas, the outspoken carpenter, died. Several more were too sick to work. Ross was left with thirteen men strong enough to shuttle provisions in seven long journeys through the snow from Fury Beach to Batty Bay, where he had cached the boats. On July 8, 1833, they set off once more, reached the boats in six days, and waited a month before a gale cleared the ice in Prince Regent Inlet. They embarked at last, rowing and sailing, three tiny dots on the grey expanse of Lancaster Sound, dwarfed by the Precambrian cliffs of Devon Island and the cloud-plumed glaciers of Baffin. To Ross, the change was magical. For the first time in four years he felt like a sailor; he had almost forgotten what it was like “to float at freedom on the seas.”

They passed the mouth of the great fiord – the longest in the world – that Parry had named Admiralty Inlet; on August 25, they reached its companion, Navy Board Inlet. Then, at four in the morning of the following day, the lookout thought he saw a sail and woke James Clark Ross, who, peering through his telescope, saw that it was indeed a ship. Everyone was awake in an instant, firing rockets; but the wind was against them, and the sail vanished over the horizon. Another sail was spotted; it too seemed to diminish. But now John Ross’s luck returned. The wind calmed; the crew rowed like madmen; at last they saw the ship heave to.

Ross was astonished when he identified the rescue vessel. She was the Isabella, the very ship that he had commanded on his first voyage in 1818. The whaling captain was equally astonished. He couldn’t believe his eyes as he told Ross that he had been dead for two years. Ross drily denied it. Now he learned that all England had long since given him up and that a rescue party under George Back was even then heading across the Canadian tundra searching for his remains.

And so they climbed on board, a scarecrow gang, unshaven, filthy, starved down to their bones, half-clothed in tattered skins. It was four years since John Ross had left the west coast of Greenland with a complement of twenty-three men; of these, all but one had managed to survive.

It was a remarkable feat. Ross’s understanding of scurvy had helped; so had the presence of the Eskimos, who were indispensable hunters. Parry’s discarded supplies were also a factor. And the very modesty of the expedition, strapped as it was for funds, contributed to its survival. In the Arctic, the Navy had indulged in a form of overkill: big ships, big crews. On his third voyage, Parry had 122 officers and men, more than five times the size of Ross’s crew. It’s doubtful that the Eskimo hunters could have kept that number alive and healthy for four winters. It was difficult enough for Ross’s party to travel north by stages, sleeping in snow trenches and tempting the buffeting seas in three small boats; a larger party could not have done it.

The tragedy is that the Navy learned nothing from Ross – nothing of the benefits of freshly killed meat, nothing of the advantages of small exploratory parties. The next major expedition to invade the heart of the Arctic archipelago would be larger than ever, and its members would die from hunger and from the scurvy that Ross and his hunters had kept at bay.

Ross returned to England to find himself a popular hero and a social lion. He dined with royalty. Hostesses scrambled to have him as a dinner guest. Four thousand fan letters clogged his post box. When he visited the continent, he was showered with medals and awards by foreign governments. A committee of parliament voted him five thousand pounds to cover his losses. Another eighteen thousand went to Felix Booth to cover his expenses, while the crew members received double pay. Booth was made a baronet, Ross a Knight Commander of the Bath.

The expedition’s accomplishments were considerable, especially the discoveries and charts of James Ross, whose map of Boothia, for instance, was standard for the rest of the century. As for the North West Passage, John Ross hadn’t found it and was prepared to dismiss it. When a parliamentary committee asked him if its discovery would be of public benefit, he responded bluntly, “I believe it would be utterly useless.”

Ross might be a public hero, but he was still a pariah among his peers. In the Navy’s view he had not behaved like a gentleman. He had tried to seize too much credit for the explorations and discoveries of his nephew. He had seemed too eager for monetary gain, while his nephew, appearing before the select committee, made a point of showing his disinterestedness. “Ross will do himself harm by the eagerness he has shown on this matter,” John Franklin wrote to his new wife, Jane, “and no one is more annoyed at it than young Ross, of whom the uncle is very jealous.”

Ross published his journal himself, without the help of John Murray, and proceeded, to the undoubted horror of his fellow officers, to use high-pressure methods to market it. He opened a subscription office in Regent Street and even engaged agents to peddle it from door to door, a most unseemly procedure in naval etiquette and one that caused Barrow to attack him for his “lust for lucre.” Another naval author, Captain Beaufort, made a point of telling the parliamentary committee that he had received no money from the publication of his own book because “I did not think that materials acquired in the King’s service ought to be sold.”

The harshest blast, predictably, came from Barrow. In a long essay in the Quarterly Review he attacked the narrative as “ponderous,” called Ross a “vain and jealous man,” and railed against “the cold and heartless manner in which the bulk of narrative is drawn up – the unwillingness to give praise or make acknowledgement even to him [Ross’s nephew] on whom the safety of the expedition mainly depended.”

These criticisms were well taken, but Barrow showed his own vanity and jealousy when he attacked the expedition as an “ill-prepared, ill-conceived … and ill-executed undertaking,” castigated Ross as “utterly incompetent to conduct an arduous naval enterprise for discovery to a successful termination,” and declared that the results of his four-year Odyssey “are next to nothing.” The same, of course, might have been said of Parry’s later voyages, and with more truth. But Parry was Barrow’s man and a gentleman; Ross was not. The Navy’s failure to analyse the very real strengths of his expedition was to cost it dear in the years to come.

