7 Schubert’s social music: the “forgotten genres”

The conviviality of Schubert’s milieu thoroughly colors our image of him. It seems fitting that his contemporaries should have known him best not only for his Lieder but also for his work in other genres conducive to friendly music-making by amateurs. This social music included part-songs and dances for solo piano, as well as pieces for two pianists at one instrument – a medium, Alfred Einstein noted, that is “symbolic of friendship.” 1 Because they suited the tastes of the rising middle classes and the configuration of the Viennese music world, many such compositions by Schubert were published and performed during his lifetime, yet they are often overlooked today. Even in his Vienna, sociability would not usually have been considered an elevated attribute, and each genre had further limitations. Despite the popularity of the social music, it could never have ranked high in the system of genres. 2

Einstein, for one, was bothered by the “sociable” Schubert, in particular the composer of the four-hand music, whom he set in opposition to the “deeply serious Schubert,” the “real and great Schubert” of the later string quartets and piano sonatas. 3 The implicit standard to which he held Schubert was, of course, Beethoven, the master of the string quartet and piano sonata who expended little effort on his work in the lesser genres. 4 Although their careers overlapped, the two men had come of age as composers in different circumstances: Schubert did not compose for the aristocracy as Beethoven had. If he sometimes wrote with publishers (as opposed to patrons) in mind, Schubert for the most part did not regard his social pieces as mere potboilers. He had, in the words of Alice Hanson, “amateur yet discerning audiences”; 5 he made his way in the world with this music, and it was in his interest to compose it well. As Einstein surely recognized, Schubert could be “sociable” and “deeply serious” at the same time.

This particular mixing of categories may also reflect the character of musical life in Vienna at a time when distinctions between private and public, amateur and professional, social event and concert did not always hold. Because no concert hall yet existed, 6 there were few fully public performances; the city’s musical life revolved instead around private and semi-public events. At some soirées, accomplished Viennese musicians who did not necessarily make their living as performers played and sang with professionals. The stated purposes of the “Evening Entertainments” (Abendunterhaltungen ), the semi-public concerts of the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde, included “musical activity and pleasure,” but also “the promotion of conviviality among the music lovers of our city of residence.” 7

While this environment for a time gave importance to music that facilitated social intercourse, these genres eventually merged with others or faded into obscurity. Schubert did not manage to change their standing. Still, he composed some of his most vivid, inspired music in these “forgotten genres.” What possibilities did he find in them, and how did he work around the aesthetic tone and other compositional features that defined and limited them? How compromised was each kind of music by its social function? In what ways do these compositions relate to his works in the higher genres? Since the answers differ for his dances, piano duets, and partsongs, each requires a separate story.

Schubert’s dances for piano solo

The passion for dancing in Biedermeier Vienna made publishers especially receptive to Schubert’s dances for solo piano. His first instrumental compositions to appear in print were the Originaltänze (D365), published as Op. 9 in 1821. Seven more collections came out between 1823 and his death in 1828; additional dances appeared in anthologies. 8 Publishers rushed all of this music into the market for Fasching, the climax of the dancing season in Catholic Vienna.

Schubert composed examples of most of the dances popular at the time. In his early years, he wrote a number of minuets and, in the 1820s, one cotillion and two galops. Throughout his life, he cultivated the écossaise, a duple country-dance imported from Great Britain. His triple-meter waltzes, Ländler, and German dances, however, sound most characteristically Schubertian and inspired a host of later composers; I will therefore focus on them here. Schubert himself almost invariably referred to these as “Ländler” or “Deutsche Tänze” – only on one extant manuscript, apparently, does he call a dance a “Walzer” – but his publishers most often preferred to issue them as waltzes. 9

Schubert’s dances, which number approximately five hundred, would seem to epitomize the ephemerality of most social music. According to the reports of his friends, he improvised these minuscule pieces for their dancing and listening pleasure in the evening, and on the following morning sometimes wrote down those that he liked (SMF 121). Since they appear to have a place somewhere between compositions and recorded improvisations, how seriously should we take them? 10 He composed functional rather than stylized dances, so he worked under clear technical constraints, four- or eight-measure phrases and small forms with two sections, each to be repeated. While Maurice J. E. Brown deemed “Schubert’s elevation of the short dance … comparable to his elevation of the Lied,” 11 he believed these restrictions made the first genre intrinsically insignificant, whether improvised or not. Brown nevertheless stressed the fascination of Schubert’s dances as “notes” in a kind of musical “journal” – this would apply especially, of course, to the dances as they appear in the manuscripts – and he traced the transformation of one Ländler into a section of the Scherzo in the D Minor String Quartet, “Death and the Maiden” (D810). 12

