I discuss how each macronutrient (protein, carbohydrate, fat, and the “fourth fuel” ketones) affects your eating strategy, energy levels, and overall health. Protein starts the discussion because of its essential role in building and repairing body tissues. It’s easy to obtain enough protein for health: you can determine how many grams you need per day, on average, with a simple calculation based on lean body mass. The wildly excessive carbohydrate intake characteristic of the Standard American Diet can largely be corrected by ditching sugars and grains in favor of choosing high-nutrient-value carbohydrates. Weight-loss goals can be targeted by honoring the ranges on the Primal Blueprint Carbohydrate Curve. With protein intake optimized and carb intake moderated, fat becomes the predominant macronutrient source, and the main variable for achieving satiety and satisfaction at meals.

While you likely have a basic understanding of what carbohydrate, protein, and fat do in the body, it’s important to examine the role of each nutrient further from a Primal Blueprint perspective. This is particularly true in light of the massive misinformation, distortion, and confusion presented by opposing camps on the issue of the optimal macronutrient balance in the diet.

The concept of “calories in, calories out” fails to account for how different foods influence your appetite and metabolic hormones.

Most popular diets and exercise programs targeting fat loss adopt an oversimplified “calories in, calories out” approach, failing to understand the importance of hormones and other variables that influence whether your body stores or burns the calories you ingest (and whether you feel famished or satiated in the process). The macronutrients you consume are not just burned or stored for use as energy later, but also for basic health maintenance and assorted hormonal functions. Moreover, the body can store fuel (and act as a toxic “waist” site), and it has the capacity to generate its own energy, depending largely on the hormonal signals it gets from your behaviors. Since your body always seeks to achieve homeostasis (balance), the notion of you trying to zero in on a precise day-to-day or meal-to-meal eating plan is generally fruitless, not to mention incredibly frustrating and demotivating. Your body does a great job of adjusting to variations in caloric intake and energy expenditure through an assortment of hormonal and genetic processes that will always supersede your diligent efforts to calculate food and exercise calories.

To figure your true structural and functional fuel needs (and, hence, to achieve your body composition goals), it’s important to understand how the major macronutrients work in the body—or should work when you eat in a manner aligned with optimal gene expression.

Protein is essential for building and repairing body tissues and for overall healthy function. Unlike the wildly varying opinions about the role of fat and carbohydrate in the diet, there has long been a general consensus among nutritionists, medical experts and fitness experts on recommended average daily protein intake. However, as I’ll detail shortly, recent research has called into question whether we might be recommending more protein intake than necessary, and I have recently lowered the recommendations that I published in the original Primal Blueprint in 2009.

It’s clear that there is a minimum protein requirement to ensure the healthy functioning of your organs, skeleton, muscles, and numerous body systems. This is believed to be in the neighborhood of .5 grams per pound (1.1 grams per kilo) of lean body mass. Some resources calculate your recommended protein intake off your total body weight. The U.S. RDA to meet your basic nutritional needs is listed at .36 grams per pound of total bodyweight (.8 grams per kilo). By comparison, if one were at 20 percent body fat, this would land right around that .5 grams per pound of lean mass calculation. Beyond your basic needs, conventional wisdom promotes the idea that your protein needs escalate in tandem with your activity level. Moderately active folks are encouraged to obtain an average of .7 grams for pound of lean mass (1.5 grams per kilo), while highly active people are encouraged to obtain an average of 1 gram per pound of lean mass (2.2 grams per kilo). Certain other populations like growing humans and pregnant or lactating mothers are encouraged to shoot for the high end on protein consumption.

The “average” concept is important here, as the body is adept at compensating for variations in daily and even seasonal caloric intake. Our ancestors endured long periods of time with insufficient protein and low total calories and managed to survive those tough winters or fruitless hunts well enough to perpetuate the human race for hundreds of thousands of years. They also had bountiful times where they may have consumed well in excess of their minimum requirements, likely fattening up for a rough winter on the horizon. Your eating patterns will likely not have such dramatic highs and lows, of course. The point is that it’s unnecessary to stress about your protein intake at every meal if you are getting an appropriate amount over the course of a week or a month.

A pattern of excess protein intake accelerates aging and increases cancer risk.

The original Primal Blueprint position was to fall in line with the widely-touted recommended range of .5 grams (1.1 grams/kilo) to meet basic needs, .7 grams (1.5 grams/kilo) for the moderately active, and one gram per pound of lean mass (2.2 grams per kilo) for active exercisers. Mounting research now suggests that we might be overestimating our protein requirements to our detriment. Dr. Ron Rosedale, a leading voice in the concerns about excess protein, suggests that .5 grams of protein per pound of lean mass is plenty for everyone. He believes that even high-protein-demand people (the highly active, growing teens, and pregnant women) need only to add 5 to 10 grams per day to that calculation to ensure optimal protein intake.

Surprising research reveals that strength training actually makes you more efficient with protein—you’ll do more with less thanks to your fitness efforts. However, you can also get away with consuming extra protein without suffering the negative effects we’ll discuss shortly. You can handle eating more protein, but you don’t really need it. Dr. Rosedale and other experts assert that striving to obtain the widely recommended higher levels has the potential to reduce life span and increases the risk of various forms of cancer.

