16 Franz Schubert’s music in performance: a brief history of people, events, and issues

The history of music in performance relies on a variety of resources: studies in the evolution of instruments, ensembles, and voices; the evidence of autographs, editions, proofs, marginalia, parts, books, diaries, and letters; tutors and related writings by teachers and performers over the years; and the documentation of concert life in programs and reviews. And since the 1890s, modern performance history has been revealed through a massive archive of recordings.

Schubert research, however, is somewhat disadvantaged in all of these areas except the last. Although we know much about the instruments and ensembles of his day, that information is not specific to Schubert. And of the hundreds of performance tutors published during or since Schubert’s time (and now seldom read), few even mention his name. 1 Until the first critical edition (ASA ) began to appear in the 1880s his works were published piecemeal and poorly, and many autographs and other source materials went missing. During Schubert’s lifetime, and for many years after his death, his music – especially his instrumental music – was championed by a mere handful of performers. For this reason, few pedagogical lines or performance traditions accumulated until late in the nineteenth century.

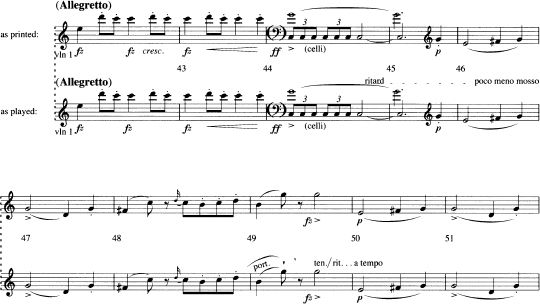

The only reliable body of evidence we have concerning Schubert in performance is the recordings. Somewhere around 1900 the recording industry discovered the saleability of certain pieces in the Schubert repertory: short works were tailored to match the capacity of the disc (Ave Maria, Erlkönig , etc.), then longer ones (Der Hirt auf dem Felsen , piano character pieces), and finally large-scale instrumental pieces (chamber works and the last two symphonies). But while recordings promoted Schubert’s music, they also stultified it. Performers fixed their interpretations in wax, whereupon the power and breadth of commercial distribution and broadcasting began its awesome work. With each advance in sound carriers – rolls, 78 discs, LPs, tapes, and, most recently, CDs – a rather standard “Schubert style” has been passed down to successive generations. A few musicians have stood gallantly apart from these influences, but most performers have been enticed in one way or the other. For example, in the C Major String Quintet (D956), how many ensembles, even today, can eschew the now traditional Schrammelmusik ritard, slide and “lift” in the passage given in Ex. 16.1 ?

Example 16.1a and 16.1b C Major String Quintet (D956), mm. 42–51

I first heard this mannerism in my student days, and being young and thirsty for highly “musical” performances, I was convinced that such gestures represented the essence of Schubert’s style. I even borrowed the mannerism for use in his piano music, blissfully unaware that it arose in late nineteenth century Austro-Hungarian cafés and had little to do with Franz Schubert.

Among the tasks of the “historically informed” performance movement, now that it has begun to treat seriously the music of the nineteenth century, is the clarification of such anomalies and anachronisms. 2 In the case of Beethoven, it has attempted to do just that; but Beethoven has always been taken a bit more seriously than Schubert in this regard. Schubert’s own documented thoughts and observations about performance are few. Reports by his friends exist, but they are not specific. Moritz von Schwind tells us that “Schubert’s quartet was performed, a little slowly in his opinion, but very purely and tenderly.” 3 But how slow is “a little slowly”? What exactly did he mean by “very purely” (“sehr rein”)? Did he mean that the overall sound was pleasant, that the intonation was good, or perhaps even that Ignaz Schuppanzigh’s ensemble played the work with no added ornaments?

