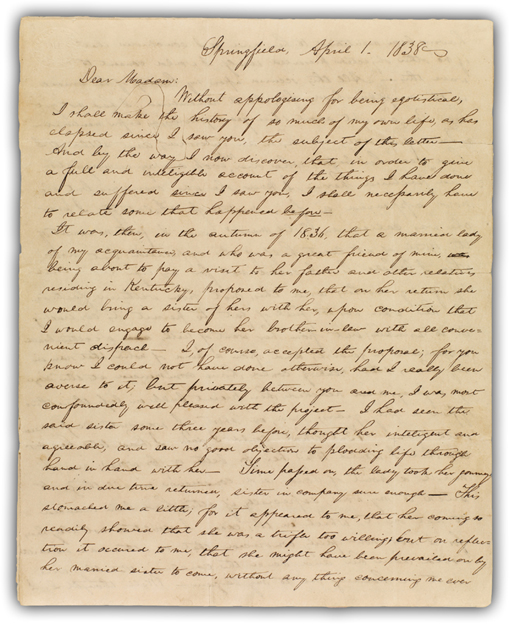

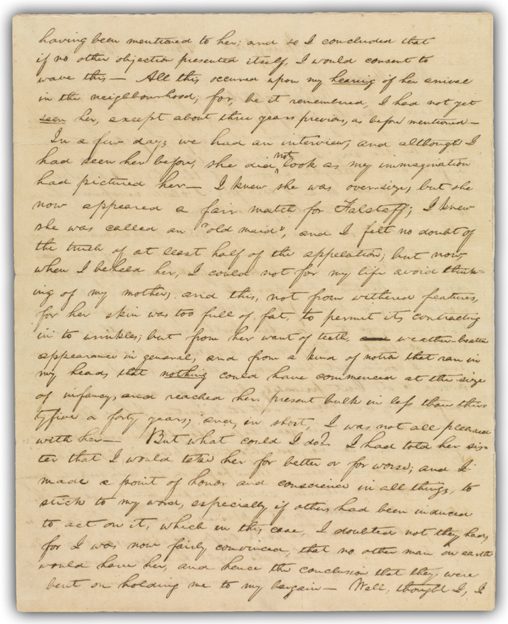

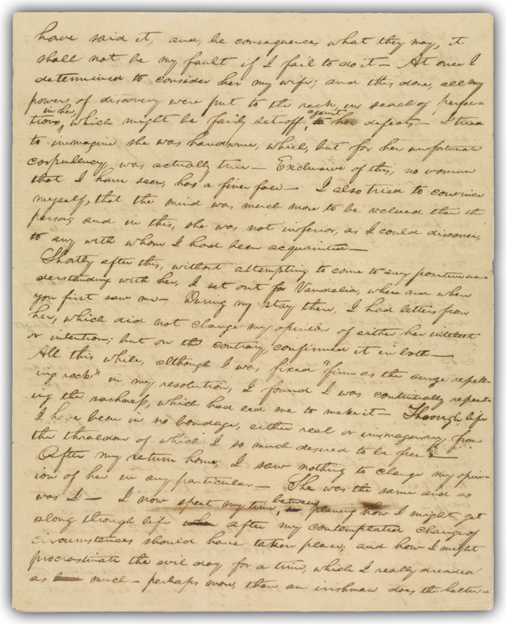

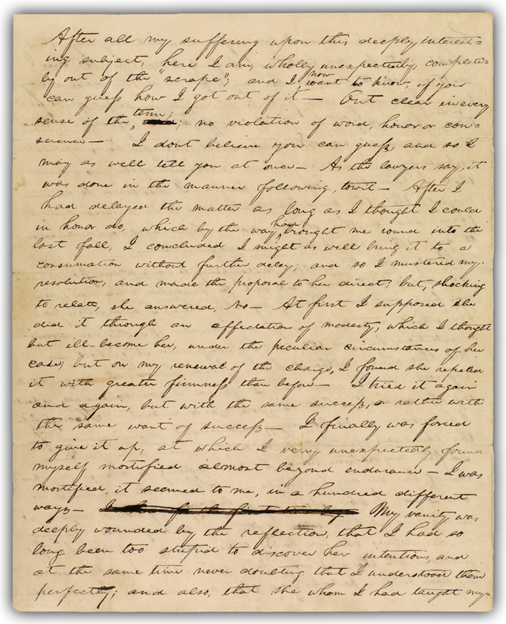

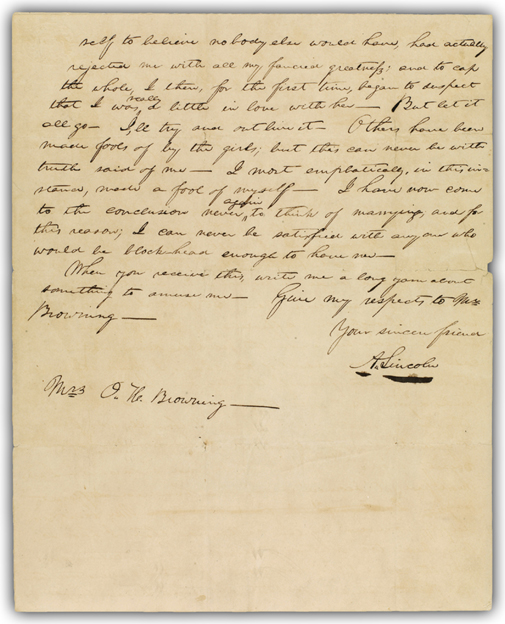

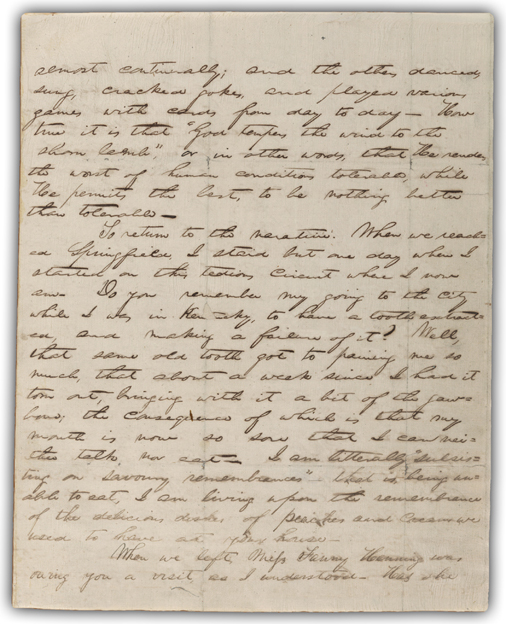

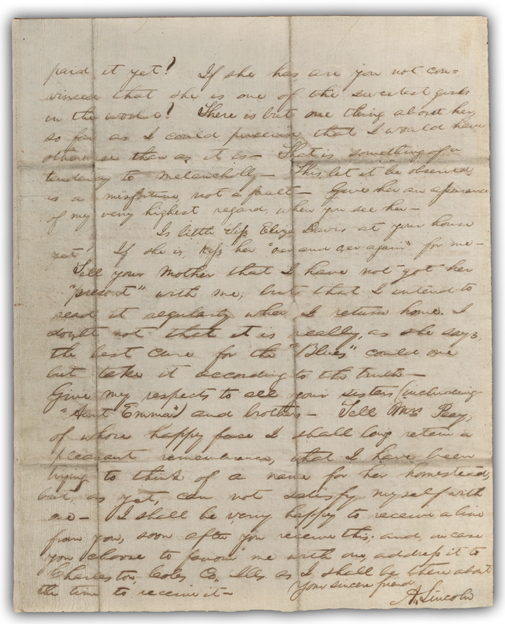

LETTER TO ELIZA BROWNING, APRIL 1, 1838

After a courtship gone badly awry with a young woman from Kentucky, Lincoln explained himself— and satirized the whole affair—in a letter to his friend Eliza Browning.

Click here to return to main text.

Click here to return to main text.

Click here to return to main text.

Click here to return to main text.

Click here to return to main text.

