8 Schubert’s piano music: probing the human condition

FOR ALFRED BRENDEL ON HIS 65TH BIRTHDAY

Long underestimated, Schubert’s compositions for piano have recently begun to assume their rightful place beside Beethoven’s legacy as works of almost unparalleled expressive range and depth. Several factors contributed to their neglect: the fact that much of this music remained unpublished during Schubert’s lifetime; the dominance, in these works, of musical expression over technical virtuosity; and the overpowering influence of Beethoven, whose works set standards that are not directly applicable to Schubert. Complaints of an alleged looseness of organization in Schubert’s music, as expressed by critics like Theodor W. Adorno, who once described Schubert’s thematic structure as a “potpourri,” have often arisen from an inadequate understanding of the aesthetic idiom of these works. 1 Schubert’s music is less deterministic than Beethoven’s in that it does not present a self-sufficient sequence of events; it seems that the music could have taken a different turn at many points. Yet these very shifts in perspective are often exploited by Schubert as structural elements in the musical form, and they also embody a latent psychological symbolism. A key to this symbolism is found in Schubert’s songs, in which the protagonist, or Romantic wanderer – who assumes the role of the lyrical subject – is so often confronted by an indifferent or hostile reality. Musically, Schubert uses a combination of heightened thematic contrast, juxtaposition of major and minor keys, and abrupt modulation to reflect this duality between internal and external experience, or imagination and perception – between the beautiful, bright dreams of the protagonist, on the one hand, and a bleak external reality, on the other. Beginning around 1820, analogous procedures of thematic contrast appear in Schubert’s instrumental music, and these devices contribute to the remarkable development in his musical style, culminating in the three profound sonatas of 1828 (D958–60). Our discussion will focus first on the solo sonatas and then on the most important pieces in other forms, including music for piano duet.

The sonatas

Schubert’s output of sonatas embraces twenty works, of which several are incomplete, including the impressive C Major Sonata of 1825 (D840), the so-called “Reliquie” Sonata. Some authors count as many as twenty-four, but three of these – in E Major (D154), in C sharp Minor (D655), and in E Minor (D769A) – are too fragmentary to be effectively performed, whereas the Sonata in E flat Major (D568) is a transposed and elaborated version of the Sonata in D flat Major (D567). 2 Least familiar are the first eleven sonatas, from the years 1815–18. This group of works became more accessible with the publication in 1976 of the third volume of sonatas in the Henle edition. 3 Basic uncertainties remain concerning these early sonatas: some movements were left incomplete; some sonatas lack finales; and suspicions that certain movements belong together as parts of the same sonata are in some cases unavoidably speculative. 4 Because of such uncertainties, András Schiff included only complete movements in his recent comprehensive recording of the sonatas, apart from the first movements of D571 in F sharp Minor and D625 in F Minor, which he describes as “fragments of such extraordinary musical quality that their exclusion would mean a major loss.” 5

Schubert of course left fragmentary masterpieces in other genres, most notably the Quartettsatz in C Minor of 1820 (D703) and the “Unfinished” Symphony in B Minor of 1822 (D759). When viewed in the aesthetic context of early Romanticism, his inspired sonata fragments can be distanced from the odium of failure and valued in terms of what Friedrich Schlegel described as a “futuristic” quality. The artistic fragment is thereby conceived as “the subjective core of an object of becoming, the preparation of a desired synthesis. [It] is no longer seen as something not achieved, as a remnant, but instead as a foreshadowing, a promise.” 6 Yet Schubert’s critical judgment in aborting unpromising later movements to masterly torsos deserves respect. 7 His struggle to sustain the level of artistic accomplishment is reflected in the sonata fragments, which occupy a significant place in his creative development. A piece like the opening Allegro moderato of the F sharp Minor Sonata (D571) from 1817, as Dieter Schnebel has observed, already displays that uncanny suspension of sound and time so characteristic of many later Schubertian works. 8 Here soft rising arpeggiations of the left-hand accompaniment open a tonal space filled out by the main theme, which yields in turn to a thematic variant of the accompaniment figure. As the bleak melancholy of F sharp minor gives way to the brighter tonal sphere of D major, the flowing figuration and subtle harmonic nuances enhance the change, elaborating the sound as if in resistance to the inevitable passage of time or the transience of life itself.

Schubert’s fragmentary piano sonatas of earlier years often reflect a tension between Classical models and his own distinctive evolving style. The influence of Beethoven’s sonatas tends to surface in Schubert’s works in the corresponding keys: D279 in C Major shows the impact of the “Waldstein” Sonata, Op. 53, whereas the Rondo in E Major (D506) was evidently inspired by that of Beethoven’s Op. 90: a lyrical rondo in the major mode follows a terse opening movement in E minor. Among the most impressive of these early pieces is the F Minor Sonata (D625/505) from 1818, whose opening Allegro of D625 shows a complex affinity to Beethoven’s “Appassionata” Sonata, Op. 57, in the same key. 9 In this F Minor Sonata, though not in all of its companions, the young Schubert breaks free of the burden and anxiety of influence. His resourceful reinterpretation of such compositional models became an abiding trait, which reached its culmination only in 1828, in works like the rondo finale of the A Major Sonata (D959).

