FREDERICK A, BUTMAN, ALEXANDER EDOUART, AND GEORGE TIRRELL

BY THE MID-1850S, artists were attracted to California not so much by gold as for other reasons. Mining was now less of an incentive to immigrate than were the state’s stunning geography and excellent climate, not to mention its flourishing economy. With the advent of the Industrial Exhibitions of the Mechanics’ Institute in 1857, which offered new opportunities to exhibit art, and San Francisco’s establishment as a thriving metropolis, artists could expect the benefits of increasing patronage. Whatever their individual motivations, painters continued to flock to San Francisco in the late 1850s and early 1860s. Several of them, including Frederick Butman, Alexander Edouart, and George Tirrell, made compelling images of communities that drew directly from the events of the Gold Rush.

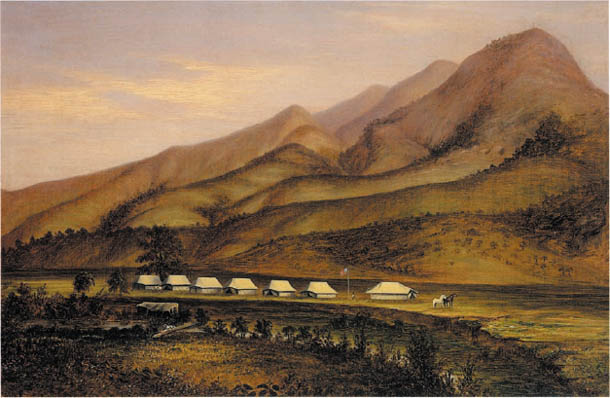

Frederick Butman, who arrived in 1857, has been credited as the first resident artist in California to devote himself exclusively to landscape painting.1 His painting Surveyor’s Camp (fig. 76), of the following year, is one of six views of the 1853 Pacific Coast Geodetic Survey that Captain W. E. Greenwell commissioned from Butman and other artists, including the Nahl brothers. That Butman was chosen to execute one of the scenes indicates that he had quickly established his reputation in San Francisco. Whereas the Nahl family had long been held in esteem as California artists, Butman’s recent arrival postdated the event that he was asked to depict. His disposition of the seven tents at the camp and many of the details—including the dark and white horses paired at the right and the small white dog at the left center—are markedly similar to one by the Nahls.2 However, the buildup of the distant hills in a sweep toward the upper right differs strikingly from the interpretation offered by the Nahls, calling into question the extent to which the various artists may have been working from a common source. The location is not identified in either painting.

Although most likely self-taught, Butman soon came to attention as an artist. Two paintings of Yosemite that he exhibited in the windows of Jones, Wooll & Sutherland, an art-supply and framing store, in late 1859, were described as “particularly worthy of notice for the rich coloring and the truthfulness to nature which the artist has observed throughout.”3 Significantly, Butman went to Yosemite at the same time that Jewett and other artists were making expeditions there, attracted by the splendid scenery and perhaps ready to exploit the new landscape subjects that California offered.

The following year Butman reportedly secured a local sponsor who underwrote the artist’s journeys to remote areas of California and Oregon. On this and subsequent trips, he gathered material for paintings of Lake Tahoe, Mount Shasta, Mount Hood, and other subjects. These continued to receive praise in the local press, and the artist was noted as “delight[ing] in large distances, high mountains, bright sunlight and brilliant coloring.” By the 1860s, however, Butman’s pictures were being criticized as “full of gaudy colors, and look as if they had been painted to sell; they have not the finish nor the fidelity to nature which alone gain the approval of judges.”4

FIG. 76. Frederick Butman, Surveyor’s Camp, 1858. Oil on canvas, 12½ × 18½ in. The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

Although Butman’s views of West Coast scenic landmarks were commented on in the press, two beautiful compositions of subjects close to home failed to attract attention. Perhaps painted as pendants, Hunter’s Point (fig. 77) and Chinese Fishing Village (fig. 78) each offers views of established communities along the west side of San Francisco Bay. Despite its placid appearance, Hunter’s Point shows a variety of activities occurring along the shoreline, from a young couple in conversation to Chinese fishermen on the beach. A well-dressed man, rifle in hand and peering back over his shoulder, sits astride a white horse. The white moldings and broken fence around the building that has fallen into disrepair immediately above him seem out of character with the unpainted wooden structures huddled toward the land’s end, contributing to the mysterious quality of this image.

