THE

SEARCH

FOR

DAVID

AND

SOLOMON

:

AN

ARCHAEOLOGICAL

PERSPECTIVE

A s one reads the Hebrew Bible, one imagines David and Solomon as rulers of a powerful, mature state (sometimes denoted as an “empire”) and Jerusalem as a large and prosperous capital, at least large enough to contain Solomon’s one thousand wives. One would also expect dense urban settlements throughout the country, official inscriptions and various art forms. It has been the professional opinion of many historians and archaeologists that indeed this was the case, and the depiction of Solomon’s kingdom that for so long had been developing in archaeology seemed to fit the traditional image portrayed in the Bible.

Yet, during the last two decades, a good number of scholars have grown increasingly skeptical concerning both the historical validity of the biblical descriptions, as well as the archaeological conclusions regarding the tenth century B.C.E. , the supposed time of David and Solomon. While others retained the older, conservative approach, accepting much of the biblical narrative at face value, there have been several arguments cited against the historicity of the United Monarchy: the kingdom is not mentioned in any written sources outside of the Bible; Jerusalem, its supposed capital, was either entirely unsettled or comprised only a small village during the tenth century; literacy is hardly attested during this period; the population density was sparse; there is no evidence for international trade, and so forth. Scholars have also claimed that the biblical texts relating to David and Solomon should be read as fictional literature, theologically and ideologically motivated national sagas intended to glorify a supposed past golden era in the history of Israel.

As I will attempt to show, this deconstruction of the United Monarchy has gone too far. Though indeed many of the biblical narrative stories related to this period should not be taken at face value, it is a long way to go from there to the total negation of the United Monarchy as an historical reality.

Let us start with the fact that many of the same scholars who deny the historicity of the United Monarchy do accept the historicity of the Northern Kingdom of Israel ruled by Omri and Ahab in the ninth century. They do so to a large extent since the latter is mentioned in Assyrian, Moabite, and Aramean documents external to the Bible. Yet, the time lapse between the United Monarchy and the Omride dynasty is less than a century, while several centuries separate the ninth century from the supposed time when the biblical texts were composed, namely the seventh century B.C.E. If in fact the early version of the Deuteronomistic History is to be dated to the seventh century B.C.E. or later, as generally accepted, and if the Bible preserves accurate information regarding the Omride dynasty of the ninth century, then why should one accept the view that all of the information concerning David and Solomon is imaginative? Furthermore, the ninth-century Assyrian inscriptions mentioning Israel result from the fact that the Assyrian Empire was established during that century and left us historical inscriptions, while for the tenth century such documents are lacking, since there was no external power to write them. The one exception is Sheshonq I’s inscription from the Temple of Amun at Karnak, to which we will return later. There is no logic in acknowledging the historicity of the biblical account regarding ninth-century northern Israel but discrediting the historicity of the United Monarchy of the tenth century or for that matter, that of Judah in the ninth century—that is, unless the claim is based on clear archaeological indications. This is why archaeology has become so important for evaluating the historicity of the United Monarchy. In the light of this argumentation, let us examine how archaeology may or may not support one of the two positions outlined above, or perhaps how it might guide us in a third direction.

IRON AGE CHRONOLOGY AND HISTORICAL INTERPRETATION

A condition for archaeological interpretation of any period is an accurate chronology that will enable one to comprehend the nature of the material remains from a certain time period, in our case the tenth century B.C.E. The archaeological period under discussion is termed by most archaeologists “Iron IIA.” It is characterized by a significant change in material culture, as particularly expressed in pottery production. The earlier Canaanite painted-pottery traditions that survived in the plains until the early-tenth century gave way to a new style, characterized by both new forms and the appearance of red slip and irregular hand-burnished wares. This new pottery tradition and the cities and settlements where it was found were traditionally dated to the tenth century B.C.E. , the time of the United Monarchy. Israel Finkelstein has suggested lowering the chronology of archaeological assemblages in Israel that were traditionally attributed to the twelfth to tenth centuries by seventy-five to one hundred years. This wholesale lowering of dates results in the removal of archaeological assemblages from the tenth century that have served for about half a century of scholarship as the bases for the archaeological portrait or paradigm of Solomon’s kingdom. This suggested “Low Chronology” supposedly supports the replacement of this paradigm by a new one (in fact, similar to one presented earlier by David Jamieson Drake and others), according to which the kingdom of David and Solomon either did not exist or comprised at best a small local entity. According to this suggestion, the first Israelite state documented in the archaeological record was northern Israel under the Omrides of the ninth century B.C.E.

This reconstruction has generated an extensive debate that is still ongoing. A major issue is the perennial chicken-or-the-egg question: Was the Low Chronology born out of an independent archaeological endeavor or as an archaeological response to a certain historical paradigm? In each of Finkelstein’s papers on this issue, the archaeological discussion is intermingled with an evaluation of state formation in Israel and Judah in a manner that does not allow for any differentiation between cause and effect. So, one gains the impression that the archaeological conclusions have been influenced or even biased by the desire to deconstruct the traditional view and replace it by an alternative one. Let us examine this particular issue in greater detail.

The time frame under discussion is secured by two chronological anchors: the earlier is the end of the Egyptian presence in Canaan during the twelfth century B.C.E. and the later is related to the Assyrian conquests of Israel, Philistia, and Judah between 732 and 701 B.C.E. Between these two anchors, which are four-hundred years apart, we have very few reference points. One such point is the site of Jezreel, where excavations carried out during the 1990s revealed the royal enclosure of Ahab and Jezebel well known from 1 Kings. This immense enclosure was destroyed during the late-ninth century B.C.E. , probably by Hazael, king of Damascus, soon after the end of the Omride dynasty in ca. 840/830 B.C.E. The pottery from this destruction layer must thus be dated to that time. It soon became clear that this pottery resembled the pottery found at nearby Megiddo in buildings traditionally attributed to Solomon. This is one of Finkelstein’s major arguments in favor of his lowering the date of the Megiddo buildings to the ninth century (see above p. 114). However, similar pottery was found at Jezreel also in construction fills below the foundations of the royal enclosure, probably associated with an earlier town or village. Such a pre-Omride occupation could date to the tenth or early-ninth century B.C.E. This suggests that throughout much of the tenth and ninth centuries, the same pottery repertoire was in use. Reflecting back on the buildings at Megiddo, we can conclude that they were constructed during, and remained in use throughout, the time frame represented by this particular pottery (designated as Iron IIA in the most common current division of the Iron Age), that is, either the tenth or the ninth centuries, or both (see further below). These buildings thus could have been built either by Solomon or by Omri or Ahab.

