9 Schubert’s chamber music: before and after Beethoven

Secretly, in my heart of hearts, I still hope to be able to make something of myself, but who can do anything after Beethoven?

Schubert to Josef von Spaun (SMF 128)

Schubert was not born into a family of professional musicians, as were Bach, Mozart, and Beethoven. As a result, he was never expected to become a virtuoso, never wrote a full-fledged concerto, and showed relatively little interest in composing for virtuosos. 1 Instead his family made music together; and for much of his life Schubert’s compositions (songs, dances, four-hand piano music, but also most of his chamber and orchestral music) were written for Liebhaber , lovers of music, amateurs. When, near the end of his life, he was asked by the publisher of his E flat Piano Trio, Op. 100 (D929), to name a dedicatee, his response was: “This work is dedicated to nobody, save those who find pleasure in it” (SDB 796). Nor did he consort with the best musicians of his day, those at the cutting edge of contemporary music (i.e. the players promoting the music of Beethoven) until relatively late in his career. When he did, the result was a series of masterpieces: his last three string quartets, the Octet, the Piano Trios in B flat and E flat, and the String Quintet in C Major, to name only the chamber works of his last five years (1824–28).

But these impressive compositions rest on a considerable body of earlier chamber music, and to understand the mature Schubert, it is vital to recognize that before he wrote his first large group of successful songs (1814–16) he had already completed at least twelve string quartets and a string quintet. A case can be made that Schubert, the master of the Lied, was as indebted to his experience with instrumental music as was Mozart, the master of opera, to his experience writing instrumental compositions.

Schubert’s chamber music for strings

Schubert’s early interest in string music was a natural one. Before he sang or played a keyboard instrument, he received violin lessons from his father; and when quite young he joined the family string quartet. 2 It is safe to say that most of his string quartets as well as the string trios and the early string quintet were written for this group, perhaps augmented by other players. Since music for strings comprises the largest share of Schubert’s chamber music, it will be discussed first in this chapter.

From 1808 to 1813 Schubert, as a singer in the Royal Chapel Choir, attended and lived at the Vienna City Seminary. This meant that every evening he played in the Seminary orchestra, and at some point became Kapelldiener (assistant to the orchestra’s musical director) caring for the music, instruments, stands, candles, etc. He also led the orchestra, no doubt from the principal violinist’s chair, whenever the director, Wenzel Ruzicka, played at the court opera. The repertory of this group, a symphony and one or two overtures every evening, is important for our discussion.

Schubert’s experience with orchestral music, however, was not limited to the Seminary orchestra. There are reports that friends and neighbors joined the family group and it grew into a small orchestra. 3 Christa Landon, one of the original chief editors of the Neue Schubert-Ausgabe , found arrangements of orchestral works by Haydn and Mozart for string quartet and quintet with the name of Schubert’s father at the top. 4 These obviously formed part of the family music library. Furthermore, although they are not directly linked to the Schubert family, there are also printed arrangements for string quartet of overtures by Antonio Salieri, Schubert’s teacher. 5 These arrangements may explain one of the most unusual of Schubert’s chamber works, an original Overture for String Quintet (D8), his earliest dated chamber composition (June 29, 1811), a piece he also adapted for string quartet (D8A). His model was an orchestral work by Luigi Cherubini, the overture to Faniska. 6 A similar work, an Overture for String Quartet in B flat (D20), was lost after the editors of the old Complete Edition (ASA ) decided not to publish it. 7

There are a number of other indications of the influence of orchestral music in Schubert’s early chamber music for strings. For example, he modeled the finale of his String Quartet in C Major (D32) on the first movement of Haydn’s Symphony No. 78 in C Minor; and there are also relationships between Schubert’s own early orchestral music and his string quartets. 8 This tendency culminates in the String Quartet in D Major (D74) whose slow movement and finale are close enough to be considered a kind of sketch for the parallel movements of his First Symphony (D82), also in D major, completed October 28, 1813, about a month after the Quartet. Furthermore, the form of the first movement of the Quartet in D is that of a majority of opera overtures of the time: a sonata form without a development section or repeat signs after the exposition. Well-known examples that Schubert knew of this form include the overtures to Gluck’s Alceste , Mozart’s Figaro , Beethoven’s Prometheus , and several by Rossini. Not surprisingly, almost all of Schubert’s own overtures use this form. When the recapitulations do not begin in the tonic key (e.g. those by Gluck and Salieri), the structure resembles the older bipartite sonata form, although without the repetition of either part. The bipartite principle is a most important one for Schubert, and explains many of the unusual formal procedures to be found in his larger instrumental works; and not only in the first movements. In addition to formal approach, it is the style of Schubert’s early string writing that shows orchestral influence: excited string tremolos, doublings at the octave; double, triple, and even quadruple stops; as well as melodic ideas that at times suggest orchestral brass (e.g. fanfares). A striking example of the latter occurs in the opening movement of the String Quartet in B flat (D36) which introduces a repeated trumpet-like fanfare at the same structural position, the end of the development section, as the trumpet call in Beethoven’s Leonore Overture No. 3. 9 Interestingly enough, once the First Symphony was completed, subsequent string quartets by Schubert begin to sound less orchestral. But the tendency recurs in his last quartets, especially the D Minor “Death and the Maiden” (D810) and the G Major (D887).

