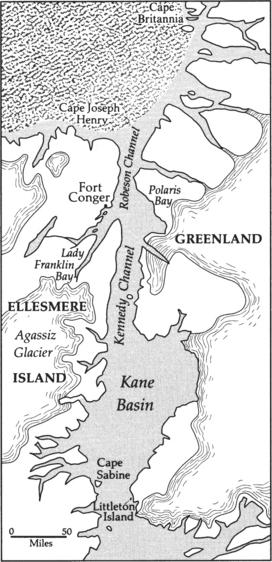

Rescue of the Greely survivors in their collapsed tent (illustration credit 11.1)

As the Nares expedition was setting off for Smith Sound in the summer of 1875, a young Austrian scientist and naval lieutenant, Karl Weyprecht, fresh from his discovery of Franz Josef Land off northern Russia, began a campaign of his own. Simply put, Weyprecht’s scheme was to strip the glamour and romance from polar exploration and concentrate exclusively on scientific matters.

It was, of course, an ingenuous idea. Explorers, almost by definition, are romantics; it is the very glamour of the quest that lures them on, not the laborious collection of geological or botanical data. The mass of scientific evidence collected since Parry’s day was merely a byproduct of the ardent pursuit of the Unknown. Not only the explorers but even the hardest-headed of the scientists who accompanied the polar sorties were seduced by the spell of the Arctic and the need to move deeper and deeper into that mysterious and often magical realm. Weyprecht was right when he argued that the race for new discoveries – the search for the Passage and the Pole – had taken precedence over solid research.

His plan, which he proposed to a meeting of the German Scientific and Medical Association at Graz, was to forget matters of national prestige and personal ambition and to organize a carefully integrated international program of observation and analysis during the polar night of the Arctic and Antarctic that might lead to discoveries that would benefit mankind. This laudable proposal met with some opposition, but Weyprecht persisted over the next four years. He had history on his side, for this was, in a real sense, a golden age of applied scientific development. In those four years, the telephone, the typewriter, the electric light bulb, and the phonograph all came into their own. The world was dazzled by a burst of technical accomplishment – from the player piano to the carpet sweeper, from dryplate photography to the four-cycle gasoline engine. Science was seen to work; it was obvious now that it could improve the quality of life. Who could tell what new wonders might emerge from the laboratories of America or even from the makeshift observatories set up on the naked tundra of a remote Arctic island?

In 1879, Weyprecht’s ideas were adopted by the International Polar Conference in Hamburg. That led, in 1882-83, to the establishment of the first International Polar Year, in which eleven nations were pledged to establish fifteen new observation stations in the Arctic and Antarctic.

The remotest station of all would be at Lady Franklin Bay, where George Nares’s second ship, Discovery, had wintered in 1875-76. This would be the United States’ contribution to the great international undertaking. On those barren shores, twenty-four men and two Eskimos, all under U.S. Army command, would carry out scientific observations for the good of humanity. There was, of course, another, less publicized purpose. In spite of Karl Weyprecht’s high-minded pursuit of science, the expedition’s task was to try to reach the Pole, or, at the very least, to beat the British record and plant the Stars and Stripes on a new Farthest North. Thus the stage was set for the most appalling tragedy since the loss of John Franklin and his men.

At the same time another polar tragedy was in the making. On July 8, 1879, the 420-ton barque-rigged coal burner, Jeannette, steamed out of San Francisco Bay under the command of a thirty-five-year-old naval veteran, Lieutenant George Washington De Long, who had taken part in the search for Charles Hall’s Polaris. De Long was convinced that he could reach the North Pole by way of the Bering Sea. McClure’s and Collinson’s explorations should have convinced him that the permanent pack they had encountered off the Beaufort Sea would make such an excursion dubious. But De Long had been seduced by the theories of the noted German geographer August Petermann, the so-called “sage of Gotha,” an armchair scientist who was convinced that a current of warm water from the Pacific led north through Bering Strait to a tepid basin – another version of the Open Polar Sea theory.

The expedition was under naval discipline but was financed by the flamboyant New York Herald publisher, James Gordon Bennett, who hoped that the impetuous De Long would do for him in the Arctic what an earlier explorer had done for him in Africa: De Long would become another Stanley; his Livingstone would be the Pole itself. As De Long’s wife, Emma, put it, “the polar virus was in his blood and would not let him rest.”

The Jeannette had last been seen by the homebound Pacific whaling fleet east of Wrangel Land – a mysterious realm that some thought stretched like a bridge to the Pole itself. (It was actually an island.) That was in September 1879. Now it was June 1881, and nothing had been heard or seen of the missing ship for twenty-two months. Some doubts, in fact, had been cast on her seaworthiness.

Before it left, the Lady Franklin Bay Expedition, as it was officially named, was given a secondary task – to search for any clues to the Jeannette in the ice-bound waters north of Ellesmere Island. There was an element of unofficial competition here: both the U.S. Navy and the U.S. Army had mounted expeditions to seek the Pole. Now the Army had been ordered to search out and perhaps rescue the missing naval vessel. The bluecoats of the senior service would have been less than human if that had not rankled.

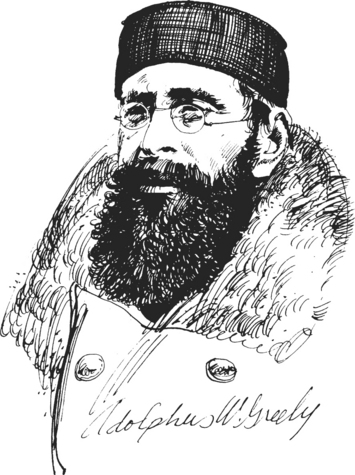

The Army officer selected to take charge of this ambitious undertaking was a studious, straight-backed New England puritan named Adolphus Washington Greely, who, characteristically, preferred to use his initials “A. W.” He was thirty-eight years old, a wiry, six-foot-one-inch veteran of the Civil War, bearded and bespectacled, well read but humourless, and a stickler for military discipline. Indeed, he was something of a martinet, an indication, perhaps, of an inner insecurity that would make itself felt in the ordeal to come. His creed was the work ethic. He did not countenance gambling for money; he allowed no frivolity on Sunday; he permitted no profane language among his men.

He was brave – he had shown that during his Civil War service; but he could also be irritable, and he didn’t like to be crossed. He had a strong sense of his position as a commissioned officer and of the importance of maintaining a gap between himself and his enlisted men. Although he was not imaginative, he was ambitious. He wanted the Arctic posting badly, and he got it through the help of Captain Henry Howgate, a fellow officer in the Signal Corps, who had also been infected by the polar virus. Howgate, in fact, had tried unsuccessfully to mount an Arctic expedition of his own, with Greely’s help. Neither man had ever been to the Arctic – nor had any of the officers and soldiers who would accompany Greely north – but Greely had devoured every book and journal he could find that dealt with the polar regions. He felt he had some useful experience, for he had survived a devastating three-day blizzard in the Sioux country of the American West. Clearly, the Army felt he was the best they could supply to establish a scientific station on Lady Franklin Bay. Of Greely’s twenty-four followers, half were officers or non-commissioned officers, an indication of the importance the Army placed on the expedition.

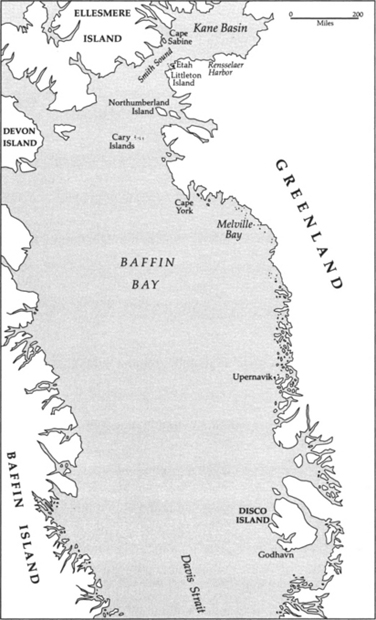

The ship that would take this party north and deposit it on the inhospitable shores of Ellesmere Island was a 467-ton sealer, the Proteus, a rugged steamer built of oak and ironwood. Early in July, 1881, she reached St. John’s, where the native Newfoundlanders, long since accustomed to polar parties shifting back and forth through their capital, showed a marked lack of interest in her departure. She crossed the treacherous Melville Bay in a record thirty-six hours – a remarkable feat – and reached her destination on August 11.