Brown also raised the possibility, although he gave no examples, that these improvised “jottings” might give us a glimpse of Schubert trying out particular compositional and instrumental techniques. A group of Ländler within the Walzer, Ländler, und Ecossaisen, Op. 18 (D145, numbers 4, 6, 7, 8, 9, and 12), all in D flat major and taken from one autograph, seem to do just that. (Brown compiled a catalogue of Schubert’s dance manuscripts, in which this one, containing altogether eight Ländler, is number 38. 13 ) In this set the composer embroidered plain harmonies arranged in repetitive patterns, using a variety of pianistic effects: striking articulations and shifting between registers, along with trills and other kinds of figuration. If a continuum between improvisation and work is hypothesized, these dances probably lie close to the first category.

A group from the next manuscript (Brown’s MS 39) show a different kind of preoccupation. Schubert entered these five dances as F sharp major “Deutsche Tänze” in his autograph, but they came out as F major waltzes in the Originaltänze (numbers 32–36). The dances, which bear the date March 8, 1821, 14 play with the possibilities of modal mixture, in other words, of borrowing (flatted) notes and chords from the parallel minor key. In each the chromatic inflections underpin his interpretation of the genre’s even phrases and divided form.

The division in the middle of the dances works as a signal for change. 15 In numbers 32 and 34, for example, the section before the double bar is tonally closed; the flatted notes do not enter until after that cadence. Schubert built the two openings in otherwise contrasting ways, and this influenced what happens thereafter. Like many additional dances by him, number 32 does not begin on the tonic. This gives an extra lilt to the initial eight measures, a period or pair of balanced four-measure phrases. A more subdued period, self-enclosed in D flat major after the double bar, acts as a foil (see Ex. 7.1 ).

Schubert constructed the opening eight measures of number 34 in the less balanced form of a sentence: the second four-measure phrase seems to move more rapidly than the first. 16 A dissonant (German-sixth) harmony helps maintain the quicker pace after the double bar, in a prolongation of the dominant (D$$ – C – B – C in the bass) that lasts until the final measure. All five dances let us see the composer linking modal mixture with nuances in his handling of the form – do they document his first inspirations?

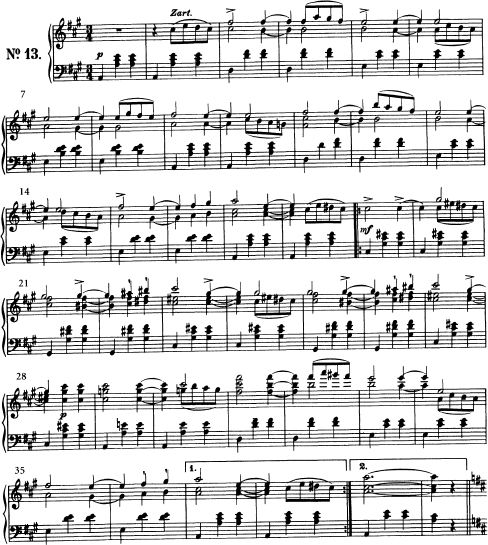

Certain other dances unequivocally are works rather than improvisations. The thirteenth of the Valses sentimentales, Op. 50 (D779), stands out for the originality of its form, the continuous two-part writing in the right hand, and even the marking “zart” (“tenderly”) – exceptional in this repertory by Schubert. Although the beauty of most of these dances lies in fleeting subtleties that resist analysis, the intricacy of this one invites it (see Ex. 7.2 ).

This waltz opens, as did the previously discussed dance, with a two-measure introduction: the piece in effect begins in measure 3, on the supertonic. Series of suspensions draw the first phrase out into an indissoluble eight-measure span. A new motif (mm. 16–17) in the second phrase must break the whirling pattern to bring the section to a close. When this cadential motif reappears twice after the double bar in a bright C sharp major (mm. 22–23, 26–27), its new placement in each four-measure phrase entails yet another such phrase, in which the motif completes itself and the C sharp major triad resolves by chromatic magic to an A7 (m. 29), thus preparing the off-tonic reentry of the original melody and, with the syncopated phrase rhythm, creating an elegant dovetailing in the form.