A second important chronological reference point is Arad in the northern Negev. This site appears in the list of place-names in the land of Israel that was inscribed on a wall of the Temple of Amun at Karnak in Upper Egypt during the reign of Sheshonq I, the pharaoh who conducted a military raid against Israel. Sheshonq I can safely be identified with the Shishak mentioned in 1 Kgs 14:25 as threatening Jerusalem in the time of Rehoboam five years after the death of Solomon. Since Arad is mentioned in Sheshonq’s list, there must have been a settlement there prior to Sheshonq’s invasion. Thus, at least the earliest settlement at Arad should be dated to the tenth century B.C.E. (or the time of Solomon). Excavations conducted in the earliest settlement (Stratum XII) by Yohanan Aharoni at Arad revealed pottery similar to that found in other occupation strata in Judah that traditionally has been attributed to the tenth century, such as that recovered from Beer-sheba or Lachish. Such a comparative relative chronology is a fundamental research tool in archaeology, and, as in the case at hand, it negates Finkelstein’s Low Chronology, according to which all these other sites should postdate the tenth century, and thus are later than the Solomonic era. Yet, somewhat surprisingly, Finkelstein himself accepts the dating of Arad Stratum XII to the time period prior to Sheshonq, and by doing so he pulls the rug out from underneath his own theory.

Meticulous research substantiates a series of correlations between many sites throughout the country, thus enabling us to use Arad as a key reference point and to create horizons of contemporary occupation strata elsewhere. Such an approach indicates in my view that Finkelstein’s Low Chronology cannot be accepted as is, since it creates unresolved problems in the study of the Iron Age. The archaeological research at Hazor, Jezreel, and at my own Tel Rehov excavations in the Beth-shean Valley (fig. 4 ) convinces me that indeed we have to modify somewhat our conventional chronology. But, unlike Finkelstein, who simply moves all the tenth-century assemblages to the ninth century, I propose that the pottery assemblage under consideration had a long life span and that it overlapped both the tenth and ninth centuries B.C.E. According to what I term the Modified Conventional Chronology (MCC), the Iron IIA lasted approximately from 980 to 840/830 B.C.E. (fig. 5 ).

During the last decade, a good number of archaeologists who excavate or study Iron Age IIA sites have adopted this “long duration” perspective for the pottery assemblage in question as the most acceptable one, including the excavators and researchers of Hazor, Jezreel, Beth-shean, Tel Rehov, Gezer, Beth-shemesh, Timnah (Tel Batash), Jerusalem, Gath (Tell es-Sâfi), Arad, and Beer-sheba. Currently, there are attempts to divide the Iron IIA period into two subphases, an earlier one in the tenth century and a later one starting at the end of the tenth century and continuing into the ninth century B.C.E. Some confirmation of this proposal has been tested at both Tel Rehov in the north and the Beer-sheba-Arad region in the south (the latter by Zeev Herzog and Lili Singer-Avitz).

Attempts to use 14 C dates to resolve the debate over Iron Age chronology have been made in the last decade in several research frameworks. More than sixty samples from Tel Rehov dated at the Groningen University laboratories by J. Van der Plicht and H. Bruins provide a sequence of dates for a series of strata from the twelfth to the ninth centuries B.C.E. The Early Iron Age Dating Project directed by E. Boaretto, A. Gilboa, I. Sharon, and T. Jull, utilizing the laboratories of the Weizmann Institute in Israel and the University of Arizona, intends to sample as many sites as possible; more than fifty dates stemming from this project have been published so far. Additional dates from various sites have been measured in recent years. The emphasis in these current projects is on high-quality dating of as many short-life samples (for example, seeds and olive stones) as possible from secure contexts, calibration with updated software, and statistical processing of the results. The major question is, what is the material culture related to the time frame attributed to David and Solomon in traditional historical reconstructions, namely, the bulk of the tenth century B.C.E.? Traditionally, this period would be included in the Iron Age IIA. The Low Chronology as suggested by Finkelstein would move the Iron Age IIA to the ninth century, and include the tenth century in the Iron Age I. Analysis of sixty-four 14 C dates from Tel Rehov point to a date between 992 and 962 B.C.E. for the transition from Iron I to Iron II; thus, the Iron IIA would cover much of the tenth as well as much of the ninth centuries B.C.E. The early results of the Early Iron Age Dating Project (published by E. Boaretto et al. in the journal Radiocarbon in 2005), which pointed to ca. 900 B.C.E. as the date of the end of the Iron Age I period and thus supporting the Low Chronology, have been checked more recently in an as-yet-unpublished study by myself together with Ch. Bronk Ramsey in light of several additional dates. The results point to a transition date from Iron I to Iron II between 964 and 944 B.C.E. We also calculated the destruction of three major sites related to the end of Iron Age I (Megiddo, Yoqne‘am, and Tell Qasile) as occurring around the end of the eleventh or beginning of the tenth century B.C.E. Thus, the transition from Iron I to Iron IIA occurred most probably somewhere during the first half of the tenth century B.C.E. , allowing sufficient time in the tenth century B.C.E. for the Iron Age IIA to be correlated with the Davidic/Solomonic era. Yet, the study has also shown how sensitive statistical models of 14 C dates are. New published dates or elimination of published dates for certain reasons (such as outliers, wood samples that are much too old, and questionable contexts or dates), may change the results substantially.