Calculating Lean Body Mass

You can calculate your lean body mass by subtracting your fat weight from your total weight. First, estimate your body fat percentage if you don’t actually know it. A fit male is around 15 percent body fat and a fit female is around 22 percent; a moderately fit male is around 22 percent body fat and a moderately fit female is around 30percent. Alternatively, you can get your body fat measured with the reliable equipment available at many gyms and health care facilities. Armed with your estimate, multiply your body fat percentage by your total weight to get your fat weight, and then subtract that figure from your total weight. What remains is your lean body mass. For example, I weigh 170 pounds (77 kilos) at 10 percent body fat. So my fat weight is 17 pounds (8 kilos), and my lean body mass is 153 pounds (70 kilos). Even at my high activity level, I thrive with a conservative average daily protein intake level of .5 grams per pound of lean mass, or 76 grams per day. See Chapter 10 for a detailed macronutrient analysis of my diet over a three-day period.

When you slam your body with excess protein—more than it needs to fulfill the growth and repair functions that are the primary uses for protein—it works hard to either excrete it or convert it into carbohydrates via gluconeogenesis, which are then used for energy (or, if you’re in a calorie surplus, stored as fat). That’s right: when you eat more protein than your body needs, you either make sugar out of it or produce nitrogen waste products that stress the kidneys charged with excreting the excess.

The conversion of excess protein into glucose will compromise your fat-loss goals, and essentially make anything considered a high-protein diet to be a high-carbohydrate diet in reality (due to gluconeogenesis). What’s more, excess protein consumption continually primes you for accelerated cellular division and growth, instead of the more natural pattern of varying between anabolic (repair, rejuvenation, growth), catabolic (breakdown from exercise and life stressors), and metabolic (normal chemical reactions producing energy). This is why athletes, especially bodybuilders looking to gain mass or athletes training in chronic patterns and struggling to recover each day, are obsessed with protein reloading to promote a continued anabolic state.

Consuming protein stimulates a kinase called mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin), a key component of an extremely complicated signaling network that regulates cellular growth and proliferation by synthesizing information related to energy input and output, endogenous growth factors, nutrient availability, and stress. While mTOR is crucial for normal cellular growth, emerging research shows that enhanced mTOR stimulation (as happens, for example, when you follow a pattern of excess protein consumption) is associated with obesity, cancer, diabetes, insulin resistance, osteoporosis (via urinary calcium loss), kidney dysfunction (due to the stress of excreting nitrogen), and the aging process itself. On the flip side, laboratory studies on mice and observational studies of very long-lived humans suggest that decreased mTOR signaling (a great way to achieve this is through calorie restriction) is associated with longer life spans.

Excess protein intake helps bodybuilders to recover and build more and more muscle, decreasing life span in the process. Just sayin’…

The fact is, when you accelerate cell division, you accelerate aging. Bodybuilders might not care as they pursue ever-larger muscles, and chronic exercisers might be more concerned with muscle recovery than the adverse health consequences of their obsessive refueling, but over-fueling is simply not aligned with health or longevity. By the way, the consumption of excess carbohydrates also gives cells too much fuel over the long term, accelerating cell division and increasing the risk of cell mutation and cancer because excess glucose promotes glycation, oxidation, and inflammation. And as you know, carbohydrates also stimulate insulin release, which itself activates mTOR.

It’s true that some research shows that high-protein diets have a slight advantage for weight loss. This is probably partly because eating a lot of protein makes you feel full, which can lead to eating fewer calories overall. It might also be partially due to the inefficient, energy-guzzling process of converting protein to glucose and then to fat. (Your body burns more calories to convert protein to usable energy, promoting weight loss.) Frankly, I suspect the effect is largely attributable not to the increased protein per se but to the reduction in carbohydrates, especially sugary processed foods, and the resulting increase in insulin and leptin sensitivity (which have been directly implicated in weight management).

As we will cover in more detail in Chapter 9—A Primal Approach to Weight Loss, the simple path to losing excess body fat (without harming your long-term health in the process) is to limit your carb intake in accordance with the Primal Blueprint Carbohydrate Curve, optimize protein intake by landing closer to .5 grams per pound of lean body mass (I believe it’s okay to average a bit higher than that, but don’t go to excess just because you are active), and finally to eat just enough dietary fat in order to feel satisfied and energized.

With your macronutrients dialed in, you will effortlessly obtain additional caloric energy from stored body fat until you attain your ideal body composition.

If you’ve forgotten everything you ever learned in biology, just remember this: carbohydrate controls insulin; insulin controls fat storage. (The full story is a bit more nuanced, of course, but when it comes to understanding how food affects your body weight, this is the most critical take-home point.) Carbohydrates are not used as structural components in the body; instead, they are used only as a form of fuel, whether burned immediately while passing by different organs and muscles or stored for later use. All forms of carbohydrates you eat, whether simple or complex, are rapidly converted into glucose upon ingestion. For reference, a little less than one teaspoon of glucose dissolved in the entire blood volume of your body (about five quarts in the case of a 160-pound male) represents an optimal level of blood glucose.

Humans survived for 2.5 million years on extremely minimal carbohydrate intake, until we were suddenly bombarded with massive amounts of carbs with the advent of civilization.