Since Schubert counted for his success mostly on the loyalty, integrity, competence, and reputation of those musicians who played and sang his music, I have built the first two parts of this chapter around preeminent Schubert performers. Part I is dominated by singers, which fact seems to reflect history. No attempt acomprehensiveness could succeed here, and many Schubertians will go unmentioned. Within a loosely chronological context of performance genres, I have singled out a few musicians who represent important lines of thinking, or whose approaches suggest certain issues. The third part of this chapter is a closer consideration of Schubert problems in the context of today’s historical performance consciousness.

Schubert and Schubertians in the nineteenth century

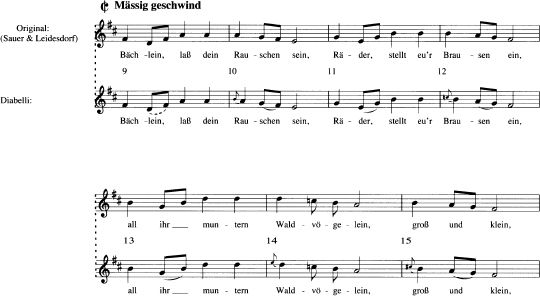

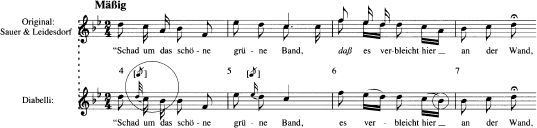

Schubert’s first great champion among singers was the leading male singer of the Kärntnerthor Theater and Hofoper, Johann Michael Vogl (1768–1840), whom the composer often accompanied. On tour of Upper Austria with Vogl, Schubert described the musical rapport he felt: “the manner and means with which Vogl sings and I accompany him, the way we seem to be one single being in these moments , is for these people really new, really unexperienced [italics mine].” 4 Schubert took many of his songs to Vogl before final drafting, and we do not know how many compositional choices were influenced by the singer. Vogl may have been interested chiefly in the music, but he could not have been averse to casting a bit more light upon himself as well. 5 Apparently he treated Schubert’s music quite freely in performance, and he may have exercised a heavy editorial hand in posthumous publications of the songs. He is suspected of authoring the substantial changes to the second edition of Die schöne Müllerin (D795), brought out by Diabelli after Schubert’s death. Some of these alterations are minor but mindlessly frequent additions of grace notes (see Ex. 16.2 ). Other changes involve outright pitch alterations (see Ex. 16.3 ).

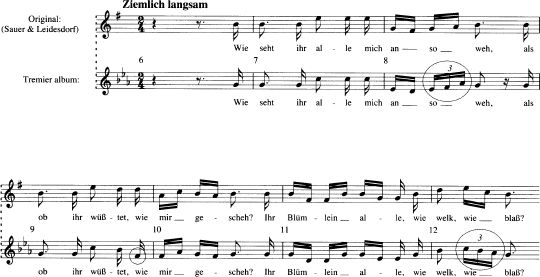

Example 16.4 – again from Die schöne Müllerin – is taken not from the Diabelli edition, but from the private Lieder album of Franziska Tremier, née Pratobevera. Here the embellishments change the rhythmic shape of the line, as well as its pitch content. The song is also transposed down a major third for an alto voice. The author of the changes has not been positively identified.

Simple ornamentation, as in Example 16.2 , was probably a common aspect of performance in that day. But altered rhythms, pitches, and harmonies are more serious matters (Examples 16.3 and 16.4), particularly if they find their way into printed editions. 6

Example 16.2a and 16.2b

Original version of Mein! (D795, 11), mm. 9–15

Diabelli version of Mein! (D795, 11), mm. 9–15

Example 16.3a and 16.3b

Original version of Mit dem grünen Lautenbande (D795, 13), mm. 4–7

Diabelli version of Mit dem grünen Lautenbande (D795, 13), mm. 4–7

Transpositions, of course, were often necessary to suit a singer’s range. Printed collections in various ranges, such as we rely upon today, did not exist, and singers often kept private copies in suitable keys for players who could not transpose. Schubert himself probably transposed in performance to suit the singer. Leopold von Sonnleithner maintains, however, that Vogl transposed songs into difficult and unusual keys and registers in order to create or force extraordinary effects through pitchless and whispered delivery, falsetto, or sudden outcries. 7 Whether he devised these tricks to cover for an aging voice, or whether he was simply an actor at heart is difficult to know. Sonnleithner also mentions another interesting aspect of Vogl’s later style: “Vogl certainly overstepped the written boundaries the more his voice deserted him – but he always sang strictly in tempo.” 8