This waltz holds its own as an “autonomous” aesthetic object. But does it make more sense in general to consider the possibility of dance collections as works? In a few manuscripts, certainly, a closed key-scheme or a coda indicates that Schubert conceived a group as a cycle, just as these same features serve to unify some of the published sets. 17 The twelve Valses nobles, Op. 77 (D969), for example, are organized around C major in this pattern: C-A-C-G-C-C-E-A-A minor-F-C-C. The character of these waltzes may also mark them as a cycle, for they are the most extroverted collection, as well as pianistically the most difficult because of the many passages in octaves.

In a recent article, David Brodbeck has pointed out that at least one group of dances was unlikely to have had its origins in improvisation at a party: Schubert wrote them while receiving treatment for syphilis, possibly while in the hospital. 18 With Einstein and Brown, 19 Brodbeck notes the unvarying high quality of the Ländler in this manuscript (Brown’s MS 47), none of which appeared in print during Schubert’s lifetime. These dances were finally published in 1864 in an anonymous edition (Op. Post. 171, D790) by Johannes Brahms, who had become an ardent collector of Schubert autographs during his first years in Vienna. No doubt because he recognized the fineness of all twelve Ländler, Brahms chose to maintain the integrity of Schubert’s manuscript. Yet the set begins and ends in different keys, and there are no other overall unifying features. Five years later Brahms selected Ländler from several sources, much as publishers during Schubert’s lifetime had done, to make a companion volume of twenty dances. 20 He carefully ordered the chosen Ländler, but he did not try to make a cycle.

Example 7.1 Originaltänze, Op. 9 Nos. 32 and 34 (D365)

Example 7.2 Valses sentimentales, Op. 50 No. 13 (D779)

For the most part Schubert’s sets do seem to be loosely strung gems. When other composers fell under their spell, though, they responded by creating more tightly organized collections, in this way solving the problem of the brief forms. In a rapturous review, Robert Schumann made the Deutsche Tänze from Schubert’s Op. 33 (D783) whole in his own imagination by transforming them into a ballroom scene. 21 He went on to write dramatized sets of his own, including Papillons (Op. 2, 1829–31) and Carnaval (Op. 9, composed in 1833–35). While Carnaval contains a Valse noble that at least initially follows the style of Schubert’s collection, the earlier Papillons seem more continuously indebted to him. To unify this piece, Schumann opened and closed in D major, bringing back the first waltz during the finale in a programmatic fade-out. Maurice Ravel’s homage to Schubert, the Valses nobles et sentimentales (composed in 1911), likewise centers around his own version of G major; during the last dance, fragments from all but one of the seven earlier waltzes reappear. In the Soirées de Vienne (published in 1851), Franz Liszt used actual dances by Schubert as the basis for nine concert pieces, providing introductions, elaborations, transitions, and codas around and between unadorned appearances of the original dances.

Already in 1821, Carl Maria von Weber had published a glittering concert piece with a programmatic introduction, the famous Aufforderung zum Tanz. There is no evidence that Schubert aspired to compose a similar kind of work or even to have his dances performed outside the home. His constant cultivation of the genre did, however, leave its traces in his larger compositions: in his waltz- or Ländler-like “minuets” and “scherzos” – especially in their trios – and in the rhythmic character of passages like the second theme of the “Unfinished” Symphony (D759).

Compositions for piano, four hands

Domestic performances have always provided the only natural venue for piano duets. Because private music-making was centrally important and, too, because an increasing number of middle-class families could afford to buy pianos, the market for four-hand music flourished in Vienna in the 1820s. 22 Many of Schubert’s piano duets date from his Hungarian sojourns in 1818 and 1824 as the musician-in-residence of the Esterházy family in Zseliz; he may well have written others specifically for publication. During his lifetime, a higher proportion of his compositions in this genre than in any other appeared in print, and with good reason: he was the greatest of all composers of four-hand music.

If the unstylized condition and brevity of the form limited Schubert’s dances for piano solo, the unfortunate, homebound medium itself kept his four-hand music from rising in the hierarchy of genres. But do piano duets constitute a genre after all? Carl Dahlhaus observed that most musical genres are defined by a number of separate attributes: thus, the string quartet of the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries is distinguished by its formal layout and sophisticated tone as well as by the group of players that give it its name; while a fugue, characterized only by a compositional procedure, is “underdetermined” as a genre. 23 Is four-hand music more than a medium? Can we speak of Schubert’s piano duets as a genre within at least his own output?