As you learned in Chapter 3, it’s insulin’s job to take glucose out of the bloodstream and put it somewhere fast. In most healthy people, glucose that is not burned immediately will first be stored as glycogen in muscle and liver cells. When these sites are full, glucose is converted into triglycerides and stored in fat cells. Unless you deplete lots of muscle glycogen every day, there is no physiological need for you to consume high levels of carbohydrates. In fact, carbohydrates are not required in the human diet for survival the way certain fats and protein are. The body has several backup mechanisms for generating glucose internally: from dietary fat and protein, as well as from gluconeogenesis (using either ingested protein or stripping down lean muscle tissue). Researchers have estimated that the body manufactures up to 200 grams of glucose every day from the fat and protein in our diet or in our muscles. These are all adaptive survival mechanisms for a human species that was forced to survive over the course of 2.5 million years through periods of extremely low carbohydrate availability (compared to today, anyway!)—until the advent of agriculture suddenly bombarded our ancestors with massive amounts of carbs in the form of cultivated grains.

There is no biological requirement for dietary carbohydrate in the human diet. The Primal Blueprint is an “eliminate bad carbs” diet.

That said, the Primal Blueprint is not anti-carb, nor is it even rigidly low-carb, because this position might exclude certain individuals with elevated carbohydrate requirements who thrive wonderfully when they choose whole, nutrient-dense sources of carbs. Instead, the Primal Blueprint is about making informed choices based on the ancestral health model, experimenting to determine what works best for you, and being flexible instead of rigid so you can enjoy your life. So while carb intake may vary according to personal preference, it’s important to recognize a couple things:

• If you are trying to lose excess body fat, the most direct path is to moderate carb intake.

• There is no call for anyone to consume grains, sugars, sweetened beverages, or other highly processed, high-carb fare, ever.

It’s easy to stay in the Primal Blueprint Carbohydrate Curve’s optimum range of 100 to 150 grams per day—even while eating heaping servings of colorful vegetables, or the occasional fresh seasonal fruits, and other incidental sources of carbs. For example, a huge salad, two cups of Brussels sprouts, a banana, an apple, a cup of blueberries, and a cup of cherries totals only 139 grams of carbohydrates. I don’t advocate portion control or even diligently counting your macronutrient intake. You may want to journal now and then to establish benchmarks and reference points. (Visit FitDay.com or Cronometer.com and input a day or two of the food that you eat to get a breakdown of macronutrients and calories.) But you don’t really need to do this unless you’re struggling to reduce excess body fat and want to accelerate your progress.

Note: Perhaps you are familiar with the concept of “net carbs” when measuring macronutrient intake. This is a calculation that subtracts fiber from total carbohydrate intake because fiber is usually not digested, and it moderates the blood glucose impact of a carbohydrate food. Incidentally, some types of fiber can also be converted into short-chain fatty acids by bacteria in your gut, making fiber’s role more like a fat than a carbohydrate. What’s more, some experts suggest that you can omit non-starchy vegetables like leafy greens from your carb intake calculations, believing that their high fiber content and low energy yield makes them practically “carb neutral” for metabolic purposes. Personally, I don’t recommend painstakingly counting and subtracting fiber grams from your daily carb count, nor discounting the carbohydrate grams in vegetables. If you decide to journal food intake and use an online calculator like FitDay.com, you’ll see that even your gross intake of carbs will fall into a healthy zone if you are resolute in eliminating grains and sugars from your diet. If you are making strict efforts to get into ketosis, limiting your carb intake to 50 grams per day still allows for a healthy level of vegetable consumption.

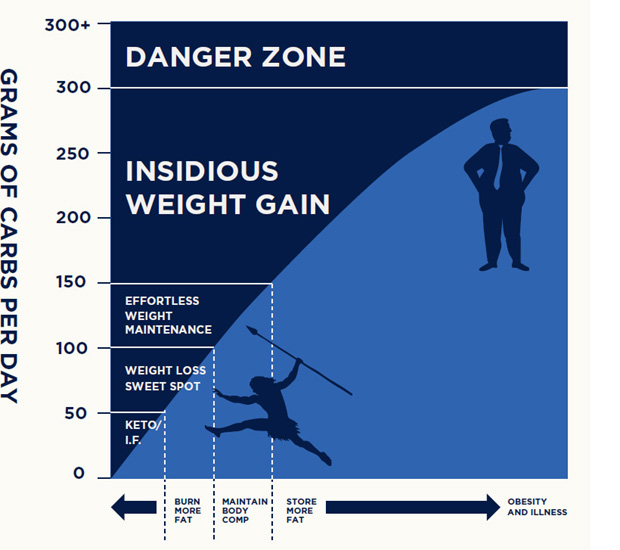

The Primal Blueprint Carbohydrate Curve provides a rough illustration of how carbohydrates impact the human body and the degree to which we need them (or don’t) in our diet. It most strongly applies to those who are “metabolically damaged” from decades of suboptimal eating and lifestyle habits (which, ahem, is most of us), since those factors collectively reduce carbohydrate tolerance. (Hence the apparent paradox of why some non-industrialized populations—who don’t spend the bulk of their adult lives stuck at desk jobs and eating vending machine food—can get away with a higher carb intake without suffering the waistline ravages we see in the West.) For those “damaged” individuals, carb reduction is an even more powerful tool in their weight-loss arsenals.

For most people, carb intake is a major factor in weight-loss success or failure, and excessive refined carb consumption is arguably the most destructive modern lifestyle behavior. Eliminating grains and sugars from your diet could be the most beneficial thing you ever do for your health!