Greely had already written a last letter to his wife, Henrietta, which the Proteus would carry back: “I think of you always and most continually. I wonder what you and the darling babes are doing. I desire continually you and your society, our home and its comforts. I am content at being here only that I hope from and through it the future may be made brighter and happier for you and the children. Will it? We will so hope and trust. There seems so little outside of you and the babes that is of any real and true value to me.…”

Now here he was, as far from civilization as it was possible to get, almost a thousand miles north of the Arctic Circle, six hundred miles south of the Pole, living with two dozen followers in a barren hut named Fort Conger and facing, on that very first night, the same tensions that Hall and Kane had encountered and that the American government had hoped to forestall.

Both of his lieutenants, James B. Lockwood and Frederick Kislingbury, had been in the habit of lying in bed long after breakfast call when the enlisted men were up and about. Greely resented this and gave both men a dressing down. When Lockwood admitted his delinquency and promised to reform, Greely forgave him, although the promised reform took several weeks. But the other lie-abed, Kislingbury, took Greely’s words in bad part, and that Greely couldn’t abide. When Kislingbury continued to sleep in, Greely, nervous about his command, brought matters to a head in an acrimonious encounter that ended when Kislingbury asked to be recalled.

Obviously, there was more to it than that. Kislingbury, a veteran of fifteen years’ Army service, eight on the frontier, had been the first to volunteer. He had lost two wives in three years and was now the single father of four small boys. The trip, he said, was “a Godsend … a wonderful chance to wear out my second terrible sorrow.” Now he was throwing it all away. Obviously he felt he could not get along with his commander.

But Kislingbury had left his decision too late. The Proteus had unloaded her stores and was ready to leave as soon as the ice blocking the harbour cleared. On August 26, noticing that the way to the sea was open, the captain, in ignorance of Kislingbury’s resignation, steamed off, leaving Kislingbury making his way across the ice toward the ship.

It was an unfortunate turn of events. Greely now had a supernumerary on his hands, a man who had resigned his command, who could be given no work of any kind, and who actively despised him. The feeling was mutual, aggravated by the close conditions under which all would suffer. It was one of those foolish standoffs that sometimes make grown men act like small boys. Greely needed Kislingbury. Kislingbury needed to be an active member of the company; all he had to do was swallow his pride and apply for reinstatement. Greely clearly expected this, but it didn’t happen. All Greely had to do was offer reinstatement and Kislingbury would have jumped at it. Many months later, when both men were at the end of their tether, Greely relented. But for most of that long time of troubles, neither would unbend.

There were other problems. At Godhavn, Greenland, the expedition’s remaining four men had been taken aboard – two Eskimo dog drivers, Jens Edward and Frederick Christiansen, and two civilian volunteers, Henry Clay (grandson of the great Kentucky orator) and a surgeon, Dr. Octave Pavy. Pavy was the problem. He and Clay quarrelled so viciously that one would have to go. Greely, who could not spare the doctor, agreed that Clay would return with the Proteus. Clay made the ship that Kislingbury missed.

Pavy was not an easy man to deal with. Mercurial, often moody, ambitious, this high-domed, pipe-smoking scientist felt himself superior to the others – as Dr. Bessels had on the Hall voyage. There was no doubt in his mind that he would make a better leader of the expedition than Greely. Technically, he was now a soldier, but he considered himself above military discipline; and there was little that Greely could do about that. As scientific leader of the expedition and its only doctor, Pavy was immune.

Except for his interest in polar exploration, which was obsessive, Pavy had very little in common with his commander. In fact, it would have been difficult to discover two more disparate characters. The strait-laced Greely didn’t like him, was suspicious of his motives, and referred to him as a “Bohemian,” a word that, in Greely’s puritan lexicon, carried connotations of the devil.

Pavy’s background was both romantic and bizarre. The son of a wealthy French plantation owner and cotton merchant in New Orleans, he had been educated in Paris, where he studied both science and medicine. He had travelled widely in Europe – French was his first language – and considered himself a connoisseur of painting and sculpture. But the virus was in him, too: the Arctic captivated him; the mystery of the Pole magnetized him. In his early twenties he had encountered the French explorer Gustav Lambert and planned with him a polar expedition that was aborted only by the onset of the Franco-Prussian War. Pavy fought with distinction as a captain in the Black Guerrillas. But his Arctic hopes were dashed when Lambert was killed.

Back in the United States, Pavy had fallen under the spell of Charles Francis Hall, with whom he held daily conversations. When Hall headed north on his government-sponsored expedition, Pavy sought to out-do him with a private one. Like De Long, he was convinced that the proper route to the Pole led through the Bering Sea, and so the “Pavy Expedition to the North Pole” was born in San Francisco. In a weird turn of fortune, the chief financial backer was murdered by his valet just before the expedition was to sail in the summer of 1872. Pavy was given the news while attending a fashionable ball. It changed his life.

For the next four years, sunk in despondency, the thwarted explorer became a vagabond, living along the banks of the Missouri River – a ragged, threadbare, and friendless wanderer, working at a series of menial jobs until he was taken up by two Missouri physicians. Suddenly, he was back in society, completing his medical studies, marrying into a well-to-do family, and lecturing at the St. Louis Academy of Science. In 1880 he headed for the Arctic. The following year, at Godhavn, he boarded the Proteus and became part of the Greely expedition.

There is something splendidly ironic about Pavy’s connection with the International Polar Year. The Greely expedition, following Karl Weyprecht’s philosophy, was supposed to be devoted entirely to scientific observation; the romantic idea of a “race to the Pole” had no part in its conception. Yet the scientist placed in charge at Lady Franklin Bay was less interested in meticulous observation than he was in the adventure of polar discovery. Octave Pierre Pavy was determined to get as close to the Pole as possible – and to beat out any possible rival, including the members of his own expedition.

Greely was by no means immune to a similar ambition. At the very least, he wanted to push one party farther north than Markham of the Nares party had gone five years before. That fall he sent out two parties under Lockwood and Pavy to scout the land and set up depots for the spring sledging. He had already picked Lockwood – a tireless worker in spite of his problems at early morning rising – to try to beat the British record. But Pavy was determined to forestall him. That October, while on a sledging trip with Jens, the cheerful Eskimo dog driver, he revealed his plan to young Private William Whisler, his sledgemate. He promised he’d take Whisler with him in the spring to try to reach the highest northern latitude yet attained. He would manage this by having Whisler steal the expedition’s only remaining dogteam. Without dogs, Lockwood wouldn’t be able to travel as far, and Pavy would grab the glory. When Whisler refused, Pavy became abusive and angry. Whisler threatened him with a revolver, and there the matter ended. Whisler kept the plot to himself and didn’t reveal it to Greely until both were on the point of death. Pavy and Whisler had attempted to reach Cape Joseph Henry on Ellesmere’s northern coast but couldn’t reach it. Nor did they find any traces of the missing Jeannette.

For 136 days, from mid-October 1881 to the end of February 1882, the twenty-five men closeted in the small hut they named Fort Conger were without the sun. Marooned on those bleak and treeless shores, hemmed in by sullen, wall-like cliffs that rose as high as a thousand feet, they did their best to pass the time playing Parcheesi and chess, backgammon and cards (but never for money), engaging in theatricals, taking classes in everything from grammar to meteorology, and publishing a newspaper, the Arctic Moon. Greely himself lectured on “the Arctic question,” a euphemism for the North Pole discovery, which, as George Rice, the civilian photographer who had been given sergeant’s rank, remarked, was “a subject especially absorbing to those present.”

The four officers lived precariously, crammed together into a fifteen-by-seventeen-foot space and separated from the enlisted men by an entry alcove and a kitchen. The mordant Pavy, who felt confined “like a white bear in its cage,” had gravitated toward the equally sarcastic Kislingbury; they shared a common distaste for Greely, whose “indomitable vanity” (Pavy’s words) and rigid discipline continued to chafe.

To the restless young James Lockwood, eager to be off on his northern quest, the months seemed to stretch off endlessly. “Surely this is a happy quartet occupying this room!” he wrote sardonically in his journal that fall. “We often sit silent during the whole day and even a meal fails to elicit anything more than a chance remark or two. A charming prospect for four months of darkness penned up as we are.…”

Greely at Fort Conger, 1881-83

Lockwood longed for relief, but there was none. They had arrived in the High Arctic to experience the coldest winter on record. The enlisted men became depressed, growling over the least imagined slight. Pavy noted sourly that “they say and express loudly that they came here only to make a stake. That they have no desire and interest to make discoveries and that if they could return next year, they will do so.”

