LIGHT

THE IMPORTANCE OF LIGHT: THE IMPORTANCE OF EXPOSURE

“What should my exposure be?” is, as I’ve already said, a question I frequently hear from my students. Again as I stated earlier, my frequent reply—although it may at first appear flippant—is simply, “Your exposure should be correct—creatively correct, that is!” As I’ve discussed in countless workshops and online photo courses, achieving a creatively correct exposure is vital to a photographer’s ability to be consistent. It’s always the first priority of every successful photographer to determine what kind of exposure opportunity he or she is facing: one that requires great depth of field or shallow depth of field or one that requires freezing the action, implying motion, or panning. Once this has been determined, the real question isn’t “What should my exposure be?” but “From where do I take my meter reading?”

However, before I answer that question, let’s take a look at the foundation on which every exposure is built: light. Over the years, well-meaning photographers have stressed the importance of light or have even been so bold as to say that “light is everything.” This kind of teaching—“See the light and shoot the light!”—has led many aspiring students astray.

Am I anti-light? Of course not! I couldn’t agree more that the right light can bring importance and drama to a composition. But more often than not, the stress is on the light instead of on the (creatively correct) exposure. Whether you’ve chosen to tell a story, to isolate, to freeze action, to pan, or to imply motion in your image, the light will be there regardless. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve met students who think an exposure for light is somehow different from an exposure for a storytelling image or for a panning image, and so on. But what is so different? What has changed all of a sudden?

Am I to believe that a completely different set of apertures and shutter speeds exists only for the light? Of course not! A correct exposure is still a combination of aperture, shutter speed, and ISO. And a creatively correct exposure is still a combination of the right aperture, the right shutter speed, and the right ISO—with or without the light. As far as I’m concerned, the light is the best possible frosting you can put on the cake, but it has never been—and never will be—the cake.

Although the light is important in any image, it was the exposure that was the integral part of making this shot. Any exposure is the correct combination of aperture and shutter speed in conjunction with the ISO, but a creative exposure needs to be the most creative combination regardless of how compelling the light may be!

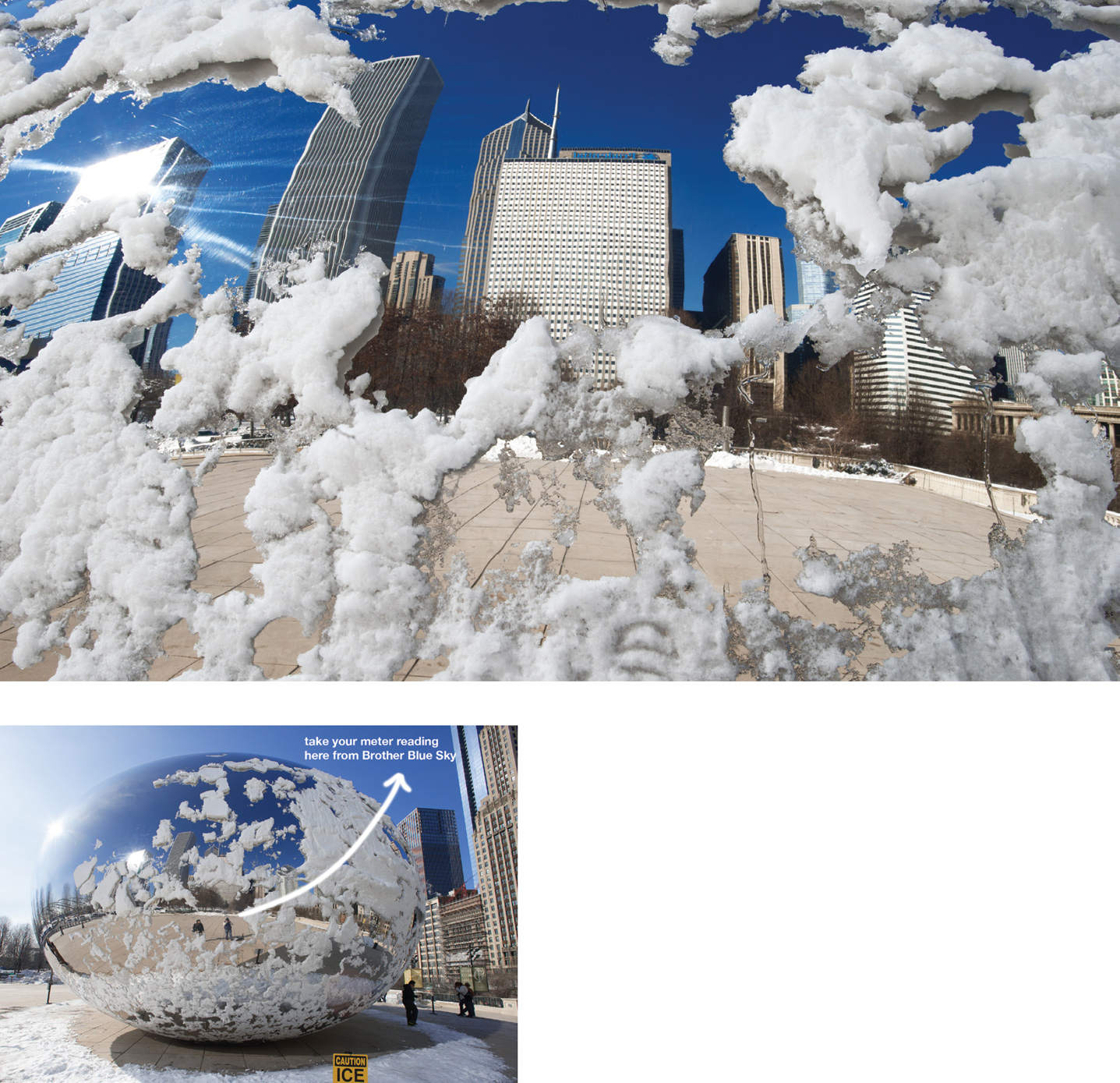

Getting a true storytelling exposure that rendered everything in sharp focus was the key to this shot. From the foreground water to the distant sky and low-hanging clouds, sharpness was the key. When I use my 70–300mm lens for a shot like this, it is almost automatic that I call upon the smaller apertures such as f/22 and f/32. As far as the actual meter, experience has taught me that bright white can fool the meter, so before tripping the shutter release here, I purposely set an exposure to +1 to compensate for the meter’s tendency to underexpose a scene when presented with bright whites.

Nikon D800E, Nikkor 70–300mm at 300mm, f/32 for 1/30 sec., ISO 100, 1 stop overexposed, tripod

THE BEST LIGHT

Where do you find the best light for your subjects? Experienced photographers have learned that the best light often occurs at those times of day when you would rather be sleeping (early morning) or sitting down with family or friends for dinner (late afternoon/early evening, especially in the summer). In other words, shooting in the best light can be disruptive to your normal schedule.

But unless you’re willing to take advantage of early-morning or late-afternoon light—both of which reveal textures, shadows, and depth in warm and vivid tones—your exposures will continue to be harsh and contrasty, without any real warmth. Such are the results of shooting under the often flat light of the midday sun. Additionally, one can argue that the best light occurs during a change in the weather—incoming thunderstorms and rain—that’s combined with low-angled early-morning or late-afternoon light.

You should get to know the color of light as well. Although early-morning light is golden, it’s a bit cooler than the much stronger golden-orange light that begins to fall on the landscape an hour before sunset. Weather, especially inclement weather, can affect both the quality (as mentioned above) and the color of light. The ominous and threatening sky of an approaching thunderstorm can serve as a great showcase for a frontlit or sidelit landscape. Then there’s the soft, almost shadowless light of a bright overcast day, which can impart a delicate tone to many pastoral scenes as well as to flower close-ups and portraits.

Since snow and fog are monochromatic, they call attention to subjects such as a lone pedestrian with a bright red umbrella. Make it a point also to sense the changes in light through the seasons. The high, harsh, direct midday summer sun differs sharply from the low-angled winter sun. During the spring, the clarity of the light in the countryside results in delicate hues and tones for buds on plants and trees. The same clear light enhances the stark beauty of an autumn landscape.

Learning to “see” light is paramount to the ongoing success of every photographer, and often that means one must wait for the light. There’s a clear difference between these two photographs (the harbor in Deira, a few kilometers from the heart of downtown Dubai), and the difference is simply a matter of the light. Beginning photographers are often so seduced by a place or subject that they fail to note the subtle changes taking place overhead. As the sun nears the horizon, it’s a clear indication that something magical is about to happen. The once bright light of daylight is soon to be replaced with the low light of dusk and become a blue-magenta color. This welcome low light allows for long exposures, and as a result of those long exposures, some landscapes and cityscapes become quite ethereal when water is present. Shooting during these times of day will require the use of a tripod (welcome news to most shooters) as the opportunity to convey motion is presented once again.

With my camera and 24–120mm lens mounted on tripod and with an exposure time of 8 seconds at f/11, I was able to capture the streaks of boats as they meandered across the water and the numerous passing cars on the highway below, all against the backdrop of a wonderful blue-magenta sky.

Both images: Nikon D800E, Nikkor 24–120mm at 30mm, ISO 100, tripod, (top) f/11 for 1/30 sec., (bottom) f/11 for 8 sec.