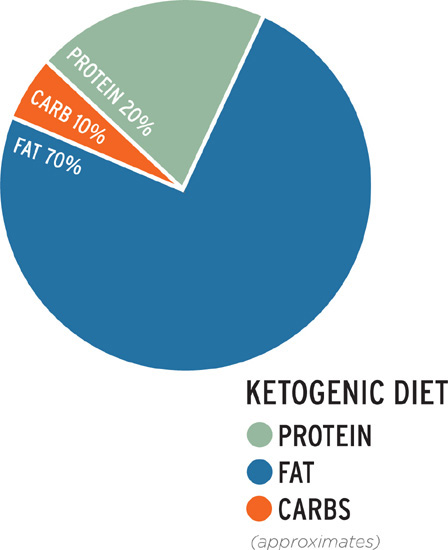

0 to 50 grams per day: Ketosis and Accelerated Fat Burning

This benchmark is an excellent catalyst for quick, relatively comfortable fat reduction, but it requires a sustained period of primal-style eating to become fat-adapted before attempting. Ketogenic eating is an advanced strategy that has become more popular in recent years, particularly among endurance athletes who want to liberate themselves from glucose dependency during exercise with disciplined dietary carb restriction. It also shows promise for treating the global obesity/type 2 diabetes epidemic and other assorted diseases, including certain brain cancers and cognitive disorders. Because ketogenic eating is such an extreme departure from the Standard American Diet, and even from typical primal-style eating, the strategy should be used with discretion by experienced primal eaters. Note that it’s acceptable to dip into and out of a ketogenic state through Intermittent Fasting.

50 to 100 grams per day: Primal Sweet Spot for Effortless Weight Loss

This minimizes insulin production and accelerates fat metabolism. By meeting average daily protein requirements, eating nutritious vegetables and fruits, and staying satisfied with delicious high-fat foods (meat, fish, fowl, eggs, nuts, seeds), you can lose one to two pounds of body fat per week in the “sweet spot.” Delicious menu options that land in the sweet spot are detailed in Chapter 9.

100 to 150 grams per day: Primal Blueprint Maintenance Range

This allows for genetically optimal fat burning, muscle development, and effortless weight maintenance. The rationale is supported by the fact that humans evolved while eating in this range or below for millions of years. This rate allows an abundant intake of nutritious vegetables, sensible amount of fresh seasonal fruits, and a moderate intake of assorted other carbs such as starchy tubers, dark chocolate, high-fat dairy, and nuts and seeds. A history of heavy carb intake may result in a brief period of discomfort during the transition to Primal Blueprint eating, but emphasizing high-satiety foods (e.g., animal products, nuts and seeds, avocado, olive, and coconut products) helps protect against feeling deprived or depleted.

150 to 300 grams per day: Steady, Insidious Weight Gain

This level of daily carb intake leads to continuous insulin-stimulating effects which prevent efficient fat metabolism and contribute to widespread health conditions—especially among those with already-reduced insulin sensitivity from modern diet and lifestyle habits. This zone is the de facto recommendation of many popular diets and “official” health authorities (including the USDA Food Pyramid!) despite the clear danger of developing or exacerbating Metabolic Syndrome. Extreme exercisers, active, growing youth, members of non-Westernized populations (whose diets and lifestyles grant a great deal of protection), and those with physically strenuous jobs may eat at this level for an extended period without gaining fat; but for many, eventual fat storage and/or metabolic problems are highly probable. This insidious zone is easy to drift into, even for health-conscious eaters, when processed grains are a dietary centerpiece, sweetened beverages or snacks leak into the picture here and there, and excessive fruits and starchy vegetables are added to the total. Recall that Kelly Korg’s trip to Jamba Juice for a “healthy” afternoon snack resulted in 187 grams of carbs ingested in one sitting. Starting your day off with a bowl of muesli cereal, a slice of whole wheat toast, and a glass of fresh orange juice might seem right off the “heart-healthy” menu at the luxury spa, but the numbers start racking up (that’s 97 grams of carbs!), and the disastrous insulin-spike/sugar-craving cycle is set in motion. Despite trying to do the right thing by cutting fat and calories, many frustrated people still gain a pound or two of fat per year for decades as a result of carb intake in the insidious range.

The image of a smoothie has become synonymous with health, vitality, and super nutrition. Yes, you are getting a good dose of antioxidants, but mainly it’s a massive insulin bomb.

300 or more grams per day: Danger Zone!

This is the typical carb intake of someone eating the Standard American Diet and is in excess of official USDA dietary guidelines (which suggest you eat 45 percent to 65 percent of calories from carbs), thanks to stuff like soda tipping the scales. Extended time in the danger zone means weight gain and the beginning (or exacerbation) of Metabolic Syndrome are highly probable. Consuming carbs in the danger-zone level (especially when they’re heavily processed and accompanied by a sedentary, insulin-sensitivity-reducing lifestyle) is the primary catalyst for the global obesity and type 2 diabetes epidemics, as well as numerous other significant health problems stemming from systemic inflammation and constant energy surplus. An immediate and dramatic reduction of sugars, sweetened beverages, grains, and other processed high-carb foods is critical.

