A SUMMARY ASSESSMENT FOR PART 1

P rofessor Israel Finkelstein initiates his introductory essay with a précis on the relationship between archaeology and the biblical text in modern scholarship. He begins with the nineteenth-century higher-biblical critic Julius Wellhausen and continues well into the twentieth century with what he views as the two dominant opposing schools that emerged, the German and the Anglo-American traditions. Finkelstein adopts as his general starting point that of the higher-critical approach along with some important recent revisions, while he sums up the Anglo-American school as essentially a conservative approach. In the latter case, archaeology has played only a supportive role to the sequential straightforward reading of the biblical text, or, as Finkelstein describes it, “a modern, almost word-for-word rewriting of the biblical story.” He then suggests that this in turn explains, at least in part, why biblical archaeology “stalled” in terms of its contributions to the wider field of archaeology. He ends his survey with a summary and critique of a third, more-recent school, that of the so-called minimalists. He describes the minimalist position as follows: “Biblical history totally lacks an historical basis and its character as a largely fictional composition or wholly imaginative history is motivated by the theology of the time of its compilation in the Persian or Hellenistic periods, centuries after the alleged events took place. At best, it contains only vague and quite unreliable information about early Israel. Yet, the continuing power of the biblical narrative is testimony to the literary skill of the authors as they produced a compelling propagandistic work to a highly receptive public.”

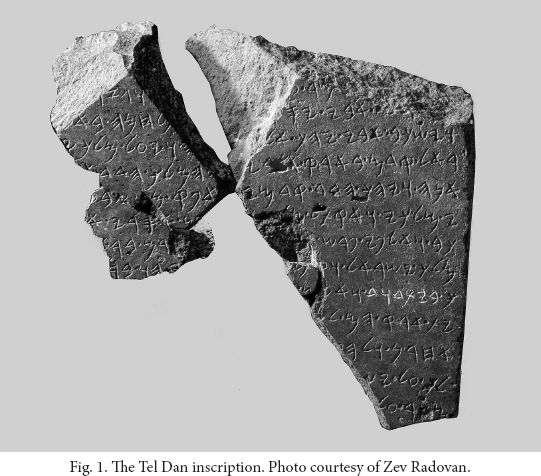

Finkelstein, however, notes that archaeological surveys, settlement studies, and extra-biblical historical records converge with the biblical traditions at numerous points having to do with geographical and historical matters pertaining to the Iron Age. He asks rhetorically whether or not this is mere coincidence and then goes on to describe such a possibility as “amazing” and the extensive administrative details in the Deuteronomistic History (Deuteronomy or Joshua through 2 Kings) “unnecessary,” that is, if it is purely a mythic history. Among other arguments supporting the convergence of these otherwise independent lines of historical information, Finkelstein invokes the Iron II-period reference to the occurrence of the name (and dynasty) of David, “the House of David” or bytdwd in the Tel Dan inscription (fig. 1 ), a fragment of a larger commemorative stele erected most probably by Hazael, king of Damascus, following his conquest of the Galilee. This datum strikes a serious blow to the minimalist position he described earlier on the non-historicity of the biblical character that goes by the same name.

Finkelstein boldly claims that archaeology is the only real-time witness to events described in the biblical text, particularly those relating to the formative phases of early Israelite history. This is so because the biblical text is dominated by theological and ideological themes of the authors and their times. Finkelstein cites three examples of archaeology’s contribution to the quest for the early historical Israel. First, he cites the archaeological evidence for the importance of Shiloh in the late-eleventh to the early-tenth centuries B.C.E.

and its insignificance during the following Iron II period. Then he refers

to the evidence for a society in the Iron I period that included bands of migratory peoples wandering along the margins of urban developments while the same areas in the Iron II period were densely settled and migratory bands no longer existed. Finally, Finkelstein invokes the material cultural data documenting the prominence of the Philistine city of Gath (Tell e![]() -

- ![]() âfi) in the ninth century B.C.E.

and earlier, as well as its demise over the course of the following two centuries.