In John Ross’s absence the world had moved on. The railway locomotive had come into its own – a harbinger of the age of steam. Michael Faraday had discovered the principle of electricity, and two scientists had separately invented chloroform. The first sewing machine had been patented. The Empire had abolished slavery. George IV was dead, and John Franklin had left the Arctic wastes and the London drawing-rooms for the salubrious waters of the Mediterranean.

Within a year of his return from the North, the widowed explorer had renewed his acquaintance with his wife’s friend Jane Griffin and proposed marriage. As he put it to his future father-in-law, a wealthy silk weaver, “The various interchanges of ideas and sentiments which have recently taken place between Miss Jane and myself have assured us not only of entertaining the warmest affection for each other, but likewise there exists between us the closest congeniality of mind, thought and feeling.…”

In short, they were in love. They were married on December 5, 1828, and spent their honeymoon in Paris, where it was remarked that Franklin seemed remarkably plump and comfortable for a man who had once starved almost to the point of death.

Jane Griffin was then thirty-six years old. In her younger days, she had had a host of suitors, for she was an elegant and lovely woman, a little shy but also highly intelligent. There were those who would come to think of her as “a tall, commanding looking person, perhaps with a loud voice too!” She was not flattered by this “visionary Lady Franklin” as she termed it, for she was small, slight, and soft spoken. Her reputation was at odds with her physical presence.

Before she met John Franklin she had turned down all aspirants for her hand, an act she came to regret in the case of at least two. One of these rejected suitors was Peter Mark Roget, who later distinguished himself by creating the thesaurus that still bears his name. When he married someone else, Jane Griffin confided to her diary, “… the romance of my life is gone – my dreams are vanishing & I am awakening to sober realities & to newly-acquired wisdom.”

She was a confirmed, indeed a prodigious, diarist and correspondent and a voracious reader who thirsted after wisdom. She devoured books (295 in one three-year period) – books on every subject: travel, education, religion, social problems, but never novels, for novels in that day were considered frivolous, especially for a serious-minded young woman.

She was incurably restless and had travelled a great deal with her father before her marriage. In her voluminous journal she conscientiously noted everything in her cramped, spidery hand – every plaque, every historic tablet, every monument, every church, the chief products and industries of every town, even the distances covered. She believed in self-improvement. At nineteen, she had worked out a plan to organize her time and enrich her mind, with every moment given over to some form of study.

Jane Griffin belies the stereotype of the Victorian woman of means, languid at her needlework, simpering fetchingly at the society balls. A description of her multitude of activities leaves one slightly out of breath, for she indulged herself in a kaleidoscope of worthy interests. She was a member of the Book Society. She took lectures at the Royal Institution. She visited Newgate Prison and the Vauxhall Gardens. She attended meetings of the British and Foreign School Society. Nor did she take a back seat at fashionable dinner parties. She took on the redoubtable Dr. Arnold on the subject of fagging (of which she disapproved) and reprimanded the family of Benjamin Disraeli when they repeated some gossip about John Franklin’s last parting from his dying wife. Her voice trembled with anger as she “replied to all this unfeeling nonsense.” She did not know Franklin well at this point; but they had met on occasion, and she felt it proper to give him a going-away present of a silver pencil and a pair of fur-lined gloves.

She was a shrewd observer of the human species and described almost everyone she met. John Ross, for instance, was “short, stout, sailor-looking & not very gentlemanly in his person, but his manners & his language are perfectly so; his features are coarse & thick, his eyes grey, his complexion ruddy & his hair of a reddish, sandy hue. Yet notwithstanding his lack of beauty, he has a great deal of intelligence, benevolence & good humour in his countenance.” She would revise that opinion in her later years and even ban Ross’s portrait from her gallery, but her assessments, while sharp, were reasonably benign. Franklin’s friend John Richardson “was not well dressed – & looks like a Scotchman as he is – he has broad & high cheek bones, a widish mouth, grey eyes & brown hair – upon the whole rather plain, but the countenance thoughtful, mild & pleasing.…”

In the months before her marriage, the peripatetic woman set off with her father on another trip, this time to Russia. Her fiancé would have liked to accompany her on the same ship, but she did not feel it proper and, in her peremptory way, put him off. Her objection, she told him, arose “from a strong sense of impropriety in the arrangement, as well as from a conviction that we should all be placed in a number of awkward and disagreeable situations during long and rough voyages and journeys which it would be extremely unpleasant for me to partake in and impossible to avoid.…” He joined her in St. Petersburg, where she did her best to note down not only everything she saw but also everything she didn’t see. They were married immediately after their return.

In many ways, Jane Griffin was the exact opposite of her complacent, easy-going, humourless husband. “What an irritable, impatient creature I am by comparison,” she told him. In that odd partnership, hers was the stronger will, but she was clever enough not to show it. “You are of a much more easy disposition than myself,” she had written before their marriage. “… It must be my province, therefore, … to combat those things that excite my more sensitive temper; while it must be and shall be yours … to control even this disposition whenever you think it improperly excited and to exert over me … the authority which it will be your privilege to use and my duty to yield to. But do I speak of duty? You are of too manly, too generous, too affectionate a disposition to like the word and God forbid I should ever be the wretched wife who obeyed her husband from a sense of duty alone.” Her wedding ring, she told him, would not be “the badge of slavery, but the cherished link of the purest affection.”

She loved him and she was fiercely ambitious for him. He became an extension of her. “I never can be a happy person,” she once wrote, “because I live too much in others.” Certainly she lived in her husband, and, when it was necessary, pushed and prodded him along in her subtle fashion.