If we exclude three of his piano duets from consideration, patterns of manner and affect, if not of form, do seem to mark Schubert’s four-hand music as a genre. The works that do not fit are the sonatas composed in the summers at Zseliz, the B flat Sonata (D617) from 1818 and the “Grand Duo” (D812) from 1824, along with the Fugue in E Minor (D952) from 1828. In its form, naturally, but also its almost consistently elevated style, the “Grand Duo” in particular resembles the later solo sonatas rather than the other duets: it would have fallen into Einstein’s category of the “deeply serious Schubert,” if he had allowed any four-hand piece to do so. The fugue, which reflects an intensified interest in counterpoint in the final months of his life, stands outside the mainstream of his work altogether.

Einstein shrewdly observed that the “Grand Duo” could not be an arrangement of a symphony, as Robert Schumann and Joseph Joachim (among others) had suspected, because “Schubert, as a symphonist, would have limited himself to a quite different range of modulations.” 24 He was similarly aware of an essential stylistic difference between the piano sonatas and most of the four-hand music, but the pejorative cast of his comments marred his insight. Despite his enthusiasm for many of the piano duets, he valorized the later piano sonatas and string quartets at their expense, focusing his criticism of the composer’s “sociable” side on an easygoing manner and, especially, a tendency toward facile brilliance.

No piano duet by Schubert is more “easygoing” yet eloquent than the A Major Rondo (D951) from 1828, “the apotheosis of all Schubert’s compositions for four hands.” 25 After a thirty-two-measure refrain, the first episode moves to the key of the dominant with a melodious absence of drama, arriving at the official second theme – this is a sonata-rondo – only in measure 69. Schubert’s leisurely approach works because he handles the internal rhythms of individual phrases and larger sections with consummate skill. This understated mastery and the tasteful ornamentation throughout the composition make it sound unfailingly gracious; only at the end of the recapitulation, in the passage beginning with a deceptive cadence to $$VI in measure 241, does suppressed yearning break through the good manners (the outburst in the central episode is more predictable).

Characterizing the four-hand style as “sociable” seems appropriate, but that quality should not be underrated. The function of this music was, indeed, to promote pleasant social relations. To fulfill this role, Schubert accommodated a variety of musical tastes. For example, while he rarely used imitative counterpoint in the solo sonatas, he lavished it on the piano duets. The four-hand works also emphasize less complicated attractions: instrumental brilliance, as well as picturesque rhythms and sonorities presented for their own sake. An impulse to provide entertainment becomes evident in the kinds of compositions represented. With the B flat Sonata, the seventeen duets published through 1828 included six individual marches or collections of them, four sets of themes and variations, two groups of polonaises, two rondos, a single overture and divertissement. 26 When one publisher solicited a piano duet, he specified “a fairly brilliant work of not too large dimensions, such as a grand polonaise or rondo with an introduction, &., or a fantasy” (SDB 439).

The Divertissement à l’hongroise (D818), as befits its name, may offer the most extreme example of the “divertimento aesthetic” in Schubert’s piano duets. In this work, he surrendered to the considerable delights of an exotic primitivism. By itself, the first of the three movements features virtually the entire array of effects that make up the style hongrois: short phrases, dotted rhythms, drone fifths (mm. 71–72), melodic augmented seconds (mm. 81 and 136–37), imitation of the cimbalon (e.g., in mm. 15 and 20), heavy encrustation with grace notes and other embellishments. 27 This movement, moreover, forgoes almost any semblance of development or, at times, even large-scale harmonic direction. The lengthy section between measures 93 and 123, for instance, comprises a number of short repeating strains that veer between B flat major and D minor, in a manner that seems more wayward than intentionally ambiguous, before finally heading back toward the tonic, G minor, after measure 124. (On another level, of course, Schubert deliberately chose to compose primitivistically.) Although the remaining two movements maintain the colorful style, they adhere more closely to formal and harmonic norms of Western Classical music from this period. The second movement, with its spondaic rhythms and air of relentless melancholy, anticipates the opening of the Andante in the “Great” C Major Symphony (D944), but Schubert designed it as a conventional march – albeit a Hungarian one in C minor – with trio (in A flat major). And while the rondo-finale displays the folklòric traits of the opening movement, Schubert organized it around a harmonically focused refrain in rounded binary form.

