“I doubt whether his words would be worth recording, even if I could remember them,” the author Nathaniel Hawthorne reported dismissively after hearing Abraham Lincoln deliver a short speech in the White House in March 1862. Sneering that the president possessed “no bookish cultivation, no refinement,” the novelist would concede only that “Uncle Abe” seemed armed with a “great deal of native sense.” But even Lincoln’s widely celebrated “delectable stories” smacked of “frontier freedom,” Hawthorne complained, and were unfit for polite society.

How could one great writer have so badly misjudged another? The answer wasn’t literary, but political. Hawthorne was a New England Democrat. Of course, neither the Yankee novelist nor other contemporary critics had ever glimpsed Lincoln’s extraordinary—but private and unpublished—meditation on divine will, nor his condolence letter to a bereaved young woman named Fanny McCullough. Nor could they have anticipated the masterpieces yet to come from his pen.

Ironically, the most important document Lincoln ever wrote may have done the most during his lifetime to injure his reputation as a writer. Lincoln crafted the Emancipation Proclamation in meticulous legalese in anticipation of future court challenges to freedom. Its lack of soaring rhetoric disappointed many observers.

It took time, tragedy, and reassessment to modify Lincoln’s reputation as both a statesman and a writer. And that would not come for years. Karl Marx, who had criticized Lincoln’s work as “legal chicaneries and pettifogging stipulations,” himself admitted of the “great and good man” he had failed to appreciate, “the world only discovered him a hero after he had fallen a martyr.”

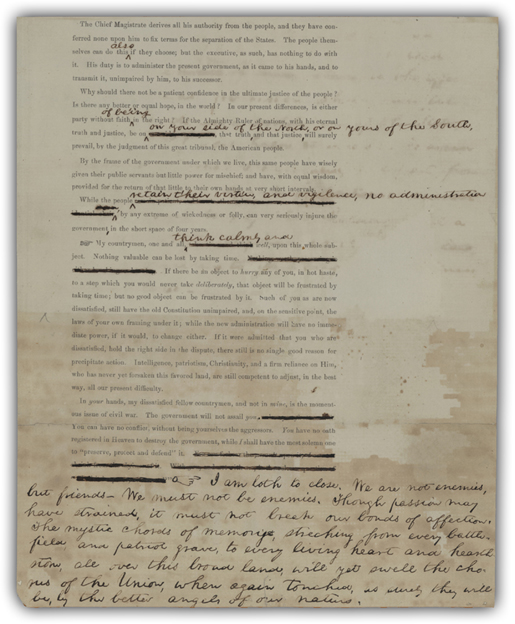

FIRST INAUGURAL ADDRESS, MARCH 4,1861

Lincoln’s first inaugural address ends with perhaps the most famous illustration of his literary mind in motion, as he revised a conciliatory closing paragraph (not shown on the manuscript) that had been drafted by his secretary of state, William Seward.

The Chief Magistrate derives all his authority from the people, and they have conferred none upon him to fix terms for the separation of the States. The people themselves can do this ^ also if they choose; but the executive, as such, has nothing to do with it. His duty is to administer the present government, as it came to his hands, and to transmit it, unimpaired by him, to his successor.

Why should there not be a patient confidence in the ultimate justice of the people? Is there any better, or equal hope, in the world? In our present differences, is either party without faith ^ of being in the right? If the Almighty Ruler of nations, with his eternal truth and justice, be on our side, or on yours, ^ on your side of the North, or on yours of the South, that truth, and that justice, will surely prevail, by the judgment of this great tribunal, the American people.

By the frame of the government under which we live, this same people have wisely given their public servants but little power for mischief: and have, with equal wisdom, provided for the return of that little to their own hands at very short intervals.

While the people ^ retain their virtue, and vigilence, no administration remain patient, and true to themselves, no man, even in the presidential chair ^ can, by any extreme of wickedness or folly, can very seriously injure the government, in the short space of four years.

My countrymen, one and all, ^ think calmly and take time and think well, upon this whole subject. Nothing valuable can be lost by taking time. Nothing worth preserving is either breaking or burning. If there be an object to hurry any of you, in hot haste, to a step which you would never take deliberately, that object will be frustrated by taking time; but no good object can be frustrated by it. Such of you as are now dissatisfied, still have the old Constitution unimpaired, and, on the sensitive point, the laws of your own framing under it; while the new administration will have no immediate power, if it would, to change either. If it were admitted that you who are dissatisfied, hold the right side in the dispute, there still is no single good reason for precipitate action. Intelligence, patriotism, Christianity, and a firm reliance on Him, who has never yet forsaken this favored land, are still competent to adjust, in the best way, all our present difficulty.

In your hands, my dissatisfied fellow countrymen, and not in mine, is the momentous issue of civil war. The government will not assail you. unless you first assail it. You can have no conflict, without being yourselves the aggressors. You have no oath registered in Heaven to destroy the government, while I shall have the most solemn one to “preserve, protect and defend” it. You can forbear, the assault upon it; I can not shrink from the defense of it. With you, and not with me, is the solemn question of “Shall it be peace, or a sword?” I am loth to close. We are not enemies,

but friends. We must not be enemies. Though passion may have strained, it must not break our bonds of affection. The mystic chords of memorys, streching from every battlefield, and patriot grave, to every living heart and hearth-stone, all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature.

The Civil War had not yet begun. In his draft of his first inaugural address, President-elect Lincoln had planned to conclude with a message to his “dissatisfied friends” in the South that the choice of “peace or the sword” was in their hands, and not in his. William Seward, whom Lincoln had beaten for the Republican nomination and after the election had appointed secretary of state, suggested in a letter that this note of defiance be tempered with “a note of fraternal affection,” and submitted language for the penultimate paragraphs:

I close. We are not, we must not be, aliens or enemies, but fellow countrymen and brethren. Although passion has strained our bonds of affection too hardly, they must not, I am sure they will not, be broken. The mystic chords which, proceeding from so many battlefields and so many patriotic graves, pass through all the hearts and all hearths in this broad continent of ours, will yet again harmonize in their ancient music when breathed upon by the guardian angel of the nation.

