11 Schubert’s religious and choral music: toward a statement of faith

They also wondered greatly at my piety, which I expressed in a hymn to the Holy Virgin and which, it appears, grips every soul and turns it to devotion. I think this is due to the fact that I have never forced devotion in myself and never compose hymns or prayers of that kind unless it overcomes me unawares; but then it is usually the right and true devotion.

Schubert, in a letter to his family (July 1825; SDB 434–35 ) 1

Not you, I know well enough, but you will believe …

Ferdinand Walcher, in a letter to Schubert (January, 1827; SDB 597).

Although Schubert bitterly opposed the institution and dogma of the Catholic Church, in his short career he composed six complete Latin Masses, a German Mass, and numerous single Mass movements and other liturgical genres. Two large-scale non-liturgical pieces, a German-language Stabat mater (D383) and an unfinished oratorio, Lazarus, oder: Die Feier der Auferstehung (D689), as well as solo and choral settings of non-liturgical texts on Christian and pantheistic themes, express his devout belief in a divine presence unencumbered by confessional dogma. His setting of the Hebrew text of Psalm 92 (D953) for the Jewish community in Vienna indicates both his religious tolerance and Jewish efforts to integrate (or perhaps assimilate) into the general culture.

The Catholic liturgical music was composed for a society characterized as much by lack of faith as by continuing reverence for the public ceremonies of the Church. 2 The Mass retained its status as a preeminent musical genre, while oratorical works were highlights of Advent, Lent, and Holy Week. Regardless of his religious orientation, Schubert, like any Viennese composer in his day (but not long thereafter), was virtually compelled to compose religious music. Moreover, before he was sufficiently mature to form opinions about established religion, the choir boy Schubert received an introduction to the heritage of Catholic religious music, which he venerated, if only for its musical richness.

Scholarship on Schubert’s religious music has focused on the six Masses, which are usually discussed as an early group of four composed between 1814 and 1816, and the single Masses composed in 1819–23 and 1828 that reflect Schubert’s first maturity and final mastery. 3 In almost all of the literature on the Masses, the new style of the late Masses has been interpreted as the product of a conscious attempt by Schubert to distance himself from religious orthodoxy. The emphasis on the Masses has produced an unfair neglect of the Stabat mater and, to a lesser extent, Lazarus , which were composed in the years between the first four Masses and the last two. These works are highly significant: they were his free choice; they are not explicitly Catholic; their styles are remarkable for their time and place; their composition helped Schubert achieve the technical maturity that enriches the last two Masses; and they are the first large religious pieces in which Schubert consistently attempted to transcend convention in the expression of text. The late Masses may be better understood as the product of a heightened concern about text-musical relationships, as well as the refinement of his overall style, than as a denial of orthodoxy.

The early Masses

Two principal questions have motivated the research about the Masses: (1) how they adhere to and depart from Viennese traditions regarding form and style, and (2) the meaning of text Schubert omitted – in particular the significant phrase in the Credo, “Et unam sanctam catholicam et apostolicam ecclesiam” – in all the Masses. 4 For some scholars these questions have converged, because the increasing freedom from convention in the fourth and fifth Masses has been linked to the heretic’s voice speaking through text that remains unsung. 5 Ultimately, the question is of greater relevance for Schubert’s biographers and for church musicians concerned about the unsuitability of the Masses for liturgical performance. (In Schubert’s life they were performed in church services, and, as Ronald Stringham notes, several posthumous attempts to make them liturgically correct necessitated considerable revisions of the music. 6 )

The absence of small portions of text throughout the Masses has little import for the evaluation of the Masses as works of art; far more significant is the notion of a unified Austro-Viennese church style, often associated with the preferences of the Imperial Court, to which successful Mass composers had to conform. Hans Jaskulsky questions this view, and on the basis of stylistic comparisons identifies numerous traditional strands from which Schubert drew. 7 These encompass general styles according to Mass genre (Missa brevis, Missa longa, Missa solemnis ), as well as formal conventions that cut across the various genres, for example sonata-form Kyries, sectionalization practices and fugues in the Gloria and Credo, 8 prescriptions about length and against operatic tendencies, 9 and the personal styles of favored composers – Joseph and Michael Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven. Certainly Schubert knew their Masses; there is, however, documentary evidence for only one performance that he conducted, Joseph Haydn’s Nelson Mass on Easter Sunday 1820.