Between November 1813 and the latter part of 1816, that is after Schubert left the City Seminary and returned home, he wrote five string quartets of which four are extant in a completed state (D87 in E flat, Op. 125 No. 1; D112 in B flat, Op.168; D173 in G Minor; and D353 in E Major, Op. 125 No. 2). 10 Undoubtedly also written for the family quartet, each has considerable musical value; but the B flat (D112) is the most beautiful. Perhaps because he began the piece as a string trio, there is a sense of intimacy lacking in most of the earlier quartets. 11

The description of tripartite sonata form (i.e. with exposition, development, and recapitulation) by Carl Czerny, a pupil of Beethoven, is useful in understanding the spacious first-movement forms of Schubert and particularly the Allegro ma non troppo of D112. Czerny’s account divides the form into two parts, the first of which corresponds to the exposition and is in turn subdivided into five sections: (1) “principal subject” (2) “its continuation and amplification, together with a modulation into the nearest related key” (3) “the middle subject [second theme] in this new key” (4) “new continuation of this middle subject” (5) “a final melody [closing theme] closes in the new key in order that the repetition may … follow unconstrainedly.” 12

The implicit alternation of tonally stable sections (1, 3, and 5) and unstable, that is modulatory or at least harmonically more active, passages, (2 and 4) suits well Schubert’s penchant for tonal movement and interesting harmony. In the exposition of D112, first movement, the longest and most important passage corresponds to Czerny’s section 2, for which Schubert writes a new melody from which he derives all his subsequent thematic material. But it is his tonal movement in this passage that is especially noteworthy. Whereas in the music of his predecessors this section is primarily devoted to establishing a new key, often by way of its dominant, Schubert prefers a deliberately round-about approach; and he almost never stresses the new key’s dominant. In this movement, for example, he begins section 2 in G minor (mm. 35ff.), returns to B flat (mm. 72ff.), then moves to E flat (mm. 81ff.), and briefly tonicizes G minor again (mm. 93–95). After sixty measures he is back where he began! He doesn’t establish F major, the key of the middle subject, until two measures before that subject (mm. 101–02).

The analogous passage continuing the middle subject (Czerny’s section 4) is equally exciting but much shorter. It consists of a sequence in three ascending stages, each modulatory (mm. 124–36). Czerny continues his description of first-movement form as follows:

The second part … commences with a development of the principal subject, or of the middle subject, or even of a new idea, passing through several keys, and returning again to the original key. Then follows the principal subject and its amplification, but usually in an abridged shape, so modulating that the middle subject may likewise reappear entire, though in the original key; after which, all that follows the middle subject in the first part, is here repeated in the original key.

When hearing the relatively short development section of D112, the listener may feel that it lacks the excitement of the exposition. In fact, until the time of the “Unfinished” Symphony (D759, fall 1822), Schubert’s greatest problem with sonata form is his inability to construct development sections that can serve as the climax of the movement, as Beethoven’s so often do. In the recapitulation Schubert reveals his priorities clearly, namely his need to retain the tonal variety of his exposition. Often, as here, he increases the length of his principal subject area by introducing new tonal movement (mm. 217–42). This allows the same degree of modulation in sections 2 to 5 of the reprise; and yet the movement will close in satisfying fashion in the tonic key.

To organize the slow movement and finale of the B flat Quartet, for the first time in his career he selects another traditional form: the rondo with its alternation of refrains and episodes. But here too Schubert reveals his predilection for more harmonic motion than his predecessors. During the slow movement, for example, the second of the three refrains is in the key of the dominant rather than the usual tonic. Furthermore, in both movements Schubert prefers a single, lengthy modulating episode that returns, naturally with a different tonal orientation, instead of two or more different episodes. When Mozart or Beethoven, Schubert’s principal models at this time, contrived a return of an episode, invariably the first, it was always after they had presented a second (different) episode; and that return would always be in the tonic key. This portion of the movement would then resemble a recapitulation of a second group in sonata form. As a result the form is often referred to as a sonata-rondo. Schubert’s returning episode, on the other hand, retains the modulatory quality of the original episode, even as it concludes in the tonic. Finally, and again unlike his predecessors, the harmonically adventurous Schubert writes both Scherzo and Trio of D112 in a key other than his tonic. Here it is the subdominant, E flat.

In December of 1820 Schubert wrote the Quartettsatz (“quartet movement”) in C Minor (D703), his only incomplete chamber work regularly performed today. In this regard it resembles his “Unfinished” Symphony, another composition dating from a period in the composer’s career sometimes referred to as his “Years of Crisis” (1818–23). 13 This is an apt description, especially for his larger instrumental works, fewer of which were written at that time than either before or after, and with a far higher percentage of incomplete compositions than at any other stage in his career.

