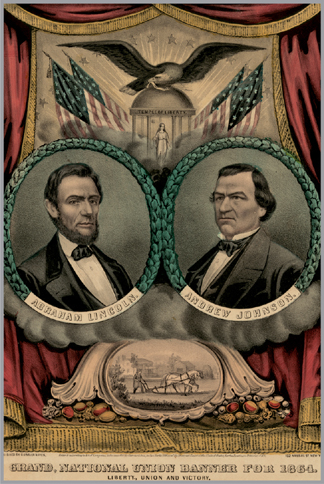

By the final years of his life—and creative output as a writer and speaker—Lincoln firmly won not only the validation of the electorate (with a handsome reelection victory), but also the respect of America’s leading authors. Even Walt Whitman and Herman Melville fell under his thrall.

This was the period of the Gettysburg Address and the Second Inaugural, two of the greatest masterpieces of American political oratory. Ironically, Lincoln initially fretted that both were failures. One friend insisted he feared Gettysburg “fell on the audience like a wet blanket.” And the president initially confided of his final inaugural, “It is not immediately popular,” explaining: “Men are not flattered by being shown that there has been a difference of purpose between the Almighty and them.”

But Lincoln quickly came to comprehend these triumphs. The day after he returned from Gettysburg, the day’s principal orator wrote to confess: “I should be glad, if I could flatter myself that I came as near to the central idea of the occasion, in two hours, as you did in two minutes.” And asked to render an opinion on his 1865 inaugural, Frederick Douglass cheered: “It is a sacred effort.” In four years, Lincoln’s words had evolved into American scripture.

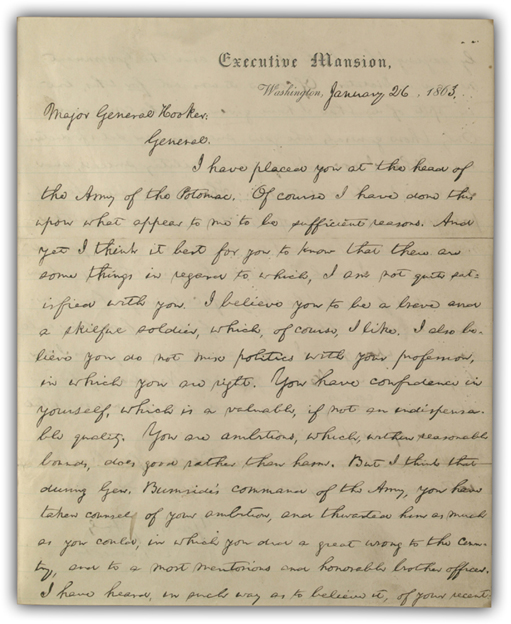

LETTER TO GEN. JOSEPH HOOKER, JANUARY 26, 1863

Lincoln appointed “Fighting Joe” Hooker to command the battered Army of the Potomac after the Union catastrophe at the Battle of Fredericksburg in December 1862. Hearing that his new general harbored Napoleonic delusions, the president accompanied the promotion with this extraordinary warning, tempered with words of encouragement. A few months later, Hooker led his forces into battle at Chancellorsville—and yet another defeat. Though he carried this note with him for years and thought it “beautiful … such a letter as a father might write to a son,” it was not made public until 1879.

Click here to see images of the full letter.

Washington, January 26, 1863.

Major General Hooker:

General,

I have placed you at the head of the Army of the Potomac. Of course I have done this upon what appears to me to be sufficient reasons. And yet I think it is best for you to know that there are some things in regard to which, I am not quite satisfied with you. I believe you to be a brave and a skilful soldier, which, of course, I like. I also believe you do not mix politics with your profession, in which you are right. You have confidence in yourself, which is a valuable, if not an indispensable quality. You are ambitious, which, within reasonable bounds, does good rather than harm. But I think that during Gen. Burnside’s command of the Army, you have taken counsel of your ambition, and thwarted him as much as you could, in which you did a great wrong to the country, and to a most meritorious and honorable brother officer. I have heard, in such way as to believe it, of your recently saying that both the Army and the Government needed a Dictator. Of course it was not for this, but in spite of it, that I have given you the command. Only those generals who gain successes, can set up dictators. What I now ask of you is military success, and I will risk the dictatorship. The government will support you to the utmost of it’s ability, which is neither more nor less than it has done and will do for all commanders. I much fear that the spirit which you have aided to infuse into the Army, of criticizing their commander, and withholding confidence from him, will now turn upon you. I shall assist you as far as I can, to put it down. Neither you, nor Napoleon, if he were alive again, can ^ could get any good out of an army, while such a spirit prevails in it.

And now, beware of rashness. Beware of rashness, but with energy, and sleepless vigilance, go forward, and give us victories.

Yours very truly

A. Lincoln

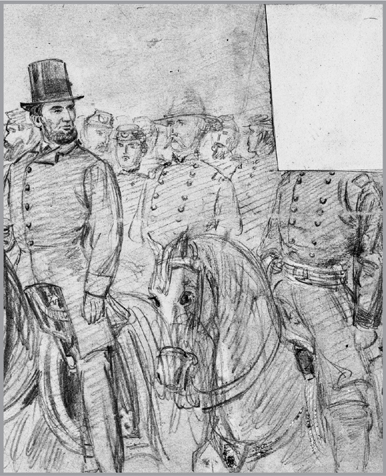

Lincoln and General Hooker (to his left, his head later cut from the picture) review the Army of the Potomac at its encampment near Falmouth, Virginia, in April 1863. One soldier thought the tall visitor, his long legs practically scraping the ground, “presented a very comical picture.” But in the words of another eyewitness, “that sad anxious face, so full of melancholy foreboding,” made ridicule impossible.

What? A dictatorship? In the United States? This idea seems unbelievable today. A commander in chief is in control of military as well as civil leadership. This is a given.

But it had not been a given in much of humanity over the history of time. The United States tried to create a better world at the end of the eighteenth century. Then the American Civil War produced new problems. By 1863 many Americans thought their government had been defeated. Among others, one of the most popular Union generals, “Fighting Joe” Hooker, announced that the government was “imbecile.” What the people needed was a “dictator, and the sooner the better.” Some people took the general’s comments seriously, as did others before. Though Lincoln believed Hooker to be a hothead, the president also believed that the general was the best man for the time. Lincoln appointed him. At the same time, he also wrote one of his most blunt personal letters to Hooker. The president understood that some generals needed to grow up.

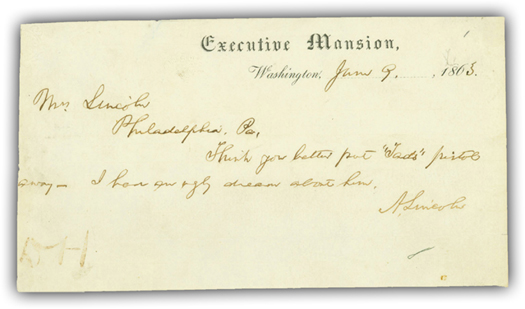

TELEGRAM TO MARY LINCOLN, JUNE 9, 1863

President Lincoln was a fixture at the telegraph office in Washington, where the latest technology kept him engaged with his generals in the field. On the morning of June 9, he had another kind of urgent message—to his wife, about his ten-year-old son, Thomas “Tad” Lincoln.

Washington, June 9, 1863.

Mrs. Lincoln

Philadelphia, Pa.

Think you better put “Tad’s” pistol away. I had an ugly dream about him.

A. Lincoln

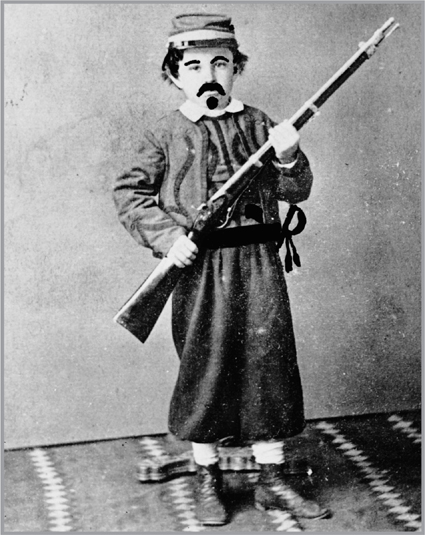

As his worried father knew, Tad Lincoln loved uniforms, swords, and guns. The youngster not only posed for this photograph wearing a custom-made soldier’s suit and toting a miniature rifle; he elaborated on it by inking in a manly goatee. His parents kept the comical result in their family album.

Lincoln paid serious attention to the portents his dreams might be carrying. After the death of his son Willie, he was even more likely to ponder any nightmare involving harm to (or done by?) Tad, his elfin, rambunctious, and overindulged ten-year-old. Whatever the precise nature of Lincoln’s dream about the pistol, its urgency prompted the president to compose this note for the operator of the military telegraph, who dispatched its gentle suggestion to the First Lady while she traveled with Tad in Philadelphia.

How odd that this boy, thus protected from his own pistol, should two years later assist in the giving of a speech that hastened his father’s death by John Wilkes Booth’s derringer. Three nights before the assassination, Tad accompanied Lincoln to an open window of the White House, from which the president delivered remarks envisioning suffrage for a portion of the freed slaves. “Now, by God, I’ll put him through,” declared Booth, standing with one of his co-conspirators among the listeners. As Lincoln finished reading the loose pages of his text, he allowed each one to fall from his hand. Tad made a game of catching them before they could hit the ground.

“ALBANY LETTER” TO ERASTUS CORNING ON CIVIL LIBERTIES, JUNE 12, 1863

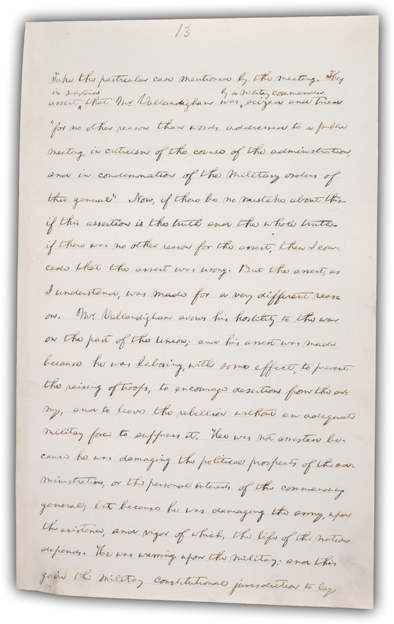

Lincoln wrote the long letter from which this section is excerpted in reply to angry resolutions from New York Democrats in Albany, who condemned his suspension of the writ of habeas corpus. Widely published, the reply proved a tactical victory for Lincoln, though debate over a president’s constitutional authority in wartime has never ended. (Excerpt)

Click here to see images of the full letter.