The first four Masses reflect Schubert’s engagement with Mass conventions and stylistic debts within and external to the Mass repertory, but also contain some foreshadowings of his mature style. His first complete Mass, the Missa solemnis in F (D105) was performed in October 1814 for the centennial celebration of the dedication of the Schubert family’s church in Lichtental, where Michael Holzer, his former teacher of voice, organ and figured bass, was the choir director. 10 (It is generally assumed that the Masses 2–4 [1815 and 1816], were also written for Holzer.) The Mass in F is competently executed but shows little originality in its design or style. Apart from the fugue at the end of the Gloria, choral homophony prevails. The solo parts are simple and non-virtuosic, although the high tessitura of the soprano part was evidently designed to showcase the soloist, Therese Grob. 11

The large orchestra usually only accompanies – there is no attempt to imitate the symphonic style of Mozart’s and Haydn’s mature Mass writing. The influence of Mozart is, however, unmistakable in the setting of the “suscipe deprecationem nostram” from the Gloria, in which the minor harmonies, low registration and orchestration, notably the trombone parts, are reminiscent of both the second-act finale of Don Giovanni and sections of the Requiem. A post-Classical orchestral style is sometimes evident, as in the fanfares at the end of the first part of the Gloria, and in the prevalent lyrical woodwind part writing. Suggestions of Schubert’s mature harmonic style appear in the occasional melodic and harmonic chromaticisms, the enrichment of the harmonic language through the integration of subsidiary diatonic harmonies, and the juxtaposition of major and minor chords on the same scale degree. While Schubert never violates the meaning of the text, with few exceptions (e.g. the “suscipe deprecationem”), he strikes a neutral and formal attitude toward it; aside from certain requisite brilliant passages such as the beginning of the Gloria the underlying affect is one of pastoral quiescence, a character common to much post-Classical Austrian church music. 12

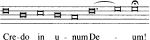

The Masses 2–4, Missa brevis Masses which were performed shortly after being composed, are primarily distinguished by their simplicity and modest technical demands. Choral homophony and non-virtuosic solo writing again prevail, the harmonic language does not significantly change, and concerns for textual expression are no more frequent than in the Mass in F. As in the first Mass, some of the solo parts (and their accompaniments) display a decidedly song-like character. Jaskulsky asserts a cyclical unity in Mass No. 2 in G, based on recurring harmonic progressions and a diatonic ascending linear melody that is later inverted and in the Sanctus chromaticized in the nature of a Baroque lament bass line. 13 The beginning of the Credo makes a clear reference to the prisoners’ chorus from Fidelio (see Ex. 11.1 ). Once again Schubert turns to the world of opera in his search for expressive depth, and his reference implies an identification with Fidelio ideology just as the Austrian restoration began to assert itself. 14

Example 11.1 Mass No. 2 in G Major (D167), Credo, mm. 1–7

In Mass No. 3 in B flat (D324, 1815) a short canonic treatment of “cum sancto spiritu” replaces the more conventional fugue. The contrapuntal challenge is not of the highest order, but the passage demonstrates his interest in archaic styles years before his contrapuntal studies with the noted theorist Simon Sechter in 1828. This Mass has a larger orchestral apparatus than in the original instrumentation of Masses 2 and 4, and also includes more independent orchestral writing than any of the other early Masses. These features, as well as numerous musical details, have been attributed to Schubert’s admiration for the Nelson Mass. 15

Mass No. 4 in C (D452, 1816) was originally scored for chorus, soloists, and only two violins and a figured basso continuo part. 16 Its retrospective style, the so-called “Salzburger Kirchentrio,” has led it to be dismissed as insignificant, but it may be understood in light of its musical references to Mozart’s Missae brevii in the same scoring and verbal ones to Mozart in Schubert’s diary during its composition. 17

