Portrait Painter to the Elite

WILLIAM SMITH JEWETT

Janice T. Driesbach

LATE IN 1849 SAN FRANCISCO gained its first resident professional painter when William Smith Jewett arrived on 17 December. Like many Argonauts, Jewett had traveled with a mining company, which broke up shortly after their ship reached port. The adventurers’ arrival amidst heavy rains, which soaked the city to the extent that “everything . . . here looks as though it had been shaken into a complete jelly,” delayed their progress to the goldfields.1

Jewett had met with mixed success in his practice in the East,2 but within six weeks of his arrival in California he reported securing a number of commissions. Although he had surely expected to acquire wealth mining or in a related business venture, Jewett profited as a painter before he had an opportunity even to try his luck at mining. Most likely he discovered that his talents were in greater demand and offered him more substantial remuneration than they had in his native New York, where there was more competition for patrons. In letters, Jewett reported encountering many acquaintances from home, who “have all insisted so strongly upon my sitting up my easel right amongst all this crazy stuff that I have at last done so and am at work quite in earnest.”3 Interestingly, although Jewett’s correspondence makes it clear that throughout most of his long residency in San Francisco he envisioned returning home imminently, he did not exhibit his work in the East while he was in California.4 By January 1850, he was reporting enthusiastically about his reception:

Society has great hopes of me here and think I am a lucky fall to them, gentlemen desire their portraits to send home to their families and I am likely to be full of work I paint very rapid take them on the wing and all are profesighing [sic] a fracture to my hand.5

Not only was the artist quickly fulfilling orders, but also his talents caught the attention of California’s leading political figures. Jewett had requests from California’s governor and lieutenant governor, among others. Expecting that he could complete two or three portraits each week, for between  150 and

150 and  800 each, he declared himself “as jolly . . . as a clam at high water.”6 Financial transactions were conducted in hard currency. With the silver he received in return for a portrait, Jewett had to face the problem for “the first time in my life” of what to do with his money. “So I came home and got a large canvas bag I had used for common trapsticks went back and I shoveled it into it and lugged it home.” Likewise, he noted, costs were astronomical. Nonetheless, Jewett speculated that if business were pursued energetically, “a fortune can be made speedily.”7 He had already profited on a sale of real estate, the first of many such investments Jewett undertook during his twenty-year stay in California, and his detailed reports in letters home suggest that his business ventures were as important to him as the progress of his painting was.

800 each, he declared himself “as jolly . . . as a clam at high water.”6 Financial transactions were conducted in hard currency. With the silver he received in return for a portrait, Jewett had to face the problem for “the first time in my life” of what to do with his money. “So I came home and got a large canvas bag I had used for common trapsticks went back and I shoveled it into it and lugged it home.” Likewise, he noted, costs were astronomical. Nonetheless, Jewett speculated that if business were pursued energetically, “a fortune can be made speedily.”7 He had already profited on a sale of real estate, the first of many such investments Jewett undertook during his twenty-year stay in California, and his detailed reports in letters home suggest that his business ventures were as important to him as the progress of his painting was.

On 30 January 1850 Jewett announced he “made fifty dollars today in painting one little head at one sitting” and noted that “there are other artists here and doing comparably nothing some do not endeavor to paint at all, I somehow appear to be popular and don’t know why.”8 Among the projects he was offered was a panorama of California; despite the promise of a considerable sum of money, Jewett viewed the undertaking as “a most uncongenial task for my mind.”9 This response is somewhat surprising, given his professed interest in visiting the mining regions in coming months to make sketches. However, the vast scale of a panorama may have struck the artist as onerous; also—ever-conscious of his economic prospects—he noted that another artist was already engaged on a similar undertaking. In any case, his work was in sufficient demand that he could turn away commissions that did not appeal to him.10

Within two months, his talents were noted in the local press, with the Alta California declaring enthusiastically:

We have had quite a number of amateur painters visit our good city, some of whom could make a very pretty picture, without much regard to accuracy or a striking delineation of the faces and figures of their subjects. Now, however, we have an “artist as is an artist” here, who can paint a likeness of a person as well as a finished picture. We allude to Mr. Jewett from New York, who has his studio on Clay Street, where we yesterday saw the portraits of several of our first citizens, and it is with pleasure that we recommend him to the public.11