In the earlier A Major Sonata (D664), a lyrical Allegro moderato and a meditative slow movement are joined to a vivacious, waltz-like finale – a movement which may have helped inspire the finale of Schumann’s Piano Concerto, Op. 54. This sonata was written in Steyr during the summer of 1819, when Schubert also composed his popular “Trout” Quintet (D667) in the same key. The three movements of D664 are linked through a subtle network of motivic relations. The appoggiatura B-A from the end of the first movement becomes the basic motif of the ensuing Andante, where it is varied and reharmonized: at the reprise this figure is treated in dialogue between the hands, and in the coda Schubert darkens the inflection to B -A, thereby setting into relief the descending scale from B which launches the exuberant finale. That falling scale, in turn, balances the ascending scalar passagework from the opening movement, as is first heard at the close of the lyrical opening period of this Allegro moderato. This delightfully intimate sonata is not untouched by darker shadows, but it displays little of the dramatic contrasts and formal expansiveness characteristic of later sonatas.

-A, thereby setting into relief the descending scale from B which launches the exuberant finale. That falling scale, in turn, balances the ascending scalar passagework from the opening movement, as is first heard at the close of the lyrical opening period of this Allegro moderato. This delightfully intimate sonata is not untouched by darker shadows, but it displays little of the dramatic contrasts and formal expansiveness characteristic of later sonatas.

Since so many of Schubert’s works remained unpublished during his lifetime, their opus numbers usually lack any chronological significance. Although a relatively early work, the A Major Sonata (D664) bears the posthumous opus number 120. Even more misleading are the opus numbers of Schubert’s three sonatas in the key of A minor. The A Minor Sonata (D784) from 1823, for instance, received opus number 143, yet it was composed two years earlier than the four-movement Sonata Op. 42 (D845) – the first of the three sonatas published during Schubert’s lifetime. Like his still earlier A Minor Sonata of 1817 (which was posthumously published with the still higher opus number of 164) Op. 143 contains only three movements and lacks a scherzo or minuet preceding the finale. This is an unusually concentrated work characterized by a somber “orchestral” coloring: the bass accompaniment of the principal theme of the first movement suggests drum rolls and the accents of trombones. As Alfred Einstein has pointed out, the second subjects of the outer movements stand apart, like “visions of paradise” in the major mode; 10 like the wanderer’s dreams and recollections of his first lost love in Schubert’s song cycle Winterreise (D911), these lyrical visions are fragile and transitory, and are dispelled by the return of forceful accents and turbulent music in the minor.

Example 8.1 Sonata in A Minor, Op. 42 (D845), first movement, mm. 1–8

A pair of works from 1825 – the fragmentary C Major Sonata (D840), and the big Sonata in A Minor, Op. 42 (D845) – mark a new stage in Schubert’s resourceful treatment of thematic contrast and development within the sonata design. Like all the later sonatas, D845 has a four-movement design. The beginning of the opening Moderato presents a quiet, mysterious, unharmonized motif outlining the tonic triad, followed by a series of chords with a descending bass line (see Ex. 8.1 ). In measures 4–6, this motif is restated one pitch higher, so that the accented highest tone is F, corresponding to the E of measure 1. This rising step E-F and its transpositions pervade all of the subsequent themes of the movement, and often seem even to control the direction of the harmonic progressions and changes in key. Repeatedly, the vigorous flow of the other themes is interrupted by reappearances of this unison motif in the minor mode from the outset of the work. This motif assumes thereby the character of a motto, or seminal element, out of which the piece evolves through thematic development and variation, and to which it suddenly and repeatedly returns. It is as if this musical material represented an object of contemplation, whose subsequent appearances arrest the action of the more dynamic themes of the sonata form, the underlying substance of which is all prefigured in the opening motto. Such is the nature of Schubert’s musical form that the appearances of an important theme or motif can seem spontaneous and surprising, while possessing at the same time a quality of inevitability. In the A Minor Sonata, the return of the original form of the thematic motto at the end of the development is presented in a wonderfully subtle series of modulations, which conceal the exact beginning of the recapitulation. The coda, on the other hand, begins with an astonishing and unexpected, yet eminently logical, reinterpretation and enlargement of the rising motivic step E-F as a gateway to a new key area, F major. Relationships such as these are readily heard by the sensitive listener, and it does not require much technical knowledge of music to begin to appreciate them.

Example 8.2 Sonata in C Major (D840), first movement, mm. 114–18

As John Reed has pointed out, the expressive associations of this initial unharmonized thematic material in the A Minor Sonata are clarified by its use in a song which is exactly contemporary, Totengräbers Heimwehe (D842). 11 Its sinister implications are confirmed here by the words the music is used to accompany: “Abandoned by all, cousin only to death, I wait at the brink, staring longingly into the grave.” The A Minor Sonata is only one of a number of important instrumental works by Schubert associated with death, including the D Minor Quartet (D810, with its use of Schubert’s song Der Tod und das Mädchen [D531]), the Fantasy in F Minor for piano duet, Op. 103 (D940), and the C Minor Piano Sonata from 1828 (D958).