Pantheistic and Protestant impulses

Schubert stopped writing Masses for three years after 1816, perhaps because, when he failed to secure the position of music director in Laibach, he turned away from the kind of music that was required for such a job. In this period his interest in religious music shifted to non-Catholic texts and genres, a change that had already begun in 1815 with the setting for vocal quartet and piano of the Schiller text, Hymne an den Unendlichen (D232), and in 1816 intensified with the composition of the German Stabat mater , and two companion pieces to D232, Gott im Ungewitter (D985) and Gott der Weltschöpfer (D986). 18 Although Alfred Einstein finds the “musical and spiritual starting-point” of the three short choral pieces in Beethoven’s solo setting of Gellert’s text, “Die Ehre Gottes aus der Natur” (Op. 48 No. 4, before 1802), 19 their pantheism – the location and musical representation of a divinity in the sublimity of nature – owes as much to Haydn’s oratorios The Creation and The Seasons. Despite their limited means, these works, along with the masterful settings of Goethe’s Gesang der Geister über den Wassern (D538, for unaccompanied vocal quartet, in 1817; and D714, for eight male voice and strings, in 1821) bring an elevated, devotional element to the underlying Biedermeier nature of social (gesellig ) secular choral music.

The depth of these compositions is also felt in the major religious works of this time, the German Stabat mater (1816, text by Friedrich Gottlieb Klopstock), and Lazarus (1820, text by August Hermann Niemeyer), of which Schubert completed the first and most of the second of the three acts. 20 For these works Schubert chose closely related Christian topics on texts written by mid-eighteenth-century north-German Protestant authors associated with the Empfindsamkeit movement. Both texts are replete with sentimental meditations on death and salvation and effusions of familial love. The highly personal emotionality of the poetry suited nineteenth-century tendencies toward an aestheticizing Gefühlsreligion and perhaps appealed to Schubert’s Romanticism. Both texts, however, contain ideas and language surely antiquated when Schubert set them. Their stories are particularly appropriate for Lent and Holy Week, and the season of their composition suggests that they were so conceived, although neither work was performed during Schubert’s lifetime.

Stabat mater

Klopstock heavily reworked the poetic content and form of the original Latin sequence; in setting up the movements, Schubert respected Klopstock’s transformation of the regular tercets of the sequence into free strophes of unequal length, but he omitted the last two quatrains entirely. The work falls into two large parts (movements 1–7 and 8–12), each crowned by a rigorous fugue with colla parte orchestral parts. This strategy is modeled on Pergolesi’s popular Latin Stabat mater (1736), in which imitative duets in an archaic style occur at analogous places. 21 The lively fugues stand in sharp distinction to the prevailing lyricism of the arias, ensembles, and choruses. (There is no recitative.) Despite their uniformly slow or moderate tempos, these movements contain enough variety of styles, textures, and, especially, instrumentation to sustain interest. The orchestra is large, but most movements feature only several of the wind instruments, which are given sensitively crafted obbligato roles alone or in ensemble. The chamber-music quality of the orchestration contributes greatly to the contemplative nature of the work, represents a great advance in Schubert’s orchestral technique, and, in its Romantic coloring, is very beautiful.

Within the general lyricism two contrasting characters emerge. In the elegiac first part, four of the six movements before the fugue discuss the pathos of the crucifixion. They all have minor keys (the fifth movement concludes in the major mode, see below) in which chromatic dissonances and Baroque figures such as seufzer motifs recall Pergolesi’s setting as well as an equally popular Stabat mater composed by Haydn in 1767 that had been reorchestrated and published a decade earlier. (Another familiar composition by J. Haydn for the Lenten Season, Die Sieben Wörter der Erlöser am Kreuze , contains similar material.)