The outcome of the Modified Conventional Chronology is that both the United Monarchy and the Omride dynasty are included in a single, more lengthy archaeological period, denoted Iron IIA. This revised periodization in turn creates a greater flexibility in the interpretation of the archaeological data, and makes life more difficult for those who wish to utilize archaeology for secure historical interpretations in the southern Levant during the tenth and ninth centuries B.C.E. Since in many cases it would be difficult to conclude with any certainty whether a specific building was constructed either during the tenth or the ninth century, unless the subtle ceramic divisions between Early Iron IIA and Late Iron IIA will one day prove to be valid and utilized in a more controlled manner. This cannot be done at the present time for many of the older excavations, and in particular at Megiddo, since, out of the two palaces attributed by Yadin to the time of Solomon, the southern one was preserved to the level of the foundation courses only, while, from the northern one, the published pottery does not allow such a subtle dating inside the boundaries of the Iron IIA period. The modified chronology would mean that any comprehensive archaeological synthesis of the Solomonic period is tentative and may be interpreted in more than one way. And finally, it rejects the strict and one-sided Low Chronology as suggested by Finkelstein. In what follows, I will examine a few of the more crucial issues relating to our subject in the light of this Modified Conventional Chronology (MCC).

THE IMPORTANCE OF THE SHESHONQ I (SHISHAK ) RAID

The lack of external sources relating to a kingdom like that of David and Solomon should not surprise us, since there were no empires or major political powers during the tenth century B.C.E. that could leave behind substantial written documents. The only external source relating to this period is the Sheshonq I inscription mentioned above, which refers to a military raid against the land of Israel that took place in about 920 B.C.E. First, we must realize that the mention of Sheshonq’s campaign in 1 Kgs 14:25–28 cannot be explained away as an invention of an author of the seventh-century B.C.E. or later since the writer must have had records of some sort. This by itself is important evidence regarding the historical dimension of the biblical narrative and the way it emerged.

Unlike any of the earlier Egyptian New Kingdom military campaigns in Canaan, Sheshonq’s list mentions sites north of Jerusalem, like Beth Horon and Gibeon. The only plausible explanation for this must be the existence of a political power in the central hill country that was significant enough in the eyes of the Egyptians to justify such an exceptional route for the campaign. The only sensible candidate for such a power is the Solomonic kingdom. Finkelstein’s proposal that it was Saul’s kingdom that was Sheshonq’s target seems to be farfetched (see below, p. 148 ) and in contrast to any biblical inner chronology, which dates Sheshonq’s raid to the reign of Rehoboam. If indeed the raid followed Solomon’s death, perhaps Sheshonq was trying to take advantage of a time of weakness and strike a blow against the emerging Israelite state. The fact that Jerusalem is not mentioned in the inscription does not mean much—if the city surrendered, perhaps there would have been no reason to mention it; or alternatively, its mention could have appeared on one of the broken parts of the inscription.

As to the remaining stages of the route, most scholars (except Nadav Na‘aman) reconstruct a route that crossed the central mountain ridge towards the Jordan Valley. The references in the inscription to Rehov, Beth-shean, and “The Valley” (probably referring to the Beth-shean or Jezreel Valleys or both) in a continuous line fits this reconstruction.

There are various views concerning the question of whether or not Sheshonq actually destroyed the cities along his route, and if so, which archaeological levels can be identified as those he destroyed. The commonly held view is that such destructions indeed occurred, and that it is possible to identify destruction layers that resulted directly from this military campaign. Violent destructions that can be dated to this time, and which may have been the result of this raid, were tentatively identified at a number of sites, in particular in the Beth-shean and Jezreel Valleys, such as Tell el Hama, Tel Rehov, Megiddo, and Taanach. In my view, however, the question of whether cities were indeed destroyed is less important than the very mention of certain names in the list. It is not conceivable, as some scholars have suggested, that Sheshonq’s scribes merely copied names from earlier Egyptian topographic lists at Karnak, since there are many place-names known only from Sheshonq’s inscription. For archaeologists, it is important to recognize that any place-name that appears in this list must have been in existence before the raid and that where possible, it should therefore be identified in the archaeological record; Arad, the Negev highland sites, Taanach, and Rehov are all good examples of sites that are mentioned in the Sheshonq inscription and that yielded Iron IIA occupation layers. In some of these (for example, Arad and the Negev highlands, for which see below) there is no alternative but to attribute the Iron IIA occupation layers to the tenth century B.C.E. , preceding Sheshonq’s raid. This is an important chronological anchor, one that negates the Low Chronology.

JERUSALEM OF THE IRON I—II PERIOD

The evaluation of Jerusalem as a city in the tenth to ninth centuries is crucial for defining state formation in Judah—if there was no capital, there likely was no kingdom. In several papers published in recent years, David Ussishkin has proposed that Jerusalem was not settled in the tenth century, while Finkelstein has defined Jerusalem of the tenth century as a small village. These assessments should be examined in some detail since they are crucial for our subject.