In contrast, Chinese Fishing Village is a more cohesive composition as well as an important historical document. The canvas represents one of the two earliest Chinese fishing settlements in California, at Rincon Point, near the footings of the present San Francisco—Oakland Bay Bridge. The village was established in the early 1850s, and by 1853 some 150 men in this community who operated 25 boats had pioneered California’s saltwater fishing industry.5 “Butman’s scene substantiates research indicating that the Chinese fishermen ‘lived in small fishing villages of their own construction somewhat removed from other parts of the population. . . . Their villages were located along the waterways . . . and consisted of large, unpainted redwood cabins built on stilts out over the beaches or directly over water.’ The bustling composition also records the industriousness of the fishermen, who are shown engaged in a variety of activities, including work on sampans that are believed to have been constructed in California from Chinese models.”6

Another engaging view of a distinctive community in California is Alexander Edouart’s painting Blessing of the Enrequita Mine (fig. 79) of 1860. Arriving in San Francisco from the East Coast in the early 1850s, the British-born Edouart had traveled up the coast to Mendocino and the Noyo River area by 1857. He made a series of paintings of subjects he encountered there. He was represented in the First Industrial Exhibition of the Mechanics’ Institute with what were listed only as “portraits in oil.” The extended catalogue entry describes Edouart’s depiction of an elderly man as “remarkably fine,” and took “occasion to congratulate the public that the artist now resides among us,” but noted that, having been painted in Italy, the portrait failed to qualify for an award.7 For some reason—perhaps because he hoped to encourage portrait commissions—Edouart must have chosen to enter a work that he had painted as a student nearly a decade earlier.

FIG. 77. Frederick Butman, Hunter’s Point, ca. 1859. Oil on canvas, 24¼ × 36½ in. California Historical Society, San Francisco, gift of Albert M. Bender.

FIG. 78. Frederick Butman, Chinese Fishing Village, 1859. Oil on canvas, 23½ × 36 in. California Historical Society, San Francisco, gift of Albert M. Bender.

Edouart’s finest California paintings are his two versions of the dedication of the quicksilver mines at New Almaden. In contrast to the watercolor Mining in California (see fig. 24), Edouart’s composition shows a specific event, the dedication of the Enrequita Mine before it was opened in 1859. The view shows Mexican and Chilean miners and their families assembling for the blessing that will be given by Father Goetz, the Catholic curate of San Jose. The custom of offering blessing to the mine, those present, and its workers was well established. The festive nature of the event, which would be followed by fireworks, is indicated by the presence of the musicians in the background. Steam rising from the lower right makes reference to the furnaces located below. The assembled figures simultaneously tipping their hats toward the altar create a strong center of interest. Edouart also prominently featured three horses in the foreground, and frames the crowd with portraits of the Eldridge brothers, who owned the mine. Because one version of Blessing of the Enrequita Mine descended through the Eldridge family, it seems likely that they commissioned Edouart to document the event. The product is a striking portrayal of early California life, characterized by brilliant color and attention to detail in both costumes and landscape.

Although his ambitious composition reflects favorably on his skills, Edouart, for whatever reason—most likely either the time that painting entailed or lack of sufficient patronage—soon turned his attention to photography, establishing a successful practice first in San Francisco and later in Los Angeles.

Another painter who had only a brief career as an artist in California was George Tirrell. Little is known about him, but he was accomplished enough to have produced two distinguished achievements. A monumental Panorama of California (now lost) was first exhibited in San Francisco in April 1860 and met with considerable success. An exquisite painting titled View of Sacramento, California, from Across the Sacramento River (fig. 80), which has been dated to between 1855 and 1860, may have been executed in preparation for the panorama. A luminous composition, it offers some insights into how Tirrell represented California during its transition from the heady days of the Gold Rush to a time of increasing settlement accompanied by commercial and agricultural growth. In contrast to John Woodhouse Audubon’s portrayal of the city some years before (see fig. 28), Tirrell’s scene shows a busy harbor and a fair-sized city. Seen from the west, Sacramento’s city hall and waterworks appear at the far left. With more than fifteen boats of many types represented, the view gives evidence of the artist’s love of sailing. Most prominently represented is the Antelope, a sidewheel steamship that was constructed in the East but had transported passengers between San Francisco and Panama during the heyday of the Gold Rush.8 The paddleboat, barge, rowboats, and other craft all indicate continuing activity along the Sacramento River in the years following.

