Abraham Lincoln grew up among people for whom “work” meant raising crops, splitting rails, and hauling loads to the mill. Theirs was an oral culture. Stories flowed freely, but books were scarce, and most folks did not see their value. So when young Abe stole away to read or write, his cousin Dennis Hanks pronounced the customary judgment: “Lincoln was lazy—a very lazy man,” Hanks said. “He was always reading—scribbling—writing—ciphering—writing poetry &c. &c.”

As it turned out, what seemed lazy—developing his relationship to language—became young Lincoln’s most essential work. When he struck out on his own, entering politics, studying law, and establishing himself in the literate communities of New Salem and Springfield, Illinois, Lincoln’s writings ranged far and wide. Some scholars dismiss his nonpolitical productions—for example, his poetry, satire, and scientific meditations—as naive and unpracticed. Other observers see his personal notes—like his melancholy reflections on January 23, 1841—as fodder only for biographical detail.

But it was in this period that Lincoln adopted the work ethic of his youth—and the rhythms and intimacy of spoken language he grew up immersed in—and put them to service in crafting plain language that delivered a substantial message. In these early works, we can hear his voice and can feel his commitment to communicating with his audience. The works here show the writer as a young man. Before long, even Dennis Hanks was claiming credit for teaching his cousin to scribble with a “buzzards quillen.”

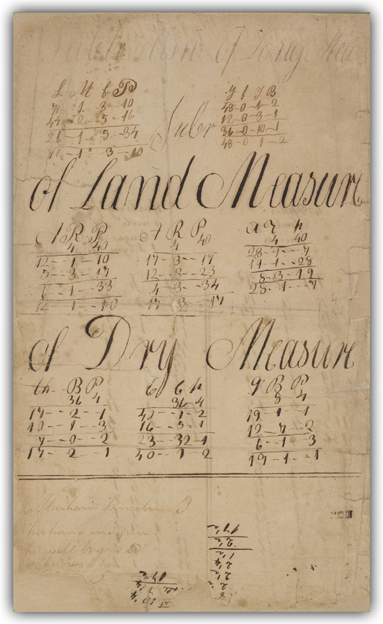

This page from Lincoln’s boyhood notebooks in Indiana—scholars date it from 1824, when he was a teenager—is among the earliest known examples of his writing. The ink is faded, but the lower left-hand corner (enlarged opposite) contains a memorable ditty.

Lincoln’s first written words are, the scholars tell us, probably not original, one of those bits of schoolboy doggerel that nobody teaches and everyone learns (although no one has found one just like it; maybe the joke is his own). But more to the matter, they are a reminder of the single most important thing about the young Lincoln that we know: He loved to read and write. There is no greater divide in life than the one between kids for whom the experience of reading is a painful or tedious one, whose rewards are remote, if real, and those for whom the experience of reading and writing are addictive, entrancing, overwhelming, and so intense as to offer a new life of their own—those for whom the moment of learning to read begins a second life of letters as rich as the primary life of experience. Lincoln was as clear a case of the second kind of child, and man, as anyone who has ever lived. His hand and pen were the axis of his experience, even as he made his living, and his reputation, first from his body and later from his mouth. He lived to read, and the distaste that still shocks us a little in his attitude toward his father—that Tom wrote his name “blunderingly” still offended his steady-handed son years later—surely has its root in this simple cause. It wasn’t that his father could barely read or write; it was that he failed to see the point of it for his son, couldn’t see that it not only had what would have been called “pecuniary value” but life purpose. “His hand and pen”—more than his mind and voice, more even than his heart and soul—his hand and pen are Lincoln, the reading mind turning the page, the writing fingers adding to the sum of the world’s words.

The irony, arresting and in a way poignant, is that Lincoln, a man of action—often murderous, uniquely decisive—was first of all a man of books and thoughts, and a rueful humorist of their inability to mend men’s ways, including his own. He would be good, though, and God, or Providence, or Fate, or merely the contingencies of history—it took him a lifetime to make up his mind which it was to be, and perhaps he never did—alone knew when.

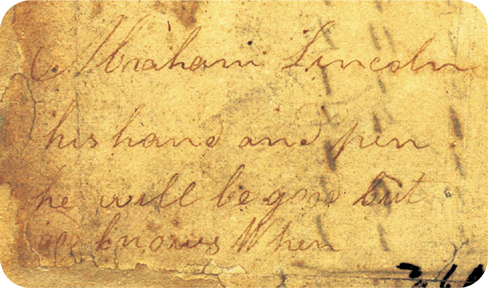

Abraham Lincoln

his hand and pen

he will be good but

god knows When

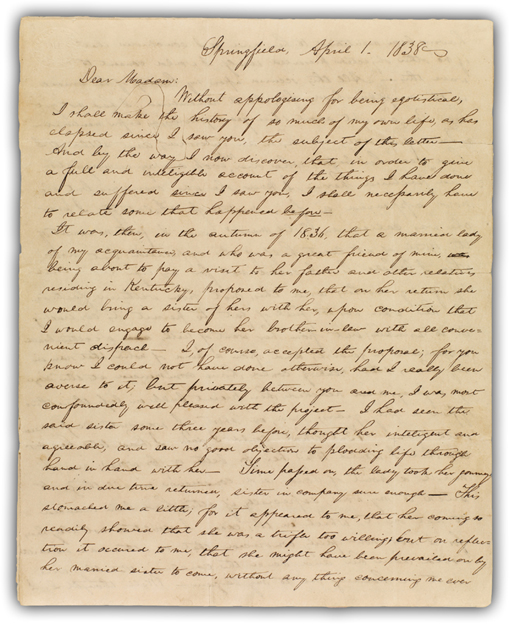

LETTER TO ELIZA BROWNING, APRIL 1, 1838

After a courtship gone badly awry with a young woman from Kentucky, Lincoln explained himself— and satirized the whole affair—in a letter to his friend Eliza Browning.

Click here to see images of the full letter.

Dear Madam:

Without appologising for being egotistical, I shall make the history of so much of my own life, as has elapsed since I saw you, the subject of this letter. And by the way I now discover, that, in order to give a full and inteligible account of the things I have done and suffered since I saw you, I shall necessarily have to relate some that happened before.