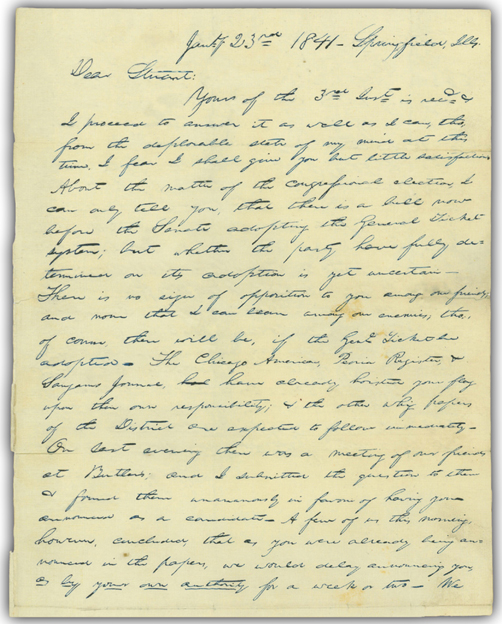

LETTER TO JOHN T. STUART, JANUARY 23, 1841

With his senior law partner at Congress in Washington, Lincoln was tasked to send regular updates on the political scene. But on this grim winter’s day, his mind was in such “deplorable” shape that his depression—perhaps the worst spell in a life of melancholy—became the main topic.

Click here to return to main text.

Click here to return to main text.

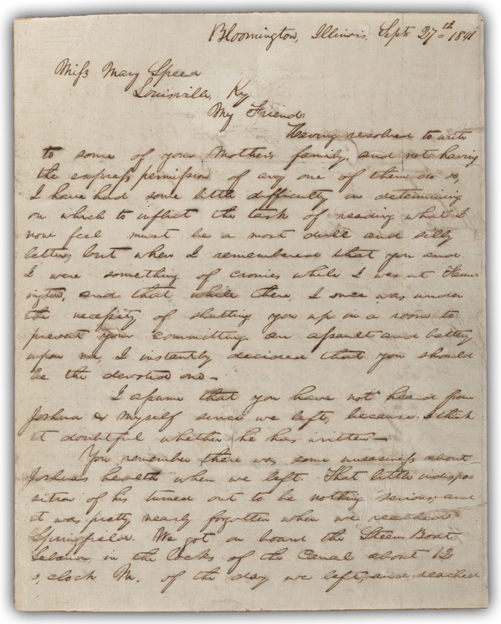

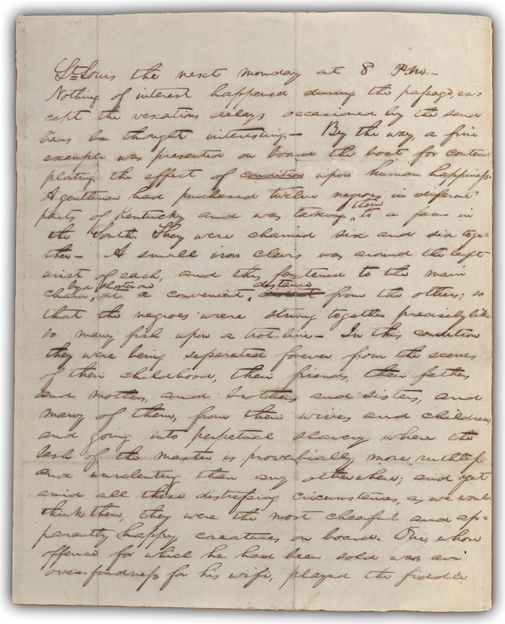

LETTER TO MARY SPEED, SEPTEMBER 27, 1841

Lincoln wrote to the half sister of his closest friend, Joshua Fry Speed, shortly after a long stay on their family estate in Louisville. His narration of an encounter with a group of shackled slaves on the Ohio River has long intrigued scholars, and fueled arguments on all sides.

Click here to return to main text.

Click here to return to main text.

Click here to return to main text.

Click here to return to main text.

LETTER TO ANDREW JOHNSTON, INCLUDING POEM, SEPTEMBER 6, 1846

An avid reader of poetry, Lincoln tried his hand at verse too. Here he sets up and delivers the second of a three-part effort to his literary friend Andrew Johnston, who would arrange to publish the lines in the Quincy Whig. Lincoln thought enough of his poem to allow publication— but asked that it be made anonymous.

Click here to return to main text.

Click here to return to main text.

Click here to return to main text.

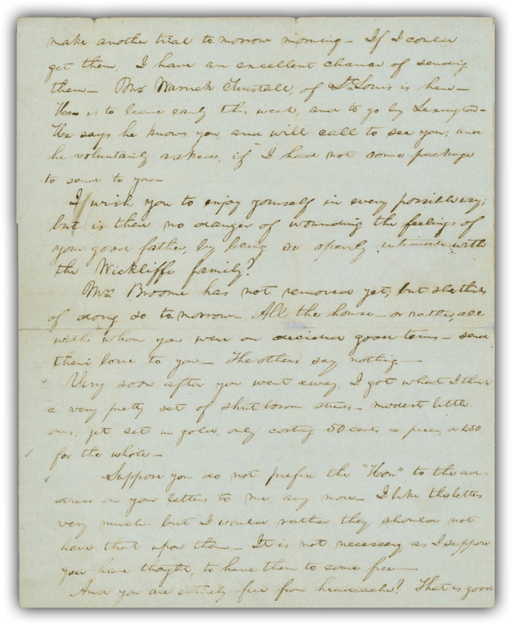

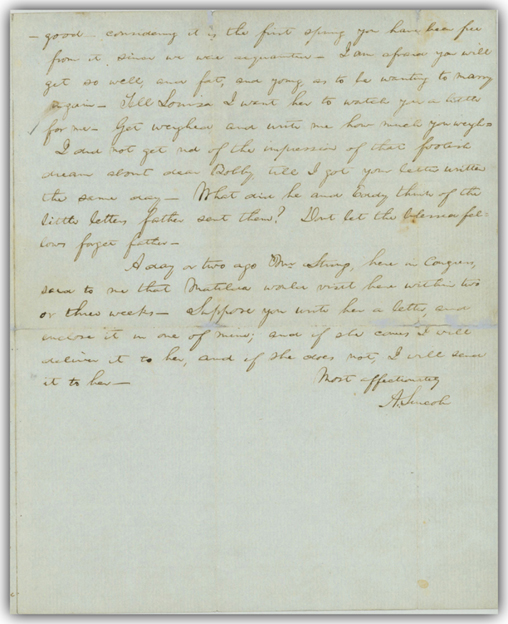

LETTER TO MARY LINCOLN, APRIL 16, 1848

Mary Lincoln accompanied her husband to Washington for his 1847–48 term in the U.S. House of Representatives. But she soon returned—with their two boys, Robert and Edward—to live with her family in Lexington, Kentucky, where Lincoln wrote her.

Click here to return to main text.

Click here to return to main text.

Click here to return to main text.

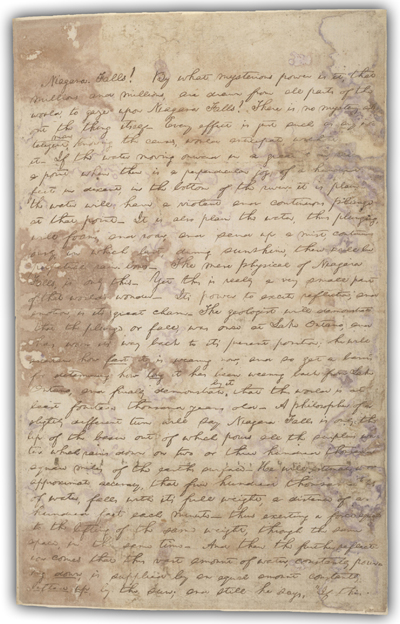

FRAGMENT ON NIAGARA FALLS, CA. SEPTEMBER 25–30, 1848

His political career on the skids after an unpopular stand against the Mexican–American War, Lincoln seems to have been considering a career on the lyceum circuit. This unfinished sketch on the mighty Niagara may have been intended as a draft for a public lecture.

Click here to return to main text.

Click here to return to main text.