Take the particular case mentioned by the meeting. They assert ^ in substance that Mr. Vallandigham was ^ by a military commander, seized and tried “for no other reason than words addressed to a public meeting, in criticism of the course of the administration, and in condemnation of the military orders of that general” Now, if there be no mistake about this — if this assertion is the truth and the whole truth — if there was no other reason for the arrest, then I concede that the arrest was wrong. But the arrest, as I understand, was made for a very different reason. Mr. Vallandigham avows his hostility to the war on the part of the Union; and his arrest was made because he was laboring, with some effect, to prevent the raising of troops, to encourage desertions from the army, and to leave the rebellion without an adequate military force to suppress it. He was not arrested because he was damaging the political prospects of the administration, or the personal interests of the commanding general; but because he was damaging the army, upon the existence, and vigor of which, the life of the nation depends. He was warring upon the military; and this gave the military constitutional jurisdiction to lay hands upon him. If Mr. Vallandigham was not damaging the military power of the country, then his arrest was made on mistake of fact, which I would be glad to correct, on reasonably satisfactory evidence. I understand the meeting, whose resolutions I am considering, to be in favor of suppressing the rebellion by military force — by armies. Long experience has shown that armies can not be maintained unless desertion shall be punished by the severe penalty of death. The case requires, and the law and the constitution, sanction this punishment. Must I shoot a simple-minded soldier boy who deserts, while I must not touch a hair of a wiley agitator who induces him to desert? by ^ This is none the less injurious when effected by getting his a father, or brother, or friend, into a public meeting, and there working upon his feelings, till he is persuaded to write the soldier boy, that he is fighting in a bad cause, for a wicked administration of a contemptable government, too weak to arrest and punish him if he shall desert. I think that in such a case, to silence the agitator, and save the boy, is not only constitutional, but, withal, a great mercy. and a great merit.

If I be wrong on this subject, ^ question of Constitutional power, subject, my error lies in believing

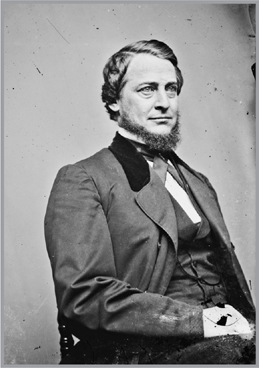

Clement Laird Vallandigham, the antiwar Ohio politician whose arrest, military trial for treason, and banishment to the Confederacy inspired Albany Democrats to rebuke Lincoln—in turn provoked the president’s response to Erastus Corning.

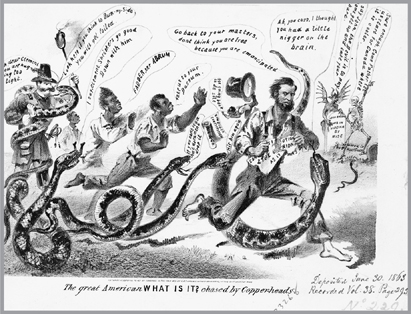

A bedraggled Lincoln defiantly shreds the Constitution as he flees from “Copperhead” snakes out to avenge Vallandigham. In the background, one of the reptiles chokes General Ambrose Burnside, who had ordered “Valiant Val’s” seizure. This cartoon was copyrighted just two weeks after Lincoln issued his letter to Corning.

The task of shaping public opinion was not easy, and Lincoln’s view of the proprieties of his office did not make it easier. He followed his predecessors in refraining from making public addresses while in the White House. “In my present position,” he told a crowd in 1862, eager to hear his plans and hopes, “it is hardly proper for me to make speeches.” But in a series of magnificent public letters, which were carried in nearly every important newspaper in the country, he made it clear that he had become not merely a president who presided over the usual transactions of government, but a transforming leader who was changing the very nature of discourse about the war. In this letter, written in June 1863, in reply to the protests of New York Democratic politicians over the suspension of habeas corpus and, in particular, over the arrest of Congressman Clement L. Vallandigham for inciting resistance to the draft, he offers a carefully reasoned defense of his decision to invoke the war power to act for the public good. Then he asks, in language that any reader could understand: “Must I shoot a simple-minded soldier boy who deserts, while I must not touch the hair of a wiley agitator who induces him to desert?” Thus in twenty-five words Lincoln summarized one of the most difficult problems the leader of a democratic society must face: how to reconcile liberty and order.

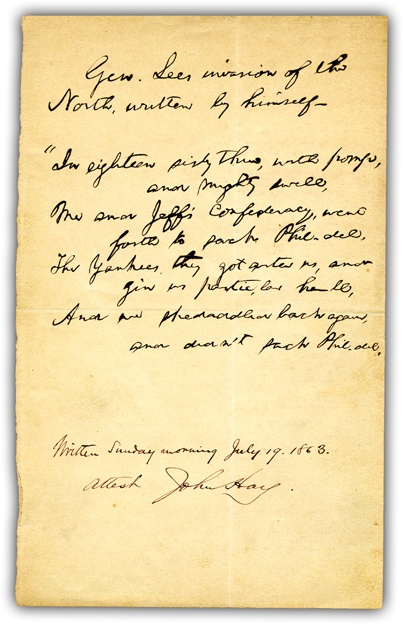

VERSE ON LEE’S INVASION OF THE NORTH, JULY 19, 1863

“The Tycoon is in very good humor,” White House secretary John Hay wrote in his diary on July 19, 1863. That day, a jubilant Lincoln scribbled this irreverent verse to mark the recent Union triumph at Gettysburg. Lost for nearly a century, it was rediscovered in Hay’s papers in the 1960s.

North, written by himself.

“In eighteen sixty three, with pomp,

and mighty swell,

Me and Jeff’s Confederacy, went

forth to sack Phil-del.

The Yankees they got arter us, and

giv us particlar hell,

And we skedaddled back again,

and didn’t sack Phil-del.

Written Sunday morning July 19. 1863.

attest John Hay.

As further evidence of Lincoln’s jolly mood after the Union triumph at Gettysburg, he owned this carte-de-visite cartoon showing Jefferson Davis pondering his ruination.

Lincoln’s doggerel about Lee’s defeat at Gettysburg and retreat from Pennsylvania is characteristic of Lincoln’s passion for humor and use of poetry. Lincoln routinely opened his cabinet meetings with humor. All his life he had used humor to entertain people on the court circuit as a lawyer and as a campaigner.

Lincoln collected humorous stories, read most of the famous humorists of his time (their version of The Tonight Show as a weekly column), and gathered funny stories and funny insights.

From the time he studied the Bible and Shakespeare, Lincoln became fascinated with words and how they could be strung together to evoke images, emotions, and insights.

Lincoln is the greatest wordsmith to have occupied the White House. That ability came from a constant fascination with language and a constant playing with ideas. He collected scraps of paper on which he wrote different thoughts and insights. His Second Inaugural Address in March 1865 grew out of notes made in August 1862.

These patterns of humor, poetry, wordsmithery, and constant thought come together in this expression of glee that Lee’s audacious gamble had been defeated and the seemingly ever-victorious Army of Northern Virginia had been proven capable of defeat.

Combined with the victory at Vicksburg the same week, Lincoln suddenly had a lot to be excited and happy about. A humorous doggerel was a good device for him to let some of that joy out without risking public exposure.

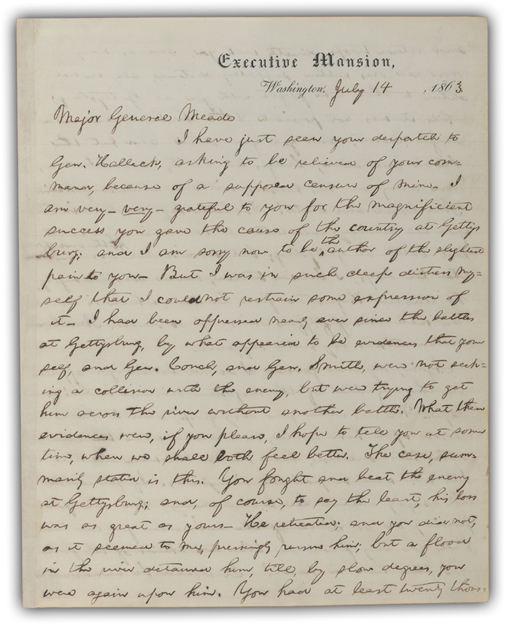

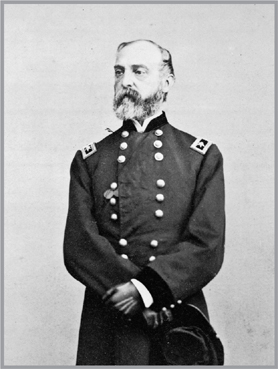

LETTER TO GEN. GEORGE G. MEADE, JULY 14, 1863

In despair over Meade’s failure to pursue Robert E. Lee’s army as it retreated south from Gettysburg, Lincoln vented his anger with this rebuke—tempered with praise for the recent Union victory—then thought better of it. The letter was “never sent, or signed.”

Click here to see images of the full letter.

Washington, July 14, 1863.