It was, then, in the autumn of 1836, that a married lady of my acquaintance, and who was a great friend of mine, who being about to pay a visit to her father and other relatives residing in Kentucky, proposed to me, that on her return she would bring a sister of hers with her, upon condition that I would engage to become her brother-in-law with all convenient dispach. I, of course, accepted the proposal; for you know I could not have done otherwise, had I really been averse to it; but privately between you and me, I was most confoundedly well pleased with the project. I had seen the said sister some three years before, thought her inteligent and agreeable, and saw no good objection to plodding life through hand in hand with her. Time passed on, the lady took her journey and in due time returned, sister in company sure enough. This stomached me a little; for it appeared to me, that her coming so readily showed that she was a trifle too willing; but on reflection it occured to me, that she might have been prevailed on by her married sister to come, without any thing concerning me ever having been mentioned to her; and so I concluded that if no other objection presented itself, I would consent to wave this. All this occured upon my hearing of her arrival in the neighbourhood; for, be it remembered, I had not yet seen her, except about three years previous, as before mentioned.

Mary Owens remembered onetime suitor Lincoln as “deficient in those little links which make up the chain of a woman’s happiness.”

In a few days we had an interview, and although I had seen her before, she did ^ not look as my immagination had pictured her. I knew she was over-size, but she now appeared a fair match for Falstaff; I knew she was called an “old maid”, and I felt no doubt of the truth of at least half of the appelation; but now, when I beheld her, I could not for my life avoid thinking of my mother; and this, not from withered features, for her skin was too full of fat, to permit its contracting in to wrinkles; but from her want of teeth, and weather-beaten appearance in general, and from a kind of notion that ran in my head, that nothing could have commenced at the size of infancy, and reached her present bulk in less than thirtyfive or forty years; and, in short, I was not all pleased with her. But what could I do? I had told her sister that I would take her for better or for worse; and I made a point of honor and conscience in all things, to stick to my word, especially if others had been induced to act on it, which in this case, I doubted not they had, for I was now fairly convinced, that no other man on earth would have her, and hence the conclusion that they were bent on holding me to my bargain. Well, thought I, I have said it, and, be consequences what they may, it shall not be my fault if I fail to do it. At once I determined to consider her my wife; and this done, all my powers of discovery were put to the rack, in search of perfections ^ in her, which might be fairly set-off to against her defects. I tried to immagine she was handsome, which, but for her unfortunate corpulency, was actually true. Exclusive of this, no woman that I have seen, has a finer face. I also tried to convince myself, that the mind was much more to be valued than the person; and in this, she was not inferior, as I could discover, to any with whom I had been acquainted.

Lincoln’s longtime Illinois political ally Orville Hickman Browning had the distinction of losing an election to Democrat Stephen A. Douglas fourteen years before Lincoln did the same in his 1858 quest for the U.S. Senate. Browning became Lincoln’s trusted advisor, even though he did not support him for the 1860 presidential nomination.

Shortly after this, without attempting to come to any positive understanding with her, I set out for Vandalia, where and when you first saw me. During my stay there, I had letters from her, which did not change my opinion of either her intelect or intention; but on the contrary, confirmed it in both. All this while, although I was fixed “firm as the surge repelling rock” in my resolution, I found I was continually repenting the rashness, which had led me to make it. Through life I have been in no bondage, either real or immaginary from the thraldom of which I so much desired to be free. After my return home, I saw nothing to change my opinion of her in any particular. She was the same and so was I. I now spent my time [??] between planing how I might get along through life when after my contemplated change of circumstances should have taken place; and how I might procrastinate the evil day for a time, which I really dreaded as [???] much — perhaps more, than an irishman does the halter. After all my suffering upon this deeply interesting subject, here I am, wholly unexpectedly, completely out of the “scrape”; and I ^ now want to know, if you can guess how I got out of it. Out clear in every sense of the ^ term; word; no violation of word, honor or conscience. I dont believe you can guess, and so I may as well tell you at once. As the lawyers say, it was done in the manner following, towit. After I had delayed the matter as long as I thought I could in honor do, which by the way ^ had brought me round into the last fall, I concluded I might as well bring it to a consumation without further delay; and so I mustered my resolution, and made the proposal to her direct; but, shocking to relate, she answered, no. At first I supposed she did it through an affectation of modesty, which I thought but ill-become her, under the peculiar circumstances of her case; but on my renewal of the charge, I found she repeled it with greater firmness than before. I tried it again and again, but with the same success, or rather with the same want of success. I finally was forced to give it up, at which I verry unexpectedly found myself mortified almost beyond endurance. I was mortified, it seemed to me, in a hundred different ways. I [????] for the first time began My vanity was deeply wounded by the reflection, that I had so long been too stupid to discover her intentions, and at the same time never doubting that I understood them perfectly; and also, that she whom I had taught myself to believe no body else would have, had actually rejected me with all my fancied greatness; and to cap the whole, I then, for the first time, began to suspect that I was ^ really a little in love with her. But let it all go. I’ll try and out live it. Others have been made fools of by the girls; but this can never be with truth said of me. I most emphatically, in this instance, made a fool of myself. I have now come to the conclusion never ^ again to think of marrying; and for this reason; I can never be satisfied with any one who would be block-head enough to have me.

When you receive this, write me a long yarn about something to amuse me. Give my respects to Mr. Browning.

Your sincere friend

A. Lincoln

Mrs. O. H. Browning

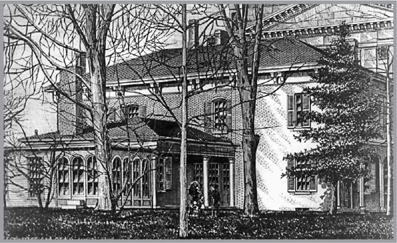

Although he resolved in this letter “never again to think of marrying,” Abraham Lincoln wed Mary Todd in this imposing Springfield mansion on November 4, 1842. The house belonged to her sister, Elizabeth Todd Edwards. Here, nearly forty years later, on July 15, 1882, the president’s widow died.

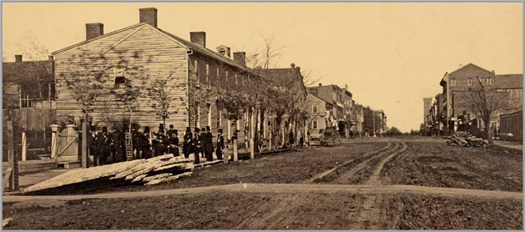

Describing Springfield as a “busy wilderness” after he moved to the new state capital in 1837—one of its muddy streets is shown here in an early photo—Lincoln admitted he felt “quite as lonesome here as I ever was anywhere in my life.”