You can do one of the best exercises I know near your home whether you live in the country or the city, in a house or an apartment. Select any subject, for example, the houses and trees that line your street or the nearby city skyline. If you live in the country, in the mountains, or at the beach, choose a large and expansive composition. Over the course of the next twelve months, document the changing seasons and the continuously shifting angles of the light throughout the year. Take several pictures a week, shooting to the south, north, east, and west and in early-morning, midday, and late-afternoon light. Since this is an exercise, don’t concern yourself with making a compelling composition. At the end of the twelve months, with your efforts spread out before you, you’ll have amassed knowledge and insight about light that few professional photographers—and even fewer amateurs—possess.

Photographers who use and exploit light are not gifted! They have simply learned about light and have thereby become motivated to put themselves in a position to receive the gifts that the “right” light has to offer.

Another good exercise is to explore the changing light on your next vacation. On just one day, rise before dawn and photograph some subjects for one hour after sunrise. Then head out for an afternoon of shooting, beginning several hours before and lasting twenty minutes after sunset. Notice how low-angled frontlight provides even illumination, how sidelight creates a three-dimensional effect, and how strong backlight produces silhouettes. After a day or two of this, you will be well on your way to becoming a lighting expert!

Returning to my rooftop repeatedly, I am able to make a study of light at all different times of day. You can do this, too, whether you shoot in your front yard or backyard. This is not about an effective or compelling composition but is a valuable lesson about light; it is not necessary to go anywhere. After you do this over the course of one day, don’t be surprised if you start paying more attention to the light and eventually even the seasons. That sunrise you saw this morning will be coming up in a completely different location six months from now, as you will learn when studying light.

From backlight to frontlight to dusk light, as you look at these images, your reaction to each is different. The light (or absence of light) creates a unique “personality” for each of these exposures. This is an example of what I said earlier: Each of the photographs shows a cake, but the light is the frosting.

All images: Nikon D800E, Nikkor 70–300mm at 280mm, ISO 200, (upper left) f/16 for 1/500 sec., (upper right) f/16 for 1/200 sec., (lower left) f/16 for 1/30 sec., (lower right, and above) f/16 for 4 sec.

FRONTLIGHT

What is meant by frontlight or frontlighting? Imagine for a moment that your camera lens is a giant spotlight. Everywhere you point the lens, you light the subject in front of you. This is frontlighting, and this is what the sun does—on sunny days, of course. As a result of frontlighting’s ability to, for the most part, evenly illuminate a subject, many photographers consider it to be the easiest kind of lighting to work with in terms of metering, especially when they are shooting landscapes with blue skies.

Is it really safe to say that frontlight doesn’t pose any great exposure challenges? Maybe it doesn’t in terms of metering, but in terms of testing your endurance and devotion, it might. Do you mind getting up early or staying out late, for example? The quality and color of frontlighting are best in the first hour after sunrise and during the last few hours of daylight. The warmth of this golden-orange light will invariably elicit an equally warm response from viewers. This frontlighting can make portraits more flattering and enhance the beauty of both landscape and cityscape compositions.

It was in the city of Thimphu, Bhutan that I visited a Buddhist temple one early morning and found a number of people walking in these wide circles around the temple, chanting prayers as they walked. One such woman caught my eye because of her colorful dress, her hands, and the scepter she was holding. I motioned to her in a way that suggested I would like to take her photograph, and she was quick to oblige. After I snapped a few shots of her, I explained that my next shot would be just of her hands, and the result is shown here. Note the warmth of this early morning light, in contrast to the “colorless” overhead light on the boy, opposite. This is the chief reason many seasoned pros and serious amateurs head out early: They can be assured of capturing warm frontlit and sidelit scenes.

Nikon D800E, 70–300mm at 140mm, f/11 for 1/250 sec., ISO 100

In addition, frontlighting—just like overcast lighting—provides even illumination, making it relatively easy for the photographer to set an exposure; you don’t have to be an exposure expert to determine the spot in the scene where you should take your meter reading. Even first-time photographers can make successful exposures in frontlight, whether their cameras are in manual or autoexposure mode.

I shot this young boy enjoying a summer day at Millennium Park in Chicago from a bit overhead. It is often the case with frontlit subjects that they are easy to meter for unless they are excessively bright or dark. In this case, the light levels were fairly average and uniform. I would have no problem at all if you wished to shoot scenes like this in Aperture Priority mode, but of course, I stayed the course like the old dog I am and shot in manual mode. It is clear that this is a “who cares?” exposure, so f/8 it was, and I simply adjusted the shutter speed until 1/320 sec. indicated a correct exposure.

Nikon D800E, Nikkor 24–120mm at 90mm, f/8 for 1/320 sec., ISO 100

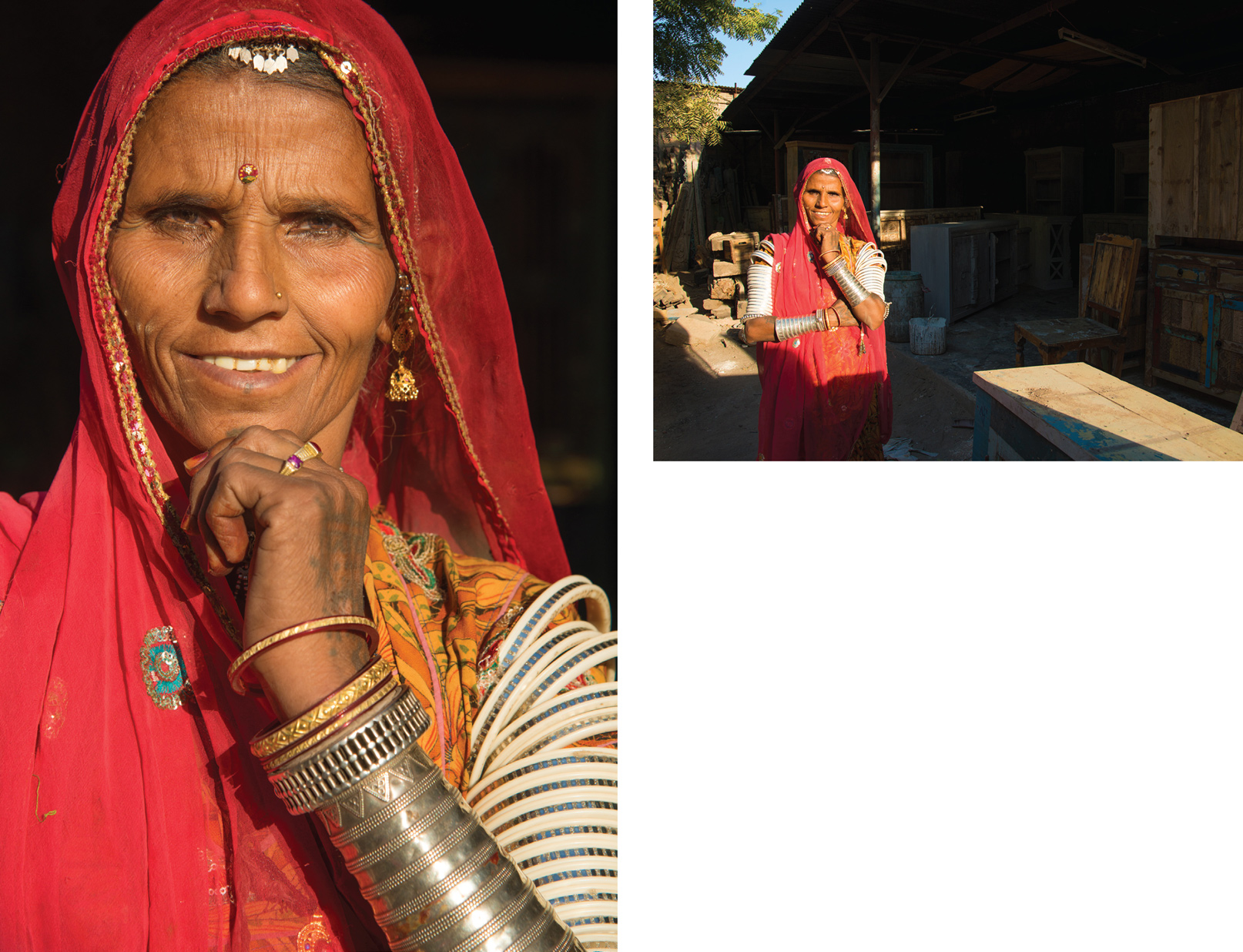

As the late-afternoon frontlight cast its glow across this large antique furniture warehouse outside the city of Jodhpur, India, a number of “shadow pockets” were seen among the many small and large storage facilities. This kind of frontlight situation is what many seasoned pros and serious amateurs look for as it allows them to serve up great contrast when placing subjects in frontlight against the backdrop of these shadow pockets. That is what I did with this Indian woman who worked at this antique store. Note how the black background serves to further heighten her colorful dress and jewelry. Since the exposure is for the sunlight that is falling on the woman (obviously a much brighter light source than the shadow behind her), the resulting shadow is recorded as a severe underexposure, so much so that it records as black. Learning to see shadow pockets is a great stride toward becoming a lighting master.

Left image: Nikon D800E, Nikor 24–120mm at 120mm, f/11 for 1/160 sec., ISO 100

OVERCAST FRONTLIGHT

Of all the different lighting conditions that photographers face, overcast lighting is the one that many consider the safest. This is because overcast light illuminates most subjects evenly, making meter reading simple. (This assumes, of course, that the subject isn’t a landscape under a dull gray sky and that sky will be part of the composition. If that is the case, it’s time to use a graduated ND filter, but we’ll talk about that later.)