One of the striking features of the Quartettsatz is the greater participation of the cello. This reflects, perhaps, the fact that Schubert was no longer living at home and writing for the family quartet. His father, the cellist, appears to have had modest performing skills. Most importantly, for the first time in his string chamber music Schubert seems to have come to grips with Beethoven’s awesome achievements. This meant instrumental compositions on a large scale with a wide range of emotional states, works which present the composer with the problem of unification. Failure to find a solution for that problem may have contributed to Schubert’s abandoning the fine beginning (41 measures) of a slow movement in A flat major intended to follow the completed Allegro assai. The fragment breaks off as Schubert was modulating back to the tonic from an effective contrasting passage in the distant key of F sharp minor. The editors of the old Complete Edition – and Johannes Brahms was a particularly influential member of that group – compare the quality of the fragment with that of the completed movements of the “Unfinished” Symphony and regret Schubert’s failure to finish the work. 14

The structure of the completed movement has often puzzled commentators who for the most part fail to recognize the young composer’s predilection for bipartite form. In bipartite movements only the thematic ideas heard in the final section of the first part need recur in the tonic key during the latter portion of the movement. And this is the situation in the Quartettsatz. The principal subject returns only in the brief coda; the continuation of that subject never returns; and the soaring middle subject, originally in A flat, is now heard in two keys, B flat and E flat, neither of which is the tonic. Only the unusually extensive closing section, originally in G major, the opposite mode of the dominant and not a usual contrasting area for movements in minor, returns in the tonic, C, but in major. The coda is the only section in the second part that is in C minor, the key in which the movement began.

Two broadly conceived symphonic fragments, the completely sketched but never fully orchestrated Symphony in E of 1821 (D729) and the “Unfinished” Symphony of the following year, suggest Schubert’s increasing preoccupation with Beethoven after the Quartettsatz. But it is only in the winter of 1823–24 that Schubert began to interact on a regular basis with musicians of Beethoven’s circle. Most importantly, he became friendly with the violinist Ignaz Schuppanzigh, leader of the first professional string quartet, and recognized as the most influential and successful proponent of Beethoven’s music in Vienna. Schuppanzigh, who had been absent from the Austrian capital for a number of years, regularly promoted a subscription concert series, and was the leader from the concertmaster’s chair of the orchestra for the first performances of many of Beethoven’s major orchestral works, including the Ninth Symphony. Preparations for that event occasioned a touching letter from Schubert dated March 31, 1824, to his friend Leopold Kupelwieser suggesting how strongly he felt the need to emulate Beethoven:

Of songs I have not written many new ones, but I have tried my hand at several instrumental works, for I wrote two Quartets for violins, viola and violoncello and an Octet, and I want to write another quartet, in fact I intend to pave my way towards grand symphony in that manner. – The latest in Vienna is that Beethoven is to give a concert at which he is to produce his new Symphony, three movements from the new Mass and a new Overture. – God willing, I too am thinking of giving a similar concert next year.

(SDB 339)

Perhaps more than anything else, two aspects of Beethoven’s achievements seemed to preoccupy Schubert in 1824. One of them was cyclic unification, 15 and the other was the older composer’s success with variation form. It can hardly be coincidental that in April 1822 Schubert dedicated his “Variations on a French Song,” Op. 10 (D624), for piano duet to Beethoven with “veneration and admiration,” or that during the year 1824 he composed the largest number of variation sets of any period in his life. These include the weak set on his fine song Trockne Blumen for flute and piano (D802) in E, the same key as his more successful variations on a passage from his song Der Wanderer (D489), the slow section of the Fantasy for Piano in C Major, Op. 15 (D760, November 1822). Also composed in 1824 were the variations for Piano Duet in A flat, Op. 35 (D813), and two sets for chamber works: the Andante from the Octet (D803), which has elements in common with Beethoven’s Septet, Op. 20, as well as the finest set of variations Schubert ever wrote, the slow movement of his String Quartet in D Minor (D810). The Quartet is named for his song Der Tod und das Mädchen (D531), from which the theme of his variations derives. Of his sixteen variation sets, five were written in the year 1824. 16

In an age when variations were popular – Carl Czerny is reputed to have written 500 sets – one might wonder why the usually prolific Schubert did not write more of them. The answer may relate to the tonal and harmonic restrictions inherent in the form. In sets of ten variations or less, normally the variations remain in the same key with one in the opposite mode. Occasionally, as in the Andante from the Octet, there is an additional variation in another key. But even Beethoven, who experimented once with each variation in a different key in his piano set, Op. 34, never did so again, and they are far from his most successful variations. It seems clear that for Schubert the form limited his normally fertile harmonic imagination. It is unfortunate that he never felt free enough to combine groups of variations with other formal approaches, as Beethoven did magnificently in the slow movements of the Fifth and Seventh symphonies.

