CHAPTER 2Cultures

The anarchist critique of order as a form of disorder is not new. Towards the end of the play King Lear declares:

Through tattered clothes great vices do appear;

Robes and furred gowns hide all. Plate sin with gold,

And the strong lance of justice hurtless breaks.

Arm it in rags, a pigmy’s straw does pierce it.

None does offend – none, I say, none. I’ll able ’em.

Take that of me, my friend, who have the power

To seal th’ accuser’s lips. Get thee glass eyes,

And like a scurvy politician seem

To see the things thou dost not.1

In the nineteenth century this kind of critique transformed anarchism into the revolutionary politics of outlaws. Like the protagonists of disorder, their critics, the anarchists reflected on questions of governance, institutional design and organizational efficiency. But because they set their face against private property and the institutions deemed necessary to preserve, regulate or appropriate it for the public good, anarchists adopted a stance to these questions that appeared negative, if not hostile. And because they believed that the new worlds that had emerged in the wake of the great eighteenth-century revolutions had failed to deliver liberty, equality and fraternity, they not only asked how existing social arrangements could be remodelled, but did so critically, in order to achieve further transformative change.

Defenders of the existing orders often asked questions about duty and obligation. How could citizens be induced to love their countries, serve their kings and presidents and respect the rights of others (especially property-owning minorities)? What could progressive governments do to ensure good governance across the globe? How could responsible governments protect citizens against outsiders, secure their economic well-being and ensure their access to resources? Anarchists also probed these questions and still do, but usually in an effort to expose the costs of obedience and the risks of self-aggrandisement. At the same time, they try to understand the mechanisms that maintain the stability of these regimes, notwithstanding their evident unfairness. In the language of nineteenth-century politics, they examine how mastership and wage slavery preserve systems of oppression.

In this chapter I will focus on the cultural critiques anarchists have advanced to explain the constancy of subjugation. I am using culture in the sense that Rudolf Rocker used the term, as an approach to living rather than as an aspect of social life associated with the rarefied enjoyments of intellectuals, or the special habits of elites.2 Rocker’s idea, which he advanced in his critique of twentieth-century dictatorships, both fascist and Stalinist, was that culture was about the study of human interventions in nature and the creation of social environments. This conception placed culture in relation to nature rather than in opposition to it, blurring the boundaries between human and non-human life and dissolving the ‘artificial distinction’ between ‘nature peoples’ and ‘culture peoples’. For Rocker, there is never an absence of culture, only alternative cultures, more or less productive or destructive, more or less organic or plastic, more or less commodious or limited, more or less fulfilling or cheerless. ‘Even slavery and despotism are manifestations of the general cultural movement,’ he argued.3

Rocker’s conception complicated histories that purported to reveal the foundations of national differences in order to assert the special character of particular groups of people. Discomfited by what he saw as the brutality and aggressiveness of European governments and the competitive, xenophobic sentiments they inspired, Rocker wondered how peoples captured by and integrated into these regimes could rise above their presumed national interests, set aside the privileges that inclusion in the nation bestowed and act in solidarity with others. The study of culture, encompassing the entire history of human interventions in nature and the ‘crutches of concepts’ used to explain it, gave him his answer. Setting out to isolate the factors that explained cultural turns, Rocker argued that culture was about mastery and perfection, but not necessarily about exploitation and stasis. On the contrary, it was a process through which individuals imparted their best selves in the world in order to improve their environments. The puzzle that culture posed, therefore, was to understand how cultures became degraded and how to repair them by fostering ways of living that enabled collaboration with others while also preserving nature.

Rocker linked the impoverishment of cultures to the rise of the state, and in some 600 pages he explained what he meant by this term. Rather than attempt to replicate or summarize his analysis, I will outline three ideas of domination to explore the anarchist cultural critique, all of which emerged in the early period of the European movement. I will also look at some of the educational initiatives that anarchists have promoted to combat oppressive behaviours and promote alternative cultural practices. Some of the big questions that anarchists have asked about domination, pointedly with a view to promoting cultures of anarchy, are about learning – what, how and why we learn and acquire knowledge about the world. Working to undo the domination that secures co-operation in the state, anarchists have always been involved in education and they have set up free schools (often spelt ‘skools’ to distinguish them from state institutions) and experimented with curricula and pedagogy in both mainstream and alternative libertarian institutions. Their rejection of domination drives this interest, focusing attention on education as a process of unlearning and relearning, empowering individuals to emancipate themselves to enable self-government.

Domination

The concept of domination is derived from the Latin ‘dominus’, which referred to the absolute power of a lord or master to rule a household, and the related term ‘dominium’ which designates ownership as well as rulership. In ordinary language domination is linked to the right to exercise power, the sovereignty and authority of the Church and State, as well as to the actual exercise of power, through the assertion of supremacy or in government. Because it has been defined in relation to the absolute power of the master, it is also applied to tyranny and arbitrary rule. In this sense, domination is associated with injustice, usurpation and the denial of liberty, especially through the cultivation of relations based on dependence.

Domination, then, ordinarily describes institutions in the broadest sense – organizational arrangements, norms and behaviours. To take an example from popular literature: in Jane Eyre Mr Rochester dominates as the master of his household. His customary habit is to adopt a tone of command. Even though he wants to avoid treating Jane as an inferior, their relationship is in fact based on domination because of the power advantages he enjoys. She tells him that for as long as he employs her, she is his dependant. She remains his ‘paid subordinate’ whether or not he growls at her. Non-domination describes countervailing practices which, in Charlotte Brontë’s novel, are rooted in the cultivation of equality. This comes from resisting other people’s certainties. Jane finds the strength to resist domination in sisterhood and voluntary agreement. She rises above the sense of victimhood fostered by Lowood School’s tyrannous punishment regime when her rebellious schoolmate refuses to accede to Jane’s public disgrace. Later, having found that she prefers a life ‘free and honest’ to one of material comfort and slavery,4 she rejects the patriarchal authority asserted by St John, her would-be suitor, first by avowing her right to consent to his marriage proposal and then by firmly rejecting it.

All of these ideas resonate in anarchism. Domination is understood as a diffuse kind of power, embedded in hierarchy – pyramidal structures, pecking orders and chains of command – and in uneven access to economic or cultural resources. Domination also describes a type of unfreedom which can be exercised through habit, force or manipulation. Linked to privilege, domination is manifest as social power derived from status or unearned advantage, for example whiteness, maleness, physical ableness. This is felt as domination both in the marginalization of individuals who fail to fit the profile and in prejudice. However, the overlaps between these conceptions have given rise to multiple critiques. The rejection of domination unifies anarchists in shared struggles against the monopolization of resources and the centralization of power, representation, racism, imperialism and authority, while leaving the institutional and sociological mechanisms that explain it open to discussion. Here I will focus on three relationships of domination: domination and law, domination and hierarchy, and domination and conquest.

Domination and law

In anarchist critiques law often appears as a two-headed hydra. It has one life in abstract political and legal theory and another in practical policy implementation. From an anarchist perspective, legal theory grounds the implementation of law in necessity. It does this by buttressing two related ideas: that social groups are incapable of inventing their own regulatory systems and that social life in law’s absence is unattractive. In theory, law is the instrument that brings security and freedom by constraining bad behaviours. John Locke, sometimes celebrated as one of the fathers of liberalism, said that where law ends, tyranny begins.5

The practical implementation of law removes the power of rule-making from the majority of people it manages. People know what law is, they know that it commands obedience and that transgression will result in punishment. However, most people have little knowledge of the content and scope of the law and lack the technical ability to participate meaningfully in making, interpreting or enforcing law. The mystery of the law reinforces the idea of its necessity. Whenever we call on the services of legal professionals – police, solicitors, barristers and judges – we implicitly recognize our reliance on law and our inability to conduct our affairs in its absence.

For anarchists like the 1848 revolutionary, political exile and journalist Sigmund Engländer, the abstraction of law from social life was a sign of political corruption. His conception of law and domination neatly paralleled the critique of wage slavery and mastership advanced by the Chicago anarchists, perhaps not surprisingly since he, like they, was heavily indebted to Proudhon. Emerging from the disarray of the IWMA, he attacked law because it facilitated exploitation and dependency and because he thought lawmakers assumed they knew what was best for everyone. On both counts, law was inherently dominating.