Major General Meade

I have just seen your despatch to Gen. Halleck, asking to be relieved of your command, because of a supposed censure of mine. I am very — very — grateful to you for the magnificient success you gave the cause of the country at Gettys burg; and I am sorry now to be ^ the author of the slightest pain to you. But I was in such deep distress myself that I could not restrain some expression of it. I had been oppressed nearly ever since the battles at Gettysburg, by what appeared to be evidences that your self, and Gen. Couch, and Gen. Smith, were not seeking a collision with the enemy, but were trying to get him across the river without another battle. What these evidences were, if you please, I hope to tell you at some time, when we shall both feel better. The case, summarily stated is this. You fought and beat the enemy at Gettysburg; and, of course, to say the least, his loss was as great as yours. He retreated; and you did not, as it seemed to me, pressingly pursue him; but a flood in the river detained him, till, by slow degrees, you were again upon him. You had at least twenty thousand veteran troops directly with you, and as many more raw ones within supporting distance, all in addition to those who fought with you at Gettysburg; while it was not possible that he had received a single recruit; and yet you stood and let the flood run down, bridges be built, and the enemy move away at his leisure, without attacking him.

General George G. Meade led Union troops to victory at Gettysburg after less than a week in command of the army, but aroused Lincoln’s wrath anyway for failing to pursue Lee’s Confederates.

And Couch and Smith! The latter left Carlisle in time, upon all ordinary calculation, to have aided you in the last battle at Gettysburg; but he did not arrive. More At the end of more than ten days, I believe twelve, under constant urging, he reached Hagerstown from Carlisle, which is not an inch over fiftyfive miles, if so much. And Couch’s movement was very little different.

Again, my dear general, I do not believe you appreciate the magnitude of the misfortune involved in Lee’s escape. He was within your easy grasp, and to have closed upon him would, in connection with the our other late successes, have ended the war. As it is, the war will be prolonged indefinitely. If you could not safely attack Lee last monday, how can you possibly do so South of the river, when you can take with you very few more than two thirds of the force you then had in hand? It would be unreasonable to expect, and I do not expect you can now effect much. Your golden opportunity is gone, and I am distressed immeasureably because of it.

I beg you will not consider this a prossecution, or persecution of yourself. As you had learned that I was dissatisfied, I have thought it best to kindly tell you why.

President’s endorsement on the envelope:

“To Gen. Meade, never sent, or signed.”

Lincoln’s turbulent emotional depths and his bracingly unencumbered rationality form one of the paradoxes that make him inexhaustibly interesting. Both are present in the Meade letter, which offers a privileged glimpse into the way these coexisted in his complicated soul.

The lucidity of the letter is characteristic of the president’s close attention to the conduct of the war, his coolly precise tactical understanding, informed and finely detailed. It’s the clarity that William Herndon, his law partner, called Lincoln’s “perfect mental lens.” The heat of his exasperation is felt (“And Couch and Smith!”) but Lincoln’s analysis of Meade’s errors is undistorted by that heat, delivered in concise, flourish-free prose that’s all the more blistering for what’s implicit in its restraint. There were no words to elaborate upon “the magnitude of the misfortune.” It was so overwhelming as to be unsayable. Reverend Henry Fowler wrote that Lincoln’s style was “oftentimes of Saxon force and classic purity.” The sentence “As it is, the war will go on indefinitely” has, in its compression, some of the same power as the devastating four words Lincoln spoke twenty months later, at his second inaugural: “And the war came.”

But the most remarkable line of the Meade letter, and in a sense its most Lincolnian feature, is the faint note written (by what to our eyes seems a hand other than Lincoln’s) on the last page. “President’s endorsement on the envelope: To Gen. Meade, never sent or signed.”

Though it was occasioned by Meade’s request to be relieved of command, this is neither an official admonishment nor an official refusal of the request (Lincoln is always cagey). Its incisiveness notwithstanding, the letter began as a personal communication from one anguished man to another. Emotional agony, sorrow, reluctance, “magnificent success” and “deep distress,” gratitude, affection, regret, and painful anger are arrayed in uncomfortable proximity, with no attempt by the writer to reconcile conflict.

The impulse to blame, as rare in Lincoln as self-pity, originates in memory, in the past. The past mattered to Lincoln; his contention that slavery and inequality were inimical to democracy and union was built on antecedence, on a study of legal and legislative history. But as his evolving ideas for reconstruction showed, judging people for what they’d done was far less meaningful to Lincoln than holding people to declarations of what they intended to do. The past had to be confronted for the purpose of being released from it, so that the future would become conceivable.

That the letter would never be sent is perhaps foreshadowed by Lincoln’s anticipation of further discussion with Meade at a time “when we shall both feel better.” What Lincoln began as correspondence on July 14 became contemplative, an introspective working through of rage and despair that results in an emancipation of empathy. Meade would never be officially reprimanded for Lee’s escape at Gettysburg, nor would he be exculpated by the president. It’s not clear that he should have been entirely forgiven, though Lincoln eventually doubted whether Meade, new to his command of the Army of the Potomac, could have asked more of his exhausted men after their epic struggle. There’s a short speech, delivered four months later at Gettysburg, that gives a fair account of what Lincoln came to believe was accomplished there.

In 1861, Secretary of State William Seward observed to his wife, Frances, that Lincoln’s “confidence and sympathy increase almost every day.” Since a prevalent assumption of the politics of our own time has been that confidence and sympathy are antagonistic qualities, that compassion weakens authority and strength is a betrayal of kindness, it’s worth considering the combination of attributes Seward discerned in his beleaguered president.

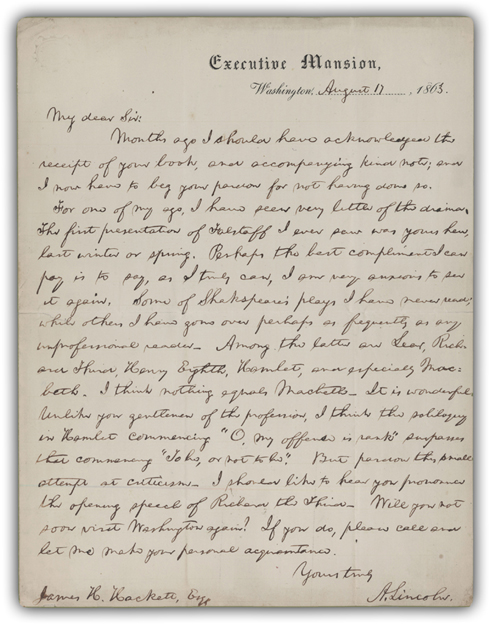

LETTERS TO JAMES HACKETT, AUGUST 17, 1863 AND NOVEMBER 2, 1863

Lincoln’s audacious but heartfelt comments on Shakespeare were leaked to the press by their recipient, actor James Hackett, and much mocked.

Click here to see images of the full letter.

Washington, August 17, 1863.

My dear Sir:

Months ago I should have acknowledged the receipt of your book, and accompanying kind note; and I now have to beg your pardon for not having done so. For one of my age, I have seen very little of the drama. The first presentation of Falstaff I ever saw was yours here, last winter or spring. Perhaps the best compliment I can pay is to say, as I truly can, I am very anxious to see it again. Some of Shakspeare’s plays I have never read; while others I have gone over perhaps as frequently as any unprofessional reader. Among the latter are Lear, Richard Third, Henry Eighth, Hamlet, and especially Macbeth. I think nothing equals Macbeth. It is wonderful. Unlike you gentlemen of the profession, I think the soliloquy in Hamlet commencing “O, my offence is rank” surpasses that commencing “To be, or not to be.” But pardon this small attempt at criticism. I should like to hear you pronounce the opening speech of Richard the Third. Will you not soon visit Washington again? If you do, please call and let me make your personal acquaintance.

Yours truly

James H. Hackett, Esq. A. Lincoln.

Executive Mansion,

Washington, Nov. 2, 1863.

James H. Hackett

My dear Sir:

Yours of Oct. 22nd is received, as also was, in due course, that of Oct. 3rd I look forward with pleasure to the fulfillment of the promise made in the former.

Give yourself no uneasiness on the subject mentioned in that of the 22nd.

My note to you I certainly did not expect to see in print; yet I have not been much shocked by the newspaper comments upon it. Those comments constitute a fair specimen of what has occurred to me through life. I have endured a great deal of ridicule without much malice; and have received a great deal of kindness, not quite free from ridicule. I am used to it.

Yours truly,

A. Lincoln

A period theatrical poster showing actor James Hackett in his signature role. Lincoln once termed the rebellion “these days of villainy,” pointing out: “it is old ‘Jack Falstaff’ who talks about ‘villainy,’ though of course Shakespeare is responsible.”

Many thoughts struck me as I read Lincoln’s letters to actor James Hackett, not least that he was feeling relaxed enough to answer nonurgent mail! The decisive Gettysburg victory, followed by the surrender of Vicksburg the following day on the Fourth of July (which General Lee later admitted was the decisive event of the war), must have, finally, warmed the heart of the president and made him feel that victory was, perhaps, within sight—that this “great trouble” might soon be over.

Lincoln fell in love with the works of Shakespeare as a young man and that love became stronger during his years in office, as Shakespeare’s insights into the human condition and the substance of his plays gave solace to Lincoln’s deepening sense of tragedy as the Civil War progressed.

Watching Hackett’s performance of Falstaff in Henry IV (to which the first letter refers), the president was seen to be sad but very focused on what was being said onstage, as if to ascertain the correctness of his own conception as compared with that of the professional artist.

I find it interesting that Lincoln says, “I think nothing equals Macbeth.” Here is a play about power, politics, jealousy, treason, and planning war campaigns, all of which he is dealing with as president—while, like Macbeth, married to a woman who is as ambitious as he is and gradually growing more paranoid. Perhaps Lincoln felt he too had blood on his hands from the continuing carnage.

Then he picks Claudius’s soliloquy from Hamlet, act three, scene three, as a particular favorite. This is a character asking himself if he can ever be forgiven for his heinous crime. (He killed his brother, Hamlet’s father.) And though he prays, his prayers have no value (“my words fly up, my thoughts remain below”). One can only imagine the long, lonely days and nights where Lincoln must have confronted his id, analyzed the nature of the war and its consequences and, indeed, tried to offer up prayers for, perhaps, forgiveness and blessed release.

I do agree with the great Walt Whitman, who, in comparing President Lincoln to Shakespeare, said: “What Shakespeare did in poetic expression, Abraham Lincoln essentially did in his personal and official life.” The sixteenth president of the United States was a pretty good poet as well and, boy, could he write a letter! No wonder Hackett had it printed and distributed to all his “friends”!