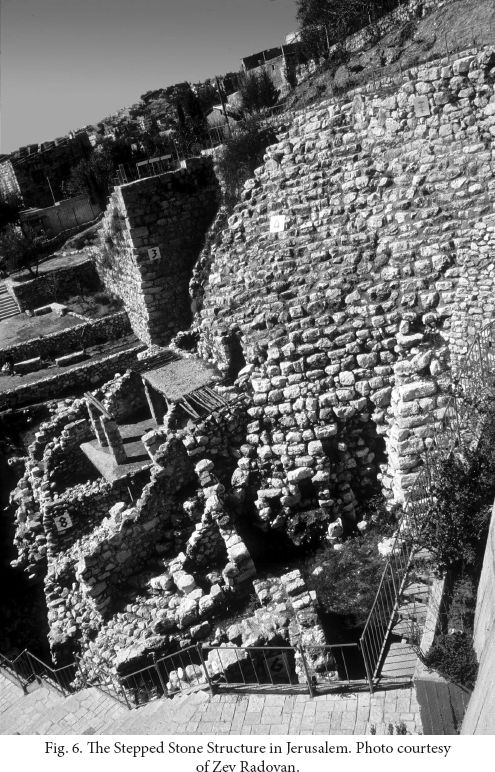

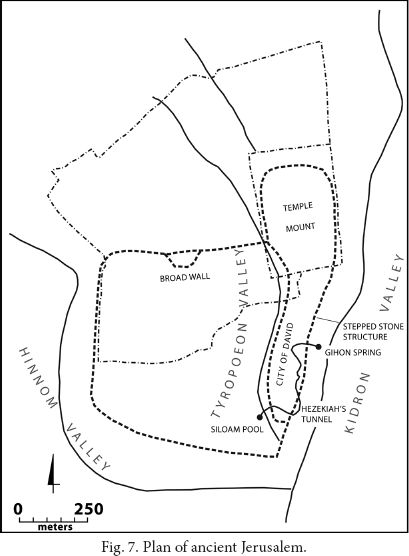

Prior to its expansion in the eighth century B.C.E. towards the Western Hill, Jerusalem was limited to the narrow ridge of the Eastern Hill, crowned by the Temple Mount. The area of this entire ridge is about twelve hectares (ca. thirty acres), a large area for any Iron Age city in Israel or Judah. The entire upper part of this hill is located below the huge artificial platform from the Second Temple period. South of the Temple Mount, the ridge becomes narrower, surrounded by the deep ravines of the Kidron and Tyropoeon Valleys. This was the location of early Jerusalem, the original Canaanite city. The area of this part of the ridge is about four hectares. A main structure uncovered near the summit of this part of the hill known as the Stepped Stone Structure is enormous and was most probably intended to support an exceptionally large monumental building (fig. 6 ). The earliest possible date of its construction can be deduced from pottery found within its foundations, which dates no later than the twelfth to eleventh centuries B.C.E. Pottery found on the floors of structures above the lower part of this stepped structure indicate that it started to go out of use during the Iron IIA, that is, some time in the tenth or ninth century. Therefore, the Stepped Stone Structure must have been constructed between the twelfth and tenth centuries B.C.E. It is thus legitimate to conclude that the building was either constructed or continued to be in use during the tenth century, the alleged time of David and Solomon (cf. below, p. 151 ).

Excavations carried out recently by Eilat Mazar on the summit of the hill to the west and very close to Stepped Stone Structure have revealed a monumental building with walls over two meters wide, which extends beyond the limits of the excavation area in all directions. A continuation of the same building was excavated by Kathleen Kenyon (in her Area H) and identified by her as a “casemate” structure dating to the tenth century B.C.E. The data relating to the date of this building are very similar to that of the Stepped Stone Structure. Its foundation rests upon, and is abutted by, an earth layer containing twelfth to eleventh century pottery, and tenth to ninth century pottery was found in an earth layer relating to some of its walls, where evidence for repairs and changes to the building have been detected. This building appears to be the anticipated monumental building or citadel that was supported by the Stepped Stone Structure. In terms of their magnitude, neither the Stepped Stone Structure nor the building recently discovered to its west has a parallel anywhere in the land of Israel between the twelfth and early-ninth centuries B.C.E. , and this is, in my view, a clear indication that Jerusalem was much more than a small village; in fact it contained the largest-known structure of the time in the region and thus could easily serve as a power base for a central authority. Eilat Mazar suggested identifying this building with the palace attributed to David in 2 Sam 5:11. A more plausible identification in my view would be with Metsudat Zion—“the fortress of Zion”—mentioned in the biblical description of David’s conquest of Jerusalem. David is said to have changed the name of this citadel to ‘ir dawid , or “the City of David” (2 Sam 5:7, 9). Such identification remains, of course, hypothetical, yet it might appeal to those who believe that the biblical narrative did preserve many ancient traditions and some knowledge of the past.

In addition to this huge building, only a few remains were found in the City of David that can be attributed to the tenth century. These are mainly pottery sherds found in all the excavation areas, and only a few architectural remains. The latter situation is probably the result of the bad state of preservation of structures on the steep slope at this peculiar site, and of the continuous reuse of buildings over the centuries. Massive fortifications discovered by Ronni Reich and Eli Shukron around the Gihon spring at the foot of the City of David have been dated to the Middle Bronze period (eighteenth to sixteenth centuries B.C.E.) , and were among the mightiest fortifications from this period in the entire country. Such immense fortifications could have continued to be used for centuries, including into the time of David and Solomon, though there is no direct proof to support this proposal, and it remains a circumstantial argument only. But compare, for example, the situation at other major cities of the ancient Near East where Middle Bronze monumental structures continued to be in use for many centuries, sometime well into the Iron Age (such as the palace in the city of Assur, the temple of the storm god at Aleppo, the temples at Shechem and Pella, and more).

The temple and palace that Solomon supposedly built should be found, if anywhere, below the present Temple Mount, where no excavations are possible (fig. 7 ). If the biblical account is taken as reliable, Solomon’s Jerusalem would be a city of twelve hectares with monumental buildings and a temple. Should Solomon be removed from history, who then would have been responsible for the construction of the Jerusalem Temple? There is no doubt that such a temple stood on the Temple Mount prior to the Babylonian conquest of the city, but we lack any textual hint for an alternative to Solomon as its builder.

Solomon’s temple, as described in the Bible, was built according to a tripartite plan well known in the region from the second millennium B.C.E. to the eighth century B.C.E. Close parallels are known from the Iron Age temples at Tell Tayinat and ‘ Ain Dara in northern Syria. They provide examples of architectural details that appear in the description of Solomon’s temple, such as the two pillars at the front of the main entrance (biblical Yachin and Boas), the corridors surrounding the building, and the special type of windows. The details of construction in the biblical tradition, such as the use of large hewn stones combined with cedar wood, also fit building techniques known in the second millennium and the Iron Age. Such temple plans are unknown after the eighth century B.C.E. in the Levant and, thus, the biblical description of the Jerusalem’s temple could not have been an invention of the seventh century or later.