The mismatch between the ideal and reality of law was at the heart of Engländer’s analysis of domination. Reviewing a period of French revolutionary change between 1789 and 1848, Engländer used law as a kind of shorthand to refer both to an aspiration for perfection, based on a commitment to individual rights, ‘the revolutionary idea of our century’,6 and a messy, protracted process of constitution-writing that assumed inequality. The ideal of law was that it would bring order through harmony. The reality was that it instituted division through competition and oppression.

The rule of law was supposed to guarantee justice in the republics that emerged after 1789, but in Engländer’s view it was actually applied to regulate constitutional settlements that were underpinned by an exclusive right to private property. Depicted as ‘the expression of universal reason, the public conscience, the justice, the mighty bulwark of mankind against barbarism’,7 law was in fact the expression of a ‘social antagonism’. It was never neutral or ‘blind’. In law, the revolutionary principle of individual right had seamlessly morphed into a very bourgeois right to private ownership. Law could only arbitrate disputes partially and in order to maintain the inequalities that the commitment to exclusive property rights created. Following Proudhon, Engländer argued that ‘[a]bolition of the economical exhaustion of man by man, and the abolition of the government of man by man’, were just two aspects of the same problem. His summary view was that law dominated as ‘a weapon wherewith to frighten, to enslave, and to torture the oppressed’.8 It was ‘the child of injustice and ambition’ and ‘the last lurking-place of faith in authority’.9

Engländer turned to philosophy to explain the transformation of law from a principle of right to an instrument of wrong. The key figures he identified were the eighteenth-century philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau and the Jacobins who had been enthused by his writings, Robespierre and Saint-Just. These three were the law’s most forceful advocates. Casting his eye over their work, Engländer observed a fatal flaw in the theory and practice of lawmaking. As sworn opponents of absolutism, these revolutionaries appreciated the tyrannous power that kings enjoyed as a result of the exclusive right they claimed to make laws. Yet rather than challenging the principle of lawmaking – the source of tyranny – they simply relocated the power of lawmaking – sovereignty – from the monarch to the people.

Engländer did not explain the details of the philosophical arguments but these were discussed by other anarchists, notably by Proudhon, Bakunin and Kropotkin. Particularly critical of Rousseau, the anarchists argued that he had wrongly used the device of the state of nature – an imagined pre-political condition – to examine the formation of government. Rousseau had argued that individuals enter into a compact with each other and that this marked the start of a process which leads individuals from a state of nature into a system of law and government. The terms of Rousseau’s compact were very generous: individual liberty and equality were guaranteed and law was rooted in the people’s sovereign power. Nevertheless, the anarchists rejected Rousseau’s story about government. They accused him of wrongly inventing an artificial distinction between primitive pre-political and civilized political orders and of misrepresenting social organization as a special achievement when, in fact, it was a characteristic feature of human existence. Theorized in this manner, the anarchists argued that government was wrongly depicted as the outcome of a conscious action undertaken to perfect social life. The same account miscast law as an instrument of social excellence.

Rousseau’s theory of government was powerfully deployed by revolutionaries struggling against royal absolutists, but from the anarchist perspective it was far from transformative. Evaluating its impact, Engländer argued that the radicals had wrested the power of lawmaking from monarchical control with the expectation that law would realize a general good, ‘abolish all the vices of humanity’ and make people free, happy and good. The abolition of monarchy tricked the philosophers into thinking that the removal of arbitrary power was sufficient to eradicate tyranny. This mixture of naivety and vanity had proved deeply conservative. After the revolution the lawmaker-philosophers were in charge, not the king. But ‘[o]therwise there was no difference between Louis XIV, who made his uncontrolled will equivalent to law’ and ‘Rousseau, Robespierre, St Just &c.’10 The character of leadership altered dramatically, yet the principle of command was reinforced. Worse still, having empowered the people in theory, the revolutionaries then discovered that government was just too big and too complex to allow the people to actually make the rules. There were simply too many to exercise sovereignty directly. Faced with this reality, the well-meaning but deluded utopians were compelled to restore the feudal principle of representation, once used to constrain the monarch, to make the system operable.

When it came to writing the constitution, Engländer argued that the lawmakers compounded their errors by deliberately placing themselves ‘outside society’. Desperate to ensure that constitutional law was unsullied by factional bargaining, the philosophers created special conventions and charged the people’s representatives with devising universal rules that would benefit all. Since philosophy had already elicited the principles of right on which law would be based – life, liberty and property – the lawmakers automatically assumed that there was a natural correspondence between their ideals and the interests of the millions of individuals the law would supposedly empower. Confidently constituting themselves as ‘the will and soul of the nation’, they thus ended up introducing a set of rules that simultaneously recognized the people as sovereign and systematically disempowered the citizenry.

By enshrining the idea of justness against arbitrary monarchical whim, law commanded respect even while it tramped the rights and liberties of individuals into the dirt. On this view, the revolutionary idea of rights had been betrayed. Law dominated by securing obedience to oppression. ‘Every arbitrary act of tyranny is tolerated, if … it is done by some twist of a law,’ Engländer commented sourly.11 Similarly, by channelling widely shared aspirations for freedom into institutions sanctified by the constitution, law dominated by detaching constitutional questions from arguments about power and policy. Every ‘prophet sets up the twelve tables of the law; the French Socialists write no more theories, but issue formulated decrees even as charlatans juggle off receipts for wonderful cures’. In the unending struggle for control of law, ‘[e]very class hopes that when the war is over the law will remain with it. The law is to every party leader the mould into which the raw material is poured and society modelled’.12 These partisan debates about the remit and proper application of legislation simultaneously rendered the social antagonisms that underpinned law invisible and opened up limitless possibilities for the regulation of social life. Trade, schools, healthcare could all be managed through legislation, in an effort to mitigate the effects of structural inequality, without ever threatening law’s institutionalization.

Why was law dominating, if the people was able to voice its opinion and the laws that were enacted in its name made it happy? Engländer offered four reasons. His first response was that the normalization of law turned the real individuals who constituted the people into subjects and slaves. The people could only exercise decision-making power within a framework of law that was not of any individual’s own making. Second, submitting to law involved the suspension of individual judgement. Individuals adhered to law and either neglected or were forced to ignore the ‘inner voice’ of their ‘own reason’.13 Albert Parsons had advanced the same view at his trial in Chicago:

The natural and the imprescriptible [sic] right of all is the right of each to control oneself … Law is the enslaving power of man … Blackstone describes the law to be a rule of action, prescribing what is right and prohibiting what is wrong. Now, very true. Anarchists hold that it is wrong for one person to prescribe what is the right action for another person, and then compel that person to obey that rule. Therefore, right action consists in each person attending to his business and allowing everybody else to do likewise. Whoever prescribes a rule of action for another to obey is a tyrant, a usurper, and an enemy of liberty. This is precisely what every statute does.14

Third, the deferential effects of power exacerbated the regulatory impact of law-governed systems. Observing that the ‘people conceives for those whom it has elected an absolute adoration’,15 Engländer acknowledged that only a mere ‘knot of free ungovernable men desires that in the universal struggle for the post of lawgiver, the law itself may be broken up’.16 His explanation of the unpopularity of the anarchist cause led him to uncover the final dominating effects of law. This was the homogenization of interests. Bundled together as the people, he argued, ‘separate subjects or citizens are immovable or silent’.17 Law was a far cry from the principle of individual right that the revolution had proclaimed and the idea of self-emancipation that the IWMA drew from it. It bestowed ‘so-called sovereignty of the people’ in a manner that killed ‘individual liberty as much as does divine right’ and which was ‘as mystical and soul-deadening’.18