The three string quartets mentioned in the letter to Kupelwieser (the A Minor, D Minor, and G Major), Schubert’s most impressive contribution to the genre, were originally intended to be published as a set of three, perhaps in emulation of Beethoven’s Op. 59, the Razumovsky Quartets. But Schubert’s third, the G Major (D887), was not written until 1826 and only the first, the A Minor (D804), was actually printed during his lifetime. It appeared in September of 1824 as Op. 29 No. 1, “Trois Quatuors … composés et dediés à son ami Ignaz Schuppanzigh … par François Schubert de Vienne.” The first performance had taken place on March 14 of that year in the subscription series mounted by Schuppanzigh with the violinist leading his quartet. On the same program was Beethoven’s Septet.

As the letter suggests, Schubert must have composed the D Minor Quartet in close proximity to the A Minor, and they have much in common. Both are in minor keys with effective use made of the contrast between minor and major; in addition, both are cyclic, that is the individual movements are linked motivically. 17 There is also a striking similarity in the dependence of both slow movements, as well as the Minuet (D804) and Scherzo (D810), on previously composed compositions by Schubert. The sources of the slow movements are well known: the principal theme of the Andante of the A Minor derives from the section in major of the entr’acte following Act III of his incidental music to Rosamunde (D797). 18

The Minuet was the best-received movement of the A Minor Quartet at the first performance; and it is perhaps the finest, certainly the most poignant, dance movement in Schubert’s larger instrumental works. The arresting beginning in the cello and the transition to the Trio derive from his song Die Götter Griechenlands (“The Gods of Greece,” D677, November 1819) set to a text by Schiller beginning “Schöne Welt, wo bist du?” (“Beautiful world, where are you?”). The striking contrast of A minor and A major, so important for the song, is also crucial for the Minuet and the quartet as a whole; and the tonalities of both song and quartet are the same, A. The key of the song Death and the Maiden , D minor, is also that of the quartet, although the theme is transposed to G minor for the slow movement

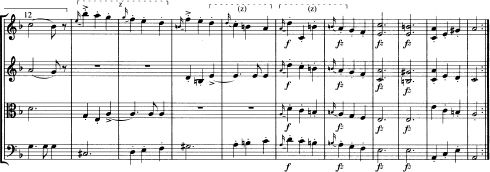

Less well known is the fact that the Scherzo of the D Minor Quartet is derived from a previously composed dance, arguably one of Schubert’s greatest, the G sharp Minor Ländler (D790, 6; May 1823). (It forms part of a splendid set of twelve German dances first edited by Brahms and published as Op. 171 in 1868.) Since the dance is relatively short, to achieve the proportions of a scherzo in a multi-movement composition Schubert expanded the piece considerably. Despite the additions, the substantive relationship will be clear from a comparison of measures 1–6 of the dance and measures 9–14 of the Scherzo (see Ex. 9.1 ). 19

The two figures, marked ‘x’ and ‘y’ on the example of the Scherzo (Ex. 9.1 b), are important throughout the quartet as cyclic elements. The first, a short scale, is already present in the Ländler, but the second, the repeated notes (figure ‘y’), is not. The rhythm of figure ‘y’ is a triple-meter version of the dactylic pattern associated with “Death” in the song. That this rhythm was not present in the dance, but added consistently to the Scherzo and its Trio, is a strong indication that the cyclic element was quite intentional on Schubert’s part.

Schubert wrote once to Leopold von Sonnleithner that a composer cannot always count on finding the right structure for a composition (SDB 265). But he found just such a structure for the slow movement and finale of the A Minor Quartet. It was an unusual type of rondo in which the refrain appears twice rather than the three times considered definitive for the form. Schubert’s structure is A B A C B Coda, in which A is the refrain, B and C are episodes differing from one another, and the coda, taking the place of the final refrain, is derived from refrain material. The young composer appears to have derived this approach, which he subsequently used for other movements as well, from the finale of Mozart’s String Quintet in C Major (K. 515). 20 Schubert knew the work as he had borrowed the Mozart quintets from a friend previously. 21

Example 9.1a and 9.1b

G# Minor Ländler (D790, 6), mm. 1–8

D Minor String Quartet (D810), third movement, mm. 1–22

Schubert wrote the last, and in many ways the most original, of his string quartets, the G Major, in 1826. By this time he is no longer particularly concerned with writing variations, nor does he use short motifs cyclically to relate movements. Instead there is a complex web of connections, some obvious, others less so. The most important of these is modal contrast, the alternation of major and minor on several levels. The first movement begins with a juxtaposition of the tonic (G major) triad with its parallel triad (G minor), an idea he almost immediately repeats on the dominant (mm. 6–10). During the recapitulation (mm. 278ff.) he reverses the procedure; now the minor triad is first. In the quartet’s finale, a quick and extended sonata-rondo in 6/8 meter much like that of the D Minor Quartet, each time the refrain occurs there is a descending tonic minor triad followed by an ascending G major scale. Both the rondo slow movement and the highly imaginative Scherzo, a kind of miniature sonata form, also make important use of modal contrast.