Lincoln accepted Seward’s idea of seeking to evoke the sentimental ties that could help bind the nation together, and he used Seward’s musical metaphor as well. But he rewrote the suggested passage, lifting it from oratory to poetry.

Do users of political language today make that kind of effort to persaude and inspire? I think not. If they did, would it work? Styles change with the times, and Seward’s florid style may seem excessive to us now, but Lincoln’s improvement produced a soaring simplicity that I believe has what we now call impact.

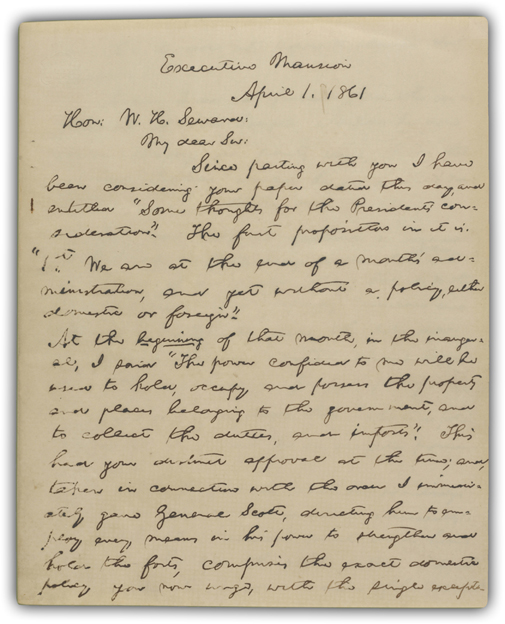

LETTER TO WILLIAM H. SEWARD, APRIL 1, 1861

Lincoln boldly appointed what historian Doris Kearns Goodwin called a “team of rivals” to fill his cabinet, but resisted when Secretary of State William H. Seward attempted to co-opt his authority. As the untested incoming president had confided earlier, “I can’t afford to let Seward take the first trick.”

Click here to see images of the full letter.

April 1, 1861

Hon: W. H. Seward:

My dear Sir:

Since parting with you I have been considering your paper dated this day, and entitled “Some thoughts for the President’s consideration.” The first proposition in it is, “1st. We are at the end of a month’s administration, and yet without a policy, either domestic or foreign.”

At the beginning of that month, in the inaugeral, I said “The power confided to me will be used to hold, occupy and possess the property and places belonging to the government, and to collect the duties, and imports.” This had your distinct approval at the time; and, taken in connection with the order I immediately gave General Scott, directing him to employ every means in his power to strengthen and hold the forts, comprises the exact domestic policy you now urge, with the single exception, on, that it does not propose to abandon Fort Sumpter.

Again, I do not perceive how the re-in forcement of Fort Sumpter would be done on a slavery, or party issue, while that of Fort Pickens would be on a more national, and patriotic one.

The news received yesterday in regard to St. Domingo, certainly brings a new item [???] within the range of our foreign policy; but up to that time we have been preparing circulars, and instructions to ministers, and the like, all in perfect harmony, without even a suggestion that we had no foreign policy. Upon your closing propositions, that “whatever policy we adopt, there must be an energetic prosecution of it”

“For this purpose it must be somebody’s business to pursue and direct it incessantly”

“Either the President must do it himself, and be all the while active in it, or”

“Devolve it on some member of his cabinet”

“Once adopted, debates on it must end, and all agree and abide” I remark that if this must be done, I must do it. When a general line of policy is adopted, I apprehend there is no danger of its being changed without good reason, or continuing to be a subject of unnecessary debate; still, upon points arising in its progress, I wish, and suppose I am entitled to have the advice of all the Cabinet.

Your Obt. Servt.

A. Lincoln

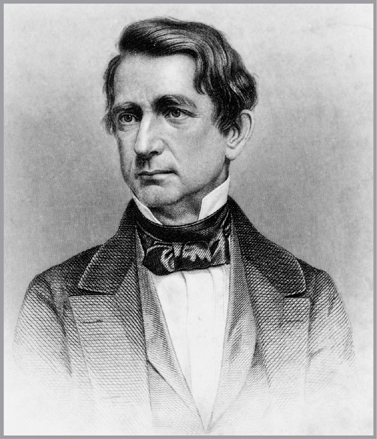

Lincoln believed his Secretary of State, William H. Seward, “seemed to share the fate of the ancient picture placed by the painter in the market-house to be retouched by all caviling critics.”

In due course, President Lincoln’s hands, enlarged by his years of splitting rails and plowing fields, proved big enough to hold the Union together. Yet from the very first of his administration, this icon of principled American leadership was forced to justify himself and his actions even to an intemperate member of his own cabinet.

His rivalry with Seward is long-since acknowledged; but to me what this early letter from our sixteenth president serves to underscore is the innate grace and humility with which Lincoln served—while at the same time forcefully asserting, with even a modicum of panache, the limited powers of the Executive under our Constitution. (Note the underlined “I” for emphasis on the third line of page three.)

Like others to assume the presidency, I was keen to learn from precedence—from the wisdom and, yes, the mistakes of those who had preceded me into high office. I am not alone in that, from Lincoln, I drew plain lessons in propriety, and reserve, and respect for that unique institution into which so many American hopes and dreams have been vested.

President Lincoln once notably spoke of being “driven to (his) knees” by the weight of the decisions only a president can face, and the realization that only a merciful Creator could abide his fondest wish to see the Union preserved.

Still, as we reflect on the remarkable circumstances of his service, it is we, in turn, who should be driven to our knees in gratitude that such a man of fortitude, and quiet conviction, was elevated in due process to deliver our republic from its hour of maximum peril.

Awkward, ungainly perhaps, but in the end also unyielding, Abraham Lincoln’s intellect and reason were the rock, the foundation, upon which a young and searching nation was able to rise above its gravest threat to truly become the “last best, hope of earth.”