Schubert’s piano duets inhabit the same expressive universe as his chamber music with piano. 28 The two genres, furthermore, have a technical feature in common. A pianistic texture in the “Trout” Quintet (D667) and both piano trios derives from the four-hand practice of doubling a melody at the octave in the two hands of the primo player. 29 (See, for instance, mm. 26 ff. in the first movement of the B flat Trio, Op. 99 (D898); mm. 23–41 in the Andante con moto of the E flat Trio, Op. 100 (D929); and the first variation of the “Trout” Quintet.) Unlike most chamber music, though, Schubert’s piano duets often do not bother to pretend that the players are equal individuals.

What, then, does the symbiotic relationship between the duo-pianists have to offer? Because the form of theme and variations emphasizes differences in texture, Schubert’s four-hand sets demonstrate the compositional possibilities most clearly. Each of the summers in Zseliz produced not only a sonata, but also a set of variations for piano duet. The Variationen über ein französischen Lied from the summer of 1818, Op. 10 (D624), were Schubert’s first published four-hand work (which he dedicated to Beethoven). As in the chamber movements based on Die Forelle (D667/iv), the operatic duet “Gelagert unter’m hellen Dach der Bäume” (D803/iv), and Der Tod und das Mädchen (D810/ii), most of these variations retain the melody of the theme, usually doubled in the two hands of the primo player, although sometimes divided between the two pianists (for example, in the sixth variation). An even finer piece, the Andantino varié published in 1827, Op. 84 No. 1 (D823), includes more learned and more ethereal four-hand textures. In the third variation, the primo left hand has the melody, as the two right hands engage in imitation at the distance of a half-measure. And in the fourth variation, the primo right hand plays high, delicate figuration, while the secondo right hand and primo left hand share the melody; in the first half of measures 99 and 100, it is clear only to the players which one has it. Schubert’s late variations on a theme from Hérolt’s Marie (D908, published as Op. 82 in 1827), in contrast, show the noisy excitement possible in four ostinato patterns layered on a piano. This set enjoyed considerable success, prompting one publishing firm to ask him twice for similar duets “which, without sacrificing any of your individuality, are yet not difficult to grasp” (SDB 735; also, 814).

Schubert’s greatest set of variations may be the four-hand Variations sur un thème original in A flat (D813), composed during his second summer in Zseliz and subsequently performed to appreciative audiences on several occasions (SDB 363,370,401). This work, too, is distinguished by felicitous imitative counterpoint, with the lines divided variously between the two players, as in the second variation, or the two hands of the primo pianist, as in the third. The seventh variation stands out as most remarkable for its deliberately ambiguous chromaticism: it hovers between F minor and C minor before finally moving to the dominant of A flat in preparation for the last variation. Diversion of any ordinary sort is hardly the point here, but the set does conclude on a much lighter note; when Schubert aimed at a loftier style in his four-hand music, it rarely remained unmixed with simpler pleasures.

Schubert juxtaposed the elevated and the entertaining most starkly in the Allegro in A Minor (D947) from 1828, which came out posthumously under the spurious title “Storms of Life” (“Lebensstürme”). This sonata-form movement opens in a forceful Beethovenian vein with the quasi-orchestral massiveness possible in the four-hand medium. The thematic restatement that begins in measure 37 would typically merge with a form-defining modulation. Schubert makes this second statement harmonically richer than the original, yet it leads only to an arpeggiation, in low octaves, of the dominant-seventh chord (mm. 81–88). At this point, he creates one of his most miraculous moments: from the dominant seventh he takes the leading-tone, the tensest note in tonal music, with no mediation as a secondary tonic (m. 89). A new theme is presented in A flat major, after which the piece shifts by another common-tone modulation to the orthodox key of the relative major (C). The unstable, visionary effect is maintained through a diaphanous texture characteristic of the medium: the primo right hand plays high figuration against a repetition of the new theme in the middle register and low octaves in the secondo left hand. After the heroic beginning and otherworldly second group, the exposition changes stylistic gears, becoming in a lengthy closing section conventionally – sociably – brilliant.