Carb Curve Variables: The 50-gram/200-calorie variation within each range on the curve attempts to account for individual energy disparities: a light, moderately active female should aim for the low end of the range, while a heavy, active male will be comfortable at the high end. Certain extreme calorie burners who maintain ideal body composition can consume more high-nutrient-value carbs than these general ranges suggest and still enjoy good health and peak performance. However, chronic exercisers (and other high-stress folks who, thanks to “lucky” genes, are less predisposed to storing excess body fat) can still suffer from the inflammatory, health-compromising effects of danger zone carb intake, even if they don’t show it on the outside.

As Denise Cooke shows, dramatic changes in body composition can occur as a byproduct of eating primally; much more fun than the conventional approach of obsessive calorie counting and burning.

There is no single right answer to the question, “How many carbs should I eat?” It depends on many idiosyncratic variables, including your particular goals. If you’re looking to optimize your body composition and also to obtain sufficient carbs to fuel fitness endeavors, ensure healthy hormonal function (especially for women who are sensitive to carb restriction), or to feel healthy and energetic, determining your ideal carb intake starts with asking yourself a simple question: “Do I have excess body fat or not?” If you want to drop unwanted fat, the simplest and most direct path is to dial back carb intake per the Carbohydrate Curve guidelines. Some people can take a cold-turkey plunge and cut carbs in half (or further) to make fat loss happen quickly, while others might have to adopt a more gradual approach to avoid some of the stumbling blocks in the transition to fat-adaptation. Bear in mind that extracting yourself from decades of sugar dependency can initially challenge your energy, appetite, and hormonal functions—often in measure with just how severe that sugar dependency was.

First ditch sweetened drinks, sugars, and grains. Then get a good handle on your average daily carb intake with journaling and online calculators, and see how things work for you.

Your health and likely your life span will be determined by the proportion of fat versus sugar you burn over a lifetime.

—Dr. Ron Rosedale

author of The Rosedale Diet

Consuming healthy fats from animal and plant sources supports optimal function of all the systems in your body. Ingesting fat helps you feel full and satisfied in a way that ingesting carbohydrates, generally speaking, cannot. Because fat has little or no impact on blood glucose levels or insulin production, and takes far longer to leave your stomach and metabolize than carbohydrates, you will feel a deep and long-lasting satisfaction from consuming high-quality fat in your diet.

After decades of fat being maligned and misunderstood, mainstream health and medical science is finally embracing the reality that fat is not a direct catalyst for heart disease or weight gain. For instance, take the highly respected Nurses’ Health Study, which tracked the dietary habits of 90,000 nurses over two decades. It is the largest epidemiological study of women in history, leading to the publication of265 scientific papers in leading journals. The study showed no statistically significant association between total fat intake (or cholesterol intake) and heart disease. Many other studies have attempted to establish a firm connection, yet none have demonstrated that a high-fat diet by itself causes heart disease.

The Nurses’ Health Study (involving 90,000 nurses over two decades) showed no statistically significant association between total fat intake (or cholesterol intake) and heart disease.

So how can it be that low-fat eating became conventional wisdom? I believe that the otherwise well-meaning, well-educated folks in the low-fat camp are influenced by a few factors that lead them to the party-line conclusion that a high-fat diet is unhealthy.

Failure to distinguish between good fats and bad fats: The skyrocketing rates of obesity, heart disease, and cancer from eating a diet high in both processed carbs and highly refined polyunsaturated or chemically altered fats have unfairly led to all fats being villainized indiscriminately. Indeed, consuming certain dangerous fats is, from a health perspective, one of the most objectionable behaviors in modern life; but other fats are extremely healthy and nutritious. Processed junk foods are laden with partially hydrogenated trans fats, “Franken-fats” created by adding hydrogen to liquid oils to make them more solid. Solidifying fats in this manner effectively extends shelf life—a boon, for sure, for the food industry’s pocketbook. Yet from a health standpoint, trans fats can be devastating. A report in The New England Journal of Medicine reviewed numerous studies and found a strong link between consumption of trans fats and heart disease. Trans fats prevent the synthesis of prostacyclin (a cardio-protective lipid molecule that helps blood vessels dilate) and can make cells more rigid and less fluid when incorporated into cell membranes. Because your brain, nervous system, and vascular system are highly dependent upon healthy cell membranes, any dysfunction in these critical areas can be devastating. Research also shows that consumption of trans fatty acids from partially hydrogenated oils may promote inflammation, aging, and cancer.

Coconut oil: very, very good. High in health-promoting medium-chain triglyceride (MCT).

Refined high polyunsaturated vegetable oil: very, very bad. Full of free radicals!

Any consumer with a basic concern for health has undoubtedly heard about the dangers of partially hydrogenated trans fats. Less appreciated are the dangers of refined polyunsaturated vegetable and seed oils (canola, corn, soybean, safflower, sunflower, grapeseed, peanut, etc.), buttery spreads made with polyunsaturated vegetable oils, and assorted packaged or frozen processed foods manufactured with these oils. Scan labels in just about any aisle of the grocery store and you will see how these toxic agents are ubiquitous in our food supply. Because they’ve been stripped of any saving nutritional grace that could compensate for their fragile chemical structure (such as vitamin C, polyphenols, and other antioxidant phytochemicals), refined polyunsaturated fats—unlike the whole foods they were extracted from—are easily oxidized by light, heat, or oxygen. Ingestion of these free radicals in a bottle, tub, or package will disrupt healthy hormone and immune function upon consumption, and over time lead to more cellular damage throughout your body.