In adding that “any one desirous to send a portrait to the States can have it put in a tin case by Mr. J. in very compact form for transmission,” the Alta acknowledged the widespread interest in sending portraits to distant family members and friends.12

Among the projects Jewett undertook at this time was his portrait of the Grayson family, The Promised Land (fig. 33). Although it is uncertain how the artist met the Graysons, it is likely that they were introduced by mutual friends. Andrew Jackson Grayson and his wife had long intended their arrival in California four years earlier to be commemorated in a painting, and Jewett appears to have been commissioned in January 1850. The artist received both a substantial fee (two thousand dollars) and detailed instructions from the Graysons. They requested not only that Jewett visit the scene in person, but also, in an ambitious composition, include numerous themes and motifs, such as “success of pioneers; threatening mountains; smiling valley, three full-length portraits, Grayson in buckskin outfit Mrs. Grayson made for him; her own horse, saddle, utensils; the woodsman’s gun, and the forest.”13

FIG. 33. William Smith Jewett, The Promised Land—The Grayson Family, 1850. Oil on canvas, 50¾ × 64 in. Daniel J. Terra Collection, courtesy of Terra Museum of American Art, Chicago. 5.1994

Despite the incentive this commission offered, Jewett delayed venturing into the Sierra foothills to make sketches until after his lodgings in San Francisco were destroyed by fire in early May 1850. He then proceeded to Coloma, where he first visited another patron, John T. Little, and tried his hand at mining. Only toward the end of the month did Jewett meet up with Grayson to make sketches at a site now identified as Hotchkiss Hill near Georgetown.14 From there he returned first to Coloma, and later to San Francisco, where he completed the painting.

Jewett ingeniously organized the figures in The Promised Land in a pyramidal configuration, with Grayson standing at the center of the canvas. Mrs. Grayson and their young son, dressed in an ermine-trimmed coat that reflected the immigrants’ aspirations rather than the apparel of overland travelers, are seated to the right in a pose reminiscent of depictions of the Mother and Child in the Rest on the Flight into Egypt by such artists as Claude Lorrain.15 With the menacing snow-packed peak looming behind them, the settlers pause to ponder the sweeping landscape that welcomes them into the Sacramento Valley. The image Jewett crafted, with its myriad references, secured the artist’s reputation in California. A subject of discussion even while it was being painted, The Promised Land was an instant success; in it “fellow pioneers in the California adventure immediately recognized a symbol of themselves.”16

More common among Jewett’s commissions were portraits of individuals. Among his early efforts is the painting Captain Washington A. Bartlett, U.S.N. (fig. 32), which the artist exhibited at the National Academy of Design in New York in 1851. Bartlett was San Francisco’s first alcalde, or mayor, and his short tenure (from September 1846 to February 1847) was distinguished by the change of the city’s name from Yerba Buena. Afterward, Bartlett returned to military duties, but remained a prominent San Francisco citizen. The portrait was most likely one of a series Jewett was making as part of a gallery of notables that he hoped to sell to the state of California. The project was abandoned after the fire in May 1851 destroyed the portraits in Jewett’s studio.17 In the detailed features of the subject and the setting with a column and a red velvet curtain in the background, the small half-length format painting is consistent with other portraits Jewett made of San Francisco’s leading politicians.

Other portraits made at this time suggest that Jewett also favored landscape backgrounds to complement his subjects and as focal points in their own right. This may reflect an interest he developed while in the East, where he had exhibited landscapes, and his response to California’s impressive geographic features.18 The author of a glowing review of a portrait, Colonel Collier (location unknown), with the subject standing on the north side of Telegraph Hill, for example, acknowledged the landscape background in recommending the painting to the viewer.19