Example 16.4a and 16.4b

Original version of Trockne Blumen (D795, 18), mm. 6–12

Tremier version of Trockne Blumen (D795, 18), mm. 6–12

Several years after Vogl’s death, Ignaz von Mosel wrote that it was a loss “even more lamentable because he failed to heed my urgent and repeated exhortations to publish a guide to declamation and dramatic singing – one that only he was truly capable of writing.” 9 Vogl had been aware of the need, and had written in his diary: “Nothing has so often revealed the lack of a useful singing method as Schubert’s songs.” 10 He began work on a method shortly before he died, but this fragment has been lost.

One of Vogl’s most celebrated operatic colleagues was Anna Milder (1785–1838), who, in addition to her fame as the creator of the role of Leonore in Fidelio , was also an unwavering Schubert supporter. From the Berlinische Zeitungwe have a critical report of a public concert in 1825 by Milder, who sang Suleika II (D717) and Erlkönig to a full audience and great acclaim:

The great voice of this singer pleases one best in the noble style of singing – as in the two Goethe songs, Suleika and Erlkönig – which Mme. Milder echoed masterfully from her own heart to our hearts…. The tender melody [Suleika ], sung with intimate feeling by Mme. Milder, was enhanced throughout by bright colors in the quite singular piano accompaniment – played with polish by the singer’s sister, Mme. Bürde, née Milder. The sighing of the westwind, and the longing of tender love were effectively represented in these tones. Der Erlkönig … also was splendidly presented. 11

Milder seems to have sung with great warmth, but without Vogl’s theatricality. The word “noble” in the review, plus her status as the leading Gluck heroine of the day, seems to set the right tone.

The third great Schubert song interpreter in the composer’s lifetime was Carl Freiherr von Schönstein (1797–1876). Schubert dedicated Die schöne Müllerin to him, and Schönstein became the foremost champion of this work. Whereas Vogl’s general singing style was declamatory and theatrical, Milder’s perhaps expressive but patrician, Schönstein’s style was smooth and non-ornamental. 12 In him we recognize the spiritual ancestor of such lyrical singers as Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, Hermann Prey, Håkon Hagegård, Olaf Bär, or Boje Skovhus. Sonnleithner believed Schönstein was “one of the best, perhaps the best, Schubert singer, of his time…. This friend of the arts was distinguished by a beautiful, nobly sonorous high-baritone voice, sufficient training, aesthetical and scholarly education, and sensitive, lively feeling.” 13 Schubert, in one of his last letters (September 25, 1828) responded to an invitation, saying: “I accept … with pleasure, for I always like to hear Baron Schönstein sing.” 14

The Schubert singer of greatest historical interest, Franz Schubert himself, probably also had a clear, uncomplicated voice. 15 Anton Ottenwalt writes on November 27, 1825, that Schubert sang “quite beautifully” at Schober’s; 16 and Franz von Hartmann writes on December 17, 1826, that “Schubert sang magnificently, particularly Der Einsame and Dürre [Trockne] Blumen .” 17

Two singers whose careers began during Schubert’s lifetime, but who championed his music mostly after his death were Wilhelmine Schröder-Devrient (1804–60) and Joseph Staudigl (1807–61). Schröder-Devrient lived, after 1823, in Dresden. In 1836 the Wiener Zeitschrift acknowledged “with what wonderfully gripping, thoroughly dramatic vividness” she sang Schubert’s Lieder. 18 Otto Brusatti writes that Joseph Staudigl was the “legitimate successor of Vogl and Schönstein,” singing Der Wanderer (D489) and Erlkönig over 300 times in public. 19 Reacting to his performance of Der Wanderer , the Humorist reported: “Just such mediums are sought by the ossianic spirit that wafts through Schubert’s airs. That is Poetry in Performance.” 20