On December 5, Jens, the Eskimo dog driver – a great favourite – ran away, apparently prepared to die from starvation or suicide. A search party found him, sullen and stubborn, and convinced him that no one had intended to wrong him. Two days later, his companion, Frederick, armed with a large wooden cross, presented himself to the officers, claiming that the men were going to shoot him. He announced that he was going away to die and was restrained only with difficulty. Small wonder that Sergeant David Brainard, when he finally located Charles Hall’s grave at Polaris Bay – an equally desolate prospect – sounded a wan note in his diary. “One scarcely wonders that Hall died,” he wrote. “I think the gloom would drive me to suicide in a week.” That night Brainard kept his spirits up with some of Lockwood’s rum punch.

Late in April 1882, Greely dispatched his two main expeditions to try to better the British record of Farthest North. Pavy would take one party up the coast of Ellesmere Island, following it to Cape Joseph Henry, its northern tip, to try to beat Markham’s record. Lockwood would take a second across Robeson Channel to the Greenland coast and then north in Beaumont’s tracks.

Pavy had the bad luck to encounter open water. He returned empty handed and, if the letters Greely wrote to his wife in the expectation of a relief ship are to be believed, more surly than ever. Greely had already written that the doctor was “an arrant mischief maker.” Now he described him to Henrietta Greely as a “tricky double-faced man, idle, unfit for any Arctic work except doctoring & sledge travel & not first class in the latter.” Pavy and Kislingbury were now spending most of their time together, “united by the common wish and desire to break down the commander but not daring to openly act to that effect.”

Greely’s hope lay in Lockwood, who was facing harsh conditions in his attempts to better the British record. Within a week, four of his men had broken down and been sent back to Fort Conger. Brainard, his second-in-command, described the blowing snow as “like handfuls of gravel thrown in our faces.” On April 29, on the northern coast of Greenland, with Cape Britannia in the distance, Lockwood sent all but two of his men back, three to wait at the Polaris boat camp, the others to return to the ship. Fred, the dog driver, was indispensable, and Brainard, in spite of snowblindness, was still the strongest and most steadfast of the group. This pair would accompany him on the final dash to break the record.

At twenty-four, Sergeant Brainard – blue-eyed, firm-jawed, and handsome – had already seen five years of service with the 2nd Cavalry. He had joined the Army at nineteen on an impulse, having left his home in Norway to visit the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition. Changing trains on the way back to New York, he found he’d lost the money he’d been keeping to buy a ticket home. He was too proud to write for help; instead, he took the free ferry to Governor’s Island and signed up. Wounded in the Indian wars in the West, he’d been ready to return to civilian life when the Arctic beckoned. Here he proved his mettle. Greely called him “my mainstay in many things,” and so, in the dark days that followed, he would prove to be. David Brainard was all soldier. Others in that strangely assorted company might whine, grumble, and plot; not he.

In his own words, he “stumbled about all day like a blind man,” his eyes smarting from the glare as if scoured by red-hot sand. In spite of that, the party made good time. On May 4, at four-thirty in the morning, the bulk of Cape Britannia loomed out of the haze. Beaumont had seen it, but, wracked by scurvy, had never reached it. The two Americans and their Eskimo driver, sucking on lemon-juice lozenges, arrived at its base at seven-thirty that evening and unfurled a small American flag to mark their triumph.

They pressed on for another ten days until their supplies ran out. At latitude 83° 24′ N they built “a magnificent cairn which will endure for ages” and planted another Stars and Stripes on the spot. For the first time in three centuries, it was a non-British expedition that had reached the highest explored latitude on the globe, and Brainard was determined to mark it in a uniquely American way. Everywhere he had travelled, he noted, he had always seen a malt liquor called Plantation Bitters advertised conspicuously. Nothing would do but that he climb the face of a volcanic cliff and carve out the company’s familiar trademark: St 1860 X (“Started trade in 1860 with ten dollars”). That done, it was time to head for home.

They had managed to get one hundred nautical miles farther north than Beaumont but only four miles farther than Markham. Nonetheless, the record stood for thirteen years. They had also charted eighty-five miles of unexplored Greenland coastline. On the return journey they came upon one of Beaumont’s cairns containing a message detailing the onset of scurvy, from which, thanks to an improved diet and the lemon-juice lozenges, they were happily free. But two of the support party had been so badly blinded by the glare that they had to be led back by the hand to Fort Conger. They reached it on June 11.

Lockwood’s victory did not sit well with the jealous Dr. Pavy, who was so persistently rude and hostile to him that Lockwood pleaded with Greely not to send the two out together the following spring. Greely refused. Scientific observations, he said, had to take precedence over personal failings. Greely himself set out that summer to explore the interior of Grinnell Land, as the mid-section of Ellesmere Island was called, seeking if possible to find a route through that fiord-riven domain to the “Western Sea” – in short another North West Passage. In this he was unsuccessful, but he did unlock many of the secrets of Ellesmere’s mountainous interior – a country so rugged that when he and his men returned, their bleeding toes protruded from what was left of their tattered boots.

By August 1882, the party began to look forward to the arrival of the supply ship from the south, bringing new provisions, new personnel, and, far more important, mail and news from home. Days passed; nothing. Yet the harbour was relatively clear of ice, more open than it had been the previous year. Greely could not know that the ship, the Neptune, was two hundred miles to the south, vainly striving to force its way through a frozen barrier that could not be breached.

As hopes began to fade, the company was faced with the dismaying prospect of a second winter cut off from civilization. “The life we are leading now is somewhat similar to a prisoner in the Bastile [sic]” the impatient Lockwood wrote, “no amusements, no recreations, no event to break the monotony.… The others are as moody as I am – Greely sometimes, Kislingbury always, and as to the doctor, to say he is not congenial is to put it in a very mild way indeed.” On the other hand, “the hilarity in the other room is in marked contrast to the gloom in this.”

By late fall, with no hope of relief, the mood grew even darker. Sergeant William Cross, the glowering, black-bearded former machinist who had charge of the expedition’s motor launch, Lady Greely, got drunk on spirit-lamp fuel pilfered from the little vessel and tumbled, senseless, into the icy waters of the harbour. Brainard pulled him out and because, like Pavy, he was indispensable, Greely treated him leniently. When Greely wasn’t present Kislingbury and Pavy engaged in what Lockwood called “the most gloomy prognostications as to the future, and in adverse criticisms on the conduct of the expedition.” Sometimes, Lockwood thought, the life of an exile in Siberia would be preferable. The only reading available consisted of novels and books on the Arctic. Lockwood, in studying these, became convinced, as did others, that Isaac Hayes had exaggerated his own exploits. He could not, for instance, have come anywhere near Cape Lieber as he claimed. To reach that farthest point he would have had to travel ninety-six miles in fourteen hours, a clear impossibility.

The monotonous winter dragged on. Because of the danger from polar bears the men were ordered to stay within five hundred feet of the hut, a restriction that made exercise boring. Brainard noticed the “state of nervousness our idleness has brought on all of us.” The smallest things caused aggravation and annoyance. To combat lassitude Greely had forbidden the men to sleep in their bunks during the day. The Christmas celebration, Brainard noted, was a mockery. No other expedition had spent a second winter this far north; no other had experienced nights longer or darker than these. On New Year’s Eve, there was barely enough spirit left to get up a dance. Fred, the Eskimo driver, was the star of the evening, dancing a hornpipe that at last brought a few chuckles from the downcast assembly.

Lockwood was in a frenzy to be off to reach the 84th parallel and set a new record. He left on March 2, 1883, with a party that again included Brainard and Frederick, his comrades on the previous journey. This time they failed. The polar pack, which had the year before allowed the sledges to make shortcuts across the frozen inlets, was breaking up early. The party barely escaped drowning when the dogs crashed through the thin ice near Repulse Haven on Greenland’s north shore. Lockwood wanted to keep on, but Greely’s orders had been explicit: if the pack started to break up he was to return at once and not endanger human life. Brainard told him he had no choice. They arrived back at Fort Conger on April 11, 1883.

Lockwood was grievously disappointed. “Do I take up my pen to write the humiliating word failed?” he wrote. “I do, and bitter is the dose.…” He was eager to go out again – anything to get away from the morose Pavy and the gloomy Kislingbury – and so proposed a new scheme that, he insisted, would see him exceed his previous record and still be back within forty-four days. Greely quashed it; it wasn’t prudent, he told Lockwood.