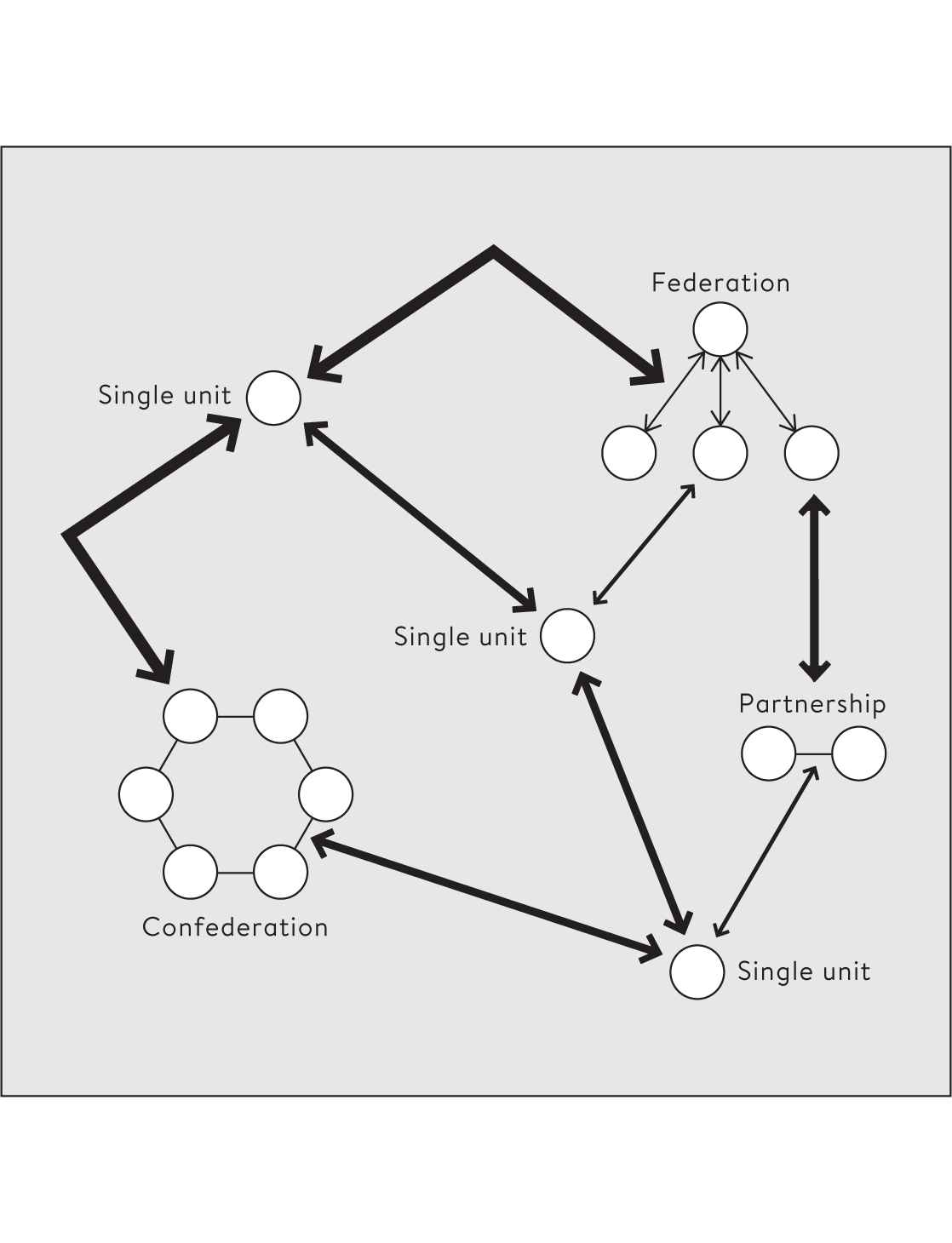

Engländer coupled his critique of law and domination with a proposal for institutional redesign. His suggestion was to divert the ‘blood’ that rushed to head of the ‘State body’ into ‘separate veins’. Breaking down the body politic would overcome the need for representation and enable individuals and social groups to govern themselves directly, by their own rules: reconstitutionalizing on the basis of individual right. Linking domination to the alienating, stultifying effects of law on individuals, Engländer found the antidote to tyranny and mastership in the genius of rebellion and, borrowing Max Stirner’s vocabulary, in egoism. In Engländer’s anarchism, egoism – living without domination, ‘for himself and by himself’19 – required recognizing both the permanence of ‘factions’ and neighbourliness. While factions pointed to social pluralism, neighbourliness was another term for interdependence. Engländer’s ambition was to substitute what he called ‘social palpitations’ for bourgeois ‘harmony’.20 On this view, non-domination became a process of human interaction driven by individuals struggling to be ruled in certain ways while always standing firm against the temptation to govern through the imposition of law.

Domination and hierarchy: Bakunin and Tolstoy

While Engländer was interested in institutional design, other anarchists examined the micropolitics of domination. In this perspective, domination refers to the formal and informal customs and practices that order everyday relationships, particularly by conferring status. A significant disagreement between Bakunin and Tolstoy about the mainsprings of obedience and authority highlights a division within anarchism about the ways in which hierarchy is perpetuated. However, there is general agreement about the privilege that domination establishes and the disparagement it normalizes. Domination establishes social hierarchies by distinguishing masters from subalterns.

The disagreement between Bakunin and Tolstoy was about God and authority. These terms described the idea of absolute truth and the right of command. For Bakunin, hierarchy was sustained by the unquestioning acceptance of authority backed by the knowledge of the divine being. Tolstoy agreed that hierarchy stemmed from the failure to challenge authority but argued that the prerequisite for non-domination was the recognition of God. Bakunin’s professed atheism and Tolstoy’s unorthodox Christianity appear to make the gap between their positions unbridgeable. As if to emphasize this, anarchists have often invoked Bakunin and Tolstoy to variously reject and embrace religion in the name of anarchism. Had Bakunin and Tolstoy rehearsed their ideas with each other directly, the commonalities of their critiques might have become more apparent: neither version of the thesis endorses religious institutionalism and both require individuals to consider what pronouncements they will accept as authoritative. Both distinguish consent from obedience and wilfulness from duty. Moreover, both call on individuals to exercise judgement, which often requires courage and it is an essential step towards non-domination.

Famously reversing Voltaire’s dictum, ‘if God did not exist, it would be necessary to invent him’, Bakunin declared, ‘if God really existed it would be necessary to abolish him’.21 His objection to the divine was philosophical and sociological. He used the term political theology to explain it.22 The critique of philosophy turned on his belief that the idea of original sin structured orthodox western thought. Philosophers had absorbed the Christian idea of godly perfection and the story of human corruption and exile from Eden. Consequently, the problem that philosophy wrestled with was how to transcend the dirty, imperfect material world and how to improve corrupted humanity. Even modern philosophy – Bakunin had Hegel’s Idealism in mind – adopted this starting point. Hegel placed reason with a capital ‘R’ rather than God at the heart of his metaphysics, but his complex, transformative, evolutionary history was only another mechanism designed to show how humanity would raise itself up from baseness and achieve perfection over time. Marxism, too, was a form of political theology, even though Marx advanced what he called a materialist theory. Bakunin argued that Marx’s materialism had only succeeded in regrounding Hegel’s Idealist philosophy in economics. This changed the motive force of history but did not succeed in turning Hegel on his head as Marx claimed. For whether history was linked to the release of reason in the world or to changes in patterns of ownership and production, the idea of progressive transformation towards perfection was common to both. Bakunin argued that a more thoroughgoing materialism was required to upend Hegel. Real materialism meant rejecting notions of eternal truth and the divine and rooting philosophy directly in human experience.

In this context, the idea of God was inevitably enslaving. ‘God being master,’ Bakunin argued, ‘made man the slave.’ God was ‘truth, justice, goodness, beauty, power, and life, man is falsehood, iniquity, evil, ugliness, impotence, and death’.23 Individuals could attain goodness but only through revelation and this was predicated on obedience to authority: subjection.

Bakunin examined the instrumentalization of philosophy in order to press his sociological critique. His argument was that faith functioned as an opiate which bred acceptance of the obvious injustices of social life. When this idea was hardwired into social life it enabled a whole class of functionaries to use the ‘semblance of believing’ to torment, oppress and exploit. Bakunin’s list of exploiters was long: ‘priests, monarchs, statesmen, soldiers, public and private financiers, officials of all sorts, policemen, gendarmes, jailers and executioners, monopolists, capitalists, tax-leeches, contractors and proprietors, lawyers, economists, politicians of all shades, down to the smallest vendors of sweetmeats’.24 The most disadvantaged were inured to the hardships they experienced because of the comfort they took from their faith in God’s benevolence and care.

The anarchist twist Bakunin added to this familiar argument was that the power structures that sanctioned authority were a manifestation of religious belief. Distinguishing atheism-as-faithlessness from anarchist atheism, Bakunin echoed some of Engländer’s themes to critique radicals, freethinkers and Masons who assailed Church authorities but only sought to reform existing structures to profess a new political theology. These atheists attacked religious institutions and represented themselves as non-believers, but they remained wedded to hierarchy and mastership. For Bakunin, this was shallow atheism. While Bakunin often condemned the corruptions of religious institutions and the hypocrisies of the pious, his atheism struck at the characterization of humanity as vile, the notion of the perfection of the world-to-come and the beauty of the eternal. As a freethinker, Bakunin rejected this truth and the subordination it sanctioned, whether or not this was directly referenced to the divine.