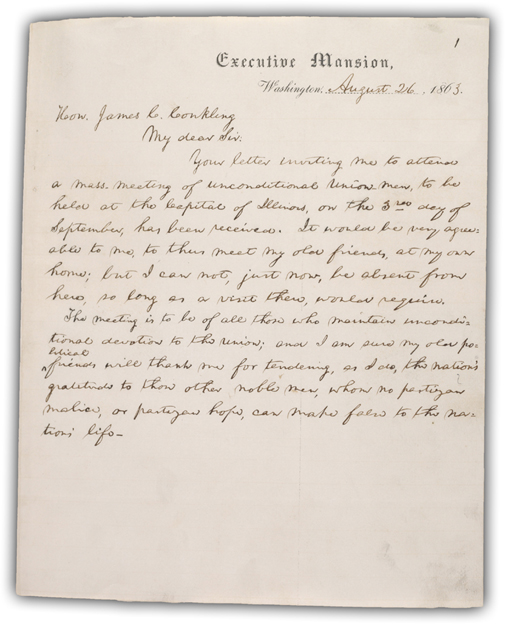

THE PUBLIC LETTER TO JAMES C. CONKLING, AUGUST 26, 1863

An invitation to a pro-Union rally inspired this extraordinary defense of emancipation and black enlistment. Lincoln wrote the letter as an oration to be read aloud by a surrogate, whom he instructed to speak “very slowly”— the way Lincoln himself delivered speeches.

Click here to see images of the full letter.

Washington, August 26, 1863.

Hon. James C. Conkling

My dear Sir:

Your letter inviting me to attend a mass-meeting of unconditional Union-men, to be held at the Capital of Illinois, on the 3rd day of September, has been received. It would be very agreeable to me, to thus meet my old friends, at my own home; but I can not, just now, be absent from here, so long as a visit there, would require.

The meeting is to be of all those who maintain unconditional devotion to the union; and I am sure my old ^ political friends will thank me for tendering, as I do, the nation’s gratitude to those other noble men, whom no partizan malice, or partizan hope, can make false to the nation’s life.

While some Northerners doubted—and many Southerners feared—the Union plan to arm its newly recruited African-American troops, this Harper’s Weekly cover illustration, published in March 1863, made the case that the new troops would make fine soldiers. Such images served to reassure nervous whites.

There are those who are dissatisfied with me. To such I would say: You desire peace; and you blame me that we do not have it. But how can we attain it? There are but three conceivable ways. First, to suppress the rebellion by force of arms. This I am trying to do. Are you for it? If you are, so far we are agreed. If you are not for it, a second way is to give up the Union. I am against this. Are you for it? If you are, you should say so plainly. If you are not for force, nor yet for dissolution, there only remains some immaginable compromise. I do not believe any compromise, embracing the maintainance of the union, is now possible. All I learn leads to a directly opposite belief. The strength of the rebellion, is it’s military — it’s army. That army dominates all the country, and all the people, within it’s range. Any offer of terms made by any man or men within that range, in opposition to that army, is simply nothing for the present; because such man or men, have no power whatever to enforce their side of a compromise, if one were made with them. To illustrate. Suppose refugees from the South, and peace men of the North, get together in convention, and frame and proclaim a compromise embracing a restoration of the Union, in what way can that compromise be used to keep Lee’s army out of Pennsylvania? Meade’s army can keep Lees army out of Pennsylvania; and, I think, can ultimately drive it out of existence. But no paper compromise to which the controllers of Lee’s army are not agreed, can at all affect that army. In an effort at such compromise we should waste time, which the enemy would improve to our disadvantage; and that would be all. A compromise, to be effective, must be made, either with those who control the rebel army, or with the people first liberated from the domination of that army, by the successes of our own army. Now allow me to assure you, that no word or intimation, from the rebel army, or from any of the men controlling it, in relation to any peace compromise, has ever come to my knowledge, information or belief. All charges and insinuations to the contrary, are utter humbuggery and falsehood deceptive, and groundless.

And I promise you that if any such proposition shall hereafter come, it shall not be rejected, and kept a secret from you. I freely acknowledge myself the servant of the people, according to the bond of service — the United States constitution; and that, as such, I am responsible to them.

Lincoln entrusted James C. Conkling, his longtime intimate from Springfield, to deliver a crucial public letter. It helped that Lincoln considered Conkling “one of the best public readers.”

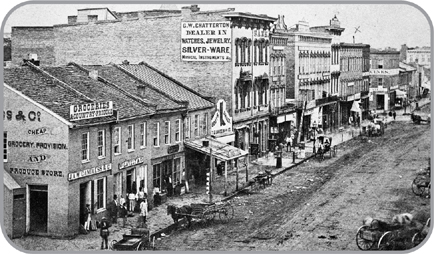

A row of modern buildings rises over the public square in Lincoln’s once-sleepy Springfield hometown—now a thriving city—where his Conkling “letter” was delivered in 1863.

But, to be plain, you are dissatisfied with me about the negro. Quite likely there is a difference of opinion between you and myself upon that subject. I certainly wish that all men could be free, while I suppose you do not. Yet I have neither adopted

Washington 186.

nor proposed any measure, which is not consistent with even your view, provided you are for the Union. I suggested compensated emancipation; to which you replied you wished not to be taxed to buy negroes. But I had not asked you to be taxed to buy negroes, except in such way, as to save you from greater taxation to save the Union exclusively by other means.

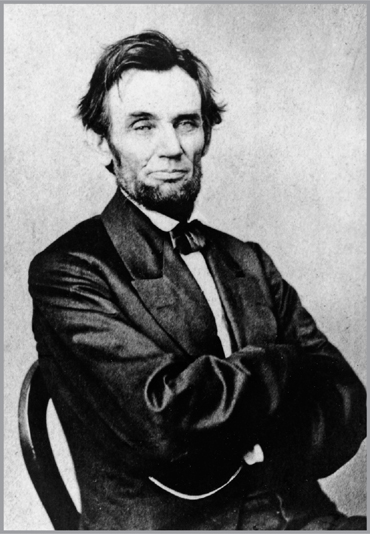

Looking exhausted but defiant, Lincoln poses for Treasury Department photographer Lewis E. Walker in Washington in 1863.

You dislike the emancipation proclamation; and, perhaps, would have it retracted. You say it is unconstitutional. I think differently. I think the constitution invests it’s commander-in-chief, with the law of war in time of war. The most that can be said, if so much, is that slaves are property. Is there — has there ever been — any question that by the law of war, property, both of enemies and friends, may be taken when needed? And is it not needed whenever taking it, helps us, or hurts the enemy? Armies, the world over, destroy enemie’s property when they can not use it; and even destroy their own to keep it from the enemy. Civilized beligerents do all in their power to help themselves, or hurt the enemy, except a few things regarded as barbarous or cruel. Among the exceptions are the massacres of vanquished foes, and non-combattants, male and female.

But the proclamation, as law, either is valid, or is not valid. If it is not valid, it needs no retraction. If it is valid, it can not be retracted, any more than you can bring the dead ^ can be brought to life. Some of you profess to think it’s retraction would operate favorably for the Union. Why better after the retraction, than before the issue? There was more than a year and a half of trial to suppress the rebellion before the proclamation issued, the last one hundred days of which passed under an explicit notice that it was coming, unless averted by those in revolt, returning to their allegiance. The war has certainly progressed as favorably for us, since it’s the issue of the proclamation as before.

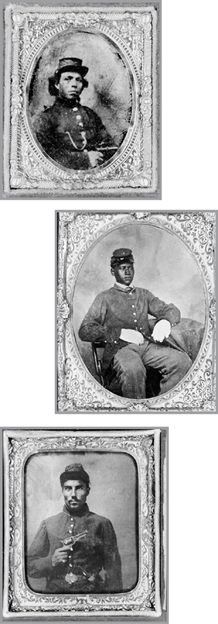

Freshly uniformed African-American soldiers pose for tintype photographs intended for loved ones at home. “The Star Spangled Banner is now the harbinger of Liberty,” Frederick Douglass accurately predicted after Lincoln issued his preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, “and the millions in bondage, inured to hardships, accustomed to toil, ready to suffer, ready to fight, to dare and to die, will rally under that banner wherever they see it gloriously unfolded to the breeze.” By war’s end, some 200,000 black men had served in the Union Army and Navy, fighting in 449 battles and suffering casualties 35 percent greater than white troops.

You say you will not fight to free negroes. Some of them seem willing to fight for you; but, no matter. Fight you, then, exclusively to save the Union. I issued the proclamation on purpose to aid you in saving the Union. Whenever you shall have conquered all resistence to the Union, if I shall urge you to continue fighting, it will be an apt time ^ then for you to declare you will not fight to free negroes.

I thought that that in your struggle for the Union, to whatever extent the negroes should cease helping the enemy, to that extent it weakened the enemy in his resistence to you. Do you think differently? I thought that whatever negroes can be got to do as soldiers leaves just so much less for white soldiers to do, in saving the Union. Does it appear otherwise to you? But negroes, like other people, act upon motives. Why should they do any thing for us, if we will do nothing for them? If they stake their lives for us, they must be prompted by the strongest motive — even the promise of freedom. And the promise being made, must be kept.

All but illustrating Lincoln’s blunt reminder that “some of them seem willing to fight for you”—meaning so-called “colored troops”—Kurz & Allison’s famous chromo shows black soldiers from the legendary 54th Massachusetts, led by white Colonel Robert Gould Shaw, meeting a heroic death at Fort Wagner in 1863.

The signs look better. The Father of Waters again goes unvexed to the sea. Thanks to the great North-West for it. Nor yet wholly to them. Three hundred miles up, they met New-England, Empire, Key-Stone, and the Jerseys ^ Jersey, hewing their way right and left. The Sunny South too, in more colors than one, also lent a hand. On the spot their part of the history was jotted down in black and white. The job was a great national one; and let none be banned who bore an honorable part in it. And while those who have cleared the great river may well be proud, even that is not all. Nothing It is hard to say that anything has been more bravely, and well done, than at Antietam, Murfreesboro, Gettysburg, and on many fields of lesser note. Nor must Uncle Sam’s Web-feet be forgotten. At all the watery margins they have been present. Not only on the deep sea, the broad bay, and the rapid river; but also up the narrow muddy bayou, and wherever the ground was a little damp, they have been, and made their tracks. Thanks to all. For the great republic — for the principle it lives by, and keeps alive — for man’s vast future — thanks to all.