Overcast light also allows one to use the semiautomatic modes such as Shutter Priority and Aperture Priority, since overall illumination is balanced. The softness of this light results in more natural-looking portraits and richer flower colors, and it also eliminates the contrast problems that a sunny day creates in wooded areas. Overcast conditions are the ones in which you may find me shooting in a semiauto mode: either Aperture Priority if my exposure concerns are about depth of field or the absence thereof or Shutter Priority if my concern is about motion (i.e., freezing action or panning).

If I had not stopped to grab a cup of tea, I surely would have missed this street vendor at Chandni Chowk Market in Old Delhi. He and I were on one of the most crowded backstreets in the market, and only because I had stopped to get some tea did I notice the comings and goings all around me, including this man sitting across from the tea shop set up against the wall you see here. Note the even illumination that the overcast skies provide. It is indeed a soft light and much kinder to the face than low-angle sunlight from the front or side. Because this was another “who cares?” composition, I called upon f/11.

Nikon D800E, Nikkor 24–120mm at 50mm, f/11 for 1/80 sec., ISO 200

Because photographing in the woods on sunny days is problematic—yielding images that are often far too contrasty—it is best to wait for cloudy days, perhaps with a bit of rain if you are so lucky! Waiting for overcast days will make getting a correct exposure much easier, and you can certainly shoot in Aperture Priority mode without fear. Along Oregon’s Columbia Gorge, up near Hood River, you will find the Rowena Gorge, which is one of the most picturesque drives in all of Oregon. On this day we had a bit of rain that would add a kind of glossy sheen to everything, but in this situation do get out your polarizer so that you can better see that glossy sheen. The polarizer will eliminate the otherwise dull glare that is on all of those wet surfaces and allow the glossy sheen to shine through.

Although this scene before me looks like a “who cares?” it is actually “deep” with detail, and so I opted to shoot it at f/16 and focus on the tree trunk itself, knowing that at f/16 the resulting depth of field would reach into the “deep” and render it sharp. I would say my plan of using f/16 worked.

Nikon D800E, Nikkor 24–120mm at 35mm, f/16 for 1/30 sec., ISO 200, polarizing filter

Portraits are another fine subject for overcast lighting. The soft, even illumination of a cloudy day or the soft, even illumination of light coming in from a north-facing window on sunny day makes getting an exposure easy.

It was during one of my workshops in Kuwait that I asked one of my students to be a model, and she gladly obliged. I placed my camera and lens on a tripod because the light levels in this old abandoned hospital were quite low. Even at my chosen aperture of f/5.6, a correct exposure was being indicated at 1/20 sec., far too slow to handhold with this particular lens, the Nikkor 35–70mm. (At this writing there are a number of lenses on the market that offer VR and IS, which are terms used for stabilization control. This is a technology that allows one to shoot at shutter speeds much slower than what is considered the norm; usually you should not handhold any lens/camera at a shutter speed slower that the lens’s maximum focal length. My Nikkor 35–70mm does not offer VR.)

I chose to shoot at f/5.6 because I wanted to keep the depth of field limited to the woman, and as you can see behind her, the area of softness increases the farther you go. Since I was using Aperture Priority automatic exposure, I only had to focus on my subject’s pleasant demeanor and shoot.

Nikon D3X, Nikkor 35–70mm at 35mm, f/5.6 for 1/20 sec., ISO 100, tripod

SIDELIGHT

Frontlit subjects and compositions photographed under an overcast sky often appear two-dimensional even though your eyes tell you the subject has depth. To create the illusion of three-dimensionality, you need highlights and shadows; in other words, you need sidelight. For several hours after sunrise and several hours before sunset, you’ll find that sidelit subjects abound when you shoot toward the north or south.

Sidelighting has proved to be the most challenging exposures for many photographers because of the combination of light and shadow, but it also provides the most rewarding picture-taking opportunities. As many professional photographers would agree, a sidelit subject—rather than a frontlit or backlit one—is sure to elicit a much stronger response from viewers because it better simulates the three-dimensional world they see with their own eyes.

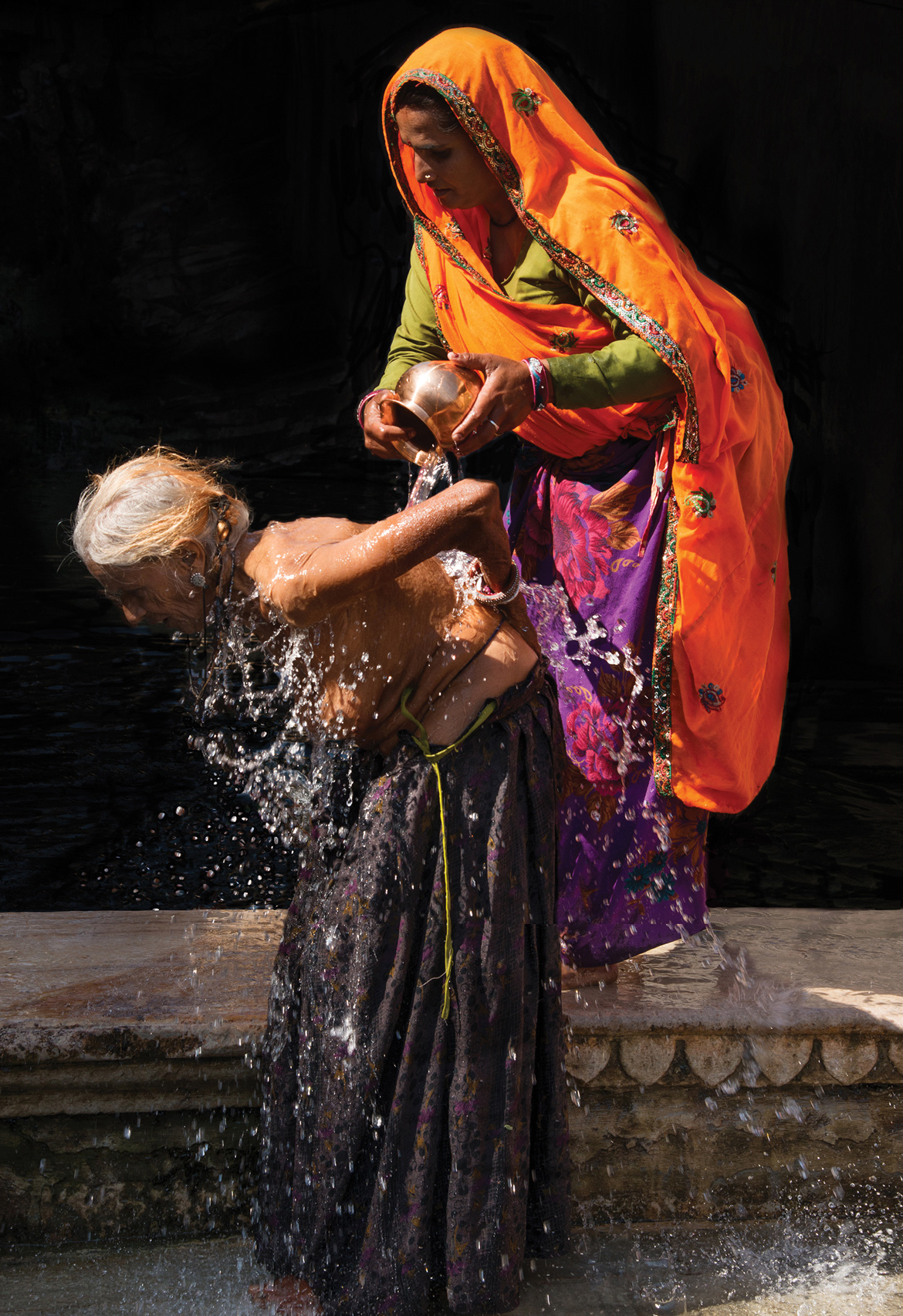

About ten kilometers outside of the city of Jaipur, India, is the Monkey Temple, and as its name implies, one will find not only people at this temple but a large number of monkeys, too. Near the top of the stairs at this temple there is a large reservoir-like body of water, and it was there that I witnessed a number of local people bathing. As usual, it was the young kids who were having the most fun, but what really caught my eye was an elderly woman being bathed by whom I assume was her daughter, or a relative at the least. The strong sidelight of the late afternoon accounted for this dramatic exposure. Directly behind them was a huge shadow pocket, and because I was metering for the much stronger sidelight that was casting its glow on them, I was assured that this large and looming shadow pocket in the background would indeed be rendered as one giant black canvas. I was equally fortunate to have been able to be set up just as she was dumping a pitcher of water across the back of the elderly woman. Because I was shooting with the “who cares?” aperture of f/8, my shutter speed was quite fast, which proved to be pivotal as the fast shutter speed also managed to freeze the action of the cascading water.

Nikon D800E, Nikkor 24–120mm at 35mm, f/8 for 1/500 sec., ISO 100

In the absence of sidelight, these letters above this small shop in the town of Cassis, France, would not appear to be “dancing” at all. It is the sidelighting and the resulting shadows that give this image its depth and dimension.

Because of the high contrast of the bright surface reflecting off the building, this was not a simple exposure. Much like snow on a sunny day, the high reflectance of this building could have caused me to record an underexposure, but experience has taught me that in situations like this, I need only shoot at a +1 overexposure.