Lockwood promptly came up with an alternative plan – to go west along the north shore of Grinnell Land and then north to surpass the English again in new discoveries. This time Greely agreed. The romantic idea of an international race of discovery – the very kind of geographical contest that Karl Weyprecht had deprecated and this expedition was supposed to eschew – now seemed uppermost in everybody’s mind. Lockwood took Brainard and Frederick with him again; there was no more talk of Pavy travelling with him that spring. They set off on April 25, and this time their explorations bore fruit.

While the others continued with the ambitious scientific program the trio charted more of the interior of Grinnell Land. They discovered the vast Agassiz Glacier, which sprawls for eighty-five square miles over the heart of Ellesmere Island. They crossed the divide to the “Western Ocean” – a long fiord that led, not to the open sea, but to a tangle of islands off Ellesmere’s western coast. On their return they came upon an unexpected sight: another of those strange fossil forests that are scattered across the face of the Arctic – trees nine inches thick, turned to stone, that hint at a temperate northern world before the ice ages.

Lockwood, Brainard, and Frederick had achieved for the Greely expedition three new records: a Farthest North, a Farthest East, and a Farthest West – records the British had held for three centuries. They had travelled by foot and dogsled a distance equal to one-eighth of the world’s circumference at the eightieth parallel. Geographical exploration and national sentiment had again taken precedence over scientific observation. That became painfully clear when Greely discovered that Dr. Pavy’s own collections were in a shambles. The doctor was far more interested in scoring geographical firsts than he was in keeping a systematic scientific record. He had deceived Greely, claiming that his specimens were properly preserved and that he’d kept careful notes. He had not. The “collection” was a vast jumble of artifacts, skins, pressed flowers, and rocks. Greely fired Pavy as scientific leader and appointed Lockwood, who had no training, to bring order out of chaos. In the end it didn’t matter. The specimens, which Lockwood arranged, noted, and carefully packed, had to be abandoned.

Pavy’s contract terminated on July 20. He announced he did not intend to renew it but would continue to attend to the men’s medical needs free of charge until the expedition returned to the United States. Greely was outraged. He ordered the doctor to turn over all his official observations and memoranda to be sealed and kept for the Chief Signal Officer, as the original instructions provided. Pavy bluntly refused. He claimed his journal had no scientific value and contained only “personal and intimate thoughts … of an entirely private character.” That wasn’t entirely true, but there were some personal and intimate thoughts – those that criticized Greely and some of the others.

Greely put Pavy under arrest. Pavy blustered. Greely remained firm. He would not confine him, he said – the party needed a doctor – but he was determined to charge him with disobedience to orders and place him before a court-martial when the expedition returned.

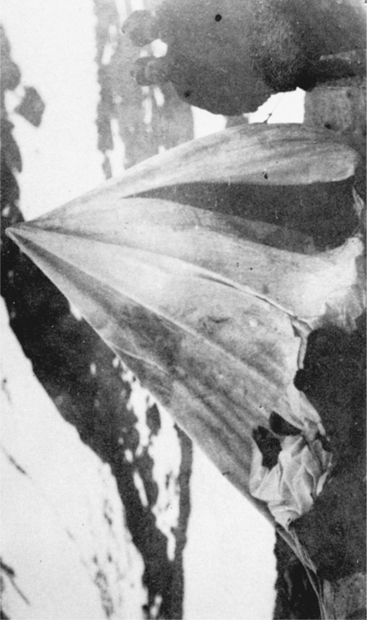

He had a more pressing concern. What if the relief ship should again be blocked by ice? Before sailing, he had worked out a careful plan for that eventuality. If the relief ship didn’t get through in 1882, she was to deposit supplies on the western shores of Kennedy Channel. These he could pick up if he was forced to retreat down the eastern coastline of Grinnell Land. He had laid out similarly detailed instructions for the failure of a second relief expedition in 1883, fully expecting that additional caches would be left at specific points both at Cape Sabine and farther north in the area of Cape Bache. In addition, the relief ship was to leave a depot of provisions at Littleton Island on the Greenland side, directly across the twenty-three-mile channel from Cape Sabine. Here a winter station would be established. Men with telescopes would search the shoreline of Ellesmere daily looking for the Greely party as it made its way south.

Greely had no real worries about supplies. With the depots he himself had established on the way north, he expected to find seven caches along the coastline. His orders were to leave Fort Conger by September 1, 1883, if the relief ship failed to appear. If necessary he could winter near the depot at Cape Sabine – a rock island 245 miles to the south, just off the Ellesmere coast at the head of Smith Sound. The relief party in winter quarters at Littleton Island would be able to cross the channel to help them, or, if the weather was right, his own party could make its way to the island by open boat and steam launch.

Greely didn’t intend to wait until the September deadline. He had long since decided to leave for the south in early August if no ship appeared. He was convinced he would meet it somewhere along the Ellesmere coast, probably only a few miles south of Fort Conger.

Hindsight suggests that it would have been better to stay put. Game was plentiful in the area of Lady Franklin Bay, but conditions were quite different farther south. Adolphus Greely of course had no way of knowing the tragedy that was being forced on him by events over which he had no control. And so, on August 9, 1883, in two open boats and the steam launch, the party set off through the jostling ice pack on the second stage of its long ordeal.

The two attempts that were made to reach the Lady Franklin Bay Expedition in the summers of 1882 and 1883 were characterized by bureaucratic bungling, vague and often contradictory orders, and flawed planning.

The supply ship Neptune set off for the North in the summer of 1882, carrying more than eight tons of provisions for Greely and his party. The man in charge of the expedition – but not of the ship – was Private William Beebe, private secretary to General William Babcock Hazen, the Chief Signal Officer and Greely’s superior. Beebe had asked for a promotion to sergeant “or better still … lieutenant,” but that request was denied. (He was later damned in the press as a man that Hazen “knew to be an habitual drunkard.”)

The Neptune deposited two small caches of 250 rations, one on the Ellesmere coastline, the other at Littleton Island off Greenland. It struggled for forty days to get through the pack at Kane Basin and then returned to St. John’s with a ton of canned meats, an equal amount of fruit, and some six tons of seal meat, all of which might have been left for the retreating Greely party. Poor Beebe could not be blamed; he was following the general’s orders to bring back the rest of the supplies if the ship couldn’t get through. A more experienced officer with a higher rank might have acted on his own. Private Beebe did as he was told.

Henrietta Greely, the explorer’s young wife, did her best to “simulate calmness,” as she told James Lockwood’s mother, after she learned that the Neptune had failed to reach the party. After all, her husband’s expedition was provisioned for three years and, with the fresh game available and with careful rationing, could probably hold out for four. As far as she knew there would be no debilitating sledge journeys toward the Pole; these men were to remain at Fort Conger doing scientific work. All the same, with the help of the senior Lockwood – he was, after all, a general – she was doing some lobbying behind the scenes in Washington for a better-equipped and better-led expedition in 1883.

Mrs. Greely had long since come to terms with her husband’s obsession with the Arctic. It had been an obstacle to their marriage in 1878, when Dolph Greely was trying vainly to help his friend Howgate set up a North Pole expedition. “I could not think of going without you were my wife,” he had written to her. “I should suffer untold agony while gone in thinking of you … I could not endure it! You must say that we will have a few months of happiness and of each other.”

She had been torn, then. “Are not your ambition and pride guiding you to the exclusion of all other thought?” she asked him. She would rather be his wife than the widow of a dead hero, she declared. “I am not Lady Franklin. My spirit may be willing but my flesh is weak.” Fortunately for her, the Howgate expedition came to nothing. They were married in June 1878. She bore him two children, made her peace with his ambitions, and, in the finest tradition of Arctic exploration, presented him when he left with a silk flag she had personally embroidered, to be placed on lands unknown.

Now, in the winter of 1882-83, she began to read the journals of Kane, Hayes, and other Arctic explorers until, like Lady Franklin, she became as knowledgeable about the frozen world as those who had dispatched her husband to examine it.

Her efforts and those of the Lockwood family bore fruit. They had chosen the Proteus as the best possible vessel to reach the expedition. Its skipper, Captain Pike, was a veteran of forty years in the sealing fields. Two years earlier he had taken the Proteus to Lady Franklin Bay. Now, under the same master, the sealer and its crew of Newfoundlanders were the Army’s ideal choice to repeat the voyage. The Navy supplied an escort vessel, the Yantic, to accompany her. The Yantic wasn’t strong enough to invade the main pack, but she could act as a supply ship and, if necessary, an auxiliary rescue vessel.