Apart from the eighth movement, whose harmonies gravitate between E minor and the concluding G major, and whose poetic character recalls that of the minor-mode movements in the first part, the entire second part and third and fourth movements in the first concern maternal and filial love and the joys of salvation and paradise. These tender movements are given major keys and breathe Romantic air. The conclusion of the fifth movement, on text about the anticipation of heaven, establishes with the aid of solo horns a serene pastoral quality reminiscent of secular choral music.

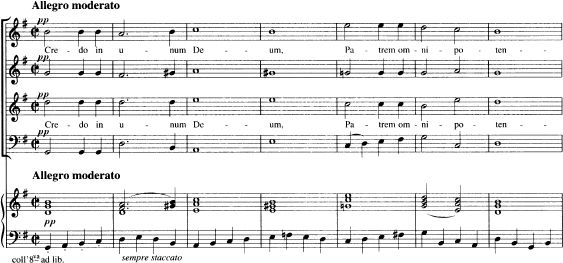

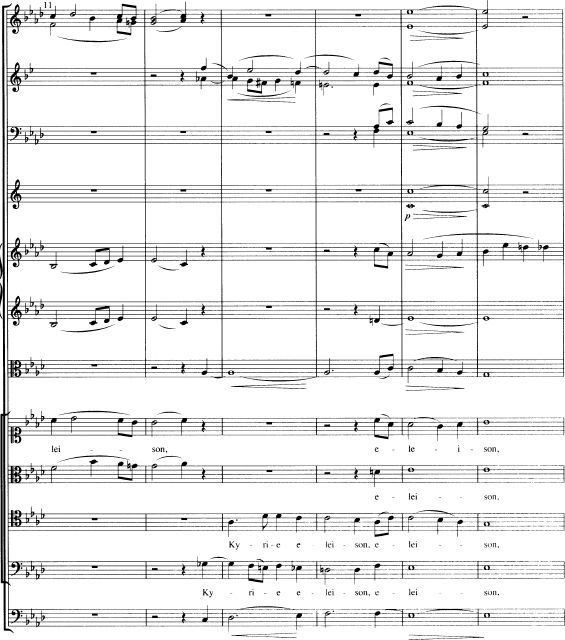

In the tenor aria, No. 6, “Ach, was hätten wir empfunden,” the most deeply felt and stylistically interesting movement in the work, Schubert recreated the style of one of J. S. Bach’s preferred aria textures, the triosonata, and captured the affective world of Baroque pathos (see Ex. 11.2 ).

The bass line is “realized” in the homophonic upper string parts, and the obbligato oboe part (a favorite Baroque choice for pathetic music) serves as a quasi-ritornello that is paraphrased in the first vocal entrance, and, as in Bach’s arias, maintains its melodic independence when the voice part is active. Short phrases are interspersed with rests in both upper parts; in the oboe, Fortspinnung technique is applied to the gradual lengthening of phrase following the short motivic statements at the beginning. Over a pedal bass (mm. 1–3 and periodically thereafter) harmonies change and dissonances arise through the voice leading in the string parts. 22 The highly compressed ABA form also harks back to Baroque models, but the B section ends in C minor (the key of A ) rather than in its own tonic because the return of A coincides with the close of B. After the vocal part concludes in C minor, a final ritornello-like section moves to G major, the dominant of the C major fugue that follows.

Example 11.2 Stabat mater (D383), No. 6 mm. 1–10

A listener should not confuse this movement with an actual Baroque composition: there is no keyboard continuo part and in the B section the melodic and harmonic language reveals its nineteenth-century origins. Yet Schubert’s debts to Bach are unmistakable, and his decision to imitate his style is all the more remarkable, because, although Handel’s oratorios were heard in Schubert’s Vienna, only a handful of professional musicians and amateurs with historical interests knew any of Bach’s liturgical music. 23 Although aria movements 2 and 8 also have bass lines that move like true continuo parts, the vocal parts and the instrumental upper voices do not imitate Baroque idioms. Moreover, despite the undeniable Handelian character of portions (notably the beginning) of the cantata for chorus and piano, Mirjams Siegesgesang (D942, composed in 1828 on a Grillparzer text), there is no other example of such pervasive historicism in all of Schubert’s religious music. Hence, we might best understand this composition, which preceded by a decade the north-German revival of the St. Matthew Passion , as a unique (and very pure) manifestation of his veneration for Bach’s music, independent of a local performance tradition of Holy Week pieces or, as with Handel, popular acceptance of a foreign one.