Top image: Nikon D800E, Nikkor 70–300mm at 300mm, f/11 for 1/200 sec., ISO 100

The spaces in which I work are sometimes quite surprising to some. I mean, who would have ever thought without looking at the “before” photo seen here that this image was made on the top floor of a dirty, dusty parking garage? Yet as you can plainly see, it was! If nothing else, it certainly lends itself to the saying “Bloom where you are planted.” In other words, “Hey, we got some great sidelight right now, so let’s make this work!”

Fortunately, one of the students, Fatina, volunteered to model, and soon we were making quick work of this warm sidelight, showcasing her portrait against the white-painted wood slats of the garage’s roof. This quite graphic background also is in marked contrast to the circular shape of Fatina’s head, and so the distinction between line and shape is made evident. Because we did want a large depth of field here, we all shot at f/16.

Top image: Nikon D800E, Nikkor 24–120mm at 35mm, f/16 for 1/100 sec., ISO 100

While in Puerto Rico a few years ago, I was quick to notice the number of cats running wild in Old San Juan. While I was shooting some pigeons at a local park, I caught site of a young calico cat walking in the dappled light of a large tree. The spots of light and the numerous shadow pockets that dotted the ground intrigued me. I felt that the repeating contrast of light and dark might make an interesting photograph, but only if that repeating was pattern was interrupted. In this case, that cat became the interruption. Metering for a scene like this is really not complicated. I made it a point to move in really close and fill the frame with only a large spot of sunlight and then set my exposure accordingly. As you can see, that method worked just fine, but keep in mind that only the exposures in which the cat is seen walking in a sunny spot were effective. When he walked into a shadow pocket, he was of course too dark.

Nikon D3X, 24–85mm at 24mm, f/16 for 1/160 sec., ISO 200

BACKLIGHT

Backlight can be confusing. Some beginning photographers assume that backlighting means that the light source (usually the sun if you’re outdoors) is behind the photographer, hitting the front of the subject. However, the opposite is true: the light is behind the subject, hitting the front of the photographer and the back of the subject. Of the three primary lighting conditions—frontlighting, sidelighting, and backlighting—backlighting continues to be the biggest source of both surprise and disappointment.

One of the most striking effects achieved with backlight is silhouetting. Do you remember making your first silhouette? If you’re like most photographers, you probably achieved it by accident. Although silhouettes are perhaps the most popular type of image, many photographers fail to get the exposure correct. This inconsistency is usually a result of lens choice and metering location. For example, when you use a telephoto lens, such as a 200mm lens, you must know where to take your meter reading. Since telephoto lenses increase the image magnification of very bright background sunrises and sunsets, the light meter sees this magnified brightness and suggests an exposure accordingly. If you were to shoot at that exposure, you’d end up with a picture of a dark orange or red ball of sunlight while the rest of the frame faded to dark. And whatever subject is in front of this strong backlight may merge into this surrounding darkness. To avoid this, always point a telephoto lens at the bright sky to the right or left of the sun (or above or below it) and then manually set the exposure or press the exposure-lock button if you’re in autoexposure mode.

When photographing a backlit subject that you don’t want to silhouette, you can certainly use your electronic flash to make a correct exposure; however, there’s a much easier way to get a proper exposure without using flash. Let’s assume your subject is sitting on a park bench in front of the setting sun. If you shoot an exposure for this strong backlight, your subject will be a silhouette, but if you want a pleasing and identifiable portrait, move in close to the subject, fill the frame with his or her face (it doesn’t have to be in focus), and then set an exposure for the light reflecting off the face. Either manually set this exposure or, if shooting in autoexposure mode, press the exposure-lock button and return to your original shooting position to take the photo. The resulting image will be a wonderful exposure of a radiant subject.

Backlight is favored by experienced landscape shooters, as they seek out subjects that by their very nature are somewhat transparent: leaves, seed heads, and dew-covered spiderwebs, to name but a few. Backlight always provides a few exposure options: You can silhouette the subject against the strong backlight, meter for the light that’s usually on the opposite side of the backlight (to make a portrait), or meter for the light that’s illuminating the somewhat transparent subject. Although all three choices require special care and attention to metering, the results are always rewarding. As with so many other exposure options, successful backlit scenes result from a conscious and deliberate metering decision.

This was my first trip to Toronto and my first evening to shoot a dusk shot of the Toronto skyline. Based on the others who were also shooting near me, the sky on this night was far more dramatic than the norm. A young woman nearby was tossing bits of bread to this mallard couple, making for some wonderful foreground subject matter against the background of what was truly a stunning sunset sky!

Using the tripod I kept my 24-120mm low to the ground with the focal length at 24mm, and my aperture set to f/22 and manual focus pre-set to 1 meter. I adjusted my shutter speed until a 1/8 second indicated a correct exposure for the light reflecting off the water. Also, to impart a bit more blue to the scene, I used a White Balance of Fluorescent, which did add a bit more magenta and definitely a bit more blue to the sky.

The duck on the right is a bit soft, but not due to any focus issue but rather due to the slow shutter speed of a 1/8 sec. Why didn’t I change my ISO to 400 or 800, which would have increased my shutter speed by two or three stops, and perhaps eliminated the soft duck? I simply forgot to exercise that option!

Nikon D800E, Nikkor 24-120 mm at 24mm, f/22 for 1/8 sec., ISO 100

The area of West Friesland, Holland, is one of those places where it’s hard not to make a photograph with a strong graphic design and bold color. The many meandering dikes, perfect rows of tulips, and “walls” of trees lend themselves to exciting compositions at every turn. And almost without fail, as the sun begins its descent in the direction of the North Sea, the thick salt air diffuses the intensity of the sun’s light so that for almost the last 45 minutes of daylight, a thick orange-yellow ball hangs in the western sky.

Having witnessed this scene many times, I was excited to share it with a group of students for whom this would be their first time. As the sun did start to set, it put on a great show. Along the dike in the small town of Rustenburg, one of my students was set up on a small footbridge against the backdrop of a windmill and the setting sun. Because the sun was so diffused at this point, I simply focused on the student with my lens at f/22 and adjusted my shutter speed until a correct exposure was indicated.

When shooting backlight photos with any telephoto lens at a focal length of 100mm or more, I normally set my exposure from the sky to the right or left of the setting sun, but here, because of the strong diffusion of the sun, it was not necessary.

Nikon D3X, Nikkor 70–300mm at 165mm, f/22 for 1/60 sec., ISO 200

When backlit, many solid objects (such as people, trees, and buildings) will be rendered as dark silhouetted shapes. Not so with many transparent objects, such as feathers and flowers. When transparent objects are backlit, they seem to glow. Such was the case when I shot a single stalk of bear grass near Glacier National Park a few years ago. I chose a low viewpoint so that I could showcase the flower against the deep blue sky. Although this may appear to be a difficult exposure, it really isn’t. Holding my camera and 17–35mm lens, I set the focal length to 20mm. With an aperture of f/22, I moved in close to the flower, adjusting my position so that the sun was hidden behind the flower. I then adjusted the shutter speed until 1/100 sec. indicated a correct exposure in the viewfinder. But before I took the shot, I moved away from the flower and to the right just enough to let a small piece of the sun from behind the flower be part of the overall composition. With this exposure, I was able to record a dynamic backlit scene that showcases the lone stalk of bear grass. Finally, I used my 5 in 1 reflector and was able to nicely bounce some added light on the back of this bloom.

Nikon D3X, Nikkor 17–35mm at 20mm, f/22 for 1/100 sec., 200 ISO

One of the most colorful places I have seen over the years is the courthouse in Montreal, Quebec. One afternoon the sun was streaming through the many colorful windows so brightly that anything near the windows or directly in their path would be rendered a silhouette. Although it was not planned, I was rewarded when someone came in the courthouse and proceeded to take the escalator up to the next level. At that point I was quick to fire off two frames. I had set my exposure for the strong backlight before that person appeared, so there was no time lost fumbling around with what my exposure should be. Again, as is true of all silhouettes, the light that surrounded the subject here is much brighter than the subject, and since I metered for that much brighter light, she is rendered as a silhouette.

Nikon D800E, Nikkor 70–300mm at 300mm, f/22 for 1/200 sec., ISO 400

EXPOSURE METERS

As was discussed in the first chapter, at the center of the photographic triangle (aperture, shutter speed, and ISO) is the exposure meter (light meter). It’s the “eye” of creative exposure. Without the vital information the exposure meter supplies, many picture-taking attempts would be akin to playing pin the tail on the donkey—hit and miss! This doesn’t mean that you can’t take a photograph without the aid of an exposure meter. After all, one hundred years ago photographers were able to record exposures without one, and even thirty years ago I was able to do that. They had a good excuse, though: there were no light meters available to use one hundred years ago. I, in contrast, simply failed—on more than one occasion—to pack a spare battery for my Nikkormat FTN, and once the battery died, so did the light meter.

Just like the pioneers of photography, I was left having to rely on the same formulas for exposure offered by Kodak, the easiest being the Sunny f/16 Rule. This rule simply states: when shooting frontlit subjects on sunny days, set your aperture to f/16 and your shutter speed to the closest corresponding number of the ISO in use. In my early years, when film was the only option and I used Kodachrome 25, I knew that at f/16 the shutter speed should be 1/30 sec. When I used Kodachrome 64, I knew the shutter speed should be 1/60 sec. Needless to say, this bit of information was valuable stuff when the battery went dead—but only when I was out shooting on sunny days! One of the great advances in photography today is the auto-everything camera; trouble is, when the batteries in these cameras die, the whole camera dies, not just the light meter! Make it a point always to carry an extra battery or two.