The Secretary of War, Robert Todd Lincoln, son of the murdered president, wanted to clear up the whole embarrassing mess as quickly as possible. He had always been lukewarm to Arctic exploration. Now he was being harried by the press not only for the failure of the Neptune but also for his inability to bring Greely’s old comrade, the would-be Arctic explorer Captain Henry Howgate, to justice. Shortly after Greely left for the North, Howgate was discovered to have embezzled $200,000 in Army funds, which he squandered on a paramour. Unfortunately, he had managed to escape custody and was now at large with a covey of Pinkerton detectives vainly trying to find him.

Even worse was the sobering news that trickled in from the Jeannette expedition, a tragic failure that had cost the lives of a dozen men, including its commander, George De Long. Early in the fall of 1879, the vessel had been trapped and held in thrall by the ice pack beyond Wrangel Island, an experience that convinced De Long the theory of a warm gateway to the Arctic was “a delusion and a snare.” For the next twenty-two months, the ship remained in the grip of the ice, which bore it slowly north and west along the Siberian coast until it was finally crushed and destroyed. The crew of thirty-three left the foundering vessel in three open boats and set off on a dreadful Odyssey through the ice-choked Eastern Passage, the mainland several hundred miles away. After two months the boats became separated. One was lost in a gale; the other two landed at separate points in the bewildering maze of the Lena Delta in central Siberia. One party managed to find a native village and was eventually rescued. The other, led by De Long, perished on the tundra from starvation and exhaustion.

The subsequent naval inquiry in the winter and spring of 1882-83 (to be followed by a congressional inquiry) had turned up the usual stories of dissension, insubordination, rival cliques, plotted mutiny, and threats of court-martial – “a spirit of turmoil,” one survivor called it – that were familiar to Arctic veterans but served to tarnish the glamour that had once captured the public. Small wonder, then, that Secretary Lincoln, and indeed the president himself, had little stomach for further Arctic adventure. All they wanted to do was get the whole imbroglio over as quickly as possible.

This time, the man in charge of the Greely relief expedition would be no office clerk but a career Army officer. Lieutenant Ernest A. Garlington was a thirty-year-old West Point graduate, “sober, persistent and able,” in General Hazen’s estimation. Hazen was positively ebullient about the success of the expedition. “Everything that the most careful study and close attention could devise has been attended to and will be availed of,” he told the press. And to Henrietta Greely, he declared, “I am confident everything will go right.”

Everything, in fact, went wrong. The Proteus was to be loaded with enough provisions to last forty men fifteen months, but Garlington and his crew were not on hand to supervise loading of these supplies onto the relief ship when she reached St. John’s. Instead, they were shipped out of New York on the Alhambra on June 7 in charge of a young, newly married sergeant named Wall. Garlington and the rest of his men did not leave until four days later on the Yantic. Garlington had urged that they travel with the provisions, but that request was turned down on the grounds that discipline would be easier to maintain aboard a naval vessel.

When the Alhambra reached Halifax, Wall quit, having, it was said, been “injured by an accident”; a more believable suggestion was that he was eager to be back with his bride. Since no one from Garlington’s crew was present when the supplies were unloaded from the Alhambra at St. John’s and stowed aboard the Proteus, nobody knew exactly where anything was. To reach the meteorological instruments, for instance, the stores had to be broken into. The location of the guns and ammunition was never pinpointed, a delinquency that was to have serious consequences.

General Hazen appeared to harbour the belief that Greely was running short of supplies at Fort Conger. His orders to Garlington stressed haste. “Lieutenant Greely’s supplies will be exhausted during the coming fall, and unless the relief ship can reach him he will be forced, with his party, to retreat southward by land before the winter sets in.”

Actually, Greely had gone north with enough provisions to last three years and enough coffee, beans, sugar, and salt to last four and a half years. In addition he had, at the outset, three months’ supply of fresh muskox meat, which could certainly be added to by the hunters in his party. The expedition could easily have remained at Fort Conger for another year in relative comfort and reasonably good health if Greely had not been ordered specifically to get out by September 1; and Greely was the kind of man who was a stickler for orders.

“… no effort must be spared to push the vessel through to Lady Franklin Bay,” was Hazen’s written order to Garlington. He took this to mean that he shouldn’t stop for anything – not for the slower Yantic, not to unload supplies at Littleton Island, not to pause on the way north to unload more supplies, not even to replenish existing caches on the coast of Ellesmere Island.

There was ambiguity here. For one thing, Garlington was told that the Proteus and the Yantic must stick together as far as Littleton Island, where the Yantic was to await his return – that would force him to wait for the slower vessel. And, though he wasn’t told to stop on the way – the orders suggested the opposite – if he did stop, then he was to examine the depots for damage and, if necessary, replenish them. But the emphasis was on haste. If he couldn’t get through, the orders read, he was to return to Littleton Island, unload his supplies, and search the opposite coastline for signs of Greely’s party.

To add to the confusion, Garlington found included in the envelope that contained his orders a second memorandum that seemed to contradict Hazen’s instructions. This one told him he should unload supplies at Littleton Island en route north and also at the various coastal depots. If the Proteus foundered, the Yantic was to bring the survivors back to Littleton Island. But the Yantic was given more leeway to go her own way if the ice conditions became too dangerous. This sensible memorandum, the result of some equally sensible afterthought – none of it officially approved – had been tacked onto Garlington’s instructions as the result of a clerical error. Garlington questioned it: was it part of the official order? he asked. He was told it was not. That helped save Garlington’s skin in the inquiry that followed.

He did not wait for the Yantic. He left St. John’s on June 29 and pushed directly on to Godhavn on Disco Island off the Greenland coast. The Yantic limped along far in the wake of Proteus – as well adapted for the ice, in the words of one observer, “as a Brooklyn ferry boat” – and then, with her boilers giving out, stopped at Upernavik for a week of repairs.

Garlington, in the Proteus, blocked by the ice pack in Kane Basin, crossed Smith Sound and entered Payer Harbour off Cape Sabine on July 22. Here were two caches, one left by Beebe near the point of the cape the previous year and, on a small island about half a mile from the Proteus’s anchorage, another left by the Nares expedition in 1875. The Beebe cache was found and repaired, but in the four and a half hours that the Proteus stayed at Cape Sabine, no extra provisions were landed, even though these were easily available, having been stowed on board at Godhavn in separate packages especially for this purpose. Garlington’s almost frantic insistence on getting under way frustrated any chance of leaving a substantial cache of food and fuel for the Greely party, which would, within a fortnight, begin its long struggle with the ice down the Ellesmere coastline.

From the shore, the impetuous Garlington thought he saw an open lane of water leading north. He hurried aboard the ship and ordered Captain Pike to get moving. Pike demurred. It was too early in the season, he insisted: what Garlington had seen was no more than the ice shifting with the tide. Garlington was stubborn. Unless the Proteus moved, he insisted, “he should not consider himself as performing his duty to the people at Lady Franklin Bay or the United States Government.” And so a veteran of forty years of Arctic service was overruled by a thirty-year-old landlubber. The Proteus weighed anchor and headed out of the harbour. Fifteen minutes later she entered the loose pack.

She was a sturdy ship, built for the ice, but a decade in the sealing grounds had taken its toll. Her boilers were defective, two of her lifeboats unseaworthy, her rigging old, and her compass untrustworthy. The captain’s twenty-one-year-old son was first mate; it was his first time in the Arctic. The second mate was the captain’s cousin. The chief engineer had just been promoted to that post when the ship sailed. But even a new ship with an experienced crew could not have survived the beating the Proteus took the following afternoon.

She had tried to bull her way through a barrier of pack ice toward an open lane without success. Heavy floes, some ten feet thick, were pouring south through the narrow passage of Smith Sound. In the nip that followed at three o’clock, the sealer was in the worst possible position, headed east-west, so that the ice caught her amidships. Gripped in a hammer-lock between the pressure of the advancing ice and the unyielding barrier of the shore pack, she had no chance. Her starboard rail was crushed to matchwood at 4:30 p.m.

By this time Garlington and some of his men were desperately trying to untangle the jumble of stores in her hold. Another party at the forepeak was trying to save the parcels of prepared rations taken on in Greenland. These they hurled overboard onto the encroaching floes. A third of them tumbled into the sea and were lost.