The most professional pianist in Schubert’s circle was Karl Maria von Bocklet (1801–81). 21 Schubert’s report of Bocklet’s premiere of the Piano Trio in E flat, Op. 100 (D929), with Schuppanzigh and Josef Linke (December 26, 1827) indicates sincere approval (SDB 714). Bocklet also premiered two other difficult works, the C Major Violin Fantasy (D934) and the “Wanderer” Fantasy, Op. 15 (D760), and Schubert dedicated the Piano Sonata in D Major, Op. 53 (D850), to him. The Leipzig Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung wrote that in Bocklet’s hands “every composition gains new color, renewed life, and an exotic, hitherto unexperienced form through his magical performance style.” 22

About Schubert’s own playing, one must read between the lines of the occasional report, for example:

… In Upper Austria … I played [the variations from my new two-hand sonata, Op. 42] myself, and apparently not without an angel over my shoulder, because a few people assured me that under my hands the keys became like voices. If this is true I am really pleased, because I can’t stand this damnable chopping that even quite advanced pianists indulge in. It pleases neither the ear nor the spirit. 23

Not much of specific value can be learned from this report, but at least we know (as if we didn’t know already) that Schubert stood on the side of lyricism in performance. Albert Stadler confirmed that Schubert had “a beautiful touch, a quiet hand – [his was] nice, clear playing, full of soul and expression. He belonged to the old school of good pianists, where the fingers did not attack the poor keys like birds of prey.” 24 Sonnleithner made another important point:

More than a hundred times I heard him rehearse and accompany his own songs. Above all, he kept strict time, except in those few instances where he had specifically marked a ritardando, morendo, accelerando, etc.

Furthermore, he permitted no excessive expression …. The Lied singer … himself does not represent the person whose feelings he portrays; [thus] poet, composer and singer must conceive the song as lyrical

, not dramatic

.

25

Of the major European pianists active during Schubert’s last years and after his death, Felix Mendelssohn was probably best equipped to promote that controlled lyricism. If the general reports of his style are accurate, he was an expressive player within the dictates of the written score. Mendelssohn’s 1839 premiere of the “Great” C Major Symphony (D944) in Leipzig is one of the milestones in performance history. But in fact, as a pianist he had played Schubert’s music in public even during the latter’s lifetime. In Berlin he accompanied Karl Bader in a performance of Erlkönig in November of 1827, and the Leipzig Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung described his playing as “finished and powerful.” 26 Mendelssohn was later active as a Schubert accompanist in Leipzig, where his singing partner was Henriette Grabau (1805–52). She first gained recognition when she sang Die Forelle (D550) at one of the Extraconcerte in the Gewandhaus on October 20, 1828, about a month before Schubert died. Charming and gracious, Grabau was a favorite with Leipzig audiences. The AmZ reviewed her often, but gave no musical details; when she sang Erlkönig (March 6, 1837) the report merely read: “in solo songs she excels, with a highly trained and cultivated voice that gains strength ever anew.” 27

At the 1828 concert where Grabau first sang Die Forelle , Clara Wieck made her public debut with Emilie Reichold in a four-hand performance. 28 Wieck, like her future husband Robert Schumann, was attracted to Lieder, and in particular, to Schubert’s. She often performed Liszt’s Schubert transcriptions, and later in her career she gave Lied concerts with the baritone and conductor Julius Stockhausen (1826–1906). Stockhausen had been a pupil of Manuel Garcia fils , and was an intimate friend of Brahms. He believed strongly that Schubert’s works should be presented in their entirety, and he stressed the cyclical unity of the major song groups. Richard Heuberger relates that Brahms regarded Stockhausen’s zeal in this respect misguided where Schwanengesang (D957) was concerned.