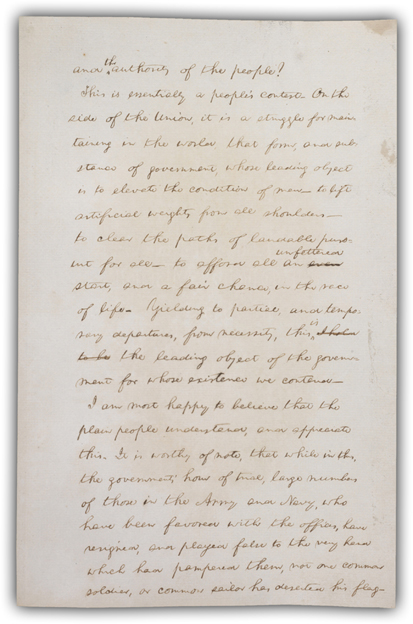

MESSAGE TO CONGRESS, JULY 4, 1861

Lincoln’s first crucial message to Congress—delivered to a special session called for Independence Day—marshaled the national will for war, and began an effort to define that war. “This is essentially a people’s contest,” he argued. Praised in the North, it convinced one Baltimore newspaper that Lincoln was “the equal, in despotic wickedness, of Nero.…” (Excerpt)

Click here to see images of the full letter.

This is essentially a people’s contest. On the side of the Union, it is a struggle for maintaining in the world, that form, and substance of government, whose leading object is to elevate the condition of men — to lift artificial weights from all shoulders — to clear the paths of laudable pursuit for all — to afford all an even unfettered start, and a fair chance, in the race of life. Yielding to partial, and temporary departures, from necessity, this ^ is I hold to be the leading object of the government for whose existence we contend.

I am most happy to believe that the plain people understand, and appreciate this. It is worthy of note, that while in this, the government’s hour of trial, large numbers of those in the Army and Navy, who have been favored with the offices, have resigned, and played false to the very hand which had pampered them, not one common soldier, or common sailor has deserted his flag. Greater honor is due to those officers who remain true, despite the example of their treacherous associates; but the greatest honor, and most important fact ^ of all is, the unanimous firmness of the common soldiers and ^ common sailors. To the last man, they ^ have successfully resisted the traitorous efforts of those, whose commands, but an hour before, they obeyed as absolute law. This is the patriotic instinct of the plain people. They understand, without an argument, that the destroying the government which was made by Washington, means no good to them.

Our popular government has often been called an experiment. Two points in it, our people have already settled — the successful establishing, and the successful administering of it. One still remains — the successful maintainance of it, against a formidable attempt to overthrow it. It is now for them to demonstrate to the world that those who can fairly carry an election, can also suppress a rebellion — that those who can not carry an election, can not destroy the government. — that ballots are the rightful, and peaceful, successor of bullets; and that when ballots have fairly, and constitutionally, decided, there can be no successful appeal, back to bullets. Such will be a great lesson of peace, teaching men that what they can not take by an election, neither can they take it by a war — teaching all the folly of being the beginners of a war

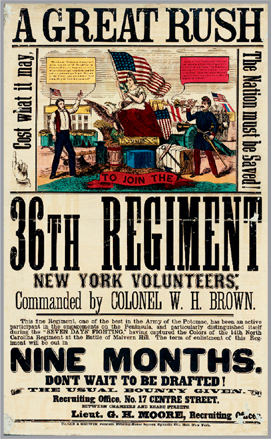

The attack on Fort Sumter, the federal garrison guarding Charleston harbor, ignited war but also inspired artists—and may have elevated morale, not sapped it. When the fort’s badly damaged flag was returned to New York, it was displayed to rally civilians and inspire departing troops.

Lest there be some uneasiness in the minds of candid men, as to what is to be the course of the government, towards the Southern states, after the rebellion shall have been suppressed, the executive deems it proper to say it will be his purpose, then as ever, to be guided by the Constitution, and the laws; and that he probably will have no different understanding of the powers, and duties of the Federal government, relative to the rights of the States, and the people, under the Constitution, than that expressed in the inaugural address.

The resulting damage to Fort Sumter’s American flag ignited what was called “flag mania” in the North, an outpouring of banners and artistic renderings designed to fan patriotic flames and inspire a commitment to armed response. This Currier & Ives print invoked both Union martyrs and God’s blessings.

On July 4, 1861, Abraham Lincoln convened a special session of Congress unlike any other in history. In the preceding months, eleven states had seceded from the Union. Rebel forces had fired on Fort Sumter. And now an anxious nation looked to the prairie lawyer from Springfield to rise to the challenge.

In his Independence Day message to Congress, Lincoln answered his skeptics with resolve and eloquence. Drawing on his knowledge of history, he refuted the argument for secession. He asked Congress to provide the resources needed to preserve the Union. And to those who might question the cost, he wrote, “A right result, at this time, will be worth more to the world, than ten times the men, and ten times the money.”

From the beginning, Lincoln understood that the outcome of America’s Civil War would reverberate far beyond America’s borders. In his message, Lincoln described the battle to save the Union as a struggle for the future of democracy around the world. As the years passed, Americans would grow to realize the wisdom of their president’s words. And as slaves claimed their God-given right to freedom, America would grow into the more perfect union that Lincoln had always envisioned.

Lincoln’s Message to Congress is remembered for describing the Civil War as “a people’s contest.” And thanks to the leadership of America’s sixteenth president, government of the people, by the people, for the people prevailed.

This early broadside promoting nine-month enlistments stressed patriotism but hinted darkly—and accurately—at future conscription.