The companion work to D845 is the C Major Sonata (D840) from early 1825 in two movements, the minuet and finale having been left incomplete. This piece is missing from many older editions of Schubert’s sonatas. Its opening movement, marked Moderato, is related thematically to the A Minor Sonata, Op. 42, and displays the same close motivic network linking the second subject to the principal theme. The tonal plan is wide ranging: the second subject begins in the remote key of the leading tone, B minor, and the beginning of the recapitulation is here once again merged with the end of the development by an effective series of modulations. The development is forcefully dramatic in character, its climax leading again to B minor, and relies heavily on rhythmic diminution of the opening motif comprising six beats, which are compressed into a figure of triplet eighth notes (see Ex. 8.2 ). Towards the end of the movement, a powerful chordal passage leads to an emphatic C major cadence but fails to achieve finality, and the Moderato ends quietly, with chords derived from the opening theme. The following slow movement is tragic in character, and it too is linked thematically to the opening subject of the first movement. This unfinished Sonata in C Major is a worthy counter-part among the sonatas to Schubert’s “Unfinished” Symphony, and should receive more attention.

The D Major Sonata, Op. 53 (D850), dates from later in 1825, and was written at Gastein in the Austrian Alps, just after Schubert’s main period of work on the “Great” C Major Symphony (D944). This was the second sonata published during the composer’s lifetime. The work is unusual in the swift and ardent character of the opening Allegro vivace, which demands considerable virtuosity, and in the air of naïveté of the rondo finale, which perplexed Robert Schumann. 12 The first movement opens with an emphatic tonic chord, followed by a motif of repeated chords treated in rising sequences. This material assumes a majestic and almost orchestral character at the beginning of the development. The bold and extensive second movement, marked Con moto, also requires a faster tempo than most of Schubert’s other slow movements. Its continuity springs from two initial rhythmic motifs permeating the principal and subsidiary themes respectively. The formal plan is that of a rondo, in which the rhythmic motif of the subsidiary theme is combined with – and for a brief, climactic moment overshadows – the final presentation of the principal theme near the conclusion. The scherzo of this sonata is symphonic in scope and character, and introduces rhythmic complications involving a combination of 3/4 and 3/2 meters. The lively and forceful character of the music later gives way to softer passages containing a charming counterpoint of rhythms, in which every second measure contains accents on each beat of music, divided between the hands, and it is with this material that the scherzo quietly ends. In the rondo finale, the appearances of the main theme in the high upper register are increasingly decorated through melodic ornamentation, and are effectively set into relief by the two contrasting episodes, especially the second episode with its turbulent middle section in G minor.

The third and last of the sonatas published in Schubert’s lifetime is the Sonata in G Major, Op. 78 (D894), which was written in the fall of 1826, several months after his string quartet in the same key. Older editions of this sonata contain the title “Fantasie” for the first movement. 13 The mood of lyric serenity in which this work begins seems to recall the opening of Beethoven’s Fourth Piano Concerto in G Major, Op. 58, especially since the initial, sustained sonorities of the two pieces are virtually identical. In both works, the opening G major chord – with B as the highest pitch – is magically transformed by a later shift into the tonality of the mediant, B major, a goal which in Schubert’s sonata is reached through B minor, a key more closely related to the tonic. The second subject of this movement comprises a playful, dance-like theme subsequently elaborated in an ornamental variation. In the development, abbreviated but emphatic statements of the opening subject – dramatized by use of the minor mode and the high upper register of the piano in the right hand, as well as by an intensification in dynamics to fff- are juxtaposed with similarly shortened but ornamented appearances of the dance-like theme in the major. This juxtaposition of contrasting themes is thus used as a structural device, and as a means for building to the expressive climax of the musical form. At the same time, it evokes musically the dichotomy of harsh reality and beautiful dreams familiar from the world of Schubert’s Lieder.

The second movement is an Andante, in which appearances of a calm lyrical theme are separated by two turbulent episodes in minor keys. As in Schubert’s other slow movements of this type, some of the rhythmic animation of the first episode is carried into the subsequent return of the principal theme, while at the end of the movement, this theme is recalled in its initial simplicity. The last two movements, a Menuetto and rondo finale, are linked rhythmically through their persistent use of an upbeat figure of four rapidly repeated chords or octaves. Another rhythmic figure outlining a turn connects the minuet to its trio, which is a transfigured Austrian Ländler of the utmost quietude and delicacy.

The three sonatas completed in September 1828 each contain reminiscences of Beethoven, who had died in March 1827, and whom Schubert was to survive by only twenty months. The influence of Beethoven’s 32 Variations in C Minor, WoO 80, on the opening theme of Schubert’s C Minor Sonata, D958, is obvious and striking, but still more significant is the manner in which Schubert departs from his model, extending the progression into a lengthy opening period of vehement and tragic character. Especially impressive in this movement are the mysterious, chromatically veiled passages of the development. The second movement contains a hymn-like theme in A flat major, which returns in variation after dramatic episodes in other keys, in a manner not unlike the slow movement of Beethoven’s Sonate pathétique. Op. 13, in the same key. At the end of this movement, a remarkably subtle passage restates and concisely summarizes the entire modulatory plan, utilizing surprising enharmonic shifts in tonality. Following the scherzo in C minor is a weighty finale based on a persistent tarantella rhythm comparable to the finales of Beethoven’s E flat Major Sonata Op. 31 No. 3 or Schubert’s own D Minor Quartet. In this rondo-sonata movement, however, the poetic evocation is perhaps less of a dance than of a ride on horseback, thrilling and yet strangely ominous. The obsessive, driven character of the music shifts focus in the central episode in B major, which presents a seductive, cajoling vision reminiscent of the Erlking.