Whereas Bakunin dismissed revelation as an enslaving fiction, Tolstoy argued that non-domination was the essential truth that the acceptance of God revealed. This is the central message of his short story ‘Master and Man’, written and published in 1895.25 It describes the relationship between Vasilii Andreich Brekhunov, a man of status in his community – innkeeper, merchant and churchwarden – and Nikita, a peasant prone to bouts of drinking but industrious, skilful and strong. Nikita has all the virtues that Vasilii Andreich lacks. He is honest and good-natured, ‘fond of animals’, and attaches little value to monetary reward. Vasilii Andreich is dishonest and obsessed with material enrichment. He purloins the church money in his care to advance his business interests and exploits Nikita’s goodwill to underpay him at irregular intervals of his choosing. Together they embark on a journey: Vasilii Andreich must get to another village in order to close a deal. Even though the weather is atrociously cold and the snow is falling as thick and fast as the night, Nikita harnesses his own favourite horse and they both set out on the sledge. Vasilii Andreich is well covered in fur. Nikita is barely equipped, having sold his good boots for vodka and anyway lacking the wherewithal to afford warm clothing.

Two bad choices encapsulate the nature of Vasilii Andreich’s mastership of Nikita. The first is Vasilii Andreich’s decision to take the faster but less secure route to their destination, against Nikita’s instinct. The second is to push on to the village after getting hopelessly lost in the dark and arriving by chance at the home of a wealthy, welcoming farmer. Vasilii Andreich turns down the invitation of an overnight stay, fearful that time lost will cost money. Nikita, frozen, wet-through and exhausted, is desperate for him to accept but does not contest the decision. His general subservience is signalled by his carefully ordered genuflections at the farm, first to the icons and subsequently to the master of the house, the company seated at the table and finally the women waiting on them. The particular duty he feels is summed up in his comment, ‘[i]f you say we go, we go’.26 What Vasilii Andreich dictates Nikita accepts, even when he strongly disagrees. Tolstoy tells us that Nikita leaves the farm because he ‘was long accustomed to having no will of his own and doing as others bid’.27

The mastership Tolstoy embraces and which Bakunin disputes is the unmediated duty to God. While Nikita’s naive faith makes him vulnerable to his earthly master’s cruelty and meanness, Tolstoy treats his acceptance of God’s will approvingly. Marooned in the snow with no hope of survival, Nikita faces death, but he is calm. One reason is that he has found life pretty unbearable, but the deeper explanation is that he perceives dying as a new stage in his relationship with God, ‘the greatest of all masters’.28 Vasilii Andreich’s unexpected epiphany reinforces Tolstoy’s message, exposing the possibility of a different social ordering. Also realizing that they are stuck, Vasilii Andreich initially attempts to save himself by taking the horse and leaving Nikita to his fate. When the horse brings him back to Nikita, he revises his initial judgement. He was wrong to think Nikita’s life worthless and that his own was made meaningful by his wealth and status. Now appreciating that his obsession with material well-being has caused him to lead an impoverished life, Vasilii Andreich acts selflessly, covering Nikita with his furs and lying over him to keep him warm. Nikita survives the night as a result. Tolstoy describes this last act as Vasilii Andreich’s discovery of God, but there is no rite or ritual. Vasilii Andreich comprehends his calling through the joy and bliss he feels, knowing that Nikita lives.

While Bakunin and Tolstoy explained domination in very different ways, they advanced similar critiques. Both railed against the iniquity of hierarchy, but whereas Bakunin called on the oppressed to rise against masters, Tolstoy implored masters to accept their equal subordination to God and relinquish their unearned privilege. Bakunin would have likely encouraged Nikita to defy God as a first step to his emancipation, following the example of Adam and Eve – Bakunin’s novel reading of Genesis.29 But the subordination that Bakunin resisted as dominating is not equivalent to the obedience to God that Tolstoy believed essential for non-domination. Although Tolstoy treated non-resistance as godly, he shared Bakunin’s worries about the imposition of belief. Nikita adopts the rituals of the Church and the hierarchies that go with it. Yet he intuits God from his relationship to the natural world and his faith comes from within. Although Nikita does not challenge Vasilii Andreich, he does not accept his orders as authoritative either. And in the end, divine truth reveals the slavishness of Vasilii Andreich’s behaviour. It does not sanction hierarchy.

The overlaps between Bakunin and Tolstoy are also evident in their accounts of domination and authority. Bakunin equated authority with the hierarchical principles that underpinned and structured government. Tolstoy showed that authority is embedded in norms and habituated behaviours. Tolstoy’s masters, like Bakunin’s oppressors, are by no means distinguished individuals. They are unexceptional, relatively privileged people – functionaries of all sorts – who make the most of the power advantages that hierarchy affords them. Their self-advancement through hierarchy is the essence of domination. Bakunin wanted judgement and consent to replace command and obedience. Fixed, universal and constant authority should give way to the ‘continual exchange of mutual, temporary, and, above all, voluntary authority and subordination’.30 For Tolstoy the rejection of hierarchy meant tapping into truth to resist ways of living that sustain mastership: refusing to serve mammon, refusing to exploit privilege. In both instances, non-domination flows from disobedience and it empowers individuals to do only what they think is right and resist what they know to be wrong.

Domination and conquest: Élisée Reclus and Voltairine de Cleyre

In conventional politics, conquest refers to the subjugation of one group of people in war. In just-war theory it legitimizes the exercise of what John Locke termed the most ‘despotical power’ over warmongers. So when Africans were deemed to have placed themselves in a state of war with the Royal Africa Company in the seventeenth century, it seemed right to Locke that their captors were permitted to sell their captives to American plantation owners.31 In anarchist politics, by contrast, conquest describes the institutional and social processes that cement domination and it always involves enslavement and usually killing, too. Violence is integral to conquest, but other processes – homogenization, monopolization, centralization, nationalization and internationalization – also play a role. Domination can proceed seemingly without violence, though not without the power advantages that the capability to exercise it involves.

In thinking about conquest, anarchists often collapse the distinction between government by consent and government by usurpation. That is not to say that anarchists are insensitive to the relative harms and benefits of different types of regime. As Kropotkin noted, Parisian authorities did not enjoy the same power that governors in Odessa had to publically flog men and women. In France the Revolution had established citizenship rights and rulers were forced to respect them.32 The anarchist argument about conquest turns instead on the processes of state formation, not the limitations that extend from the legitimating stories – such as Rousseau’s – that governors spin. In this respect, Bakunin’s recommendation that philosophers give up theorizing experience and start using experience to theorize was an important spur for anarchists to examine the factors explaining the rise of modern states.

Scepticism about the explanatory gap between history and political theory is not distinctively anarchist. The twentieth-century philosopher Simone Weil did not express any anarchist sympathies when she observed that the ‘single and separate … territorial aggregate[s] whose various parts recognize the authority of the same State’ have come into being in the course of protracted, often bloody histories.33 Her brief history of France showed how national identity was also constructed through the process of conquest. The French had been made by force, Weil argued, and integration had been achieved by atrocity, not consent. ‘[T]he kings of France are praised for having assimilated the countries they conquered’,34 but the truth was that they uprooted their inhabitants – exposing them to the most ‘dangerous malady’ human societies could suffer.35

In anarchist politics, doubt about the robustness of the theoretical distinction between consent and usurpation supports a general critique of state-building. The gruesome history of state formation does not reinforce the integrity of the nation (as it does for Weil), but instead emphasizes the contingency of states and the commonality of the factors explaining both the initial consolidation of territorial power and its subsequent deployment to exploit peoples and resources beyond the state’s borders. In other words, the gap between consent and usurpation is filled by a concept of colonization. Colonization is experienced by different peoples in very different ways but is integral both to the territorialization of European states and their subsequent appropriation of non-European lands. This argument was made in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries by the ex-Communard and geographer Élisée Reclus and the feminist writer and educator Voltairine de Cleyre, among others. While Reclus explored the reasons for Europe’s hegemony and the destructive power of European civilization, de Cleyre described the impact of colonization on the indigenous peoples living in Mexico.