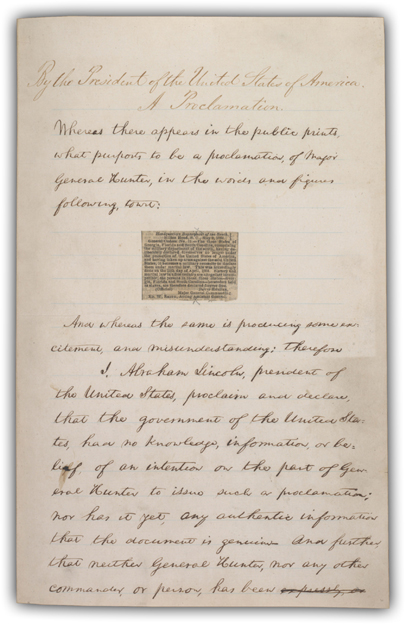

PROCLAMATION REVOKING GEN. HUNTER’S EMANCIPATION ORDER, MAY 19, 1862

Lincoln seldom combined legalese and poetry in a single document, but in revoking a Civil War general’s precipitant order confiscating local slaves—a right Lincoln held to himself— the president ingeniously appealed to both the law and the heart. (Excerpt)

By the President of the United States of America.

A Proclamation.

Whereas there appears in the public prints, what purports to be a proclamation, of Major General Hunter, in the words and figures following, towit:

Headquarters Department of the South,}

Hilton Head, S.C., May 9, 1862.}

General Orders No. 11.— The three States of Georgia, Florida and South Carolina, comprising the military department of the south, having deliberately declared themselves no longer under the protection of the United States of America, and having taken up arms against the said United States, it becomes a military necessity to declare them under martial law. This was accordingly done on the 25th day of April, 1862. Slavery and martial law in a free country are altogether incompatible; the persons in these three States—Georgia, Florida and South Carolina— heretofore held as slaves, are therefore declared forever free. (Official) DAVID HUNTER,

Major General Commanding.

ED. W. SMITH, Acting Assistant General.

And whereas the same is producing some excitement, and misunderstanding: therefore

I, Abraham Lincoln, president of the United States, proclaim and declare, that the government of the United States, had no knowledge, information, or belief, of an intention on the part of General Hunter to issue such a proclamation; nor has it yet, any authentic information that the document is genuine. And further, that neither General Hunter, nor any other commander, or person, has been expressly, or

When Lincoln’s friend, Major General David Hunter, ordered slaves in Georgia, Florida, and South Carolina “forever free,” the President learned about it from the press.

Lincoln revoked the initiative at once, telling Secretary of the Treasury Salmon P. Chase: “No commanding general shall do such a thing, upon my responsibility, without consulting me.”

The revocation showed the lawyer/president at his best. Drafted as a legal document, the commander in chief even pasted Hunter’s order from a newspaper onto the center of the first page—shown here—then explained his determination to override it. Any such exercise of power, “I reserve to myself.” The emancipator-in-waiting declares that emancipation cannot yet be undertaken at this time (though by July, he had drafted an Emancipation Proclamation of his own). For now, he again urges gradual, compensated emancipation, asserting the plan “makes common cause for a common object, casting no reproaches on any.”

And he ends with a flourish, looking not to Hunter’s recent indiscretion but to his own plans for “the vast future”: “The change it contemplates would come gently as the dews of heaven.… Will you not embrace it? So much good has not been done, by one effort, in all past time, as in the providence of God, it is now your high privilege to do.”

This is Abraham Lincoln at his best—judicious, tough, eloquent, and yet open to mediation, using “all the … means of persuasion.…”

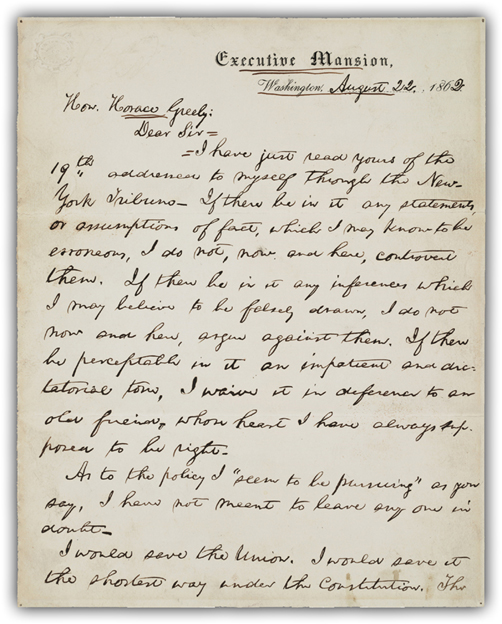

REPLY TO HORACE GREELEY’S EDITORIAL, AUGUST 22, 1862

Even after he had composed his Emancipation Proclamation, Lincoln publicly maintained—in this enigmatic reply to the irascible newspaperman Horace Greeley—his primary commitment to the preservation of the Union and the secondary consideration of slavery. This was, he said, his official duty, though not necessarily his personal wish.

Click here to see images of the full letter.

Washington, August 22, 1862.

Hon. Horace Greely:

Dear Sir -

-I have just read yours of the 19th addressed to myself through the New-York Tribune. If there be in it any statements, or assumptions of fact, which I may know to be erroneous, I do not, now and here, controvert them. If there be in it any inferences which I may believe to be falsely drawn, I do not now and here, argue against them. If there be perceptable in it an impatient and dictatorial tone, I waive it in deference to an old friend, whose heart I have always supposed to be right.

As to the policy I “seem to be pursuing” as you say, I have not meant to leave any one in doubt.

I would save the Union. I would save it the shortest way under the Constitution. The sooner the national authority can be restored, the nearer the Union will be “the Union as it was.” Broken eggs can never be mended, and the longer the breaking process, the more will be broken. If there be ^ those any who would not save the Union, unless they could at the same time save slavery, I do not agree with them. If there be any those who would not save the Union unless they could at the same time destroy slavery, I do not agree with them. My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and is not either to save or to destroy slavery. If I could save the Union without freeing any slave I would do, it, and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone I would also do that. What I do about slavery, and the colored race, I do because I believe it helps to save the Union; and what I forbear, I forbear because I do not believe it would help to save the Union. I shall do less whenever I shall believe what I am doing hurts the cause, and I shall do more whenever I shall believe doing more will help the cause. I shall try to correct errors when shown to be errors; and I shall adopt new views so fast as they shall appear to be true views.