FIG. 79. Alexander Edouart, Blessing of the Enrequita Mine, 1860. Oil on canvas, 29½ × 47½ in. The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

Tirrell, Butman, and Edouart were thus responsible for recording the effect of the Gold Rush on the subsequent development of industries and urban centers in California. Not only did the discovery of gold stimulate growth, but also—as their paintings testify—the arrival of would-be miners from throughout the world meant that people of many cultures participated in and contributed to the communities and commerce that developed in its wake.

The community of artists in San Francisco was likewise becoming established by the late 1850s. With the First Industrial Exhibition of the Mechanics’ Institute in 1857, portraits by the San Franciscans Charles Christian Nahl and Edouart, among others, were featured alongside landscapes by John Henry Dunnel, wood engravings and watercolors by Harrison Eastman, and drawings by August Wenderoth. In all, nearly fifty artists were represented, some by single pieces, others by six or more. Not only was this display of work extremely popular—“continually crowded with admiring spectators” reported the Daily Alta California—but also it won considerable acclaim in the local press.9 The report of the exhibition—published the following year—noted that “the judges . . . express their surprise and gratification at the rapid strides which the fine arts have made in our infant city, and their pleasure at the appreciative spirit of its citizens, without whose encouragement no elegant art would flourish. . . . There can no longer be a doubt that the State possesses an abundance of artistic talent, yearning to evolve itself, and fertile as our soil.”10

The exposition was repeated a year later and again well received. Works by Thomas Ayres (who, by the time the fair opened on 2 September 1858, had perished in a shipwreck), Frederick Butman, the brothers Hubert and George Henry Burgess, and numerous others met with great acclaim. Reflecting the public’s interest in the arts, the Daily Alta California devoted three columns to its review of the fine arts section.11 In the ensuing years, the Mechanics’ Institute exhibitions continued, at first irregularly (after the 1858 show, the next one was held in 1860) and then annually from 1874 until 1891.

In the meantime, talented artists such as Samuel Marsden Brookes (California’s preeminent nineteenth-century Californian still-life painter), the marine specialist Gideon Jacques Denny, and the landscape painter Thomas Hill, had settled in San Francisco, and Albert Bierstadt made the first of two visits there. In 1864, the fine arts were accorded a separate display space at the Mechanics’ Exhibition and a second major public display of artwork (organized by William Smith Jewett and accompanied by an auction to which artists contributed) was offered with the Ladies’ Christian Commission Fair in the fall. These events laid the groundwork for the founding of a local art union in early 1865, when “there were about thirty professional artists in the city.” Like art unions in other American cities, the organization was founded for “the cultivation of the fine arts and the elevation of popular taste,” and it sponsored an art gallery. Its initial reception was enthusiastic—“at the end of three months the membership numbered five hundred and the visitors were more numerous than ever before”—but the organization soon foundered.12 However, momentum for increasing support for the arts was in place. The opening of the Snow and Roos Gallery in 1867 and the founding of the San Francisco Art Association in 1871 provided new exhibition spaces for artists, and when the Art Association opened its California School of Design in February 1874, Northern California boasted galleries and teaching facilities commensurate with its status as a thriving arts community.

FIG. 80. George Tirrell, View of Sacramento, California, from Across the Sacramento River, ca. 1855–60. Oil on canvas, 27 × 48 in. Gift of Maxim Karolik for the M. & M. Karolik Collection of American Paintings, 1815–65, courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

FIG. 81. Charles Christian Nahl, Sunday Morning in the Mines, 1872. Oil on canvas, 72 × 120 in. Crocker Art Museum, Sacramento, Calif., E. B. Crocker Collection.