The hypothesis informing Reclus’s spatial history was that global change was driven by movements of ideas and peoples, brought together principally by trade and in war and mediated by the existence of environmental barriers and passageways – mountain ranges, deserts, plains, rivers and natural harbours. Benefiting from a temperate climate and a largely navigable landscape, Europe was an obvious point of convergence. Yet for Reclus Europe had only acquired its hegemonic position relatively recently and the linear stories Europeans told to glorify it were partial and unpersuasive.

The roots of European civilization could, of course, be traced to ancient Greece and Rome, but Reclus observed that the Greeks had not been originators. They had taken their knowledge from Asia Minor, Egypt, Syria and the Chaldeans. Babylon, Memphis, regions of India, Persia and Indonesia all pre-dated Athens as ‘world centres’ of learning. Europeans had absorbed the wisdom of the East – metallurgy, the domestication of animals, written language, industry, arts, science, metaphysics, religion and mythology – to establish pre-eminence. Historical and geographical luck explained the westward flow of ideas. The communities that thrived in Central Asia, India and Iran, for example, were drawn from populations that remained widely dispersed and relatively isolated; consequently their practices and ideas were also generally localized.

Processes of internationalization – akin to what we now call globalization – and Europeanization, hastened by technological change, in part explained the domination that Europeans exerted. For example, advances in marine engineering and navigational science facilitated global interconnections and enabled the British to settle in Ireland, America, Australia and New Zealand. Critical mass and flexibility also played a part in securing Europe’s hegemony. Apart from the fact that English was introduced in all the lands Britain conquered, the plasticity of the language boosted its widespread adoption in Europe and across the world. The replication of European institutions, costumes and manners, apparently ‘pushed to absurdity’36 in Japan, further explained cultural homogenization.

The philosopher and art historian Ananda Coomaraswamy observed similar trends in India. Europeanization not only promoted the worst aspects of European culture, its ‘Teutonic and Imperial’ civilizing mission and the ‘novel and fascinating theory of laissez-faire’, but in doing so it also smothered the best in Indian traditions, its ‘religious philosophy’ and ‘faith in the application of philosophy to social problems’. And because the modern world ‘is not the ancient world of slow communications’ the net loss was felt instantly; ‘what is done in India or Japan to-day has immediate spiritual and economic results in Europe and America’.37 Reclus concurred. He too associated the hegemony of Europe with its materialist, acquisitive culture. Europe was the smallest land mass and Europeans constituted about a quarter of the world’s population. Nevertheless, Europe possessed more than half the world’s wealth.38 These statistics were telling.

Europeans colonized by extending regimes of private property ownership through war. Reclus admitted that this regime was not total, not even in Europe. At the start of the twentieth century, he observed, there ‘is not a single European country in which the traditions of the old communal property have entirely disappeared’.39 He also believed that resistance had challenged oppression. But the Europeans’ drive for private acquisition was still totalizing. There were three reasons. First, the colonizers’ thirst for enrichment was unquenchable. Second, the structural inequalities that private ownership cemented fuelled resentments that were easily projected through racism and supremacism. A three-year stay in Louisiana in the early 1850s taught him that chattel slavery was habitually described as a ‘cause of progress’ willed by ‘the doctrines of our holy religion, and the most sacred laws of family and property’.40 Third, the instability of the social antagonisms that private property instituted necessitated the permanent deployment of armed force. It was for this reason that Reclus described colonization as a generalized condition of war, exemplified by sporadic, increasingly industrialized conflicts. Writing during the 1898 Spanish-American War he argued:

War is upon us; terrible war with its atrocities and unspeakable stupidity draws near. We hear its distant echo. Each one of us has friends or relations calling themselves heroes because they massacre Matabeles or Malagasys, Dervishes or Dacoits, inhabitants of the Philippine Isles or Cuba, coloured men, whites or blacks.

But danger breaks forth around us, it already presses on us. The Spaniards, our neighbours, and civilised English-speaking men – North Americans rush on one another with cries of hatred, coarse words and deadly weapons. An explosion of hatred and fury precedes the cannon’s roar and the bombardment of cities. The American government appeals to Edison’s genius, to the science of all inventors in order that they discover new wonders in the art of exterminating their fellow creatures.41

Nearly forty years Reclus’s junior and radicalized by the injustice of the Haymarket trial, Voltairine de Cleyre presented a critique of colonization that chimed closely with his. Her 1911 analysis was framed by a reflection on the Mexican Revolution. Like Reclus, she identified land ownership as the primary issue at stake in the conflict and she associated different regimes of ownership with alternative cultures. Thus the customs of the indigenous peoples were communistic. ‘By them’, she explained, ‘the woods, the waters, and the lands’ are held in common. All were free to take what they needed to build cabins and irrigate crops. ‘Tillable lands were allotted by mutual agreement before sowing, and reverted to the tribe after harvesting, for re-allotment. Pasturage, the right to collect fuel, were for all.’ These were mutual aid societies: ‘Neighbor assisted neighbor to build his cabin, plough his ground, to gather and store his crop.’42

Colonization was the imposition of a ‘ready-made system of exploitation, imported and foisted upon’ the indigenous population ‘by which they have been dispossessed of their homes’ and ‘compelled to become slave-tenants of those who robbed them’.43 In Mexico, under the Díaz regime (1876–1911), colonization was characterized by a programme of land acquisition that created haciendas so vast that they rivalled the acreage of US states. De Cleyre compared the effects of colonization to the Norman Conquest:

Historians relate with horror the iron deeds of William the Conqueror, who in the eleventh century created the New Forest by laying waste the farms of England, destroying the homes of the people to make room for the deer. But his edicts were mercy compared with the action of the Mexican government toward the Indians. In order to introduce ‘progressive civilization’ the Díaz régime granted away immense concessions of land, to native and foreign capitalists – chiefly foreign indeed … Mostly these concessions were granted to capitalistic combinations, which were to build railroads … ‘develop’ mineral resources, or establish ‘modern industries’.44

Yet insofar as colonization appealed to the magic of law, it was also reminiscent of the English enclosures or Highland clearances:

Mankind invents a written sign to aid its intercommunication; and forthwith all manner of miracles are wrought with the sign. Even such a miracle as that of a part of the solid earth passes under the mastery of an impotent sheet of paper; and a distant bit of animated flesh which never even saw the ground, acquires the power to expel hundreds, thousands, of like bits of flesh, though they grew upon that ground as the trees grow, labored it with their hands, and fertilized it with their bones for a thousand years.45

A Land Act passed in 1894 was one of the potent instruments used in Mexico to privatize enormous tracts of common land and even occupied lands ‘to which the occupants could not show a legal title’. The ‘hocus-pocus of legality’ which completely disregarded ‘ancient tribal rights and customs’ thus permitted ‘the educated and the powerful’ to go ‘to the courts … and put in a claim’, ejecting those who had lived there for generations.46

The dehumanizing effects of cultural imperialism and the casual racism it produced completed de Cleyre’s account of colonization. The lack of ‘book-knowledge’ shown by the indigenous peoples was reason enough to ‘conclude that people are necessarily unintelligent because they are illiterate’.47 Colonizer logic dictated that there was no advantage in ‘putting the weapon of learning in the people’s hands’. And having once assumed that the local people were stupid, it was a short step to cast them as resources, to be managed by those who knew best how to maximize productivity. Displacement followed. Just as a park might today be fracked to feed an energy need, the Yaquis of Sonora in the north of Mexico were casually ordered to go en masse to Yucatan, some two and a half thousand miles south as the crow flies, to labour as slaves on disease-ridden hemp plantations. The resistance which colonization provoked finally rendered the colonized obstacles to progress and civilization, justifying their pacification by routine imprisonment and frequent troop deployments. The horror of the violence meted out to local people in the name of development is memorably depicted in B. Traven’s 1930s ‘Jungle Novels’. De Cleyre’s tone is more measured, but she exposes the same flaws in colonizer reasoning: ‘Economists … will say that these ignorant people, with their primitive institutions and methods, will not develop the agricultural resources of Mexico, and that they must give way before those who will so develop its resources; that such is the law of human development’.48

Education

The anarchists’ colossal ambition is to combat domination. Anarchism requires individuals to be self-reliant and co-operative, ready to make judgements and listen to others, take initiatives, share the benefits and support others in times of need. Opponents sometimes accuse anarchists of harbouring unrealistic ideas of human goodness because of the critique of domination they advance. Their argument runs like this: anarchy is all very well in principle, but people are actually acquisitive, selfish and uncooperative. Reduced to a belief in human goodness and evaluated against selective cultural practices, anarchy is easily made to appear unrealistically utopian.