I have here stated my purpose according to my view of official duty; and I intend no modification of my oft-expressed personal wish that all men everywhere could be free.

Yours,

A. Lincoln

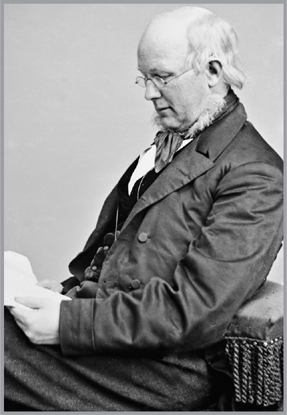

New York Tribune editor Horace Greeley at first thought Lincoln “true and right, but not a Jackson or Clay.”

Grinding his pills and potions, “pharmacist” Lincoln searches for the perfect cure to restore the country’s health. Crude so-called patriotic envelopes like this one were immensely popular on the home front.

In the late summer of 1862 Lincoln faced steady criticism for Union military failures in Virginia and for his apparent indecision on the issue of slave emancipation. On August 20, Horace Greeley, the founder and editor of the New York Tribune, the most influential newspaper in America, published a nine-part indictment of Lincoln under the title, “The Prayer of Twenty Millions.” Raining a hail of invective on Lincoln, Greeley demanded that he enforce the Second Confiscation Act, passed by Congress the previous month and authorizing the president to free the slaves as enemy property.

Beautiful in its brevity and gracious in tone, Lincoln’s famous, enigmatic response of August 22, published in the pro-Union but also pro-slavery National Intelligencer, was a deft work of political propaganda; indeed it may have been intentionally misleading. After all, on July 22 Lincoln had informed his cabinet that he intended to issue an emancipation order. He was waiting only for a military victory, so as to avoid the appearance of desperation.

After a cordial opening paragraph, Lincoln made his case in two remarkable paragraphs that people have chosen to read in vastly different ways. Was this the emancipator in the making, awaiting his moment of truth? Or was this the conservative Republican who preferred to restore the Union without destroying slavery? Or was it both the moderate—now moved by events and older moral convictions about slavery—and the wily politician educating the public up to its historical duty? The one thing he made clear is that the “paramount object … the cause” was to save the Union. To Lincoln, though, emancipation had become both a means and an end.

In its context the letter demonstrates that both Lincoln and Greeley eventually agreed that defeat of the Confederacy and emancipation were now mutually necessary and dependent. The sentence edited out by the National Intelligencer contained the homespun metaphor of “broken eggs.” He had taken his time, but Lincoln was now willing to break as many eggs as it took to crush the rebellion.

In the final sentence Lincoln also made the distinction between his “official duty” and his “personal wish” that all could be free. Lincoln’s multilayered temperament was a house with many doors. The Greeley letter, like few other works in Lincoln’s writings, demonstrates how many choices we have in entering that house.

MEDITATION ON THE DIVINE WILL, CA. SEPTEMBER 1862

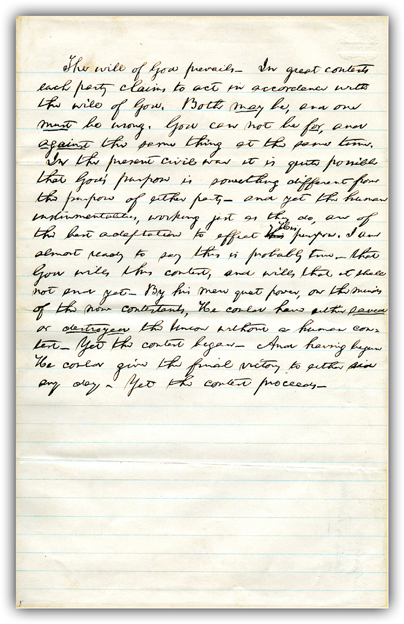

The thorny question of God’s will in relation to the Civil War nagged at Lincoln as the conflict mounted. In this private note, discovered only after his death, he staked out a theologically rigorous position. Notice how the tone changes in the second half, after the one strike-out (the word “this”) when he moved from declaring his certainties to wrestling with the ultimate question.

The will of God prevails. In great contests each party claims to act in accordance with the will of God. Both may be, and one must be wrong. God can not be for, and against the same thing at the same time. In the present civil war it is quite possible that God’s purpose is something different from the purpose of either party — and yet the human instrumentalities, working just as they do, are of the best adaptation to effect this His purpose. I am almost ready to say this is probably true — that God wills this contest, and wills that it shall not end yet. By his mere quiet power, on the minds of the now contestants, He could have either saved or destroyed the Union without a human contest. Yet the contest began. And having begun He could give the final victory to either side any day. Yet the contest proceeds.

There is no addressee or context given that precipitated this memorandum, but it is very troubling to me. Although the detached objectivity and humor of Abraham Lincoln are clear in his assessment of the “will of God,” his strong insinuation is that it was God’s unfathomable will that caused the beginning and continuation of the horrendous War between the States.

There is no doubt that many conflicts are initiated because combatants are convinced that they are implementing particular and misguided interpretations of Christianity, Islam, Judaism, or other prevalent religions and that they are acting on behalf of the Almighty. In order to arouse or strengthen support, it is a major responsibility for political and military leaders to inculcate both soldiers and civilians with this sense of self-righteousness. At least in this brief presentation, Lincoln refrained from doing so. Rather than exalt the unique morality of his own cause as commander in chief of the Union army, Lincoln acknowledges the legitimacy, or inevitability, of both sides claiming to be acting in good faith.

He ignores the fact that the tragic combat might have been avoided altogether, and that the leaders of both sides, overwhelmingly Christian, were violating a basic premise of their belief as followers of the Prince of Peace. His subtle purpose may have been to disparage the fervent proponents of this faith.