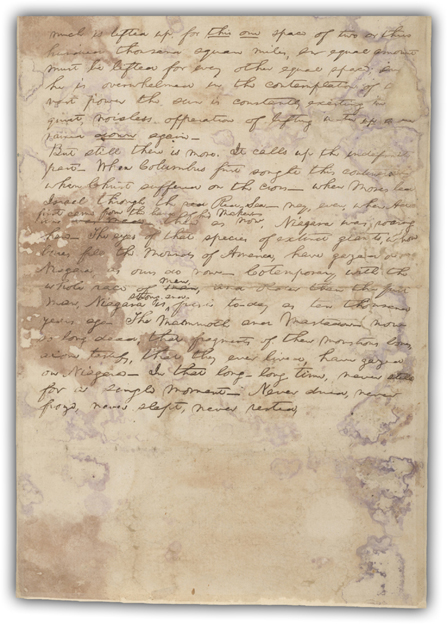

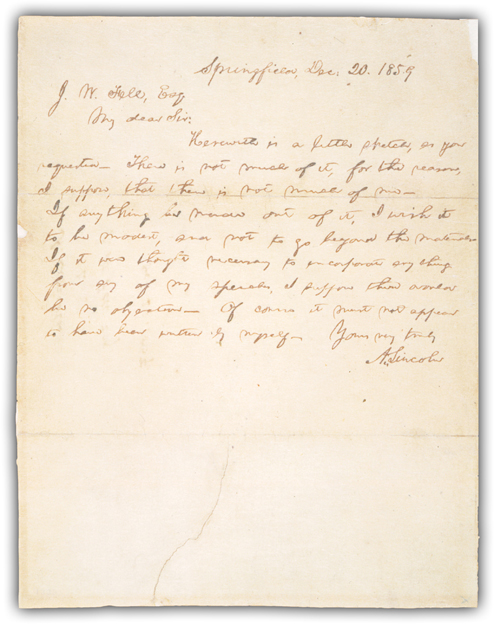

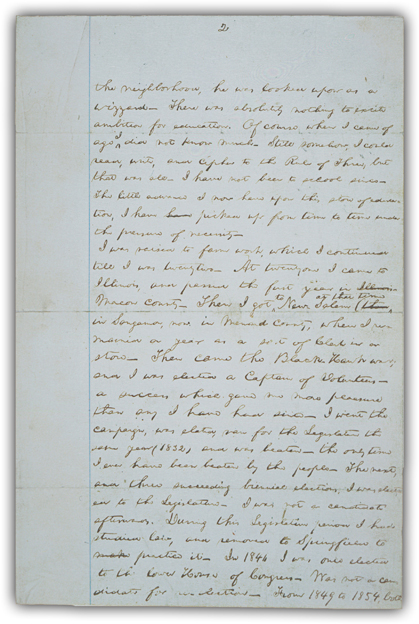

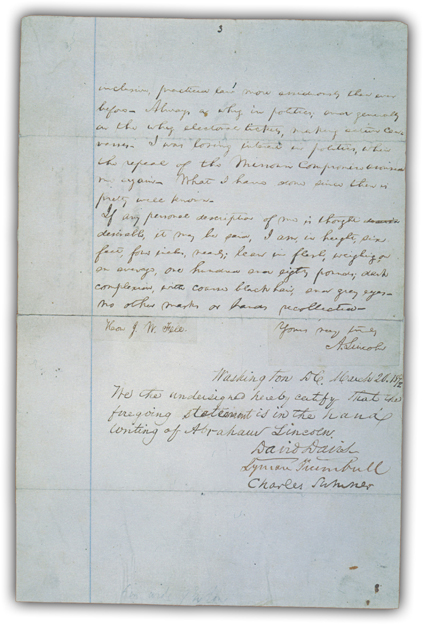

LETTER TO JESSE FELL, INCLUDING AUTOBIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH, DECEMBER 20, 1859

The candidate biography was as crucial to the nineteenth-century campaign as television ads are to the twenty-first. Lincoln’s friend Jesse Fell prevailed on him to provide this sketch, which Fell sent to a newspaperman in Pennsylvania. Notice, on the first page of the sketch, how Lincoln found the voice of the Indiana frontier when he revised “reading, writing, and Arithmetic” to “readin, writin, and cipherin.”

Click here to return to main text.

Click here to return to main text.

Click here to return to main text.

Click here to return to main text.

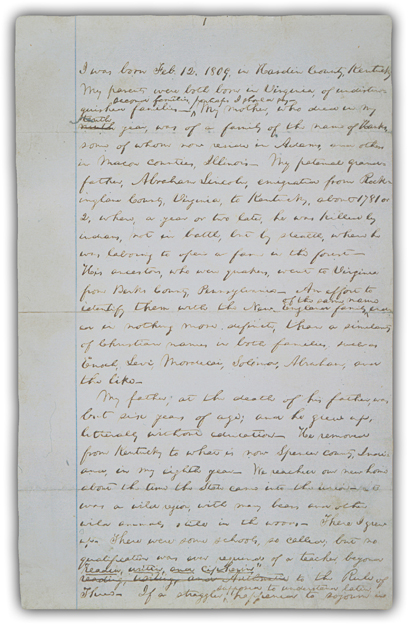

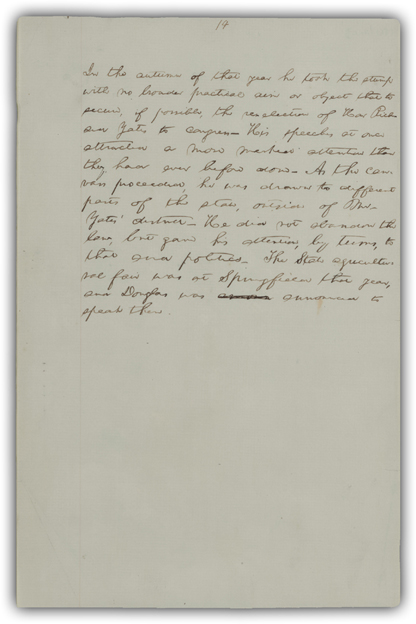

AUTOBIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH FOR THE CHICAGO TRIBUNE, JUNE 1860

A terse, private man, Lincoln also understood the power of his story. This, the most substantial memoir he ever wrote, aided his official campaign biographer in making the “railsplitter” from Illinois a national symbol of hard work and free labor. Here are the last two pages. (Excerpt)

Click here to return to main text.

Click here to return to main text.

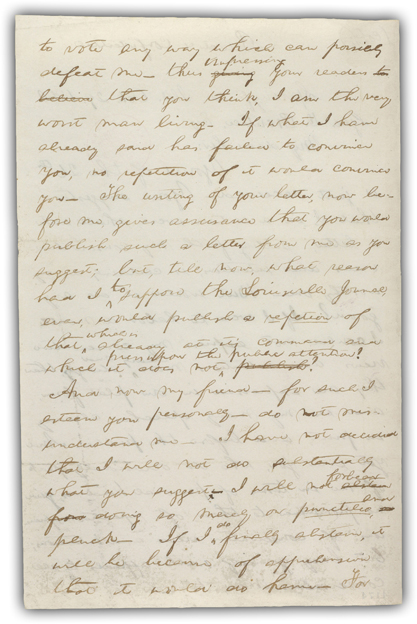

LETTER TO GEORGE D. PRENTICE, OCTOBER 29, 1860

Quite unlike modern campaigners, Lincoln spent his presidential campaign at home, where he largely stayed quiet. Having earlier labored to put his ideas into steadfast prose, Lincoln here refused a call to say more about the brewing crisis.

Click here to return to main text.

Click here to return to main text.

Click here to return to main text.

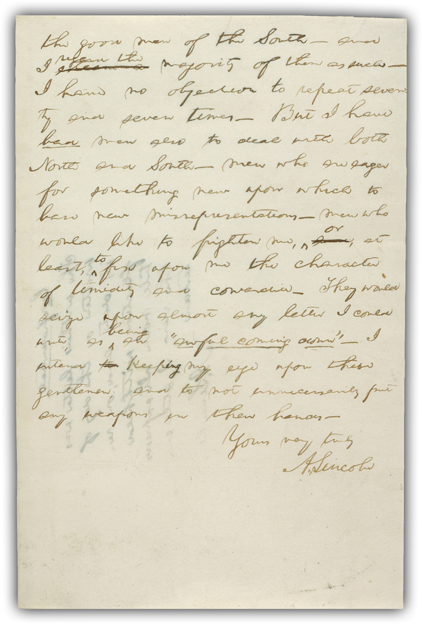

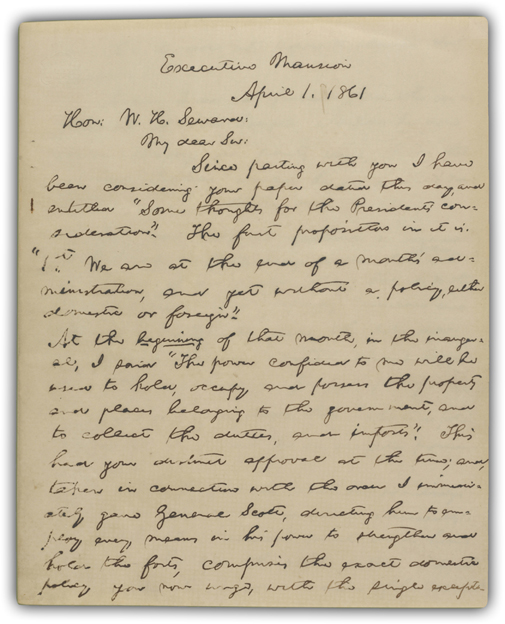

LETTER TO WILLIAM H. SEWARD, APRIL 1, 1861

Lincoln boldly appointed what historian Doris Kearns Goodwin called a “team of rivals” to fill his cabinet, but resisted when Secretary of State William H. Seward attempted to co-opt his authority. As the untested incoming president had confided earlier, “I can’t afford to let Seward take the first trick.”