In fact, anarchists have rarely denied the complexity of human behaviours; Bakunin’s rejection of the thesis of human wickedness does not assume that people are ‘naturally’ good. Kropotkin once said that humans divined the most important insights about ethics – that human well-being depends on co-operation – from observing the behaviours of non-human species. He did not suggest what non-humans learned in return, except perhaps to steer clear of humans, but the implication was that the quality of human social relations depended on the development of co-operative practices. In promoting the principle of mutual aid, Kropotkin sought to counter the conventional view that co-operation required discipline and obedience. Accepting Rousseau’s insight that individuals are products of their environments, he called for continuing programmes of non-dominating cultural change to promote life-enhancing ways of living. This is revolution as de Cleyre understood the term, ‘some great and subversive change in the social institutions of a people, whether sexual, religious, political, or economic’.49 Education is a favourite recipe in this anarchist cookbook.

Anarchists typically understand education as an approach to life, tapping into long-established conventions that emphasize processes of socialization and moral development as well as learning or knowledge acquisition.50 Expressing a widely held anarchist view, Lucy Parsons defined education as creation of ‘self-thinking individuals’.51 Working on the other side of the Pacific in late Qing dynasty China, the foremost anarchist organizer Shifu likewise distinguished ‘formal education’ from ‘education in the transformation of quotidian life’.52 Distancing himself from campaigns his comrades promoted to instruct people about the basics of anarchism, he pushed for an education that demanded understanding of the ‘causes of the vileness of society’, the abandonment of ‘false morality and corrupt systems’. This kind of deep learning required the eradication of ‘the clever people’ and the disregard of ‘the teachings of so-called sages’. Shifu’s was a programme of disobedience and anti-government activism intended to restore ‘the essential beauty’ of ‘human morality’.53 ‘We must learn to think differently,’ said, in a similar vein, Alexander Berkman, editor of the Blast, ‘before the revolution can come’. His language was strongly gendered, but the nature of his conception was clear:

We must learn to think differently about government and authority, for as long as we act as we do today, there will be intolerance, persecution, and oppression, even when organised government is abolished. We must learn to respect the humanity of our fellow man, not to invade him or coerce him, to consider his liberty as sacred as our own; to respect his freedom and his personality, to foreswear compulsion in any form: to understand that the cure for the evils of liberty is more liberty, that liberty is the mother of order.

And furthermore we must learn that equality means equal opportunity, that monopoly is the denial of it, and that only brotherhood secures equality. We can learn this only by freeing ourselves from the false idea of capitalism and property, of mine and thine, of the narrow conception of ownership.54

For all these anarchists, education meant demystifying power and authority and fostering autonomy. However, it did not mean schooling. Indeed, nineteenth- and early twentieth-century anarchists believed that schools served a crude ideological function. The Chicago anarchist Oscar Neebe remembered that his schooling had been designed to reinforce Church authority. He wrote: ‘I was educated in the protestant religion and was taught to hate those who believed in another form or way concerning a God; my religion I was told was the only, the best.’55 His comrade Adolph Fischer wrote at greater length about the politics of schooling:

It happened during the last year of my school days that our tutor of historical science one day chanced to refer to socialism, which movement was at that time beginning to flourish in Germany, and which he told us meant ‘division of property’. I am inclined to believe now that it was a general instruction given by the government to the patriotic pedagogues to periodically describe to their elder pupils socialism as a most horrible thing. It is, as is well known, a customary policy on the part of the respective monarchial governments of the old world to prejudice the undeveloped minds of the youth against everything which is disagreeable to the despots through the medium of the school teachers. For instance, I remember quite distinctly that before the outbreak and during the Franco-German war we were made to believe by our teachers that every Frenchman was at least a scoundrel, if not a criminal. On the other hand, the kings were praised as the representative of God, and obedience and loyalty to them was described as the highest virtues.56

Since the nineteenth century anarchists have consistently argued that the possibilities for education have been severely constrained by the institutions and practices that have been adopted ostensibly to advance learning. Anarchists have offered various explanations for this divergence. They have also responded differently to the challenges that schooling and education pose for anarchist cultural change. Yet while some anarchists have argued that socialization sits as uneasily as schooling with principles of self-mastery, these discussions and debates point to a critical anarchist model of education.

Scholasticism, schooling and socialization

There is a long history of anarchist opposition to the hierarchy of knowledge and to compulsory schooling. Writing in the 1840s when the influential Prussian school system was still in its infancy, Max Stirner summarized the problem of elitism and mass education by highlighting a historical shift from humanism to realism. Humanism was associated with Reformation thought and realism was a term Stirner adopted to describe the spirit of the post-revolutionary period. In humanism education was animated by ‘subjection’: the mastery of adults over children, the rulers over the ruled and the powerful over the powerless. It was a ‘means to power’. It ‘raised him who possessed it over the weak, who lacked it, and the educated man counted in his circle … as the mighty, the powerful, the imposing one, for he was an authority’. Stirner summed up the idea wrought by realism as ‘everyone is his own master’. The Revolution ‘broke through the master-servant economy’ and destroyed the principles of power and exclusivity in humanism. It was as a consequence of this shift that ‘the task of finding true universal education now presented itself’.57 Stirner argued that the state had played the lead role in this process of change and that it had reached a hiatus such that humanist and realist systems worked in tandem and neither prevailed. With the impetus of the state, education had been realized universally, but the influence of the old principles was undiminished.

The general critique of education that Stirner’s argument supports is that the conflict between the elitist advancement of learning and the egalitarian impulse for universal education results in the ruin of education and the maintenance of knowledge hierarchies. The effort to inculcate excellence universally on the scholastic model results in the spread of mere instruction to support social conservatism. Learners are induced to learn what is regarded to be valuable or useful and denied the latitude that elites traditionally enjoyed to engage creatively with the full range of social and cultural influences they encounter. This move towards instruction is exacerbated by government control of schools. This was the complaint that the Haymarket anarchists had made of their own education and it was echoed by Kropotkin and Tolstoy in the 1880s when a series of school reforms paved the way to aggressive Russification: the promotion of Russian Orthodoxy and the Russian language. Mass education was used to counter the spread of revolutionary doctrines and in the process it became a colonizing, repressive instrument.

Since the nineteenth century, anarchists have argued that state regulation of education enables governments to mould or set curricula, select and enforce languages of instruction, reinforce patriarchy through gendered training programmes and build allegiance to manufactured national cultures. Equality of access to schools and the crumbling of education into instruction reconstruct the master-servant relationship and cultures of domination. Moreover, elitism is maintained even though scholasticism has been replaced by meritocracy. Indeed, the normalization of elitist values can be gauged by the embrace of meritocracy as a principle of national education in the era of mass instruction.58

Tracing the rejection of compulsory schooling to Godwin, Colin Ward, one of the most influential anarchists of the twentieth century, modelled his concept of anarchist education on three principles: the rejection of state education, the ditching of classroom learning and the rebalancing of education towards practical skills and away from book-learning.59 Inspired by the private schools which working people had established in parts of the UK to educate their children before they were forced to send them to state institutions, Ward disputed the necessity and value of state education. The existence of these schools gave the lie to the claim that state provision met a need that could not otherwise be satisfied. Moreover, in stark contrast to their elite counterparts, these private schools were flexible to children’s needs, typically less disciplinarian than state schools and run locally under the control of the parents. Ward’s argument was that the state spoiled these grass-roots institutions when it soaked them up.

Ward disputed the value of classroom learning because he believed that it prioritized instruction over flourishing. Children were institutionalized through the experience of schooling but not stimulated by the instruction it provided. His view was that children should not be removed from society (placed in what Kropotkin called ‘small prisons for little ones’),60 but that they should instead be encouraged to engage with and learn about the world around them. Factories, farms, urban environments were all potential places for learning, he argued.

The third pillar of Ward’s educational programme, the rebalancing of education away from book-learning, reflected his view that schooling was geared too narrowly to the cultivation of academic success. As a self-taught social theorist, Ward did not set his face against academic learning, but he was highly critical of the concept of the school as a filtering system. His view of state education was that it was designed to identify those children best able to master particular sets of skills. All children were expected to follow the same programmes of instruction, irrespective of their proclivities and those who failed to demonstrate the acquisition of the skills state education prized were also devalued. Taking his lead from the eighteenth-century socialist Charles Fourier and a host of anarchist educators, Ward recommended the adoption of a practice-based approach that enabled children to follow their creative bents by doing. Why learn about music when you can listen to musicians or even play? Why study nutrition when you can cook and eat?