A legitimate question for historians is how soon the blight of slavery would have been terminated peacefully in America, as in Great Britain and other civilized societies.

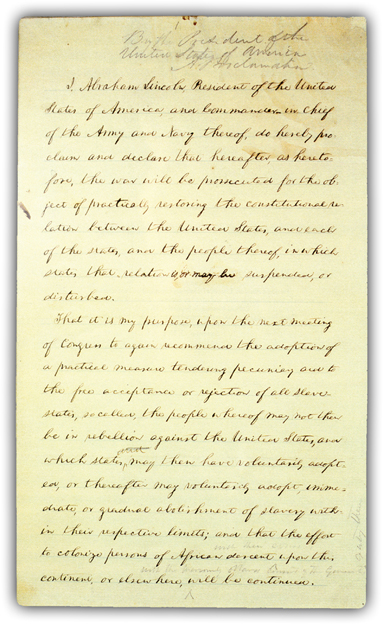

PRELIMINARY EMANCIPATION PROCLAMATION, SEPTEMBER 22, 1862

Lincoln wrote—and pasted together (one glued section seems to bear his fingerprint!)— this history-altering preliminary Emancipation Proclamation sometime in September 1862. Later donated to a New York charity fair, it was eventually acquired and preserved by the state. It is the only surviving copy of Lincoln’s most important document in his own hand; the manuscript of the final proclamation burned in the Chicago fire.

Click here to see images of the full letter.

United States of America

A Proclamation.

I, Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States of America, and Commander-in-Chief of the Army and Navy thereof, do hereby proclaim and declare that hereafter, as heretofore, the war will be prossecuted for the object of practically restoring the constitutional relation between the United States, and each of the states, and the people thereof, in which states that relation is, or may be suspended, or disturbed.

That it is my purpose, upon the next meeting of Congress to again recommend the adoption of a practical measure tendering pecuniary aid to the free acceptance or rejection of all slave-states, so called, the people whereof may not then be in rebellion against the United States, and which states, ^ and may then have voluntarily adopted, or thereafter may voluntarily adopt, immediate, or gradual abolishment of slavery within their respective limits; and that the effort to colonize persons of African descent, ^ with their consent, upon this continent, or elsewhere, ^ with the previously obtained consent of the Governments existing there, will be continued.

German-born expressionist painter David Gilmour Blythe viewed Lincoln as a liberator who drew inspiration from sacred sources—like the Bible and the Constitution—to write the Emancipation Proclamation. This print adaptation was issued in 1864 in Pittsburgh.

That on the first day of January in the year of our Lord, one thousand eight hundred and sixty-three, all persons held as slaves within any state, or designated part of a state, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free; and the executive government of the United States, ^ including the military and naval authority thereof, will during the continuance in office of the presen[?????] recognize ^ and maintain the freedom of such persons, as being free, and will do no act or acts to repress such persons, or any of them, in any efforts they may make for their actual freedom.

Another German artist—Adalbert Volck, a Confederate sympathizer in Baltimore—conversely argued that Lincoln’s proclamation was inspired by sinister sources like John Brown, Satan, and alcohol.

That the executive will, on the first day of January aforesaid, by proclamation, designate the States, and parts of states, if any, in which the people thereof respectively, shall then be in rebellion against the United States; and the fact that any state, or the people thereof shall, on that day be, in good faith represented in the Congress of the United States, by members chosen thereto, at elections wherein a majority of the qualified voters of such state shall have participated, shall, in the absence of strong countervailing testimony, be deemed conclusive evidence that such state and the people thereof, are not then in rebellion against the United States.

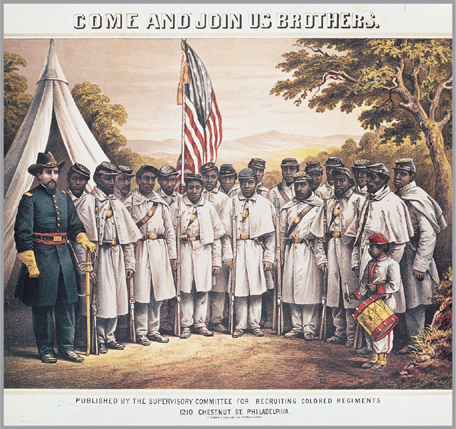

Lincoln’s final Emancipation Proclamation added a call for black enlistment. Recruiting posters like this one showed people of color in a dignified light, a rarity until then.

That attention is hereby called to an act of Congress entitled “An act to make an additional Article of War” approved March 13, 1862, and which act is in the words and figure following:

Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That hereafter the following shall be promulgated as an additional article of war for the government of the army of the United States, and shall be obeyed and observed as such:

Article—. All officers or persons in the military or naval service of the United States are prohibited from employing any of the forces under their respective commands for the purpose of returning fugitives from service or labor, who may have escaped from any persons to whom such service or labor is claimed to be due, and any officer who shall be found guilty by a court-martial of violating this article shall be dismissed from the service.

SEC. 2. And be it further enacted, That this act shall take effect from and after its passage.

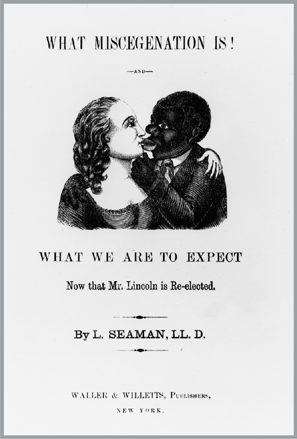

Critics warned Lincoln was a dictator intent on ushering in an era of “miscegenation”—a newly invented word for race mixing.

Also to the ninth and tenth sections of an act entitled “An Act to suppress Insurrection, to punish Treason and Rebellion, to seize and confiscate property of rebels, and for other purposes,” approved July 17, 1862, and which sections are in the words and figures following:

SEC. 9. And be it further enacted, That all slaves of persons who shall hereafter be engaged in rebellion against the government of the United States, or who shall in any way give aid or comfort thereto, escaping from such persons and taking refuge within the lines of the army; and all slaves captured from such persons or deserted by them and coming under the control of the government of the United States; and all slaves of such persons found on (or) being within any place occupied by rebel forces and afterwards occupied by the forces of the United States, shall be deemed captives of war, and shall be forever free of their servitude and not again held as slaves.