The partsongs

Like the other genres considered in this chapter, Schubert’s partsongs had their roots in gregarious music-making. The Austrian traditions that he received remain murky, but most scholars agree on a few points. Although his partsongs became staples of the choral repertory later in the century, he wrote them in what appears to have been the Austrian custom of one singer to a part. 30 While he composed for both mixed (SATB) and unmixed male and female voices, male songs predominated in his work, as in that of his predecessors: all but one of the nineteen partsongs published before his death were for male voices only. 31 Whatever the particular medium, the partsong as he inherited it seems to have provided less an aesthetic than a convivial experience. An anecdote by Anselm Hüttenbrenner suggests the casualness, in particular, of many of the male songs – the Biedermeier equivalent of the barbershop quartet. Hüttenbrenner related that Schubert and he would get together with two other students every Thursday to sight – read new vocal quartets by each of them, and he recalled that once, having forgotten to write a quartet beforehand, Schubert composed one on the spot (SMF 179). He later (1818) wrote a piece for mixed voices actually entitled Die Geselligkeit (D609) – “conviviality” – and he produced Trinklieder throughout his life.

Unlike his four-hand music, Schubert’s partsongs proved able to bridge the gap, admittedly sometimes blurred, between domestic and concert performance. In the Abendunterhaltungen presented by the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde in the 1820s, a vocal quartet by Schubert often ended an entertainment that had opened with a string quartet. 32 These partsongs also appeared on programs in public spaces like the Kärntnerthor Theater. Even before they were performed publicly, he had begun to try out new compositional possibilities that pushed at the limits of the genre, writing exquisite but small-scale works, presumably for the pleasure of just a few close friends and himself. Later, however, he redefined the partsong to make it more fully worthy of performance in the largest halls. The upward mobility of the genre had a predictable effect on him: he became ambitious for it.

In contrast to both the dances and the four-hand music, it is possible to chart a clear development in the partsongs. I will therefore discuss Schubert’s work in this genre chronologically, beginning with his student years. As part of his lessons with Antonio Salieri, he most likely set German as well as Italian texts in three- and four-voice textures of various kinds. 33 After completing his studies, he initially preferred the chordal textures and strophic settings of the popular idiom. He appears to have first experimented with innovative approaches in two partsongs from 1817. In Lied im Freien (TTBB, Salis-Seewis, D572) he set the stanzas in contrasting textures and keys, using vaguely illustrative figuration. In the fourth stanza (“There dip and rise”), for example, repetitive oscillating figures within a meandering movement from B flat minor to B major evoke simultaneously gleams of light on a brook and the flickering consciousness of the observer. Madrigalesque tendencies stand out even more in his first partsong setting of Goethe’s Gesang der Geister über den Wassern (TTBBB, D538). 34 Schubert broke this sublime poem into small grammatical units; inevitably, the meaning of the whole got lost in the proliferation of cadences and musical images. In later partsongs, he was to create more economical sign-systems in the service of high-minded themes: for example, the merging of subject and object (Nature with a capital N), barely suggested in these works. And in a number of these later compositions, the return of the opening, a feature of both settings from 1817, would become an event of great significance; he began to compose three-part forms in which what happens in the middle transforms the reappearance of the first section, itself now made longer and weightier.

These trends came into focus in two works from April 1819. Schubert’s setting of Goethe’s Nur wer die Sehnsucht kennt (TTBBB, D656), the fourth of six essays at Mignon’s song, demonstrates his ever-widening conception of what could be treated as a partsong: a girl’s lyric sung by five men! Here he relied almost totally on harmonic effects, lush even by his standards, using figuration only at the rhetorical break in the poem: “Es schwindelt mir, es brennt mein Eingeweide.” 35 In Ruhe, schönstes Glück der Erde (TTBB, unknown poet, D657), Schubert used three rhythmic signs as imagery. The first stanza, set in a rocking 6/8 meter, apostrophizes “Rest,” comparing its blessed calm to “a grave among flowers.” After the middle stanza has introduced a dotted rhythm to represent “the storms of the heart,” the lullaby rhythm returns at the words “are quiet” and “rock to sleep.” With “as they grow, as they increase,” the hemiola version of 6/8 comes in as a second sign for unrest. The third and final stanza begins as a beautifully varied version of the opening, but the hemiolas reappear briefly when the poet speaks of the soul “rising from the grave.” The ending suggests that the desired “rest” is the union of the soul with Nature in death.