The decoration of the temple and its furnishings, like the molten sea, the gourds, the wheeled stands of bronze, the cherubim, the shovels, and the basins, all have parallels in archaeological finds. The decorations fit artistic motifs that are known in Phoenician art. Most of the parallels come from objects dated to the ninth to eighth centuries, but many of them are rooted in second-millennium traditions, and are evidence for the continuity in cultural traditions between the second and first millennia. Solomon’s temple could signify this same continuity. The main detail that seems exaggerated is the huge amount of gold in the structure—it seems unlikely that such a large quantity of gold was available in Jerusalem, though Allan Millard has argued for the feasibility of this detail as well.

The description of Solomon’s palace compound and its various components can be compared to palace architecture in the Levant and northern Syria. Such a comparison indicates close similarities to well-known palace compounds such as those at Zinjirli, the capital of Sam‘al (in southeastern Turkey) and other Syrian cities. It thus appears that the biblical descriptions of both the temple and the palace fit the architecture and decorative arts of the Iron Age as known to us from archaeology.

Yet, is it feasible that such splendid structures stood in tenth-century Jerusalem? One may doubt that Solomon’s kingdom was strong and rich enough to afford such buildings and furnishings. It may well be that the biblical description is based on the shape of the Temple at the time of writing—the eighth to seventh centuries, when Jerusalem was at its peak—and even then it seems to be much exaggerated. Such an explanation, however, does not exclude the possibility that the temple and palace were indeed established during the tenth century, and later renovated.

In summary, Jerusalem during the time of David was most likely a city of about four hectares, which could have reached an area of twelve hectares during the reign of Solomon. At the summit of the core city (the “City of David”) stood a large citadel, the nature and dimensions of which are exceptional for this period. Such a city cannot be imagined as a capital of a large state like the one described in the Bible, but it could well serve as a power base for local rulers like David and Solomon, providing that we correctly define the nature of their kingship and state.

YADIN’S PARADIGM : MEGIDDO , HAZOR , AND GEZER

In the early 1930s, the excavators at Megiddo from The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago uncovered in their Stratum IV, huge compounds or structures that were interpreted by them as royal stables. They identified these as Solomonic projects following the references in the Bible to chariot cities constructed by Solomon (1 Kgs 9:19). In an earlier level, Stratum V, the Chicago excavators, as well as Yigael Yadin of the Hebrew University, revealed an unfortified city with two palaces constructed of ashlar stones (today, this city is usually denoted as Stratum IVB–VA). The history and dates of these two cities became the subject of a longstanding debate among archaeologists and it remains an unresolved issue, although crucial for our subject. One major question relating to Megiddo is the date of the so-called six-chambered gate; a city gate constructed of ashlar stones that definitely was in use during the time of the “chariot city,” but according to several scholars was already established in the earlier “palaces city” (or Stratum IVB-VA). William F. Albright, Yadin, and others dated the “palaces city” to the time of Solomon and the “stables city” (Stratum IVA) to the time of Ahab in the ninth century.

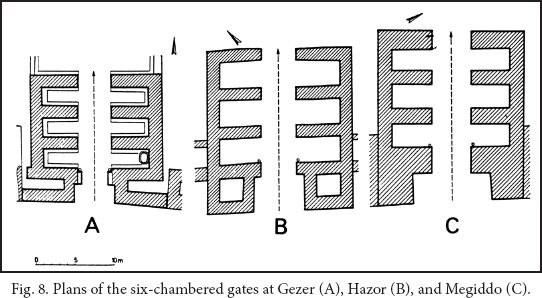

Following his excavations at Hazor and Megiddo in the 1960s, Yadin developed his renowned thesis concerning Solomonic architecture. At Hazor he discovered a six-chambered gate similar to that of Megiddo, and at Gezer he identified a similar gate that was partly excavated by Stuart Macalister many years earlier. Based on the mention of Hazor, Megiddo, and Gezer among Solomon’s building activities in 1 Kgs 9:15, Yadin suggested that all three gates were constructed by Solomon’s architects according to a similar “blue print” (fig. 8 ). Thus, these gates and the cities to which they belonged were considered by him to be markers of Solomon’s kingdom. Later excavators at both Hazor and Gezer appeared to confirm the tenth-century dates of these gates. At Hazor, the gate was found in the earliest of at least six Iron Age strata preceding the Assyrian conquest of 732 B.C.E.; three of these strata (X, IX, and VIII; the two early ones have subphases) are from the tenth to ninth centuries B.C.E. , with Stratum VIII probably ending no later that ca. 830 B.C.E. The six-chambered gate and the casemate wall belong to the earliest of these strata, and thus it makes sense that this fortification system was constructed during the tenth century B.C.E.

Yadin’s view concerning Megiddo was criticized in light of indicators that the six-chambered gate could not have been constructed earlier than the “stables city” and the latter must be later than Solomon according to Yadin himself. In my view, the gate could have been part of the palaces city (Stratum IB-VA) and continued in use into the ninth century. A more radical view is that of Israel Finkelstein, who has suggested that the entire “palaces city” (Stratum IVB-VA) was constructed by Ahab, and the “stables city” (including the six-chambered gate) was built by Manasseh in the eighth century B.C.E. This continues to be a debated issue, and there are diverse views even among the three directors of the current excavations at Megiddo (Israel Finkelstein, David Ussishkin, and Baruch Halpern). As mentioned above, the Modified Conventional Chronology enables one to date the pottery found in the “palaces city” to either the time of Solomon or to the time of Ahab. This situation demonstrates the variety of possibilities in the interpretation of archaeological data for historical reconstruction. I still hold to the notion that the tenth-century date of the “palaces city” is the correct one, though it would be difficult to provide final proof for that. The “palaces city,” though it might have had a monumental gate, lacked a city wall and it would be hard to accept the notion, as suggested by Finkelstein’s Low Chronology, that Ahab’s Megiddo was an unfortified city, since this warrior king had huge fortifications at his nearby royal enclosure in Jezreel, as well as at other cities of his kingdom. The stables of Megiddo would fit the time of Ahab who is mentioned in the Assyrian sources as the owner of a huge number of war chariots. To sum up, Yadin’s thesis concerning Solomonic architecture at Megiddo, Hazor, and Gezer might be correct.