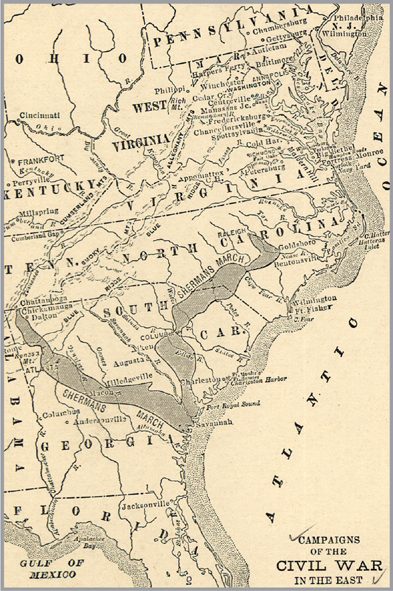

A map published around the time of the Lincoln centennial pinpoints the military campaigns of the Civil War. Lincoln, who loved maps and kept several in his White House office, visited few of the Southern states shown here, but believed passionately that the federal union was indivisible. “As to any dread of my having ‘a purpose to enslave or exterminate the whites of the South,’ ” Lincoln wrote, “I can scarcely believe that such dread exists. It is absurd.”

Peace does not appear so distant as it did. I hope it will come soon, and come to stay; and so come as to be worth the keeping in all future time. It will then have been proved that, among free men, there can be no successful appeal from the ballot to the bullet; and that they who take such appeal are sure to lose their case, and pay the cost. And then, there will be some black men who can remember that, with silent tongue, and clenched teeth, and steady ^ eye, and well borne poised bayonet, they have helped mankind on to this great consummation; while ^ I fear, there will be some white ones, unable to forget that, with malignant hearts, and deceitful speech, they have strove to hinder it.

Still, let us not be over-sanguine of a speedy final triumph. Let us be quite sober. Let us diligently apply the means, never doubting that a just God, in his own good time, will give us the rightful result.

Yours very truly

A Lincoln

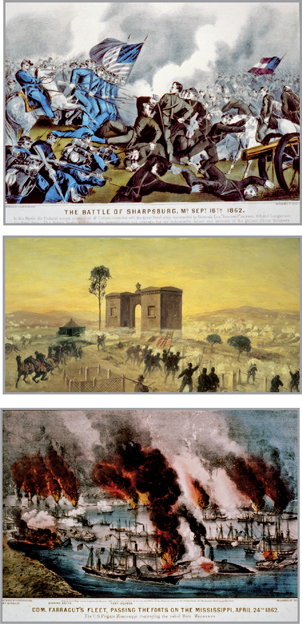

“The signs look better,” Lincoln declared in his Springfield message, pointing to Union victories celebrated in period graphics: The Battle of Antietam (or Sharpsburg; a print by Currier & Ives), the Battle of Gettysburg (a sketch by Edwin Forbes), and the capture of the “father of waters,” the Mississippi River, as vivified in this Currier & Ives print of Farragut’s fleet breaking past Forts Jackson and St. Philip en route to New Orleans.

In the midst of the Civil War, President Lincoln was invited to a meeting in his hometown of Springfield, Illinois, to address Union supporters, including some who were opposed to the Emancipation Proclamation, which they believed made it more difficult to negotiate an end to the war.

Lincoln couldn’t attend the meeting, but sent this remarkable letter to be read in his absence. After thanking those in attendance for supporting the Union, Lincoln takes on his critics in trademark fashion, stating their arguments, then demolishing them. He defends his authority to emancipate the slaves and denies the possibility of any acceptable negotiated end to the war. He entreats them to embrace victory as the only practical alternative, even if they reject the moral ground on which he stands. “You say you will not fight to free negroes. Some of them seem willing to fight for you; but, no matter. Fight you, then, exclusively to save the Union.”

Just as they did in 1863, Lincoln’s words ring strong and true today, another time of complex challenges and elusive solutions. We can learn a lot from Lincoln’s constant search for the right mix of persuasion and power, mind and heart, to preserve and perfect our Union.

LETTER TO CPT. JAMES M. CUTTS, JR., OCTOBER 26, 1863

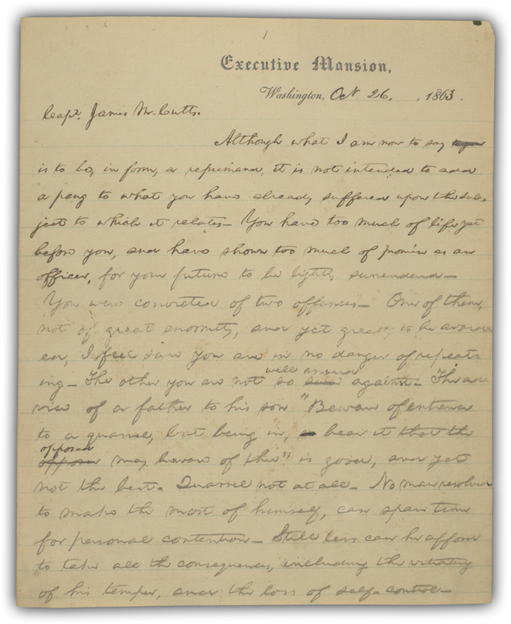

Ever loyal, and characteristically forgiving, the president clearly labored over this rarely cited gem of literature: advice to the brother-in-law of his late, longtime political enemy, Stephen A. Douglas, as the young man faced disheartening military discipline.

Click here to see images of the full letter.

Washington, Oct 26, 1863.

Capt. James M. Cutts.

Although what I am now to say to you is to be, in form, a reprimand, it is not intended to add a pang to what you have already suffered upon the subject to which it relates. You have too much of life yet before you, and have shown too much of promise as an officer, for your future to be lightly surrendered. You were convicted of two offences. One of them, not of great enormity, and yet greatly to be avoided, I feel sure you are in no danger of repeating. The other you are not so sure well armed against. The advice of a father to his son “Beware of entrance to a quarrel, but being in, so bear it that the opposer opposed may beware of thee” is good, and yet not the best. Quarrel not at all. No man resolved to make the most of himself, can spare time for personal contention. Still less can he afford to take all the consequences, including the vitiating of his temper, and the loss of self-control.

Yield larger things to which you can show no more than equal right; and yield lesser ones, though clearly your own. Better give your path to a dog, than be bitten by him in contesting for the right. Even killing the dog would not cure the bite.

In the mood indicated deal henceforth with your fellow man, and especially with your brother officers; and even the unpleasant events you are passing from will not have been profitless to you.

Though Cutts—a white man—went virtually unpunished for his offenses as a Peeping Tom, black soldiers convicted of sexual offenses against white women were dealt with harshly, as this horrifying execution scene attests. It was likely taken, and circulated, to discourage other potential offenders.

The young army officer to whom Lincoln addressed this gentle note had been court-martialed for “conduct unbecoming an officer and a gentleman,” and sentenced to dismissal from the service. Taking into account the “previous good character” of Captain Cutts, Lincoln had reduced the sentence to a reprimand. The first charge against Cutts—that he had been found peeping through a blind at a lady undressing in a neighboring room—Lincoln considered “not of great enormity.” Indeed, he later jokingly suggested that Cutts “should be elevated to the peerage for it with the title of Count Peeper.” The second charge—that his intemperate words in addressing a superior officer had almost led to a duel—was more serious, demanding the reprimand.

Yet, in the very first sentence, Lincoln reveals what may have been the most important of his emotional strengths—his unusual empathy, his gift of putting himself in the place of others, for he tells Cutts that the reprimand “is not intended to add a pang to what you have already suffered,” but instead is to be seen as the advice of a wise father to a son: “No man resolved to make the most of himself,” Lincoln writes, “can spare time for personal contention.” The advice comes from the heart. All his life, Lincoln tried to avoid petty grievances. He refused to submit to jealousy or to brood over perceived slights.

“Better give your path to a dog, than be bitten by him contesting for the right. Even killing the dog would not cure the bite.” Here Lincoln’s literary and storytelling skills are on full display. With concrete, visual language, he forcefully and memorably illustrates his point.

Then, in closing, he affectionately suggests that if the young officer can learn from his painful experience, “the unpleasant events … will not have been profitless.” Cutts returned to the army, and served with great distinction.

GETTYSBURG ADDRESS, NOVEMBER 19, 1863

What Lincoln said at Gettysburg is fixed like stone in American memory. But Lincoln’s words were far from fixed. Even after he delivered the speech, he continued to revise it, showing close attention to rhythm and nuance. This, the so-called Hay Copy, is probably the second draft. Historians remain unsure about which copy Lincoln actually read from, but the many drafts make it clear the president did not write the speech in haste on the train, as legend stubbornly insists.

Click here to see images of the full letter.

Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth, upon this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation, so conceived, and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met here on a great battle-field of that war. We are met have come to dedicate a portion of it as the a final resting place of for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

A newly unearthed photograph shows a top-hatted man on horseback—likely Lincoln himself—nearing the speaker’s platform at Gettysburg on November 19, 1863.

But in a larger sense we can not dedicate — we can not consecrate — we can not hallow this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it far above our ^ poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember, what we say here, but can never forget what they did here. It is for us, the living, rather to be dedicated here to the unfinished ^ work which they have, thus far, so nobly carried on. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before ^ us — that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to the that cause for which they here gave gave the last full measure of devotion — that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain; that this nation shall have a new birth of freedom; and that this government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

Lincoln poses for photographer Alexander Gardner eleven days before delivering the Gettysburg Address.

Bareheaded, President Lincoln takes his place on the speaker’s platform at the new Gettysburg National Cemetery on November 19, 1863. Hours will pass—filled with hymns and orations—before he finally rises to deliver his two minutes of “appropriate remarks.”