âfi) in the ninth century B.C.E.

and earlier, as well as its demise over the course of the following two centuries.

These he concludes, affirm the antiquity of portions of the stories about David and his times in 1 Samuel, and specifically those traditions concerning Shiloh’s importance, those about David and his band of renegades wandering along the southern reaches of Judah, and the references to Philistine Gath’s prominence in the David stories. For Finkelstein, all three also allow him to generalize in the following fashion; preserved in biblical traditions are older myths, tales, and memories that served as the nuclei for the stories composed by biblical authors. Although older stories can on occasion and in exceptional cases be detected in the biblical texts, more typically they are preserved in such a manner that reflect multiple layers and multiple realities from an earlier past and are at other times too well integrated into the ideology of the later biblical authors to be isolated in any meaningful way. Thus, as his own methodological starting point, Finkelstein proposes that biblical history should be read through the filter of its point of departure, which for him is the period of its compilation in late-monarchic times, most likely during the reign of King Josiah—not the later Persian or Hellenistic periods as the minimilists have proposed, or, for that matter, the earlier tenth century as Anglo-American scholarship has traditionally upheld. As the archaeological evidence seems to indicate, this is the period of Judah’s dramatic growth toward full statehood and widespread literacy and, more to the point, it is from this period of Israel’s early history that the biblical traditions can provide the modern historian with the most amount of socio-historical information.

Professor Amihai Mazar introduces his essay by surveying the modern history of archaeology in Israel as well as some of the major changes and new directions that biblical archaeology has undergone in terms of its methods and goals. He defends the concept of a “biblical archaeology” as referring to archaeological activity that pertains to the world of the Bible and as upholding what he views as the essential relationship between artifact and text. He then turns to the question of the historical relevance of the biblical text for reconstructing early Israel’s history. For Mazar, this issue lies at the heart of the current controversy over the modern quest for the historical Israel. One means of productively pursuing that question is to employ the findings of archaeology as an independent, if not the primary, witness to the ancient historical reality and as a litmus test for assessing the historical relevance of any given biblical text. Archaeology, for Mazar, remains invaluable in spite of the subjective aspects of the enterprise. Mazar’s provisional conclusion regarding the historical relevance of the biblical texts is that, in spite of the literary creativity and ideological biases of the writers as well as the presence of textual complexities resulting from other mediating influences, blocks of biblical materials may have historical relevance and may even preserve ancient pre-Israelite local memories. He lists as examples of what he deems as earlier materials and sources the following: archives in Jerusalem’s temple library, palace archives, public commemorative inscriptions (on the analogy provided by the Mesha and Tel Dan inscriptions), oral transmission of ancient poetry (for example, Gen 49, Deut 32, and Judg 5), folk and aetiological stories rooted in the remote past (for example, portions of the Exodus and Conquest narratives, the deeds of the Judges, and biographical information on Saul, David, and Solomon), and historiographic writings explicitly mentioned by the biblical writers (for example, “the books of the chronicles of the kings of Israel”).

For Mazar, accepted historical methods, external written sources and archaeological finds enable us to extract reliable historical information embedded in the biblical texts with archaeology functioning as a control tool offering increased objectivity. Mazar cites as an example of this the convergence of historical data from the Assyrian royal inscriptions, the Mesha inscription, the Tel Dan inscription, and the biblical text. Mazar concludes that these written sources, when taken together, confirm that the general historical framework of the Deuteronomistic History relating to the ninth century B.C.E. was based on reliable knowledge of that time period. Even so, Mazar remains more skeptical about the modern enterprise of writing an accurate history of early Israel and especially when it comes to the earliest stages of her past. He imagines the historical perspective preserved in the Bible as a telescope looking back in time. The farther back one goes from what Mazar views as the pivotal period of biblical composition, that is, the eighth to seventh centuries B.C.E. , the more imaginative, symbolic, distorted, and “foggier” that past becomes. In addition, one must take into account the impact that such factors as distortion, selectivity, memory loss, censorship, and ideological or personal bias might have brought to bear on the composition of the resultant biblical traditions.