It’s 1838. The twenty-six-year-old Charles Dickens has just published Nicholas Nickleby. Nikolai Gogol, a pointy-nosed twenty-nine-year-old Russian, is working on Dead Souls. What a generation! In Illinois, Lincoln, who is twenty-nine, pens—with almost no revision, it would appear—this comic gem.

In the space of a few lines, the subject of the letter, a Miss Mary Owens, goes from a fetching/slim/intelligent catch to a plus-sized, mother-suggesting bulk: wrinkle-free, yes, but only because so badly overstuffed. The humor is in the rapidity of this transformation. Miss Owens swells and grows homelier right in front of our eyes, as poor, tricked Abe stands there in her widening shadow, stovepipe hat in hand, contemplating his cheerless amorous future.

In truth, Owens was a beauty, if a little portly. She rejected Lincoln’s marriage proposal because she felt he would be “deficient in those little links which make up the chain of woman’s happiness,” citing, among other things, the time he failed to carry a married woman’s fat baby up a hill. Lincoln was bruised by her refusal; hence, perhaps, this savage, false, comic sketch of her, which he never expected to be made public.

A lesser writer (embarrassed, rejected), might have lingered too long on the riff of the Suddenly Repulsively Swelling Woman. But Lincoln turns his comic eye toward his own failings. This elevates the piece from satire to pathos. The story is suddenly sadder, a case study of human bumbling in the realm of the heart.

LETTER TO JOHN T. STUART, JANUARY 23, 1841

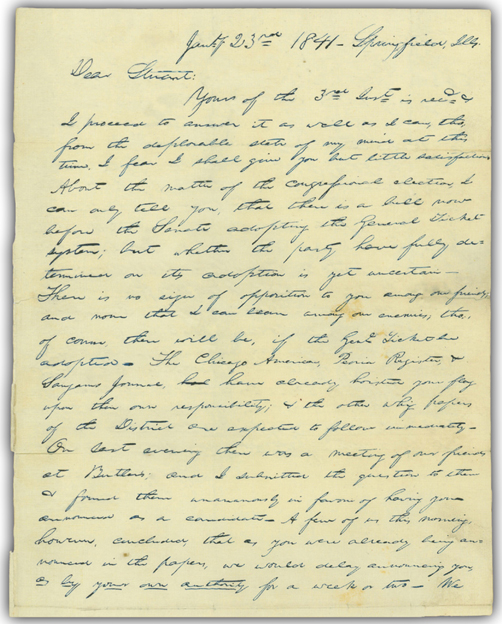

With his senior law partner at Congress in Washington, Lincoln was tasked to send regular updates on the political scene. But on this grim winter’s day, his mind was in such “deplorable” shape that his depression—perhaps the worst spell in a life of melancholy—became the main topic.

Click here to see images of the full letter.

Jany. 23rd 1841- Springfield, Ills.

Dear Stuart:

Yours of the 3rd Inst is recd & I proceed to answer it as well as I can, tho, from the deplorable state of my mind at this time, I fear I shall give you but little satisfaction. About the matter of the congressional election, I can only tell you, that there is a bill now before the Senate adopting the General Ticket system; but whether the party have fully determined on it’s adoption is yet uncertain. There is no sign of opposition to you among our friends; and none that I can learn among our enemies; tho’, of course, there will be, if the Genl Ticket be adopted. The Chicago American, Peoria Register, & Sangamo Journal, had have already hoisted your flag upon their own responsibility; & the other whig papers of the District are expected to follow immediately. On last evening there was a meeting of our friends at Butler’s; and I submitted the question to them & found them unanamously in favour of having you announced as a candidate. A few of us this morning, however, concluded, that as you were already being announced in the papers, we would delay announcing you, as by your own authority for a week or two. We thought that to appear too keen about it might spur our opponents on about their Genl. Ticket project. Upon the whole, I think I may say with certainty, that your reelection is sure, if it be in the power of the whigs to make it so.

For not giving you a general summary of news, you must pardon me; it is not in my power to do so. I am now the most miserable man living. If what I feel were equally distributed to the whole human family, there would not be one cheerful face on the earth. Whether I shall ever be better I can not tell; I awfully forebode I shall not. To remain as I am is impossible; I must die or be better, it appears to me. The matter you speak of on my account, you may attend to as you say, unless you shall hear of my condition forbidding it. I say this, because I fear I shall be unable to attend to any bussiness here, and a change of scene might help me. If I could be myself, I would rather remain at home with Judge Logan. I can write no more.

Your friend, as ever —

A. Lincoln

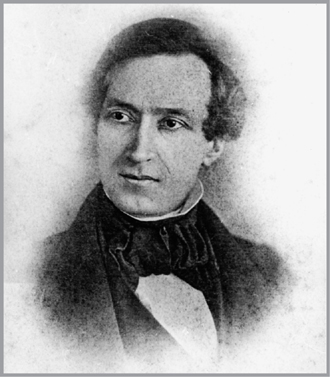

Few men had more impact on Lincoln’s early life than John Todd Stuart. The Whig attorney encouraged Lincoln to study law, lent him books, then took him into his practice as a partner. Stuart was also the cousin of Lincoln’s future wife, Mary Todd.

The signs of depression in this letter are reassuringly evocative of the definitional ones cataloged in modern diagnostic manuals. All depressives think that no one else has borne such pain as they know. All believe that they will never get better, that their agony is intransient. Depressed people believe that they are doing all they can to keep up with the basic business of their daily lives and cannot—as Lincoln would have it—write more. Lincoln asserts that he must get better or die, and that he does not believe he will get better; most depressives experience their despondency as mortal. Depression is in general an illness of self-obsession, and for all the dutiful rundown of the letter’s ostensible purpose in the opening paragraph, Lincoln’s real energy is devoted to narrating his own pain. What is particularly striking here, however, is that the thirty-one-year-old Lincoln does not assign any external cause for his depression.

Clinical depression tends to attach to external circumstances, so that it usually appears to have triggers even when it is essentially endogenous. But while many depressed people are distraught at the tiniest imperfections in their own lives, Lincoln manages in the end to be distraught about the human price paid by a nation facing its sorest test. There is a fallacy in circulation that depression is necessarily correlated with dysfunction, but more recent research has emphasized that there is such a thing as high-functioning depression, in which people are afflicted with the paralytic sensations of emotional deadness, isolation, and sorrow without the paralysis itself. Lincoln had the world’s highest-functioning depression; weighted down, he contrived to lead a divided country through some of its darkest hours.