THE JUDEAN SHEPHELAH

Several other excavated sites throughout the Israelite territories point to a process of urbanization during the tenth century B.C.E. This would be the first stage in an urban development that continued in most of these cities without interruption until the Assyrian conquests in the late-eighth century B.C.E. It should be mentioned though that many of the sites remained unfortified and were not sufficiently developed to qualify as urban centers during the tenth century. The new style would continue to survive through most of the tenth and ninth centuries, thus making it difficult to differentiate between these two centuries, and this complicates matters in regard to historical interpretation.

The case of Lachish, Judah’s second-most-important city, is a good example of the chronological dilemma. After a long occupation gap beginning in the twelfth century B.C.E. , a new unfortified town (Stratum V) was established during the tenth century (according to the conventional chronology) or the ninth century (according to the Low Chronology adopted by Ussishkin, the excavator). The first phase of a monumental palace located at the center of the mound was perhaps established at this time (as suggested by the British excavators and by Ussishkin during his excavations) or only in the later city (Stratum IV; as maintained by Ussishkin in the final publication). An accurate date for this building is important for historical reconstruction. If the palace were to be dated to the tenth century, it would accord well with the archaeological situation in Jerusalem as described above, and could serve as evidence for the emergence of Judah as a state in the tenth century. Yet, the answer is not definitive and we find ourselves in the same quandary of being subjected to preconceived historical paradigms when making a choice between the two alternative interpretations of the archaeological data.

Lachish is included in the list of Rehoboam’s fortified cities (2 Chr 11:8). His fortification of Lachish may be identified with that of Stratum IV, which included a massive city wall and a six-chambered gate similar to the ones mentioned above. The problem is that the date of this biblical list is debated: several scholars claim that it was created in a much later period and should not be considered historical. Yet, this remains an unresolved question. Although the list is included in the less historically reliable book of Chronicles, this book may retain authentic traditions and citations from ancient documents.

In the northern Shephelah, along the Sorek Valley, the cities of Bethshemesh and Timnah (Tel Batash) were built in the tenth century, perhaps within the framework of the emerging Israelite United Monarchy. Two short Hebrew inscriptions, one found at each of these sites in tenth-century contexts, preserve the name Hanan, which can be related to Elon Beth Hanan, a place-name mentioned in Solomon’s second administrative district, right in this region (1 Kgs 4:9). This seems to be more than mere coincidence. Perhaps the family of Hanan settled this region, and the name was preserved in both inscriptions and in the biblical name. In this case, the tenth-century date of the inscriptions may support the authenticity of the biblical list of Solomon’s districts.

THE NEGEV

The Negev highlands are a hilly region bounded by the oasis of Kadeshbarnea on the southwest. The region was not settled during the second millennium B.C.E. , but, rather abruptly, about fifty massive, well-planned buildings (so-called fortresses) and about five-hundred scattered houses were constructed in this region during the tenth century B.C.E. They survived for only a short time and then were destroyed and abandoned. The well-planned fortified structures and four-room houses built according to a typical architectural plan and building technique, as well as about half of the pottery found in these sites, could not be of local nomadic origin, as suggested by a number of scholars. They must indicate influence from, and connections with, settled regions further north, be it the northern Negev, Judah, or the coastal plain. The more simple, scattered structures, as well as the other half of the pottery (rough and handmade “Negebite” pottery) can indeed be attributed to local pastoral, semi-nomadic populations. All this is probably evidence for a symbiosis between settlers who came from Judah or the southern coastal plain and local desert nomads. Various explanations have been offered for this phenomenon. In my view, it is the outgrowth of external influences, perhaps that of the emerging Israelite United Monarchy. The motivation was probably economic, perhaps related to the vast copper smelting industry that was established at the same time at Feinan east of the Arabah Valley (see below). In the middle of the Arabah Valley, opposite Feinan, the site of ‘Ein Hazevah might have been a trading post situated along one of the routes of such a trade network.

The Sheshonq list (see above) includes dozens of place-names in the Negev. Some of these appear to be common Hebrew names such as hgr abrm (Hagar Abraham) and hgr ard rbt (Hagar Arad Rabat). Hagar could have been the Hebrew term for the large structures surrounded by belts of rooms, which are common in the Negev highlands. It is thus probable that Sheshonq destroyed this short and intensive settlement wave in the Negev highlands. This southern branch of his campaign was probably intended to put an end to the exceptional network of settlements and trade in the region, which perhaps was considered by the Egyptians as competing with or threatening their own economic interests. I reject Finkelstein’s suggestion that these Negev highland sites were part of a “chiefdom” centered at Tel Masos in the Arad-Beer-sheba Valley. The main occupation phase at Tel Masos appears to precede those Negev highlands sites and Tel Masos lacks Negebite handmade pottery, which is a major hallmark of these sites.

An excellent example of misinterpretation of an archaeological discovery is the case of the identification of Ezion-geber with Tell el-Kheleifeh (between Aqaba and Eilat). The Bible relates that Solomon carried out an active trade with Sheba and Ophir, apparently to be identified with southern Arabia and Somalia respectively (1 Kgs 9:26–28; 10:1–13). Ezion-geber, the port of call for this trade, was identified by Nelson Glueck in 1937 with Tell el-Kheleifeh, at the head of the Red Sea. He described a large building that he uncovered there as a smelting center for copper ores brought from the Timna‘ mines, about thirty kilometers to the north. Nelson Glueck’s proposals became widely publicized due to his popular books and reputation. However, more intense research at Timna‘ and a reassessment of the finds many years later proved that the entire theory had no foundation. The Timna‘ mines were earlier than Solomon by some three-hundred years, and the Iron Age fortified settlement at Tell el-Kheleifeh was probably established long after Solomon’s time (though this is not secure, since pottery recovered by Glueck in the earliest level there was neither published nor preserved).