When a president of the United States thought about the graveyard his country had become, and said, “The world will little note, nor long remember, what we say here, but can never forget what they did here,” his simple words were exhilarating in their life-sustaining properties because they refused to encapsulate the reality of 600,000 dead men in a cataclysmic race war.

Refusing to monumentalize, disdaining the “final word,” the precise “summing up,” acknowledging their “poor power to add or detract,” his words signal deference to the uncapturability of the life they mourn. It is the deference that moves here, that recognition that language can never live up to life once and for all. Nor should it. Language can never “pin down” slavery, genocide, war. Nor should it yearn for the arrogance to be able to do so. Its force, its felicity, is in its reach toward the ineffable.

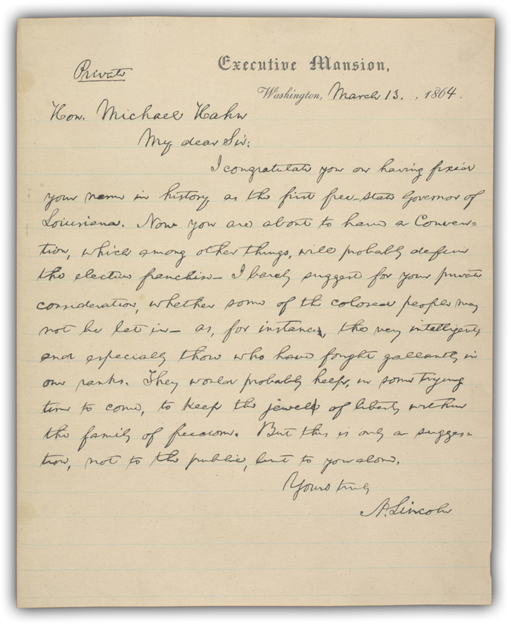

LETTER TO GOV. MICHAEL HAHN, MARCH 13, 1864

On March 4, 1864, Michael Hahn was elected governor of Louisiana, which became the first of the seceded states to organize a government committed to the Union. Eleven days later, Lincoln wrote Hahn to make known, gingerly, his instincts on black suffrage.

Private

Washington, March 13., 1864.

Hon. Michael Hahn

My dear Sir:

I congratulate you on having fixed your name in history as the first free-state Governor of Louisiana. Now you are about to have a Convention, which among other things, will probably define the elective franchise. I barely suggest for your private consideration, whether some of the colored people may not be let in — as, for instances, the very intelligent, and especially those who have fought gallantly in our ranks. They would probably help, in some trying time to come, to keep the jewell of liberty within the family of freedom. But this is only a suggestion, not to the public, but to you alone.

Yours truly

A. Lincoln

In 2001, at a conference on the Louisiana Native Guard, a Civil War regiment of black and colored men, I met Julie Hilla, an older white woman with short wavy hair, round librarian glasses, and merry eyes. I figured her for a genealogist or researcher. But when I told her that my great-great-grandfather had fought with the colored troops, she surprised me. “So you’re mixed too!” she exclaimed.

Julie, like me, had grown up unaware of her African ancestry. When we met, I had known about my dad’s Creole background for eleven years. Julie had only just found out, at seventy-eight. She had long known her grandfather was an early civil rights activist and was tickled to read, in a book on New Orleans history, how Arnold Bertonneau visited President Lincoln to petition for black suffrage. But when she saw her grandfather described as “a colored gentleman,” she told her husband that the author must be mistaken. She found out later that she’d long been deceived.

The day after meeting with Julie’s grandfather and his associate, Lincoln wrote this letter to Louisiana’s governor; the governor ignored his suggestion that “some of the colored people” be let into the franchise. When Lincoln repeated his desire for black suffrage in a speech marking the end of the war, John Wilkes Booth declared he’d kill him.

Back in Louisiana, following a short-lived Reconstruction, Bertonneau challenged the segregation of his children’s elementary school. After losing the suit, he left New Orleans for California, where Julie’s mother would be raised as white. But unlike many families who never look back after crossing the color line, the Bertonneaus kept alive the memory of their grandfather—and his brush with history.

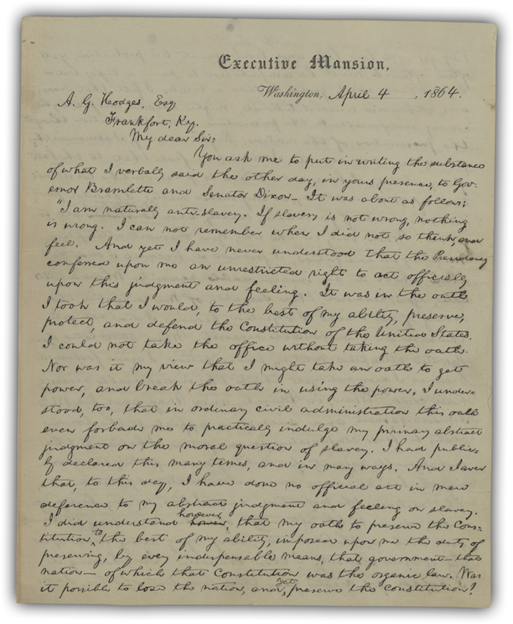

LETTER TO ALBERT HODGES, APRIL 4, 1864

In this careful letter, Lincoln narrated the history of his ideas and actions on American slavery. The letter combines a declaration of personal sentiments, a constitutional argument, and, in the end, a nervy theological claim.

Click here to see images of the full letter.

Washington, April 4, 1864.

A. G. Hodges, Esq

Frankfort, Ky.

My dear Sir:

You ask me to put in writing the substance of what I verbally said the other day, in yours presence, to Governor Bramlette and Senator Dixon. It was about as follows: “I am naturally anti-slavery. If slavery is not wrong, nothing is wrong. I can not remember when I did not so think, and feel. And yet I have never understood that the Presidency conferred upon me an unrestricted right to act officially upon this judgment and feeling. It was in the oath I took that I would, to the best of my ability, preserve, protect, and defend the Constitution of the United States. I could not take the office without taking the oath. Nor was it my view that I might take an oath to get power, and break the oath using the power. I understood, too, that in ordinary civil administration this oath even forbade me to practically indulge my primary abstract judgment on the moral question of slavery. I had publicly declared this many times, and in many ways. And I aver that, to this day, I have done no official act in mere deference to my abstract judgment and feeling on slavery. I did understand hower, however, that my oath to preserve the Constitution ^ to the best of my ability, imposed upon me the duty of preserving, by every indispensable means, that government — that nation — of which that Constitution was the organic law. Was it possible to lose the nation, and ^ yet preserve the Constitution? By general law life and limb must be protected; yet often a limb must be amputated to save a life; but a life is never wisely given to save a limb. I felt that measures, otherwise unconstitutional, might become lawful, by becoming indispensable to the preservation of the Constitution, through the preservation of the nation. Right or wrong, I assumed this ground, and now avow it. I could not feel that, to the best of my ability, I had even tried to preserve the Constitution, if, to save slavery, or any minor matter, I should permit the wreck of government, country, and Constution Constitution all together. When, early in the war, Gen. Fremont attempted military emancipation, I forbade it, because I did not then think it an indispensable necessity. When a little later, Gen. Cameron, then Secretary of War, suggested the arming of the blacks, I objected, because I did not yet think it an indispensable necessity. When, still later, Gen. Hunter attempted military emancipation, I again forbade it, because I did not yet think the indispensable necessity had come. When, in March, and May, and July 1862 I made earnest, and successive appeals to the border states to favor compensated emancipation, I believed the indispensable necessity for military emancipation, and arming the blacks would come, unless averted by that measure, They declined the proposition; and I was, in my best judgment, driven to the alternative of either surrendering the Union, and with it, the Constitution, or of laying strong hand upon the colored element. I chose the latter. In choosing it, I hoped for greater gain than loss; but of this, I was not entirely confident. More than a year of trial now shows no loss by it in our foreign relations, none in our home popular sentiment, none in our white military force, — no loss by it any how, or ^ any where. On the contrary, it shows a gain of quite a hundred and thirty thousand soldiers, seamen, and laborers. There are palpable facts, about which, as facts, there can be no cavilling. We have the men; and we could not have had them without the measure.

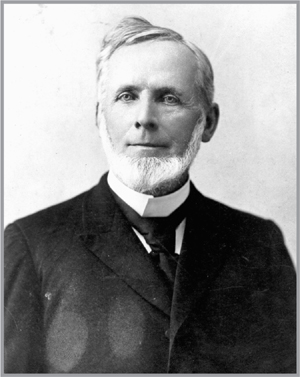

Rev. Phineas Densmore Gurley held the pulpit at Washington’s New York Avenue Presbyterian Church, where Lincoln often worshipped. “I like Gurley,” the president explained. “He don’t preach politics. I get enough of that through the week, and when I go to church, I like to hear the gospel.”

And now let any Union man who complains of the measure, test himself by writing down in one line that he is for subduing the rebellion by force of arms; and in the next, that he is for taking these hundred and thirty thousand men from the Union side, and placing them where they would be but for the measures he condemns. If he can not face his case so stated, it is only because he can not face the truth.

I add a word which was not in the verbal conversation. In telling ^ this tale I attempt no compliment to my own sagacity. I claim not to have controlled events, but confess plainly that events have controlled me. Now, at the end of three years struggle the nation’s condition is not what either party, or any man devised, or expected. God alone can claim it. Whither it is tending seems plain. If God now wills the removal of a great wrong, and wills also that we of the North as well as you of the South, shall pay fairly for our complicity in that wrong, impartial history will find therein no new cause to question applaud attest and revere the justice or and goodness of God.

Yours truly

A. Lincoln

Long an outspoken critic, Frederick Douglass visited Lincoln in the White House to demand that black enlistees receive equal pay. “I assure you, Mr. Douglass,” Lincoln replied, “that in the end they shall have the same pay as white soldiers.…” The abolitionist later admitted that, compared to his racist fellow countrymen, Lincoln was “swift, zealous, radical, and determined.”