Suddenly, the ship’s sides burst open as a flood of ice and seawater poured into the bunkers and the hold. The ship stayed afloat, caught and held by the pressure of the ice against her, until 7:30, when the tide turned and she began to sink. By then the scene on the floes was chaotic.

Everything had to be abandoned, including the sledges and the dogs that were to have been used to succour the Greely party. There had been no boat drill; it was every man for himself. The Newfoundland sealers were interested only in saving themselves and their kits. With the ship foundering, their contracts came to an end, and they had no further responsibility to any but themselves. Now they began to plunder the relief expedition’s supplies, rifling open boxes on the ice for clothing and food. There was nothing Garlington could do, for his fourteen soldiers were weaponless. All the guns and ammunition had been stowed heiter skelter in the hold in St. John’s.

Pike could not control his own crew. “You’ve got a lot of men,” he told Garlington ruefully. “But I’ve got a lot of dirty dogs who are too mean to live.” All Garlington could do was to try to prevent a confrontation by keeping his group at a distance from the “pirates and scoundrels” on the ice.

A worse concern faced him. He realized that Greely would arrive at Cape Sabine to find that the promised provisions had not been placed in the cache. With Pike’s help he persuaded four seamen to go with some of his men in a whaleboat and deposit five hundred individual rations on the nearest point of land, about three miles west of the Cape. These would last Greely’s party of twenty-five no more than three weeks.

What was he to do? The previous spring, the young cavalry officer had been out in the Dakotas. Now here he was, a man with no experience at sea, caught in the centre of the ice-choked channel, responsible not only for the men under his immediate command but also for the beleaguered party threading its way down the Ellesmere coast.

He had several choices. He could stay at Cape Sabine and wait for Greely, meanwhile eating up the supplies. He could head north, looking for Greely, a foolhardy course that he immediately dismissed. Or he could seek out the Yantic, which had plenty of provisions, leave two or three men with the Yantic’s supplies at Littleton Island to maintain a lookout for the lost party, and hustle back to St. John’s with the others to arrange for a new ship and more provisions.

He opted for the last course, but with apprehension. Although his orders were to rendezvous with the Yantic at Littleton Island, Garlington couldn’t believe that the little ship could make it across Melville Bay, that notoriously dangerous stretch of water that had once cost Leopold M’Clintock a year’s delay. It would make more sense, Garlington thought, to go in search of the Yantic. Thus was set in motion a series of mischances that might be called a comedy of errors had the results not been so tragic.

The shipwrecked party crossed Smith Sound – the Proteus’s crew in three of the ship’s lifeboats, the soldiers in two whaleboats – and reached Littleton Island on the morning of July 26. The Yantic had not yet arrived, and Garlington didn’t believe it would. With only his own rations saved from the Proteus, he could leave nothing for Greely but a message. That done, he hurried south seeking his consort.

Contrary to Garlington’s supposition, the Yantic had crossed the unpredictable Melville Bay without difficulty and was steaming steadily north. A series of rendezvous points had been arranged along the Greenland coast. One of these was the Cary Islands, some twenty miles west of the mainland. Garlington, who knew nothing of navigation, decided to by-pass this meeting place because he felt the approaches were too hazardous to make a safe landing. In doing so he overruled his more experienced second-in-command, Lieutenant J.C. Colwell. Thus he missed the Yantic, which that very day was putting in to the same rendezvous point. Not finding any message, her commander continued to steam north, passing Garlington’s party in the fog. That mischance finally doomed the Greely party to a winter of starvation.

The near-misses continued. The Yantic reached Littleton Island where its commander, Frank Wildes, learned that Garlington had left for the south. He steamed after him, neglecting to leave any supplies or message for Greely. When he landed at the Cary Islands he found no trace of Garlington and so went back north again, still seeking his elusive quarry. At one point, the Yantic was within four hours’ steaming distance of Garlington’s five boats, but the two parties failed to meet.

At Northumberland Island, Wildes found the remains of Garlington’s camp – the first clue as to his current whereabouts. He decided to turn south again to Cape York, another of the rendezvous points, but as his fuel was low and the situation looked treacherous, when he reached Cape York he decided not to land. The date was August 10; by a maddening coincidence, Garlington’s party had just arrived at that meeting place. But even as they beached their boats and set up camp, the Yantic was heading south toward Upernavik. Wildes reached it on August 12, hoping that Garlington would soon turn up.

Garlington, however, with his shipwrecked crew of sailors and soldiers, was still at Cape York. On August 16, he decided to send the experienced Colwell and a few men in one of the whaleboats to attempt a dash south across the treacherous waters of Melville Bay. He and the others, in the remaining four boats, would creep around the shoreline.

In a remarkable feat of navigation, Colwell reached Upernavik on August 23, only to find that the Yantic, having waited for ten days, had departed. Pausing only long enough to snatch some food and a few hours’ sleep, Colwell borrowed an open launch from the governor and, with his exhausted men straining at the oars, headed south for Godhavn, the Yantic’s next port of call. He reached it and found the Yantic on August 31, having spent fifteen days in an open boat and covered close to nine hundred miles of some of the most treacherous water in the Arctic. Wildes took him and his men aboard the Yantic and returned to Upernavik, where Garlington’s company and the crew of the Proteus were waiting. Thus, after more than a month of cat-and-mouse chase, the two search parties were reunited.

Area of the Greely relief attempts, 1882-84

The survivors of the wrecked ship had come through without the loss of a man; but the relief mission that had brought them to the Kane Basin was a disaster. As General Hazen wrote to Henrietta Greely, it was too late in the season to mount another rescue attempt, but “no effort will be spared to set on foot another expedition at the earliest moment possible.” Somehow Greely and his men would have to try to survive the winter on their own resources. “I hope,” the general told Henrietta, “you will not be needlessly alarmed.”

On August 9, 1883, just as Garlington and his shipwrecked crew were vainly attempting a rendezvous at Cape York, Adolphus Greely and his men left the barren shores of Lady Franklin Bay and started on their long trek south. They left their dogs behind but did not kill them; they would be needed if the party were forced to return. They also left a winter’s supply of food, albeit a meagre one. Each man was allowed to take no more than eight pounds of clothing and equipment, the officers sixteen. But Greely took more.

In addition to his scientific data, he insisted on bringing his dress uniform, sword, scabbard, and epaulettes, “an emblem of authority,” as he told Lockwood. It was a significant remark, for had Greely been in firm command he would have needed no symbols. But in his attempts to hide his own uncertainties and irresolution he became a different man – imperious, irritable, unbalanced. On the second day out, he attacked the faithful Brainard with an undeserved tirade that astonished the stolid sergeant, who did not believe his commander capable of such profanity.

Like Garlington, Greely, the cavalryman and signal officer, had no idea of how to operate a boat in the ice, nor did any of his men. Only two had any sea training – Private Roderick Schneider, who had once been a seaman, and Sergeant Rice, the photographer, who had been raised on Cape Breton Island. Rice quickly became the hero of the journey. When the yacht, Lady Greely, steamed off into the ice-choked channel, towing three open boats, Rice, perched on the foredeck of the jolly boat Valorous, developed an uncanny ability to spot lanes of open water. For his pains he suffered a series of duckings, which he took with good humour.

Even the gloomy Kislingbury thought the world of Rice, reserving his harshest condemnation for Greely. “Lt. G. controlling things,” he wrote in his diary on August 13. “Poor man he knows nothing about the business, has not sense enough to put a good man like Rice as ice navigator … Lockwood could run things better than he does. We lose more distance, time and coal by his nonsense.”

Kislingbury’s comments might be taken as biased, but there were similar remarks in the diaries of others on that long journey. In order to establish authority, Greely tried to run things himself, refusing to listen to the counsel of others. Even Sergeant Joseph Elison, a more dispassionate observer, was vitriolic, referring to his commander as a “lunatic,” a “miserable fool,” “a fraud [and] a humbug.”

Greely’s temper did not improve when he discovered that Cross, the engineer aboard the yacht, was again getting blind drunk on fuel alcohol filched from the engine room. Greely’s hands were tied: Cross, like Pavy, was essential to the expedition. Then, on August 15, he could stand it no longer; Cross was drunk again and insubordinate to the commander, whom he considered “a shirt tail navigator.” In the bitter altercation that followed, Greely drew his pistol. “Shut up!” he shouted, “or else I put a bullet through you.” At that Cross replied, “Go ahead!” Greely didn’t shoot, but he suspended Cross and replaced him with Julius Frederick.