Despite my feelings about this obvious shortcoming in auto-everything cameras, it cannot be ignored that the light meters of today are highly sensitive tools. It wasn’t that long ago that many photographers would head for home once the sun went down, since the sensitivity of their light meters was such that they couldn’t record an exposure at night. Today, photographers are able to continue shooting well past sundown with the assurance of achieving a correct exposure. If ever there was a tool often built into the camera that eliminates any excuse for not shooting twenty-four hours a day, it would be the light meter.

Exposure meters come in two forms. Either they’re separate units not built into the camera, or, as with most of today’s cameras, they’re built into the body of the camera. Handheld light meters require you to physically point the meter at the subject or at the light falling on the subject and take a reading of the light. Once you do this, you set the shutter speed and aperture at an exposure that is based on that reading. Conversely, cameras with built-in exposure meters enable you to point the camera and lens at the subject while continuously monitoring any changes in exposure. This system is called through-the-lens (TTL) metering. These light meters measure the intensity of the light that reflects off the metered subject, meaning they are reflected-light meters. Like lenses, reflected-light meters have a wide or a very narrow angle of view.

Many cameras today offer two if not three types of light-metering capabilities. One of those is center-weighted metering. Center-weighted meters measure reflected light throughout the scene but are biased toward the center portion of the viewing area. To use a center-weighted light meter successfully, you must center the subject in the frame when you take the light reading. Once you set a manual exposure, you can recompose the scene for the best composition. However, if you want to use your camera’s autoexposure mode (assuming that your camera has one) but don’t want to center the subject in the composition, you can press the exposure-lock button and then recompose the scene so that the subject is off-center; when you fire the shutter release, you’ll still record a correct exposure.

Another type of reflected-light meter that many digital cameras are equipped with is the spot meter. Until about four years ago spot meters were available only as handheld light meters, but today it is not at all uncommon to see camera bodies that are equipped with them. The spot meter measures light at an extremely narrow angle of view, usually limited to 1 to 5 degrees. As a result, a spot meter can take a reading from a very small area of an overall scene and get an accurate reading from that one very specific area despite how large an area of light and/or dark surrounds it in the scene. My feelings about using spot meters haven’t changed much since I first learned of them over thirty years ago: They have a limited but important use in my daily picture-taking efforts.

Finally, there are Nikon’s matrix metering mode and Canon’s evaluative metering mode. Matrix (or evaluative) metering came on the market about fifteen years ago and has since been revised and improved. It’s rare that you’ll find a camera on the market today that doesn’t offer a kind of metering system built on the original idea of matrix metering. This holds true for the Pentax, Minolta, Panasonic, Sony, and Olympus brands of digital SLRs. Matrix metering relies on a microchip that has been programmed to “see” thousands of picture-taking subjects, from bright white snowcapped peaks to the darkest canyons and everything in between. As you point the camera toward your subject, matrix metering recognizes the subject (“Hey, I know this scene! It’s Mount Everest on a sunny day!”) and sets the exposure accordingly. Yet as good as matrix metering is, it still will come upon a scene it can’t recognize, and when this happens, it will hopefully find an image in its database that comes close to matching what’s in the viewfinder.

The type of camera determines which light meter or meters you have built into the camera’s body. If you’re relatively new to photography and have a camera with several light meter options (matrix/evaluative as well as center-weighted), I strongly recommend using matrix 100 percent of the time. It has proved to be the more reliable and has fewer quirks than center-weighted metering. On countless field trips, I’ve witnessed some of my students switching from center-weighted metering to matrix metering repeatedly. Not surprisingly, as a result of each light meter’s unique way of metering the light, they would often come up with slightly different readings. Also not surprisingly, they were often unsure which exposure to believe, so they took one of each. This is analogous to having two spouses—and those who have a spouse would certainly agree that dealing with the quirks and peculiarities of one spouse is at times too much, let alone two. But since I was raised on center-weighted metering, I’ll stay with it for life. If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.

Just how good are today’s light meters? Both center-weighted metering and matrix metering provide accurate exposures 90 percent of the time. That’s an astounding and, I hope, confidence-building number. Nine out of ten pictures will be correctly exposed (not necessarily creative exposures but correct exposures nonetheless) whether one uses manual exposure mode (still my favorite) or semi-autoexposure mode (Aperture Priority when shooting storytelling or isolation themes and Shutter Priority for freezing action, panning, or implying motion). In either metering mode and when the subject is frontlit, sidelit, or under an overcast sky, you can simply choose your subject, aim, meter, compose, and shoot.

In addition, I recommend taking another exposure at −2/3 stop when you are shooting almost any subject, since this often improves contrast and the overall color saturation of a scene. This extra shot will give you a comparison example so that you can decide later which of the two you prefer. Don’t be surprised if you often pick the −2/3 exposure. Often, this slight change in exposure from what the meter indicates is just the right amount of contrast needed to make the picture much more appealing. With the sophistication of today’s built-in metering systems, it’s often unnecessary to bracket like crazy.

Finally, there isn’t a single light meter on the market today that can do any measuring, calculating, or metering until it has been “fed” one piece of data vital to the success of every exposure you take: the ISO. In the past, photographers using film had to manually set the ISO every time they would switch from one type of film to another.

Digital shooters, despite all the technological advances, must resort to setting the ISO for each and every exposure, in effect telling the meter what ISO to use. (On some DSLRs there is an auto-ISO feature. When it is activated, the camera will determine which ISO to use, based on the light. I do not recommend this approach at all since the camera will often get it wrong, and it doesn’t know that you desire to be a “creative photographer,” and part of your creativity stems, of course, from having full control over what ISO you use.) Since digital shooters can switch ISO from one scene to the next as well as shift from color to black and white at the push of a button, so much for the old adage that you can’t change horses in midstream.

The photo industry has come a long way since I got started. With today’s automatic cameras and their built-in exposure meters, much of what you shoot will have a correct exposure. However, keep in mind that the job of recording creatively correct exposures is still yours.

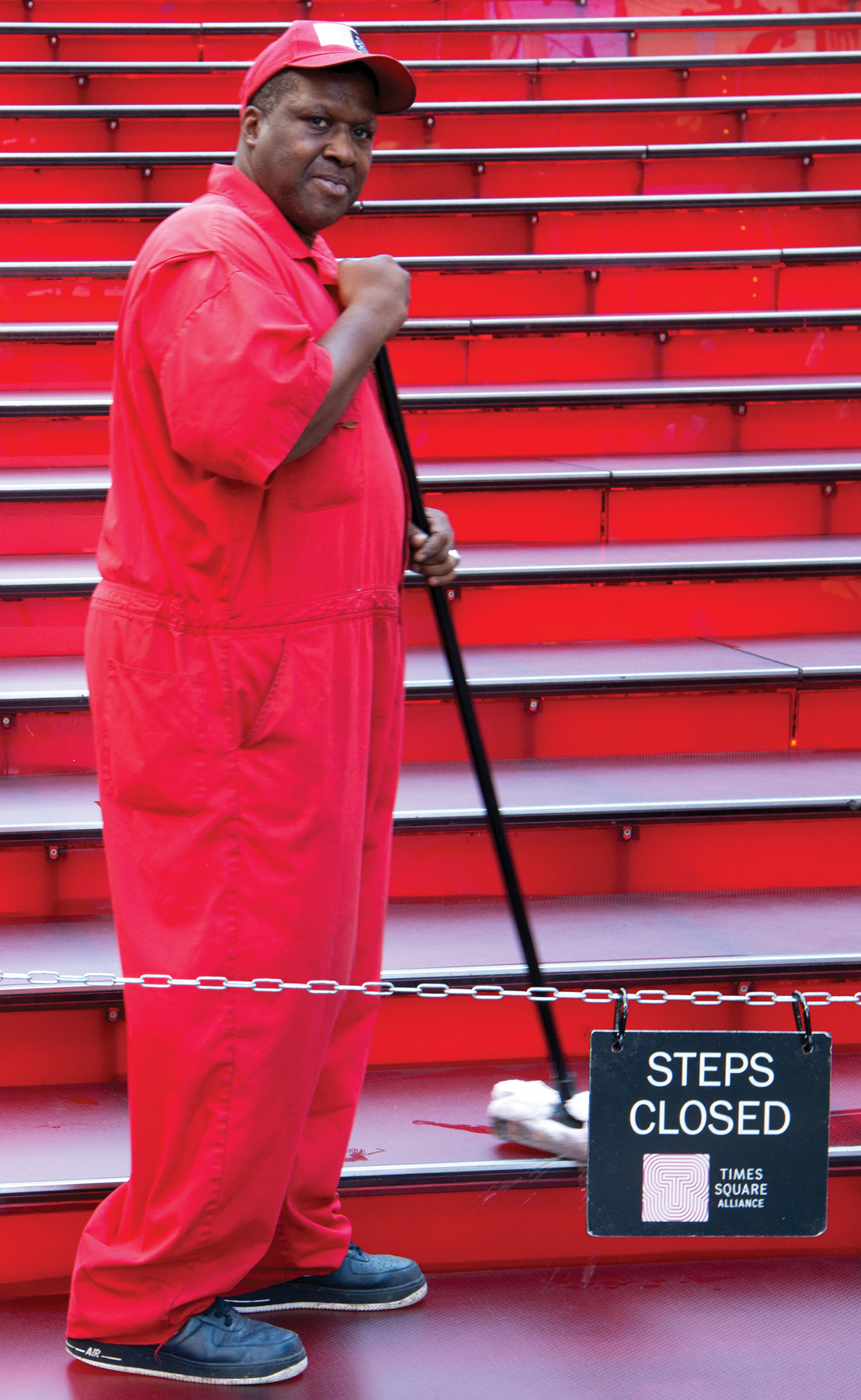

Early one summer morning, I arrived at Times Square to discover a member of the maintenance crew mopping the stairs of the large red bleacher in the heart of the square. An easy exposure for sure, since he was bathed in bright overcast light. I quickly determined the need for a storytelling aperture (since I wanted front-to-back image sharpness), so I set the aperture to f/22, and with my camera and 24–120mm lens on tripod, I allowed the camera’s Aperture Priority mode to select the correct exposure.