It’s especially risky to cook with these unstable oils, as the heat causes significant oxidative damage to the molecules. As Dr. Cate Shanahan explains, studies reveal that the ingestion of a simple order of French fries causes an immediate disruption in the normal dilation of arteries (such as that which occurs in response to exercise), and that this disruption in healthy cardiovascular function can last for up to 24 hours.

Carbs making fat look bad: Fat is calorically dense at nine calories per gram. If you consume excessive carbs (150 to 300 grams or more per day), produce a high level of insulin, and eat any appreciable amount of fat along with your high-carb diet, your fat intake will contribute directly to making you fat. Excess carbs raise insulin levels, which steers both carbs and fat (and even excess protein via gluconeogenesis, as we learned) into your fat cells, making high amounts of carbs and fat together more problematic than either macronutrient on its own.

Propaganda and flawed science manipulated into conventional wisdom: The machinations of public policy bureaucracy often leave rational thinking in the dust in favor of protecting and promoting corporate interests and the reputations of politicians. While I am all in favor of capitalism, it’s unsettling how much decision-making power is controlled by corporations that spend billions of marketing dollars molding and shaping conventional dietary wisdom in the direction of profits, with little regard for health.

In the story of how saturated fat came to be vilified, American scientist Ancel Keys is a central character. Keys was an eloquent and dynamic early promoter of the link between saturated fat intake, cholesterol levels, and heart disease. Keys achieved notoriety in the 1960s for his efforts to transition the public away from saturated fats to replacements such as polyunsaturated oils or low-fat eating in general—as well as his remarkably successful use of the American Heart Association to cement his theories into public policy. It has taken decades, at a dawdling pace, to recognize the folly of his health suggestions. For example, Keys was unable to explain the existence of healthy high-fat populations like the Inuit and Masai. While some of his earlier observational work (comparing fat intake and heart disease rates among different cultures) seemed to show a link between saturated fat and heart disease, his data were taken to show causation, a dreadful misinterpretation. (Just because two things co-occur, that does not mean one causes the other.)

The Framingham Study, Nurses’ Health Study, and recent meta-analyses (reviews that aggregate data from numerous related research studies) have strongly refuted the oversimplified direct association between fat and disease that unfortunately became entrenched in conventional wisdom. (In fairness, Keys also did some great work helping to popularize the Mediterranean diet—highlighted by the liberal intake of healthy fats—even spending his last few decades living in a small town in Italy and studying the residents’ dietary habits.)

On a bureaucratic level, the U.S. government has time and again shown a penchant for doggedly defending the status quo, while vigorously squashing voices opposing conventional wisdom. A prime example of the influence of power and money on the development of public policy is found in the FDA’s so-called “imitation policy,” passed in 1973 (without congressional approval, thanks to some clever legal maneuvering). The legislation relieved food manufacturers from having to use that pesky “imitation” designation on labels of foods created with artificial ingredients (coffee creamers, egg substitutes, processed cheeses, whipped cream, and hundreds more), as long as manufacturers added synthetic vitamins to their concoctions to approximate the benefits of similar whole foods.

Mary Enig, Ph.D., a renowned nutritionist, lipid biochemistry expert, and author of Know Your Fats, from the University of Maryland, spent her career battling conventional wisdom’s take on fat intake and heart disease. In the 1970s she was a central figure in challenging the corruption and misinformation dispensed by the USDA and the U.S. Senate’s McGovern Committee (headed by former presidential candidate George McGovern). Influenced by highly questionable and lobby-influenced testimony, the committee published its report directing Americans to replace saturated fat with polyunsaturated fatty acids and to limit fat intake in general, which was then disastrously replaced with excessive processed carbohydrates.

On the heels of these cultural turning points, government-funded research over the following decades tended to fall in line with the committee recommendations. The notion that all fats are bad gained momentum and was adopted as conventional wisdom. Today leading health authorities are now presenting a more responsible big-picture perspective about the role of fats in a healthy diet and the dangers of eating chemically altered fats in particular. But it will take the general public—and especially low-fat enthusiasts—many more years to embrace and implement what is now validated by scientific research.

While most cells in our body can easily burn both fats and glucose, there are a few select cells that function only on glucose (some brain cells, red blood cells, and kidney cells, for example). Without glucose, those cells would cease to function, and we would not last very long. The minimum daily glucose requirement to keep those systems running has been estimated at between 150 and 200 grams per day, but recent research shows that after a little adaptation, some of these cells can operate effectively on a fuel your body manufactures itself known as ketones, dramatically reducing your overall glucose requirement.

Bust out some ketones by restricting carb intake once you are fat-adapted.

Ketones are produced in the liver as a byproduct of fat metabolism when blood glucose and insulin levels are very low. Brain cells and cardiac and skeletal muscles utilize ketones in the same manner they use glucose, making ketones a highly effective, clean-burning substitute for the energy provided by ingested carbohydrates. As you might imagine, ketones were crucial to human evolution, since our ancestors rarely had steady access to carbohydrates like we do today. In fact, they may have gone weeks or months without appreciable carbs, so they had to evolve systems to manufacture glucose (gluconeogenesis) or glucose substitutes like ketones.

Your body evolved to utilize ketones in the same manner as glucose; a key survival component throughout human evolution.