DEMOGRAPHY

One of the arguments against the historical reality of the United Monarchy is the supposed low settlement density and lack of urbanization in the tenth century. Yet, studies of settlement density and ancient demography are strewn with methodological problems, as they rely on the interpretation of surface surveys. It is difficult to assess the results of such surveys at sites that were settled continuously for most of the Iron Age. The pottery collected would come from the last occupational phases of these sites, and only meticulous excavation could detail their full occupational history. Thus, the history and extent of such sites remain enigmatic, and calculations of population based on such studies are to be used with caution. A comparison of the settlement pattern in the Iron I to that of the eighth century B.C.E. points to a gradual increase in settlement over this time span of about five hundred years. An average estimation of approximately twenty thousand people in Judah during the tenth century appears to be realistic. If we add to this the unknown population numbers in the Israelite territories of northern Israel and parts of Transjordan, we may estimate the population in the Israelite territories at somewhere between fifty and seventy thousand people. Such a population may be considered sufficient as a demographic base for an Israelite state in the tenth century.

LITERACY

Another argument against the existence of the United Monarchy is the dearth of inscriptions dating to the tenth century B.C.E. This may mean a lack of literacy and thus the improbable existence of a central administration and, consequently, a state. However, the Northern Kingdom of Israel, the existence of which is undisputed in the ninth century B.C.E. , certainly has not yielded a large number of ninth-century inscriptions either! It might be assumed that the dearth of inscriptions from both these centuries is due to the wide use of perishable materials like parchment or papyrus for writing. The few inscriptions incised on stones or pottery vessels for daily use from a tenth century context hint at the spread of literacy already in this time, and thus it can be assumed that some officials and professional scribes did exist in the tenth century.

ISRAEL’S NEIGHBORS IN THE TENTH CENTURY

In the biblical narrative relating to David and Solomon, Israel’s neighbors play an important part. We read about the Philistines, the Ammonites, the Edomites, the Arameans and the city of Tyre. To what extent does archaeology throw light on these various geo-political units? The last three decades of archaeological research were revolutionary concerning some of them, while others remain largely unknown. The following is a short summary of the evidence and of several debated questions.

THE PHILISTINES

The Bible excludes Philistia from the territory of David’s conquests, and this fits the archaeological situation in Philistia, where the independent cities continued to thrive. However, current research has indicated an interesting shift in the balance between the main Philistine cities. During the preceding Iron Age I, Ekron (Tel Miqne), located inland and close to the border of the Shephelah, was one of the largest Philistine cities, with an area of about twenty hectares. Gath (Tell es-Sâfi) to the south of Ekron, was possibly also a very large city of about twenty to thirty hectares. Yet, during the tenth century, Ekron diminished to an area of only four hectares, while coastal Ashdod increased its settled area from about eight hectares to about forty hectares. Gath maintained its size. One possible explanation for the shifts is pressure from the east by the emerging kingdom of David and Solomon. This may have affected Ekron, which perhaps lost much of its hinterland south of the Sorek Valley, and many of its people had to move to Gath or Ashdod, perhaps contributing to the expansion of the latter.

EDOMITES , MOABITES , AMMONITES

Our information on the tenth-century states of Transjordan is limited. Recent research has brought new data and raised new questions concerning the emergence of Edom. Excavations conducted by Thomas Levy at Khirbet en-Nahas, the main Iron Age site in the vast copper mines of Feinan, east of the Arabah Valley at the foot of the Edom mountains, have revealed intensive copper-ore mining and smelting industry. A large fortress, several massive structures, and huge piles of copper-production slags belong to several activity phases, dated by radiometric dates and various finds to a time span between the eleventh and the ninth centuries B.C.E. This well-organized and vast copper industry was certainly of immense economic importance and must have been maintained by a central authority. It also must have been related to an extensive trade system, in which the sites in the Negev highlands, the regions of Arad, Beer-sheba, and perhaps the coastal cities of Philistia and Phoenicia took part. Who were the operators of this large-scale production center? The early Edomites are the natural candidates. Yet, the traditional view, based on the finds in the Edomite highland sites, was that Edom did not emerge as a state before the eighth-seventh centuries. Excavations at Bosrah (Buseirah), the capital of Edom, located to the east of Feinan, revealed monumental architecture that is no earlier than the eighth to seventh centuries B.C.E. The new finds at Feinan call for a reassessment of the history of Edom. It might be, as Levy argues, that the Edomite state at least emerged during the tenth century B.C.E. The Feinan mines were perhaps operated by a central authority that must have been in nearby Edom; perhaps future excavations at Bosrah will reveal earlier occupation periods there. The subject is currently under debate, and specialists in Edomite archaeology like Piotr Bienkowski have rejected Levy’s hypothesis. Yet, the new evidence appears to be strong and convincing. The Feinan copper mines must have been well known during the tenth century B.C.E. , and this might be the background for the mentioning of Edom in the biblical narrative in relation to the United Monarchy.

We have already mentioned the possible emergence of Moab in the twelfth to eleventh centuries, yet no direct finds related to the tenth century are known in either Moab or Ammon. David’s wars against the Ammonites thus cannot be corroborated. This may change in the future, if and when systematic excavations can be carried out on the mound of Rabbath Ammon (at the center of modern Amman) and related sites.

TYRE AND THE PHOENICIANS

The Bible often mentions relations between Hiram, king of Tyre, and Solomon. Tyre belongs to what was at the time an emerging new entity, which we call today (following the Greek term) “Phoenicia.” Not much is known about the major Phoenician cities Tyre and Sidon as they have not sufficiently been undertaken, yet specific pottery styles can be related to the Phoenician cities of the tenth century B.C.E. Greek Euboean pottery found in probes conducted at Tyre indicates international trade relations in which Tyre was involved already during the tenth century B.C.E.

The sarcophagus of Ahiram, king of Byblos, preserves both a royal burial inscription, as well as a finely executed bas relief. It has been considered a hallmark of Phoenician art and evidence for the flourishing of Phoenicia during the tenth century B.C.E. A recent attempt by Benjamin Sass to lower the date of this monument to the ninth century is inspired by the Low Chronology and is highly questionable in my view.