After two years of idleness, in which he was offered and turned down a commercial job in Australia, Franklin was at last given command of a twenty-six-gun frigate in the Mediterranean. He left early in 1830. Jane was not allowed to travel with him but had no intention of staying home. She joined him the following autumn and almost immediately plunged into a whirlwind of Middle Eastern travel through Greece, Egypt, Turkey, Syria, Asia Minor, and the Holy Land. Franklin hastened to explain that she travelled “not out of vulgar curiosity … but in order to inform herself and broaden her mind so she can be more interesting to others.…”

When Sir John returned to England in 1833 after his Mediterranean service, Lady Franklin was in Alexandria, preparing for a trip up the Nile. That did not stop her from directing his career by long distance. At her suggestion, he went, rather diffidently, to see the new First Lord of the Admiralty, Sir James Graham, to ask for further employment. Sir James, besieged by scores of other half-pay officers demanding the same thing, told him there was nothing available.

“You will fancy, my dearest, that your shy, timid husband must have gathered some brass on his way home,” he wrote to his wife, describing his attempt, “or you will be at loss to account for his extraordinary courage.” He had done it, he said, “because I knew you would have wished me to do so.…”

He had been planning to join her at Naples, but she would have none of it. Only by staying in England, close to the Admiralty, could he be sure of getting a posting. “Your credit and reputation,” she declared, “are dearer to me than the selfish enjoyment of your society.”

Now she pushed him further. A ship or a station were not comparable, she told him, to an expedition, preferably another Arctic exploration. “The character and position you possess in society and the interest – I may, say celebrity – attached to your name, belong to expeditions and would never have been acquired in the ordinary line of your profession.” An expedition by ship this time, she felt, would be best. She would not want him to ruin his health “if you should feel to be unequal to any of your former exertions.” On the other hand, “a freezing climate seems to have a wonderful power of bracing your nerves and making you stronger.”

She badly wanted him to go after the ultimate prize: the North West Passage. There was talk, she said, of reviving the search. She made it sound like a contest, a prizefight, perhaps. James Clark Ross was a contender, for either the Passage or the Antarctic. He could take only one; somebody else would surely step in and undertake the other. Sir Edward Parry was on his way back from Australia (he had taken the job that Franklin had turned down), “and he will be working hard for the vacancy or perhaps Richardson. I wish him well and young Ross also.… I grudge them nothing of their well-earned fame. But if yours is still dearer to me.… You must not think I undervalue your military career. I feel it is not that, but the other, which has made you what you are.…”

In spite of what she said, the Navy had, for the time at least, given up all intention of seeking the Passage. Public excitement over Arctic heroism was flagging. The Edinburgh Review captured the general sentiment in 1835 when it declared that the effort and funds expended on the search might be better applied to other purposes: “It may doubtless gratify the national vanity to plant the standard of England even upon the sterile regions … but … if no advantage can be gained by revisiting such inhospitable regions, it must be admitted that the mere knowledge of their existence, and of the indentations of their shores, is comparatively useless, and utterly unworthy of that sacrifice or risk of life and resources by which it may have been acquired.”

The British government clearly agreed. After a second stint of idleness, Franklin was offered a post as governor of Antigua, a tiny palm-fringed speck in the Caribbean. That was too much for Lady Franklin – an almost insulting comedown for an Arctic hero. To her it was a minor post, no more important than that of first lieutenant on a ship of the line. When a better offer came, the Franklins accepted it. At least it sounded better: governor of Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania), a penal colony off the south coast of Australia. The day would come when both would bitterly regret the decision.

In June 1833, when Franklin was preparing to leave his Mediterranean command and return to England, George Back arrived at Fort Alexander on Lake Winnipeg to launch a rescue operation for John Ross, who had been missing for four years. Here, a twenty-five-year-old Hudson’s Bay clerk, Thomas Simpson, wrote down his first impression of the explorer, a generally favourable assessment, tinctured with a touch of the fur trader’s suspicion of all naval men. “He seems a very easy, affable man,” Simpson wrote, “deficient, I should say, in that commanding manner with the people so necessary in this savage country. From my soul I wish them every success in the generous and humane objects of the expedition.…”

Five years later, the same Thomas Simpson had revised his opinion. He attacked Back’s account of the expedition as “a painted bauble, all ornament and conceit, and no substance.” As for the explorer himself: “Back, I believe to be not only a vain but a bad man.”

These remarks, written to his favourite brother, Alexander (the two enjoyed “a Damon and Pythias relationship”), tell as much about Thomas Simpson as they do about George Back. The romantic young clerk, frustrated in a routine job in a backwater trading post, was burning with ambition to match the deeds of Parry and Franklin. Back must have appealed to him as a glamorous figure, right out of history. The following spring, when news arrived of Back’s discovery and successful exploration of the Great Fish River, Simpson bubbled with praise. It was “greater than any of us in the North anticipated.” Back, he felt, deserved and would get a knighthood.

That was before Simpson himself became an explorer. A highly emotional man, unstable at times, immoderately ambitious, he would reach the point where his own craving for fame would make him jealous of Back – afraid that the older explorer might outdo him in bold deeds and discoveries. The time would also come when Back himself would fail and Simpson would rejoice, but that was in the future. In 1833, Back was a rescuing angel.