That Schubert’s last three sonatas are intimately connected through motivic and tonal means has received increased recognition since Alfred Brendel’s detailed analytical study and most recent recordings. 14 The evidence of Schubert’s surviving compositional drafts and autograph scores shows that this interconnected sonata trilogy emerged only gradually, after he had begun work on the final Sonata in B flat, the genesis of which overlapped with that of the preceding Sonata in A Major. On the other hand, the parallel at the outset of the first sonata to Beethoven’s C Minor Variations, WoO 80, was originally even more literal, as Hans-Joachim Hinrichsen has pointed out. 15 In the end, the first movement of the C Minor Sonata offered a rich quarry of musical relationships which Schubert utilized in each of the two succeeding works.

In the A Major Sonata (D959) the influence of Beethoven is felt most in the impressive finale, which was modeled on the finale of Beethoven’s Sonata in G Major, Op. 31 No. 1, as both Charles Rosen and Edward T. Cone have shown. 16 Rosen also pointed out that Schubert surpassed his model, and this is nowhere clearer than in the elaborate coda, in which phrases from the principal theme are broken off into silence, and reharmonized in unexpected keys. Just as the thread seems to be regained, we plunge into a whirlwind Presto, which is itself interrupted by a resumption of the reprise of the theme, leading to an allusion, in the final measures, to the principal theme of the first movement. This first-movement theme also forms the basis for the coda of that movement, where it is presented in a texture and articulation unmistakably suggesting chamber music for strings, reminding us thereby of Schubert’s other major compositional preoccupation during these last months of his life, his great C Major String Quintet (D956).

The center of gravity of the A Major Sonata lies in the extraordinary slow movement in F sharp minor, marked Andantino. The almost hypnotic effect of its main theme recalls several of the Heine Songs and Der Leiermann from Winterreise (D911, 24). Some indication of its expressive associations may be gained from analogy to the song Pilgerweise (D789), where similar music in F sharp minor is set to the text “I am a pilgrim on the earth, and pass silently from house to house…” The controlled melodic repetitions of this theme stress a few important pitches in a narrow register, and create an atmosphere of melancholic contemplation, or obsession. The almost static quality of this music is also connected to its structural role in the movement as a whole, however. Nowhere else did Schubert employ such an extreme contrast as in this Andantino, where the music of the following middle section seems to unleash not just turbulence and foreboding, but chaotic violence. Here, as so often in Schubert, the contrasting sections are complementary, and need to be heard in relationship to one another. The outer sections of this ternary musical form thus embody the reflective mode of the lyrical subject, but the music of the contrasting middle section annihilates this frame of reference. Descending sequences of amorphous passagework reach C minor, the most remote of key-relations from the tonic, and the music continues to build relentlessly, exploiting the most extreme registers and a structural use of trills as a means of sustaining the tension of the musical lines at fixed levels of pitch. The approach to C sharp minor at the climax is achieved in a passage of savage intensity. Following this climax, a fragile recitative appears, only to be broken off repeatedly by massive accented chords (see Ex. 8.3 ).

Example 8.3 Sonata in A Major (D959), second movement, mm. 120–31

In this movement, as Alfred Brendel has observed, one can sense an affinity between Schubert and his great artistic contemporary, the aging Francisco Goya, who in his etchings and paintings of war left a damning indictment of human cruelty, and of the fragile vulnerability of individual human beings confronted by power. In this sense, the Andantino of Schubert’s A Major Sonata bears comparison with a painting such as Goya’s The Third of May, 1808 , which is based on the contrast between the hard, inhuman brutality of the soldiers making up the firing squad, and the soft, defenseless, and crumbling human targets. The nineteenth-century myth of Schubert’s easy-going naïveté dies hard, and few artists have probed so deeply into the tragic aspects of the human condition.

In the last two movements of the A Major Sonata, Schubert offers more positive perspectives on the music of the Andantino. In perhaps no other work is the network of thematic correspondences between movements so far-reaching as here. The brilliant arpeggiated chords that open the scherzo reshape the dark arpeggiated sonorities that had closed the Andantino, for instance, whereas the trio reincarnates the opening motto theme of the first movement. Schubert reworked the main subject of the rondo-sonata finale from the slow-movement theme of his earlier Sonata in A Minor (D537) from 1817, and Charles Fisk has suggested that this preexisting theme must have served as Schubert’s point of departure and even “as the source of the sonata’s principal motives.” 17 In the finale, a window on the Andantino opens at the culmination of the developmental central episode leading to the reprise. This massive passage rests not on the dominant of the tonic A major but instead on C sharp, dominant of the F sharp major with which the recapitulation begins. Broken chords in the middle register alternate between chords of C sharp major and F sharp minor, stressing the same pitches as in the main theme of the Andantino, and Schubert heightens the characteristic semitone tension from that movement by pitting the minor ninth D in the high register against its resolution C# several octaves below. The exquisite F sharp major texture with which the reprise begins is no mere “false” recapitulation: it absorbs a transfigured vision of the key of the tragic slow movement glimpsed through the veil of the rondo theme.