SEC. 10. And be it further enacted, That no slave escaping into any State, Territory, or the District of Columbia, from any other State, shall be delivered up, or in any way impeded or hindered of his liberty, except for crime, or some offence against the laws, unless the person claiming said fugitive shall first make oath that the person to whom the labor or service of such fugitive is alleged to be due is his lawful owner, and has not borne arms against the United States in the present rebellion, nor in any way given aid and comfort thereto; and no person engaged in the military or naval service of the United States shall, under any pretence whatever, assume to decide on the validity of the claim of any person to the service or labor of any other person, or surrender up any such person to the claimant, on pain of being dismissed from the service.

However dry its intentionally legalistic language, Lincoln’s society-altering final proclamation, issued January 1, 1863, inspired colorful, display-worthy renderings to decorate homes and political clubs.

And I do hereby enjoin upon and order all persons engaged in the military and naval service of the United States to observe, obey, and enforce, within their respective spheres of service, the act, and sections above recited.

And the executive will ^ in due time at the next [????] recommend that all citizens of the United States who shall have remained loyal thereto throughout the rebellion, shall (upon the restoration of the constitutional relation between the United States, and their respective states, and people, if that relation shall have been suspended or disturbed) be compensated for all losses by acts of the United States, including the loss of slaves.

In witness whereof, I have hereunto set my hand, and caused the seal of the United States to be affixed.

Done at the City of Washington, this twenty second day of September,

in the year of our Lord, one thousand, eight hundred and sixty two, and sixty two and of the Independence of the United States, the eighty seventh.

Abraham Lincoln

By the President

William H. Seward,

Secretary of State

The Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation of September 22, 1862, was based firmly on legislative and executive authority. As commander in chief of the army and navy, Lincoln refers to his military powers as the source of his authority to emancipate the slaves. This power was to be used to prosecute the war in order to restore the Union. With this document, setting the slaves free became an important means of accomplishing this end. Lincoln hoped, finally, to bring about legislative and executive cooperation with a view to developing a plan of emancipation in states that were not in rebellion. The body of the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation is in Lincoln’s own hand—with sections pasted in, and bearing fingerprints (are they his?)—and the final beginning and ending in the hand of the chief clerk. The precious document was presented by the president to the Albany Army Relief Bazaar held in February and March 1864. Gerrit Smith, the abolitionist leader, purchased it for $1,000 and gave it to the United States Sanitary Commission. Then in April 1865 the New York State Legislature appropriated $1,000 for its purchase and it was placed in the State Library—in whose possession it remains. Thank goodness for Gerrit Smith. Lincoln’s handwritten copy of the final proclamation, by contrast, was lost. The president donated it to a charity fair in Chicago; there it remained, and there it later burned in the great fire.

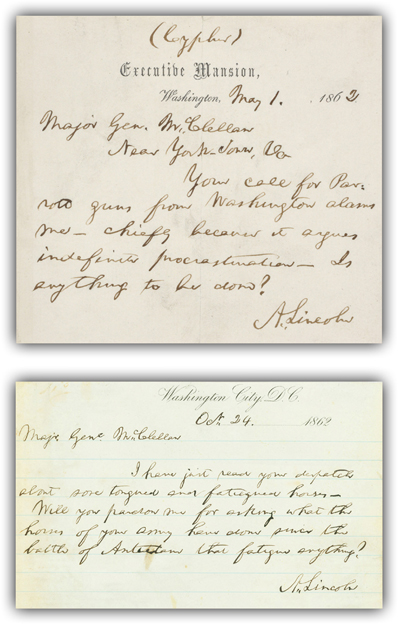

TWO TELEGRAMS TO GEN. GEORGE B. MCCLELLAN, MAY 1, 1862 AND OCTOBER 24, 1862

Lincoln’s frustration with George McClellan, his quick-to-talk and slow-to-act Union general, had many expressions. Here, perhaps, is its literary apogee, as the president’s directness and concision underscore his urgency for decisive military action.

Executive Mansion,

Washington, May 1. 1862

Major Gen. McClellan

New York-Town, Va

Your call for Parrott guns from Washington alarms me — chiefly because it argues indefinite procrastination. Is anything to be done?

A. Lincoln

Washington City, D.C.

Oct. 24. 1862

Majr. Genl. McClellan

I have just read your dispatch about sore tongued and fatigued horses. Will you pardon me for asking what the horses of your army have done since the battle of Antietam that fatigued anything?

A. Lincoln

These telegrams express Lincoln’s intense and growing frustration with General George B. McClellan’s endless delays and excuses for inaction in two campaigns against the enemy separated by six months and two hundred miles. In March 1862 McClellan persuaded Lincoln to approve his strategy of taking the Army of the Potomac all the way down the Potomac River and Chesapeake Bay to the tip of the Virginia peninsula at Hampton Roads for a flanking campaign against Richmond. Lincoln had instead favored direct operations against the enemy in his defensive works at Manassas only twenty-five miles from Washington, but deferred to his subordinate’s supposedly superior professional military knowledge. Once McClellan arrived at Hampton Roads, the president urged him to drive quickly up the peninsula before the enemy commander, Joseph E. Johnston, could transfer his army to block McClellan’s advance. “I think you better break the enemies’ line from York-town to Warwick River, at once,” Lincoln wired McClellan on April 6, when the Union commander had 70,000 men on this line facing only 17,000 Confederates.

Instead, McClellan settled down for a monthlong siege, calling for more big guns to blast the enemy out of his defenses. This long delay prompted Lincoln’s May 1 telegram deploring the general’s “indefinite procrastination.”