Concern over John Ross’s long absence had reached a peak in England the previous year. His brother George, the father of James Clark Ross, worried about his relatives’ fate, had petitioned the King to launch a rescue operation. That the government declined to do; the unfortunate Ross was not the Admiralty’s favourite explorer, and the general feeling at that level was that he had blundered and died. John Barrow was convinced that the entire expedition had perished the first winter. Would Parry, in a similar case, have been regarded so carelessly – or Franklin? Certainly not Franklin, as events were to prove.

But the government in the end could not resist public pressure. It finally pledged two thousand pounds toward a rescue operation, but only if the Hudson’s Bay Company would provide supplies and equipment. The rest of the cost – three thousand pounds – was raised by public subscription.

Back’s party numbered only twenty. He brought three men from England, picked up four soldiers in Montreal, and recruited the others at Norway House. His only fellow officer was a medical man, Dr. Richard King, a sardonic travelling companion who was to bear the brunt of the expedition. King’s experience with Back turned him into a blunt critic of both the Royal Navy, for its exploring methods, and the Hudson’s Bay Company, for its treatment of the native population, an attitude that pitted him against two Arctic Establishments and rendered all his criticisms ineffective.

King became an exponent of land-based travel as opposed to exploration by naval vessels. He thought it would be much easier to trace the course of the North West Passage by moving along the coastline on foot or by dogteam rather than trying to bull cumbersome ships through masses of shifting ice. He believed fervently that small parties living off the land were preferable to large ones dragging heavy equipment or heavy vessels trying to manoeuvre in ice-blocked channels.

He had the maddening quality of being shown to be right after the fact, but at the time few were prepared to listen. He was prickly, abusive, and ungentlemanly enough to take his cause to the public rather than to pursue it quietly in the back rooms of the Admiralty. For twenty-two years he ranted on, vainly attempting to mount various expeditions to explore along the continental edge, with himself as leader. And he was a good leader; while Back headed off in a light canoe as a one-man advance guard, King was in charge of organizing the supplies and the main party.

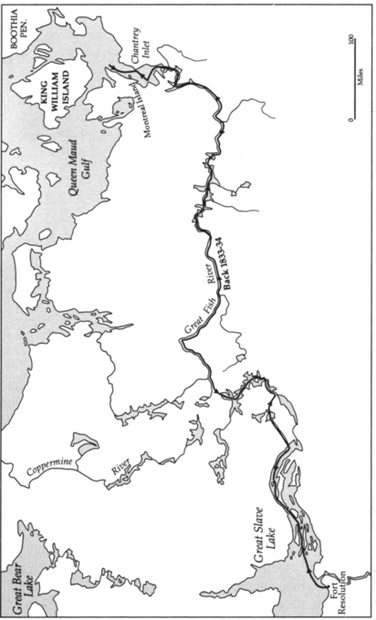

The fur traders were convinced that the pair were off on a wild-goose chase. On his first northern trek with Franklin in 1820, Back had heard from an old Indian warrior named Black Meat of a mysterious river, known as the Great Fish, that was supposed to wriggle through the Precambrian schists of the naked tundra northeastward to the Arctic Ocean. It was his plan to find this river, follow it to its mouth, cross over by land to Prince Regent Inlet, and look for Ross’s party.

The company men were sceptical that any such river existed, a scepticism supported by the tension that existed between the fur trade and the Navy. The naval officers were seen as interlopers and amateurs, blundering about in a hostile land and writing romantic accounts of supposed hazards that voyageurs considered to be part of everyday life.

As one Hudson’s Bay man, William Mactavish, wrote to his family during Back’s absence in 1834: “You’ll hear what a fine story they’ll make out of this bungle, they will you may be sure take none of the blame themselves.… They will return next summer and like all the other Expeditions will do little and speak a great deal.” Mactavish didn’t like Back. He thought him heartless and snobbish. Back, he said, despised those who helped him because of their lack of formal manners.

But Back persisted in his search and early in 1834 found the headwaters of the mysterious river. In April a dispatch caught up with him reporting that Ross had been found alive. That left him free to devote himself to the expedition’s secondary purpose: to explore the northeast corner of the continent.

That summer, Back and King headed down the Great Fish River into unexplored territory, “a violent and tortuous course of five hundred and thirty geographical miles, running through an iron ribbed country without a single tree on the whole line of its banks.…” The river expanded into large lakes with clear horizons, then narrowed again into a frothing maelstrom “most embarrassing to the navigator.” Back counted no fewer than eighty-three falls, cascades, and rapids before it poured its waters into Chantrey Inlet.

To the north and to the east, Back could see land in the distance – Boothia Felix, in fact. He wrongly suspected a water passage led through it, but it was too late in the season to contemplate an attempt at such a North West Passage, nor did his instructions allow it. King disagreed with his leader; he was convinced that Boothia was a peninsula, not an island; again he turned out to be right. John Ross had already learned it from the Eskimos.

King William Land could also be seen to the north, though neither man knew what it was. King wanted Back to move out of Chantrey Inlet and explore the coastline eastward. Had he done so he would probably have discovered that King William Land was an island, separated from Boothia Felix by a channel. Years later it was discovered that this was the only practical route through the North West Passage, but that information came too late to prevent the greatest of all Arctic tragedies.