One other aspect of the Stabat mater must intrigue the historically informed listener. In the autograph score of the third chorus, Schubert entered and then crossed out an exact citation of the last phrase of Haydn’s patriotic hymn “Gott erhalte, Franz den Kaiser.” Yet he substituted a close paraphrase (see Ex. 11.3 ), while several other movements include paraphrases of the hymn or material that can be readily associated with it.

Schubert surely intended some metaphorical comment with the references, but, lacking any extramusical evidence, we can only speculate about its meaning. Was Schubert trying to win favor with the court? 24 Or is Austria under the restoration being mourned? This view would interpret the references as a negative counterpart to the Fidelio citation in Mass No. 2. The last (and rather oblique) reference occurs in the subject of the final fugue, which paraphrases the descent from the sixth scale degree in the second phrase of Haydn’s hymn. In the hymn the phrase ends on the fifth scale degree, but the fugue subject closes on B$$, the leading tone of the dominant of F and, in an awkward imitation of a Handelian–Haydnesque technique, is disproportionately sustained for an entire measure. Could Schubert, who had already written some competent fugues, in good faith compose a fugue subject that concludes as ungracefully as this one? Is the Empire being mocked? Such interpretations require a hermeneutic leap of faith; they cannot be proved, but they are tantalizing to entertain, and Schubert’s cynicism about Austrian politics is historical fact.

Example 11.3 Staber mater (D383), No. 3 mm. 1–12

Lazarus

In the foreword to the first edition of the text of Lazarus (Leipzig, 1778) Niemeyer, a theologian in the Pietistic center of Halle, develops a theory of religious drama that emphasizes the expression of sentiment about the events of the story, rather than their depiction or the portrayal of characters. In a drama of this sort – and Niemeyer’s text naturally exemplifies the theory – the lyric mode predominates while the dramatic and epic modes recede. Thus in Lazarus there is no narrator’s role, although these were conventional even in non-liturgical German oratorios in the eighteenth century, and, despite his importance, Christ does not appear. He is evoked, and the miracle of Lazarus’s resurrection is related by the friends and family who comfort Lazarus, bury him and rejoice at his resurrection.

Despite Niemeyer’s theory, his text is dramatically realistic: rather than allowing characters to speak recitative-and-aria monologues as if they were alone, Niemeyer often has them express their feelings to each other in short, open-ended prose statements. When characters sing arias, they usually sing them to other characters. This dramatic technique, and the contemplative Pietistic themes of familial love and communal religious feeling which it reinforces, motivated Schubert to compose in a style comparable to his opera Alfonso und Estrella (D732, 1821–22) but otherwise without precedent or contemporary counterpart in oratorio or opera. Particularly in the first act, the virtually seamless integration of lyrical accompanied recitative, arioso, and aria anticipates Wagner’s musical dramaturgy in Tannhäuser, Lohengrin and even Parsifal , including the use of quasi-leitmotivic techniques in the orchestra, and also resembles Wagner’s music for the expression of transcendental ideas. 25