Click here to return to main text.

Click here to return to main text.

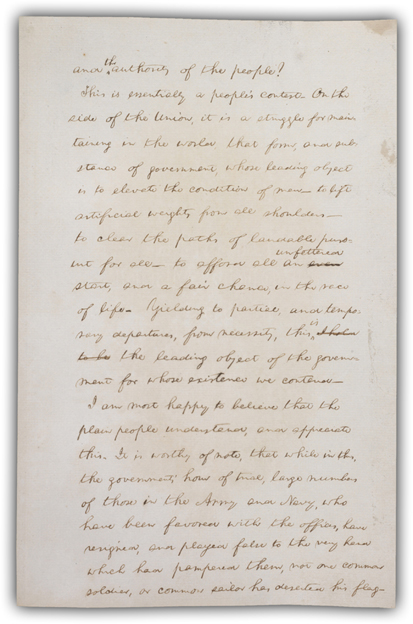

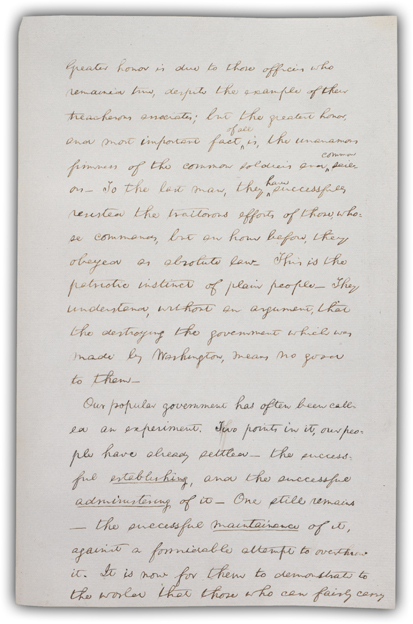

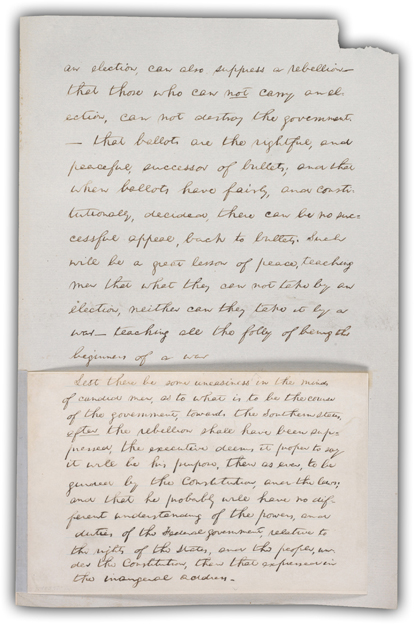

MESSAGE TO CONGRESS, JULY 4, 1861

Lincoln’s first crucial message to Congress—delivered to a special session called for Independence Day—marshaled the national will for war, and began an effort to define that war. “This is essentially a people’s contest,” he argued. Praised in the North, it convinced one Baltimore newspaper that Lincoln was “the equal, in despotic wickedness, of Nero.…” (Excerpt)

Click here to return to main text.

Click here to return to main text.

Click here to return to main text.

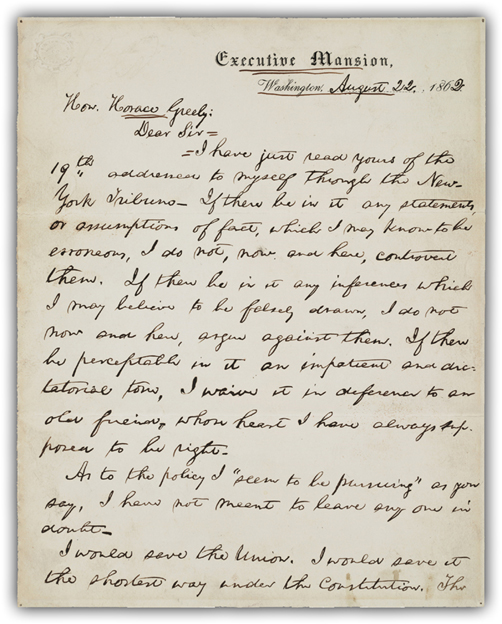

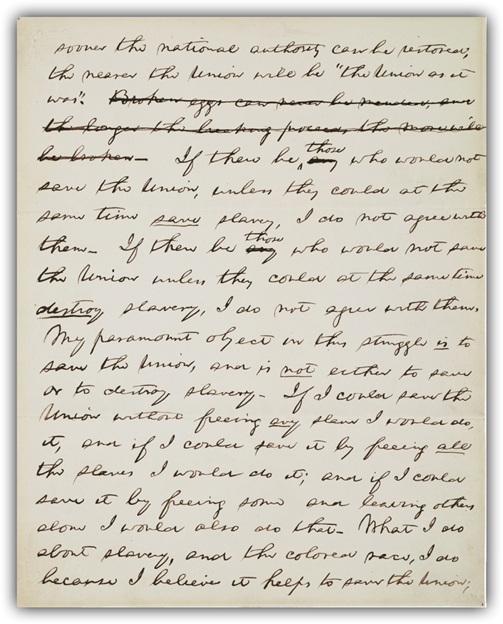

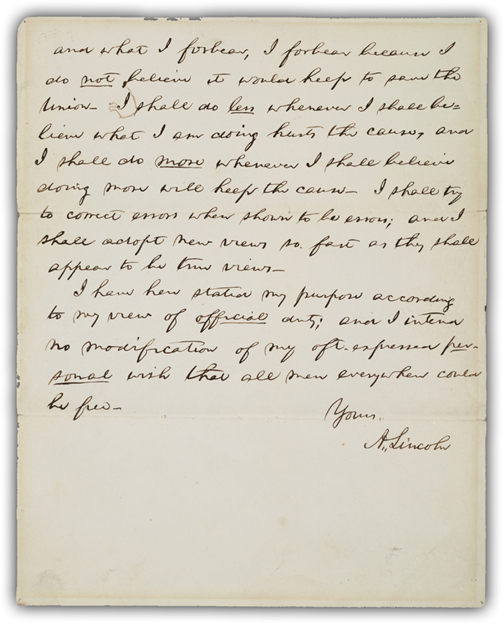

REPLY TO HORACE GREELEY’S EDITORIAL, AUGUST 22, 1862

Even after he had composed his Emancipation Proclamation, Lincoln publicly maintained—in this enigmatic reply to the irascible newspaperman Horace Greeley—his primary commitment to the preservation of the Union and the secondary consideration of slavery. This was, he said, his official duty, though not necessarily his personal wish.

Click here to return to main text.

Click here to return to main text.

Click here to return to main text.