By 1851, Jewett had also completed a portrait of John A. Sutter (location unknown), a man who figured prominently in his work during the years that followed. Jewett not only recorded Sutter several times during the 1850s, but also painted two views of Hock Farm, Sutter’s ranch north of Sacramento (figs. 34 and 35). These paintings were created in rapid succession (1851 and 1852), and are distinguished only by differences in minor figures and the presence of a steamboat at the distant right in the earlier version, Hock Farm (A View of the Butte Mountains from Feather River, California) (Oakland Museum of California). Both compositions show a dog running up to two men upon their arrival along (or departure from) the shore of the Feather River. Although a focal point, the purpose of the visitors’ business is unclear; likewise, the idyllic scenes fail to show the “redwood mansion” that Sutter had reportedly built at Hock Farm in 1849, or the “vineyards, orchards, and gardens of rare plants and shrubs” he maintained there.20 Instead, a crude wood structure beside a vegetable plot draws the eye to the left middle ground, behind which cattle graze on the higher land and the Sutter Buttes appear in the distance. In both versions, the organization of the landscape into foreground, middle ground, and background planes and the detailed rendering of the foliage demonstrate the artist’s Hudson River school training. Jewett pays particular attention to the depiction of the trees along the riverbank and to the foreground figures, and again employs a compositional scheme reminiscent of the paintings of Claude. The tree stumps in the left foreground are, however, outsized in relation to other objects and Jewett seems ill at ease in rendering the distant buttes. Possibly one version of Hock Farm was intended to be published as a lithograph as Sarony and Major had reproduced Jewett’s view of Sutter’s Mill and Coloma Valley for distribution in 1851. That image had been taken from a painting Jewett had sketched at Coloma, which was praised by the San Francisco Daily Alta California as “exceedingly truthful and beautiful.” The resulting print garnered considerable attention: “It is wonderfully minute and accurate, so creditable to the true artist from whose pencil and brush it came, a fresh counterpart of nature.”21

FIG. 34. William Smith Jewett, Hock Farm (A View of the Butte Mountains from Feather River, California), 1851. Oil on canvas, 28 × 39 in. Oakland Museum of California, gift of an anonymous donor.

FIG. 35. William Smith Jewett, Hock Farm, 1852. Oil on canvas, 29 × 40 in. Courtesy of California State Parks, Museum Resource Center.

FIG. 36. William Smith Jewett, Captain Ned Wakeman, ca. 1851. Oil on canvas, 18¾ × 16 in. Oakland Museum of California, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Howard Willoughby and Mr. and Mrs. Edgar Buttner.

For the most part, however, Jewett is known primarily for his many portraits of Gold Rush luminaries. An example of his informal portrait style is represented in his engaging portrait, Captain Ned Wakeman (fig. 36). Wakeman had captured public attention when he sailed the New World out of New York Harbor while his vessel was occupied by United States marshals, depositing the law enforcement officers at Sandy Hook, and proceeding on his voyage. For a number of years the colorful sailor, who was the model for the ship’s master in several stories by Mark Twain, commanded ships sailing to mining supply centers, and served with distinction on San Francisco’s vigilante force. Jewett shows Wakeman aboard a vessel during a storm at night. He draws attention to the sailor’s face by the windswept hair, amount of detail, and the bright light that is focused on it. Other centers of interest in the painting are the gold filigree pin on Wakeman’s shirt and the horn, or speaking trumpet, he holds. The trumpet was a gift to Wakeman from the Committee on Vigilance in 1851 in recognition of his contributions.22 Speaking trumpets, associated with firemen and sea captains, who used them for communications, were embellished and presented as gifts during the Gold Rush. They were very popular at the time, and accounted for much of the business received by San Francisco’s many resident jewelers. Although Francis Marryat protested that they had become ubiquitous, Wakeman nonetheless took obvious pride in his honor.23

Despite the arrival of Charles Christian Nahl, his half-brother, Arthur Nahl, and August Wenderoth—all three professionally trained painters—and the enthusiastic reception that Ayres’s paintings received, in 1854 William Smith Jewett was viewed as the “leading professor among us,” with credit given not only to his great merit, but also to the fact “that there are Californians of taste enough to keep him constantly employed.”24 This comment reinforces the impression Jewett gave in his letters that, although there were no galleries and few exhibitions in San Francisco, artists—at least the most highly regarded—found adequate opportunities to market their skills.