Back did not continue beyond Chantrey Inlet. With no fuel and only a little water, the expedition retraced its steps and returned to England the following year, 1835. King was not happy. He and his leader were not on the best of terms, and he clearly felt that Back could have done better. In 1836 he proposed that he lead an expedition with no more than six men down the Great Fish River to explore Boothia Felix and settle for all time the question of whether it was a peninsula or an island. Until that was established, “I consider it would be highly impolitic to send out an expedition on a large scale.” A small expedition could be mounted for a thousand pounds; Back’s had cost five times that. There were precedents in the journeys of both Mackenzie and Hearne. But King was, as usual, undiplomatic in the proposal he made to the Geographical Society and in the book that followed: “The question has been asked, how can I anticipate success in an undertaking which has baffled a Parry, a Franklin, and a Back? … if I were to pursue the plan adopted by [them] … of fixing upon a wintering ground so situated as to oblige me to drag a boat and baggage over some two hundred miles of ice to reach the stream that is to carry me to the scene of discovery, and, when there, to embark in a vessel that I knew my whole force to be incapable of carrying … I very much question if I could effect so much.”

George Back explores the Great Fish River, 1833-34

This gratuitous slur on the reputations of the three naval officers who occupied the pinnacle of the pantheon of Arctic explorers was enough to doom King’s plan. Besides, Back – who had now been promoted to captain and earned the Society’s gold medal – had plans of his own. At his urging, the Navy did exactly what the waspish doctor advised against. It mounted another large and expensive expedition. George Back set off in the 340-ton Terror with orders to winter at Repulse Bay and then to drag boats across the isthmus at the base of the Melville Peninsula to explore the far shore.

The result was an unmitigated disaster. Back, who failed to reach his first objective, was trapped in the ice for ten months, most of them fraught with terrible dangers and hairbreadth escapes. The ice captured him and played with him, and once hurled his battered vessel forty feet up the side of a cliff. In the spring, when the pack broke up, the Terror was attacked – there is no other word for it – by a great submerged berg that set her on her beam-ends and almost destroyed her before the sea again grew calm.

The splintered ship, leaking, waterlogged, and almost impossible to steer, had no chance of getting back to England. Back headed for the Irish coast and, with only hours to spare, managed to ground his sinking craft on an Irish beach. This was his last expedition. Knighted by the new queen, he passes from the Arctic picture. His critic, Richard King, fared no better. Vindicated by history, he was shunned by the Arctic Establishment.

Meanwhile, the Hudson’s Bay Company was bestirring itself, suddenly mindful of a clause in its original charter charging it with the task of discovering a North West Passage. Since such a Passage had no commercial value, the company had generally ignored that obligation, but now its licence to trade beyond its original territorial boundaries was about to expire. It was time to take action.

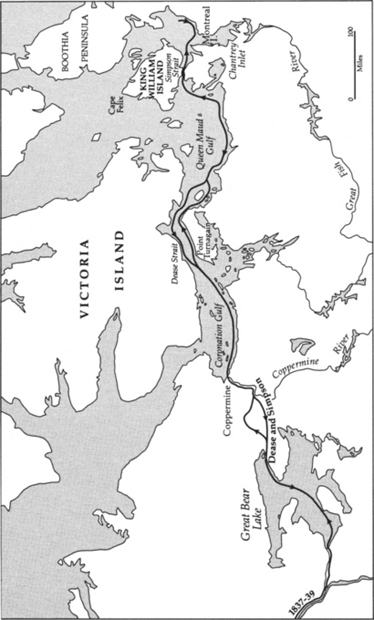

It certainly didn’t want King. It wanted one of its own – two, in this case. Peter Warren Dease, an old company hand who had been with Franklin on his second expedition would supply the stability. Thomas Simpson, the ambitious young cousin of the governor, would supply the energy. Their first task would be to map the unexplored western section of the Arctic coastline, from Prudhoe Bay, Alaska – Franklin’s farthest point – to Point Barrow at the very northern tip of the Alaskan peninsula.

Young Simpson was not happy with the idea of a divided leadership. He wanted all the glory for himself. Raised in poverty, a sickly youth tending to consumption, he had managed to overcome both obstacles. He graduated from King’s College, University of Aberdeen, with honours and by 1836 was as tough as any of the Canadian voyageurs. But he also suffered from an intellectual pride that came close to snobbery and from a suspicious nature that bordered on paranoia.

Simpson was one of those men who believe themselves to be surrounded by dark forces conspiring against them. Although he owed his position to his cousin George Simpson, the “Little Emperor” of the Hudson’s Bay Company, he was convinced his powerful relative was inhibiting his advancement. He had been brought to Canada seven years before as Simpson’s personal secretary. By accompanying the governor on his journeys he had himself become a seasoned northern traveller. But he described the Little Emperor as “a severe and most repulsive master” who, he was convinced, was leaning over backward in his treatment of him to frustrate any charges of nepotism. Young Simpson tended to be hot-headed and intolerant. In 1834, at Red River, he had managed to provoke the Métis population, which he held in contempt, even going to the point of engaging in fisticuffs with one young mixed-blood, touching off a fracas that was calmed only by the diplomacy of the governor himself. He did not like mixed-bloods, a failing that would one day destroy him.

In spite of his youth, Thomas Simpson was convinced that he should be the sole leader of the party exploring the northern coast of Alaska. He blamed the jealousy of senior company officers and the intransigence of his cousin for failing to get what he felt was his due. In fact, George Simpson had a high opinion of his young relative, who, he had noted, “promises [to be] one of the most complete men of business in the country.” But the governor was also aware of Thomas’s deficiencies. Peter Dease may have been “rather indolent [and] wanting in ambition,” but “his judgement is sound, his manners are more pleasing and easy than many of his colleagues,” and he was also steady in business and “a man of very correct character and conduct” – in short, just the man to act as a steadying influence on the impetuous and mercurial Thomas.