It is almost as though Lincoln, having been afflicted early in his life by desolation without a cause and failing to mitigate it, ultimately found sufficient cause for it in the terrible war for the union in which he so devoutly believed. Today, a diagnosis of depression is considered sufficient to invalidate anyone’s presidential campaign. We have spent years in a great war led by a president without any capacity for misery such as this, and his absence of a depressive response seems far more mad than the clinical syndrome portrayed in Lincoln’s correspondence. War warrants despair, and the despair that can locate a just war on which to drape itself is the constructive basis not only for deep humanity, but also for great leadership, even for wisdom.

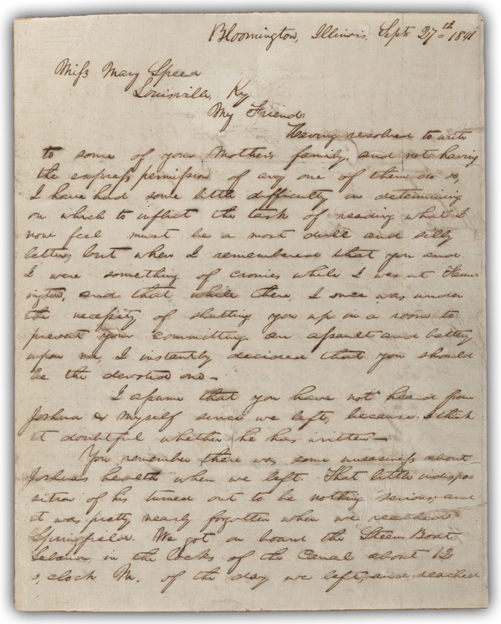

LETTER TO MARY SPEED, SEPTEMBER 27, 1841

Lincoln wrote to the half sister of his closest friend, Joshua Fry Speed, shortly after a long stay on their family estate in Louisville. His narration of an encounter with a group of shackled slaves on the Ohio River has long intrigued scholars, and fueled arguments on all sides.

Click here to see images of the full letter.

Bloomington, Illinois, Sept 27th 1841

Miss Mary Speed

Louisville, Ky

My Friend:

Having resolved to write to some of your Mother’s family, and not having the express permission of any one of them do so, I have had some little difficulty in determining on which to inflict the task of reading what I now feel must be a most dull and silly letter; but when I remembered that you and I were something of cronies while I was at Farmington, and that, while there, I once was under the necessity of shutting you up in a room to prevent your committing an assault and battery upon me, I instantly decided that you should be the devoted one.

I assume that you have not heard from Joshua & myself since we left, because I think it doubtful whether he has written.

Lincoln made an extended visit to Farmington, the gracious Speed family estate near Louisville, in August and September, 1841.

You remember there was some uneasiness about Joshua’s health when we left. That little indisposition of his turned out to be nothing serious; and it was pretty nearly forgotten when we reached Springfield. We got on board the Steam Boat Lebanon, in the locks of the Canal about 12 o,clock Pm. of the day we left, and reached St. Louis the next Monday at 8 P.M.

Nothing of interest happened during the passage, except the vexatious delays occasioned by the sand bars be thought interesting. By the way, a fine example was presented on board the boat for contemplating the effect of condition upon human happiness. A gentleman had purchased twelve negroes in diferent parts of Kentucky and was taking ^ them to a farm in the South. They were chained six and six together. A small iron clevis was around the left wrist of each, and this fastened to the main chain ^ by a shorter one at a convenient ^ distance distant from the others; so that the negroes were strung together precisely like so many fish upon a trot-line. In this condition they were being separated forever from the scenes of their childhood, their friends, their fathers and mothers, and brothers and sisters, and many of them, from their wives and children, and going into perpetual slavery where the lash of the master is proverbially more ruthless and unrelenting than any other where; and yet amid all these distressing circumstances, as we would think them, they were the most cheerful and apparantly happy creatures on board. One, whose offence for which he had been sold was an over-fondness for his wife, played the fiddle almost continually; and the others danced, sung, cracked jokes, and played various games with cards from day to day. How true it is that “God tempers the wind to the shorn lamb,” or in other words, that He renders the worst of human conditions tolerable, while He permits the best, to be nothing better than tolerable.

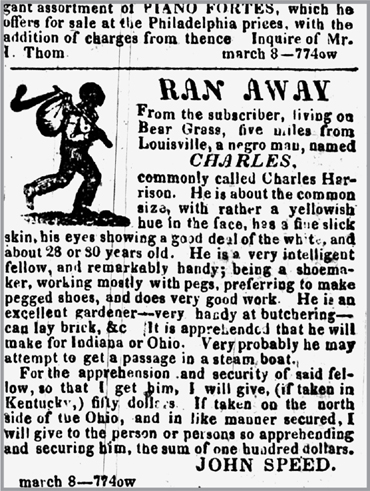

The Speed homestead relied on slave labor and, as this newspaper advertisement indicates, the family pursued its runaway “property” relentlessly.

To return to the narative. When we reached Springfield, I staid but one day when I started on this tedious circuit where I now am. Do you remember my going to the city while I was in Kentucky, to have a tooth extracted, and making a failure of it? Well, that same old tooth got to paining me so much, that about a week since I had it torn out, bringing with it a bit of the jaw-bone; the consequence of which is that my mouth is now so sore that I can neither talk nor eat. I am litterally “subsisting on savoury remembrances” — that is, being unable to eat, I am living upon the remembrance of the delicious dishes of peaches and cream we used to have at your house.

Lincoln’s Springfield roommate, Joshua Fry Speed, was the best friend the future president ever had. Though Speed opposed Lincoln in the election of 1860, he became a crucial Union ally in wartime Kentucky.

When we left, Miss Fanny Henning was owing you a visit, as I understood. Has she paid it yet? If she has, are you not convinced that she is one of the sweetest girls in the world? There is but one thing about her, so far as I could perceive, that I would have otherwise than as it is. That is something of a tendency to melancholly. This, let it be observed, is a misfortune, not a fault. Give her an assurance of my very highest regard, when you see her.