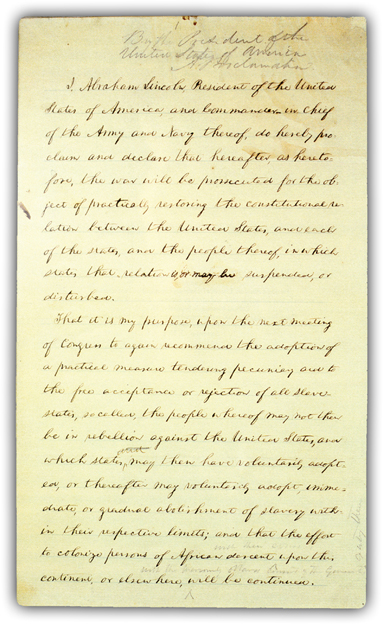

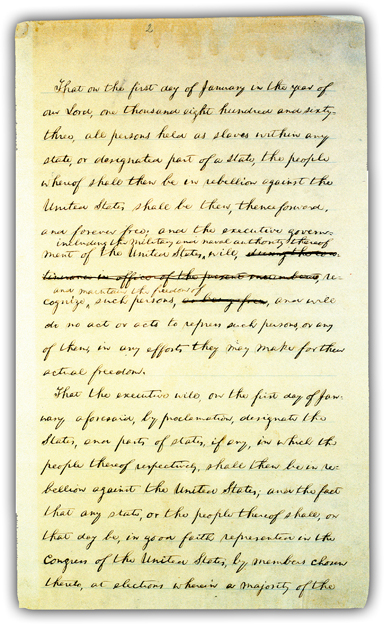

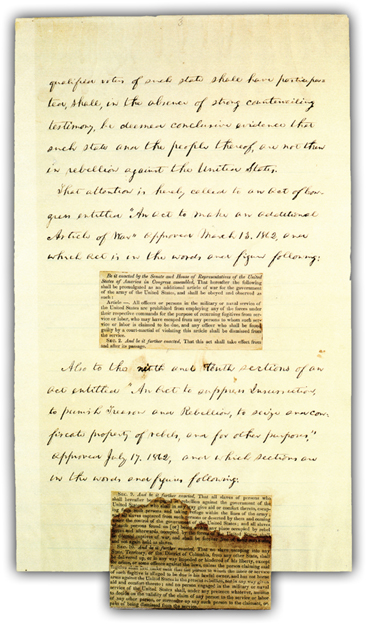

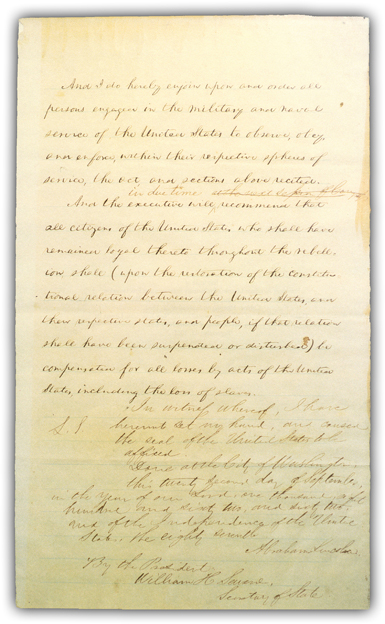

PRELIMINARY EMANCIPATION PROCLAMATION, SEPTEMBER 22, 1862

Lincoln wrote—and pasted together (one glued section seems to bear his fingerprint!)— this history-altering preliminary Emancipation Proclamation sometime in September 1862. Later donated to a New York charity fair, it was eventually acquired and preserved by the state. It is the only surviving copy of Lincoln’s most important document in his own hand; the manuscript of the final proclamation burned in the Chicago fire.

Click here to return to main text.

Click here to return to main text.

Click here to return to main text.

Click here to return to main text.

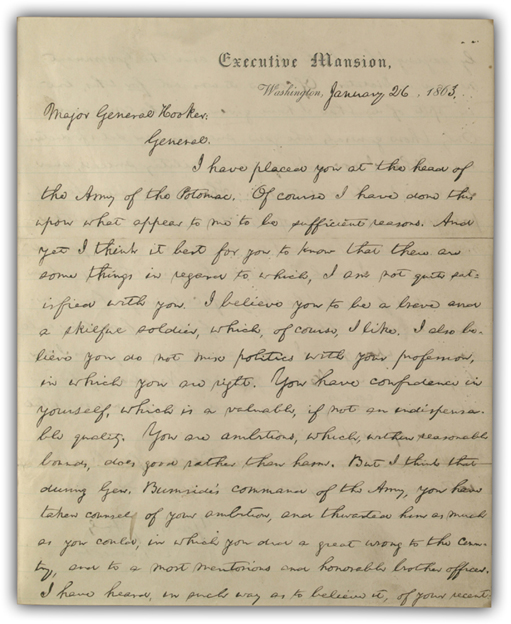

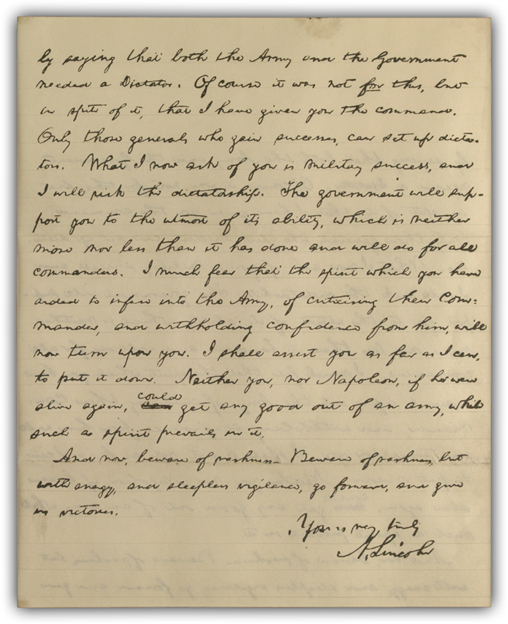

LETTER TO GEN. JOSEPH HOOKER, JANUARY 26, 1863

Lincoln appointed “Fighting Joe” Hooker to command the battered Army of the Potomac after the Union catastrophe at the Battle of Fredericksburg in December 1862. Hearing that his new general harbored Napoleonic delusions, the president accompanied the promotion with this extraordinary warning, tempered with words of encouragement. A few months later, Hooker led his forces into battle at Chancellorsville—and yet another defeat. Though he carried this note with him for years and thought it “beautiful … such a letter as a father might write to a son,” it was not made public until 1879.

Click here to return to main text.

Click here to return to main text.

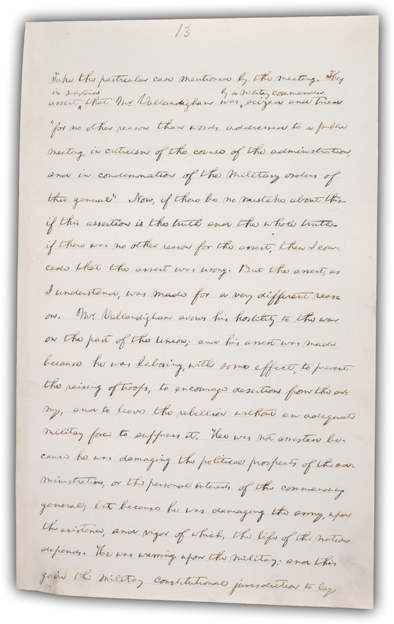

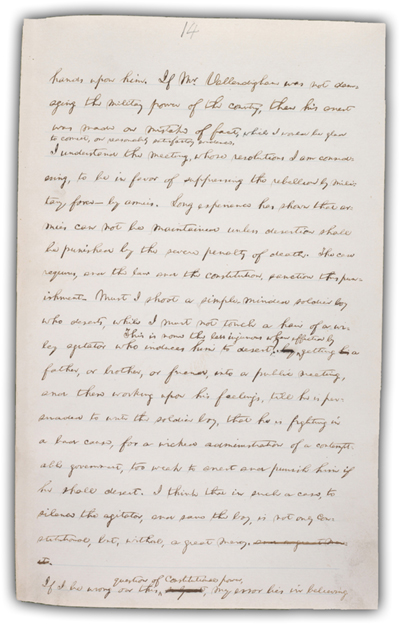

“ALBANY LETTER” TO ERASTUS CORNING ON CIVIL LIBERTIES, JUNE 12, 1863

Lincoln wrote the long letter from which this section is excerpted in reply to angry resolutions from New York Democrats in Albany, who condemned his suspension of the writ of habeas corpus. Widely published, the reply proved a tactical victory for Lincoln, though debate over a president’s constitutional authority in wartime has never ended. (Excerpt)

Click here to return to main text.

Click here to return to main text.