Jewett did encounter resistance while achieving one of his most notable accomplishments: a full-length portrait of Sutter (fig. 37) commissioned by the state of California in 1855. He had understood initially that he would receive five thousand dollars for the painting, an extraordinary amount at the time, but when the contract was drawn up in April 1855, Jewett was awarded only twenty-five hundred dollars. He was then also asked to provide a second painting, of General Wool, without additional recompense.25 If the additional request were not enough, Governor John Bigler approved the contract “with great reluctance.” In terms reminiscent of the debates that took place in commissioning artwork for the United States Capitol, Bigler declared not only that “the amount appropriated I regarded as exceeding the value of the labor performed,” but also that “the financial condition of the State does not, in my opinion, warrant expenditures for objects which can, without detriment to public interests be dispensed with for a time.”26

FIG. 37. William Smith Jewett, Portrait of General John A. Sutter, 1855. Oil on canvas, 118 × 87 in. Courtesy of California State Parks, Museum Resource Center.

On 21 October 1855, the Sacramento Daily Bee printed an open letter from Jewett, indicating that he felt compelled to document the completion of the painting for the state: “I have finished your full-length portrait and I shall present it before the Legislature on Monday next 19th, for their action upon it, hoping only for a slight remuneration sufficient to [defray?] my outlay as I have had it elegantly framed.”27

Jewett’s portrait shows an aging, yet dignified and confident Sutter, attired in dress uniform. The general balances a sword in his right hand, and holds an elaborately plumed helmet. His bright eyes and flushed cheeks suggest an alert and robust figure, and offer no hint of the troubles that had befallen him by the time this image was created. The immediacy of the depiction attests to the numerous times the general posed for Jewett, sittings that lasted several hours apiece.28 The cursory landscape background, with Sutter’s Fort at the right, appears to have been sketched independently. Not only does it lack detail, but also the perspective of the setting—with a large tree in the left foreground overpowering the figures of a guard and a white steed—is out of scale with Sutter himself. The composition shares the incongruities present in Jewett’s scenes of Hock Farm, but lacks their bright colors and detail. In addition to documenting the challenges that landscape views could present Jewett, the schematic treatment of the setting may reflect the short time allotted Jewett to complete the large portrait and his assumption that, once installed in the state capitol, the painting would be viewed at a distance.

A bust-length Portrait of General John A. Sutter (fig. 38), which Jewett executed the following year, also shows Sutter in the uniform of a major-general of the California militia, a public honor that had been bestowed upon him by the legislature in February 1853.29 Again, his garments belie Sutter’s precarious economic circumstances. Although Jewett’s presentation of the general is a striking likeness of the man, the shallow background with the classical devices of a drawn red curtain and a column repeats the conventional treatment used in the portrait of Bartlett.

By late 1856, Jewett was perceived, according to an article that appeared in the Daily Alta California, as “eminently successful” in San Francisco, and his patrons were credited with possessing “a refined and cultivated taste.” Although his portraits were mentioned first in the commentary, the author bestowed his highest praise on a recently completed canvas, The Light of the Cross (location unknown). The religious theme and interior setting of the subject were departures for Jewett, and its favorable reception was induced at least in part by its potential to educate viewers.30

Jewett’s foray into this new subject matter may have been inspired by a commission he was given or by an interest in expanding his repertoire. The Light of the Cross was well received; however, the artist does not appear to have undertaken other religious themes during his stay in California. The theme of J. E. Murdoch as Hamlet (location unknown), from this time as well, was also a departure for the artist. Other surviving paintings from the 1860s are predominantly portraits, whose subjects included Don Juan Temple and his wife, Rafaela Cota de Temple (in the collection of La Casa de Rancho Los Cerritos, Long Beach, California), and Commodore James Thomas Watkins (Chrysler Museum, Norfolk, Virginia).

When the First Industrial Exhibition of the Mechanics’ Institute opened in San Francisco in September 1857, William Smith Jewett was well represented in the art section, in keeping with his reputation. His contributions included eight oil portraits, The Light of the Cross, and J. E. Murdoch as Hamlet. In addition, his Promised Land of 1850 (cat. 33), already well known, was at last placed on public display in California.