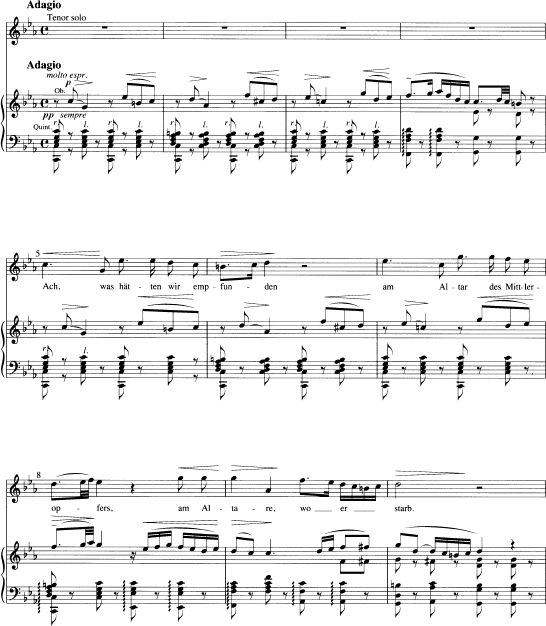

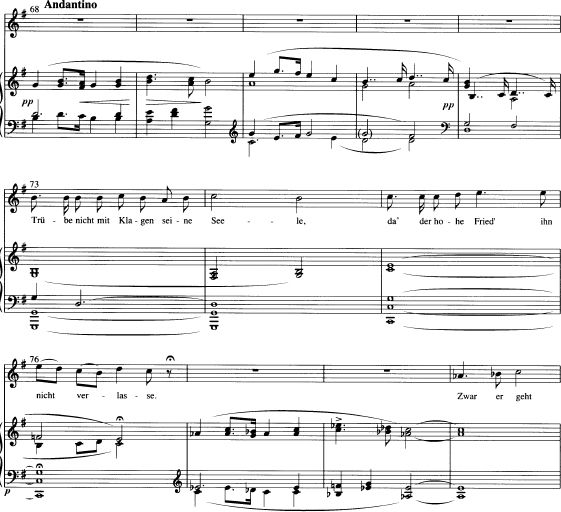

Example 11.4 Lazarus (D689), mm. 68–92

We can appreciate the subtlety of Schubert’s work, including its harmonic dimension, by considering a passage at the beginning of Act I sung by Maria, Lazarus’s sister, as she and her sister Martha attend to him in the garden of his house (see Ex.11.4 ).

Maria first speaks to Martha, but then she pauses for two measures before saying (in translation): “I fall silent before the wise council, kneel in dust and pray to the sublime one.” Maria perceives and responds to a textually undefined divine communication represented by the instrumental music of measures 83–84, which develops and transforms a two-measure motif that unifies the entire section. It is introduced at the beginning of this section (mm. 68–69) in the upper voices and is fully harmonized; it is first stated in G major, then moves to A flat major. In measures 83–84 the motif consists of a recombination of the rhythm of the original first measure (the note values are doubled) and the descending thirds of both measures of the opening motif. Unaccompanied unison cellos and basses imply D flat minor in the lower register. The motivic concentration, and the changes in mode, register, and instrumentation, effectively evoke the gravity of the divine presence and “paint” the image of Maria kneeling in prayer. The transformation prepares the reascent into the upper register and the move to a resplendent D flat major for the word “Hocherhabenen” (mm. 89–91).

This and similar passages represent the most advanced style in the piece; the arias are more conventional with respect to their overall form, yet exhibit a similar fluidity in the text-motivated synthesis of lyrical and declamatory vocal writing that also anticipates Wagner. For a religious work, the music is strikingly secular. There is no oratorio-style secco recitative, and the arias lack the Baroque idioms that Schubert employed so effectively in the Stabat mater. The text of the third act contains a fair number of choruses (there is only one each in the first two acts), giving rise to the speculation that Schubert might have evoked religious genres such as chorales and fugues or imitated styles such as Handel’s or Haydn’s. But the libretto contains no chorales per se and the texts are too long for fugal setting. Moreover, references to oratorio styles would have clashed with the pervasive Romanticism of the music for solo voices and the choruses that Schubert did complete.