Coastal sites in northern Israel, such as Dor and Achziv, have revealed several stages in the emergence of the Phoenician culture, from the end of the eleventh century B.C.E. onwards. Horvat Rosh Zayit in the western Galilee is of special interest. It seems to have been a trading post between Tyre and northern Israel during the late-tenth and early-ninth centuries B.C.E. Its location close to the modern village of Cabul led the excavator Zvi Gal to suggest its identification with biblical Cabul mentioned in the story about the land of Cabul that Solomon delivered to Tyre (1 Kgs 9:10–13). This story perhaps stems from the political and economic relations between Tyre and the Israelites at that time.

Phoenician pottery and other artifacts found at Israelite sites of the tenth century are evidence for trade relations between Tyre and Israel. Though most of these finds come from northern Israel, some evidence from Jerusalem and other southern sites indicates relations between Phoenicia and Judah already in the tenth century B.C.E. , although admittedly these are indeed few and of small scale.

ARAMEANS AND NEO -HITTITES

Due to the paucity of archaeological data from southern Syria, we lack direct archaeological evidence for the emergence of the Aramean states of Damascus and Aram-Zobah mentioned in the biblical narratives concerned with David’s wars in Syria. It is highly questionable whether David indeed ever conducted wars in Syria and whether Toi, king of Hamath, was actually an historical figure and ally of David, as described in the biblical narrative. Yet, it is interesting to recall a rather recent archaeological discovery: the main temple of the storm god at Aleppo in northern Syria was recently excavated and found to contain monumental reliefs in Neo-Hittite style, dated tentatively to the eleventh century B.C.E. , while the temple itself continued to be in use until the ninth century B.C.E. An inscription found in the temple identifies a king named Tauta whose kingdom encompassed a vast territory in northern Syria, including Hamath, where another inscription mentioning the same king was found. The name Tauta is of non-Semitic origin and might be echoed in the biblical name Toi, and thus this new discovery could shed light on the origin of the biblical traditions relating to Toi, king of Hamath. We cannot judge whether David’s relations with Hamath actually occurred or not, but we can claim that the biblical story may have been based on the actual existence of a large tenth-century kingdom in northern Syria.

Archaeology has managed to shed some light on the small Aramean kingdom of Geshur mentioned several times in the biography of David. This kingdom existed to the northeast and east of the lake of Galilee, where two sites have been excavated, namely, Tel Hadar and Bethsaida. Tel Hadar was an administrative center with a large granary and a storehouse and has been dated by both conventional research as well as recently published radiometric dates to the eleventh or early-tenth century, the supposed time of David. Bethsaida, an eight-hectare city, was fortified during the tenth century B.C.E. by massive fortifications. Though Geshur was the smallest Aramean state, its fortifications and public structures are evidence for a strong central authority and economic power from the eleventh century B.C.E. down to the Assyrian conquest of the mid-eighth century. Here again, the archaeological evidence provides an early backdrop to the biblical narrative.

CONCLUSIONS

To be sure, much of the biblical narrative concerning David and Solomon can be read as mere fiction and embellishment written by later authors. The stories of David’s conquests in Transjordan and Syria, Solomon’s wisdom, the visit of the Queen of Sheba, the magnitude and opulence of Solomon’s buildings, and so on, should not be read as historical accounts. Nonetheless, the total deconstruction of the United Monarchy as suggested by some current authors is, in my view, unacceptable

In evaluating the historicity of the United Monarchy, one should bear in mind that historical development is not linear, and history cannot be written on the basis of socio-economic or environmental-ecological determinism alone, as was common during the processual phase that dominated historical studies and archaeology in the 1970s and 1980s. The role of the individual personality in history should be taken into account, particularly when dealing with figures like David and Solomon. Such an approach has received renewed legitimacy in post-modernist thinking. It enables one to assume that leaders with exceptional charisma and personal ability could have created short-lived political entities or states with significant military power and territorial expansion. I would compare the potential achievements of David to those of an earlier hill country leader, namely, Labayu, the Amarna Age Apiru leader from Shechem who managed during the fourteenth century to rule a vast territory of the central hill country, and threatened cities like Megiddo in the north and Gezer in the south. All this he achieved in spite of Egyptian domination of Canaan. David can be envisioned as a ruler similar to Labayu, except that he operated in a time free of intervention by the Egyptians or any other foreign power, and when the Canaanite cities were in decline. A talented, charismatic, and politically astute leader in control of a small yet effective military power could, in my view, have taken hold of a large part of a small country like the land of Israel and united diverse population groups under his leadership. These groups may have been descendants of the local Canaanite populations and/or tribal groups in the hill country and the Negev. The only powers that stood in David’s way were the Philistine city-states, which, as both the Bible and archaeology inform us, were large, fortified, and independent urban centers during this time, and which indeed engaged David both militarily and politically.

While short-lived political and territorial achievements like those of David may be beyond the capability of the tools of archaeology to detect, the great changes that took place in the material culture during the tenth century may have been the result of these new ethnic, social, and political alliances and configurations. This new material culture is emblematic of the beginning of a new era that reached its zenith in the ninth and eighth centuries.

The United Monarchy can be described as a state in an early stage of development, far from the rich and widely expanding state portrayed in the biblical narrative. Its capital during the time of David can be compared to a medieval burg surrounded by a medium-sized town, yet it might well have been the center of a significant regional polity that included most of Cisjordan. Sheshonq’s invasion of the Jerusalem area probably came as a reaction to the growing significance of this state, and his list of conquered towns and territories at Karnak may reflect the major territories ruled by David and Solomon. The identification of Solomon’s buildings remains a debated issue, though the archaeological chronology that I utilize allows for the dating of the monumental structures to the tenth century. Therefore such buildings might have been Solomonic in origin.

The mention of bytdwd , or the “House of David,” as the name of the Judean kingdom in the Aramaic stele from Tel Dan, possibly erected by King Hazael of Damascus, indicates that approximately a century and a half after his reign, David was still recognized throughout the region as the founder of the dynasty that ruled Judah. His role in Israelite ideology and historiography is evidenced by his impact on later Judean collective memory, and cannot be explained as merely an invention of later authors.