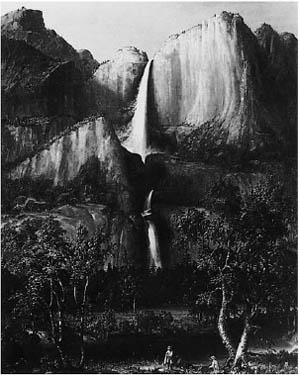

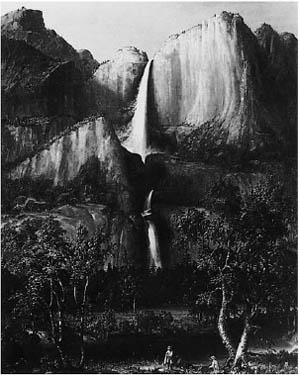

By the late 1850s, Jewett, like a number of other artists, had ventured to Yosemite to depict the spectacular scenery. His Yosemite Falls (fig. 39) is an accomplished landscape and offers charming detail, despite its somewhat stiff composition. Jewett also explored other new subjects at this time, including a large canvas titled Pursued (fig. 40), which the artist donated to the Ladies Christian Commission Fair auction in 1864.

FIG. 38. William Smith Jewett, Portrait of General John A. Sutter, 1856. Oil on canvas, 15½ × 12½ in. Oakland Museum of California, Kahn Collection.

FIG. 39. William Smith Jewett, Yosemite Falls, 1859. Oil on canvas, 52½ × 42 in. Newark Museum, N.J., gift of Mrs. Charles W. Engelhard.

FIG. 40. William Smith Jewett, Pursued, 1863. Oil on canvas, 29 × 36 in. Autry Museum of Western Heritage, Los Angeles.

Although Jewett continued to conduct an active portrait practice in California into the 1860s, much of his energy was devoted to real estate and other financial transactions. Now headquartered in San Francisco, he also traveled to Sacramento to fulfill commissions, spending at least three weeks there on one occasion. Jewett described that trip enthusiastically (“they give me a cheerful welcome and pay well”), but repeatedly expressed his longing to see his friends and family in the East. Nonetheless, he delayed his departure time and again, because of his financial ventures and the commissions he continued to undertake. The artist still boasted of his popularity, and tried to reassure relatives of his continuing affection for them.31 For reasons that are not entirely clear—perhaps concern that he had not met his family’s (or his own) expectations, or reluctance to return home having been so long away—Jewett did not leave San Francisco until fall 1869. The artist thus spent most of his career in California, where his well-received portraits document both the appearance and success of his early pioneer patrons. These animated paintings attest not only to the affluence of his sitters, but also to their confidence and physical well-being. In thus fulfilling the expectations of his clients, Jewett’s portraits offer insights into their values as well as their features. In addition, as a skilled artist who had earned his credentials in the East, Jewett reassured early San Franciscans of the taste they displayed and acknowledged their support for culture.

150 and

150 and  800 each, he declared himself “as jolly . . . as a clam at high water.”6 Financial transactions were conducted in hard currency. With the silver he received in return for a portrait, Jewett had to face the problem for “the first time in my life” of what to do with his money. “So I came home and got a large canvas bag I had used for common trapsticks went back and I shoveled it into it and lugged it home.” Likewise, he noted, costs were astronomical. Nonetheless, Jewett speculated that if business were pursued energetically, “a fortune can be made speedily.”7 He had already profited on a sale of real estate, the first of many such investments Jewett undertook during his twenty-year stay in California, and his detailed reports in letters home suggest that his business ventures were as important to him as the progress of his painting was.

800 each, he declared himself “as jolly . . . as a clam at high water.”6 Financial transactions were conducted in hard currency. With the silver he received in return for a portrait, Jewett had to face the problem for “the first time in my life” of what to do with his money. “So I came home and got a large canvas bag I had used for common trapsticks went back and I shoveled it into it and lugged it home.” Likewise, he noted, costs were astronomical. Nonetheless, Jewett speculated that if business were pursued energetically, “a fortune can be made speedily.”7 He had already profited on a sale of real estate, the first of many such investments Jewett undertook during his twenty-year stay in California, and his detailed reports in letters home suggest that his business ventures were as important to him as the progress of his painting was.