Schubert’s String Quintet in C Major, for string quartet and a second cello (D956, summer or early fall 1828), is generally recognized as one of the finest chamber works of the nineteenth century, a fitting successor to Mozart’s string quintets. One reason for Schubert’s choice of two cellos may have been modesty, to avoid a direct comparison with Mozart who preferred two violas in his quintets. Another, probably stronger, reason was the richer sonorities offered by the cellos.

Spaciousness, a quality also present in the first movement of the G Major Quartet, characterizes the Quintet. The tone is set by the slow moving, even static harmonic progression with which the first movement opens. Unlike Schubert’s normal inclination to initiate a movement with a march-like or even dance-like rhythm, both here and in the opening of the G Major Quartet he presents his harmonies – rather than a memorable, well-contoured melody – without a regular rhythmic pulse. As a result, the Quintet opening contrasts powerfully with the surging rhythmic momentum generated during the continuation of the principal subject. In Beethoven’s conversation books Schubert is reported to have assiduously attended the first performances of all the older master’s late quartets (SDB 536). One of the lessons he seems to have learned was the effectiveness of powerful, sometimes unexpected, contrasts. His own contributions in the Quintet are the rich sonorities, the way he balances the five instruments in varied groups, and the incredible beauty of the modulating middle theme. Particularly noteworthy is the way Schubert constructs the development section in the first movement. He devises an extended sequence consisting of three long, highly modulatory stages, a compositional technique he developed near the end of his career. 22 Shortly before the recapitulation (mm. 262ff.), Schubert introduces an ascending arpeggio in the first violin reminiscent of the principal theme in the first movement of Mozart’s C Major Quintet.

The sublime slow movement, one of Schubert’s relatively few Adagios, is in three parts. The principal theme of the first moves effortlessly and without pause for twenty-eight measures, a tour de force of continuity suggesting music of much later composers. The key is E major, one he likes for elegiac settings, witness the slow movement of the “Unfinished” Symphony. The strong contrast with the second part of the movement, a passionate outburst in F minor, is typical of the Quintet. The tonal relationship of lowered second degree to the tonic of the movement, F minor to E, is important elsewhere in the composition.

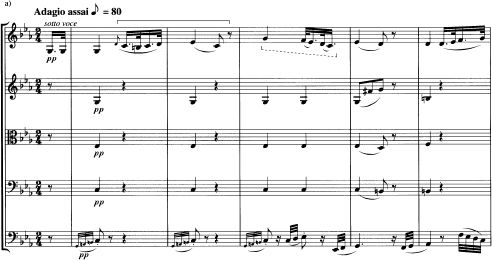

The Scherzo, an expansive movement whose proportions and tonal variety bring it closer to sonata than to dance form, has a Trio which is surely the most unusual Schubert ever wrote. Following Beethoven’s lead in the Trio of the Scherzo in the Ninth Symphony, Schubert abandons the usual triple meter for common time. Furthermore, in place of the extremely rapid Presto – the Scherzo is the quickest movement in the Quintet – he substitutes an Andante sostenuto. There is also a highly unusual key-scheme. This parallels the slow movement whose central portion was also designed to provide maximum contrast. In the Trio, as in the second part of the slow movement, Schubert moves a half step higher, from C to D flat major. To make the relationship with the slow movement even stronger, he begins the Trio with four measures of an unaccompanied melodic line suggesting F minor. The impression of the Trio as a whole is that of a funeral march, not unlike the slow movement of the “Eroica” Symphony with which it shares an important melodic element (see Ex 9.2 ).

The energetic and, for Schubert, relatively concise finale is another sonata-rondo employing the form of the finale of Mozart’s C Major Quintet (A B A C B Coda). It is the only movement in which the tonic minor plays a role as important as that of the tonic major.

23

Schubert’s close, with a sustained trill in the cellos on  recalls the trills and half-step relationship in the slow movement, and especially the D flat Trio where trills were also important. The range of contrasting moods successfully encompassed by Schubert in the quintet as a whole is quite remarkable and ultimately deeply satisfying.

recalls the trills and half-step relationship in the slow movement, and especially the D flat Trio where trills were also important. The range of contrasting moods successfully encompassed by Schubert in the quintet as a whole is quite remarkable and ultimately deeply satisfying.

Schubert’s chamber music with piano

Schubert began to write chamber music with piano relatively late in his career. In 1816, a year in which the influence of Mozart reached its peak, Schubert wrote three short but attractive sonatas for piano “with the accompaniment of the violin,” published posthumously by Diabelli as “Three Sonatinas” (Op. 137). The first of the three, in D Major (D384), owes much to the first movement of Mozart’s E Minor Piano and Violin Sonata (K. 304), especially in the opening and closing sections of the respective expositions. The lovely E major Trio of Mozart’s second movement, a Tempo di Menuetto, must have deeply impressed Schubert, foreshadowing as it does his own tenderest dances.