Brahms was rude with [Julius] Röntgen in the morning, because with [Johannes] Messchaert he had [played] a number of songs from Schubert’s Schwanengesang. Brahms maintained that they didn’t all belong together and that it was silly to sing them as a group. To Röntgen’s argument that Stockhausen also sang them as a group, Brahms replied, “Well, I never had much influence on Stockhausen, and I was always against that sort of thing. But if you know better, then that’s just fine!” 29

In Vienna in 1856, Stockhausen became the first artist to sing Die schöne Müllerin as a complete cycle. From Hamburg in 1864, Fritz Brahms wrote to Johannes that Stockhausen had recently sung Winterreise to a “bursting full house,” that he intended to sing it again at discount price tickets, and then later Die schöne Müllerin as well. 30 Hanslick wrote of Stockhausen in 1854 that he was “equipped with an unusually well schooled voice in an era when screaming is more popular.” 31 Stockhausen published a comprehensive singing manual, dedicated to vocal style in song, oratorio and opera from Bach to Wagner; but strangely, Schubert’s name does not appear even once. 32

Brahms was an avid Schubert player, as a soloist and as an accompanist to Joseph Joachim, Julius Stockhausen, Joseph Hellmesberger, Gustav Walter, George Henschel, and others. 33 When someone remarked that Schubert’s technical demands were not so high – an attitude that has pervaded conservatories and competitions until the present – Brahms replied, “Don’t say that! His music is so often eternally perfect! I believe that most people doubt the difficulty of Schubert’s music, because it is known how easily he composed. Well, for one person it’s hard, and for the next it’s easy! And even Schubert often had his problems.” 34 Brahms’s playing, like Mendelssohn’s, is said to have been well-structured and musically responsible; his approach to Schubert’s piano music was probably similar.

During Schubert’s lifetime his chamber music had fared better than his other instrumental works. Bocklet and Josef Slawjk had premiered the B Minor Rondo for Violin and Piano (D895), plus the C Major Fantasy (D934). 35 Schuppanzigh’s quartet had premiered the A Minor Quartet, Op. 29 (D804) in March 1824, and later the Octet (D803). 36 By the time of Schubert’s “Composition Concert” (March 26,1828), when the ensemble played the first movement of the G Major Quartet (D887), Schuppanzigh had been replaced by Joseph Böhm (1795–1876), who also played with Bocklet and Linke in a further performance of the Piano Trio in E flat.

After Schubert’s death public performances of his chamber music declined until the 1850s, when the Hellmesberger Quartet presented the later quartets in the Musikvereinssaal in Vienna. 37 The quartet had been founded in 1849 by its first violinist, Joseph Hellmesberger (1828–93), the son and pupil of Schubert’s school friend, the violinist Georg Hellmesberger (who also taught Joachim, Auer, Hauser, and Ernst). The Hellmesberger Quartet’s performances of Schubert’s works led the way to some important first publications, including the G Major Quartet, the C Major Quintet, and the Octet. The other major ensemble to take Schubert’s music seriously was the Joachim Quartet (founded in the 1860s), also famous for its commitment to the works of Brahms and Beethoven.

Among nineteenth-century conductors, the list of major Schubert supporters begins with his friend Johann Baptist Schmiedel and continues with Mendelssohn, Wilhelm Grund, Georg Schmidt, Johann Herbeck, A. F. Riccius, August Manns, William Cusins, Julius Stockhausen, Brahms, and George Henschel. Schmiedel and Brahms were more involved with Schubert’s vocal works, whereas the others were responsible for the symphonic premieres. Mendelssohn’s premiere of the “Great” C Major Symphony in Leipzig had been followed in 1841 by performances in Halle, 38 Bremen, 39 Potsdam 40 and Hamburg. 41 By 1850 it had been played in New York, 42 but years went by before it was premiered in London or Paris. 43 Stockhausen was possibly the first conductor to perform it without cuts (Hamburg, 1863). 44 In Stockhausen’s view, Schubert’s difficulties and challenges could not be avoided or edited, but were best presented for what they were.