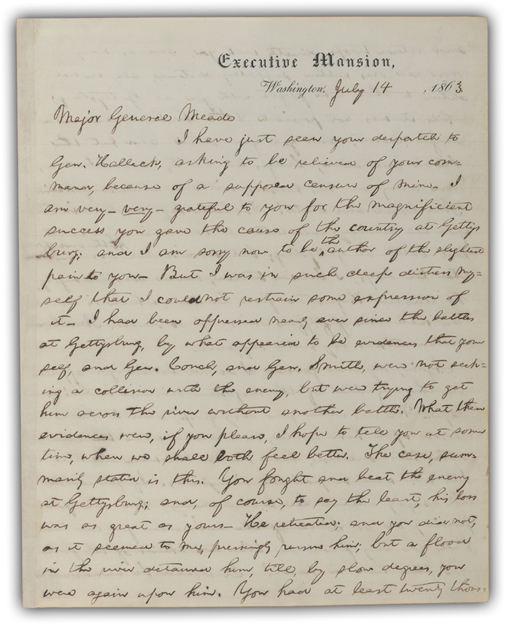

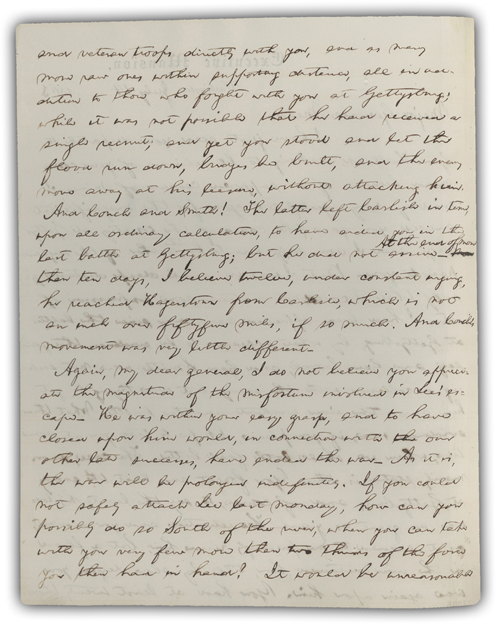

LETTER TO GEN. GEORGE G. MEADE, JULY 14, 1863

In despair over Meade’s failure to pursue Robert E. Lee’s army as it retreated south from Gettysburg, Lincoln vented his anger with this rebuke—tempered with praise for the recent Union victory—then thought better of it. The letter was “never sent, or signed.”

Click here to return to main text.

Click here to return to main text.

Click here to return to main text.

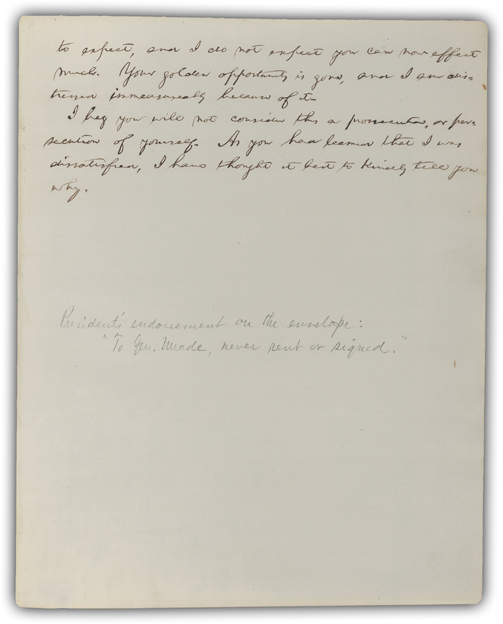

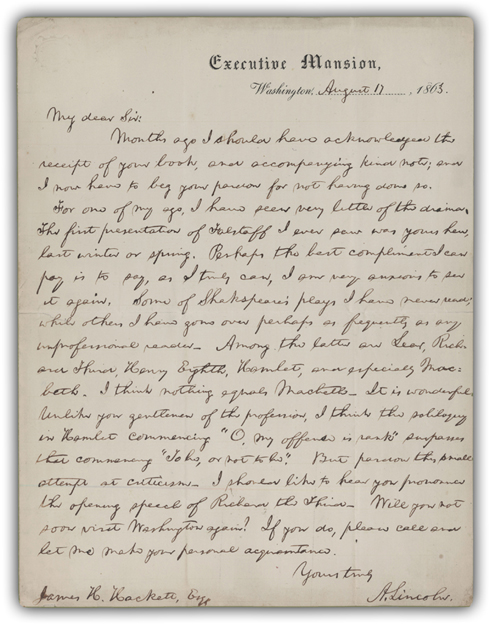

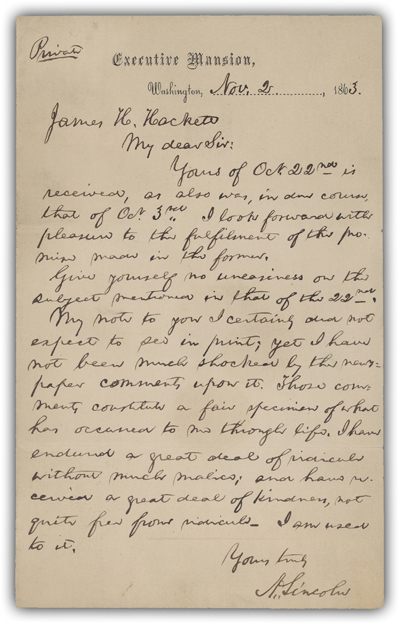

LETTERS TO JAMES HACKETT, AUGUST 17, 1863 AND NOVEMBER 2, 1863

Lincoln’s audacious but heartfelt comments on Shakespeare were leaked to the press by their recipient, actor James Hackett, and much mocked.

Click here to return to main text.

Click here to return to main text.