Like its companion works in C Minor and A Major, the final Sonata in B flat Major (D960) is representative of Schubert’s finest and most advanced style, and combines lyrical charm, structural grandeur, and a daring but controlled treatment of key-relations. The first movement begins, in the words of Donald Francis Tovey, with a “sublime theme of the utmost calmness and breadth,”

18

whose first half ends mysteriously in a long, low trill on G . Following the second phrase of the theme, the trill is heard on B

. Following the second phrase of the theme, the trill is heard on B , but it soon unfolds downwards to initiate the sustained pedal point on G

, but it soon unfolds downwards to initiate the sustained pedal point on G that controls a restatement of the main theme in that key. As is characteristic of Schubert, the exposition incorporates three main keys and thematic areas, the second of which – in F sharp minor – may be linked to the mysterious trill as well as to the Andantino of the preceding sonata.

that controls a restatement of the main theme in that key. As is characteristic of Schubert, the exposition incorporates three main keys and thematic areas, the second of which – in F sharp minor – may be linked to the mysterious trill as well as to the Andantino of the preceding sonata.

The development section is based largely on the third thematic area from the exposition, with its dactylic rhythm and similarity to Schubert’s song Der Wanderer

(D489), and modulates widely before building to a great climax in D minor. In the ethereal passage which follows, the sublime opening theme, now preceded by its trill, is stated softly in the high upper register. As Tovey and others have observed, this recall of the main theme is delicately poised, not “in” but “on” the tonic key, as if contemplated from a vast distance. After two further appearances of the trill on G , the ensuing recapitulation assumes a character of overwhelming immediacy and inwardness. As in the finale of the A Major Sonata, Schubert enhances the return of his main theme through a subtle wealth of thematic allusion and an impressive mastery of tonal perspective.

, the ensuing recapitulation assumes a character of overwhelming immediacy and inwardness. As in the finale of the A Major Sonata, Schubert enhances the return of his main theme through a subtle wealth of thematic allusion and an impressive mastery of tonal perspective.

The slow movement in C sharp (D flat) minor, marked Andante

sostenuto, assumes an almost static character due to a recurring accompanimental figure which ranges a span of four octaves under and over the melody. The contrasting middle section of this movement is suggestive of a song, and combines a lyrical melody with an accompaniment in rapid notes, and an active bass line. The playful gaiety of the following scherzo movement is enhanced by its effective changes from major to minor, and its wide tonal range. Particularly striking is the manner in which Schubert approaches the reprise of the scherzo theme in B flat major from the remote but adjacent key of A major. Harmonic subtleties are even more conspicuous in the finale, which opens with a call to attention: a G octave in the left hand appended to a theme which persistently begins in the “wrong” key, C minor, instead of B flat major. This striking gesture may be connected not only to the opening of the finale of Beethoven’s string quartet in this key, Op. 130, but also at least distantly to the mysterious trill on the minor submediant in Schubert’s first movement. Only with its final appearance in this rondo-sonata movement is this material explained and completely resolved: the octave call-note descends by semitones through G to F, the dominant note of B flat, and a brilliant coda caps Schubert’s very last composition for the piano.

to F, the dominant note of B flat, and a brilliant coda caps Schubert’s very last composition for the piano.

Fantasies, Moments musicaux , Impromptus, and Klavierstücke (D946)

Many of Schubert’s piano works other than sonatas consist of short pieces grouped into collections, such as the Moments musicaux , Op. 94 (D780), the Impromptus, Opp. 90 and 142 (D899 and 935), and the Klavierstücke (D946), not to mention the numerous collections of dances. Another genre that occupied the young Schubert was the fantasy; his very earliest compositional efforts include several such works. His first outstanding composition in this vein is the “Wanderer” Fantasy in C Major, Op. 15 (D760) of 1822. The “Wanderer” Fantasy consists of four movements – an Allegro, Adagio, scherzo, and finale employing fugue – which are closely interrelated thematically, and performed continuously, without pauses between the movements. The basic unifying element is a dactylic rhythm linking the outer movements with the focal point of the whole work, a self-quotation from Schubert’s song Der Wanderer in the theme of the slow variation movement. The relationship of these movements also suggests an open-ended sonata form, with the Allegro comprising the exposition and the Adagio standing in place of a development section. This structural plan of interconnected movements broke new ground, and provided an important model for the new genre of the symphonic poem as cultivated by Franz Liszt in the 1850s, and many other composers in the last decades of the nineteenth century. 19 The special popularity of this technically difficult work owes much to Liszt, in fact, who not only played it in an arrangement for piano and orchestra but also offered a solo version which for once makes portions of the piece easier to play.