Nikon D800E, Nikkor 24–120mm, f/22 for 1/200 sec., ISO 100

This image could have been quite challenging to make if I had not used my camera’s built-in spot meter. All that black fabric would have played havoc with center-weighted or even matrix/evaluative metering, which would have rendered it an overexposed gray (more about this in a minute). So, with my camera’s meter set to spot metering and with my 70–300mm lens at 300mm, I pointed the lens at the advertisement of a model’s face in the distance. With an aperture of f/16, I adjusted the shutter speed until 1/60 sec. indicated a correct exposure. I then zoomed back out to 70mm and shot the exposure shown here. Keep in mind that once I had my spot meter reading, I switched back to matrix mode, where I normally set the light meter. When I did this, the light meter indicated that I was now way off. Why? Because it was seeing the large view of that “dark” telling me that I should shoot the scene at f/16 for 1/15 sec. instead of the spot meter reading that said f/16 for 1/60 sec. Of course I ignored it and shot the correct exposure of f/16 for 1/60 sec.

Nikon D800E, Nikkor 70–300mm at 300mm, f/16 for 1/60 sec., ISO 200

18% REFLECTANCE

Now for what may be surprising news: your camera’s light meter (whether center-weighted, matrix/evaluative, or spot) does not “see” the world in either living color or black and white but rather as a neutral gray. In addition, your reflected-light meter is calibrated to assume that all those neutral-gray subjects will reflect back approximately 18 percent of the light that hits them.

This sounds simple enough, but more often than not, it’s the reflectance of light off a subject that creates a bad exposure, not the light that strikes the subject. Imagine that you came across a black cat asleep against a white wall, bathed in full sunlight. If you moved in close and let the meter read the light reflecting off the cat, the meter would indicate a specific reading. If you then pointed the camera at only the white wall, the exposure meter would render a separate, distinct reading. This variation would occur because although the subjects are evenly illuminated, their reflective qualities differ radically. For example, the white wall would reflect approximately 36 percent of the light whereas the black cat would absorb most of the light, reflecting back only about 9 percent.

When presented with either white or black, the light meter freaks (“Holy smokes, sound the alarm! We’ve got a problem!”). White and black especially violate everything the meter was “taught” at the factory. White is no more neutral gray than black; they’re both miles away from the middle of the scale. In response, the meter renders these extremes onto your digital sensor just as it does everything else: as a neutral gray. If you follow the light meter’s reading—and fail to take charge and meter the right light source—white and black will record as dull gray versions of themselves.

To meter white and black subjects successfully, treat them as if they were neutral gray even though their reflectance indicates otherwise. In other words, meter a white wall that reflects 36 percent of the light falling on it as if it reflected the normal 18 percent. Similarly, meter a black cat or dog that reflects only 9 percent of the light falling on it as if it reflected 18 percent.

The skies on the Valensole Plain were filled with large cumulus and cirrus clouds that were really messing with my ability to get a correct light-meter reading of the landscape in front of me. In these kinds of situations, there are several ways to get a correct exposure of the landscape before you, but none is more foolproof than the palm of your hand since it is in all likelihood the same as a gray card as you meter your palm at a 1-stop overexposure!

In the first image the meter is being fooled by the bright sky into thinking the scene is brighter than it really is and thus wants to recommend too fast a shutter speed. Sure enough, the shutter speed it recommends creates an underexposure.

But if I stick out the palm of my hand and set an exposure at +1 for the light falling on it, I will for sure record a correct exposure. As proof, take a look at the resulting photograph. Here is the bottom line, and oh my, is it ever a great bottom line. As long as you have your hands, you can always call upon your palm to set a correct exposure. More on this on this page.

All images: Nikon D800E, Nikkor 24–120mm at 24mm, (top left) f/11 for 1/500 sec., ISO 100, (all others) f/22 for 1/200 sec., ISO 200

THE GRAY CARD

When I first learned about 18 percent reflectance, it took me a while to catch on. One tool that enabled me to understand it was a gray card. Sold by most camera stores, gray cards come in handy when you shoot bright and dark subjects, such as white sandy beaches, snow-covered fields, black animals, and black shiny cars. Rather than pointing your camera at the subject, simply hold a gray card in front of your lens—making sure that the light falling on the card is the same light that falls on the subject—and meter the light reflecting off the card.

If you’re shooting in an autoexposure program, Shutter Priority mode, or Aperture Priority mode, you must take one extra step before putting the gray card away. After you take the reading from the gray card, note the exposure. Let’s say the meter indicated f/16 at 1/100 sec. for a bright snow scene in front of you. Then look at the scene in one of these modes. Chances are that in Aperture Priority mode the meter will read f/16 at 1/200 sec. and in Shutter Priority mode it will read f/22 at 1/100 sec. In either case, the meter is now “off” 1 stop from the correct reading from the gray card. You need to recover that 1 stop by using your autoexposure overrides.

These overrides are designated as follows: +2, +1, 0, −1, and −2 or 2X, 1X, 0, 1/2X, and 1/4X. For example, to provide an additional stop of exposure when you are shooting a snowy scene in autoexposure mode, you would set the autoexposure override to +1. Conversely, when shooting a black cat or dog, you’d set the autoexposure override to −1 (1/2X).

Hot gray card tip: After you’ve purchased your gray card, you need it only once, since you’ve already got something on your body that works just as well—but you’ll need the gray card to help you initially. If you’re ever in doubt about any exposure situation, meter off the palm of your hand. I know your palm isn’t gray, but you simply use your gray card to “calibrate” your palm—and once you’ve done that, you can leave the gray card at home.

To calibrate your palm, take your gray card and camera into full sun and set the aperture to f/8. While filling the frame with the gray card (it doesn’t have to be in focus), adjust the shutter speed until a correct exposure is indicated by the camera’s light meter. Now hold the palm of your hand out in front of your lens. The camera’s meter should read that you are about +2/3 to 1 stop overexposed. Make a note of this. Then take the gray card once again into open shade with an aperture of f/8 and again adjust the shutter speed until a correct exposure is indicated. Meter your palm and you should see that the meter now reads +2/3 to 1 stop overexposed. No matter what lighting conditions you do this under, your palm will consistently read about +2/3 to 1 stop overexposed from the reading of a gray card.

So, the next time you’re out shooting and have that uneasy feeling about your meter reading, take a reading from the palm of your hand. When the meter reads +2/3 to 1 stop overexposed, you know your exposure will be correct.

(Note: For obvious reasons, if the palm of your hand meters a 2-, 3-, or 4-stop difference from the scene in front of you, either you’re taking a reading off the palm of your hand in sunlight, having forgotten to take into account that your subject is in open shade, or you forgot to take off your white gloves.)

THE SKY BROTHERS

The world is filled with color, and in fairness, the light meter does a pretty good job of seeing the differences in the many shades and tones that are reflected by all that color. But in addition to being confused by white and black, the meter can be confused by backlight and contrast. So, are we back to the hit-and-miss, hope-and-pray formula of exposure? Not at all! There are some very effective and easy solutions for these sometimes pesky and difficult exposures: they’re what I call the Sky Brothers.

Often when you are shooting under difficult lighting situations (sidelight and backlight being the two primary examples), an internal dispute may take place as you wrestle over just where exactly you should point your camera to take a meter reading. I know of no one more qualified to mediate these disputes between you and your light meter than the Sky Brothers. They’re not biased. They want only to offer the one solution that works each and every time. So, on sunny days, Brother Blue Sky is the go-to guy for those winter landscapes, black Labrador portraits, bright yellow flower close-ups, and fields of deep purple lavender. This means you take a meter reading of the sunny blue sky and use that exposure to make your image. When you are shooting backlit sunrise and sunset landscapes, Brother Backlit Sky is your go-to guy. This means you take a meter reading to the side of the sun in these scenes and use that reading to make your image. When you are shooting city or country scenes at dusk, Brother Dusky Blue Sky gets the call, meaning you take your meter reading from the dusk sky. And when you are faced with coastal scenes or lake reflections at sunrise or sunset, call on Brother Reflecting Sky, meaning you take your meter reading from the light reflecting off the surface of the water.