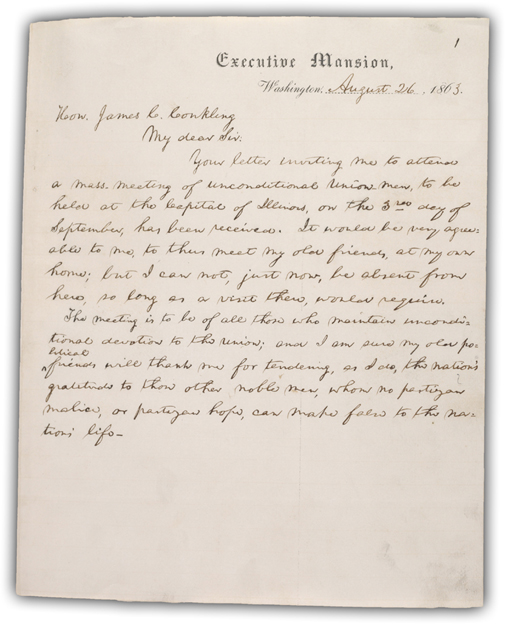

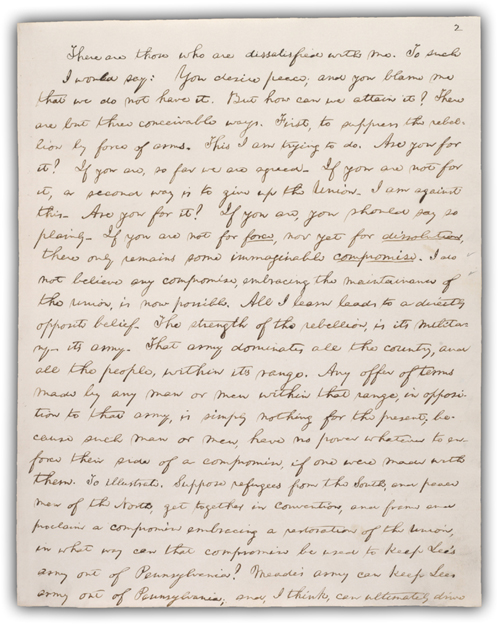

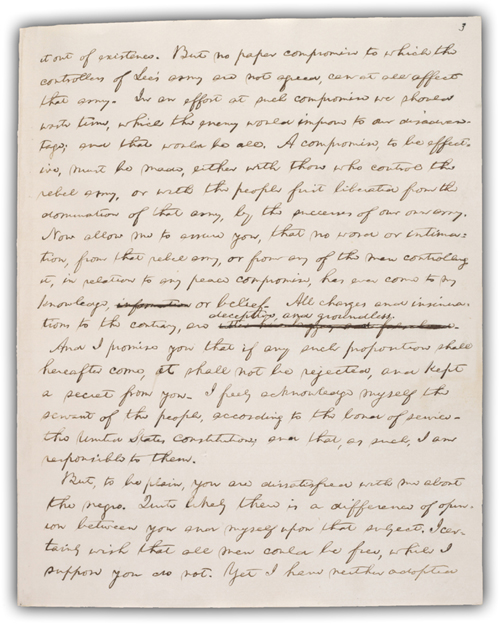

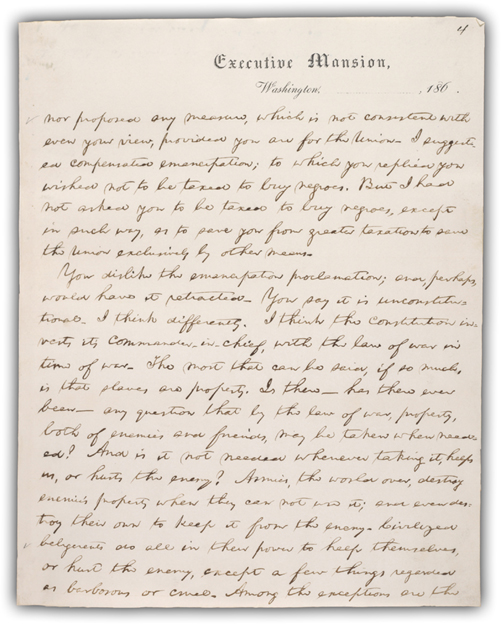

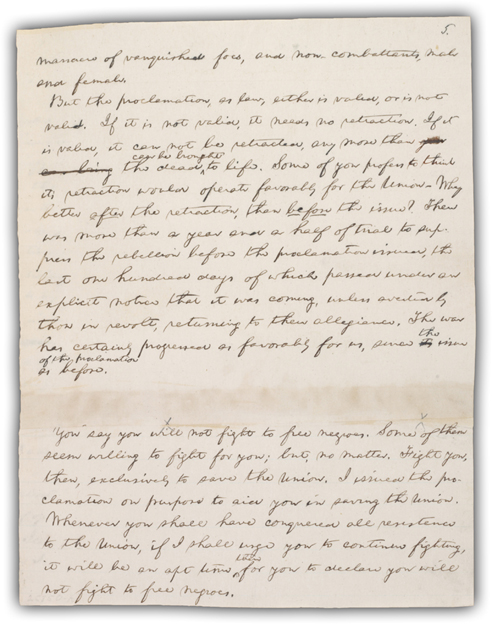

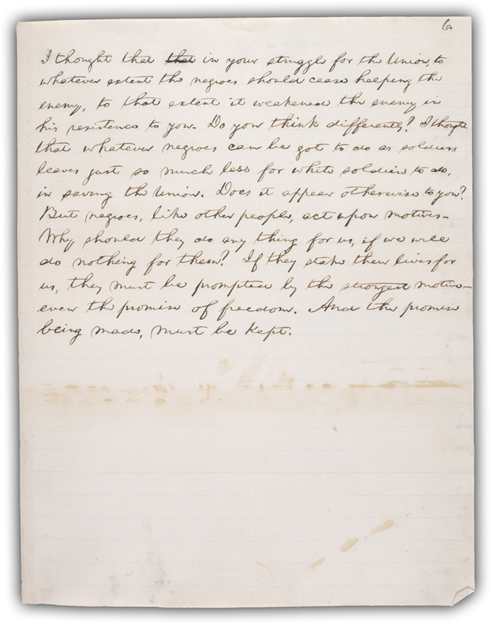

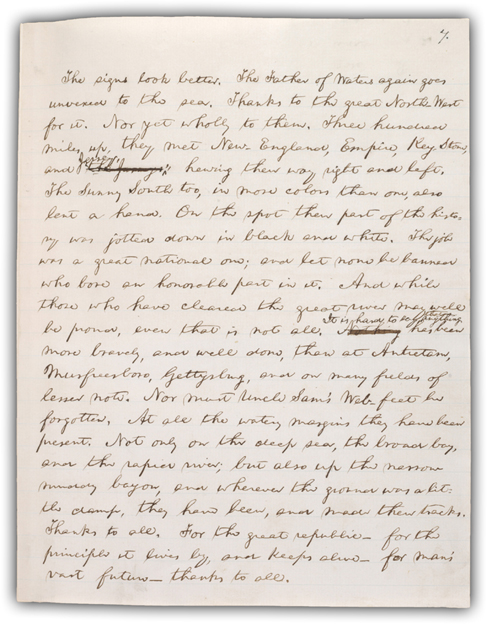

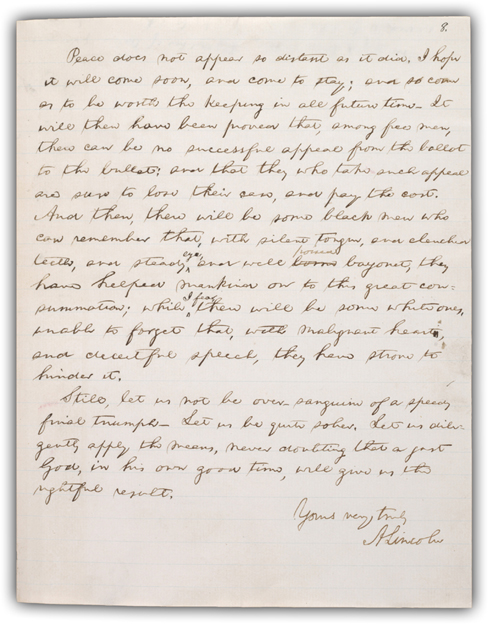

THE PUBLIC LETTER TO JAMES C. CONKLING, AUGUST 26, 1863

An invitation to a pro-Union rally inspired this extraordinary defense of emancipation and black enlistment. Lincoln wrote the letter as an oration to be read aloud by a surrogate, whom he instructed to speak “very slowly”— the way Lincoln himself delivered speeches.

Click here to return to main text.

Click here to return to main text.

Click here to return to main text.

Click here to return to main text.

Click here to return to main text.

Click here to return to main text.

Click here to return to main text.

Click here to return to main text.

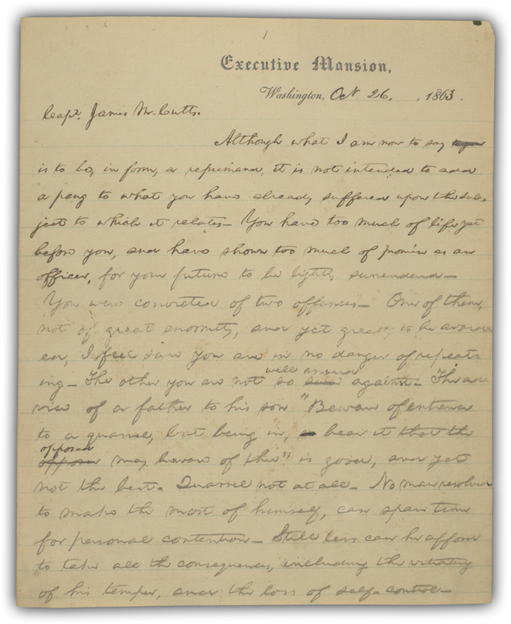

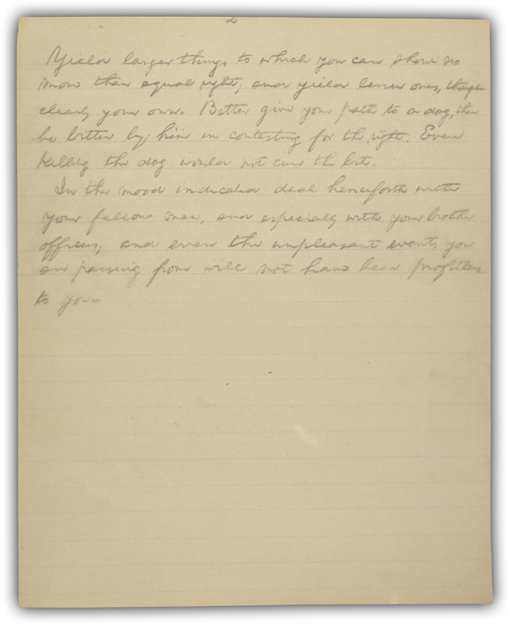

LETTER TO CPT. JAMES M. CUTTS, JR., OCTOBER 26, 1863

Ever loyal, and characteristically forgiving, the president clearly labored over this rarely cited gem of literature: advice to the brother-in-law of his late, longtime political enemy, Stephen A. Douglas, as the young man faced disheartening military discipline.

Click here to return to main text.

Click here to return to main text.

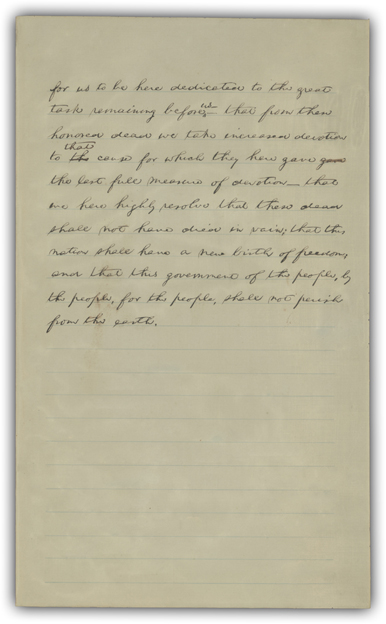

GETTYSBURG ADDRESS, NOVEMBER 19, 1863

What Lincoln said at Gettysburg is fixed like stone in American memory. But Lincoln’s words were far from fixed. Even after he delivered the speech, he continued to revise it, showing close attention to rhythm and nuance. This, the so-called Hay Copy, is probably the second draft. Historians remain unsure about which copy Lincoln actually read from, but the many drafts make it clear the president did not write the speech in haste on the train, as legend stubbornly insists.