Example 8.4 Moment musical No. 6 in A flat Major, Op. 94 (D780), mm. 61–77

Schubert’s Impromptus and Moments musicaux

develop a tradition of characteristic piano pieces stemming from the Bohemian composer Václav Tomášek, and transmitted to Vienna by his pupil Jan Voříšek, who took up residence there in 1818. Most of these pieces were apparently written in the last two years of Schubert’s life, but some date from earlier years. The Allegretto in A flat comprising the last of the Moments musicaux

was actually one of Schubert’s first published examples, since it originally appeared as an independent piece, entitled “Plaintes d’un Troubadour,” in December 1824. (The third one had been published the year before as “Air russe.”) Like many of this type, it is in ternary form, with a trio in D flat major serving as the contrasting section. In the main section of the piece, the music is inexorably drawn from within into the tonal sphere of the foreign key of the flat sixth, F flat, spelled enharmonically as E major. This gravitation toward E major begins insidiously, as melodic stress on E or F , and gradually gains strength through repetition until it usurps the tonality, creating a sudden shift in the key perspective. Even near the end of the piece, after the tonic A flat major has been reestablished in a reprise of the opening, the tell-tale F

, and gradually gains strength through repetition until it usurps the tonality, creating a sudden shift in the key perspective. Even near the end of the piece, after the tonic A flat major has been reestablished in a reprise of the opening, the tell-tale F returns, and the music veers dramatically away from the tonic (see Ex. 8.4

). The final cadence is shadowed by this conflict in key perspective, and the music resolves precariously to an unharmonized A

returns, and the music veers dramatically away from the tonic (see Ex. 8.4

). The final cadence is shadowed by this conflict in key perspective, and the music resolves precariously to an unharmonized A , doubled in octaves, in the closing measures.

, doubled in octaves, in the closing measures.

The second and fourth of the Moments musicaux contain internal contrasting sections, while the third and fifth pieces, both in F minor, are tightly unified by their unbroken rhythmic movement. The main theme of the second piece in A flat major is somewhat reminiscent of the beginning of the G Major Sonata in its rhythm, broad choral texture, and serene character, while the two episodes present a haunting melody in F sharp minor, accompanied by triplets in the left hand. In the fourth piece, the expressive contrast of the principal sections is striking: a moto perpetuo in C sharp minor in a stratified Baroque texture is interrupted by a soft, ethereal theme in the major reminiscent of a dance, which recurs fleetingly before the conclusion. The first of the Moments musicaux , in C major, is also in ternary form, but with a less pronounced contrast between the principal sections. This piece begins with a summons: a unison triadic fanfare motif which later returns in imitation, in several voices.

The first of the Impromptus, Op. 90, also opens with an arresting introductory gesture: sustained octaves on G, marked fortissimo. This gesture sets into relief the quiet, declamatory phrases of the main theme in C minor, which at first appear harmonized. The rhythm is processional, and the atmosphere is that of a narrative, evoking the landscape of ceaseless wandering familiar from Schubert’s song cycles. This narrative quality is sustained through repetition of the theme against a changing harmonic background, as well as through motivic relationships linking the main theme to the secondary theme, beginning in A flat major. The secondary theme, in turn, lends its accompaniment in triplets to subsequent appearances of the main theme, and the resources of modulation and modal contrast are effectively exploited. Near the end, the triplets disappear, the initial declamatory phrases are sounded together with subdued references to the octaves on G from the outset of the work, and the music concludes movingly in C major.

The second and fourth impromptus of Op. 90 are in ternary form, and display similarities in character and structure. In both, rapid passagework based on descending scales or arpeggios dominates the outer sections, whereas the inner section or trio contains more declamatory or lyrical material in the minor. The contrast between these sections is most pronounced in the second impromptu, where appearances of an etude-like moto perpetuo in E flat major enclose a central episode all’ongarese in B minor. In the coda, the music of the episode returns, initially in that key, before being diverted to E flat minor. The trio of the fourth impromptu is passionately lyrical, with a beatific glimpse of C sharp major in its second part. Unlike these two pieces, the third impromptu in G flat major is completely unified in mood and texture. This is a broadly lyrical and meditative work, which Einstein described as a “pre-Mendelssohn ‘Song without Words.’” 20

In the Moments musicaux and Op. 90 Impromptus, the individual pieces are admirably contrasted in an open-ended sequence, with the last piece in a different key from the first. The tighter design of the four Impromptus, Op. 142, led Schumann to believe that parts of this opus originally belonged to a sonata. 21 The first section of the opening piece, an Allegro moderato in F minor, is indeed structured much like a sonata exposition, but this is not true of the middle section based on an expressive dialogue between treble and bass accompanied by arpeggios in the middle register. After a full recapitulation of the opening section, mainly in F major, the music from the middle section returns, first in the tonic minor, then in the brightness of the major. In the closing moments, F minor is reaffirmed in a terse statement of the opening theme, with a new cadence.

The second impromptu is a dance-like Allegretto in A flat major, with a trio in D flat major employing arpeggiated textures. The basic rhythm of both sections stresses the normally weak second beat of the triple meter. The third piece is a charming set of five variations in B flat major, on a theme Schubert had used twice before: in the incidental music to Rosamunde (D797), and the slow movement of the A Minor String Quartet (D804).