Example 9.2a and 9.2b

Beethoven, “Eroica” Symphony, Op. 55, second movement, mm. 1–5

String Quintet in C Major (D956), third movement, mm. 1–8

That same year he wrote an Adagio and Rondo Concertante for Piano Quartet (piano, violin, viola, and cello; D487), another work influenced by Mozart. It was composed for a choir director, Heinrich Grob, brother of the soprano Therese Grob toward whom Schubert was romantically inclined for several years. Not especially demanding of the pianist, the piece falls into that category of early chamber works that can be performed with additional string instruments, perhaps even a small orchestra. 24 As is often true of Schubert’s lesser instrumental works, the most interesting passages are to be found in the slow section, the Adagio.

During the year 1818 Schubert wrote his first significant group of four-hand compositions, an activity that left an indelible impression on the scoring for piano of such works as the A Major “Trout” Quintet for piano, violin, viola, cello, and contrabass (D667). One of Schubert’s most popular instrumental compositions, it appears to have been written for a wealthy music patron and amateur cellist, Sylvester Paumgartner, of Steyr in Upper Austria. He is said to have suggested that Schubert include a set of variations on the composer’s song Die Forelle (D550). As no autograph exists, the date of composition is uncertain; but Schubert visited Steyr during the summers of 1819, 1823, and 1825. Otto Erich Deutsch suggested fall 1819, which is supported by three pieces of musical evidence. First, most writers on Schubert’s instrumental music have remarked on the number of sonata-form movements in which the recapitulation begins in the key of the subdominant; but they generally fail to notice that he did so only in works dating from 1814 through 1819. Since the recapitulation of the first movement of the “Trout” Quintet begins in the subdominant, this would seem to rule out the later years of 1823 or 1825. Secondly, Schubert wrote five slightly different versions of the song Die Forelle. The theme of the variation movement in the Quintet most closely resembles the version written in 1818. And, finally, Schubert chooses for the finale of the quintet a bipartite form in which the second part quite literally repeats the first, except for the sequence of keys. In other words, the second part is virtually a transposed version of the first. The second movement, the Andante, is similar but with a somewhat more interesting progression of tonalities. None of Schubert’s larger instrumental movements of the 1820s is written in such a mechanical fashion.

To provide a unifying thread for much of the Quintet, Schubert adopts the sextuplets of the song’s accompaniment and writes related figures in four of the five movements – all but the Scherzo. As in the song, the figure generally has a subordinate function; the piano usually introduces it; and, except for the slow movement, the figure ascends, as in the song. The feature suggesting four-hand writing consists in both hands playing exactly the same notes an octave apart. While passages of this sort occur elsewhere in Schubert’s chamber music for piano, they do so far less often than here.

Schubert completed his two masterpieces for piano, violin, and cello, the Trios in B flat Major, Op. 99 (D898) and E flat Major, Op. 100 (D929), during the last twelve or thirteen months of his life, together with a less effective Adagio for Piano Trio in E flat (D897) called “Notturno” and generally believed to be a discarded slow movement for the B flat Trio. Considering the quality of the two completed trios, it is startling to realize that Schubert’s only prior experience of writing for this instrumental combination was a single weak movement in B flat major written some fifteen years earlier (D28, 1812) and called by the young musician “Sonate.” 25

There is no extant manuscript for the late B flat Trio and, therefore, no firm date of composition. But the untitled and equally undated manuscript of the “Notturno,” its presumed original slow movement, is of the same paper type as that of the E flat Trio whose manuscripts (including a sketch) are dated November 1827. Since Schubert apparently bought this paper sometime after September 24,1827, and used it until April 1828 26 at least three movements of the B flat Trio would seem to have been written within months of the E flat Trio. But, in view of the fact that the new slow movement for Op. 99 is tripartite, a form Schubert used for slow movements of his larger instrumental works primarily at the end of his life, that (replacement?) movement may have been written during the summer or fall of 1828. If so, this might explain the publication of Op. 99 after Op. 100, even though it was given (by Schubert?) an earlier opus number.

Whatever their order of composition, the piano trios have much in common. In both there is the extended four-movement design favored by Beethoven with three movements in the tonic key. 27 Both slow movements begin with cello solos and each is in a key closely related to the tonic of the composition. Both Scherzos are elegantly contrapuntal, although the E flat Scherzo is more obviously so. It begins with a canon lasting twenty-seven measures. Was the model the fugato passages in the Trio of the Scherzo in Beethoven’s “Archduke” Trio, Op. 97? 28 Each Scherzo has a more homophonic Trio in the subdominant. But it is the finales that have the most in common. Each is of considerable length and essentially bipartite in form, despite the title “Rondo” in Op. 99. Both are in duple meter – 2/4 for Op. 99, 6/8 for Op. 100 – with a vital rhythmic shift during the contrasting sections. In the B flat Trio there is a striking displacement as Schubert substitutes 3/2 meter for 2/4 at three points in the movement. In the finale of the E flat Trio the duple compound meter (6/8) gives way to an alla breve which is still duple, but with a simple subdivision of the beat (¢). This occurs at no less than five points in the movement. As the alla breve comes to the fore, there is an increased number of impacts per beat (four in place of three) and, consequently, an increase in excitement that helps propel the music forward.