With my camera and lens mounted on tripod and using manual exposure mode, I simply framed up this idyllic winter scene just off Chicago’s Lakeshore Drive. While pointing the lens and camera to the sky, I adjusted my meter until a correct setting was indicated—and, not surprisingly, I got white snow. We all know snow is white, especially on a clear frontlit afternoon, so if you have any intention of recording pure white snow, you really should take your meter reading from Brother Blue Sky.

Of course, after I metered the blue sky and recomposed the snow scene before me, my light meter told me I was wrong, but sometimes, just as occurs when a 2-year-old throws a tantrum, you have to ignore it!

Nikon D800E, Nikkor 17–35mm at 17mm, f/22 for 1/60 sec., ISO 100

Warning: Once you’ve called upon the Sky Brothers, your camera’s light meter will let you have it. You’ll notice that once you’ve used Brother Blue Sky and set the exposure, your light meter will go into a tirade when you recompose that frontlit winter landscape (“Are you nuts? I’ve got eyes of my own and I know what I’m seeing, and all that white snow is nowhere near the same exposure value of Brother Blue Sky!”) Trust me on this one. If you listen to your light meter’s advice and subsequently readjust your exposure, you’ll end up right back where you started—a photograph with gray snow! So, once you have metered the sky using the Sky Brothers, set the exposure manually or “lock” the exposure if you are staying in automatic before you return to the original scene. Then shoot away with the knowledge that you are right no matter how much the meter says you’re wrong!

Last spring Chicago had a “late” snowfall, April 11 to be exact (for this city, that is not all that late). Nonetheless, I rushed downtown the next morning in hopes of catching some shots of the “Bean” with some of the late snowfall remnants, and I was in luck! There were still patches of snow clinging to the Bean, and those patches reminded me of cumulus clouds. I made quick work of moving in close and creating the composition of the “clouds” you see here, but not before setting my exposure from the blue sky to the right of the Bean.

Top image: Nikon D800E, Nikkor 24–120mm at 80mm, f/22 for 1/100 sec., ISO 200

I met Ivan while shooting near his place of work in Dubai. Ivan left Nigeria to come to Dubai and work as a security guard. We talked about how much he missed his girlfriend, and he hoped that after seeing his portrait, which he planned to send her, “she will immediately come to her senses and join me in Dubai.” I do not know how that story ended, but we both agreed that the picture of Ivan would be well received by other ladies if his current girlfriend chose to no longer be in his life.

I had asked Ivan to stand in front of the entrance to his place of work and do nothing more than look at the camera and smile. As if I didn’t know better, I proceeded to adjust my shutter speed until a correct exposure was indicated and then shot the first picture you see on top; not surprisingly, it is overexposed. Again this is not the light meter’s fault since it thinks the world is always gray, and when metering Ivan and his surroundings, all quite dark, the meter reacted as if to say, “Hey, I am not sure why you are not reflecting 18 percent of the light, but no worries, I will make you ‘gray.’ ” In effect, the light meter is suggesting a reading that ends up overexposing Ivan. The solution is a simple one in this case: take a meter reading from his very neutral blue-graylike shirt, which is about as close to 18 percent reflectance as you will get. When I did that and shot at this exposure, notice the difference. Ivan looks like the Ivan I met and the Ivan he knows as well!

Both images: Nikon D800E, Nikkor 24–120mm at 85mm, ISO 200, (top) f/11 for 1/40 sec., (bottom) f/11 for 1/100 sec.

MR. GREEN JEANS (THE SKY BROTHERS’ COUSIN)

Mr. Green Jeans is the cousin of the Sky Brothers. He comes in handy when you are exposing compositions that have a lot of green in them (you take the meter reading off the green area in your composition). Mr. Green Jeans prefers to be exposed at −2/3. In other words, whether you bring the exposure to a close by choosing either the aperture or the shutter speed last, you determine the exposure reading to be “correct” when you see a −2/3 stop indication (which means you adjust the exposure to be −2/3 stop from what the meter tells you it should be). If there’s one thing I’ve learned about Mr. Green Jeans, it’s that he’s as reliable as the Sky Brothers, but you must always remember to meter him at −2/3.

This is a classic example both of what the light meter wants to do when confronted with white (in this case the white water of a waterfall) and of the need for Mr. Green Jeans. The first image is the result of leaving the meter to its own way of thinking: gray water. Not only is the water underexposed, so is the surrounding green tree.

So I swung the camera and lens to Mr. Green Jeans (the area shown in the second image) and readjusted the aperture until f/18 indicated a −2/3 underexposure and then recomposed the scene with the waterfall. Of course, when I swung the camera back to the waterfall, my light meter indicated that a different exposure was required, but I ignored it. I was right and the meter was wrong.

Both images: Nikon D800E, Nikkor 70–300mm at 210mm, ISO 100, (left) f/32 for 1/4 sec., (right) f/18 for 1/4 sec.

NIGHT AND LOW-LIGHT PHOTOGRAPHY

There seems to be an unwritten rule that it’s not really possible to get any good pictures before the sun comes up or after it goes down. After all, if there’s no light, why bother? However, nothing could be farther from the truth.

Low-light photography and night photography pose special challenges, though, not the least of which is the need to use a tripod (assuming, of course, that you want to record exacting sharpness). But it’s my feeling that the greatest hindrance to shooting at night or in the low light of predawn lies in the area of self-discipline: “It’s time for dinner” (pack a sandwich); “I want to go to a movie” (rent it when it comes out on DVD); “I’m not a morning person” (don’t go to bed the night before); “I’m all alone and don’t feel safe” (join a camera club and go out with a fellow photographer); “I don’t have a tripod” (buy one). If it’s your goal to record compelling imagery—and it should be—night photography and low-light photography are two areas where compelling imagery abounds. The rewards of night and low-light photography far outweigh the sacrifices.

Once you pick a subject, the only question that remains is how to expose for it. With the sophistication of today’s cameras and their highly sensitive light meters, getting a correct exposure is easy even in the dimmest light. Yet many photographers get confused: “Where should I take my meter reading? How long should my exposure be? Should I use any filters?” In my years of taking meter readings, I’ve found there’s nothing better—or more consistent—than taking meter readings off the sky. This holds whether I’m shooting backlight, frontlight, sidelight, sunrise, or sunset.

If I want great storytelling depth of field, I set the lens (i.e., a wide-angle lens for storytelling) to f/16 or f/22, raise my camera to the sky above the scene, adjust the shutter speed for a correct exposure, recompose, and press the shutter release.

Nikon D3X, Nikkor 24–85mm, ISO 100, at 60mm

One of the most dramatic bridges in the southeastern United States has to be the suspension bridge in Charleston, South Carolina. I remember the first time I was setting up to shoot this bridge at sunset; there were perhaps as many as eight to ten other photographers nearby, and as the sun started to set, I heard two guys talk with elation about the great shots they had just gotten as they were leaving. I shook my head in disbelief. In another twenty to twenty-five minutes a much better shot would unfold if they were willing to wait.

In my first exposure (shown previously), it was a simple aim and shoot since the focal length I was using, 60mm, does not increase the intensity of the sun’s light the way a 200mm or 300mm lens would. Nikon’s matrix metering handled this exposure just fine. As nice as the resulting exposure was, it was the second image that I consider the real prize.

About twenty minutes after the sunset shot was made, I placed my camera on tripod, set the aperture to f/11, and placed my one and only colored filter, a magenta-colored filter, the FLW to be exact, on the front of the lens. With the lens now pointed to the dusky blue sky above the bridge, I adjusted the shutter speed until 13 seconds indicated a correct exposure. I then recomposed the scene you see above, and with the camera’s self-timer set, I pressed the shutter release. I use the self-timer with “long” exposures simply to avoid any contact with the camera during the exposure time. I don’t want to risk any camera shake, since sharpness is paramount almost every time I record an exposure.

Note that your camera’s default for the self-timer is usually a 10-second delay, but I would strongly recommend that you consider changing this to a 2-second or 5-second delay. Waiting 10 seconds between shots can often mean not getting the shot. (To be clear, you can also use a cable release, but even here there’s the slight risk of camera shake, since you’re still “tied” to the camera.)

Nikon D3X, Nikkor 24–85mm, ISO 100, at 85mm, f/11 at 13 sec.

Without a tripod, a night shot like this just isn’t going to happen, especially when you are going to be the one to run into the shot and hold a pose to bring some scale to the scene.

This is the brain clinic in Las Vegas, designed by the architect Frank Gehry. I was not leaving Las Vegas without photographing it, and fortunately for me and several of my students, we had the pleasure of meeting the security guard. She wanted to make sure we got a great shot, so she offered to turn on the colored lights inside the clinic while the sky was a dusky blue.

With my camera on tripod, I first set my aperture to the “who cares?” choice of f/11 (since everything was at the same focused distance: infinity). I then tilted the camera to Brother Dusky Blue Sky and adjusted the shutter speed until 4 seconds indicated a correct exposure. After that, it was simply a matter of recomposing the scene, and with the camera’s self-timer engaged, I fired off the first frame you see here (top). As much as I liked it, I felt it needed a sense of scale. I would take a “selfie”! With the self-timer set to a 10-second delay (instead of the normal 2-second delay) I was able to run into the scene and hold my position on the side of the building, appearing as if I were about to begin climbing the building. Of the three images, I prefer the one with “that” guy in it (bottom).