Indefinite procrastination became McClellan’s hallmark, earning him the nickname “Tardy George.” Enemy commander Robert E. Lee, who took over the Army of Northern Virginia on June 1, 1862, repeatedly outwitted and outmaneuvered McClellan during the summer of 1862 and invaded Maryland in September. McClellan turned him back in the battle of Antietam on September 17, but then failed to follow up that limited victory with a vigorous pursuit despite Lincoln’s pleas and orders to “destroy the rebel army, if possible.” McClellan sent a steady stream of complaints and excuses to Washington, including a dispatch about fatigued and sore-tongued horses. Already stretched to the limit, Lincoln’s patience snapped, and he fired back this sarcastic telegram. McClellan said that Lincoln’s message made him as “mad as a ‘march hare.’ ” It should have warned him that his tenure as commander of the Army of the Potomac would end unless he got moving. He did, but with his usual sluggishness. Two weeks later Lincoln finally removed him from command.

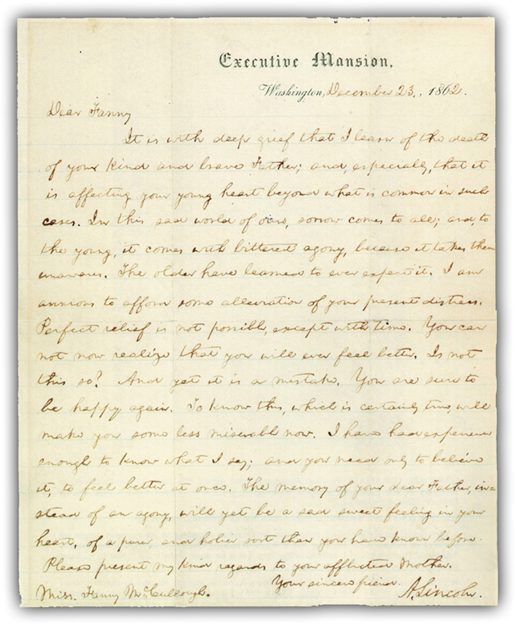

LETTER TO Fanny McCullough, DECEMBER 23, 1862

The casualties of the Civil War grieved and rattled Lincoln. Yet, in his condolence letters, he captured an empathetic grace. One other gem attributed to him—the letter to Lydia Bixby—has never been found in its original form, and some scholars have questioned its authenticity. This one is unquestionably in the hand and from the mind of Lincoln.

Washington, December 23, 1862.

Dear Fanny

It is with deep grief that I learn of the death of your kind and brave Father; and, especially, that it is affecting your young heart beyond what is common in such cases. In this sad world of ours, sorrow comes to all; and, to the young, it comes with bitterest agony, because it takes them unawares. The older have learned to ever expect it. I am anxious to afford some alleviation of your present distress. Perfect relief is not possible, except with time. You can not now realize that you will ever feel better. Is not this so? And yet it is a mistake. You are sure to be happy again. To know this, which is certainly true, will make you some less miserable now. I have had experience enough to know what I say; and you need only to believe it, to feel better at once. The memory of your dear Father, instead of an agony, will yet be a sad sweet feeling in your heart, of a purer, and holier sort than you have known before. Please present my kind regards to your afflicted mother.

Your sincere friend

Miss. Fanny McCullough. A. Lincoln.

Often Lincoln wrote of the consolation of lives given to the nation, but here his words of sympathy are entirely personal, with no invocation of larger purposes of patriotism or sacrifice.

Lincoln was well acquainted with Lt. Colonel McCullough, an Illinois sheriff and court clerk, and had in fact interceded to gain McCullough’s acceptance into the army in spite of his serious physical disabilities: partial blindness and a crippled arm. On December 5, 1862, McCullough was shot in the chest leading an assault in Coffeeville, Mississippi.

Lincoln writes to Fanny, reported to be too distressed to eat or sleep, of his own experience with grief, an experience that stretched from his mother’s death when he was ten to the loss of his beloved eleven-year-old son, Willie, from typhoid just months earlier. And Lincoln felt the burden of the deaths of hundreds of thousands of men he would never know by name, men who, like McCullough, had so eagerly followed their commander in chief into war.

The Civil War brought a harvest of death to the United States, killing approximately two percent of the population of North and South, the proportional equivalent of six million men in our own time. Lincoln wrote to Fanny as the chief executive of a suffering republic, just ten days after a costly Union defeat at Fredericksburg, which yielded more than 12,000 Northern casualties.

Lincoln would spend Christmas Day visiting the sick and wounded in Washington’s military hospitals. He knew more fully and compassionately than young Fanny could yet understand that “sorrow comes to all.”

Though hard to identify, Abraham Lincoln stands under a makeshift wooden canopy outside the U.S. Capitol as he waits to deliver his first inaugural address on March 4, 1861. Eyewitnesses testified that the crowd was the largest ever to gather for a presidential swearing-in.

A program for the 1861 inaugural ball. Mary Lincoln entered the event on the arm of her husband’s defeated opponent, Stephen A. Douglas.

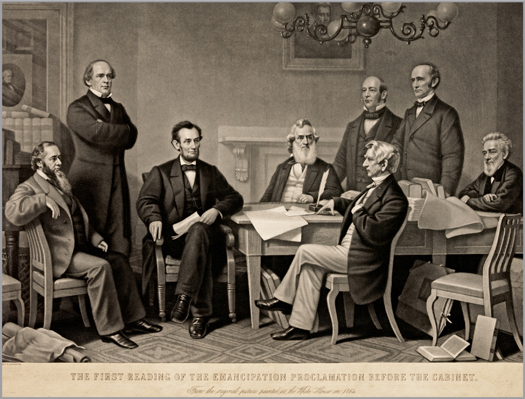

The Lincoln cabinet—composed of former rivals for the Republican presidential nomination who conveniently also represented different sections of the country, as well as varied political roots (both Whig and Democratic)—has sometimes been called the most gifted such team in presidential history. This engraving is based on an 1864 painting depicting the first reading of the Emancipation Proclamation.