The fourth impromptu of Op. 142 is one of Schubert’s most brilliant works. The enormous rhythmic vitality of the outer sections derives in part from unpredictable accentuation, and alternations of duple and triple meter. The cadential trills are emphasized by syncopated accents, generating energy which is released in rapid scale passages. In the contrasting middle section, the climax is reached in scale passages for both hands, culminating in a swift, four-octave descent in A major across the entire keyboard. Other passages in this impromptu suggest the influence of Hungarian rhythms. Especially impressive is the conclusion: a quiet, mysterious passage is broken off by a powerful and virtuosic coda employing octaves in both hands. Just as the final cadence in F minor is affirmed in the highest register, Schubert recalls the rhythm from the middle section in chords in the left hand, while resolving the climax of that section to the tonic in a dramatic and astonishing scalar descent of six octaves through the entire tonal space.

The three Klavierstücke (D946) were not arranged as a set by Schubert, but were assembled by Johannes Brahms, who prepared the first edition of these pieces for publication in 1868. The third piece may predate the first two, which were composed in May 1828. In character and form, these works resemble the Impromptus, though there is an al fresco quality entirely their own. The autographs of these pieces are probably not complete in every respect as they stand, and certain tempo markings, such as in the internal episode of the third piece, for instance, appear to be missing. The strength of the internal contrasts is greater than in the Impromptus. The first piece juxtaposes a turbulent Allegro assai in E flat minor with an elaborate lyrical episode in B major in a slower tempo; Schubert wrote down a second slow episode in A flat major, but canceled the passage in the autograph score. The third piece employs a ternary design in which music of a lively and cheerful Bohemian flavor foreshadowing Smetana encloses an extended episode characterized by an almost hypnotic immobility, owing to its static and repetitive rhythmic patterns. In the second piece, on the other hand, the relationship of the contrasting sections is reversed, inasmuch as the opening material is idyllic in character, and the two episodes are more dramatic or agitated. The opening lyrical theme of this Allegretto in E flat major was adapted from the chorus beginning Act III of Schubert’s opera Fierrabras from 1823, as John Reed has pointed out. 22 Like the canceled episode from the first of the Klavierstücke , this theme is reminiscent of a Venetian barcarole in its rhythm and flowing texture, and its frequent melodic parallel thirds are also Italianate in character. Each of the two contrasting sections – in C minor and A flat minor/B minor respectively – introduce smaller note values which reflect an inner agitation in the music. The climax of the first episode is reached when the music turns unexpectedly to C major, with the theme heard in a high register. Use of the high upper register assumes even more importance in the second episode in A flat major, where the music evokes a remarkable quality of yearning, foreboding, and poetic sadness.

Music for piano duet

Our survey of the piano works would remain seriously incomplete without mention of Schubert’s music for piano duet, which includes the Sonatas in B flat Major (D617) and in C Major “Grand Duo” (D812), and three compositions composed in 1828: the Allegro in A Minor “Lebensstürme” (D947), the Rondo in A Major (D951), and the Fantasy in F Minor (D940). The Fantasy is one of Schubert’s most outstanding pieces, and shows a remarkable treatment of thematic, tonal, and modal contrast, which we shall examine in some detail. While clearly indebted to the model of his songs, this composition goes far beyond them in exploring the structural and expressive possibilities inherent in the controlled juxtaposition of strongly contrasting themes. Like the earlier “Wanderer” Fantasy, the F Minor Fantasy consists of four interrelated movements performed without a break. 23 In both works, an opening Allegro is followed by a slow movement, scherzo, and final movement employing fugue. The thematic treatment in the duet fantasy, however, has no parallel in the earlier work, and involves a particularly close relation between the outer movements of the cyclic form.

Example 8.5 Fantasy in F Minor, Op. 103 (D940), mm. 37–52

The lyrical opening theme of the F Minor Fantasy bears some affinity to the processional themes of pieces like the Andante of the “Great” C Major Symphony, and Gute Nacht and Wegweiser from Winterreise. Its processional character derives from a regularity of rhythmic pulse in duple meter and the steady octaves in the bass, repeated twice per measure. As Eric Sams has pointed out, the melody itself has an insistent conversational character, suggesting the rhythm and intonation of speech. 24 The overall quality of the theme is narrative; it seems to evoke the landscape of ceaseless wandering familiar from the two Müller song cycles.

After the repetition of the initial thematic statement, the music shifts into A flat major, and the lyrical melody passes to the bass. This section represents the middle part of a ternary thematic construction. The opening theme returns, however, in F major, and the brighter sound of the major mode is enhanced by richer harmonies in the bass and the emphasis on A in the melody (see Ex. 8.5 ). Schubert also exploits the high upper register of the piano in the last phrases before the melody cadences in the tonic.

That cadence brings a shock – a contrasting second theme in F minor,

which is utterly opposed to the opening theme in affective character. The menacing character of the new theme is due to its stress on D , the dissonant minor second above the dominant note, its pointed accents, and its funereal rhythm. This rhythm, first announced in the bass, consists of the pattern

, the dissonant minor second above the dominant note, its pointed accents, and its funereal rhythm. This rhythm, first announced in the bass, consists of the pattern  , representing a related but more energetic form of the rhythm

, representing a related but more energetic form of the rhythm  associated by Schubert with death in the song Der Tod und das Mädchen.

associated by Schubert with death in the song Der Tod und das Mädchen.