Thomas Simpson was undeniably industrious. A stubby, burly figure, he was bursting with energy. To prepare himself for the expedition, he spent the late fall of 1836 at Fort Garry, toughening his body and studying astronomy, surveying, and mathematics. He even worked on his literary style (since he would be required to keep a journal) by reading the works of Sir Walter Scott. He left Fort Garry on December 1, 1836, and joined Dease, a chief factor of the company in the Athabasca region, sixty-two days later after a journey of 1,277 miles. He had now reached the zenith of his ambitions, for he was about to realize “some, at least, of the romantic aspirations which first led me to the New World.”

A lesser man – or a less ambitious one – would never have reached Point Barrow that summer. By July 31, 1837, the party was only halfway between Franklin’s Farthest West and its objective. The men were played out. Dease wanted to turn back. But Simpson persuaded him to stay behind while he and five others made a dash to the point.

They plunged off into the fog, travelling light and fording their way through a tangle of icy rivulets until, to Simpson’s “inexpressible joy,” they met a group of Eskimos. Without their help they would never have made it. In the natives’ skin boats, which would float in half a foot of water, they battled ice and tides until, early on the morning of August 4, Simpson, with “indescribable emotions,” saw in the distance the long spit of gravel hummocks that was Point Barrow.

As he wrote to his brother that fall in immodest triumph, “I and I alone, have the well-earned honour of uniting the Arctic to the great Western Ocean.…” He wanted a promotion and wrote to the governor asking for a chief tradership, pointing out that he had “the exclusive honour of unfurling the Company’s flag on Point Barrow” and begging his cousin not to “reject my just claims, although I am one of your own relatives.”

The absence of any reply confirmed Simpson in his dark suspicions. “Had I been in His Majesty’s Service,” he wrote to a friend, “I should have expected some brilliant reward, but the poor fur trade has none such to bestow.” After his return, he spent the winter at Fort Confidence on Great Bear Lake on what he called “the happiest terms” with the good-natured Dease and his family. But, he added, “it is no vanity to say that everything which requires either planning or execution devolves upon me.” Dease, he told his brother, was “a worthy, indolent, illiterate soul and moves just as I give the impulse.”

He occupied those long, dark days reading Plutarch, Hume, Gibbon, Shakespeare, Smollett, and “dear Sir Walter.” A rumour reached him that William IV was dead and the Empire had a new young queen, but nothing official came from the company’s council, which appeared to ignore him. “They do not deserve such servants as we are, as they do not know how to treat us,” he wrote to his friend Donald Ross. “Have we been sent to the Arctic regions that our means & lives should be the sport of a tyrrannical [sic] Council?”

Their task the following summer was to try to fill in some of the unexplored territory to the east, beyond Point Turnagain, the farthest spot that Franklin had been able to reach in 1820. In this they were not successful. Once again, the energetic Simpson persuaded the easy-going Dease to let him go a little farther on foot beyond the point where the boats gave up. Again he travelled light, with a handful of companions, but this time it didn’t work out. His men grew lame, and there were no Eskimos to help out. Simpson saw a vast bulk of land across the sea to the north, which he named Victoria Land after the new queen. He also saw open water farther to the east but had no idea where it led. Again he blamed Dease for not pushing forward with sufficient vigour to complete the job. “All that has been done is the fruit of my own personal exertions,” he told his cousin. He liked Dease for his upright character but considered him and his followers a dead weight. “My excellent senior is so much engrossed with family affairs,” he wrote, “that he is disposed to risk nothing; and is, therefore, the last man in the world for a discoverer.”

What Thomas Simpson wanted, and what he never achieved, was to risk everything – but only as sole commander of an expedition. If he could only go a little farther and explore the rest of that unknown section of coastline; if he could only link it with the explorations that had been made from the east! Then, he was certain, he would win the accolade. He knew he must be patient. If he could accomplish something more the following summer, then, surely, Dease would be recalled and he would be put in sole charge.

When the two set off again in 1839, Simpson found, to his surprise and delight, that Coronation Gulf, which had been a solid sheet of ice the year before, was partially open. So was the grand strait between the continent and Victoria Land, soon to be named for Dease. On they went across Queen Maud Gulf, expecting the coastline to lead them north along King William Land to its northernmost point at Cape Felix, named by James Clark Ross nine years before. But now a narrow strait, soon to be named for Simpson, beckoned to the east. They followed it and, to Simpson’s joy and excitement, found that it led to Chantrey Inlet and on to the mouth of Back’s Great Fish River. Three days later they arrived at Montreal Island in the estuary and discovered Back’s cache of pemmican, chocolate, and gunpowder.

Now Simpson indulged in an orgy of exploration. He pushed eastward another forty miles to the mouth of the Castor and Pollux River, then doubled back to explore the south shores of both King William and Victoria lands. In just three years he had filled in most of the blank spaces on the coastal map. He had closed the western gap, connected Franklin’s explorations with Back’s, and come within an ace of discovering the whole of the North West Passage, though he did not recognize it. He had actually come in sight of Rae Strait (yet unnamed), which separates King William Island from Boothia Peninsula. Who knows what he might have accomplished if he had made a fourth foray into that unknown realm?

As it was, he had made two errors. He thought Boothia was an island and that a strait of water led directly into Ross’s Gulf of Boothia. If that were true, there were only about a hundred miles left unexplored. Actually there was no strait. Boothia was a peninsula, and there were seven hundred miles of coastline awaiting exploration to the only gap in Boothia – the still unknown Bellot Strait. More seriously, he also made the mistake of believing that King William Land was connected to Boothia and that there was no passage leading south along its eastern coastline.