Is little Siss Eliza Davis at your house yet? If she is, kiss her “o,er and o,er again” for me. Tell your mother that I have not got her “present” with me; but that I intend to read it regularly when I return home. I doubt not that it is really, as she says, the best cure for the “Blues” could one but take it according to the truth. Give my respects to all your sisters (including “Aunt Emma”) and brothers. Tell Mrs. Peay, of whose happy face I shall long retain a pleasant remembrance, that I have been trying to think of a name for her homestead, but, as yet, can not satisfy myself with one. I shall be very happy to receive a line from you, soon after you receive this; and, in case you choose to favour me with one, address it to Charleston, Coles Co., Ills as I shall be there about the time to receive it. Your sincere friend

A. Lincoln

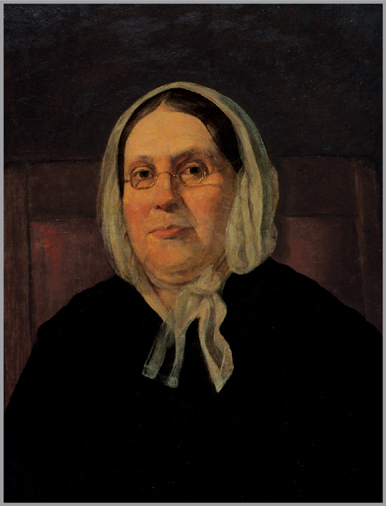

Twenty years after he wrote this letter, President Lincoln inscribed his photograph to the woman in this portrait, the “pious” Lucy Speed, still fondly recalling the Bible she had given him back in 1841.

Having broken his engagement to Mary Todd in a rather cowardly way and then deciding that he loved her after all, the thirty-two-year-old Lincoln fell into a serious depression. He repaired to the Kentucky plantation of his close friend Joshua Speed, where, after a month, his spirits were somewhat restored. In this letter to Joshua’s half sister, written upon his return to Illinois, Lincoln begins playfully, which suggests how well he could get along with women who were not thinking to marry him. He asks to be remembered one way or another to various females, old and young, as if, with his visit to the Speeds, he has found a surrogate family. His wait-and-see remark about the Bible as a cure for his “Blues” indicates his lifelong ambivalence about doctrinal religion, and his account of the chained but cheerful slaves on the Steamboat Lebanon reveals a certain lingering gloominess. Is he comparing their fate favorably to his own? The entire passage is ambiguous. Is he the Northerner admiring the slaves’ fortitude or the Southerner noting their incomprehension? In any event it is disturbing to read, in his own hand, the future president’s description of slaves as cheerful and happy: We think how torturous is moral progress when even the greatest mind of the age may be reflecting the ideology of the very system it finds abhorrent.

Generations of illustrators showed Lincoln performing manual labor on the prairie—a book never far from his side.

Though Lincoln thought this 1857 photograph “a true one,” his fastidious wife loathed it—“owing to the disordered condition of the hair,” its subject admitted. But after the 1860 convention, printmakers resurrected it because it fit the developing image of the rough-hewn, self-made man.

The antislavery artist Eastman Johnson created this iconic portrait of the boy Lincoln studying by firelight in his boyhood home.

LETTER TO ANDREW JOHNSTON, INCLUDING POEM, SEPTEMBER 6, 1846

An avid reader of poetry, Lincoln tried his hand at verse too. Here he sets up and delivers the second of a three-part effort to his literary friend Andrew Johnston, who would arrange to publish the lines in the Quincy Whig. Lincoln thought enough of his poem to allow publication— but asked that it be made anonymous.

Click here to see images of the full letter.

Friend Johnson:

You remember when I wrote you from Fremont last spring, sending you a little canto of what I called poetry, I promised to bore you with another some time. I now fulfil the promise. The subject of the present one is an insane man. His name is Matthew Gentry. He is three years older than I, and when we were boys we went to school together. He was rather a bright lad, and the son of the rich man of our very poor neighbourhood. At the age of nineteen he unaccountably became furiously mad, from which condition he gradually settled down into harmless insanity. When, as I told you in my other letter I visited my old home in the fall of 1844, I found him still lingering in this wretched condition. In my poetizing mood I could not forget the impressions his case made upon me. Here is the result.

But here’s an object more of dread

Than ought the grave contains.

A human form with reason fled,

While wretched life remains.

Poor Matthew! Once of genius bright,

A fortune-favored child.

Now locked for aye, in mental night,

A haggard mad-man wild.

Poor Matthew! I have ne’er forgot,

When first, with maddened will,

Yourself you maimed, your father fought,

And mother strove to kill;

When terror spread, and neighbours ran,

Your dange’rous strength to bind;

And soon, a howling crazy man

Your limbs were fast confined.

How then you strove and shrieked aloud,

Your bones and sinews bared;

And fiendish on the gazing crowd,

With burning eye balls glared.

And begged, and swore, and wept and prayed,

With maniac laugh joined.

How fearful were those signs displayed

By pangs that killed thy mind!

And when at length, tho’ drear and long,

Time soothed thy fiercer woes,

How plaintively thy mournful song

Upon the still night rose.

I’ve heard it oft, as if I dreamed,

Far distant, sweet, and lone.

The funeral dirge, it ever seemed

Of reason dead and gone.

To drink its strains, I’ve stole away,

All stealthily and still,

Ere yet the rising god of day

Had streaked the Eastern hill.

Air held his breath; trees, with the spell,

Seemed sorrowing angels round,

Whose swelling tears in dew-drops fell

Upon the listening ground.

But this is past; and nought remains,

That raised thee o’er the brute.

Thy piercing shrieks, and soothing strains,

Are like, forever mute.

Now fare thee well — more thou the cause,

Than subject now of woe.

All mental pangs, by time’s kind laws,

Hast lost the power to know.

O death! Thou awe-inspiring prince,

That keepst the world in fear;

Why dost thou tear more blest ones hence,

And leave him ling’ring here?

If I should ever send another, the subject will be a “Bear hunt”.

Yours as ever

A. Lincoln

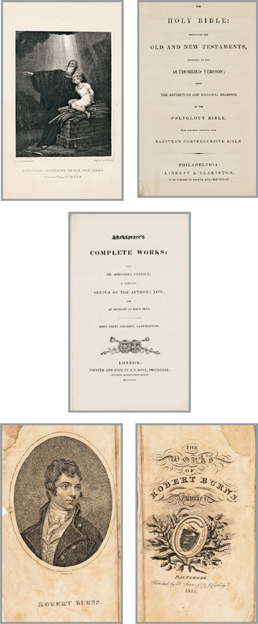

Lacking formal education, young Lincoln read voraciously, and particularly loved poetry. Three of the texts he surely read were the Bible and works by Shakespeare and Robert Burns. “Burns never touched a sentiment,” he later told his secretary, “without carrying it to its ultimate expression, and leaving nothing further to be said.”