That same day an extraordinary incident took place that was not revealed until many years later. Everyone in the party was concerned because Greely was insisting on abandoning the launch, hoisting the boats onto an ice floe, and trying to drift nearly three hundred miles south to Littleton Island – an act that Brainard, for one, considered “little short of madness.” On the day of the Cross incident, Pavy, Kislingbury, and Rice came to Brainard with a proposition. Pavy volunteered to examine Greely and pronounce him insane. It would not be difficult, he explained, because the commander’s frequent outbursts without provocation established a prima facie case of dementia.

Pavy said he was prepared to establish the legitimacy of his diagnosis before any later court of inquiry. Once Greely was shown to be incapable of maintaining leadership, he would be deposed and Kislingbury would assume control of the expedition. The party would at once turn about and go back to Fort Conger, spend the winter there, and then sledge south in the spring. If Lockwood refused to acknowledge Kislingbury’s authority, he was to be placed under arrest. But the plotters had to have Brainard on their side. The men respected the senior sergeant and would follow his lead. Without him the plan was doomed.

Brainard was, by this time, almost certain that disaster was inevitable. He, too, thought the party’s best chance was to return to Fort Conger. But Brainard was all Army, and this was mutiny. He was having no part of it. In fact, he said, he would resist any such attempt with his life. Nonetheless, he did not tell Greely, for he knew his obstinate nature and was convinced the commander would immediately put into practice the very plan they were resisting – to drift helplessly south with the polar pack. Brainard disclosed the plot only in 1890 and in doing so made it clear that he was not in any way condemning the plotters, who, he felt, were “impelled by a spirit of devotion to the expedition.” Indeed, he wrote that had the plan been consummated, “it is not at all improbable that every man would have escaped with his life.”

But the plan was abandoned. By August 22, the party had reached the halfway point between Fort Conger and Littleton Island. Now there was no turning back. By August 26, when they arrived at a depot that Nares had left at Cape Hawks, they had only sixty days of provisions left, augmented by 250 pounds of mouldy bread and 165 pounds of potatoes left by the English.

Greely could not understand why there was no sign of the relief vessel. More and more he despaired of reaching Littleton Island. If Cross and Kislingbury are to be believed, he had become benumbed, spending more and more time in his sleeping bag. The flotilla, now trapped in the ice, was drifting helplessly with the pack – a perilous position in which the boats could be crushed or destroyed at any moment. When he overheard Kislingbury discussing this with the men and publicly chafing at the inactivity of his superior, Greely upbraided him for undermining his authority. But on September 9 he did call a council of his officers and senior sergeants and turned the navigation over to Rice.

Their progress had been maddeningly slow. Beset in the ice for fifteen days, they had moved only twenty-two miles. The council decided to abandon the yacht and the jolly boat and haul the other boats and supplies across the ice to the Ellesmere shore, eleven miles to the west. Remarkably, the men unanimously agreed not to jettison the hundred-pound pendulum whose observations, taken at Fort Conger, would have no value unless they could be subsequently repeated with the same instrument. Off the party went – twenty-five men hauling sixty-five hundred pounds across the broken surface of the frozen sea. It was more than they could handle. Two days later the whaleboat also was abandoned.

To move everything one mile the men had to haul for five, shuttling the supplies forward bit by bit. The situation grew more dangerous. Even Brainard was shaken by the roar of the grinding pack to the east, “so terrible that even the bravest cannot appear unconcerned.” The floe they were crossing was not connected to land but drifted helplessly about in the basin. When the wind suddenly shifted, the weary men realized they were being blown back north. By the afternoon of September 15, they had lost fifteen miles and were down to forty days’ rations, together with whatever seal meat the two Eskimo hunters could shoot for them.

In order to prevent a further decline in morale, Greely forbade his meteorologist, young Sergeant Edward Israel, to disclose to the others any observations of latitude. Pavy, meanwhile, was bitterly denouncing his commander, claiming that had his advice been taken the party would have remained safely at Fort Conger. A nasty row ensued, but since the doctor was irreplaceable Greely again could take no action.

The wind changed. The floe spun about and began to drift south again. On September 19, land was spotted no more than three miles away. But where was the relief ship? There was no sign of human movement on the Ellesmere shore.

Again the wind shifted. The floe was driven back into the Kane Basin until they were farther north and east of land than before – a good twenty miles. Brainard was heartsick. “Misfortune and calamity, hand in hand, have clung to us along the entire line of this retreat.… To cross the floes over this distance seems a hopeless undertaking when we can average only about a mile and a quarter per day. And now we have been shown what child’s play the wind can make of our struggles. How can we put our heart and strength into hauling the sledges!” That night the wind abated and Greely called a council, urging that an attempt be made to cross to the Greenland shore by abandoning everything except twenty days’ provisions, records, boat, and sledge. To Brainard that was madness.

The floe had become their prison. As long as it whirled about precariously in the moving pack – the ice grinding, crumbling, and piling up about the edges – there was no opportunity to reach land. The pressure on it increased until on September 25 the floe broke apart and the corner on which the party was camped fell away, leaving them marooned on a tiny chunk, the plaything of the winds, tides, and current. That afternoon the wind shifted again. To their dismay, they found that after thirty-two days adrift, they had passed Cape Sabine, where the food caches were supposedly waiting for them, and also the first point on the Ellesmere coast where the relief ship would have stopped.

Following another wild night the floe broke again, leaving them scarcely room enough to stand beside the boats. They were moving farther and farther south of their original destination at alarming speed in a violent ocean that seethed and foamed and could swamp them at any moment. “I see nothing but starvation and death,” Lieutenant Lockwood wrote in his journal.

Two days later the floe slammed against a grounded iceberg, “an act of Providence,” in Brainard’s grateful words, that saved them from being driven into Baffin Bay. Now two lanes of water opened up through which they ferried the sledges and provisions to the Ellesmere shore, four miles away. By this time a third of the party was ill and Cross, the engineer, so hopelessly drunk on alcohol that he couldn’t work the drag ropes on the sledges. But at least, after more than six weeks of exposure, hardship, and terror, they were on solid ground.

They realized they could not possibly cross the strait to Littleton Island. They would have to winter at this spot. The indefatigable Rice volunteered to trek north to Cape Sabine to find the cache. He and Jens, the Eskimo hunter, set off on October 1 with four days’ rations while the others built three hovels on the barren, snow-covered rocks at the base of a conical hill, using the debris from some old Eskimo huts and the oars from the two boats.

Greely estimated the party had enough food to last thirty-five days; in a pinch, that could be stretched to fifty. He showed that he intended to maintain discipline when he broke Sergeant Maurice Connell to private for complaining about his leadership and reprimanded the normally mild Edward Israel for flaring up at Brainard. Israel’s outburst suggests the strained nerves among the company. At twenty-one, the meteorologist was the youngest member of the expedition and the only Jew, a great favourite with everyone – cheerful, good humoured, innocent. He had accused Brainard of grabbing the best material for his hut but quickly regretted that outburst, apologizing profusely to Brainard, charging that others in the party had goaded him into it.

By the time Rice and Jens returned from Cape Sabine on October 9, Greely and his men were worn ragged from digging the heavy stones out of the ice with their bare hands. Greely’s own hands were torn and bleeding, his joints stiff and sore, his clothing tattered, his footgear full of holes, and his back so lame he could not stand erect. “The work,” he wrote, “has taxed to the utmost limit my physical powers, already worn by mental anxiety and responsibility.”

Rice brought terrible news. He had found Garlington’s note reporting the loss of the Proteus but discovered that the three caches in the area – Nares’s, Beebe’s, and Garlington’s – contained only enough rations to last for forty or fifty days.

Garlington’s note had suggested that the Yantic would leave more rations at Littleton Island, just twenty-three miles across the strait from these caches. At this, some of the party, Greely included, cheered up. Surely a rescue party in sledges could make its way there from Cape Sabine once the sea froze! Hadn’t Garlington written that “everything within the power of man” would be done to rescue them? Even Lockwood brightened at the prospect. “We all feel now in excellent spirits by the news,” he wrote.

Greely decided to move north to Cape Sabine at once. Garlington’s note, he thought, made their fate “seem somewhat brighter.” Privately, however, he expected to see to “privation, partial starvation, and possible death for a few of the weakest.” Brainard was even gloomier. Rice’s news, he noted, had brought them “face to face with our situation as it really is. It could hardly be much worse.”