As in the Stabat mater , the orchestration contributes greatly to the pastoral mood of much of the music, which was occasioned by the specification in the text (unusual in an oratorio) of outdoor locales for all the dramatic action. The French horns and clarinets of the chorus “Sanft und still schläft unser Freund,” sung while Lazarus’s corpse is carried into a forest cemetery, enhance the voice parts reminiscent of a Romantic secular genre of choral songs on natural themes. The only readily identifiable religious element in the work depends on an instrumental technique, the use of unaccompanied trombones, which harks back to an older Austro-Italian tradition, the “Aequale,” of trombone playing over an open grave. This reference reinforces the possibility of a performance during Holy Week, which in Austria had long featured the performance of “sepolcri,” oratorios which often featured themes of death and graveyard scenes. 26

Lazarus was first performed on Easter Sunday in 1830, but certainly in part due to its fragmentary nature remained obscure for decades thereafter. A Vienna performance in 1863 attracted positive response – Brahms copied parts of the first act and praised it in letters to Adolf Schubring and Joseph Joachim; a piano-vocal score appeared in the 1860s and the full score in the first complete edition. Its incomplete state represents a significant loss, but, even as a fragment, it is a masterpiece that deserves performance and critical recognition.

The late Masses

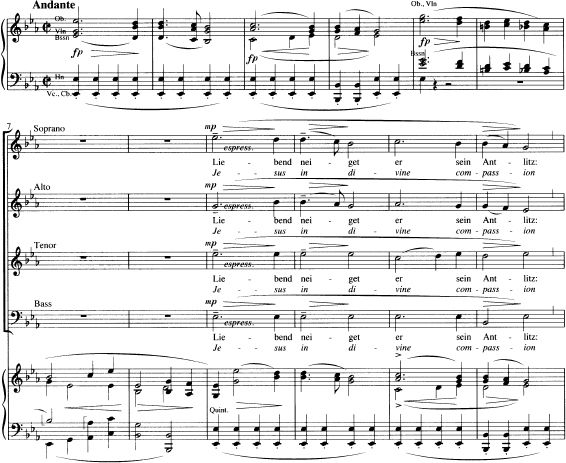

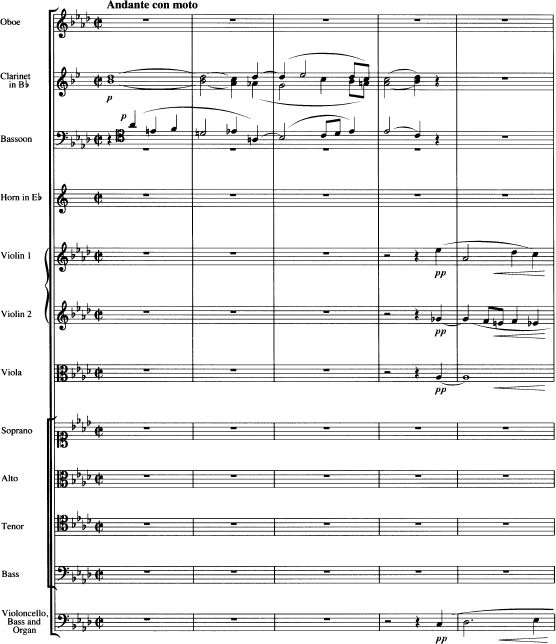

How naïve Schubert was to attach his final, vain hopes of an appointment at the Imperial Court to Mass No. 5 in A Flat (D678), a Missa solemnis composed over the years 1819–22. For this purpose, it is much too subjective and passionately religious, thus rivaling – though utterly different in its modes of expression – and representing an artistic effort uncannily similar to the great work composed contemporaneously, Beethoven’s Missa solemnis. Yet Schubert felt that the work was “successful” and considered dedicating it to the imperial couple (SDB 248); Schubert’s brother Ferdinand, however, was dissatisfied with the first performance, at which he conducted a predominantly amateur ensemble in late 1822 or early 1823. The comparative restraint of Mass No. 6 in E flat (D950, 1828), which was composed for Schubert’s friend Michael Leitermayer, the choral director at the Alservorstädter Pfarrkirche in suburban Vienna, might have better qualified it for job-searching, but Schubert began to compose this Mass immediately after Josef Eybler, in 1827, denied Schubert’s petition for a court performance of Mass No. 5 and thus blocked his application for the position of Vizekapellmeister. This incident dashed his last hopes for a significant post, but also demonstrates his commitment to the genre independent of any professional considerations. Mass No. 6 was the only Mass not to be performed during Schubert’s lifetime. Ferdinand Schubert conducted its first performance in 1829. A review in the Wiener Theaterzeitung of October 22, 1829, noted its positive reception and praised its grandeur while discussing its technical difficulties, notably the vocal parts; a second Vienna performance in November 1829 moved a critic for the Leipzig Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung to criticize its length, its “dark style,” which made it too much like a requiem, and its poor orchestration. 27 Although their lyricism still outshines their occasional monumentality, Schubert’s late Masses are on a significantly larger scale than his earlier ones. They are symphonically conceived and display the fine instrumental solo and chamber writing first heard in the Stabat mater and Lazarus. The orchestration and the motivic work in the introduction to the Kyrie of Mass No. 5 imbues the pastoral tone with a new richness that ushers the listener into a world of religious sentiment hitherto absent from the Masses (see Ex. 11.5 ).