Herbert Read and Paul Goodman, both Ward’s contemporaries, sharpened this critique by revisiting the sociological changes that Stirner had contemplated in the 1840s. A lot had changed in the intervening period and neither Read nor Goodman believed that the revolutionary changes promised by Stirner’s realist revolution had been achieved. Writing in the late 1940s, Read argued that modern schooling had been turned into ‘an acquisitive process, directed to vocation’. In the seventy-year period following the introduction of elementary schooling in Britain, education had been entirely disconnected from the idea of individual flourishing. Humanism had all but disappeared. Leonard Ayres, the American educator and educationalist, promoted the kind of institutional approach that caused Read to despair. Contemplating the wisdom of introducing military drill into US high schools in 1917, Ayres observed:

There are three questions that are always in order when it is proposed to establish a new course in the public schools to train workers for a definite trade or vocation. The first is: ‘What knowledge and skill required in the trade can the school give?’ The second is: ‘What will the new course cost in time and money?’ The third question is: ‘What can we learn about such courses from the experience of localities where they have been in operation?’ These three questions are always relevant, whether the new course is for boys or for girls and whether it is designed to reach all of the pupils or only those who choose to enter it.61

Like Ward, Read was worried about the management of schools and the adequacy of the means adopted to educate learners – how far education had become geared to instruction and book-learning, for example. But in his view, these arguments were symptomatic of a broader failure, which he called the ‘failure to specify clearly enough’ the aims of education. Returning to the moral and behavioural aspects of education, Read considered that the discussion of aims had been obscured by arguments about delivery of teaching. His comments were not directed at Ward specifically, but they had some relevance to his position. Ward believed that removing children from the ‘ghetto of childhood’ and ‘sharing interests and activities with those of the adult world’ was a ‘step toward a more habitable environment for our fellow citizens, young or old’.62 Read’s worry was that the adoption of innovative teaching methods would not prevent children being socialized into worlds that were structured by values inimical to non-dominating cultures, even if they attended schools that were not run by the state.

For Read, schooling was fundamentally rigged to the ‘competitive system’ and designed to deliver ‘efficiency, progress, success’. As an art historian who associated education with creativity, growth and self-fulfilment, Read judged these impoverished goals. He noted, too, that unpacking their meaning was ‘necessarily excluded’ from education debates.63 Not only, then, was government able to determine the cultural values that education met, it was also empowered to remove debates about cultural purpose from public agendas. This form of agenda setting explained why subsequent generations of children were variously required to recite articles of faith, learn military discipline and meet the needs of business to advance national power globally.

Goodman further pressed Read’s arguments. Noted for mixing self with sociological analysis, Goodman wrote about his sense of anomie from the vacuity of American consumerism and suburban living and the effects of corporate advancement, rationalization, affluence and bureaucratic welfare systems in post-war America. These were almost entirely detrimental and he used the term ‘the empty society’ to describe the prevailing culture. Some of the most obvious symptoms of the ‘empty society’ were middle-class withdrawal into the suburbs, the urban ghettoization of poor and Black American populations, the growth of public media and the concomitant depletion of intelligent news reporting, social breakdown and delinquency. America, he argued in 1966, was ‘on a course’ heading towards ‘empty and immoral empire or to exhaustion and fascism’.64

These seismic sociological shifts were played out in education. Like Read, Goodman argued that modern education was designed to meet government agendas. But insofar as these were shaped by competitive advantage and global market success, he also argued that the usefulness of educating the general population had been comprehensively outstripped by economic realities. Only a ‘few percent with elaborate academic training’ were required to sustain bureaucratic systems, yet ‘all the young are subjected to twelve years of schooling and over 40% go to college’.65 Most of this time was wasted for reasons that Ward elaborated; American schooling was compulsory miseducation.66 Goodman further linked the pointlessness of classroom activity to the smooth operation of ‘the profit system’, whose continued health pointedly exposed the miscalculations of Marxist imaginings. Indeed the rudeness of capitalism’s health was inversely related to the physical and psychological sickness of the individuals captured within it. The profit system locked people into mindless, paralysing relationships of dependency: the poorest earned just enough money to buy the endless streams of throwaway goods that better-off technicians, trained to ‘execute a detail of a program handed down’, were tasked with producing.67 Everyone submitted to this ‘inhuman routine’ from ‘fear and helplessness’ and because powerlessness afforded a sufficient, albeit thin veneer of security. Considerations of ‘special vocation, profession, functional independence, way of life, way of being in the community, or corporate responsibility for the public good’ could be set aside for as long as individual activity ‘pays off in the common coin’.68 Schooling, like work, was essentially designed to prepare learners to become cogs in this cultural machine. Teachers had become ‘personnel in a school system, rather than contributing to the growing up of the young’.69 And education served to hold the young ‘on ice’: keep them busy before they entered the world of work and give them the illusion of belonging.

Goodman diverged from Read when he suggested that the cultural values of the Prussianized American school system – efficiency, progress and success – were not faulty in themselves. The problem was in their conceptual bias. Efficiency could be tied to human scale as easily as it could be fastened to economies of scale; progress attached to environmental care and community interaction and detached from individual advancement. Likewise, it was possible to measure success by psychological well-being, not wealth or income.

Goodman explained the tendency to default to the least good alternatives and the concealment of the most desirable with reference to the orthodoxy of science. Bizarrely and wrongly presented as a neutral, pure discipline that could be applied to solve any problem, ‘science’ had been turned into an ideological tool in order to charge appointed experts with the determination of social goods and values. In bureaucratic systems the magical, irrefutable expertise of ‘science’ was invoked to champion ideas of progress, technological advancement and economic strength. It promoted and sustained a culture that was the very antithesis of anarchy.70 For anarchy, Goodman argued, ‘is grounded in a rather definite social-psychological hypothesis’:

that forceful, graceful, and intelligent behaviour occurs only when there is an uncoerced and direct response to the environment; that in most human affairs, more harm than good results from compulsion, top-down direction, bureaucratic planning, pre-ordained curricula, jails, conscription, States. Sometimes it is necessary to limit freedom, as we keep a child from running across a highway, but this is usually at the expense of force, grace, and learning: and in the long run it is usually wiser to remove the danger and simplify the rules than to hamper the activity.71

There are some significant differences between Stirner, Ward, Read and Goodman and these continue to play out in anarchist politics. For example, hitching education to a set of moral norms, as Goodman proposed, has alarmed anarchists wedded to Stirner’s egoist position that individuals must always find and define their own. For Stirner, inviting individuals to master practices whose value has already been determined frustrated creative self-development and was a form of social control.72 Even though a lot of anarchists have leaned towards Goodman and distinguished the norms, practices and ways of living that emerged from co-operative social interactions from the manufactured, imposed norms that sprang from the needs of government, Stirner’s critique has also had a strong purchase. Not untypically, the London-based post-war antimilitarist Frederick Lohr adopted a view that owed something to ‘social’ and ‘egoist’ ideas. On the one hand, his coupling of ‘bourgeois materialism’ with the artificial ‘conception of economic man’ essential to Soviet communism spoke to a vision of technology and social emptiness that chimed with Goodman’s view. On the other hand, his critique of socialization had a Stirnerite flavour. ‘Man cannot be socialised,’ he declared. ‘To socialise man is to dehumanise him, to make him a robot, to give him a collective conscience instead of allowing him to develop a personal consciousness.’73 To resolve the tension Lohr argued that individuals were social beings. Anarchism did not socialize, Lohr argued, because it recognized that ‘nature is social’.

Goodman was less equivocal. Anarchism educated and moralized and it did so in order to counter domination. Like Read, he believed that education necessarily moralized because it was part of a social process. The anarchist goal was not to set education against creativity or individual will, as Stirner appeared to do, but to release creativity through education. The question, for them, was how to specify moral values in ways that enable self-mastery through socialization and always remain alert to the possibility of domination.