Dease and Simpson’s explorations, 1837-39

He didn’t want to share another expedition with Dease. “Fame I will have,” he told George Simpson that fall of 1839, “but it must be alone. My worthy colleague on the late expedition frankly acknowledges his having been a perfect supernumerary.” Then he added a sentence that takes on a significance in the light of the tragedy that was to follow. “To the extravagant and profligate habits of the half-breed families,” he wrote, “I have an insuperable aversion.”

The attainment of all his ambitions was within his grasp. Peter Warren Dease had gracefully bowed out. Simpson proposed a daring plan to the directors of the company in London. He would take a dozen men down the treacherous Great Fish River and from its mouth sail on through the supposed water passage he thought led to the Gulf of Boothia; from there he would push on through Fury and Hecla Strait to York Factory on the western shores of Hudson Bay. He was prepared to spread the task over two seasons and finance it with five hundred pounds of his own money, a small fortune at that time. Had he done so he would almost certainly have discovered his errors, learned that King William Land was an island, and that a safe channel existed off its eastern shore – a piece of information that would have saved the doomed Franklin expedition from being caught in the great ice stream that clogs the alternate route on the western side.

Simpson was convinced he was on the verge of conquering the Passage. “I feel an irresistible presentiment that I am destined to bear the Honourable Company’s flag fairly through and out of the Polar Sea,” he wrote to his cousin. But the Little Emperor did not reply. The impetuous young explorer fidgeted all through the long winter, waiting for some praise or gratitude. None came. By June of 1840 he could stand it no longer. That summer he decided to go to England to press his case.

What he did not know – what he would never know – was that even as he planned that trip to London, the Governor and Committee of the company were dispatching a congratulatory letter to him approving his plan. He was to be given sole command of the new expedition and everything he needed to accomplish his goal.

The letter never reached him. That summer, while he was riding through the country of the Dakota Sioux with four heavily armed mixed-bloods, tragedy struck. The details are murky. The two survivors swore that Simpson had been taken sick, accused two of the party of plotting to kill him, and shot them dead. The witnesses fled, returning later with a larger party to find Simpson himself dead of gunshot wounds, his rifle beside him. The authorities brought in a verdict of suicide.

Since that day, Thomas Simpson’s death has been a matter of mystery and controversy. His brother Alexander, to whom he had poured out his soul so often by letter in those sunless days at Fort Confidence, was convinced he had been murdered. The half-breed assailants, Alexander claimed, were planning to steal the secret of the North West Passage, which was among Thomas’s papers. That is a little too melodramatic and far-fetched to hold water. What secret? The Passage was not a gold mine to be pounced upon in the dark of the night and looted. In any case, Simpson’s theories were wrong.

Undoubtedly there was a quarrel, and that is understandable in the light of Simpson’s known dislike of mixed-bloods, whom he termed “worthless and depraved.” There is also Simpson’s own mercurial character to be considered, especially in the light of the fancied slights, the frustrations, and the long tensions of an Arctic winter. He had talked of the Métis and “the uncontrollable passions of [their] Indian blood.” He himself was subject to similar passions. Was it murder or suicide? And what was the cause? No one will ever know. The irony is that his considerable triumphs had not been ignored, as he believed. In England the gold medal of the Geographical Society as well as a pension of one hundred pounds a year awaited him. He did not live to receive either but went to his grave a victim of impossible distances, leisurely communication, and his own paranoia.

Van Diemen’s Land in 1836 was nothing more than a vast and horrible prison, and John Franklin was its warden. The colony harboured 17,592 convicts and 24,000 “free citizens,” some of them former convicts themselves. And each year another 3,000 convicts arrived.

It was a long way from the clean, cold air of the Arctic, and the living conditions for almost half the population were far more appalling than those suffered by the Eskimos, shivering on the barren windswept islands of northern Canada. To Franklin, there were worse horrors than besetment among the floebergs. The man who would not hurt a fly was so distressed by the lot of the convicts that, according to his future son-in-law, Philip Gell, “more than once his health was shaken under the burden.” Gell added that “he found another source of hopeless sorrow in the fate of the perishing Aborigines.” There were but ninety-seven left in the colony.

Franklin’s six years in Van Diemen’s Land were the most painful of his life. Early in his tenure he set down his impressions of the colonists, who, he found, displayed “a lack of neighbourly feelings and a deplorable deficiency in public spirit.” The Franklins, especially Lady Franklin, didn’t fit into the snobbish, ultra-conservative, and generally unsophisticated upper-class clique, whose members thought him a weakling and saw her as a meddler. To the bureaucrats who ran the government, the new governor appeared inept, inexperienced, and dangerously liberal-minded. He worked hard. He took his job seriously. But he was no match for the Byzantine manoeuvrings of a tightly knit colonial service.

The real problem was Lady Franklin. She did not act the role of the conventional governor’s wife, whose duties had historically consisted of dressing smartly, making and receiving calls, and entertaining in public. Her contemporaries found her lofty and a trifle preachy. Jane Franklin had little use for the brittle chit-chat of the drawing-room; she wanted to discuss philosophy, art, and science. Her own room at Government House was described by one visitor as “more like a museum or a menagerie than the boudoir of a lady,” being cluttered with stuffed birds, aboriginal weapons, geological specimens, and fossils.