All images: Nikon D800E, Nikkor 24–85mm at 24mm, f/11 for 4 sec., ISO 200

When I made this long exposure of the pier at Folly Beach in South Carolina, I was grateful that I had arrived as early in the morning as I had. The “streetlights” of the pier were still on, and those lights, small as they are, add some much needed contrast to an otherwise flat image. Making dusky blue exposures does not require the dusky blue that follows sunset, as is obvious here. There is no shortage of dusky blue light before sunrise—about forty-five minutes or so before sunrise to be exact. Yep, I am sure I just lost about four-fifths of you with that comment, but to those of you who are still with me, I’m going to assume you can set an alarm and need to know that you don’t meter any differently! In this case I pointed the camera and lens to the dusky early morning blue sky above the pier, and with my aperture set to f/22, I adjusted the shutter speed until 13 seconds indicated a correct exposure. With the camera and lens on tripod, I recomposed the scene you see here with my 17–35mm lens at 17mm and tripped the shutter by engaging the camera’s self-timer.

Nikon D800E, Nikkor 17–35mm at 17mm, f/22 for 13 sec., ISO 100

When shooting the Telus World of Science building and a portion of the distant Vancouver skyline, I used a filter I can’t live without (besides the polarizer and my LEE 3-stop graduated): the FLW. It’s a magenta-colored filter that is not to be confused with the FLD. The magenta color of the FLW is far denser and is far more effective on normally greenish city lights, giving them a much warmer cast. Additionally, this filter imparts its magenta hue to the sky, and that makes it perfect for nights when there isn’t a strong dusky blue sky.

With my camera mounted on a tripod, I chose to shoot at f/11. I pointed the camera to the sky above and adjusted the shutter speed until 15 seconds indicated a correct exposure and then recomposed and recorded the exposure you see here.

Nikon D800E, Nikkor 24–85mm at 24mm, f/11 for 15 sec., ISO 200

The Punakha Dzong in Bhutan without question provides one of the finest opportunities to convey a sense of both tranquility and motion during a time exposure under the light of the full moon. This exposure, although it appears difficult, is quite easy to make. Directly overhead a full moon was illuminating much of the landscape in front of me, but I still needed to ensure that my use of the foreground foliage would be visible during this 30-second exposure. It was then that I used a flashlight that I carry with me in my camera bag, and over the course of the 30-second exposure I waved the flashlight repeatedly over the green branches. Of the three 30-second exposures I made, this one turned out the best.

How did I determine that a 30-second exposure was the correct one? Again, with my aperture set to f/22, I merely pointed the camera and lens into the sky that you see straight ahead, above those hills, and adjusted my shutter speed until 30 seconds indicated a correct exposure.

Nikon D800E, Nikkor 17–35mm at 20mm, f/22 for 30 sec., ISO 200

While many photographers watch the large and looming moonrise, few photograph it because they aren’t sure how to meter the scene. Surprisingly, a moonrise is easy to expose for. They are actually just frontlit scenes, the same frontlit scenes found in daylight, but in lower light. So what’s the “secret” to getting a correct exposure?

Because depth of field was not a concern, I set the aperture on my 70-300mm lens to f/11 and called upon my friend, Brother Dusky Blue Sky. Metering the light in the sky around the moon, I adjusted my shutter speed until a 1/8 second indicated a correct exposure. With the camera on tripod, I then recomposed the scene and using the camera’s two second delayed self timer, I fired the shutter release button.

With moon landscapes, it’s best to shoot the day before the calendar says the moon will be full. Why? Because moons are often fullest early in the morning of the calendar day listed—meaning the time to shoot the fullest moon rise is the night before.

Top image: Nikon D800E, Nikkor 70-300mm at 280mm, f/11 at 1/8 sec., ISO 200

FLASHLIGHTS AND STARLIGHT

Some thirty years ago, I saw an advertisement for The Lazy Man’s Way to Riches. I never bought the book, but from what I could determine, it was about buying real estate and how you end up making huge financial gains with other people’s money. I do not know if the plan worked for the millions who bought the book, but certainly it was working for the man who wrote it.

I’m here to tell you that you too can make millions while sitting in a lounge chair out in the middle of a desert: millions of tiny exposures, that is!

I am referring to the millions of bright stars that come out at night and are best seen in the country, away from the artificial lights of the city. Read on to learn how to capture starlight.

It was during night in the Arizona desert that I shot this single 30-second exposure. My motivation to shoot a single 30-second exposure was provided by the sound of a lone motorcycle that I could hear coming down the highway. With my camera and tripod set up alongside the shoulder of the road, I waited to start the 30-second exposure until the motorcycle had just entered the frame from the right. This explains why there is no trailing taillight coming into the frame, although it starts once the motorcycle is well inside the frame. As you can see, I recorded not only the taillight but also the illuminated roadway in front of the motorcycle thanks to the headlight. I also captured the single points of light from many of the stars in the western sky on this otherwise very quiet night in the Arizona desert.

Nikon D800E, Nikkor 16–35mm at 22mm, f/5.6 for 30 sec., ISO 1600

On more than one occasion while in the country or desert, I have set up my tripod and camera and pointed it toward the North Star, attached my cable release, set the ISO to 1600 and the aperture to f/5.6, and proceeded to make a minimum of sixty 30-second exposures, one right after the other, all while seated in my lightweight lawn chair. Lately, I’ve started to bring along my Bluetooth Bose speaker and listen to music while recording these 30-second exposures of the millions of stars overhead; this is truly a lazy man’s way to record the riches of the universe!

Upon completion of my night out, I return to the studio, and if not that same evening then certainly the next morning, I will load the images into Photoshop and call upon that program’s ability to stack and process all the images into a single exposure. The stacking process is truly easy, and there are countless video tutorials on YouTube that explain just how to do it. Be assured that after a brief 5 to 7 minutes from start to finish, which includes loading your images into the computer, you will end up with the same sixty images all stacked together into a single exposure that looks much like the image you see here. Because the earth was rotating during that combined 30 minutes of exposure time, you will see the stars “arching” across the sky.

If you want even more arching, you can simply keep shooting additional 30-second exposures for upward of 3 to 4 hours if you wish. And all the while, you sit back in your lounge chair and listen to the night air or your music and try not to fall asleep.

Nikon D800E, Nikkor 16–35mm at 16mm, f/5.6 for 30 sec. (60 exposures total), ISO 1600

LIGHT PAINTING

If we think of the digital sensor as a blank canvas (a good habit to get into), it might be easier to appreciate the surprising results of light painting. We are able to paint these “canvases” using long exposure times that allow us to draw with artificial light sources such as flashlights and small LED light panels.

In the normal everyday world of image making, most of us associate exposure with shutter speeds that are often faster than the blink of an eye, yet when it comes to light painting, the exposure times are more often than not seconds and sometimes even minutes. Unlike an actual painter’s canvas, where oils or acrylics are used, your materials will be flashlights, sparklers, and even your electronic flash and any number of assorted colored gels. Depending on the time of day you choose to begin your light painting, you will find yourself on occasion calling upon your 2- to 8-stop variable neutral-density filter.

Effective light painting as a general rule relies on exposure times of 8 seconds or longer, even minutes, yet there are exceptions to this rule. Your exposure time will be determined in part by the time of day, the aperture in use, the selection of your ISO, and, as was mentioned a moment ago, the addition of any filters, including an ND filter.

One of my neighbors, Aya (which means “colors” in Japanese), agreed to assist me with a simple light painting trick. Before turning off most of the lights in my studio, I asked Aya to lie down on the edge of my bed and fan her hair out across the black sheets. I then set up my camera and tripod, and while framing up the tight close-up of her face that you see here, I also focused on her eyes and then turned off autofocus. With the aperture set to f/16 and the ISO at 100, I knew from experience that I would be able to “paint” for about 2 seconds maximum before I ran the risk of an overexposure from the small flashlight. With the shutter speed setto 2 seconds and with my cable release attached to the camera, I was ready. I turned off the lights and tripped the release, and for the next 2 seconds I began painting her with an ordinary flashlight in a diagonal up-and-down fashion, making certain to light only those areas around the eyes that I wished to record during the exposure. As you can see in the resulting image, only the cheek and part of Aya’s lips are lit, and the “spillover” light was able to illuminate those areas near her cheek and lips, including some of her hair. This very controlled “spot light” technique is one of the unique characteristics of painting with a narrow-beam flashlight.

Nikon D800E, Nikkor 24–120mm at 120mm, f/16 for 2 sec., ISO 100, tripod

Whether you are visiting the beach, the desert, the mountains, the city, or your own backyard, the opportunity to paint presents itself every day around dawn or shortly after sunset. It does not matter what time of year it is or if it’s cloudy, clear, raining, or snowing. All that matters is that you use no less than an 8-second exposure time.

It was at a workshop in New Zealand that a willing student posed for all of us against the remnants of an impressive sunset that had taken place 15 minutes earlier. With his arms outstretched and a willingness to hold still as well as he could, I quickly made an outline of his body with two flashlights, one covered in a blue gel and the other in a red gel. Then, with a third flashlight covered in a yellow gel, I made a swirling motion with my hand as I walked out of the frame during the final 2 seconds of this 15-second exposure.

Much of light painting is trial and error. Sometimes success comes easily, but at other times it seems to elude you no matter how hard you try. But one thing is certain: it is an area of exposure that is well worth exploring and one where there are still many new discoveries to be made.

Nikon D300S, Nikkor 17–55mm at 17mm, f/22 for 15 sec., ISO 200, tripod