Abraham Lincoln’s poem “My Childhood Home I See Again” begins with the conventional nostalgia the title implies. The lines, at first merely adept, proceed from that nostalgia to elegy and then beyond elegy to a distinctly less conventional treatment of mortality: So many have died since the poet was last in Indiana that he feels that—with a shock of plain language as appears so often in Lincoln’s prose—“I’m living in the tombs.”

That unsettling phrase leads to “But here’s an object more of dread.” The “object” involves the mystery of a promising life that devolves into violent insanity and, after that horror, song: song of a terrible beauty, followed by bleak silence.

This “canto” (Lincoln’s term) concerns his childhood schoolmate Matthew Gentry (like Lincoln, “rather a bright lad,” and unlike Lincoln, from a well-off family). As Matthew’s life story departs from comfortable expectation into homicidal, self-maiming rage, imploring grief, and absolute loss, Lincoln’s verses also change from expert ballad stanzas to something far less comfortable. Imprisoned, Matthew sings. Lincoln recalls feeling drawn to that “sweet and lone” singing: “the funeral dirge, it ever seemed / Of reason dead and gone.”

What can it mean that Lincoln recalls of that beautiful, haunting dirge that he often “stole away” to hear it, “All stealthily and still”? The lines describing Lincoln’s furtive pleasure in broken Matthew’s song emerge into a mysterious simplicity concentrated like that of William Blake:

Air held his breath; trees, with the spell,

Seemed sorrowing angels round,

Whose swelling tears in dew-drops fell

Upon the listening ground.

Here a great prose writer attains actual poetry: an art between speech and music, evoked by Lincoln’s term “canto.” The lines reflect Lincoln’s characteristic attainment of light and darkness on a monumental scale: his mind’s clarity and mystery represented here in fellow-feeling and terror, the eerie mingling of magnetism and dread, eloquence and silence.

Though Lincoln harbored no romantic illusions about his hardscrabble years in “the state of my early life,” artists imagined highlights from his early pursuits—like piloting a flatboat—to promote the politician as an exemplar of American opportunity.

LETTER TO MARY LINCOLN, APRIL 16, 1848

Mary Lincoln accompanied her husband to Washington for his 1847–48 term in the U.S. House of Representatives. But she soon returned—with their two boys, Robert and Edward—to live with her family in Lexington, Kentucky, where Lincoln wrote her.

Click here to see images of the full letter.

Dear Mary:

In this troublesome world, we are never quite satisfied. When you were here, I thought you hindered me some in attending to business; but now, having nothing but business — no variety — it has grown exceedingly tasteless to me. I hate to sit down and direct documents and I hate to stay in this old room by myself. You know I told you in last sunday’s letter, I was going to make a little speech during the week; but the week has passed away without my getting a chance to do so; and now my interest in the subject has passed away too. Your second and third letters have been received since I wrote before. Dear Eddy [thinks] thinks father is “gone tapila.” Has any further discovery been made as to the breaking into your grand-mother’s house? If I were she, I would not remain there alone. You mention that your uncle John Parker is likely to be at Lexington. Dont forget to present him my very kindest regards.

I went yesterday to hunt the little plaid stockings, as you wished; but found that McKnight has quit business, and Allen had not a single pair of the description you give, and only one [???] plaid pair of any sort that I thought would fit “Eddy’s dear little feet”. I have a notion to make another trial tomorrow morning. If I could get them, I have an excellent chance of sending them. Mr. Warrick Tunstall, of St. Louis is here. He is to leave early this week, and to go by Lexington. He says he knows you, and will call to see you; and he voluntarily asked, if I had not some package to send to you.

The earliest known photograph of Mary Lincoln, ca. 1846. A bewitching belle in her youth, she could, a contemporary testified, “make a bishop forget his vows.”

I wish you to enjoy yourself in every possible way; but is there no danger of wounding the feelings of your good father, by being so openly intimate with the Wickliffe family?

Mrs. Broome has not removed yet; but she thinks of doing so tomorrow. All the house — or rather, all with whom you were on decided good terms — send their love to you. The others say nothing.

Very soon after you went away, I got what I think a very pretty set of shirt-bosom studs — modest little ones, jet set in gold, only costing 50 cents a piece, or 1.50 for the whole.

Suppose you do not prefix the “Hon” to the address on your letters to me any more. I like the letters very much, but I would rather they should not have that upon them. It is not necessary, as I suppose you have thought, to have them to come free.

And you are entirely free from head-ache? That is good—good — considering it is the first spring you have been free from it since we were acquainted. I am afraid you will get so well, and fat, and young, as to be wanting to marry again. Tell Louisa I want her to watch you a little for me. Get weighed, and write me how much you weigh.

I did not get rid of the impression of that foolish dream about dear Bobby till I got your letter written the same day. What did he and Eddy think of the little letters father sent them? Dont let the blessed fellows forget father.

A day or two ago Mr. Strong, here in Congress, said to me that Matilda would visit here within two or three weeks. Suppose you write her a letter, and enclose it in one of mine; and if she comes I will deliver it to her, and if she does not, I will send it to her.

Most affectionately

A. Lincoln

The original Bullfinch dome still towered above it—and its now-familiar east and west wings had yet to appear—when John Plumbe took the first photograph ever made of the United States Capitol.

“In this troublesome world, we are never quite satisfied.” It sounds like the beginning of a realist novel, an ironic comment upon the human condition. Yet, for Lincoln, this slightly distancing move, measured and balanced, allows him to reveal a deep personal need, as if to say, I did not want you to stay, but now that you’re gone I feel aimless and alone. Even more: Without you nothing is going right. The speech I wanted to make did not happen, and now I’ve lost interest in it. I could not even find the “little plaid stockings” you wanted me to buy. The letter opens in this pensive, subdued mood, with its narrative of failure and mistake. Yet the very activity of writing seems to cheer Lincoln—to lift his depression—as he feels his way back through sentences and paragraphs into the intimacy of marriage.

By the middle of the letter he’s found his footing, and gently chides Mary for this and that, teasing her about her weight and the trail of enemies she’s left behind in their boardinghouse (revealing, perhaps, one of the difficulties Mary’s presence in Washington created for him). Yet Lincoln cannot shake off the brooding anxiety that separation and loss will always engender in him. The boys—don’t let them forget me, he pleads.