In December 1820 Schubert set Moses Mendelssohn’s translation of the Twenty-third Psalm (SSAA with piano) for his new friend Anna Fröhlich, who taught at the Vienna Conservatory. This celebrated setting received many performances by her pupils over the years, from a semi-public examination concert in 1821 under the auspices of the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde to a “Grand Pupils’ Concert” in 1828 at the Kärntnerthor Theater. Fröhlich also commissioned several other works for her students, including one of his late masterpieces. 36 An account of Schubert’s part-songs is, however, largely a chronicle of his works for male voices. 37

The concert of March 7, 1821, at the Kärntnerthor Theater that featured Erlkönig marked Schubert’s first breakthrough with the Viennese public. Also on the program were the partsongs Das Dörfchen (TTBB, Gottfried August Bürger, D598) and the final version of Gesang der Geister über den Wassern (D714). These represent the poles of his mature work in the genre: the former, his unpretentious, genial vein; the latter – for the unusual medium of four tenors and four basses with instrumental accompaniment by two violas, two cellos, and a double bass – his aspiration to compose an artistically ambitious concert piece. Yet Das Dörfchen was an outstanding success – the audience demanded it be repeated – while Gesang der Geister failed utterly.

Schubert had sketched Das Dörfchen in December 1817 and completed it in 1818; he composed it even as he tried out radically new possibilities in other partsongs. In this one, though, he had come up with a formula that worked over and over with both audiences and critics: a sentimental text set for male voices in square-cut phrases and conventional harmonic progressions, mostly homophonic but with a simple canon toward the end. The mutability of taste becomes an issue in Schubert’s social music only in trying to account for the popularity of this composition and its successors. What did they hear in Das Dörfchen that we do not? And how could they not have recognized the genius of his Goethe-setting?

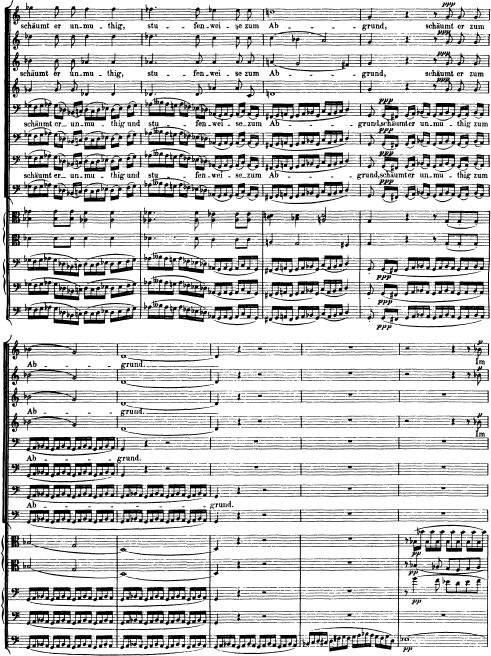

Most likely Schubert composed the new version of Gesang der Geister expressly for the concert at the Kärntnerthor Theater. He began working with the text again during the eventful month of December 1820 – writing first for two tenors and two basses with piano accompaniment before settling on the larger ensemble – and he finished in February, shortly before the concert. The instrumental accompaniment permitted transitions to bind together the various sections of the poem, thus avoiding the fragmentation of the earlier version. In this final setting, he put much greater weight on the overtly symbolic first and final stanzas than on the pictorial center. The conceit that frames Goethe’s poem in the outer stanzas compares the human soul to water, while the middle develops the image of a waterfall: hitting against cliffs on its way into a chasm; gliding through a valley; and, finally, being stirred up by its “lover,” the wind. Schubert opposed the higher and lower registers in his gloriously dark sound-world to suggest both the vastness of the waterfall and the loftiness of Goethe’s symbolism. Most of the time his devices, like dividing the eight voices into tenors versus basses, do not serve precise mimetic purposes (see, for example, measures 19–22 and 27–30). When they do, the effect is astounding, as in measures 97–100, where the change in register and dynamics portrays the cascade’s fall into the abyss (with the double bass at the bottom) after its “angry, stepwise foaming” against the cliffs (see Ex. 7.3 ).

Walter Dürr and Dietrich Berke have argued persuasively that an undated letter from Schubert to Leopold Sonnleithner, in which he declined an offer from the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde to perform a partsong, can only refer to the debacle of Gesang der Geister:

You know yourself how the later quartets were received: people have had enough of them. True, I might succeed in inventing some new form, but one may not count with certainty on anything of the kind. But as my future fate greatly concerns me after all, you, who take your share in this, as I flatter myself, will yourself admit that I must go forward cautiously.