Although not obviously, Schubert prepares for the repeated notes of the alla breve passage by introducing groups of repeated notes increasingly in his opening section. Initially these occupy subordinate roles; later, however, they assume thematic importance. See the cadence at measures 15–16 and especially the long upbeat to the contrasting idea of the first group treated imitatively (mm. 33–34). The repeated notes, however, not only provide coherence in the finale. They are part of a larger design, one in which all the movements of the trio are unified. Observers always point to the effective return twice of the principal theme of the slow movement in the finale (mm. 273ff. and mm. 693ff.) Unnoticed is the presence of themes – in the Andante con moto it is the introductory chords – with four repeated notes or sonorities in each movement. During the opening Allegro it is the modulating middle subject beginning in B minor (mm. 48ff.), a theme similar to the main idea of the Minuet in Schubert’s G Major Sonata, Op. 78 (D894), also in B minor. In the slow movement it is the march-like chords introducing the main melody, said to be derived from a Swedish folk song. The four repeated notes are built into the canonic theme of the Scherzo as well as the lovely derived subject of the E major section (mm. 30ff.) In the Trio there is a double reference: the repeated quarter notes of the Scherzo are introduced by the original figure from the first movement (¢). This idea is then treated contrapuntally for twelve measures. Since Schubert closes both the first and last movements with the repeated-note figure, it is clear he wanted to emphasize the cyclic element.

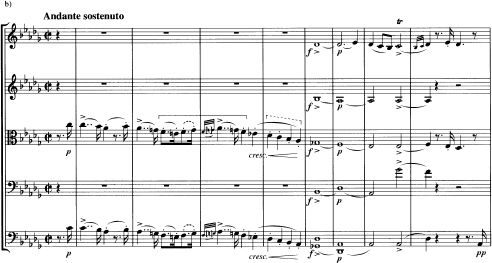

Another relationship exists between the Minuet of the G Major Piano Sonata and, in this case, the B flat Trio. Schubert (subconsciously?) inverted the transition and first measures of the Minuet’s Trio to shape his principal subject of the Scherzo in the B flat Trio (see Ex. 9.3 ).

Schubert’s Octet and closing remarks

Schubert’s Octet in F Major (D803) was completed March 1, 1824, for Ferdinand, Count Troyer, a clarinettist and Chief Steward of Archduke Rudolf, a composer who studied with Beethoven and to whom both the “Archduke” Trio and Schubert’s A Minor Piano Sonata, Op. 42 (D845), were dedicated. Troyer is reported to have asked Schubert to write a composition resembling Beethoven’s Septet.

Schubert fulfilled the commission, and a private performance of the Octet took place that year at the Count’s home. In addition to Troyer, the performers once more included Schuppanzigh as first violinist and most of the players who took part in the premiere of Beethoven’s Septet, in his lifetime the most popular of all his works. 29 The first public performance of the Octet took place on April 16, 1827, again at a concert organized by Schuppanzigh and with most of the same players as in 1824, with the exception of the clarinettist. 30 What may have brought the Septet to Troyer’s attention was the fact that Schuppanzigh had scheduled its performance at the concert of March 14, 1824, together with Schubert’s A Minor Quartet.

Example 9.3a and 9.3b

G Major Sonata, Op. 78 (D894), third movement, mm. 53–58

Piano Trio in B flat, Op. 99 (D898), third movement, mm. 1–8

The correspondences between the Septet and the Octet are considerable. Schubert followed Beethoven’s instrumentation (violin, viola, cello, contrabass, clarinet, bassoon, and horn) with the addition of a second violin. In the tradition of outdoor music suggested by the presence of three wind instruments, there are six rather than four movements, and for the most part a cheerful, relaxed mood. Beethoven wrote a Scherzo and a Minuet; and so did Schubert, except that he reversed their order. The older composer wrote a theme and variations in the key of the dominant and in duple meter as his fourth movement; and so did the younger. Although Schubert did not choose Beethoven’s principal key, E flat major – he chose F major instead 31 – Schubert did follow closely the relationships of the individual movements to the respective principal keys. The only exceptions are the Trios to Scherzo and Minuet which Beethoven retained in the tonic; Schubert did not. Beethoven composed slow introductions to both quick movements (i.e. the first and last) and so did Schubert. Furthermore the lengths of those introductions are almost identical. Both Adagio movements begin softly with a clarinet solo and are in a compound meter. And, finally, the composer of each finale interrupts the flow of his movement at exactly the same point, the joint between development section and recapitulation. Beethoven introduces a cadenza at measure 135; Schubert reintroduces a portion of his slow introduction at measure 370.

Most of this information is common knowledge. Less often remarked is the cyclic element that Schubert introduced into each of his movements, a short dotted figure dominating the first movement. As in the D Minor Quartet, also written in early 1824, there are both rhythmic and melodic elements at play. In addition to dotted or double-dotted patterns, sometimes accentuated by an additional short upbeat, there is also melodic motion by step in either direction. Once the step-wise motion has been established, however, Schubert allows himself leeway; he stretches the interval, sometimes as much as an octave. Again as in the D Minor Quartet, the direction of the melodic component may vary. As with most motifs, it is the rhythmic aspect that is least mutable. Schubert may have received the stimulus for the rhythmic component and repeated pitches of his cyclic figure from the double-dotted repeated notes in the introduction to the last movement of Beethoven’s Septet.