Ketone burning helped keep Grok alive during short periods of starvation or longer periods when meat (protein and fats) was plentiful but plants (carbs) were not. Ketones are safe, desirable, energy-efficient forms of fuel. They are quite literally the fourth macronutrient fuel source, but they come from inside your body instead of from your plate. After just a few weeks of reducing carb intake, and therefore insulin production, and increasing the relative amounts of healthy fats in your diet, you will send signals to your genes that result in an increased production (an “upregulation”) of the metabolic “machinery” used to effectively burn both fats and ketones throughout your body. When your body becomes efficient at using fat and ketones for energy, you are said to be fat- and keto-adapted.

Ketones are an internally manufactured energy source that the body burns in the same manner as glucose—except more cleanly!

Why Glucose Is Dirty and Ketones Are Clean

The benefits of being keto- and fat-adapted extend far beyond weight loss. Quite frankly, glucose burns “dirty” in your body, creating considerable metabolic waste products, inflammation, and oxidative damage; while fat and ketones burn “clean.” Glucose is metabolized for energy quickly and easily, but mitochondria and oxygen are not required for glucose burning. Hence, you can lose out on the free-radical protection that mitochondria provide during calorie burning. When you are locked in a carbohydrate-dependency diet, your mitochondria can actually atrophy. This atrophy increases your susceptibility to all forms of oxidative stress, not just from diet but from chronic exercise, pollution, and the stress of hectic modern life. Note: glucose can also be burned with oxygen and mitochondria, but even then more free radicals are generated in comparison to burning fat and ketones.

The best way to optimize mitochondrial function and protect yourself against general free radical damage is to become fat- and keto-adapted. Utilizing lots of oxygen and mitochondria to metabolize calories, requiring fewer calories to survive (because insulin and hunger hormones are moderated when you are fat-adapted), engaging in Intermittent Fasting, and dipping into that rarified state of ketone burning—even if it’s just occasionally—all support mitochondrial biogenesis. Mitochondrial biogenesis is the manufacture of additional mitochondria (and optimizing the functioning of existing mitochondria) to better diffuse the oxidative stress of burning calories and simply being a living, breathing human.

Ketone burning has been shown by science to facilitate rapid fat reduction, improve the function and development of mitochondria (the energy centers of our cells), exert a potent anti-inflammatory effect, improve immune function, boost cellular repair, control epilepsy, deliver assorted benefits to cognitive function (especially for those with dementia, autism, and ADHD), and even fight cancer (by starving cancer cells of their main fuel, glucose.) Check out The Art and Science of Low Carbohydrate Living by Dr. Steven Phinney and Dr. Jeff Volek for a comprehensive education with scientific detail about the wonders of ketones for the aforementioned conditions, and watch Dr. Dom D’Agostino’s TEDx Talk “Starving Cancer” for details on that subject. Interestingly, the therapeutic benefits of ketone burning have prompted the manufacture of consumable sources of ketones, allowing one to override the delicate macronutrient restrictions and achieve elevated blood ketone levels.

After reaching sufficient fat-adaptation through a sustained period of primal-style eating, people who take the next step and commit to a ketogenic eating pattern (requiring even further carb restriction) report accelerated fat reduction, improved mental clarity, and better endurance performance. (See Chapter 7 in Primal Endurance for some amazing accounts of elite athletes performing world-class endurance feats fueled by fat and ketones.) Interestingly, many cells actually prefer to burn ketones over glucose, given the choice between the two. Cardiac muscle, skeletal muscle, and even certain brain cells thrive on the four-and-a-half calories per gram delivered by ketones. After a little keto-adaptation, the brain can do very well getting 75 percent of its energy from ketones.

Ketones can’t be stored conveniently the way fats (and excess glucose) can be stored in fat cells or the way glucose can be stored as glycogen. Ketones simply circulate in the bloodstream where they are available to be picked up by any cells that want and need the energy they provide. Ketosis is the scientific name for a relative condition in the body where ketones start to accumulate in the bloodstream to a point beyond which they can be utilized for energy. Despite the flawed assertions from some mainstream dietary authorities, there is nothing dangerous or undesirable about being in ketosis, per se. It is a natural, normal part of human energy production and metabolism. In fact, most everyone wakes up in a state of mild ketosis from fasting overnight (unless you are a midnight snacker!), or any other time you don’t ingest carbs for a prolonged period of time.

That said, ketosis is a very delicate metabolic state. Once you consume even a moderate amount of carbs (or enough protein to get converted into carbs), you’ll be spit right out of ketosis and back into a glucose-burning state. It’s most likely a state early humans encountered frequently, but not permanently. And while existing studies on ketosis have been promising, very long-term sustained ketosis—say, years and beyond—remains something of an experiment, with potential negative repercussions for gut health and hormone function if occasional carb refeeds don’t occur. (Contrary to popular belief, there aren’t any known examples of human populations who live entirely in ketosis. Even the traditional Inuit diet isn’t ketogenic because of it’s too-high-for-ketosis protein intake; plus, a widespread genetic mutation causes Inuit to burn long-chain fatty acids for heat instead of producing ketones.) Bottom line: intermittent macronutrient changes are more in line with our evolutionary past than any permanent dietary state, and most people—excepting those with specific athletic goals or health conditions that benefit from ketosis—should think of ketosis as a cyclical tool, rather than a state to strive for indefinitely.