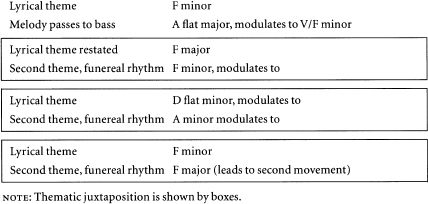

Figure 8.1 Fantasy in F Minor, first movement: the tonal plan

By analogy with Schubert’s songs, the statement of the first lyrical theme in major assumes an air of unreality, of illusion. The illusion is rudely shattered by the plunge into minor and the threatening second theme. This drastic thematic juxtaposition then serves as the structural basis for the rest of the first movement. After the initial statement of the second theme, the lyrical theme returns in D flat minor, closing with a cadence in A minor, where it is once again juxtaposed with the theme in funereal rhythm. A last statement of the opening theme in F minor completes the series of modulations through a circle of descending major thirds, F–D flat–A–F. This appearance too is juxtaposed with the second theme, which, in a reversal of roles, now appears transformed – pianissimo, legato , and in major. The statement of the second theme in major has a resolving effect, serving to round off the first movement before the dramatic opening of the Largo in F sharp minor. The tonal and thematic plan of the first movement is shown in Figure 8.1 .

The dual perspective of the F Minor Fantasy reaches its culmination only in the last measures of the entire work. The last movement represents a recapitulation and development of the first movement. After a sudden modulation from the key of the scherzo, F sharp minor, the lyrical theme returns in F minor. The entire opening section is then restated, in somewhat condensed form, up to the crucial passage in which the lyrical theme appears in the major mode. From this point, the work takes a new course.

Example 8.6 Fantasy in F Minor, Op. 103 (D940), mm. 550–70

The dark-hued second subject now becomes the basis for an extended fugue. In the latter part of the fugue, the principal rhythmic motif undergoes a series of canonic imitations, while its free inversion is worked into the rhythmic accompaniment as triplets in the bass. The music then builds toward a tonic cadence in F minor, which is twice avoided before it appears at the final statement of the fugal theme in the lowest register. Again the music comes to a climax on a series of diminished-seventh chords, with the expectation of a cadence in the tonic. This time, however, the cadence is denied: the fugue simply breaks off on the dominant (see Ex. 8.6 ).

The conclusion of the Fantasy after this dramatic silence is one of the most extraordinary passages in Schubert’s works. It begins by recalling the plaintive lyrical theme from the outset of the work, but the reminiscence lasts only a few measures. The last measures, rising in sequence, already pick up the darker coloring of the second theme; then, ten measures before the close, Schubert steps from one theme into the other

through a subtle transformation of his material. The closing eight-measure statement is a development of the second theme, employing not only the funereal rhythm, but the melodic stress on D ; the descending triplets in the bass are derived from the fugue. In these final measures, the dark-hued second theme supersedes the lyrical theme to provide the cadence and resolution of the whole work.

; the descending triplets in the bass are derived from the fugue. In these final measures, the dark-hued second theme supersedes the lyrical theme to provide the cadence and resolution of the whole work.

This cadence owes much of its power to the fact that it serves as the true conclusion of the fugue, after the abrupt interruption and the reminiscence of the lyrical theme. The actual cadential progression refers back to several cadential passages in the fugue, in which the dotted rhythmic motif of the subject is extended by a series of quarter notes. This time the progression is strengthened by the presence of a descending chromatic line, doubled in octaves, that highlights the dissonant semitone D –C in the last two chords. The chromatic line, beginning on F, passes through E, E

–C in the last two chords. The chromatic line, beginning on F, passes through E, E , and D, reaching D

, and D, reaching D , in the penultimate chord, which is emphasized dynamically. Schubert’s omission of the implied dominant chord at the cadence results in a kind of enhanced subdominant cadence in which two crucial motivic elements of the work are combined: the D

, in the penultimate chord, which is emphasized dynamically. Schubert’s omission of the implied dominant chord at the cadence results in a kind of enhanced subdominant cadence in which two crucial motivic elements of the work are combined: the D –C semitone relationship in the treble and the fourth in the bass, the thematic hallmark of the opening theme.

–C semitone relationship in the treble and the fourth in the bass, the thematic hallmark of the opening theme.

The overall scheme based on the relationship of these two evocative themes suggests a tragic symbolism analogous to that of Winterreise , and reminds us once more of the close kinship between Schubert’s vocal music and his works for piano. Like the song cycle, the F Minor Fantasy is haunted by a sense of progress toward an inescapable destiny, an idea tied to the universal human theme of mortality. In a sense, the very structure of the Fantasy is posited on this appropriation of poetic content from the world of Schubert’s Lieder. In this remarkable composition, the expressive content of the wanderer’s tragic journey is transformed, as it were, into a purely musical structure, absorbed into the sphere of instrumental music.

Schubert’s F Minor Fantasy, Klavierstücke , Impromptus and Moments musicaux as well as the “Wanderer” Fantasy and the later sonatas reflect an almost unfailing consistency of accomplishment. A combination of directness and intimacy of expression, poetic sensitiveness, and structural control and grandeur is characteristic of Schubert’s mature musical style. His departures from Beethoven’s more deterministic approach are not in themselves a shortcoming, for they are very often inseparable from his basic artistic quest to explore the qualities of experience, as seen from a vantage point whose divided perspective encompasses both external perception and the inward imagination.