She flung herself into her usual round of activity, visiting museums, prisons, and educational institutions, which brought down a hail of criticism. She formed a committee to look into the conditions endured by women convicts, but the governess she chose to run it defected after a newspaper article claimed it wasn’t suitable work for unmarried ladies. When she showed an interest in the aborigines, another paper attacked her as “unwomanly.” She tried to start a college at New Norfolk but was frustrated when the colony’s insidious colonial secretary, Captain John Montagu, insisted that public money could not be squandered on such a project. “A more troublesome interfering woman I never saw,” Montagu said privately. She hated snakes and tried to rid the island of them by offering a bounty of a shilling a head out of her own pocket. That sort of gesture prompted one critic to remark that she was “puffed up with the love of fame and the desire of acquiring a name by doing what no one else does.” The project petered out; there were just too many snakes. No doubt Lady Franklin felt that the worst ones were to be found in the Colonial Office itself.

In her travels, which were extensive and exhausting – she was away for as long as four months at a time – she went where no woman had gone before: to the top of Mount Wellington in Australia, across the wild country to the west coast of Van Diemen’s Land, overland from Melbourne to Sydney by spring cart and horseback, careless of hardship, ever curious, always questioning, and compiling statistics in her voluminous journals on everything from the price of sheep in Yass to the flight patterns of the white macaw.

It was inevitable that she should be considered the power behind the throne in Van Diemen’s Land. One hostile newspaper went so far as to call her husband “a man in petticoats.” In the smouldering antipathy between Franklin and his colonial secretary, Montagu, she was the tinderbox. Matters came to a head in the winter of 1841-42 when Franklin, on Montagu’s advice, dismissed a popular surgeon for dereliction of duty. The doctor’s friends got up a petition charging that the dismissal was unjust. Lady Franklin evidently agreed. After much thought and no little vacillation, the governor recanted, to the fury of Montagu, who was convinced that Jane Franklin was behind the move. From then on the two were at odds.

Franklin was no match for the powerful and wily civil servant, who had a section of the press on his side. Montagu engaged in a campaign of obstruction that could have one ending only. After receiving a pompous note in which the colonial secretary came very close to calling him a liar and a weakling, Franklin sacked him. It was actually only a suspension; the Secretary of State for the Colonies in London, Lord Stanley, would have the final word. Unfortunately for John Franklin, the same ship that carried to England his report on Montagu also carried Montagu himself, burning for revenge, armed with a thick sheaf of documents and memos, and crying out, “I’ll sweat him. I’ll persecute him as long as I live.”

Montagu’s friends in the Tasmanian press backed him. The Cornwall Chronicle published an article entitled “The Imbecile Reign of the Polar Hero,” while the Colonial Times put the blame squarely on the shoulders of the Arctic Hero’s wife: “If ladies will mix in politics they throw from themselves the mantle of protection which as females they are fully entitled to. Can any person doubt that Lady Franklin has cast away that shield – can anyone for a moment believe that she and her clique do not reign paramount here?”

There was worse to come. Lord Stanley backed Montagu, offered him another job, and issued a stinging rebuke to Franklin – a public horsewhipping, in one observer’s words. As if that were not humiliation enough, he let Montagu have a copy of his reproof, which Montagu rushed to Tasmania by immediate post before Lord Stanley got around to sending it officially. Thus several copies were passed about in pro-Montagu circles, with many a nudge and snigger, several months before the explorer received the dispatch himself.

Montagu went further. He also shipped out a three-hundred-page packet of the dispatches, letters, and documents he had used to shore up his case. This arrived in April 1843 and was held in a bank in Hobart, the capital, where favoured customers were allowed to peruse it in secret. Franklin was never able to see the packet, in which Montagu called him a “perfect imbecile”; but he knew it was there, as did everybody else in town, and he also knew through hearsay what it contained.

By this time Jane Franklin was in a state of nervous prostration and Franklin himself, trying to appear outwardly cool, was inwardly in turmoil and close to a breakdown. The press was predicting his imminent recall, and on June 18, the Colonial Times announced it under the headline “GLORIOUS NEWS!” A newspaper had arrived from England reporting the gazetting of the explorer’s replacement, but so glacial was the speed of the official post that Franklin himself had no official word for another two months. In fact, his replacement arrived three days before he was formally told – in a six-month-old dispatch – that his term of duty was ended. After all this humiliation, it was a relief to be out of Government House.

In spite of the controversy, Franklin remained personally popular. Two thousand cheered him off when, on January 12, 1844, he sailed for England. More than ten thousand signed an address of farewell. And when, a decade later, Lady Franklin appealed for funds for the search for her lost husband, the Tasmanian people contributed seventeen hundred pounds.

But in 1844, Franklin had reached the nadir of his career. He felt that his honour had been stained and did his best to seek redress. When that was not forthcoming, he insisted, against his friends’ advice, on publishing a pamphlet outlining his side of the story. Did he really believe the British public was eager to gobble up his dry, factual account of an obscure bureaucratic squabble on an unknown island on the other side of the world? Probably not; but he had to do something – or so he thought. In truth, his name scarcely needed clearing. His closest friends and Arctic cronies had always been on his side. No pamphleteering was required to retain their loyalty. As for the general public, who never read the pamphlet, the man who ate his boots was still an Arctic hero.

For Sir John Franklin, that was not good enough. Something more was needed, some daring public adventure that would remove the stain of Montagu’s perfidy. He would soon reach his sixtieth year; his career was almost at an end. But he could not – would not – rest until he regained what he considered his honour through some great new feat of exploration – or, more likely, some great old feat.

Once again, the North West Passage beckoned.