If you are not presently keto-adapted—and most people who eat a moderate-to-high-carb diet are not—and then you abruptly decide to fast in the name of cleansing or weight loss, the ketones you manufacture in the absence of dietary carb intake aren’t yet able to be burned efficiently. Instead, you excrete the ketones you make via breathing and elimination. Some describe the smell of ketone breath as that of overly ripe apples or nail polish remover. If you are new to primal eating, you will require a few weeks to reprogram your genes to become more efficient at burning ketones. As your body adapts to a genetically optimal low-carbohydrate eating pattern, you will burn ketones effectively and excrete fewer, thereby further reducing your glucose requirements.

Some people—including some misinformed doctors and dietitians—maintain a distorted, negative view of ketones and ketosis. I believe these criticisms arise because the diets in question allow for only 20 grams or less of carbs per day, a level that does not allow for the plentiful intake of nutrient-rich vegetables. While we are not meant to run predominantly on carbohydrate energy, we do depend heavily on the nutrients offered by vegetables and most fruits. Other people may be mistaking ketosis for ketoacidosis, a potentially deadly condition that affects insulin-dependent diabetics and alcoholics and which is completely different from nutritional ketosis.

Under normal Primal Blueprint maintenance eating patterns, you rarely enter a state of ketosis because of the dietary emphasis on high-nutrient-value carbs like vegetables. The Carbohydrate Curve maintenance zone of 100 to 150 grams of carbohydrates daily is still quite low by comparison to the Standard American Diet, but it’s too high to launch you into serious ketone burning. This is just fine, of course, but learning about ketosis and trying it now and then to accelerate weight loss (and enjoy other metabolic benefits) or to experiment with endurance performance gains is something to consider, especially as you get further into primal living and become highly fat-adapted.

On the Primal Blueprint accelerated fat-loss program (detailed in Chapter 9), you will eat in what I call the sweet spot—a level of mild ketosis—by consuming 50 to 100 grams of carbs per day. Here, your carbs are low enough to enable quick fat reduction, your protein is optimized to preserve lean muscle mass, and you have plenty of fat to keep you completely satisfied at meals and throughout the day.

Understanding how you metabolize protein, fat, carbohydrates, and ketones, and controlling the rates at which each one burns by improving your diet and exercise habits, you needn’t agonize over day-to-day calorie counting. As long as you are eating primal-aligned foods, you will be able to naturally maintain your ideal body composition and mitigate your risk of diet-related health conditions and diseases.

My doctor told me to stop having intimate dinners for four. Unless there are three other people.

—Orson Welles

1. The dated “calories in, calories out” equation for weight management fails to recognize context, particularly the hormonal disregulation caused by wildly excessive insulin production. If you are locked into a fat-storage pattern due to high-carb eating patterns, this will override attempts to lose weight through caloric deficits.

2. Daily macronutrient need calculations start with protein, since protein is essential for building and repairing healthy tissues and organs. The new Primal Blueprint recommendation for average daily intake is 0.5 grams per pound (1.1 grams per kilo) of lean body mass. Consuming higher amounts of protein simply results in the excess being converted into glucose via gluconeogenesis. Hence a “high-protein” diet effectively becomes a high-carbohydrate diet. Furthermore, a pattern of excess protein consumption stimulates growth factors and accelerates cell division, leading to increased cancer risk and reduced life span.

3. Wildly excessive carbohydrate intake is the foremost health-undermining behavior of the Standard American Diet. Carbohydrate intake prompts insulin production, which prompts fat storage. Dial back carbs and you will drop excess body fat. The primal approach recommends ditching grains, sugars, and sweetened beverages and obtaining whatever level of carbs are desired from high-nutrient-value sources like vegetables, fruits, sweet potatoes, and wild rice. The various intake ranges on the Primal Blueprint Carbohydrate Curve reflect how one can achieve weight-loss goals, optimize general health, and minimize disease risk. Primal Blueprint-style eating affords abundant intake of vegetables, sensible intake of fruits, and high-nutrient-value carbs as desired by fitness/activity goals and personal preference—usually landing in the neighborhood of 150 grams per day.

4. When protein intake is optimized according to lean mass, and carb intake is moderated per primal guidelines, fat becomes the primary source of caloric energy and dietary satisfaction. Fat has been maligned by conventional wisdom for a few reasons: failure to distinguish between good and bad fats, high carb intake making fat problematic, and propaganda and flawed science. Saturated fat is healthy and optimal to cook with. Monounsaturated fats and omega-3 fats offer excellent health benefits. Refined high polyunsaturated vegetable oils and chemically altered vegetable oils inflict oxidative damage on the body and should be eliminated.

5. Ketones are an internally manufactured energy source, a byproduct of fat metabolism in the liver when blood glucose levels are low due to disciplined restriction of dietary carbs. The brain, heart, and skeletal muscles use ketones in a similar manner to glucose, but it burns with much less oxidative stress than glucose and actually delivers a potent anti-inflammatory effect. Ketones were a critical component of evolution, enabling humans to survive during periods of insufficient dietary calories. Today, breaking science shows ketones to have incredible promise for fat loss, improving cognitive conditions and seizures, boosting endurance performance, and fighting cancer. Becoming keto- and fat-adapted means that you are efficient at burning internal sources of energy and no longer dependent upon regular meals to sustain energy or concentration.