Click here to return to main text.

Click here to return to main text.

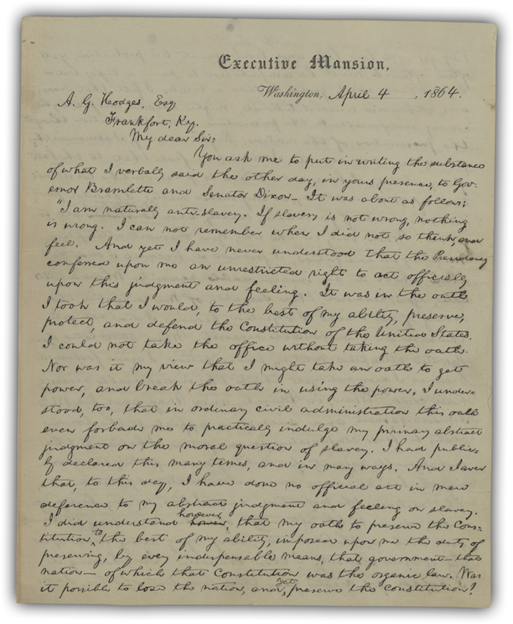

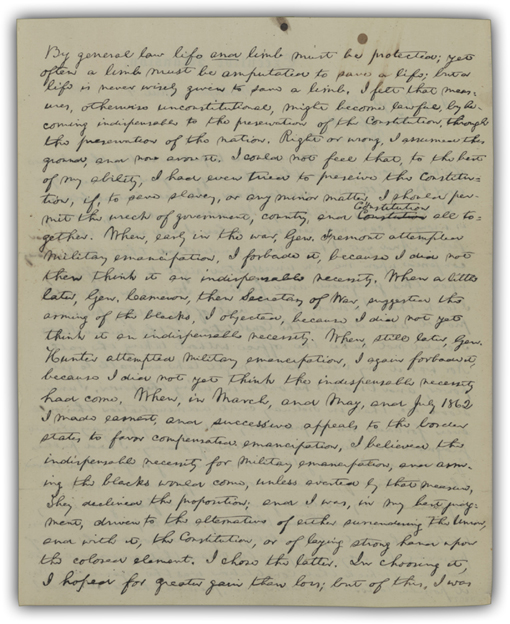

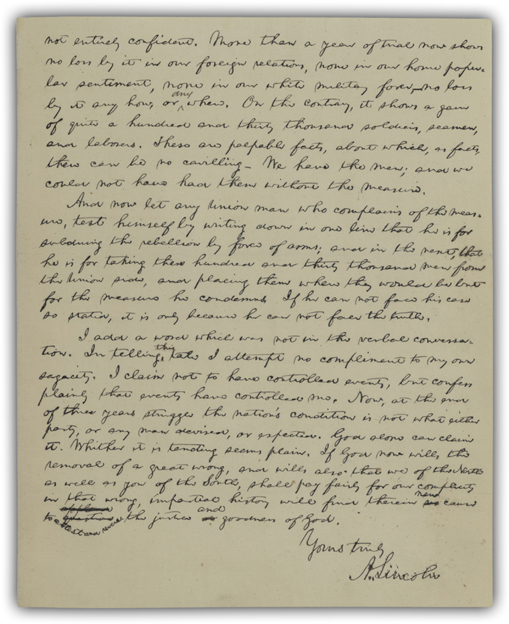

LETTER TO ALBERT HODGES, APRIL 4, 1864

In this careful letter, Lincoln narrated the history of his ideas and actions on American slavery. The letter combines a declaration of personal sentiments, a constitutional argument, and, in the end, a nervy theological claim.

Click here to return to main text.

Click here to return to main text.

Click here to return to main text.

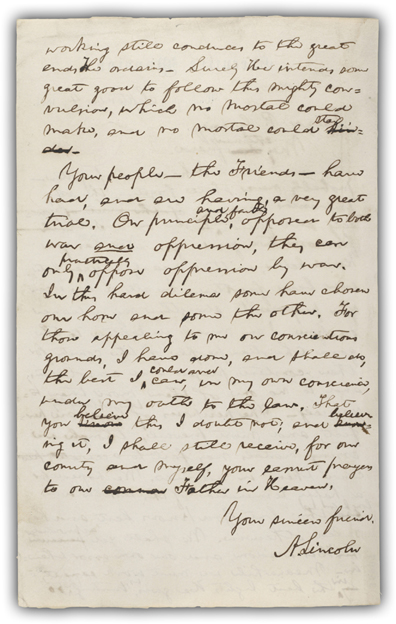

LETTER TO ELIZA P. GURNEY, SEPTEMBER 4, 1864

On September 4, Lincoln anticipated the mood and the theme of his Second Inaugural Address in a letter to the distinguished Quaker Eliza P. Gurney. The two had visited together and shared prayers “for wisdom on high” in 1862. Lincoln confided that day that he believed America was going through what he called “a fiery trial” willed by God.

Click here to return to main text.

Click here to return to main text.

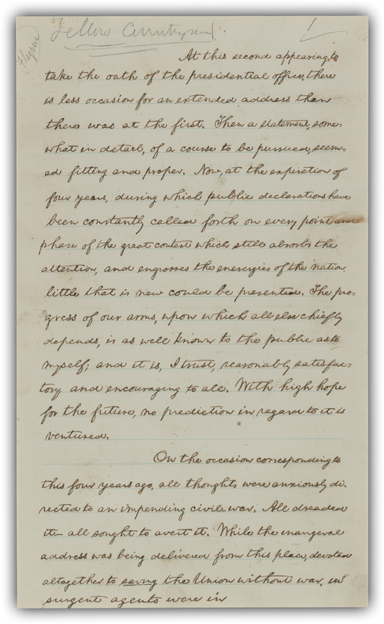

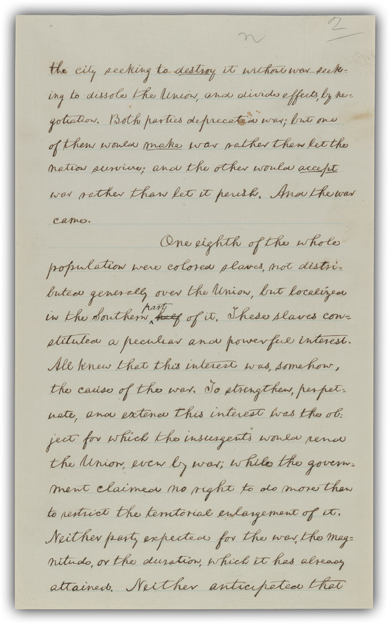

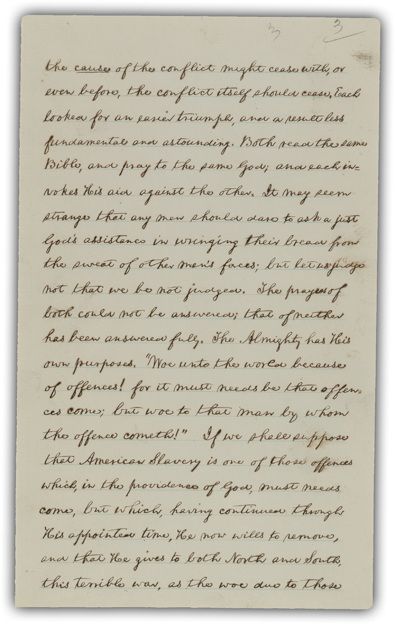

SECOND INAUGURAL ADDRESS, MARCH 4, 1865

“I expect it to wear,” Lincoln wrote of his Second Inaugural, “as well as—perhaps better than—any thing I have produced.” Recognizing that many would object to its invocation of divine retribution to explain the sufferings produced by the war, he shrugged: “It is a truth which I thought needed to be told.”

Click here to return to main text.

Click here to return to main text.

Click here to return to main text.

Click here to return to main text.