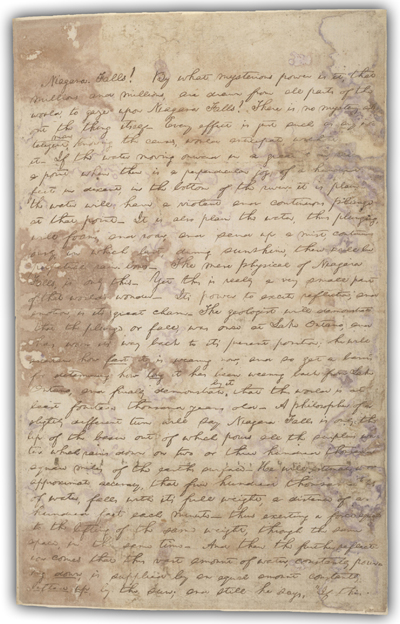

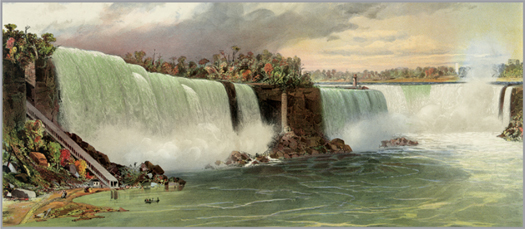

FRAGMENT ON NIAGARA FALLS, CA. SEPTEMBER 25–30, 1848

His political career on the skids after an unpopular stand against the Mexican–American War, Lincoln seems to have been considering a career on the lyceum circuit. This unfinished sketch on the mighty Niagara may have been intended as a draft for a public lecture.

Click here to see images of the full letter.

Niagara Falls! By what mysterious power is it, that millions and millions, are drawn from all parts of the world, to gaze upon Niagara Falls? There is no mystery about the thing itself. Every effect is just such as any inteligent ^ man knowing the causes, would anticipate, without it. If the water moving onward in a great river, reac[hes] a point when there is a perpendicular jog, of a hundred feet in descent, in the bottom of the river, it is plain the water will have a violent and continuous plunge at that point. It is also plain the water, thus plunging, will foam, and roar, and send up a mist, continuously, in which last, during sunshine, there will be perpetual rain-bows. The mere physical of Niagara Falls, is only this. Yet this is really a very small part of that world’s wonder. It’s power to excite reflection, and emotion, is it’s great charm. The geologist will demonstrate that the plunge or fall, was once at Lake Ontario, and has worn it’s way back to it’s present position; he will ascertain how fast it is wearing now, and so get a basis for determining how long it has been wearing back from Lake Ontario, and finally demonstrate ^ by it that the world is at least fourteen thousand years old. A philosopher of a slightly different turn will say Niagara Falls is only the lip of the basin out of which pours all the surplus water which rains down on two or three hundred thousand square miles of the earths surface. He will estimate w[ith] approximate accuracy, that five hundred thousand [to]ns of water, falls with it’s full weight, a distance of a hundred feet each minute — thus exerting a force equal to the lifting of the same weight, through the same space, in the same time. And then the further reflection comes that this vast amount of water, constantly pouring down, is supplied by an equal amount constantly lifted up, by the sun; and still he says, “If this much is lifted up, for this one space of two or three hundred thousand square miles, an equal amount must be lifted for every other equal space; an[d] he is overwhelmed in the contemplation of t[he] vast power the sun is constantly exerting in [the] quiet, noisless opperation of lifting water up t[o be] rained down again.

But still there is more. It calls up the indefinite past. When Columbus first sought this continent — when Christ suffered on the Cross — when Moses led Israel through the red Red-Sea — nay, even, when Ad-first came from the hand of his Maker — am was made then as now, Niagara was roaring here. The eyes of that species of extinct giants, whose bones fill the Mounds of America, have gazed on Niagara, as ours do now. Cotemporary with the whole race of man, men, and older than the first man, Niagara is ^ strong and fresh to-day as ten thousand years ago. The Mammoth and Mastodon now so long dead, that fragments of their monstrous bones, alone testify, that they ever lived, have gazed on Niagara. In that long — long time, never still for a single moment — Never dried, never froze, never slept, never rested,

Congressman Lincoln took an indirect route home from Washington—charging taxpayers for the costly detour—just to visit Niagara Falls. His first reaction was prosaic, wondering “where in the world did all the water come from,” but the falls soon moved him to lyricism.

Lincoln knew rivers, and to know rivers was to be intimate with currents and channels, headwaters and feeders, lakes and falls and spectrumed mists. In 1828, at nineteen, he joined the crew of a flatboat carrying goods to New Orleans. By twenty-one he was a seasoned and canny riverman; so it should not surprise that he was drawn to reflect on Niagara’s bellowing forces. What genuinely startles is the science, the drive to encompass the physical knowledge that will explain nature empirically, through dispassionate geological understanding. For Lincoln, Niagara Falls is an experiment in a terrestrial laboratory designed to produce a proof: the age of the earth.

“The geologist,” he writes, “will demonstrate that the plunge, or fall, was once at Lake Ontario, and has worn its way back to its present position; he will ascertain how fast it is wearing now, and so get a basis for determining … that this world is at least fourteen thousand years old.” This observation was set down in the late 1840s; astrophysics was unforeseen. Here it is not Lincoln who falters, but the limited science of his era. And still his exposition of the formation of the falls cannot be challenged.

Lincoln and science! A juxtaposition we must now weave into our national portrait, perhaps too marmoreally statuesque, as Niagara itself is too often fixed into a kind of gigantically heroic sculpture. How unmythical, how factual, is Lincoln’s Niagara, “the lip of the basin out of which pours all the surplus water which rains down on two or three hundred square miles of the earth’s surface.”

But here lives the other Lincoln too, the poet of the Gettysburg Address, in equal step with the geologist: the metaphysical Lincoln who drills through the old bones of time, for whom ceaseless Niagara is both measured tonnage and the immeasurable weight of millennia. “Never dried, never froze, never slept, never rested,” he sings. Eight extraordinary English words, yet each one commonplace and clear as a drop of water.

Of which lasting hymns are made.