Compared to the earlier Masses, the solo vocal parts, which often retain a Lied character, are more thoroughly embedded in the symphonic texture; the solo ensembles and non-fugal choruses are more often polyphonic, and the textures, including double choruses and a cappella passages, are more differentiated with respect to voice groupings and register. All the vocal parts profit from the new expressive depth of the harmonic language, which is perhaps most immediately evident in the third-related keys that connect many sections of the Mass No. 5 and dramatize shifts in the text content. (See especially the moves from A flat in the Kyrie to E in the Gloria and F in the Sanctus to A flat in the Benedictus.)

Example 11.5 Mass No. 5 in A flat (D678), Kyrie, mm. 1–16

The decisive difference between these Masses and the first four lies in the most basic compositional challenge: taking a musically interpretive stance to the words. Now, finally, Schubert sometimes endeavored to add meaning to the text by applying both the general technical advances that mark his mature style as well as the specific experience gained in composing the early Masses and the intervening dramatic music, both religious and secular. In view of the central problem of textual omissions, the most interesting instances may be found in passages that contain such liberties. Jaskulsky has persuasively argued that many of the omissions, conflations, and repetitions of text in all the Masses served formal ends – Schubert departed from sanctioned practice in order to shape movements or sections to his musical liking. The ritornello-like repetitions of the beginning of the Credo of Mass No. 5 are a well-known example of this technique, but, in view of its musical flaccidity, one which has been correctly viewed as detrimental to textual expression.

Several times in the late Masses Schubert repeated or deleted text in order to deepen expression or emphasize a particular aspect of meaning. One of the most discussed passages in Schubert’s Masses, the “Et incarnatus est” in the Credo of Mass No. 5, has been celebrated for its archaic eight-voice part writing, Grave 3/2 meter and colla parte wind accompaniment. 28 Yet it is the repetition of the sentence that allows the varied second statement to intensify registerally and harmonically the already mystical character of the first one.

In the “Domine Deus” of the Gloria of Mass No. 6, Schubert created a miniature apocalyptic drama based on the opposition of two phrases built on only three lines of the entire text (given below as A and B in capital letters):

Domine Deus, Rex coelestis! Deus Pater omnipotens! A DOMINE DEUS! AGNUS DEI! FILIUS PATRIS! QUI TOLLIS PECCATA MUNDI! B MISERERE NOBIS; suscipe deprecationem nostram. Qui sedes ad desteram Patris, miserere nobis.

The focus of the complete text is on the praise of God with which the Gloria begins. Schubert’s text selection, but even more so his setting, shift the focus away from God onto man’s fear of damnation (A ) and hope for salvation (B): the pair of phrases is stated four times in a varied sequence – phrase A in the minor mode, fortissimo , declamatory vocal lines with an accompaniment featuring trombones and lower strings comparable to accompanied recitative; phrase B in the major mode, pianissimo , hymn-like, virtually unaccompanied. The four statements make a tonal arch in G: G–C–D–G, but the passage makes compellingly clear that form serves textual interpretation and expression. The master of Lied and religious drama has come to terms with the Catholic liturgy by writing personal, subjective music for those parts of the text that spoke to his own religious convictions.