(SDB 264) 38

Schubert had created a “new form,” but the audience had not accepted his attempt to transmute this social genre. During the next few years he made an artistic retreat in it, composing only what he knew the public wanted. In 1822–23, three sets of partsongs appeared in print, two of them with ad libitum piano or guitar accompaniments. 39 In Die Nacht (D983C) from the third set (Op. 17), all short and unaccompanied, he carefully paced the words, working sensitively with a chordal texture and a restricted range of harmonies. Most of the partsongs from this period, however, have lost the appeal that they obviously had then.

Example 7.3 Gesang der Geister über den Wassern (D714), mm. 94–102

Of more interest are Schubert’s settings in 1825 of texts from Sir Walter Scott’s Lady of the Lake, which included, with five Lieder, two strophic partsongs: Coronach for female voices (SSA with piano, D836) and Bootgesang for male voices (TTBB with piano, D835). Schubert seems to have intended these seven pieces, published as Op. 52 the following year, to be sung as a cycle. With Der Gondelfahrer (TTBB with piano, D809) in 1824, and then Wehmuth (TTBB, D825) and Mondenschein (TTBBB, D875) in 1826, he resumed the imaginative imagery and flexible three-part forms of the earlier years. 40 This new surge of creativity – or faith in the audience for this genre – reached a climax in three late works: Grab und Mond (TTBB, D893) and Nachthelle (T, TBBB with piano, D892), both to texts by Johann Seidl and dated September 1826, and Ständchen (A, SSAA with piano, Franz Grillparzer, D920) from July 1827. The dialogue between grave and moon, two stanzas with a free line in the middle, gave rise to an idiosyncratic two-section form. Schubert conveyed the poem’s eeriness through deliberate solecisms in the part-writing: incomplete chords with peculiar doublings. Grab und Mond appeared with the more conventional Wein und Liebe (D901) in an anthology of works aimed at amateur male singing groups, and received critical praise for its outstanding originality in a part of the repertory usually dedicated to mediocrity (SDB 763–64).

Schubert wrote Nachthelle and Ständchen, on the other hand, as concert pieces. His ambitiousness comes through with special force in the Seidl setting; it is evident even in the range of dynamics: from ppp (at the end of the first section) to fff (at the end of the middle section). High, portato chords in the right hand of the pianist set the scene: stars and moonlight glistening over a group of houses. In the central stanzas, the poetic subject welcomes the radiance into the “house” of his heart, as he imagines the boundaries between what he sees and himself breaking. A traditionally bright modulation from E flat to C major in a piano interlude prepares the transfigured return of the opening.

Ständchen, like such earlier partsongs as Gebet (SATB, D815) and Des Tages Weihe (SATB, D763), was an occasional work, in this case a birthday present from Anna Fröhlich to one of her young pupils, but it forms a companion piece to Nachthelle. In both compositions, Schubert made effective use of a solo versus tutti texture to spin out phrases and create sections on a grand scale; in other respects, they complement rather than resemble each other. Each work has three clear sections. The tonal scheme overflows the borders of the sections in Nachthelle, with a modulation early in the first and no return to the tonic until well in the third. In keeping with his altogether more moderate conception in Ständchen, the first and third sections are self-contained. For while the text of Nachthelle and its setting portray an intense subjectivity, the subject-matter of Ständchen connects it to the partsong tradition of conviviality: this serenade celebrates friendship. Ständchen received its first performance at a birthday party in a private garden. Fröhlich’s students later sang it at an “Evening Entertainment,” and Schubert chose it for the concert of his compositions on March 26, 1828. His work in the social genres culminates fittingly in Ständchen: a piece suitable for performance in all the available venues, and a delicately witty paean to the pleasures of being with other people.

Schubert composed this music with the audiences of his time, not an abstract ideal listener, in mind. While certain partsongs may best be regarded as artifacts of social history, the success of most of this repertory speaks well for those audiences and his understanding of their tastes. The rejection of the somber Gesang der Geister represents the only significant failure. Perhaps he miscalculated a new audience in his first public concert, since we know that a slightly later private performance did succeed (SMF 375–76). Maybe, also, Einstein was only partially wrong when he asserted that “Schubert is more popular in his ‘sociable’ and easy-going guise than when he is uncompromising and great” – wrong because he placed sociability and greatness in opposition. Gesang der Geister can no more be classified as social music than can the C Major String Quintet (D956). Nor did Schubert compose the “Grand Duo” and Nachthelle in his sociable manner. But Ständchen with, among other works, the four-hand Rondo in A and the thirteenth Valse sentimentale represent summits in that style. More temperate than “uncompromising,” these masterpieces of subtle phrase rhythms, too, are the great Schubert.