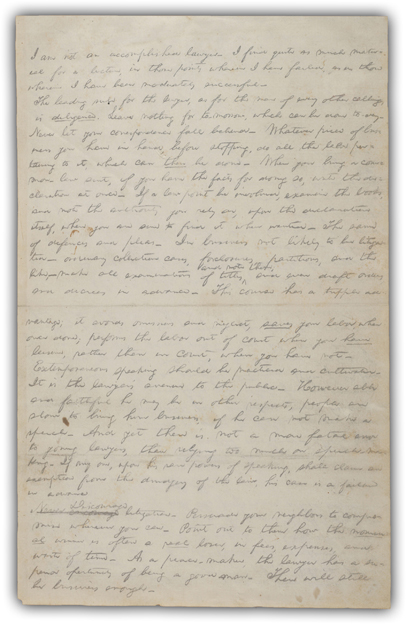

NOTES ON THE PRACTICE OF LAW, CA. 1850

Lincoln’s advice to aspiring attorneys—likely drafted to fit into a lecture he never finished or delivered— nicely embodies the diligence, moral rectitude, and common sense he exuded in his thirties and forties. (Excerpt)

I am not an accomplished lawyer. I find quite as much material for a lecture in those points wherein I have failed, as in those wherein I have been moderately successful. The leading rule for the lawyer, as for the man of every other calling, is diligence. Leave nothing for to-morrow, which can be done to-day. Never let your correspondence fall behind. Whatever piece of business you have in hand, before stopping, do all the labor pertaining to it which can then be done. When you bring a common-law suit, if you have the facts for doing so, write the declaration at once. If a law point be involved, examine the books, and note the authority you rely on, upon the declaration itself, where you are sure to find it when wanted. The same of defences and pleas. In business not likely to be litigated — ordinary collection cases, foreclosures, partitions, and the like — make all examinations of titles ^ and note them, and even draft orders and decrees in advance. This course has a triple advantage; it avoids omissions and neglect, saves your labor when once done, performs the labor out of court when you have leisure, rather than in court, when you have not. Extemporaneous speaking should be practiced and cultivated. It is the lawyer’s avenue to the public. However able and faithful he may be in other respects, people are slow to bring him business if he cannot make a speech. And yet there is not a more fatal error to young lawyers, than relying too much on speech-making. If any one, upon his rare powers of speaking, shall claim an exemption from the drudgery of the law, his case is a failure in advance.

Never encourage Discourage litigation. Persuade your neighbors to compromise whenever you can. Point out to them how the nominal winner is often a real loser, in fees, expenses, and waste of time. As a peacemaker the lawyer has a superior opertunity of being a good man. There will still be business enough.

Abraham Lincoln was a lawyer in Illinois before becoming president of the United States. His practice was that of a local lawyer with a wide variety of cases. His notes for advice to lawyers are as timely and wise today as when he wrote them in the 1850s. For example, his first piece of advice is to be “diligent” in preparation, even if the work is tedious. His second bit of advice to the lawyer is to “discourage litigation,” to try to be a peacemaker rather than one who stirs up litigation. Third, Mr. Lincoln wrote that “an exorbitant fee should never be claimed.” Finally, and most important, he advised that every lawyer must “resolve to be honest.” If “you cannot be an honest lawyer, resolve to be honest without being a lawyer.”

Lincoln’s advice can and should guide all lawyers today as well as those who aspire to practice law. There is no better way to honor this great man.

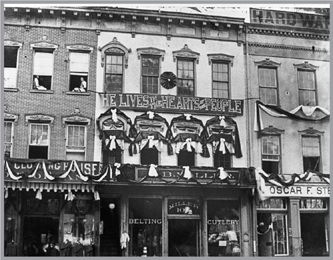

Lincoln’s earliest law office was a meagerly furnished room above the county courtroom in “Hoffman’s Row,” a new Springfield office building. Here a later legal office is draped in black in his memory.

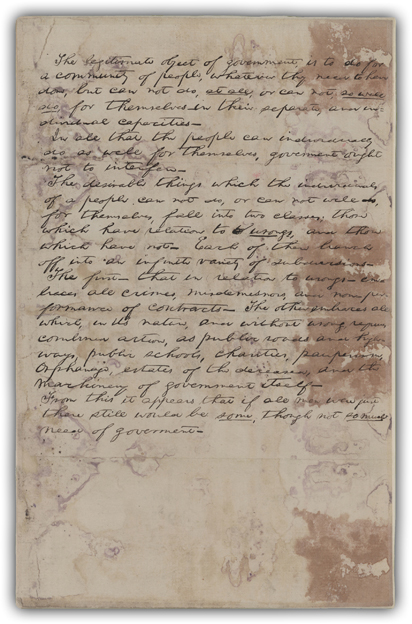

FRAGMENT ON THE OBJECT OF GOVERNMENT, CA. JULY 1854

Scholars remain uncertain as to why—or even precisely when—Lincoln composed this enduringly simple definition of the necessary role of government, but its author surely never suspected that politicians would be guided by it for generations to come.

The legitimate object of government, is to do for a community of people, whatever they need to have done, but can not do, at all, or can not, so well do, for themselves — in their separate, and individual capacities.

In all that the people can individually do as well for themselves, government ought not to interfere.

The desirable things which the individuals of a people can not do, or can not well do, for themselves, fall into two classes; those which have relation to to wrongs, and those which have not. Each of these branch off into an infinite variety of subdivisions.

The first — that in relation to wrongs — embraces all crimes, misdemeanors, and non-performance of contracts. The other embraces all which, in its nature, and without wrong, requires combined action, as public roads and highways, public schools, charities, pauperism, orphanages, estates of the deceased, and the machinery of government itself. From this it appears that if all men were just there still would be some, though not so much, need of government.

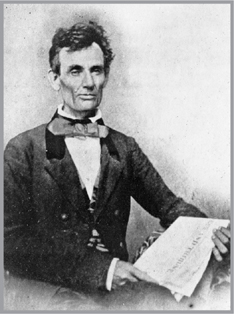

Lincoln proudly holds the pro-Republican Chicago Tribune—a staunch ally in the Republican struggle to redefine government—for this 1854 portrait by Chicago photographer Polycarpus von Schneidau.

Some of the most rancorous and least useful political debates revolve around the question of what precise role the government should play beyond the most obvious: to protect us from enemies who seek to injure or destroy the nation. Thus, those who call themselves conservatives are inclined to disparage government in general and “big” government in particular. That simplistic view ignores the best argument for the use of government, which is to advance the whole society’s well-being.

Perhaps Lincoln’s most valuable contribution to the debate was providing a cogent, plain-English formula for determining what specific functions government should undertake. Around 1854 he honed his credo and described the role of government with sparkling simplicity, comprehensiveness, and intelligence.

Lincoln could express himself in words that approached poetry. But even in basic prose, no one ever offered a more timeless argument for why Americans need a government that works.