Here they were, six hundred miles north of the Arctic Circle, on a rocky, windswept islet off Ellesmere – a spot rarely visited by ships, a land that had scarcely been mapped – subjected to the intense cold and deathly blizzards of the High Arctic, without shelter or fuel and with very little food. With the long Arctic night about to close in, the only glimmer of light was the hope that men were waiting across the strait to rescue and feed them. It was this belief, and this alone, that sustained them. Had they known they had been abandoned, Greely said later, he would have attempted to cross the ice-choked channel to Littleton Island, a foolhardy act that would certainly have doomed them all.

The move to Cape Sabine began on October 12, 1883, and for the next several weeks Greely and his men shuffled back and forth, hauling supplies to the new camp. The weather was dreadful; October 15 was, in Brainard’s words, “the worst night of our lives.” That same day Greely examined the cache left by Garlington and discovered to his bitter disappointment that it held much less than he had anticipated. Instead of five hundred rations of meat, for instance, there were only one hundred. Meanwhile, Rice, who had been sent to examine the Nares cache, returned to report that it contained only 144 pounds of preserved meat.

Starvation faced them, but the party was in more immediate danger of freezing to death. In spite of the cold they laboured to build a hut with stone walls and a roof made of the whaleboat supported by spars made from oars. It was soon buried in snow and so cramped, being but three feet high, that even in a sitting position the taller men found their heads scraping the ceiling. They named it Camp Clay, after their erstwhile shipmate who had left the expedition because of the quarrel with Pavy.

Clay’s name turned up in some scraps of old newspapers, used for wrapping lemons, that were found in the Proteus cache. In the dim light of an Eskimo lamp, the marooned company devoured the few fragments of news from the outside world. The president, James Garfield, had been shot and replaced by Chester Arthur. And an article by Clay, written the previous May, condemned as inadequate a government plan for relief. Clay had urged that two ships be sent north; otherwise, he predicted disaster for the Greely party if it was forced to exist entirely on the provisions left by Beebe at Cape Sabine.

“The cache of 240 rations,” Clay had written, “if it can be found, will prolong their misery for a few days. When that is exhausted they will be past all earthly succor. Like poor De Long, they will then lie down on the cold ground, under the quiet stars.”

Obviously Clay’s letter had had some effect. But it was also clear that the Jeannette expedition, for which Greely had been ordered to search, had ended in tragedy. Now at last he learned that De Long had perished. It was not a cheerful piece of news.

By the end of October everybody was ravenous. When a hundred pounds of dog biscuits were opened, Greely was dismayed to discover that all were mouldy and half had been reduced to a filthy green slime. At the doctor’s urging, these were thrown away as inedible. Later, he discovered that some of his people had searched for them and gobbled them up. Lockwood was one who found himself “scratching like a dog in the place where moldy dog biscuit [sic] were emptied.” He found a few crumbs and devoured them, mould and all.

The party was already subsisting on reduced rations. Now Greely realized he must reduce rations again if they were to survive the winter. Over Dr. Pavy’s objections he cut the total daily quantities to a lean fourteen ounces per man. That, he figured, would make supplies last until March 1, when they could cross the strait with the few ounces of pemmican, bread, and tea left.

“Whether we can live on such a driblet of food remains to be seen,” Lockwood wrote. “We are now constantly hungry and the constant thought and talk run on food, dishes of all kinds, and what we have eaten, and what we hope to eat when we reach civilization. I have a constant longing for food. Anything to fill me up. God! what a life. A few crumbs of hard bread taste delicious.”

In spite of the bad weather and the darkness, Greely knew he would have to send a party to Cape Isabella to bring back the 144 pounds of preserved meat from the Nares cache. He chose Rice to lead a party of four: Private Julius Frederick, Sergeant Joseph Elison, and David Linn, the latter newly promoted to sergeant to fill the demoted Connell’s position. The party, having been fed extra rations for several days, left on November 2. They took with them additional clothing borrowed from other members of the party.

A week passed with no word. Then at two o’clock on the morning of November 10, Rice stumbled into the hut, broken, exhausted, unable to speak. At last he managed to blurt out a single sentence: “Elison is dying at Ross Bay.”

As Greely made hasty plans for a rescue attempt, Rice recovered enough to give a few details of the party’s ordeal. In the third day, Elison’s thirst was so great that in spite of all warnings he was reduced to eating snow. In doing so he froze both hands and his nose. Worse, his body heat was drained off, as the snow he had devoured melted. By the time the party reached the cache on November 7, he was in a bad way. By the morning of the ninth, during the return trip, with both his hands and his feet frozen, he had to be carried on Frederick’s back. At that point the party was forced to abandon its precious supply of meat.

The nights were a horror. The four-man sleeping bag was frozen stiff because Elison, in dreadful pain, had become incontinent, and his urine froze. In order to thaw Elison’s limbs, Rice cut up Nares’s abandoned ice boat for fuel. The results, for Elison, were excruciating. In spite of that, his feet were so solidly frozen that by the time the group reached Ross Bay, he could no longer stand. Rice grabbed a chunk of frozen beef and set off at once for the main camp, sixteen miles away. He had already walked nine miles that day; by the time he reached the hut he had been on the trail without rest and scarcely any food for sixteen hours.

At 4:30 that morning, Brainard and Fred, the Eskimo hunter, set off as an advance party. A six-man sledge, under Lockwood, followed behind. Brainard reached the Ross Bay camp at noon to find Elison and his two comrades frozen into their sleeping bag. Brainard no longer had the strength to free them. All he could do was force some brandy down their throats. Elison uttered a strangled cry: “Please kill me, will you?” Linn was not much better; Elison’s nightly screams had unhinged his mind, and it was with difficulty that Frederick had prevented Linn from leaving the sleeping bag to encounter certain death.

Brainard immediately turned back into the howling gale to find Lockwood and hurry his party along. When he reached it, he took his place in the drag ropes, and the group reached the sufferers at 5:30 that afternoon. Exposed to the storm, the three men were still frozen into their sleeping bag. The bag was chopped apart and Elison, delirious from pain, was wrapped in a dogskin coverlet and placed on the sledge. The party then set off for Camp Clay, a sixteen-mile trek that Greely was to call “the most remarkable in the annals of Arctic sledging.” Seventeen hours later they reached their destination.

Elison’s condition was pitiful. His feet were shrunken, black, and lifeless, his ankle bones protruding through the emaciated flesh. Private Henry Biederbeck, the medical orderly, who spoon fed him, changed his bandages, and helped with his bodily functions, did not leave his side for sixteen waking hours.

Meanwhile, there were thefts. Somebody had broken into the commissary and stolen hard bread. Schneider was suspected, especially when it was found that a milk tin had been broken into with a knife that was traced to him. Schneider denied it; he had lent the knife to Private Charles B. Henry. Nobody then knew that Charles B. Henry was actually Charles Henry Buck, a convicted forger and thief who had once killed a Chinese in a barroom brawl in Deadwood and had served a prison term for the crime. He had been dishonourably discharged from the cavalry but re-enlisted under an assumed name. Greely had his suspicions about Henry, whom he had caught in several lies. But at this point the evidence against him was inconclusive.

On land, Greely was a better commander than he had been at sea. With nine of his men under Pavy’s care, suffering from a variety of ailments – rupture, frostbite, rheumatism, infections, and incipient scurvy – he organized a series of two-hour morale-building lectures on the geography of the United States, covering one state at a time. Meanwhile, the two Eskimo hunters with Sergeant Francis Long set out to hunt for meat. They brought in an occasional fox or seal, but game was not as plentiful as Greely had supposed. By mid-November, he was again forced to reduce the daily ration to four ounces of meat and six of bread. The ravenous men grew more irritable, each eyeing and mentally weighing in his mind the rations doled out to the others. When the scanty meals were cooked, the entire hut was filled with the dense, choking smoke from the damp wood. Half suffocated, the men crawled into their sleeping bags. But the cooks could not protect themselves, suffering “such misery and discomfort,” in Brainard’s description, “as can scarcely be appreciated by others.”

“We are all more or less unreasonable, and I can only wonder that we are not all insane,” Brainard wrote. “All, including myself, are sullen, and at times very surly. If we are not mad, it should be a matter of surprise.”

To these burdens, another was added. One night in early December, Greely realized that Dr. Pavy was stealing from Elison’s bread can. What could he do? A confrontation would provoke a bitter fight. The doctor was the one indispensable man in camp. Greely confided in Lockwood and Brainard but took no further action.