Lincoln magnifies as he comes down the ages. The momentum of his collected words reminds us of those better angels he tried to summon, the difference between his actual achievements and those we too generously and posthumously bestow on him, our own collective wish for ourselves. But Lincoln is first and foremost a wholly political animal, tacking furiously this way and that to find those elusive gusts that would propel him (and us) forward. Nowhere is this more evident than in his famous letter to Albert Hodges, written in early April of 1864. In retrospect we impose on Mr. Lincoln the simplistic virtues of a Hollywood hero, a crusading “Mr. Smith” who goes to Washington to free the slaves and reset America’s course, and not the shrewd western politician he actually was. But as this slippery letter to a border-state newspaperman shows, Lincoln was nearly always willing to continue his abstraction of slavery (an abstraction that so disappointed Frederick Douglass and others) to mollify his border-state allies and keep himself firmly within his political mentor Henry Clay’s anachronistic worldview.

The famous phrase from this letter “… yet often a limb must be amputated to save a life; but a life is never wisely given to save a limb …” is often cited as expressing the excruciating calculus that placed the survival of the Union, and not the immediate emancipation of the slaves, as paramount in Lincoln’s efforts. But what that phrase, and indeed the whole letter, more accurately reflects, is the tension in Lincoln’s own view of the law. (That tension informs nearly all of his tortured debates about slavery from the beginning of his career.) Lincoln, once again, carefully parses the difference between “natural” law, and the total and unequivocal repudiation of slavery that natural law suggests, and the man-made or “positive” laws he believes the Constitution requires him to obey above all else. Stubbornly embedded among those “positive” laws are of course the ones that have perpetuated the institution of slavery, an institution Lincoln continually claims to abhor. Despite having invoked the Declaration of Independence’s obvious appeal to natural laws in his celebrated address at Gettysburg the previous November, Lincoln here reverts to a more careful argument that will bedevil abolitionists, perhaps mollify those border-state sympathies requiring more gradual emancipation, and do nothing to quell the ardor of the separationists in rebellion. Lost in all the parsing, of course, are the four million Americans owned by other Americans, whose lives, once again, have been reduced to merely a legal interpretation, albeit a well-reasoned and well-intentioned one, by our Great Liberator.

The “grand White House reception” depicted in this oversize display print honored the newly promoted Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant in 1864. Even in the darkest days of the war, Lincoln and his wife (except for the time she secluded herself in mourning for her late son Willie) maintained a surprisingly vigorous social schedule of public levees, diplomatic receptions, dinners, outdoor concerts, and other events.

Lincoln’s quest for a second term inspired fewer prints than the first—but that was because by 1864 he was so well known. This Currier & Ives banner suggested through its symbolic design that a Lincoln victory would usher in an era of economic prosperity.

TELEGRAMS TO GEN. ULYSSES S. GRANT, AUGUST 17, 1864 AND APRIL 7, 1865

In Ulysses S. Grant, Lincoln finally found a general as tenacious as he, and together they enacted a ruthless strategy to destroy the Confederate armies and collapse Southern morale. These brief dispatches show Lincoln in sync with his general—though not without humor.

“Cypher”

Washington, August 17., 1864.

Lieut. Gen. Grant

City Point, Va.

I have seen your despatch expressing your unwillingness to break your hold where you are. Neither am I willing. Hold on with a bull-dog gripe, and chew & choke, as much as possible.

A. Lincoln

Head Quarters Armies of the United States,

City-Point, April 7, 11. Am. 1865

Lieut Gen. Grant.

Gen. Sheridan says “If the thing is pressed I think that Lee will surrender.” Let the thing be pressed.

A. Lincoln

The original dispatch sent by Mr. Lincoln to me Apl 7th 1865,

U. S. Grant

Lincoln was a great hero, obviously, for myriad reasons—he was a political genius and forward-thinking philosopher. But you could also make a case that he was up there with Twain as a great comic writer of his time.

The second of these two telegrams to Grant is one of my favorite examples. At the end of the Civil War, when Lee was being routed, Sheridan sent a telegram to Lincoln that said, “If the thing is pressed” —meaning, if Grant pursues him—“I think that Lee will surrender.” Lincoln replied with a telegram that said, “Let the thing be pressed.”

It’s so simple. It’s brilliant. It’s like a Seinfeld bit. I can almost hear George Costanza say, “Actually, we could actually get a million dollars if the thing was pressed.” And Jerry saying, “Uh, let the thing be pressed.” Lincoln had the key qualities of a comedian—his language was tight and surprising. And he was doing this in the 1860s, at a time when people tended to take forever to get to the point and took themselves very seriously. Not only that, but he wrote his own material. Who does that anymore? Whenever you hear a president say something funny, a day later they’re always interviewing the guy who actually wrote it.

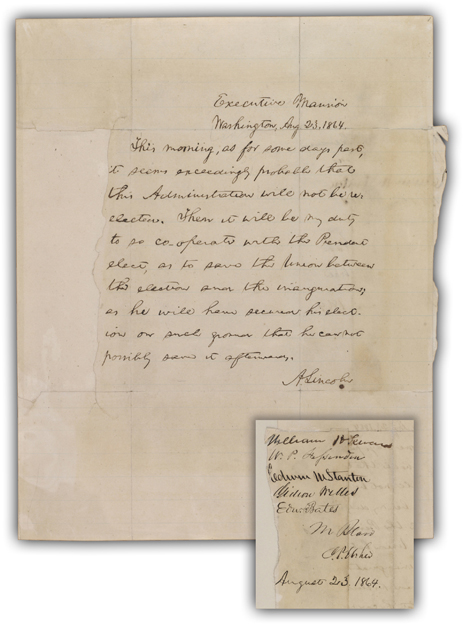

“BLIND MEMORANDUM,” AUGUST 23, 1864

On August 22, one of Lincoln’s closest advisors told him he would lose reelection in November, in part because of a public perception that he could end the war were it not for his abolitionism. On August 23, Lincoln asked members of his cabinet to sign this declaration— but he folded the paper so that they couldn’t read it.

Washington, Aug 23, 1864.

This morning, as for some days past, it seems exceedingly probable that this Administration will not be re-elected. Then it will be my duty to so co-operate with the President elect, as to save the Union between the election and the inauguration; as he will have secured his election on such ground that he can not possibly save it afterwards.

A. Lincoln

[ Endorsed on Reverse:]

William H Seward

W. P. Fessenden

Edwin M Stanton

Gideon Welles

Edwd. Bates

M Blair

J. P. Usher

August 23 1864.

Most of the civil wars that tear at our world today are, above all, wars of succession. What is at issue is the transfer of power from one leader and his followers to the next party. The ones with power won’t let go, and the ones without won’t give up. So they fight, and the country that both sides claim to rule is destroyed in the clash. The evocation of “military necessity” becomes the justification for the leader of each side to hold on to power more relentlessly than ever.

How extraordinary, then, to imagine President Lincoln in the desolate summer of 1864, as he fought a civil war and a reelection campaign simultaneously. By August of that year, every indication—military and political—was that Lincoln would lose on both fronts. The temptation to suspend elections must have been powerful. But the electoral process and the Union were inseparable, and Lincoln recognized that to win his fight to preserve the Union he might have to lose his office. That is the drama behind the “Blind Memo.” The destiny of the Union was greater than the president’s personal destiny, and no political passion could be allowed to interfere if the will of the people turned against him.

Lincoln saw what was at stake, but he was not sure that his cabinet members could stand to see it, which is why he folded the memo up and made them sign it without knowing what it said. That is what it means to lead, and what it means to serve. The crease marks—like those that carved ever more deeply into Lincoln’s face with each year of his presidency—tell the story.

LETTER TO ELIZA P. GURNEY, SEPTEMBER 4, 1864

On September 4, Lincoln anticipated the mood and the theme of his Second Inaugural Address in a letter to the distinguished Quaker Eliza P. Gurney. The two had visited together and shared prayers “for wisdom on high” in 1862. Lincoln confided that day that he believed America was going through what he called “a fiery trial” willed by God.

Click here to see images of the full letter.

Washington, September 4, 1864.

Eliza P. Gurney

My dear esteemed friend.

I have not forgotten — probably never shall forget — the very impressive occasion of the visit of when yourself and friends ^ visited to me on a Sabbath forenoon two years ago. Nor has your kind letter, written nearly a year later, ever been forgotten. In all, it has been your purpose to strengthen my reliance on God. I am much indebted to the good christian people of the country for their constant prayers and consolations; and to no one of them more than to-yourself. The purposes of God the Almighty are perfect, and must prevail, though we erring mortals may fail to accurately perceive them in advance. We hoped for a happy termination of this terrible war ere long before this; but God knows best, and has ruled otherwise. We shall yet perceive his acknowledge His wisdom, and our own error therein. Meanwhile we must work earnestly by in the best lights He gives, ^ us, trusting ^ that so working still conduces to the great ends He ordains. Surely He intends some great good to follow this mighty convulsion, which no mortal could make, and no mortal could hinder stay.

Quaker leader

Eliza P. Gurney praised Lincoln for his Emancipation Proclamation, quoting scripture to declare that it “burst the bands of wickedness, and let the oppressed go free.”

Your people — the Friends — have had, and are having, a very great trial. On principle, and faith opposed to both war and oppression, they can only ^ practically oppose oppression by war. In this hard dilema some have chosen one horn and some the other. For those appealing to me on conscientious grounds, I have done, and shall do,

the best I ^ could and can, in my own conscience, under my oath to the law. That you know believe this I doubt not; and knowing believing it, I shall still receive, for our country and myself, your earnest prayers to our common Father in Heaven,

Your sincere friend,

A. Lincoln

Burying the dead, Fredericksburg, Virginia, May 1864.

The handwriting is unmannered and clear—free, down to its signature, of ostentatious flourishes and signs of the haste for which the president of a nation at war with itself might have been forgiven. Though his penmanship picks up speed on the second page, and a few words, such as “some have chosen one horn and some the other” require a moment’s deciphering (right after the missive’s one misspelling, “dilema”), the overall impression is one of patience and delicacy, as the writer adjusts his personal tact and warmth to the grave considerations involved in addressing a pious Quaker lady. He stiffens the rote intimacy of “dear” to a more politicized “esteemed”; he distances “God” into “the Almighty”; and, as the commander in chief of cruelly bloodied armies, he reminds Mrs. Gurney that oppression (and no sect was more abolitionist than the pacifist Quakers) can only be “practically” opposed by war.