Schubert and the recording age

The first Schubert “performances” on record date from the last years of the nineteenth century: among them are a recording of Ave Maria made by Edith Clegg in England in 1898 and a group of Lied recordings by anonymous singers (in French) released by the Pathé brothers in 1899. With some notable exceptions (Elena Gerhardt, Harry Plunket Greene, George Henschel, Rita Gingster, Therese Behr) the early recordings were made by famous opera singers.

The general style on these recordings is familiar: pronounced vocal slides and lifts, close vibrato (or sometimes none at all), extended holds in places where today we are accustomed only to localized rubatos, some extreme tempo variations, etc. From these practices can we learn anything about an even earlier period? Minnie Nast’s “pure tone” and lack of a continuous vibrato (Heidenröslein , 1902) are echoed by other sopranos, and suggest a lingering tradition among high voices of the period. But Gustav Walter’s deeply moving performance of Am Meer (1904) reveals a continuous, modern vibrato, albeit slim and perfectly controlled. Walter – a clear, high tenor – was forty years older than Nast; he was born in 1834, only six years after Schubert died. Knowing, as we do, that singers rarely rebuild their basic techniques as they grow older, we might assume that Walter learned that vibrato sometime in the late 1840s or early 1850s.

Walter probably chose his pianist carefully for these recordings (he made three), for he once had been accompanied by no less an artist than Johannes Brahms. But in general, the accompanists on these early recordings rarely aspired to artistic greatness. A comic example is provided by Paul Knüpfer’s 1901 recording of Ungeduld (which title more or less suited the occasion), wherein his unfortunate pianist (mercifully unnamed) is first coaxed and finally dragged along by his musical collar to the end of the performance. Fortunately, notable exceptions existed. Much can be learned about interactive Lied accompaniment through the recordings of George Henschel (1850–1934), who played for himself, and Arthur Nikisch (1855–1922), who was the regular partner of Elena Gerhardt (1883–1961). Nikisch’s beautiful playing on their recording of An die Musik (1911) might well replicate Schubert’s own close manner of accompanying Vogl. And the occasional pianist aspired even to brilliance, as on Lilli Lehmann’s 1906 recording of Erlkönig or Harry Plunket Greene’s 1904 recording of Abschied (pianists unnamed). 45 Later in the century the ideal Lied accompanist was to emerge in the person of Gerald Moore (1899–1987), who played for the greatest singers of the modern age – from Feodor Chaliapin to Hermann Prey. He and Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau probably recorded more Schubert songs, together and separately, than any pianist and singer in history. Moore’s book on the cycles is a revealing performance document. 46

Actually, all great Schubert pianists have had a common interest in Lied accompaniment; for example, Benjamin Britten (whose Schubert performances with Peter Pears gave rise to heated discussion about the assimilation of dotted rhythms to triplets), 47 Edwin Fischer (who recorded Lieder with Schwarzkopf and taught a group of pianists who also became great Schubert accompanists), and Artur Schnabel (1882–1951). Schnabel and his wife Therese Behr (1876–1959) “spread the word” among a devoted new generation of pupils and Schubert listeners. Their six program Berlin cycle of 1928 featured the two Müller cycles and Schwanengesang , plus a number of individual songs (in addition to the eight last sonatas and the “Wanderer” Fantasy). 48 They reintroduced a number of forgotten songs, and attempted to rid the known ones of unworthy performance traditions.

Schnabel and his son Karl Ulrich Schnabel made recordings of Schubert four-hand works, as did Benjamin Britten and Svjatoslav Richter, and several other celebrated “teams.” But the first duo to explore Schubert’s four-hand literature comprehensively was formed by two Fischer pupils – Jörg Demus and Paul Badura-Skoda – who also collected period pianos and reintroduced them to the public as the proper instruments for playing Schubert.