Anarchists have made a number of practical proposals to tackle knowledge hierarchies. In order to overcome divisions between intellectual and manual workers, nineteenth-century anarchists promoted what Bakunin called integrated education. The thinking behind this idea was that ‘no class can rule over the working masses, exploiting them, superior to them because it knows more’.74 Bakunin’s proposal was to ensure all children received an integrated or all-round training which developed manual alongside mental skills to enhance both capabilities. Another anarchist response has been to set up alternative institutions – free skools. Louise Michel was an early advocate and practitioner, but Francisco Ferrer’s Modern School, founded in 1901, is probably the best-known historical initiative. The experiment in Barcelona sparked the rise of a movement and in the early twentieth century Ferrer schools sprang up across Europe and in America. Describing himself as a positivist and idealist, Ferrer promoted the teaching of advanced arts and science – from Ibsen to Darwin – in an effort to offset the influence of conservative Catholicism. Replacing ‘dogma’ with a rational method aimed to stimulate pupils so that they could flourish as individuals while also learning how to contribute ‘to the uplifting of the whole community’. Education, Ferrer argued, was not just about ‘the training of … intelligence’, it was also about ‘the heart and the will’.75

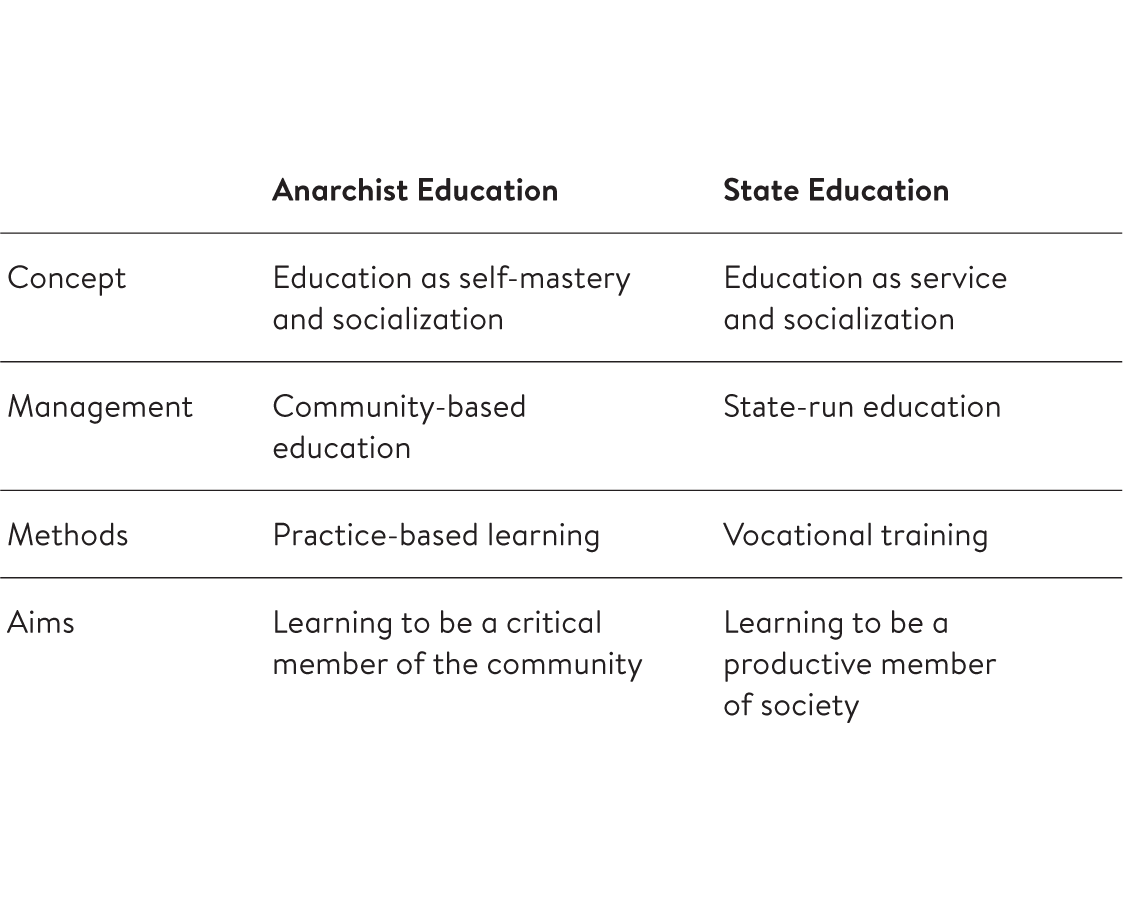

Anarchist conceptions of socialization shape the framing, delivery and design of education

The critical pedagogy advanced by the twentieth-century educator and philosopher Paulo Freire is probably the most powerful influence active on contemporary anarchist thinking about education.76 While Freire used Marxist humanism as a touchstone for his thinking, anarchists have been inspired by his exploration of the ways that classroom relations replicate and reinforce wider forms of social oppression. For Freire, the teacher-pupil relationship is essentially one of the oppressor and the oppressed. The possibility of delivering transformative programmes of education (such as those that Ferrer imagined) depends both on the abandonment of neutrality and the development of non-oppressive practices. Once learners acknowledge that education moralizes and that it serves a political function they are able, too, to blur the boundaries between instructors and learners. All instructors are learners and all learners possess valuable knowledge and experience. While anarchists have combined the ideas that Freire articulated in various measures, versions of both are typically found in the two major approaches to knowledge acquisition they have experimented with: propaganda and skill-sharing.

Propaganda may seem an odd term for anarchists to adopt to describe a strategy intended to support the development of non-dominating cultures. Indeed, such is the pervasiveness of corporate advertising and the strength of the association of propaganda with the idea of systemic and ‘conscious manipulation’, that some anarchists avoid the term altogether.77 However, before the experience of inter-war dictatorship and the explosion of media newspeak, propaganda was readily associated with open debate and political persuasion. Webster’s 1913 dictionary defines ‘propagandism’ as the ‘art or practice of propagating tenets or principles; zeal in propagating one’s opinion’.78 This was how anarchists understood propaganda in the early years of the movement. And when contemporary anarchists use the term, this is often how they still understand it.

Propaganda by the deed is by far the most notorious form of anarchist propagandism but is not an accurate guide to it. Wrongly conflated with assassination and individual acts of terror, propaganda by the deed developed as part of a wider educational strategy that involved writing, leafleting, publishing and visual art as well as symbolic performance and disobedience. In these multiple forms, anarchist propaganda is designed to explain and advance anarchist ideas. It is replete with guidance, proposals and recommendations but is intended to close the gap between the ‘enlightened’ and the ‘unenlightened’ and avoid the need for vanguard movements charged with leading the exploited to revolution. The earliest advocates of propaganda by the deed, Errico Malatesta and Carlo Cafiero, exhorted anarchists to adopt the policy precisely because they thought that the demonstration of anarchism through action – ‘insurrectional deeds’ – would disrupt existing class relations more effectively than written propaganda and therefore bring the public to anarchism under its own steam.79

Propagandistic deeds can take multiple forms. For writers like Lawrence Ferlinghetti, expressive writing might be considered in this bracket because it educates both by communicating anarchist ideas and by making forms of cultural expression like poetry, which have traditionally been reserved for elites, available to all. Unlike more traditional forms of written propaganda – manifestos, constitutions, newspapers, flyers and information sheets – creative writing does not function to deliver ideas to passive consumers but to engage people in ways that are themselves transformative. Visual and performance art works in a similar manner, communicating both through content and in form to build and sustain activism. Talking about his art practice, Gord Hill argues that ‘propaganda is a vital part of resistance movements’. As propaganda, music, visual art and literary work can inspire, educate and motivate, help build cultures of resistance and maintain their histories.80

Malatesta and Cafiero appreciated that propaganda could be used to bamboozle or mislead. They were consequently wary of propagandists who assumed they knew better than their audiences or who sought to extend knowledge without inviting discussion or offering explanation – instruction without understanding. A telltale sign was the use of obscure language, abstract ideas or scholastic methods to impress, befuddle and belittle. A perennial anarchist complaint about party-approved forms of Marxism is that it presents socialism as scientific, encouraging abstruse theory that is difficult to understand and a technical approach to political argument; Marxism politicized science to use it as a tool to beat the bourgeoisie, but in Goodman’s terms, it promoted a concept of scientific objectivity or neutrality. The beauty of propaganda by the deed was that it did not rely on the mastery of complex theory. Burning land registry documents or refusing to respect a prohibition on a meeting in order to provoke an aggressive police response effectively taught hard lessons about the flimsiness of private property rights and legal bias and intolerance. Even if these lessons were inspired by heaps of written propaganda and a good amount of anarchist theory, the actions were hands-on, vivid and intelligible. Deeds educated to the extent that they transformed compliance into rebellion, fostering the critical, non-dominating cultures that anarchists championed.