He trusts her to “believe,” since she cannot “know,” that his own conscience is engaged, under his oath to the law, with the immense question, later posed in his second inaugural address, of God’s purposes in “this terrible war.” To know that a war is terrible and yet steadfastly to prosecute it is a leader’s burden. He accepts her Christian prayers yet holds to his course in “this mighty convulsion, which no mortal could make, and no mortal could stay”—the monosyllabic verb more biblically stark than “hinder” and reverberent with the tragic sense that breathes through Lincoln’s wartime correspondence.

SECOND INAUGURAL ADDRESS, MARCH 4, 1865

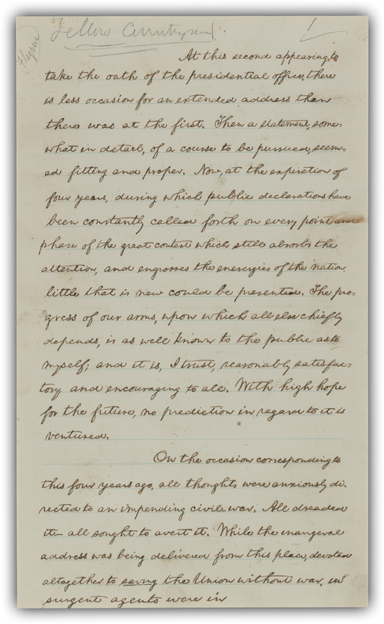

“I expect it to wear,” Lincoln wrote of his Second Inaugural, “as well as—perhaps better than—any thing I have produced.” Recognizing that many would object to its invocation of divine retribution to explain the sufferings produced by the war, he shrugged: “It is a truth which I thought needed to be told.”

Click here to see images of the full letter.

At this second appearing to take the oath of the presidential office, there is less occasion for an extended address than there was at the first. Then a statement, somewhat in detail, of a course to be pursued, seemed fitting and proper. Now, at the expiration of four years, during which public declarations have been constantly called forth on every point and phase of the great contest which still absorbs the attention, and engrosses the enerergies of the nation, little that is new could be presented. The progress of our arms, upon which all else chiefly depends, is as well known to the public as to myself; and it is, I trust, reasonably satisfactory and encouraging to all. With high hope for the future, no prediction in regard to it is ventured.

On the occasion corresponding to this four years ago, all thoughts were anxiously directed to an impending civil war. All dreaded it — all sought to avert it. While the inaugeral address was being delivered from this place, devoted altogether to saving the Union without war, in surgent agents were in the city seeking to destroy it without war — seeking to dissole the Union, and divide effects, by negotiation. Both parties deprecated war; but one of them would make war rather than let the nation survive; and the other would accept war rather than let it perish. And the war came.

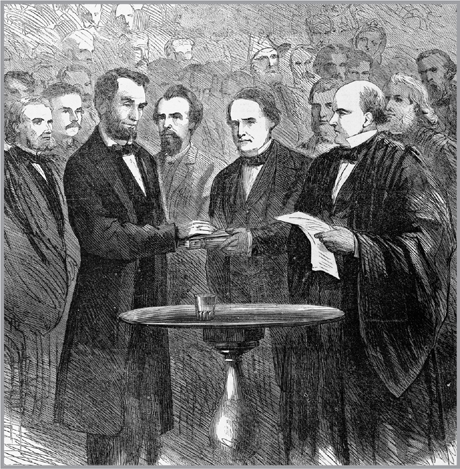

Following his inaugural address, newly confirmed Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase—only recently drummed out of the cabinet after plotting unsuccessfully to deny Lincoln renomination, then named to the bench anyway—administers the oath of office. The scene was sketched by an artist for Harper’s Weekly.

Waiting his turn to speak at his inaugural, Abraham Lincoln sits on the South Portico of the U.S. Capitol on March 4, 1865. This and the photograph below were taken on the scene by Alexander Gardner.

As the sun bursts forth from cloudy skies—making “my heart jump,” the president admitted—Lincoln, towering above a little white lectern, reads one of his greatest speeches to a huge throng assembled on the plaza below.

One eighth of the whole population were colored slaves, not distributed generally over the Union, but localized in the Southern ^ part half of it. These slaves constituted a peculiar and powerful interest. All knew that this interest was, somehow, the cause of the war. To strengthen, perpetuate, and extend this interest was the object for which the insurgents would rend the Union, even by war; while the government claimed no right to do more than to restrict the territorial enlargement of it. Neither party expected for the war, the magnitude, or the duration, which it has already attained. Neither anticipated that the cause of the conflict might cease with, or even before, the conflict itself should cease. Each looked for an easier triumph, and a result less fundamental and astounding. Both read the same Bible, and pray to the same God; and each invokes His aid against the other. It may seem strange that any men should dare to ask a just God’s assistance in wringing their bread from the sweat of other men’s faces; but let us judge not that we be not judged. The prayers of both could not be answered; that of neither has been answered fully. The Almighty has His own purposes. “Woe unto the world because of offences! for it must needs be that offences come; but woe to that man by whom the offence cometh!” If we shall suppose that American Slavery is one of those offences which, in the providence of God, must needs come, but which, having continued through His appointed time, He now wills to remove, and that He gives to both North and South, this terrible war, as the woe due to those by whom the offence came, shall we discern therein any departure from those divine attributes which the believers in a Living God always ascribe to Him? Fondly do we hope — fervently do we pray — that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away. Yet, if God wills that it continue, until all the wealth piled by the bond-man’s two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop ^ of blood drawn with the lash, shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said “the judgments of the Lord, are true and righteous altogether”

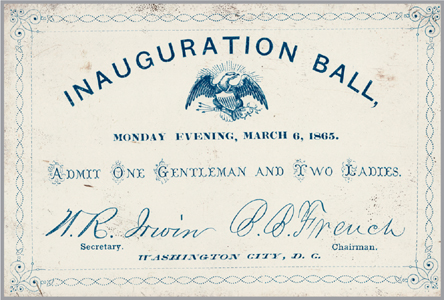

The 1865 inaugural ball was staged at the newly built Patent Office on F Street—now the National Portrait Gallery.

The inaugural ball menu—notwithstanding four years of war and deprivation—was typically sumptuous.

With malice toward none; with charity for all; with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation’s wounds; to care for him who shall ^ have borne the battle, and for his widow, and his orphan — to do all which may achieve and cherish a just, and a lasting peace, among ourselves, and with the world. all nations.

On March 4, 1865, Lincoln delivered what for Frederick Douglass, and many other African Americans, was his most resonant speech, a speech more about them and for them than any of Lincoln’s other speeches or writings, even the Emancipation Proclamation: 703 words, as historian Ted Widmer has pointed out, 505 of which were of one syllable, in just twenty-five sentences. It lasted all of six minutes. But in three distinct sections of his third paragraph, Lincoln pronounced, more powerfully than he ever had, the freedom of the Negro as the inextricable cause of the war that would soon grind to an end—a war that had left 623,000 Americans dead.

It is safe to say that never before in the history of the American presidency has the political economy of suffering, the rhetoric of a white eye for a black eye, been applied to the condition of the black enslaved. No wonder the reporter of The Times of London was struck by the call-and-response of Lincoln’s black audience, the shouts and murmurs of “bless the Lord” and similar phrases still familiar in the black church, which must have reached a crescendo as he hit his stride in that remarkable third paragraph.

Frederick Douglass later would note “a leaden stillness” about the white half of the crowd. For black folks in attendance that day, Abraham Lincoln had come home, and blacks had every reason to believe that, at long last, they had found a permanent home in America as freedmen at last. On that day, within that third paragraph, Lincoln became the President of black men and women, far more so than he had even through the Emancipation. No wonder Douglass, who had to fight his way past two racist guards to gain entrance to the White House immediately following the speech, told the president in response to his questioning: “Mr. Lincoln, that was a sacred effort.”

SECOND INAUGURAL ADDRESS, MARCH 4, 1865

Lincoln took this document, the product of typesetting and literal cutting and pasting, with him to the dais at the U.S. Capitol. Notice how Lincoln’s final emendation repeats the correction made on the handwritten manuscript.

With his young son Tad at his side, Lincoln visited the conquered Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia, on April 3, 1865—just twelve days before his death. The city’s black population greeted him with affection and reverence. Artist L. Hollis’s imagined sketch of the scene was engraved the following year by J. C. Buttre.

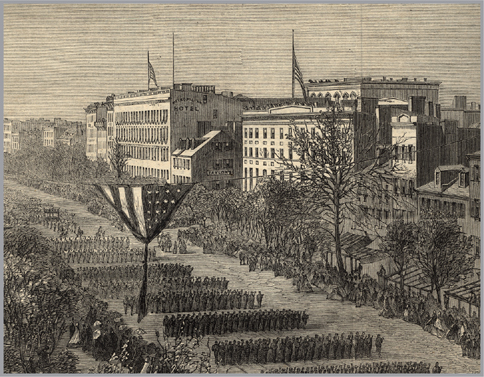

Just weeks after his trip to Richmond, the country mourned Abraham Lincoln in this procession down Washington’s Pennsylvania Avenue on April 19, 1865.

Consider two documents: the handwritten version of Lincoln’s Second Inaugural, and the printed paste-up that served as his actual speaking text. Studied in juxtaposition they mark out segments of a line that begins in compositional privacy—words inscribed on the page by hand, preserving the suggestion of thought being shaped toward public cadence, but still also very clearly the product of one man’s effort to impose deliberation on the surges of strong emotion. The printed text telegraphs not only the transformation of the private occasion into typographic public potential—the next point on the line—but in paste-up seems to convert the fluid nature of the first expression into a sequence to be tracked and performed, moving it not to the idea of speech, but to a speech, with all that that implies about strategy and persuasion. The idea of the line of course continues. We can then imagine the fragmented-looking paste-up, its discrete units of text, dissolving at the edges into impassioned delivery, gathering back to a unity of effect that preserves—possibly even amplifies—the quality of the original occasion, the spirit that first coaxed thoughts into sentences intended for an eventual public, if not for posterity.