Schubert’s chamber music with piano – the violin-piano duos, the piano trios, and “Trout” Quintet – was recorded copiously in the first half of the century. Ensembles with piano tended to be made up of soloists – Casals–Thibaud–Cortot, Kreisler–Rachmaninoff, Heifetz–Piatigorsky–Rubinstein – and the industry has continued to promote such groupings. The commercial reasoning behind this practice is obvious, but from the beginning the resultant performances were often marked by the highly distinguishable habits of the individual players rather than by the ensemble thinking that arises, for example, from constant quartet playing. Schubert’s string quartets, on the other hand, were played and recorded by permanent chamber ensembles – the Flonzaley, the Kneisel, the Léner, the Busch, the (1st) Pro Arte, the (2nd) Budapest and the Kolisch Quartets. They concentrated mostly on the Quartettsatz , (D703), the late quartets (D804, 810, and 887), and the C Major Quintet. In terms of historical perspective, the Kolisch Quartet was especially important. Rudolf Kolisch (1896–1978) developed techniques that allowed modern players to re-create the performance practices of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. He devised bowings, bow strokes, and fingerings that would approximate the proper sounds; he researched tempos of the earlier period and insisted upon proper sonic balances (i.e., the first violinist does not always have the tune!).

The conductors of the early twentieth century recorded only a handful of Schubert’s orchestral works: the ballet music to Rosamunde

(D797), the “Unfinished” Symphony (D759), and the “Great” C Major Symphony. Most of these recordings reflect the performance styles of the last century: cuts (mostly in matters of repeats, but not entirely), ponderous tempos, wide tempo fluctuations and rubatos, large forces, reorchestrations, and more. In the late 1950s René Leibowitz (1913–72) began to remove some of these layers of tradition, most successfully in terms of phrasing and structure, but also through more serious consideration of internal tempo relationships.

49

His goal was to replace tradition with objective performance criteria, and his trailblazing recording of Schubert’s “Great” C Major Symphony (RCA GL 32533, no date) obviated a number of mannerisms of the past. The next advances in the performance of this work were made by Carlo Maria Giulini (DG, 2530 882, 1977) and Charles Mackerras (Virgin, 7596692 3, 1988), whose readings of the autograph (where the opening is marked  instead of c as in many editions) led them to the 2:1 tempo relationship between the opening and the Allegro of the first movement. In 1990, Roger Norrington (EMI 7 49949 2) went the final step by finding not only the proper relationship between these two sections, but the proper basic tempo as well.

50

instead of c as in many editions) led them to the 2:1 tempo relationship between the opening and the Allegro of the first movement. In 1990, Roger Norrington (EMI 7 49949 2) went the final step by finding not only the proper relationship between these two sections, but the proper basic tempo as well.

50

Schubert issues in the context of the historical performance movement

Given that most Schubert lovers are now familiar with the sound of period-style instruments (but not solo voices), to offer a description here seems unnecessary. 51 But the performer who is interested in more than just the sonic aspect of historical performance vis à vis Schubert has a number of other issues to consider.

Style

Example 16.1 showed a practice of the “Viennese style”; further characteristics include comfortable tempos, gemütlicher Humor (represented by exaggerated string slides, rhythmic hesitations, etc.) and related mannerisms. This style is said to have arisen from Biedermeier dance traditions, but seems indistinguishable from that of late nineteenth century Viennese Unterhaltungsmusik – typified in the playing of the Schrammel Brothers Quartet and the conducting of Eduard Strauss. Strauss, notably, learned his rubatos not from his family, but from the school of Liszt, Wagner, and Bülow. 52 One can see how the flexibility of the gesture in Example 16.1 might have been useful to a dance accompanist whose primary job was to unite music and motion, and who, having coordinated his upbeat with the ascending figure on the dance floor, was then obliged to hesitate slightly until Newton’s law took effect. But in the context of Schubert’s music – especially the serious works – such gestures become kitsch. Can a more historical approach to Schubert’s style gradually wean us and our audiences from such popular misrepresentations?