The cyclic motif has been traced throughout the Octet elsewhere 32 and I need only mention here the source of the theme Schubert adapted for his variation set: a duet, “Gelagert unterm hellen Dach,” from the second act of his Singspiel, Die Freunde von Salamanka (D326, 1815). At several points Schubert introduces the cyclic figure into the instrumental version of the melody, a strong indication of his cyclic intent.

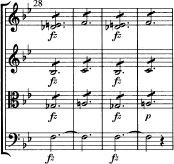

Before concluding, I should like to discuss briefly the musical factor that most impressed – in some cases disturbed – his contemporaries: Schubert’s imaginative harmony. His propensity for rich, often dissonant sonorities and the frequency of unexpected harmonic progressions or tonal sequences is audible in his very first compositions. During the finale of the String Quartet in Mixed Keys (D18, 1810 or 1811), probably his earliest extant chamber work, the young musician increases the dissonant force of an already dissonant augmented-sixth chord by simultaneously sustaining its tone of resolution in the cello. To highlight this unusual sonority, Schubert calls for a forzando , writes the three upper strings in what amounts to an excited string tremolo (repeated sixteenth notes at a presto tempo), and then repeats the progression immediately (see Ex. 9.4 ).

In his earliest works Schubert’s harmonic exploits are not always convincing. But they are later. The exposition of the first movement in his last string quartet, the G Major, provides a stunning example of Schubert’s modulatory imagination and control. As noted earlier, the contrasting and juxtaposition of tonic major and minor is crucial for the entire composition. During the exposition of the first movement, Schubert takes advantage of the fact that his first group (principal subject) contains passages in both tonic major and minor to compose a remarkable modulatory contrasting region. The passage (middle subject) begins with D major, the expected dominant of G major. But Schubert then uses the importance of the tonic minor to introduce two additional tonal areas, the dominant and relative of G minor (D minor at m. 104 and B flat major at m. 110). Since the passages in D major and B flat major also tonicize momentarily other scale degrees, the effect is tonally kaleidoscopic. The closing section includes scales of D melodic minor (i.e. with lowered sixth and seventh degrees) alternating with a syncopated thematic idea in D major derived from the middle subject. The exposition and a slightly abbreviated recapitulation are, from the tonal point of view, incredibly rich; but they are also thoroughly convincing. The point to be made from this admittedly extreme instance is that in Schubert’s extended forms modulation provides more than a path to, or a preparation for, the next tonally stable passage. But if there is so much tonal movement in the expositions and recapitulations of his sonata-form movements, what can Schubert do in his development sections? For some possible answers we might return briefly to the first movements of his piano trios.

Example 9.4 String Quartet in Mixed Keys (D18), fourth movement, mm. 28–31

At the end of the development section of the first movement of the B flat Trio, there is an oft-remarked and quite startling turn to G flat major (m. 187). It is startling because there were twenty-six measures of dominant preparation for B flat (the expected tonic) comprising the end of the development section (mm. 160–85). To be sure, earlier in the movement Schubert wrote a low G$$ trill at the cadence of the principal subject (m. 9). 33 He also introduced, more thematically, bass G$$’s in his closing section (mm. 101, 105, and 109), as well as similar bass G$$’s during the dominant preparation just mentioned (mm. 176 and 180). Ornamental elaborations of F, either as dominant or temporary tonic, they only partially prepare the ear for a recapitulation on G flat. I believe Schubert wants us to hear the event as a surprising one, a momentary tonal obfuscation, clarified almost immediately by a modulation to the expected key at the continuation of the principal subject (m. 211).

This and other late recapitulations in keys other than the tonic (e.g. in the finale of the “Great” C Major Symphony [D944]) differ considerably from the dominant and subdominant recapitulations of Schubert’s earlier years. Those keys were usually prepared; they emerge naturally from their (generally shorter) development sections; and the overall effect is often of a bipartite rather than tripartite sonata form. Two aspects are of importance: the length and relative significance of the development section, and the impact at the point of recapitulation. As suggested earlier, it is only from the time of the “Unfinished” Symphony and its first movement that Schubert is able to handle extended developments. One of the ways he does so, and I think successfully, is with sequences, each of whose stages is of substantial length and modulates (i.e. within the stage itself). We saw an example in the String Quintet’s first movement. There is an equally extended sequence forming the body of the development section of the first movement of the E flat Piano Trio. 34 This is a single extremely long sequence with three stages (cf. mm. 195–246, mm. 247–98, and mm. 299ff.) More often, Schubert writes several shorter sequences, as in the first-movement development sections of the last three string quartets.

Did Schubert find this particular approach to organizing development sections on his own? Perhaps. But there is a model, and he could hardly avoid knowing it. The composer? Not much of a riddle. The piece? The first movement of the “Pastoral” Symphony.