Structure

The main issue here concerns repeats in dance forms: does the “one time only” rule for the repeat – now so ingrained in our collective consciousness – apply to Schubert? For Mozart and Haydn the practice is not binding, but no authoritative studies exist for the early nineteenth century. Special cases raise questions about such issues as the proper place for the final repeat in the Scherzo of the C Major Quintet. 53

Notation

Four highly volatile issues are involved. (1) Articulation: the meaning of dots and wedges, and Schubert’s shorthand for repeating articulated passages. These two questions have been treated (not solved) for earlier composers, but for Schubert they remain relatively unexplored. Norrington’s notes to his recording of the C Major Symphony express the problem succinctly. (2) Rhythmic alteration: does one assimilate Schubert’s dotted notes with his triplets where they coincide? This issue has raged throughout the twentieth century, and although it has been shown to be a simple question of compromise for technical accommodation, many scholars continue to see it as a notational problem. 54 Some musicians sidestep the problem by overseparating the component rhythms (double and even triple dotting against the triplets), as in most performances of the first movement of the Piano Trio in B flat, Op. 99 (D898). 55 But Schubert calls purposefully for the conflict as the dominant affect of such movements. Overdotting was indeed an expressive device for soloists in the galant period; it is mentioned in sources as late as Schubert’s period, but it is not appropriate for ensemble playing. (3) Expressive marks: here the question concerns such problems as elongated accents vs diminuendos. Some performers believe the answer to be a simple matter of placement: over the note or under it. 56 A highly disputed case is the last chord of the C Major Quintet, often printed (and played) with a diminuendo. Martin Chusid lets it read firmly and sensibly as an accent in the Neue Schubert-Ausgabe , although in other contexts the intent of the hairpin sign is not so clear. 57 Nevertheless, Jaap Schröder’s assertion that Schubert’s intention “has in many cases to be decided upon by the interpreter’s taste and sense of style” reveals one of the central weaknesses of the historical movement to date – the tendency, when in doubt, to revert to intuition instead of renewed research. 58 (4) Texts: what is an Urtext? Does one choose the 1825 or 1827 published text of Der Einsame (D800)? Does one reject Brahms’s finishing touches to Schubert’s C Minor Symphony, even though that decision demands a return to the incomplete state of Schubert’s score? Where do the limits of “authenticity” clash with those of common sense? 59

Tempo

This issue is twofold. In a controversial but brilliant article of 1943, Rudolf Kolisch derived a set of basic tempi for Beethoven’s entire works from his known metronome markings – matching movements by character.

60

A similar project is possible for Schubert: known metronome marks, for example, include those for his first published twenty songs (Opp. 1–7), the individual pieces of an entire opera (Alfonso und Estrella

), and the parts of the Deutsche Messe (D872).

61

A related consideration concerns the instrumental movements based on songs (Der Wanderer

[ = MM 63], Der Tod und das Mädchen

[

= MM 63], Der Tod und das Mädchen

[ = MM 63], Die Forelle, Sei mir gegrüßt

, etc.) in relationship to the tempi of those songs. Second is tempo alteration. In traditional performances, unmarked tempo swings between given sections sometimes range as much as 5–20 metronome marks. Menuet and scherzo trios are particularly susceptible to tempo shifts, but also variation movements, minor key sections within major key movements, and second thematic groups in general.

62

= MM 63], Die Forelle, Sei mir gegrüßt

, etc.) in relationship to the tempi of those songs. Second is tempo alteration. In traditional performances, unmarked tempo swings between given sections sometimes range as much as 5–20 metronome marks. Menuet and scherzo trios are particularly susceptible to tempo shifts, but also variation movements, minor key sections within major key movements, and second thematic groups in general.

62

These are only the most pressing issues that await closer attention by those who take Schubert’s music as serious art. A complete list might occupy us for years. Once the reading and research is done, we will probably find that much of what we have taken to be instinct about how to perform Schubert has been, in reality, deep conditioning. With some effort, we can replace this conditioning with a search for ideals. After all, Franz Schubert was concerned not with clay, but with ether.

Follow the heavenly sounds

And there shall we find Schubert again.

after Franz von Schober’s An Franz Schubert’s Sarge